Kuy Alterities: The Struggle to Conceptualize and Claim Indigenous Land Rights in Neoliberal...

Transcript of Kuy Alterities: The Struggle to Conceptualize and Claim Indigenous Land Rights in Neoliberal...

Kuy alterities: The struggle to conceptualise and claimIndigenous land rights in neoliberal Cambodia

Neal B. KeatingDepartment of Anthropology, College at Brockport, SUNY, 350 New Campus Drive, Brockport, NY 14420, USA.

Email: [email protected]

Abstract: Based primarily on fieldwork with Kuy peoples in Rovieng District, Preah Vihear Province,this article examines contemporary Indigeneity in Cambodia as an emergent heterogeneous andpolythetic identity vis-à-vis the changing nature of the state, and suggests that a more substantivepolitical engagement with Indigenous identity and history offers a pluricultural reframing of the worldheritage of Cambodia and a possible source of alternative land regimes that are more sustainable andequitable than the current dominant neoliberal model of land concessions. Although the 2001Cambodian National Land Law holds critical significance for Indigenous Peoples in pursuit ofcommunal land rights, it has largely failed to protect rights because of (i) persistent discriminationagainst groups now claiming Indigenous identities, embedded in state procedures of Indigenousidentity and land registration; and (ii) the state’s demonstrated embrace of land concession regimesas the preferred strategy of economic development. The Delcom mining concession of Kuy landsprovides one example of the destructive impacts of this strategy. An examination of the evidence ofKuy peoples’ history suggests that their classification as ethnic minorities is of recent origins, and thatin the past they played more active roles in Cambodian state-building projects.

Keywords: Cambodia, human rights, Indigeneity, Kuy peoples, land concessions

Introduction

In May 2007 I started fieldwork at the UnitedNations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues(UNPFII), to better understand the social actors,culture and political ecology of this transna-tional human rights arena, and how (and why)anthropological practice might contribute to thetheory and practice of Indigenous rights. TheUN adoption of the Declaration on the Rightsof Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, adopted 13September 2007) represents a significant con-solidation of international human rights law byextending basic rights to groups previouslydenied them on account of their cultural differ-ences from dominant groups and states. Thequestion since 2007 is: Can Indigenous rightsactually be implemented in the world, and ifso how, where, and when? One area whereanthropology may significantly contribute is

through multi-sited ethnographic analyses ofthe actual status and conditions of these rightsin Indigenous communities and territories,which are grounded in local communities, aswell as the transnational and national platformswhere rights talk happens. In collaboration withtwo Indigenous organisations from Cambodia, Ibegan a new project in 2010, focused on thesituation of Indigenous rights in three Kuy vil-lages located in Rovieng District, Preah VihearProvince, and carried out 11 weeks of fieldworkin Cambodia during 2010 and 2011. Primarydata include approximately 60 interviews andunstructured dialogues with Kuy adult femaleand male villagers, combined with field obser-vations and use of secondary sources. Whiledata analysis is ongoing, the present articleseeks to describe and analyse the situation inRovieng, with regard to Kuy Indigenous identity,land rights and rights to self-determination.

bs_bs_banner

Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 54, No. 3, December 2013ISSN 1360-7456, pp309–322

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd doi: 10.1111/apv.12026

Indigeneity in Cambodia

Although the Cambodian state (the Royal Gov-ernment of Cambodia – RGC) legally recog-nised the collective existence and land rights ofIndigenous peoples in 2001, and establishedlaws, divisions and directives within the govern-ment that are prima facie designed to imple-ment these rights, the realisation of these rightsin the lives of most Indigenous peoples through-out the country remains largely non-existent.Land insecurity is a national problem in Cam-bodia, caused by the RGC’s de facto denial ofland rights protection and promotion, andaffecting possibly millions of Cambodian citi-zens. But it is particularly acute for Cambodia’sIndigenous peoples, because not only does landinsecurity put individuals and their families atrisk of displacement and poverty, it also threat-ens the existence of their collective sociocul-tural identities and practices, which are tied tosustainable patterns of land tenure in particularplaces that developed over long periods of time.For most of the Kuy people I interviewed for thisstudy, the loss of their lands does not just limitaccess to resources, but also destroys spiritforests, burial forests and distinctive ways ofliving, speaking and being human, along withtheir children’s futures. Through its actions overthe last decade, the RGC has demonstrated itspreferences for seizing Indigenous lands, terri-tories and resources in the name of economicdevelopment. Clearly, the RGC’s lack of politi-cal will is a significant obstacle to the realisationof Indigenous rights in Cambodia.

Yet there is another obstacle to Indigenousland rights: the concept of Indigeneity, as a legalrights-bearing collective identity or subjectivity,is as locally contested in Rovieng as it is at thenational and transnational scales. Even amongthe targeted populations that are the bearers ofIndigenous rights, there is not a clear consensuson what it means to be Indigenous. Although allthe villagers I spoke with self-identified as Kuy –a collective cultural identity that has long beenfitted into the savage slot of ‘otherness’ bysucceeding Cambodian states – few of themassociate this collective identity with self-determination rights, and most consideredthemselves at the mercy of the Khmer-dominated state. Indeed there is little presencein the local environment of any promotion or

protection of collective rights. Indigeneity is anew human rights framework that, like otherinternational human rights, is constructed at thetransnational scale and has to be locally trans-planted and translated if it is to achieve socialtransformative effects (see Merry, 2006).

Contemporary Indigenous peoples in Cambo-dia include approximately 20–24 different lin-guistic groups located mainly in the uplandforests, plains and mountains of the northernand northeastern provinces of Cambodia, andconstituting perhaps 500–600 village commu-nities. Census data are unreliable, but variousestimates of the Indigenous population totalsrange from 200 000 to 400 000, of which10–20% are Kuy (Mann and Markowski, 2005;Erni and Nilsson, 2008; see also demographicdiscussions in Baird, 2013; and Swift, 2013).Prior to the late 1990s, these groups were morecommonly referred to as ethnic minorities, hilltribes, Khmer Loeu and other diminutive names.Overall, Indigenous peoples make up a smallpercentage (1–2%) of the Cambodian nationalpopulation of approximately 15 million.

The stereotypical markers of Indigenous iden-tity in Cambodia involve linguistic, ethnic, eco-nomic, religious and other expressive elementsthat differ from dominant Khmer identity norms,as well as those of several other ethnic groups inCambodia (e.g. Cham, Chinese, Kinh). Thesesignify Indigenous peoples as semi-nomadicanimists living in the forests and mountains,practising economies of shifting cultivation andhunting and gathering, and generally lacking inthe social graces, language and modernist sen-sibilities of lowland civilisation. In the north-eastern provinces of Ratanakiri and Mondolkiri,Indigenous communities persist that to a degreeconform to the stereotypes of shifting cultivatorsreliant on biodiverse forests for hunting andgathering, with no fluency in Khmer. But for theKuy in Preah Vihear, a different situation holds.Historically situated on the west side of theMekong river, the Kuy have long been in closerproximity to Khmer lowland societies thantheir Indigenous counterparts further east, andhistorically more integrated into lowlandsocio-economic systems, with the result beingconsiderable cultural overlays with Khmerculture (Swift, 2013). While continuing to expe-rience discrimination by Khmers, I observedthat Kuy peoples in Rovieng live in Khmer-style

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd310

houses and villages, speak Khmer more oftenthan Kuy, do not dress in distinctively Kuyfashion, engage in wet rice farming, refer tothemselves as Buddhists rather than somethingelse, and the village authorities are selected bystate authority rather than through local kinshipsensibilities. Although one of the villages Ivisited was in the same place where Kuy peoplehad been living for possibly over a thousandyears, the locations of the other two villages Ivisited were determined by the Khmer Rouge,which relocated Kuy people there during the1970s and 1980s in order to better controlthem. Yet while their outward expressions ofcollectivity and cultural distinctness are imbri-cated with the dominant Khmer culture, the Kuyare not entirely assimilated. They recognise theircollective priority in time here, recall their his-torical experience of domination and ongoingdiscrimination, and are culturally invested inmaintaining their forest territories, most notablyPrey Lang, the last big area of primary forest inCambodia (A. Michaud, unpublished data). It ison these grounds they engage Indigeneity.

Global and regional contestationof Indigeneity

Despite the adoption of the UNDRIP and theinternational mainstreaming of Indigenous ter-minology, the concept of Indigenous Peoples aspeoples continues to be contested by statesglobally. Indigenous rights are a significantextension of the international human rightsprotection system that has been developingfor more than 60 years (Stavenhagen, 2008).Indigeneity goes beyond the identification asdefined ethnic minority segments of thenational population, by claiming inter alia basiccollective political, economic and land rightsbased on cultural difference (Erni, 2008; AIPPet al., 2011). Indigenous rights implies astructural reforming of state power alongpluricultural lines, in which power is shared andnegotiated between states and self-determiningcollectives, and aimed at achieving mutualconsent regarding decisions that impact Indig-enous peoples’ lands, territories and resources.How such a model is possible within currentneoliberal states remains to be seen, especiallyin societies with a long history of discriminatingagainst the groups now asserting Indigenous

identities. Perhaps more surprising is thatIndigeneity is imaginable at all in the currentglobal ecumene of market-driven hegemony,and that it has gained global traction andbecome possible to imagine in a place likeCambodia, where the modern history of humanrights has been tragic (Chandler, 1993; Brinkley,2011).

Is Indigeneity a new form of sub-state collec-tivity that, like ethnonationalism, may threatenthe national unity and territorial integrity ofstates? Or is it an understandable responseby disenfranchised groups to increasing state-corporate capture of their resources? Manystates and some academics argue that Indig-enous rights, especially Indigenous land rights,are either dangerous or misguided ideas thatif encouraged may foment ethnic violencebetween different groups on the basis of ‘bloodand soil’ types of claims. Kuper argues that thejustification for Indigenous land claims ‘. . . relyon obsolete anthropological notions and ona romantic and false ethnographic vision. Fos-tering essentialist ideologies of culture andidentity, they may have dangerous political con-sequences’ (Kuper, 2004: 266). Béteille claimsthat anthropologists who support the idea ofIndigenous people do so because they enjoy the‘. . . state of moral excitation’ that it supposedlyelicits, and not because the idea may help solvepractical problems (Béteille, 1998: 191). Suchcritiques of Indigeneity resonate with the officialpositions of many Asian states that reject theidea of Indigenous peoples as valid in theircountries. The battle over the concept is signifi-cantly shaped by ontological differences regard-ing the nature of collective identities other thanstates, a battle that is itself very cultural. State-based arguments tend to favour a monotheticmodel of identity that emphasises citizenry asrelatively atomised individuals, with equalrights for all, and no special rights for anyparticular groups. They see Indigeneity as a dis-cursive invention that threatens the state. Coun-tering this are views arguing that Indigenousidentity (if not all social identity) is a polytheticand heterogeneous process, and not reducibleto any single commonality, but involves acluster of multiple variables shared by membersof certain groups that demonstrate emergentpatterning over time in response to comparablehistorical conditions of domination (Saugestad,

Indigenous land rights in Cambodia

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 311

2004; Levi and Maybury-Lewis, 2012). Indi-geneity may escape monothetic definition andfrustrate those who want a universally consist-ent human subject, but it is nonetheless aviable concept within international law, whereIndigeneous identity is seen as generated byvariable combinations of the following fouraspects: priority in time with regard to specificplaces, voluntary perpetuation of cultural dis-tinctiveness, self-identification and recognitionas a distinct collectivity, and the collectiveexperience of colonial and neocolonial oppres-sion (Saugestad, 2004). If we theorise Indi-geneity along the lines suggested by TaniaLi – as variable articulations of social and terri-torial identity, a creative construction or cut ofpositionality out of a social field of multiplepossibilities rendered by the contingencies ofhistory, power and culture – can we not apply asimilar processual understanding to the conceptof the state, if not all collective identities, i.e.that they are constructed, contingent, andsubject to change, paradox and contradiction(Li, 2000; Trouillot, 2001)? In this light, theconcept of Indigenous peoples represents some-thing bigger than just the peoples themselves;it signals new political articulations of culturaldifference that have implications for other emer-gent social movements and community forma-tions in the neoliberal era (Turner, 1997). To saythat Indigenous identity is not a defined stasisbut an ongoing process of becoming, is not anirresponsible statement driven by a need forpostmodern moral excitement, but an empiricalobservation of the social factuality of a growingtransnational collective rights movement, whichclearly demonstrates not only great heterogene-ity but also a patterned polythetic unity. Thismovement found traction in Cambodia at theturn of the twenty-first century, and has gradu-ally increased since. Swift’s account andanalysis of the emergence of Kuy Indigeneitydemonstrates clearly how the uptake of both‘Kuy’ and ‘Indigenous’ identities involves pro-cesses of shifting articulation, along the linesargued by Li (Li, 2000; Swift, 2013).

Indigeneous rights talk may be a recentimport into mainland Southeast Asia, but itstransnational origins do not fully explain itslocal uptake. Indigeneity resonates variablywith a long history of complex ethnic and politi-cal diversity in the region. Recent attempts to

relate this past to contemporary expressions ofIndigeneity in the region range from Scott’s(2009) paradigm of ‘Zomia’ in which the South-east Asia highlands are interpreted as autono-mous ‘stateless’ zones constructed by theforebears of today’s Indigenous peoples as partof a general strategy of avoiding the oppressionof lowland state practices, to more ethno-graphic and historically grounded approachesthat foreground ongoing and shifting politicalnegotiations between and among highland andlowland peoples (Jonsson, 2010, 2012). Myown ethnographic and historical research withKuy Indigeneity suggests that Kuy peoples haveat times chosen to go into the highlands toevade state capture through enslavement, butthat at other times lived lives that were variablyintegrated with the lowland states of Chenla,Angkor, the French Protectorate, and in a veryambiguous way even with the Democratic Kam-puchea (DK) state of Pol Pot, which looked tohighland peoples as moral exemplars (‘oldpeople’) for the new society. I have found evi-dence (discussed below) suggesting that in thepast Kuy peoples may have played integral rolesin Cambodian lowland state formation, as ironmakers, elephant hunters, tribute payers andtemple builders. As Jonsson (2012) points out,the risks of reading highlander pasts as narra-tives of freedom-seeking stateless peoples are toobscure the more complex relations that havedeveloped between highlanders and lowlandersover time, and to reproduce a stereotyped frameof Indigenousness that forecloses on the possi-bility of its contemporary salience. What goeson at the UNPFII is not a movement to evade thestate, but rather to leverage better integrationwithin states that improves the prospects forpeoples’ basic human rights.

Human rights and the savage slot

The subhuman treatment of those groups ofpeople now claiming Indigenous identity has along history in Cambodia. The human rightsnorm of non-discrimination runs into an olderset of ‘traditional’ Cambodian claims abouthumans, nature and social order, based onpolitico-religious principles of hierarchy andtransmigratory merit. These include notions ofinequality as the outcome of natural andsupernatural processes; where social order,

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd312

peace and stability is achieved only through theconstruction and operation of highly verticalsystems of rank, power and privilege, charac-terised by extensive patron/client relations,and enforced through disproportionate vio-lence (Hinton, 1998; Chandler, 2008b). Thistraditional political cosmology of ‘HomoHierarchicus’ (Dumont, 1981) re-appears inCambodia today, where power is articulated viaopaque but ubiquitous neoliberal patronagenetworks that extend throughout the countryfrom national to local scales. While a growingnumber of analyses find that the contemporaryRGC is developing as a kleptocratic process ofstate capture of natural resources (e.g. GlobalWitness, 2007, 2009; Keating, 2012), some seethis as historically and culturally recursive, withstructural resemblance to previous Khmer socialorders based on inequality that rose and fell inCambodia during the last 1200 years (Brinkley,2011). While new global markets have alteredthe scope and scale of power in Cambodia,they appear to have not significantly alteredthis cultural basis of Cambodian tradition, butrather given it new expression via global marketintegration.

Indigenous rights conflict with these norms oforder, precisely because upland Indigenouslivelihoods and identities are symbolically asso-ciated with the forest, wildness, chaos and dis-order (Hansen and Ledgerwood, 2008). Theidea of Indigenous peoples constituting politi-cally organised and legally recognisable collec-tive groups contradicts cultural notions aboutthe forest as a place outside of the reach oforder, and the people living there as outsidesociety and therefore subhuman. Well into theFrench colonial period, the practice of slavery inCambodia was normative, and uplanders likethe Kuy were commonly caught, bought andsold as slaves, locally and to lowland Thaisand Khmers in Cambodia (Harmand, 1876;Seidenfaden, 1952; Chandler, 2008a). Thebinary discrimination between savage and civi-lised is not exclusive to Western coloniserculture, but also present in Asia where it has anequally long, if not longer, history. For example,while visiting Angkor during A.D. 1296–1297,the Chinese chronicler Chou Ta-Kuan recordedthat ‘Wild men from the hills can be bought toserve as slaves . . . These savages are capturedin the wild mountainous regions, and are of a

wholly separate race called Chuang. . .’. Chouexplained further that when Chuang ‘. . . arebrought into town as slaves they are lookeddown on by everyone else, so much so that inthe course of an argument, if . . . a Cambodianis called Chuang by his adversary, dark hatredstrikes to the marrow of his bones’ (Chou, 1993:21).

This pejorative perception of Indigenouspeoples as subhuman wild savages continues inmainstream Cambodian culture during thetwenty-first century. For example, during adebate in the Cambodian National Assembly on14 November 2012, CPP lawmaker VunChheang called one of his political adversariesa Bunong, which apparently so incensed hisadversary (Sokha Kim, president of the HumanRights Party) that Sokha and 20 other lawmakersstormed out of the meeting in protest (Eang,2012). Although Bunong is the name of one ofthe larger groups of Cambodian Indigenouspeoples, in this context Bunong carried thesame meaning as Chuang – savage, uncivilised,backward. Despite the existence of an organ-ised Indigenous rights movement in Cambodiain which modern educated Bunong peopleserve as leaders, the continuing use of the termas a name for savagery speaks to the ongoingdiscrimination and dehumanisation that Indig-enous peoples in Cambodia have long experi-enced. Even if the concept and fulfilment ofhuman rights in general becomes more activelypromoted and protected by the Cambodianstate, Indigenous rights face the additional cul-tural barrier of this Asian-style ‘savage slot’(Trouillot, 1991).

Cambodian land law and land concessions

Despite such traditions, the RGC adopted a newland law in 2001 that is the first piece of statelegislation in mainland Southeast Asia to for-mally recognise Indigenous peoples’ collectiverights to communally held lands: the NationalLand Law (Royal Government of Cambodia,2001; Baird, 2011, 2013). Yet even containedwithin this law that gives a legal basis toIndigeneity in Cambodia are the grounds for itsnegation via other clauses, namely those recog-nising the state’s right to make land conces-sions. Concessions were well under way duringthe 1990s, but they significantly increased after

Indigenous land rights in Cambodia

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 313

adoption of the 2001 Land Law. One of theoft-stated objectives of the Indigenous rightsmovement in Cambodia is to leverage stateimplementation of the Land Law, but in practicethe state is already implementing it – albeit withpriority given to land concessions.

During the DK revolution of 1975–1979,most or all previous property ownershipregimes were destroyed. The 2001 Land Lawwas to remedy this, by providing land securityto both the civilian population as well as toforeign investors. But the Land Law also made aclean sweep of all past claims to land, statingthat ‘any regime of ownership of immovableproperty prior to 1979 shall not be recognized’(RGC, 2001: Art. 7). Without explicitly saying it,this rule effectively invalidated the Indigenousland tenure systems of the uplands that existedpre-Khmer Rouge. Instead, the Land Law pro-vides definitions of different categories of landownership, including public, private and collec-tive ownership. But each of these categories hassubcategories of ownership, which in somecases complicate and blur the boundariesbetween the categories themselves.

For example, in articulating public ownershipof land as state property, Article 14 stipulatesthat the state may own the land as either publicor private property. This distinction is key tounderstanding the legal logic behind land con-cessions contained in Articles 48–61. Article 58stipulates that only private property of the statemay be granted as land concessions. Publicstate property cannot. However, should thestate reclassify state-owned public property asstate-owned private property, it becomes legallypossible for the state to grant away formerlyprotected lands as land concessions to the cor-porate sector.

One example is Boeng Peae Wilderness Sanc-tuary, a public state-owned ‘protected area’ justsouth of the villages I visited. Boeng Peae is (orwas) a large biodiverse forested area, and part oftraditional Kuy territory. During the 2000s, thegovernment reclassified portions of Boeng Peaeas state private property, and as of 2011 hadgranted 10 land concessions in Boeng Peae toseveral companies, for more than 40% of the242 500 ha area (Vrieze and Kuch, 2012). Con-cessionaires moved into the area, logged it andreplaced it with agroindustrial plantations ofexport crops, especially rubber. Environmental-

ists familiar with Boeng Peae are of the opinionthat the concept of wilderness sanctuary nolonger applies there.

In addition, the Land Law does not apply to allland concessions, but only those grantedas ‘economic’ land concessions (ELCs) foragroindustrial or social development purposes.Article 50 stipulates that ‘There may be severalother kinds of concessions, such as mining con-cessions, . . . industrial development conces-sions, . . . [that] do not fall within the scope ofthe provisions of this law’. Mining concessions(MCs) are made through the Ministry of Industry,Mining, and Energy (MIME), which appears togrant such concessions in two phases: Memo-randum of Understandings for exploration, andthen licences for exploitation. If the processesby which ELCs are made are concealed, theprocesses by which MCs and other land conces-sions are made are even more opaque. Theseland deals can be as big or bigger than ELCs.In the case of Rovieng District, as well as neigh-bouring districts like Chey Saen, mining conces-sions now enclose most of the area.

Land concessions as land grabs

In making these deals, the RGC follows a globalpattern of behaviour, what some regard as a‘regressive’ kind of land reform – in which thestate seizes large areas of land from poor peopleand grants them to rich people through non-transparent exchange processes. It is regressivein the sense that it resembles more the old prac-tices of colonialism and modernisation than anew strategy of reducing poverty and insecurity.Although ‘land-grabbing’ is not a new practice,in recent years it has greatly intensified in manycountries around the world in terms of its exten-sion, scale, speed and violence (White et al.,2012). In recent years, an estimated 43–227million ha of the planet’s surface (World Bank v.Oxfam figures) has been enclosed by landgrabs, much of it concentrated in Southeast Asiaand sub-Saharan Africa (White et al., 2012).These big land deals are often shrouded insecrecy, and affected populations are neitherconsulted nor adequately compensated, andinstead are usually evicted. Protest is typicallymet with state violence (Cambodia HumanRights Action Committee, 2008, 2009, 2010;Subedi, 2012). There are an increasing number

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd314

of stories in global circulation about the state’sresponse to protestors (e.g. Chut Vutty’s assassi-nation, the Boeng Kak evictions and MamSonando’s arrest). There are many more likethem that have gone under-reported, eithersilenced altogether or confined within variousnon-governmental organisations (NGO) reportsthat go largely unread. During my fieldwork, Iheard multiple accounts from Kuy villagersliving in the vicinity of the Delcom MC inRovieng, about people getting beaten, stoned,shot at, evicted, arrested and killed by Delcomsecurity guards, all because they were tryingto access lands that had formerly been theirs.Reasonable estimates of the Cambodian popu-lation directly displaced by land grabbing rangefrom 400 000 to upwards of 1 million people(Keating, 2012). By early 2012, it was estimatedthat over 22% of the country’s surface area(about 4 million ha out of a total of 17.6 millionha) has been transferred to corporations asvarious kinds of land concessions, with much ofit in the uplands where Indigenous territoriesare located (Vrieze and Kuch, 2012).

Mining land grabs in Rovieng district

The Delcom corporation is an opaque miningcompany that obtained its first MC in Roviengsometime during 1994–1996, for the com-mercial exploration and development ofgoldmining. At a reported 16 200 ha (over62 sq miles), it enclosed an entire mountainwhere Kuy peoples had long practised small-scale artisanal mining of gold and iron, as wellas for grazing oxen, hunting, foraging and spir-itual ceremonies. Local Kuys attribute spiritualsignificance to the area as a place where pow-erful Ahret and Neak ta spirits dwell. Sometimebetween 2004 and 2009, the Delcom companyphysically enclosed the concession area, anderected fences, gates and walls around theperimeter, and brought in security forces (said tobe ‘on loan’ from the Royal Cambodian ArmedForces) to police the area surrounding the con-cession. Delcom began to actively ‘explore’their concession in 2004, which involveddigging three very large holes of about 100’deep and 50’ across, and then digging manyadditional smaller holes in between. Workersare then lowered into these holes to look forgold. Several Kuy men told me of their experi-

ences working for Delcom in these holes; theydid not like the conditions. They were afraid ofgetting buried alive. All of them quit within lessthan a year. The Delcom MC was followed byother ‘anonymous powerful businessmen’ (neakmean oum nach) who moved into the area andclaimed their own MCs, and similarly employparamilitary police to evict any would-be Kuyartesans. Since 2009, the state has granted moreELCs and MCs in the Rovieng area. The Kuyvillages situated in Rovieng are now literallysurrounded by corporate concessions of theirterritories. None of the affected Kuy communi-ties were consulted in any of these deals. Therewas no free, prior and informed consent givenby these communities. There is no indicationthat either social or environmental impactassessments were made, or that any compensa-tion was offered to the affected communities.

The Delcom MC land drains south into theStung Sen river system and the Boeng Peae Wil-derness preservation area. The Kuy villages Ivisited in Rovieng are small hamlets located inthe area between the mountains and theremaining forests of Boeng Peae. Although thereis great poverty here, most of the people I inter-viewed expressed a general satisfaction withtheir lifestyle, which involves a diverse andintense engagement with the land and forests inthe area. More than half of the people I inter-viewed equated land with life. For them theright to land is at the core of their dignity, integ-rity and worth as human beings.

As of 2011, the mining operations at theDelcom concession remained in the explora-tory phase, which means that extraction hasbeen relatively modest. Nevertheless, it is on alarger scale than Kuy artesian mining, andbelieved to involve unregulated use of toxicchemicals (like mercury) that drain downstreaminto Kuy communities’ groundwater. Some Kuypeople associate a recent increase in childillness with the new presence of these toxins inthe local environment. In 2011 the companyreportedly applied to MIME for a licence tocommence extraction and processing in theconcession in the 62-square mile area. Onceunder way, it is expected to produce greateramounts of tailings and waste that will signifi-cantly degrade the environment of all the Kuyvillages I visited, as well as what is left of theBoeng Peae ‘sanctuary’. And as of 2013, mining

Indigenous land rights in Cambodia

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 315

interests in the extraction of iron ore appear tobe growing at an even larger scale than gold.

Delcom, whatever/whoever that was (at dif-ferent times listed as a Cambodian, Malaysianand/or Chinese company), was just the begin-ning of what seems to be a much more exten-sive mining development that threatens an areaextending well beyond Rovieng. A new corpo-rate group has formed that may include Delcomalong with other companies in the area, namedthe Cambodia Iron and Steel Mining IndustryGroup (CISMIG). Media reports from earlyJanuary 2013 describe a corporate agreementbetween CISMIG and the China Zhongtie MajorBridge Engineering Group Co., Ltd. (MBEC) foran estimated US$11 billion developmentproject to develop much of Rovieng and CheySaen Districts into an industrial iron mining andsteel manufacturing zone, as well as build anew railway line to carry the finished productsfrom there to a new Koh Kong shipping port. Ifcarried through, this will be the biggest devel-opment project in the modern history of Cam-bodia (Equitable Cambodia, 2013; Kunmakara,2013). It is reported that CISMIG holds explo-ration rights to about 2400 sq km of land, whichis almost as big as the two districts combined,and must incorporate a number of prior MCs,including Delcom. What compounds the poten-tial impacts of the CISMIG/MBEC deal is that inaddition to mining expansion, much of thelands around the MCs have been granted awayas ELCs for industrial agriculture, especiallyrubber. In granting these ELCs and MCs, thestate is in fact implementing the 2001 Land Law,or at least part of it. Should CISMIG happen,many activists see it as ‘game over’ for the Kuyand the surrounding Prey Lang forest areas. Ifthis is what the Land Law has made possible,why then do Indigenous activists maintain thatthe problem is the government and not enforc-ing the laws it has made? Part of the reason isthat the Land Law contains other provisions rec-ognising Indigenous land rights that serve tomake the concept of Indigenous rights imagina-ble, even if practically unattainable.

Indigenous land rights and the Land Law

The Land Law includes a significant legalbasis for communal land titling (Articles 23–28). It stipulates two categories of collective

ownership of land: Buddhist monasteries andIndigenous communities. Unlike monasteries,Indigenous communities are first required toprove a legal status in order to secure commu-nal land title. Yet at the same time it recognisesIndigenous peoples and lands, it also affirmsserious constraints, limits and negations of theirexistence.

For example, Article 27 states that:

For the purposes of facilitating the cultural,economic and social evolution of members ofIndigenous communities and in order to allowsuch members to freely leave the group or tobe relieved from its constraints, the right ofindividual ownership of an adequate share ofland used by the community may be trans-ferred to them. [emphasis added]

By including private individual land ownershipas an option, the Land Law already provides away out of any communal land regime, whichin comparison with the rules regarding collec-tive ownership of Buddhist monasteries, seemshighly contingent. Monasteries remain in perpe-tuity, but Indigenous communities will eventu-ally disappear, in both cases aided by the state.The use of the term ‘evolution’ in the Land Lawsuggests that the state views Indigenous peopleswithin a unilinear frame of cultural evolution,where they occupy the savage slot. They are stillChuang.

The discursive constraints on Indigeneity inthe Land Law are evident in the subsequentprocedures established by the state and NGOssince 2009, to create Indigenous communalland titles. These entail a registration process inwhich a community must first apply for Indig-enous identity, followed by an application forcommunal land title. Although the processlegally happens through state agencies, it islargely the support of NGOs that enables it. Atthe local political level there is significant, ifnot convenient, confusion regarding Indig-enous registration and what it means. In thefirst step, the identity application is made to theMinistry of Rural Development (MRD). Yetbefore it can be submitted to the MRD it mustreceive prior approval by the local CommuneCouncil. According to my sources, the maincriteria for proving Indigenous identity includethe following:

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd316

1 Evidence of traditional livelihood – e.g.,ongoing practice of shifting cultivation, andgathering and harvesting non-timber forestproducts

2 Evidence of Indigenous language usage3 Evidence of Indigenous culture/custom, such

as music or dance4 Evidence of Indigenous religion/belief, such

as spirit forest ceremonies5 Evidence of Indigenous dressBesides its reductive essentialism, the MRDidentity registration process contradicts theUNDRIP, especially Article 33, which affirmsIndigenous Peoples’ right to determine theirown identities. In Cambodia, it is the state –with support from the NGO sector – whodecides who is and who is not Indigenous.

Many Kuy peoples are not able to meetthese criteria because of their ongoing‘Khmerization,’ which has been commentedupon by observers since at least the late nine-teenth century (Harmand, 1876; Swift, 2013).But even if these communities were able toperform the state’s criteria, their application foridentity registration might not reach the MRDbecause the local Commune Council can rejectit beforehand, for reasons that may have little todo with notions of authentic culture. Communechiefs fear that Indigenous recognition willresult in the loss of local governmental access tolucrative natural resources.

Presuming a community manages to get theirapplication past the Commune Council andreceives approval of their collective identityfrom the MRD, it must then submit anotherapplication for land registration to the Ministryof Interior (MI), which must also be pre-approved by the local Commune Council.Another significant limitation of this process isthe amount and types of land the state is notwilling to recognise in a communal land title,especially forests and fallow lands (Baird,2013). At the end of this lengthy process –which can take years – a successful communalland title will include just a portion of theirpreviously held lands. Few communities havereached this point (Woods & Kuch, 2012). Fur-thermore, given the rapidity and force withwhich land concessions are being made now, itremains to be seen how effective Indigenouscommunal land titles will be in protecting land.Although there are numerous examples of state

forces used to protect concessionaires from thepeople they displace, there is not a singleexample of that same force used to protectIndigenous communities. Although the RGChas produced legislation that makes the conceptof Indigenous land rights legally imaginable,without meaningful sociostructural investmentby the state in promoting and encouraging theserights, their realisation seems remote at best,regardless of NGO support.

For the reasons stated above, none of the Kuycommunities I visited were pursuing Indigenousregistration, but all were instead seeking a morelimited kind of land protection, known as Com-munity Protected Areas (CPAs), in which thestate may grant temporary land rights so long asthe community land use satisfies the state’sexpectations. It is not a title at all, and can berevoked at any time. At the time of fieldwork,none of the communities had succeeded inachieving even the limited land security of CPAstatus. Yet despite the rather hopeless situationthat Kuy and other Indigenous peoples findthemselves in, I found few people who had fullyresigned themselves to inevitable dispossessionand eviction.

An alternative land future based on Kuyculture and history

There is an alternative to the current landregime that dominates in rural Cambodia, but itrequires a cultural shift to non-discriminationthat includes rural and especially Indigenouspeoples in Cambodia as rights-holders in sub-stantive decision-making about development. Afull account of the heterogeneous Indigeneity ofthe Kuy may provide a new basis for imagininga different future, based on a pluriculturalunderstanding of Cambodia’s heritage. There isemerging new evidence to suggest that the Kuyplayed different roles in the past than simply asethnic minorities and slaves of lowland states.There are several sources for this alternatehistory, including colonial era documentarysources, archaeology and Kuy oral traditions Icollected during fieldwork in 2011.

In Preah Vihear, Kuy land regimes during theFrench colonial period were based not only oneconomies of shifting cultivation and foresthunting and gathering, but also significantlyintegrated with local practices of iron smelting

Indigenous land rights in Cambodia

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 317

and blacksmithing – especially in Rovieng – theoutput of which variably circulated as a meansof exchange. These regimes complicate theimage of Indigeneity because they includeindustrial practice. Iron making is not includedin the state’s criteria for Indigenous ‘traditionallivelihood’. Although Kuy iron making wentinto decline by the 1940s, what is happening inthe twenty-first century Kuy territory can beread as a new appropriation of their heritage byoutside corporations conducting large-scalemining operations in the same area where Kuypeoples produced iron for centuries, only nowconferring little or no benefits to affected Kuycommunities. Had the RGC actively promotedtheir collective rights, the Kuy could have par-ticipated as stakeholders in the design of miningoperations in Rovieng, and designed a differentland use strategy than what has in fact devel-oped – the shadowy system of MCs. Theconcept of Indigenous-led sustainable ironindustrial production does not sit well with aconcept of Indigeneity that limits it to otherkinds of economic practices like forest huntingand gathering and/or swidden farming; but theKuy traditionally practised all of the above.

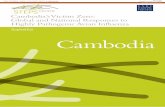

Harmand (1876) travelled through the terri-tory between the Steung Sen and Mekong rivers,and made the first map of the area. He con-cluded that most of what is today Preah Vihearprovince, the western part of Steung Treng andthe northeastern part of Kampong Thom, wasthe country of the Kuys since time immemorial.He also identified multiple groups of Kuypeoples, based on linguistic and economic vari-ation: Kuy Hah or Kuy Dek, Kuy Porrh, KuyNtoh, Kuy Mnoh, and Kuy Mahai (Fig. 1). KuyDek is one of the two names recorded byHarmand for the Kuy peoples living in theRovieng area which translates as ‘iron Kuy’.Harmand observed widespread practice of ironmaking in this area, and estimated that its dura-tion as ‘since the time of Lycurgus’. He foundthat Kuy iron tools and weapons circulated tothe lowland Khmers and also up into Laos, witha reputation for high quality. Other accountsfrom the early twentieth century corroborateHarmand’s, in terms of Kuy ethnicity, geographyand iron production (Dufossé, 1918; Levy,1943). During the 1960s, Dupaigne carried outethnographic work in Rovieng and identified anumber of Kuy-associated iron-making sites.

While he observed that this tradition went intodecline during the French colonial era, he foundsubstantial evidence of its past extent, and con-cluded that the Kuy had long been the ‘mastersof iron and fire’, in both a material and religioussense (Dupaigne, 1987). In 2012, Cambodianarchaeologist Thuy Chanthourn announced thediscovery of five major iron industry sites, allwithin Kuy territory, and all dating to ca. A.D.800 (Vachon and Kuch, 2013).

During the 1990s Bruno Bruguier built onLunet’s earlier survey of archaeological sites inthe province of Preah Vihear, and reportedlyproduced a new map containing over 4000sites, most of which have not been systemati-cally studied (Ashish John, pers. comm., July2011; Bruguier, 1999; Lunet de Lajonquiére,1902). Many of these are temple and/or shrinesites, located within the same area earlier iden-tified by Harmand and others as Kuy territory(DuFossé, 1934; Levy, 1943). Recent archaeo-logical studies of the Angkorian road systemsconfirm the existence of a road constructed fromAngkor to the site of Preah Khan of KampongSvay (PKKS), which lies halfway between thecore zone of Angkor and what is today RoviengDistrict (Hendrickson, 2010; cf. also Bastian,1865). There is a possible association betweenthe existence of this road, iron making and thethousands of sites distributed in Kuy territory. Infact the evidence suggests that iron making inthis region preceded the road’s construction,dating from the eighth century into the twentiethcentury (Hendrickson and Price, 2011). The Kuymay have created the steel and iron toolsthat were critical to the success of the KhmerAngkorian state-empire’s expansion. MitchHendrickson, who is currently conductingarchaeological research on Kuy iron industries,suggests that PKKS may have served as a bound-ary of sorts, between the Angkor core zoneand Kuy territory (Hendrickson, pers. comm.,2013).

Besides PKKS, another significant site forsituating Kuy agency in the past may be thelarge pre-Angkorean city of Sambor Prei Kuk(or Isanapura) which, referencing Harmand’s(1876) map, is located in the southern flank ofKuy territory. It is just south of Rovieng in whatis today a northeastern district of KampongThom province. The significance of this siteis its association as the possible ‘capital’ of the

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd318

pre-Angkorean state-like polity called ‘Chenla’by Chinese travellers during the seventh andeighth centuries (Vickery, 1998; Stark, 2006). Aswith PKKS, if we presume a fairly long andongoing Kuy occupation of the territory thatHarmand mapped out, Sambor Prei Kuk seemsgeographically situated for interaction with Kuypeoples; although the nature of this interactionremains elusive. It is conceivable that Kuypeoples played a greater role in the formation ofChenla and Angkor than the literature suggests.

Finally, the oral traditions I collected in Kuyvillages, along with observations of the sur-rounding landscapes, provide the strongestassociations of Kuy peoples as iron-making

social actors in the development of Angkor.These include accounts that the Kuy builtAngkor Wat and other structures, not as slavesbut more like engineers, using Kuy technology,elephants and supernatural power. I also col-lected accounts in one of the villages, of itsbeing named after an event that happened longago when a king visited the area, stayed for awhile and then went west to found Angkor. Iobserved part of an ancient raised road said tohave once connected the Rovieng area to PKKSand Angkor. While pausing nearby under a treegrowing on top of an old and massive iron slagheap, an elder relayed what he knew of theritual process of traditional iron making, which

Figure 1. Map of Preah Vihear Province in northern Cambodia, showing the general historical–traditional locations ofdifferent Kuy groups. Dotted white lines indicate provincial boundaries. Solid white lines indicate international boundaries(Thailand and Laos to the north). Shaded polygons and circles indicate the locations of all known land concessions in the

area, as of late February 2013. Lighter-shaded polygons indicate economic land concessions, while darker shaded polygonsand circles indicate mining concessions. Rovieng District is centred in the territory of the Kuy Dek/Hah. The stars indicate

the locations of important Angkorean and pre-Angkorean sites mentioned in the article (sources: Harmand, 1876; Levy,1943; Open Development Cambodia, 2013).

Indigenous land rights in Cambodia

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 319

involved not only smelters and blacksmiths, butalso a ritual shamanistic dancer, a chay, whowould perform in the vicinity of the furnace andsemiotically instantiate the process as a cosmicact of procreation, similar to rituals reported inother tribal iron-making groups (Haaland et al.,2002).

In combination, these different pieces of theKuy past suggest that the Kuy were not alwaysjust small-scale groups of forest foragers andswidden farmers subject to enslavement bylowland states, but may have played moreactive roles in the state-building projects ofChenla and Angkor, as semi-sedentary industri-alists engaged in the production and circulationof the iron tools and weapons that allowedstates to assume physical shape and geographicextension. Maybe the Kuy never were Chuang.It remains to more fully examine this articula-tion of Indigeneity through future ethnographic,historical and archaeological research, but if itproves to be salient, it not only challenges thestate’s essentialist framing of Indigeneity inCambodia, but also changes the picture of theworld heritage that is represented by AngkorWat, by suggesting a more pluricultural origin ofAngkor, and fluidity of interactions between theuplands and the lowlands, in which Kuypeoples are situated dynamically in between.Of course, if the expansion of land concessionsin Cambodia continues in its current forms,the pursuit of answers to such questions will beimpossible. The peoples and the sites will belargely obliterated, along with knowledge of thepolitical ecologies in which they gave rise. Yetgiven that tourism to Angkor Wat is one of thelargest drivers of the Cambodian economytoday, it seems that it would be in the betterinterests of Cambodia to protect and developthe greater heritage in which Indigenouspeoples like the Kuy have made and can makea significant and agentive contribution.

Conclusions

Indigenous identity may be contested and ren-dered chimeric by power, but it nevertheless isan emergent and observable form of sociality inthe twenty-first century, which is evident in therelations, discourses and international laws gen-erated through human interactions at multiplesites and scales. At international sites like the

UNPFII, Indigenous identity is most evident,and explicitly linked to human rights lawthrough generated interventions, recommenda-tions, declarations, legal instruments and con-ventions that posit Indigenous groups andindividuals as rights-holding human beingsseeking a future in which they can maintaintheir viability and live well. At national sites likethe RGC National Assembly or the offices of theMRD and MI, Indigenous identity is moreopaque, as evidenced by ambivalent laws andpolicies that recognise Indigenous peoples butsignificantly limit the physical possibilities oftheir existence, and foreclose ontologically onIndigenous futures as having no place in theevolving neoliberal Kingdom. At local sites likethe Kuy villages where I worked, Indigenousidentity is even more evasive among relativelypowerless people who are quite fatalistic abouttheir situation, yet not fully resigned to collec-tive extinguishment. Amid these different sitesand scales move other sets of social actors,including Indigenous activists and NGOs,whose actions seek to effect trans-scalar trans-lation between local communities and interna-tional law, mediated (if not frustrated) via thenational scale of the state. For Indigenous iden-tity and land rights to be promoted and pro-tected in Cambodia, not only are better lawsand political will on the part of the staterequired – although these are absolute prereq-uisites, as the above analysis of the Land Lawand land concession practices makes clear. Alsorequired is a different understanding of whatexactly Indigeneity engages, for it is not simplyan essentialist reification of a static portfolioof archaic and romantic behaviours. Rather,Indigeneity is an emergent process of humansociality arising within a global sociopoliticalecology and time of intensified resource captureand extraction, a strategy of adaptation basedon political negotiation that is not entirelyimagined, but also grounded in the historiesof peoples’ experiences. By approaching thesehistories from an ethnographically groundedhuman rights perspective, it is possible tosharpen our understanding of the diverse pathsof humanisation and history pursued by groupsnow claiming Indigeneity, and open the con-ceptual door to alternative futures in whichhuman difference may thrive. If the collectivecategory of Indigenous people is contingent and

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd320

in flux, so, too, are all other categories of humansociality, including the state. I have argued inthis article that Indigeneity is a new categorythat has implications not only for the rightsholders, but globally implies that within statesnew collectivities may emerge, which drawupon distinctive ethnic and cultural experiencenot to declare independence from existingstates or exercise chauvinism over other groups,but to generate actual pluricultural formationsthat radically reform the state from within. Thesynthesis of Kuy history presented here suggestsan outline of human agency in which politicalnegotiation, resistance, exclusion,and refusalare important elements of the Kuy past, and thatwith further research may generate not only abetter understanding of Indigeneity, but providenew ideas for future development in Cambodiathat favour human equity and biocultural diver-sity, which I contend is beneficial.

References

AIPP, IWGIA and EU (2011) Asean’s indigenous peoples.Chang Mai: Asia Indigenous Peoples’ Pact, the Inter-national Work Group on Indigenous Affairs, and theEuropean Union.

Baird, I.G. (2011) The construction of ‘indigenous peoples’in Cambodia, in Y. Leong (ed.), Alterities in Asia:Reflections on identity and regionalism, pp. 155–176.London: Routledge.

Baird, I.G. (2013) Indigenous peoples and land: Com-paring communal land titling and its implicationsin Cambodia and Laos, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54(3):269–281.

Bastian, A. (1865) A visit to the ruined cities and buildingsof Cambodia, Journal of the Royal GeographicalSociety of London 35: 74–87.

Béteille, A. (1998) The idea of indigenous people, CurrentAnthropology 39(2): 187–192.

Brinkley, J. (2011) Cambodia’s curse: The modern history ofa troubled land. New York: Public Affairs Books.

Bruguier, B. (1999) La carte archéologique informatisée duCambodge. Laos, Restaurer & Préserver le PatrimoineNational. Vientiane: Cahiers de France.

Chandler, D. (1993) The tragedy of Cambodian history:Politics, war, and revolution since 1945. New Haven,Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Chandler, D. (2008a) A history of Cambodia, 4th edn.Boulder: Westview Press.

Chandler, D. (2008b) [1978]. Songs at the edge of the forest:Perceptions of order in three Cambodian texts, in J.Ledgerwood and A. Hansen (eds.), At the edge of theforest: Essays in honor of David Chandler, pp. 28–46.Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Chou, T. (aka Zhou Daguan) (1993) [A. D. 1236-37]. Thecustoms of Cambodia. Bangkok: The Siam Society.

CHRAC (Cambodia Human RightsAction Committee) (2008)Rights razed: Forced evictions in Cambodia. CambodiaHuman Rights Action Committee Report. Phnom Penh:Cambodia Human Rights Action Committee.

CHRAC (Cambodia Human Rights Action Committee)(2009) Losing ground: Forced evictions and intimida-tion in Cambodia. Cambodia Human Rights ActionCommittee Report. Phnom Penh: Cambodia HumanRights Action Committee.

CHRAC (Cambodia Human Rights Action Committee)(2010) Still losing ground: Forced evictions and intimi-dation in Cambodia, 2010. Cambodia Human RightsAction Committee Report. Phnom Penh: CambodiaHuman Rights Action Committee.

DuFossé, M. (1934) Monographie des peuplades Kouys deCambodge, Extrême Asie 83: 553–568.

Dumont, L. (1981) [1966]. Homo hierarchicus: The castesystem and its implications. Chicago, Illinois: Univer-sity of Chicago Press.

Dupaigne, B. (1987) Les maitres du fer et du feu: Etude de lametallurgie du fer chez les Kouy du nord du Cambodge,dans la contexte historique et ethnographique del’ensemble Khmer (Volume 4: PhD dissertation). Paris:Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Social.

Eang, M. (2012) CPP lawmaker to apologize for insult toBunong minority, Cambodia Daily, 30 November.Retrieved 2 December 2012.

EC (Equitable Cambodia) (2013) Briefing paper: TheChinese North-South railway project. Phnom Penh:Equitable Cambodia and Global South. Retrieved17 May 2013, from Website: http://www.equitablecambodia.org/reports/

Erni, C. (ed.) (2008) The concept of indigenous peoples inAsia: A resource book. Copenhagen: InternationalWork Group for Indigenous Affairs.

Erni, C. and C. Nilsson (eds.) (2008) Cambodia, Theconcept of indigenous peoples in Asia: A resourcebook, pp. 349–355. Copenhagen: International WorkGroup for Indigenous Affairs.

Global Witness (2007) Cambodia’s family trees: Illegallogging and the stripping of public assets by Cam-bodia’s elite. Retrieved 17 May 2013, from Website:http://www.globalwitness.org/library/cambodias-family-trees

Global Witness (2009) Country for sale: How Cambodia’selite have captured the country’s extractive industries.Retrieved 17 May 2013, from Website: http://www.globalwitness.org/library/country-sale

Haaland, G., R. Haaland and S. Rijal (2002) The social lifeof iron: A cross-cultural study of technological, sym-bolic, and social aspects of iron making, Anthropos97(1): 35–54.

Hansen, A.R. and J. Ledgerwood (eds.) (2008) At the edge ofthe forest: Essays on Cambodia, history and narrativein honor of David Chandler. Ithaca, New York: CornellUniversity Press.

Harmand, J. (1876) Voyage au Cambodge, Bulletin de laSociete de Geographie 16(12): 337–367.

Hendrickson, M. (2010) Historic routes to Angkor: Devel-opment of the Khmer road system (ninth to thirteenthcentury AD) in Mainland Southeast Asia, Antiquity84(324): 480–496.

Indigenous land rights in Cambodia

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd 321

Hendrickson, M. and T.O. Price (2011) Industries of Angkorproject: Iron Kuay. March 2010 Field CampaignReport. University of Sydney.

Hinton, A.L. (1998) A head for an eye: Revenge in theCambodian genocide, American Ethnologist 25(3):352–377.

Jonsson, H. (2010) Above and beyond: Zomia and the eth-nographic challenge of/for regional history, Historyand Anthropology 21(2): 191–212.

Jonsson, H. (2012) Paths to freedom: Political prospecting inthe ethnographic record, Critique of Anthropology32(2): 158–172.

Keating, N.B. (2012) From spirit forest to rubber plantation:The accelerating disaster of development in Cambo-dia, ASIANetwork Exchange 19(2): 68–80.

Kunmakara, M. (2013) China to invest $9.6 b in Cambodia,Phnom Penh Post 1 January 2013. Retrieved 3 January2013.

Kuper, A. (2004) Reply, Current Anthropology 45(2): 265–266.

Levi, J. and B. Maybury-Lewis (2012) Becoming indigenous:Identity and heterogeneity in a global movement, inG.H. Hall and H.A. Patrinos (eds.), Indigenouspeoples, poverty, and development, pp. 73–116. NewYork: Cambridge University Press.

Levy, P. (1943) Recherches Prehistoriques Dans La RegionDe Mlu Prei (Cambodge). Hanoi: Ecole Francaisd’Extreme Orient.

Li, T.M. (2000) Articulating indigenous identity in Indone-sia: Resource politics and the tribal slot, ComparativeStudies in Society and History 42(1): 149–179.

Lunet de Lajonquiére, E. (1902) Inventaire Descriptif desMonuments du Cambodge. Paris: Ernest Laroux.

Mann, N. and L. Markowski (2005) A rapid appraisal of Kuydialects spoken in Cambodia. SIL Electronic Reports2005-018. Retrieved 18 May 2013, from Website:http://www.sil.org/resources/archives/9014.

Merry, S.E. (2006) Human rights and gender violence.Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Open Development Cambodia (2013) Maps. Retrieved15 February 2013, from Website: http://www.opendevelopmentcambodia.net/maps/

RGC (Royal Government of Cambodia) (2001) Nationalland law. Royal Decree # NS/RKM/0801/14.

Saugestad, S. (2004) Discussion: On the return of the native,Current Anthropology 45(2): 263–264.

Scott, J.C. (2009) The art of not being governed: An anar-chist history of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven,Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Seidenfaden, E. (1952) The Kui people of Cambodia andSiam, Journal of the Siam Society 39(2): 144–183.

Stark, M. (2006) Early mainland Southeast Asian landscapesin the first millenium A. D, Annual Reviews in Anthro-pology 35: 407–432.

Stavenhagen, R. (2008) Indigenous peoples as new citizensof the world. Paper presented at the First Conferenceon Ethnicity, Race and Indigenous Peoples In LatinAmerica and the Caribbean. University of California,San Diego.

Subedi, S.P. (2012) Report of the special rapporteur on thesituation of human rights in Cambodia addendum: Ahuman rights analysis of economic and other landconcessions in Cambodia. UN Human Rights Council,21st Session, Agenda Item 10: Technical Assistanceand Capacity-Building. A/HRC/21/63/Add.1.

Swift, P. (2013) Changing ethnic identities among the Kuy inCambodia: Assimilation, reassertion, and the makingof Indigenous identity, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 54(3):296–308.

Trouillot, M.-R. (1991) Anthropology and the savage slot:The poetics and politics of otherness, in R. Fox (ed.),Recapturing anthropology: Working in the present, pp.17–44. Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of AmericanResearch.

Trouillot, M.-R. (2001) The anthropology of the state in theage of globalization: Close encounters of the deceptivekind, Current Anthropology 42(1): 125–138.

Turner, T. (1997) Human rights, human difference: Anthro-pology’s contribution to an emancipatory culturalpolitics, Journal of Anthropological Research 53(3):273–292.

Vachon, M. and N. Kuch (2013) The ancient ironworks ofAngkor, The Cambodia Daily, 5 March 2013.Retrieved 6 July 2013.

Vickery, M. (1998) Society, economics, and politics in Pre-Angkor Cambodia: The 7th–8th centuries. Tokyo: TheCenter for East Asian Cultural Studies for UNESCO,The Toyo Bunko.

Vrieze, P. and N. Kuch (2012) Carving up Cambodia: Oneconcession at a time. A joint Licadho/Cambodia dailyanalysis, The Cambodia Daily Weekend, (730), March11–12.

White, B., M.B. Saturnino Jr, R. Hall, I. Scoones and W.Wolford (2012) The new enclosures: Critical perspec-tives on corporate land deals, Journal of PeasantStudies 39(3–4): 619–647.

Woods, B. and N. Kuch (2012) Gov’t to award three com-munal land titles to ethnic Bunong, The CambodiaDaily, 27 September 2012. Retrieved 28 September2012.

N.B. Keating

© 2013 Victoria University of Wellington and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd322