Interorganisational relations and effectiveness in a developing housing policy field

Transcript of Interorganisational relations and effectiveness in a developing housing policy field

Pergamon HABITAT INTL. Vol. 20. No. 2, pp. 253-264, 1996

Copyright © 1996 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved

1}197-3975/96 $15.(X) + ().IX)

0197-3975(95)00061-5

Interorganisational Relations and Effectiveness in a Developing

Housing Policy Field

AMBE J. NJOH Unive~i~ofSouth Horida, Tampa, USA

ABSTRACT

The study deals with the problem of administrative capacity in housing policy implementation in less developed countries. Specifically, interorganisational relations as a strategy for improving administrative effectiveness are examined. The main question addressed is as follows: 'is the positive association between interorganisational relations and effectiveness found by studies in advanced countries tenable in the context of housing policy administration in developing countries?' Employing data on interorganisational relations amongst housing policy organisations in Cameroon, it is found that the relation is also tenable in the context of a developing country. A secondary question of interest in the study is as follows: 'what is the relative strength of association between various modes of interorganisational relations and organisational effectiveness?' It is found that the more intense the mode, the stronger the association.

INTRODUCTION

Organised efforts on the part of national and international institutional bodies to improve housing conditions in less developed countries (LDCs) is a relatively new phenomenon. Until the late 1960s, the prevailing philosophy within the development community viewed housing as a 'consumptive' activity deserving of no major investment on the part of international development agencies and national governments in LDCs. During the early 1970s, this philosophy was seriously challenged by the empirical findings of researchers such as Charles Abrams, John F.C. Turner, and William Mangin and later, United Nations agencies such as the International Labour Organisation and World Health Organisation, which documented the enormous contribution housing makes to economic, social and psychological development in developing countries. Since then, there has been a tremendous increase in the amount of resources and number of organisations committed to the housing sector in these countries. Despite this, the housing problem - - that is, the problem of quantitative and qualitative deficits in housing - - in LDCs remains a cause for concern. This is partially due to administrative or institutional weaknesses, particularly the

Correspondence to: Ambe J. Njoh, University of South Florida, 421)2 East Fowler Avenue , Tampa , FL 33620, USA.

253

254 Ambe J. N.ioh

inability of housing policy organisations (HPOs) to implement housing policies once they have been enacted.l

From an intuitive and theoretical perspective, one of the most promising of the remedies to this problem that have been suggested in the literature is interoganisational relations. The effectiveness theory of interoganisational relations holds that organisations, particularly those operating within a common policy field, can significantly enhance their performance by interacting more frequently with one another. This is because such interaction not only permits organisations to obtain otherwise scarce and non-substitutable resources, but also diminishes the possibility of interorganisational conflict and the unnecessary duplication of function.

Although some empirical studies in advanced nations have substantiated this theoretical construct, 2 it is yet to be adequately explored in the context of developing countries. Thus, the grounds for extolling and often recommending interorganisational relations as a viable strategy for promoting organisational effectiveness in developing countries, 3 it would appear, are simply intuition, theory and a belief that what works in advanced nations can do likewise in LDCs. However, experience reveals that these grounds are shaky at best. Witness, for instance, the intuitively and theoretically appealing Weberian model of bureaucracy, which has worked so well in advanced nations but has been ineffective in LDCs. We therefore contend that unless the workability of any strategy originating in the developed world, no matter its intuititve and theoretical appeal, has been tested in the context of developing countries, its utility in the latter is questionable.

This is the underlying premise of the present study. Particularly, the study seeks to empirically verify the effectiveness theory of interorganisational relations in the context of housing policy administration in a developing country, Cameroon. The study further seeks to determine the relative impact of various interorganisational relations modes on organisational effectiveness.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND STUDY CONTEXT

Theory Studies on interorganisational relations generally fall under the rubric of works visualising organisations as essentially open systems, which are inextricably intertwined with their external environment. Organisational environment and interorganisational relations are thus important terms in the context of this study.

As used here, the external environment of any organisation consists of elements which (a) reside beyond the external boundaries of the organisation; (b) can condition the organisation; and (c) can in turn be conditioned by it. 4 This is sometimes alluded to as the task environment 5 or the relevant environment, 6 to distinguish it from the general environment, which encompasses everything else in any given organisation's universe save the organisation itself. 7 The most important element of any organisation's relevant environment for the purpose of the present study comprises other organisations with which the organisation must interact in order to function.

Within the present context, interorganisational relations refer to the wide range of contacts social organisations make with one another. These contacts may be made through a variety of media such as the telecopier (facsimile), telephone, radio, television, newspaper, public bulletin board and the mail. The contacts may also be made in person through, for example, interagency conferences

lnterorganisational Relations and Effectiveness in a Developing Housing Policy Field 255

or meetings. 8 The question that has engaged students of interorganisational relations over the years has to do with the impact of these contacts on organisational effectiveness. Defining interorganisational relations in terms of an organisation's dependence on its environment, some 9 contend that as dependence increases, so do constraints on the organization's ability to function. This, in effect, renders organisational management extremely difficult. Seen in this light, the impact of interorganisational relations, or more generally, organisation-environment relations, on organisational effectiveness is negative. The negative impact of organisation-environment relations has also been discussed in terms of the costs of such relations to the organisation(s) involved. 10 Others 11 hold that the effect of organisation-environment relationships, particularly interorganisational relations, on organisational effectiveness is positive. This argument is rooted in a recognition of the fact that the resources necessary for organisational functioning are usually in short supply. Thus, an organisation is often compelled to interact with another organisation by the need to increase its resource base. 12 Witness, for instance, the case of inter-library loan programmes that permit libraries in developed countries to borrow from member libraries the books they do not possess but need in order to satisfy the demands of their clientele. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, interorganisational relations reduce the possibility for cross-purpose co-ordination and the unnecessary duplication of efforts. This is because, by interacting (even if such interaction entails no more than simply talking to each other), organisations are likely to be more familiar with each other's operations and areas of jurisdiction.

That there are two diametrically opposed views with regards to the impact of interorganisational relations on organisational effectiveness signifies a need for further studies on the subject. To be sure, empirical studies on organisation- environment interaction are not in short supply. However, extant studies have traditionally been concerned with interactions between a focal organisation and other organisations in its relevant environment. 13 Only a handful have attempted to explore the link between interorganisational relations and organisational effectiveness. 14 Even studies in this latter category are seriously deficient in one important respect; they fail to explore the relative impact of different modes of interorganisational relations on organisational effectiveness. Furthermore, these studies have been conducted almost exclusively in advanced nations.

Thus, there is a paucity of knowledge not only on the nature and relative impact of interorganisational relations on organisational effectiveness, but also on the extent of interorganisational relations in LDCs. The recognition of this paucity is an important rationale for the present study. The study specifically addresses three fundamental questions. First, is there a link at all between interorganisational relations and organisational effectiveness in the context of housing policy administration in a developing nation? Such a link, as mentioned earlier, has been suggested by organisational studies in advanced nations. Second, if a link exists, what is its nature (positive or negative)? Finally, what is the relative impact of interorganisational relations variables or different modes of interorganisational interaction, on organisational effectiveness in a developing housing policy field?

Each of these questions has far-reaching implications for housing and development policy administration in Cameroon in particular and LDCs in general. For example, should empirical evidence support a positive relationship, it would be necessary for authorities to encourage and in fact, actively promote interorganisational relations amongst housing policy organisations in particular and development policy organisations in general, as a means of improving their performance. However, if a negative relationship is uncovered, discouraging interorganisational interaction would be necessary to attain identical results. In the event that interorganisational relations are found to have no effect

256 Ambe J. N.ioh

whatsoever on organisational effectiveness, it would not be necessary to either promote or discourage interorganisational relations.

Furthermore, findings on the relative impact of each interorganisational relations mode on organisational effectiveness can be very informative to institution builders in the housing field in particular and the development policy field in general. Such findings can provide information necessary to rank-order the various modes of interorganisational relations as it is highly unlikely that all the modes command equal importance as far as their impact on organisational effectiveness goes.

Study context

Our attempt to explore the question involved organisations in the housing policy field in Cameroon. The field comprises a wide range of organisations operating in various capacities and at various territorial levels: city or township, divisional, provincial and national.

The focus was particularly on agencies involved in the country's residential development process. We refer to these agencies as housing policy organisations (HPOs). The HPOs of concern are those that were directly involved in the private residential development process in the following urban centres: Limbe, Kumba, Bamenda and Mbengwi. Included in this group are:

(1) the Divisional Service of Town Planning and Housing; (2) the Divisional Service of Surveys; (3) the Divisional Service of Lands; (4) the Divisional Service of Health; (5) the Local Government Council; (6) the Divisional Office; (7) the National Electricity Corporation (Societ~ Nationale d'Electricit~ du

Cameroun, SONEL); and (8) the National Water Corporation (Societ~ Nationale de l'Eau du Cameroun,

SNEC).

These organisations possess some peculiar characteristics that are worth noting. In the first place, they are part of a highly centralised administrative system, and each is a unit of a larger organisation or ministerial body at the national level. Secondly, they are all public organisations, with the exception of SONEL and SNEC, which are both para-public agencies. Thirdly, they are required by law to report not only to their superiors in the national capital but also to the Senior Divisional Officer or the official representing the state's interest at their territorial level of operation. Furthermore, Presidential Decree No. 76-166 of 27 April 1976, which established the terms and conditions of managing national lands, requires each of the organisations to be represented on the local Land Consultative Board.

Thus, a certain, albeit small, degree of interorganisational interaction amongst the organisations is mandatory. A significant proportion of the interactional episodes observed amongst the organisations and/or reported by their heads appears to be out of the need to deal with the problem of resource scarcity. One such episode involved the joint utilisation of infrastructure. For example, the acute shortage of government-owned buildings in the City of Limbe led the Ministry of Town Planning and Housing to house its divisional departments of Town Planning and Housing, Surveys, and Lands, three housing policy organisations, in a single rented two-storey unit. Another involved the inter- organisational exchange of personnel. Technicians of the Divisional Service of Town Planning and Housing are often borrowed through informal arrangements

lnterorganisational Relations and Effectiveness in a Developing Housing Policy Field 257

by the Local Government Council to conduct building/site inspections. This was the case especially in the cities of Bamenda and Limbe.

Therefore, a considerable degree of interaction beyond that required by mandates takes place amongst the housing policy organisations. To be sure, the level or degree of such interaction differed by organisation and organisational network. Why this was the case, and in fact why the agencies interacted at all, are questions that fall beyond the scope of the present study. As stated above, the study seeks mainly to determine the relationship between these interactions and organisational effectiveness.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data sources

The study is based on primary data generated through two multiple choice questionnaires (Questionnaire I and Questionnaire II), administered between 10 July and 31 August 1989. Questionnaire I comprised a self-administered survey instrument addressed to the heads of 32 sampled housing policy organisations 15 in four urban centres 16 in Cameroon. Questionnaire II was a researcher- administered instrument addressed to 127 of all landlords (clients of HPOs) who undertook (residential) construction projects in the sampled urban centres during the 3-year period ending in June 1989. A very high response rate was registered in both cases. More specifically, 29 (91%) of the 32 questionnaires addressed to heads of HPOs, and 113 (89%) of the 127 addressed to clients of these agencies, were completed, rz

VARIABLES AND MEASUREMENTS

Two main variables, organisational effectiveness (EFFECT), the dependent variable and interorganisational relations (CONTACT), the independent variable, were examined.

The dependent variable, organisational effectiveness

Organisational effectiveness (EFFECT) was operationalised in terms of an organisation's ability to satisfy its clients. Measurement of this variable was made possible by a three-point scale, the 'Satisfaction Scale'. This scale was designed to measure consumer or client satisfaction. The alternative multiple choice questions in this connection were included on Questionnaire II. The questions asked housing service consumers to indicate the extent to which they were satisfied with each housing policy organisation given: (a) how long it takes (TIME) the housing policy organisation or agency to provide a requested service/good, (b) the cost (COST) of the service, (c) the number of trips (TRIPS) the consumer had to make to the housing agency in order to obtain the service, (d) the amount of information (INFORM) provided to enable the consumer secure the service and the quality (QUALITY) of the service.

For each of these effectiveness dimensions, the respondent was required to choose one of three possible levels of satisfaction namely, 'unsatisfied' (US), 'somewhat satisfied' (SS), and 'satisfied' (SA). The effectiveness score for each agency on any given dimension was obtained through the following four steps:

(1) multiplying by zero (0) the percentage of all clients stating that they were unsatisfied with the agency on that dimension;

(2) multiplying two (2) the percentage indicating that they were somewhat satisfied with the agency on the same dimension;

258 Ambe J. N]oh

(3) multiplying by three (3) the percentage of clients stating that they were satisfied with the agency on the given dimension; and

(4) computing the sum of steps (1-3). In mathematical terms,

EFS D = ( % C u s D x 0) "1- ( % C s s D x 2) + ( % C s A D X 3)

where EFS D = effectiveness score on a given dimension; % C u s D = percent of clients 'unsatisfied' with an agency on a given dimension; %CssD = percent of clients 'somewhat satisfied' with an agency on a given dimension; and %CsA D = percent of clients 'satisfied' with an agency on a given dimension.

As an illustration of this formula in use, let us consider a hypothetical agency, M and its score on the effectiveness dimension, TIME. Assume that 20% of M's clients stated that they were 'unsatisfied' with it with respect to this dimension, while 35.2% stated they were only 'somewhat satisfied' with it and 44.8% said they were 'satisfied' with the agency on the very dimension. The agency's effectiveness score with respect to TIME will therefore be:

EFSTIME = (20 X 0) + (35.2 X 2) + (44.8 X 3) = 204.80.

The general formula for obtaining individual agency effectiveness score on the consumer or client satisfaction scale can thus be stated as follows.

WIS 0 q- W2S 1 -b W3S 2 . . . "1- W n s e

where W 1, W 2, W3, . . . W n are the weights or coefficients attached to the satisfaction levels S 0, S 1 . . . S e, such that W 1 < W 2 < W 3 . . . < Wn.18

The total effectiveness score on client satisfaction for each agency was computed by adding up all the scores on the different dimensions on which satisfaction was gauged. That, is,

EFSToT = EFSTIME q- EFSTRIPS q- EFScosT + EFSINFORM q- EFSQuALITY.

The independent variable, interorganisational relations (CONTACT)

This was operationalised in terms of the contacts organisations operating in the same policy field make with each other. After previous researchers, 19 items were included on Questionnaire I to generate information on the frequency of letter writing (LETTER) , meetings (MEET), joint activities (COOP), staff borrowing/lending (STAFF), equipment borrowing/lending (EQUIP) , the joint utilisation of resources (SHARE) , and the exchange and/or joint utilisation of infrastructure (SPACE), amongst housing policy organisations during the study period. 20

The intensity of such activities or interorganisational interaction was quantified as follows. An agency earned one point for each count of involvement in any one of these interorganisational episodes. For any given agency, the sum of these points then constituted its composite score on contact (CONTACT) or intensity of interorganisational relations.

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

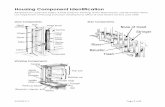

Initially, we computed the number of times each mode of interorganisational relations was utilised by each agency (Table 1). We note that the most intensely utilised mode of interorganisational relations is letter writing (LETTER). This was followed by meetings and committees (MEET), staff exchange (STAFF),

Interorganisational Relations and Effectiveness in a Developing Housing Policy Field

Table 1. lnterorganizational contacts by mode by agency

259

Agency LETTER MEET SPACE EQUIP STAFF COOP SHARE CONTACT

TPH Limbe 1086.0 19111.0 0.0 36.0 85.0 3.[) 30.0 3150.0 Health Limbe 0.0 55.0 0.0 145.0 118.0 5.0 0.0 323.0 D.O. Limbe 947.0 183.0 95.0 150.0 I(X).0 540.0 100.0 2115.0 Council Limbe 3536.0 51.0 0.0 24.0 36.0 31.0 9.9 3687.0 SONEL Limbe 321.0 1390.0 0.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 1714.0 SNEC Limbe 117.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 117.0 TPH Kumba 926.0 2112.0 35.0 15.0 20.11 51.0 0.0 3159.0 Lands Kumba 779.0 345.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 98.0 1222.0 Survey Kumba 857.0 1257.0 0.0 6.0 9.0 51.0 0.0 2180.0 Health Kumba 17.0 2.0 4.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 23.0 Council Kumba 305.0 84.0 17.0 20.0 15.0 0.0 0.0 441.0 SONEL Kumba 57.0 87.0 0.0 1.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 145.0 SNEC Kumba 81.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 81.0 TPH Bamenda 629.0 653.0 0.0 5.0 15.0 10.0 0.0 1312.0 Lands Bamenda 479.0 1215.0 72.0 38.0 0.0 359.11 45.0 2208.0 Survey Bamenda 194.0 1044.0 0.0 30.0 0.0 750.0 0.0 2018.0 Health Bamenda 170.0 54.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 224.0 D.O. Bamenda 1040.0 920.0 0.0 0.0 153.0 485.0 0.0 2598.0 Council Bamenda 717.0 76.0 0.0 54.0 83.0 5.0 0.0 935.0 SONEL Bamenda 262.0 39.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 301.0 SNEC Bamenda 60.0 22.0 0.0 15.0 9.0 6.0 0.0 112.0 TPH Mbengwi 2247.11 1056.0 3.0 36.0 21.0 35.0 0.0 3398.0 Lands Mbengwi 241.0 252.0 73.0 114.0 36.0 82.0 0 798.0 Survey Mbengwi 1170.0 54.0 2.0 44.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 1270.0 Health Mbengwi 66.0 16.0 0.0 0.0 l l0.0 0.0 0.0 192.0 D.O. Mbengwi 404.0 183.0 0.0 247.0 0.0 4.0 0.0 838.0 Council Mbengwi 1131.0 385.0 54.0 282.0 578.0 36.0 0.0 2466.0 SONEL Mbengwi 13.0 51.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 64.0 SNEC Mbengwi 32.0 5.0 3.0 17.11 0.0 0.0 0.0 57.0

Sum 17884.0 13501.0 358.0 1282.0 1388.0 2453.0 282.0 37148.0

co-operative endeavours (COOP), the exchange of equipment (EQUIP), the joint utilisation of resources (SHARE) and the exchange of infrastructure (SPACE), in that order. Table 2 shows the total effectiveness score (EFFECT) and effectiveness score on each of the five housing service dimensions by agency.

To verify the relationship between organisational effectiveness and inter- organisational relations, we first regressed the independent variable, CONTACT on the dependent variable, EFFECT [see equation (1) below]. Then, we developed seven bivariate regression models comprising EFFECT as dependent variable in each case and as independent variables the following: EQUIP, LETTER, MEET, SPACE, STAFF, COOP and SHARE. Finally, these independent variables and the dependent variable were incorporated into a single multivariate regression model [see equation (2) below]. The model generated by regressing CONTACT on EFFECT is as follows:

EFFECT = 937.741 + 0.078 CONTACT (1)

r 2 = 0.154; SE = 0.035; t = 2.220, significant at P ~< 0.05, DF = 28. The model is statistically significant (P ~< 0.05). This suggests that inter-

organisational relations is, as expected, a significant predictor of organisational effectiveness. The coefficient of determination (r 2) associated with the model is 0.154. This implies that at least in the case of the agencies examined in this study, interorganisational relations, operationalised in terms of interorganisational contacts (CONTACT), accounts for approximately 15% of the variability in organisational effectiveness (EFFECT), operationalised in terms of client satisfaction in housing policy administration.

260 Ambe J. Njoh

Table 2. Effectiveness score by agency

Effectiveness dimension

Agency TIME TRIPS COST QUAL. INFORM Effect score

TPH Limbe 239.5 242.9 220.9 244.5 214.1 1161.9 Lands Limbe* 207.5 196.1 216.0 207.5 181.3 1008.4 Survey Limbe* 200. I 211.2 168.0 229.7 214.9 1023.9 Health Limbe 210.7 228.5 212.6 242.9 192.7 1087.4 D.O. Limbe 226.2 236.8 242.8 266.7 205.6 1178.1 Council Limbe 142.9 135.7 169.0 171.3 167.9 786.8 SONEL Limbe 224.0 232.0 156.0 222.9 204.0 1038.9 SNEC Limbe 206.5 212.5 173.5 229.3 177.7 999.5 TPH Kumba 257.4 248.9 226.6 251.0 219.1 1203.0 Lands Kumba 191.5 225.0 172.1 234.0 275.0 1097.6 Survey Kumba 247.5 246.0 186.0 248.0 217.5 1145.0 Health Kumba 271.7 269.5 260.6 260.8 217.5 1280.1 D.O. Kumba* 237.3 227.3 243.9 237.1 192.1 1137.7 Council Kumba 127.5 126.6 115.9 191.4 182.4 743.8 SONEL Kumba 107.3 110.0 76.1 158.4 157.2 609.0 SNEC Kumba I10.0 107.3 80.6 169.2 146.6 613.7 TPH Bamenda 171.9 131.2 163.3 181.5 150.0 797.9 Lands Bamenda 197.0 221.0 206.8 231.2 212.6 1068.6 Survey Bamenda 224.0 219.0 174.2 212.6 262.0 1091.8 Health Bamenda 200.0 234.3 220.6 250.1 225.1 1130.1 D.O. Bamenda 248.2 236.6 225.2 261.3 231.5 1202.8 Council Bamenda 231.4 219.0 161.2 243.8 175.6 1031.0 SONEL Bamenda 121.8 118.9 65.5 193.0 215.5 714.7 SNEC Bamenda 103.2 112.7 84.4 190.5 206.2 697.0 TPH Mbengwi 289.5 284.2 279. I 278.9 284.2 1415.9 Lands Mbengwi 242.2 215.8 227.8 273.7 263.3 1222.8 Survey Mbengwi 257.7 237.7 242.1 268.4 268.3 1274.2 Health Mbengwi 247.3 247.4 242.2 247.3 257.9 1242.1 D.O. Mbengwi 271.2 254.5 281.8 241.5 250.0 1299.0 Council Mbengwi 257.8 268.4 242.2 231.4 226.4 1226.2 SONEL Mbengwi 125.0 100. i 143.9 225.0 193.0 787.9 SNEC Mbengwi 161.7 123.2 138.6 192.5 169.4 785.4

*Excluded from analysis because questionnaire was not returned.

Table 3. Summary results for bivariate regression models with effect as dependent variable

Variable b r 2 t SE DF

(1) EQUIP 991.673 0.1552 2.23** 0.541 28 (2) MEET 986.053 0.1357 2.06"* 0.069 28 (3) STAFF 1018.32 0.1)75 1.48' 0.387 28 (4) SPACE 1017.36 0.0671 1.39" 1.633 28 (5) LETI'ER 1003.21 0.0469 I. 15 0.056 28 (6) COOP 1023.96 0.045 1.13 0.228 28 (7) SHARE 1033.87 0.0195 0.73 1.66 28

*Significant at P < 0.10. **Significant at P < 0.05.

The bivariate models provide information for assessing the relative strength of the seven interorganisational relations modes (taken one at a time), as predictors of organisational effectiveness. The relevant statistics associated with each of these models are presented on Table 3. We note that EFFECT is positively related to each of the interorganisational relations modes. In comparing the coefficient of determination (r 2) associated with each of these modes, we further note that the strongest predictor of organisational effectiveness is EQUIP, the interorganisational exchange of equipment (r 2 = 0.1552). The second strongest predictor is interorganisational meetings and committees (MEET), which has a

lnterorganisational Relations and Effectiveness in a Developing Housing Policy Field 261

coefficient of determination of 0.1357. Both models are statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

The models containing the rest of the independent variables are not statistically significant. The foregoing rank-order structure assumes that the interorganisa- tional relations modes are employed one at a time. In practice, however, one mode of interorganisational relations is hardly ever employed in exclusion of the others; nor is there any reason to do so. Therefore, it is also, if not more, important to explore the rank-order structure of the various modes of interorganisational relations when all of them are built into a single predictive model. In this case, the behaviour of any regressor variable is contingent upon the behaviour of the other regressor variables in the model.

We thus examine the multivariate model incorporating as dependent variable, EFFECT and the seven interorganisational relations modes as independent variables. The model shows that:

E F F E C T = 898.161 + 1.366EQUIP + 0 .086COOP + 0.131MEET (SE) (0.837) (0.256) (0.076) [tl ll.632] [0.334] [1.734]*

+ 0 .468SHARE - 0 . 4 6 2 S P A C E - 0.052STAFF + 0.023LETYER (1.198) (2.237) (0.519) (0.060) [0.244] (-0.236] (-0.099] [0.3821

(2)

R2 = 0.293. Significant at P < 0.05; DF = 28.

An analysis of the multivariate model provides some very insightful results. First, we note that five of the independent variables, MEET, EQUIP, LETFER, COOP, and SHARE, are in conformity with our hypothesis as they are positively associated with organisational effectiveness. We also note that one variable, interorganisational meetings (MEET), has a statistically significant relationship (P ~< 0.05) with organisational effectiveness (EFFECT). Two variables, the interorganisational exchange of personnel (STAFF) and the exchange of infrastructure (SPACE) are negatively related to organisational effectiveness. The nature of this association is contrary to our expectation. A plausible explanation for this somewhat unusual relationship is provided below.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

The major finding of this study is that interorganisational relations is positively associated with organisational effectiveness in the housing policy field of a developing nation. This suggests that increasing the frequency of interaction amongst housing policy organisations is likely to improve housing policy organisa- tional effectiveness. To be sure, the limited scope of our analysis prevents us from concluding that the link uncovered is causal. The notion of causation, it must be emphasised, cannot derive solely from statistical analysis. In fact, as Kendall and Stuart21 point out:

A statistical relationship, however suggestive, can never establish causal connexion: our ideas of causation must come from outside statistics, ultimately from some theory or other.

Yet, as pointed out earlier, only a few attempts have been made to understand the link between interorganisational relations and organisational effectiveness. Our knowledge of the subject at this point is thus based largely on theory. The effectiveness theory of interorganisational essentially holds that inter-

W 10~|~

262 Ambe J. Njoh

organisational relationships improve organisational effectiveness by enabling organisations to expand their resource bases, reduce the chances of waste, effort duplication and conflict, and by reinforcing their ability to deal with indivisible problems and uncertainty. The finding uncovered by this study provides empirical support to this theory.

The finding is consistent with that of Van de Ven's 22 one of the few that has examined interorganisational relationships and effectiveness. He found a strong positive association between organisational effectiveness and such interorganisational relations variables as mutual dependence, awareness, communication and resource exchange. It would appear, according to the present findings, and as others 23 have suggested, that more intensive interorganisational relationships tend to have a stronger correlationship with organisational effectiveness. Equipment exchange, for instance, was found to be one of the two modes of interorganisational relations that had a significant (P < 0.05) positive relationship with organisational effectiveness in a bivariate model. The other was meetings/committee participation. Thus, in a bivariate situation, a more intense mode of interorganisational interaction, equipment exchange emerged as a better predictor of organisational effectiveness. This was also the case in the multivariate model, where equipment exchange and meeting/committee participation, as modes of interorganisational relations, emerged respectively as the best and second best predictors of organisational effectiveness.

The unexpected findings of the study are the negative associations between staff exchange and organisational effectiveness and between the interorganisa- tional exchange of infrastructure and organisational effectiveness. It is worth- while noting that these relationships are not statistically significant. Thus, it is possible that these may be spurious relationships caused by a problem in research design. For instance, while there was an item aimed at eliciting information on the frequency of staff exchange by housing policy organisations, none was intended to determine the purpose for which staff were borrowed. In effect, it is plausible, because of the possibility of organisations belonging to multiple interorganisational networks, that an agency could borrow personnel from within the housing policy field to use in a different field. In fact, during the data collection phase of the study, officials within housing policy agencies revealed that in Cameroon it is common practice for the Department of Health to borrow staff from other public agencies including housing policy organisations to help in activities such as 'immunization drives'. By so doing, the Health Department's effectiveness in the medical policy field is increased while its effectiveness, along with that of the other agencies, in the housing policy field is decreased. The same can be said of office space that is borrowed by agencies within the housing policy field and used for purposes other than housing policy administration.

IMPLICATIONS OF FINDINGS AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

Institutional weakness is increasingly being recognised as a leading impediment to housing in LDCs in particular, and development planning in general. This problem is compounded by the fact that there is a shortage of useful ideas on how to strengthen the administrative capacity of housing/development policy organisations. In view of this shortcoming, the World Bank devoted its 1983 issue of 'World Development Report' to issues of management improvement in LDCs. In a similar effort, the United Nations Centre for Regional Development (UNCRD) commissioned a study entitled, 'Managing Urban Development: Services for the Poor' in 1984. The importance of institutional effectiveness to the effective implementation of housing policy in developing countries is widely

lnterorganisational Relations and Effectiveness in a Developing Housing Policy Field 263

acknowledged by most of the contributors to a recent highly-praised text on 'Shelter, Settlement and Development' edited by Professor Lloyd Rodwin. 24

That issues of institutional development are currently at, or close to, the top of the development policy agenda 25 underscores the significance of the present study. The study's primary contribution resides mainly in the fact that it breaks new grounds in the field by empirically verifying hitherto statistically untested assumptions about the relationship between interorganisational interaction and organisational effectiveness.

The confirmation of a positive association between these two variables in the housing policy field suggests that development planners can no longer afford to adopt a passive attitude in dealing with the issue of organisation-environment relationships particularly, interorganisational relationships (IOR). Such passivity has dominated housing/development planning practice in the past and manifests itself in housing and development policies that have relied indiscriminately on Western models while ignoring the local environment in which housing/ development policy implementing agencies operate.

Rather, efforts must be made not only to actively encourage interorganisational relationships, but also to seriously seek means to promote such relationships. These efforts will involve not only authorities in developing countries but also international donor-agencies, bilateral and multilateral organisations. One of the many things that can be done by these bodies is supporting studies aimed at uncovering strategies for promoting interorganisational relations. In this regard, serious efforts should be made to verify the validity of IOR-promoting strategies that have already been proposed in the relevant literature. It has been suggested for instance, that interagency interaction can be promoted by: 26

1) locating complementary agencies within close proximity of each other; 2) ensuring that heads of complementary agencies are of equal or about equal professional ranking; and 3) ensuring that agencies operating in common policy fields are familiar with each other's activities and programmes.

The importance of testing the validity of these propositions cannot be overstated. Recommendations regarding which IOR-promoting strategy needs to be pursued under what circumstances depends on an adequate understanding of their merits and relative impacts on organisational effectiveness. Authorities in developing nations particularly must understand that unless an atmosphere conducive to the free and uninhibited interaction amongst public, para-public, private and other agencies exists, all efforts to promote interorganisation relations in any particular policy field are unlikely to yield any utility.

Acknowledgement - - This study draws extensively from the author's doctoral work. The author acknowledges the assistance of Michael Mattingly, who supervised the work, Patrick Wakely, Professor Nigel Harris, and the entire faculty and staff of the Development Planning Unit, Bartlett School of Architecture and Planning, University College London, for their generous support. The author would also like to extend his heartfelt appreciation to the journal's editor, Professor Charles L. Choguill and the anonymous reviewers whose suggestions were valuable in revising this article.

NOTES

1. For identical arguments see J. Van der Linden, The Sites and Service Approach Reviewed: Solution or Stopgap to the Third World Housing Shortage? (Gower, Brookfield, Vermont, t986); A.J. Njoh, "Interorganizational Relationships and Effectiveness in the Housing Policy Field: The Institutional Development of the Housing Delivery System in Cameroon", unpublished PhD Thesis, University of London (1990); A.J. Njoh, "'The Effectiveness Theory of lnterorganizational Relations Explored in the Context of a Developing Nation", International Review of Administrative Sciences 59, 2 (1993), pp. 235--250.

2. See R.L. Warren, "The Interorganizational Field as a Focus for Investigation", Administrative Science Quarterly 12 (1967), pp. 396-419; M.R. McKinney, "Organizational Dependence and Effectiveness in the Human Service Sector", unpublished PhD Dissertation, Rutgers University, New Brunswick,

264 Ambe J. Njoh

NJ (1986); C.L. Mulford, lnterorganizational Relations: Implications for Community Development (Human Science, New York, 1984).

3. See G. Honadle and L. Cooper, "Beyond Coordination and Control: an Interorganizational Approach to Structural Adjustment, Service Delivery and Natural Resource Management", World Development 17 (1989), pp. 1531-1541; S.G. Cheema, Urban Shelter and Services: Public Policies and Management Approaches (Praeger, New York, 1987); D. Rondinelli, Development Projects as Policy Experiments: an Adaptive Approach to Development Administration (Methuen, London, 1983); Van der Linden (1986), see note 1.

4. For more along this line of thought, see D. Katz and R. Kahn, The Social Psychology of Organizations (Wiley, New York, 1978); B.J. Hodge and W.P. Anthony, Organization Theory (Allyn Bacon, Boston, MA, 1984). F. Riggs, "The Ecology and Context of Public Administration: a Comparative Perspective", Public Administration Review 40 (1980), pp. 107-115.

5. For a comparison, see J.D. Thompson, Organizations in Action (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1967). 6. W.R. Dill, "Environment as an Influence on Managerial Autonomy", Administrative Science Quarterly

2 (1958), pp. 409-421. 7. For a comparison, see Katz and Kahn, (1978), see note 4. 8. Njoh (1993), see note 1. 9. F.E. Emery and E.L. Trist, "The Causal Texture of Organizational Environments", Human Relations

18 (1965), pp. 21-32; J.D. Thompson (1967), see note 5. 10. For a comparison, see H. Aldrich, "An Organization-Environment Perspective on Cooperation

and Conflict between Organizations in the Manpower Training System", in Anant Negandhi (ed.), lnterorganization Theory (Kent State University, Kent, OH, 1972) and R. Chambers, Rural Development: Putting the Last First (Wiley, New York, 1983), p. 25.

11. See, for example, R.L. Warren, "The Interorganizational Field as a Focus for Investigation", Administration Science Quarterly 12 (1967), pp. 396-419; P.M. Hirsch, "Organizational Effectiveness and the Institutional Environment", Administrative Science Quarterly 20 (1975), pp. 327-344; J. Molnar and D.L. Rogers, "Interorganizational Relations Among Development Organizations: Empirical Assessment and Implication for Interorganizational Coordination", unpublished paper, Center for Agricultural and Rural Development, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, Ames, IA (1982).

12. S. Levine and P. White, "Exchange as a Conceptual Framework for the Study of Interorganizational Relationships", Administrative Science Quarterly 5 (1961), pp. 583--601.

13. See, J. Pfeffer and G.R. Salancik, The External Control of Organization: a Resource Dependence Perspective (Harper & Row, New York, 1978); R. Hall, J.P. Clark, P. Giordano, P.V. Johnson and M. Van Roekel, "lnterorganizational Coordination in the Delivery of Human Services", in L. Karpik (ed.) Organization and Environment: Theory, Issues and Reality (Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, 1978). J.K. Benson, "The lnterorganizational Network as a Political Economy", Administrative Science Quarterly 20 (1975), pp. 229-249; C.B. Marrett, "On the Specification of Interorganizational Dimensions", Sociology and Social Research 56 (1971); C.L. Mulford, lnterorganizational Relations: Implications for Community Development (Human Sciences Press, New York, 1984).

14. See, A.H. Van de Ven, Assessing Organizations (John Wiley, New York, 1980); M.R. McKinney (1986), see note 2.

15. The HPOs sampled include: the divisional services of (1) Town Planning and Housing (TPH); (2) Survey; (3) Lands; (4) Health; (5) the Local Government Council (Council); (6) the Divisional Office (D.O.); (7) the National Electricity Corporation (Societe Nationale d'Electricite du Cameroun, SONEL); and (8) the National Water Corporation (Societe Nationale de l'Eau du Cameroun, SNEC).

16. The four selected urban centres include Limbe, Kumba, Bamenda and Mbengwi. 17. The high return rate was made possible by the fact that the questionnaires were personally- or

hand-delivered and picked up by the researcher. By so doing, unnecessary delays and the risks of misplacement of the questionnaires in the ineffective mailing system in the country were avoided.

18. Various combinations of scores were used to verify the tenability of the strategy. The results showed that the order remains unchanged as long as W v < W 2 < W 3 . . . W,~.

19. See, for example, M. Aiken and J. Hage, "Organizational Structure", American Sociological Review 33 (1968), pp. 912-930; Mulford (1984), see note 2; Marrett (1971), see note 13. J. Hage, "Towards a Synthesis of the Dialectic Between Historical-Specific and Sociological-General Models of the Environment", in L. Karpik (ed.), (1978), see note 13.

20. A 2- to 3-year period was considered reasonable time during which a residential building project could be completed. Clients who started the process less than 2 years prior to the study were therefore excluded. However, since our intention was to include only agencies with extensive familiarity with the local environment, a longer period, 4 years was considered logical. Thus agencies that had not served local clients for at least 4 years prior to the study, were eliminated.

21. M.G. Kendall and A. Stuart, The Advanced Theory of Statistics (Charles Griffin, New York, 1961).

22. Van de Ven (1980), see note 14. 23. See, for example, Mulford (1984), note 2; Molnar and Rogers (1982), see note 11. 24. L. Rodwin (ed.), Shelter, Settlement and Development (Allen & Unwin, London, 1989). 25. M. Wailis, Bureaucracy: its Role in Third World Development (Macmillan, London, 1989). 26. Njoh (1990, 1993), see note 1; W.W. Kovalick, "Improving Federal Interagency Coordination: a

Model Based on Microlevel Interaction", unpublished PhD dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA (1988).