Literature Review Memo - Labor and Worklife Program

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Literature Review Memo - Labor and Worklife Program

1

Rebalancing Economic and Political Power:

A Clean Slate for the Future of American Labor Law

Literature Review Memo [Clean Slate IA – Levels of Bargaining]*

Table of Contents

1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 2

2. The Problem ................................................................................................................................. 4

3. U.S. Historical and Industry-Specific Parallels ............................................................................. 8

4. Supply Chain Bargaining ............................................................................................................ 15

5. Synthesis of International Sectoral Bargaining Models ............................................................... 22

6. Case Study: Mechanics of Sectoral Bargaining in Norway and South Africa ............................... 34

7. Survey of Bargaining Schemes Abroad ....................................................................................... 43

* This report was researched and drafted by Jared Odessky and Will Dobbs-Allsop in consultation with, and with contributions from, members of the Clean Slate IA group.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

2

1. Introduction

The overall mission of “Clean Slate” is to increase worker power in the United States. To achieve that mission, it is essential to extend collective bargaining coverage, now at the low end of industrial democracies. Over the last 65 years, U.S. private sector collective bargaining coverage has decreased from 35% to 6%. While public sector coverage has increased to 30%, it remains at the low end compared to other nations—and is under threat in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in Janus.

A legal system in which working people can gain a right to bargain only at the enterprise level is a significant cause—perhaps the most significant cause—of employer opposition to organizing and intransigence in collective bargaining in the U.S. Each employer fears that if its employees organize, it will be placed at a competitive disadvantage by the results of collective bargaining. This intransigence has been abetted by the financial markets and management compensation schemes that discount long term economic performance and social responsibilities, as well as by global product and labor markets.

A persistent aspiration of the labor movement has been to “take wages out of competition.” In other words, the labor movement seeks to prevent employers from competing by cutting wages or benefits or worsening working conditions. In a market economy, unless unions can take wages out of competition, there will be steady downward pressure on wages and benefits and employers will resist efforts to raise economic standards and working conditions, particularly through enterprise-level collective bargaining.

Stable collective bargaining leading to rising wages and expanded benefits and job security has existed in the U.S. when unions have found mechanisms to take wages out of competition. Historically these mechanisms have been multi-employer bargaining and pattern bargaining. More recently, unions have sought to use master agreements, common expiration dates, “trigger agreements” (agreements conditioning application of economic terms on reaching a set percentage of signatories in a geographic market), and the revival of tripartite wage boards (leading to government-mandated minimum or living wages).

In other counties, particularly Western Europe, bargaining has historically taken place at a “higher” level, both national and sectoral. In some of these countries, collectively bargaining agreements are “extended” across a sector when specified conditions are met.

The key question for our group is what are the legal mechanisms that would facilitate a form of collective bargaining that would effectively take wages out of competition and permit working people in the U.S. to organize, have stable representation, and effectively improve wages, benefits and working conditions for all workers?

More specifically, we will investigate:

• In what countries and historical time periods have bargaining systems been most successful, when, and by what metrics? What models have achieved the greatest collective bargaining coverage and expanded worker power in the economy and in politics? What historical factors enabled the establishment of sectoral or other higher-level bargaining bargaining?

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

3

• How have structural characteristics—including fissuring, precariousness, isolation of workers, lack of a single physical worksite, and globalization—posed a barrier to successful collective bargaining?

• How did law historically facilitate or inhibit sectoral or supply chain bargaining in the U.S.?

• How has composition of the workforce (race, national origin, immigration status, gender) posed

a barrier to successful collective bargaining in the United States? [NB: Possibly for another group].

In countries where sectoral bargaining exists:

• To what extent does the law mandate such bargaining? To what extent is the government involved in facilitating or mandating bargaining, or in extending the fruits of bargaining?

• Who represents workers in bargaining? Who represents employers? Who decides? How are nonunion workers represented?

• How are sectors defined? Who decides? What sectors are covered? What mechanisms exist to

make bargaining inclusive of all sectors?

• What bargaining occurs at national level, regional level, sectoral level, or worksite level? That is, who participates in the different levels of bargaining and what subjects are bargained over at each level? How does sectoral bargaining interact with worksite bargaining?

• Where has supply chain bargaining been achieved? What legal mechanisms can encourage or

require it? How does it interact with sectoral or worksite bargaining?

• What other reforms aimed at increasing workers’ collective economic power, including organizing rights and strike rights, are need in order for higher levels of bargaining to succeed?

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

4

2. The Problem

“As an increasing number of scholars and commentators have recently argued, worksite-or firm-based bargaining is often insufficient to protect workers’ interests and to redress problems of economic and political inequality.”1 Enterprise collective bargaining in the United States has contributed to some of the structural failures that plague the larger labor law regime:

● Distributional effects: Firm- and enterprise-based bargaining incentivizes companies to

“compete to keep labor costs down, whether by setting wages at a low level, skirting legal obligations, or avoiding unionization.”2

● Workplace democracy: Worksite-level bargaining can provide workers a voice at work, but it also limits worker-voice. “Non-unionized workers typically have no way to participate in decisions around wages and benefits or other questions important to their daily lives … even unionized workers are outmatched against continental-scale corporations.”3

● Policy alternatives: Administrative substitutes to large-scale collective bargaining, such as “federal and state minimum standards laws, are fairly blunt tools, as they impose identical obligations on nearly all covered companies.”4 They have proved hard to adjust and do not account for differences across industries or, in the case of the federal minimum wage, geographic region.

● Outsourcing & diffused supply chains: “Firm-level bargaining has become even less effective in recent years as companies have contracted out work and directly employed fewer people.”5 “Work that was once done in-house is increasingly scattered across multiple employers interconnected by a chain or network of contracts. This disintegration … has many baleful consequences, including the swelling of the precarious, low-wage labor market.”6

One solution to these problems is for the U.S. to transition to some type of sectoral bargaining

system, whereby workers negotiate at the “at the sectoral level—for example, among all fast food workers, all retail workers, all hotel/motel workers, all janitors—either nationally or in a given

1 KATE ANDRIAS AND BRISHEN ROGERS, REBUILDING WORKER VOICE IN TODAY’S ECONOMY 26 (The Roosevelt Inst. 2018), https://www.scribd.com/document/385584703/Rebuilding-Worker-Voices-In-Today-s-Economy#download&from_embed. 2 Id. 3 Id. at 27. 4 Id. 5 David Madland, Wage Boards for American Workers, CTR. FOR AMER. PROGRESS (last updated Apr. 9, 2018), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2018/04/09/448515/wage-boards-american-workers/. 6 MARK BARENBERG, WIDENING THE SCOPE OF WORKER POWER 3 (The Roosevelt Inst. 2015), http://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Widening-the-Scope-of-Worker-Organizing.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

5

geographic region.”7 There are a few mechanisms scattered throughout U.S. labor law that enable workers to organize at a scale larger than workplace-by-workplace, but in practice these tools have been rarely used or have largely proved to be unworkable. For example, in theory multi-employer bargaining is possible, but multi-employer bargaining typically requires the assent of the companies involved.8 Historically, in the United States there have been limited examples of collective bargaining taking place at a scale higher than the firm-level9; still, “such efforts have nevertheless been the exception rather than the rule.”10

That history stands in stark contrast to the experiences in other countries, where sectoral bargaining systems have typically coincided with a far more robust labor movement. “Virtually all the European countries empower unions to negotiate employment rights for workers on a sectoral basis.”11 There, sectoral bargaining takes many forms, and often compliments – rather than replaces – labor negotiations at the enterprise level. Sectoral bargaining exists outside the European context as well. “In 1995, the new post-apartheid South African government was able to legislate sectoral collective bargaining and sectoral minimum wages as key parts of their initial economic agenda. Finance workers in Brazil bargain for their sector with employers that include all the major U.S. banks, and as a result, wage rates in the Brazilian finance sector for back-office and customer service staff are higher than those in the United States.”12 Countries that rely heavily on sectoral bargaining tend to have a higher bargaining coverage rate; in the following OECD chart, in Canada, Japan and the United States bargain is primarily at the firm level, while the United Kingdom and New Zealand are moving in that direction; in all the other countries, sectoral bargaining features prominently in the labor regime although it is under pressure across the globe.13

7 REBUILDING WORKER VOICE at 26. 8 WIDENING THE SCOPE OF WORKER POWER at 11. 9 REBUILDING WORKER VOICE at 27. 10 Id. 11 Kate Andrias, An American Approach to Social Democracy: The Forgotten Promise of the Fair Labor Standards Act 3 (forthcoming), citing STEVEN J. SILVIA, HOLDING THE SHOP TOGETHER 27-28, 38-41 (2013); Franz Traxler & Martin Behrens, Collective Bargaining Coverage and Extension Procedures, EURWORK (Dec. 17, 2002), http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/comparative-information/collective-bargainingcoverage-and-extension-procedures [https://perma.cc/JG2D-MFMP]. 12 Larry Cohen, The Time Has Comes for Sectoral Bargaining, Vol. 27(3) NEW LABOR FOR. 10, 11 (2018). 13 OECD Table 5.1 at 175. Chart is Chart 5.1 at 173. https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/2409993.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

6

Many of the countries where some form of sectoral bargaining exists also receive high marks for minimizing workers’ rights violations: Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland all received one of the two best ratings on this measure in the 2018

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

7

ITUC Global Rights Index.14 By contrast, the United States received a rating indicative of systemic violations of worker rights.15 As the Clean Slate Project begins to explore different avenues for raising the level of collective bargaining in the United States, it will be important to understand how sectoral-style bargaining has worked both domestically and abroad. To that end, what follows below is a brief summary of examples in U.S. history of labor arrangements resembling sectoral or social bargaining and an overview of the sectoral bargaining systems that exist in other countries.

14 2018 ITUC GLOBAL RIGHTS INDEX 10 (Inter. Trade Union Confed. 2018), https://da.se/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/ITUC-Global-Rights-Index-2018-EN.pdf. 15 Id.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

8

3. U.S. Historical and Industry-Specific Parallels The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) creates a system of “private collective bargaining at the firm level instead of the class-based political or social bargaining that was advocated for by [some] strands of the American labor movement and that ultimately took hold in some European countries.”16 Nonetheless, there have been moments in American history and there remain practices in particular industries in which employee bargaining has approximated a sectoral model. The analysis below examines historical and industry-specific examples of multi-employer bargaining, pattern bargaining and tripartite bargaining. Multi-Employer Bargaining

Under the NLRA, the National Labor Relations Board cannot mandate multi-employer bargaining absent employer consent. Section 9(b) of the Act provides:

The Board shall decide in each case whether, in order to assure to employees the fullest freedom in exercising the rights guaranteed by this Act [subchapter], the unit appropriate for the purposes of collective bargaining shall be the employer unit, craft unit, plant unit, or subdivision thereof.

That language has been construed to render the “employer unit” the largest unit the Board can find appropriate.

Nevertheless, employers can voluntarily choose to bargaining in a multi-employer unit if they form an association and designate the association as their agent for purposes of collective bargaining. The first case to certify a unit composed of independent and competing companies was Shipowners’ Ass’n. of the Pacific, 7 NLRB 1002 (1938). The Board explained that its “jurisdiction to go beyond the individual company in deciding upon an appropriate unit of employees,” id. at 1024, depended upon the existence of a common bargaining agent having been agreed to by the group: “The Board is . . . expressly given the authority to decide that the ‘employer’ unit is the unit most appropriate for purposes of collective bargaining. The Act includes within the term employer ‘any person acting in the interest of an employer, directly or indirectly,’ and the term person ‘includes one or more . . . associations . . . .’” Id. at 1024-25 (emphasis in original). The Board concluded that the association-wide unit met the definition of an “employer unit,” because “the associations engaged in collective bargaining for the individual companies” and thus “clearly act in the interest of these various companies.” Id. at 1025.

In other words, “the essential element warranting the establishment of multiple-employer units is clear evidence that the employers unequivocally intend to be bound in collective bargaining by group rather than individual action.” Pacific Metals Company, 91 NLRB 696, 699 (1950). In “[c]ases involving the issue of multiemployer units of separate and competing employers,” therefore, “the decisive factor . . . has been the evidence of participation in the group bargaining through a committee or other representative and the lack of evidence of any desire for

16 Kate Andrias, The New Labor Law, 126 YALE L.J. 2 (2016).

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

9

individual bargaining.” Metropolitan District Council of Philadelphia, 137 NLRB 1583, 1598-1599 (1962).

During the debates over the Taft-Hartley Act, proposals were made to limit multi-employer bargaining, but they were rejected. See NLRB v. Truck Drivers Local 449 (Buffalo Linen Supply Co.), 353 U.S. 87, 95-96 (1957).

While employer must consent to creation of multi-employer unit, neither employers nor union can withdraw from multi- employer unit during the term of an agreement or once bargaining has commenced absent consent or unusual circumstances.

In some industries, employer associations and unions negotiate master agreements for participating employers in an industry. “This practice dates back to the earliest days of collective bargaining [in the United States]. The process works to the advantage of employers seeking leverage in dealing with larger unions. Furthermore, multiemployer bargaining, if adhered to by the members, allows the employers to combat unions which engage in whipsaw tactics. Meanwhile, multiemployer bargaining potentially works to the advantage of the labor union by fostering security, creating a greater standardization of wages and working conditions under a group contract, and by enabling the union to save the time and money typically associated with bargaining with each employer on an individual basis.”17

The NLRB affords some protection to multi-employer bargaining. “When there is a history of bargaining between a union and a number of employers acting jointly, the employees who are thus represented constitute a multiemployer bargaining unit. Once such a unit has been established, any of the participating employers—or the union—may retire from this multiemployer bargaining relationship only by mutual assent or by a timely submitted withdrawal. Withdrawal is considered timely if unequivocal notice of the withdrawal is given near the termination of a collective-bargaining agreement but before bargaining begins on the next agreement.”18

Multi-employer bargaining agreements exist today in certain industries such as trucking, entertainment, and the building trades. In 1964, the Teamsters under Hoffa’s leadership first negotiated the National Master Freight Agreement, “binding nearly every large unionized trucking firm in the country to a standard labor contract that covered approximately 450,000 truck drivers.”19 The agreement continues to be negotiated by a multi-employer association to this day, but with many regional

17 https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1228&context=hlelj 18 https://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/basic-page/node-3024/basicguide.pdf 19 https://books.google.com/books?id=ezaXJhJAHAQC&pg=PA208&lpg=PA208&dq=freight+industry+national+master+agreement+1960s+teamsters&source=bl&ots=i_rRnk0eqk&sig=D5PS9vBMbaiJbkeBaGbiuMFIl0Y&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiqqs-Pt5HeAhWCg-AKHQiED64Q6AEwEHoECAEQAQ#v=onepage&q=freight%20industry%20national%20master%20agreement%201960s%20teamsters&f=false

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

10

supplements.20 Regional building trades groups, like the Building Trades Employers Associations in Boston21 and New York22, also negotiate joint agreements with construction unions. While not governed by the NLRA, the rail industry is another site of multi-employer bargaining. “[T]he Railway Labor Act provides for craft based national bargaining, and in the rail sector bargaining occurs with multiple employers and crafts.”23 Pattern Bargaining

“In the American case, pattern bargaining probably represents the closest approximation to the sort of branch or industrial agreements that exist in countries like Germany. For example, the United Automobile Workers (UAW) long has employed the technique in its bargaining with . . . American automobile manufacturers. Used as a means to take wages out of competition, in pattern bargaining, the union concludes an agreement with one of the auto firms, and then uses its key terms as a pattern for the contracts that it will negotiate with the other manufacturers. Consistent with the grass-roots focus of American style collective bargaining, and as part of the bargaining process, local union affiliates of the UAW standardly negotiate supplemental, plant level agreements to regulate local conditions not covered by the master agreement.”24

“The practice took shape in the years after World War II. In the great strike wave of 1946 the big

industrial unions of the CIO all demanded a raise of 18.5 cents an hour. For nearly three decades pattern bargaining allowed union workers to win big wage increases and a growing array of benefits. Workers in auto, steel, rubber, coal, airlines, packinghouses, trucking, oil, telecommunications all won brand-new benefit packages, including pensions and medical insurance. For nearly two decades the wages of workers in auto, steel, rubber, and coal were within a few cents of each other. The real wages of manufacturing workers rose by more than 30 percent from 1950 through 1969. Wages stayed ahead of inflation in most years until the 1970s.

[Soon enough,] patterns were squeezed by international competition, the shift of manufacturing to the South, deregulation, and the spread of non-union rivals. Membership fell, the number of strikes dropped by almost half, new organizing stalled, and the wage gains of the past were considerably trimmed if not outright reversed.”25 The primary critique of pattern bargaining from contemporary labor activists is that rather than fulfilling its purpose of “prevent[ing] a downward slide due to wage competition and . . . creat[ing] a united force to push wages upward,” it has at times “morphed into its opposite—a conduit for concessions and negotiated retreat.”26 20 https://teamster.org/abf-contract-update/2018-2023-tentative-abf-national-master-freight-agreement-regional-supplemental 21 https://www.btea.com/about/ 22 http://www.bteany.com/ 23 http://newlaborforum.cuny.edu/2018/06/22/the-time-has-come-for-sectoral-bargaining/; http://apps.americanbar.org/labor/rwcomm/mw/papers/2003/miller1.pdf http://apps.americanbar.org/labor/rwcomm/mw/papers/2001/moore.pdf 24 https://www.jil.go.jp/english/events/documents/clls06_06usa.pdf 25 http://labornotes.org/2010/02/pattern-retreat-decline-pattern-bargaining 26 Id.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

11

Still, pattern bargaining persists in a variety of industries today. Some notable examples are

discussed below. Municipal Public Sector

“[New York] City has traditionally employed pattern bargaining to simplify the process of negotiating with so many unions. The first union to reach a settlement establishes ‘the pattern’ of wage increases; each subsequent union is expected to agree to the same raises or to a settlement that offsets higher wage increases than the pattern through productivity savings. There are two separate patterns: one for uniformed officers and one for civilian employees. . . . Pattern bargaining preserves parity between the pay scales of ranked officers in the uniformed departments, as well as between departments. It also infuses each round of collective bargaining with order and predictability, and provides assurance to the first union to settle that it will not be ‘leap‐frogged’ by subsequent contracts that achieve more favorable terms. In the past, all union contracts began and ended in the same calendar year, and this period was considered to be a ‘round’ of collective bargaining. In recent years, the end dates of some contracts were extended; as a result, ‘rounds’ of collective bargaining are now denoted less by their ties to the calendar dates and more by the pattern of wage increases that is applied.”27 Musicians

The American Federation of Musicians negotiates its Live Television agreement “with the three major networks—NBC, CBS and ABC.”28 “[T]he agreement serves as the standard for musicians appearing on nationally televised programs. Independent TV producers also sign that agreement. Its benefit, reuse, and new media provisions are modeled for other audiovisual agreements. From the 1960s through the remainder of the 20th century, when unions—including the AFM—were negotiating industry-wide agreements, progressive contract settlements were driven in large part through pattern bargaining. For many years, the AFM’s media agreements contained session wages, per-hour production and air rates, and benefit contributions that were within a few dollars of each other, despite differing schedules for residual payments and re-use patterns. In the 1980s and 1990s, progressive wage, fringe benefit, and workplace standards negotiated by major US orchestras became a model for other orchestral negotiating teams in their efforts for improved contract provisions across the symphonic field. But in the first decades of the 21st century, pattern bargaining slowed as a means of wringing improvements from employers, who sometimes turned the tables and used the pattern process for concessions.”29 Janitors

SEIU’s Justice for Janitors campaign in Los Angeles at the turn of the twenty-first century similarly employed a pattern bargaining model. “The strategy was to organize all the major cleaning companies and have them sign identical contracts [since this] would take labor costs out of competition between area cleaning service contractors.”30 [Auto is another example, see section above]. Tripartite Bargaining 27 https://cbcny.org/sites/default/files/REPORT_7ThingsUnions_05202013.pdf 28 https://internationalmusician.org/pattern-bargaining/ 29 Id. 30 https://escholarship.org/content/qt6ch053x1/qt6ch053x1.pdf

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

12

Early Experiments “[I]n the early years of the Depression, the United States Congress, pressed by President Roosevelt, enacted the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). The cornerstone of Roosevelt’s initial response to widespread poverty, labor unrest, and economic instability, NIRA gave unions, businesses, and consumers shared power to set industry codes, including minimum wages and maximum hours, while simultaneously providing workers the right to organize into unions. NIRA, however, was short-lived. Soon after its enactment, the law became mired in implementation challenges. Then, in 1935, the United States Supreme Court struck down the statute in A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States, concluding that NIRA delegated too much legislative power.”31

“While Schechter Poultry is famous in the constitutional and administrative law canons as a rare exercise of the non-delegation doctrine, it is also widely understood to have ended the nation’s brief, failed experiment with a form of social democratic power-sharing in governance sometimes known as ‘tripartism’ or ‘labor corporatism.’ Tripartism is used in various forms in most industrialized democracies, particularly Europe’s social democracies; it gives worker organizations, business groups, and sometimes consumer organizations as well, a legally defined role in decisions about the direction of the economy generally and social welfare policy in particular.”32 But the conventional account is at least partly wrong: Despite Schechter Poultry, tripartism in the United States was soon temporarily revived by FLSA’s industry committees and persists today in the form isolated use of state level wage boards. FLSA Industry Committees “[T]he original FLSA was more ambitious both procedurally and substantively than the low minimum wages and overtime protections for which it is known today. It created ‘industry committees’ or wage boards composed of tripartite representatives—employers, unions, and the public—with discretion to set minimum wages on an industry-by-industry basis, within a statutorily defined range. Supporters of FLSA saw it as a means to end poverty wages, while extending the reach of unions throughout the nation and throughout the economy. Even more so than the NLRA, FLSA thus instantiated the commitment to empowering worker organizations in the political economy; in fact, many contemporaries saw FLSA as a direct outgrowth of NIRA and tripartite models abroad.”33

“[T]he industry committees were limited in important ways. They had to set minimum wages within a statutorily prescribed dollar range and time period, lacked jurisdiction over working conditions or benefits, and excluded groups of workers, in particular many African Americans in the rural south. Nor did the FLSA boards permanently alter the character of American political economy, since they did not fundamentally change common law rights of employers and employees, or the ownership of resources. Nonetheless, during their existence, the FLSA industry committees represented a high-water mark of broadly inclusive, state-supported collective bargaining.”34 State Wage Boards

31 Kate Andrias, The Forgotten Promise of the FLSA, 128 YALE L.J. (forthcoming 2019). DRAFT 32 Id. 33 Id. 34 Id.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

13

“[A] few states, including California, New Jersey, and New York, [still] vest the power to set wages or other standards with tripartite commissions, i.e., boards with representation from employee groups, industry groups, and the public. . . .

For example, California law provides for an Industrial Welfare Commission (IWC) composed of two union representatives, two employer representatives, and one representative from the general public. The governor appoints each of the five members with the consent of the Senate, and members serve four-year terms. The labor representatives must be drawn from ‘members of recognized labor organizations.’ The IWC’s authority goes beyond creating a basic minimum wage: It has authority to evaluate wages in ‘any occupation, trade, or industry’ to ensure they are adequate ‘to supply the cost of proper living’; it also can consider whether ‘the hours or conditions of labor’ are ‘prejudicial to the health, morals, or welfare of employees.’ If the IWC determines that wages, hours, or working conditions are inadequate, it selects a wage board—again composed of two labor and two employer representatives, along with a neutral party—to investigate and make recommendations. Recommendations that receive the support of two-thirds of the wage board’s members are incorporated into IWC proposed regulations, which are then subject to public hearings. If approved, the orders become part of the California Code of Regulation. Using this process, the IWC has issued seventeen orders: twelve industry orders, three occupation orders, an order that applies to any industry or occupation not previously exempt by the IWC’s wage orders effective as of 1997, and one general minimum wage order.

New Jersey’s tripartite Minimum Wage Advisory Commission (WAC or Commission) is

charged with annually evaluating the state’s minimum wage. As in California, the governor appoints the Commission’s members and is required to choose representatives from business and labor. To that end, New Jersey law incorporates a representative mechanism, specifying that the business representatives ‘shall be nominated by organizations who represent the interests of the business community in this State’ and that the labor representatives ‘shall be nominated by the New Jersey State AFL-CIO.’ Unlike in California, however, the Commission has no representatives from the public; instead, the Commissioner of Labor and Workforce Development fills that function and serves as the Commission’s chair. And WAC does not have authority over benefits or working conditions. The law does, however, allow the Commissioner to establish sectoral wage boards, composed of labor and business representatives, which then recommend minimum wages in particulars sectors. Wage boards can be established if the Commissioner believes ‘that a substantial number of employees in any occupation or occupations are receiving less than a fair wage.’ The law also provides for a public hearing process after which the Commissioner decides whether to approve or reject the report.

To date, the experience with state-level tripartite commissions has been mixed. Some wage

boards, including Colorado’s, appear to have been moribund for years. In other states, like California and New York, wage boards have been used successfully at times. However, no commission is actively or aggressively setting employment standards today. Indeed, the California IWC has been without funding since 2004. The California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement continues to enforce the existing wage orders, and the legislature has not repealed the IWC’s statutory responsibilities, but the current status of the IWC can be characterized as an unfunded legislative mandate. In New York, the Fight for $15 movement recently used the state wage board with success. In 2015, after growing protests and strikes organized by the Fight for $15, and at the request of Governor Andrew Cuomo, the NY labor

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

14

commissioner exercised his authority to impanel a wage board to recommend higher wages in the fast food industry.

The Board Members—representatives from labor, business, and the general public—held hearings over the next forty-five days, across the state. Workers organized by the Fight for $15 participated in great numbers at these hearings. On July 21, the Board announced its decision: $15 per hour for fast food restaurants that are part of chains with at least thirty outlets, to be phased in over the course of six years, with a faster phase-in for New York City. The wage board order was a significant victory, followed by another victory: a bill to raise the state-wide minimum wage to $15. However, in the negotiations over the state-wide minimum, employers successfully mobilized to strip the Commissioner’s authority to establish higher minimums for particular occupations. Thus, the ultimate compromise bill curtailed the powers of future tripartite wage boards. Still, the New York experience shows how tripartite structures can be used to engage workers in setting terms of work for entire industries.

The New York example aside, where wage boards have operated, the potential for social

bargaining has often been under-realized. Unions have not frequently engaged the commissions through wide spread mobilization, testimony, and collective action. The boards, as currently conceived, also have structural limitations. The ability of workers to use wage boards to their benefit largely depends on the identity of the governor in the state; he or she influences when such boards act and who constitutes them. Thus, in California, for example, former Governor Schwarzenegger tried to use the wage board to limit the legislature’s proposal to index the minimum wage. Moreover, in most cases, the neutral representatives on the commissions effectively decide disagreements. These individuals, selected by the partisan governors, serve as the swing votes and thereby minimize the extent to which true bargaining occurs. This weakness is pronounced when there is no broader worker mobilization exerting pressure on the commissions.

Nonetheless, more could be done to use existing wage boards aggressively, as was done by the Fight for $15 in New York. In jurisdictions where worker organizations have significant political influence, and where the executive branch is amenable, workers can petition wage boards to act. Where statutes permit, they can demand sector-by-sector wage and benefit improvements, beyond minimum wage increases. They can also engage workers in collective action designed to achieve such gains, as the Fight for $15 did in New York.”35 While the United States has been home to some historical moments and specific industries experimenting with sectoral-like bargaining models, firm-level bargaining remains the American default where collective bargaining takes place at all. The next section explores the experiences of countries where sectoral bargaining and its close counterparts have played a larger role in setting the terms and conditions of work.

35 Kate Andrias, Social Bargaining in States and Cities: Toward a More Egalitarian and Democratic Workplace Law (Harvard Law School Symposium Paper), http://harvardlpr.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Andrias-Social.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

15

4. Supply Chain Bargaining

Another route to explore is supply chain bargaining. This might involve requiring apex companies to bargain regarding all of the terms and conditions of their contractors and other companies in their supply chain, or requiring all companies in a supply chain to engage in multi-employer bargaining. The need for such an approach is growing: “Work that was once done in-house is increasingly scattered across multiple employers interconnected by a chain or network of contracts. This disintegration has several causes, including employers’ drive to escape or prevent unionism and to avoid legal responsibility for employment standards. And it has many baleful consequences, including the swelling of the precarious, low-wage labor market. Not coincidentally, low-wage workers shoulder much of current efforts to organize across multiple employers.”36

Types of Contractual Interconnection

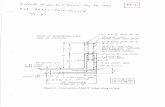

Mark Barenberg has sketched the following kinds of interconnections among employers: “First is the supply chain. Imagine, for example, a single washing-machine manufacturer and distributor that once housed (1) factories producing the primary parts for washing machines, such as ignitions for washing-machine motors, (2) factories assembling secondary components for washing machines, such as washing-machine motors, (3) factories assembling the secondary components into washing machines, (4) warehouses and trucks for storing and transporting parts and assembled products, and (5) retail dealerships selling the washing machines. Suppose the corporation then spins off stages (1), (2), (4), and (5) into independent corporations, but continues to own and operate the final assembly stage, and suppose the five separate corporations are linked by exclusive supplier-purchaser contracts. (See Figure 2.) The five corporations would constitute five links in a single supply chain. [Other supply chains are labor- or service-only supply chains].

In the second and more common pattern of interconnectedness, a single supply chain interweaves with others to form a production-and-distribution network. For example, some of the goods sold by Walmart, Target, and Kmart may be produced in the same factories, transported by some of the same shipping companies to some of the same ports, unloaded by some of the same stevedoring companies, transported by some of the same trucking companies, stored in some of the same warehouses, and transported again by some of the same trucking companies to the Walmart, Target, and Kmart stores. All of these companies are nodes in the network pattern.

A third pattern is a hub-and-spoke wheel of contracts. A building owner, for example, is the hub, and enters into contracts with cleaning companies, security companies, landscapers, insurers, tenants, and others.

A pyramid is a fourth pattern. A fast-food company, for example, stands at the pinnacle of a hierarchy and franchises the many small restaurants at the bottom.

36 Mark Barenberg, Widening the Scope of Worker Organizing: Legal Reforms To Facilitate Multi-Employer Organizing, Bargaining, and Striking, ROOSEVELT INST. 3 (Oct. 1 2015, http://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Widening-the-Scope-of-Worker-Organizing.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

16

A fifth pattern exhibits no contractual interconnection among corporations but is simply a horizontal group of independent businesses in a given sector—for example, a retail sector made up of small, separately owned stores.”37

Redefining Employer and Employee

One way to facilitate bargaining along a supply chain would be to redefine terms like “employer” and “employee” to ensure that workers are protected under labor law and that all firms along a supply chain could be classified as employers.

Employer = Indirect Control and Reserved Control

“In 2015, the Obama Board issued its decision in Browning-Ferris Industries, a re-articulation of the Board’s standard for when companies can be held responsible for labor violations by other companies. The Board held that common law principles supported considering two or more entities to be joint employers based not only the exercise of actual control over workers’ terms and conditions of employment, but also indirect control or reserved authority. . . . [I]n December 2017, the Trump Board majority issued its decision in Hy-Brand, reversing Browning-Ferris and returning the Board to a standard that required proof that an employer exercised direct and immediate control in a manner that it is not limited or routine.”38

While Hy-Brand was soon vacated because of ethics issues, the Board is now engaging in rule-making that will presumably adopt its standard.

While considering an employer’s reserved authority or a company’s indirect control over the terms and conditions of work, the BFI standard does not go far enough in allowing bargaining along more than one level of a supply chain; many employers may not have reserved authority to control workers or indirectly control those farther along the chain.

Employer = Sufficient Bargaining Power

Mark Barenberg has offered the following tentative proposal: “An entity would be deemed an employer of multiple workforces if it has ‘sufficient bargaining power’ to determine the terms and conditions of all the employees in question, even if the entity is not currently exercising such power. By organizing and bargaining with that single entity, a worker organization would effectively organize and bargain with what is currently deemed a multi-employer association.

Legal reform could authorize worker organizations to unilaterally choose the scope of bargaining units, including multi-employer units. And, if the Board is called upon to select among differing units chosen by different worker organizations, the Board should define units based on the criterion of ‘maximum potential worker empowerment.’”39

37 Id. at 3, 7. 38 Sharon Block, Joint Employer NPRM: Hy-Brand Returns, ONLABOR (Sept. 17, 2018), https://onlabor.org/joint-employer-nprm-hy-brand-returns. 39 Barenberg, at 14–15.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

17

Employee = Presumed unless ABC

Under the ABC test adopted by the California Supreme Court in Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court of Los Angeles, a worker will be deemed to have been “suffered or permitted to work,” and thus, an employee for wage order purposes, unless the putative employer proves: (A) that the worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact; (B) that the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and (C) that the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed.40

Secondary/Neutral Employers

Beyond redefining the employment relationship, there are other ways in which labor law can adapt to hold firms accountable across a supply chain. Below are examples from the NLRA, the FLSA, and proposed laws.

Client Employers Under California Labor Code 2810.3

“Assembly Bill 1897 created section 2810.3 of the California Labor Code to hold businesses liable for wage theft and inadequate workers’ compensation coverage when they use staffing agencies or labor contractors to obtain workers. Under the prior law, a business could be held responsible for unfair labor practices only if the worker could prove joint employer status. Consequently, many businesses were shielded from accountability when workers were denied wages or were injured from working in substandard conditions. Workers who attempted to report the unlawful labor practices were often retaliated against by the employer without any recourse. Since businesses have increasingly exploited third-party labor suppliers to acquire low-cost, temporary workers for strenuous and dangerous jobs, without being subject to the Labor Code’s provisions governing workers’ rights, California passed AB 1897 to distribute liability between the employer and the labor contractor. As a result of this legislation, vulnerable temporary workers are protected from “adverse action” from both the employer and the labor contractor for whistleblowing and can file a civil action against an employer for any wage and workers’ compensation violations. Notably, no finding of “employer” status of the lead or client company is required.”

According to one commentator, “All California businesses with 25 or more employees that use at least 6 temporary workers, provided by a labor contractor, to perform labor within their ‘usual course of business’ must now share ‘all civil legal responsibility and civil liability’ for subcontracted workers with the labor contractor.”41

40 “ABC” laws creating a presumption of employment status have been on the books in over half of the states’ unemployment insurance laws for decades; more recently, several states have added the test to wage theft and other workplace laws. See, National Employment Law Project, Independent Contractor v. Employee (2016) https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Brief-Independent-Contractor-vs-Employee.pdf. 41 https://www.stevenrubinlaw.com/2017/07/04/protecting-subcontracted-workers-through-ab-1897/

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

18

FLSA Hot Goods Provision

“Under the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), workers must earn a minimum wage and be paid premium compensation for all overtime work. The FLSA imposes these obligations on ‘[e]very employer’ as to ‘his employees.’ But it also contains a provision known as the ‘hot goods’ clause that extends the duties to production employees along the chain of distribution of their products. The clause makes it unlawful to transport or sell ‘goods in the production of which any employee was employed in violation’ of the FLSA.

Under the hot goods provision, liability is not located in or limited to the employer of the employees but rather literally runs with the goods produced in violation of the law. The provision might be thought of as the mirror image of product liability law, with the trajectory of liability reversed. Under product liability law, courts extend responsibility for defective products back from the ultimate consumer to the producer, departing from the limiting principle that the parties in a warranty action must be in privity of contract. Under the hot goods provision, liability is extended forward from the producer toward the ultimate consumer.

The extension of liability through the hot goods provision to those who trade in goods produced in violation of the FLSA may be justified in four ways. First, it might be argued that although it is contractors who directly violate the law, their clients ultimately cause or procure the violations by promoting continuous competition among contractors who in labor-intensive industries--such as building services--can cut costs only by reducing wages already hovering at or near the minimum. Second, whether procuring the violations or not, clients benefit from them through the lower price the contractor can charge because of the violations.

Third, the advantages gained by clients from the violations allow a form of unfair competition. President Franklin D. Roosevelt underscored this point in the Message to Congress that inspired the FLSA's passage: ‘Goods produced under conditions which do not meet rudimentary standards of decency should be regarded as contraband and ought not be allowed to pollute the channels of interstate trade.’ The Supreme Court has expressly recognized the principle of unfair competition, holding that Congress intended the FLSA to ‘eliminate the competitive advantage enjoyed by goods produced under substandard conditions.’ Competitors are injured when goods produced in violation of the Act are sold whether the workers who were underpaid are hired by the seller or by some upstream producer.

Finally, by placing responsibility on client companies, the hot goods provision affords parties with unique access to information about contractors’ labor relations and with considerable economic authority over contractors an incentive to ensure that contractors comply with the law. When a client company’s goods are seized, it releases its goods by paying the workers directly, and then it can go after its subcontractors for the money. In this way, companies are incentivized to contract with above-board, capitalized subcontractors.

The FLSA gives the Secretary of Labor authority to enforce its terms and vests in employees a private right of action to remedy violations (though not for hot goods). But the Secretary cannot effectively police hundreds of thousands of workplaces, particularly those that have no fixed location

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

19

and suddenly appear and disappear. Employees may risk more by bringing an action than they can reasonably expect to gain despite the FLSA’s ban on retaliation, and too often have trouble enticing lawyers to bring their claims in court if the dollar amounts are relatively low and class or collective action is not possible. From an enforcement perspective, client companies have both the advantages of employees in having a direct economic link to the employers and the advantages of government in being relatively insulated from retaliatory action.”42

Related to government seizure of goods produced in substandard conditions, many states also permit stop-work orders (SWO’s) in worksites where labor and employment laws are not followed.43 Typically used to ensure workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance coverage on construction sites, SWO’s can bring work in subcontracted workplaces, like hotels, construction sites and hospitals, to a standstill until the violation(s) are remedied.

Duty of Reasonable Care

In the context of FLSA, Brishen Rogers has argued that strengthening joint employer liability is an ineffective means of ensuring wage-and-hour compliance across the supply chain.44 He instead proposes a legal regime that would hold firms to a duty of reasonable care to prevent violations of wage-and-hour laws within their supply chains (one suggestion is to give employees a private right of action to enforce the hot goods provision). While not wholly relevant to multi-employer bargaining, one idea of how this might be employed in the labor law context is to hold firms to a duty of reasonable care to prevent unfair labor practices within their supply chains.

NLRA Construction and Garment Industry Provisos

“The National Labor Relations Act includes a general policy against secondary union activity-union pressure exerted against a neutral employer in order to influence the labor relations of another employer. In 1947 the Taft-Hartley Act outlawed strikes and boycotts for secondary objectives, but a loophole in the Act rendered agreements aimed at secondary objectives immune from scrutiny under the labor laws. These agreements are known as "hot-cargo" contracts, a term that arose from their original use by the Teamsters Union. In response to widespread dissatisfaction with the labor laws' tolerance of secondary agreements, Congress amended the Act in 1959 by adding section 8(e), which curtails the freedom of unions and employers to make hot-cargo agreements. The amended Act does not absolutely prohibit all secondary agreements, however. A proviso to section 8(e) gives a limited exception for subcontracting agreements between a union and an employer in the construction industry; a second proviso creates a more generous exception for the garment industry. The construction industry proviso

42 Craig Becker, Labor Law Outside the Employment Relationship, 74 TEXAS L. REV. 1527 (1996).

43 For example, in 2012, Massachusetts’ Department of Industrial Accidents issued 15 stop work orders for lack of workers’ compensation coverage. Massachusetts Department of Labor, Joint Task Force on the Underground Economy and Employee Misclassification 2012 Annual Report (August 2013), available athttp://www.mass.gov/lwd/eolwd/jtf/annual-report-2012.pdf. See also, https://www.ctdol.state.ct.us/communic/newsrels-Archives/2011-8/8-17-11Stopders.pdf

44 Brishen Rogers, Toward Third-Party Liability for Wage Theft, 31 BERKELEY J. EMPL. & LAB. L. 1, 12–15 (2010)

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

20

allows a union to agree with an employer in the construction industry to restrict subcontracting at the job site to firms employing union workers. These agreements are secondary because they use the general contractor to pressure the subcontractors to recognize the union as the representative of the subcontractor's employees.”45

Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW)

The CIW provides an inspiration model for supply chain bargaining, though it is important to note that, in order to achieve its victories, the organization has employed strategies of secondary activity that would be prohibited by the NLRB.

“ . . . CIW had identified the twin evils of modern day supply chains as, (1) the ability of the megacorporations at the top to demand ever-lower prices from their suppliers and the concomitant inexorable downward pressure which that placed on growers’ profits, workers’ wages, and the overall workplace environment, and (2) the lack of any requirement or desire on the part of those same corporations to put their purchasing power behind their professed desire for a responsible supply system. Having thus identified the purchasing power of corporations as the root of the evil, CIW envisioned a world in which that same power, if corporations were properly motivated, could also be the solution. Consequently, each corporation in the [Fair Food Program (FFP)], as a condition of participation, has signed a legally binding contract, called a Fair Food Agreement (“FFA”), with CIW. These contracts, which represent the first indispensable element of the FFP, have evolved over time to cover topics such as marketing, expansion, and support for the Program’s monitoring function, but each contains two fundamental provisions.

First, each corporation pays a Fair Food Premium on every pound of covered produce that it purchases from participating growers. The amount of the premium varies depending on the type of produce purchased, but it is always paid by the corporation to the grower within the corporation’s existing purchasing system. This means that some corporations pay the premium directly to the grower, while others pass it down through one or more middlemen. But once the premium reaches the grower, it must be passed on to the farm’s qualifying workers as a Fair Food bonus. Functionally, the premium helps address the historic poverty of farmworkers, exacerbated now by the downward pressure on wages caused by the corporations’ massive purchasing power. Conceptually, it represents a small step in addressing the cost/price squeeze faced by growers in the increasingly monopsonistic system that is today’s retail food market.

The other requirement of every FFA is that the corporation only purchase covered produce from participating growers who are in good standing with the Program, as determined by the FFSC, the Program’s monitoring organization. . . . [I]f a grower is suspended from the Program for failure to abide by the Fair Food Code of Conduct, participating buyers cannot purchase from that grower until it gains reinstatement. This binding provision is the sine qua non of compliance. Without it corporations could, and therefore would, walk away when confronted with a significant disruption to their existing supply

45 Michael Dreeben, Hot-Cargo Agreements in the Construction Industry: Restraints on Subcontracting under the Proviso to Section 8(e), 1 DUKE L.J. 141–42 (1981), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2766&context=dlj.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

21

chains. The fundamental social change created by the FFP is not free, and is not always easy. Only the real threat of losing sales provides the necessary motivation for growers to make the sometimes-difficult choices involved in modernizing their labor practices.”46

Bangladesh Accord

“The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (the Accord) was signed on May 15th 2013. It is a five year independent, legally binding agreement between global brands and retailers and trade unions designed to build a safe and healthy Bangladeshi Ready Made Garment (RMG) Industry. The agreement was created in the immediate aftermath of the Rana Plaza building collapse that led to the death of more than 1100 people and injured more than 2000. In June 2013, an implementation plan was agreed [upon] leading to the incorporation of the Bangladesh Accord Foundation in the Netherlands in October 2013.

The agreement consists of six key components: 1. A five year legally binding agreement between brands and trade unions to ensure a safe working

environment in the Bangladeshi RMG industry 2. An independent inspection program supported by brands in which workers and trade unions are

involved 3. Public disclosure of all factories, inspection reports and corrective action plans (CAP) 4. A commitment by signatory brands to ensure sufficient funds are available for remediation and to

maintain sourcing relationships 5. Democratically elected health and safety committees in all factories to identify and act on health

and safety risks 6. Worker empowerment through an extensive training program, complaints mechanism and right to

refuse unsafe work.”47

46 Greg Asbed & Steve Hitov, Preventing Forced Labor in Corporate Supply Chains: The Fair Food Program and Worker-Driven Social Responsibility, 52 WAKE FOREST L. REV. (2017), http://ciw-online.org/wp-content/uploads/HitovAsbedArticle_AuthorCopy.pdf; see also James Brudney, Decent Labour Standards in Corporate Supply Chains: The Immokalee Workers Model, in TEMPORARY LABOUR MIGRATION IN THE GLOBAL ERA 351 (Joanna Owens & Rosemary Howe eds., 2016), https://wsr-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/CIW-and-Decent-Labour-Standards_18May2016.pdf. 47 http://bangladeshaccord.org/governance/

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

22

5. Synthesis of International Sectoral Bargaining Models MULTI-EMPLOYER BARGAINING AND CONTRACT EXTENSION “Coverage and extension are key components of national industrial relations institutions in general and bargaining systems in particular. First, there is almost by definition a close association between coverage and extension. As comparative analysis has found . . ., the extent to which extension mechanisms are used in a country is the most powerful single determinant of variations in the level of bargaining coverage across countries: coverage tends to increase significantly with the use of extension practices. Conversely, the applicability and actual use of extension mechanisms depends decisively on the nature of the bargaining system. For obvious reasons, extension rules can be implemented effectively only in connection with multi-employer collective agreements.”[1] Types of Extension Erga omnes Based on the “erga omnes” (“towards everyone”) principle, this type of extension “makes a collective agreement generally binding within its field of application by explicitly binding all those employees and employers which are not members of the parties to the agreement.”[2] Types of Erga Omnes Extension Semi-automatic: “The semi-automatic extension regime does not require a public authority to make a decision having heard representation from those likely to be affected by the decision. As long as the collective agreement is valid – and this may require a particular representivity threshold being met (e.g. Finland) – the collective agreement will be deemed to be generally applicable in its domain (France, Spain, Iceland, Finland, Greece under the national general labour agreements until 2010; and Romania until 2011). . . . Another feature of the semi-automatic regime is that it often allows the Minister to take the initiative rather than wait for the request from the negotiating parties (e.g. in France).”[3] Examples of representivity thresholds: o Finland: “The [collective agreement] must be nationwide and representative for the sector concerned (>50% employees covered).”[4] o France: “No representativeness criteria for employers. [Trade unions] need to have received >30% of votes at the last professional elections and the agreement should not be opposed by any [trade union] having received >50% votes.”[5] Supportive: “The supportive extension regime operates within the boundaries of procedural law with rules and criteria for extension. With very few exceptions, Ministers or public authorities can only extend collective agreements, and only those provisions in such agreements, for which extension has been requested by the signatory unions and employers’ associations. . . . The procedure tends to be more demanding when extension must be filed jointly, as in Germany and Switzerland. The collective agreement must cover a ‘sufficiently representative’ proportion of employees before it can be extended. The count is usually based on the representation of the employers’ association, measured by the number

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

23

of workers employed by their member firms. But there may be additional criteria (such as a minimum number of firms represented, SME representation, union density, etc). In recent years, it has become common practice to give the Minister, or deciding authority, some discretion allowing extension where it is crucial for the survival of training and social funds linked to a collective bargaining council, where there is a high proportion of vulnerable workers (e.g. migrant or contract workers) in a sector, or where representivity criteria cannot be met by virtue of a high proportion of non-standard workers in a sector. These public interest considerations have become more important in recent years with the growing diversity of firms and work arrangements. As a rule, extension decisions are taken only after the firms and workers (or their representing ‘minority organizations’) to whom the agreement is extended are given the opportunity to submit their ‘observations” or “objections.’ The Minister or public authority may also be authorized to grant exemptions to certain firms from the extension order, on application. By 2015 the supportive extension regime applied in ten countries: Croatia, Slovenia (and probably also the other former Yugoslav republics), Germany, Switzerland, South Africa, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Israel, Portugal and Belgium.”[6]

Restrictive: “The restrictive extension regime is different in the use of the criteria that apply in the supportive regime. Representivity criteria are more demanding than is the case in the supportive regime, and are frequently set at higher levels (requiring supermajorities, for example). A further restriction may be that extension may only be applied in sectors with foreign workers and there is the threat or reality of social dumping (e.g. Norway).”[7] Enlargement Through enlargement, “a collective agreement is extended to a specific geographic or sectoral area outside its actual scope.”[8] o “in Austria, enlargement takes the form of an 'extension order', issued by the Federal Arbitration Board (Bundeseinigungsamt). The board acts upon written requests from employers' or employees' organisations. Collective agreements to be extended in this way must be of 'prevailing importance', the working conditions in the 'adopting' sector must be similar to those in the sector where the collective agreement originates and there must not be a competing agreement; o in Portugal, enlargement procedures apply in cases where there are no bargaining partners in a given sector or where the parties do not show any initiative to negotiate a collective agreement. Enlargement is granted in the form of an extension directive (Portaria de extensão) by the Minister of Labour. Although employers, their associations, and trade unions have the opportunity to object to this decision, they do not have the power to stop enlargement of an agreement; and o in Spain, enlargement is granted only where workers and employers are prejudiced by their inability to enter into a collective agreement in their field, due to the absence of legitimate bargaining parties. In addition, the law requires a positive decision by the joint National Consultative Committee on Collective Agreements (Comisión Consultiva Nacional de Convenios Colectivos) which also needs to be approved by the Ministry of Labour. Applications for enlargement are to be filed by one or both parties to a collective agreement.”[9]

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

24

Functional equivalents of extension Even where extension is rare or not possible by law, other practices can achieve roughly the same effect as extension. In Austria, “[e]xtensions are rarely issued. Compulsory membership to an [employer organization] for all firms works as a functional equivalent keeping [collective agreement] coverage high.”[10] In Italy, “[t]here are no formal extension mechanisms but the Constitutional obligation to pay a ‘fair wage’ is a functional equivalent because judicial practice refers to the reference [collective agreement] to determine what is the level of a “fair wage.”[11] MULTI-EMPLOYER BARGAINING WITHOUT CONTRACT EXTENSION

“The Swedish tradition of self-regulation is based on voluntary collective agreements, not agreements forced through law. In addition, Sweden has no legislation on the extension of collective agreements to whole industries. The only way to force employers to enter collective agreements is through collective action.”[12]

WAGE BOARDS

“The foundations for labour relations in Uruguay were developed in 1943 through Law 10,449, which created the wage councils. The wage councils were charged with negotiating minimum wages in each economic sector and category; their structure was tripartite, involving three representatives of the executive branch of government, two workers’ representatives, and two employers’ representatives, with their respective alternates.”[13]

[NB: We need to explore mechanisms for national and sectoral bargaining internationally].

[1] Franz Traxler & Martin Behrens, Collective Bargaining Coverage and Extension Procedures, EurWORK (Dec. 17, 2002), http://www.eurofound.europa.eu /observatories/eurwork/comparative-information/collective-bargaining-coverage-and-extension-procedures [http://perma.cc/2PWM-4HHP]. [2] Id. [3] Susan Hayter & Jelle Visser, The application and extension of collective agreements: Enhancing the inclusiveness of labor protection, International Labour Organization (2018), https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_633672.pdf. [4] Employment Outlook 2017, Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work: Online Annex Chapter 4, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/EMO2017-CH4-Web-Annex.pdf. [5] Id. [6] Hayter & Visser, The application and extension of collective agreements. [7] Id. [8] Traxler & Behrens, Collective Bargaining Coverage and Extension Procedures. [NB: need to clarify how this is different from erga omnes.] [9] Id. [10] Employment Outlook 2017, Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work: Online Annex Chapter 4.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

25

[11] Id. [12] Anders Kjellberg, Self-regulation versus State Regulation in Swedish Industrial Relations, Juristförlaget i Lund (2017), https://web.archive.org/web/20171009181150/http://portal.research.lu.se/ws/files/23904978/Kjellberg_FSNumhauserHenning_Self_Regulation_State_Regulation.pdf. [13] Graciela Mazzuchi, Labour relations in Uruguay, 2005-2008, International Labour Office (Nov. 2009), https://www.ilo.org/legacy/english/inwork/cb-policy-guide/uruguaylabourrelations2005to2008.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

26

Internal Variations (by chart)

1. Ultra-activity and duration of CAs48

● Ultra-activity refers to the validity of an agreement after its termination date. ● Social partners refers to representatives of employers and workers, usually employer

organisations and trade unions.

Allows ultra-activity of CAs

Does law set a maximum duration of ultra-activity?

Average duration of CAs (months)

Is there a maximum legal duration of CAs?

Australia No rule, unlimited 36 At the firm level: 48 months

Austria No rule 12 No (though in practice, wage agreements are negotiated every year)

Belgium No, but can be set by social partners

24 No

Canada No rule 43 No

France For permanent agreements, if notice is given, 15 months of ultra-activity and possibility to prolong them. For fixed-term, no limit to ultra-

- No (usually there is no end date, but in the rare cases where there is an end date, maximum five years).

48 Information from EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK 2017, COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN A CHANGING WORLD OF WORK: ONLINE ANNEX CHAPTER 4, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/EMO2017-CH4-Web-Annex.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

27

activity.

Germany No rule - At the firm and sectoral level: if agreed to by social partners.

Norway No rule 24 Yes, by law 36 months, but the SP are free to agree on other terms of duration, usually 24 months (at firm and sectoral levels).

Portugal Yes, 12 months 43 No

Spain Yes, 12 months (social partners can deviate)

12 Yes (agreed by social partners at firm and sectoral level).

Sweden No rule 36 It is left to social partners (most have a termination date, some are indefinite). Manufacturing: 36 months.

No ultra-activity

United States - - Agreed to by social partners at firm level

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

28

United Kingdom - - No

2. Derogations from CAs49

● Derogation refers to opening or derogation clauses which allow for lower standards, i.e. less favourable conditions for workers, in a generalised way and not specifically related to economic difficulties.

● Opt-out clauses refers to temporary “inability to pay” clauses that allow the suspension or renegotiation of (part of) the agreement in cases of economic hardship.

Derogations from CAs allowed

Scope Topics

Austria General opening clauses are possible in sector level agreements.

Wages and working time.

Belgium General opening clauses and temporary opt-out are possible in sector-level agreements. They are exceptional.

Wages.

France* General opening clauses and opt-out are granted by the law and/or possible in sector-level agreements.

General opening clauses allow derogate on working time. Opt-out on wages and working time.

Germany General opening clauses and opt-out are possible in sector-

Mainly wages, working time and temporary agency work. The collective bargaining

49 Information from EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK 2017, COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN A CHANGING WORLD OF WORK: ONLINE ANNEX CHAPTER 4, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/EMO2017-CH4-Web-Annex.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

29

level agreements. parties may also allow derogations in other topics.

Portugal Opt-out clauses are granted by law.

Wages and working time.

Spain General opening clauses and temporary opt-out are granted by the law.

Wage and working time.

No derogation permitted

Australia - -

Norway - -

Sweden - -

*See France profile for summary of recent legislative changes on this front.

3. Enforcement of sector-level CAs50

● Peace clauses, otherwise known as no-strike agreements, prohibit signatory unions and their members from lawfully striking on issues regulated in the agreement

Sector-level CAs typically include a mediation/arbitration procedure

Is it compulsory?*

Do agreements typically include a peace clause?

Austria Yes No

50 Information from EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK 2017, COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN A CHANGING WORLD OF WORK: ONLINE ANNEX CHAPTER 4, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/EMO2017-CH4-Web-Annex.pdf.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

30

Belgium Yes No

Spain Yes Yes

Sweden Yes Yes

Sector-level CAs typically do not include a mediation/arbitration procedure

France (but CAs are permitted to include them)

- No

Germany - Yes

Norway - Yes

Portugal - No (but some agreements do)

*Note that in the OECD, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, the Netherlands, Slovenia, and Switzerland, sector-level CAs typically include non-compulsory mediation/arbitration procedures.

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

31

4. Board-level employee representation in private-sector companies51

Has board-level employee representation in private sector

Size requirements for representation (# of employees)

Proportion of worker reps

Nomination and appointment process

Austria >300 1/3 of supervisory board Appointed by works council

France Compulsory >1,000 in France or >5,000 worldwide

Minimum one rep for boards of 12 or fewer, minimum two reps for boards more than 12

Shareholders choose if reps will be (1) nominated by union and elected by employees, (2) appointed by works council, or (3) appointed by union.

Germany <500 500-2,000: min. 1/3 supervisory board >2,000: 1/2 of supervisory board (note: shareholders elect chair, who has a tie-breaking vote)52

500-2,000: appointed by WC/employees, elected by employees >2,000: appointed by employees/execs/union, elected by employees or delegates

51 Information from EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK 2017, COLLECTIVE BARGAINING IN A CHANGING WORLD OF WORK: ONLINE ANNEX CHAPTER 4, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/EMO2017-CH4-Web-Annex.pdf. 52 European Trade Union Institute, Board-level Representation - Germany, Worker-Participation.eu, http://www.worker-participation.eu/index.php/National-Industrial-Relations/Countries/Germany/Board-level-Representation (last visited Nov. 11, 2018).

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

32

>1,000 in iron/coal/steel industry: 1/2 of supervisory board + de facto one member of management board

>1,000 in iron/coal/steel industry: appointed by WC or union, elected by shareholders

Norway >30 with request by majority of employees

Minimum one member up to 1/3 of board + one, based on company size

Appointed by union.

Sweden >25 and decision from local union bound by CA

<1000 employees: 2 members >1000 employees & operating in several industries: 3 members Max 1/2 of board.

Appointment by local unions bound by CA

Does not have board-level employee representation in private sector

Australia

Belgium

Canada

Portugal

Spain

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

33

United States

United Kingdom

Research Draft prepared for Clean Slate Project - Not for Circulation, Citation, or Attribution

34

6. Case Study: Mechanics of Sectoral Bargaining in Norway and South Africa

Norway:

Depending on how you look at it, bargaining in Norway is conducted at either 2 or 3 levels.53 Basic agreements: Every few years, union confederations and employer associations negotiate