Investigating relationships among festival quality, satisfaction, trust, and support: The case of an...

Transcript of Investigating relationships among festival quality, satisfaction, trust, and support: The case of an...

This article was downloaded by: [Myung Ja Kim]On: 26 February 2014, At: 17:41Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Travel & Tourism MarketingPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wttm20

Investigating Relationships Among Festival Quality,Satisfaction, Trust, and Support: The Case of anOriental Medicine FestivalHak-Jun Song, Choong-Ki Lee, Myungja Kim, Lawrence J. Bendle & Chang-Yeol ShinPublished online: 24 Feb 2014.

To cite this article: Hak-Jun Song, Choong-Ki Lee, Myungja Kim, Lawrence J. Bendle & Chang-Yeol Shin (2014) InvestigatingRelationships Among Festival Quality, Satisfaction, Trust, and Support: The Case of an Oriental Medicine Festival, Journal ofTravel & Tourism Marketing, 31:2, 211-228, DOI: 10.1080/10548408.2014.873313

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.873313

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) containedin the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make norepresentations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of theContent. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, andare not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon andshould be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable forany losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use ofthe Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematicreproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

INVESTIGATING RELATIONSHIPS AMONGFESTIVAL QUALITY, SATISFACTION, TRUST, ANDSUPPORT: THE CASE OF AN ORIENTAL MEDICINE

FESTIVALHak-Jun SongChoong-Ki LeeMyungja Kim

Lawrence J. BendleChang-Yeol Shin

ABSTRACT. This study examines the effect of a Korean Oriental medicine festival’s quality ontourists’ satisfaction, trust, and support, and explores satisfaction’s influence through the mediatingvariable of trust on destination development support, which previous festival tourism research under-reports. An onsite survey was conducted for tourists (N = 458) to the Oriental Medicine Expo. Thestructural equation model results reveal that the quality dimensions of program, facility, and conve-nience influenced satisfaction positively, and satisfaction exerted a positive significant effect on trust inthe festival’s location developing as an Oriental medicine tourism destination. Ways that Orientalmedicine tourism festivals can leverage health tourism development at regional and country levels areconsidered.

KEYWORDS. Oriental medicine festival, quality, support, trust, satisfaction

INTRODUCTION

Oriental medicine, including treatments byherbal tinctures, acupressure, acupuncture, cup-ping, dietary modification, and moxibustion, is

an accepted part of health services in East Asia.Founded in the long history of TraditionalChinese Medicine (TCM), regional variationsdeveloped as practitioners adapted to cultures,geography, epidemics, diseases, and available

Hak-Jun Song, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Hotel & Convention Management,College of Tourism & Fashion, Pai Chai University, 14 Yeon-Ja 1 Gil, Seo-gu, Daejeon 302–735, Republicof Korea (E-mail: [email protected]).

Choong-Ki Lee, PhD, is a Professor in the College of Hotel & Tourism Management at Kyung HeeUniversity, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130–701, Republic of Korea (E-mail: [email protected]).

Myungja Kim, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the College of Hotel & Tourism Management at Kyung HeeUniversity, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130–701, Republic of Korea (E-mail: [email protected]).

Lawrence J. Bendle, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the College of Hotel & Tourism Management, KyungHee University, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemoon-gu, Seoul 130–701, South Korea (E-mail: [email protected]).

Chang-Yeol Shin, PhD, is a lecturer in the Department of Tourism at Graduate School of Kyung HeeUniversity, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemoon-gu, Seoul 130–701, South Korea (E-mail: [email protected]).

Address correspondence to: Choong-Ki Lee, PhD, College of Hotel & Tourism Management, Kyung HeeUniversity, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130–701, Republic of Korea (E-mail: [email protected]).

Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31:211–228, 2014Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 1054-8408 print / 1540-7306 onlineDOI: 10.1080/10548408.2014.873313

211

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

natural herbs in China, Japan, Korea, andVietnam (Cha et al., 2007).

Today, regardless of Western medicine’s bene-fits, Oriental medicine remains important for EastAsians. For example, in China, 40% of health careuses TCM (Hesketh & Zhu, 1997), and in SouthKorea (here after Korea), spending on TraditionalKorean Medicine (TKM) exceeds about 23% ofnational medical insurance costs (Cha et al.,2007). TKM was codified in the Dongui Bogam(Mirror of Eastern Medicine) published in 1613by the royal physician Heo Jun as one of theclassics of Oriental medicine, and it is onUNESCO’s Memory of the World Program as ofJuly 2009 (Wikipedia, 2012). The East AsianDiaspora supports Oriental medicine, which theirhost countries recognize as an alternative medi-cine. Although it arises from ancient values unfa-miliar to modern science, Oriental medicine has apositive impact on Western medicine (Hesketh &Zhu, 1997). This support positions Oriental med-icine as a key determinant in the global healthtourism market; however, a country or region isyet to leverage this potential into a health tourismdestination that is recognized internationally.

One approach for expanding a health tourist’sinterest in Oriental medicine is a visit to an Orientalmedicine festival where they can access cultural,historical, and medical information and try varioustreatments. In the Republic of Korea (hereafterKorea), which has an aging population, peopleare concerned about their medical health and gen-eral wellness. So, Oriental medicine festivals are anemerging means for promoting Oriental medicine,its related industries, and destinations. For exam-ple, this paper’s focus, the “2010 World OrientalMedicine-Bio Expo,” attracted 1.3 million touristsover 31 days to Jecheon City (population of137,000), indicating it is an emerging TKM tour-ism destination. But there is a paucity of studies ontourists’ behavior associated with Oriental medi-cine. Therefore, it is important to examine theirbehavior at Orientalmedicine festivals and destina-tions. Academics and festival managers are curiousaboutwhat encourages festival tourists and satisfiesthem at a festival (Lee, Lee, & Choi, 2011). Someresearchers find that festival quality is a key factorinfluencing visitor satisfaction (Cole &Chancellor,2009; Lee, Lee, Lee, & Babin, 2007a; Lee et al.,2011b; Yoon, Lee, & Lee, 2010). In this sense, we

assume that at an Oriental medicine festival, itsquality is a required component influencing tour-ists’ satisfaction. Moreover, for an Oriental medi-cine festival location to be successful as a long-term TKM destination, support from residents(Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2012) and tourists (Lee,Bendle, Yoon, & Kim, 2012) is necessary.Research indicates that satisfaction had an effecton trust (Flavián, Guinalíu, & Gurrea, 2006;Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Kim, Chung, & Lee,2011), which influenced support for tourism devel-opment (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, 2011b; 2012).Trust also receives attention from marketing andtourism researchers as an influential predictor ofconsumer behavior (Flavián et al., 2006; Ganesan,1994; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Kim et al.,2011; Kim, Kim, & Kim, 2009; Shim, Lee, &Kim, 2008).

No research, however, reports on trust as amediating variable between satisfaction andsupport for an Oriental medicine festival devel-oping as a TKM destination. Also, the effect offestival qualities on satisfaction with anOriental medicine festival is unknown.Therefore, the purpose of this study is toexamine the effect of an Oriental medicinefestival’s quality on tourists’ satisfaction andto explore their trust as a mediator betweensatisfaction and support for the festival. Italso increases the understanding of tourists’behavior by investigating the relationshipsamong festival quality, satisfaction, trust, andsupport at a TKM Oriental medicine festival.Overall, large-scale health tourism festivals areunderresearched, as is their influence on sup-port for complementary tourism destinationdevelopment.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Health tourism and Oriental medicinetourism in Korea

Health tourism includes both illness-orientedmedical tourists and well-being achieving well-ness tourists; however, definitions and estimatesfor each vary (Bushell & Sheldon, 2009; Leggat& Kedjarune, 2009; Lunt & Carrera, 2010;Voigt et al., 2010). For example, according to

212 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

Connell (2006, p. 11), “Medical tourism is sim-ply where and when patients travel overseasoften over considerable distances, to takeadvantage of medical treatments which are notavailable or easily accessible (in terms of costsand waiting time) at home.” On the other hand,Voigt et al. (2010, p. 36) are more specific andadd three conditions. First, that these tripsshould incorporate usual tourism or vacationcomponents. Second, that medical tourismincludes essential procedures like cardiac sur-gery, organ transplants, and cancer treatments,and elective procedures like diagnostics, cos-metic changes, and reproduction assistance.Third, the typical pull factors that attract medi-cal tourists are cost savings, quality standards,availability of drugs and surgery methods,anonymity and privacy, cultural affinity, andgeographical proximity (Voigt et al., 2010,p. 40).

For clarity, given the changing definitions forhealth, medical, and wellness tourism, thispaper applies the following definitions recentlydeveloped for the global spa industry (GlobalSpa Summit, 2011, p. 20):

Medical tourism involves people who travelto a different place to receive treatment for adisease, an ailment, or a condition, or toundergo a cosmetic procedure, and who areseeking lower cost of care, higher quality ofcare, better access to care or different carethan what they could receive at home.Wellness tourism involves people who travelto a different place to proactively pursueactivities that maintain or enhance their per-sonal health and wellbeing, and who areseeking unique, authentic, or location-basedexperiences/therapies not available at home.

As it offers treatments for illness and forimprovements to personal well-being (Baker,2003), Oriental medicine attracts tourists fromboth the medical tourism and wellness tourismsectors and draws on growing interest and rev-enue from both. Hence, it is a health tourismtype with links to hospital and clinic-based ill-ness treatments and to spa-based wellnesstreatments.

Estimates of medical and wellness tourismglobal revenues vary because the inconsistentreporting standards between countries make col-lecting tourist numbers or dollar values impre-cise. For instance, in 2008 McKinsey estimatedglobal medical tourist numbers at as low as60,000 to 85,000 yearly, but Youngman (2009)asserts that these used restrictive definitionsbased on inpatient numbers only. He arguesthat by using conservative estimates from coun-tries with reliable inpatient and day-patient sta-tistics, the global figures should be between 5 to6 million medical tourists yearly. Heung,Kucukusta, and Song (2011, p. 2) estimated glo-bal turnover at US$60 billion and predicted rev-enue in India, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand,and Korea at US$4 billion by 2012. By compar-ison, the spa industry values the nine sectors ofthe global wellness industry cluster at US$2trillion approximately. It also estimated the med-ical tourism sector and the wellness tourism sec-tor at US$50 billion and US$106 billion,respectively (Global Spa Summit, 2010, p. 24).There is general agreement, nonetheless, thatAsia is the global center for medical tourism,with India, Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysiarecognized for their successful medical tourismsectors, which Hong Kong and Korea are striv-ing to follow. Although Hong Kong has first-ratehealth care and a positive reputation for bothcancer care and traditional Chinese medicine,its development in the medical tourism sectorlacks effective coordination (Heung et al., 2011).

Since 2009, however, the Korean govern-ment’s health and tourism ministries have coor-dinated their actions for promoting medicaltourism including visa requirements, insuranceand financial transactions, hospital certification,and overseas marketing (Korea.net, 2011). Theministry estimates that more than 110,000 non-Koreans would spend approximately US$700million on hospital treatments, including out-patient, inpatient, and check-up procedures by2015 (Kim, 2011). The ministry also promotesTKM for improving peoples’ health and fornational competiveness by implementing threepolicy objectives. These include: (1) the stan-dardizing of TKM services and their scientificbasis, (2) ensuring the safety and efficacy of

Song et al. 213

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

herbal medicines, and (3) implementing suppor-tive infrastructure, research, and tourism initia-tives (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2011).The tourism initiatives focus on setting up TKMtourist towns at locations including Jeju Islandoff the Korean Peninsula’s southern tip,Gyeongbuk province in the Peninsula’s center,and at Jecheon, near Seoul.

The Jeju provincial government is boostingthe Island’s stagnant tourism industry by expand-ing well-being and medical services, includingOriental medicine, and targeting the nearbyChinese, Japanese, and Korean tourism markets(Yu & Ko, 2012). According to a survey(n = 1,100) commissioned by the Gyeongbukgovernment, 49.4% of respondents said theywould use a TKM tourist resort when it devel-oped in the province (Yu, 2009). Another studyof TKM tourism potential for GyeongbukProvince (Lee, Yu, & Yim, 2009) estimateddemand at 10 million domestic tourists andemployment impact of approximately 68,000jobs nationally. As the Jecheon city governmenthad promoted its location as a TKM industrycluster combining herb production, researchand development, treatment facilities, and touristamenities, it held “The 2010 World OrientalMedicine-Bio Expo” (the Expo hereafter). TheExpo offered educational, industrial, and inter-national exhibits; trade, investment, and productstands; performances and events; direct experi-ences of TKM efficacy for all ages; conferences,seminars, and forums; and TKM themed recrea-tional spaces (Jecheon City, 2011). Given thehigh number of tourists who visited the Expo,understanding their support for Jecheon’s devel-opment as a TKM tourism destination is impor-tant in assisting the city government, local TKMbusinesses, and residents in evaluating potentialdemand for TKM tourism. Thus, the Expo tour-ists’ experience of festival quality,satisfaction, trust, and support was investigatedaccordingly.

Concept of festival quality

Quality can be defined as a consumer’s judg-ment about excellence of a product or service(Zeithaml, 1988, p. 3). Parasuraman, Zeithaml,

and Berry (1988) define service quality asSERVQUAL, which comprises five compo-nents, such as tangibles, reliability, responsive-ness, assurance, and empathy. Service quality isan attitude related to but not equivalent withsatisfaction that arises by comparing expecta-tions with reality (Parasuraman et al., 1988).Delivering service quality is an essential strat-egy for business success and survival (Cronin &Taylor, 1992). Furthermore, marketing literatureindicates that service quality is associated withconsumer’s satisfaction and behavioral intention(Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Marinova, Ye, &Singh, 2008; Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman,1996). That is, service quality is a positiveantecedent of consumer satisfaction that signifi-cantly influences purchase intentions (Cronin &Taylor, 1992).

Festivals and events contribute to tourismand offer economic benefits to their host region(Lamberti, Noci, Guo, & Zhu, 2011; Lee &Taylor, 2005). To take advantage of these ben-efits, some local governments host festivals topromote their regional cultures and economies(Lee et al., 2007a; Yoon et al., 2010). Festivalquality is a perceived concept that is associatedwith satisfaction (Lee, Petrick, & Crompton,2007b) and provides successful tourist experi-ences (Crompton & Love, 1995). It plays a keyrole in influencing tourists’ satisfaction andbehavioral intention (Lee et al., 2007a; 2011;Yoon et al., 2010). In this respect, festival qual-ity has been explored at various festivals (Cole& Chancellor, 2009; Crompton & Love, 1995;Lee et al., 2007a; 2007b; Lee et al., 2011; Yoonet al., 2010; Yuan & Jang, 2008). Cole andChancellor (2009) suggest festival qualitydimensions that included programs, amenities,and entertainment, whereas Lee et al. (2007a)proposed festival quality in terms of festivals-capes containing convenience, staff, informa-tion, program content, venue, souvenirs, andfood. Furthermore, Lee et al. (2007b) generatedfour dimensions of service quality, such as gen-eric features, specific entertainment features,information sources, and comfort amenities.Yoon et al. (2010) proposed five festival qualitydimensions, including informational service,program, souvenirs, food, and facility. And ata wine festival, Yuan and Jang (2008) identified

214 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

festival quality as facilities (e.g., live music,knowledgeable staff, convenient parking), winechoice (e.g., multiple wines, wineries), andorganization (e.g., superior management, rea-sonable pricing). Based on the literature review,this research developed four quality dimensionsfor use at the Oriental medicine Expo. Thesewere program (Cole & Chancellor, 2009; Yoonet al., 2010), hospitality (Cole & Chancellor,2009; Lee et al., 2007b), venue (Lee et al.,2007a; Yuan & Jang, 2008), and convenience(Lee et al., 2007a; Yuan & Jang, 2008).

Concept of satisfaction and therelationship between festival quality andsatisfaction

Comparing expectations with reality candetermine satisfaction (Parasuraman et al.,1988), and disconfirmation of expectation the-ory indicates consumers are satisfied if a pro-duct’s performance is higher than theirexpectations; it indicates consumers are dissa-tisfied when its performance is lower (Oliver,1980). Higher satisfaction is important becauseit builds long-term client interaction and winsrepeat business (Lee et al., 2007a).

Festival literature shows a positive relation-ship between festival quality and satisfaction(Cole & Chancellor, 2009; Lee et al., 2007a;2011; Loureiro & Gonzalez, 2008; Yoon et al.,2010; Yuan & Jang, 2008). For instance, Leeet al. (2007a) developed festival quality in termsof festivalscapes at the International AndongMask Dance Festival and examined the relation-ship between festival quality and satisfaction.Their results indicate that quality dimensionsof program content, facility, and food had asignificant effect on tourists’ satisfaction. Yuanand Jang (2008) find that the perception offestival quality had positive significant effecton satisfaction directly at a wine festival, sug-gesting that festival quality is an important ante-cedent of customer satisfaction. Cole andChancellor (2009) investigated the relationshipbetween festival quality and satisfaction. Theirresults reveal that festival entertainment qualitystrongly influenced tourists’ overall satisfaction.Loureiro and Gonzalez (2008) also report that

perceived service quality had positive signifi-cant effect on tourists’ satisfaction, indicatingthat service quality is a powerful antecedent ofsatisfaction. Yoon et al. (2010) found that thefestival quality dimensions of program, souve-nir, food, and facility had positive and signifi-cant effect on tourists’ satisfaction through themediating variable of festival value at thePunggi Ginseng Festival. Similar results werefound by Lee et al. (2011) in that the festivalquality dimensions of program, convenientfacility, and natural environment affected tour-ists’ satisfaction through the mediator of festivalvalues at the Boryeong Mud Festival in Korea.

This analysis of festival literature indicatesthat festival quality is an important antecedentof tourists’ satisfaction. Therefore, it is proposedthat the Oriental medicine Expo’s qualitydimensions of program, hospitality, venue, andconvenience are positively associated with tour-ists’ satisfaction as follows:

H1: Program quality of the Oriental medi-cine Expo influences tourists’ satisfac-tion positively.

H2: Hospitality quality of the Oriental med-icine Expo influences tourists’ satisfac-tion positively.

H3: Venue quality of the Oriental medicineExpo influences tourists’ satisfactionpositively.

H4: Convenience quality of the Orientalmedicine Expo influences tourists’ satis-faction positively.

Concept of trust and the relationshipbetween satisfaction and trust

Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23) define trust as“existing when one party has confidence in anexchange partner’s reliability and integrity.” Asimilar definition is made by Moorman,Zaltman, and Deshpande (1992, p. 315) in thattrust means “a willingness to rely on an exchangepartner in whom one has confidence.” In theindustrial buying context, Doney and Cannon(1997, p. 36) define trust as “the perceived

Song et al. 215

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

credibility and benevolence of a target of trust.”Trust is critical in helping exchange relationships(Moorman, Deshpande, & Zaltman, 1993), differ-entiating between effective and ineffective salesrelationships (Smith & Barclay, 1997), and meet-ing consumers’ expectation (Sirdeshmukh, Singh,& Sabol, 2002). The literature implies that trust istourists’ confidence in a festival on the conditionthat they are satisfied with it and a willingness tosupport it by keeping good relations betweenguests and hosts.

Roman (2003) asserts that the more a customeris satisfied with a company the more he trusts thecompany, indicating the effect of customer satis-faction on trust. Loureiro andGonzalez (2008)findthat tourists’ satisfaction had a positive effect ontheir trust in the area of rural tourism. Garbarinoand Johnson (1999) reveal that overall satisfactionhad significantly positive effect on trust for indivi-dual ticket buyers and occasional subscribers. Inthe context of Web site and online shopping,Flavián et al. (2006) report that user trust wasdependent on the level of consumer satisfaction.Kim et al. (2011) suggest that satisfaction signifi-cantly and positively influenced trust in onlinetourism shopping. In the investment situation,Shim et al. (2008) indicate that satisfaction had apositive effect on trust and patient satisfactionpositively and significantly affected patient trustin the medical area (Suki, 2011). In the hotelindustry, Kim et al. (2009) report that trust’s med-itating role was substantial between recovery satis-faction and revisit intention. Review of theliterature indicates that consumer satisfactionrelates positively to their trust in the service provi-ders. Therefore, this study posits that tourists’satisfaction is an antecedent of their trust in theOriental medicine Expo as follows:

H5: Satisfaction with the Oriental medicineExpo influences trust positively.

Concept of support and the relationshipbetween trust and support

Support can be defined as “a future orienta-tion towards action by behaviorally acting in a

way that provides additional backing to thesupported cause” (Lusch, O‘Brien, & Sindhav,2003, p. 250). Social Exchange Theory could bean appropriate framework of predicting supportfor tourism development, such as the Orientalmedicine Expo in this study (Ap, 1992). TheSocial Exchange Theory as a behavioral theoryindicates that those who perceive their benefitfrom tourism development are more likely toexpress positive attitudes toward and supportfor tourism development (Ap, 1990). Based onthe Social Exchange Theory, Lee and Back(2006) reveal that residents who perceived ben-efits from casino development were more likelyto support for it. Community support is centralfor local governments, policy makers, and orga-nizers when proposing new events (Gursoy &Kendall, 2006).

Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (2012) noted thedirect positive relationship between residents’support for tourism and their trust in govern-ment agencies. Rudolph (2009) suggests thatpolitical trust is an instrumental resource thatcan bolster public support for a conservativeas well as a liberal policy agenda. Lusch et al.(2003) show that retailers’ trust was an impor-tant determinant of their support for the merger,whereas Nunkoo and Ramkissoon (2011a)asserted indirect relationships between satisfac-tion and support via the mediator of perceivedimpacts. Trust is an essential element in influen-cing and understanding exchanges between resi-dents and the tourism industry when receivingsupport for tourism development (Nunkoo &Ramkissoon, 2011b). Lee et al. (2011) findthat resort tourists who had recommendationand revisit intentions for a destination througha mediating variable of satisfaction alsoexpressed their support for the destinationdevelopment.

The literature implies that trust is a prerequi-site in extracting support for tourism develop-ment (Doney & Cannon, 1997; Moorman et al.,1992; Morgan & Hunt, 1994) and indicates thattrust is a mediating variable between satisfac-tion and support. Moreover, Shonk and Bravo(2010) suggest that the level of support forsporting events was influenced by trust of indi-vidual and organizational levels. Therefore, it isexpected that tourists’ trust in the Oriental

216 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

medicine Expo contributes to their support forthe destination’s Oriental medicine tourismdevelopment as follows:

H6: Trust in the Oriental medicine Expoinfluences support for Jecheon’s devel-opment as an Oriental medicine tourismdestination positively.

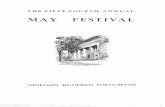

Based on the six hypotheses, a research modelwas proposed to investigate the relationshipsamong quality, satisfaction, trust, and supportat the Oriental medicine Expo (see Figure 1).

METHOD

Study site

In Korea, various festivals are held in 16metro-politan cities and provinces. These festivals rangefrom small-scale regional events (e.g., traditionalmusic festival, food festival) to large-scale inter-national festivals, such as a Mud festival (Leeet al., 2011), a Mask Dance festival (Lee et al.,2007a), and a Ginseng festival (Yoon et al., 2010).Oriental medicine festivals are an emerging touristattraction, but there is a paucity of studies thatcontribute to the understanding of visitors’

behavior at them. Thus, this study selected the“2010 World Oriental Medicine-Bio Expo,”which was the largest in a series of Oriental med-icine festivals initiated by the national and localgovernments for the promotion of TKM, as itsstudy site. Jecheon is a leading Oriental medicinecluster in Korea, and with the national govern-ment’s support, it hosted the Expo, whichattracted 1.3 million tourists during the periodSeptember 16 to October 16, 2010 (JecheonCity, 2011). The Expo calendar included officialceremonies, exhibitions, experiential events, con-ferences, and entertainment. Official ceremoniesincluded “Beginning of Korea fostering tradi-tional Oriental medicine,” “The 31 day journeyand story of traditional Oriental medicine,” and“A leap into the future for traditional Orientalmedicine.” Exhibitions at the future Oriental med-icine pavilion, the medicinal herb pavilion, andthe TKM industry pavilion were themed aroundOriental medicine in the age of well-being. Thiscovered aging and diseases, Oriental medicineand health, Oriental medicine therapy experi-ences, the future of Oriental medicine, and newworlds of health, medicine, and well-being.Experiential events included traditional Orientalmedicine activities for various age groups, tradi-tional Oriental medicine soap manufacturing, andmedicinal tea making. Also provided were alter-native health training, including a special stone

FIGURE 1. A Proposed Research Model

Song et al. 217

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

meditation method and massage classes for cou-ples. Conferences included a 2010 internationalsymposium of integrative oncology and new erafor cancer treatment sponsored by the Associationof Korea Oriental Medicine. Other popular Expoevents were historical pageants, dance perfor-mances, musical concerts, fireworks displays,and a follow-up culture festival.

Measures

This research adopted multi-measurementitems for each construct to overcome measure-ment errors associated with single items(Churchill, 1979). First, measurement itemswere generated after a comprehensive review ofthe literature on festival tourists’ behavior. Theseincluded festival quality, satisfaction, trust, andsupport (Crompton & Love, 1995; Ganesan,1994; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Gursoy &Kendall, 2006; Lee et al., 2007a, 2007b; Leeet al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Nunkoo &Ramsissoon, 2011b; Yoon et al., 2010; Yuan &Jang, 2008). Second, some measurement itemsassociated with the Oriental medicine Expo weregenerated from Jecheon’s Oriental medicineExpo policy and programs. These were“Holding the Expo improved Jecheon’s brandimage for Oriental medicine treatment and tour-ism destination” and “I support Jecheon’s effortsin promoting and globalizing Oriental medi-cine.” Third, researchers visited the Expo andinterviewed several Expo managers. Finally,researchers evaluated which measurement itemsfrom the literature reviewed could be includedand which items should be added so that themeasurement items could reflect the Orientalmedicine Expo context. Once the list of measure-ment items was selected, some modificationswere implemented to measure the generic natureof the Oriental medicine Expo. These measure-ment items in the survey questionnaire weredeveloped in English and translated intoKorean by the researchers. It was translatedback to English by experts proficient in Englishand Korean to verify its accuracy. The versionswere compared and discrepancies corrected. Theresearchers ensured consistency between theKorean and the English surveys by this process.

Content validity of the preliminarymeasurementitems was then evaluated by three academics in thearea of festival research and one festival manager atthe Oriental medicine Expo. These four expertschecked if these items were appropriate for asses-sing the measurement items for the Oriental medi-cine Expo. Furthermore, a pretest was alsoconducted with 10 festival attendees who had vis-ited the festival andfive graduate studentsmajoringin tourism management. Based on these experts’comments and the results of the pretest, the surveyinstrument was reworded to clarify some ambigu-ous items, and inappropriate items were removed.The validity and reliability of the survey instrumentwere tested using confirmatory factor analysis andCronbach’s alpha, respectively.

Based on previous research and interviews, thefestival quality variable was operationalized with17 items suggested by previous research(Crompton & Love, 1995; Lee et al., 2007a,2007b; Lee et al. 2011; Yoon et al., 2010; Yuan& Jang, 2008). For instance, these items include“Offering a variety of activities and events,”“Reliable progress of the Expo schedule,”“Providing Oriental medicine-related programs,”“Kindness of operating agents and volunteers,”“Usefulness of the Expo brochure,” “The atmo-sphere of venues,” “Convenient public transporta-tion from a point of departure to the Expo,” and“Convenience in using Expo car parking facil-ities.” The satisfaction variable was operationa-lized with three items from previous research (Leeet al., 2007a; Yoon et al., 2010; Yuan & Jang,2008). These items include “I am satisfied withmy decision to visit the Expo,” “My feelings aregood about the Expo,” and “I am satisfied with themanagement and schedules at the Expo.” Thetrust variable was operationalized with five itemsbased on past research (Ganesan, 1994; Garbarino& Johnson, 1999). These items include “Jecheongained my confidence as a region for Orientalmedicine treatment and a tourism destination byholding the Expo” and “Holding the Expo inJecheon met my expectations of it as a regionfor Oriental medicine treatment and as a tourismdestination.” The support variable was operatio-nalized with four items suggested by past research(Gursoy & Kendall, 2006; Lee et al., 2012;Nunkoo & Ramsissoon, 2011b). These itemsinclude “I support Jecheon’s tourism development

218 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

for Oriental medicine,” “It is desirable thatJecheon should develop as an Oriental medicinetourism destination,” and “I support Jecheon’sefforts in promoting and globalizing Orientalmedicine.” All items were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale with: 1 = strongly disagree,3 = neutral, and 5 = strongly agree.

Data collection

The Expo attracted 1,360,218 people including1,309,321 domestic tourists (96.3%) and 50,897foreign tourists (3.7%) (Organizing Committee ofthe 2010 World Oriental Medicine-Bio Expo,2011). Since a majority of tourists to the Expowere domestic tourists, who are also the primarymarket for Jecheon’s TKM tourism, they were thetarget population of this study.

An onsite intercept survey at the Expo wasconducted for individual domestic tourists by10 field researchers who were trained in theresearch project purpose and its samplingmethod. Sample data were collected in termsof time frame, location, and sampling intervalto obtain a representative sample, as follows.The survey occurred over 10 days fromOctober 1 to 10, 2010 including both weekdaysand weekends. It was conducted between 2 p.m.and closing time at 6 p.m. because it took aboutfour hours to tour the Expo. Also, the fieldresearchers solicited survey participants fromevery fifth tourist at three locations: the maingate, high traffic exhibition areas, and theexperiential program areas.

After checking that tourists had time toexperience exhibition and experiential pro-grams, the field researchers outlined theresearch purpose and invited them to participatein the survey. Following their consent, a self-administered questionnaire was provided tothose who preferred to complete it themselves,or the field researchers helped them completethe questionnaire by a personal interview.Reading glasses were available, and sweetswere offered as some respondents were tiredfrom their Expo tour. The field researchers dis-tributed 600 questionnaires, and 475 question-naires were collected, giving a response rate of79.2%. During the data refinement process, 17

questionnaires were eliminated because ofincomplete answers, and 458 questionnaireswere finally coded for analysis.

In terms of respondents’ profiles, there weremore females (58.0%) than males (42.0%) andmore married (70.4%) than single (28.3%)respondents. Ages 50–59 years were the largestproportion at 24.1%, followed by 20–29 years(22.1%), 40–49 years (17.3%), over 60 years(16.7%), 30–39 years (14.0%), and 10–19 years(5.7%); 63.6% of respondents had two-year col-lege or higher degree holders. Monthly incomelevel of respondents was 2–3.9 million Koreanwon (30.3%), followed by less than 1 millionwon (27.9%), 1–1.9 million won (21.3%), 4–5.9 million won (14.1%), and over 6 millionwon (6.4%)—where US$1 equals 1,145 won.Moreover, their primary purpose for visitingJecheon was for the Expo (90.2%). First-timevisits accounted for 61.8% and more than twotimes accounted for 38.2%. A majority (67.9%)had experienced TKM treatment before. Theyexpressed the reasons to use an Oriental medicinehospital or clinic as excellent cure for diseases(32.0%), restorative for a weak constitution(26.3%), suitable for their constitution (22.1%),no benefits from Western medicine (9.1%), andothers (10.5%). Their satisfaction levels withTKM treatment were satisfied (45.5%), neutral(35.8%), dissatisfied (8.5%), strongly satisfied(8.0%), and strongly dissatisfied (2.3%).

Data analysis

To test hypotheses shown in Figure 1, astructural equation modeling (SEM) approachwas used for evaluating how the proposedmodel or hypothetical construct explains thecollected data (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson,& Tatham, 2006). Because it considers collecteddata were of multivariate non-normally distribu-tion (Byrne, 2006), the robust maximum like-lihood method was utilized as an estimationmethod for model evaluation and procedures.Exploratory factor analysis identified the struc-ture of factors and systematically measuredvariables in underlying constructs as a firststep in evaluating the measurement model,which reduced significant cross-loadings and

Song et al. 219

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

multicollinearity among indicators (Bollen,1989; Hair et al., 2006). By specifying a mea-surement model in the confirmatory factor ana-lysis and testing a latent structural modeldeveloped from the measurement model, theSEM of current study followed a two-stepapproach (Anderson & Gerbing, 1992). Thedata were analyzed with the Statistical Packagefor the Social Sciences and EQS StructuralEquation Modelling Software.

RESULTS

Measurement model

This study employed Mardia’s standardizedcoefficient to confirm if the data violate assump-tion of multivariate normality. Because Mardia’sstandardized coefficient for the measurementmodel (46.87) is greater than the criterion of 5(Byrne, 2006), the data were considered to bemultivariate non-normally distributed. Therefore,the robust maximum likelihood method, whichapplies when assuming multivariate normalityfor collected data is not satisfied, was used toestimate structural equation modeling. Bentlerand Wu (1995) and Byrne (2006) state thatSatorra-Bentler (S-B) Chi-square provided in therobust maximum likelihood method providesvalid standard errors and other fit indices, whenthe data violates the multivariate normalityassumption.

To build a final measurement model, twoitems were dropped because of significantcross-loadings and multicollinearity among indi-cators during the exploratory factor analysis. Thefinal measurement model was derived from theconfirmatory factor analysis, and Table 1 pre-sents a satisfactory fit on all goodness-of-fitindices. This finding confirms that the proposedmeasurement model does fit the data well:χ2 = 586.544, S-B χ2 = 478.731, df = 300; non-normal fit index (NFI) = 0.931; nonnormed fitindex (NNFI) = 0.968; comparative fit index(CFI) = 0.973; and root mean square error ofapproximation (RMSEA) = 0.036. Table 1shows the Cronbach’s alpha values produced bythe CFA in estimating the reliability of the

multi-item scales: program quality (0.852), hos-pitality quality (0.876), venue quality (0.855),convenience quality (0.864), satisfaction(0.902), trust (0.906), and support (0.913). Allalpha coefficients were above the cut-off point of0.7 (Nunnally, 1978), indicating acceptable relia-bility for each construct.

Convergent and discriminant validity statisticsare also as depicted in Table 2. All average var-iance extracted (AVE) and composite reliabilityvalues for the multi-item scales were greater thanthe minimum criterion of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively(Hair et al., 2006) and indicated a sufficient con-vergent validity for the measurement model. Tocheck discriminant validity of the constructs, threemethods were used. The first method using AVEdid not confirm discriminant validity, as the high-est squared correlation between satisfaction andtrust (0.769) was greater than the AVE for corre-sponding inter-constructs (Satisfaction = 0.757,Trust = 0.724) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).However, the other two methods, which usedconfidence intervals and constrained models, sup-ported the discriminant validity levels.Specifically, the confidence interval of correlationbetween festival satisfaction and trust (0.961,0.793), plus or minus two standard errors of cor-relation between the constructs, did not includethe criterion of 1.0, based on a confidence intervalmethod (Anderson & Gerbing, 1992). Also, dis-criminant validity using a constrained model wasconfirmed because the S-B Chi-square differencetest statistic for the relationship between satisfac-tion and trust (36.66) exceeded the criterionof 3.84 (p < 0.001) (Bagozzi & Phillips, 1982;Steenkamp & Trijp, 1991).

Hypothesis testing

Figure 2 summarizes the results of the pro-posed research model in this study. The resultsof the structural model confirmed that the pro-posed structural model does fit the data ade-quately; S-B χ2 = 499.211, df = 309;NFI = 0.928; NNFI = 0.967; CFI = 0.971; andRMSEA = 0.037. The explained variances ofendogenous constructs were 45.9% for satisfac-tion, 78.9% for trust, and 38.1% for support,

220 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

TABLE

1.Con

firm

atoryFac

torAna

lysisan

dGoo

dnes

s-of-fitIndice

sforMea

suremen

tMod

elRes

ults

Con

structs

Fac

torload

ing

t-va

lue

Cronb

ach’salph

a

Fac

tor1:

Program

0.85

2Offe

ringava

riety

ofac

tivities

andev

ents

0.72

516

.160

Reliableprog

ress

oftheExp

osc

hedu

le0.68

815

.692

Providing

exhibitio

nan

dpe

rforman

ceva

riety

0.76

120

.576

Providing

Orie

ntal

med

icine-relatedprog

rams

0.81

019

.277

Fac

tor2:

Hosp

itality

0.87

6Kindn

essof

operatingag

ents

andvo

luntee

rs0.75

217

.455

Polite

ness

ofop

eratingag

ents

andvo

luntee

rs0.71

917

.456

Prope

rnu

mbe

rsof

operatingag

ents

andvo

luntee

rs0.78

921

.270

Use

fulnes

sof

theExp

obroc

hure

0.74

418

.858

Fac

tor3:

Ven

ue

0.85

5Ven

ues’

facilities

0.73

518

.953

Spa

cean

dsize

ofve

nues

0.74

419

.102

Clean

lines

sof

thefacilitiesin

venu

es0.75

518

.803

The

atmos

phereof

venu

es0.71

220

.079

Fac

tor4:

Conve

nience

0.86

4Con

venien

tpu

blic

tran

sportatio

nfrom

apo

intof

depa

rtureto

theExp

o0.74

716

.793

Acc

essibilityfrom

Exp

oarea

toothe

rve

nues

0.77

718

.520

Eas

eof

find

ingtheve

nues

0.90

224

.295

Con

venien

cein

usingExp

oca

rpa

rkingfacilities

0.75

716

.582

Fac

tor5:

Satisfaction

0.90

2Iam

satisfied

with

myde

cision

tovisittheExp

o0.79

820

.529

Myfeelings

arego

odab

outtheExp

o0.81

122

.586

Iam

satisfied

with

theman

agem

entan

dsc

hedu

lesat

theExp

o0.74

519

.132

Fac

tor6:

Trust

0.90

6Je

cheo

nga

ined

myco

nfide

nceas

aregion

forOrie

ntal

med

icinetrea

tmen

tan

datourism

destinationby

holding

theExp

o0.71

719

.676

0.71

819

.955

Holding

theExp

oim

prov

edJe

cheo

n’sbran

dim

ageforOrie

ntal

med

icinetrea

tmen

tan

dtourism

destination

0.72

520

.736

0.78

621

.787

Holding

theExp

ostreng

then

edmybe

liefin

Jech

eonas

aregion

forOrie

ntal

med

icinetrea

tmen

tan

dtourism

destination

Holding

theExp

oin

Jech

eonmet

myex

pectations

ofitas

aregion

forOrie

ntal

med

icinetrea

tmen

tan

das

atourism

destination

Fac

tor7:

Support

0.91

3Isu

pportJe

cheo

n’stourism

deve

lopm

entforOrie

ntal

med

icine

0.79

420

.676

Itis

desirablethat

Jech

eonde

velopas

aOrie

ntal

med

icinetourism

destination

0.73

520

.445

Jech

eon’sOrie

ntal

med

icinetourism

willas

sist

region

alde

velopm

ent

0.71

217

.837

Isu

pportJe

cheo

n’seffortsin

prom

otingan

dglob

alizingOrie

ntal

med

icine

0.70

216

.938

Mea

suremen

tmod

elχ2

S-B

χ2df

Normed

S-B

χ2NFI

NNFI

CFI

RMSEA

586.54

447

8.73

130

01.59

60.93

10.96

80.97

30.03

6Sug

gested

value*

≤3

≥0.9

≥0.9

≥0.9

≤0.08

Note.

Allstan

dardized

factor

load

ings

aresign

ifica

ntat

p<0.00

1.Twoite

msweredrop

ped:

onewas

relatedto

venu

efactor

(“The

lay-ou

tofv

enue

s”)an

dtheothe

rwas

relatedto

trus

tfac

tor(“IwillvisitO

riental

med

icinerelatedtourism

destination

ofJe

cheo

n”).

221

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

respectively. Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4 posited thatfour festival qualities have positive influence onfestival satisfaction. Three predictor variables(βProgram →Satisfaction = 0.482, t = 5.859, p < 0.01;βVenue→Satisfaction = 0.164, t = 2.082, p < 0.05;βConvenience→Satisfaction = 0.185, t = 3.194, p < 0.01)

exerted a positive impact on festival satisfaction.Thus, H1, H3, and H4 were supported. Hospitality(βHospitality→Satisfaction = 0.038, t = 0.505), how-ever, was not statistically significant in predictingfestival satisfaction, rejecting H2. The results ofhypothesis testing indicate that satisfaction

TABLE 2. Reliability and Validity for Measurement Model

Constructs Program Hospitality Venue Convenience Satisfaction Trust Support

Program 1.000Hospitality 0.588 1.000

(0.346)Venue 0.630 0.670 1.000

(0.397) (0.449)Convenience 0.341 0.407 0.545 1.000

(0.116) (0.166) (0.297)Satisfaction 0.609 0.462 0.543 0.430 1.000

(0.371) (0.213) (0.295) (0.185)Trust 0.584 0.461 0.553 0.399 0.877* 1.000

(0.341) (0.213) (0.306) (0.159) (0.769)Support 0.340 0.392 0.327 0.278 0.577 0.610 1.000

(0.116) (0.154) (0.107) (0.077) (0.333) (0.372)CR 0.856 0.860 0.855 0.866 0.903 0.913 0.907AVE 0.597 0.606 0.596 0.620 0.757 0.724 0.710

Note. * Pairs of constructs having highest correlations. The numbers in the parenthesis indicate squared correlation amonglatent constructs. All correlations are significant at p < 0.01. Correlation coefficients are estimates from EQS. CR = compositereliability; AVE = average variance extracted.

FIGURE 2. Results of Proposed Research Model

222 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

affected trust positively (βSatisfaction→Trust = 0.888,t = 18.407, p < 0.01), supporting H5. The relation-ship between trust and support for Jecheon’sdevelopment as an Oriental medicine tourism des-tination (βTrust→Support = 0.617, t = 11.744,p < 0.01) were positive and significant, supportingH6. Overall, three constructs, program, venue, andconvenience, played an essential role in explain-ing festival tourists’ satisfaction, which served asan important antecedent in predicting tourists’trust. Trust appears to exert a positive effect onsupport for development as an Oriental medicinetourism destination.

Indirect and total effects

According to Bollen (1989), total effectsare combined with direct and indirect effects.Direct effects are the effect of independentvariables on dependent variables without med-iating effects by any other variable, and indir-ect effects are the effects mediated by at leastone other variable. Total effect, indicating thesum of direct and indirect effect, isimportant because it evaluates all changes,including the mediating effects from an inde-pendent variable to a dependent variable.Therefore, each dependent variable’s totaleffect is interpreted. As Table 3 shows, trustwas the powerful antecedent in predictingsupport for destination development with thelargest impact (0.617), followed by satisfac-tion (0.548), program (0.237), convenience(0.101), and venue (0.090). In predictingtrust, satisfaction was the powerful factor

with the largest effect (0.888), followed byprogram (0.384), convenience (0.164), andvenue (0.145). In predicting Expo satisfaction,program (0.432) was the most significant fac-tor, followed by convenience (0.185) andvenue (0.164).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the research model of tour-ists’ behavior at the Oriental medicine Expowas tested empirically using SEM, and therewere variations from earlier studies. The qual-ity dimensions of program, venue, and conve-nience affected satisfaction positively,whereas hospitality did not. Program qualityinfluenced satisfaction most highly, followedby venue and convenience factors. The find-ings indicate that these three quality dimen-sions were major contributors to touristsatisfaction at the Expo. Therefore, managersof Oriental medicine festivals should enhanceprogram quality by providing useful experien-tial opportunities and entertaining perfor-mance programs associated with the Orientalmedicine theme. They should provide spa-cious venues with comfortable facilities anda soothing atmosphere so that tourists canexperience Oriental medical treatment comfor-tably. Easy access to the Expo, including con-venient public transportation and car parking,is also an important factor in improving tour-ists’ satisfaction.

Program quality as a significant antecedent ofthe Expo tourists’ satisfaction is consistent with

TABLE 3. Decomposition of Effects

Direct effect Indirect effect Total effect

Satisfaction Trust Support Satisfaction Trust Support Satisfaction Trust Support

Program 0.432** – – 0.384* 0.237** 0.432** 0.384** 0.237**Hospitality 0.038 – – 0.034 0.021 0.038 0.034 0.021Venue 0.164* – 0.145* 0.090* 0.164* 0.145* 0.090*Convenience 0.185** – 0.164** 0.101** 0.185** 0.164** 0.101**Satisfaction – 0.888** – – 0.548** – 0.888** 0.548**Trust – 0.617** – – – 0.617**

Note. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Song et al. 223

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

earlier research (Lee et al., 2007a; Lee et al.2011; Yoon et al., 2010). For instance, Leeet al. (2007a) find that festival program (e.g.,event variety, organized management andoperation, interesting events, and experientialprograms) predicted positive emotion and satis-faction strongly. Also, Yoon et al. (2010) intheir Ginseng festival research identify that pro-gram quality (e.g., varied, effectively managed,funny, and experiential) was the crucial factor invalue, which through a mediating variable ofsatisfaction affected loyalty. Lee et al. (2011)in their Boryeong Mud festival research alsoexplore that festival program affected tourists’satisfaction through the mediating variable ofvalues. Venue quality as a significant antecedentof satisfaction is consistent with previous stu-dies. Again, Lee et al. (2007a) show that thefestival venue (e.g., facilities, space/size, clean-liness, and site atmosphere) predicted emotionand satisfaction. Likewise, Yoon et al. (2010)reveal that venue quality (e.g., convenient park-ing, good rest areas, and clean toilets) was animportant factor in value. Convenience qualityas a significant antecedent of satisfaction differsfrom earlier findings. According to Lee et al.(2007a), convenience did not directly or indir-ectly affect satisfaction significantly. However,hospitality quality was not a significant antece-dent of satisfaction. This finding does not cor-roborate previous research, in that Lee et al.(2007a) note that kind guides and staff, enoughknowledge about the festival, polite guides andstaff, and number of event guides and staffaffected satisfaction indirectly.

Satisfaction positively affected trust for theExpo and its host destination. This finding alignswith previous studies (Kim et al., 2009; 2011;Loureiro & Gonzalez, 2008) as well as market-ing literature (Flavián et al., 2006; Ganesan,1994; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Shim et al.,2008). The results reveal that satisfaction via themediating variable of trust enhanced supportindirectly. Since satisfaction explained morethan half the variance in trust, the relationshipof satisfaction with trust had the higher impactamong the six relationships. Importantly, trustaffected support for the Expo positively, which,in a tourism context, is somewhat consistent withprevious studies (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon,

2011b; Sheng, Tian, & Chen 2010). The findingsimply that tourists’ trust is a preconditionthrough which their satisfaction activates theirsupport for Jecheon’s ongoing development asa TKM tourism destination.

This finding inferring trust mediates Expo tour-ists’ satisfaction with their support for Jecheondeveloping as a TKM destination gives the Expoinitiative strategic credence in leveragingTKMandtourism in several ways. First, holding the Expowith its program, venue, and convenience qualitiessatisfied tourists, thus encouraging their trust inJecheon’s regional development as a TKM tourismdestination, which they support. This affirms qual-ity’s importance to tourists’satisfaction, as found inseveral festival studies (Axelsen & Swan, 2010;Yuan & Jang, 2008). Second, the program, venue,and convenience qualities and satisfaction reflectan emerging Expo brand that reinforces trust in thehost’s destination, distinguishing it from compet-ing destinations, as occurs between successfulsporting events and their host destinations (Chalip& Costa, 2005). Third, satisfaction, trust, and sup-port showbelief about TKMprovision in a touristiccontext, which the host destination could providesuccessfully. This is a valuable finding for the citygovernment, local TKM businesses, and residentsin several ways. First, because of the high numberof Expo tourists, it affirms, in part, the potentialdemand and recognition of Jecheon’s emergingTKM destination status. Second, it suggests theExpo and Jecheon coupling encouraged a positiveview of the destination, which given the key con-struct, the term “trustworthy” describes best(Ekinci & Hosany, 2006).

At a national level, Korea has five advantagesfor leveraging Oriental medicine tourism devel-opment. First, there is an existing regulatoryenvironment for educating and licensingOriental medicine practitioners. Second, there isan existing infrastructure of Oriental medicinehospitals and clinics. Third, the overseas distri-bution and success of cultural exports, such asthe Oriental medicine themed historical televi-sion dramas, have stimulated interest in KoreanOriental medicine in other Asian countries(Dong-A Ilbo, 2011). Fourth, as Korea has agrowing medical tourism sector, there is an exist-ing framework of cooperation among tourismproviders, governmental regulators, and the

224 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

health industry sector that can nurture Orientalmedical tourism. Fifth, the Expo’s popularityproves that there is interest in experiencingOriental medicine in a touristic setting.Consequently, Oriental medicine tourism stake-holders should leverage a consistent messageaffirming the trustworthiness of Oriental medi-cine in Korea by ensuring high quality across thetourist experiences and the health goods andservices they offer. Finally, further considerationshould be given to establishing a signature large-scale Oriental medicine tourism festival on atwo- or three-year cycle that attracts domesticand international attention, as the branding suc-cesses of large-scale cultural and sports eventshave demonstrated in other countries (Chalip &Costa, 2005; Harrison-Hill & Chalip, 2005;Hede & Jago, 2005; Prentice & Andersen, 2003).

The research suggests three findings useful forimproving the satisfaction, trust, and support fromOriental medicine tourism festivals and healthtourism events generally. First, program qualityarises from the variety, on schedule, entertaining,and unique contents associated with Oriental med-icine. So, Oriental medicine festivals should pre-sent diverse experiential programs associated withwell-being, anti-aging, weight loss, and preventivehealth care as well as treatments such as acupunc-ture, cupping, acupressure, and tasting herbalmedicines. Further, because tourists prefer enter-taining experiences from well-organized and var-ied programs, health festival organizers shoulddeliver high-quality exhibitions, entertainment,and treatment experiences. Second, the successof a health tourism festival venue arises from thespaciousness, cleanliness, and the soothing atmo-sphere associatedwith its site. Thus, health festivalorganizers should provide a site that is in amplesize, clean and hygienic, and designed to inspiretourists’ confidence and trust. Third, conveniencequality arises from a location featuring publictransport accessibility, easy car parking, and asite layout that tourists understand easily. Thus,organizers should ensure public transport access,convenient car parking, and an efficient site layoutfrom the tourists’ perspective. Previous studies onthe relationship between trust and support haveoccurred in non-tourism areas mostly (Luschet al., 2003; Rudolph, 2009). In tourism, Nunkooand Ramkissoon (2012) did examine the trust and

support relationship from a resident’s perspective.The literature implies that trust is an antecedentvariable of support for tourism development bytourists (Lee et al., 2012) and residents (Doney &Cannon, 1997; Lusch et al., 2003; Moorman et al.,1992; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Nunkoo &Ramkissoon, 2011a; Rudolph, 2009). Butresearch exploring the relationship between trustand support for destination development from atourist’s point of view is underreported. Therefore,it is an innovative finding that a large-scaleOriental medicine festival is an effective initiativefor reaching target markets and stimulating trust inOriental medicine that, in turn, encourages supportfor Oriental medicine tourism development.

Proposing a model where trust is the mediatingfactor between festival satisfaction and supportfor its host destination, this research examinedthe connection between a large-scale health tour-ism festival and its host city as TKM tourismdestination. Testing this with empirical data col-lected from tourists at the festival showed thatprogram, venue, and convenience qualities couldinfluence tourist satisfaction positively, whichwasthe antecedent of trust and then support for thehost destination’s TKM tourism development.Suggesting festival promoters and host destina-tion managers in the health tourism context canleverage the trust arising from a high-qualityhealth festival. In Korea and surrounding nations,there is belief in TKM’s efficacy; however, focus-ing this as a destination at country or provincelevel is challenging. The Expo proves how thistrust from a successful large-scale health tourismfestival leveraged support for a regional healthtourism destination. Importantly, Oriental medi-cine tourism overlaps both medical tourism andwellness tourism, so a health tourist can be seek-ing assistance with an existing illness or searchingfor preventative remedies that improve their well-being or both. In Asia, the tens of millions ofaging and financially viable middle class peopleare a budding market for the Oriental medicinetourism destinations that win their trust.

An unexpected finding was that the Expo tour-ists considered hospitality, including kindness,politeness, proper numbers of agents and helpers,and a useful Expo brochure, as an insignificantfactor in their satisfaction. Health tourism festivalorganizers should view this cautiously because

Song et al. 225

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

there could have been circumstances about hospi-tality specific to the Korean setting. For instance,the Expo hospitality met average Korean serviceexpectations and therefore was neither outstandingnor deficient. Further research should examinehealth tourism festival hospitality in greater detail.Although trust as a mediator between satisfactionand support was verified, applying the model inother festival settings should test this furtherbecause trust is a complex construct that credibil-ity, benevolence, integrity, and predictability alsoaffect. Therefore, questions used for measuringtrust in this research are only a starting point forfuture research identifying trust’s multipledimensions and other psychometric and situa-tional-specific properties of Oriental medicinetourism and health tourism festivals and needsto be identified further. Moreover, the SEMresults prove that festival tourists’ trust influ-enced their support for Jecheon’s Oriental med-icine tourism development positively.Therefore, extending the understanding of fes-tival tourists’ trust on support for destinationdevelopment contributes to the tourism litera-ture. Consequently, follow-up studies research-ing this relationship in similar areas of festivaland tourism development are possible for cor-roborating festival tourists’ trust and support fortourism developments. In conclusion, thisresearch demonstrates that impacts of large-scale health tourism festivals on their host coun-try or regional destination offer important pro-spects for further research supporting healthtourism initiatives.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1992). Assumptionsand comparative strengths of the two-step approach:Comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociological Methods &Research, 20(1), 321–333.

Ap, J. (1990). Residents’ perceptions research on thesocial impacts of tourism. Annals of TourismResearch, 17(4), 610–616.

Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts.Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 665–690.

Axelsen, M., & Swan, T. (2010). Designing festivalexperiences to influence visitor perceptions: The caseof a wine and food festival. Journal of TravelResearch, 49(4), 436–450.

Bagozzi, R., & Phillips, L. (1982). Representing and test-ing organizational theories: A holistic construal.Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(3), 459–490.

Baker, D. (2003). Oriental medicine in Korea. In H. Selin(Ed.), Medicine across cultures: History and practiceof medicine in non-western cultures (pp. 133–153),London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bentler, P., & Wu, E. (1995). EQS for windows: User’sguide. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental fit index forgeneral structural models. Sociological Methods &Research, 17(3), 303–316.

Bushell, R., & Sheldon, P. J. (2009). Wellness and tour-ism: Mind, body, spirit, place. New York, NY:Cognizant Communication Corporation.

Byrne, B. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS:Basic concepts, applications, and programming.Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cha, W. S., Oh, J. H., Park, H. J., Ahn, S. W., Hong,S. Y., & Kim, N. I. (2007). Historical differencebetween traditional Korean medicine andtraditional Chinese medicine. NeurologicalResearch, 29(1), 5–9.

Chalip, L., & Costa, C. A. (2005). Sport event tourism andthe destination brand: Towards a general theory. Sportin Society, 8(2), 218–237.

Churchill Jr, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developingbetter measures of marketing constructs. Journal ofMarketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Cole, S. T., & Chancellor, H. C. (2009). Examining thefestival attributes that impact visitor experience, satis-faction and re-visit intention. Journal of VacationMarketing, 15(4), 323–333.

Connell, J. (2006). Medical tourism: Sea, sun, sand and.surgery. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1093–1100.

Crompton, J. L., & Love, L. L. (1995). The predictivevalidity of alternative approaches to evaluating qualityof a festival. Journal of Travel Research, 34(1), 11–24.

Cronin Jr, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring servicequality: A reexamination and extension. The Journal ofMarketing, 56(3), 55–68.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination ofthe nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journalof Marketing, 61(2), 35–51.

Dong-A Ilbo. (2011, August). Japanese Throng toOriental Medicine Clinics in Korea. Retrieved fromhttp://english.donga.com

Ekinci, Y., & Hosany, S. (2006). Destination personality:An application of brand personality to tourism destina-tions. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 127–139.

Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M., & Gurrea, R. (2006). The roleplayed by perceived usability, satisfaction and consu-mer trust on website loyalty. Information &Management, 43(1), 1–14.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structuralequation models with unobservable variables and

226 JOURNAL OF TRAVEL & TOURISM MARKETING

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation inbuyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58(2),1–19.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The differentroles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment incustomer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2),70–87.

Global Spa Summit. (2010). Spas and the global well-ness market: Synergies and opportunities, preparedby SRI International, May 2010. Retrieved fromhttp://www.globalspasummit.org/images/stories/pdf/gss_spasandwellnessreport_final.pdf

Global Spa Summit. (2011). Wellness tourism and medi-cal tourism: Where do spas fit? May 2011. Retrievedfrom http://www.globalspasummit.org/images/stories/pdf/spas_wellness_medical_tourism_report_final.pdf

Gursoy, D., & Kendall, K. W. (2006). Hosting megaevents: Modeling locals' support. Annals of TourismResearch, 33(3), 603–623.

Hair Jr, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., &Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6thed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harrison-Hill, T., & Chalip, L. (2005). Marketing sporttourism: Creating synergy between sport and destina-tion. Sport in Society, 8(2), 302–320.

Hede, A. M., & Jago, L. (2005). Perceptions of the hostdestination as a result of attendance at a special event:A post-consumption analysis. International Journal ofEvent Management Research, 1(1), 1–12.

Hesketh, T., & Zhu, W. X. (1997). Health in China:Traditional Chinese medicine: One country, two sys-tems. BMJ, 315(7100), 115–117.

Heung, V., Kucukusta, D., & Song, H. (2011). Medicaltourism development in Hong Kong: An assessment ofthe barriers. Tourism Management, 32(5), 995–1005.

Jecheon City. (2011). 2010 World Oriental Medicine-BioEXPO in Jecheon, Korea. Retrieved from http://english.okjc.net/main/contents/contentsMain.do?menuNo=2319

Kim, S. (2011). Arabs coming to Seoul hospitals.Retrieved from http://koreajoongangdaily.joinsmsn.com/news/article/html/676/2944676.html

Kim, M. J., Chung, N., & Lee, C. K. (2011). The effect ofperceived trust on electronic commerce: Shoppingonline for tourism products and services in SouthKorea. Tourism Management, 32(2), 256–265.

Kim, T. T., Kim, W. G., & Kim, H. (2009). The effects ofperceived justice on recovery satisfaction, trust, word-of-mouth, and revisit intention in upscale hotels.Tourism Management, 30(1), 51–62.

Korea.net. (2011). Medical tourism: medicines and herbsto attract tourists. Retrieved from http://www.korea.net/detail.do?guid=26447

Lamberti, L., Noci, G., Guo, J., & Zhu, S. (2011). Mega-events as drivers of community participation in

developing countries: The case of Shanghai WorldExpo. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1474–1483.

Lee, C. K., & Back, K. J. (2006). Examining structuralrelationships among perceived impact, benefit, and sup-port for casino development based on 4 year longitu-dinal data. Tourism Management, 27(3), 466–480.

Lee, C. K., Bendle, L. J., Yoon, Y. S., & Kim, M. J.(2012). Thanatourism or peace tourism: Perceivedvalue at a North Korean resort from an indigenousperspective. International Journal of TourismResearch, International Journal of Tourism Research,14(1), 71–90.

Lee, J. S., Lee, C. K., & Choi, Y. J. (2011). Examiningthe role of emotional and functional values in festivalevaluation. Journal of Travel Research, 50(6),685–696.

Lee, Y. K., Lee, C. K., Lee, S. K., & Babin, B. J. (2007a).Festivalscapes and patrons' emotions, satisfaction, andloyalty. Journal of Business Research, 61(1), 56–64.

Lee, S. Y., Petrick, J. F., & Crompton, J. (2007b). Theroles of quality and intermediary constructs in deter-mining festival attendees' behavioral intention. Journalof Travel Research, 45(4), 402–412.

Lee, C. K., & Taylor, T. (2005). Critical reflections on theeconomic impact assessment of a mega-event: The caseof 2002 FIFAWorld Cup. Tourism Management, 26(4),595–603.

Lee, C. K., Yu, J. Y., & Yim, E. S. (2009). Estimating theeconomic impact of Gyeongbuk Oriental medical tour-ism using regional input-output model. Korean Journalof Tourism Sciences, 33(6), 56–74.

Leggat, P., & Kedjarune, U. (2009). Dental health, ‘dentaltourism’ and travellers. Travel Medicine and InfectiousDisease, 7(3), 123–124.

Loureiro, S. M. C., & Gonzalez, F. J. M. (2008). Theimportance of quality, satisfaction, trust, and image inrelation to rural tourist loyalty. Journal of Travel andTourism Marketing, 25(2), 117–136.

Lunt, N., & Carrera, P. (2010). Medical tourism: Assessingthe evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas, 66(1),27–32.

Lusch, R. F., O‘Brien, M., & Sindhav, B. (2003). Thecritical role of trust in obtaining retailer support for asupplier’s strategic organizational change. Journal ofRetailing, 79(4), 249–258.

Marinova, D., Ye, J., & Singh, J. (2008). Do frontlinemechanisms matter? Impact of quality and productivityorientations on unit revenue, efficiency, and customersatisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 72(2), 28–45.

Ministry of Health and Welfare. (2011). Traditional Koreanmedicines: Policy vision/objectives 2011. Retrievedfrom http://english.mw.go.kr/front_eng/jc/sjc0108mn.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=100311&MENU_ID=10031101

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993).Factor affecting trust in market research relationships.Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81–101.

Song et al. 227

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Myu

ng J

a K

im]

at 1

7:41

26

Febr

uary

201

4

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992).Relationships between providers and users of marketresearch: The dynamics of trust within and betweenorganizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3),314–329.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal ofMarketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011a). Residents' satisfac-tion with community attributes and support for tourism.Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 35(2),171–190.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011b). Developing acommunity support model for tourism. Annals ofTourism Research, 38(3), 964–988.

Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2012). Power, trust,social exchange and community support. Annals ofTourism Research, 39(2), 997–1023.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York, NY:McGraw-Hill.

Oliver, R. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedentsand consequences of satisfaction Decisions. Journal ofMarketing Research, 17(11), 460–469.

Organizing Committee of the 2010 World OrientalMedicine-Bio Expo. (2011). White paper of the 2010World Oriental Medicine-Bio EXPO. Jeocheon city:Organizing Committee of the 2010 World OrientalMedicine-Bio Expo.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988).Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consu-mer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing,64(1), 12–40.

Prentice, R., & Andersen, V. (2003). Festival as creativedestination. Annals of Tourism Research (Elsevier),30(1), 7–30.

Roman, S. (2003). The impact of ethical sales behaviouron customer satisfaction, trust and loyalty tothe com-pany: An empirical study in the financialservices industry. Journal of Marketing Management,19(9–10), 915–939.

Rudolph, T. J. (2009). Political trust, ideology, and publicsupport for tax cuts. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(1),144–158.

Sheng, C. W., Tian, Y. F., & Chen, M. C. (2010).Relationships among teamwork behavior, trust, per-ceived team support, and team commitment. SocialBehavior and Personality, 38(10), 1297–1306.

Shim, G. Y., Lee, S. H., & Kim, Y. M. (2008). Howinvestor behavioral factors influence investment satis-faction, trust in investment company, and reinvestmentintention. Journal of Business Research, 61(1), 47–55.

Shonk, D. J., & Bravo, G. (2010). Interorganizational supportand commitment: A framework for sporting eventnetworks. Journal of Sport Management, 24(3), 272–290.

Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., & Sabol, B. (2002). Consumertrust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges.Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 15–37.

Smith, J. B., & Barclay, D. W. (1997). The effects oforganizational differences and trust on the effective-ness of selling partner relationships. Journal ofMarketing, 61(1), 3–21.

Steenkamp, J., & Trijp, H. (1991). The use of LISREL invalidating marketing constructs. International Journalof Research in Marketing, 8(4), 283–299.

Suki, N. M. (2011). Assessing patient satisfaction, trust,commitment, loyalty and doctors' reputation towardsdoctor services. Pakistan Journal of MedicalSciences, 27(5), 1207–1210.

Voigt, C., Laing, J., Wray, M., Brown, G., Howat, G.,Weiler, B., & Trembath, R. (2010). Health tourism inAustralia: Supply, demand and opportunities. GoldCoast: Sustainable Tourism Ltd.

Wikipedia. (2012). Dongui Bogam. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donguibogam

Yoon, Y. S., Lee, J. S., & Lee, C. K. (2010). Measuringfestival quality and value affecting visitors' satisfactionand loyalty using a structural approach. InternationalJournal of Hospitality Management, 29(2), 335–342.

Youngman, I. (2009). Medical tourism statistics: WhyMcKinsey has got it wrong. Retrieved from http://www.imtjonline.com/articles/2009/mckinsey-wrong-medical-travel/?vAction=swpTextOnly

Yu, J. Y. (2009). Development plan of oriental medicaltourism in Gyeongbuk province: Internal report.Daegu, Korea: Gyeongsangbuk-do ProvincialGovernment.

Yu, J. Y., & Ko, T. G. (2012). A cross-cultural study ofperceptions of medical tourism among Chinese,Japanese and Korean tourists in Korea. TourismManagement, 33(1), 80–88.

Yuan, J., & Jang, S. (2008). The effects of quality andsatisfaction on awareness and behavioral intentions:Exploring the role of a wine festival. Journal ofTravel Research, 46(3), 279–288.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price,quality, and value: A means-end model andsynthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3),2–22.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). Thebehavioral consequences of service quality. Journal ofMarketing, 60(2), 31–46.

SUBMITTED: May 17, 2012FINAL REVISION SUBMITTED: