Investment in Education in India

Transcript of Investment in Education in India

eastern ECONOMIST

%

%

I n v e s t m e n t in e d u c a t io n a s a n i n d u s t r yJandhyala B. G. Tjlak

r

Bscending up the eighties

lovestment in education as an industryJandhyala B. 6. Tilak

The recognition to Education as an industry was granted •mly a few years back. The problem o f investm ent in this industry is o f a peculiar nature. The author has made an m em pt to analyse the several problems relating to investment in education in India in particular and in the growing economies in general. He attempts to ascertain the relative importance o f diffdrent sources o f investment in education in India and suggests ways and means o f solving some o f the important problems related to such investment. This article is a revised version o f the paper presented by the author in the seminar on **Fublic Expenditure on Education and Defence in Deve- loping C a ttfitrk s '\ sponsored by the University Grants Commission, in New Delhi.

T here are two m ajor issues relaiing to education planning m our country th a t need to be focussed. They a re :

(1) The growth in public ■ investment in education in the

post-independence era, and the various problems involved in this growth in our country in particular and the deve- lop ii^ economies in general.

(2) The sources of educational investment. It is attempted to ascertain the role of different sources of educational finance and to find out their relative impcftance with a view to

- determining, (a) the adequacy o f and the steadiness in the flow o f funds, (b) the degree

• o f dependence on different Sources, and (c) the ways to

•solve some of the im portant financial problems o f education.

*This is no exhaustive ana

lysis of financial problems of Indian education. It suggests son^ ways and means to raise the investment resources for

education and solve some critical problems.

I

Several Asian, Latin American and African countries are economically backward because they are educationally backward and vice versa. This is a vicious circle, ‘chicken-and-egg’ relationship as an economist (Vaizey, 1962) himiorously but rightly put it. Capital formation, an essential thread of economic development, depends upon the level of human capital formation. If there is under-investment in human capital, the rate at which additional physical capital can be effectively utilised will be limited, as technical, professional and administrative personnel is needed to make productive use of material capital. In the developing economies the absorptive capacity for physical capital has proved to be low because

the rate of human capital formation has failed to keep pace with the accumulation of physical capital (Horvat, 1958).

This vicious circle can be broken only by making heavy investments in human capital formation. Investment in human capital takes various forms (Schultz, 1961). One of the important categories of activities that improve human capital is investment in education.

Investment in education has been increasing at a faster rate all over the world both in the advanced and the developing economies than the rate of increase in GNP

(Edding, 1968) Evidence is provided in Table I.

Investment in education in developing economies even though it can be associated with high rates of return^ poses a serious problem for a variety of reasons:

(a) For the developing economies allocating adequate investment to education is di&;ult, because of scanty resources both in quality and quantity.

(b) The characteristic features of our education ex

plain why the resources allocated to education cannot be wholly treated as investment outlay. To the extent that the consumption part and invest-

T a b l e IFubUc Expenditiire o h Education

Public expenditure

As % o f GNP

Per inhabitantys $

Averageannual

increase(1965-72)

%

Average annual

increase in GNP

(1965-7^ %

World* 5.7 75.6 11.6 9.7Africa 4.3 10.3 12 2 8.8America 6 2 170.3 11-2 8.4Asia* 4.0 14.'3 14.1 13.3Europe 5.3 166.1 12 2 10.5Oceania 5.8 148.0 16.0 8.6Developed countries 5.9 188.7 n .7 11.7Developing countries 3.7 8.6 10.4 8.8

^Excluding People’s Republic of China, Democratic Republicof Korea and Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

Source: M.S. Adiseskiah (1977)

ment part are inseparable, the optimal all<K;ation of resources to education has two aspects: one, when we think of education as a consu- Hier good, it becomes something on which we should save, since savings are necessary for investment, and they are obtained by economising on consumption. But when we think o f education as investment it becomes some- tWng not to be economised, but emphasised on. We seek to expand investment, and so we seek more educational investm ent (Galbraith, 1962; and Meddox, 1962). The inability to isolate the investment c<%Dsponent in education, thus does not allow us to allocate optimal resources for education. Two, education being a mixture of the two, and having innun^rable spill-over effects to its credit, most of which cannot quantified and in some cases not even identified.

does not permit of making correct estimates of rates of return to it, which are often advocated as criteria for investment allocation.

(c) Education is a sector where the gestation period is rather long, lo n ^ r than many other types of capital formation and growing economies can hardly afford to wait for such a long period as 15 or 20 years.

(d) The developing economies not only cannot afford long gestation periods after making heavy investment in education, but also cannot afford to face the consequences arising out of long gestation periods in the form of inflationary trends.

(e) Further, several studies (Psacharapolous, 1972) indicate that the social rate of return to education in the developing economies is less than the alternaiive rates of

I HOWE (INDIA) PRIVATE LIMITED \f CONSULTING ENGINEERS II PLANNING-DESIGN-CONSTRUCTION \I SUPERVISION I

i Marine and Harbour Engineering, Bulk Material ^f Handling and Processing Indusrial Plant Layout |i and Design, Food and Agriculture (All types of Ii Grain Handling, Processing and Storage, Food It Mills, Flour Mills, Matt and Sugar Plants, Fish ^t Processing Plants, Vegetable Plants, Fertilizer It Plants) and Nuclear Engineering. I

I Howe (India) Pvt Ltd IJ Howe India House |I ̂ 81, Nehru Place •J New Delhi 110 019 {{ Tel. Nos. 681545 |I 681546 I{ 681547 II Telex HOWE IN 2737 |

‘_____________________ j

return, on the one hand, and less than the private rates of return of education, on the other, which implies that investment in education is not scKsially profitable.*

(f) It can be argued that though the benefits of education flow after a long period, yet these benefits accrue for a long period, say over a 30- year period, while the useful life span for other investments tends to be shorter. So this fact should lead to giving greater weightage to education than other types of investment. But it should be noted that as the appropriate rate of discount is high, which is often the case with projects with long ^ s ta tio n periods, the relative case for investment in education becomes weak.

(g) Streeten (1972) rightly observes that “ there exists no determinate functional relationship between inputs and outputs, partly t^cause success is contingent on complementary measures” (p. 139). This leads to wider margin of error in educational planning.

(h) Human capital and physical capital are complementary in the process of economic growth. L a r^ physical resources are prerequisite to investment in human capital.

Scanty physical resources affect the investment outlays in human capital in two ways; one, it will not permit allocating large amounts to human capital directly as discussed above, and second, it does not allow allocation indirectly since rapid expansion in human capital resources, given physical resources, leads to problems of unemp- lojinent. Unemployment is both an economic and political problem and an economic and social waste. This goes against

investing more in human capital formation.®

(i) Finally, a more important feature of educational investments is that they are pet- missive and form a necessary condition for economic growth but it is not a sufficient condition. Streeten (1972) finds that educatioft creates “ opportunities for output growth without being its sufli- cient condition” (p. 139).

Social Servica SectorFor these re^ons, education

is still not included in tlw lisi of productive sectors. On the other hand it is treated as a social servia; sector and the governments’ contributions to education in most countries come from the revenue accounts of the b e gets, and not from th? capital aojounts.^

Table II gives a picture of growth of plan investnwnt in education in India during the five year Plans. The investDKnt increased from Rs 153 crores in the first five-year P k n to Rs 1955 crores (pro- jH>sed) for the sixth five-j^ar Plan. It can be observed that tlte emphasis on elenwntary education has g r^ua lly decreased. Fiftysix per cent of the total investment in education was made at the elementary level during the first Plan and the figure had falkn to 32 per cent in the fifth Plan. However there is a rise in it in the draft sixth Plan. As against this the priority given to university level education has increased from nine per cent to 23 per (»nt during the first five Plans. However, the emphasis on secondary education has been more or less constant.

The total plan investment in education has increased by more than eight tinKs during

the five five-year Plans. I t may be n o t ^ that all th is rise in Plan expenditure is not in real terms. The figures are in current prices. When we study educational expenditure, it should be in real terms, Le., expenditures at constant prices. But only the figures a t current prices are available. We find no accurate method of converting them into constan t price figures, for the pri£« indices available do not exactly reflect the weightage o f various items that enter into education ; ‘industry’. The K-othari Commission in our country and the Robbins Commission on Higher Education in the UK also feh that there was no accurate method o f expressing the expenditures on education in terms o f constan t prices, bseause no price indices are available which properly correspond to the individual components o f

this expenditure. But the fact remains that the eight-fold rise in expenditure on education in India does no t reflect the correct picture o f t l» real increase in investment.^

Nevertheless, i f we consider the non-Plan expenditure also which has been more than P lan exj^nditure®, it is evident that there is remarkable growth in educaitional expenditures. Expenditure on education as |K r € ^ t o f national income increased from 1-2 in 1950-51 to 2 .4 by 1960-61 and 3-3 (estimate) by 1973-74.

Such a rise in educational expenditure in independent India has been inevitable for three im portant reascms:

(a) Educational facilities available in the pre-independence period were insig^i- ^ a n t . Independence has created an almormal increase in the social demand for edu

cation and expenditure had to cope with the demand.

(b) Building up a new socioeconomic system after the «ad o f the colonial rule re- quii%d large s<^e manpower with varied skills; so the government could not but ex- p ^ d educational investments.

(c) Government policy towards equality in education led to the ^ w t h in educational expenditures, since it involves huge subsidies at all levels o f education to a substantial number o f students particularly belonging to weaker sections.^

However, the figures of educational investnK^nt as a per cent o f national income are very low in India as compared to the figures in other countries, as can be seen from Table III.

While speaki^^g about investm ent in education, education

ists often compare it with defence expenditure, which is regarded as the most unproductive expenditure. In India, as in many other developing and developed countries, defence expenditure has been increasing a t a fantastically high rate compared to educational expenditure. The average rate o f growth o f defence expenditure was m ore than 40 per cent per annum during the period 1951-52 to 1974-75. Even in absolute terms we spend more on defence that on education. There is every scope o f increasing the educational budget at the cost o f the defence bill. F or example, in France there has been rapid increase in the educational budget after the end o f the hostilities in Algeria (Phillips, 1975:82).

Investment in education com petes, however, not only with m ilitary expenditure (Table IV)

Table Q

Oatlay/Ej^enditure on Education in Five-Year Plans(Rs in orores)

FirstPlaii

& coadPlan

ThirdPlan

Iiiter-regnum

FourthPlan

F ifthPlan

SixthP la n t

1. Elementary* S5 95 178 65.3 234.7 410 900(56) (35) (30) (20) (28.5) (32) (46)

2. fecondary 20 S i 103 52.6 118.3 250 300(13) ( m (18) (16) (14.4) (19) (15)

3. University 14 48 87 77.0 183.5 292 265(9) (18) (15) (24) (22.3) (23) (14)

4. Other (General)** 14 30 116 46 161.0 140 340(9) (10) ( m (IS) (19.6) (10) (18)

Total-G eneral 133 224 484 240.8 697.3 1092 1785(87) (82) (79) (7S) (84.8) (85) (93)

5. Techni<^l 20 . 49 125 80.7 125.4 156 150(13) (18) (21) (25) (15.2) m (7)

Grand Total 153 273 589 321.5 822.7 1285 1985)(100) (100) (100) (100) (100) (100): (100)

Note ; Percentages to to ta l education (youth

^ v e n in brackets. ^Including pre-school edacation. ♦♦Includes teacher edu<^tion, social cultural programmes etc j'D raft

Sources ; Education m tlte F ifth Five Year Plan 1974-79. FifthFive Year Plan 1974-79, and Draft Five Year Plan 1978-83.

but also with other economic and social activities. Table V throws some light on the place

accorded to education relative

T able I I I Jnvestment in Education as a

Percentage of GNP

. Austria 1970 ^ .3Japan 1971 4.3Senegal 1970 6.7United kingdom 1970 5.8Algeria J970 9.0Ghana 1970 4.7Zambia 1971 5.6China—^Taiwan 1973 3.3Zaire 1970 5.7Greece 1971 2 .2Oman 1972 2-3Iran 1971 3.1Mali 1972 4 6Bangladesh 1973 1.2Canada 1971 8-2Netherlands 1971 7.7Sweden 1970 9 .0USA 1970 5.8Chad 1970 4.3

. Kenya 1970 5.3Chile 1969 5.4Tanzania 1971 4 5Ethiopia 1972 2.8Spain 1970 2.4Pakistan 1972 1.3Iraq 1970 6.7Morocco 1970 4 1Venezuela 1970 4 .9India 1971 2 .6

Source: World Bank (1974)

T able IVDefence Expenditure in India

Total 0 • /'odefence of

expendi GNPture Rsin crores

- 1951-52 196 2.01955-56 306 2,11960-61 304 2.1

- 1965-66 8«5 4.01970-71 1199 3.31974-75R 2157 3.7

R ; Revised Estimate Source : India 1976 and

volumes.other

to other competing sectors in the economy in the fifth and the sixth Plans. It can be seen that education is the sector where just three per cent o f the to tal Plan outlay was allocated which is the minimum figure in the fifth Plan and still less (2 8) in the sixth Plan.

A declining trend in the investment outlay for education in the five-year Plans has already been noted earlier. Thus

in vestment in education in India has been inadequate and perhaps this inadequacy o f investment has bsen the main reason for our failures in fulfilling the Plan as well as constitutional objectives o f education, such as universalisation o f prim ary education, hundred per cent literacy, balanced development in education and equalisation o f opportunities for education.

II

Now about the sources o f education investment in India. Nowadays we have a multi- source finance system for various reasons. Investment in education stems from both external and domestic sources.

External sources o f finance can take different forms as noted by Phillips (1964, 45), They arc:

(a) Financing o f development measures which increase the revenue raising capacity of the countries needing aid. on the assumption that this will result in an increase of revenue allotted to education;

(b) Adding to developmental loans or grants extra sums to take care o f educational im plications;

(c) Loans, credits, or grants for specific educational p rojects; and

(d) Long-term loans at low rates o f interest, credits

or grants for the specific p u rpose o f providing fo r a country ’s educational infrastructure.

These various forms of finance can spring from in ternational organizations such as IBRD, IFC, IDA, UN, and its agencies such as UNBSCO, UNICEF, regional organisations such as OECD, EEC, non-governmental organisations such as the Rockefeller Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation, Peace Corps, and voluntary services overseas, industrial companies, trade unions, and from the

governments o r private p a rties o f the foreign countries.

Foreign aid, for a long time has been only in the form of offering scholarships in the aid-giving country or in the form of equipment. But of lale, project aid has become a good deal more plentiful. Direct teaching aid is also made available under the scheme such as American Poace Corps workers, and the corresponding British system, as well as by m^ans o f teaching exchange (Hicks, 1969, Pp 390-1).

The role of external aid in

Tablh V

Outlays in the Fifth and the Sixth Five-Year Plans

(Rupees in crores)

Sector V Plan 1978-83 Plan Percentage increase in 1978-83 Plan over the V P lan

Agriculture and alliedactivities 4302 (11.0) 8600 (12.4) 99.5

Irrigation and floodcontrol 4226 (10.7) 9650 (13.9) 128.3

Industry and minerals* 7362 (18. 7) 10350 (14 9) 40.6Energy, science and

technological dev. 10291 (26 2) 20800 (30.0) 102.1Transport and com

munications 6917 (17.6) 10625 (15.3) 57.6Special services 6224 (15 8) 9355 (13.5) 50.3

Education 1285 (3 3) 1955 (2 8) 52.1Health and fam'ly

welfare 1179 (3.0) 2095 (3.0) 77.1Housing and urban

development 189 (0. 5) 2540 (3.7) 1243.9W ater supply 971 (2.5) 1580 (2 3) 62.7Social welfare and

nutrition 202 (0. 5) 305 (0.4) 51.0Backward class and

harijan welfare 327 (0. 8) 545 (0. 8) 66.7Othersj- 1071 (2-7) 335 (0.5) —68.7

Grand Total 39322 (100) 69380 (100) 76.4

• Excluding Energy, f Rehabilitation, Labour welfare etc. Figures in parantheses are percentages to the Grand Total.

educational bills o f the developing economies is not insigni- iicanf. W ithout external aid o r different forms o f external finaitce, few developing countries could have expanded their educational systems as rapidly as has been the case. Throughout the developing world aid accounts for about eight per cent o f total educational bills, and in some coxmtries like Chad 40 per cent o f the annual education budget comes from aid (Eedle, 1971; World Bank, 1974; and also Phillips, 1967). In this article we concentrate on the domestic sources o f educational finance only. The domestic sources o f finance are bo th public and private. They are:

(i) funds from the central government, (ii) funds from the state governments, (iii) grants from municipalities, district boards, etc., (iv) funds from the universities, (v) grants from agencies o f central government such as ICSSR, UGC, etc., (vi) Endowments, (vii) Fees, fines etc., (vlii) Gifts,

donations etc., (ix) Loans, and (x) other sources like income from the publications of the institution, and from auxiliary services, etc. (particularly at higher level).

These various sources of educational finance can be conveniently divided into three groups:

Government Funds include (a) the budget/plan allocations both by central and state governments and the grants from their agencies such as UGC, IGSSR etc. Thus items (i), (ii) and (v) given above come under this category. Goverrmient funds are mainly formed of the lax-revenues -b o th direct and indirect; and (b) Funds from local bodies which come from the district/taluka/village boards out o f the local tax revenue. Funds are also made available by the zilla pari- shads, blocks, coiporations, etc.

Finances from the government flow to education from

( i) general taxes, ( ii) earmarked taxes, and (iii) cesses.

The allocation to education from general taxes in all countries is the major means of educational finance. Specific taxes in connection with education such as taxes on manufacturing industries and trade towards financing technical and professional education, taxes on farmers towards agricultural education etc., are not totally absent, but very rare. Cesses are in fact another form of earmarked finance and they are still narrow in scope in using the lesources.

Endowments form another source of educational finance. This includes funds from donations, gifts, loans and other private sources.

Parental Expenditure: Expenditure incurred by the parents/guardians o f the pupils or by the pupils themselves is an important part o f educational finances. This expenditure is conveniently divided into, (a) fees, and (b)

other expenditure, which includes expenditure on books, stationery, transport, hostel and other similar maintenance expenditure.®

M ost studies concentrate on fees only and ignore the other sources o f educational finance mainly because of non-availability o f data.

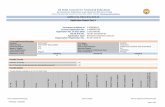

The graph below gives a clear picture o f the sources o f educational investment.

The D ata are indicated under four heads: (i) government (central/state) souices, (ii) local bodies, (iii) fees, and (iv) endowments and others.

Correlation coffiecients have been calculated between these major sources o f educational finance to find the degree o f association between them both across time-series and by states. The coefficients are piesented in Table VI.

After the attainment of independence education has received an honourable (though not adequate) treat-

Sourc«s o f Investm ent in Education in Ind ia

S e lf Finance (Income from p u b ll- s a l lo n s , computer, e tc . )

V is ib le invisible

P^regone E arnings

M aintenance G if ts (9ooks, S ta tio n e ry T ranspo rt, e t c . , ) C en tra l S ta t

D is t r ic t O ther

(x S sS ^ M c , ^^JT iic ipalities Others • tC . )

ment by the central and the state governments. Governments have been the major source spring o f investment in education.

Governments contributed Rs 642 million (56 per cent of the to tal investment in education) at the inception of planning in the country. By the end o f a decade the figure crossed Rs 2DOO million (67 per cent) rising at the annual growth rate® of 13-97 per cent and by the end o f another

decade it shot up to the level o f Rs 7616 million (76 per cent) at more or less the same growth rate.

It may be noted that governments’ contribution increased hot only in absolute terms, but also per pupil. Governments’ contribution per pupil almost doubled in a decade from Rs 24 in 1950-51 to Rs 45 by 1960-61 and again doubled to Rs 94 by 1969-70. That means it increased at the rate o f 6.34 per cent per

T a b le VI Correlation Coefficients

Govt. Local Fees bodies

Endow- Totalmsntsandothers

A. Correlation coefficients betweenfinances from various sources

^ (1950-51 to 1969-70)Government . 976 . 995 . 994 1.000Local bodies - 982 .997 .980Fees .986 . 996Endowments and others . 995TotalB. Correlation coefficients between •

finances from various sources per pupil (1950-51 to 1969-70)

Government 151 .962 .902 .998Local bodies • 235 .372 .201Fees .871 .970Endowments and others . 922TotalC. Correlation coefficients between

finances from various sources 1969-70 (By states)

Government . 796 .732 .828 987Local bodies 592 .820 .833Fees ■752 .815Endowments and others -881TotalD . Correlation coefficients between

finances from various sources per pupil 1969-70 (By states)

Government — -2 1 6 — .231 .116 -938Local bodies -094 — .035 — .102Fees -475 .100Endowments and others .385Total

annum during the 20 years under study. It is slightly less than the growth rate o f enrolments, which is 7 .0 per cent per annum. The correlation between governments’ contribution and enrolments is as h 'gh as 0-988; and the coefficient between enrolments and the percentage share o f the governments’ contribution in to tal investment in education is also as high as 0. 953 and both the coefficients are significant at one per cent level of signifiance^®.

Unequal SharesHowever government share

has not been equal among all the states o f the country. For instance, 91.8 per cent o f the to tal investment in education in 1969-70 in Jammu and Kashmir cams from the gov- ernmsnt, while the corresponding figure was 65 per cent in Gujarat. Again there is much inequality both in the to tal and government investment in education per pupil. Government investment per pupil is as low as Rs 53.97 in U ttar Pradesh and it is as high as Rs 187 in Himachal Pradesh. This explains the inequality in the to tal investment per pupil. It is Rs 77.56 per pupil in U ttar Pradesh and Rs 207.85 in Himachal Pradesh.

While distributing the tax revenues the central government should seek to equalise educational opportunities among the richer and the poorer regions o f the country. The level o f the funds from state governm:nts and non- governmmtal sources like local bodies, fees, endowments and others in any region should be considered while determining the level o f central government contribution to that region for education.

The poor state should receive more funds than the richer state. O f course, all this should be based upon the number o f enrolments. The central government could follow ‘equalisation policy’ with respect to investment per pupil, so that there are not wide inequalities in the qualitative aspects o f education in the form of availability o f physical resources per pupil. The same principle should guide the state governments in allocating tax revenues to education among various districts.

Table VII gives a detailed picture o f educational finance by source during the 20 years o f study i.e., 1950-51 to 1969- 70.

Table VIII gives a yearly picture o f educational finance by sources in various states o f the country in 1969-70.

Higher EducationThe figures in Table VIII

reveal that 22 per cent o f the total government investment in education goes to the higher level, and at the higher level professional colleges receive top priority. School education receives 78 per cent o f the to tal government contribution to education—29 per cent is spent on primary schools, 20 per cent on m ddle schools and 28 per cent on high/higher secondary schools. Professional and technical education at the school level receives just1.43 per c^nt o f the to tal government contribution.

Viewed from another angle, primary schools are ahnost financed by the governments—90 per cent o f the prim ary school finance comes from the government sources, 84 per cent o f the middle school finances, and 73 per

cent o f the high/higher secondary school finances, while a t higher level, governments contribute is to the extent of 58 per cent; professional and technical education both at the school level and higher level are b^ing financed to a greater extent by the government (82 and 76 per cent respectively).

The functional classification in Table X reveals that every item of the educational budget receives large contributions from governments; 75 per cent o f direct expenditure and 73 per cent o f indirect expenditure comes from the governments. Governments meet 90 per cent o f the total expenditure incurred on direction and

inspection, and o f the other items governments contribute a sizable proportion except in hostels where only 45 per cent is met from the government funds; another 41 per cent comes from fees. Endowments contribute just 10 per cent o f the budget o f the hostels, 17 per cent o f the bill o f the construction o f the buildings, 12 per cent o f the bill o f equipment and other non-recurring expenses and less than 10 per cent o f the total amount o f scholarships.

Local bodies constitute another important source of educational investments; 63 per cent o f the prim ary schools, and 39 per cent o f the secondary schools are run by

local bodies, Altogether 41 per cent o f the schools in the country are under the control o f local bodies, while a little less than 0 .5 per cent of higher educational institutions are controlled by them.

However only less than five per cent of the school finances come from the local bodies. This is quite uneven. Even though 63 per cent o f the primary schools are managed by local bodies 90 per cent o f the finances of all primary schools are provided by the governments. At the same time it may be noted that 96 per cent o f ihe finance.s that come from the local bodies go to schools. Even though during the post-independence

period the contribution o f the local bodies grew in absolute terms at the rate o f seven per cent, as a percentage o f the total educational investment it fell from 11.69 in 1949-50 to 3.73 per cent by 1969-70.

In no state was the share o f the local bodies greater than 4.42 per cent in 1969-70 What are the main reasons for the poor performance o f the local bodies? First, the “ local bodies were created by the British rulers not so much because they were anxious to grant autonomy in local administration to the people but because they wanted to relieve the district officials o f some of their administrative burdens.” (Misra, 1962 ; P 349). They

(Oyer to P. 101)T a b le VII

Vcarwise Investment in Education—By Source

Govt. Local Bodies Fees Endowments and Others

Total

1 2 3 4 5

1950-51 A 642478 124087 233272 132885 1133622B 56.67 10.95 20. 58 11.73 100.00C 24.14 4.66 8. 77 4.99 42.61

1951-52 A 703912 139166 269626 132915 1245619B 56.51 n .1 7 21.65 10.67 100.00C 26. 49 5.24 10. 15 5.00 46. 88

1952-53 A 802277 135190 297113 141847 1376428B 58.29 9. 82 21.59 10.31 100.00C 29.15 4.91 10. 79 5.15 50.01

1953-54 A 8539.74 145143 329055 149245 1477417B 57. 80 9.82 22.27 10.10 100.00C 29.31 4.98 11.29 5.12 50.70

1954-55 A 988488 150912 353361 157332 1650130B 59.90 9.15 21.41 9.53 100.00C 31.61 4.83 11.30 5.03 52.78

1955-56 A 1172050 164448 379033 181980 18975JIB 61.77 8.67 19.98 9.59 100.00C 34 55 4. 85 11.17 5.36 55.93

1956-51 A 129561^ 176158 4010C2 190164 2062940B 62 80 8. 54 19.44 9 .22 100.00C 35.98 4.89 11.14 5.2S 57. 30

1957-58 A 1575412 171823 435894 22D811 2403940B 65.53 7.15 18.13 9.19 100.00G 41.47 4. 52 11.48 5. 81 64.29

(Continued)

1 2 3 4 5

1958-59 A 1777623 165029 484356 236724 2663781B 66 73 6 20 18.18 8. 89 100.00C 42 86 3.98 11.68 5.71 64.23

1959-60 A 2020532 I97I48 521396 257482 2996558B 67.43 6 58 17.40 8 . 59 100.00C 45.29 4 .42 11.69 5.77 67.16

1960-61 A 2340913 224915 590258 287715 3443801B 67.97 6 53 17.14 8.35 100.00C 48. 8J 4 .69 12 31 6 .00 71.80

1961-62 A 2718355 261864 656066 32722J 3963505B 68. 58 6 61 16. 55 8.26 100.00C 50.08 4.82 12.09 6 03 73.02

1962-63 A 3003410 291446 737330 357259 4394450B 68.35 6 63 16.78 8.13 100.00C 51.80 5.03 12.72 6 16 75.80

1963-64 A 3344934 289700 823577 382864 4841084B 69.09 5.98 17.01 7.91 100.00C 54 20 4.69 13-35 6 20 78.45

1964-65 A 3708571 310940 872302 418042 5399855B 68.68 5.76 16.15 7.74 100.00C 55.01 4.61 12.94 6.20 80.10

1965-66 A 3183838 289751 878797 32075-^ 4673140B 68.13 6 23 18. 81 6. 87 100.00C 45.13 4.11 12.46 4. 55 66.23

1966-67 A 4811338 379916 1079908 537654 6808817B 70.66 5.58 15.86 7.90 100.00C 65.28 5.15 14.65 7. 30 92.39

1967-68 A 5804343 447612 1159670 606549 8018174B 72.39 5. 58 14.46 7. 56 100.00C 75.75 5.84 15.13 7.92 104.65

1968-69 A 6580391 431452 1264863 706982 8983688B 73.25 4.80 14.08 7.87 100.00C 79. 29 5.20 15.24 8.52 108.25

1969-70 A 7616153 375703 1341655 747498 10081009B 75.55 3.73 13.31 7.41 100.00

Growth RatesC 94.00 4.64 16.56 9.23 124.42

1950-51—54-55 A 11.11 10.44 11.08 10.46 10.97

1955-56—59-60 A 11.51 10. 30 10. 86 10-96 n .2 4

1960-61—64^5 A 11.19 10 78 11 06 10.95 11.16

1965-66—69-70 A 12.29 10.67 11.06 12.17 11.99

1950-51—59-60 A 11.40 10.45 10- 88 10.82 11.15

1960-61—69-70 A 11.36 10.69 10.96 11.11 11.24

. 1950-51—69-70 A 11.39 10.71 10.96 10.97 11.21

Nofe : A Rupees in thousands, B Percentages to total, C Rupees per pupilSources : Education in India, and Statistical Abstract o f India (Various volumes).

T a b le VIIIStatewise InTestment in Education—By Source; 1969-70

Government Localbodies

Fees Endowments and others

Total

Andhra Pradesh A 508803 7661 58438 46256 621158B 81.91 1.23 9.41 7.45 100C 99.12 1.49 11.38 9.01 121.01

Assam A 232404 1814 36925 14414 285557B 81.39 0.64 12.93 5.05 100C 98.23 0 .77 15.61 6.09 120.69

Bihar A 327300 8614 88221 49329 4 7 3 4 ^B 69.13 1.82 18.63 10.42 100C 56. 11 1.48 15.12 8.46 81.17

Gujarat A 372902 25448 121774 55692 575726B 64.77 4.42 21.15 9.66 100C 85.84 5. 86 28.03 12.80 132.53

Haryana A 147784 680 61619 33829 213912B 69.09 0 .3 2 14.78 15.81 100C 105. 56 0.49 22.59 24.16 152.79

Himachal Pradesh A 97802 202 6039 4727 108707B 89.97 0.19 5.56 4.35 100C 187.00 0. 39 11.55 9.04 207. 85

Jammu-Kashmir A 76169 4957 1885 83011B 91.76 * , 5.97 2.27 100C 138.49 9.01 3.43 150.90

K arnataka A 434381 3807 64366 53152 555706B 78.17 0.69 11.58 9.56 100C 93.84 0. 82 13.90 11.48 120.05

Kerala A 553605 528 48507 27740 630380B 87. 82 0.08 7.69 4.40 100C 109.70 0.11 9 .97 5.70 129.60

M adhya Pradesh A 505569 8811 52268 33972 600620B 84.17 1.47 8.70 5.66 100C 117.19 2.04 12.12 7.87 139.29

M aharashtra A 1002966 130689 157956 107318 1398929B 71.70 9.34 11.29 7.68 100C 97.08 12.65 15.29 10.39 135.41

Orissa A 223478 5657 20164 31349 280648B 79.63 2.02 7.19 11.17 100C 93.58 2.37 8.44 13.13 117.52

Punjab A 264595 872 52623 48238 366328B 76.23 - 0.24 14.36 13.17 100C 126.30 0.42 25.12 23.03 174.86

Rajasthan A 326555 10848 42663 33918 413984B 78. 88 2 .62 10.31 8.19 100C 134.00 4.45 17.51 13.92 169. 87

T am ibadu A 749428 44142 70695 54206 918471B 81.60 4.81 7.70 5.90 100C 106.51 6.27 10.05 7.70 130.54

U ttar R-adesh A 758398 44804 203994 82638 1089834B 69.59 4.11 18.72 7. 58 100C 53.97 3.19 14. 52 5. 88 77.56

West Bengal A 586048 15595 198592 41650 841885B 69.61 1.85 23. 59 4.95 100C 86. 26 2.30 29.23 6.13 123. 92

Note : A—Rupees in thousands, B—Percentages to total, C —Rupees per pupilSources : Education in India, and Statistical Abstract o f India.

were not created for educational development. Educational development evenlater has not b^en regarded as an im portant function of the local bodies. W ith their own meagre resources com- oeting for various objectives such as construction o f roads, improving sanitation, providing water facilities etc., local bodies could not pay due attention to education. That is the reason why even the schools managed by them receive finances from government funds.

But in the federal system with decentralised planning, local bodies like zilJa pari- shads, panchayats etc., bsing the micro units o f educational planning, have a significant role to play in the development o f education in general

and, in particuhr, in its balanced development between the rural and urban areas, and among different socio-economic classes o f population. Local authorities should raise theircontribution by various ways, e.g., the district authorities, familiarly known as thezilla parishads, have an authority to levy a cess on land revenue for education.

As the Kothari Commission suggested, the state shouldprescribe the minimum cess to be levied by the zilla pari- shad and also authorise itto raise the same voluntarily up to a prescribed maximum. The commission also recommended a revision in the grants- in»aid policy both to the zilla parishads and the municipali- lities, under which their resources are taken into account,

Tabi e IXCentre-State Partnership in Financing Education

(In percent)

First & cond Third 1965-Plan Plan Plan 66

Central goiernment 6.84 17.51 20.11 21.71Direct participation 4.82 10.75 10.63 11.43Sponsored programmes 1.40 1.45 1.68 1.80Assisted programmes 0.62 5.31 7.80 8.48

State government 93. 16 81.49 79.89 78.29Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00Total (in crores of Rs.) 414. 55 849. 57 1655 36 414 57

Source: H.N. Pandit(1976:21).

they are economically used and the objective o f equalisation is attained.

S'milar to the cess on land revenue, why can’t there be a cess on the profit-tax levied on

industries? Such a levy may make a valuable contribution. M ost industries earn largeprofits without giving much support to the socio-economic infrastructure o f the areas

T a b le X

Sources of Direct Expenditure on Education—By Levels/Types: 1969-70

(Rupees in million)

Government Local bodies Fees Endowment & others

Total

Primary 1889 (29.7) 137 (43. 5) 48 (3.8) 33 (5,6) 7106 (24.5)[89.7] f6.5] (2.3] [1.5] [100]

Secondary 3069 (47.6) 163 (51.8) 543 (43 2) 190 (32.7) 3965 (46.1)[77.4] [4.1] [13.7] [4.8]

(2.1)[100]

(1-3)Other schools 92 (1.4) 3 (0.9) 4 (0.4) '1 2 112[82.11 [2.7] [3 6] [10.7} [100]

AH schools 5050 (78 3) 303 (96 2) 595 (47.3) 235 (40. 5) 6183 (71.8)[81.7] [4.9] [9.6] [3.8] [100]

Colleges (general) 359 (5.6) 2 (0.7) 318 (25.3) 110 (18 9) 789 (9.2)[45. 5J fO-3] [40.3] [14.0] [100]

Other colleges . 624 (9.7) 9 (2.8) 104 (8 2) - 90 (15.5) 827 (9.6)[15.5] [1.1] [2.5] [10.9] [100]

Universities* 421 (6. 5) I (0,4) 241 (19.2) 146 (25. 1) 809 (9.4)[52 0] 10. IJ [29.0] [18.1] [100]

All higher 1404 (21.8) 12 (3.8) 662 (56.7) 346 (59.6) 2424 (28.2)[57.9] [0-5] [27.3] [14.3] [iOO]

All levels 6453 (100) 315 (100) 1257 (100) 581 (100) 8607 (100)[75.0] [3-7] [14.6] [6. 8] [100]

Note: *Includes institutions deemed to be universities. Figures in curved brackets and square brackets are respectively percentage to column and row totals.

Source ; Education in India, 1969-70

where they are established.There is every justificationfor some k'nd o f a levy on an industrial unit to raise the educational levels o f the population residing in areas from which its labour force is drawn. Similar levies can be imposed on buildings that are in the jurisdiction o f local bodies. Thus local bodies can be made responsible for raising a larger part o f the educational bill, at least for the fixed investments (non-recurring expenditures) in education.

Fees collected from the pupils have been one o f the largest sources of educational finance in the country next only to the government contribution. This important component o f private investment in education which amounted to Rs 207 million in 1949-50, increased to the level of Rs 1341 million by 1969-70, that is at a rate o f 10 per cent per annum. How

ever the relative share o f fees in the total educational bill declined from 20.6 per cent in 1950-51 to 13.31 per cent by 1969-70. But during the same period fees per pupil doubled from Rs 8-8 in 1950- 51 to Rs 16.6 in 1969-70.

This increase a t an annual growth rate o f 2.4 per cent Is insignificant considering the increase in the general price level. It can be safely asserted that the burden on the pupils (particularly in the form of fees) has been lessened during this period.

There are laige disparities in the contribution o f fees among states. Fees form just six per cent o f the total educational investment in states such as Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh, while it is as h’gh as 21 per cent in Gujarat and 24 per cent in West Bengal. The coefficient o f correlation between fees

per pupil and the per capita income may give some vague picture o f egalitarian policy. The coefficient is 0. 5325.^^

Over 15 per cent o f the direct expenditure and six per cent o f indirect expenditure are met from fees. Around 27 per cent o f the educational finances at h ’gher level and 10 per cent at school level are contributed by the pupils in the form of fees. The very low figures at the school level is due to the provision o f free public education. Though fees form a significant part o f the total educational investment in India, there is large scope for widening this base.

There has been argument in favour o f using fee-policy as an effective instrument for regulating the galloping social demand for education (Azad, 1975 : Pp 199-200). Those who make such suggestions treat education at par with

other pub lic , utilities. This is unfortunate. I f such a policy is followed education will become a commodity for the privileged, mainly o f those in the upper income brackets. The objective o f fee-collection in fact was not revenue. In 1854 Wood’s Education Dispatch favoured introduction o f fee on two grounds: “People do not value anything that is given free, and the payment of a fee is an indication o f the seriousness o f purpose on the part o f the student or his guardian.” *̂

All over the world there have been arguments in favour of democratising ed u ca tio n -p ro viding education for all. Equalisation o f educational opportunities has b^en an importan t objective o f educational planning in the country. Fees should no t play the role that the price mechanism does. Afier all, fee is not price. On these grounds educationists

T a b le XIFunctional Classification of Investment in Education—By Source: 1969-70

Government Local Bodies Universities/Boards

Fees Endowments &Others

Total

A. Direct Expenditure 6453 (84 5) 315 (83.9) 102 (76.9) 1257 (93.7) 479 (76 8) 8607 (85. 2)[75. OJ [3.7] [I.2J [14 6] [5.5] [100]

B. Indirect Expenditure 1185 (15.5) 61 (16 1) 22 (16 2) 84 (6 3) 145 (23 2) 1498 (14. 8)P 2 9J [4 1] IL 5 \ [5 6] [9.7] i m

Direction and 2}8 (2.7) 22 (5.8) Neg Neg 230 (2 3)Inspection [90.5] [9.5] [100]Buildings 254 (3 3) 16 (4 2) 6 (4 2) 14 (1.0) 62 (10.0) 352 (3.5)

[72 2] [4.5] [1.6] [4 0] [17. 8J [100]Hostels 29 (0-4) Neg 2 (1.4) 21 (2 0) 7 (1.1) 66 (0.7)

[44 6j [2.8] [41.4] [10.6] flOO]Scholarships, stipends 456 (6 0) 4 5 (1 2) 8.7 (6 5) 16 5 (1.2) 9 .9 (1 6) 496 (4.9)etc [92 0] [0 9] [1.8] [3 3] [2 OJ [100]Equipment etc. 133 (1.7) 6 (1 5) (2 6) 9 (0.7) 22 (3 6) 173 (1-7)

[76 8] [3 2] [2 0] [5 1] [12 9] [100]Others 105 (1.4) 13 (3 4) 2 (I 6) 10 (1 3) 43 (6 9) 181 (1.8)

[58.2J [7. Ij [1.2] [9.8] [23.4] [100]Grand Total 7639 (100) 376 (100) 133 (100) 1342 (100) 624 (100) 10104 (100)

[75.6] [3 7] [1.31 [13 3] [6.2] [100]

Note : Figures in curved brackets and square brackets are respectively percentageto column and row totals.Source; Education in India, 1969-70,

like Phillips (1975 : P 88) argue for discouraging fee-payment, since “ it frequently excludes the underprivileged” and “ fees are a cause o f non- enrolment” in low income countries.

However there are people who argue for rationalising fee policy so that it promotes equality. In fact fees are far more egalitarian than government contributions. D ifferential fees—higher fees from the students who are of poor quality, and lower fees for those with reasonably good quality, as sug^sted by Azad (1975) improves the situation without adversely affecting the quality and standards o f education. Such a differential fees structure however should b2 complemented by a bulky student-grants-in-aid p rogramme, so that equality is also improved at the same time. The issue o f fees should not be looked in isolation. Fees involve cconomic-cum- egalitarian questions apart frcm implementation problems.

EndowmentsFunds from endowments

include endowment funds, gifts, donations and other kinds o f voluntary contributions from individuals aswell as from firms, trusts,churches, charities, etc. In earlier days no elaborateorganisation for educational finance existed in our country. “ Educational finance wasneither institutional nor self- financed. It was mostly connected with religious activities and in fact most o f the educational institutions were attached to temples o r mosques. Education was looked upon as an unproductive activity although there was sentimental willingness, to some

extent, to spend on education. In short education was looked upon as an object o f charity and whatever financial help was forthcoming was inspired- by a sense o f piety. The grants in cash or in kind by the rulers, gifts and presents comprised the sources o f educational finance” (Nanjudappa, 1976: Pp 20-25).

Steep FallEven a t the bsg'nning of

this century (1901-02) these sources contributed one-quarter o f the educational bill. In the states such as erstwhile Bombay and M adras their contribution was 32 and 29 per cent, respectively. (A. Misva, 1962). But by 1950-51 the figures a t all-India level came down to 11.7 per cent and it fell steeply to seven per cent by 1969-70, I t was just 2 .3 per cent in Jammu and Kashmir and 4 .4 per cent in Kerala.

However o f the total contribution from these endowments nearly 60 per cent goes to higher education. Similarly, more than 60 per cent o f institutions o f h'gher learning, 75 per cent o f the colleges for general education, and 57 per cent of the colleges o f professional education— are managed by private parties. A m ajor part o f the finances o f these institutions is provided by the governments and a considerably significant part by the pupils themselves in the form of h 'gh fees. But in terms o f management, higher education can well be termed as private enterprise in the country. At the school level 40 per cent o f all kinds o f schools are managed by the private parties; almost all o f them receive huge aids from the governments.

I t is interesting to note

that 17 per cent o f the primary schools are under private m anagement and 17 per cent o f the students at the primary level are in these schools. S'm larly 37 per cent o f the secondary schools are under the private management and 42 per cent o f the students at this level are enrolled in these schools. The same is the case with education at the higher level. Privately managed colleges form 62 per cent o f the total number of colleges, and on the rolls o f these colleges are 61 p^r cent o f the students. This shows that pupils are evenly distributed among public and private institutions.

However from the point of view o f finances these sources (endowments and other contributions) have b^en relatively less important. Thus there is a paradoxical situation with large number of

institutions under the private management with ' insignificant financial resources p rovided by these managements. Th s is no t the position in our country alone. All over the world private contribution to education in the form of donations, endowments and gifts has bsen decl'ning. For example, Vaizey and Sheehan (1968) observed that suchcontributions have fallen in British universities frommore than one-fourth o f the total resources ava-Iable to education in 1923 to one- tenth in 1950, and to one- fourtieth in 1965 (p. 124).In the finances o f higher education in the United States, private contributions havefallen from around 13.04 per cent in 1929-30 to 8 .5 per cent by 1971 ••72 (Carnegie Commission, 1973). Private sources therefore can no more h i reckoned as reliable

NOW!

TEASPACKED IN LOVELY NEW CARTONS TO

PRESERVE TASTE AND FLAVOUR BETTER !

From the high slopes of the Nilgirls. Taste great. S ta y fresh longer \

SPENCER & CO. LTD.Madras & branches

sources for investment in education.

Government’s role in educational finances has been significant. The basis for such large public investment in education must be found in the benefits of education. Public benefits also known as external benefits of education are innumerable. In fact the external benefits outnumbsr private benefits. In this context, Adam Smith (1776) rightly observed, “The state however, derives no inconsiderable advantage from their (the people’s) instruction. The more they are instructed the less they are subject to delusions o f enthusiasm and superstition, which among ignorant nations, frequently occasion

the m ost^dreadful disorders. An instructed and intell'gent people, besides, are always more decent and orderly than an ignorant and stupid o n e .. . They are more disposed to examine, and more capable o f seeing through, the interested complaints o f faction and sedition and they are, upon that account, less apt to be misled into any wanton o r unnecessary opposition to the measures o f government” , (p. 740).

Further, education is a sector which cannot be left to private parties completely as long as we aim at univer- salisation o f prim ary education, equality in educational opportunities, social justice and so on. M. Adeseshaiah (1977) rightly observes that

‘‘private financing, the market forces, cannot produce the education needed by the country b3causc o f the divergences between private and social costs and benefits, the non- m a-Jat forces that are a t work in every society—the demonstration effect o f the coexistence o f high levels o f education and high levels o f living intra-nationally and internationally, the human rights and the consumption imperatives o f education—all these together explain the political decision o f the large and growing public financing of education” (p. 488).

Thus for 3 variety of reasons the financial burden on the part o f the government has b^en mounting every year.

Public policy consists o f two strategies towards solving the financial problems: (i) curbing the demand for education (particularly at higher level), and (ii) reducing the financ'al burden on the public exchequer by encouraging private individuals to finance education. The former strategy consists o f selective admission policy. Recently it was suggested to delink degrees from the jobs. This is also directed towards the same objective. The second strategy consists o f a variety of measures like a stricter grant- in-aid policy encouraging p rivate philanthropy by fiscal and other concessions, in crease in fees etc. But neither

T a b i b XII

Number of Educational Institiitions in India—By Management; 1969-70

Level/Type Govt/GovtSponsored

LocalBodies

Universities/ Private GrandTotal

Aided Unaided Total

Primary* 82620 255953 63470 4998 68468 407041(2 i 30) (62. 88) (15.59) (1.23) (16 82) (100 00)

Secondary® 29713 47479 5 39942 6041 45983 123180)(24.12) (38 54) (Neg) (32 43) (4 90) (37 33) (100.00

Other schools £ 4290 2968 1 205977 1597 207574 214833(2 00) (1.38) (Neg) (95 88) (0.74) (76 62) (100. 00)

All schools 116623 306400 6 309389 12636 322025 745054(15.65) (41.12) (Neg) (41.53) (1.70) (43. 22) (100.00)

General colleges 493 14 70 1426 341 1767 2344(21.03) (0. 60) (0.30) (60. 84) (14,55) (75.38) (100.00)

Professional & other colleges** 1849 19 78 2061 471 2532 4478(41.29) (0.42) (1.74) (46.03) (10. 52) (56 54) (100 00)

Universities & institutions®® 51 1 96 25 15 40 178(28.65) (0. 56) (53 93) (14 04) (8.43) (22 47) (100-00)

All higher 2393 34 244 3512 827 4339 .7000(34. 19) (0.49) (3.49) (50.17) (11.81) (61.99) (100.00)

All levels 119016 306434 250 312900 13454 326354 752054(15.83) (40.75) (0.03) (41.61) (1.79) (43.40) (100.00)

Note; Total may not tally due to rounding up the figures Figures in parantheses are percentages to grand total.♦ includes pre-primary level also. @ includes middle level also. £ includes vocational/professional, technical, special, oriental and other schools. * • includes professional colleges (Degree, Post-graduate, and Undergraduate levels), teacher training, and other colleges. @@ includes universities, institutions deemed to be universities, institutions

of national importance, boards o f education, and research institutions. Source : Education in India, 196^70.

of these strategies has proved a success.^®

Ill

Our suggestions to improve the financ al condition o f the Indian educational system are two-fold. The first consists of suggestions to raise more investment resources for education, while the second deals with economising and improving the efficiency in the utilisation of these resources.

The responsibility o f investment a t various levels/iypes of education should be distri

buted among various sources. The local bodies (district boards and municipalities etc.,) should take the full responsibility o f primary education. The local bodies can mobilise the resources by imposing such levies as agricultural income tax, urban property tax, professional tax, etc. This will, apart from solving the financial problems, make the local people shoulder the respons bility o f educating their children. The responsibility o f professional/techn cal and vocational education both at school and h’gher

levels, and on-the-job-training should be undertaken by the private and public industrial undertakings. I f the respons'bility is not taken up by them, a technical/professional education cess, and a direct tax on industry may b3 imposed. There is every justification for this, since technically qualified people are employed mainly by industries.

The state governments should take the responsibility o f secondary education, and the central government that o f higher education o f gene

ra l type. This provides for a l a r ^ scope to have a uiiiforirt secondary school systeM throughout the state, arid A un fo rm hg h er educatioii throughout the Country with reasonable standards.

Harblson argues for im*̂ posing payroll tax propor^ txonate to the total labour force, and then to forgive part of the tax where satisfactory programmes o f education and training within industry are undertaken (see Higgins, 1967 : P 311).

A variety o f special educational taxes can b^ introduced;

T a b i e X TII

Number of Students in Educational Institutions—By Management: 1969-70(Figures in thousand)

Level/Type Govr/GovtSponsored

LocalBodies

Universit.’es/ Private GrandTotal

Aided Una'ded To*aI

(1) (2) (3) (̂ •) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Primary’̂ 6790 26508 r- - 6335 624 6959 40257(16.87) (68 85) (15 74) (1.55) (17 22) (ICO. 00)

Secondary® 8541 11894 3 13534 1244 14778 3522}(24.26) (33.77) Neg (38.43) (3.53) (41 96) (100.00)

Other schools£ 191 6S Neg 2194 64 2257 2517(7.60) (2 69) (87.18) (2. 52) (89.70) (100 00)

All schools 15526 38470 3 22 62 1932 23994 77993(19.91) (^9.32) (Neg) (28.29) (2.48) (30.76) (100.00)

General colleges 414 5 119 1299 144 1444 1981(20. 89) (2 04) (6.00) (65. 58) (7.29) (72.87) (100 00)

Professional & other colleges** 413 4 38 316 101 416 872(47. 36) (0- 51) (4 39) (36.18) (11.56) (47.74) (100.00)

Universities and institutions®® 17 Neg 160 1 2 3 180(9.16) (Neg) (88.67) (0 40) (I 17) (1.57) (iOO. 00)

All higher 843 9 317 1616 1863 3034(27. 80) (0 31) (10,45) (53 25) (8.16) (61.40) (100 00)

All levels/types 16669 38479 320 23678 2179 25857 81027(20. 57) (47.49) (0.40) (29. 22) (2 69) (31.91) (100.00)

Notes ; Total may not tally due to rounding off the figures Figures in parantheses are percentages to grand total.* includes pre-primary level.

@ includes middle level.£ includes vocational/professional, technical, special, oriental and other schools.

** includes professional colleges (degree, post-graduate and undergraduate levels), teacher training and other colleges includes universities, institutions deemed to be universities, institutions o f national importance, boards o f education, and research institutions.

Source : Education in India 1969-70.

taxable capacity can be in creased particularly when a link is clearly established between increased tax payments and increased level o f educational outlay. A t higher

-stages more resources can be mobilised by introducing I he often-discussed ‘graduate tax’-.̂ * Since people receive education a t the cost o f the society’s resources (with a little financial investmentof their own), there is every justification to ask them to pay a small percentage o f their earnings to the society in the form of ‘graduate tax’. Apart from introducing new specific taxes, an efficient way o f collection o f existing taxes improves the financial resources o f the exchequer.^®

A revision o f the existing student-fees structure is u rgently needed. A differential fees system as argued before, coupled with a better scholarships and stipends programme may, apart from providing more resources for education, improve the equality o f opportunity in education without affecting the standards of education. BJaug (1970) speaks about ‘Educational Vouchers’ originally proposed by Friedman and developed by Wiseman and Peacock. “The key to the voucher scheme is the distribution to all parents of vouchers exchangeable for education in any school, whether state or private, that satisfies minimum educational standards, the value o f the voucher being related to some notion o f the average cost o f education o f children o f different ages” (Blaug, 1970 : P 307). Though the scheme sounds well, the effectiveness o f the scheme in such poor countries as our’s is doubtful. Serious thought is necessary before it is actually taken up.

Lastly every effort should bs

made to encourage private contributions to education in the form of imposing no ceiJing on the tax-exemption for contributions to education. Ways should also be explored to appropriate the wealth and property o f the religious institutions for educational activities.

Apart from mobilising new resources, the financial problems in education can besolved to a substantial extent by more efficient utilisation o f resources. The Education Commission clearly pointed out that “ it is impossible to create an educational system which would meet the individual and national needs ifconventional techniques, existing practices o f underutilisation and wastage were to continue” (P. 486).

Better utilisation o f theexisting resources will in crease the input-output ratio o f the educational p rocess. Substantial economies can bs effected through introduction o f non-formal education. F or example, J.P. Naik (1975a) argues for abandoning the present emphasis on professionalisation of teaching, and suggests the harnessing o f services o f suitable persons from the community on the one hand, and the use of students as teachers on the other. Naik puts forth a bunch of suggestions to improve the efficiency o f investments or to reduce the costs o f elementary level education. They are : (a) increase in the teacher-pupil ratio by the adoption, if necessary, o f the double sh^ft system; (b) introduction o f large programmes o f part-time education combined with the multiple-entry system; (c) reduction in the expenditure on buildings through the use of local agency and materials;

and (d) reduction in the costs o f text books and teaching and learning materials by providing them free o f charge to all children on the school premises during working hours (Naik, 1975b : P 69).

The Measures like the reduction in the size o f the schools and c o lle ts and consolidation o f small units (e.g., the miniuniversities which are little better than post-graduate centres, and colleges with tiny population, and particularly the single teacher primary schools) and providing transportation and other infrastructure may result in some more economies. The argument is that there is underutilisation o f resources of the country’s educational facilities. A better utilisation o f capacity will solve the investment problem to a large extent.

Notes and References

J. e.g., private rates o f return to secondary education are 11.9 per cent in developed countries and 18.5 pCT centin developing countries. Social rates of return are respectively 9.5 and 15.2. Private rates o f return to higher education in developed countries are 11.9 and 22.0 per centin deve- lopii^ economies, and the social rates of return are 9.4 and 12.4 per cent respectively. Similarly education’s contribution to economic growth is 15.5 per cent in countries with a per capita income of US $ 180; 13.7 per cent in countries with a per capita income of US $ 500; and11.2 per cent in countries with per capita income US $ 2000 (Psacharopoulos, 1973: Pp. 67 and 117).

2. The explanation for the social rates of return to education being smaller than private rates must be found in the methodology of estimation itself. While social benefits of education are innumerable and widely diffused and spread over a long period, the only item considered is the amount o f Income tax. Almost all the studies done so far made .

only this <Tistinction. A signal exception is Blaug (1971) who has considered a variety of fringe benefits. So all the estimates of social rates of return are underestimates, see Shah (1977) and Tilak (1977a) for more reasons why investment in education is socially not profitable, while privately it is.

3. See Schultz (1962) who argues for balance between physical and human capital development.

4. For a general treatment of financial problems in education in developing economies, see Hicks (1969), Eedle (1971), Williams (1975), Meddox (1962) and Edwards (1975).

5. Pandit (1976) found that while institutional current cost in education rose from Rs. 101 crores in 1950-51 to R. 529 crores in 1965-66 a t current prices, the cost a t constant prices rose from Rs 125 crores to Rs 392 crores only during the same period.

6. Expenditure on Education

Plan NonPlan- Total

1965-66 178 259 437(40) (60) (100)

1973-74 225 1086 1311(17) (83) (100)

1977-78 324 I99I 2315(14) (86) (100)

Source: Draft Five Year Plan, 1978-83 \o \. I, Page 48.

7. For further discussion see Tilak (1977b).

8. Sometimes foregone earnings are also included in this list. Foregone earnings otherwise known as the opportunity cost is an important part of the private cost. This is an omission in our list.

9. Growth rates in this article throughout have been estimated by fittng a semi-log regression equation against time. The equation is Y = ab^ where Y is the variable o f which the growth rate is estimated, t is the time, and a and b are constants estimated by the equation while b equals to (l+(r/100)) where r is the rate of growth.

10. For a general discussion on the central-state relations with respect to education see Hartmen (1975) and Pandit (1976).

31. The coefficient is statistically significant with observed r-value equal to 2.3539, while the tabu

lated value is 1.725.12. Reference is made in the Edu

cation Commission (1966 : P 109).13. See Kamat (1978) for an excel

lent evaluation of these strategies.

14. For its merits and demerits, see Glennerster et al. (1968).

I"?. The Committee on Educational Finance (1961) discusses various ways of improving income-tax, sales tax and property tax.

■References

Adiseshaiah M. S. (1977) : “Educational Financing” , Lead Paper presented to the 7 th Commonwealth Education Conference at Accra, Ghana. (Extracts appeared in Bulletin Madras Development Seminar Series, 7/8 & 9 (Aug.- Sept.) Pp 482-92 & Pp 563-73.

Azad J. L. (1975) ; Financing o f Higher Education (New Delhi, Sterling).

Blaug, M. (1970): An Introduction to Economics o f Education (Penguin, Middlesex, 1972).

Blaug M. (1971) The Rate o f Return to Investment in Education in Thailand (National Educational Council, Bangkok) mimeo.

Carnegie Commission on Higher Education (1973) : Who PayslWho Benefits! Who should Pay? (New York, MbGraw Hill).

Committee on Educational Finance (1961) : Financing Education for Changing Population (National Education Association, Washington, DC.)

Edding, F. (1968) “International Trends in Educational Expenditures” in M. J. Bowman et al (Eds) Readings in Economics o f Education (Unesco, Paris).

Education Commission (1966) : Report o f the Education Commission: Education and National Development (Ministry of Education, New Delhi).

Edwards, E. O. (1975): “Investment ' in Education in Developing Na

tions: Conflicts among Social, Economic and Political Signals”, in J. Simmons et al. Investment in Education: National Strategy for Options for Developing Countries (IBRD, Working Paper No. 196, (February) Washii\gton DC).

Eedle, J. H. (1971) : “Financing Education in Developing Countries” Comparative Education, 111, (November), Pp. 61-68.

Galbraith, J. K. (1962) : “Education and Economic Development” in Economic Development in Pers^ pective (Harvard University Press,

Cambridge. Massachus'ets) Pp. 46-59.

Glennerster H. e t al (1968) .• “A Graduate Tax” Higher Educational Review (Autumn), Pp. 26-38.

Hartman, H. (1975) ; “Centre-State Relations in Education in India” in P. M. Dohm (Ed) Economic and Social Aspects o f Indian Development (Horst Erdman Verlag: Tubingen and Shakuntala Publishing Co., Bombay), Pp. 182-94.

Hicks U.K. (1969) ; “Educational Expansion in Low Income Countries Special Reference to India” in A. V. Bhuleshkar (Ed), Indian Economic Tfiought and Development (popular, Bombay) Pp. 368-94.

Higgins B. (1967) : “Financing Investment in Education” in Investment in Education (Unesco Regional Office for Education in Asia, Bangkok) Pp. 299-315.

Horvat B.: (1958) “The Optimum Rate of Investment” Economic Journal, 68/272 (December) Pp. IM'61,

Kamat A. R. (1978): “Financing Higher Education: A Socio-Poli- tical Analysis of the Basic ibsues” paper presented in the AlU- ICSSR National Seminar on “University and College Finance” (New Dalhi, 10-12 March 1978) mimeo.

M ^beth A. M, (1968): “Educational Finance: Some Difficulties of Comparison” Comparative Education, 4/2 (March) Pp 128-33.

Meddox J. G. (1962): “Allocating Public Expenditures for Education in UnderdevelopedCounCries” in P. D. Zook (Ed), Pp 16-25.

Misra A. (1962): Educational Finance in India (Bombay, Asia Publishing House).

Naik J. P. (1975a): Policy Performance in Indian Education (1947 74); D r K. G. Saiyidian Memo rial Lectures 1974; Orient Longman, New Delhi.

Naik J. P. (1975b)/ Elementary Education in India: A Promise to Keep; Allied Publishers, Bombay.

Nanjudappa D. M (1976): Working o f the University Finances; Sterling Publishers, New Delhi.

Pandit H. N. (1976): Investment in Indian Education: Size, Sources, and Effectiveness; IIEP, Unesco. Occasional Paper No. 43; Paris.

Peacock A. et al (1968): Educational Finance: Its Sources and Uses in the United Kingdom (Oliver & Boyd, London.

Phillips H. M. (1964): “Education and I>eveIopment” in Economic and Social Aspects o f Educational

Planning, Unesco, Paris; 15-57.Phillips H. M. (1967); “ International

Aid for Educational Development in the form of Technical assistance and Real Resources” in Investment in Education', Unesco Regional Office for Education in Asia, Bangkok; Pp 432-55.

Phillips H. M. (1975); Basic Education: A World Challenge; John Wiley and Sons, London.

Psacharopolous G. (1973): Returns to Education: An International Comparison; Elsevier Scientific Publishing Co., Amsterdam.

Schultz T.W. (1961): “Investment in Human Capita!” American Economic Review, 51/1 (March) Pp 1-17.

Schultz T. W. (1962); “ Investment in Human Capital in Poor Countries” in P. D. Zook (Ed) Pp 3-15.

Shah K. R. (1977) :“Educatioti and Economic Growth with Reference to India” Paper presented in the Workshop on “Alternative Educational Futures” ; NCERT, New Delhi; mimeo.

Smith A (1976) Wealth o f Nations; New York, Modem Library, 1987.

Streeten P (1972): “Economic Development and Education’ in his The Frontiers o f Development Studies; Macmillan, London: Pp. 129-53.

Tilak, Jandhyala B. G (1977a): “Approaches to Educational Planning and their Applications in India” ; Indian Economic Journal; 24/3 (Jan-March); Pp. 263-94. '

—(1977b) “Education in the Five Year Plans” ; Eastern Economist 68/15; (April 15); 697-703.

—(1977c) Contribution of Educa- ton to Economic Growth in India” ; Southern Economic Re- view, 6/1 (July); Pp. 45-61.

—(1978) “Regional Inequality in Literacy in India”, Indian Journal o f Adult Education 39/1 (Jan); Pp 14-22.

Vaizey J (1962); “The Role of Education in Economic Development” in H. S. Parnes (Ed) Planning Education for Economic and Social Development; OECD, Paris.

Vaizey & Sheehan (1968): Resources for Education; Alen & Uniwin, London.

Williams P: (1975) “Education in Developng Countries’; Prospects, 5/4; 457-79.

World Bank (1974): Education Sec tor Working Paper; Washington DC.

Zook P. D (1962); Edited; Foreign Trade and Human Capital; Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas.

§\

s With best compliments |§

of I

§§

§

5§§

STANDARD MOTOR PRODUCTS OF INDIA LIMITED

134, Mount Road, M ADRAS-600 002

M anufacturers o f :

* S T A N D A R D G AZEL C A R S

* S T A N D A R D -2 0 P E T R O L /D IE SE L V E H IC L E S(Delivery Vans, Utility Vans, Am bulance Vans, M inibus, Pick-up Vans, Mini Lorries)

S T A N D A R D -2 0 D IE S E L E N G IN E S(For Fitment to Standard-20 Petrol Vehicles and Jeep Vehicles)