“Just Like Independence Day!” The Falling Towers On 9/11 and the Hegemonic Function of...

Transcript of “Just Like Independence Day!” The Falling Towers On 9/11 and the Hegemonic Function of...

===UNPUBLISHED PAPER===

===If you like my piece, I invite you to become my co-author:

help me to improve my piece and to publish it!===

Running Head: “JUST LIKE INDEPENDENCE DAY!” THE FALLING TOWERS ON

9/11 AND THE HEGEMONIC FUNCTION OF INTERTEXTUALITY

“Just Like Independence Day!”

The Falling Towers On 9/11 and the Hegemonic Function of

Intertextuality

Author: Davide Girardelli, Ph.D.

“Just Like Independence Day!”

The Falling Towers On 9/11 and the Hegemonic Function of

Intertextuality

“Just like Independence Day!”

Abstract

The focus of this study is to illustrate how the movie

Independence Day served as a hegemonic vehicle for unobtrusively

reinforcing the Bush administration’s interpretive framework of

the 9/11 events. The impetus for the paper was offered by the

numerous intertextual references to the movie that appeared in

mainstream media from the outset of the tragedy. Following

Kellner’s (1995) concept of “ideological critique,” I first

examine the narrative of Independence Day through a comparison with

Fight Club. Both movies portray analogous scenes of crumbling towers

but in two different ideological contexts, which the comparison

intends to highlight. Second, I examine the ideological subtext

of Independence Day with those of two key speeches given by

president Bush. This second ‘diagnostic’ comparison offers

evidences that a similar ideology underlies Independence Day and

Bush’s speeches. I argue, therefore, that the intertextual

references between Independence Day and the WTC tragedy were

functional in activating and promoting the hegemonic ascent of an

interpretive framework that is consistent with the one proposed

by the Bush administration.

1

“Just like Independence Day!”

“Just Like Independence Day!”

The Falling Towers on 9/11 and the Hegemonic Function of

Intertextuality

Introduction

“We won in the end. Bring your family. You’ll be proud of it.Diversity. America. Leadership. Good over Evil.”

Bob Dole on Independence Day (reported in Rogin, 1998, p. 12)

At 10:29 AM on September 11, 2001, the North Tower of the World

Trade Center (WTC) crumbled, following the same tragic destiny of

the South Tower, which collapsed at 10:00 AM in a thick, grayish

smoke of debris. Once the feelings of horror and bewilderment

started settling down like the debris at Ground Zero, the heart

and minds of thousands of eyewitnesses and millions of TV viewers

were filled with “a need to understand the meaning of what

happened” (Reser & Muncer, 2004, p. 283).

The dark and ominous roar of the falling WTC towers is now

part of everyone’s memory. However, the consequences of the

tragic events of 9/11 still resonate around the globe: The

political and social systems of entire nations has been reshaped

2

“Just like Independence Day!”

(Afghanistan and Iraq); Long-standing alliances have been put

into question (the US-EU rift); Subdued tensions have assumed new

impetus (the divide between Western and Islamic societies)

(Friedman, 2003; Kagan, 2003; Zizek, 2002). Many of these

consequences do not directly stem from the events of 9/11, but

from the interpretive framework proposed by the Bush

administration to explain what happened on that day. This

interpretive framework can be succinctly summarized in this way:

“We are at war; this is our Pearl Harbor; we were attacked by

cowards; America’s freedoms are under assault; an international

war on terrorists and terrorism must be launched; if innocent

citizens are killed, so be it” (Denzin, 2002, p. 6). The

administration’s perspective has emerged as the dominant one and

provided the rationale for military actions such those in

Afghanistan and Iraq (Entman, 2003, 2004; Kellner, 2003).

Momentarily putting aside the controversial political

decision-making process within the Bush administration (Clarke,

2004; National Commission on Terrorist Attacks, 2004; Woodward,

2004), academic research is systematically illuminating how those

within and outside the U.S. have interpreted the facts of

3

“Just like Independence Day!”

September 11th, studying the collective process of

rationalization (Rasinski, Berktold, Smith, & Albertson, 2002;

Reser & Muncer, 2004; Smith, Rasinski, & Toce, 2001) and the role

of the media in the information seeking process after the events

on 9/11 (Boyle et al., 2004; Cho et al., 2003).

Eisman (2003) reports that in the wake of the 9/11 attacks

more than 74 percent of Americans aged 18-54 turned to television

as their first source for information, while 5-7 percent turned

to printed media. Critical scholars have argued that U. S.

mainstream media have--intentionally or not--uncritically adopted

the Bush administration’s interpretation of what happened on 9/11

and espoused its rhetoric, therefore creating consensus on the

administration’s behalf (Chomsky, 2001; Denzin, 2002; Eisman,

2003; Entman, 2004; Kellner, 2003; Lowenstein, 2003).

This paper expands the previous argument and analyzes the

function of the references to a popular cultural artifact (the

movie Independence Day) on 9/11 and in the days immediately

following that date. Building on the concepts of intertextuality

(Barthes, 1977; Kristeva, 1986a, 1986b; Ott & Walter, 2000) and

hegemony (Bates, 1975; Gramsci, 1971; Williams, 1969), I intend

4

“Just like Independence Day!”

to demonstrate how these references have—intentionally or not—

contributed to the diffusion of an ideological framework

consistent that of the Bush administration and therefore

unobtrusively generating consensus for the administration’s

actions.

The Hegemonic Function of Intertextuality

9/11 and popular culture

On 9/11, NBC’s Ron Insana reported live directly from the

WTC. Covered with gray ash, he described the fall of the South

Towers thus: “…honestly, it was like a scene out of Independence

Day. Everything began to rain down. It was pitch black around us

as though--the winds were whipping through the corridors in lower

Manhattan.” (NBC News, 2001).

Many blockbuster movies have been compared to the events of

9/11. The most frequently cited ones The Siege (Wilkins & Downing,

2002; Zwick, 1998) and Independence Day (Hemmerich, 1996). These

cinematographic references should not be disregarded as

meaningless or inconsequential. Instead, they reflect the

important role that popular cultural artifacts play in Western

5

“Just like Independence Day!”

societies beyond mere entertainment (Denzin, 1991; Kellner, 1995;

Wilkins & Downing, 2002). According to Denzin (1991):

Members of the contemporary world are voyeurs adrift ina sea of symbols. They know and see themselves through cinema and television. If this is so, then an essentialpart of the contemporary postmodern American scene can be found in the images and meanings that flow from cinema and TV. (pp. vii-viii)

A newswire broadcast by Business Wire (2001) right after the

tragedy shows that the association between reality (the attack on

the World Trade Center) and fiction (Independence Day and The Siege)

suggested—intentionally or not--by several media outlets has not

passed unnoticed. According to the wire, rentals of The Siege

“soared to No. 191 the week ended Sept. 16” (par. 7). In

addition,

Rental activity for Independence Day … was significantly stimulated by the tragedy on Sept. 11. Independence climbed from No. 910 the week prior the attack to No. 393 the week ended Sept. 16 experiencing a (+) 360% growth in weekly revenue. (par. 9)

Concepts and analytical tools employed to analyze popular

cultural artifacts are therefore relevant to generate useful and

provocative insights on the tragic events of 9/11. In a recent

article, Wilkins and Downing (2002) show how the narrative of the

6

“Just like Independence Day!”

movie The Siege (Zwick, 1998) serves as a vehicle for stereotyping

Arab identity and for promoting an Orientalist ideology (Said,

1978, 1997). In this paper, I focus instead on Independence Day

using the concept of “ideological critique” (Kellner, 1995) and

examine how the problematic relationship between the movie’s

narrative and the Bush administration’s ideology.

Intertextuality as hegemony

Insana’s reference to Independence Day exemplifies the concept

of “intertextuality” (Barthes 1977; Kristeva 1986a, 1986b). Media

scholars interpret the notion of intertextuality in two distinct

ways (Ott & Walter, 2000). On one hand, this concept refers to an

interpretive practice that emphasizes the active role of the

reader in the creation of meaning through analogies or

connections with other texts. On the other hand, intertextuality

is used as an intentional textual strategy. Ott and Walter (2000)

identify three major categories in the latter: 1) parodic

allusion--one text includes a caricature of another text; 2)

creative appropriation--one text reproduce a fragment of another

text in its integrity; 3) self-reflexive reference—a writing

7

“Just like Independence Day!”

style that “deliberately draws attention to its fictional nature

by commenting on its own activities” (p. 438).

Connecting the notion of intertextuality with the one of

hegemony, I propose a fourth category in Ott and Walter’s (2000)

categorization, namely the “hegemonic” function of

intertextuality. The basic premise of the concept of hegemony is

expressed succinctly by Bates (1975): “Man is not ruled by force

alone, but also by ideas” (p. 351). Hegemony is a process through

which a dominant class maintains its dominant position not only

by mere force but also by popularizing and creating consensus for

its world view (Bates, 1975; Gramsci, 1971; Williams, 1969). Mass

media play an important role in the hegemonic process (Condit,

1994; Entman, 2003, 2004; Lewis, 1999), since “the mass media do

not define reality on their own but give preferential access to

the definitions of those in authority” (McQuail, 2000, p. 97).

In the case of the intertextual references to Independence Day

on 9/11, I argue that they function as a reinforcement of the

hegemonic discourse of the Bush administration. Independence Day

is, in fact, not a neutral, ideologically free artifact. At a

closer look, it reflects a loaded ideological subtext that shares

8

“Just like Independence Day!”

several commonalities with the Bush administration’s

interpretation of the events of 9/11.

The idea of “ideological critique” (Kellner, 1995)

constitutes the methodological backbone of this paper. My

argument is developed on two levels. First, I examine the

ideological subtexts of Independence Day and Fight Club (Fincher,

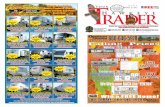

1999). Both movies (see appendix 1 for synopses) portray

analogous scenes of crumbling towers that can be associated with

the WTC tragedy (figure 1). Yet, these scenes are included in two

radically different ideological contexts, which my comparison

intends to highlight.

Similarly to Eisman (2003), who examined the coverage in

Time and in Das Spiegel to bring to light the American news media

responses to 9/11, the use of comparison is revelatory not only

in the mystifications and the taken-for granted assumptions in

the narrative of Independence Day, but also in the features that

are systematically excluded or marginalized. Both the marked and

the silenced elements are in fact part of the “ideological

project of the text” (Kellner, 1995, p. 113).

9

“Just like Independence Day!”

Second, I will compare the ideological subtext of

Independence Day with those of two key speeches given by George W.

Bush (2001a; 2001b) right after 9/11. In these two speeches, Bush

first presented the ‘official’ version of the facts of 9/11 and

his administration’s plan of action, later to be developed in the

doctrine of ‘pre-emptive war’ (Agathangelou & Ling, 2004;

Kellner, 2004; Murphy, 2003).

The second comparison has a ‘diagnostic function’ and is

intended to “allow insight into the multiple relations between

text and context, between media culture and history” (Kellner,

1995, p. 116). Its goal is to highlight the congruencies between

the two subtexts despite their superficial differences and to

show that Independence Day and Bush’s speeches share the same

underlying logic. In sum, the intertextual references between

Independence Day and the WTC tragedy were functional in activating

and promoting the hegemonic ascent of a specific interpretive

framework that is consistent with the one proposed by the Bush

administration.

10

“Just like Independence Day!”

Figure 1. From left to right: The destruction of the Empire State Buildingfrom Independence Day, the collapse of the South Tower of the WTC on 9/11, and

the last scene of Fight Club.

Falling Towers in Modern and Postmodern worlds

Cinema has a primary ideological function in reinforcing the

capitalist structure and values of American contemporary society.

According to Boggs (2001),

From its inception film production, always a major partof the culture industry, embellished system-sustaining values such as patriotism, the work ethic, and puritanical views of sexuality and family life, generating strongly positive attitudes toward big business and government, all part of what Antonio Gramsci called ideological hegemony. (p. 353)

Upon a closer look, Hollywood production appears nonetheless

more complex and less monolithic. In addition to a modernist

production of “blockbusters, spectacles, and hyper-commodified

fare often comprised in mindless and formulaic action sequences,

disjointed visual images, cartoonish characters, threadbare

plots, and overpowering sound levels” (p. 354), Boggs identifies

an alternative format of cinema that he defines as postmodern.

11

“Just like Independence Day!”

Postmodern cinema emerged at the beginning of the 1980s and

possesses formal and ideological characteristics such as

“thematic emphasis on chaos, intrigue, and paranoia, death of the

hero, disjointed narrative structures, and embrace of dystopia”

(p. 351). As Boggs (2001) explains,

Themes of alienation, conflict, rebellion, and mayhem now surfaced in movies of all genres, becoming visible even in such commercially successful pictures as The Godfather, Nashville, Annie Hall, Blade Runner, JFK, and Pulp Fiction. (p. 354)

The different structural and ideological features of

Independence Day and Fight Club exemplify Boggs’ (2001) broad

distinction between modern and postmodern cinematography. In the

next section, the two movies will be examined following selected

dyads from Hassan’s (1991) classic summary of the underlying

assumptions of modernism and postmodernism. Table 1 outlines the

categories used in the analysis.

Independence Day(Modernism)

Fight Club(Postmodernism)

1. Form (closed) Anti-form (open)2. Design Chance/Chaos3. Determinacy Indeterminacy4. Genital/Phallic Polymorphous/AndrogynousTable 1. Analysis between Independences Day (Hemmerich 1996) and Fight Club

(Fincher 1999), following Hassan’s (1991) heuristic scheme.

12

“Just like Independence Day!”

1) Form (closed) versus Antiform (open). The narrative

structure of the two films differs on many levels. Independence Day

has a linear narrative structure with a clear beginning (initial

status of equilibrium), middle (disruption of the equilibrium

cased by the alien invasion), and end (defeat of the aliens,

return to initial equilibrium). The genre of the movie is also

easily recognizable: Classic ‘earthlings vs. aliens’ science-

fiction in the tradition of The War of the Worlds (Dowell, 1996;

Haskin, 1953; Rogin, 1998).

Minimal variations, defined as “collateral inventions” (Eco,

1966), introduce elements of originality in an otherwise highly

predictable narrative structure. The most important collateral

inventions in Independence Day are politically correct themes and a

multicultural cast of characters. These elements can be

appreciated in comparing Independence Day with the science-fiction

movies of the Cold War era, which typically featured have all-

white casts (Rogin, 1998). Nonetheless, collateral inventions do

not substantially affect the overall predictability of the plot,

because “the true and original plot remains immutable and

suspense is stabilized curiosity on the basis of a sequence of

13

“Just like Independence Day!”

events that are entirely predetermined” (Eco, 1966, p. 57). In

the case of Independence Day, Dowell (1996) states:

Despite such convoluted subtexts [the author refers to elements of originality that are equivalent to Eco’s minimal inventions], Independence Day makes a great show of constructing a simple, linear plot and old-fashionedcharacter typology that recall not only Fifties B-movies but also the made-for-television features that replaced them. (par. 12)

Fight Club breaks the linear narrative that characterizes

Independence Day. The movie actually begins with the end of the

narrative and proceeds with flashbacks. Fight Club cannot easily be

categorized according to any previous, predefined genres. For

instance, the film has been described as a “pitch-black comedy,

an over-the-top, consciously outrageous social satire,

characterized by excess and absurdity, and therefore guaranteed

to delight or disturb sizable portions of any viewing audience”

(Crowdus, 2000, par. 3). Giroux (2001) applies to the movie the

label “scuzz cinema” to describe Fight Club’s mixture of “violence,

cynicism, glitz, and shootouts” with “updated gestures toward

social relevance—that is, a critique of suburban life,

consumerism and so forth” (p. 26).

14

“Just like Independence Day!”

2) Determinacy versus Indeterminacy . As already observed,

the plot of Independence Day is highly predictable. The audience

knows from the beginning that, despite the initial difficulties,

the heroes will defeat the aliens and restore the original peace

and order that the alien invasion cruelly disrupted. From the

very first second it is clear that the destiny of the aliens is

to be defeated. As Dowell points out (1996),

The only contribution [of the giant alien ships] … is an apocalyptically satisfying shot of cars tumbling endover end down city streets filled with panicked citizens, propelled by a gigantic fireball that will soon engulf all those nameless extras and sacrificial supporting players stuck in traffic. (par. 12)

Therefore, the real enjoyment in the movies is obtained not

from the overall plot but from the spectacular elements, in

particular the catastrophic destruction scenes (Geoff, 1999). At

the end of the movie, the audience can leave the theater with a

sense of satisfaction because the conclusion solves the dramatic

tension without any ambiguities. The main characters of the movie

in fact behaved according to their prescribed roles. The aliens

played the classic role that cruel aliens play (moved by

senseless hatred for human beings). The action hero, Captain

15

“Just like Independence Day!”

Hiller, acted like we expect action heroes to act (courageously

and bravely). The behavior of the scientist, Levinson, reflected

the mannerism of stereotypical scientists (at the same time goofy

and clever). The President Whitmore, behaved like we “expect”

Presidents of the Unites States to behave (offering protection

and leadership to a resigned and powerless World).

The plot of Fight Club refuses instead to fulfill the

expectations of the audience and instead challenges them. The

movies can be seen as an “anti-detective story” (Spanos, 1972):

Expectations are frustrated, the crime is not solved, and no

totalized world of order prevails over chaos. Let us focus for

instance on the main characters of the movie. Initially, the plot

involves two main characters: Jack, a white-collar, and Tyler, a

squatter. However, at the hands of an extraordinary plot twist,

the public discovers at the end of the movie that the two

characters are in reality the same person. Fight Club is, in fact,

a story narrated in first person by a mentally ill individual

(Jack) who suffers from split personality:

A tale told by an insomniac who doesn't know when he's asleep, Fight Club takes things one step beyond into new realms of dissociation and movie mindfuck. Suffice to

16

“Just like Independence Day!”

say viewers might wonder just what they can trust: Is Tyler Durden projecting this movie? And just how reliable is this flipped-out narrator anyway? (Smith, 1999, par. 7)

This component of indeterminacy emerges strongly in the

movie’s apocalyptic ending. The apocalyptic ending is not

designed to generate fulfillment in the audience, but instead to

disturb and to move. Fight Club departs “from the cookie-cutter

mode of most studio releases. [The movie] refuses to untangle

narrative ambiguities or to provide convenient signposts to guide

viewer interpretation” (Crowdus, 2000, par. 10). At the end, Jack

“kills” his double personality Tyler, but he is unable to stop

Project Mayhem, namely the destruction of the headquarters of the

major credit card companies (figure 1).

While in Independence Day we have a classic happy-ending (the

aliens are defeated and the world-saviors can return to their

women1), the ending of the Fight Club is instead open to multiple

interpretations:

Fight Club engages and challenges moviegoers on an intellectual as well as an emotional and visceral level, refusing to spoon-feed them an easily digestiblemoral or lesson, instead insisting that viewers think

1 The choice of words here is intentional and introduces the topic of section four.

17

“Just like Independence Day!”

through for themselves the many provocative themes and issues it broaches. (Crowdus, 2000, par 11)

3) Design versus Chance. The characters in Independence Day

act in a rational fashion. Their problem-solving process is

linear: Ideation of a strategy, elaboration, and implementation.

Coordination and control must be assured before the main

characters are able to defeat the aliens. The importance of

chance is minimized.

Let us consider the way the characters behave in the final

battle. The beginning of the battle is marked by a speech to the

troops a redeemed President Whitmore, a former Gulf War pilot,

who symbolically shed his weak politician persona in favor of

that of a warrior2—“I’m a combat pilot, Will. I belong to the

air,” he says to a worried general. In that moment, he rises to

become a charismatic action leader.

The plan devised by the heroes is twofold. First, it

requires that a small ship--with Captain Hiller and the computer

whiz Levinson on board--penetrates the body of the mothership to 2 The parallels with the experience of President George W. Bush are rather astonishing. President Bush won the 2000 Presidential elections without winning the popular vote. His presidency was therefore expected to be rather weak. Instead, after 9/11 he emerged as a charismatic leader who is resolute to wage “war on terror” (Bligh, Kohles, & Meindl, 2004; Eisman, 2003; Kellner,2003).

18

“Just like Independence Day!”

upload a cyber virus that will neutralize the invisible shields

that protect the alien ships on the Earth. Once the protection

shields are down, a worldwide attack promoted and led by the

Americans is finally able to destroy the alien ships on Earth.

The cinematographic editing of these last scenes is

functional in showing the complexity of the perfect mechanism

created by the heroes. The camera continuously shifts back and

forth from the actions inside the mothership, the activities

around the Americans’ headquarters, and the attacks carried out

by the British troops in the Middle East3, by the Chinese, and by

the Russians.

The narrative of Fight Club emphasizes instead chance and

chaos. Since the plot is narrated in first-person, the audience

shares the surprises, confusion, and enlightens experienced by

Jack. Jack is not aware of the details of “Project Mayhem,” which

his double personality Tyler is plotting. From an organizational

perspective, Tyler also exemplifies the leadership style of

postmodern leaders (Wheatly 1999). Like in a “chaos game” where

3 One can wonder why the British troops are deployed at this location instead of, say, the United Kingdom. Does it reflect a logic of “masculine protection”(Young, 2003) to justify once again colonialism?

19

“Just like Independence Day!”

“complex structures emerge over time from simple elements and

rules and autonomous interaction” (Wheatley, 1999, p. 127), the

groups of fight clubs around the United States have in common a

simple set of rules set by Tyler4. Once a fight club has been

established, it develops itself autonomously, self-organizing its

own activities5.

Only Tyler understands the big picture behind the fight

clubs. At the same time, Tyler himself is subject to the rules

that he has established: In Fight Club, leaders hold neither a

higher rank nor an untouchable authoritative position. For

instance, when Jack finally realizes the ultimate goal of

“Project Mayhem,” he goes to a police station to expose the plan.

Three policemen, secretly members of a fight club, confront him.

They recognize that he is their spiritual leader (“Sir, you are a

hero. We really admire you”), since Jack and his second

4 “The first rule about fight club is you don’t talk about fight club;” “The second rule about fight club is you don’t talk about fight club;” “When someone says stop, or goes limp, even if he’s just faking it, the fight is over;” “Only two guys to a fight;” “One fight at a time;” “No shirts, no shoes;” “The fight goes on as long they have to;” “If this is your first nightat fight club, you have to fight.”5 Interestingly, fight clubs exemplify what the organizational form of Al Qaeda is believed to be. This terrorist organization is constituted by self-managing cells. Its leadership does not provide cells with direct orders but only with general directions and broad targets. In turn, the cells independently develop their action plans (Bergen, 2002).

20

“Just like Independence Day!”

personality Tyler are the same person in their eyes. Nonetheless,

they are determined to subject him to the procedure of castration

that everyone who mentions the existence “Project Mayhem” must

undergo.

4. Genital/Phallic versus Polymorphous/Androgynous. The

subtext of Independence Day contains clear phallic metaphors

(Rogin, 1998) and imageries of vagina dentata6 (Hobby, 2000). The

list of examples is extensive. First, the small ship with Hiller

and Levinson on board penetrates the mothership, “which opens up

her giant V-shaped orifice to invite their tiny projectile

inside” (Rogin, 1998, p. 57). The stated goal of their mission is

to “plant a virus into the mothership.” Also, during the final

battle, one of the fighter pilots, who was the supposed victim of

sexual abuse perpetuated by the aliens, takes his revenge by

flying inside the enemy space ship, shouting: “All right you

alien assholes! In the words of my generation, up yours!” The

vagina dentata imagery appears in the destruction scenes:

The aliens' mother ship gives birth to smaller ships that resemble huge vagina dentata hovering above all ofthe world's major cities. Washington D.C.'s huge

6 The vagina dentata is a mythology according to which some females have teeth intheir genitalia that are used to castrate their partners (Hobby, 2000).

21

“Just like Independence Day!”

phallic structures, shot from an extremely low angle, appear erect and ready to rape the huge vaginal spacecraft. However, … the viewer sees the daughters ofthe mother ship destroy these phallic monuments.(Hobby, 2000, p. 52)

Let us now consider the three major female characters in the

movie--the wife of the president, Hiller’s partner, and

Levinson’s former wife--and their relationships with their

partners. According to Rogin (1998), “women are … restored to

supporting roles in this supposedly politically correct film. The

three career professionals with whom the film begins are re-

subordinated to their husband by its end” (p. 44).

Right before dying, the energetic and politically involved

first lady confides to her husband her remorse for not having

surrendered to his desire to return home immediately after her

business trip, while he was worried for her safety. With regard

to the relationship between Hiller and his partner, a former

stripper, the movie suggests that their de facto union is not

enough and must be cemented with a marriage to make her an

“honest woman:”

Without the sanction of that piece of paper, a proper church (or in this case chapel) wedding, and the witness of no less a Big Daddy than the President of

22

“Just like Independence Day!”

the United States, actions and relationships mean nothing. (Dowell, 1996, par. 5)

The relationship between Levinson and his ex-wife, an

ambitious presidential press secretary who sacrificed family for

career, also reflects the pattern of “re-subordination” that

Rogin (1998) has identified. At the beginning of the movie, she

refuses to listen to her ex-husband, causing the death of

millions of people. Later, Levinson’s ex-wife re-pledges herself

to her man. At the end, Levinson can boast his new, regained

virility by symbolically smoking a cigar (a phallic form), while

his wife acts as a “conformist cheerleader who jumps into the

arms of [her] big, strong [man] who saved the earth” (Hobby,

2000, par. 53)

In short, the subtext of Independence Day strongly implies

male power over women and constitutes a phallic celebration of

virile virtues. Parenthetically, it should also be noted that

none of the brave fighter pilots in the final battle are women,

and that the only gay character dies during the initial,

catastrophic “Judgment Day” on day one (Hobby, 2000; Rogin,

1998). In addition, war is the right occasion for Levinson and

23

“Just like Independence Day!”

Whitmore to rediscover their virile qualities, while the group of

pacifists that cheers the arrival of the alien ships is the first

to be annihilated by the aliens. From a gendered perspective,

Hobby (2000) summarizes the moral of the movie in one sentence:

“Stand by your man and shut up” (par. 53).

Critics have taken opposite stands on Fight Club. For

instance, Giroux (2001) recognizes that the movie may offer a

critique of late capitalistic society. However, he argues that

this critique is limited only to the traditional notion of

masculinity. Therefore, Giroux (2001) accuses Fight Club of

functioning as a dangerous “public pedagogy,” which reflects and

reinforces “deeply conventional views of violence, gender

relations, and masculinity” (p. 6).

Clark (2001) suggests instead that Giroux probably missed

the specific tone of the movie. According to Clark (2001), “it is

possible to argue that Fight Club’s satirical edge helps make

associations of masculinity and violence more visible and even to

critique them” (p. 416). Crowdus (2000) also takes position

against the critics, who labeled the movie as “ugly,” “stomach

churning,” “morally repulsive,” “dangerous,” and “macho porn.”

24

“Just like Independence Day!”

These critics usually condemn the numerous violent scenes and

accuse them of functioning as “a mindless glamorization of

brutality, a morally irresponsible portrayal, which they feared

might encourage impressionable young male viewers to set up their

own real-life fight clubs in order to beat each other senseless”

(par. 13). According to Crowdus (2000),

glamorization was definitely not what they had in mind,however, since they consciously chose to avoid the conventionally stylized and physically sanitized barroom fist fights, choreographed like raucous dance routines …The far more realistic melees in Fight Club areinstead characterized by a lot of awkward grappling, wild roundhouse swings, head butting, kneeing, headlocks, low blows, and other amateurish wrestling maneuvers. (par. 14)

The cuts and bruises caused by a fight do not easily

disappear from the faces of the protagonists. For instance, Jack

is reproached several times by his boss at work because of Jack’s

indecorous appearance. Also, the fights do not end with a winner

and a loser who must prove his submission, but instead with an

intimate, almost homoerotic hug, where it is impossible to

distinguish winners from losers. Even Jack, the unwitting leader

of the fight clubs, haphazardly loses a fight against Bob, his

friend with huge, sweaty “bitch boobs” [sic]. The defeat does not

25

“Just like Independence Day!”

taint his leadership. Using Jack’s words, “Fight club was not

about winning or losing. When the fight was over, nothing was

solved, but nothing mattered.”

Moreover, the fight scenes are far from senseless. Instead,

“the filmmakers provided a comic or dramatic context for every

fight, with each bout functioning in terms of character

development or to signal a key turning point in the plot”

(Crowdus, 2000, par. 15). The most violent scene of the movie is

significant in this regard. Jack increasingly feels jealous

towards a new fight club member who is building a close

relationship with Tyler. A fight between Jack and the new member

offers the opportunity for revenge. Jack breaks Fight Club Rule

#3 (“When someone says ‘stop,’ or goes limp, the fight is over”)

and disfigures his rival. The crowd observes the horrific scene

in a state of shock. At the end of the fight, Tyler looks down at

“psycho-boy” Jack in disapproval and makes sure that the victim

is taken to the hospital, while Jack confesses: “I felt like

destroying something beautiful.” This scene, which arouses more

repulsion to violence than glamour, manifests the complex and

26

“Just like Independence Day!”

twisted relationship between Jack and his second personality

Tyler and cannot be considered “gratuitous.”

In Fight Club, huge doses of irony surround what Giroux (2001)

describes as exaltation of male virility. At the beginning of the

movie, the protagonist tries to overcome his insomnia in a club

for castrated victims of testicular cancer. He finally finds rest

in the abnormal breast of one of them, Bob. Jack is portrayed as

an asexual, almost impotent person, and in one occasion he

complains to be “neutral” in Marla’s eyes. The narrator develops

a homosexual attraction to Tyler and he is particularly jealous

of Marla, who has “spectacular” sexual encounters with Tyler in

parody of hypersexual machismo. In the movie, there are several

references to the act of castration. However, in Fight Club

castration is not the result of an attack of a vagina dentate like

in Independece Day, but it reflects the male characters’ obsessive

attention to their genitalia However, these y are not the result

of the attack of a vagina dentata, but are instead the.

In regard to the terrorist activities promoted by Tyler,

Jack expresses several times his criticisms and disapproval

(Clark, 2001; Crowdus, 2000). He nicknames the members of the

27

“Just like Independence Day!”

“Project Mayhem” group as “space monkeys,” because they are

always busy with the mindless mouthing of slogans like “In Tyler

we trust” or zen-like quotes like “You are not beautiful and

unique as a snowflake.” Tyler’s charismatic leadership is also

portrayed as problematic. According to Crowdus (2000), “as Tyler

proselytizes to his troops through a bullhorn, it is clear that

[his followers] have become as manipulated and dehumanized by

their leader as they ever were by the corporate civilization from

which he is trying to rescue them” (par. 18).

The “Falling Towers”

After having outlined the main ideological differences that

underlie the narratives of Independence Day and Fight Club, this

section focuses on the ‘falling tower’ scenes that appear in both

movies (figure 1). Two aspects of these are examined: 1) their

symbolic value and 2) the position of the scenes in the overall

plot.

1) Symbolic value of the falling towers. The destruction

scene from Independence Day in figure 1 marks the beginning of the

aliens’ attack on planet Earth. The goal of the attack is not

just the destruction of single monuments, but rather the

28

“Just like Independence Day!”

annihilation of entire cities, as the numerous panoramic shots

display. Single shots of famous monuments have only a spectacular

function. They are intertextual allusion to mythological

locations in the cinematographic imaginary: The Empire State

Building made famous by King Kong (Guillermin, 1976); a shot of a

half-submerged Statue of Liberty, a clear reference to The Planet of

the Apes (Shaffner, 1968); and the White House, which in the

recent years has been portrayed in numerous films, such as Air

Force One (Petersen, 1997), and the popular TV series The West Wing

(Sorkin & Schlamme, 1999). Following Ott & Walter’s (2000)

categorization, these intertextual references function as

“creative appropriation:” The director integrated fragments of

similar, catastrophic movies into Independence Day to pay a tribute

to his sources of inspiration.

With regard to the aliens’ motives, Independence Day offers a

rather insignificant explanation. “Why do you attack us?” asks

President Whitmore to a captured alien. After a telepathic

contact, he comes to realize that the aliens made a point in

spoiling and destroying the entire universe, Earth included. In

29

“Just like Independence Day!”

other words, following the strict rules of the genre, the aliens

in Independence Day are just playing their stereotypical role.

The towers in Fight Club have, instead, a deep and

sophisticated symbolism, and the motivation behind their

destruction is also complex and controversial. The towers host

the headquarters of some major credit card companies. The choice

of these targets for “Project Mayhem” is consistent with the

evolution of Tyler’s thought, which was growing increasingly

radical and critical towards capitalistic institutions—as

exemplified slogans such as “Reject the basic assumptions of

civilization, especially the importance of material possession,”

with which he was brainwashing his followers. According to

Tyler’s contorted logic, the destruction of the credit card

companies means putting everyone’s debt “back to zero,” a

situation that he believed would have given a deadly hit to one

of the major pillars of the capitalist structure.

Tyler’s justification for his actions has nonetheless an

element of sincere idealism. In many occasions during the movie,

he points out the dangers of consumerist society, which offers a

bogus value system that eventually enslaves its members. The risk

30

“Just like Independence Day!”

of conformism and crude materialism in Western culture is

portrayed at the beginning of the movie, when Jack is browsing an

Ikea catalog, pondering which dining room set “defines me as a

person.”

2) Position of the scenes in the overall plot. In

Independence Day, the destruction of the towers disrupts the

initial status quo. From that moment on, the goal of the heroes

is to return to the initial situation. Their efforts are based on

values such as traditional male values (already discussed in the

dyad “Phallic versus Polymorphous/Androgynous”) and patriotism.

The title of the movie itself is significant from this

perspective. Geoff (1999) notes: “The fact that [Independence Day]

is set on the date celebrated for the signing of the Declaration

of Independence reinforces the potential of the events both to

question--and to provide opportunity to revive--hallowed American

values” (par. 10).

The victory over the alien invaders reconfirms the global

dominance of the United States, thanks to its charismatic

leadership (President Whitmore), its genial scientific apparatus

(David Levinson), and the bravery of its military (Captain

31

“Just like Independence Day!”

Hiller). In short, from the audience’s perspective, Independence

Day satisfies on many levels. On one hand, its narrative and its

conclusion solve all the dramatic elements in an unambiguous way,

marking a clear victory of the “good guys.” On the other hand,

the subtext of the movie reassures the basic values of its

American audience and reconfirms the rectitude of those values,

as Bob Dole’s quotation at the beginning of this paper

exemplifies.

In Fight Club, the ‘falling towers’ scene is at the very end

of the movie. The charismatic Tyler was abusing his charisma to

manipulate his followers. The destruction of the credit card

system may represent a solution to shake the oppressive

capitalist system, but are mayhem and abusive charisma a fair

price to pay for emancipation? Since the movie ends with the

destruction of the towers, the interpretation of the movie and

the decision of “what happens next” are left to the audience. As

Clark (2001) observes, “many of the reviewers of Fight Club have

noted that the film has prompted debate” (p. 418). After

witnessing the bare-knuckle fights in the movie, it is time for

the audience to engage “in another kind of fight—to continue

32

“Just like Independence Day!”

appealing to the more intellectual pleasures of rhetoric through

critical argument” (p. 419). Instead of uncritically reassuring

basic values in its audience, Fight Club stimulates the audience to

take sides, to envision a new society, and to consider the risks

and the price that a change may involve.

Independence Day and the Logics of the Bush’s Administration

Two distinct ideological subtexts emerge from the analysis of the

two movies. On one hand, there is Independence Day, whose plot

follows a traditional, pre-determined archetype. Its characters

are busy designing carefully crafted action plans to reaffirm

rightfulness and rationality over a chaos that has been caused by

irrational hatred. In a clear-cut Manichean world of Good versus

Evil where a clear distinction divides the innocent victims (the

Self) from the guilty offenders (the Other), the heroes prevail

by reaffirming conservative values, such as patriotism and

patriarchy. Only those who embrace these values survive. No

ambiguities are left at the end of the movie that reconfirms the

rectitude and the necessity of hegemonic role of the United

States.

33

“Just like Independence Day!”

In Fight Club, chaos and ambiguity are the principal themes of

the movie. The plot of the movie defies linearity and its genre

cannot be easily categorized. Its characters are moved by chaotic

and sometimes pathologic impulses. Instead of heroes, the

narrative of Fight Club is populated by antiheroes that have lost

every certainty. Their existential crisis involved not only their

gender and sexual orientation, but also their identity in their

entirety--the Self and the Other cohabit in the same body. Its

anti-heroes wage a fight against an oppressive system of bogus

values to find themselves in another one. The line between

victims and offenders is irremediably blurred. The end of the

movie is not intended to reaffirming the importance of any value

system, but only to stimulate discussion and reflection.

Intertextual references to Independence Day are therefore not

only an association between mere images (such in figure 1), but

are also functional in framing the events on 9/11 within a

consistent ideological structure. This structure provides a

definition of the problem: Bin Laden like the aliens attacked the

homeland moved by irrational hatred; the Other is the enemy, we

are innocent victims. It also provides the remedy: Through the

34

“Just like Independence Day!”

reaffirmation of values, such as patriotism and patriarchy, the

Other will be defeated; War is the right path to follow to

reaffirm these values because those who do not conform--such as

the pacifists--will be annihilated.

Some may argue that the intertextual references to

Independence Day are merely unintentional and that they make more

sense because that movie is more popular than others, such as,

say, Fight Club. At a closer look, this argument would not hold. I

would rebut that the images of Independence Day may capture the

catastrophic aspects of the events of 9/11 but completely misses

the symbolism of the Work Trade Center, which was one of the

major symbols of the American economic power (Kellner, 2003).

This would be indicative of a emphasis on emotional aspect of the

events (Eisman, 2003). On top of this, it is interesting that

these intertextual allusions refer to a movie that portrays the

enemies’ motives as irrational and only basely on hatred. In the

same way, American mainstream mass media have been criticized to

have presented Bin Laden’s motives in an oversimplified way and

in a historical vacuum (Eisman, 2003; Kellner, 2003; Pedersen,

2003).

35

“Just like Independence Day!”

Instead, I propose a different interpretation of the

function of these intertextual references to Independence Day. I

argue that those references should be observed having as

background the “sense of rallying around the president” and the

“unanimous call of war” (Eisman, 2003, p. 58) that filled both

the television and the printed news in the U.S. These

intertextual are instead indicative of the preferred status that

the government’s interpretation of the events held among the U.S.

mainstream media (Entman, 2003, 2004) and are vested with an

hegemonic function:

Whether the news media’s bias stemmed from patriotism, a sensitivity to their audience or their financial backers, or was the of ‘suggestions’ from the government, the end of the result was the same—Americanmainstream news had degenerated almost completely into blatant propaganda. (Eisman, 2003, p. 65)

To show the ideological congruence between the Bush

administration and the narrative of Independence Day, in this last

section I focus my attention on two key speeches delivered by the

U.S. President George W. Bush. The first one (Bush, 2001b) is an

‘address to the nation’ and represents the first official comment

of the White House after the tragedy. The second speech (Bush,

36

“Just like Independence Day!”

2001a) has been delivered at the Congress and can be seen as the

‘ideological manifesto’ of the administration’s “war against

terrorism,” later developed in the doctrine of “pre-emptive war”

(Kellner, 2004). and these speeches are particularly relevant

because they have been functional for the Bush administration to

establish a successful rhetorical discourse around the events of

9/11 to the adminstration’s advantage (Murphy, 2003). Bush’s

rhetorical strategies have already been detailed in several

analyses (Agathangelou & Ling, 2004; Bligh et al., 2004; Kellner,

2004; Murphy, 2003) and in this section I emphasize the major

parallels with Independence Day.

Similarly to the Manichean world represented in Independence

Day, Bush (2001a; 2001b) strategically uses the word ‘evil’ to

frame the events of 9/11 as contraposition of Good versus Evil.

For instance, the terrorist group al Quaeda is described as always

intend in plotting ‘evil’ (par. 16). In this Manichean world, it

is easy to recognize friends from foes: “Every nation, in every

region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or

you are with the terrorists” (par. 30).

37

“Just like Independence Day!”

As in the narrative of Independence Day, the terrorist attack

has broken an initial status quo, namely “the normal course of

events” (Bush, 2001a, par. 2), and the success against the

enemies means a return to the initial conditions: “it is my hope

that in the months and years ahead, life will return almost to

normal. We'll go back to our lives and routines, and that is

good.” (Bush, 2001a, par. 51).

As the aliens, the terrorists seem to be moved by envy and

hatred where innocent victims and cruel offender are clearly

distinct. In his first speech, Bush (2001b) states that “America

was targeted for attack because we're the brightest beacon for

freedom and opportunity in the world” (par. 4). In the second

speech, he further explains: “Americans are asking, why do they

hate us? They hate what we see right here in this chamber--a

democratically elected government. Their leaders are self-

appointed. They hate our freedoms--our freedom of religion, our

freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree

with each other” (Bush, 2001a, par. 24).

While the attack are motivated by “the very worst of human

nature” (Bush, 2001b, par. 5), civilization will defeat

38

“Just like Independence Day!”

radicalism: “This is civilization’s fight. This is the fight of

all who believe in progress and pluralism, tolerance and freedom”

(Bush, 2001a, par. 35) and “The civilized world is rallying to

America's side” (p. 37). If the attaches were intended to

“frighten our nation into chaos” (Bush, 2001b, par. 2), to impose

“radical beliefs on people everywhere” (Bush, 2001a, par. 14) and

as in Independence Day the enemy will be defeated by if the nation

hold itself strictly to the core American values. According to

Bush, “Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest

buildings, but they cannot touch the foundation of America”

(Bush, 2001b, par. 3) and “I ask you to uphold the values of

America, and remember why so many have come here. We are in a

fight for our principles, and our first responsibility is to live

by them” (Bush, 2001a, par. 38).

Traditional male virtues (Agathangelou & Ling, 2004; Young,

2003) are the pillar for the action. Bush defines the country as

“strong” in both speeches, as well as its financial institution

that have not been ‘castrated’ by the attack: “Our financial

institutions remain strong, and the American economy will be open

for business” (2001a, par 9). Therefore, the government can still

39

“Just like Independence Day!”

offer ‘protection’ and ‘security,’ another masculine trait

(Young, 2003). For instance, Bush (2001a) states: “We will take

defensive measures against terrorism to protect Americans” (par.

32) “I will not relent in waging this struggle for freedom and

security for the American people” (par. 54). And finally, like in

Independence Day, war is the only viable solution to solve the

conflict. “Our military is powerful, and it’s prepared,” states

Bush (2001b, par. 6). In his address to the Congress, he explains

further: “Tonight, a few miles from the damaged Pentagon, I have

a message for our military: Be ready. I've called the Armed

Forces to alert, and there is a reason. The hour is coming when

America will act, and you will make us proud” (Bush, 2001a, par.

33).

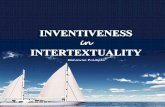

Figure 2. President Whitmore in Independence Day and President Bush on thecarrier USS Abraham Lincoln

40

“Just like Independence Day!”

Conclusions

On May 1, 2003, President Bush on board of the U.S. Navy S-3B

landed on the deck of the carrier the USS Abraham Lincoln off the

California cost to deliver a speech to the nation that declared

that major combat operation in Iraq. Behind him, a banner

emphatically stated in big fonts: “Mission accomplished.” Like

the President-warrior Whitmore of Independence Day (figure 2), Bush

can celebrate the success of the “Operation Iraqi Freedom” among

his troops.

Unlike Whitmore, however, Bush’s victory is far from being

complete: Far more troops died and were wounded after May 1, 2003

than during the war itself (Gordon, 2004). In the meantime, the

Iraqi population is caught between the insurgents and the

occupation forces and the tally of the civilian deaths is in the

10,000 to 15,000 range (Onishi, 2004).

Many voices are raising to discuss not only the way the

Iraqi war has been prepared, but also its rationale (Clarke,

2004; Gordon, 2004; Woodward, 2004). The hegemonic ascent of the

Bush administration’s interpretive framework may have represented

a short term solution to the crisis of 9/11. To be sustained,

41

“Just like Independence Day!”

this framework require incessant militarization and the promotion

of a culture of fear (Agathangelou & Ling, 2004; Young, 2003).

Also, it requires glossing over the deep motivations behind the

conflict Bush’s belief that “America was targeted for attack

because we're the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in

the world” (Bush, 2001b, par. 4) sound more than a crowd-pleaser

than a reasonable justification.

Without justifying the actions of the terrorists and the

blood shed that they caused, I argue that the Bush administration

has systematically renounced to understand the deep motivation

behind the attack, maybe because this quest may have prompted a

reconsideration of the American foreign policy, which has a less-

than-stellar track record (Chomsky, 2001; Eisman, 2003), and the

identification of alternative plans of actions. As Entman

observes (2003), the definition of an issue “often virtually

predetermines the rest of the frame, and the remedy, including

the support of (or opposition to) actual government action” (pp.

417-418). But when Bush (2001a) states, “Either you are with us,

or you are with the terrorists” (par. 30), every voice, which

discusses the moral validity of the deliberation of the political

42

“Just like Independence Day!”

elites, will be labeled as “pro-terrorists,” “pro-Taliban,” “Pro-

Saddam,” or simply “anti-patriotic.” McQuail (2000) notes that

“hegemony tends to define unacceptable opposition to the status

quo as dissident or deviant.” (p. 97).

In this paper, the hegemonic process has been observed

through an analysis of the narratives of a popular cultural

artifacts and the way one of these narrative been functional in

contributing the ascent and reinforcement of the Bush

administration’s ideology. The notion of the ‘hegemonic’ function

of intertextuality appears to be a useful interpretive tool in

promoting synergies between cultural studies and established

media approaches, such as framing analysis (Entman, 2004). At the

same time, this perspective is consistent with the program of

cultural studies and generates insights that are able to promote

a “more democratic and egalitarian social order” (Kellner, 1995,

p. 100).

43

“Just like Independence Day!”

Appendix 1- SYNOPSESIndependence Day. On July 2nd, alien sources suddenly appear in the skies announced by a mysterious signal, stationing above the World’s major cities. Several attempts to communicate with the aliens go nowhere. David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum), an ex-scientist turned cable TV technician, realizes that the mysterious signal is a secret code that the aliens are using to coordinate a massive attack against major targets around the globe. As Levinson predicted, on the evening of July 2nd, the aliens began to transform entire cities into debris. The President of the Unites States, Thomas J. Whitmore (Bill Pullman), alerted by Levinson, escapes just in time before the annihilation of the White House. On July 3rd, American forces wage a brave but disastrous counterattack by air. Captain Steven Hiller (Will Smith), a marine officer, is the only survivor. In the meantime, Whitmore and Levinson take shelter in the infamous hangar of Area 51, New Mexico. Levinson devises a strategy that is expected to overcome the aliens’ defenses. In the meantime, Hiller joins the Whitmore and Levinson in Area 51. On July 4th, Levinson and Hiller penetrate with a small space ship—secretly preserved in Area 51 since the 1940ies--into the alien mothershipto insert a computer virus that is able to neutralize the aliens’defenses. President Whitmore leads a successful world-wide attackagainst the defenseless aliens. The invaders are defeated and decide to leave Earth.

Fight Club. The movie narrates the story of Jack (Edward Norton),a recall coordinator for a major U.S. auto firm. Jack is a momentof growing restlessness toward his consumeristic lifestyle. In parallel with his existential crisis, Jack suffers a period of insomnia, which he temporarily overcomes by attending support groups for terminally ill people. When Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter) begins attending the same supports groups, she breaks the new Jack’s new found equilibrium. During a business trip, he meets the eccentric and charismatic Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt). Back at home, Jack discovers that his apartment has been destroyed by an explosion, therefore he asks Tyler for hospitality. The two form a tight friendship and organize a “fight club,” in which a growing number of men release their

44

“Just like Independence Day!”

frustrations through bare-hands fights. Marla, saved by Tyler during a suicidal attempt, eventually becomes his lover at Jack’schagrin. One day, Tyler selects a group of fight club’s members to develop “Project Mayhem.” The new group, with strong anarchic tendencies, is dedicated to symbolic attacks against multinational corporations. However, Jack suspects that Tyler is planning something on a bigger scale and he decides to investigate Tyler’s moves. He discovers that more fight clubs have been formed around the country. In a bizarre plot twist, Jack also realizes that Tyler is in reality his second personality. Eventually, Jack symbolically “kills” Tyler but he is unable to prevent the achievement of the ultimate goal of “Project Mayhem:” The destruction of the headquarters of some major credit card companies.

45