J. Yogev and Sh. Yona, "Epigraphic notes on KTU 6.1", Ugarit Forschungen 45, 2014.

Lebo-Hamath, êūbat-Hamath and the Northern Boundary of the Land of Canaan, Ugarit-Forschungen 31...

Transcript of Lebo-Hamath, êūbat-Hamath and the Northern Boundary of the Land of Canaan, Ugarit-Forschungen 31...

vi In halt [UF 31

A. HAUSLEITER/A. REICHE, Iron Age Pottery in Northern Mesopotamia, Northen~ Syna and Sowh-Eastem Anatolia. Papers presented at the m~etmgs of the international "table ronde" at Heidelberg ( 1 995) and Ntebor6w (1997) and other contributions (W. Zwickel) .. ... . .. .

S. LAFONT, Femmes, Droit et Justice dans I'Antiquire orientale (0. Loretz) . G. del 0LMO LETE I 1. SANMARTIN, Diccionario de Ia lengua ugarftica

Vol. 1-11 (0. Loretz) ... . . . A. SCHOL~, D~e Syntax der althebr~fs~i~~,; i~~~~/;,:,j,~11•• '£;,; JJeft;·~~ . ..... .

zur l11stonschen Grammatik des Hebriiischen (0. Loretz) ......... . G. TIIEUER, Der Mondgott in den Religionen Syrien-Paliistinas. Unter

besonderer Beriicksichtigung von KTU 1.24 (0. Lorctz) .. . ... . . .. . 1. TROPPER, Ugaritische Grammatik (0. Loretz) . . . . . .... . ... ... ... .

906 907

908

909

909 9 12

Iodizes (bearbcitet von Th.E. Balke) ................... . . ... . 9 13 A. Stcllen B. Worter C. Namen D. Sachcn

...... . .............. .. ... . .......... . .. 9 13 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 16 ..... .. .. . ......... .. ......... . ........... 9 19 • 0 •••••• 0 •• 0 ••• • ••• ' ••• 0 •• ••• • • • • • ••• • •••• 922

Abkiirzungsverzeichnis .... . . . .......... . . . ..... . .... . 925

Anschriften der Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter .. . ........ . ... 935

,

Lebo-IIamath, ~ubat-Hamath, and the Northern Boundary of the Land of Canaan

Nadav Na'aman, Tel Aviv

1. Lebo-hamath in Biblical Bor-der- Delineations Lcbo-hamath is mentioned eleven times in the Bible. 1 Once it appears as

a place on the northern boundary of "the Land of Canaan in its full extent"(Num 34:8), and twice as a town on the northern boundary of Ezekiel's future Land of Israel (Ezck 47:20; 48: 1). In all other descriptions it appears as a northernmost border point in the juxtaposition "from ... unto ... " .

Among the la tter group of references, Lcbo-hamath is mentioned in a Priestly insertion in the story of the spies (Num 13,21), as marking the northern limit of the Land of Canaan 2

. It is mentioned twice in descriptions of the "remaining land" (Josh 13:5; Judg 3:3), and three times as the northernmost limit of David's and Solomon's kingdoms (1 Kgs 8:65; 1 Chr 13:5; 2 Chr 7:8). Once it designates the northern ex tent of Jeroboam Il 's conquests (2 Kgs 14:25), in juxtaposition with the Sea of the Arabah, the southern border of the Kingdom of Israel.

Finally, in a prophecy of Amos (6 :14), Lcbo-hamath and the Brook of the Arabah are named in a vision of a future reversal of Israel's fortune: it will be oppressed in all the territories that now it dominates.

Most of the eleven references of Lcbo-hamath arc late, either exilic (Josh 13:5; Judg 3:3 3

; Ezek 47:20; 48:1), or late post-ex ilic (1 Chr 13:5; 2 Chr 7:8). Numbers 13:21 and 34:8 are part of the Priestly composition, which is usually dated to the early post-ex ilic period. However, some scholars date the P source to the pre-exilic period 4

•

Lcbo-harnath is a place name and should not be translated "the entrance of Hamath", or "the Hamath corridor" (NORTH 1970/71 :97- 10 I). For discussion, sec ELLIGER 193-6:42-45; WEIPPERT 1992:59 n. 100, with earlier literature. 2 MT mentions "utllo Rchob of Lcbo-hamath". Rchob is most probably the name of a kingdom located in the southern Bcqii' of Lebanon. I therefore suggest that the author of the text mentioned two toponyms located in the same direction, the second being more remote than the first. r or biblical parallels, sec Josh 10: I 0; 16:3; I Sam 17:52; Nch 3: 16, 24, 3 1. For discussion and earlier literature, sec NA'AMAN 1992:287-288. Num 13:2 1 may be translated thus: "So they went up and spied out the land from the wilderness of Zin unto Rehob (and unto) Lebo-hamath".

The descriptions of the "remaining land" (Josh 13:2-6; Judg 3: l, 3) are postDcuteronomistic. Sec SM END 197 1 :497-500; 1983. 4 For the debate on the date of the Priestly source, sec recently BLENKINSOPP 1996:495-5 18, with earl ier literature; Ml LGROM 1999:10-22, with ear lier literature.

418 N. Na'aman [UF 31

The date of 1 Kgs 8:65 requires clarification. The description of Solomon's founding and consecration of the temple is the focus of an extensive Priestly editorial work (HUROWITZ 1992:263-270; VAN SETERS 1997 :52-53; NA'AMAN 1999:44-46). HUROWITZ demonstrated how extensive the Priestly reworking and expansion of 1 Kgs 8:1-11 is. In my opinion, the Priestly expans ion in 8:62-66 is no less extensive. The o rig inal text probably included only vv. 62-63, and the episode of the dedication of the temple was concluded by the words, "So the king and all the people of Israel dedicated the house of YHWH" (v. 63b). The rest (vv. 64-66) is a late insertion, which, in conj unction with the Pries tly expans ion in v. 2, joined the dedication of the temple to the feast of Booths, and emphasized the element of two feasts of seven days to celebrate a g reat fes tival 5

. The border delineation in v. 65, which marks the northern limit of Solomon's kingdom at Lebo-hamath, was inserted in this redaction, and is not part of the orig inal Deuteronomistic his tory.

Two un equivocal pre-exilic references to Lebo-hamath appear in 2 Kgs 14:25 and Amos 6:14 1

' . T he text of 2 Kgs 14:25, 28 relates that Jeroboam II conquered Damascus and " res to red" the Is raelite border as far as Lebo-hamath, obviously a place on Damascus' northern border. Thus, in pre-exilic texts, Lebo-hamath marked the northern limit of Damascus conquered by Jeroboam 7

, in Priestly texts it marked Canaan's northern border, and in the Book of Ezekiel it marked the northern border of the future Land of Israel. The question arises, what are the relations of these three boundary systems which share the same northern border town ?

In the Deuteronomistic history, the northern border of Canaan is identical with the northern boundary of the tribal allotments. This is indicated by the au thor's emphas is that Canaan was conquered up to its extreme limits (Josh 10:40-42; 11:16-20; J 2:7-8), while the northernmost toponyms he mentions in the conquest accou nt (Josh. 11:3, 8, 17; 12:7) are identical with the toponyms located on the northern border of the tribal allotments (Josh 19:28-29; see Josh 13:4-6; 2 Sam 24:6-7) (AHARONI 1967:213, 215-217; KALLAl 1975:27-34; 1986, passim; NA'AMAN 1986:39-73). In Num 13:21 and 34:7-9, on the other hand, Canaan's northern border is located further north, at Lebo-hamath. Thus there is a marked difference between the northern extent of Canaan in the Deuteronomis tic and Priestly compositions .

5 The description in vv. 65-66 is closely related to the late tex t of 2 Chr 30:23-26. See MONTGOM ERY 195 1:20 1.

'' So already NOTH 1937:48. 7

ELLIGER 1936:34-73. ELLIGER s uggested that "der Eingang (fbO') nac h Ham ath" , was first the northern border of David's kingdom, becoming later the ideal northern border of the Land of Canaan. NOTH ( 1935:242-248) recognized that Lebo-hamath is a genuine place-name, de noting a town named Lebo and the cpexegetic genitive Hamath. But he mistake nl y ide ntified it in the northe rnmost Golan area, nea r Mount He rmon.

1999) Lcbo-Hamath, ~ubat-llamat h, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 419

T he Dtr historian emphasized in his work the utter destruction of the Canaani tes in all parts of the conquered land (e.g., Josh 10:40; 11:8, 10-12, 14; 21:41-42). To "correct" his descript ion, a post-exilic Dtr redactor (DtrN accord ing to SMEND 1971; 1983; DtrG2 according to BLUM 1997:184-187) wrote and inserted several passages that emphasized the persistence of Canaanite elements w ithin the Land of Canaan, thereby explaining the apostasy of the Is raelites, which led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple and the exile. Among the passages that he wro te are the descriptions of the unconquered southern and northern territories, where non-Israelite elements (Philistines, Aviles, Canaanites, Sidonians, Hivites) remained after the conquest (Josh 13:2-6; 23; Judg 3:1, 3) . In the north he marked the southern extremity of the "remaining land" along the northern boundary of the tribal allotments, and its northern extremity on the line of the northern limit of Mount Lebanon and Lcbo-hamath (NA'AMAN 1986:39-73, wi th earlier li terature). Technically, the territory of the " remaini ng land" bridges the gap between the Deuteronomistic and Priestly northern bound aries of Canaan. However, the systems of the "remaining land" and the Pri estly Land of Canaan share only one toponym (Lebo-hamath), whereas al l other border points mentioned in the two descriptions are different. In light of these d ifferences, it is unlikely that the author of Josh 13:2-6 and Judg 3:1 , 3 conceived the Priestly Land of Canaan and referred to it in his delineation of the " remaining land" . Rather, the two authors marked the boundary along the same line, which was a frontier for hundred years (see below) .

T his short introduction demonstrates the importance of the borderline in which Lebo-hamath has a central place for biblical historiography, and raises the problem of the history of the border and its relation to the biblical boundary systems mention eel above. In the next three parts of the article I will discuss the history of the border near Lebo-hamath from the Late Bronze Age down to the Pers ian period. In light of thi s reconstruction I will try to clarify the chronological and territo rial relations between the history of this border and the various biblical descrip ti ons which in tegrate this remote borderline within Is rael ite configurations of the borders .

2. Lab'u in the Egyptian Sources of the New Kingdom The c ity of Lab' u is mentioned several times in Egyptian inscrip tions of the

second millenn ium BCE ~ . It appears for the fi rs t time in the Execration texts (No 31, 1-b-y) of the early 18th century BCE. It is further mentioned in the topographical list of T hutmose III (No 82, 1-bw-') among the other cities conquered in his first campaign to Canaan (1457 BCE). There it appears next to Henne! (h-r-m-i-f), wh ich is doub tless identified with the present-day town elHerme l, located abou t 20 kms. southwest of Qidsu (Tell Nebi Mend). In fact, the entire g roup of toponyms in which Lab 'u and Henne! are included (Nos 72-85)

x For a lis t of re ferences, see A HITUV 1984: l3 1.

420 N. Na'aman (UF 31

is located west and cast of the Orontes River, in the area between the sources of the Orontes and Qidsu '1. T his is the territory called Tabsi in the Egyptian inscriptions, identified with the territory of the strong central Syrian kingdom of Qidsu 111

.

Lab'u is mentioned in Am enophis Il 's inscription of his seventh year (1421 BCE). On his way back from central Syria, the Egyptian king arrived in Qidsu, and after the surrender of its ruler, he shot at two copper targets on the south s ide of the city and conducted large scale hunt in Lab'u (l-bi-w). From Lab'u he proceeded to ljasabu (Tell Hash be), located in the northern part of the southern Beqa' of Lebanon (EDEL 1953:146-156; HELCK 1971:157-160).

Lab' u is not mentioned in the Amarna letters 11• Ramesses II mentions Lab'u

in conjunction with his campaign to Qidsu in his fifth ye.ar (1275 BCE). In the "Poem", he describes how the Hittites attacked him at Qidsu, whi le the division of Rc' was still crossing the ford south of Sabtuna, a distance of one iter (about 10.5 km) south of his camp, the d ivis ion of Ptah was south of the city of Arnam (= Bermel), and the d ivision of Sutch was still on the march, far from the battlefiel d. In one of the relief he refers to the march of his divis ion, stating that when the batt le began the divisions of Re' and Ptah had not yet arrived and their sold iers were sti ll in the forest of Lab' u (l-bw- '). T hus it is clear that the forest of Lab'u is located in the area of the modern vi llage Lebwe, south of modern elHenncl (Arnam). Both the inscript ion of Amenophis II and that of Ramesses II mention a forested area near Lab'u, which lies between the sources of the Li~ani and Orontcs Rivers (EDEL 1952:258; RAINEY 1971:145-146, 149; KUSCHKE 1979; KITCHEN 1982:52-56; MAYER/OPIFICIUS-MAYER 1994).

We may concl ude that Lab' u was a town on the southern border of the kingdom of Qidsu, ncar the northern boundary of the Egyptian province in Asia. It was conquerryd by Thutmose III in his first campaign (1457 BCE), but in his late years was held by the king of Qidsu, a vassal of the king of Mitanni. Amenophis 'fi 's campaign along the Orontes River had no last ing effect. When sometime later, Egypt and Mitanni concluded a peace treaty, the border between the ir vassal s tates passed near the watershed between the southern Beqa' of Lebanon (' Amqi) and the k ingdom of Qidsu (Tabs i). With the collapse of Mitann i and the conquest of its territories by Hatti , fights along the border zones of the two empires broke once aga in. Set i I, and Ramesses II in his early years, tried to push the border northward and attacked the kingdoms of Qidsu and

'1 For identi fi cations and earlier literatu re, see ASTOUR 199 1:64 and n. 54. 111 GARDINER 1947: 150*- 15 1 *; HELCK 1971:270-27 1. For a list of references to Tabsi, see AHITUV 1984: 185- 187, with add itional literature in n. 575. 11 It goes wi thout saying that Lab 'u is not identica l with Labana, a c ity-state mentioned in the topographical inscription of Thutmose Ill (No 10) and in severa l Amarna letters (EA 53:35, 57; 54:27, 32). Tiwatc{fcuwatti , the ruler of Labana, was an ally of Arzawiya of Ruhiss i, and the ir scats must be sought near the borders of Qidsu. For an erroneous identification of Lab ' u and Labana, see AHARON I 1967:66, 137, 147.

1 999] Lebo- I tamath, ~uba t -llamath, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 42 1

Amurru. But in spi te of ini tial Egyptian military successes, Hatti succeeded in defending its territories, and when peace treaty was concluded between Ramcsscs II and Ilattusil i Ill ( L259 13CE), the border between the two empires remained unchanged . Qidsu remained in Hittite hands and Lab'u, its southernmost town, became once again a border town ncar the northern boundary of the Egyptian empire.

Lab' u is common ly ident ified with Tell Qa~r Lebwe, a site ncar the modern village of Lebwe (sec ELLIGER 1936:44-45; MAISLER (MAZAR) 1946:91-102; EDEL 1952:1 53-154; KUSCHKE 1958:96-97; NORTH 1970/71:87-92). Accord ing to the surveys conducted at the s ite, the tell is quite small, its upper terrace covers an area of about 100x80 m. It was occupied for thousands of years, including the Late Bronze Age (KUSCHKE 1954:128; KUSCHKE/MIITMANN/MULLER/AZOURI L976:24-27; MARFOE 1995:271-272). These findings match the conclusions drawn from the documentary evidence. It is clear that Lab'u was a small border town located near the sources of the Orontcs River, in a forested area. Its importance was due to its strategic location, on the front ier between the empires of Egypt and Mitanni/Hatti, and between the citystates of the southern Bcqa' and the kingdom of Qidsu. From a Canaanite point of view, Lab'u marked the entrance to Qidsu when leaving the territories under Egypti an con trol.

3. The City of Lab' u and the Province of ~ubat in Neo-Assyrian Texts The earl iest ex tra-biblical reference to Lab'u in the fi rst millennium BCE is

in Tiglath-pi leser Ill 's list of towns, in wh ich they are arranged in groups according to country (TADMOR 1994: 144-149). In Col. II, after the town lists of BitAgusi (Arpad), Unqi and Hamath, the ci ty of Lab'u (uRULa-ab-'u-u) is mentioned ( line 25), and then the text breaks. Lab'u most probably heads the city list of Blt-ljazail i (Damascus), and is not a city of Hamath.

A group of letters from the time of T iglath-pilcscr III and Sargon II refer to the Assyri an prov ince of ~ubat/~ubite 12

• These letters are our main source for the measures taken by the Assy rians to establish and consolidate their new province. While many scholars have discussed the documentary evidence for the scope and adminis tra tion of Canaan in the second millennium, the border system in southern Syria in the first millennium BCE has not been sufficiently clarified 13 Because of the importance of the Assyrian sources for establishing ~ubat's scope and its place in the system of Assyrian provinces in southern Syria, I will d iscuss these in deta il , beginning wi th the two early letters from the time of Tiglath-pilcser Ill.

12 The province's name has severa l va riants (.}'u-p/bat, -~·u-ba-te, .~u-pi-te) and I will write it down ~ubat. For the spelling, sec WEIPPERT 1972:1 59-160. 13 The most detai led works o n the place and scope of biblical Aram Zobah and the Assyrian province ~uba t in the first millennium were written in the 1930s. See ELLIGER 1936:34-73; NOTH 1937:36-48; LEWY 1944:443-454; ALT 1945:1 47-159. For recent literature, see D10N 1997: 172-176.

422 N. Na'aman (UF 31

(l) Lette r ND 2644 (NL 23) was probably written soon after Tiglath-pileser's campaigns of 733/32, when he conquered the kingdom of Damascus and annexed it to the Assyrian territory (SAGGS 1955:142-143; EPH'AL 1982:94). It is a draft of the " king's order" to a certain Nabu-belu-u~ur, who was possibly a high-ranking officer. In the first part of the letter, the king instructs his officer concerning the Arabs (lines 3-18). Lines 18-24 may tentatively be rendered thus : "Until . .. they should inform you (tl-sa~-ka-mu-k[ a]) of the road of vRuTa-ab/p-1[/-x], just as the forts of [GN 1], of Ni'u, of Qidisi and of [GN2]". T he direction of the Ta -ab/p-l[/-x] route is not known. Ni' u (Qal'at el-Mudiq) 14 is located on the kingdom of Hamath 's northern border with the Assyrian province of Ijatarikka, and Qid isi on I-Iamath's southern border with the newly established province of ~ubat. The need for information concerning the route and forts indicates that the prefect had only recently been appointed to his post.

The last part of the letter deals with harvesting of the sown-land that the author of the letter cu lti vated. (2) ND 2766 (NL 70) is a letter of a certain Samas-abu-iddina to Tiglath-pileser (SAGGS 1963:79-80). He was appointed to guard the city of Rabie (Riblah), w ith the instructions: "Let half of the draught animals come into Rabie and the other half let go into Qidisi". The next part of the letter is broken, and the au thor of the letter poss ibly discusses the feeding and guarding of the draught animals. In the las t part of the letter he asks for guards and adds that " the towns into which they have brought the draught animals arc w ithin the steppe (mudabiru)".

A certain 111A-i-ni-i/u appears in a broken passage (line 12), and Saggs identified him with Eni-ilu, the king of Hamath, whom Tiglath-pileser placed on the throne after conquering it in 738 BCE (SAGGS 1963:80; WEIPPERT 1973A:44-45, n. 72).

The letter ill ustrates the early stage of the organization of the province of ~ubat immediately after its annexation by T iglath-pileser III, in 732 BCE.

The next seven letters of the time of Sargon II were transcribed and translated by PARPOLA (1987) in his edi tion of the correspondence of Sargon, and the num bers at the beginning of each letter (No 175, etc) refer to his publication 1.

5•

(3) No 175 (ND 2381; NL 19) was sent by Adda-l]ati, the governor of Hamath, to Sargon. He reports that Ammi-li 'ti, an Arab leader, with 300 she-camels, in tended to attack Assyrian booty being transferred from Damascus to Assyria, and that he went wi th Bel-liqbi, the prefect of ~ubat, to meet the booty bearers. The continuation of the letter is partly broken, but it seems that Ammi-li' ti succeeded in seizing part of the booty and successfully escaped the pursuing force.

14 The ident ificat ion of the fort of Ni 'u with the Late Bronze central Syrian city of Niya (KLENGEL 1969:58-74) is to be preferred to its identification with Neia, mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum and located along one of the routes connecting Palmyra with Damascus or l~ oms (ODED 1964:273 n. 13; EPH'AL 1982:94 n. 309). 15 See also the detailed review of WATANABE 199 1: 194-195.

t 999) Lcbo-ll anwth, ~ubat- llama th , and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 423

It is possible that reports of this kind gave rise to the campaign against the Arabs in 7 16 BCE, and that letters Nos 173-174 (ABL 224-225) were sent immediately afterwards 16

• They both report that "we have not heard anything specific about the Arabs s ince the king, my lord, went to Assyria; all is well". ( 4) Letter No 176 (ND 2437; NL 20) was sent by Adda-hat i to S argon. He first reports that he received the silver dues from the commandants and village managers, and sent them to the king together with his gift.

In the next paragraph he complains that his manpower is reduced by 500 men . After a broken passage he asks to transfer men from A[rgite?], possibly a city in a neighbou ring province (see below), to the provincial centre at ~ [ubat]. He then states that he harvested the fields of uRuHi-x[xx] (Henne!?) and uRuLaba-'u-u (Laba' u), and asks for Assyrian and Itu'ean troops to hold the steppe (madbar). Then he adds: " there is no Assyrian city-overseer, nor any Assyrian gate-guards in ~ubat".

In the last paragraph, Adda- l]ati cites the king's order to mobilize the people " living on the mounds" for building operations, and asks permission to mobil ize the "ten for ti fied towns in the steppe (madbar)". There must have been extensive building operati ons in the new provinces in the time of Tiglath-pileser III and Sargon II and manpower was badly needed. Also there was the constant threat from the AJabs, and troops were in need to defend the old and new settlements located on the east-Sy rian front of the Assyrian empire. Therefore, anyone who could be was conscripted for bu ilding and defense operations. (5) No 177 (ABL 414) is a letter sent by Bcl-l iqbi, the prefect of ~ubat, to Sargon (ALT 1945: 153-159; EPH' AL 1982:95-97). The letter discusses the affa irs of two road-stations, Ijcsa and Sazana. Ijcsa is identified as present-day ~Ias i yeh, a village located on the ~!oms-Damascus road, at the northern extremity of Mount Ant i-Lebanon. Bcl-liqbi complains that the station is short of people, and asks the king to send him 30 families to be settled there. In order to make room for these families, he wanted to evacuate a group of craftsmen who belonged to NabO-usall a, a neighbouring prefect, and temporarily stationed in Hcsa, and settle them in Argite, a town of the latter prefect 17

. He further asks tl1C king to send an official (called Ya' iru) to supervise the road station of Ijesa, and ano ther official (call ed S in-idcl ina) to supervise Sazana. The latter should be sough t along the modern ~!oms-Damascus road, either north or south of Hesa 1x.

1r' For Sargon 's 7 16 BCE campaign against the Arabs, see TADMOR 1958:77-78; EPH 'AL 1982:36-39, 105-1 11. 17 Argitc is poss ib ly identica l to uRu lja-ar-ge-e, mentioned in the Annals of Ashurbanipal before " the district or ~ubitc" (see EPH ' AL 1982:97, with earlier references). WEIPPERT ( 19738:61 -63) suggested that most of the places mentioned by Ashu rbanipal were admin i ~tra tive districts of the Assyrian empire. If this is indeed the case, Argile may have been the centre of a sub-d istrict in the province of NabG-u~a 1la.

" For the identificatio n of Sazana, sec EPH 'A L 1971; NA'AMAN 1988:189-190.

424 N. Na'aman (UF 31

In the last paragraph of the letter, Bcl-liqbi reports that Ammi-li ' ti arrived at the provincial centre of ~ubat, a move that ind icates a state of temporary peaceful relat ions between the Assyrian authorities and the Arabs. (6) Letter No 179 (Cr 53 I 0) was again sen t by Bci-Iiqbi to Sargon. He firs t reports tha t Arabs stayed out of his towns, entered there temporarily and left. Arabian fa rmers and gardeners d id en ter h is towns, while others built sheepfolds on their o utskirts. It is c lear that the Assyrian activity in the province a ttracted the pastoral nomadic clements to draw near the towns or enter them. T he Assyr ian autho rities did not trus t the A rabs, and Bei-Iiqbi ordered to expel them and destroy their yards . He then negotiated with their leader, Ammi-li ' ti , and suggested that the Arabs s hould settle in the land of Yasubuq. Provided that Yasubuq is identical to the land of Yasbuq, whose king (l3ur-Anate) joined the coalition that foug ht S halmancscr III in 858 BCE (Grayson 1996: 17), it may be located on the no rtheastern periphery of the province of ~ubat, possibly on the eastern fro nt of the former kingdom of IIamath.

The Assyrian k ing prohibited selling iro n to the A rabs, and to enforce the prohibitio n he placed Assy rian toll coll ectors in ~ubat, the provincial capital, and in Ijuzaza, a central town located on the province's periphery. The toll collector of ljuzaza charged th at Bel-liqbi 's agents sold iron to the Arabs . In his defence, the prefect cl aims that he did business only in ~ubat, and that his agents in ljuzaza sold only g rapes to the Arabs. Ile further adds that he did sell iron to the captives, bu t not to the Arabs. (7) Lette r No 180 (CT 53 199) was sent by Bei-Iiqbi, but is badly broken. He reports that Ammi -li ' ti has encamped near the city of Rabie and cam e to see him (the rest is broken). (8) Letter No 181 (ABL 1070) was probably sent by Bcl-liqbi to Sargon. The letter illus tra tcs,the Assyrian system of suppl y of g rain to troops s tationed in the province. T he g ra in was sto red in scaled depots located in v illages under the superv ision () [' the prefect, and the p refect was responsible for its distribution, and instructed the deputies in accordance with the o rders he received from his superiors . Unfo rtunately, no toponym is mentio ned in the le tter. (9) Lette r No 182 (C r 53 588) again deals w ith the problem of grain storage and distribution, but it is badly bro ken.

The nine lette rs s hed lig ht on two main aspects: (a) the internal organization of the province of ~ubat , its extent and main towns; (b) the relations of the Assyrians w ith the A rabs, and the measures taken to supervise their movements and min imize their danger.

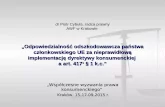

The location o f the p rovincial centre of ~ubat is unknown. Tentatively, I s ugges t locat ing it ncar the present-day Qu~er, halfway between Q idisi/Qidsu and Rable/Ri blah, a p lace w hich was an anc ient c rossroad on the northward route (KUSCI IKE 1979: 9, 30-35). Such identification may explain its central place in all contac ts wi th the A rabs and in the o rganization of the province.

The te rritory of ~uba t extended between Qidis i in the no rth and Lab 'u in the south. In the wes t it must have reached the northern slopes of Mount Lebanon, and in the cast it bo rde red on the desert. Some of its towns can be identi fied

1999] Lebo-llamath, ~uhat- l lamath, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 425

(Lab'u, Rabie, Qidis i, l}csa, and possibly ~ubat and Hcrmcl), and some remain unidentified (IJuzaza, Sazana). Many small peripheral villages and manors whose names rema in unknown were included in the province (note in particular letter No 176).

0 101cm.

~ '\ 0 ~

ei- Hermel \>- • tteso • '\~ \.)<0 ~ 'r'~ kJ Q:- ~ -.1 '!"'

1--~

.:::::>

&: 0 ~ .#

!J "'-.../ ..

i:::-~

~ c? ~

Bo 'lbekk • Nobek .. I • ...

(Map)

426 N. Na'~man [UF 3 1

4. $ubat-Hamath under the Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian Empires The most surpris ing aspect of the correspondence is the involvement of

Adda-bati, governor of IIamath, in the affairs of the province of $ubat (Nos 175-176). What might have been the relations between the two neighbouring districts? It must be emphasized that an Assyrian province of IIamath is nowhere

b. llJ unam tguously attested. There was no eponym from Hamath, nor is Hamath ment ioned in administrative lists that enumerate Western provinces. It only appears in K4384, a geographical list of names of provinces, cities, mountains and tribal ethnonyms (FORRER 1920:52-53; FALES/POSTGATE 1995:XIIIXIY, 4-6), and in Sargon's Ann als of the year 711 (LANDSBERGER 1948:73-74; FUCHS 1998:43, 72). The former text is usually dated by scholars to Ashurbanipal 's reign, but it may equally well be elated to the late years of Sargon II, enumerating the lands and cities subject to him, or situated near the borders of his empire. Attributing K4384 to Sargon may explain why the list of toponyms opens with Babylon, which he conquered in 709 BCE, and closes with Dur-Sarruken, which he consecrated in 707 BCE. The list may have served as a source for scribes who wrote royal inscriptions for Sargon's new capital and, li ke other Sargonic texts, was transferred by Sennacherib from Dur-Sarruken to the new capital of Nineveh.

1-Iamath is mentioned twice in this list: unuHa-ma-a [t-tu] (Rev. I 8) and unuSu-bat unu!Ja-ma-a-[tu] (Rev. I 12). FALES/POSTGATE (1995:XIV) noted that two geographically adjoining or administrat ively associated, places arc sometimes listed on the same line. We may suggest that following its conquest, part of 1-Iamath 's territories were annexed to $ubat, and the author of K4384 called the expanded province by the name $ubat-IIamath. J\dda-hati, the author of letters 173- J 76, was probably the mi li tary governor of the ne~ly conquered kingdom of Ilamath, whereas Bcl-l iqbi was the prefect of the expanded province of $ubat. This 'may explain why they both operated in the same territory and cooperated ill military operations conducted against the Arabs.

The prism fragment K.1672 describes the mobilizing of troops of Western prov inces' governors for campaign against Ambaris of Tabal (713 BCE). The text (lines 3-8) is badly broken, but may tentatively be restored thus (compare LANDSBERGER 1949:73; FUCIIS 1998:72):

... my eunuchs, [the governors] of the ci ties of Sam'al, [of $ubat??], of Ilamath, of Damascus, [of J_latarikka??], with my cavalry [which m]y [commanders] stat ioned in the lands of Ilamath [and ljatarikka??] . ..

Landsberger and Fuchs restored in line 4 [unuAr-pa-ad-da]. However, in light (. I d" . b URU o t 1e tscusston a ovc I suggest restoring it [ Su-ba t] , assuming that the text

refers to the new province of $ubat-IIamath. Letters ND 2495 (NL 88) and ABL 1070 (PARPOLJ\ l987:Nos 172 and 181) indicate that following Sargon's campaign of 720 BCE, troops and cavalry were stat ioned in Western provinces.

1'' T his point was pa rti cularly emphas ized in the works of HAWKI NS (1972-75:69; 1987-

90:343; 1995:97).

1999] Lebo-llamalh, ~ubal- ll amalh, and lhe northern boundary ol lhe land od Canaan 427

This is the basis for my tentative restoration of lines 6-8. Did the province of ~ubat- IIamath include all the areas of the former

kingdom of I !a math, or only its eastern parts? Did the Assyrians establish a ~1cw province on llamath 's western areas, or did they annex it to another pro:m~c (i.e., I}atarikka)? The question is linked with the location of Man~uate, whtch ts referred to as a Syrian province in the Assyrian sources.

Mansuiitc is mentioned in the Eponym Chronicle of year 796 BCE, in a letter dated t~ the time of either Tiglath-pilescr or Sargon (NL 22), and in several Assyrian administrative lists ~~~ . Its prefect was an Assyrian eponym for the year 680 BCE, th ree years after the prefect of $ubat held this honorary _office (683 BCE). The Assyrian administrative lists suggest a general locatton of Man!?uatc between !Iamath and Damascus, but they do not provide a more

precise location. Two possible locations have been offered for Man~uatc: either in the southern

Bcqii' of Lebanon, in the areas of the former kingdom of Beth Rehab, or in the southern territory of 1-Iamath. According to the first suggestion, the name Mansuate evolved to the !Icllenistic-Roman place name Massyas, which acco~ding to Strabo denoted the Beqa' of Lebanon between Qidsu and Chalkis (I!ONIGMJ\NN 1924:15-16; ZADOK 1977:56; WEIPPERT 1992:49-53, with earlier literature). Accord ing to the second suggestion, the name Man!?uatc evolved to the present-day Ma~yiif (al ias Ma~yiid, Ma~yiit, Ma~ya0, 45 kms. west-southwes t of Tel J::Iamii, at the southeastern foot of Jebel cl -An~ariych (LIPINSKI 1971).

Locating Man~uate in the area of present-clay Ma~yiif/Ma~yiit may be supported by Amcnophis II 's inscription, which describes the king's campaign in his seventh year (EDEL 1953: 146-153; IIELCK 1971: 158-159). In this campaign he moved along the Orontcs River from Niya (Qal'at el-Mudiq) to 'kt

2\ and then

arrived to Salhi 22. In my opinion, the land of Salbi is the ancient name of present-day el-G hab, a marshy area which the Pharaoh crossed from cast to west. I le then continued southward along Jebel cl -An~ariyeh , and on his way to Qidsu plundered the vill ages of Mncjt (m-n-cj3-t-w) 23

. The identification of Mncjt with present-day Ma~yiif/Ma~yiit is self-evident. This identification may support the proposed identification of Man~uiite with present-day Ma~yiif/Ma~yiit.

Mansuatc is further mentioned in a letter from Nimrud (ND 2680; NL 22), which ~mfortuna tcly is quite damaged (SAGGS 1955:141-142; DELLER

20 HAWKINS 1987/90:342-343, w ith earlier li teratu re; FALES/POSTGATE 1995: Nos 1, 2, 6; 1992: No 11 6. ZADOK ( 1977:56) suggested deriving the name Man~uat e from the root N-!?-W " to quarrel, slri ve", and noted that the meaning may suit a border district.

21 For the location of the c ity of 'kl , see ASTOUR 1981 : 13- 14.

22 For the land of Salbi , see KLENGEL 1970:5, 22 n.2; ASTOUR 1995:67.

~ 3 T he idcnlifi cation of Mmft of lhe Memphis s lele of Amenophis II with Assyrian Man~uii t e was fi rs! s uggested by 1\STO UR 1963:235. For c ritic is m, see WEIPPERT

1992:52 n. 68.

428 N. Na'aman [UF 31

1961:252, 254). Since the letter may contribute to the discussion of the location of Man~uatc, I wi ll first present a translation ami then discuss it: 24

(Beginning destroyed) ... among the la[ter] captives that the king, my lord, gave to [me/him] from T il Ba[rs ip), I say/said: " lie should know th[at] indeed there arc n[o ... ) among them". 1-Iara-ammu, the chili arch of Mansuate, came for me. He has ;cnt his f ive sons [to ..... but the rejst of [his) people [are with) him. O n the 30th clay [of ... the m]cn/ [so)ldiers ar[rivcd) . I told [thc)ir comrades that I would release and sett le them, but their brothers d id not agree, and said: "The men/sold iers· are traitors/criminals. They wi ll leave and run away. T hey have been plo[tt ing] mur[ der]". Why do [these] men/soldiers . . . (end of the letter broken)

According to th is resto ration, the commander of Man~uate is mentioned in conjunction w ith the settlement of Assyrian men/soldiers, who are accused of being traito rs/criminals and of plott ing murder. Sargon II inscriptions s tate that he settled in the land of Hamath 6300 Assyrians who had rebelled against h im 25

. It is tempting to combine our le tter with Sargon's royal inscrip tions and assume that its author refers to problems emanating from the settlements of the Assyrian rebels in the city of Man~uate. Provided that this interpretation is accepted, it indicates that Man~uatc is indeed located in the territory of the fo rmer kingdom of Hamath . The province of Man~uatc probably encompassed the west O rontcs distric ts of 1-Iamath, whereas its cast Orontcs districts were annexed to the province of ~ubat.

The southern' Beqa' of Lebanon, where some scholars located Man~uate, is a rela tively ~ma ll area, not befitt ing a separate Assyrian province. It was probably included in the province of Damascus which, like the province of ~ubat-II amath, included territories on both s ides of Mount Anti-Lebanon.

Further ev idence for the assumption that Ilamath and ~ubat were included in the same province comes from a Nco-Babylonian chronicle. During the struggle between Babylon and Egypt after the fa ll of Assyria, the city of Riblah " in the land of Hamath" served as the Egypt ian headquarters (2 Kgs 23:33). After the battle of Carchemish in 605 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar pursued the Egyptian fugitives, and defeated them in " the province (pf~a t) of Hamath" (GRAYSO N 1975:99 lines 6-7) . The fug itives must have re treated from Carchcmish towards the centre of Rablc/Riblah, located in the province of I-Iamath, but did not reach the place. A fter h is v ictory over the Egyptians, Ncbuchadnczzar established his

24 I am gratefu l to Professor SIM O PARPOLA, who provided me with a transliteration and translation of this difficult letter. 25 See FUCHS 1994:42 1 s.v. Amatlu , with earl ier literature.

1999] Lebo-ll anwth, $ubat-llanwth, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 429

headquarters in Riblah, "in the land of Ilamath", the former Egyptian centre (2 Kgs 25:6, 20-2 1) . According to a Nco-Babylonian contract dated to Ncbuchad nczzar II 40th year (565 BCE), Qidisi (uRuQf-di-is) was then the capital of the

province (JOANNES 1982:37 No 4). In the Book of Chronicles, Solomon's conquests in Syria arc described as

follows (2 Chr 8:3-4): "And Solomon went to Ham ath-Zobah and took it. lie built Tadmor in the wilderness and all the store c ities which he built in Ilamath." Scholars agree that in many instances, the Babylonian and Persian provinces inheri ted the Assyrian province system. The scope of the province of HamathZobah of the Chronicler's tim e (about mid-fourth century BCE), may be roughly the same as that of the Assyrian province of ~ubat-IIamath. The oasis of Tadmor/Palmyra was probably annexed to the province, either by the Assyrians or later by the Babylonians and Persians. The Chronicler, who sought to magnify Solomon and describe his conquests beyond those of his father, attributed him the conquest of Jlamath-Zobah and the building of its cities, including the city of Tadmor ~6 . We may conclude that from the time of Sargon II down to the late Persian period , ~ubat and the eastern dis tric ts of Ilamath were included in a unified province governed by its own prefect.

We arc now able to better analyze the biblical references to Lcbo-hamath. Before the Assyrian annexations of 732 BCE, the city of Lab'u was a Damascene city, located on the southernmost end of the large district of ~ubat. It was s ituated about 45 kms. south of the border of llamath, and could hardly have been called " Lebo-hamath". Only after the Assyrian aimexat ion of Ilamath in 720 BCE, and the reo rganization of the provinces of central Syria, when Lab' u became the southernmost town of the unified province of ~ubat-IIamath, was it appropriate to call it by a name that connected it to Ilamath. From the late seventh century down to the fourth century BCE, Lab'u was the southern town of the province of ~ubat - llamath/!Iamath-Zobah, the province of Damascus' northern neighbour. T he use of the combined name Lcbo-IIamath by scribes who worked during this long period is only natural.

Since the combined name Lcbo-hamath did not antedate the Assyrian a1mexat ion of I Iamath in 720 13CE, its inclus ion in reference to the time of Jeroboam II (2 Kgs 14:25; Amos 6:14) is anachronistic. It may have emerged as a result of a reworking and updating of the early sources by the author of the Book of Kings (the Ocutcronomistic historian), and by a late editor of the Book of /\mos. The inclus ion of the combined name in all the o ther biblical references is due to the late date (no earlier than the exilic period) in which they were put

in wri t ing.

21' ELLIG ER 1936:52 n. 2, 56-57 n. 4; NOTH t 937:4 1-42, 45-47; RUDOLPH t 955:2 19;

contra WILLI 1972:75-78. lt goes without say 1ng that no source other than the Book of Kings was avai lable to the Chronicler, and that the account in 2 Kgs 8:3-4 is nonhistorical; cont ra MALAMAT t963 :6-8; AHARONI 1967:275.

430 N. Na 'aman [UF 31

5. The Northern Borde1· of the Futu re Land of ls1·ael in Ezekiel 47 A delineation of the ideal borders of Is rael appears in Ezekiel ' s vision

of YIIWII's re turn ing to the temple and es tablishing his res idence in Jerusalem in the mids t of his people. The delineated territory in Ezek 47:13-23 is YHWH 's land, apportioned and divided among the twelve tribes of Israel.

T here are several features unifying the description of Ezekiel that indicate that it was written by a sing le author according to a definite plan. (I) The description moves in a clockwise c ircle and ends where it began; (2) Each s ide opens by " to/on the . . . s ide" (1/wp 't) and ends with "this shall be the ... s ide" (z't p't); (3) The autho r did not usc verbal forms to connect the toponyms, unlike the descriptions of the tribal al lotments (Joshua 13-19), and the boundaries of Canaan (Numbers 34); (4) Each s ide ends with the name of a certain toponym, which is repeated at the s tart of the next s ide:

(a) The description of the northern s ide (vv. 15-16) ends with the words, "which is on the border of Ilauran". V. 18 opens thus: "On the east side: between Ilauran . .. ". V. 17 reiterates in a summarized form what was already described in vv. 15-16. At the beginning of v. 18, the author chose to refer back to the end of the more detailed description in vv. 15-16, rather than to v. 17.

(b) The demarcation of the eastern side (v. 18) ends with the words, "as far as Tamar" (with LXX and the Syriac). 27 V. 19 opens thus: "On the south s ide: from Tamar. .. " .

(c) The delineat ion of the southern s ide (V. 19) ends w ith the .words, "to the Great Sea". V. 20 opens thus : "On the west side: the Great Sea ... " .

(d) " The demarcat ion of the western s ide (v. 20) ends with the words, "as far as opposite Lcbo-hamath", which was the first town marked on the northern border 28

•

(5) On th ree s ides, there arc abbreviated reiterations of all the above, or of part of what was already described. These reiterations open with the words, "so the boundary shall run from .. . " (v. 17) ; " from the boundary to ... " (v. 18); " from the boundary as far as ... " (v. 20). Some scholars did no t realize the principle of reiteration and inserted unnecessari ly textual corrections to the texts in vv. 18 and 20 (reading magbrt in place of MT mig"b ' f) (sec BARTHELEMY 1992:425-426).

27 T he ve rbal form tiimodtl ("yo u s hall measure") is ali en to Ezekiel's description, which docs not usc verbal forms, and the correct reading liimii riilr ("as far as Tamar") was recognized by a ll scholars. Sec e.g., ZIMM ERLI 1983:5 19-520; BARTHELEMY 1992 :425-426, with earlier literature. 2~ ror the correct rendering of v. 15, sec ZIMM ERLI 1983:5 18; BARTHELEMY 1992:4 19.

1 999) Lcbo- l lamath, ~uhat- llamath, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 431

The description of the ideal Land of Israel in Ezekiel 47:13-23 is original in all its parts, and refl ects the prophet's broad familiarity with the borders and areas he delineated. T he bas is for his description was the system of provinces of his time in southern Syria and Palestine. The author knew many more toponyms along the northern boundary than on the eastern and southern borders. No wonder that the latter bo rders are only schematically delineated. T here arc no textual contacts between Ezekiel's delineat ion of the southern border (v. 19) and that of Num 34:3-5 and Josh 15 :1-4 although they describe the same line. The name, " the waters of Meribath-kasdcsh" (v. 19), may indicate that Ezekiel's source for the southern border was literary, possibly Ex 17:7 , Num 20:13, 24, or Deut 33:8. T amar was an Edom ite fort located ncar the former boundary of the kingdom of Judah, and was probably known to the prophet from his earl y

. J I 2<J years 111 erusa em .

Ezekiel's description of the northern boundary runs as follows (vv. J 5b- 17): (15b-16) On the north s ide: from the Great Sea the way of Hcthlon, Lcbo-hamath to Zcdad - Berothah (and) Sibraim, which lie between the territory Damascus and the territory of Hamath - as far as Ilazcr-hattichon 30

, which lies on the border of Hauran. (17) So the boundary shall run from the sea to Hazar-cnon, that is, the territory of Damascus and no rth, on the north lies the territory of Hamath.

T he boundary is again described in Ezck 48:1b: Beginning at the no rthern extreme: along the way of Ilcthlon, Lcbo-hamath, Ilazar-cnan, the terri tory of Damascus, on the north along the territory of Hamath . . .

The boundary ran from the sea to a place called Ilcth lon, which has been identified w ith present-day Hctcla, a v illage located northeast of Tripoli and south of Nahr cl-Kcbir (FU RRER 1885:27; ELLIGER 1936:70). It continued to Lebo-hamath and to Zcdad (present-day ~adad), on the edge of the desert. Before proceeding southward, the author adds two other places - Bcrothah and S ibraim - located between Lcbo-hamath and Zedad along the Damascus-Hamath border. Bcrothah is mentioned in 2 Sam 8,8 (written Bcro thai) as a city of Hadadczer, king of Zobah, and is usually identi fied with present-day Brita! ,

2'' r or the recent excavatio ns at the site of Tamar ('En Hazcvii), sec COl i EN/ YISR/\ EL 1995; 1996; BECK 1996. 30 There is no textua l basis fo r reading Haze r-cno n in place o f 1-lazcr-hatt ic hon, as suggested by some scholars. Sec COOKE 1936:530; FOI-IRER 1955:257; Z IMMERLI 1983:5 18. Hazar-e non was located at the easte rn end of the Damascus -llamath borde r, w he reas Hazer-hatticho n was located o n the northern end of the Damascus-Hauran border. For discussion, see BARTH ELEMY 1992:420.

432 N. Na'aman (UF 31

south of Ba'lbck. However, no ancient si te was found ncar Brita! (KUSCHKE 1954: 122-123; 1958:98-99; MARFOE 1994:245-247), so that the location of Berothah/i rema ins uncerta in . The place of S ibraim is also unknown. The two places must be sought near the Damascus-llamath border, either on its northern o r southern s ide.

From Zcdad, the border ran to Ilazar-enan, no doubt a s ite on the edge of the desert, which was sometimes identified with present-day Qaryaten (FURRER 1885:28; ELLIGER 1936:66-67). The last toponym mentioned on the northern line is llazcr-hatt ichon, located at the northern end of the Damascus-Hauran border. Locating it depends on the identification of the district of Hauran. Some scholars identified Hauran with the district of IIawwarin, w hich is mentioned once in the Annals of Ashurbanipal 31

• However, since 'the eastern boundary of the Land of Israel passed between the districts of Hauran and Damascus (Ezek 47,18), Ilauran was probably the name of an eastern district that covered the territory of the Assyrian province of Qarnini and encompassed the areas of the Ilauran and Bashan. Hazcr-hattichon s hould be located on Hauran's northwest corner, far south from Hazar-cnan. The northeastern-eastern boundary delineated by Ezekiel probably ran from Qaryatcn (Ilazar-enan) southward, passing cast of Damascus and up to the Yarmuk River and the Jordan.

We may conclude that Ezekiel's future Land of Israel in the north encompassed the Phoenic ian coast up to Nahr cl-Kebir, the province of Damascus and the west-Jordanian areas, leaving the provinces of Hamath-zobah, Hauran and Gilead outside the territory. The identified places in the northern boundary (Hcthlon, Lcbo-hamath, Zed ad, and possibly I Iazar-enan) are located near the borderl ine, so th at other unidentified towns (e.g., Berothah and Sibraim) must be sought along this line.

6. The Northern Boundary of' the Land of Canaan in Numbers 34 The '((cta ilcd delineat io n of the boundaries of Canaan in Numbers 34 is

part of a block of Priestly material dealing with the theme of the occupation and d istribution of the land (Num 32; 33:50-35:34) 32

. AULD (1980:72-87) examined the relation of Num 33:50-35 :8 to the distribution of the land in the Book of Joshua, and establis hed the priority of Joshua over Numbers for most of the material in question. However, in his discussion of the relat ions of Num 34:3-5 to Josh 15: J -4, he concl uded that "neither text depends on the other, but both on a common list of names." As for the relations of Num 34: 1-12 to Ezck 47: 13-23, he s uggested that although they describe much the same line, " there can be no certainty about literary priority" 33

. Contrary to AULD, I suggest

31 FURRER t885:28; ZIM MERLI 1983:529. For the district of l}aurlna in the annals of Ashurbanipa l, sec WEI PPERT I 9738:62. 32 For discussions o n the boundaries of biblical Canaan, see MAISLER (MAZAR) 1946; AHARON I 1967:6 1-70; S IMONS 1959:98- 103; DEVAUX 1968; 1978: 125- 132. 33 AULD 1980:75-76. llis analysis was accepted by HUTCHENS 1993:222-224.

1999] Lcbo-llamath, ~uhat - llamath, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 433

that Num 34:1- 12 depends on both Josh 15:1-4 and Ezck 47:15-17, and on the description of the dist ribution of the land in Josh 13-19, and is secondary to all these texts.

On the one hand, the extent of the territory demarcated in Numbers 34 is identical w ith that demarcated in Ezekiel 47, although the latter is called Land of Canaan, while the former is called the Land of Israel (Ezek 47: 18). On the other hand, in Ezekiel the land is divided among the 12 tribes, whereas in Numbers it is div ided among the nine-and-a-half tribes. The name Canaan for the inherited land and its divis ion among the nine-and-a-half tribes is common to the territory delineated in Numbers 34 and the tr ibal allotments in Joshua 13-19. Moreover, the duality in the status of Trans jordan- as a territory that, on the o ne hand, lies outside the Promised Land, but, on the other hand, will be occupied and allotted to the two-and-a-half tribes - is common to Numbers 34 (vv. 13-15) and to the tribal allotments 3~. However, the two boundary systems d iffer in extent on their northern side: whereas the northern boundary of the tribal allo tments reached the line of the southern slopes of Mount Hermon - Dan - the Litani River, the Land of Canaan extended further north, up to the line of the northern limi t of Mount Lebanon - Lebo-hamath - Zedad 35

. It seems to me that the author of Numbers 34 combined the boundaries of the future Land of Is rael of Ezekiel 47 with the account of the distribu tion of the land in the dcuteronomistic his tory, and that his boundary system combines these two systems.

There arc several features that unify the descript ion of Numbers 34 and ind icate that it was wri tten by a sing le author according to a unified plan: (1) The descript ion begins at the southeastern extremity of the Dead Sea and moves clockwise on all four sides of the border; (2) Each s ide opens with a s hort, though not identical note; (3) Three sides arc concluded with the words, "and its termination (to~'otiiw) shall be ... " (vv. 5, 9, 12); (4) T he boundary is systematical ly described by verbs in the perfect simple stem, 3rd person si ng. masc., apart from the beginning of the northern and eastern sides, w hich opens with the imperfect 2nd person pl.: "you shall mark out" (vv. 7b and 10). T he appearance of the 2nd pers. pl. follows the structure of 2nd pers. pl. ("to you"), which o pens and closes the de lineation on all four sides; only the usc of the imperfect is exceptional. An exceptional form appears at the beginning of v . 8 ("you shall mark out"), no doubt as an imitation of the verbal form in v. 7b (WAZANA 1998: 1 14); (5) A remarkable feature of the descript ion is the lack of references to adjacent

territories. Unli ke the description o f the boundaries in Ezekiel, which on the

3~ On the duality in the status of Transjordan in Deuteronomy and Joshua, sec WEINFELD 1982:59-75. 35 The northern territory of the " remaining land" (Josh 13:4-6) covers the gap between the two territories; sec N/\' AMAN 1986:39-73, with earl ier literature.

434 N. Na'nman (UF 31

northern and eastern sides refers to neighbouring districts, the border del ineat ion in Numbers 34 entirely ignores all neighbouring districts, except in the introduction in v. 3a (of which sec below). The linear description of the boundaries, which has no parallel in internal or external border descrip tions in the Bible and anc ient Ncar East texts, calls for an explanation. In m y opinion, it is a result of the w ritten sources ava ilable to its author (Josh 15: 1-12; Ezek 47: 13-23), enabling him to draw toponyms and avoid mentioning the territories adjacent to the boundaries he delineated.

The description of the southern and western boundaries of Canaan (Num 34:3-6) is closely related to that of the parallel bo rders of Judah 's inheritance (Josh J 5 : I b-4, 12). The key to the relati onship of the two texts lies in their respective introduc tions. The author of the tribal allotments frequently drew borders in relation to adjacent territo ries. In Josh 15, l b he defined the southern bo rder of Judah in relation to the Edomitc and desert f rontiers: "along the boundary of Edam , to the wilderness of Zin at the fa rthest south." The author of Numbers 34, on the other hand, delineated the borders w ith no reference to neighbouring borders, so that the reference to Edam in v. 3 is exceptional. Moreover, the double mention of the southern s ide in this verse is redundant and the order of the toponyms in v. 3b is cont ra ry to the direction of the boundary ("your south s ide shall be from the wilderness of Z in along the s ide of Edam"). These features indicate that the description in Num 34:3 depends on the text of Josh 15, lb (so already WAZANA 1998: 118-119).

T he two descript ions of the line in v. 4 - "south of the ascent of Akrabim" and "south of Kadesh-barnea" - arc exceptional , as the author of Numbers 34 sys tematically demarcated the boundary by combination of toponyms and verbal forms. The exception becomes clear when we unders tand th at Num 34:4 was copied from Jos ~1 15 :3 (WAZANA 1998: 11 5).

In addition to the southern and wes tern boundaries, which the author of Numbers 34 ~opied almost verbatim from Josh 15:lb-4, 12, he also adopted the int roductions to the four s ides of the land he delineated from the inheri tance of Judah. Compare 15 :2 (" and their southern boundary shall be") with 34:3 ("and your southern boundary shall be"); 15: 12 ("and the western boundary") with 34:6 ("and the western boundary") ; 15:5b ("and the boundary on the northern s ide") w ith 34:7 (" this shall be your northern boundary"); 15:5a ("and the eastern boundary") with 34:10 ("you shall mark out your eastern boundary").

The comparison between Ezekiel 47 and Numbers 34 is more complicated, because Ezekiel 's description depends on the system of Babylonian provinces, whereas Numbers avo ids all references to adjacent territo ries. However, there seems to be an indication that the no rthern boundary of Numbers is dependent on the text of Ezekiel. As sugges ted above, Ezekiel opens his description with th ree places located along the boundary (the way of Hcthlon, Lebo-hamath and Zcdad), and added two other places (Bcro thah and Sibraim), that arc located along this line. lie then proceeds to I-Iazcr-hattichon, which is on the border of Hauran. In the abbreviated repetition of the northern s ide (47:17) he marked Hazar-cnan at its eastern end. The autho r of Numbers 34 did not comprehend

1999] Lebo-llanwth, ~ubat-1 lamath, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 435

Ezekiel's description, and omitted Berothah and Hazcr-hattichon, while setting Ziphron (=Sibraim) in the wrong place, between Zedad and Ilazar-enan. The omission of toponyms (Karka) and the manipulation of names (Ilazar-addar in place of Hezron and Addar) arc also known from the reworking of Josh 15:4 in Num 34:3, and indicate the way that the author of Numbers 34 used his sources.

Another noteworthy fact is the lack of concrete knowledge of the northern boundary in Numbers 34. In place of Ezekiel 's "the way of Hcthlon" appears Mount Hor (h6r hiihiir), which is a general designation for a prominent mountain ridge (see Num 20: 22-27; 21 :4; 33:37-41; Dcut 32:50), not a proper name of a mountain. None of the verbs chosen to describe the northern boundary reflects any knowledge of the line ("you shall mark out", "shall be", "shall extend"), unlike the delineation of the southern and eas tern boundaries. All these characteristics indicate the secondary nature of the description of Canaan's northern boundary in Numbers 34.

The eastern border of the land in Ezekiel 47 is delineated on the basis of provinces, and d id not fit the description of Numbers 34. This is the only boundary fo r which the latter's sources arc unknown, nor do we know the location of S hepham and hliribhih "on the east s ide of Ain". Tentatively, I would suggest locating these toponyms on the road from Babylon to the province of Yehud, which passed from Damascus along the Yarmuk River to the Valley of Jczrccl. E ither the autho r of Numbers 34, or one of his acquaintances who had made the journey, was the sou rce for the two place names. In any event, the distance of about 250 kms. from Zcdad (~adad) and Hazar-enan (Qaryatcn1

) to the sea of Chinncreth is covered in Numbers 34 by two toponyms, indicating the au thor's poor knowledge of the area. Th is author was entirely dependent on his wrillen sources, and where sou rces were unavail able, he was unable to draw the boundary properly. All demarcati ons of the eastern boundary of Canaan on the bas is of Numbers 34 arc guesswork. The line had best be demarcated on the basis of Ezekiel 47 and the system of Babylonian provinces of his time.

7. Summat·y and Conclusions The delineat ion of the future Land of Israel in Ezekiel 47:13-23 is ori

g inal in both concept and all parts of the descript ion. The northward extension of the future land to incl ude the province of Damascus and the Phoenician coast up to Nahr el-Kcbir, and the d iv is ion of the territo ry west of the Jordan among the twelve tribes, have no parallel in biblical literature. It differs from the system of tribal allo tments in Joshua 13-19 in the extension of the northern boundary, the exclus ion of Transjordan from the allotments of the tribes, and the distribution of the wes t-Jo rdan ian land among the twelve tribes. There is no indication that the au thor of Ezekie l 47 was aware of the system of tribal allotment in Joshua 13-19, and he may never have read the second part of the book of Joshua.

The author of Numbers 34: J -15 wrote h is descrip tion on the basis of the

436 N. Na 'aman (UF 31

tribal allotments in Joshua 13-19, and the future Land of Israel in Ezekiel 47. Prom the tribal allotments he adopted the concept that Canaan is located west of the Jordan, that it is divided among the nine-and-a-half tribes, and that the other two-and-a-half tribes had sett led in Transjordan, outside of Canaan. lie copied all the details of the southern and western boundaries of Canaan, as well as the headlines of the four sides of the delineated land, from the description of Judah 's allotment (Josh 15:1-12). From Ezekiel he took the northward extension of the boundary and the delineat ion of the northern border. Only the description of the eastern boundary of Canaan is original, and possibly based on personal knowledge.

In a widely-cited article written in 1946, MAZAR (MAISLER) identified the northern boundary of Canaan as described in Numbers· 34 with that of the Egyptian province of Canaan in the 13th-12th centuries BCE, and many scholars accepted his suggestion 36

• Indeed, there is a close similarity between the line of the northern bord er of Late Bronze Canaan and the northern border of Canaan as demarcated in Nu m 34:7-9 (NA' AMAN 1994:411-413). Mazar suggested that Canaan was a fixed territorial-administrative concept, which the Israelites encountered when they occupied the land and used it in all the later generations. In light of the above discussion, thi s assumption cannot be sustained any longer. Another solution must be sought for the territorial continuity between the 13th-12th centuries BCE boundary of historical Canaan and the boundaries of biblical Canaan written by a Priestly author, possibly in the early post-exilic period.

I have already noted that the early biblical concept of the Land of Canaan appears in the tribal allotments, and that the northern border is demarcated there along the line of the southern slopes of Mount Hermon - Dan - the Li!ani River. As against Mazar's suggestion, the demarcation of Canaan in early bibl ical historiography indiqtcs a break in the concept of Canaan's northern borders between the Late Bronze and the late Iron Age.

Contrary to MAZAR, ELLIGER (1936:34-73) suggested that the northern boundary of the land delineated in Numbers 34 and Ezekiel 47 reflects the extent of David's conquests in Syri a, which is the furthest northern limit ever reached by a Is raeli te king. According to the account of David's wars with the Arameans (2 Sam 8:3-8), the Israelite king defeated I-Iadadezcr of Zobah, and conquered the kingdoms of Zobah and Damascus. The future Land of Israel described in Ezekiel 47:13-21 encompassed the province of Damascus and passed ncar the southern border of the province of ~ubat. Noteworthy is the mention of Berothai among the c ities that Dav id conquered from Hadadezer (2 Sam 8:8) and its appearance on the northern boundary of Ezekiel's visionary land (Ezek 47: 16). Regardless of the historicity of the account of David 's wars, there is a similarity between the northern limits of the territory conquered by David according to 2 Sam 8:3-8 and the northern boundary of the land delineated in Ezek 47:15-17

31' MAISLER (MAZA R) 1946:9 1- 102. Sec the li terature cited in note 32 above.

t999] Lebo-llamath, ~ubat- llamath, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 437

and Num 34:7-9 (as suggested by ELLIGER). The kingdom of ~ubat was annexed by a king of Damascus (possibly in the

mid-ninth century BCE; NJ\'1\MAN 1995:384-387) and became its northern province. The Assyrians conquered and annexed the kingdom of Damascus in 733/32 BCE. They separated the province of Damascus from that of ~ubat and organized them as two neighbouring provinces. In the time of Sargon II, the eastern parts of the kingdom of Hamath were annexed to ~ubat, while a new province, Man~uatc, was organized in Hamath 's western territory. The Assyrian system of provinces was adopted by the Babylonian and Persian empires. When Ezekiel described the future Land of Israel, he drew on the province system of his own time. I Ic included therein the province of Damascus, and left out of it the prov inces of Ilamath-Zobah and Hauran. The author of Numbers 34 took the territory outlined by Ezekiel, and in accordance with its function in the narratives of the wanderings, conquest and settlement, called it "the Land of Canaan". It is thus clear that the northern boundary of Late Bronze Canaan was transferred from one political-terri torial system to another, and that the boundary drawn by the author of Numbers 34 refl ects the system of provinces of his own time 37

.

We may conclude that there is no direct relationship between the borders of Late Bronze Age Canaan and the boundary system of Numbers 34, nor should we assume that a memory of the northern border of historical Canaan was carried on for so many centuries . MAZAR's observation of the similarity of the northern border is correct, but the similarity should be explained differently than suggested in his pioneering study.

Finally, a short note about the relat ion of the Priestly description of the Land of Canaan in Numbers 34 to other biblical texts. The problem of the antiquity of the Priestly source was recently the focus of a hot debate, and a growing number of scholars support KAUFMANN's thesis of a pre-exilic date for the composit ion of the P source. These scholars suggest that the P source antedated Deuteronomy, as well as the Book of Ezekiel 3x. My study of the relation of Numbers 34 vis r/ vis the tribal allotments in Joshua 13-19, on the one hand, and vis a vis Ezek iel 47, on the other hand, demonstrates its late date. It corroborates AULD's observations ( 1980:72-87) of the priority of Joshua over Numbers in the case of Num 33:50-35,8. The discussion of the relations of the P source to other biblical texts involves many clements, and no single text analysis can resolve such a complicated problem. Ilowever, it should be emphasized that at least in the case under discussion, the late date of P is evident as against the relatively early date of Joshua 13-19 and Ezekiel 47.

37 ELLIGER ( 1936:45-49) was able to demonstrate that the area of Lebo-hamath continued to function as a borderl ine in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods. 3

" KAU FM ANN 1937:113- 142. For the extensive literature written on the subject, see note 4 above.

438 N. N~ ' aman [UF 3 1

Bibliography

Aharoni , Y. 1967. The Lalld of the Bible: A 1/istorical Geography, Philadelphia. Ahituv, S. 1984. Callaallite Topollyms ill Allciellt Egyptiall Documents, Jerusalem. A It, A. 1945. Neue assyrischc Nachrichtcn iibcr Pa liis tina und Syrien, ZDPV 67: I 28- 159. Astour, M.C. 1963. Place-Names fro m the Kingdo m of Alala!} in the North Syrian List ofThutmose

Il l: A Study in Historical Geography, .INES 22: 220-24 1. 198 1. Ugar it and the Great Powers. Fifty Years of Ugarit and Ugaritic, in: G.D.

You ng (cd.), Ugarit ill Retrospect, Winona Lake: 3-29. 199 1. The Location of Hasurii of the Mari Texts, Maarav 7: 5 1-65. 1995. La topographic dt~ r~yaume d'Ougarit, in M. Yon, M. Sznycer et P. Bordrcui l

(cds.), Le pays d'Ougarit autour de 1200 Av. J .-C. Hisloire e/ archeologie (Ras Shamra-Ougarit I I), Paris: 55-7 1.

Auld, A.G. 1980. Joshua, Moses, alld the Land. Tetrateuch -Pentateuch -Hexa/euch in a Generation since 1938, Edinburgh.

Barthelemy, D. 1992. Critique textue/le de !'Ancien Testament. Tome 3. Ezechiel, Daniel et les 12 Prophetes (OBO 50/3), Fri bourg/Gottingcn.

Beck, P. 1996. l:forvat Qitmit Revisited via ' En l~azcva, Tel Aviv 23: 102-1 14. Blcnkinsopp, J. 1996. An Assessment of the Alleged Pre-Exilic Date of the Priestly Mate

rial in the Pentateuch, ZA W I 08: 495-5 18. Blum, E. 1997. Ocr ko mpositionc lle Knotcn am Ubcrgang von Josua zu Richter: Ein

Entflcchtungsvorschlag, in : M. Vcrvcnne/J. Lust (eds.), Deuteronomy and Deuteronomic Literature. Festschrift C. H. W. Breke/mans (BETL 133), Lcuvcn: 18 1-2 12.

Cohen, R./Yisrael, Y. 1995 . On the Road to Edom. Discoveries f rom 'Ell Hazeva (The Israel Museum

Cata logue No. 370), Jerusalem (Hebrew). 1996. T he Excavations at ' Ein Hazcva: Israe li te and Roman Tamar, Qadmolliot 29,

78-92 ' Hebrew); Cooke, G.A. 1936. The Book of Ezekiel (ICC), Edinburgh. Deller, K. 196 1. uiLUL = uiparri~u und u\arru, Orielltalia 30, 249-257. Dion, P.-E.I 997. Les Arameens {/ / 'age du fer: his toire politique et structures sociales

(Etudes Bibliqucs, nouvelle scric. No 34), Paris. Edcl, E. 1952. Zur his torischcn Geographic der Gcgend von Qadcs, ZA 50: 253-258. 1953. Die Stc lcn Amcnophis' II aus Ka rnak und Memphis, ZDPV 69: 97-176. Elliger, K. 1936. Die Nordg rcnzc des Reichcs Dav ids. PJb 32: 34-73. Eph'al, I. 197 1. URUSa-za-c-na = uRuSa-za-na, IEJ 2 1: 155- 157; 1982. The A llcient A rabs: Nomads Oil the Borders of the Fertile Crescellt, 9th-5th

Cellturies B. C., Jerusalcm/Leiden. Fa les, F. M./Postgate, J.N. 1992. Imperial Admillis trative Records, Part I Palace alld Temple Admillistratioll

(State Archives of Assyria 7), Helsinki . 1995. Imperial Admillistrative Records, Part II Provincial alld Military Admillistratioll

(State Archives of Assyria II ), Helsinki. Fohrcr, G. 1955. Ezec!tie/ (HAT, 1/13), T iibingen. Forrer, E. 1920. Die Pro vinzeilltei/ung des assyrischell Reiches, Leipzig.

1999] Lcbo-l lama til, ~uba t- llamat h , and tile notthcrn boundary of tile land od Canaan 439

Fuchs, A. 1994. 1998.

Die lnschriften Sarf?OilS II. aus Khorsabad, Gottingcn. Die Annalell des Jahres 711 v. Chr (State Archives of Assyria Studies 8) l lclsinki. '

Furr~r, K. 1885. Die antike Stiidtc und Ortschaften im Libanongcbictc, ZDPV 8: 16-41. Gardtncr, A. II. 1947. Allcient Egyptiall Ollomastica I, Oxford. Grayson, A.K.

1975. Assyrian and Babylonian Chrollicles (Texts from Cuneiform Sources 5), Locust Valley.

1996. A s5yrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC, II (858-745 BC) (RIMA 3), Toronto.

Hawkins, J.D. 1972-75. Hamath, RLA 4: 67-70. 1987-90. Man~uate, RLA 7: 342-343.

1995. The Pol itica l Geography of North Syria and South-East Anatolia in the NcoAssyrian Period, in: M. LI VERA NI (eel.), Neo-Assyrian Geography (Quadcrni eli Geografiia Storica 5), Rome: 87- 10 1.

I Ieick, W. 197 1. Die Beziehungen Agyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2 . .falzrtausend v. C/rr.(2nd rev. eel.), Wiesbadcn.

Honigmann, E. 1924. Historische Topographic von Nordsyrien im Altertum ZDPV 47· 1-64. ' .

llu rowi tz,_ V.A. 1992. I /la ve Built You an Exalted !louse. Temple Building in the B ible Ill L1ght of Mesopotamia11 and North111est Semitic Writi11gs (JSOTSup 115) Sheffield . '

Hutchens, K.D. 1993. Defi ning the Boundaries: A Cultic Interpretation of Numbers 34 1-_12 and Ezekicl47, 13-48. I , 28, in: M.P. Graham/W.P. Brown/J.K. Kuan (eels.): lftstory and Interpretation. Essays in llonor of John H. Hayes (JSOTSup 173) Sheffield: 2 15-230. '

Joanncs, : :/982. La loca lisation de ~u rru a I 'epoque Neo-Babylonicnne, Semitica 32: 35-

Kallai, Z.

1975. The Boundaries of Canaan and the Land of Israe l in the Bible, Eretz Israel 12: 27-34 (Hebrew).

1986. f-li~torical Geography of the Bible. Tire Tribal Territories of Israel, Jerusalem/ Let den.

Kaufmann, Y. 1937. The Religio11 of Israel from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile I, Jerusa lem (Hebrew).

Kitchen, K.A. 1982. Pharaoh Triumphant. The Life a11d Times of Ramesses 11, Warminster.

Klcngcl, H. 1969. G_esch ichte Syriens im 2. Jahrtause11d v.u.Z. Tcil 2. Mille/- und Siidsyriens Ber-

1979. li n. '

Geschichte Syrie11s im 2. Jahrtause11d v.u.Z ., Teil 3. Historische Geographie 1111d allgeme111e Darstellung, Berl in.

Kuschkc, A.

1954. Bcitriige zur Siedlungsgcschichte der Bikii ', ZDPV 70: 104-129. 1958. Beitriigc zur Sicdlungsgeschichte dcr Bikii', ZDPV 74: 8 1- 120. 1979. Das Terrain dcr Schlacht bci Qadcs un ci die Anmarschwege Ramscs' II. ZDPV

95: 7-35 '

Kuschke, ~./M i t tmann ,_ S.~M ii l ~c r, ,U .!Azouri, I. 1976. Archiiologisclrer Survey i11 der nordltschen B1qa (Bcthettc zum Tlibinger At las des Vordercn Orients, Reihe

440 N. N~'aman [UF 31

B, Nr. II), Wicsbadcn. Landsberger, B. 1948. Sam 'a/. Studien zur Entdeckung der Ruinenstaelle Karatepe,

Ankara. Lewy, J. J 944. The West Semitic Sun-God Hammu , HUCA 18: 429-481. Lipir1 ski, E. 197 1. The Assyr ian Campa ign to Man~uate, in 796 BC., and the Zaki r Stela,

A/ON 3 1: 393-399. Maislcr (MAZAR), B. 1946. Lebo Hamath and the Northern Boundary of Canaan,

Bulletin of the J e1vis/z Palestine Exploration Society 12: 91-102 (Hebrew) = B. Mazar, The Early Biblical Period, Jerusalem 1986: 189-202.

Malamat, A. 1963. Aspects of the roreign Policies of David and Solomon, JNES 22: 1-17.

Marfoe, L. 1994. Kii mid ei-L6z. 13. The Prehistoric and Early Historic Context of the Site, Catalog and Commentary. Revised, enlarged and prepared for publication by Rolf Hachmann and Christine Misamer, Bonn.

Mayer, W./Opific ius-Maycr, R. 1995. Ocr Schlacht bei Qaddi. Ocr Versuch eincr ncucn Rekonstruktion, UF 26: 32 1-368.

Milgram, J. 1999. T he Antiq uity of the Priest ly Source: A Reply to Joseph Blenkinsopp, ZA W l l I : 10-22.

Montgomery, J.A. 195 1. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Books of Kings (ICC), Edinburgh.

Na 'aman, N. 1986. Borders and Districts in Biblical Historiography (Jerusalem Biblical Studies

4),J e rusa I em. 1988. Biryawaza of Damascus and the Date of the Kiimid el-L6z 'Api ru Letters, UF

20: 179- 193. 1992. Canaanite Jerusalem and its Ce ntral Hill Country Neighbours in the Second Mil-

lennium B.C. E., UF 24: 275-29 1. 1994. The Canaanite and T heir Land : A Rejoinder, UF 26: 397-4 18. 1995. Hazacl of ' Amqi and Hadadczcr of Beth-rehob, UF 27: 38 1-394. 1999. On the Antiquity of the Regnal Years in the Book of Kings, TZ 55: 44-46. North, R. 1970-7!. Phoenie ian-Canaan Frontier Lebo' of Ham a, MUSJ 46: 71-103. Noth , M. 1935. Studlen zu den historisch-geographischcn Dokumenten des Josuabuches, ZDPV

58: J 85-255. 1937. Das Reich von I-Iamath als Grenznachbar des Reiches Israel, PJb 33, 36-51. Oded, B. 1964. Two Assyrian References to the Town of Qadesh on the Orontes, lEI 14:

272-273. Parpola, S. 1987. The Correspondence of Sargon 11, Part 1: Lellers from Assyria and the

West (State Archives of Assy ria 1), Helsinki. Ra iney, A.F. 197 1. A Front Line Report from Amurru, UF 3: 131-149. Rudolph, W. 1955. Chronikbiicher (HAT 1/2 1 ), Tiibingen. Saggs, H.W.F. 1955. The Nimrud Letters, 1952-Pa rt II, Iraq 17: 126- 154. 1963. The N imrud Letters, 1952-Part VI, Iraq 25: 70-80. S imons, J. 1959. The Geographical and Topographical Texts of the Old Testament . Lei

den. Smcnd, R. 197 1. Das Gesetz und die Volker. Ein Bei trag zur deuteronomistischen Redaktions

geschichte, in: H.W. Wolff (cd.), Probleme biblischer Theologie, Gerhard von Rad zum 70. Geburtstag, Miinchen: 494-509

1999) Lebo- Hamalh, ~ubat- llamalh, and the northern boundary of the land od Canaan 441

1983. Das uneroberte Land, in: G. Strecker (eel.), Das Land Israel in biblischer Zeit, Gott ingen: 9 1- 102.

Tadmor, I I. 1958. The Campaigns of Sargon II of Assur: A C hronological-Historical Study, JCS

12: 22-40, 77- JOO. 1994. The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser 1/1, King of Assyria, Jerusalem. Van Scters, J. 1997. Solomon's Temple: Fact and Ideology in Biblical and Near Eastern

l lis toriography, CBQ 59: 45-57. DeVaux, R. 1968. Le Pays de Canaan, JAGS 88: 23-30. 1978. The Early History of Israel. From the Beginning to the Exodus and the

Covenant of Sinai, London. Watanabe, K. 1991 . Review of Simo Parpo la, The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part I,

Letters from Assyria and the West, Helsinki University Press 1987, BiOr 48: 183-202.

Wazana, N. 1996. Biblical B order Descriptions in Light of Ancient Near Eastem Literature (unpublished Ph.D. dissertat ion), Hebrew University of Jerusa lem (Hebrew).

Weinfeld, M. 1983. The Extent of the Promised Land -The Status of Transjordan, in : G. Strecker (eel.), Das Land Israel in Biblische Zeit, Gottingen: 59-75.

Weippert, M. 1972. Review of S. Parpola, Neo-Assyrian Toponyms, Neukirchen-Vluyn 1970,

GGA 224: 150- 161. 1973A. Menahem von Israel und seine Zeitgenossen in einer Steleninschrift des assyri

schen Ko nigs Tiglathpi leser Ill. aus dem Iran, ZDPV 89: 26-53 . 19738. Die Kiimpfe des assyrischen Konigs Assurban ipal gegen die Araber: Redaktions

kritische Untersuchung des Berichts in Prisma A, WdO 7: 39-85. 1992. D ie FeltlzLige Adadniraris Ill. nach Syrien: Voraussetzungen, Verlauf, Folgen,

ZDPV I 08: 42-67. Will i, T. 1972. Die Clzronik a/s Auslegung. Untersuchungen zur literarischen Gestaltung

der historischen Uberlieferung Jsraels (FRLANT I 06), Gottingen. Zadok, R. 1977. Historical and Onomastic Notes, WdO 9: 35-56. Zimmerli, W. 1983. Ezekiel 2. A Commentary on the Book of the Prophet Ezekiel

chapters 25-48 (Hermeneia), Phi ladelphia.