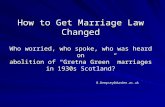

Abolition of Irregular Marriage: Who worried, who spoke, who was heard?

Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security: from ‘hub-and-spoke’ bilateralism to...

Transcript of Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security: from ‘hub-and-spoke’ bilateralism to...

The Pacific Review

, Vol. 16 No. 3 2003: 361–382

The Pacific Review

ISSN 0951–2748 print/ISSN 1470–1332 online © 2003 Taylor & Francis Ltdhttp://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/0951274032000085635

Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security: from ‘hub-and-spoke’ bilateralism to ‘multi-tiered’

Kuniko Ashizawa

Abstract

This article argues that Japan’s growing activism in promoting multi-lateral regional security arrangements since the early 1990s stems from the country’sadoption of the ‘multi-tiered approach’; a new policy perspective that packagesdifferent types of coordination among region states, including bilateral, multilateral,and minilateral or subregional, in a layered, hierarchical manner. The significanceof the approach explains why Japan has retained its enthusiasm for promotingmultilateral arrangements, despite continuous criticism of their effectiveness andsignificance, as well as the marked decline in Japan’s economic power to supportfinancially the country’s activism in regional institution-building. Meanwhile, themulti-tiered approach also explains Japan’s effort to maintain and strengthen itsbilateral security relationship with the United States during the last decade. Fourfactors – a perceived change in the regional security order, growing self-recognitionof major-power status, the legacy of history, and constitutional constraints – workedessentially to lead Japanese policy-makers to settle on a multi-tiered approach as adesirable policy choice in shaping the country’s security policy in post-Cold WarAsia.

Keywords

Japan; security policy; institution-building; multilateralism; regionalorder.

Introduction

One of the conspicuous developments in Japanese foreign policy-makingsince the early 1990s has been the country’s growing activism in promoting

Kuniko Ashizawa is a PhD candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, TuftsUniversity. She is currently resident as a visiting scholar at the Graduate School of Inter-national Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego.

Address: Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University ofCalifornia, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive MC-0519, La Jolla, CA 92093-0519, USA. E-mail:[email protected]

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 361 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

362

The Pacific Review

multilateral arrangements to deal with regional security issues in Asia.Starting with Japanese Foreign Minister Nakayama’s well-cited 1991proposal that later appeared in the form of the ASEAN Regional Forum,Japan’s diplomatic initiatives conspicuously promoted multilateral frame-works to deal with regional security matters, such as the Cambodia peacesettlement (Ikeda 1998; Kohno 1999) seminars among mid- and high-rankingdefense ministry and military officials in the region (Yamazaki 1999), and theUS–Japan–South Korea trilateral meeting to deal with North Korean issues(known as the Trilateral Coordination and Oversight Group).

1

Japan hasbeen a faithful supporter of the Korean Peninsula Energy DevelopmentOrganization (KEDO) and officially endorsed the ASEAN+3 framework(ASEAN and China, Japan, and South Korea) to deal with regional securityissues in the future (MOFA 2000). In June 2002, at the conference in Singa-pore, organized by the International Institute of Strategic Studies, theDirector General of the Japan’s Defense Agency (JDA), Gen Nakatani,proposed the creation of a region-wide forum among defense ministers withthe aim to establish concrete mechanisms for common security problems(International Institute for Strategic Studies 2002).

To be sure, these diplomatic initiatives may appear to be lacking decisive-ness or can be perceived as timid in their design, far from assuming leader-ship to create robust regional institutions to directly cope with securitychallenges. Yet, they cannot be lightly dismissed, because such efforts are aclear deviation from the country’s previous patterns of foreign and securitypolicy-making. Since the end of the Second World War, Japanese policy-makers purposely viewed the country’s national defense policy within thescope of the US–Japan bilateral security arrangement. Tokyo regarded thispattern of intra-regional security relations as a ‘hub-and-spoke’ system, inwhich the United States was anchored in the center, and matters of regionalsecurity were identified through US policies toward Japan. In such a system,either multilateral contacts among nearby countries or even bilateral oneswith other Asian countries rarely existed in terms of Japan’s regionalsecurity relationships.

2

In short, Japanese diplomatic initiatives to advancemultilateral regional security arrangements over the last decade werealmost non-existent prior to the 1990s.

Why did Japan decide to pursue these new diplomatic initiatives in itsforeign policy-making? What factors helped to sustain the efforts ofJapanese policy-makers, despite persistent skepticism and occasionalstraightforward criticism about the significance and utility of these newlycreated multilateral frameworks? I maintain that Japan’s growing supportfor initiatives promoting multilateral arrangements to deal with regionalsecurity issues stems from the country’s adoption of a new approach toregional security relations in Asia, called the ‘multi-tiered approach’ – a newconceptual framework that packages different types of coordination amongstates, including both bilateral and multilateral as organizing form, in alayered manner.

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 362 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

363

The multi-tiered approach was conceived by a handful of foreign policy-makers in the early 1990s and has become widely shared among thoseinvolved in foreign policy-making by the mid-1990s. To be sure, it is not anofficial doctrine or so-called ‘grand strategy’. Nor can it be treated as asocially constructed ideational factor such as ideas, beliefs, or norms asconstructivists (Checkel 1998; Ruggie 1998; Wendt 1999) might suggest.

3

Yet, such a disposition should not downplay its significance. The multi-tieredapproach has served Japanese foreign policy-makers in coping withemerging situations in regional security, by expanding horizons in Japan’spolicy-making options, beyond US–Japan bilateral relations. It lifted thepsychological bar long entrenched in the thinking of policy-makers thatprecluded the exploration of multilateral options for regional securitymanagement.

Examining how the multi-tiered approach was formulated in the early1990s also highlights several factors that worked essentially to help Japanesepolicy-makers determine desirable policy choices for national and regionalsecurity policy-making. These factors are (i)

a perceived change in theregional security order

, (ii)

growing self-recognition of major-power status

,(iii)

the legacy of history

, and (iv)

constitutional constraints

. The first twofactors created underlying imperatives for Japan to seek a new approach toits regional security policy-making that, in effect, addresses the question‘Why did Japan seek a new approach?’ The latter two helped the country toconceive the particular design of a multi-tiered approach, thus explainingthe question ‘Why did the country choose the particular design of a multi-tiered approach?’

This article will first summarize the concept of the multi-tiered approachand show how Japanese foreign policy-makers conceived and adopted thisnew approach in the early 1990s. It will then conduct a two-phased analysisin order to explain why Japanese policy-makers introduced this particularformula of the multi-tiered approach as an overall conceptual frameworkfor their regional security policy-making. Each phase focuses on the twodifferent factors mentioned above:

change in the regional order

and

self-recognition of major-power status

for the first phase, and

the legacy of history

and

constitutional constraints

for the second phase. The article concludes bysharing some implications relevant to overall Japanese foreign and securitypolicy-making toward the region.

Japan’s multi-tiered approach

The multi-tiered approach

4

The multi-tiered approach was prepared to understand and shape a desir-able new regional order, through which the fluctuating security relations ofpost-Cold War Asia could evolve. As the name suggests, it involvesdifferent levels of coordination among states to help maintain security in

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 363 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

364

The Pacific Review

the region. The levels of engagement can be generally categorized withinfour tiers.

The first tier refers to existing bilateral security relationships, such asalliances between the United States and Japan, South Korea and the Phil-ippines, as well as some other types of bilateral security cooperationincluding the special security arrangement between the United States andTaiwan. Its function is to offer security to the states involved, by preparingfor crucial threats to a country’s survival, deterring possible aggressors, andfighting wars.

The second tier refers to case-by-case, ad hoc arrangements by certaingroupings of states for dealing with specific security-related issues thatcannot be discussed effectively by all members of a region. The NorthKorean nuclear question, Cambodia peace settlement, and the territorialdispute between Japan and the Soviet Union (now Russia) are issuesassociated with this layer. It is often categorized as a subregional functionor mini-lateral arrangement. For example, the cooperation of ASEAN,Japan, Australia, and the UN Security Council Permanent-5 states for theCambodian peace settlement is a relevant case.

The third tier refers to a multilateral framework for security dialogueamong countries in the Asia-Pacific. The geographical scope of this functionis region-wide or pan-Pacific. The objective of this function is to promotecommunication and mutual understanding among states through theexchange of each member’s perspectives and consideration on issues relatedto regional security. It is expected to help enhance regional security byreducing misinformation and misunderstanding about a member country’smilitary capability and intention toward each other that could lead tounnecessary suspicions and tensions among some member countries. At thetime of the multi-tiered approach’s formation, the region apparently lackedany existing arrangements for the function of this tier.

The fourth tier includes non-security arrangements among regionalstates, particularly in the economic realm. Though this tier does not directlydeal with security issues, it is expected to maintain a favorable effect onsecurity matters in the long run, by increasing interactions among membersand promoting a sense of regional ties that may help to create community-type regional relations as achieved by Western European countries.ASEAN, which has mainly focused on economic cooperation over the years,and the newly created Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forumfall within this category.

As shown, the multi-tiered approach specifically assigns different func-tions to each level and emphasizes that all four levels should operatecomplementary to each other. It appears that by using the phrase ‘multi’rather than more concrete references of ‘four-tiered’ or so, the MOFAofficials involved in formulating the concept of multi-tiered approach prag-matically secured flexibility to add further functions and arrangementswhen necessary in the future. At the time of conceptualization, however,

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 364 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

365

they constantly referred to the particular four levels of functions, discussedhere, as necessarily composing the multi-tiered approach.

Two points of particular significance need to be noted here. The first isthat three of the levels explicitly refer to certain kinds of multilateralarrangements, or activities, as coordination frameworks among states forachieving the functions assigned, respectively. Usage of the term ‘multi-lateral’ here requires definitional clarification. As Caporaso (1993: 54–5)and Ruggie (1993: 14) put it, multilateral suggests ‘many’ actors – anythingfrom a minimum of three to a maximum of all – but does not presupposeany specific numbers in a way unilateral, bilateral, or universal does.Further, it presumes cooperation, or coordinating activity, among actorson the basis of certain principles of conduct. The definition in this mostbasic sense, therefore, embraces both nominal and qualitative dimensions,and the two dimensions, on comparison, may hold different degrees ofweight depending on how actors apprehend the ‘multilateral’ as a form ofactions at a given time.

5

In this regard, Japanese policy-makers at the timesaw ‘multilateral’ with considerable weight placed on the nominal dimen-sion (in contrast to ‘bilateral’), precisely because such forms of activitiesfor dealing with regional politics and security had been almost non-existent under the predominant US-led bilateral arrangements. At thesame time, they naturally, if not with conscious deliberation, presuppose a‘cooperative’ nature of multilateral form – the qualitative dimension – asopposed to ‘hierarchical’, which is often connoted by the bilateral exercise.And, the Japanese policy-makers generally presumed ‘non-discrimination’and ‘transparency’ as basic principles of multilateral exercise, as Acharya(1997: 325) points out that such principles (non-discrimination and trans-parency) have been specifically incorporated in the multilateral exercisesin Asia.

The second point of significance is the ‘packaging’ formula adopted bythe multi-tiered approach.

6

By placing the bilateral security arrangements,namely the US–Japan alliance, in the top tier among four, the multi-tieredapproach clarifies the primary importance of defense and deterrence func-tions relative to other security functions. Meanwhile, by packaging thedifferent functions and arrangements into one framework, it also high-lights the increasing importance and desirability of the other three func-tions in order to collectively enhance regional security where newuncertainties are emerging, as in the periods of transition at the end of theCold War. In short, this packaging formula of a multi-tiered approachenables Japanese policy-makers to underscore the importance ofUS–Japan bilateral relations as well as to expand their policy-makinghorizons beyond bilateral relations with the United States. It affords thecountry more space to maneuver in foreign and security policy-makingtoward the region.

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 365 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

366

The Pacific Review

Conceiving and adopting a multi-tiered approach

The basic idea of a multi-tiered approach was first expressed in the writingof Satoh Yukio, then Director General of the Information and AnalysisDivision of the Foreign Ministry. In a special report published by theministry in 1991, Satoh conceptualized intra-regional collaborations andarrangements for regional security in Asia by using the term ‘multiplexmechanism’ (Satoh 1991a).

In explaining the multiplex mechanism, he started with economic co-operation activities including ASEAN and APEC, and then referred to themanagement of subregional conflicts and disputes such as the restoration ofthe Cambodian peace and the ongoing tension on the Korean Peninsula. Henext pointed out the existing bilateral security arrangements, including boththe alliances between the United States and other Asian countries as wellas the Soviet–Chinese military cooperation and Moscow’s military assist-ance to Hanoi and Pyongyang. Then, Satoh moved to a ‘political dialogue’process among states concerning regional security matters and emphasizedthat Asia was lacking this function. Here, he focused on the need for sucharrangements between major powers (namely the United States and Japan,according to his view at the time) and other newly industrialized and devel-oping countries. Along this line, he proposed the existing framework of theASEAN Post-Ministerial Conference (ASEAN-PMC, designed to discussprincipally economic cooperation between ASEAN and other participants)as ‘an ideal forum’ for the function of political and security dialogue amongconcerned countries (Satoh 1991a: 43).

7

Satoh’s perspective was soon to be presented at a major diplomatic venue.In a speech at the 1991 ASEAN-PMC Foreign Minister Nakayama officiallyproposed the idea of establishing a security dialogue among regionalcountries in a multilateral setting. Satoh’s paper served as a basis fordrafting Nakayama’s speech (personal interview, 15 and 23 February 2001,Tokyo). Nakayama used the term ‘multilayered’, to suggest to the audiencewhat the multi-tiered approach means:

Japan continues to maintain that the geopolitical conditions and stra-tegic environment of the Asia Pacific region are vastly different fromthose in Europe. . . . What the Asia Pacific region needs to do is, in thefirst instance, to ensure its long-term stability by utilizing the variousarrangements for international cooperation and fora for dialogue thatexist today in an integrated and

multilayered manner

.(Nakayama 1991, emphasis added)

In explaining the concept, Nakayama enumerated the three existing mech-anisms: a series of fora for economic cooperation, case-by-case frameworksfor dealing with different subregional problems, and bilateral securityalliances, notably the US–Japan security arrangement. Then he advanced

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 366 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

367

the proposal to create a forum for political dialogue – in addition to thosethree mechanisms – in order to improve a sense of security among countriesin the region. Nakayama stressed that using the ASEAN-PMC for thispurpose would be ‘meaningful and timely’.

The unenthusiastic reaction at the time to the Nakayama proposal fromthe ASEAN countries, as well as the United States, did not discourageJapanese foreign policy-makers from further developing this new approach,as one official rather solemnly said ‘we ventured to throw a stone’ (

NikkeiShimbun

, 23 July 1991, p. 1). The

Diplomatic Bluebook

published later thatyear dedicated two pages to discussing the concept of a multi-tieredapproach as Japan’s agenda for peace and security in the Asia-Pacific. Itdiscussed three different functions of economic cooperation, diplomaticcollaboration for subregional issues, and US–Japan bilateral securityarrangements, and then emphasized the need to engage in political dialoguefor additional functions through the ASEAN-PMC. It stated, ‘it will be mosteffective and realistic to utilize the various arrangements for internationalcooperation and forums for dialogue in an integrated and

multilayered

manner, in order to ensure the long-term stability of the region’ (MOFA1991: 71–2, emphasis added).

During the following year, the concept of a multi-tiered approach wasexpressed by Japan’s chief political leader. In his address to the NationalPress Club in Washington DC, Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa, first, asroutine procedure, began by stating the importance of the US–Japan bi-lateral relationship for Asian regional politics. Next, he talked about sub-regional issues, namely the tension on the Korean Peninsula andCambodian peace process, and the respective ongoing multi- or mini-lateralcooperation by regional countries for each case. He then moved on todiscussing the need to develop region-wide frameworks for politicaldialogue and stressed the appropriateness of using the ASEAN-PMC forthis purpose. Economic cooperation through the APEC forum was furtheradded (MOFA 1993: 403–10).

For highlighting the importance of the second and third functions –subregional arrangements for settling specific issues and a region-wideframework for political dialogue – Prime Minister Miyazawa used a newterm, ‘two-track approach’, which meant the subregional arrangements onone track, and region-wide dialogue on the other, for enhancing Asiansecurity simultaneously. Miyazawa’s emphasis on the subregional andregion-wide arrangements reflected Japanese foreign policy-makers’agenda at that time to bring Washington’s attention to the idea of real-izing a region-wide security dialogue, given particularly the negative USreaction to Nakayama’s proposal of the previous summer. Despite theemphasis on ‘two’ functions, Miyazawa’s speech did include all four func-tions the multi-tiered approach prescribes, and as Soeya (1993: 27)suggests, the ‘two-track approach’ can be seen as an abridged version ofthe multi-tiered approach. Further, three weeks later, in a statement at

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 367 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

368

The Pacific Review

the ASEAN-PMC, then vice-foreign minister Kakizawa (1992) once againexhibited the multi-tiered concept, by describing different frameworks ofregional cooperation already existing in ‘a multi-layered manner’.

The years 1993 and 1994 served as a period when the concept of a multi-tiered approach was refined in language, rooted firmly, and spread beyondthe inner circle of foreign policy-makers. In another major policy speech in1993 in Bangkok, Miyazawa (1993: 376) went through the list of differentfunctions for regional security – bilateral, subregional, and region-wide –and specifically pledged that Japan would ‘actively take part in . . . politicaland security dialogues among the countries in the region’. The 1992

Diplomatic Bluebook

, published in July 1993, spared four pages to describewhat the multi-tiered approach suggests, with a concise summary of theconcept in the introduction stating, ‘. . . for peace and prosperity in thisregion, it is especially important to maintain: first, the existence and engage-ment of the United States; second, diplomatic efforts to settle conflicts andconfrontation; third, promoting region-wide political dialogues; and fourth,promoting regional economic development’ (MOFA 1993: 31–5). Theconcept was gaining greater clarity.

Meanwhile, the concept of a multi-tiered approach began to spreadbeyond the inner circle of foreign policy-makers. Around this time, the term‘multi-tiered’ began to appear in newspaper articles discussing regionalsecurity issues (

Nikkei Shimbun

, 14 and 17 July 1993). For instance, in aneditorial on 27 July 1993,

Yomiuri Shimbun

defined the current frameworkof regional security in the Asia-Pacific as moving toward a ‘multi-tieredstructure’, and recommended the multi-tiered approach as practical andappropriate for current realities in the Asia-Pacific. Further, since the latterpart of 1993, the term ‘multi-tiered’ (or multiplex, sometimes) began to beused in speeches and comments at Diet sessions dealing with the securityand regional relations of Asia. Such usages were found not only in govern-ment officials’ statements, but also in those by representatives from oppo-sition parties as well as academics and specialists invited to testify beforethe Diet (Yanai 1993; Hata 1993; Yamada 1994; Kakizawa 1994; Sakanaka1994).

By early 1994, MOFA was ready to advance the concept of a multi-tieredapproach in a medium directly aimed at the general public. In consecutivevolumes,

Gaiko Forum

(the MOFA-sponsored monthly journal) carriedtwo articles that discussed the idea of the multi-tiered approach: the first byYukio Satoh (1994), then the director-general of the North AmericanAffairs Bureau, and the second by Tadashi Ikeada (1994), the director-general of the Asian Affairs Bureau. In the following year, Shunji Yanai(1995), the director-general of the Foreign Policy Bureau, again discussedthe multi-tiered approach in his

Gaiko Forum

article. Given that the ForeignPolicy Bureau was newly established in 1994 to formulate and superviseoverall Japanese foreign policy (and thus was placed above the otherbureaus such as the Asian and North American Bureaus), the reference to

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 368 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

369

the multi-tiered approach in the Yanai article can be seen as a reflection ofhow solidly, by the mid-1990s, the concept was adopted as a new guidelinefor Japanese foreign policy-making in Asia.

To be sure, some would see the multi-tiered approach as simply anexpedient to rationalize and promote the 1991 Nakayama proposal andsubsequent Japanese support to realize a region-wide security forum,namely the ARF, as an eventual form. Yet, tracing how the concept of amulti-tiered approach had been conceived and established, as shown above,indicates that it is more than a mere expedient. Although a series of refer-ences to a multi-tiered approach for the first two years did coincide with thecountry’s efforts to actualize a region-wide security forum, they were also acentral part of major diplomatic speeches, where the country’s overallforeign policy was presented. Further, the reference to a multi-tieredapproach continued even after the summer of 1993, when the Asia-Pacificcountries finally agreed to hold the first ARF meeting the next year. Asdiscussed in the following section, Japan’s introduction of a multi-tieredapproach did not take place casually, but it rather reflected conspicuouslythe opportunity and constraints the country faced in shaping its policyorientation toward Asian security.

Understanding the multi-tiered approach

Why did Japanese policy-makers in the early 1990s adopt a distinct form ofmulti-tiered approach as an overall conceptual framework for regionalsecurity policy-making? In order to adequately address this question, it firstneeds to be broken into two parts: (1) why did Japan seek a new approach,and (2) why did it select the particular design of a multi-tiered approach? Isuggest that the first question rests on two factors:

a perceived change in theregional security order in Asia

and Japan’s

increasing self-recognition ofmajor power status

. The second question deals with the

legacy of Japan’s pastaggression against Asian neighbors

on one hand, and the

peculiar constraintson Japan’s security policy posed by the Constitution

on the other. Theremainder of this article will examine Japan’s adoption of the multi-tieredapproach through this two-phased analysis.

Change in the regional security order and major power status

The first analysis of Japan’s motivation to seek a new approach involveslargely an international-level analysis. For a

change in the regional securityorder

and

major power status

– the two focal points here – are roughlycategorized as international-level factors, although perception and self-recognition (individual and non-material level elements) are closely associ-ated. In conducting this phase of analysis, I first specify what kind of inter-national level and what type of state to be examined: the international levelhighlighted in this study is a region of Asia, and Japan’s status is understood

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 369 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

370

The Pacific Review

as a regional power in the security realm and a global power in the economicsphere.

8

Specifying these particular points of focus helps us to understanda commanding function about how and to what extent international-levelfactors dictate state behavior, as shown below. In sum, the changing regionalorder, perceived by Japanese policy-makers on one hand, and the increasingself-recognition of the country’s major power status on the other, togethercreated imperatives for Japan to seek a new approach toward regionalsecurity in Asia.

In April 1990, the Bush administration published a report on the Asia-Pacific strategic framework that stated that the United States would reduceits force in East Asia by 14,000 to 15,000 personnel, including a 5,000 to6,000 personnel reduction from US bases in Japan by the end of 1992 (USDepartment of Defense 1990). This was the first comprehensive review bythe US government of its military policy toward Asia, since the dramaticevents of the late 1980s started unfolding in the Soviet Union and Europe.In addition to a first phase of force reduction over the next two years, thereport referred to the need for further reductions in the second and thirdphases. In the following months, some troops stationed in the bases ofOkinawa left for home or were disbanded, and the negotiation for down-sizing and possible US base closures in the Philippines began betweenWashington and Manilla.

Not surprisingly, Japanese policy-makers were seriously concerned withthis new development in US military policy toward Asia (for example,

Nikkei Shimbun

, 17 June 1990, p. 1). The 1990

Diplomatic Bluebook

published later that year expressed concern about a possible increase in USpressure for burden-sharing from its allies and a likely further change in theUS military posture in the region, as a result of US force reductions thatwere then under way (MOFA 1990: 12). Although the

Diplomatic Blue-book

’s language was careful enough not to overreact to this development(stating ‘it is understood’ that the US would maintain its commitment toregional security as a Pacific country), its symbolic and psychological impacton Japanese foreign policy-makers was hardly trivial. One MOFA officialexpressed that ‘it was a time that we seriously thought the United States wasturning its face away from Asia’ (personal interview, 15 February 2001,Tokyo).

The point here is, for Japanese foreign policy-makers, the US decision toreduce its military force in Asia posed a strong indication that a change inthe regional security structure was finally taking place. Tokyo saw the reduc-tion of US forces as possibly growing into a serious challenge to the funda-mental security structure, or order, in Asia – a long-standing hub-and-spokebilateral system led by the United States. The special attention on regionalsystems explains this logic. As Lake and Morgan (1997: 3–29) discuss,regional systems are not simply

mini

international systems, but systemswithin an international one. International systems (or global systems, inother words) are closed, whereas regional systems are naturally open.

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 370 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

371

Regions as open systems are not walled off from the external occurrenceand influence, and thus actions by outside global powers can occasionallyaffect particular regions directly. More important, hegemonic powers ofglobal international systems maintain constant influence over regions, andoften over regional orders as well, though the degree of such influencediffers across regions and over time (Boals 1970).

For Asia, the United States has been a hegemonic power, situated at thecore of the region’s security structure. Given the status of regional powersin the security realm, together with its unique reliance on the US securityguarantee, Japan has been receptive exclusively to US hegemonic powerwithin the regional security structure. For Japan, any change in US hege-monic behavior toward the region could possibly turn into a change of theregional security structure itself. This was exactly the case for Japan whenWashington announced force reductions in Asia. In the following months,Japan, for the first time, officially acknowledged that a wave of historicalchange finally reached the Asia-Pacific, in the

Diplomatic Bluebook

as wellas in a policy speech by the foreign minister before the Diet (MOFA 1991:382). This also explains why Japanese foreign policy-makers, in thepreceding years, appeared rather reluctant to recognize any significanteffects from the dramatic changes within the Soviet regime (and subsequentchanges in the Cold War bipolar system) on the regional structure and intra-regional relations in Asia,

9

failing to initiate no particular policy review inthe country’s overall foreign policy toward Asia throughout the late 1980s.

The ongoing withdrawal of US military forces from Asia served as a bigblow and urgent warning for Japanese foreign policy-makers about the realpossibility that a change in the regional security order in Asia was underway.Yet, such a recognition of possible change in the regional security order (theperceived change in the regional security order) does not automatically leadpolicy-makers to seek and formulate a new approach in their regionalsecurity policy. Japan, for instance, could have waited for the United States(as the hegemonic power) to define a new security structure in Asia, andsimply follow its lead. Or, given the continuation of the country’s relianceon the US security guarantee in the future, Japanese policy-makers mighthave simply concentrated on maintaining the hitherto security structure inthe region, by trying to lessen the effects of US force reductions on theregional structure itself. Instead, Japanese policy-makers sought a newapproach for conducting regional security policy, and by doing so, they putforward a vision for a new regional security structure. Here, Japan’sincreasing self-recognition of major power status – the second factor of thisphase of analysis – comes into play.

In the international system of the late 1980s, Japan reached the status ofa global power in the economic sphere, whereas in the security sphere it hadbeen a regional power throughout the Cold War period. Global powers canproject their policies outside the region to which they belong. In contrast,the impact of a regional power’s policy rarely extends beyond the boundary

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 371 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

372

The Pacific Review

of the region. Given its self-imposed limits on the country’s defense capa-bility and scope of its military activities, Japan has remained a regionalpower despite its relatively high defense budget and possession of sophisti-cated military equipment. This discrepancy in the power status betweeneconomic and security spheres was one of the chief reasons for Japan’s low-profile, reactive posture in its foreign policy-making; a posture thatremained well into the 1980s, when the world began to view Japan as a majorpower, or sometimes as an economic superpower. In the words of a formerMOFA official, ‘there was an obvious gap between our self-image of thecountry and the country’s actual position in international society, and it wasthe biggest problem for Japan in the 1980s’ (personal interview, 20December 2000, Tokyo).

At the end of the 1980s, however, Japan’s view of itself within the countryshifted. In his

Gaiko Forum

article published in May 1990, TakakazuKuriyama (1990: 16–17), then vice minister of MOFA, deliberatelyproclaimed Japan as a major power, following the United States andEuropean Community, and urged the country’s diplomatic posture to ‘tran-scend from small–middle power diplomacy to major power diplomacy’.

10

According to Kuriyama, a major power should be actively involved inbuilding a new order for a world in transition. Several months later, ForeignMinister Nakayama, in a speech before the Diet, also expressed this majorpower aspiration for building a new order, by stating ‘now, it’s a time toinitiate serious discussions on a new approach to maintaining long-termstability in the region’ (MOFA 1991: 383).

Japan’s desire to participate in major power diplomacy hastened dramat-ically by the experience of the Gulf War crisis between the summer of 1990and the early part of 1991. The crisis disclosed the serious inability ofJapanese leaders to respond quickly and aptly to this type of internationalcrisis, giving a tremendous shock to Japanese foreign policy-makers – calledliterally ‘Gulf Shock’. What was shocking for them was that the country’sUS$11 billion financial contribution to the multinational force did notreceive significant appreciation from other countries, including Kuwait. Anunprecedented level of pressure from Washington for a large Japanesecommitment, not only financially but also militarily, to the US-led multi-national force was another shock for Tokyo.

11

As Secretary of State JamesBaker (1991) later symbolically commented, ‘Your “checkbook diplomacy,”like our “dollar diplomacy” of an earlier era, is clearly too narrow’, itbecame clear among Japanese policy elites that they must urgently gobeyond their low-profile, economic-centered diplomacy in order to conducta more active, major power diplomacy with visible political and military, ifnecessary, roles in world politics (Kondo 1991).

Given the backdrop of a growing aspiration for major power diplomacy,Japan’s role for building a regional order in the Asia-Pacific began to beexpressed frequently among Japanese foreign policy-makers (Gaiko Forum1993: 50; Kunihiro 1991: 17; Satoh 1991b: 114). For Japanese elites at the

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 372 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

373

time, seeking a new approach toward the regional security of Asia was aparallel effort to advance their own perspectives for regional order, whichthey perceived acutely in a period of transition.

Legacy of history and constitutional constraints

What kind of approach, then, was Japan to adopt? Should the country, forexample, see the region as becoming volatile and multi-polar, and hence theneed to concentrate on a military build-up of its own, as realists (Betts 1993/94; Friedberg 1993/94) suggest? Here, we need to look at two other factors,the ‘legacy of history’ and ‘constitutional constraints’, that dictated Japan toformulate a particular form of approach – the multi-tiered approach –toward regional security in Asia.

When formulating foreign policy toward neighboring countries or theregion as a whole, Japanese policy-makers inevitably needed to give partic-ular consideration to the legacy of the country’s aggression against its Asianneighbors during the first half of the twentieth century. Until recently, Asiancountries that suffered from the belligerence of the Japanese imperial army,particularly South Korea and China, were extremely sensitive and stronglyopposed to any indications of resurgent militarism by the Japanese govern-ment and policy-makers. For example, they criticized Japan’s launch ofsatellites by the Ministry of Education for purely civilian use, on groundsthat a rocket system used for the launch could be also used for militaryrockets in the future. As a result, making certain changes in the defense andregional policy required giving particular consideration to the strong senti-ments of neighboring Asian countries. The legacy of history served effec-tively as a check on Japan from taking diplomatic initiatives that havemilitary implications.

This constraint, thus, came into play when Japanese foreign policy-makers began to explore a new approach to the country’s policy-makingtoward Asia. The ongoing reduction of American military forces in Asia,including from Japan, raised new misgivings across Asia that Japan, now aneconomic giant, would seek to establish a more independent militarypower. The Asian neighbors also feared that Japan would aim to fill thepower vacuum created by US force withdrawals and to become a dominantpower, not only economically but politically in Asia. These voices havebeen heard increasingly from those countries in various media reports, andeven in comments by high-ranking government officials (

Nikkei Shimbun

,29 July 1990, p. 2;

Asahi Shimbun

, 5 May 1990, p. 3;

Asahi Shimbun

, 20October 1990, p. 3).

Having keenly recognized these voices among Asian countries, Japanesepolicy-makers sought measures to calm such growing misgivings (GaikoForum 1991: 12–15). A new approach toward regional security, underconsideration at that time, needed to incorporate functions that keep Asianneighbors assured that Japan would refrain from becoming a military

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 373 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

374

The Pacific Review

power. Accordingly, creating multilateral fora and activities with othercountries in the region became desirable measures for that purpose, sincesuch multilateral frameworks would play a kind of insurance role for Asianneighbors. As termed by Sansoucy (2002: 168), a ‘self-binding’ effect couldbe expected by placing Japan within a rather complex multilateral environ-ment that helps deter a member state from taking antagonistic actionsagainst other member states. Different types of multilateral frameworks,region-wide, subregional, security-focused, and non-security, should be allencouraged in order to embed Japan in such complex networks of intra-regional relations in Asia. A multilateral forum for security dialogue wouldbe a particularly useful framework to achieve, as it would offer opportuni-ties for Japan to tell its neighbors directly that Japan would not seek to bea dominant power again. In this context, the legacy of history compelledJapan to incorporate various multilateral frameworks, particularly a region-wide forum for security dialogue, into a new approach for general policy-making toward regional security in post-Cold War Asia.

Japan’s historical legacy, however, did not alone determine the substanceof its multi-tiered approach. Peculiar constraints posed by the Constitutionover the country’s security policy-making was another factor that helpedshape the direction for formulating a new approach toward regionalsecurity. Article 9 of the Constitution is the essential element within theconstitutional framework that constrains the conduct of Japan’s securitypolicy. It renounces war as a sovereign right of the country and rejects theuse of force as means for settling disputes among nations. Article 9 hasraised serious controversies about the legal grounds and functions of theSelf-Defense Force (SDF), particularly in the early years of the post-warperiod. Through a series of Article 9 ‘reinterpretation processes’ (to avoidpolitical catastrophes), the legality for the right of self-defense and for theexistence of SDF came to be accepted by most Japanese. Yet, this processalso brought about a general consensus that Article 9 does not allow Japanto possess a full-fledged military, and that the scope of the SDF’s activitiesshould be limited within the country’s territorial area.

12

Furthermore, the‘normative constraints’ that are associated with Article 9 also made it seem-ingly impossible ‘to build nuclear weapons or to agree to their deploymenton Japanese soil; to dispatch Japanese troops abroad in combatant roleseven as a part of an international peacekeeping force; to sell weaponsabroad; or to raise the Japanese Defense Agency (JDA) to ministerialstatus’ (Katzenstein and Okawara 1996: 285–6).

To be sure, the Constitution itself is not absolute or final, but subject toamendment as an established procedure of national policy-making. Article9, however, has assumed a symbolic significance, becoming more than justan article of the Constitution, and thus is extremely hard to amend oreliminate, due to complex interactions among domestic political struggles,memories of past, public sentiments, ideological propensities, and intellec-tual pursuance in Japanese society. As a result, the constraints associated

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 374 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

375

with Article 9 have established an almost independent effect on the conductof Japan’s security policy.

When Japanese foreign policy-makers explored a new approach towardregional security in the early 1990s, therefore, the particular Constitutionalconstraints worked, along with the legacy of history, in helping to determinethe direction and substance of the approach under consideration. Above all,they informed the view that the option of a unilateral military build-up foracquiring a more independent defense capability should be out of thequestion. This restriction on the posture of the SDF then pointed to thecontinued indispensability of the US–Japan bilateral alliance for Japan’soverall conduct of security policy, despite the ongoing collapse of the SovietUnion, against which the alliance was formed four decades before.Although there were voices against the continuation of Japan’s exclusivereliance on the bilateral alliance with the United States, the mainstreamJapanese foreign policy circle unanimously agreed in its indispensability,and repeatedly it called for the further strengthening of this bilateralalliance to deal with increasing uncertainties stemming from the region’stransition (Kitaoka 1991; Kuriyama 1991; Morimoto 1991). Accordingly, anew regional approach should incorporate functions that maintain theimportance of the US–Japan alliance.

13

This requirement to ensure the indispensability of the US–Japan alliancehelped determine an important feature of the multi-tiered approach: the‘packaging’ formula that arranges a hierarchical relationship among thedifferent functions in a layered manner and places the bilateral arrange-ments at the top. With bilateral arrangements placed on the first tier offunctions, the indispensability of US–Japan security cooperation was reas-sured. As discussed in the earlier section, the concept of the multi-tieredapproach also clarifies the primacy of the US–Japan bilateral alliance’sfunction – defense and deterrence against external security threats. Further-more, the need to ensure strong bilateral relations with the United Statesalso encourages the introduction of multilateral arrangements as usefulfunctions. It suggests that region-wide multilateral fora, as well as sub-regional arrangements that include the United States, will engage theUnited States institutionally as an Asia-Pacific country to help keep theUnited States anchored in Asia. ‘Keeping the United States in Asia byengaging it in regional multilateral frameworks’ was a view shared by manyforeign policy elites in Tokyo at the time (Nakanishi 1991; personal inter-view, 15 and 26 February 2001, Tokyo).

As shown above, the two-phased analysis helps to understand how par-ticular factors (at both international and domestic levels) operate on specificelements of the policy-making process. When the US decision to reduceforces in Asia made Japanese policy-makers suddenly aware that a changein the regional security order was under way, the self-recognition of majorpower status by Japanese policy-makers led them to play an active role inregional order building. To do so, they needed to conceptualize a new

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 375 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

376

The Pacific Review

approach for their foreign policy-making toward the region. In the processof conceptualization, the legacy of history and constitutional constraintstogether informed Japanese policy-makers of the desirable composition andcontents of a new approach. More precisely, the historical legacy mainlyinformed Japanese foreign policy officials about the usefulness of multi-lateral groupings and activities, while the constitutional constraints largelyinfluenced the hierarchical composition of the new approach, placingdifferent functions at different levels for collectively maintaining regionalsecurity. The result was the particular packaging style of the multi-tieredapproach.

On the surface, the multi-tiered approach does not appear entirely novel,because in a sense it can be described as basically summarizing the arrange-ments and frameworks that already existed in the region, except for thethird-tier function of a region-wide forum for security dialogue, as YukioSatoh himself pointed out (personal interview, 26 February 2001, Tokyo).Yet, in terms of past Japanese foreign policy conduct that was oftendescribed as reactive, Japan’s introduction of a multi-tiered approach canbe safely seen as novel, precisely because it presents those different arrange-ments in an original, packaging formula. The multi-tiered approach reflectsthe increasing desire of Japanese policy-makers to advance original, ‘made-in-Japan’ perspectives in a visible manner, rather than simply to follow aframework that was designed elsewhere and transplanted into Japaneseforeign policy. As one MOFA official involved in the process said, ‘I saw theconcept of multi-tiered as something beyond the hitherto hub-and-spoke’(personal interview, 15 February 2001, Tokyo).

14

Conclusion

Japan’s unceasing efforts to promote multilateral arrangements for regionalsecurity during the past few years, with the latest example being the JDASecretary General’s proposal for a defense ministers’ region-wide forum,confirm that the multi-tiered approach remains at work. The 2002

Diplo-matic Bluebook

, the latest one at the time of this writing, specifically refersto the ‘promotion of multi-layered regional cooperation in the Asia-Pacific’as a major agenda for Japanese diplomacy (MOFA, 2002, 44–51). If we alsoinclude similar efforts in the economic sphere, as prescribed in the fourthtier of the multi-tiered approach, as well as Track II multilateral arrange-ments that the Japanese government has openly supported, the number ofthese activities is far from modest.

15

Yet, in some sense, there remains theimpression that Japan put forward those new proposals almost instinctivelywith little internal deliberation. Further, many observers sometimes wonderwhy Japan continues to make such proposals, despite a continuous criticismof effectiveness and significance about multilateral arrangements fordealing with vital issues, and despite the obvious decline in Japan’seconomic power to support financially the country’s activism in regional

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 376 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

377

institution-building. These perplexed views can nevertheless be understoodin the context of the country’s adoption of the multi-tiered approach.

Furthermore, and probably more important, Japan’s introduction of amulti-tiered approach explains the country’s effort to not just maintain butstrengthen its bilateral alliance with the United States. Such efforts culmi-nated in the Clinton–Hashimoto joint announcement of ‘the US–Japan JointDeclaration on Security’ in 1996, and in the subsequent conclusion of thenew Guidelines for US–Japan Defense Cooperation in 1997. Along similarlines, the Japanese government has tried lately to loosen some restrictionson the SDF’s activities in order to cooperate militarily with Washington,particularly after the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack against the UnitedStates. As discussed, it is precisely the characteristic ‘packaging formula’ ofthe multi-tiered approach that has led Japan to

simultaneously

promoteregional multilateral arrangements and strengthen the US–Japan bilateralrelationship.

While the introduction of a multi-tiered approach has helped Japan toexpand foreign policy options, the growing options from different frame-works influence the country’s foreign policy-making both positively andnegatively. On the positive side, it offers Japanese foreign policy-makersmore space to maneuver in their foreign and security policy-making towardthe United States as well as other countries in Asia, including China andSouth Korea. In this sense, it could help Japan to become more ‘normal’, asEllis Krauss suggests in this issue in relation to Japan’s economic foreignpolicy. By the same token, growing options also offer more opportunitiesfor Japan to play active leadership roles in its foreign policy conduct.

On the negative side, the more diverse the frameworks, the more negoti-ation and diplomatic maneuvering skills Japan must develop. Diplomaticbargaining in multilateral settings tends to be more difficult to control thanin bilateral ones, and different compositions of member states bear differentenvironments and conditions, to which such bargaining skills need to beadjusted. The framework of ASEAN+3, for instance, is a case in point sincethis framework – lacking a US presence – would inevitably lead Japan toconfront the possibility of China’s dominance, particularly if its subject focusmoves forward to include regional security matters as Japan has alreadyproposed, as a high-ranking MOFA official expressed this concern (personalinterview, 18 May 2002). Given the country’s decreasing relative power

vis-à-vis

China due to economic stagnation over the past decade, Japan’s waninginfluence in such complex settings warrants serious attention.

Lastly, Japan’s formulation of a multi-tiered approach reflects the incre-mentalist and pragmatic nature of Japan’s foreign policy-making. It isincrementalist because the multi-tiered approach does not completelydiscard the previous approach – hub-and-spoke bilateralism – but ratherevolves from it by maintaining the US–Japan bilateral alliance as one of thecore functions. It is also pragmatic, because by using the term ‘multi-tiered’,this approach keeps all other possible arrangements open for Japan’s future

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 377 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

378

The Pacific Review

policy-making. Asian-only groupings like ASEAN+3 and bilateral securityarrangements between Japan and other Asian countries, both of which werenot openly discussed in the original formulation of the multi-tieredapproach, are examples of such arrangements. In fact, as Katzenstein andOkawara (2001: 172–3) discussed, JDA has already initiated several bi-lateral security talks at senior-official levels with other Asian countries,including China, Australia, Singapore, and Indonesia. To be sure, given howthe legacy of history and constitutional constraints together informedJapanese policy-makers of the distinct packaging design of the multi-tieredapproach, such incrementalist and pragmatic characteristics made sense forJapan. For as long as these two domestic factors weigh significantly onJapan’s security policy-making process, the features of incrementalism andpragmatism will most likely persist.

Acknowledgements

For the many helpful comments during meetings held at the Institute ofSocial Science, University of Tokyo, I would like to express my thanks to allparticipants, especially Reinhard Drifte, Kiichi Fujiwara, Atsushi Ishida,Ellis Krauss and Robert Uriu. I am also grateful to the Japanese govern-ment officials, both former and current, who generously shared their timeand experience with me. The field research for this article was made possibleby a fellowship from the United Nations University, Institute of AdvancedStudies.

Notes

1 Since the mid-1990s, MOFA officials began to openly discuss the desirability ofestablishing a multilateral security framework for Northeast Asia. Before thisperiod, they were considerably hesitant to discuss such issues in a clear manner.

2 This is an interesting contrast to regional economic relations, where Japandeveloped several bilateral contacts with other Asian countries, mainly underits ODA activities.

3 The multi-tiered approach may be still seen as a kind of ideational factor, suchas road maps, in a somewhat more moderate use of the term ‘idea’ in examiningforeign policy-making, as suggested by Goldstein and Keohane (1993). But forsuch a case, the focus should be on the much longer-term impact of the multi-tiered approach on Japan’s policy-making, rather than on its formation andinception. This study’s focus is on the latter.

4 I use ‘multi-tiered’ here as synonymous with ‘multi-layered’ or ‘multi-leveled’.In the Japanese documents I examined, it is usually referred to ‘

juso-teki

’ andsometimes ‘

taso-teki

’, which is synonymous with the former. As shown below,the official English translations in MOFA documents also use both ‘multi-layered’ and ‘multi-tiered’, as a translation of ‘

juso-teki

’.5 Ruggie (1993: 6–7) differentiates the ‘nominal’ and ‘qualitative’ dimensions in

his discussion on the concept of ‘multilateralism’. It should be noted that theterms ‘multilateral’ and ‘multilateralism’ differ in terms of the definitionalconsiderations, though existing literatures sometimes employ the two termsrather interchangeably. As Caporaso (1993: 55) suggests, multilateralism, asopposed to multilateral, is ‘an ideology designed to promote multilateral

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 378 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

379

activity’ and that ‘it combines normative principles with advocacy and existentialbeliefs’; the term ‘multilateralism’ by nature implies larger emphasis on thequalitative dimension compared to the nominal dimension than the term ‘multi-lateral’ does. As shown, the discussion in this paper concentrates on ‘multi-lateral’, not on ‘multilateralism’, as an adjective for describing particular formsof actions and, thus, the emphasis on the qualitative dimension is far morelimited than the existing literature on multilateralism.

6 I am grateful to Saori Katada for pointing out this ‘packaging’ character of themulti-tiered approach to be noted.

7 The members of ASEAN-PMC at that time included ASEAN countries, Japan,the US, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Korea, and the EU. It was theextension of the foreign ministers’ meeting between Japan and ASEAN thatbegan in 1978, where the Japanese foreign minister joined at the end of theannual meetings of ASEAN foreign ministers (AMM). In the following year,ASEAN expanded this meeting with additional countries (such as the US andAustralia) and came to name it ASEAN-PMC. Although they had ceremonialmeetings, such as opening and closing sessions, where all participants werepresent, the main meetings were taken essentially as bilateral-basis betweenASEAN and each country, and therefore they did not function as multilateraldialogues in a substantial manner. Absence of China and Russia (eventualmembers of the ARF) in ASEAN-PMC does not mean that Satoh’s perspectiveof region-wide multilateral dialogue excluded the two countries; he thought theinclusion of two countries should be realized at a gradual pace (personal inter-view, 26 February 2001, Tokyo).

8 The international level of analysis, mainly advanced by structural realists andsome liberals focusing on the interdependence phenomenon, is often criticizedas indeterminate when discussing in what direction the structure of an inter-national system would shape a particular state’s behavior. This is partly due toa lack of specification of the difference between the global international systemand regional system, as well as the clarification of a state’s status. I try to clarifythese points in dealing with international-level factors in this study.

9 Within MOFA, officials differed among themselves, especially between Chinaspecialists and Soviet specialists, about how and to what extent the change inSoviet regime would affect the communist regimes in Asia. As a result, they hadnot yet reached a consensus on whether Asia could benefit from the Soviet’schange (personal interviews with Sakutaro Tanino, then director-general ofAsian Affairs Bureau, 26 May 2001, Tokyo, and Nagao Hyodo, then director-general of Eurasian Affairs Bureau, 26 January 2001, Tokyo).

10 For an interesting comparison, in another article written two years before this,Kuriyama (1988) defined Japan as an ‘economic major power’ whose contribu-tion to the world should be through supporting UN peace efforts, promotingcultural exchange, and ODA – apparently limited to low-profile, less political,non-military activities.

11 The US pressure for military contributions, such as logistical support for USforces deployed and a minesweeping operation in the Persian Gulf, posed animportant implication for Japanese policy-makers in terms of US militarycommitments in Asia. The logic was: if a similar crisis happens in Asia, the USwill again demand that Japan make a military contribution as the US may nolonger be a generous guardian for Asia as during the Cold War. Such a prospectrepresented another sign of US military force reductions in Asia, and thus wastaken very seriously by Japanese elites, particularly defense communities.

12 In reality, the definition of home territory has gradually been widened from thenarrowly-defined land plus territorial waters and air spaces to including sea andair spaces surrounding Japan, and so was the definition of ‘self-defense’. Yet, the

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 379 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

380

The Pacific Review

languages themselves have symbolic importance to place limits on Japan’ssecurity policy-making.

13 In addition to the ongoing US force reductions in Asia, Japanese policy-makerswere also concerned with growing anti-America and anti-Japan feelings amongboth societies, caused by the aggravating trade imbalance between the twocountries and Gulf War experience, as serious problems for maintaining theUS–Japan relationship in the future (Ogura 1991). For the growing voice of anti-American feeling among the Japanese intellectuals and public, for example, seeVoice (1991).

14 In a sense, the multi-tiered approach was built upon the hub-and-spoke frame-work, not in opposition to it. It may be termed ‘hub-and-spoke

plus

’, and having‘plus’ stands out as different from that without ‘plus’.

15 The latest Japanese initiative related to economic issues is Prime MinisterKoizumi’s proposal for a ministerial-level forum among ASEAN+3 members on‘development cooperation’ (thus, essentially on Japan’s ODA policy), named‘the Initiative for Development in East Asia (IDEA)’ in January 2002. The firstIDEA ministerial meeting (of foreign and development ministers) was held on12 August 2002 in Tokyo. For more on Track II security multilateral arrange-ments and Japan, see Katzenstein and Okawara (2001: 178–9).

References

Acharya, Amitav (1997) ‘Ideas, identity, and institution-building: from the “ASEANway” to the “Asia-Pacific way”?’,

The Pacific Review

10(3): 319–46.Baker, James A. (1991) ‘“The US and Japan: global partnership in a Pacific commu-

nity”, Remarks before the Japan Institute for International Affairs, Tokyo,November 11, 1991’,

US Department of State Dispatch

2(46).Betts, Richard K. (1993/94) ‘Wealth, power and instability: East Asia and the United

States after the Cold War’,

International Security

18(3): 34–77.Boals, Kay (1970) ‘The concept of “subordinate international system”: a critique’, in

Richard A. Folk and Saul H. Mendlovitz (eds)

Regional Politics and WorldOrder

, San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, pp. 399–411.Caporaso, James A. (1993) ‘International relations theory and multilateralism: the

search for foundations’, in John Gerard Ruggie (ed.)

Multilateralism Matters:The Theory and Praxis of an Institutional Form

, New York: Columbia Univer-sity Press, pp. 51–90.

Checkel, Jeffrey T. (1998) ‘The constructivist turn in international relations theory’,

World Politics

50: 324–48.Friedberg, Aaron L. (1993/94) ‘Ripe for rivalry: prospects for peace in a multipolar

Asia’,

International Security

18(3): 5–33.Gaiko Forum (1991) ‘Zadankai: posuto-reisen to ajia taiheiyo no shinchouryu’

[Roundtable: Post-Cold War and new current of Asia-Pacific],

Gaiko Forum

(February): 12–25.—— (1993) ‘Zadankai: moromerareru aidea to takumashisa’ [Roundtable: a pursuit

for new ideas and vigorousness],

Gaiko Forum

(October): 50–62.Goldstein, Judith and Keohane, Robert O. (1993)

Ideas and Foreign Policy: Beliefs,Institutions, and Political Change

, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.Hata, Tsutomu (1993)

The Statement at International Security Committee, House ofRepresentatives, 128th Diet session, 19 November 1993

.Ikeda, Tadashi (1994) ‘Ajiashugi denai ajiagaiko wo’ [Foreign policy toward Asia,

not Asian-ism],

Gaiko Forum

(February): 52–60. —— (1998)

The Road to Peace in Cambodia: Japan’s Role and Involvement

, Tokyo:The Japan Times.

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 380 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

K. Ashizawa: Japan’s approach toward Asian regional security

381

International Institute for Strategic Studies (2002) ‘Perspective on the multilateralsecurity cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region, a speech addressed at theInternational Institute for Strategic Studies Asia Security Conference: TheShangri-La Dialogue, Singapore June 2’ (http://www.iiss.org/newj.php?cat=6>[downloaded 29 August 2002]).

Kakizawa, Koji (1992) ‘Statement by His Excellency Mr Koji Kakizawa, Parliamen-tary Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs to the General Session of the ASEANPost Ministerial Conference, Manila, 24 July 1992’, in Susumu Yamakage (ed.)

ASEAN Shiryo Shusei

[

Compilation of ASEAN Documents

],

1967–1996 (CD-ROM, 1999), Tokyo: Nihon Kokusai Mondai Kenkyujo.

—— (1994) The Statement at International Security Committee, House of Represent-atives, 129th Diet session, 30 May 1994.

Katzenstein, Peter J. and Okawara, Nobuo (1996) ‘Japan’s national security: structure,norms, and politics’, in Michael E. Brown, Sean M. Lynn-Johns and Steven E.Miller (eds) East Asian Security, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 265–99.

—— and Okawara, Nobuo (2001) ‘Japan and Asia-Pacific security: regionalization,entrenched bilateralism and incipient multilateralism’, The Pacific Review14(2): 165–94.

Kitaoka, Shinichi (1991) ‘Kanjoteki na hanbei-ishiki wo dasseyo’ [Escape fromemotional anti-US attitude], Gaiko Forum (February): 73–5.

Kohno, Masaharu (1999) Wahei Kousaku [Peace Making], Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. Kondo, Seiichi (1991) ‘Nihon wa gaikou-taikoku ni nareruka’ [Can Japan achieve

major power diplomacy?], Gaiko Forum (October): 69–80.Kunihiro, Michihiko (1991) ‘Shonenba ni tatsu nihon no kokusaikyocho: shin-

sekaichitsujo no kouchiku ha kanouka’ [Japan’s international cooperation atthe crucial point: is building a new world order possible?], Gaiko Forum(October): 13–17.

Kuriyama, Takakazu (1988) ‘Sekininaru keizaitaikoku eno michi’ [A road to respon-sible economic major power], Gaiko Forum (January): 32–9.

—— (1990) ‘Gekido no 90-nendai to nihongaiko no shintenkai’ [The tumultuous’90s and Japan’s foreign policy in new turn], Gaiko Forum (May): 12–21.

—— (1991) ‘Sekai-shinchitsujo no naka no nichibei-kankei’ [Japan–US relations inthe new world order], Gaiko Forum (November): 16–26.

Lake, David A. and Morgan, Patrick M. (1997) Regional Orders: Building Securityin a New World, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), Japan (1990) Gaiko Seisho: Waga Gaiko-noKinkyo, 1990-nen ban [Diplomatic Bluebook: Current Conditions of OurDiplomacy, 1990], Tokyo: Ohkurasho Insatsukyoku.

—— (1991) Gaiko Seisho: Waga Gaiko-no Kinkyo, 1991-nen ban [Diplomatic Blue-book: Current Conditions of Our Diplomacy, 1991], Tokyo: OhkurashoInsatsukyoku.

—— (1993) Gaiko Seisho: Tenkanki no Sekai to Nihon 1992 [Diplomatic Bluebook:World in Transition and Japan, 1992], Tokyo: Ohkurasho Insatsukyoku.

—— (2000) ‘ASEAN+3 shuno-kaidan deno mori-souri suteitomento [PrimeMinister Mori’s statement at the ASEAN+3 summit meeting in Singapore]November 24’ (http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko//kaidan/s_mori/asean00/state_1html [downloaded, 21 May 2002]).

—— (2002) Diplomatic Bluebook, Tokyo: Okurasho Insatsukyoku.Miyazawa, Kiichi (1993) ‘The new era of the Asia-Pacific and Japan–ASEAN co-

operation, policy speech by Prime Minister Miyazawa, Bangkok, 16 January1993’, ASEAN Economic Bulletin 9(3): 375–80.

Morimoto, Satoshi (1991) ‘Nihon no anzenhosho-seisaku “1990-nendai niokeruShuyo-kadai”’ [Japan’s security policy ‘major challenges in the 1990s’], GaikoJiho (October): 4–28.

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 381 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM

382 The Pacific Review

Nakanishi, Terumasa (1991) ‘Nichibei gassaku no ajia shinchitsujo: reisengo no ajiani katusryoku wo fukikomu nihongaiko no aojashin’ [US–Japan collaborationfor a new order of Asia: a blueprint for Japan’s foreign policy to vitalize post-Cold War Asia], Voice (August): 162–74.

Nakayama, Taro (1999) ‘Statement by His Excellency Dr Taro Nakayama, Ministerof Foreign Affairs of Japan to the General Session of ASEAN Post MinisterialConference, Kuala Lumpur, July 22, 1991’, in Susumu Yamakage (ed.)ASEAN Shiryo Shusei 1967–1996 [Compilation of ASEAN Documents1967–1996] (CD-ROM), Tokyo: Nihon Kokusai Mondai Kenkyujo.

Ogura, Kazuo (1991) ‘Rinen no teikoku to soushitsu no tami tono kiretsu: nichibei-masatsu to gyappu no shinso’ [The rupture between Japan and the UnitedStates – exploring the communication gap between a disoriented people andan idealistic empire], Gaiko Forum (June): 4–11.

Ruggie, John Gerald (1993) ‘Multilateralism: the anatomy of an institution’, in JohnGerald Ruggie (ed.) Multilateralism Matters: The Theory and Praxis of anInstitutional Form, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 3–47.

—— (1998) Constructing the World Polity: Essays on International Institutionaliza-tion, New York: Routledge.

Sakanaka, Tomohisa (1994) The Statement at Budget Committee, House of Council-lors, 129th Diet session, 20 June 1994.

Sansoucy, Lisa J. (2002) ‘Japan’s regional security policy in post-Cold War Asia’, inMatthew Evangelista and Judith Reppy (eds) The United States and AsianSecurity, Occasional Paper #26, Ithaca, NY: Cornel University Peace StudiesProgram, pp. 160–75.

Satoh, Yukio (1991a) ‘Asian-Pacific process for stability and security’, in Ministry ofForeign Affairs Japan (ed.) Japan’s Post Gulf International Initiatives, Tokyo:MOFA, pp. 34–45.

—— (1991b) ‘Reduction of tension on the Korean Peninsula: a Japanese view’,Korean Journal of Defense Analysis (Summer): 101–15.

—— (1994) ‘1995-nen no fushime ni mukatte: ajia-taiheiyo chiiki no anzenhosho’[Toward the year of 1995: Asia-Pacific regional security], Gaiko Forum(January): 12–23.

Soeya, Yoshihide (1993) ‘Reisengo no ajia-taiheiyo to nihongaiko’ [Asia-Pacific andJapan’s foreign policy in the post-Cold War], Gaiko Jiho [Foreign Affairs TimeSignal] (1294): 18–31.

US Department of Defense (1990) A Strategic Framework for the Asian Pacific Rim:Looking toward the 21st Century: The President’s Report on the US MilitaryPresence in East Asia, Washington, DC: Department of Defense, Office ofInternational Security Affairs.

Voice (1991) ‘Soutokushu: nichibei kankei wa aratana kyokumen wo mukaeta: imanaze kenbei ka’ [Special report: the US–Japan relations facing a new phase:why kenbei now?], Voice (August): 72–115.

Wendt, Alexander E. (1999) Social Theory of International Politics, Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Yamada, Kenichi (1994) The Statement at Foreign Affairs Committee, House ofCouncillors, 129th Diet session, 15 May 1994.

Yamazaki, Ryuichiro (1999) ‘Reisengo no shuyo-kokukan no bouei-kyoryoku’[Defense cooperation among major countries in the post-Cold War era],Gaiko Forum [Foreign Affairs Forum] (April): 70–5.

Yanai, Shunji (1993) The Statement at Foreign Affairs Committee, House of Council-lors, 128th Diet session, 10 November 1993.

—— (1995) ‘Reisengo no wagakuni no anzenhoshoseisaku: kokusaikankyo nohenka to sono eikyo’ [Japan’s post-Cold War security policy: change in inter-national environment and impact], Gaiko Forum (July): 44–50.

04 PRE 16-3 Ashizawa (JB/D) Page 382 Monday, June 23, 2003 3:00 PM