Journal for Scientists and Engineers - SAFETY ENGINEERING

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Journal for Scientists and Engineers - SAFETY ENGINEERING

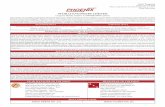

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ

FACULTY OF OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY

Center for Technical Systems Safety

Center for Distribution of Developmental Strategies

Journal for Scientists and Engineers

SAFETY ENGINEERING Naučno stručni časopis

INŽINJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

No1 (2011)

Niš, October 2011

Journal for Scientists and Engineers SAFETY ENGINEERING Naučno stručni časopis INŽINJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

Izdavač I Publisher Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu / Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš Centar za bezbednost tehničkih sistema / Center for Technical Systems safety

Glavni urednik / Editor‐in‐chief

Dr Dejan Krstić

Urednici / Editors

Dr Ivan Krstić Dr Srđan Glišović Dr Vesna Nikolić

Redakcijski odbor /Editorial board (alphabetical order) dr Andres Carrnion Garcia, Technical University of Valencia, Spain dr Boris Đinđić, Medicinski fakultet u Nišu, Srbija dr Branislav Anđelković, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Dejan Petković, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Desimir Jovanović, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Đordje Ćosić, Fakultet tehničkih nauka, Novi Sad, Srbija dr Dragan Mitić, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Dusan Sakulski, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, DiMTEC, Bloemfontein, South Africa dr Dušan Sokolović, Medicinski fakultet u Nišu, Srbija dr Ivana Banković Ilić, Tehnološki fakultet u Leskovcu, Srbija dr Jirí Pokorný, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Czech Republic dr Joseph Aronov, VNIIS Mosow, Russia dr Jovica Jovanović, Medicinski fakultet u Nišu, Srbija dr Katarína Senderská, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Košice, Slovakia dr Ljiljana Živković, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Ljubiša Papić, Tehnički fakultetu u Čačku, Srbija dr Miomir Stanković, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu , Srbija dr Mirjana Vidanović, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Mirko Marič, Fakultet za menadžment, Kopar, Slovenija dr Nenad Živković, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu , Srbija dr Noam Lior, University of Pennsylvania, USA dr Susana San Matias, Technical University of Valencia, Spain dr Suzana Savić, Fakultet zaštite na radu u Nišu, Srbija dr Vera Marković, Elektronski fakultet u Nišu, Srbija dr Vlada Veljković, Tehnološki fakultet u Leskovcu, Srbija dr Wolfgang Mathis, Institut für Theoretische Elektrotechnik, Hannover, Germany dr Zoran Keković, Fakultet Bezbednosti u Beogradu, Srbija

Tehnički urednik / Technical editor Rodoljub Avramović

Lektor / Proof‐reader Dr Nataša Šelmić‐Milosavljević Aleksandra Petković Časopis izlazi tromesečno / The journal is published quarterly Štampa / Press M KOPS Centar

From Editor’s desk

Blessed is the one who knows that he does not know, but would like to learn. A proverb

Development of technologies and technical disciplines has improved the quality of human life on the one hand, but brought about human influence on the environment on the other. Generally, this impact on the environment represented conscious and unconscious threat to its quality. The need to protect the man in working and living environment, and the environment itself is the goal of the employees at the Faculty of Occupational Safety. This magazine has been developed as a need to present new ideas in the field of occupational and environmental safety to scientific and professional community. The idea was launched by the Centre for Technical Systems Safety and Center for Distribution of Developmental Strategies of the Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš. Our goal is to promote the journal to become a correlation between the scientific and professional institutions and individuals working towards the improvement of work process and the quality of life.

I sincerely hope that the authors will manage to provide all necessary information to the readers through the articles of high technical and scientific quality that will be published in the journal Safety Engineering.

Blago onome ko zna da ne zna, a hoće da zna. narodna poslovica

Razvoj tehnologija i tehničkih disciplina unapredili su kvalitet čovekovog života sa jedne strane ali i doveli do intervencije čoveka u životnoj sredini. Uglavnom je ovo delovanje na životnu sredinu značilo svesno i nesvesno ugrožavanje njenog kvaliteta. Potreba da se zaštiti čovek u radnoj i životnoj sredini i sama životna sredina je ishodište zaposlenih na Fakultetu zaštite na radu. Časopis koji je pred vama je nastao kao potreba da se naučnoj i stručnoj javnosti izlože nove ideje u oblasti zaštite radne i životne sredine. Ideja je potekla od strane Centra za bezbednost tehničkih sistema i Centra za distibuciju razvojnih strategija, Fakulteta zaštite na radu u Nišu. Želja je da časopis bude sprega između naučnih i stručnih institucija i pojedinaca u napredenju bezbednosti radnog prcesa i samog kvaliteta života.

Iskreno sa nadam, da će autori u radovima visokih tehničkih i naučnih kvaliteta koji budu objavljivani u časopisu Safety engineering pružiti potrebne informacije čitaocima.

On behalf of the editors

Doc. Dejan Krstić, PhD

Contents

Scientific Articles

Petr Kučera, Jiří Pokorný Fire Engineering Approach of People Evacuation Assessment With a Practical Demonstration .......................................... 1 Boris Preshelkov, Rosen Borisov, Radoslav Kartov, Milan Blagojević A Study of Determening Safe Distances Between Ceramic Infrared Gas Heaters and Combustible Materials............... 7 Darko Zigar, Desimir Jovanović, Martina Zdravković CFD Study of Fire Protection Systems in Tunnel Fires ..... 11 Goran Janaćković, Suzana Savić, Miomir Stanković Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Occupational Safety Management Systems ......................................................... 17 Milan Protić, Dragan Mitić, Velimir Stefanović Wood Pellets Production Technology ................................ 23 Tomáš Chrebet, Karol Balog, Jozef Martinka, Ivan Hrušovský Monitoring of the Cellulose Pyrolysis in a Modified Electrically Heated Hot Air Furnace ................................. 27

Professional Articles

Miljenko Vrbanec, Franjo Magušić Application of Biometric Systems in Care ......................... 35 Ivan Krstić, Dejan Krstić, Ana Kusalo Analiaza pokazatelja za procenu profesionalnog rizika .... 45

Reviews of publications

Vesna Nikolić, Nenad Živković Bezbednost radne i životne sredine, vanredne situacije i obrazovanje ....................................................................... 59 Snežana Živković Uloga i značaj lica za bezbednost i zdravlje na radu u privrednim društvima u Republici Srbiji............................ 61

Intellectual property, review of technical solution

Miomir Stanković, Suzana Savić, Žarko Janković, Goran Janaćković, Dejan Krstić, Ivan Krstić, Srđan Glišović UpOl - Softverski sistem za evidentiranje otpada u lokalnim zajednicama ....................................................................... 63

Propagation Corner

ZAŠTITA U PRAKSI Časopis za zaštitu na radu, zdravstvenu, ekološku i zaštitu od požara ALEKSANDAR INŽENJERING D.O.O. Novi Sad, Srbija Prodaja i servis mernih instrumenata

Sadržaj

Naučni radovi

Petr Kučera, Jiří Pokorný Fire Engineering Approach of People Evacuation Assessment With a Practical Demonstration...........................................1 Boris Preshelkov, Rosen Borisov, Radoslav Kartov, Milan Blagojević A Study of Determening Safe Distances Between Ceramic Infrared Gas Heaters and Combustible Materials ...............7 Darko Zigar, Desimir Jovanović, Martina Zdravković CFD Study of Fire Protection Systems in Tunnel Fires......11 Goran Janaćković, Suzana Savić, Miomir Stanković Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Occupational Safety Management Systems .........................................................17 Milan Protić, Dragan Mitić, Velimir Stefanović Wood Pellets Production Technology ................................23 Tomáš Chrebet, Karol Balog, Jozef Martinka, Ivan Hrušovský Monitoring of the Cellulose Pyrolysis in a Modified Electrically Heated Hot Air Furnace .................................27

Stručni radovi

Miljenko Vrbanec, Franjo Magušić Application of Biometric Systems in Care ..........................35 Ivan Krstić, Dejan Krstić, Ana Kusalo Analiaza pokazatelja za procenu profesionalnog rizika .....45

Prikazi publikacija

Vesna Nikolić, Nenad Živković Bezbednost radne i životne sredine, vanredne situacije i obrazovanje ........................................................................59 Snežana Živković Uloga i značaj lica za bezbednost i zdravlje na radu u privrednim društvima u Republici Srbiji ............................61

Intelektualna svojina, prikaz tehničkih rešenja

Miomir Stanković, Suzana Savić, Žarko Janković, Goran Janaćković, Dejan Krstić, Ivan Krstić, Srđan Glišović UpOl - Softverski sistem za evidentiranje otpada u lokalnim zajednicama........................................................................63

Oglašavanje

ZAŠTITA U PRAKSI Časopis za zaštitu na radu, zdravstvenu, ekološku i zaštitu od požara ALEKSANDAR INŽENJERING D.O.O. Novi Sad, Srbija Prodaja i servis mernih instrumenata

UDC 355.247 : 629.4.042.5 : 519.876.2 Original article

Paper is presented at the "International Conference Safety of Technical Systems in Living and Working Environment", Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš, October 2011, Niš.

1 | Safety Engineering

PETR KUČERA1

JIŘÍ POKORNÝ2

1VŠB - Technical University

of Ostrava, Faculty of Safety Engineering,

Czech Republic 2Fire Rescue Brigade of the Moravian-Silesian Region,

Czech Republic

[email protected] [email protected]

FIRE ENGINEERING APPROACH OF PEOPLE EVACUATION ASSESSMENT WITH A PRACTICAL DEMONSTRATION Abstract: This article presents some of the possible ways of an examination of people evacuation by fire engineering methods. Application of described methods is illustrated in a practical example of an office object. The expansion of fire in a part of characteristic floor of high-rise office is simulated by the selected zone (CFAST) and field (FDS) fire models. Some of the results obtained by the simulation, especially smoke layer decrease in the area and cumulative gas layer temperature, represent limit criteria for examination of safe evacuation from the assessed area. The article is an example of possible application of combination of manual computational processes and fire models.

Key words: fire safety, evacuation, mathematical modelling. INTRODUCTION With increasing complexity of buildings (more complicated technical and technological systems that are conditioning their operation, and the increase in their area, height, more floors in the underground, more people, etc.) the increase of demands for risks assessment in term of fire safety also increases. In many cases, the application of national safety standards is problematic, almost unrealistic. The way out of these situations is application of more detailed evaluative procedures, fire engineering methods, which can be used as partial or complex evaluative instrument. This article presents one of the possible ways, when a part of the solution is based on the application of fire models. It also presents simplified computational processes connected to it. BASIC DESCRIPTION OF EXAMPLE The method of engineering procedure is applied to multifunctional high-rise object (administrative premises of this object) that are mostly formed by large-area offices, small conference rooms and spaces designed for documents storing. In the case of fire rise in high-rise objects, the principal aim is to prevent casualties and injuries, and thus ensure the possibility of safe evacuation of people from the object. Therefore, the chosen example concerned with the fire rise in the fire cell of office premises on the area 25 × 30m, situated in the 20th floor (see colour coded area in the fig. 1).

FIRE COURSE ASSESSMENT After the qualitative analysis, we have developed a scenario of fire in the kitchen during working time (simplified geometry of the assessing part of the floor is pictured in the fig. 2). There is a colour coded kitchen, denoting the centre of the fire scenario. The kitchen door of high-capacity office is open all the time. It is assumed that users of the object did not manage to extinguish the developing fire on time, so people have been endangered by smoke that will spread to the premises of the high-capacity office. Furthermore, we have assumed the effective function of fire dividing constructions, including fire shutter of openings equipped with self-closing device. Fire development, temperature course and smoke level in the assessed part of the object have been modelled according to the zone model CFAST (Consolidated Model of Fire Growth and Smoke Transport, version 6) [1] and field model FDS (Fire Dynamics Simulator, version 5) [2].

Figure 1. Simplified geometry of assessed part of the floor

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

The results showed that it is possible to characterize the initial phase of the fire by simple, time-dependent parabolic curve. The curve is known as t-quadratic fire curve, where the heat release rate is proportional to square power of time. The equation can be found in the following form:

(1)

For calculation of the value tg from quantities used in Czech technical standards can be used conversion relations, which are stated in the Annex H ČSN 73 0802:2009. For non-productive objects according to ČSN 73 0802 and consequential standards, the value tg is calculated using the fire load and the coefficient of burning rate:

(2)

In the case of the kitchen (p = 25 kg.m-2, a = 1) tg = 2000 / (1⋅ (25)0,5) = 400 s. The course of temperature and smoke layer decrease in assessed premises defined by both fire models can be seen in the Fig. 2 (in the case of FDS fire model, temperature and smoke layer level monitored always in room centres, in the height of 3m). The course of temperature increase and smoke layer decrease in the kitchen and large-area office are represented in the fig. 2.

Figure 2. Illustration of time course of the temperature and smoke layer decrease by models CFAST and FDS

From the curves acquired by both fire models (CFAST vs. FDS) it is obvious that the results are largely comparable. The result supports a presumption that zone models are in many cases very usable, especially when there is a need to acquire source information during situations with limited range of input information or lack of time space necessary while using field models. DESCRIPTION OF BASIC PRINCIPLES USABLE AT FIRE ENGINEERING ASSESSMENT OF EVACUATION During detailed assessment of evacuation is generally always efficient to determine the required safe escape time tc, which consists of partial time intervals:

(3)

Detection and alarm time td is usually split in two time intervals. In the fire detection time, which depends on the design of the device for the early fire detection (e.g.

electrical fire detection and fire alarm systems) or on noticing of fire by an user of the object. Second time period is the alarm time, during which is transmitted the information on fire rising to the users of the object either directly or through the warning signals. Activation of warning signalisation can be either immediate or with time delay. Time to start of evacuation tz consists of detection time, time needed for deciding (perception and processing the information) and time necessary for activities before leaving. Time of persons´ movement through the building tu is time since initiation of persons escape in the object to reaching safe place (e.g. open space). Through suitable calculation methods, it is possible to determine escaping time based on relatively simple relations. With increasing number and density of persons generally rises also complexity of evacuation. The density of persons can be expressed by equation:

(4)

2 | Safety Engineering

P. Kučera, J. Pokorný, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 1-6

Speed of movement and flow can be expressed in the interval from 0,54 persons.m-2 till 3,8 persons.m-2 by the equation [3]:

(5)

Capacity of escape route, also referred to as specific or total flow of persons, represents the number of persons evacuated in time unit by unit of width of escape route, eventually its whole width, and can be expressed by equations:

(6)

Time of movement through the building it is possible to determine by sum of time required for distance overcoming tu1 and time required for passage through the less suitable place on the escape way tu2:

(7)

While solving partial lengths of escape routes it is possible to determine time of persons movement through the building tu by adjustment of the original equation by Kikuja Togawa:

(8)

Analogical equation was presented in lit. [4] and it is also stated in standards of buildings fire safety in the Czech Republic [5]. Time needed for evacuation will be consequently compared with chosen criteria of acceptability. In the given case the criteria of acceptability chosen were unsmoked height of space of 2,5 m and limit temperature of gas layer of 200°C, which cumulates under the ceiling construction. From the previous paragraphs, it is obvious that time of movement through the building tu represents just one of the partial times characterizing required safe escape time tc. While assessing persons’ evacuation by fire engineering methods, there will be probably more often used the very required safe escape time tc which can provide more real image of persons evacuation time from the object and be one of the parameters for design of fire safety devices and arrangements. EVACUATION ASSESSMENT IN THE DEFINED PART OF THE OBJECT Principles for evacuation of persons assessment The following characteristics were among the most important data related to evacuation of people: • dispositional layout of single floors is simple and

well-arranged, • persons are in the visual contact,

• employees are in the productive age, average physical and psychical condition,

• presence of persons with limited movement ability

acquainted with the building,

rotection area,

ct is equipped with electric fire

the announcement of evacuation

will be systemically checked in the ourse of building operation (system of controls in the

etermination of persons movement time t by

nsity of persons in the assessing

Table 1. Input values for evacuation a nt

as t oor

is rare, persons unable of individual movement are not present,

• in the assessing part of the object, there are only persons

• persons are present only in day-time and wide awake,

• persons in assessing spaces are regularly educated in the fire p

• there is periodical fire alarm used for training in the object,

• the objesignalisation device (EFS) with emergency sound system,

• the EFS device works in the two-stage regime of fire alarm, whenby the emergency sound system is in the first stage of signalisation.

At assessing, it is supposed that defined constructional, technical and organisational arrangements will be observed in the course of construction. Fulfilment of defined conditions cregular intervals). D uthe detailed calculation In the following paragraphs, parameters of unprotected escape ways will be considered in the characteristic part of the object floor by the detailed calculation reflecting especially depremises [3], [6], [7]. The most significant input values vare shown in Tab.1.

ssessme in the sessed par of the fl

Room name Number of persons E (pe s) rson

Area A (m2)

Length of

escape r oute lu

Width of

escape ro ute B

(m) (m) Conference

room 67 100,0 12,5 1,6

Office section including 1,41147 636,9 26,0 separate offices,

kitchen and hall

Depending on density of persons, the speeds of persons movement in the premises of conference room and large-area office with related facilities have been determined. Consequently, the specific and total flow of persons for critical places of unprotected escape ways (doorways) up to entry into hall space that is part of t ed.

he protected escape way has been determinOutput values are stated in the tab. 2.

1 On the fixed wing of double wing door between office section and hall there will be installed lever gate.

3 | Safety Engineering

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

Table 2. Output values for determination of the persons movem n the artent time i assessed p of the floor

Room name

Density of persons D (p ) er.m-2

Movement speed of persons (m ) .min-1

Spec w ific floof persons Fs (per.min-1.m-

1)

C e onferencroom 0,67 69,0 46,24

Office section 0,23 (0,54) 2 71,93 38,84

Room name

Total flow of persons Fc (p ) er.min-1

Movement time of persons

tu1 ) (min

Movement ti me of

persons tu2 (min)

C e onferencroom 73,98 0,14 0,90

Office section 54,38 0,27 1,903

Supposed time of persons movement tu to the hspaces is 2,31 minutes.

all

etermination of required safe escape time t

gher values than

revious aragra or

evac

Table 3. Determina f th eeded for h ed e

D cfrom the assessed part of the floor At detailed assessment of the persons evacuation, it is advisable to set necessary time for persons evacuation tc, when is possible to proceed according to the equation (1) of the article. Determination of detection and alarm time td and time to start evacuation tz can pose certain problem in practice, where it is necessary to estimate stated values. It is necessary to realise that stated values can take the same or hiself time of persons movement through the building tu. For assessment, we can use [8]. Based on the assumptions stated in the pp phs, determination of time needed f

uation has been shown in the tab. 3.

tion oe assess

e time n part of thevacuation in t floor tc

Assessing place

Detection and alarm

time t (min) d

Time to start of

evacuation tz ) (min

Time of movement

through the obje in) ct tu (m

Required safe escape time tc

(min)

En tryto the hall

1 0,5 2,31 3,85

Time needed for evacuation to the entry of protected escape way is 3,85 minutes. Time of smoke layer decrease in the premises of large-area office to the level

2 At movement speed determination was respected lower limit of

ted to 70 % of persons of all rooms in the assessing

vacuation

or,

the floor in the time of 00 s, are shown in the fig. 4.

e omplex proceeding of evacuation assessment

sessment of the easiest

sing premises) and changes during building peration.

utility of equation (3), then 0,54 persons.m-2. 3 The value is relapart of the floor.

of 2,5m is approximately 4 minutes4 (see fig. 2). Temperature of smoke layer in the assessed premises will not exceed 200°C (see fig. 2). Defined criteria of acceptability in terms of safe persons eassessment can be evaluated as satisfactory. Assessed parameters, i.e. smoke layer decrease and temperature course in the assessed part of the flostated by model CFAST are presented in the fig. 3. Smoke layer level and temperature stated by FDS model in the assessed part of3 Commentary on the possibilities at morc In the previous paragraphs, we described a more detailed proceeding of evaluation of some parameters used at escape ways assessment, i.e. time needed for persons evacuation, time for filling of premises with smoke gases to the level 2,5m and smoke layer temperature course in the characteristic part of the floor. Although similar evaluation of the above described parameters requires using of fire engineering methods, it is the asdeterminable parameters. The safety of persons on the escape ways can be also assessed by another parameters, e.g. visibility in the space, toxicity of combustion products. Determination of these parameters is however usually more complicated, sensitive to precise entering conditions (e.g. type and amount of flammable material, which is in the asseso

Figure 3. Illustration of smoke layer decrease and temperature course in the assessing part of the floor

4 The less suitable value acquired by fire models has been considered

4 | Safety Engineering

P. Kučera, J. Pokorný, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 1-6

Figure 4. Illustration of the smoke layer level and temperature in the assessing part of the floor

CONCLUSION This article elaborates on the possibility of fire models CFAST and FDS usage for fire dynamics assessment on the specific case of the defined part of the object, when the temperature direction and smoke layer level have been evaluated. In this case, the results of both models achieve the good equality. Input values acquired by fire models were used as a basis for detailed assessment of persons evacuation executed through “manual“ calculations. Evaluation was used to prove that the stated criteria of acceptability have not been exceeded. The article demonstrates the possible combination of sophisticated tools, fire models with simplified calculation process for application in a certain case. SYMBOLS A room or compartment area where are people (m2) B width of escape route (-) D density of persons (persons.m-2) E number of persons (persons) Fs specific flow of persons (pesons.min-1.m-1) Fc total flow of persons (person.min-1) Q& heat release rate HRR (kW)

0Q& reference heat release rate (1000 kW) a coefficient of burning rate according to ČSN 73 0802 k coefficient of persons movement speed (m.min-1) lu length of escape route (m) lui length of i-escape route (m) p fire load according to ČSN 73 0802 (kg.m-2) time after initiation (s) tc required safe escape time (min) td detection time and alarm time (min) tg required time for reaching reference velocity (s) tu time of persons movement through the building (min) tu1 time required for distance overcoming (min) tu2 time required for passage trough escape way (min) tz time to start of evacuation of persons (min) v speed of movement (m.min-1) vi i-speed of movement (m.min-1)

REFERENCES [1] NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology,

Building and Fire Research Laboratory [online]. URL: http://<cfast.nist.gov> [cit. 22.10.2010]. Last revision 04.07.2009.

[2] NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology, Building and Fire Research Laboratory [online]. URL: http://<fire.nist.gov/fds> [cit. 24.01.2011]. Last revision 22.11.2010.

[3] GWYNNE, S. M. V., ROSENBAUM, E. R.: Employing the Hydraulic Model in Assessing Emergency Movement. SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering. Fourth Edition, Section 3, Chapter 13. Quincy: National Fire Protection Association, 2008, s. 373-396, ISBN-10:0-87765-821-8, ISBN-13: 978-0-87765-821-4.

[4] PREDTEČENSKIJ, M., MILINSKIJ, I. Evakuace osob z budov. Praha: Svaz požární ochrany, Svazek 30, 1972, 272 s.

[5] ČSN 73 0802 Požární bezpečnost staveb - Nevýrobní objekty. Praha: Úřad pro technickou normalizaci, metrologii a státní zkušebnictví, 2009.

[6] FOLWARCZNY, L., POKORNÝ, J. Evakuace osob. Ostrava: Sdružení požárního a bezpečnostního inženýrství v Ostravě, Edice SPBI Spektrum 47, 2006. 125 s. ISBN 80-86634-92-2.

[7] ISO/TR 13387-8 Fire safety engineering Part 8: Life safety - Occupant behaviour, location and condition. Geneva: ISO International organization for Standardization, 1999, 36 s.

[8] HOSSER, D.: Leitfaden Ingenieurmethoden des Brand-schutzes. Braunschweig, Technisch-Wissenschaftlicher Beirat (TWB) der Vereinigung zur Förderung des Deutschen Brandschutzes e.V. (vfdb), 2009, 386 s.

BIOGRAPHY of the first author

Petr Kučera was born in Ústí nad Labem, in the Czech Republic, in 1978. He received the diplomas in fire safety and civil engineering and the Ph.D. degree in fire safety from the VŠB – Technical University of Ostrava (VŠB-TUO), Faculty of Safety Engineering. His main areas of research include fire protection of buildings, fire dynamics etc. He is working as an assistant professor and a head of Department of Fire Protection at the Faculty of Safety Engineering, VŠB. BIOGRAPHY of the second author

Jiří Pokorný was born in Opava, in the Czech Republic, in 1969. He received the diploma in fire safety and the Ph.D. degree in fire safety from the VŠB – Technical University of Ostrava, Faculty of Mining and Geology.

His main areas of research include fire protection of buildings, fire dynamics etc. He is currently working as a deputy for Prevention and Civil Emergency Preparedness, Fire Rescue Service of Moravian-Silesian Region.

5 | Safety Engineering

UDC 697.245.7 : 629.7.058.43 Original article

Paper is presented at the "International Conference Safety of Technical Systems in Living and Working Environment", Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš, October 2011, Niš.

7 | Safety Engineering

BORIS PRESHELKOV1

ROSEN BORISOV2

RADOSLAV KARTOV3

MILAN BLAGOJEVIĆ4

1,2,3Academy at The Ministry of the

Interior in Sofia, Fire Safety and Civil Protection

Faculty 4University of Nis,

Faculty of occupational safety

[email protected] [email protected]

[email protected] [email protected]

A STUDY OF DETERMENING SAFE DISTANCES BETWEEN CERAMIC INFRARED GAS HEATERS AND COMBUSTIBLE MATERIALS Abstract: This is a study of determining the safe distances between combustible materials and ceramic infrared gas heaters. It contains general information about infrared heating, information about the experimental set-up and the results of the study.

Key words: infrared gas heaters, safe distances.

INTRODUCTION An infrared heater uses wavelengths of infrared light to generate heat. Infrared light is not visible to the naked eye because it is not part of the spectrum of light you can see. Unlike traditional heaters, infrared does not heat the air; it heats objects, which then warm the air by contact. Infrared heaters are efficient and cost-effective, though they are not ideal for heating an entire home since they only heat objects in their direct vicinity. They are most commonly used in large open spaces, like warehouses or garages, as a means to offset the loss of heat from large open doors [3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12].

Safety

For better safety keep infrared heaters at least three feet away from any combustible material. The majority of the body of the heater stays cool and does not present a burning hazard. While it is thought that the radiation from infrared heaters is dangerous, there is no scientific evidence that infrared rays are damaging without ultraviolet light. According to the Infrared Heaters website, infrared heaters are one of the safest forms of heating sources. Infrared heaters are powered by a variety of fuel, including propane, electricity and natural gas. The Infrared Heater Safety Council (IHSC) reports infrared heaters should be kept a safe distance from combustible materials, such as paper, wood and fabrics. The risk of fire can be reduced by following instructions for the safe distance to place heaters from combustible materials usually found in the manufacturer's manual [5].

Installation

Proper installation of infrared heaters can reduce the risk to the safety of an operator or property. The IHSC reports installation of heating equipment following

construction codes and guidelines can reduce the risk of leaks, improper heating ignition and fire [5]. Materials

Some of the polymeric materials - low density polyethylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride etc., began to lose its beneficial properties when heated to temperatures higher than 60 °C. Therefore the research is accepted as critical temperature of 60 °C [1]. Use

Infrared heaters are used under different circumstances than central air heaters which make up the majority of heaters in modern housing. Infrared heaters give direct heat vs. central air heaters, which heat the air within a room; therefore, infrared heating is useful in a variety of circumstances, such as within open rooms or outside. The major disadvantage of infrared heaters is that they are relatively useless in heating anything outside of the direct area around the heater. Since they only provide direct heat on objects around them, it is difficult to use a single heater to heat an entire household. Infrared heaters offer more localized options for heating areas around homes and businesses. A large automotive repair shop can use these heaters at each lift where a mechanic works, rather than attempting to heat the entire shop. The same principle applies to heating an outdoor patio [2,5]. Safety regulations

This type of heating appliances are becoming growingly popular in Bulgaria hence new safety regulations are required, similar to the ones In NFPA 54 ANSI Z223.1–2002 National Fuel Gas Code 2002 Edition. Below is an extract from that code[10]: 9.18 Infrared Heaters. 9.18.1 Support. Suspended-type infrared heaters shall be fixed in position independent of gas and electric

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

supply lines. Hangers and brackets shall be of noncombustible material. Heaters subject to vibration shall be provided with vibration-isolating hangers. 9.18.2 Clearance. The installation of infrared heaters shall meet the following clearance requirements: (1) Listed heaters shall be installed with clearances from combustible material in accordance with their listing and the manufacturers’ instructions. (2) Unlisted heaters shall be installed in accordance with clearances from combustible material acceptable to the authority having jurisdiction. (3) In locations used for the storage of combustible materials, signs shall be posted to specify the maximum permissible stacking height to maintain required clearances from the heater to the combustibles. 9.18.3 Combustion and Ventilation Air. 9.18.3.1 Where unvented infrared heaters are used, natural or mechanical means shall be provided to supply and exhaust at least 4 ft3/min/1000 Btu/hr. (0.38 m3/min/kW) input of installed heaters. 9.18.3.2 Exhaust openings for removing flue products shall be above the level of the heaters [10]. EXPERIMENTAL SET-UP A series of experimental trials is required for determining and defining the safety regulations for the use of Infrared Gas Heaters. An experimental set-up was created in order to conduct the test trials. The set-up consisted of infrared gas heater, 28 ceramic test samples placed around the heater at different distances, LPG supply system and pyrometer for measuring the surface temperature of the samples[11].

Figure 1. Photos of the experimental set-up During the experimental trials we have used infrared heaters which vary in power. The duration of each trial

varies depending on the time it takes for the sample temperature to stabilize.

Figure 2. Photos of the experimental set-up At the end of each trial temperature and distance values are collated in a Microsoft Excel file. Upon completion of all trials the data for each sample is extracted, analyzed and presented in a chart format as shown below.

Figure 3. Temperature graph for Sample 1

The individual graphs for each sample are then used for the creation of temperature fields of area surrounding the infrared gas heater.

8 | Safety Engineering

B. Preshelkov, R. Borisov, R. Kartov, M. Blagojević, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 7-10

Figure 4. Horizontal Temperature Field at the height of the Infrared Heater

Figure 5. Vertical Temperature Field from a frontal prospective

Figure 6. Vertical Temperature Field from a sideways prospective

9 | Safety Engineering

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

REFERENCES The experimental trials allow as understand the

correlation between the power of the Infrared Heater and the sample temperature.

[1] Ts. Tsenov: “Construction materials”, Albatros, 1996,

Sofia [2] http://web.need.bg/sbm-bg/index.html - “СВМ –

Bulgaria“

[3] Gaz de France, „ Le Gaz Naturel Dans le Locaux Tertiaries de Grand Volume“, Design Media – 1995

[4] Health and Safety Executive – “Incidents relating to the supply and use of flammable gas” - 2005/06 - 2009/10

[5] Infrared Heater Safety Council, “Heating safely with gas-fired infrared heaters” – 2008

[6] Jennifer Flynn, “Natural Gas and LP-Gas Home Structure Fires”, January 2010

[7] Jennifer Flynn, “Natural Gas and LP-Gas Structure Fires in Properties Other Than Homes”, August 2007

[8] John R. Hall, “HOME FIRES INVOLVING HEATING EQUIPMENT”, September 2010 Figure 7. The correlation between the power of the Infrared

Heater and the sample temperature. [9] Kenneth J. Tremblay, “Selected Published Fire Incidents Involving Gas Heaters”, November 2006 [10] National Fire Protection Association, NFPA 54 ANSI Z223.1–2002 National Fuel Gas Code 2002 Edition CONCLUSION

[11] Trotec, “Operating manual TP9” [12] Williams S., “About Infrared Heaters 1. As per literature on the topic the safe maximum

temperature is considered to be 60oC. BIOGRAPHY of the first author 2. Infrared Gas Heaters shall be installed only in

high, well ventilated premises and in accordance with the manufacturers’ safety instructions.

Boris Preshelkov was born in Razlog, Bulgaria, in 1970. He received a master degree as engineer of Fire and Emergency Safety from the Academy of Ministry of the Interior, Faculty of Fire Safety and Civil Protection.

His main areas of research include Fire danger of the radiant heat flux, Fire safety of buildings etc. He is currently working as an assistant professor at the Faculty of Fire Safety and Civil protection at the Academy of Ministry of the Interior.

3. The minimum safe distances to combustible materials shall be as per the ones in the table.

Table1. The minimum safe distances to combustible materials

Power Above - А Side distance- В Below - С

- 14 kW 110 cm 30 cm 200 cm

14 - 27 kW 130 cm 30 cm 250 cm

Figure 8. Safety distances

10 | Safety Engineering

UDC 614.84 : 628.854 : 52-17 Original article

Paper is presented at the "International Conference Safety of Technical Systems in Living and Working Environment", Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš, October 2011, Niš.

11 | Safety Engineering

DARKO ZIGAR1

DESIMIR JOVANOVIĆ2

MARTINA ZDRAVKOVIĆ3

1-4University of Niš, Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš

1darko.zigar@ znrfak.ni.ac.rs

2desimir.jovanovic@ znrfak.ni.ac.rs 3martina.zdravkovic@ znrfak.ni.ac.rs

CFD STUDY OF FIRE PROTECTION SYSTEMS IN TUNNEL FIRES Abstract: Field modelling based on the Computational Fluid Dynamics methodology plays an important role in fire research, and in the fire safety design and risk assessment of buildings: CFD codes can potentially be used to evaluate the effects of different designs and of emergency systems, and to assess the performance of safety measures over a wide range of fire scenarios. In this study the NIST Fire Dynamics Simulator version 5 (FDS5), a computational fluid dynamic (CFD) model, was used to simulate a series of full-scale fire tests of ventilation and sprinkler systems conducted in a test tunnel. Key words: tunnel, fire, ventilation, sprinkler, simulation.

INTRODUCTION Fires in road and railway tunnels are particularly dangerous because the amount of firing material can be huge and the length of the way to escape outside the enclosure can be in some cases several kilometres. Fire accidents in road tunnels have proven to be extremely costly in terms of human lives, increased congestion, pollution and reparation. Development of fire and smoke spread are affected by the fire set-up and ventilation conditions in the tunnel. To prevent fires in road and railway tunnels existing tunnels should be upgraded and new tunnels should be equipped with efficient fire protection systems. One of a the adequate methods that may be used to prove the characteristics of a fire safety measures is fire simulations.

PROBLEM DESCRIPTION The ventilation system is used for controlling smoke, hot and toxic combustion gases during a fire emergency, in order to allow safe evacuation and rescue. Ventilation may be provided by natural means (Fig. 1), or by mechanical equipment (longitudinal, semi-transverse or full transverse ventilation systems, (Fig. 3 ).

Figure 1. Natural ventilation

With no air current in the fire zone, the smoke progresses in a symmetrical way on both sides of the fire. The smoke remains stratified until it cools down due to the combined effects of the convective heat exchange with the walls and the mixing between the smoke and the fresh air layer, [1]. A natural ventilation system depends on the pressure differential that is

created by atmospheric conditions and differences in elevation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Smoke behaviour in a sloping tunnel

The longitudinal ventilation system (Fig. 3) creates a longitudinal flow along the roadway tunnel by introducing or removing air from the tunnel at a number of points. Longitudinal flow is provided by jet fans.

Figure 3. Longitudinal ventilation system

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

The ventilation system would be operated to force the smoke and hot gases in the direction of the empty tunnel to provide a clear and safe environment behind the fire for evacuees and fire fighters. If the ventilation capacity is sufficient (Fig. 4b and Fig. 4c), all of the heated air and smoke will flow in the downstream direction. If the ventilation is weak (Fig. 4a), the upper layer of heated air and smoke may flow in the opposite direction causing backlayering, [1].

Figure 4. Influence of longitudinal air velocity (Vvent) on smoke progress in the fire zone (Vc= critical velocity)

The occurrence of backlayering depends on many factors including the intensity of fire, the grade and geometry of the tunnel, and the velocity of the ventilating air approaching the fire. The ability of the longitudinal ventilation system to prevent backlayering is the current industry standard to measure the adequacy of the system for smoke control (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Backlayering distance vs. longitudinal air velocity

for two heptane pool surfaces

The simultaneous solution of Eqn. (1) and Eqn. (2), by iteration, determines the critical velocity. The critical velocity, Vc, is the minimum steady-state velocity of the ventilation air moving toward a fire that is necessary to prevent backlayering, [5].

1/3

1C gp f

gHQV K KC ATρ

⎛ ⎞= ⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟

⎝ ⎠ (1)

fp C

QTC AVρ

⎛ ⎞T= +⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟

⎝ ⎠ (2)

Where: A - Area perpendicular to the flow [(m2)] Cp - Specific heat of air [(kJ/kg K)] g - Acceleration caused by gravity [(m/sec2)] H - Height of duct or tunnel at the fire site [(m)] K1 - 0.606 Kg - Grade factor (see Fig. 6) Q - Heat fire is adding directly to air at the fire site [(MW)] T - Temperature of the approach air [(K)] Tf - Average temperature of the fire site gases [(K)] Vc - Critical velocity [(m/sec)] ρ - Average density of the upstream air [(kg/m3)]

Figure 6. Grade factor for determining critical velocity

For large tunnel fires critical velocity can be taken as dependent of the HRR (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Critical velocities as function of total HRR according to four different relations

12 | Safety Engineering

D. Zigar, D. Jovanović, M. Zdravković, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 11-16

13 | Safety Engineering

Fire Data for Typical Vehicles, according NFPA 502 Standard for Road Tunnels, Bridges and Other Limited- Access Highways are shown in the Table 1, [5].

Table 1. Fire Data for Typical Vehicles

Type of vehicle HRR (MW) Car 5-10

Multiple passenger cars (2-4 vehicles) 10-20

Bus 20-30 Heavy goods truck 70-200

Tanker 200-300

(e) Even a light spray from sprinklers can catch motorists unaware and can exceed that which windshield wipers could clear. Sprinkler discharge can also cause the roadway to become dangerously slippery. (f)Water that sprays from the ceiling of a subaqueous tunnel suggests tunnel failure and can induce panic in motorists. (g) The use of sprinklers can cause the delamination of the smoke layer and induce turbulence and mixing of the air and smoke, thus threatening the safety of motorists in the tunnel. (h) Periodic testing of a fire sprinkler system to determine its state of readiness is impractical and costly.

In Figure 8 the five fire temperature curves are presented graphically (the first two hours), [2].

NUMERICAL MODEL For the calculation of temperature fields and smoke concentration fields formed in case of fire within the tunnel space, the CFD software package NIST Fire Dynamics Simulator version 5 (FDS5) was used. For the calculation of flow and temperature fields of the air formed within the tunnel, k-ε turbulent model was used. Because of certain identical segments of the tunnel and the high length of the entire tunnel (Fig 9), in simulation used segment he was dimension: 600m(segment 60m) x 11.7m x 7.1m (lenght, wide, high, respectivelly). The FDS5 domain was divided into cells of dimension 0.15 m × 0.15 m × 0.15 m. The tunnel is built at grade in concrete. The fire source in the simulation was represented by burning of a flammable liquid in a pool with dimensions 5 x 5 m. The maximum heat release rate per unit area (HRRPUA) of the fire was 4000 kW and the total heat release rate (HRR) was 100 MW. The initial air temperature in the whole tunnel was set to 20 °C. This calculation determined that the ventilation of each tunnel segment is to be carried out by 2×2 pairs of regularly arranged jet fans and three parallel lines of sprinklers K-11 type. Distance between sprinklers is 3.05 m, according NFPA 13 Standard, [6]. The maximum volumetric flow of fresh air through these jet fans should be 17.1 m3/s and 34.2 m3/s.

Figure 8. Specific temperature curves of hydrocarbon fires in tunnels

In Japan and Australia water extinguishment systems are widely used in tunnels. In Europe, however, there has been a reluctance to use sprinkler in tunnels. According NFPA 502 Standard the major concerns expressed by tunnel authorities regarding fire sprinkler use and effectiveness include the following, [5]: (a) Typical fires usually occur under vehicles or inside passenger or engine compartments that are designed to be waterproof from above; therefore, overhead sprinklers have no extinguishing effect. (b) With any delay between ignition and sprinkler activation, a thin water spray on a very hot fire produces large quantities of superheated steam without suppressing the fire. Such steam has the potential to be more damaging than smoke.

(c) Tunnels are long and narrow, often sloped laterally and longitudinally, usually ventilated, and never subdivided, so heat normally is not localized over a fire. (d) Because of stratification of the hot gases plume along the tunnel ceiling, a number of activated sprinklers are unlikely to be located over the fire. A large number ofactivated sprinklers are likely to be located at a distance from the fire scene, producing a cooling effect that tends to draw the stratified layer of smoke down toward the roadway level.

Figure 9. The computational domain for the tunnel fire simulations

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

RESULTS OF CALCULATIONS Spread of smoke in a tunnel

a) Natural ventilation

b) Forced ventilation (jet fan 17.1 m3/s)- backlayering

c) Forced ventilation (jet fan 34.2 m3/s)

Figure 10. Spread of smoke in a tunnel

a) Without sprinklers activation

b) Sprinklers activated

Figure 11. Spread of smoke in a tunnel without and with activated sprinklers

Temperature schedule

a) Natural ventilation

b) Forced ventilation (jet fan 17.1 m3/s)- backlayering

14 | Safety Engineering

D. Zigar, D. Jovanović, M. Zdravković, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 11-16

c) Forced ventilation (jet fan 34.2 m3/s)

Figure 12. Temperature schedule along the centreline vertical plane

Figure 13. Temperature schedule along the centreline vertical plane with activated sprinklers

Sprinklers activation

Sprinklers position

a) Sprinklers activation: 20 sec. since ignition

b) Sprinklers activation: 30 sec. since ignition

c) Sprinklers activation: 40 sec. since ignition

Figure 14. Splinklers position and activation

15 | Safety Engineering

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

CONCLUSION In the event of a fire in an tunnel with natural ventilation (Fig. 10a), due to difference in densities, hot combustion products rise above the fire and entrain the surrounding cold air forming a plume. The rising plume reaches the ceiling and forms two smoke streams flowing in opposite directions along the ceiling. In tunnels with longitudinal ventilation systems (Fig. 10b and Fig. 10c), the symmetry of the rising plume and the ceiling smoke streams is broken. The rising plume bends and the length of the ceiling layer flowing against the ventilation current is reduced. The reversal of the flow of the plume is referred to as backlayering (Fig. 10b). If ventilation system operates only half at the maximum flow rate designed for the ventilation of the tunnel (17.1 m3/s) come to a backlayering effect. If ventilation system operates only at the maximum flow rate designed for the ventilation of the tunnel (Fig .10c), no wil be backlayering effect. In fire simulation with sprinklers, sprinklers activation come to destroying the smoke stratification (Fig. 11b) and there by decreasing the visibility, spreading liquid fuel over a larger area and there by spreading the fire, the risk for explosion, the production of steam affecting the people inside the tunnel. The maximum predicted gas temperature near the ceiling was just below 1000 °C (Fig. 12), in simulations with activated sprinklers 925 °C (Fig. 13). Also, the sprinkler system was not able to reduce temperature directly above the fire in the unshielded simulation. Apparently, sprinkler droplets are too light to penetrate the fire plume and are simply swept away. Simulation results suggested that the longitudinal ventilation system was very effective for blowing all smoke and hot gases in the downstream direction, which could be generally deemed empty, so immediately creating upstream the fire a safe route for evacuation and rescue.

REFERENCES [1] A. Kashef, N. Bénichou, G. Lougheed: “Numerical

modelling and behaviour of smoke produced from fires in the Ville-Marie and L.-H.-La ontaine Tunnels”, literature review, NRCC Report IRC-RR-141, 2003.

[2] D. Lacroix, A. Haack: “PIARC Design Criteria for Resistance to Fire for Road Tunnel Structures”, In Joint Issue ITA/PIARC of Route-Roads on Fire Safety in Tunnels, 2004.

[3] K. McGrattan, S.Hostikka, J. Floyd, H. Baum, R. Rhem: “Fire Dynamics Simulator (Version 5) Technical reference guide”, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2007, Washington.

[4] M. Banjac, B.Nikolić: “Simulation of a tunnel fire and optimization of the ventilation system with the use of numerical fluid dynamics”, 11th International conference on fire and explosion protection, Novi Sad, 2008, pp. 44-50.

[5] NFPA 502: “Standard for Road Tunnels, Bridges, and other Limited Access Highways”, 2004 ed., National Fire Protection Association, 2004.

[6] NFPA 13: “Standard for The Installation of Sprinkler Systems”, 1999 ed., National Fire Protection Association, 1999.

BIOGRAPHY of the first author Darko Zigar was born on April 16, 1973. in Pancevo, Serbia. He received B.Sc. degree in Environmental Protection and M.Sc. degree in Occupational Safety in 2002 and 2007 respectively, from University of Niš, Serbia. He has been with the Faculty of Occupational Safety, University of Niš, since 2008., where he is working as a researcher / assistant lecturer. His areas of expertise include numerical fire simulations, as well as investigations of possible adverse effects of electromagnetic field irradiation from mobile phones and wireless systems.

16 | Safety Engineering

UDC 331.45 : 531.717.5 : 519.816 Review article

Paper is presented at the "International Conference Safety of Technical Systems in Living and Working Environment", Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš, October 2011, Niš.

17 | Safety Engineering

GORAN JANAĆKOVIĆ1

SUZANA SAVIĆ2

MIOMIR STANKOVIĆ3

University of Niš, Faculty of Occupational Safety in Niš

[email protected] [email protected]

MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION ANALYSIS IN OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS Abstract: Increasing the effectiveness of occupational safety increases the safety of an organization as its important performance. Safety performance indicators measure changes in the level of safety (related to accident prevention, preparedness and response) over time, which result from the actions taken to reduce appropriate risks. This paper presents the characteristics of basic types of safety indicators, the structure of safety factors, performances and indicators, as well as the multi-criteria decision analysis process and methods in safety management systems.

Key words: occupational safety, performances, indicators, multi-criteria decision making.

INTRODUCTION "The complexity of modern systems stems from the combination and use of various resources and the characteristics of the dynamic, turbulent environment in which they exist. Resources, internal and external environment interact to each other, and it defines system performances" [1]. The term includes a set of performance indicators to quantitatively or qualitatively describe the quality of a system. Indicators of health and safety have been developed and explored along with the raising awareness of the need for continuous improvement of quality of life. This includes health and safety at work and the importance of indicators of social responsibility for improving the economic indicators of the organization. Two different types of safety indicators: activity indicators (indirect or lagging indicators) and outcome indicators (direct or leading indicators) have been analyzed in this paper. Furthermore, it describes safety analysis - accident investigation and predictive assessment – and the structure of safety factors, performances and indicators. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) methods that can be used in the occupational safety management systems, which are based on occupational safety indicators, have been presented at the end of the paper. SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS IN ORGANIZATIONS Safety management systems are integrated mechanisms in organisations designed to control the risks that can affect workers’ health and safety, and at the same time to ensure that the firm can easily comply with the relevant legislation [2]. They are parts of general organizational management systems that include organisational structure, responsibilities, practices, procedures, processes, and resources for determining and implementing an accident prevention policy; they

also include data on organisation and personnel, identification and evaluation of hazards and risks, operational control, management of changes, planning for emergency situations, monitoring performance, audit and review [3]. A good safety management system is fully integrated into an organization, and it defines policies, strategies and procedures that provide internal consistency and management. Developing the effective safety management system means creation of awareness, understanding, motivation and commitment among all the employees in an organization [4]. Achieved safety performance are conditioned by the effects of internal and external factors that can be objective or subjective. Objective factors are: the social (and economic and market system), technical (type of production, technical progress, the characteristics of engineering and technology), natural (climate), dispositive (innovation, entrepreneurship, quality management). Subjective factors are the factors of organizational nature and everything that is reflected in the performance characteristics of employees and the organization as a whole [1]. As it is described in [5], there are some key aspects of a good occupational health and safety management system, which can reduce workplace accidents in a sustainable manner: Development of a Safety Policy; Participation; Training and development of employee competences; Communication and transfer of information about the workplace, possible risks and preventive measures; Planning; and Control and review of activities carried out within the organisation. To achieve the best performance, safety must be integrated into all the organisation’s decisions and actions. Integration on the level of organization is the coordination of processes that are defined in the context of the primary safety activities on the basis that removes organizational, procedural and informational barriers for efficient flow of materials and data

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

exchange between different organizational units responsible for safety. It allows formulation of strategies, safety processes, information systems, technology and data within the boundaries of the organization in order to provide adequate safety level and as a consequence achievement of advantages over the competition [6]. Safety management system has a positive effect on competitiveness performance. It requires the formula-tion of working procedures, instructions, and planning and control of the work; the higher productivity, as a consequence of the improvement in quality and reduc-tion in costs caused by the accidents; the higher cus-tomer satisfaction and better reputation of organization, since occupational safety is particularly important to society; higher organizational degree of innovation, due to the technological and organizational innovations de-rived from the improvements in safety [5]. The relationship between safety and competitiveness at the level of the organization is presented in Fig. 1 [7].

Figure 1. The effects of safety at organizational level [7] Specialist knowledge and motivated employees are all assets that can provide organizations with a specific competitive advantage long periods of time. These assets are strongly affected by occupational accident rates and working conditions. SAFETY PERFORMANCE AND INDICATORS The concept of health and safety performance includes a set of indicators (indicators) that quantitatively or qualitatively describe the specific effects, contributions, and the results that are achieved in the safety system. Safety indicators are approximate measures for items identified as important in the underlying models of safety [3]. Safety performance indicators measure the changes in the level of safety (related to accident prevention, preparedness and response) over time, as the result of actions taken to reduce appropriate risks [3]. Safety performance indicators system provides a global view of safety status in a plant or an organization. It can be used in conjunction with inspection and evaluation activities carried out for the regulatory control. Safety indicators evaluation results can be used as an input for inspections or audits planning [8].

Findings from others activities give information for safety indicators interpretation, and safety indicators system is useful to evaluate efficiency of regulatory strategies. A set of safety performance indicators is an assembly of direct and indirect measures of the organizational safety. Process accidents are prevented by managing a safety performance indicator (SPI) program that consists of four different phases: identifying, measuring, analysing, and adjusting key process activities or indicators. Safety life cycle is an engineering process designed to achieve a risk-based level of safety with performance criteria that allow versatile technologies and optimal design solutions [9]. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines two classes of indicators: activities indicators and outcome indicators [3]. Activities indicators are means for measuring actions or conditions which, within the context accident prevention, preparedness and response, should maintain or lead to improvements in safety (e.g., reduction in risk, improvements in safety management and safety culture, mitigation of effects in event of an accident). Outcome indicators are used for measuring the results, effects or consequences of activities carried out in the context of a programme related to accident prevention, preparedness and response. Safety indicator project [10] also defines two types of indicators: direct indicators and indirect indicators. Direct (or outcome) indicators utilize different types of experience data. Indicators that can give early warnings are known as indirect (or predictive) indicators that are measures of performance of the functional units within an organization, such as operation, maintenance, training, and engineering support [10]. These indicators can be used to evaluate safety by assessing the performance level and the performance trend. Hopkins [11] discusses two dimensions of safety: personal safety versus process safety, and leading versus lagging indicators. Personal safety is about avoiding workplace incidents and workplace injuries of employees; it does not represent management of process hazards. According to that way of thinking, there are two different types of indicators: leading and lagging indicators. Lagging or outcome indicators are a measure of the undesired outcomes, such as injuries, accidents, near misses, number of control deviations that exceed process limits, releases of chemicals, procedures not followed correctly, equipment failures, high level alarms, equipment deficiencies, etc. These indicators need to be monitored but they will not give adequate forewarning to prevent accidents. Leading or activity indicators (also known as input indicators) are measures that determine the quality of activities that prevent outcomes. Leading indicators are selected to provide an early warning just in time to prevent process accidents. They include training, audits, and inspections, mechanical integrity checks,

18 | Safety Engineering

G. Janaćković, S. Savić, M. Stanković, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 17-22

timely maintenance, use of check lists, emergency procedures that are tested on regular basis, risk assessments made and related to layers of protection analysis, and measurements of leadership and workforce attitudes. According to [12], there are three indicator types, as presented in Tab. 1. The size of the set can be limited to get the required information using the smaller possible number of indicators. Indicators have to be predictive and sensitive. Considering the consequences produced by degradations at organizational level, indirect indicators can be included in order to evaluate those aspects.

Table 1. Description of indicator types according to different systems of classification in the HSE guide [12]

Classification of indicators Indicator Type

Definition Examples Input/ outcome

Measures of safety activity Lead Lead

Failures revealed by safety activity Lead Lead Lag

Failures in use Lag Lag Lag

The dimensions in characterising safety indicators could relate to different final outcomes such as process safety or occupational safety. Indicators could also address: technical safety features being in place and their performance; nature and characteristics of the hazards; formal safety organization systems, which are in place and how they perform; informal safety issues; communication and co-operation issues as discussed in [3]; absolute values or trends (changes of performance over time); economic consequences and probability for different outcomes. The first two areas can be the scope of technically oriented audits, and the third is concerned with organisational audits. THE STRUCTURE OF SAFETY FACTORS, PERFORMANCES AND INDICATORS

Analysis of the problem of safety at work can be done on the basis of empirical data in terms of searching for the causes of accidents, or on the basis of speculation and retrospectives. According to [13] the first perspective is related to the development of the search for causes of accidents, moving from technical, to human, and further to organizational causes, i.e. causal chain. The second perspective is based on a predictive and a retrospective view. It makes a big difference whether we try to predict the possibility of having a major accident “tomorrow”, including all possible causes, or if we only try to establish the causes after-the-event. Based on these two presented perspectives, the technical-human-organizational, and the predictive-versus-retrospective, we establish a conceptual model in order to structure

and illustrate the previous research. This simplified model is shown in Fig. 2. The technical–human–organizational perspective is illustrated horizontally and the retrospective-versus-predictive perspective is illustrated vertically. For the prediction of risk, as for accident investigation, we can talk about a development from technical, to human, and even to organizational causes. This does not imply that all features of risk assessment can be classified according to technical–human–organizational scheme.

Figure 2. Accident investigation versus predictive assessment

[14] Depending on the application situation the demands on safety indicators will vary considerably. One approach is therefore to start with the purpose of the indicators and the way they will be used. Fig. 3 illustrates each of the safety factors which are considered important by the key decision makers. The senior management team is hiring quality personnel, providing safety orientation, promoting safety through top management commitment, and developing a formal learning system. They were critical to improving an organizational safety performance. The safety, health and environmental team can identify that individual empowerment, responsibility, and systems for anonymous reporting and feedback are essential to improve organizational and individual safety performance. The items elicited in the expert elicitation sessions thus represent the initial safety factor structure, as presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Safety factors structure [11]

Before defining the set of performance indicators, it was necessary to establish a framework to define the parameters and the associated indicators in order to assure that everything having influence on the organi-zational safety is included. After that, preliminary indicators were proposed in each area. In this stage all adequate indicators should be included. A screening process is necessary for all proposed indicators [8]. Based on the research presented in [3,13,15 and 16], we have defined the structure of safety factors, performances and indicators as shown in Tab. 2. Of course, this structure is neither complete nor final.

19 | Safety Engineering

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

Performances and indicators for each group of factors are selected according to specific circumstances. The selection of indicators depends on the method of analysis of problems related to health and safety (the technical-human-organizational and the predictive-versus-retrospective).

Table 2. Classification of safety factors and safety performance indicators (based on [3, 13, 15, 16])

Factors Performances Indicators

T

echn

ical

Functionality Reliability Flexibility Maintenance Costs

Level of protection number Number of control deviations that exceed process limits Number of failures Number of accidents Failure and repair intensity Mean time between failures Mean time to repair Availability Maintenance and infrastructure cost

H

uman

Knowledge Competence Leadership ability Risk-taking and problem solving capabilities Education Experience

Creating results by using knowledge Employees’ skills index

Haring and reporting knowledge Employees’ cooperation rate in teams Succession rate of training programs Success likelihood index Number of errors and omissions Absenteeism rate Injuries rate

O

rgan

izat

iona

l

Training Procedures, instructions Job safety analysis (JSA) Planning Coordination Control Design Preventive maintenance program

Proportion of process technicians having formal system training Average number of years of experience in total for relevant personnel Proportion of relevant personnel having received JSA training Number of controls of JSA preparation and application Number of hours inspection of accidents Efficiency in management of safety resources

E

nvir

onm

enta

l

Legislation Standardisation Protection Technologies Social Environmental Economic Environment Competitive Environment Perceptions and values of stakeholders

Level of application of legislation Number of implemented standards Level of social responsibility Level of technology protection Number of available databases on accidents Number of available funds Degree of innovation Degree of networking

MCDA METHODS IN SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) methods have become increasingly popular in decision-making for safety management systems because of the multi-dimensionality of the goal and the complexity of socio-economic and technical systems [17]. MCDA is an integrated evaluation. Compared to single criteria approach, the distinctive advantage of MCDA methods is to employ multi-criteria or attributes to obtain an integrated DM result. Generally, the MCDA problem for safety management decision making involves m alternatives evaluated on n criteria. The grouped decision matrix can be expressed as follows:

1 2

1 2

n

n

criteria C C Cweights w w w

alternatives ================

L

L

(1) 1 11 12 1

2 21 22 2

1 2

n

n

m m m mn m x n

A x x xA x x x

X

A x x x

⎛ ⎞⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟=⎜ ⎟⎜ ⎟⎝ ⎠

L

L

M M M M M

L

where xij is the value of j-th criteria with respect to the i-th alternative, wj is the weight of j-th criterion, n is the number of criteria and m is the number of alternatives. Based on the Eq. (1), corresponding decision making process can be described by means of algorithm presented in Fig. 4. It includes four main stages: formulation of alternatives and criteria selection, criteria weighting, evaluation, and final aggregation. Measuring effectiveness of the safety management systems is a problem. Developing evaluation criteria and methods that reliably measure effectiveness and efficiency is a prerequisite for selecting the best alternative, informing design-makers on performances of the alternatives and monitoring impacts on the social environment. The development and selection of criteria require parameters related to the reliability, appropriateness, practicality and limitations of measurement. These indexes are restricted and/or impacted each other. For example, the number of technical and societal possibilities are wanted to increase, but sometimes are blocked by economic and political interests [18]. Also, the advanced system may reduce the number of accidents, but excessive cost is needed to invest and/or maintain the system meanwhile. So the decision-maker is difficult to select the optimal system from options well. However, the weight values of evaluation indexes influence the evaluation results. Different weight values lead to different evaluation results. There are two methods: the equal weights and the rank-order weights.

20 | Safety Engineering

G. Janaćković, S. Savić, M. Stanković, Vol 1, No1 (2011) 17-22

Figure 4. MCDA process in safety management systems decision-making (based on [18])

There are also subjective and objective weighting methods (Tab.3). Subjective weighting methods such as pair-wise comparison were the most used methods in safety decision making. The objective weighting method elicits the criteria weights using the measurement data and information and reflects the difference degree. After determining the criteria weights it is necessary to determine the preference orders of alternative so that MCAD methods are employed to get the ranking order in Eq. (1). MCDA methods are divided into three categories, as presented in Table 4. Outranking methods allow incomparability between alternatives. This characteristic is important in situations where some alternatives cannot be compared to each other. The decision maker selects the best alternative based on the ranking orders after the calculation in a selected MCDA method. The application of various MCDA methods of calculation may give different preference ranking order.

Table 3. Weighting methods in MCDA decision making [18]

Categories Weighting methods Subjective weighting

Simple multiple-attribute rating technique (SMART), SMARTER, Swing, Trade-off, SIMOS, Consistent matrix analysis, AHP, Least-square method, Delphi method, PATTERN, Eigenvector method, Pair-wise comparison

Objective weighting

Least mean square (LMS) method, Minmax deviation method, Entropy method Principal component analysis, Multiple correlation coefficient, TOPSIS method, Variation coefficient, Vertical and horizontal method, Multi-objective optimization method

Combination weighting

Multiplication synthesis

Additive synthesis (Optimal weighting based on relational coefficient of gradation, Optimal weighting based on sum of squares, Optimal weighting based on minimum bias)

Table 4. MCDA methods [18]

Categories Weighting methods Elementary Dominance, Maximin, Maximax,

Conjunctive, Disjunctive, Lexicographic, Elimination by aspects, Linear assignment, Weighted additive, Weighted product

Unique synthesizing criteria

Analytical hierarchy process (AHP), TOPSIS, SMART, Grey relational analysis, Data envelopment analysis, Multi-attribute value theory (MAVT), Multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT), Utility theory additive (UTA), Fuzzy weighted sum, Fuzzy maximum

Outranking ELECTRE (I, IS, II, III, IV, TRI), PROMETHEE (I, II), ORESTRE

Methods used to aggregate the preference orders are called aggregation methods, and they are divided into two categories: voting method and mathematical aggregation method. General approach to aggregate alternatives’ preferences is the voting methods. The winning alternative in voting methods depends on which voting rule is used. Generally, Borda rule and Copeland rule are the most common voting rules. The mathematical aggregation methods are classified to two sub-categories, ‘‘hard aggregation method’’ and ‘‘soft aggregation method’’ based on including the decision-makers. CONCLUSION Managing occupational risk allows organizations to maintain and develop intellectual capital, which is fundamental for the development of the organization. Safety management system consists of a safety policy (principles and the responsibilities of all organization members), that encourage employees’ participation, training, continuous communication and collaboration, planning of the activities and adequate control of the activities. It has positive effect on: safety performance - by reducing the accident rate, and improving working conditions; and competitiveness - due to its positive

21 | Safety Engineering

SAFETY ENGINEERING - INŽENJERSTVO ZAŠTITE

influence on the organizational image, productivity, reputation and innovation.

[15] K. Øien: “A framework for the establishment of organizational risk indicators”, Realibility Engineering and System Safety, 74 (2001), pp. 147-167. When the research on developing indicators or metrics for

major hazards started, the focus was on direct or lagging indicators (after-the-event type of indicators). This approach counts the number of accidents or incidents or near misses, however, these indicators are not very useful as pre-warnings or early warnings. For early warnings, one needs to analyse causes of dangerous events and the condition of the factors that leads to accidents. This is achieved by indirect or proactive indicators (leading indicators) that provide performance feedback before an accident or incident occurs.

[16] F. Bozbura et al.: “Prioritization of human capital measurement indicators using fuzzy AHP”, Expert Systems with Applications, 32 (2007), pp. 1100-1112.

[17] G. Janaćković, S. Savić, M. Stanković: “Safety Performance Indicators in Organizational Safety Management Systems“, In Proc. of the 2nd Int. Conf. Life Cycle Engineering and Management ICDQM-2011, Belgrade, Serbia, pp. 131-139.

[18] L. Ustinovichius et al.: “Application of a quantitative multiple criteria decision making (MCDM-1) approach to the analysis of investments in construction“, Control and Cybernetics 2007;36, pp.251–68.

Defining safety performances and indicators, according to the specific organization, is the basis for application of multi-criteria decision-making in the safety management system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The research presented in this paper was partially supported by Serbian Ministry of Education and Science (project III42006).

REFERENCES BIOGRAPHIES [1] B. Krstić, V. Sekulić: Upravljanje performansama

preduzeća, Ekonomski fakultet, Niš, 2007. Goran Janaćković received his BSc and MSc degrees in CS and CE from the Faculty of Electronic Engineering, University of Niš, in 2000 and 2004, respectively. He is currently working on his PhD thesis at the Faculty of Occupational Safety, University of Niš.

His research interests are systems engineering, information systems in safety, information and communication networks, multi-criteria decision making and optimization, collaborative web technologies and knowledge management. Suzana Savić received her BSc degree in Automatics from the Faculty of Electronic Engineering. She obtained her MSc as well as PhD in Occupational Safety from the Faculty of Occupational Safety. She works as a full professor at the Faculty of Occupational Safety, University of Niš. Her research interests are systems and risk analysis and management, systems engineering and multi-criteria decision making.