Inveighing Against Death Penalty in Indonesia

-

Upload

northwestern -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Inveighing Against Death Penalty in Indonesia

1

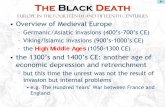

Chapter 1

Introduction

The discourse of the implementation and application of death penaltyseems to be developed during this reformation era. It has raised a question,why do the issues of death penalty get even more popular amidst thepressure to change the judiciary system, national legal system and in theera where the respect of human rights has become an urgent need anda joint-obligation in the international level.

Many kind of thesis can indeed be developed to find the answer asto why it happened. But it would be good if we can probe into howthe political nature of death penalty takes place. And, whether it wasborn from the awareness to build an authoritative legal system, or was itdeveloped to overcome the legal system that is not authoritative andbecome more distrustful instead? This problem cannot be answeredthrough a speculative analyses, which are often developed to justify theapplication of death penalty, such as that death penalty is justified byreligions; to get back what the perpetrator did; or that death penalty is ahumane act in order to end the suffering of the perpetrator.

Unfortunately, all the justificatory speculations to apply death penaltyhave indeed put Indonesia as one of the countries that has passed a lot ofdeath penalty sentences. According to reports from different internationalhuman rights organizations, Indonesia is one the countries that is stillapplying death penalty charges in its criminal judiciary system (retentionistcountry). The number of people sentenced with death penalty in Indonesiais quite high following China, USA, Congo, Saudi Arabia, and Iran.

2

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

From the data collected by Imparsial during this reformation era,which was since 1998 to December 2009, there were more or less 21death convicts who have been executed and some of whom waited formore than 10 years. Meanwhile there are 119 people who have been putin death row by the court authority and most of them are in the processof further legal efforts.

The practice of death penalty in a democratic era, of course, becomesan irony. As a state with a rule of law that respects and upholds itsconstitution it is only appropriate for Indonesia to abolish death penalty,considering that the constitution itself recognizes and guarantees the rightto life as a right that cannot be reduced in any situation and condition.But in reality death penalty as a form of cruel and inhumane punishmentis still being carried out. Although there is an international instrumentthat encourages the abolition of death penalty, but Indonesia insists toretain the existence of death penalty in this country. In that context, theefforts to abolish death penalty in this country seem to face a long andwinding road.

3

Chapter 2

The History of Death Penaltyin Indonesia: From Colonial to

New Order Regime

The issues of death penalty have never gotten a special place in thepublic discourse in Indonesia since the end of the colonial government.1The nature of debate only dwells on the philosophical level of law:between the approaches of positive law versus naturalist law; whereasoutside the political aspect, which are the sociological, historical,psychosocial aspects are seldom researched and debated by the public.General human rights contemporary study on death penalty connects allproblems concerning the relation between state policies, power, politicalinterests of the bureaucracy, class balancing and social transformation.

Michael Foucault has formulated an analytical knife to see the functionof (death) penalty in a politic and legal system and its relation with thedevelopment of science and the development of society.2 The mostimportant thing according to Foucault is that we have to discard the(exclusive) illusion of punishment, which is to reduce crimes.3 To Foucault,

1 In comparison with other countries such as the US and European countries, the debatein Indonesia on the issue has gone to the extent of spliting the public opinionsbetween the pros and the cons on the issues of death penalty. In Indonesia those whooppose death penalty are still very marginal.

2 Michel Foucault provides four general rules in discussing the concept of punishment.See Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish The Birth of the Prison, (1977), p. 23.

3 Ibid, p.24.

4

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

death penalty is a way to visualize that power truly exists. The tortureand execution of death penalty is a judicial and political ritual in order toexhibit that a crime has happened and that the power is in control.Execution and torture not only show the power operation, but alsoshow a justification of power.

In Indonesia, the execution of death penalty upon a perpetrator ofserious crimes or political opponents seems to be accepted as a commonevent by the society. It is considered commonplace because it is a reflectionof the weak legal consciousness of the society. In that context, it is importantto look back at the political history of death penalty in Indonesia as a basisto understand the nature of the state in applying the policy of death penalty.

A. Colonial Era: Planting the Influence of Power

The practice of death penalty in Indonesia is a legal product inheritedfrom the Dutch colonial, which is still not being corrected to this day.While death penalty is still being retained in Indonesia, the Dutch hasabolished the practice of death penalty since 1870 through a removalof death penalty charge from their penal code. Only for war crimes thatdeath penalty was still applicable in the Netherland.4

The Dutch finally abolished death penalty completely for any kindof crimes after the amendment of their Constitution on February 17,1983, which firmly stated that death penalty sentence (by judge) couldn’tbe passed.5 The consequence was to harmonize its legislation under theConstitution, including death penalty in military judiciary system.6

4 Jan Remmelink, Hukum Pidana: Komentar atas Pasal-Pasal dari Kitab UU Hukum PidanaBelanda dan Padanannya dalam Kitab UU Hukum Pidana Indonesia, [Criminal Law: Commentson Articles under the Netherlands Criminal Code and Its Compatibility with theIndonesian Criminal Code], (Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Media Tama, 2003), p. 459.

5 Ibid.6 Ibid.

5

The fact is that the abolition of death penalty does not apply forlegal implementation in the occupied territory of Dutch Indies (now isIndonesia). As known, the colonial government since 1870 applied the‘ethical politic’ to the Bumiputra (natives). This politic had a practicalobjective for the natives to bolster up the development of colonialcapitalism. This period was known as ‘Pax Neerlandica’, which wassuccessfully put a structural basis of modern bureaucracy within thecolonial government and a foundation to build infrastructure facilitiessupport for the economic system of capitalism. The basis that wasfounded in that period still leaves its footprints to this day.

In that period, the colonial government successfully transformed thejudiciary system and judicial authority that were still very personal tobecome a more rational system. The court in the early 19th century tookplace in a building that also served as a police station, torture chamber,and prison, as well as an execution stage.7 In early 20th century there wasa physical separation in the system, both in the form of infrastructureand bureaucracy administration. The judiciary system had also run,completed with the new penal codification. This is the way in which thecolonial power was (successfully) put into the collective (social) memory.A kind of knowledge to remember all obligations toward the rulerswas planted into the mind of occupied societies, from behaving politelyto obediently paying all tributes.

The colonial regime successfully arranged the structure within the colonialsociety by emphasizing that there was a borderline for the natives that wereprovisioned in the positive legal system. Offenders or dissidents werethreatened with harsh punishments, such as death penalty or exile/deportation.The differences between this period and the previous one were: First, that apunishment should go through an administrative process or procedures of

7 Ibid.

CHAPTER 2THE HISTORY OF DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA: FROM COLONIAL TO NEW ORDER REGIME

6

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

justice; second, death penalty execution or torture punishment was carried outin a public arena but was still closed and isolated.

The fact of those policies was actually congruent with Foucault’sanalysis, which said that a change or improvement of a new legal systemis not actually designed to be more humane or ethical. That was because,the change was not for the reduction of punishment but rather to improvethe punishment, punishing with a refined violence might be punishingwith a great absolute instead.8

In fact, the Dutch colonial government at that time was evenstrengthening the death penalty practices as an effort to threaten thepeople involved in the independence movement. The application ofarticle 104 of the Penal Code that contained provisions on crimes againstthe state security or subversive acts with death penalty as a punishmentwas used to perpetuate the repressive politic. The occupying governmentalso used death penalty to protect the military industry during the wartime,especially from resistance acts of labors.

The historical records show that the colonial governmentsystematically applied death penalty on almost any kind of legal offense.In the same period of time – as stated in Foucault’s research in France –the practices of death penalty happened in the form of draconian codein occupied territories. Death penalty execution in public was stillconducted randomly and carelessly under the authority of high-rankedofficials of colonial governments. The categories of criminal offensewere made very broad, from behaving impolitely toward the masters,running away from farms/mines, to insulting rulers and prominentpersons, to not paying tax/tribute to the King, to local rebels, to pirates.A Dutch historian and archeologist, Hans Bonked, in his writing explained,

8 Foucault, Op. Cit., p. 79-82.

7

what became the center of attention was the number of death penaltythat was really high in Batavia. In the beginning of 18th century, inAmsterdam that had 210 thousands inhabitants, there were five executionsa year. In Batavia that had 130 thousands inhabitants, the number ofpeople being sentenced to death was twice as high and sometimes evenhigher.9

B. Old Order Era: Continuing Power

Post colonial governance, the stages of domestic political fightsstrengthened, criminal penalties inherited from the colonial rule remainedin use. Besides bureaucracy, the colonial state policies was still beingused, and even worse was that the implementation of them imitatedwhat the colonial regime did. All political opponents of the state, suchas the cases of rebellion in Nusantara, in which all the perpetrators weresentenced to death (RMS, DI/TII and a perpetrator of treason ofPermesta).

The Penal Code that was called Wetboek van Strafrecht (W.v.S) wasdeclared to be in force based on a provision Article II of TransitoryRegulation of the 1945 Constitution and was confirmed with Law No.1/1946 on the making of W.v.S into the KUHP (Penal Code). Theimplementation of this KUHP could be said without any change at allcompared to its implementation in the colonial era. In its developmentlater on, death penalty was not only regulated in the KUHP as a part ofgeneral crimes but the government also passed a specific legislation thatregulated death penalty.

Under the Provisional Constitution of 1950, which was also knownas the era of Liberal Democracy (1950-1959), the parliament and the

9 Alwi Shahab, “Kamar Penyiksaan di Balai Kota” [Torture Dungeon at City Hall], Republika,November 16, 2003.

CHAPTER 2THE HISTORY OF DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA: FROM COLONIAL TO NEW ORDER REGIME

8

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

government passed legislation that regulated death penalty, which wasEmergency Law No. 12/1951 on Fire Arms and was promulgated onSeptember 4th, 1951.

During the era of Guided Democracy (1959-1966), the legalproducts that regulate the implementation of death penalty increased.The government passed Presidential Decree No. 5/1959 on the Authorityof General Attorney/Military General Attorney in aggravatingpunishment for criminal acts that endanger the implementation of foodand clothing supply. The decree was promulgated on July 27th, 1959.Besides that, the government also passed Government Regulation No.21/1959 that aggravated the punishment for economic crimes, whichwas promulgated on November 16th, 1959.

In 1963, the government passed the Law No. 11/PNS/1963 on theEradication of Subversive Activities, which was promulgated onOctober 16th, 1963. At that time, this law was employed to silenceSoekarno’s political opponents by throwing them into the prison withouttrials. On top of that, the government also passed the Law No. 31/PNS/1964 on the Basic Provisions of Atomic Energy. In itsdevelopment, this Law was replaced with Law No. 10/1997 on NuclearEnergy and the death penalty was replaced with life imprisonment.

In that era, the government passed Law No. 2/PNPS/1964 on theProcedure of the Implementation of Death Penalty Charges. In thisLaw, the execution of death convicts is by getting shot before a firingsquad. Before this Law there was no regulation on how an executionshould be carried out, except the practice of death penalty before afiring squad for military crimes, which was also inherited from the Dutchcolonial. Soekarno was actually once said openly that he did not like thepractice of death penalty, but in fact, his saying was not successfullybecome a consideration in changing the state policies on the issue.

9

C. New Order Era: Regime Consolidation

The overthrown of Soekarno regime by the leader of New Orderregime, Soeharto, did not stop the practice of death penalty. In early ofhis leadership, many people who were accused of getting involved inthe movement of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) weresentenced to death. It could be seen from the inclusion of PKI’s labor/peasant organizers as targets of cleansing operation against the PKI.10

The strategy of the New Order regime was similar with that of thecolonial regime. This regime practiced a war method in resolving socialand political conflicts (military social and and political roles) and in preparingthe new legal foundation that could protect the interests of capitalism. Forthat objectives, on one hand the regime wanted to appear as a single rulerthat used violence and on the other hand the regime showed a friendly(civilized) face by running a legal reformation by forming some legislations,although in fact it was focused more on the interest of foreign capitals.This strategy actually created an internal contradiction within the regimeitself, which eventually caused many dilemmatic decisions for the rulingregime. First, the interests of the regime to appear as effective inmonopolizing the power needed a kind of process of legal justificationto be an umbrella for many extra judicial actions. Second, on the otherhand, the regime had to appear as a ruler that respects and acta accordingto the laws, and also as a “hero” or thugs who was able to conquer itspolitical opponents, by any means necessary, in a fast and effective manner.

10 Many amongst the local worker and peasant leaders were actually did not have a structuralrelation with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Instead they were more closelyrelated to other parties or even non-partisan. They were seen as close to the PKI becausethey advocated the same issues as the PKI. This was recorded in the case of the executionof Mohamad Munir in 1985. The reason of the execution was not because he was theformal leader of workers but because he was accused of conspiring against thegovernment. See Marlies Glasius, Foreign Policy on Human Rights: Its Influence on Indonesia underSoeharto, (The Netherland: Doctoral Dissertation, Utrecht University, 1999), p. 111.

CHAPTER 2THE HISTORY OF DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA: FROM COLONIAL TO NEW ORDER REGIME

10

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

It was not surprising if the history of the founding of New Orderregime was marked with extra judicial killings and arbitrary detention.In a short time, the stooges of the regime became a direct part of thejudicial section: as attorneys, judges and executioners. The procession ofdeath penalty in this era was under the authority of Extraordinary MilitaryTribunal (Mahmilub). The Mahmilub itself actually was show trial witha goal to punish and finish off all of political enemies of the NewOrder (Soeharto). Political enemies were equal to enemies of the state.The message that the regime wanted to convey was that they havesuccessfully controlled the situation and acted according to the laws andconstitution. Whoever violate or was against the regime would meet thesame fate as convicts. Hence Mahmilub was none other than a justificationprocess for the ruler. The impact of it was the institutionalization ofpsychological fears and a feeling of powerless among civilians becauseof how powerful the state power was. What was said as legal reformationfrom this regime in reality was that they produced more regulations/legislations that became instruments to preserve fears.

To differentiate them with the Old Order regime and in order todraw sympathy from the public at that time, the New Order regimeused Law on the Eradication of Subversive Activities, which providesprovisions on death penalty as one of the instruments to chargecorruptors, although none have been convicted with it.

During the authoritarian regime of Soeharto, the rulers had a needto criminalize their political opponents. Death penalty formally becamethe state policy to effectively control the political structure. For the rulers,the main concern here was to hold ‘arrogant court theater plays’. Theexecution of punishments of convicts in front of the public was notthat important, but what’s more important was the stage for the politicof violence to constantly being held so that his political opponents wouldbe afraid psychologically. Second, the practice of death penalty also

11

emphasized on the premise that a political dissident was an enemy to thestate, in which there was a personification of Soeharto’s interests and thestate’s interests. The fear effect was being perpetuated by this authoritarianregime. The trick was by letting the bureaucratic inertia that was part ofthe intimidation of the regime to prolong.

The interesting thing from this period was the low number of crimes,especially in the 1970s. How did this happen? First, this was the result ofthe symbiotic relationship between groups of criminals and the militaryregime. The elements of crime became relatively organized and wasgiven an ‘appropriate’ place in the politic. Second, the state of emergencythat was still being imposed in big cities as an impact of Malari riot in1974 and a series of student demonstrations in 1978 had a role to suppressthe crime rate.

The death penalty procession for convicts in criminal cases in that periodwas fairly low. The most popular one was the execution of Kusni Kasdut(1980). The event was intended for by the regime to re-expose death penaltyto the public.11 It was because at the end of the 70s, there was a tendency ofincreasing crime rate. Besides that, in that period many corruption casesemerged, which disrupted the legal system such as court mafias.12

In the middle of disrupted situation, the regime had to remind thepublic that they were able to control the situation while still giving attention

11 Death penalty re-appeared in 1982. There was no death penalty cases eversince thecleansing operation against the PKI. It means there was a vacuum of more than 12 yearin which there was no death execution of criminals.

12 One of deviance is negative competition between the authorities of presecutor andpolice before 1981, especially in corruption cases. See Hamid Basyaib, Richard Holloway,and Nono Anwar Makarim, “Mencuri Uang Rakyat: 16 Kajian Korupsi di Indonesia” [StealingMoney from the People: The 16 Essays on Corruption in Indonesia], in Book 2, Pesta Tentara,Hakim, Bankir dan Pegawai Negeri [Parties of Soldier, Judges, Bankers and Civil Servants],(Jakarta: Yayasan Aksara, 2002), hal. 25.

CHAPTER 2THE HISTORY OF DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA: FROM COLONIAL TO NEW ORDER REGIME

12

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

to daily matters at the same time. On the other hand, prisons in thisperiod had a very limited capacity considering the prisons held morepolitical prisoners. The influencing factor was the fact that the justiceapparatus (attorneys, police and judges) made compromises withcriminals. It was not surprising when there were criminal leaders got outof prison in a short time.

Furthermore, the practices of the New Order (Orba) regime to winthe election needed special political operations to gather votes. Politicaloperation as such involved an intensive cooperation between politicians(Golkar), bureaucrats, academics, military officials and organized thugs.Nearing 1982, the political fights between the highest-rank leaders ofthe regime heated up, and it disturbed the security and social order. Asthe result, people who were allegedly going to be removed from thepolitical arena were organized thugs or gangs. The reprisal of this wasby spreading criminal conducts. The reaction from the rulers was bysetting up a ‘death squad’ that consisted of the element of military elites.The squad was publicly known as Mysterious Gunmen (Penembak Misterius– Petrus). What was unique from that reaction was that the decision todo it was actually against the new legal system they just set up (Law No.8/1981 on the Criminal Procedure Code). In the beginning the rulersdid not admit the actions. The situation changed after Soeharto explicitlyadmitted it in his semi autobiography. In the book, he admitted that heauthorized the illegal actions. It proved that Soeharto was a single playerin the political arena who successfully consolidated his power from 1988to 1997.13

From 1985 to 1997 there were some cases of death penalty executions,with political characters being exposed. The first one was the execution

13 One of the Prior to 1998, Soeharto was more powerful collectively throughcollaboration with his closest allies.

13

of the convicts of 1965 incident, such as Sudkarjo and GiyadiWidnyosuharjo. The official reason from the government was becausethey did not show regret of what they had done.14

Furthermore, the Soeharto regime took a popular policy by passingthe Law No. 22 Year 1997 on Narcotics and Law No. 5/1997 onPsychotropic. The birth of those legislations was a reaction to the increaseof the smuggling and dealing drugs as well as substance abuse duringthe decade of 1990s. The incapability of the government in handling thedrugs-dealing problems made them think that it was necessary to includedeath penalty as one of the punishments for this crime. The governmentmirrored the practices carried out by the Malaysian and Singaporeangovernments in eradicating the circulation of drugs.

14 As stated by Moerdiono, the former State Secretary, in The Jakarta Post, “RI, Holland,Agree to Boost Ties,” November 1, 1988.

CHAPTER 2THE HISTORY OF DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA: FROM COLONIAL TO NEW ORDER REGIME

15

Chapter 3

Policies and Practices ofDeath Penalty in The

Reformation Era

The start of reformation agenda in the aftermath of the fall ofSoeharto on May 21st, 1998 did not make death penalty disappearedfrom the Indonesian legal system even though the Anti-Subversive Lawwas finally being abolished due to the demand from different layers ofthe society. In the era of transitional democracy, all practices of politicaljustice and judiciary procession plays should be excluded from thepolitical system that was more democratic. Many thought that themanagement of politic of violence and politic of fear by imposingdeath penalty would be gone based on the assumption that all pastpolitical actors would be eliminated from the political arena. But thereality spoke the otherwise.

After five years into the reformation process, all past political actorswere still in power and adapted with the new condition. Meanwhile thejudiciary system remain lack of power, corrupt, unable and far from thesense of justice. As a result, there was no change of justice norms within thejudiciary system. Although the new political system seemed to be moredemocratic and open – for instance: the freedom of press was relativelyguaranteed – but the practice of death penalty was still carried out againstserious crimes such as drugs dealings, and also against those who wereconsidered as the enemy of the state such as in the cases of separatist rebels.

16

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

The Habibie administration, although it was a brief one, was veryproductive in making legislations, issuing the Law No. 31/1999 on theCorruption Eradication to replace the Law No. 3/1971. This law definitivelycharges corruptors with death penalty. Even more phenomenal was theLaw No. 26/2000 on Human Rights Court also regulates death penalty,notwithstanding the practice of death penalty was not used anymore in theinternational legal system –such as the Rome Statute of the InternationalCriminal Court (ICC) that has been recognized as the international standardto prosecute perpetrators of gross human rights violations.

The recent phenomenon was when the government quickly responded tothe terrorist’s threats by drawing up and passing the Anti-Terrorism Act (LawNo. 15 Year 2003). The substance of this law in many aspects was more toreinvigorate the position of the state as the violence monopoly holder ratherthan providing security and protection for the society.15 Post -Soehartogovernments seemed to try to put out an image that they were able to controlthe situation and to pay a big attention to the need of security feeling of thesociety. With that condition hence death penalty became an inevitable option.

As an implication, all recent public discourses on death penalty arerecycling the arguments that are relatively outdated and constantly usedas a justification for death penalty. Those outdated arguments keep beingreproduced by politicians, academics, and the media (TV stations). Asan example is the hypothesis that death penalty carries a deterrent effecton crime cases in the society. The hypothesis on the deterrent effect16 is

15 The formulation of criticism and the discussion of ideas for the Government and theParliament can be seen in Tim Imparsial [Imparsial Team], Terorisme: Definisi, Aksi danRegulasi [Terrorism: Definition, Action and Regulation], (Jakarta: Imparsial and the Coalitionfor the Safety of Civil Society, 2004).

16 A research in 1988 (revised in 1996) conducted by the United Nation on death penaltyand murder cases concluded that there was no scientific evidence that death penaltyhas more detterent effect than imprisonment. Furthermore, see Roger Hood, TheDeath Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), p. 238.

17

NO LAW ARTICLE

1 The Indonesian Penal Code

(KUHP)

Article 104, Article 111 paragraph (2), Article 124 paragraph (3), Article 140, Article 340, Article 365 paragraph (4), Article 444, Article 368 paragraph (2)

2 Indonesian Military Penal Code

(KUHPM)

Article 64, Article 65, Article 67, Article 68, Article 73 point 1, 2, 3 and 4, Article 74 point 1 and 2, Article 76 (1), Article 82, Article 89 point 1 and 2, Article 109 point1 and 2, Article 114 paragraph (1), Article 133 paragraph (1) and (2), Article 135 paragraph (1) point 1 and 2, paragraph (2), Article 137 paragraph (1) and (2), Article 138 paragraph (1) and (2), and Article 142 paragraph (2)

really convinced by those in power as a panacea when dealing with theincrease of crime rate, serious security threats and other social offense –such as cases of environmental destruction,17 whereas death penalty couldonly lower crime rate temporarily. Sociologically, the main source of thehigh rate of crimes is poverty, injustices, and mutual symbiotic relationsbetween rulers and thugs/criminals.18

A. Death Penalty under Indonesian Legislation

Death penalty exists in various applicable laws in Indonesia, bothinside and outside the Penal Code. Some provisions, both inside oroutside the Penal Code that provide death penalty are as follows.

Table 1.Death Penalty in Various Laws

17 The Minister of Environment immediately enforced the Anti-Terrorism Law againstall perpetrators of environmental destruction. A perpetrator of such crime iscategorized as a terrorist and is punishable with death penalty or imprisonment for atleast four years. See Koran Tempo, Perusak Lingkungan Bakal Dijerat UU Anti Terorisme[Environmental Vandal will be Punished with the Anti-Terorrism Law]”, January 21,2004.

18 The thug gangs have long been organized by politicians, especially during the 70s. SeeFrans Husken dan Huub de Jonge (eds.), Orde Zonder Order : Kekerasan dan Dendam diIndonesia 1965-1998, [Violence and Vengeance: Disontent and Conflict in New OrderIndonesia], translated by M. Imam Aziz, (Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2003).

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

18

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

The following are some examples on provisions that provide deathpenalty.1. Some criminal provisions under the Indonesian Criminal Code

Article 104The attempt undertaken with intend to deprive the President orVice President of his life or his liberty or to render him unfit togovernment, shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of twenty years.

3 Law No. 12 of 1951 on Firearms Article 1 paragraph (1)

4 Presidential Stipulation No. 5/1959 on the Authority of the General Attorney/Military General Attorney regarding to Increasing Punishment against Crimes that Jeopardize the Implementation of Food and Housing Equipment

Article 2

5 Government Regulation in lieu of Law No. 21 of 1959 on the Increasing Punishment on Economic-based Criminal Offenses

Article 1 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2)

6 Law No. 11/PNPS/1963 on the Elimination of Subversive Actions

Article 13 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2), Article 1 paragraph (1)

7 Law No. 31/PNPS/1964 on the Basic Provisions regarding to Atomic Energy

Article 23

8 Law No.4 year 1976 on the Amendment and Additional changes to several articles under the criminal code regarding to the expansion of the application of the provisions on crimes against aviation and aviation facilities

Article 479k paragraph (2) and 479o paragraph (2)

9 Law No. 5 of 1997 on Psychotropic Drugs Article 59 paragraph (2)

10 Law No.22 of 1997 on Narcotics Drugs

Article 80 paragraph (1), paragraph (2), paragraph (3) Article 81 paragraph (3), Article 82 paragraph (1), paragraph (2), and paragraph (3), Article 83

11 Law No.31 of 1999 on the Eradication of Corruption

Article 2 paragraph (2)

12 Law No.26 of 2000 on Human Rights Courts Article 36, Article 37, Article 41, Article 42 paragraph (3)

13 Law No.15 of 2003 on the Eradication of Terrorism

Article 6, Article 8, Article 9, Article 10, Article 14, Article 15, Article 16

14 Law No. 23 of 2002 on Child Protection Article 89 paragraph (1)

19

Article 111(1) Any person who colludes with either a foreign power or a king

or a community, with the intent to induce them to conducthostilities or to wage a war against the state, to strengthen them inthe intention made up thereto, thereby promising them assistanceor assisting them in their preparations, shall be punished by amaximum imprisonment of fifteen years.

(2) If the hostilities are committed or the war breaks out, either deathpenalty or life imprisonment or a maximum imprisonment oftwenty years shall be imposed

Article 124(1) Any person who in time of war intentionally renders assistance

to the enemy or prejudices the state against the enemy shall bepunished by a maximum imprisonment of fifteen years.

(2) Life imprisonment or a maximum imprisonment or twenty yearsshall be imposed, if the principal:1. Informs or surrenders a map, plan, drawing or description

of military works, or any information concerning militarymovements or plans;

2. Serve the enemy as a spy or harbor a spy.(3) Death Penalty or life imprisonment or a maximum imprisonment

of twenty years shall be imposed, if the principal:1. Betrays to the enemy, smuggles into the enemy’s hand, destructs

or damages an stronghold or post, which is reinforced oroccupied, a means of communication, a storehouse, a militaryprovision, or a military naval or army chest or any part thereof,obstructs, prevents or frustrates a plan for inundation oranother military plan devised or executed for defense or attack

2. Causes or facilitates a revolt, mutiny or desertion among thearmed forces

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

20

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

Article 140(1) The treason on the life or the liberty of a ruling President or

another head of a friendly state shall be punished by a maximumimprisonment of fifteen years

(2) If the treason on said life results in death or is undertaken withpremeditation, death penalty or a life imprisonment or amaximum imprisonment of twenty years shall be imposed

(3) If the treason on said life, undertaken with premeditation, resultin death, the death penalty or life imprisonment or a maximumimprisonment of twenty years shall be imposed.

Article 340The person who with deliberate intent and with premeditationtakes the life of another person, shall, being guilty of murder, bepunished by death penalty or life imprisonment or a maximumimprisonment of twenty years

Article 365(1) By a maximum imprisonment of nine years shall be punished

theft proceed, accompanied or followed by force or threat offorce against persons, committed with intent to prepare orfacilitate the theft, or when taken in the act, either to enable forhimself or for other accomplices to the crime to escape; or toensure possession of the thing stolen.

(2) A maximum imprisonment of twelve years shall be imposed:1. If the fact is committed either by night in a dwelling or at an

enclosed yard where a dwelling is; or on the public road; or ina railway carriage or train, which is in motion;

2. If the fact is committed by two or more united persons3. If the offender has forced an entrance into a place of the

crime by way of breaking into the hose or climbing in, orfalse keys, or a false order or a false costume;

21

4. if the fact results in serious physical injury.(3) A maximum imprisonment of fifteen years shall be imposed, if

the fact results in death.(4) Death Penalty or life imprisonment or a maximum

imprisonment of twenty years shall be imposed, if the fact resultsin a serious physical injury or death, committed by two or moreunited persons and thereby accompanied by one of thecircumstances mentioned under first and thirdly.

Article 444If the act of violence described in articles 438-441 result in thedeath of one of the persons on board the attacked vessel of oneof the assaulted person, the skipper, commander or captain andthose who have participated in the acts of violence shall bepunished by death penalty, life imprisonment or a maximumtemporary imprisonment of twenty years.

Article 479k(1) Life imprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of twenty years,

shall be imposed if the act mentioned in article 479 (i) and article479 (f):a. Is committed by two or more persons jointly:b. Is a continuation of a conspiracy?c. Is committed with premeditation;d. Causes damage to said aircraft, such that its navigation may be

endangered;e. Causes serious physical injury to a person;f. Is committed with intent to deprive a person of his liberty or

to maintain the deprivation of liberty of a person. (2)If said act causes the death of a person or the destruction of said

aircraft, the punishment shall be death punishment or lifeimprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of twenty years.

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

22

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

Article 479o(1) Life imprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of twenty years,

shall be imposed if the act mentioned in article 479 (l), article 479(m), and article 479 n:a. is committed by two or more persons jointly;b. is a continuation of a conspiracy;c. is committed with premeditation;d. causes serious physical injury to a person

(2) If said act causes the death of a person or the destruction ofsaid aircraft, the punishment shall be death penalty or lifeimprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of twenty years.

2. Article 23 of the Law No. 31/PNPS/1964 on Principle Provisionson Atomic Energy.

Article 23.Any person who intentionally disclose the confidentiality referredto in Article 22 shall be punished by death penalty or a lifetimeimprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of fifteen years bybeing discharged or not being discharged from his/her right tohold offices as referred to in the Article 35 of the Criminal Code.

Article 22 is as follows.Every officer of the atomic installation, National Atomic EnergyBody and other organizations that carry out the use of atomicenergy is obligated to maintain all confidential information inhis/her field of work regarding to atomic energy that he/sheobtain due to his/her official assignment.

3. Article 59 of the Law No. 5 of 1997 on Psychotropic Drugs(1) Any person:a. Uses first-class psychotropic drugs other than referred to in

23

Article 2 paragraph (2); orb. Produces and/or uses in the production process of first-class

psychotropic drugs referred to in Article 6; orc. Distributes first-class psychotropic drugs without conforming

the provision referred to in Article 12 paragraph (3); ord. Importing first-class psychotropic drugs other than for

scientific use; ore. Illegally possesses, retains and/or carries first-class psychotropic

shall be punished by short imprisonment of 4 years, and amaximum imprisonment of 15 years and a minimum fine ofIDR 150.000.000,00 and a maximum fine of 750.000.000,00

(2) If the crimes referred to in the paragraph (1) committed in anorganized manner, shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or a maximum imprisonment of 20 years and afine of 750.000.000,00.

4. Law No. 22 of 1997 on Narcotic DrugsArticle 80

(1) Anyone whomsoever without any rights or illegally:a. Produces, processes, extracts, converts, composes, or prepares

narcotics Category I shall be punished with a death sentence,or life sentence, or imprisonment of not more than 20 yearsand a fine of not more than IDR. 1,000,000,000. (One billionrupiahs);

b. ...c. ...

(2) In the case that the narcotic crime as referred to in:a. Clause (1), point a, is preceded by conspiracy, the punishment

shall be: a death penalty, or life sentence, or an imprisonmentof not less than four (4) years and not more than twenty (20)years, and a fine of not less than IDR. 200,000,000, (Twohundred million rupiah), and not more than IDR.

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

24

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

2,000,000,000. (Two billion rupiahs).b. ...c. ...

(3) In the case that the narcotic crime as referred to in:a. Clause (1), point a, is committed by an organized crime, the

punishment shall be a death penalty, or life sentence, or animprisonment of not less than five (5) years, and not morethan twenty (20) years imprisonment, and a fine of not lessthan IDR. 500,000,000. (Five hundred million rupiahs) andnot more than IDR. 5,000,000,000 (Five billion rupiahs);

b. ...c. ...

Article 81(1) Anyone whomsoever without any rights or illegally:

a. Brings, sends, transports, or transits narcotic category I shallbe punished with an imprisonment of not more than fifteen(15) years and a fine of not more than IDR750,000,000. (Sevenhundred fifty million rupiahs).

b. ...;c. ...;

(2) ...a. ...;b. ...;c. ...;

(3) In the case that narcotics crime as referred to in:a. Clause (1), point b, is committed by an organized crime; the

punishment shall be a death penalty, life sentence, orimprisonment of not less than four years and not more thantwenty years and a fine of not less than IDR 500,000,000.(Five hundred million rupiahs), and not more than IDR4,000,000,000. (Four billion rupiahs).

25

b. ...;c. ...;

Article 82(1) Anyone whomsoever without any rights or illegally:

a. Imports, exports, offers for sale, distributes, sells, buys, delivers,acts as broker or exchanges narcotics Category I, shall bepunished with a death penalty, or life sentence, or imprisonmentof not more than twenty (20) years, and a fine of not morethan IDR 1,000,000,000. (One billion rupiah).

b. ...;c. ...;

(2) In the case that the narcotic crime as referred to in:a. Clause (1), point a, is preceded with conspiracy, the punishment

shall be a death penalty, life sentence, or an imprisonment ofnot less than four year and not more than twenty years, and afine of not less than IDR 200,000,000. (Two hundred millionrupiahs), and not more than IDR 2,000,000,000. (Two billionrupiahs)

b. ...;b. ...;

(3) In the case that the narcotic crime as referred to in:a. Clause (1), point a, is committed by an organized crime, the

punishment shall be a death penalty, life sentence or animprisonment of not less than five (5) years, and not morethan twenty (20) years, and a fine of not less than IDR500,000,000. (Five hundred million rupiahs) and not morethan IDR 3,000,000,000. (Three billion rupiahs)

b. b. ...;c. c. ...;

Article 83

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

26

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

An attempt or a conspiracy to commit narcotic crime as containedin Articles 78, 79, 80, 81 and 82 shall be punished with equalimprisonment to those stipulated therein

5. Article 2 paragraph (2) Law. 31 year 1999 on Eradication of CriminalActs of Corruption

(1) Anyone unlawfully enriching himself and/or other persons or acorporation in such a way as to be detrimental to the finance ofthe state or the economy of the state shall be liable to lifeimprisonment, or a prison term of not less than 4 (four) year andnot exceeding 20 (twenty) years and a fine of not less than IDR200,000,000 and not exceeding IDR 1,000,000,000.

(2) In the event that corruption as referred to in paragraph (I) iscommitted under certain circumstances, death penalty may beapplied.

6. Article 27 of Law No.9 of 2008 on the Use of Chemical Substancesand the Prohibition of the Use of Chemical Substances as ChemicalWeapons.

Any person who violates the provision referred to in Article 14 shallbe punished by death penalty or a lifetime imprisonment, or minimumimprisonment of 4 (four) years and maximum imprisonment of 20(twenty) years.

While according to Article 14, death penalty is applicable for:Every person is prohibited from:

a. developing, producing, obtaining, and/or possessing chemicalweapon;

b. transferring, both directly and indirectly, chemical weapon toanyone;

c. using chemical weapon;d. getting involve in a military preparation to use chemical weapon; or

27

e. getting involve, assisting and/or persuading other people byany means in the prohibited activities referred to in this Law.

7. Article 6 and Article 9, Article 14 of the Law No. 15 of 2003 on theAdoption of Government Regulation in Lieu of Law No. 1 of 2002on the Eradication of the Crime of Terrorism.

Article 6Any person who by intentionally using violence or threats ofviolence, creates a widespread atmosphere of terror/fear orcauses mass casualties, by taking the liberty or lives and propertyof other people, or causing damage or destruction to strategicvital objects, the environment, public facilities or internationalfacilities, faces the death penalty, or life imprisonment, or between4 and 20 years of imprisonment.

Article 9Any person who illegally brings into Indonesia, makes, accepts,attempts to obtain, transfers or tries to transfer, controls, carries,has supply of, possesses, stores, transports, hides, uses or takes toor from Indonesia: a firearm, ammunition, explosives, or otherdangerous materials with intent to perform an act of terrorism,shall be punished by death penalty or life imprisonment, orminimum imprisonment of 3 years and maximum imprisonmentof 20 years.

Article 14Any person who plans or incites others to commit crime ofterrorism referred to in Article 6, Article 7, Article 8, Article 9,Article 10, Article 11, and Article 12 shall be punished by deathpenalty or life imprisonment.

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

28

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

8. Article 89 paragraph (1) of the Law No.23 of 2002 on Child ProtectionAny person who by intentionally placing, allowing, involving, ordering

to involve children in abusing, producing, or distributing narcotics and/or psychotropic substances shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or maximum imprisonment of 20 years and minimumimprisonment of 5 years and maximum fine of IDR 500.000.000,00and minimum fine of IDR 50.000.000,00.

9. Article 36 and Article 37 of the Law No. 26 of 2000 on HumanRights Courts.

Article 36Any person who commits any acts referred to in Article 8 pointa, b, c, d, and e shall be punished by death penalty or life sentenceor maximum imprisonment of 25 years and minimum of 10years.

Article 37Any person who commits any acts referred to in Article 9 pointa, b, c, e, or j shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or maximum imprisonment of 25 years andminimum imprisonment of 10 years.

According to Article 8 and Article 9, death penalty is applicable forthe following crimes.

Article 8Genocide as referred to in Article 7 point a is any of the followingacts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, anational, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:a. Killing members of the group;b. Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the

29

group;b. Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated

to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (c. Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the

group; (d. Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Article 9Crimes against humanity referred to in Article 7 point b is any ofthe following acts when committed as part of a widespread orsystematic attack directed against any civilian population, as such:a. Murder;b. Extermination;b. Enslavement;c. Deportation or forcible transfer of population;d. Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty

in violation of fundamental rules of international law;e. Torture;f. Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy,

enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violenceof comparable gravity;

g. Persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity onpolitical, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender asdefined in paragraph 3, or other grounds that are universallyrecognized as impermissible under international law, inconnection with any act referred to in this paragraph or anycrime within the jurisdiction of the Court;

h. Enforced disappearance of persons;i. The crime of apartheid;

The abovementioned provisions explicitly confirm that Indonesia isstill imposing death penalty, although, at the regulation level, it is applicable

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

30

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

as an alternative between death penalty, life imprisonment and temporaryimprisonment. Judge has the authority to determine the punishment. Inpractice, death penalty is still being applied, even though there arealternatives of life imprisonment and temporary imprisonment.

In the new draft of the Indonesian Criminal Code, which has beendiscussed by the government for quite sometimes, death penalty stillexists. Death penalty is determined as one of principle punishments thathas a specific nature and is always categorized as an alternative (Article66 of the Criminal Code Bill). Death penalty and the methods of theexecution are specifically provided in the Paragraph 11 of the Article 87to Article 90 of the Criminal Code Bill, moreover, there is also a provisionthat stipulates that statue of limitation shall not be applied for deathpenalty (Article 155 of the Criminal Code Bill).19

Under the Criminal Code Bill, there are still 20 provisions that providedeath penalty. Death penalty applies as an alternative punishment for thecrimes of subversion, terrorism, gross human rights violations, narcoticsand psychotropic substances, war or armed conflict crimes, as well aspower abuse that inflicts financial loss to the state. The followings arethe provisions under the Criminal Code Bill that provide death penalty:20

Article 215Any person who commits acts of subversion with intend todeprive the President or Vice President of his life or his liberty orto render him unfit to government, shall be punished by deathpenalty or life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5years and maximum imprisonment of twenty years.

19 Draft Bill on Criminal Code, Draft 09/04/2006.20 Ibid.

31

Article 228(1) By a minimum imprisonment of 3 years and a maximum of 15

years shall be punished:a. Any person who colludes with either a foreign country or

organization, with the intent to induce them to conducthostilities or to wage a war against the Republic of Indonesia;

b. strengthening the intention of the foreign country ororganization to commit the acts referred to in point a; or

c. promising assistance to the foreign country or organization orassisting them in the preparations to commit the acts referredto in point a.

(2) If the hostilities referred to in paragraph (1) are committed orthe war breaks out, either death penalty or life imprisonment ora minimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximumimprisonment of 20 years shall be imposed.

Article 237 (1) Any person who in time of war intentionally renders assistance

to the enemy or prejudices the state against the enemy, shall bepunished by a minimum imprisonment of 3 years and a maximumimprisonment of 15 years

(2) Life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5 years anda maximum imprisonment or 20 years shall be imposed, if theperpetrator of any acts referred to in Article (1):a. Informs or surrenders a map, plan, drawing or description

of military buildings or any information concerning militarymovements or plans to the enemy; or

b. Serve the enemy as a spy or harbors a spy. (3) Death penalty of life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment

of 5 years and a maximum imprisonment or 20 years shall beimposed, if the perpetrator of any acts referred to in Article (1):a. Betrays to the enemy, smuggles into the enemy’s hand, destructs

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

32

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

or damages an stronghold or post, which is reinforced oroccupied, a means of communication, a storehouse, a militaryprovision, or a military naval or army chest or any part thereof,obstructs, prevents or frustrates a plan for inundation oranother military plan devised or executed for defense or attack;or

b. Causes or facilitates a revolt, mutiny or desertion among thearmed forces

Article 242Any person who by intentionally using violence or threats ofviolence, creates a widespread atmosphere of terror/fear orcauses mass casualties, by taking the liberty or lives and propertyof other people, or causing damage or destruction to strategicvital objects, the environment, public facilities or internationalfacilities, shall be punished for terrorism by death penalty, orlife imprisonment, or a minimum imprisonment of 5 years and amaximum imprisonment of 20 years.

Article 244Any person who uses chemical substance, biological weapons,radiology, microorganism, radioactive or their components withintend to commit terrorism shall be punished by death penaltyor life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5 yearsand a maximum imprisonment of 20 years.

Article 247Any person who plans and/or incites others to commit crime ofterrorism referred to in Article 242 to Article 246 shall be punishedby death penalty or life imprisonment or a minimumimprisonment of 5 years and a maximum imprisonment of 20years.

33

Article 250(1) Shall be punished for terrorism, any person who commits crimes

referred to in Article 256 and Article 257 by life imprisonment ora minimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximumimprisonment of 20 years, and Article 258 by death penalty, lifeimprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5 years and amaximum imprisonment of 20 years.

Article 262 (1) Shall be punished by life imprisonment and a minimum imprisonment

of 5 years and a maximum imprisonment of 20 years, if the crimesreferred to in Article 259, Article 260, or Article 261:a. Jointly committed by 2 persons or more;b. As a follow-up conspiracy; orc. Inflict severe injuries.

(2) If the crimes referred to in Article (1) inflict casualties ordisintegration of the aircraft, the perpetrator shall be punished bydeath penalty or life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonmentof 5 years and a maximum imprisonment of 20 years.

Article 269 (1) Any person who commits subversion activities with intend to

deprive the life or liberty of the head of a friendly state shall bepunished by a minimum imprisonment of 3 years and a maximumimprisonment of 15 years.

(2) If the act of subversion referred to in paragraph (1) inflict deathto the head of the state, shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or minimum imprisonment of 5 years and amaximum imprisonment of 20 years.

Article 394(1) Shall be punished by Death Penalty or life imprisonment, or a

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

34

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

minimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximumimprisonment of 20 years, every person who commits thefollowing acts with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national,ethnical, racial, or religious group:a. killing members of the group;b. causing serious bodily or mental harm to member of the

group;c. deliberately inflicting on the group condition of life calculated

to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;d. imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

ore. forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Article 395(1) Shall be punished by death penalty or life imprisonment, or a

minimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximum of 20 years,everyone who commits the following acts when committed aspart of a widespread or systematic attack directed against anycivilian population, with knowledge of the attack:a. Murder;b. Extermination;c. Enslavement;d. Deportation or forcible transfer of population;e. Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty

in violation of fundamental rules of international law;f. Torture;g. Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy,

enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violenceof comparable gravity;

h. Persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity onpolitical, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender orother grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible

35

under international law;i. Enforced disappearance of persons;j. The crime of apartheid; ork. Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing

great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental orphysical health.

Article 396Shall be punished by death penalty or life imprisonment or aminimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximumimprisonment of 20 years, every person who in times of war orarmed conflict commits gross violation against persons orproperty protected under the provisions of the relevant GenevaConvention as such:a. Willful killing;b. Torture and inhuman treatment including biological

experiments;c. Willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or

health;d. Extensive destruction and appropriation of property not

justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully andwantonly;

e. Compelling a prisoner of war or other protected person toserve in the forces of a hostile Power;

f. Willfully depriving a prisoner of war or other protected personof the rights of fair and regular trial;

g. Unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement;or

h. Taking of hostages.

Article 397Shall be punished by death penalty or life imprisonment, or a

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

36

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

minimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximum of 20 years,every person who commits other serious violation of the lawand customs applicable in international armed conflict, within theestablished framework of international law, namely, any of thefollowing acts:a. Intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population as

such or against individual civilians not taking direct part inhostilities;

b. Intentionally directing attacks against civilian objects, that is,objects which are not military objectives;

c. Intentionally directing attacks against personnel, installations,material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistanceor peacekeeping mission in accordance with the Charter ofthe United Nations, as long as they are entitled to the protectiongiven to civilians or civilian objects under the international lawof armed conflict;

d. Intentionally launching an attack in the knowledge that suchattack will cause incidental loss of life or injury to civilians ordamage to civilian objects or widespread, long-term and severedamage to the natural environment which would be clearlyexcessive in relation to the concrete and direct overall militaryadvantage anticipated;

e. Attacking or bombarding, by whatever means, towns, villages,dwellings or buildings which are undefended and which arenot military objectives;

f. Killing or wounding a combatant who, having laid down hisarms or having no longer means of defense, has surrenderedat discretion;

g. Making improper use of a flag of truce, of the flag or of themilitary insignia and uniform of the enemy or of the UnitedNations, as well as of the distinctive emblems of the GenevaConventions, resulting in death or serious personal injury;

37

h. The transfer, directly or indirectly, by the Occupying Powerof parts of its own civilian population into the territory itoccupies, or the deportation or transfer of all or parts of thepopulation of the occupied territory within or outside thisterritory;

i. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated toreligion, education, art, science or charitable purposes, historicmonuments, hospitals and places where the sick and woundedare collected, provided they are not military objectives;

j. Subjecting persons who are in the power of an adverse partyto physical mutilation or to medical or scientific experimentsof any kind which are neither justified by the medical, dentalor hospital treatment of the person concerned nor carriedout in his or her interest, and which cause death to or seriouslyendanger the health of such person or persons;

k. Killing or wounding treacherously individuals belonging tothe hostile nation or army;

l. Declaring that no quarter will be given;m. Destroying or seizing the enemy’s property unless such

destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by thenecessities of war;

n. Declaring abolished, suspended or inadmissible in a court oflaw the rights and actions of the nationals of the hostile party;

o. Compelling the nationals of the hostile party to take part inthe operations of war directed against their own country, evenif they were in the belligerent’s service before thecommencement of the war;

p. Pillaging a town or place, even when taken by assault;q. Employing poison or poisoned weapons;r. Employing asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and all

analogous liquids, materials or devicess. Employing bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

38

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

body, such as bullets with a hard envelope which does notentirely cover the core or is pierced with incisions;

t. Employing weapons, projectiles and material and methodsof warfare which are of a nature to cause superfluous injuryor unnecessary suffering or which are inherently indiscriminatein violation of the international law of armed conflict, are thesubject of a comprehensive prohibition;

u. Committing outrages upon personal dignity, in particularhumiliating and degrading treatment;

v. Committing rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forcedpregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexualviolence also constituting a grave breach of the GenevaConventions;

w. Utilizing the presence of a civilian or other protected personto render certain points, areas or military forces immune frommilitary operations;

x. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings, material, medicalunits and transport, and personnel using the distinctive emblemsof the Geneva Conventions in conformity with internationallaw;

y. Intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfareby depriving them of objects indispensable to their survival,including willfully impeding relief supplies as provided forunder the Geneva Conventions;

z. Conscripting or enlisting children under the age of 15 (fifteen)years into the national armed forces or using them to participateactively in hostilities.

Article 398Shall be punished by death penalty or life imprisonment, or aminimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximumimprisonment of 20 years, every person who commits, in the

39

case of an armed conflict not of an international character, seriousviolations of article 3 common to the Geneva convention, namely,any of the following acts against persons taking no active part inthe hostilities, including members of armed forced who havelaid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness,founds, detention or any other cause:a. Violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds,

mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;b. Committing outrages upon personal dignity, in particular

humiliating and degrading treatment; ord. The passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions

without previous judgement pronounced by a regularlyconstituted court, affording all judicial guarantees which aregenerally recognized as indispensable.

Article 399Shall be punished by death penalty or life imprisonment, or aminimum imprisonment of 5 years and a maximumimprisonment of 20 years, everyone in armed conflicts not of aninternational character, within the established framework ofinternational law, namely, any of the following acts:a. Intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population as

such or against individual civilians not taking direct part inhostilities;

b. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings, material, medicalunits and transport, and personnel using the distinctive emblemsof the Geneva Conventions in conformity with internationallaw;

c. Intentionally directing attacks against personnel, installations,material, units or vehicles involved in a humanitarian assistanceor peacekeeping mission in accordance with the Charter ofthe United Nations;

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

40

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

d. Intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated toreligion, education, art, science or charitable purposes, historicmonuments, hospitals and places where the sick and woundedare collected, provided they are not military objectives;

e. Pillaging a town or place, even when taken by assault;f. Committing rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced

pregnancy, enforced sterilization, and any other form of sexualviolence constituting a serious violation of the GenevaConventions;

g. Conscripting or enlisting children under the age of fifteen yearsinto armed forces or groups or using them to participateactively in hostilities;

h. Ordering the displacement of the civilian population forreasons related to the conflict, unless the security of the civiliansinvolved or imperative military reasons so demand;

i. Killing or wounding treacherously a combatant adversary;j. Declaring that no quarter will be given;k. Subjecting persons who are in the power of another party to

the conflict to physical mutilation or to medical or scientificexperiments of any kind which are neither justified by themedical, dental or hospital treatment of the person concernednor carried out in his or her interest, and which cause death toor seriously endanger the health of such person or persons;or

j. Destroying or seizing the property of an adversary unless suchdestruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by thenecessities of the conflict.

Article 506Any person whomsoever without any rights or illegally produceor provide narcotic drugs, shall be punished by death penalty orlife sentence, or imprisonment of not less than 5 (five) years and

41

not more than 20 (twenty) years and a fine of minimum ofCategories IV and maximum of Categories VI.

Article 508Any person whomsoever without any rights or illegally imports,exports, offers for sale, distribute, sells, buys, delivers, acts as brokeror exchanges narcotics, shall be punished with a death penalty, orlife sentence, or imprisonment or not less than 5 (five) years andnot more than 20 (twenty) years, and a fine of not less than CategoryIV and not more than Category VI.

Article 506Any person who unlawfully and illegally produce or suppliesnarcotic drugs, shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5 years and amaximum imprisonment of 20 years and a fine of not less thanCategory IV and not more than Category VI.

Article 508Every person who unlawfully and illegally imports, exports, offersto sell, supplies, sells, buys, gives, takes, becomes a mediator in atrade of or exchanges narcotic drugs, shall be punished by deathpenalty or life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5years and a maximum imprisonment of 20 years and a fine ofnot less than Category IV and not more than Category VI.

Article 515 (1) Every person who produces and/or uses in a production process

of psychotropic drugs, distributes, imports, or exportspsychotropic drugs shall be punished by death penalty or lifeimprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5 years and amaximum imprisonment of 20 years and a fine of not less than

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

42

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

Category IV and not more than Category VI.

Article 572Any person who with premeditation takes the life of anotherperson shall be punished for premeditated murder by deathpenalty or life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of 5years and a maximum imprisonment of 20 years.

Article 684Crimes referred to in Article 682 and Article 683 shall be punishedby death penalty, life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonmentof 5 years and a maximum imprisonment of 20 years if:a. The crimes committed against funds designed for emergency

response, national natural disasters, responding widespreadsocial uprising, responding economic and monetary crisis; or

b. There is a repetition of crime.

Article 682 and Article 683 provides stipulations regarding to powerabuse that inflicts financial loss to the State as follows:

Article 682Any person who unlawfully and illegally enriching himself and/or other persons or a corporation in such a way as to be detrimentalto the finance of the state or the economy of the state shall bepunished by life imprisonment or a minimum imprisonment of5 years and a maximum imprisonment of 20 years and a fine ofnot less than Category IV and not more than Category VI.

Article 683Anyone with the intention of enriching himself or other personsor a ( corporation, abusing the authority, the facilities or othermeans at ( their disposal due to rank or position in such a way

43

that is ( detrimental to the finances of the state or the economyof the state, shall be punished by life imprisonment or a minimumimprisonment of 5 years and a maximum imprisonment of 20years and a fine of not less than Category IV and not more thanCategory VI.

B. The Practice of Death Penalty in TheReformation Era21

During the reformation era from 1998 to December 2009, deathpenalty convicts who had been executed were 21 people. The threemajor cases underlying the executions were murder with 13 cases, drugs/psychotropic with 5 cases and terrorism with 3 cases. 2008 was the yearwith most executions, which was 10 people with the following order:murder cases (5 persons), drugs and psychotropic cases (2 persons), andterrorism cases (3 persons)/

Table 2.Types of Cases of Death Penalty

Meanwhile the death sentence event that drew most public attentionwas the execution of Amrozi bin Nurhasyim, Abdul Aziz a.k.a Imam

21 Data on death convicts who are still on the death row and those who have beenexecuted over the course of 11 years during the reformation era (1998 – 2009) couldbe seen on Annex 2. For similar data during the New Order Era (1982 -1997) ispresented on Annex 1.

No Cases Number

1 Murder 13 persons

2 Drugs and Psychotropic 5 persons

3 Terrorism 3 persons

Total 21 persons

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

44

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

Samudra and Ali Ghufron a.k.a Mukhlas who were the three convictsof Bali Bombing I, which was carried out in November 2008. This casewas the last execution until the end of 2009.

From the death penalty verdict, there were 119 convicts who weresentenced with death penalty by the court authorities, from the level ofCourt of First Instance to the level of Supreme Court. The most casesthat received death sentence were drugs and psychotropic with 72 cases;murder with 38 cases; and terrorism with 9 cases. If traced backaccording to the year, 2001 was the year with most death sentences with17 verdicts; 2006 and 2008 with 15 verdicts for each year; 2003 with 12verdicts; 2000, 2004 and 2007 with 10 verdicts for each year; 2002 and2005 with 9 verdicts for each year; 1998 with 5 verdicts; and the leastwas 2009 with 1 verdict.

Table 3.Types of Cases of Death Penalty

67 out of 119 people on death row are still in the process of furtherlegal efforts, from appeal process, to appeal to the Supreme Court(kasasi), to review or appeal after verdict in the level of Supreme Court,to clemency. In the meantime the number of people who were sentencedwith death penalty and have been imprisoned in the correctionalinstitutions more than five years are 60 people.

Viewed from the aspect of judicative authorities that passed the most

No Cases Number

1 Narcotics and Psychotropic 72 cases

2 Murder 38 cases

3 Terrorism 9 case

Total 119 cases

45

death penalty verdicts is Tangerang Court of First Instance, whichsentenced 32 people to death. Most of the cases were drugs andpsychotropic; West Jakarta Court of First Instance with 6 death penalties;Denpasar – Bali Court of First Instance with 5 death penalties (terrorismand drugs/psychotropic); Central Jakarta and South Jakarta Courts ofFirst Instance with 5 death penalties; Medan and Lubuk Pakam – NorthSumatra Courts of First Instance, with 4 death penalties for each court.

Out of 119 death penalty cases, majority are Indonesian citizens witha total of 69 people, while the foreign citizens who have been givendeath penalty since 1998 to this day are 55 people. Death penalty convictswith Nigerian nationality top the number with 11 people. Following itare Australian with 7 people; Nepalese with 6 people; Chinese with 5people; Malaysian with 4 people; Singaporean with 3 people: Brazilian,Thailand, Pakistani, Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Dutch with 2 people foreach nationality; while Angolan, South African, Sierra Leone, Ghana,Senegal, India and France nationalities are on the bottom list with 1person each. Most of them were charged with drugs and psychotropicoffense.

Table 4.Foreign Citizens Who Have Been Sentenced with Death Penalty

No Nationality Number

1 Nigeria 11 people

2 Australia 7 people

3 Nepal 6 people

4 China 5 people

5 Malaysia 4 people

6 Singapore 3 people

7 Malawi 2 people

8 Zimbabwe 2 people

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

46

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA

C. Torture in Death Penalty

From the death penalty data explanation during the decade ofreformation, what is very troubling and moving at the same time wasthe grace period that often takes a very long time and unclear aboutwhen the execution would take place, such as the experience of Sumiarsihand Sugeng who were imprisoned for more than 10 years. It was evenalmost 20 years when the time of their execution was decided.

The delay of execution that sometimes takes more than 10 yearsclearly is the responsibility of those who have the power. Thisresponsibility cannot be morally and ethically justified and it is not acommendable act, especially if there are some unclear motivations installing the time of execution. In this case, the rulers have violated humanrights that are guaranteed by the article 28(I) Second Amendment of the1945 Constitution. Delaying execution without a clear motivation clearlyis a cruelty that has an unthinkable implication and consequences, which

9 Pakistan 2 people

10 Thailand 2 people

11 Brazil 2 people

12 Dutch 2 people

13 Angola 1 people

14 South Africa 1 people

15 Sierra Leone 1 people

16 Ghana 1 people

17 Senegal 1 people

18 India 1 people

19 France 1 people

Total 55 people

47

is in the form of letting the process of sufferings of the convicts ondeath row to prolong that is unethical and immoral. If a convict ondeath row is left without a certainty for a long period of time, he/she isactually also going through a spiritual torments, psychological torturesand mental repression.22

If we look further, it is not only the spiritual, psychological and mentalaspects of the convicts on death row that suffer, but they also experiencean invisible victimization. The consequence is that death penalty wouldlose its deterrent nature, because death penalty that is not being carriedout immediately would convey a wrong message to future criminals orperpetrators that might be charged with the same sentence.23 The convictson death row would also feel that they were already killed even beforethe execution. Everyday they count their remaining time, minute by minute.When would the night-shift guards would come knocking on their celldoor and tell them to do their last prayer before they were put in frontof the firing squad.

22 Prof. (Em). Dr. J.E. Sahetapy, S.H., M.A., Pidana Mati dalam Negara Pancasila [Death Penalty inPancasila State], (Bandung: PT. Citra Aditya Bakti, 2007), p. 68.

23 Ibid, p. 69.

CHAPTER 3POLICIES AND PRACTICES OF DEATH PENALTY IN THE REFORMATION ERA

49

Chapter 4

The Right to Life:Non- Derogable Constitutional

Rights

Human rights have become a mainstream of world civilization. Thisachievement is the peak of the struggle for humanity that has beenblossomed since the human civilization, both at the level of thought andat the level of social life practices. The thinking of human rights couldbe traced back to the ancient Greek era, both in the context of theobjectives and main orientation of social life (state) and as a right to befree from any oppression.24 On the other hand, the practices of humanrights violation also became the dark side of human civilization becauseof the barbaric violent acts, civil wars and oppressions by the states. Thehistorical experience of mankind raised a consciousness about and anacknowledgment of human dignity as well as the rights that are adheredto every single human being on the grounds of freedom, justice andworld peace.

The adoption and proclamation of Universal Declaration of Human

24 Plato (427 – 348 BC) developed the first thinking on the universalism of ethicalstandard, which required same treatment for everyone, both citizens or not. Aristoteles(384 – 322 BC) countlessly discussed about the importance of values, justice, andrights within society. Sophocles (495 – 406 BC) raised an early thinking on individualrights not to be oppressed by the state. Darren J. O’Byrne, Human Rights: An Introduction,(Delhi: Pearson Wducation Limited, 2003), p. 28.

50

INVEIGHING AGAINST DEATH PENALTY IN INDONESIA