Investigation of the Relationship Between Organizational Learning and Organizational Citizen...

Transcript of Investigation of the Relationship Between Organizational Learning and Organizational Citizen...

Safety Science 48 (2010) 1484–1489

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Safety Science

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate /ssc i

An investigation of the relationship between organizational climateand professional drivers’ driver behaviours

Bahar Öz a, Türker Özkan b, Timo Lajunen b,*

a Human Factors and Safety Behaviour Group, Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki, Finlandb Safety Research Unit, Department of Psychology, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 25 October 2007Received in revised form 15 July 2010Accepted 15 July 2010

Keywords:Professional driversDriver behavioursOrganizational cultureOrganizational climateSafety climate

0925-7535/$ - see front matter � 2010 Elsevier Ltd. Adoi:10.1016/j.ssci.2010.07.009

* Corresponding author. Tel./fax: +90 312 2103154E-mail address: [email protected] (T. Lajunen).

a b s t r a c t

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between organizational climate and driverbehaviours of professional drivers. The sample consisted of 230 male professional drivers. The partici-pants completed a questionnaire including the Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ), Hofstede’s Organi-zational Culture Scale, and a background information form. Results of the factor analysis of Hofstede’sOrganizational Culture Scale yielded two dimensions, which were named as ‘‘work orientation’’ and‘‘employee consideration’’. Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVA) revealed significant main and interactioneffects of organizational climate on errors, and violations after controlling for the statistical effects ofage, annual mileage and the organization types. Drivers with low scores of work orientation reported sig-nificantly higher frequencies of errors and violations than drivers with high scores of work orientation. Itwas also found that drivers with low scores of employee consideration reported higher frequencies oferrors and violations than drivers with high scores of employee consideration. The effect of interactionbetween work orientation and employee consideration dimensions was only found on the frequenciesof violations.

� 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In many countries, the main cause of occupational fatalities is aroad accident (Charbotel et al., 2002). Approximately 25% of thefatal work accidents in Denmark, Finland and Sweden, and nearly40% of fatal work accidents in France are road accidents (Charbotelet al., 2002). In Turkey, professional drivers were involved in morethan 30% of fatal road traffic accidents in 2009 (Trafik _IstatistikBülteni, 2009). These figures clearly show that professional driversconstitute a clear risk group in traffic.

1.1. Professional drivers

In addition to higher exposure, professional drivers in compar-ison to non-professional drivers have different demands for driv-ing. While the task demands of professional drivers are largelypre-determined, driving is a more self-paced task for non-profes-sional drivers, who can largely determine the difficulty and risk le-vel of their driving (Caird and Kline, 2004). Non-professionaldrivers can choose, for example, the mode of transportation, thetime of travel, and the target speed while driving whereas drivingis a less self-regulated task for professional drivers, because many

ll rights reserved.

.

different factors (e.g., time schedules, long working hours) increasetheir task demands. Professional drivers are also uniquely differentin another aspect: many organizational factors like a company’sculture, safety policy and practices as well as safety climate deter-mine largely how safely the individual drivers drive (Caird andKline, 2004). The role of organizational culture and/or climate inprofessional drivers’ behaviours has, on the other hand, remainedmainly unexamined.

1.2. Organizational culture and/or organizational climate

Both organizational climate and organizational culture are re-lated to the creation and influence of social context in organiza-tions (Denison, 1996), and are often used interchangeably.Organizations are complex systems having values, principles, atti-tudes and viewpoints making them different from others (Arnold,1998). Hofstede (2001) defined culture as ‘‘the collective program-ming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group orcategory of people from another (p. 1)’’ and indicated that climateand culture have some differences besides the similarities betweenthem (Hofstede, 1998); for example climate is more related to indi-viduals’ motivation and behaviour, whereas culture is entirelyplaced at the organizational level. Guldenmund (2000) discussedthe methodological differences between these two concepts; cul-ture research is based mainly on qualitative methods (e.g., field

B. Öz et al. / Safety Science 48 (2010) 1484–1489 1485

notes, quotes), whereas climate research is conducted mostly byusing quantitative methods (e.g., questionnaires) that share a lotof similarities with attitude measurements. According to Denison(1996) culture research aims at achieving a deep understandingof the underlying mechanisms whereas climate research dealswith organizational members’ perception of organizational prac-tices and how these practices and perceptions are categorized intothe analytical dimensions defined by the researchers (for more de-tailed expression of the characteristics of culture and climate con-cepts see Guldenmund (2000)).

1.3. An example: Hofstede’s investigation of organizational culture

Hofstede (1998) investigated 20 organizational units belongingto 10 different companies. After conducting in-depth interviewsand a large survey among 1295 employees, Hofstede (1998) sug-gested that an organizational culture could be described with sixdimensions. The first dimension was named, as ‘‘process orientedversus results oriented’’. Process oriented employees perceivethemselves as avoiding risks, perceive each day at work as similarto each other, and spend limited efforts on their job. Results ori-ented employees, on the other hand, perceive themselves as putt-ing the maximal effort into their jobs, feel comfortable inunfamiliar situations, and see each day as bringing new challenges.The second dimension was named as ‘‘employee oriented versusjob oriented’’. The features like employee welfare and taking otherpeople’s ideas into account are important in the employee orientedorganizations whereas job-oriented cultures focus on success, evenif the employees’ welfare has to be sacrificed. On the third dimen-sion, ‘‘parochial versus professional’’, employees feel that boththeir work and out of work behaviours are regulated by the orga-nizational norms in the parochial cultures. The social and familybackground is also seen being as important as the professionalcompetence when hiring people. In professional ones, the hiringdecision of an employee is solely based on the job competence.The fourth dimension was called ‘‘open versus closed’’. In the opencultures, both the organization and its employees are open to new-comers and outsiders, and almost anyone can fit in the organiza-tion. The fifth subdimension was named as ‘‘loose versus tight’’.In loose cultures, there are no strict meeting times, employeescan make jokes about the company, and the main focus is not onthe costs. Employees of tightly controlled units see their unit ascost-conscious and having strict meeting times, etc. The lastdimension was named as ‘‘normative versus pragmatic’’. The nor-mative culture refers to a culture in which organizational proce-dures, high standards of business ethics and honesty areemphasized. In the pragmatic units, meeting the customer needsand results rather than the procedures as well as a pragmatic atti-tude to business ethics is emphasized. The present study is, there-fore, based on Hofstede’s (1998) work in investigating the role oforganizational culture in driver behaviour.

1.4. Human factors in driving: driver behaviour

Driver performance and behaviour (Elander et al., 1993) can beseen as the two main components of human factors in driving.While driver performance is related to information processingand motor skills, driver behaviour is influenced by contextual fac-tors like motives and attitudes (Elander et al., 1993). It is hypoth-esized that, therefore, it is more likely that organizational culturewould influence more significantly driver behaviour than driverperformance.

Reason (1990) argued that driver behaviours could be classifiedby taking into account three criteria; the plan (or intention), the se-quence of the behaviours which are directed by the plan, and theextent to which these behaviours are successful in reaching the

aim. Soon after introducing the theory, Reason et al. (1990) sug-gested that the same theoretical distinction could be used whenassessing aberrant driver behaviour related to road traffic acci-dents. This differentiation provided basis for the development ofthe Manchester Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (the DBQ; Reasonet al., 1990), which was developed for measuring self-reportedaberrant driver behaviour.

In their first study about the DBQ, Reason et al. (1990) showedthat driver errors and violations are two empirically distinct clas-ses of behaviour. They defined errors as ‘the failure of planned ac-tions to achieve their intended consequences’ and violations as‘deliberate deviations from those practices believed necessary tomaintain the safe operation of a potentially hazardous system’. Un-like errors, violations were seen as deliberate behaviours, althoughboth errors and violations are potentially dangerous and could leadto a crash. Reason et al. (1990) also found a third DBQ factor, whichthey named ‘‘slips and lapses’’. This factor included attention andmemory failures, which can cause embarrassment but are unlikelyto have an impact on driving safety (Parker et al., 1995).

Since errors and violations result from different psychologicalprocesses, they should be treated differently (Reason et al.,1990). Subsequently, Lawton et al. (1997) extended the violationsscale by adding more items and splitting it into two distinctivescales according to the reasons to commit violations. Aggressiveviolations contain an interpersonally aggressive componentwhereas ‘‘ordinary’’ violations are deliberate deviations from safedriving without an aggressive content. In their recent study, Daveyet al. (2007) used the DBQ for investigating driver behaviour of 443Australian fleet drivers. Results of Davey et al.’s (2007) study re-vealed a three-factor solution including errors and two distinctiveviolation scales.

Both violations and errors were labelled as aberrant, and there-fore negative, behaviours. Focusing on negative behaviours is welljustified in terms of traffic safety. Everyday driving, on the otherhand, involves other behaviours that cannot be classified as nega-tive (Özkan and Lajunen, 2005). These behaviours do not have to bebased on coded rules and regulations, nor primarily take safety intoaccount. The main intention in these behaviours is to take care ofthe traffic environment or other road users, to help and to be politetowards them without safety concerns (Özkan and Lajunen, 2005).For example, drivers may care about the (traffic) environment (e.g.,avoid causing air pollution or congestion) or other road users (Öz-kan and Lajunen, 2005). Positive driver behaviours include bothpassive (e.g., avoid causing delays or annoyance to other drivers)and active behaviours (e.g., moving to right side of the lane to easeovertaking, thanking by hand gesture). In order to extend the DBQtowards an omnibus measure of driver behaviour, Özkan and Laj-unen (2005) added to the DBQ a scale for measuring such positivedriver behaviours.

Studies using the DBQ have shown that violations predictaccidents resulting from losing the control of the vehicle, side-impact collisions, and right-of-way accidents (Parker et al.,1995), as well as parking and speeding tickets (Mesken et al.,2002). Errors and violations could lead to accidents (Özkanet al., 2006). The lapses dimension has been reported to predictinvolvement in traffic accidents only among elderly driverswhereas slips and lapses are not critical for safety (Parkeret al., 2000). Özkan and Lajunen (2005) reported that positivedriver behaviours had a negative relationship to violations andaggressive driving.

1.5. Organizational climate and human factors

As societies do, also organizations have different cultures(Schein, 1991). In the case of organizational culture, the emphasisis on better or worse cultures, stronger or weaker cultures, and the

1486 B. Öz et al. / Safety Science 48 (2010) 1484–1489

‘‘right’’ kind of culture to end up with effective organizations(Schein, 1991). Dickson et al. (2006) emphasized the importanceof the strength of climate, which is the amount of agreementamong employees. In support of this, Schneider et al. (2002)showed that climate strength is related to some important organi-zational outcomes. Hofstede’s (1998) six organizational culturedimensions showed that besides being influenced by employees’feelings and behaviours, organizational culture practices directlyinfluence both behaviours and feelings. This was supported bysome previous studies indicating that organizational culture is re-lated to certain employee-related variables like satisfaction (Lund,2003), and commitment (Sheridan, 1992), and to organizationalperformance (e.g., Ogbonna and Harris, 2000). Similarly, Steinw-achs (1999) indicated that shared values in a group make peoplethink and act similarly and, therefore, the culture of a group im-plies the behaviours of the people of that group. Consequently, itcould be hypothesized that organizational climate would influenceprofessional drivers’ behaviours.

In the present study, therefore, the relationship between orga-nizational climate, errors, violations and positive driver behaviourswere investigated by using Hofstede’s (1998) dimensions as indi-cators of the organizational climate.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 230 professional male drivers from eight differentpublic and private organizations participated in the study. All theparticipants were contacted face to face and asked to participatein the study one by one. The total number of participants of thepresent study was obtained after having contact with a total num-ber of about 350 professional drivers. The participants were as-sured about anonymity and confidentiality. The mean age of thedrivers was 39.2 years (SD = 7.96), the average annual mileagewas 91,557 km (SD = 43,142, range = 10,000–160,000 km) and theyhad driven 17.7 years on average.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Hofstede Organizational Culture ScaleThe original scale consists of 43 items measuring six organiza-

tional culture dimensions (see Section 1.3. for the dimensions).Hofstede (1998) determined three items for each dimension asthe key indicators for that dimension. In the present study, these18 items were used for measuring the six organizational culturedimensions. The participants were asked to evaluate each itemon a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = stronglyagree).

2.2.2. Driver Behaviour Questionnaire (DBQ)To measure the violations and errors, the DBQ with extended

violations scale was used. In the present study only the violationand error scales of the DBQ were used, because the lapses arenot critical for safety and are mostly relevant only for the elderlydrivers (Parker et al., 2000). The Positive Driver Behaviours Scale(Özkan and Lajunen, 2005), which was developed to measure dri-ver behaviours conducted with positive intentions, was also usedtogether with the DBQ. The Turkish translation and the factorstructure of the DBQ have been validated in studies conductedamong both professional (Sümer and Özkan, 2002) and non-pro-fessional drivers (Sümer et al., 2002). The participants were askedto evaluate each item on a 6-point Likert type scale (1 = never,6 = always). Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency scores of thescales for the present study were as follows: 0.91 for violations

(13 items), 0.89 for errors (8 items), and 0.92 for positive behav-iours (8 items).

2.2.3. Demographic information formAge, sex, the level of education, the years a full driving license

had been held, and the annual mileage (km) were recorded.

3. Results

3.1. Factor structure of the Hofstede’s Organizational Culture Scale

Reliability analyses showed remarkably low Cronbach’s Alphafor internal consistency (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007) for the origi-nal version of Hofstede’s Organizational Culture Scale with sixdimensions (range: 0.34–0.76). One of the reasons for the low reli-ability coefficients might be the small number of items in eachdimension since the scale reliability is directly related to the num-ber of items in the scale. To compute more reliable scales, principalcomponent factor analyses were performed for the 18 items ofthese six dimensions. The number of factors was determined byusing eigenvalues, the scree plot and the parallel analysis. A factorloading value of 0.30 was determined as the cut-off score forincluding the item into the scale. As a result, a two-factor solutionwas found to be the most interpretable one. Items ‘‘comfortable inunfamiliar situation’’ and ‘‘people’s private life is their own busi-ness’’ were left out from the final solution because of their low fac-tor loadings and being conceptually irrelevant (see Table 1). Thefirst factor was named as ‘‘work orientation’’ considering the con-tent of the items in this dimension. This factor included sevenitems, and explained 25.6% of the total variance having an eigen-value of 4.61. ‘‘Work orientation’’ refers to the importance givenby the organization to the work being done, the result of the work,the working style of the employees, and the rules for doing specificwork related tasks. The second factor was named as ‘‘employeeconsideration’’. This factor included nine items, which accountedfor 9.7% of the total variance, the eigenvalue being 1.74. ‘‘Employeeconsideration’’ refers to the degree to which employees are consid-ered as individually important, are involved in decision makingprocesses and their adaptation to the organization is consideredimportant. Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliabilities forthese two scales were 0.79 and 0.68, respectively.

3.2. Correlation analyses

Before correlation analyses, the DBQ violation, error, and posi-tive driver behaviour scale scores were computed (see Table 2for descriptive scores of variables). High scores on violations, er-rors, and positive driver behaviours factors indicated high fre-quency of these behaviours. A high score on work orientationindicated high importance to work related factors; whereas lowscores indicated giving low importance to these factors. As thescores for employee orientation got higher, the employees were gi-ven more consideration for their presence and standing in theorganization; whereas low scores indicated that the employeeswere considered less within the organization.

As presented in Table 2, age was positively related to work ori-entation but negatively related to employee consideration. Annualmileage had negative relationships with violations and errorsscales of the DBQ. The two dimensions of the organizational cli-mate had a negative relationship with each other. A negative rela-tionship between work orientation and violations was found. Inaddition, work orientation had a positive relationship with positivedriver behaviours. There was a negative relationship between em-ployee consideration dimension of organizational climate anderrors.

Table 1Factor structure of the Hofstede’ Organizational culture scale.

Items Item-totalcorrelation

Factors

Factor 1(workorientation)

Factor 2(employeeconsideration)

Each day brings newchallenges (1)a

0.34 0.40

People put in maximal effort(1)

0.43 0.41

Important decisions madeby individuals (2)

0.36 0.34

Organization is onlyinterested in work peopledo (2)

0.39 0.43

Little concern for personalproblems of employees(2)

0.27 0.42

Job competence is onlycriterion in hiring people(3)

0.39 0.40

Think 3 years ahead or more(3)

0.33 0.31

Only very special people fitin organization (4)

0.40 0.46

Organization and peopleclosed and secretive (4)

0.37 0.36

New employees need morethan a year to feel athome (4)

0.45 0.54

Everybody cost-conscious(5)

0.47 0.58

Meeting times keptpunctually (5)

0.64 0.83

Always speak seriously oforganization and job (5)

0.67 0.88

Pragmatic, not dogmatic inmatters of ethics (6)

0.56 0.51

Major emphasis on meetingcustomer needs (6)

0.54 0.56

Results more importantthan procedures (6)

0.29 0.46

Comfortable in unfamiliarsituations (1)b

People’s private life is theirown business (3)b

Note: Items were sorted according to their order in the scale.a The numbers in the parentheses indicates that under which dimension of the

Hofstede’s culture scale that item is placed; 1 = process oriented versus resultsoriented; 2 = employee oriented versus job oriented; 3 = parochial versus profes-sional; 4 = open system versus closed system; 5 = loose control versus tight control;6 = normative versus pragmatic.

b Items were removed from the scale because their loadings were below the cut-off value.

B. Öz et al. / Safety Science 48 (2010) 1484–1489 1487

3.3. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)

The 2 � 2 ANCOVAs were conducted to test whether mean dif-ferences in the dependent variables (DV – errors, violations and po-sitive driver behaviours) between groups (high versus low work

Table 2Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables.

Mean SD 1

1. Age 39.19 7.72. Annual km driven 91,557 43,142 0.103. Work orientation 4.1 0.78 0.21**

4. Employee consideration 3.4 0.78 �0.23**

5. Violations 1.8 0.86 �0.116. Errors 1.6 0.80 �0.027. Positive driver behaviours 4.7 1.35 0.09

* p < .05.** p < .01.

orientation/employee consideration) are significant after removingthe effects of covariates (age, annual mileage and organizationtypes). For this purpose, three separate ANCOVAs were performed.In each ANCOVA, work orientation (low versus high) and employeeconsideration (low versus high) dimensions of organizational cli-mate were the independent variables (IVs); age, annual mileageand organization type variables were treated as the covariates. Inthe first ANCOVA analysis, error scores were entered as the DV,in the second one violation scores, and in the third one positive dri-ver behaviours scores were the DVs. Before conducting the ANCO-VAs, work orientation and employee consideration variables wererecoded into dummy variables having ‘‘low = 0’’ and ‘‘high = 1’’ val-ues, by taking the median scores of these two variables as the base.

Results of the ANCOVA analyses revealed significant main effectof work orientation on error scores F(1, 124) = 6.14, p < 0.05 andviolations scores F(1, 124) = 5.16, p < 0.05 but not for positive dri-ver behaviours. Drivers with low scores of work orientation re-ported significantly higher frequencies of errors and violationsthan drivers with high scores of work orientation. It was also foundthat drivers with low scores of employee consideration reportedhigher frequencies of errors and violations than drivers with highscores of employee consideration (see Table 3).

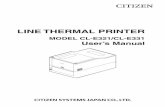

The interaction test revealed significant results for violations,F(1, 124) = 3.93, p < 0.05. It was found that the effects of work ori-entation on violation scores are different for different levels of em-ployee consideration. As it can be seen in Fig. 1, the highestfrequency for violation was reported when both work orientationand employee consideration scores are low (i.e., low organizationalimportance on the work being done, rules and regulations, etc.;and the employees are given less consideration for their presencein and adaptation to the organization, etc.). The lowest violationfrequencies were reported when both work orientation and em-ployee consideration scores are high (i.e., high organizationalimportance on the work being done, rules and regulations, etc.;and the employees are given more consideration for their presencein and adaptation to the organization, etc.).

4. Discussion

Hofstede (1998) suggested that an organizational culture couldbe described with six dimensions after the investigation of 20 orga-nizational units belonging to 10 different companies among 1295employees. However, the present study revealed a clear two-factorsolution (i.e., work orientation and employee consideration) withacceptable internal consistencies among professional drivers intransportation companies. It should be noted that 18 key items(three items per six dimensions indicated by Hofstede (1998))rather than the full scales were used in a very different sampleand organizations as compared to the original study (Hofstede,1998).

The results of the present study showed that there was a signif-icant difference between the low and high levels of work orienta-

2 3 4 5 6

0.07�0.03 �0.45**

�0.17* �0.22** �0.03�0.14* �0.10 �0.14* 0.84**

�0.13 0.17* �0.08 0.05 �0.04

Table 3ANCOVA results: mean values for the driver behaviours on organizational climatedimensions.

Workorientation

Employeeconsideration

F

Low High Low High

Errors 1.74 1.36 1.68 1.42 6.14*

Violations 1.95 1.57 1.84 1.69 5.16*

Positive driver behaviours 4.71 4.98 4.98 4.72 3.93

Note: Benferroni correction was used for pairwise comparisons.* Significant mean differences (main effects) for the work orientation dimension oforganizational climate, p < .05.

Work Orientation (WO)

High WO Low WO

Fre

quen

cy o

f V

iola

tion

s

2,20

2,00

1,80

1,60

1,40

High EC

Low EC

Employee Consideration (EC)

Fig. 1. The interaction between organizational climate dimensions (work orienta-tion and employee consideration) on violations.

1488 B. Öz et al. / Safety Science 48 (2010) 1484–1489

tion on the self-reported frequencies of errors and violations. Theresults also revealed a significant interaction effect of employeeconsideration and work orientation on the frequency of violationsafter controlling for the statistical effects of age, annual mileage,and organization types. Thus, the present study supported earlierfindings showing that organizational culture has an impact on em-ployee behaviour in general (e.g., Øgaard et al., 2005: Schein, 1984)and driver behaviours in particular.

When professional drivers perceive their work environment ascost-conscious, having clear time schedules, etc., in other words,being high in work orientation, they reported lower frequenciesof driving errors and violations. This result might indicate thatclear internal structure brings clarity in discipline, control, applica-tion of the rules, and clarity of the jobs to organizations and to pro-fessional drivers working for those organizations (see Hofstede,2001). It was also found that as the employees are less consideredwithin the organization they are working for, they reported higherfrequencies of errors and violations. ANCOVA did not, however, re-veal significant main effect for employee consideration dimensionon any of the driver behaviours. There was, on the other hand, asignificant interaction effect of work orientation and employeeconsideration dimensions on the self-reported frequencies of viola-tions of the drivers. When the drivers reported that low consider-

ation had been given for their place and presence in theorganization, and when the organizational rules, structures, regu-lations and the work being done are loosely followed, they re-ported the highest frequency of violations. When the driversreported that the style of work, rules and regulations were strictlycontrolled and they were given high consideration for their pres-ence within the organization, they reported the lowest frequencyof violations. This clearly indicates the importance of organiza-tional culture in safe driving and traffic safety. The stronger thework orientation and the employee consideration cultures whichtransportation companies establish and enforce, the less frequenterrors and violations appear to be committed.

In the former result it can be seen that a well structured worksystem encouraged the drivers to follow planned actions to achievethe intended consequences, as Reason et al. (1990) defined errors.In the latter one, it is clear that if the drivers perceive the organi-zation as ‘‘loose’’ in terms of the approach to the work being doneand lacking consideration for their personal place and value in theorganization, they tend to be involved in a higher frequency ofdeliberate deviations from the practices believed necessary tomaintain the safe operation of a potentially hazardous system, asReason et al. (1990) defined violations. These findings might be ta-ken into account by the organizations for precaution purposes. Itshould be noted that, for example, there was no significant effectof organizational climate on positive driver behaviours. It couldbe claimed that positive driver behaviours are mostly associatedwith internal factors (e.g., personality) rather than external factors(i.e., organizational climate). Organizations, therefore, might estab-lish their selection process accordingly.

Results also showed that as the professional drivers grow older,they tend to perceive their organization as more work oriented andtaking the employee related issues less into account. Such differ-ences were evidenced in some previous studies as well. Nicholaset al. (2003) showed that there are considerable differences be-tween younger and older workers in terms of their work relatedattitudes and expectations. The younger workers who are bettereducated are less committed to the management’s objectives thanthe older workers are. The findings of the present study might be asupport for the future studies to investigate the generational differ-ences on work related attitudes and matching of organizationalculture.

By investigating driver ‘‘behaviours’’ the study focused on thebehavioural side of the organizational climate. To get more de-tailed understanding, interpretations related to the organizationalculture should be done with the utmost care because behaviouraldata may not reflect underlying structures and, therefore, conclu-sions can be misleading (see Schein, 1984). In order to fully under-stand the ‘basics’ of the organizations and their effects onemployee behaviours, analyses of the values and the basic under-lying assumptions should also be conducted.

This study was aimed at investigating the relationship betweenorganizational climate and driver behaviours of professional driv-ers. In future studies, full scales of organizational culture (Hofstede,1998) could be applied to a larger sample so that the small samplesize does not restrict the comparison between different organiza-tions and organizational units. It should also be noted that theorganizational climate is only one factor among many factors hav-ing a relationship with driver behaviours of professional drivers.Job related characteristics like job satisfaction and commitmentto the job as well as traffic related variables (e.g., exposure to dif-ferent traffic conditions) might be equally or even more importantdeterminants of professional drivers’ driving than organizationalclimate. It should be noted, however, that the organizational cli-mate is a broad concept and might actually influence almost all as-pects of the work (driving in this case) in the organizationsconcerned.

B. Öz et al. / Safety Science 48 (2010) 1484–1489 1489

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by EU Marie Curie Transfer ofKnowledge Program (‘‘SAFEAST’’ Project No.: MTKD-CT-2004-509813).

References

Arnold, J., 1998. Work Psychology: Understanding Human Behaviour in theWorkplace, fourth ed. Prentice Hall, New York.

Caird, K.J., Kline, T.J., 2004. The relationships between organizational and individualvariables to on-the-job driver accidents and accident-free kilometres.Ergonomics 47, 1598–1613.

Charbotel, B., Chiron, M., Martin, J.L., Bergeret, A., 2002. Work-related road accidentsin France. European Journal of Epidemiology 17, 773–778.

Davey, J., Wishart, D., Freeman, J., Watson, B., 2007. An application of the driverbehaviour questionnaire in an Australian organizational fleet setting.Transportation Research: Part F 10, 11–22.

Denison, D.R., 1996. What is the difference between organizational culture andorganizational climate: a native’s point-of-view on a decade of paradigm wars.Academy of Management Review 21, 619–654.

Dickson, M.W., Resick, C.J., Hanges, P.J., 2006. When organizational climate isunambiguous, it is also strong. Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (2), 351–364.

Elander, J., West, R., French, D., 1993. Behavioral correlates of individual differencesin road traffic crash risk: an examination of methods and findings. PsychologicalBulletin 113, 279–294.

Guldenmund, F.W., 2000. The nature of safety culture: a review of theory andresearch. Safety Science 34, 215–257.

Hofstede, G., 1998. Identifying organizational subcultures: an empirical approach.Journal of Management Studies 35, 1–12.

Hofstede, G., 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours,Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, second ed. Sage Publications,Thousand Oaks.

Lawton, R., Parker, D., Manstead, A.S.R., Stradling, S.G., 1997. The role of affect inpredicting social behaviours: the case of road traffic violations. Journal ofApplied Psychology 27, 1258–1276.

Lund, D.B., 2003. Organizational culture and job satisfaction. Journal of Business &Industrial Marketing 18, 219–236.

Mesken, J., Lajunen, T., Summala, H., 2002. Interpersonal violations, speedingviolations and their relation to accident involvement in Finland. Ergonomics 45,469–483.

Nicholas, T., Sugur, N., Tasiran, A.C., 2003. Signs of change in Turkey’s working class:workers’ age-related perceptions in the modern manufacturing sector. BritishJournal of Sociology 54, 527–545.

Ogbonna, E., Harris, L.C., 2000. Leadership style, organizational culture andperformance: empirical evidence from UK companies. International Journal ofHuman Resource Management 11, 766–788.

Øgaard, T., Svein, L., Einar, M., 2005. Organizational culture and performance–evidence from the fast food restaurant industry. Food Service Technology, 23–24.

Özkan, T., Lajunen, T., 2005. A new addition to DBQ: positive driver behaviour scale.Transportation Research an International Journal Part F: Traffic Psychology andBehaviour 8, 355–368.

Özkan, T., Lajunen, T., Chliaoutakis, J.E., Parker, D., Summala, H., 2006. Cross-culturaldifferences in driving behaviours: a comparison of six countries. AccidentAnalysis and Prevention 38, 1011–1018.

Parker, D., West, R., Stradling, S.G., Manstead, A.S.R., 1995. Behaviouralcharacteristics and involvement in different types of traffic accident. AccidentAnalysis and Prevention 27, 571–581.

Parker, D., McDonald, L., Rabbitt, P., Sutcliffe, P., 2000. Elderly drivers and theiraccidents: the aging driver questionnaire. Accident Analysis and Prevention 32,751–759.

Reason, J.T., 1990. Human Error. Cambridge University Press, New York.Reason, J., Manstead, A., Stradling, S., Baxter, J., Campbell, K., 1990. Errors and

violations on the roads. Ergonomics 33, 1315–1332.Schein, E.H., 1984. Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. Sloan

Management Review 25, 3–16.Schein, E.H., 1991. Organizational Culture and Leadership, second ed. Jossey-Bass

Publishers, San Francisco.Sheridan, J.E., 1992. Organizational culture and employee retention. Academy of

Management Journal 35, 1036–1056.Steinwachs, K., 1999. Information and culture – the impact of national culture on

information process. Journal of Information Science 25, 193–204.Schneider, B., Salvaggio, A.N., Subirats, M., 2002. Climate strength: a new direction

for climate research. Journal of Applied Psychology 87, 220–229.Sümer, N., Özkan, T., 2002. Sürücü Davranıs�ları, Becerileri, Bazı Kis�ilik Özellikleri ve

Psikolojik Belirtilerin Trafik Kazalarındaki Rolleri. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi 17, 1–22.

Sümer, N., Lajunen, T., Özkan, T., 2002. Sürücü davranıs�larının kaza riskindekirolleri: _Ihlaller ve hatalar. Traffic and Road Safety International Congress, GaziUniversity, Ankara, Turkey, 8–12 May.

Tabachnick, B.G., Fidell, L.S., 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics, fifth ed. Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, Boston.

Trafik _Istatistik Bülteni, 2009. <http://www.egm.gov.tr/teadb/index.htm>.