Managing menorrhagia

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Managing menorrhagia

Quality in Health Care 1995;4:218-226

Effectiveness Bulletin

Managing menorrhagia

Angela Coulter, Andrew Long, Joanne Kelland, Susan O'Meara, Mark Sculpher,Fujian Song, Trevor A SheldonThis review is based on Efffective Health Care, Bulletin No 9

King's Fund, LondonAngela Coulter, directorNuffield Institute forHealth, University ofLeeds, Leeds LS2 9PLAndrew Long, seniorlecturerJoanne Kelland, researchassistantSusan O'Meara, researchassistant

Health EconomicsResearch Group,Brunel University,Uxbridge, MiddlesexMark Sculpher, researchfellowNHS Centre forReviews andDissemination,University ofYork,York YO1 SDDFujian Song, researchfellowTrevor A Sheldon,directorCorrespondence to:Mr A Long, NuffieldInstitute for Health,University of Leeds,71-75 Clarendon Road,Leeds LS2 9PL

Menorrhagia - excessive regular menstrualblood loss - is one of the most common reasonsfor gynaecological referral' and is the mainpresenting problem in at least half of all womenhaving hysterectomies.2 Referral and treatmentrates vary widely, nationally and inter-nationally,3 4 reflecting uncertainty about themost appropriate management.Two population studies showed that average

blood loss is between 30 and 40 ml; in 90% ofthe population the loss is less than 80 ml,5 6leading to the widely accepted clinical defi-nition of menorrhagia as blood loss of 80 mlor more per menstrual period. Although objec-tive measurement of blood loss is possible,7 itis confined to research uses and is not currentlyconsidered to be routinely feasible in clinicalpractice.

In a national survey 31% of the womendescribed their blood loss as heavy.8 However,many women who seek treatment for heavybleeding in reality do not have higher thanaverage menstrual blood loss.' 9 10 11 In onepopulation study 26% of women with bloodloss well within the normal range (< 60 ml)considered their loss heavy and 40% of thosewith objectively heavy losses (> 80 ml) con-sidered their loss as moderate or light.5 In onestudy in Scotland over half the women referredfor endometrial ablation for dysfunctionaluterine bleeding had menstrual blood loss lessthan 80 ml.12

This paper reviews the evidence of theeffectiveness of management options for men-orrhagia. Searches were undertaken onMedline, Embase, and several other databases,including that of the Research Council forComplementary Medicine, to identify therelevant research reports and were supple-mented by consultation with experts andmanual cross checking of reference lists. Drugtrials without objective measures of menstrualblood loss were excluded. The searches ident-ified 31 randomised controlled trials of drugtreatments which included objective measure-ment of menstrual blood loss and threerandomised controlled trials of surgical inter-ventions, comparing abdominal hysterectomywith hysteroscopic surgical procedures. Adiscussion of the quality of studies appears inEffective Health Care Bulletin No 9.

Effectiveness ofmanagement optionsREASSURANCEIt is difficult for women to judge how theirexperience of menstrual blood loss compares

with that of others. Although a woman's per-ception of the heaviness of loss and its effecton her quality of life are the major reasons forseeking medical help, she might benefit frombeing reassured that her experience is notabnormal or from being offered counselling.13The effectiveness of giving reassurance andcounselling is not known but is currently beingstudied within a randomised controlled trial inOxford.

DIAGNOSIS

Dilatation and curettage is often carried out onwomen with menorrhagia for diagnostic pur-poses, primarily to exclude the rare butimportant possibility of an endometrial malig-nancy.4 "' The operation commonly entailsgeneral anaesthesia and a two day hospital stay,although the Audit Commission has estimatedthat up to 86% of these procedures could beperformed as day cases."5

Management options for menorrhagia* Reassurance* Diagnosis* Drug treatments* Surgical treatments

The use of dilatation and curettage fordiagnosing endometrial malignancy is not costeffective in women aged under 40 yearsbecause serious disease and the prevalence ofendometrial cancer are so uncommon in thesewomen.16-22 Based on estimates of endometrialcancer incidence of 0-66 per 100000 womenaged 30-34, Vessey et al calculated thatbetween 3000 and 4000 of these procedureswould have to be performed to detect one caseof endometrial cancer in women aged under35.17 This minimal potential benefit needs tobe considered in the context of the risks associ-ated with dilatation and curettage, such asthose associated with general anaesthesia anduterine perforation and laceration of thecervix.'6 18 23 In addition, several studies indi-cated that an appreciable proportion of endo-metrial lesions are not detected by dilatationand curettage. 16 17 24 25

Other methods of investigating the lining ofthe uterus - endometrial sampling - havebecome available, such as the use of narrowcurettes, vacuum curettes, catheters orcannulas, endometrial washing, and endo-metrial scraping or aspiration. Hysteroscopy -that is, the insertion of a small magnifying

218

Managing menorrhagia

instrument through the vagina and cervix toallow viewing of the inside of the uterus - canbe used on its own or with one of the samplingtechniques to achieve a more accurate diag-nosis.26-28 These newer methods of endo-metrial sampling are commonly performed inoutpatient clinics or general practice surgeries.They seem to have high levels of patientacceptability, lower complication rates, and donot require inpatient admission and generalanaesthesia.24 28-57 However, no randomisedcontrolled trial has been carried out tocompare outpatient endometrial sampling anddilatation and curettage.

In the only economic assessment of thediagnostic technologies that has been per-formed - namely, a cost analysis of hyster-oscopy versus dilatation and curettage in theAustralian health service - it emerged that ifoutpatient hysteroscopy were to replacedilatation and curettage performed either as aday case or inpatient procedure an appreciablecost saving to the health service would result.58However, these savings are unlikely to berealised if the possible increase in the rate ofinvestigation is not controlled.

DRUG TREATMENTS

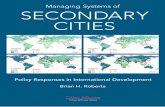

Menorrhagia can be treated by drugs inprimary care. A wide variety of drugs are used,ranging from non-steroidal anti-inflammatorydrugs, antifibrinolytics, hormones, and intra-uterine devices. Each year around C7m is spentin the United Kingdom on primary careprescribing to treat menorrhagia.59 However,the effectiveness of many of the drug treat-ments is uncertain.60 61A summary of the features of the drug trials

performed for menorrhagia can be found at theend of the article (table 1), with the reductionin loss of menstrual blood reported for eacharm of the trials (figure). Since these results arederived from different trials, comparison acrossthe trials, while suggestive, is not a reliableindicator of relative effectiveness since theparticipating patients are not always com-parable. These comparisons indicate that thelevonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device,62-66danazol,65-69 tranexamic acid, (J Bonnar, paperpresented at the Royal Society of Medicine,London, 1994)7°-74 mefenamic acid al Bonnar,paper presented at the Royal Society ofMedicine, London, 1994),65 66 69 75 76 andnaproxen76-79 may be the most efficacious inreducing menstrual blood loss. Norethisterone,particularly at low doses and used for shortduration,65 66 80 81 seems to be the leastefficacious and may be ineffective for reducingblood loss. Of the more efficacious drugs, thehormone releasing coil is not yet registered foruse in the United Kingdom as a treatment formenorrhagia. The serious side effects ofdanazol and its high cost make it unacceptablefor long term use. Early reports of an increasein risk of thromboembolic clots after use oftranexamic acid, which led to restrictions of itsuse in the United Kingdom, have now beendiscounted.82 Mefenamic acid has fewer sideeffects and the advantage of alleviatingmenstrual pain.

This evidence is only suggestive, asinsufficient randomised controlled trials havebeen performed which directly compare thetop ranking drugs. However, in one random-ised controlled trial tranexamic acid showed a58% reduction in loss of menstrual bloodcompared with 28% for mefenamic acid (JBonnar, paper presented to Royal Society ofMedicine, London, 1994). In another,tranexamic acid showed a 45% reduction com-pared with a 20% increase with low doses ofnorethisterone.8'These results are in stark contrast to the

current patterns of prescribing. Based on anational sample of 518 general practitionerswho treated 4603 patients complaining ofmenorrhagia, norethisterone (apparently oneof the least effective drugs) was the mostcommonly used drug, prescribed to 38% of thepatients, followed by mefenamic acid (27%),combined oral contraceptives (11%), com-bined hormone replacement therapy (8%),dydrogesterone (6%), danazol (6%), ethamsy-late (6%) and tranexamic acid (5%).9

SURGICAL TREATMENTS

Three main types of surgical procedures areused to treat menorrhagia: dilatation andcurettage, removal of the uterus and cervix(hysterectomy), and removal of the lining ofthe womb (endometrial ablation).

Dilatation and curettage has been widelyused as a possible treatment option formenorrhagia but has never been shown to beeffective.22 24 No published reports exist ofrandomised controlled trials of this procedureagainst a placebo treatment. Reports fromuncontrolled case studies claiming a beneficialeffect lack objective measurement of bloodloss. The only study to measure blood lossbefore and after dilatation and curettage foundthat blood loss returned to its previous level orhigher by the second subsequent menstrualperiod.9

Hysterectomy is the most commonly usedsurgical treatment for menorrhagia, which canbe performed through the abdomen or throughthe vagina and, more recently, laparo-scopically. The new procedures of endometrialablation or resection with laser surgery ordiathermy are designed to remove as much ofthe uterine lining as possible. Rates of endo-metrial ablation and resection are increasing.Figures from an audit undertaken by the RoyalCollege of Obstetrics and Gynaecology ofendometrial resection or ablation in the UnitedKingdom (in the National Health Service(NHS) or private sector) indicate that from 1April 1993 to 31 October 1994 about 10200procedures were undertaken, 82% of whichused diathermy (transcervical resection of theendometrium or rollerball or a combination ofboth), 16% used laser surgery alone, and 2%radiofrequency or cryoablation.83Hysterectomy is one of the most commonly

performed surgical operations: in England in1993-4, 73 517 women had this operation inNHS hospitals.84 Since many hysterectomiesare performed in private hospitals this figureunderestimates the total number of women

219

Coulter, Long, Kelland, O'Meara, Sculpher, Song, Sheldon

undergoing the procedure. Large socioecon-omic variations exist for the likelihood ofwomen having a hysterectomy for menstrualreasons.85 86 There are three randomised con-trolled trials which compared abdominalhysterectomy with newer, less invasive surgicalinterventions for menorrhagia (table 2)(M J Sculpher et al, personal communication,1995).87-90Hysterectomy requires longer time in theatre

and results in a longer length of stay than theless invasive approaches. Abdominal hyster-ectomy has a high complication rate of around45%, including pain, haemorrhage, woundinfection, urinary retention, urinary tractinfection, and vaginal discharge (M J Sculpheret al, personal communication, 1995).87-90Thiscompares with a rates of 0-15% for resectionor ablation, with reported complications ofuterine perforation, fluid overload, haemor-rhage, and urinary tract infection. Lower com-plication rates have been reported for vaginalhysterectomy in uncontrolled studies.9'9 Toreduce the rate of serious postoperative in-fections preoperative antibiotics should beused routinely. A meta-analysis of 25 trials ofantibiotic prophylaxis during abdominalhysterectomy suggests a possible reduction inpostoperative infections from 2l1% to 9%.94As the uterus is removed in a hysterectomy

the ending of menstrual periods is guaranteed.Endometrial resection or ablation, on the otherhand, is not always successful in reducing men-strual blood loss, and blood loss and pain mayincrease with time after endometrial ablation.95Relatively high rates of reoperation after theinitial treatment with endometrial resection orablation have been reported, ranging from6-23%, with the higher rates being reported instudies with longer follow up.87-90 96102 Thesestudies include repeat resection or ablation orhysterectomy, or both. Another cohort studyestimates the cumulative probability of requiringa hysterectomy four years after endometrialresection as 12% after total resection and 40%after repeat total resection.103High levels of satisfaction have been

reported for both types of surgical proceduresbut seem higher after hysterectomy thanresection or ablation. In terms of health relatedquality of life as measured by the rating scaleof the EuroQolc instrument, the initial advan-tage at one month after the operation of trans-cervical resection of the endometrium is offsetby four months after the operation,89 thedifference being non-significant.As endometrial resection uses less operating

theatre time and requires a shorter length ofhospital stay its health service costs are lessthan those for abdominal hysterectomy.89However, this initial cost advantage maydiminish over time because a substantial pro-portion of women receiving resection sub-sequently have a repeat resection or a hyster-ectomy, or both.Oophorectomy is often performed at the

same time as abdominal hysterectomy toeliminate the risk of ovarian cancer. Whetheror not this practice is justified depends on thebalance of risks and benefits in terms of years

of life gained and quality of life. If the ovariesare removed a premenopausal women will haveundergone a "surgical menopause," with aconsequent increased risk of osteoporosis andcardiovascular disease. However, removal ofthe ovaries also seems to reduce the risk ofbreast cancer.104 Overall, oophorectomyreduces average life expectancy in youngerwomen by at least five years if they did not takehormone replacement therapy.'05 Since manywomen do not comply with long term hormonereplacement therapy the routine removal ofhealthy ovaries in women who are not at highrisk of ovarian cancer is hard to justify.'06

ConclusionsAs many women complaining of heavy periodsmay not in fact have excessive menstrual bloodloss every attempt should be made to ascertainwhether blood loss is indeed high. However,this is difficult without a routinely availablemethod of objective measurement. It is alsoimportant to determine what particular prob-lems heavy periods cause the women.Reassurance may help improve subjectiveassessments of blood loss and discomfort andreduce the need for treatment.

All the treatment options should be discussedwith the woman, giving her sufficient infor-mation about the risks and benefits of drug andsurgical interventions for her to make aninformed choice about management options.

Dilatation and curettage for diagnosisshould generally not be offered to womenunder 40 years. Endometrial sampling, with orwithout hysteroscopic examination, is probablymore cost effective for diagnosing uterine ab-normalities in older women and can be carriedout as an outpatient procedure.

General practitioners should consider offer-ing a course of effective drug treatment such astranexamic acid and mefenamic acid to womenas a first line treatment. Drug use should bemonitored to identify prescribing of apparentlyineffective drugs such as norethisterone.There is no obvious best surgical treatment

for all women. The advantage of conservativesurgery over abdominal hysterectomy in theshort term seems not to be sustained in thelonger term. Dilatation and curettage shouldnot be used as a treatment for menorrhagia. Ifnewer, less invasive surgical techniques areused, it is important to ensure that the surgeonshave the necessary training and skills.Purchasers should monitor indications fortreatment among their provider units, the useof dilatation and curettage in diagnosis, andprescribing patterns.1 Bradlow J, Coulter A, Brooks P. Patterns of referral. Oxford:

Health Services Research Unit, 1992.2 Coulter A, Klassen A, McPherson K. How many hyster-

ectomies should purchasers buy? European Journal ofPublic Health 1995;5: 123-9.

3 Coulter A, McPherson K, Vessey M. Do British womenundergo too many or too few hysterectomies? Soc SciMed1988;27:987-94.

4 Coulter A, Klassen A, MacKenzie IZ, McPherson K.Diagnostic dilatation and curettage: is it used appro-priately? BMJ 1993;306:236-9.

5 Hallberg L, Hogdahl AM, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrualblood loss - a population study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand1966;45:320-5 1.

6 Cole S, Billewicz W, Thomson A. Sources of variation inmenstrual blood loss. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecologyof the British Commonwealth 197 1;78:933-9.

220

Managing menorrhagia

7 Hallberg L, Nilsson L. Determination of menstrual bloodloss. Scandj Clin Lab Invest 1964;16:244-8.

8 Market Opinion and Research International. Women'shealth in 1990. MORI, 1990. (Research study conductedon behalf of Parke-Davis Research Laboratories.)

9 Haynes P, Hodgson H, Anderson A, Turnbull A. Measure-ment of menstrual blood loss in patients complaining ofmenorrhagia. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1977;84:763-8.

10 Chimbira T, Anderson A, Turnbull A. Relation betweenmeasured menstrual blood loss and patient's subjectiveassessment of loss, duration of bleeding, number ofsanitary towels used, uterine weight and endometrialsurface area. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1980;87:603-9.

11 Fraser IS, McCarron G, Markham R. A preliminary studyof factors influencing perception of menstrual blood lossvolume. AmJ Obstet Gynecol 1984;149:788-93.

12 Deeny M, Davis JA. Assessment of menstrual blood lossin women referred for endometrial ablation. EurJ ObstetGynecol 1994;57:179-80.

13 Rees M. Role of menstrual blood loss measurements inmanagement of complaints of excessive menstrualbleeding. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1991 ;98:327-8.

14 Coulter A, Bradlow J, Agass M, Martin-Bates C, TullochA. Outcomes of referrals to gynaecology outpatient clinicsfor menstrual problems: an audit of general practicerecords. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1991;98:789-96.

15 Audit Commission. A short cut to better services: day surgeryin England and Wales. London: HMSO, 1990.

16 MacKenzie IZ, Bibby JG. Critical assessment of dilatationand curettage of 1029 women. Lancet 1978;ii:566-8.

17 Vessey M, Clarke J, MacKenzie I. Dilatation and curettagein young women. Health Bull 1979;39:59-62.

18 Smith J, Schulman H. Current dilatation and curettagepractice: a need for revision. Obstet Gynecol 1985;65:516-8.

19 Hammond R, Oppenheimer L, Saunders P. Diagnosticrole of dilatation and curettage in the management ofabnormal premenopausal bleeding. Br Jf Obstet Gynaecol1989;96:496-7.

20 Stovall T, Solomon S, Ling F. Endometrial sampling priorto hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1989;73:405-9.

21 Allen D, Correy J, Marsden D. Abnormal uterine bleedingand cancer of the genital tract. Aust NZJ7 Obstet Gynaecol1990;30:81-3.

22 Lewis BV. Diagnostic dilatation and curettage in youngwomen. BMJ 1993;306:225-6.

23 Word B, Gravlee C, Wideman G. The fallacy of simpleuterine curettage. Obstet Gynecol 1958;12:642-8.

24 Grimes D. Diagnostic dilation and curettage: a reappraisal.Am _J Obstet Gynecol 1982;142:1-6.

25 MacKenzie IZ. Endometrial biopsy. Current ObstetGynaecol 1992;12: 162-7.

26 Gimpelson R, Rappold H. A comparative study betweenpanoramic hysteroscopy with directed biopsies anddilatation and curettage. A review of 276 cases. Am JObstet Gynecol 1988;158:489-92.

27 Loffer F. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrialsampling compared with dilatation and curettage forabnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negativehysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol 1989;73: 16-20.

28 Lewis BV. Hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormaluterine bleeding. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:283-4.

29 Hofmeister F. Endometrial biopsy: another look. Am JObstet Gynecol 1974;118:773-7.

30 Webb M, Gaffey T. Outpatient diagnostic aspirationcurettage. Obstet Gynecol 1976;47:239-41.

31 Lutz M, Underwood P, Kreutner A, Mitchell K. Vacuumaspiration: an efficient outpatient screening technique forendometrial disease. South MedJ3 1977;70:393-5.

32 Haack-Sorensen P. Starklint H, Aronsen A, Kern HansenM, Kristoffersen K. Diagnostic Vabra (aspiration)curettage. Dan Med Bull 1979;26:1-6.

33 Crow J, Gordon H, Hudson E. An assessment of the Mi-Mark endometrial sampling technique. J Clin Pathol1980;33:72-80.

34 Gregg R. The praxeology of the office dilatation andcurettage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;140:179-85.

35 Valle R. Hysteroscopic evaluation of patients with abnormaluterine bleeding. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1981;153:521-6.

36 Goldberg G, Tsalacopoulos G, Davey D. A comparison ofendometrial sampling with the Accurette and Vabraaspirator and uterine curettage. S Afr Med .J 1982;61:114-6.

37 Suarez R, Grimes D, Majmudar B, Benigno B. Diagnosticendometrial aspiration with the Karman cannula. J ReprodMed 1983;28:41-4.

38 Ferenczy A, Gelfand M. Outpatient endometrial samplingwith endocyte: comparative study of its effectiveness withendometrial biopsy. Obstet Gynecol 1984;63:295-302.

39 MacKenzie I. Routine outpatient diagnostic uterinecurettage using a flexible plastic aspiration curette. Br 7Obstet Gynaecol 1985;92:1291-6.

40 Goldrath M, Sherman A. Office hysteroscopy and suctioncurettage: can we eliminate the hospital dilatation andcurettage? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;152:220-9.

41 Hansen PK, Junge J, Roed H, Fischer-Rasmussen W,Hojgaard K. Endoscan cell sampling for cytologicalassessment of endometrial pathology. Acta Obstet GynecolScand 1986;65:397-9.

42 Mencaglia L, Perino A, Hamon J. Hysteroscopy in peri-menopausal and postmenopausal women with abnormaluterine bleeding. J Reprod Med 1987;32:577-82.

43 Serle E, Walker E, Calder A, Lee F, Govan A. Endometrialbiopsy with the "Abradul" - an alternative to dilatationand curettage. Journal of Obstetics and Gynaecology

(Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Trust) 1988;8:337-42.

44 Lofgren 0, Alm P, Ionescu A, Skjerris J. Uterine micro-curettage with combined endometrial histopathology andcytology. Acta Obstet GynecolScand 1988;67:401-3.

45 Kaunitz A, Masciello A, Ostrowski M, Rovira E. Com-parison of endometrial biopsy with the endometrialPipelle and Vabra aspirator. J7 Reprod Med 1988;33:427-31.

46 Koonings P. Grimes D. Endometrial sampling techniquesfor the office. Am Fam Physician 1989;40:207-10.

47 Henig I, Chan P, Tredway D, Maw G, Gullett A,Cheatwood M. Evaluation of the pipelle curette forendometrial biopsy. _J ReprodMed 1989;34:786-9.

48 Itzkowic D, Laverty C. Office hysteroscopy and curettage- a safe diagnostic procedure. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol1990;30: 150-3.

49 De Jong P. Doel F, Falconer A. Outpatient diagnostichysteroscopy. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1990;97:299-303.

50 Fraser I. Hysteroscopy and laparoscopy in women withmenorrhagia. Am _J Obstet Gynecol 1990;162:1264-9.

51 Eddowes H. Pipelle: a more acceptable technique foroutpatient endometrial biopsy. Br J7 Obstet Gynaecol1990;97:961-2.

52 Koonings P, Moyer D, Grimes D. A randomized clinicaltrial comparing Pipelle and Tis-U-Trap for endometrialbiopsy. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:293-5.

53 LaPolla J, Nicosia S, McCurdy C, Songster C, Ruffolo E,Roberts W, et al. Experience with the EndoPap device forthe cytologic detection of uterine cancer and itsprecursors: a comparison of the EndoPap with fractionalcurettage or hysterectomy. Am _J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1055-60.

54 Iossa A, Cianferoni L, Ciatto S, Cecchini S, Campatelli C,Lo Stumbo F. Hysteroscopy and endometrial cancerdiagnosis: a review of 2007 consecutive examinations inself-referred patients. Tumori 199 1;77:479-83.

55 Meekins J, Haddad N. Gynocheck endometrial tissuesampling: an alternative to dilatation and curettage.Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Institute of Obstetricsand Gynaecology Trust) 1991;11:117-8.

56 Stovall T, Ling F, Morgan P. A prospective randomizedcomparison of the Pipelle endometrial sampling devicewith the Novak curette. Am Jf Obstet Gynecol 1991;165:1287-9.

57 Chambers J, Chambers S. Endometrial sampling: When?Where? Why? With what? Clin Obstet Gynecol 1992;35:28-9.

58 Gillespie A, Nichols A. The value of hysteroscopy. AustNZJf Obstet Gynaecol 1994;34:85-7.

59 Intercontinental Medical Statistics. UK and Ireland: IMS,1994.

60 Consumer's Association. Drugs for menorrhagia: oftendisappointing. Drug Ther BuU 1990;28(5):17-9.

61 Higham J, Shaw R. Risk-benefit assessment of drugs usedfor the treatment of menstrual disorders. Drug Safety1991;6:183-91.

62 Nilsson CG. Comparative quantitation of menstrual bloodloss with a d-norgestrel-releasing IUD and a Nova-T-copper device. Contraception 1977;15:379-87.

63 Gallegos AJ, Aznar R, Merino G, Guizer E. Intrauterinedevices and menstrual blood loss. A comparative study ofeight devices during the first six months of use.Contraception 1978;17:153-61.

64 Milsom I, Andersson K, Andersch B, Rybo G. Acomparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid, and alevonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive devicein the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Am J ObstetGynecol 1991 ;164:879-83.

65 Cameron IT, Leask R, Kelly RW, Baird DT. The effectsof danazol, mefenamic acid, norethisterone and a

progesterone-impregnated coil on endometrial prostag-landin concentrations in women with menorrhagia.Prostaglandins 1987;34:99-1 10.

66 Cameron IT. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. BaillieresClin Obstet Gynaecol 1989;3:315-27.

67 Chimbira TH, Anderson ABM, Naish C, Cope E,Turnbull AC. Reduction of menstrual blood loss bydanazol in unexplained menorrhagia: lack of effect ofplacebo. BrJr Obstet Gynaecol 1980;87:1 152-8.

68 Higham JM, Shaw RW. A comparative study of danazol,a regimen of decreasing doses of danazol and norethin-drone in the treatment of objectively proven unexplainedmenorrhagia. AmJ3 Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:1134-9.

69 Dockeray CJ, Sheppard BL, Bonnar J. Comparisonbetween mefanamic acid and danazol in the treatment ofestablished menorrhagia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1989;96:840-4.

70 Callender ST, Warner GT, Cope E. Treatment ofmenorrhagia with tranexamic acid. A double-blind trial.BMJ 1970;4:214-6.

71 Vermylen J, Verhaegen-Declercq ML, Verstraete M,Fierens F. A double blind study of the effect of tranexamicacid in essential menorrhagia. Thrombosis et DiathesisHaemorrhagica 1968;20:583-7.

72 Nilsson L, Rybo G. Treatment of menorrhagia with an

antifibrinolytic agent, tranexamic acid (AMCA). ActaObstet Gynecol Scand 1967;46:572-80.

73 Ylikorkala 0, Viinikka L. Comparison between anti-fibrinolytic and antiprostaglandin treatment in thereduction of increased menstrual blood loss in women

with intrauterine contraceptive devices. Br J ObstetGynaecol 1983;90:78-83.

74 Andersch B, Milsom I, Rybo G. An objective evaluationof flurbiprofen and tranexamic acid in the treatment of

221

Coulter, Long, Kelland, O'Meara, Sculpher, Song, Sheldon

idiopathic menorrhagia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand1988;67:645-8.

75 Fraser IS, Pearse C, Shearman RP, Elliott PM, McIlveenJ, Markham R. Efficacy ofmefenamic acid in patients witha complaint of menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol 1981;58:543-51.

76 Hall P, Maclachlan N, Thorn N, Nudd MWE, Taylor CG,Garrioch DB. Control of menorrhagia by the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors naproxen sodium and mefenamicacid. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1987;94:554-8.

77 Rybo G, Nilsson S, Sikstrom B, Nygren KG. Naproxen inmenorrhagia [letter]. Lancet 1981;i:608-9.

78 Davies AJ, Anderson ABM, Turnbull AC. Reduction bynaproxen of excessive menstrual bleeding in women usingintrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57:74-8.

79 Ylikorkala 0, Pekonen F. Naproxen reduces idiopathic butnot fibroma-induced menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:10-2.

80 Cameron IT, Haining R, Lumsden M-A, Thomas VR,Smith SK. The effects of mefenamic acid and nore-thisterone on measured menstrual blood loss. ObstetGynecol 1990;76:85-8.

81 Preston JT, Cameron IT, Adams EJ, Smith S. Com-parative study of tranexamic acid and norethisterone inthe treatment of ovulatory menorrhagia. Br ObstetGynaecol 1995;102:401-6.

82 Rybo G. Tranexamic acid therapy effective treatment inheavy menstrual bleeding. Clinical update on safety.Therapeutic Advances 1991;4: 1-8.

83 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.Mistletoe report. Manchester: RCOG Medical Audit Unit,1995. (Bulletin No 5.)

84 Hospital episode statistics. Vol 1. Finished consultant episodesby diagnosis, operation and specialty. London: HMSO,1995.

85 Coulter A, McPherson K. The hysterectomy debate.QuarterlyJournal of Social Affairs 1986;2:379-96.

86 Kuh D, Stirling S. Hospital care for diseases of the femalegenital organs and breast during young adult life: admis-sions, treatment and social variation in a national cohort.Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:492 (abstract).

87 Gannon M, Holt E, Fairbank J, Fitzgerald M, Milne A,Crystal A, et al. A randomised trial comparing endo-metrial resection and abdominal hysterectomy for thetreatment of menorrhagia. BM3 1991;303: 1362-4.

88 Dwyer N, Hutton J, Stirrat G. Randomised controlled trialcomparing endometrial resection with abdominalhysterectomy for the surgical treatment of menorrhagia.BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1993;100:237-43.

89 Sculpher MJ, Bryan S, Dwyer N, Hutton J, Stirrat GM.An economic evaluation of transcervical endometrialresection versus abdominal hysterectomy for the treat-ment of menorrhagia. Br Obstet Gynaecol 1993;100:244-52.

90 Pinion S, Parkin D, Abramovich D, Naji A, Alexander D,Russell I, et al. Randomised trial of hysterectomy, endo-metrial laser ablation, and transcervical endometrialresection for dysfunctional uterine bleeding. BMJ1994;309:979-83.

91 Dicker RC, Greenspan JR, Strauss LT, et al.Complications of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomyamong women of reproductive age in the United States.AmJ_ Obstet Gynecol 1982;144:841-8.

92 Shapiro M, Munoz A, Tager I, Schoenbaum S, Polk BF.Risk factors for infection at the operative site afterabdominal or vaginal hysterectomy. N Engl Jt Med 1982;307:1661-6.

93 Kovac SR, Christie SJ, Bindbeutel GA. Abdominal versusvaginal hysterectomy: a statistical model for determiningphysician decision making and patient outcome. MedDecisMaking 1991;11:19-28.

94 Mittendorf R. Aronson M, Berry R, Williams M,Kupelnick B, Klickstein A, et al. Avoiding seriousinfections associated with abdominal hysterectomy: ameta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis. Am ObstetGynecol 1993;169: 1119-24.

95 Jacobs S, Blumenthal N. Endometrial resection follow up:late onset of pain and the effect of depot medroxy-progesterone acetate. Br Obstet Gynaecol 1994;l01:605-9.

96 Loffer F. Hysteroscopic endometrial ablation with theNd:YAG laser using a nontouch technique. Obstet Gynecol1987;69:679-82.

97 Goldfarb H. A review of 35 endometrial ablations usingthe Nd:YAG laser for recurrent menorrhagia. ObstetGynecol 1990;76:833-5.

98 Bent A, Ostergard D. Endometrial ablation with theNd:YAG laser. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:923-5.

99 Slade R, Ahmed A, Gillmer M. Problems with endometrialresection [letter]. Lancet 1991;337:1473-4.

100 Pyper R, Haeri A. A review of 80 endometrial resectionsfor menorrhagia. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol 1991;98:1049-54.

101 McClure N, Mamers PM, Healy DL, Hill DJ, LawrenceAS, Wingfield M, et al. A quantitative assessment ofendometrial electrocautery in the management ofmenorrhagia and a comparative report of argon laserendometrial ablation. GynaecolEndosc 1992;1:199-202.

102 Rankin L, Steinberg L. Transcervical resection of theendometrium: a review of 400 consecutive patients. BrJObstet Gynaecol 1992;99:91 1-4.

103 Broadbent M, Magos AL. Endometrial resection followup: late onset of pain. BrJ Obstet Gynaecol (in press).

104 Irwin KL, Lee NC, Peterson HB, Rubin GL, Wingo PA,Mandel MG, and the Cancer and Steroid HormoneStudy Group. Hysterectomy, tubal sterilization, and therisk of breast cancer. Am

_J Epidemiol 1988;127:1192-201.

105 Sandberg S, Barnes B, Weinstein M, Braun P. Electivehysterectomy: benefits, risks and costs. Med Care 1985;23:1067-85.

106 Speroff T, Dawson NV, Speroff L, Haber RJ. A risk-benefit analysis of elective bilateral oophorectomy: effectof changes in compliance with estrogen therapy onoutcome. Am Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:165-74.

107 Van Eijkeren MA, Christiaens G, Geuze H, Sixma J.Effects of mefenamic acid on menstrual hemeostasis inessential menorrhagia. Am Jf Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1419-28.

108 Muggeridge J, Elder MG. Mefenamic acid in the treatmentof menorrhagia. Research and Clinical Forums 1983;5:83-8.

109 Guillebaud J, Anderson ABM, Turnbull AC. Reduction bymefenamic acid of increased menstrual blood lossassociated with intrauterine contraception. Br Jf ObstetGynaecol 1978;85:53-62.

110 Fraser IS, McCarron G. Randomized trial of twohormonal and two prostaglandin-inhibiting agents inwomen with a complaint of menorrhagia. Anust rNZJ ObstetGynaecol 1991;31:66-70.

111 Chamberlain G, Freeman R, Price F, Kennedy A, GreenD, Eve L. A comparative study of ethamsylate andmefenamic acid in dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Br IObstet Gynaecol 1991;98:707-71 1.

112 Makarainen L, Ylikorkala 0. Ibuprofen prevents IUDCD-induced increases in menstrual blood loss. Br ObstetGynaecol 1986;93:285-8.

113 Roy S, Shaw ST. Role of prostaglandin in IUD-associateduterine bleeding: effect of a prostaglandin synthetaseinhibitor (Ibuprofen). Obstet Gynecol 198 1;58: 101-6.

114 Kasonde JM, Bonnar J. Effect of ethamsylate and amino-caproic acid on menstrual blood loss in women usingintrauterine devices. BMJ 1975;ii:21-2.

115 Harrison RF, Campbell S. A double-blind trial ofethamsylate in the treatment of primary and intrauterinedevice menorrhagia. Lancet 1976;ii:283-5.

116 Vargyas JM, Campeau JD, Mishell DR. Treatment ofmenorrhagia with meclofenamate sodium. Am ObstetGynecol 1987;157:944-50.

117 Ingemanson CA, Sikstrom B, Rybo G, Bjorkman R.Double blind, placebo controlled evaluation of diclofenacin the management of patients with IUD relatedmenorrhagia. Adv Ther 1991;8:287-92.

Table 1 Randomised controlled tials ofdrug treatment of menorrhagia*Trial Selection criteria Intervention Outcome Duration Results (change in menstrual blood loss; side effects)

measures

Fraser et al Women with convincing Mefenamic acid (500 mg three Menstrual 4 Months (2 Mefenamic acid 28% reduction for all women,198175 history of menorrhagia, times daily) during period and blood loss, months each) 30% for > 80 ml, 19% for < 80 mlenrolled through placebo menstrual 19% Dropout Side effects: no significant differences betweenradio/television discussion. Group A: > 80 ml symptoms, mefenamic acid and placeboSubjective. No pretreatment Group B: < 80 ml pain, pad andcontrol cycles Group C: < 35 ml tampon usage,Trial: crossover, double blind side effectsSize: A= 30, B = 39, C = 14

Van Eijkeren Women under 45 years Group A: mefenamic acid Menstrual 2 Months Mefenamic acid 40% reduction v 25% increaseet al 1992"' scheduled for hysterectomy, (500 mg three times daily from 5 blood loss 42% Dropout for placebo groupmenstrual blood loss > 80 ml. days before period until bleeding Side effects: mefenamic acid: stomach pains 1,One pretreatment control ceases) itching 2, placebo: headache 1, itching 1cycle Group B: placeboTial: double blind Hysterectomy during secondSize: A = 6, B = 5 menstruation

Muggeridge Menstrual blood loss > 75 ml Mefenamic acid (500 mg three Menstrual 4 Months (2 Mefenamic acid 30% reduction, placebo 12%and Elder Trial: crossover, double blind times daily started at onset of blood loss, months each) reduction1983108 Size: N = 15 period) and placebo dysmenorrhoea 25% Dropout Side effects: incidence low, no difference betweengroups

222

Managing menorrhagia

Table 1 continued

Tial Selection criteria Intervention Outcome Duration Results (change in menstrual blood loss; side effects)measures

Guillebaud Healthy, parous women usinget al 1978"' IUDs. Menstrual blood loss

measured before entryTrial: crossover, single blindSize: A = 15, B = 10

Bonnar(paperpresented atRoyal Societyof Medicinemeeting,London,1994)

Menstrual blood loss > 80 mlTrial: double blindSize:A =27, B=25, C=29

Fraser and Convincing clinical history ofMcCarron menorrhagia1991"° Trial: crossover (2 drugs

each), not blindedSize: A = 15, B = 15, C = 15

Cameron et al Menstrual blood loss > 80 ml1990"o Trial: random allocation to

either treatmentSize:A= 17,B= 15

Hall et al Dysfunctional uterine1987'6 bleeding. Menstrual blood

loss measured before entryTrial: crossover, doubledummySize: A = 18, B = 18

Dockeray et al Menstrual blood loss > 80 ml198969 Trial: not clear if blinded

Size: A = 19, B = 20

Cameron et al1987,6'Cameron198966

Menstrual blood loss > 50 mlTrial: random allocationSize: A = 6, B = 8, C = 8,D=8

Mefenamic acid (500 mg twicedaily from onset till bleedingceased) and placeboGroup A: > 80 mlGroup B: < 80 ml

Treatment for 5 days duringcycleGroup A: tranexamic acid (1 gfour times daily)Group B: mefenamic acid(500 mg three times daily)Group C: ethamsylate (500 mgfour times daily)

Group A: mefenamic acid andnaproxen (500 mg, 250 mg for 5days)Group B: mefenamic acid andoral contraception (low doseonce daily 21 days)Group C: mefenamic acid anddanazol (200 mg once daily fromday 5 of cycle)All groups: mefenamic acid500 mg three times daily or fourtimes daily on days 1 tomaximum of 5

Group A: mefenamic acid(500 mg three times daily ondays 1-5 of period)Group B: norethisterone (5 mgtwice daily on days 19-26 ofcycle)

Group A: naproxen sodium(550 mg initially then 275 mgfour times daily for 5 days) thenmefenamic acid (500 mg threetimes daily)Group B: mefenamic acid thennaproxen sodium

Group A: mefenamic acid(500 mg three times daily for3-5 days beginning of periodGroup B: danazol (100 mg twicedaily for 60 days beginning lastday of period)

Group A: danazol (200 mg oncedaily)Group B: mefenamic acid(500 mg three times daily fordays 1-5 of period)Group C: norethisterone (5 mgtwice daily from day 15-25 ofcycle)Group D: progestasert coil(releasing 65 ,ug progesteronedaily)

Menstrualblood loss,duration ofmenses, sideffects

4 Months Group A: mefenamic acid 34% reduction;34% Dropout group B: mefenamic acid 23% reduction

Side effects: indigestion 1, headaches anddizziness 1 (both withdrew)ie

Menstrual 3 Months Group A: 58% reduction; group B: 25%blood loss, side 27% Dropout reduction; group C: 0% reductioneffects Side effects: A = 4, B = 5, C = 13

Menstrual 6 Months Mefenamic acid 3 1% reduction, naproxen 12%blood loss 16% Dropout reduction, oral contractives 43% reduction and

danazol; 50% reductionSide effects: not reported

Menstrual 2 Months Mefenamic acid 24% reduction, norethisteroneblood loss, 0% Dropout 20% reductionduration, side Side effects: mefenamic acid 10, norethisteroneeffects 1 1, including headache, abdominal pain, and

nausea

Menstrual 4 Months Mefenamic acid 46% reduction, naproxenblood loss, 15% Dropout sodium 47% reductionpatient and Side effects: gastrointestinal (nausea, diarrhoea,doctor abdominal discomfort, and anorexia): naproxenpreferences, sodium 13, mefenamic acid 6; central nervousside effects system (light headedness, dizziness, tiredness,

and headache): mefenamic acid 6, naproxensodium 5

Menstrual 2 Months Mefenamic acid 22% reduction, danazol 56%blood loss, 3% Dropout reductiondysmenorrhoea, Side effects: mefenamic acid 11 events, danazolside effects, 51 eventspatientacceptability

Menstrual 2 Months Danazol 7 1/% reduction, mefenamic acid 25%blood loss, 0% Dropout reduction, norethisterone increase 12%,prostaglandin progestasert coil 23% reductionmeasurement Side effects: not reported

Chamberlain Women aged 18-55, withet al 1991111 regular cycles and menstrual

blood loss > 80 mlTrial: double dummy, doubleblind, allocation byminimisationSize:A= 16,B= 18

Callender et al Women and anaemia,1970'° complaining of menorrhagia

with no abnormalityTial: crossover, double blindSize: n = 16

Vermylen et al History of menorrhagia.1968"' Subjective

Tial: crossover, double blindSize: n = 16

Nilsson and Women aged 15-49 withRybo 1967'" suspected menorrhagia.

SubjectiveTrial: crossover, double blind

Size: n = 36

Group A: ethamsylate (500 mgfour times daily during period)Group B: mefenamic acid(500 mg three times daily duringperiod)

Tranexamic acid (500 mg fourtimes daily for first 4 days ofperiod)Placebo

Tranexamic acid (500 mg 4hourly from day 1 till bleedingstops)Placebo

Low dose tranexamic acid(250 mg 4 hourly)High dose tranexamic acid(500 mg 4 hourly)Placebo

Menstrual 4 Monthsblood loss, side 23% Dropouteffects

Menstrualblood loss(Oxford totalbody counter),duration,number of pads,side effects

Meanhaemoglobinloss, pads used,side effects

Menstrualblood loss, sideeffects

Ethamsylate 20% reduction, mefenamic acid24% reductionSide effects: ethamsylate 5, mefenamic acid 10(abdominal discomfort, headache mostcommon)

6 Months Tranexamic acid 36%, placebo 6% reduction20% Dropout Side effects: tranexamic acid 2, placebo 2

6 Months Tranexamic acid 35% reduction. No blood loss36% Dropout reported, just percentage

Side effects: no difference between groups

3 Months Low dose tranexamic acid 38% reduction, high0% Dropout dose 51/% reduction, placebo 8% reduction

Side effects: Low dose 7, high dose 13, placebo 8(mainly diarrhoea and abdominal pain)

223

Coulter, Long, Kelland, O'Meara, Sculpher, Song, Sheldon

Table 1 continued

Trial Selection criteria Intervention Outcome Duration Results (change in menstrual blood loss; side effects)measures

Ylikorkala Women with intrauterineand Viinikka devices and menstrual blood198373 loss > 70 ml

Trial: crossover, double blindSize: n = 19

Andersch et al Women aged 34-49 with1988'4 menstrual blood loss > 80 ml

Tial: crossover, openSize: n = 15

Tranexamic acid (1-5 g three Menstrualtimes daily for 5 days) blood loss,Diclofenac sodium (50 mg three duration,times daily day 1 and 25 mg intermenstrualthree times daily for 4 days) bleeding, side

effects,restrictedactivity, pelvicpain, subjectiveassessment

Tranexamic acid (1-5 g three Menstrualtimes daily for 3 days, 1 g twice blood loss,daily during days 4 and 5) duration, sideFlurbiprofen (100 mg twice daily effectsfor 5 days)

5 Months Tranexamic acid 56% reduction, diclofenac10% Dropout sodium 24% reduction

Side effects: tranexamic acid 12, diclofenacsodium 5

4 Months Tranexamic acid 53% reduction, flurbiprofen0% Dropout 24% reduction

Side effects: tranexamic acid 7, flurbiprofen 4

Milsom et al Menstrual blood loss > 80 ml199164 and no pelvic pathology

Tial: first 20 women givenIUD, next 15 randomised tocrossover designSize: IUD = 16, drugs 15

IUD group: levonorgestrel IUD(release rate of20 Ag/day)Drugs group: Flurbiprofen(100 mg twice daily for 5 days)crossover with: tranexamic acid(1-5 g three times daily for days1-3, then 1 g twice daily for days4 and 5)

Menstrual 4 Monthsblood loss, side 111% Dropouteffects

IUD: 82% reduction at 3 months, 88%reduction at 6 months, 96% reduction at 12monthsDrugs: flurbiprofen 21% reduction andtranexamic acid 44% reductionSide effects: tranexamic acid 7, flurbiprofen 4

Chimbira et al Women referred to Group A: placebo198067 gynaecology outpatient clinics Group B: danazol (200 mg once

with menstrual blood loss daily for 12 weeks)> 60 ml Group C: danazol (100 mg onceTial: single blind daily for 12 weeks)Size: A= 8, B = 16, C = 16

Women complaining of High dose: Ibuprofen (400 mgexcessive menstrual bleeding three times daily)and primary menorrhagia Low dose: Ibuprofen (200 mg> 70 ml menstrual blood loss. three times daily)No pretreatment control cycle PlaceboTrial: double blind, crossover

Size: n = 13

Roy and Shaw Healthy volunteers who had Ibuprofen (400 mg four times1981113 used IUD for at least 5 daily)

months with no side effects. PlaceboSubjective. One pretreatmentcontrol cycleTrial: double blind, cross over

Size: n = 20

Kasonde and Women complaining ofBonnar excessive menstrual bleeding19751 4 while using intrauterine

devicesTrial: openSize:AA= ll,B= 12

Harrison and Women with primaryCampbell menorrhagia. IUD users also1976"5 recruited. One pretreatment

control cycle.Trial: double blind, crossover

Size:A=9,B= 13

Group A: ethamsylate (500 mgfour times daily during period)Group B: EACA (3 g four timesdaily during period)

Ethamsylate (500 mg four timesdaily five days before onset andfor 10 days)PlacbeoGroup A: primary menorrhagiaGroup B: IUD users

Menstrualblood loss,duration, sideeffects

Menstrualblood loss,duration, pain,side effects

5 Months Danazol (200 mg) 86% reduction, danazol0% Dropout 100 mg 75% reduction, placebo no change

Side effects: tiredness 5, musculoskeletal pain 4,skin rashes 3, headaches 6, irritability 3,vaginitis 3, average weight gain 2-3 kg

3 and 6Months23% Dropout

High dose ibuprofen 25% reduction, low dose16% reductionSide effects: high dose 5 (including headache,dizziness, nausea, diarrhoea, and dyspepsia),low dose 6

Menstrual 2 Months Ibuprofen, overall 32% reduction, placebo 6%blood loss 0% Dropout increase. Mean values not given

Side effects: ibuprofen 2 (swelling around eyesand mouth, mild stomach cramps), placebo 2(mild stomach cramps and nausea, headaches,and dizziness)

Menstrual 4 Months Ethamsylate 7% reduction, EACA 50%blood loss 8% Dropout reduction

Side effects: not reported

Menstrual 4 Monthsblood loss, side 29% Dropouteffects

Ethamsylate 50% reduction in primarymenorrhagia group, 19% reduction IUD group,no change for placebo groupSide effects: reported in 18/53 ethamsylate cyclesand 17/50 placebo cycles but reportedly notserious

Rybo et al Women with primary Naproxen (500 mg in morning, Menstrual198177 menorrhagia. Women without then 250 mg in afternoon for 2 blood loss

primary menorrhagia were days, then 250 mg twice daily forfitted with IUD up to 7 days)Tral: double blind, cross over Placebo

Size: A = 4, B = 5, C = 5 Group A: primary menorrhagiaGroup B: IUD and menstrualblood loss > 80 mlGroup C: IUD and menstrualblood loss < 80 ml

Davies et al Women using IUDs and198 178 menstrual blood loss > 80 ml

Tial: double blind, crossoverSize: n = 34

High dose: naproxen (500 mgtwice daily, plus 250 mg oncedaily for 5 days)Low dose: naproxen (500 mgloading dose then 250 mg threetimes daily for 5 days)

Ylikorkala Menstrual blood loss > 80 ml Naproxen (250 mg four timesand Pekonen Tial: double blind, crossover daily for days 1-5 of cycle)

Size: n = 14Pl

Gallegos et al Women volunteers selected197863 from those requesting an

IUD. Menstrual blood lossmeasured but all < 80 ml.One or two pretreatmentcontrol cyclesTrial: IUDs randomlyallocatedSize:A=7,B= 10,GC= 10,D=7

Group A: UPS-40 (releases40 ,ug/day progesterone)Group B: UPS-65 (releases65 pg/day progesterone)Group C: Norethisterone IUD(releases 10 pg/dayprogesterone)Group D: Levonorgestrel IUD(releases 2 pg/day ofprogesterone)

Menstrualblood loss, padsand tamponsused, intensityof bleeding,assessment ofdrug effect, sideeffects

Menstrualblood loss,duration, sideeffects

4 Months Group A: naproxen 24% reduction0% Dropout Group B: 38% reduction

Group C: 9% reductionPlacebo: 2-4% reductionSide effects: not reported

4 Months High dose 32% reduction, low dose 22%29% Dropout reduction

Side effects: no adverse reactions to naproxen, 1patient with nausea/vomiting

4 Months Naproxen 3/6% reduction, placebo 11% increase0% Dropout Side effects: mild side effects with placebo 1,

none with naproxen

Menstrual 6 Months UPS-40 34% increase (not significant), UPS-65blood loss O0/a Dropout 40% reduction, norethisterone releasing IUD

33% reduction, and levonorgestrel releasingIUD 47% reductionSide effects: not given

MakarainenandYlikorkala1986112

224

Managing menorrhagia

Table 1 continued

Tial Selection criteria Intervention Outcome Duration Results (change in menstrual blood loss; side effects)measures

Nilsson Women volunteers from Group A: d-norgestrel-releasing Menstrual 3 Months d-norgestrel-releasing IUD 60% reduction197762 hospital staff, not IUD (releases 25 pug daily) blood loss 0% Dropout Side effects: none given

menorrhagic Group B: copper IUDTrial: random allocation toIUDSize:A= 10,B=9

Vargyas et al Women aged 16-42 with Meclofenamate sodium (100 mg Menstrual 4 Months Meclofenamate sodium 49% reduction, placebo1987"'6 menstrual blood loss > 60 ml three times daily for 6 days or blood loss, 9% Dropout 4% reduction

Trial: double blind, crossover until bleeding ceased) duration, Side effects: dysmenorrhoea, backache, headacheSize: n = 29 Placebo dysmenorrhoea, less severe on active drug, nausea and vomiting;side effects, no difference between groups

pads andtampons used

Higham and Women aged 20-50 with Group A: danazol (dose reduced Menstrual 3 Months (4 Danazol reducing dose 28% reduction, 200 mgShaw 199368 proved menorrhagia each cycle: 200 mg, 100 mg, blood loss, months after dose 40% reduction

Tial: single blind 50 mg once daily) duration, treatment) Side effects: reducing dose 15 women, 200 mgSize: A = 17, B = 19, C = 18 Group B: danazol (200 mg once interval between 24% Dropout dose 17, placebo 11

daily) cycles,Group C: Norethindrone (5 mg dysmenorrhoea,three times daily days 19-26) subjective

assessment, sideeffects

Ingemanson Women using IUDs and Diclofenac (50 mg three times Menstrual 4 Months Diclofenac 29% reduction, placebo 4%et al 1991i" menstrual blood loss > 80 ml daily for 5 days of period) blood loss, 0% Dropout reduction

Trial: double blind, crossover Placebo duration, Side effects: None attributed to diclofenacSize: n = 9 subjectiveassessment, side

effects

Preston et al Women complaining of Group A: tranexamic acid (1 g Menstrual 2 Months Tranexamic acid 45% reduction, norethisterone19958" menorrhagia, actual four times daily, days 1-4) blood loss, 9% Dropout 20% increase

menstrual blood loss > 80 ml Group B: norethisterone (5 mg subjective Side effects: tranexamic acid 8 headaches and 3Tial: double blind twice daily on days 19-26) assessment, side gastric, norethisterone 10 headache and 7Size: A = 25, B = 21 effects gastric

*All trials included at least 2 pretreatment control cycles except if otherwise indicated.EACA = e-amino caproic acid.IUD = intrauterine device.

Table 2 Randomised controlled trials ofsurgical treatment of menorrhagia

Tial Selection criteria Outcome measures Follow up Results

Dwyer et al Women aged < 52 (mean 40) Requirement for analgesia; 4 Months, with a 2% Postoperative morbidity, length of stay and199388 years complaining of menorrhagia complications; postoperative recovery dropout rate time taken to return to work, normal dailySculpher et al which could not be controlled by time; menstrual status; sexual activity; 69% completed the activities, and sexual intercourse were199389 conservative means and who were psychiatric morbidity using the 60 EuroQol' health significantly lower in the endometrial group.Sculpher et al, candidates for hysterectomy, item general health questionnaire questionnaire sent at Premenstrual symptoms, symptoms ofpersonal attending the gynaecological Self recording of degree of pain each 4 months after the dysmenorrhoea, bloating and breast tendernesscommunication department of Bristol's teaching day for a week; booklet recording operation were less frequent after hysterectomy. After1995 hospital postoperative problems, amount and At an average of 2.2 endometrial resection, 13 women were

Exclusions: women with uterine duration of vaginal bleeding, date of years, loss to follow amenorrhoeic while 76 had hypomenorrheasize > 12 weeks, additional return to work and normal daily up: 46(47%) of the women having a hysterectomysymptoms or other disease made activities Group A: 25% had complications compared to 4(4%) of thosehysterectomy the preferred Failure rate of endometrial resection, Group B: 17% having an endometrial resection. Only onetreatment. Histological as assessed by the number ofwomen woman having a hysterectomy did not requireassessment of the endometrium not satisfied or who had severe analgesia for postoperative pain compared withwas undertaken if hyperplasia due synechiae 39 of the endometrial resection groupto anovulatory menstruation was Degree of satisfaction with operation After 4 months there was a significantanovueatoy4 months after operation difference in satisfaction in favour of

196 of 216 women found suitable Restricted version of EuroQol' health hysterecthmhe94rslts of their treyatment)andand agreeing to participate qusinarcmltdamnumstsidwtthreusofhirramn)adrandomly allocated 2 groups questionnaire, completed a minimum no significant difference in EuroQol' scores

of 4 months after theoperationA4motsteewsfiuereofalatA: abdominal hysterectomy (97) asking the women to value their At 4 months there was failure rate of at leastB: endometrial resection (99) health on average, 1 month before 10-15% in those in whdoplteometrialNote: 43(44%) in group A v and 2 weeks after the operation, and rejection appeared complete. At 2-8 years the34(34%) in group B had at the time of completing the cumulative probability of a repeat rejection waspreintervention GHQ scores of questionnaire 12% and of a hysterectomy 16%, an overall¢ 12 SF 36 questionnaire completed as 23%

part of longer term follow-up togetherwith the EuroQol' questionnaire

Gannon et al Women aged 29-51 (median 40) Requirement for analgesia; 9-16 Months (mean Recovery after endometrial resection was199187 years awaiting abdominal complications; postoperative recovery 12 months) substantially shorter (median 16 days) than for

hysterectomy for menorrhagia at time; menstrual status Loss to follow up: not hysterectomy (median 58 days). Twelve (46%)Royal Berkshire Hospital Diary record of symptoms after reported women in the hysterectomy group hadReading, found suitable after discharge from hospital, noting first complications, and none of the women whohistory, physical examination, and day without analgesic drugs, date felt had endometrial resection. Four (16%) womenpelvic ultrasonography with a fit to return to work who had endometrial resection required anyvaginal probe Women requiring hysterectomy or a postoperative analgesiaExclusions: women known to repeat hysteroscopic procedure Four (1 6%) women had repeat resections;have leiomyomata, endometrial or none required a hysterectomy within the meancervical neoplasia, concomitant follow up of one yearovarian disease, pelvic Mean theatre and ward costs for endometrialinflammatory disease, or resection were £407 and for hysterectomyendometriosis £127051 of 78 women without pelvic Authors point to the need for larger numberspathology on the waiting list and and longer follow up to estimate complicationsconsenting to participate, and long term efficacy of endometrial resectionallocated randomly to 2 groups:A: abdominal hysterectomy (26)B: endometrial resection (25)

225

Coulter, Long, Kelland, O'Meara, Sculpher, Song, Sheldon

Table 2 continued

Trial Selection criteria Outcome measures Follow up Results

Pinion et al Women attending general Requirements for analgesia; 12 Months Women treated by hysteroscopic surgery had19949° gynaecological clinics at complications; postoperative recovery Non-attenders for less morbidity and a significantly shorter

Aberdeen's teaching hospital, time; menstrual status; urinary, follow up: recovery period than those treated byaged under 50, weighing under incontinence, premenstrual and at 1 month: 5% hysterectomy. Five women in the hysterectomy100 kg, with a clinical diagnosis of menopausal symptoms and at 6 months: 12% group had major complications, two fromdysfunctional uterine bleeding dyspareunia at 12 months: 90% anaesthesia, one from intra-abdominal(uterus less than size of a Woman's grading of heaviness and bleeding, and two had pelvic abscesses. Onepregnancy of 10 weeks, and pain for each day of the period woman given laser ablation had a small bowelnormal endometrial history), and P a.if "How d obstructionwho would otherwise have Peatient arwtsaifcinthow doesr ygour 16flO of the women in the hysteroscopic groupundergone a hysterectomy health compare with that a yearago?haa ytrcmninh hstesb°igouundergnea ysterctomy What effect has the operation had on had a hysterectomy 12 months subsequently;204 women allocated at random symptoms? How satisfied are you with 10% a repeat hysteroscopic procedure; 43%to 3 groups: the effect of treatment" were amenorrhoeic or had only a brownA: hysterectomy (99) Women requiring hysterectomy or a discharge and 33% had light periodsB: endometrial laser ablation (53) repeat hysteroscopic procedure After 12 months 89% of the hysterectomyC: transcervical resection of randomisation, group (78% of the hysteroscopic group) wereendometrium (52) Data collected beforenthsater very satisfied with the effect of surgery;Note: study focuses on a and at 1,6, and 12 months after 95%(90%) thought there had been ancomparison between acceptable improvement in symptoms;hysterectomy and hysteroscopic 73%(48%) indicated that their health wassurgery as insufficient power to much better than a year previouslyexplore for differences betweenlaser ablation and endometrialresection

Hormonereleasing coil

Danazol

Tranexamicacid

Mefenamicacid

Naproxen

Ibuprofen

Ethamsylate

% Menstrual blood increase20 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Diclofenac

Norethisterone * *

Placebo * * * *** *

70 80No of

patients

* ** 93

109

172

282

133

76

78

19

44

188

Estimated change in menstrual blood loss in each arm of different drug trials

226

*

-W*w -W * * *