It Was the Plants that Told Us - PsyArXiv

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of It Was the Plants that Told Us - PsyArXiv

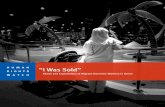

It Was the Plants that Told Us:

An Ethnographic Analysis into Amazonian Knowledge Transmission

Rebekah Senanayake

Centre for Applied Cross-Cultural Research, School of Psychology, Victoria University ofWellington, Wellington, New Zealand

1

Introduction

“The typical Amazonian shaman thus served not only as physician but also as priest,

pharmacist, psychiatrist, and even psychopomp – one who conducts souls to the

afterworld” (Plotkin 1993, 96)

Traditional plant medicines have been routinely used by indigenous groups across the

world to treat a range of illnesses including mental, physical and spiritual maladies (Labate,

2014; Lanaro et al., 2015; Laurent & Jan-Erik, 1972; Spess, 2000). Through the ingestion of

psychoactive plants, the healer is able to traverse through metaphysical plains to connect with

ancestral spirits, to gain information on the cause of the disease and how to cure the patient

(Dobkin de Rios, 1992; Katz, 1999; Labate, 2014). Furthermore, the visionary states induced

through the intake of entheogens have been historically used to gain insight into other realms,

where vital information regarding individual and societal development is believed to be held

(Lamb, 1974; Narby, 1998; Some, 1995).

Amazon mythology from the Tukanoan people of the northwest Amazon suggest that a

serpent canoe carried their ancestors from the Milky Way. In the canoe were the three plants

necessary for life on Earth: ayahuasca, to enable them to communicate with the spirit realm;

coca, an energy stimulant to enable them to work and hunt without fatigue; and yuca

(cassava) for sustenance (Plotkin, 1993).

Ayahuasca (in Quechua; “vine of the soul”) is a hallucinogenic tea typically found in

the Amazon rainforest of Latin America made from the vine Banisteriopsis caapi and

typically mixed with the leaves of chacruna (Psycotria viridis). Ayahuasca induces deep

hallucinatory states, and has strong purgative effects such as vomiting and/or diarrhoea (Grob

et al., 1996; D. McKenna, 2004). Ethnographies from various parts of the Amazon describe

the use of ayahuasca to enter into visionary states where the individual gains insight into

2

themselves, and how they can be a better human as well as insights into their community and

how to resolve conflicts that may arise (Narby, 1998; Plotkin, 1993).

This project is exploratory in nature and seeks to gain a wider understanding of the role

of ayahuasca in Peruvian Amazonian communities. Building from the ground up, I sought to

understand ayahuasca from the Peruvian’s point of view – rather than what has been imposed

by the recent influx of Western scientists and tourists to the Amazon. What resulted, was me

beginning to see through ayahuasca’s eyes.

Over the course of three months, I conducted ethnographic research in the Amazon

jungle of Peru. I stayed with traditional medicine healers in various regions of the jungle to

firstly, understand the culture itself and secondly, to understand the role of ayahuasca within

each community. My primary methodology was participant observation, which enabled me to

enter into the rhythm of the community whilst maintaining my anthropological lens. Within

participant observation, I used techniques from deep hanging out - a more informal

methodology, which requires the researcher to develop more casual relationships with the

community (Geertz, 1998) and is more suited to the relaxed nature of the jungle. To

understand ceremonial construction, I borrowed perspectives from ethnomethodology.

Ethnomethodology seeks to understand the building blocks of how experiences are created

(Coulon, 1995).

Upon return I used extensive memory work to translate my fieldnotes into analytical

findings. Through the use of sight such as smell, sound and sight, I attempted to transport

myself back into the ceremonial setting to produce research reflective of that state of

consciousness. I adopted techniques suggested by entheogenic researcher Christopher Bache

(2020) to assist me with translating these experiences.

3

This thesis focuses primarily on the transmission of knowledge and plant agency.

Although other major themes of healing/illness, religion/divination, witchcraft, love magic

and societal co-operation arose they are beyond the scope of this thesis, and will be used in a

Masters or PhD research project.

Background

“During indigenous ritual enactment, the cosmology opens up to include all people in

the universe, living and dead, Indian and non-Indian, together with animal spirits and

souls” (Labate 2014, p. 7)

A commonly held perspective in Amazonian communities is that of ayahuasca as the

grandmother or mother of the jungle (Labate, 2014) In this sense, ayahuasca acts as a ‘wise

elder’ providing communities with insights beyond their everyday realm of comprehension to

help them lead more harmonious lives – as individuals and a community. Multi-natural

perspectivism (Castro, 1998) is an ontological perspective held by certain indigenous

communities in the Amazon. Anthropologist Daniela Peluso (2004) has conducted dream-

narrative analysis with the Ese Eja in the South-west Peruvian Amazon to investigate notions

of agency and personhood in non-ordinary states of consciousness. Here, everyday waking

reality and metaphysical realities weave together seamlessly in both the dream world and the

visionary states induced by psychoactive plants. These non-ordinary states of consciousness

are believed to carry valuable information for a harmonious existence in ordinary reality

(Peluso, 2004). Agents within this domain (plants, animals, dream archetypes) are believed to

carry the same agentic attributes as those within everyday waking reality (Peluso, 2004). The

information accessed in these states is acknowledged to be highly informative providing

communities with crucial and valuable insights into one’s existence, the natural world and the

human’s interaction with the natural world (Peluso, 2004).

4

This point of view pushes the boundaries of anthropocentrism and cognocentrism that

are commonly held in the West. A key difference is that within this framework it is typically

accepted that “all subjects (human or not) share personhood and interact socially” (Peluso

2004, 115). Under this framework, ayahuasca is perceived as a valuable guide – teaching

people how to live harmoniously as human beings.

In addition, ayahuasca as well as other traditional medicine plants are used to treat a

variety of physical and spiritual maladies. Within this framework, disease is perceived as a

manifestation of physical, psychological or spiritual imbalance and interconnected across all

domains (Gorman, 2010). Through the use of ayahuasca, the healer is able to traverse through

metaphysical plains of consciousness to locate the cause of the illness, and cure it from the

metaphysical source (Gorman, 2010; Lamb, 1974). In cases where this is not possible through

ayahuasca alone, the healer can enter a metaphysical bank of knowledge to gain information

on other medicinal plants that can be used to treat an illness including information on

preparation and dosage.

Recent scientific research further complements the benefits of ayahuasca as described

and witnessed in Amazonian communities (DeKorne, 2011; Lamb, 1974; Plotkin, 1993;

Schultes, 2001). The majority of researchers cited here, and throughout this paper are Latin

American working in Latin American institutes. In this sense, ayahuasca is not seen through

the Western gaze, rather through researchers embedded in Latin American culture who are

weaving together modern and traditional worlds. Here, in the most beautiful way, modern

research is further bolstering the already profound and sacred knowledge held by the

indigenous people of the Amazon.

Research into the mechanisms underlying the altered states of consciousness entered in

ayahuasca ceremonies demonstrate a wide array of psychological benefits. Studies on the

5

clinical effects of ayahuasca indicate lower levels of depression (Domínguez-Clave et al.,

2016; Osório et al., 2015)– with clinical improvements still prevalent up to five years after

treatment (R. Santos, Sanches, Osorio, & Hallak, 2018), lower levels of panic and

hopelessness (R. Santos, Landeira-Fernandez, Strassman, Motta, & Cruz, 2007) as well as an

increase in the personality traits agreeableness and openness (Barbosa et al., 2016).

Ayahuasca has also demonstrated positive outcomes for drug-addiction (Argento, Capler,

Thomas, Lucas, & Tupper, 2019; Nunes et al., 2016), post-traumatic stress disorder (Labate,

2014; Nielson & Megler, 2014) and a number of eating disorders (Lafrance et al., 2017). At a

neurological level a connection between regions of the brain activated under the influence of

ayahuasca and cortical brain areas involved with episodic memory and the processing of

contextual association (de Araujo et al., 2012; Doering-Silveira et al., 2005) has been found -

as well as a connection with neural systems affecting introspection and emotional processing

(Riba et al., 2006).

In a developmental sense, ayahuasca users typically rate higher on scales of decentring

and positive self (Franquesa et al., 2018) and demonstrate a reduction in judgmental

processing of experiences and in inner reactivity (Soler et al., 2016) – ideal outcomes in

mindfulness based cognitive therapy (Bieling et al., 2012). Increased levels of mindfulness

are shown to have strong effects on cooperation – ranging from more ethical decision making

(Pless, Sabatella, & Maak, 2017), increased likelihood to uphold ethical standards (Ruedy &

Schweitzer, 2010), increased levels of altruism (Iwamoto et al., 2020) as well as a reduction

in moral disengagement and narcissism (Van Doesum et al., 2019). Here, the combination of

scientific research with more emic-based ethnographies helps paint a clearer picture of what

exactly ayahuasca is.

It is also interesting to note the relationship with ayahuasca and religion. Practices

involving a merge of indigenous methods with Catholicism or Christianity are commonly

6

found throughout the Amazon (Alverga, 1999; Richards, 2016). Linking back to cultural

evolution perspectives on religion – that being that large-scale religion came about as

societies became larger to encourage cooperation (Norenzayan et al., 2016), it then becomes

interesting to investigate the role of ayahuasca in Amazonian communities as the plant is seen

to hold a similar role of cultivating cooperation in smaller societies. Research into the

evolution of religion suggests that religion evolved from pre-existing cognitive functions

(Pyysiäinen & Hauser, 2010; Willard & Norenzayan, 2013). Given the scientific research we

now have on how entheogenic plants, such as ayahuasca, work on cognitive functions (de

Araujo et al., 2012; Riba et al., 2006; Riba et al., 2003){de Araujo, 2012 #87} it could then

be that the development processes associated with altered states of consciousness – as seen in

traditional medicines, act as pre-cursors to the development of pro-social and large-scale

religions.

The focus on divinity is present in both ayahuasca-using societies and large-scale

religions. Perhaps, then, it is the connection to something greater than the human and the

acknowledgement of a divine existence that is necessary for cooperation within societies. As

societal layouts change and evolve the medium on which this is projected onto needs to

adjust and adapt. This line of reasoning is cohesive with indigenous frameworks for health

and wellbeing such as Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie, 1994) which place spirituality as a vital

element of wellbeing.

Topic Description

Research interest

I heard about the Amazon jungle for the first time at the age of 10 and visited the jungle

for the first time in 2015 at the age of 20. It was during this time that I met the world of

medicinal plants. I deliberately did not read about other people’s experiences with ayahuasca

7

and in hindsight that enabled me to enter into this world free of expectations. During this

initial visit, I spent one month in the Amazon participating in ayahuasca ceremonies near

Iquitos, Peru. I returned to South America a few months later to spend nine months in

Colombia, Ecuador and Peru participating in ceremonies throughout these regions with

different healers and traditions – acquiring more information on the medicinal plants used, as

well as the ways in which the ceremonies were enacted. During this time, I was conversing

mainly in Spanish. In the words of Bernard (2017) I stopped being a “freak” (p. 287) and

started to speak the language of the people I was investigating – granting me access to deeper

dimensions of knowledge than what English alone offered. It was also during this time, after

spending six months living in one community, where I met one of the maestros I have

consulted with in this project.

In November 2019 I returned to the Amazon for three months. During the time I had

been away, I had begun reading ethnographies and research papers on ayahuasca. I had also

just earned my Bachelor of Science in Psychology and Anthropology. I found the

perspectives that I had learned during my education to be immensely useful. Ayahuasca

ceremonies were now an intricate web of symbols and meaning spun by the maestros of the

plant medicines. Outside of the ceremonial space, I began to read between the lines of daily

activities – seeing the connections between kinship, gender, religion and ritual enactment.

This project is based on the three months I recently spent in the Amazon from

November 2019 – March 2020. During this time, I stayed with healers in three regions of the

jungle and participated in ayahuasca ceremonies. As suggested by Naroll (1962) after the

period of one year, the anthropologist will begin to gain access to more ‘private’ and ‘taboo’

areas of the community of interest – such as witchcraft and magic, which became evident

during this trip. I have known one healer for five years, and during this trip he granted me

8

more access to the world of medicinal plants and magic than I previously believed to be

possible.

Positionality

All of the ceremonies that I participated in on this trip were with local participants. I

feel immensely grateful to be admitted into these spaces, and attribute this to the maintenance

of ongoing relationships over several years as well as being able to converse in Spanish.

However, my identity in these spaces is still one of an outsider. There is a way of

looking of life when one is embedded in Amazonian culture that I do not have. It is the

lineage of generations of knowledge about the plants and environment that, as a foreigner,

would be impossible to pick up. Furthermore, I find my journey with ayahuasca to be

difficult at points due to my different cultural background. This lies in my lack of knowledge

about local mythologies that are referenced in the ceremonies as well as the cognitive

dissonance between my more Western and logical forms of thinking to the more mystical

nature that ayahuasca embodies. Other anthropologists who have investigated ayahuasca,

such as Castaneda (1972) describe similar phenomena. I am grateful to the practitioners that I

have worked with for their patience with my Western, linear forms of thinking that are so

opposite to what is commonly held in the jungle.

Terminology

As language is one of the most basic mediums through which we construct our reality,

it is important to carefully consider the terminology being used when discussing altered states

of consciousness. Psychedelic and hallucinogenic (meaning “mind manifesting”) are words

commonly used in scientific and popular literature to describe substances that affect neural

pathways in such a way to create auditory or visual hallucinations, and that are used

sacramentally for healing or divination. Whilst popular literature authors have argued for the

9

appropriateness of these terms due to their “mind manifesting” properties (Pollan, 2018)

these notions are rooted in Western epistemological beliefs, centring on the individual and

thereby the mind as the primary locality for conscious perception and awareness.

Such viewpoints contradict indigenous notions of agency and personhood. A commonly

held belief in Indigenous communities of the Amazon is of the plants holding their own spirit

separate from the human (Gorman, 2010). It is through the consumption of ayahuasca that

one is able to interact with this spirit, and through ayahuasca that the human is able to see the

spirits of other plants of Amazonia. In this sense, the realities perceived in ayahuasca are not

manifestations of the individual, rather the perspectives of other entities beyond our everyday

realm of perception.

The paranormal effects produced by ayahuasca lie beyond what can be defined by

modern neurochemistry and commonly accepted beliefs of personhood in the West. For this

reason, the term entheogen will be used to describe consciousness-altering plants. Derived

from the Greek work enthous or enthousiasmos, entheogen means “divine indwelling” or the

“god within one” (Spess, 2000). The use of entheogen to describe psychoactive plants has

been condoned by numerous scientists, ethnobotanists and anthropologists as a more accurate

manner of describing the effects (DeKorne, 2011; Forte, 2012; T. McKenna, 1999).

Further support of divinity found in entheogens is found in the naming of mescaline-

bearing cactus Huachuma (Echinopsis pachanoi) as San Pedro by the Spanish Inquisitors.

Upon discovery of this cactus, sacramentally used by the Indigenous people of the Andes to

gain access into other realms for reasons not dissimilar to ayahuasca, the name San Pedro –

referencing the Saint who holds the keys to the kingdom of heaven was given (Glass‐Coffin,

2010).

10

The nature of psychoactive plants lies beyond the mainframes of Western ontologies,

and to truly understand their nature in an appropriate cultural context one must align with the

ontological perspectives of communities who have engrained these altered states of

consciousness into their very existence.

Ayahuasca Variations

Current literature on ayahuasca hardly distinguishes between the different types of

ayahuasca (Gorman, 2010; Lamb, 1974; Plotkin, 1993). In the words of one of the maestros;

“ayahuasca is like mangoes, there are some mangoes that are good for eating, and some that

are not”. A product of agricultural systems focused on efficiency, rather than natural

variations, our relationship to naturally occurring variations within plant species has been

severely reduced and almost forgotten (Pollan, 2002). Where, in the jungle, up to 20 different

types of platano (green banana) are readily available, in the West this is not. This restriction

of natural variation in agriculture has bled into literature on ayahuasca, with little

acknowledgement of the different variations of the vine itself.

Variations across the ayahuasca vine has recently been supported through chemical

composition analysis of ayahuasca samples collected in various Brazilian regions by Santos

and colleagues (2020) . An analysis of 176 plant lianas showed high variability in some of the

main psychoactive chemicals; harmine, harmaline and tetrahydroharmine concentrations in

the vine itself and liquid samples. Natively grown Banisteriposis caapi samples showed

significantly higher harmaline concentrations than cultivated lianas, and further variability

was shown between samples based on the region of growth.

The different types of ayahuasca are used for various reasons. From my investigation, I

have gathered that there are nine different types of ayahuasca with each healer having their

preference. Roberto uses cielo (sky) ayahuasca, as he claims this to be the most effective.

11

Distinguishable by a yellow tint on the vine, cielo ayahuasca is said to work primarily with

the celestial realms – encouraging the invitation of light energies into the body. On the other

hand ayahuasca negra (black ayahuasca) is used to work specifically with darker energies,

iillnesses with a deeper root, or black magic.

In some cases a combination of multiple vines will be used in the concoction to enable

access into multiple realms. In one ceremony, a mixture of cielo ayahuasca, boa ayahuasca,

ayahuasca negra and ayahuasca rojo was used. The ceremony lasted for several hours, and

traversed through various locations in the underworld and celestial realms. At different points

during the ceremony the maestro used specific icaros to invite in the energies of each vine.

The effects of each variation of the vine are tangible in the visions and differences are

further reflected in the nature of the icaros. For cielo ayahuasca the icaros are generally soft

in nature involving whistling and melodic humming whereas for boa ayahuasca (boa being

the type of serpent) the icaros involve hissing not dissimilar to the serpent itself. Here, the

icaros are more intense and reflective of the heavier energies that this variation of the vine is

believed to work with. As each icaro is sung, each variation of the vine was awakened in my

body. In these ceremonies, purging occurred multiple times and through each of the realms

that we travelled through.

Constructing the field

My Participants

Ayahuasca

In line with indigenous ontologies such as multi-natural perspectivism (Castro, 1998;

Peluso, 2004) – which assumes that beings human or non-human carry agency, I will be

acknowledging ayahuasca as a key contributor in this project. The phenomenological

12

viewpoints held by maestros suggest that every plant has a spirit and through ayahuasca these

spirits are able to be seen (Labate, 2014).

Roberto

Roberto is a maestro that lives in Lamas, near Tarapoto in the San Martin region of

Peru. He has been working with traditional plant medicines for over 20 years and is in his

mid-50s. He drank ayahuasca for the first-time age 28 after his compulsory military service.

Following this, he spent 5 years travelling through the Amazon drinking with 16 different

indigenous groups. A combination of the different traditions that he is trained in, his

ceremonies consist of a variety of icaros from each of his different maestros. He is Catholic

and weaves religion into his ceremonies. Each maestro practicing traditional medicine has

their particular plant that they specialise in. Roberto specialises in tabaco and is known as a

tabaquero. I spent two months with Roberto and have known him for five years.

Julio-Cesar

Julio-Cesar is a Shipibo man who lives in Paoyhan, near Pucallpa. In a similar manner

to other maestros, his face radiates youth and light. He is in his early 40s and comes from a

long lineage of traditional healers and does not follow any particular religion. He has been

serving ayahuasca for nearly 20 years and spent five years working with foreigners in retreat

centres. He emphasises that the foreigners mind is very different to the Peruvian’s and that

different ways of healing are required for foreigners. The plant he specialises in is chiric

sanango and he uses ayahuasca as a vehicle to transmute the energy of this plant. The icaros

he sings are a mixture of icaros for chiric sanango and ayahuasca.

Celinda

Celinda is a Shipibo woman who lives in the San Francisco Community near Pucallpa.

She lives with her two sons and daughter and has been practicing traditional medicine for the

13

last five years. She learned from Julio-Cesar and is in her mid 40s. Similar to other Shipibo

women, she can often be seen with a thread in her hand weaving Shipibo artesenal textiles

and patterns (see Appendix item 1). She specialises in plants specific to women.

My participants differ across ethnicity, age, religion and gender. They also differ in

how and why they use ayahuasca, their experience levels and how they construct their

ceremonial space.

The Locations

Peru was chosen due to the legality and protection of ayahuasca under Peruvian law.

Furthermore, I wanted to study ayahuasca in its home to understand not only the plant, but

it’s relation to the surrounding community and natural world. Having previously spent six

months living in Tarapoto, the capital city near Lamas, where I had met Roberto five years

ago, I am familiar with the geographical area. Paoyhan, deeper in the jungle, was

recommended to me by a friend who works with the plants. I had been told on numerous

occasions, and from my personal experience, that ayahuasca changes significantly dependent

on where it is consumed. When one goes deeper into the jungle, the deeper parts of ayahuasca

surface.

Lamas, near San Martin

Lamas is a small town in the mountainous region of San Martin, and home to multiple

indigenous groups. The area is rich in agricultural farmland – cacao, corn and coffee are just

some of the many crops grown in the area. The majority of people inhabit chakras in the

mountains, and will travel into the local market every morning to sell their products. The area

is the home of many ayahuasceros both past and present. Quechua as well as Spanish are

spoken in the area.

14

Paoyhan, near Pucallpa

A small jungle village six hours down the Ucayli river, Paoyhan is home to the Shipibo

indigenous group. The village consists of two small town squares, with houses around them.

Chakras are located down a smaller river, deeper into the jungle. Ayahuasca is grown in this

town for export into the bigger city of Pucallpa. Generations of Shipibo traditional healers

still live in this town, and ayahuasca ceremonies are held frequently. Shipibo and Spanish are

spoken here.

Methods

Participant Observation

Understanding the plant’s situatedness within a culture is just as important as the

chemical composition of the plant itself (Moerman, 2007; Reyes-García, 2010). Methods

such as participant observation have been routinely used by ethnobotanists (Plotkin, 1994)

and anthropologists (Narby, 1998) studying traditional knowledge systems in the Amazon

jungle. For this research, I primarily used participant observation form the role of the

participating observer – that being that I am an outsider in the community of interest and am

participating in life around me (Bernard, 2017). This involved actively participating in

aspects of daily life such as cultivating, Friday jungle bingo as well as ayahuasca ceremonies

preparation. Participation in both the ceremonial and non-ceremonial aspects of the

communities provided an insight into cultural norms and values as well as the situatedness of

ayahuasca in normal life and routine.

Within the realm of participant observation, my primary methodology was deep

hanging out, a term coined by Geertz (1998). Deep hanging out references an anthropological

method of investigation of deeply embedding oneself physically within a culture in an

informal sense for an extended period of time. This method is used to establish rapport with

15

the community – and is highly relevant to this project given the sensitive nature of the topics

being investigated as well as the more relaxed nature of the jungle in general.

The perspectives that deep hanging out allowed were far beyond what would have been

able with more formal and rigid methodologies. A simple hour long walk through the jungle

with a healer can reveal an encyclopaedia of information about the medicinal qualities of

multiple plants, shrubs, bushes and trees. Information such as this would be incredibly

difficult to know otherwise. Furthermore, subjecting the practitioners to a structured

interview felt culturally and hegemonically inappropriate. It feels more culturally respectful

to meet them in their familiar territory – letting them take the lead on how they would like to

share information. During these walks, I was encouraged to take notes and photographs of all

the plants we encountered. My journal was filled with recipes, complementary plants and

uses. This method of ‘jungle-walks’ has been a common form of learning among

ethnobiologists (Plotkin, 1993; Schultes, 1980, 2001) in the Amazon.

Semi-structured Interviews

With each healer, I conducted a semi-structured interview focusing on their journey

with ayahuasca. This began with the question of “how did you become a maestro”? This was

the only consistent prompt that I used, and based off their responses I would prompt more

when appropriate. The responses I got took me told me tales of life in the Amazon decades

ago and helped me understand the historical context of Peru. Each narrative was a journey

through time and space, and often involved the maestros first seeking healing themselves.

Some learned from a collective of indigenous groups, whereas others only had one maestro

that they learnt from. Each initiation process took place over the period of many years, a strict

diet and periods of solitude.

16

I kept semi-structured interview usage to a minimum, leaning more on deep hanging

out perspectives and topics that arose naturally in conversation. My reasons behind doing this

were to allow the participants to reveal what they wanted to reveal, when they wanted to

reveal these. Once again, this felt more culturally and hegemonically appropriate.

Ethnomethodology

In terms of understanding the ritual itself I used ethnomethodology (Coulon, 1995) –

shifting my gaze to the physical construction of the space and the elements present as the

primary form of communicating the essential parts of the ritual. This involved focusing on

the elements present in the ceremony; such as tobacco, agua de florida and ritual attire. By

breaking the ceremony down into building blocks, I was able to understand the vital elements

necessary for the ritual to be enacted. This lead me to prompt the maestros on the function of

each element in the ceremony. Furthermore, through viewing ceremonies across a variety of

traditions, I was able to gain a better understanding of what elements are necessary at the core

of an ayahuasca ceremony and which are the maestros personal style. My intention behind

taking this perspective was to use ritual as another entry-point for understanding the role of

ayahuasca Peruvian Amazonia.

Given the transformational nature of ayahuasca, I focused on more auto-ethnographic

methods to transmit the sensory and embodied experience of traditional plant medicines and

the jungle (Barter, 2012; Ellis, 2004). This focuses on my own experience, situating myself as

the active participant in this ritual. By tapping into the sensory construction of the space –

such as the smells, the internal feelings both physical and emotional, and sounds of the jungle

environment I hope to accurately convey as much as possible in my writings of my

experiences in the jungle.

17

In this report, I have combined my auto-ethnographic experiences with my fieldnotes in

the form of vignettes in order to demonstrate the more sensory, self-as-a-subject, nature of

ayahuasca. In each ceremony, I was opened up to the cosmical realm of ayahuasca and to

attempt to create some sort of objective reality out of these experiences seems moot. I have

also used auto-ethnography to display explicit transparency about my personal biases and

beliefs, which no doubt effect my interpretation of the ceremonial setting, let alone my

interpretation of ayahuasca.

Fieldnotes

During my time in the jungle, I kept a detailed personal journey; separate from my

fieldnotes (which articulated more ‘objective’ reality). In this journal, I wrote my feelings,

thoughts and internal processes – and how they interplayed with the ceremonies or the world

around me. I noted my internal processes with how ayahuasca was working in my body. With

ayahusaca, and many plants of the Amazon, it is common for the effects to continue for many

days and weeks following a ceremony. Furthermore, if one is to enter into a dieta (strict

intake of certain foods with regular ingestion of ayahuasca or other plants) the plant itself

begins working strongly through the body of the person. Here, the effects of the plant can be

strongly felt long past the termination of a ceremony.

I also included observations about societal structure and cultural norms in my field

notes whenever something particularly salient emerged. There were times when I was

exposed to rites of passage (such as a hair cutting ritual in a small jungle town high in the

mountains), religious rites and funeral rites. I kept detailed notes on the construction of such

spaces - adopting more ethnomethodology perspectives, in order to better-understand the

cultural as a whole.

18

On days that there were ceremonies, I would aim to document my experiences the

following morning - aware that memory of such states so far away from ordinary reality fade

rather quickly. However, this was not always possible so some ceremonies would go until 5

or 6 a.m. or I would be energetically tired after a full night of exploring the ethereal realms.

In these cases, I allowed myself to rest, and it seemed as though the plant was still working

quite strongly in my body and had not finished yet.

It was often difficult to write the experiences of the ceremonies due to their non-linear

nature so I used voice recordings on my phone for my notes. This enabled me to attempt to

describe metaphysical experience in much more detail and with more flexibility than written

form would have allowed. To translate the absolute beauty that I was experiencing into words

seemed near impossible, so I began painting (see Appendix item 2). I would spend a few

hours a day after a ceremony painting a detail of what I had seen the night before. I also drew

some of the patterns I was seeing.

Translating the entheogenic into the mundane

Upon my return, I began using extensive memory work (Bernard, 2017). This involved

actively constructing my workspace to mimic the jungle as much as I could. To do so, I

listened to recordings of the icaros from the ceremonies. I also used smells such as agua de

florida my paintings as reference points. Of course, memory changes over time but the

paintings took me back to the particular moment in the ceremony where that experience was

happening. I could recall what I was feeling and the message behind that particular image.

I followed a similar methodology outlined by Bache for translating the entheogenic

experience. Bache (2019) reflects on how the entheogenic experience can be particularly

fleeting – given that it is so far away from what we normally experience, yet it is so important

to translate back as it is through these translations that we can begin to document the ethereal

19

plane. His method involves listening to the music of the experience over and over again and

using the music as a method of transporting oneself back into the cognitive state when the

entheogenic experience was happening. To successfully translate the experience, Basche

suggests listening to the particular music repeatedly until the entire experience that was

happening during that particular music is extracted from the subconscious. Here, the

recordings of the ceremonies were immensely useful. When writing this piece or reading

through my fieldnotes I would put the icaros in the background.

I combined this with a sense of smell, using agua de florida which immediately

transported me back to the ceremonial space. Smells carry a great deal of memory with them,

and this allowed me to enter into the general ceremonial space whereas the icaros themselves

allowed me to tap into the more nuanced details of the ceremonies that I had recorded.

Ethics

“Trust builds relationships. Relationships drive action. Action creates change. This

means change moves at the speed of trust” (North Star, 2020)

The ethics guiding this project are the North Star Ethics Pledge (North Star, 2020).

Developed through consultation with over a hundred key stakeholders, including indigenous

groups and other experts in the field of psychedelics, this pledge provides a framework for

individuals and organisations working in the field of entheogens. There are seven guiding

principles: Start Within, Study the Traditions, Build Trust, Consider the Gravity, Focus on

Process, Create Equality and Justice, Pay it Forward.

The pledge encourages investigators in the field to actively consider their own

positionality and take responsibility towards the biases they hold, whilst respecting and

upholding the voices and perspectives of indigenous people on entheogens. Examples of

action points that are relevant to this project are: “Study the history of indigenous use of

20

psychedelics, and listen to the perspectives of indigenous peoples on psychedelic use today”

(North Star, 2020) and “take steps to ensure I understand and engage with the people

impacted by work, to be sure I know their perspectives, keep those channels of

communication open where possible” (North Star, 2020).

The North Star Ethics pledge mirrors principles found in Kaupapa Māori research

frameworks, encouraging relationships built on partnership, participation and protection

(Bishop, 1999). The positive impact of ongoing relationships was highly evident during this

fieldwork. Given the sensitivity of indigenous communities due to the ongoing effects of

colonisation on traditional medicine practices - it is vital that a strict ethical guideline is

adhered to, to ensure that harmful, Western-centric research methods do not add further

damage to indigenous communities in any way, shape or form.

Methods in practice: A process of initiation

“As he crosses threshold after threshold, conquering dragon after dragon, the stature

of the divinity that he summons to his highest wish increases, until it subsumes the

cosmos. Finally, the mind breaks the bounding sphere of the cosmos to a realization

transcending all experiences of form - all symbolizations, all divinities: a realization of

the ineluctable void.” – Campbell (2008)

The Hero’s Journey (Campbell, 1941) has its origins in Jungian frameworks and

parallels rites of passage (Van Gennep, 1909) in anthropology. The Hero, as articulated by

Jung (2009), is an archetype that each human will embody at some point, if not many times,

during their life. Successful completion of the journey requires accepting the call to adventure

(departure), traversing through the mystical forest (state of liminality) and lastly, returning

back to the initial society to share and integrate the lessons that they have learned (Campbell,

2008).

21

During the stage of liminality the Hero is required to enter into the mystical forest alone

where they are forced to face fae and foe. To leave the forest the Hero is required to slay

multiple demons representing darker elements of the subconscious. Mystical guides appear at

multiple times during the journey, providing the Hero with superhuman strength to complete

their mission. For success, the Hero is required to reach a place of harmony with the

subconscious and conscious elements of the self and their natural environment.

The Hero’s journey parallels the rite of passage for becoming a maestro or

ayahuascero in Amazonian shamanism. I find this metaphor particularly useful to use for

both its digestibility as well as the acknowledgment of the influence of external agents in this

rite of passage. The mystical assistants in this contexts are the plants themselves – assisting

the initiate in their journey to merge the conscious with the subconscious. Furthermore,

Campbell’s depiction of the Hero parallels the process of using ayahuasca to cleanse and

cure. We see this through the Hero slaying the demons, just as the maestro removes stagnant

energies through their work.

I talked to the maestros about their experiences of initiation. Often, the maestros first

sought ayahuasca to heal themselves. After a period of months or years, they were eventually

called back to the plant and either learned from one maestro or multiple groups.

The maestros dieted, on average, for a period of five years. A diet or dieta refers to an

extended period of time where the individual will frequently ingest a plant and adhere to the

specific diet required by that plant to facilitate a greater connection to the plants and the spirit

realm (Luna, 2011). For ayahuasca this involves no sugar, no salt, no fat and no sex.

Roberto

Roberto drank ayahuasca for the first time at the age of 28 following his military

assignment. He then returned to drink ayahuasca a year later, and continued his journey to

22

learn from 16 different maestros in the Amazon including the Kanixawa, Shipibo and

Ashaninka. He became familiar with the way of the life in the jungle, living on a diet of

plantains and rice. Having acquired a multitude of icaros from the his teachers he then sat

alone with ayahuasca for some more months. He asked ayahuasca which icaros he should

keep, and which ones he should forget. During this period, he also acquired other icaros from

ayahuasca directly.

Julio-Cesar

Julio-Cesar first drank ayahuasca to cure himself. Coming from a long line of

traditional Shipibo healers, Julio continued the tradition spending many years dieting various

plants with his elders. He still continues to spend months in solitude in his centre during the

wet season when his centre is inaccessible to foreigners. He was just about to begin a 40 day

diet with chiric sanango when I was leaving.

Students

I met some of Roberto’s students and had conversations with them regarding their

experiences of learning the plants. None of them had spent 4-5 years solely with the plants.

Rather, they would juggle work/study commitments by spending a few months on Roberto’s

charka, and return back to their normal lives highlighting the influence of modernisation in

the Amazon. On the chakra they would learn the icaros and frequently participate in

ayahuasca ceremonies. They continued to visit and participate in Roberto’s ceremonies

outside of the dieta.

My experience

Upon my most recent return to Peru, the plant spoke to me in a completely novel way

and I, too, had changed the way I approached ayahuasca. Instead of saying I want to learn

(apprendre) about ayahuasca, I phrased my wording to simply know (conocer) ayahuasca. By

23

this point I had drunk ayahuasca somewhere between 30-40 times (at least 20 of them were

with Roberto).

Sitting in my usual meditative position a wave of energy enters my periphery targeting

the centre of my forehead. The icaros are soft in the background, coaxing the plant to work

in our bodies. A blinding white light appears. It feels like someone is holding a hot candle to

my forehead. My energetic field clears and I’m suddenly on the top of a mountain. From this

perspective, I see how to set intention, how to be clear, how to see without failure. I see a

multitude of feathers and colours burst from my forehead. The plant was inviting me to learn

her.

I asked Roberto about my visions the following day. He said that women do not

practice the medicine, rather they specialise in other herbs for more physical illnesses. This

isn’t the case in more matriarchal Amazonian communities, such as the Shipibo where the

abuelita’s frequently hold the positions of ayahuascera and maestra (Heise & Pino, 1996;

Roe, 1982). Regardless, he was happy to teach me and had seen the visions as well.

According to him learning the plants requires dominating them – meaning that instead of

letting the plant control you, you need to learn how to guide the plant. In order to achieve this

he said he needs a minimum of five months. I explained to him my time restraints, and he

suggested living on the chakra during my stay here to learn what I could.

My first step would be to dominate tobacco as it is through tobacco that one cures and

receives icaros. He gave me one of his maestro’s pipes to use and prescribed me to smoking

the pipe every night and in ceremonies. He also encouraged me to spend time drinking alone

with ayahuasca.

From this moment, my position with ayahuasca changed. It became increasingly emic,

as I was now operating from within the domain of the plant herself. I was no longer there to

24

simply observe the plant and ceremonial construction, but to truly understand the

mechanisms of ayahuasca and how the plant itself sees the world. Although I was a woman in

a very male-dominated space my gender did not influence how people treated my capabilities

and this was further supported through Roberto’s guidance and approval. I felt protected

under his wing. It is very important to note that my position of this is very novice, and in no

way compared to the wealth of knowledge that maestros such as Roberto and Julio-Cesar

possess.

When I first drank ayahuasca in 2015, I was shown metaphysical locations beyond my

perception. In one vision I saw pyramids around which beings with oval heads were dancing.

In the same ceremony, I saw a group of indigenous people with masks guarding a gate to

which I was admitted. At this moment, I knew there was something special about the plant

and our connection. Being a complete novice in both the cultural and ethnobotanical realms, I

continued following ayahuasca around South America to understand what this mundo magico

(magical world) was about.

One of Roberto’s students asked me if I had ever seen the pyramids in my ceremony. I

shared with him my vision, and he too had seen the visions of the pyramids. He had tried to

climb them, but they collapsed. Roberto interpreted this as him not having reached the stage

of maestro yet and one has reached this stage they are granted access into the pyramid.

Campbell (2009) speculates on possible precursors for future initiates – whether this is

heightened sensitivity, certain childhood events or perhaps in the case of ayahuasca seeing

certain symbols in early visions.

Roberto’s chakra

I spent just over two months with Roberto participating in ceremonies. In each

ceremony, I grew closer to tobacco – smoking the pipe entrusted to me. He encouraged me to

25

keep developing my relationship with the plant, to diet strictly and smoke my pipe. After

some time, Roberto entrusted me with pouring my own ayahuasca. Later, he assigned me to

interpret the visions of other participants in the ceremonies. We would frequently discuss the

plants and jungle mythology both within and outside ceremonies. Roberto frequently parted

knowledge on the mechanisms through which he was curing his patients. In one preparation

session, Roberto shared that he was grateful for foreigners who come here to learn the plants

as the knowledge is being lost with many young people moving to the bigger cities to work.

Roberto and the other maestros, as well as ayahuasca herself, were supportive of my

research.

As my diet continued, I began drinking less ayahuasca with stronger effects. Ayahuasca

started showing me how illness is viewed through the eyes of the plant, as well as other plants

in the jungle that I would meet later on. Tobacco enabled me to direct the energy of

ayahuasca. I could tell her where to go and what to work on. As I filled my lungs with the

cold smoke of tobacco, my visions would change. At one point, I saw the spirit of tobacco

himself as giant fortress of stability, protection and security – towering high above the

cosmos. It can take from four months to a year to dominate tobacco.

Ceremonies were held every Tuesday and Friday. The ceremonies often consisted of 3-

8 Peruvian participants, either frequent or new drinkers. Some participants would only be

there for one ceremony, whereas others would partake in a dieta for a period of weeks or

months. Roberto’s students sometimes came to the ceremonies. During my time there, two of

his students came to stay for a few weeks on the chakra.

One evening Roberto held a ceremony with Don Eihidio and myself. Don Eihidio has

been one of his students for a number of years and visits when possible to continue his

training.

26

I could feel the maraecion coming as colours skirted around the peripheries of my

vision. In an instant, I was transported inside a maloca. The maloca was beautifully carved

with dark wood in an octagonal shape. Outside, the tress brushed against the wall. It was

night. This location felt incredibly familiar.

There were three people in the maloca with me. I looked down at my body and I was

draped in the most glorious robes (similar pattern to the cover page). In the centre of the

maloca lay the most beautiful emerald. Glowing dark green, the emerald emanated an

energy stronger than anything I had perceived before. As I focused on the emerald, I began

to see the pure enormity of ayahuasca, knowing very well that I had only seen the smallest

glimpse. An entity, a spirit, more omnipotent than anything I could have perceived in my

rational mind.

The maloca described above is a common location in the ayahuasca landscape. Roberto

called this location the centre of the jungle. Here, all the information of the jungle and plants

are stored, as well as the heart of ayahuasca.

Finding la plantita

In similar footsteps to the other maestros I began to find my special plant. I heard about

the plant huambisa biajo from a dear friend living in the Amazon who has spent multiple

years dieting a range of plants. The plant is for visions, creativity and more specifically;

painting.

Since I heard of huambisa biajo (or as I preferred to call her; la plantita meaning the

little plant) I began to come across the plant in my daily life. My friend had shown me a

photo of a plant with pink veins, and the next day the plant was in a cafe I went to. With

ayahuasca, as the other plants, it is a commonly held belief that it is the plant that calls you

and not the other way around. This was confirmed during my earlier ceremonies. At around

27

the 20th ceremony, ayahuasca showed me how it was not me who sought the plant, rather her

that called. I was simply following a trail of breadcrumbs thinking it was my own.

Paulo, a friend of mine living in the main city, Tarapoto, assisted me in finding the

plant. Through some miracle we came across a mother plant in a local greenhouse. Given that

this plant is not usually found in the highland regions of the jungle, I knew the plant was

calling. I took the plant to Roberto and we decided to prepare it for the ceremony that

evening.

From what I had been told the vapor of the plant needs to be inhaled. Following

Roberto’s directions, I proceeded to pluck seven leaves off the plant (it was important that no

one else touched the plant) and boiled the leaves in a kettle over the fire. As I inhaled the

vapour, my body became more energetically charged but my vision did not change.

According to Roberto, every plant has a spirit but it is through drinking ayahuasca that we are

able to actually see the spirit of the plant. We were also uncertain on the proper name of the

plant so Roberto said that he would ask ayahuasca that night.

Within ten minutes the visions of the plant came. Beautiful leaves filled my visions with

colours and patterns that I had never seen before. The visions were beyond this plane, 3D

and all encompassing. When I felt the energy of the plant I had an explosion of love in my

heart, beyond anything I had previously experienced. The energy was different to

ayahuasca’s. It was much younger and playful. I began to understand how my entire journey

with the plants had lead me to this one, very specific moment. A woman’s face made out of

leaves appeared. The spirit of the plant. I had found my plant.

Roberto had asked ayahuasca about the plant and received the name huambisa biajo.

Ayahuasca also said to prepare la plantita using dried instead of fresh leaves, and that the

plant can be mixed with ayahuasca when cooking. Halfway through the ceremony, Roberto

28

asked me if I had seen the plant. He is able to see into everyone’s visions, and as he asked

was the peak of the plant’s energy of my body. He, too, could see the energy of the plant

however he did not consume the plant himself. The following day I reheated the plant

mixture and inhaled the vapor again to keep the energy in my body. We discussed the plant

and he had also seen the spirit of the plant as a woman with flowing hair. Shared visions are

commonly documented in ayahuasca ethnographies (Lamb, 1974), which brings to question

the nature of our subjective experiences both in ethereal planes and otherwise. We built a

small home for the plant and planted her in the chakra (see Appendix item 3).

Mechanisms of healing

As the connection between Roberto, ayahuasca and myself grew, Roberto and I began

to communicate without words in ceremonies. He would sit in the corner, and I would sit on

his left hand side in every ceremony. When he wanted to show me something, I would hear

his voice although he was not physically speaking.

As he cured patients I would hear the words ‘voy a curar’ (I am going to heal) in my

mind. My attention would be drawn towards his actions and how he was doing this – often

through blowing heavy energies off the bodies of the participants. This would sometimes

happen over many metres. I came to understand that cleaning energy is one of the major

methods of healing with ayahuasca. This was further reinforced through an interview with

Celinda, a Shipibo healer.

Me: So, tell me, how do you cure the patients that come to you?

C: I look at the body of the person. When they first come in their body is dark and

heavy. If they are using marijuana and other drugs it is darker. When I work, I clean the

energy field of the participant until it starts to glow white. The body should show the

29

drawings of the Shipibo. This can take multiple sessions. When their body shows this

pattern, they are ready to leave.

Another crucial element of the ayahuasca ceremony is the purge, or the participant

physically extinguishing stagnant energies in the body. The importance of this is reflected in

the icaros. The icaros act as a form of mystification in themselves, fostering a connection

between the ethereal and mundane. Operating from both these leaves, the icaros frequently

encourage the plant to limpiar (clean) and purgar (purge).

Ayahuasca also showed me how she views illness in the body. The journey itself

required a great deal of concentration, and I honed my energy into particular threads of

energy in the body. Following each thread, I eventually landed at the root of the illness to be

cleaned. Here, I drew parallels between what I was seeing and how Celinda described her

work. It was important to maintain a state of non-reactivity because the place I was seeing

was filled with darkness and grime.

Energetic Transmission

Roberto often entered into my visions in ceremonies with him, alone and with other

maestros. He provided me with guidance and protection and I was able to communicate with

him in the world of ayahuasca. In the ceremonies with him, he was able to see all of my

visions, and would blow away negative energies.

Dark thoughts started entering my head. I felt weak and uncertain about my

environment and path. I was sitting on the left hand side of Roberto, directly in front of his

gaze. As these thoughts entered my mind, he blew energy from where he was sitting towards

my forehead. As he did this, my visions of my thoughts shattered into glass fragments and out

of my range of perception.

30

In ceremonies with other maestros, Roberto would frequently appear in my visions.

When difficulties arose, I was able to reach out to him and he would often guide me to smoke

my tobacco for strength and protection. As I dieted for longer and grew closer to ayahuasca

my connection to Roberto became stronger, and I began to see the nature of this relationship

outside of the time space continuum. It is also important to note that as my diet continued, I

would frequently depart from space-time restrictions and into an existence outside of these

variables.

My awareness of myself and the room slipped away. All that was left was what can only

be described as pure, energetic consciousness and my perception filled with bright yellows

and purples. I began to travel into the very essence of existence, traversing through timelines

of geographic development. After reaching what seemed to be pure nothingness, I started

moving forward. I entered into an experience of a paleozoic swamp. I experienced the

human’s first interaction with water. Surrounding me were ancient organisms in their most

primal form. I awoke in a small hammock on a wooden boat. As I rose, I saw a young

Roberto standing in front of me. He pulled a mapacho (rolled tobacco) from his shirt pocket

and gave it to me. Here, the human met tobacco.

A painting by visionary artist Ben Lopez depicts a strikingly similar scene (see

Appendix item 4). The following morning Julio-Cesar asked me about the maestro I was

staying with before, having seen his energy the previous night in the ceremony. He said that

he had good energy and was interested in drinking with him.

Down a similar vein, the maestros are able to see the level of experience held by each

participant through ayahuasca. Each maestro that I visited encouraged me to spend time with

the plants, smoke my tobacco and that it was important for me to learn. I did not share with

them that this had already been granted by ayahuasca. At many stages the maestros

31

performed various initiation rites. During these processes, they would sit in front of me in the

ceremony and blow their tobacco whilst chanting icaros directly at me. Sometimes, they

would encourage me to follow the harmony of their icaros. The maestros would call in the

spirits of the jungle to help me learn, and would finish with a sopla (tobacco blowing) on my

forehead often whispering small chants or incantations into my crown. This sparked a train of

thought into how the transmission of knowledge works in ayahuasca settings. What role do

the plants play in the initiation process?

Analysis

“Cada dia es un dia mas de experiencia” – Roberto

Everyday is one more day of experience

Traditional knowledge systems

Traditional knowledge systems [TKS] investigate the transmission of knowledge where

plant medicines are frequently involved (Berkes, Colding, & Folke, 2000; Posey, 2002;

Reyes-García et al., 2009). Transmission of knowledge is theorized to be through vertical

(parents to offspring), horizontal (between two individuals of the same generation) and

oblique (non-parental individuals of parental generations to other members of filial

generation) pathways (Cavalli-Sforza, 1981). The oblique pathway can be from one-to-many,

when one person (e.g. a professor) will transmit knowledge to a younger group or many-to-

one when a younger person will learn from multiple adults other than the parents (Cavalli-

Sforza, 1981).

32

Ethnographic research with the Tismane of the Amazon Basin indicates different

pathways through which information about plant medicines is transmitted based on the type

of knowledge (Reyes-García et al., 2009). Whilst general knowledge may be passed down

through more vertical pathways and acquired through childhood, specific knowledge of

plants requires more direct involvement and investment from the learner. Due to the specialty

of such knowledge, the learner may choose to learn from more experienced and older persons

and therefore more inclined to use vertical and oblique pathways (Reyes-García, 2010;

Reyes-García et al., 2009).

What I found was that in this particular case specialized knowledge pertaining to

ayahuasca is transmitted through oblique pathways from the maestro to student. This is done

predominantly through experiential and observational forms of learning. The apprentice

spends an extended period of time alongside the teacher, observing their methods and

practicing the tasks as well. The rite of initiation with ayahuasca requires the apprentice to

participate frequently in ceremonies, as the plants themselves are believed to hold a crucial

role as teachers. For the process of ayahuasca initiation, knowledge is transferred from both

the human-teacher as well as the plant. Although TKS provides an insight into how the

information is transmitted from human to human, this system adheres to Western notions of

personhood and agency which is commonly not applicable in indigenous settings (Peluso,

2004).

Perspectivism

Multi-natural perspectivism provides a poly-local perspective on consciousness and

intention, focusing on notions of personhood and agency (Castro, 1998). Within this

framework, the human, animal, plant and spirit each hold a unique perspective and thereby

insight into the natural world of equal validity.

33

Personhood within this sense is defined by self-consciousness, multiplicity and

transformability (Peluso, 2004), paralleling typically accepted notions of personhood of

humans in the West. However, a key difference is that “all subjects (human or not) share

personhood and interact socially” (Peluso 2004, 115) and that non-human agents are

“manifestations of normally invisible anthromorphic beings” (Peluso 2004, 115). Natural

realities and metaphysical realities weave together seamlessly. Altered states of

consciousness, either through dreaming (States, 2003) or entheogenic experiences (Labate &

Jungaberle, 2011) are perceived as ‘real’ as everyday waking reality.

Multi-natural perspectivism pushes beyond anthropocentrism and cognocentrism,

acknowledging the perspective of each agent and state as equally valid and informative

thereby expanding on the human’s interrelationship with their internal states and the natural

world.

During my time with Roberto, he was predominantly facilitating my relationship with

ayahuasca and showing me how he constructs the ceremonial space and heals. My

relationship with ayahuasca was of great importance to him and he frequently encouraged me

to speak to the plants directly. I could ask the plants for anything I needed to help with this

process such as the icaros. He was pleased to hear my reports on my progressing relationship

with them and my developing connection manifested in the ceremony through me being able

to hear high pitched metallic frequencies, said to be the music of the plants.

The icaros started to come in my ceremonies alone. My icaros began to come, firstly as

the whistle melody and then as humming – I did not get further than that on this trip. I would

practice the icaros with the plant, directly seeing how the icaros encourage the plant to work.

As I would whistle, my visions would expand. It was also here where I would learn the most

about how ayahuasca works. The plant would show me how exactly she knows her

34

knowledge, how energies work and how the plant kingdom operates. During these

ceremonies, a black bird flew over my head each time. Roberto said that this happens when

you drink alone – it is the spirit of the jungle talking to you.

Earlier on, one of Roberto’s students who is a tabaquero told me to smoke my tobacco

slowly, and to feel the energy in my body. When I need to smoke in ceremonies, ayahuasca

will tell me. In my ceremonies alone there would be points where I would see a flame or pipe

appear in my vision. I took this as my cue to smoke my pipe. Whether this was ayahuasca

communicating with me or tobacco using the visual vehicle of ayahuasca to communicate is

ambiguous. Either way, both tobacco and ayahuasca were vital guides and teachers in this

process and actively participated as agents in their own form.

In my other visions I saw how illness is seen through the eyes of the plant. At many

times during the ceremonies (both alone and in a group), I would feel bolts of energy shoot

through my body, in particular through the middle of my forehead. This felt like information

being transmitted from the plant directly into my system. Ayahuasca also acted as a conduit

for communication between Roberto and I enabling us to communicate without words, and

here he was able to show me how he was healing. My senses were hyper-vigilant in the

ceremonies, and the knowledge transmission that occurred during those ceremonies is beyond

what the physical reality can comprehend. We communicated without words frequently. I

noticed the ongoing effects through slight changes in my cognition and behaviour in the

ceremonies during my time there, with each ceremony building on the last. I was soon

adopting the methods of healing that Roberto and his students were using through the

transmission of knowledge happening on a metaphysical plane in the ceremonies.

It is also important to note that the type of ayahuasca is a crucial, yet frequently missed,

factor to consider as this not only effects the visions themselves but the type of knowledge

35

being received in the ceremonies. The maestros each learned using the different variations of

the vine. The specificities of each type of liana was most obvious in an ayahuasca mixture of

four vines. As we traversed through the different realms, my visions would change in

intensity and colour – with boa and ayahuasca negro working in the underworld. When

traversing through the celestial realms that cielo ayahuasca enabled, my visions were filled

with light. Here, I learned the composition and characteristics of each realm and in each

realm, there was different purge.

Perhaps the most salient theme during this time was the focus on human development.

In many of my ceremonies ayahuasca taught me characteristics of love, trust, respect and

humility. Roberto would often appear in these visions, showing me how to stay focused,

showing me how to work with respect and showing me how to have honour for oneself and

the jungle. I would feel certain energies throughout my body, and perhaps the only way this

could be described is of ayahuasca subtly realigning my energetic body. My visions would

show me scenes of great love and peace, hard-work and focus and clear energetic threads of

focused intention emanating from my body. Sometimes these visions were not of me, which

did not matter - I was learning from the whole human experience. Each purge was removing

aspects of myself that did not align with these core values and became deeper and more

physical the longer I stayed. Anthropologist Richard Katz (1997) describes his time in Fiji

where he learned the traditional medicine practices over a period of two years with a local

healer. Katz (1997) describes the “straight path” as the most emphasized teaching from his

teacher. To stay on the straight path is the responsibility of the healer, and it is to remain

focused and clean in one’s energy by staying close to the plants.

Often when asked about how ayahuasca was discovered, maestros will say that it was

the plants that showed them (Beyer, 2009). With over 80,000 plants in the Amazon jungle,

the combination of one particular vine with one specific leaf in a certain ratio and cooked in a

36

specified manner seems highly unlikely to be stumbled upon by chance alone. Learning

trajectories in Amazonian shamanism support notions of multi-natural perspectivism

attributing agency and personhood to the plants themselves, as the plants hold a vital role in

the transmission of knowledge.

Young ayahuasca apprentices are often required to live alone in the jungle under the

supervision of a maestro or ayahuascero, ingesting large quantities of plants over several

years. Here, the plant helps them to penetrate the barrier of the physical world (Narby, 1998).

Initiation in African-Darga communities involves many elders of the community supervising

the potential healers. The initiates are required to ingest certain plants frequently to connect

with ancestor spirits (Some, 1995). In Fiji, an apprentice is required to frequently consume

yaqona or kava with an experienced healer. Ingestion of the plant is believed to facilitate

connection with the spirit realm (Katz, 1999). The consumption of plants to facilitate a deeper

connection with the spiritual world - where information on healing is stored, is a common

thread across these scenarios suggesting that the plants play a crucial role in the learning

process.

To return to the Hero’s journey, whilst the assistants in the journey may typically be

viewed as human counterparts, the constant presence of plants in rites of initiation coupled

with indigenous notions of personhood and agency suggest that the assistants in the journey

may also be the plants themselves. As the Tukano creation myth suggests, ayahuasca was

given to teach people how to live and to speak, and to facilitate a connection with the spirit

world where important information on the nature of their existence could be accessed.

Ultimately, ayahuasca – the mother of the jungle, shows us how nature is both teacher and

guide. The integration of these perspectives with the human being can greatly assist us in our

combined evolutionary trajectory with the natural world and our human responsibility to step

into our role as protectors of nature and custodians of this knowledge.

37

Conclusion

Often when asked about how ayahuasca was discovered, maestros will say that it was

the plants that showed them (Beyer, 2009). With over 80,000 plants in the Amazon jungle,

the combination of one particular vine with one specific leaf in a certain ratio and cooked in a

specified manner seems highly unlikely to be stumbled upon by chance alone. Learning

trajectories in Amazonian shamanism support notions of multi-natural perspectivism

attributing agency and personhood to the plants themselves, as the plants hold a vital role in

the transmission of knowledge.

Young ayahuasca apprentices are often required to live alone in the jungle under the

supervision of a maestro or ayahuascero, ingesting large quantities of plants over several

years. Here, the plant helps them to penetrate the barrier of the physical world (Narby, 1998).

Initiation in African-Darga communities involves many elders of the community supervising

the potential healers. The initiates are required to ingest certain plants frequently to connect

with ancestor spirits (Some, 1995). In Fiji, an apprentice is required to frequently consume

yaqona or kava with an experienced healer. Ingestion of the plant is believed to facilitate

connection with the spirit realm (Katz, 1999). The consumption of plants to facilitate a deeper

connection with the spiritual world - where information on healing is stored, is a common

thread across these scenarios suggesting that the plants play a crucial role in the learning

process.

To return to the Hero’s journey, whilst the assistants in the journey may typically be

viewed as human counterparts, the constant presence of plants in rites of initiation coupled

with indigenous notions of personhood and agency suggest that the assistants in the journey

may also be the plants themselves. As the Tukano creation myth suggests, ayahuasca was

given to teach people how to live and to speak, and to facilitate a connection with the spirit

world where important information on the nature of their existence could be accessed.

38

Ultimately, ayahuasca – the mother of the jungle, shows us how nature is both teacher and

guide. The integration of these perspectives with the human being can greatly assist us in our

combined evolutionary trajectory with the natural world and our human responsibility to step

into our role as protectors of nature and custodians of this knowledge.

39

Bibliography

Alverga, A. P. d. (1999). Forest of visions : Ayahuasca, Amazonian spirituality, and the Santo Daime tradition. Rochester, Vt: Park Street Press.

Argento, E., Capler, R., Thomas, G., Lucas, P., & Tupper, K. W. (2019). Exploring ayahuasca-assisted therapy for addiction: A qualitative analysis of preliminary findings among an Indigenous community in Canada. Drug and alcohol review, 38(7), 781. doi:10.1111/dar.12985

Bache, C. (2019). LSD and the Mind of the Universe: Diamonds from Heaven: Inner Traditions/Bear.

Barbosa, P. C. R., Strassman, R. J., Da Silveira, D. X., Areco, K., Hoy, R., Pommy, J., . . . Bogenschutz, M. (2016). Psychological and neuropsychological assessment of regularhoasca users. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 71, 95-105. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.09.003

Barter, N. (2012). The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal: Indigenous Peoples: Accounting and Accountability, 32(2), 121-123. doi:10.1080/0969160X.2012.718920

Berkes, F., Colding, J., & Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1251-1262. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2

Bernard, H. R. (2017). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Beyer, S. (2009). Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon: University of New Mexico Press.

Bieling, P. J., Hawley, L. L., Bloch, R. T., Corcoran, K. M., Levitan, R. D., Young, L. T., . . . Segal, Z. V. (2012). Treatment-specific changes in decentering following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus antidepressant medication or placebo for prevention of depressive relapse. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 80(3), 365-372. doi:10.1037/a0027483

Bishop, R. (1999). Kaupapa Maori Research: An indigenous approach to creating knowledge.Campbell, J. (1941). The hero with a thousand faces (1st ed.). Novato, Calif: New World

Library.Castaneda, C. (1972). Journey to Ixtlan: the lessons of Don Juan. New York: Pocket Books.Castro, E. V. D. (1998). Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism. The Journal of

the Royal Anthropological Institute, 4(3), 469. doi:10.2307/3034157Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. (1981). Cultural transmission and evolution : a quantitative approach.

Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.Coulon, A. (1995). Ethnomethodology. doi:10.4135/9781412984126de Araujo, D. B., Ribeiro, S., Cecchi, G. A., Carvalho, F. M., Sanchez, T. A., Pinto, J. P., . . .

Santos, A. C. (2012). Seeing with the eyes shut: Neural basis of enhanced imagery following ayahuasca ingestion. Human Brain Mapping, 33(11), 2550-2560. doi:10.1002/hbm.21381

40

DeKorne, J. (2011). Psychedelic Shamanism: The Cultivation, Preparation, and Shamanic Use of Psychotropic Plants: North Atlantic Books.