A Study on Human Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation within ...

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation in Italy

Transcript of Human trafficking for sexual exploitation in Italy

8 Human trafficking for sexual exploitation in Italy

Ernesto Savona, Luca Giommoni and Marina Mancuso

This chapter focuses on human trafficking for sexual exploitation in Italy. Two Italian case studies are analyzed, applying the crime script approach. They have been provided by state prosecutors of two Italian provinces (Campobasso and Ancona) and are referred respectively to indoor and outdoor prostitution. Starting from the literature on this topic, the different stages of this crime (recruitment, transportation, exploitation and aftermath) are identified. From the analysis of the two arrest warrants, information on the actions and decisions of both traffickers and victims is linked to the stages of the crime. The added value of this work is the application of a methodological tool (script) not often used to examine human trafficking. This allows a concrete analysis of the vulnerabilities associated with the crime-commission process and the search for situational crime prevention measures that might target these vulnerabilities. Both research and policy implications are drawn at the end of the chapter.

Introduction

Human trafficking is often associated with a new form of slavery because it implies the exploitation of victims and the systematic violation of their human rights (Adepoju 2005: 77; Savona and Stefanizzi 2007: 5). Because of its serious-ness, in the last decades this crime has received great attention by international authorities and by the research and academic world with the aim of better under-standing its features and its dynamics. A definition of this global phenomenon is contained in the “Protocol to pre-vent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children,” a document drafted by the United Nations in 2000 that supplements the United Nations Convention against transnational organized crime. According to Article 3 of the Protocol:

[Human trafficking] shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, har-boring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other form of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of giving or receiving of payments or ben-efits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 140_Cognition and Crime.indb 140 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 141

The Article also specifies that “exploitation shall include, as minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs”. The main economies in which the highest incidence of this crime has been registered are the conventional market economies (people traf-ficked working in bars, restaurants, construction companies, factories and so on), the legitimate domestic service economy (people used as carers and domestic servants) and finally the criminal economies of the sex industry (both indoor and outdoor prostitution) (Aronowitz 2001: 172). Following the above defini-tion, human trafficking is a crime that involves different phases: recruitment, transportation and exploitation of the victims. These phases can be analyzed as a criminal process1 carried out without the informed and complete consent of the people involved as victims2 (Aronowitz 2009). This process involves many peo-ple: on the one hand the traffickers, and on the other the victims. The former are goal-oriented individuals able to identify specific market demands and provide a corresponding supply of people that can satisfy them. They are more or less organized according to the extent of the traffic: the more victims are moved from one area to another, the more organized the criminal group involved will be and vice versa. In many cases criminal networks of people connected to each other are the main structure identified3 (Iselin 2003; Picarelli 2009; Vermeulen, Van Damme and De Bondt 2010). The latter group involved in trafficking, the victims, are associated with high levels of risk: quite often they live in poor countries, have no job opportunities and a low level of education that make them vulnerable and hence easily controllable by traffickers (Limanowska 2002; Okojie, Okojie, Eghafona, Vincent-Osaghae and Kalu 2003). Once transferred and entered in the exploitation chain they suffer many physical and psychological problems. They are employed without any assistance and protection and are considered only as property by their exploiters (Beeks and Amir 2006). The abuse of victims happens mostly with sex trafficking, which is “the best known type of exploitation in Europe” (Van Liemt 2004: 20). Many studies have focused their attention on the general analysis of the phenomenon while others on its specific features associated to specific countries (Lebov 2010; Liu 2011; Van Duyne and Spencer 2011). In both cases the main aspects considered have been the phases required to commit the crime (Aronowitz 2009; Transcrime 2003; Vermeulen et al. 2010), the traffickers and the organizations involved in this crime (David and Monzini 2000; Picarelli 2009; UNODC 2009), the vic-tims and the problems associated with them (Limanowska 2002; Okojie et al. 2003), the routes used to carry out the illicit transportation of the victims (IOM 2005; Ministry of the Interior 2007; Motta 2008, 2010; Shelley 2010; Transcrime 2010; Unicri 2005), the causes and the consequences of this crime (Shelley 2010; US Department of State 2005; Zimmerman 2003) and finally the strategies to combat this crime (Aronowitz 2009; Bosco, Di Cortemiglia, Serojitdinov 2009; Friesendorf 2007). Despite this wide range of studies, there remain significant gaps in our knowl-edge around precise details of human trafficking (IOM 2009). Data collected are

_Cognition and Crime.indb 141_Cognition and Crime.indb 141 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

142 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

quite generic. The main data sources at global level are produced by international organizations that, using different points of view, give an idea of the diffusion of this crime, the gender of the victims, their nationality and the kind of exploitation most detected.4 For example, according to the US Department of State (2008), about 800,000 people are trafficked every year across international borders while according to the UNODC 70,000 victims are yearly trafficked in Europe for sexual exploitation (UNODC 2010: 16). These are mainly estimates, in some cases asso-ciated with illegal migration in general or with smuggling of migrants (Laczko and Gramegna 2003: 181). Also, when data or estimates focused on human traf-ficking have been produced, they present some limits connected to the nature of the crime. The first limit is the “dark figure” of under-reported crime. The fear of retal-iation for collaborating with law enforcement authorities and the fear of being considered an illegal migrant by these authorities produce low reporting levels (IOM 2005: 234). When the victims are included in the data it is because they have been registered by law enforcement and/or they have come in contact with social services and NGOs to receive assistance and protection (Kleemans 2011: 1). The second limit relates to data comparability. Data collected by different agencies are not comparable even if they have been collected by agencies operat-ing in the same country (in many countries a central data collection agency does not exist) (IOM 2009). This is caused by the different methodologies, languages and goals of the agencies.5 A low level of collaboration and a corresponding inad-equate sharing of information among them also adds to the problem (Bosco et al. 2009: 37; Salt 2000: 37). The lack of precise and comparable secondary data (macro) on the phenom-enon makes the script approach (micro) proposed in this chapter more valuable. It could help the focusing on different opportunities/vulnerabilities and the finding of situational prevention remedies. This chapter is an example of how macro and micro analyses could be combined for a better understanding of the phenomenon and finding more effective solutions against it.

Human trafficking and crime script

Human trafficking is a continuous process involving different and multiple deci-sions taken by a motivated and rational offender who weighs costs, benefits and efforts required to accomplish the crime (Cornish and Clarke 2008). Both the rational choice perspective and human trafficking have their roots in the economic field: the former translated the homo economicus concept into the reasoning criminal concept (Cornish and Clarke 1986), whereas the latter con-siders economic factors (e.g. unemployment, underemployment and economic difficulties) as the main push factors causing crime (Aronowitz 2001 and 2009; Bosco et al. 2009; Van Liemt 2004). Consistent with the rational choice per-spective, considering trafficking from an economic point of view emphasizes the high level of rationality of the traffickers involved. This crime seems to be ruled by free market laws: poor countries export (both legally and illegally) abundant

_Cognition and Crime.indb 142_Cognition and Crime.indb 142 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 143

unemployed resources and rich countries import and employ them in specific market sectors in which a high unsatisfied demand is registered (Shelley 2010). In order to understand the rationality behind any crime, Cornish (1994) pro-posed the concept of crime script. Thanks to this concept, borrowed from the cognitive sciences (Schank and Abelson 1977), it is possible to “identify every stage of the crime-commission process, the decisions and actions that must be taken at each stage, and the resources required for effective action to each step” (Cornish and Clarke 2008: 31). According to this definition, crime is an action that occurs at a specific time and place but it is only one event within the com-plete crime commission process. Before and after the criminal act there are other events and decisions vital to the crime (Cornish 1994). The analytical framework offered by the concept of crime scripts is a useful tool to organize the knowledge of a complex and structured behavioral sequence. Breaking down the complete crime process into scenes, and identifying actions, decisions and alternatives, cast (actors involved in the scene), responsible agencies and legislation involved in each scene, it is possible to identify the details associated to this crime. An in-depth analysis applying the rational choice perspective and script anal-ysis can help reveal both complexity and flexibility of the crime-commission process. The complexity is shown by dividing the crime into a series of steps and identifying the prerequisites and the facilitators of the single actions. To represent the flexibility in the crime commission (concept emerged especially in the study carried out by Lacoste and Tremblay 2003), Cornish adopted a series of cubes strung out along an axis. Each cube corresponds to a stage and each cube face corresponds to possible ways to carry out a stage. For example, a crime may be committed as a sequence of 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 (4 stages with 3 possible ways to carry out each stage) or by a sequence of 4 × 4 × 4 (3 stages and 4 ways to play each stage) (Tremblay, Talon and Hurley 2001: 561). Examining the stages of a crime, ways to play stages, actors and actions in each “cube face” (stage) leads to the identification of vulnerabilities in the crime-commission process and possible adaptations of the offender. Since the introduction of the crime script concept in 1994, several authors have applied this scheme to different criminal phenomena, including complex and organized crimes such as: infiltration of mafia organizations in the public construction industry (Savona 2010), stolen vehicles (Morselli and Roy 2008; Tremblay 2001), illegal waste smuggling (Tompson and Chainey 2011), hunting pattern of serial sex offenders (Beauregard, Proulx, Rossmo, Leclerc and Allaire 2007), employee computer crime (Willison and Siponen 2009), organized crime (Hancock and Laycock 2010), drug manufacturing (Chiu, Leclerc and Townsley 2011), adult child sex offenders (Leclerc, Wortley and Smallbone 2011). The popularity of this analytic method can be explained in a number of ways: it can be easily applied by all practitioners without requiring any form of training, par-ticular software or specialization; it helps in structuring and deepening knowledge and developing an organizational memory; it can provide a conceptual framework in cases where there are limited data; it permits a bottom-up and a top-down visu-alization of the crime commission process; it may facilitate the identification of

_Cognition and Crime.indb 143_Cognition and Crime.indb 143 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

144 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

opportunities for detection and prevention; and it may help in the individuation of flexible “spots” in the crime commission process, able to adapt quicker to law enforcement responses. It is proposed in this chapter that crime scripts can be successfully applied also to the study of human trafficking. Until now only one study applied crime script to human trafficking.6 This is surprising, given the shortage of quantitative data and focused analysis. Script analysis can provide the “zoom-in” necessary to develop a micro-analysis of this phenomenon, highlighting its complex dynamics and identifying vulnerabilities and opportunities exploited by traffickers. This is what this chapter attempts to do. In the following section the sources of data and the methodology adopted to carry out the analysis are described.

Application of the script analysis to trafficking in human beings for sexual exploitation: data sources and methodology

A crime script analysis must fulfill two conditions: first, it should be crime spe-cific and should not encompass the general offense category (i.e. not car theft, but car theft for resale, joyriding, etc.); second, it should analyze in depth the crime commission process providing an insight of it. To accomplish these conditions, suitable and proper data sources are needed. Reviewing the literature on crime script, the traditional data sources adopted are:

● in-depth interviews with offender or victim of the offense;● CCTV footage;● police investigations (wiretappings, warrants of arrest, judicial decisions).

The sources of data used in this chapter are two arrest warrants associated with Italian sex trafficking cases. This judicial material has been chosen because it contains a lot of information about the dynamics of the crime and the different phases to commit it. The two arrest warrants describe in detail all the passages and all the actions carried out by the traffickers and the victims in order to success-fully achieve the illicit goal. Thanks to these documents it is possible to obtain a relatively objective reconstruction of events, minimizing the distortions that might be contained in interviews of the criminals or victims involved. The wire-tappings reported give also an idea of the rules and the decisions taken from the beginning to the end of the criminal act. The arrest warrants considered refer to two recent judicial cases:

● Case study 1 deals with trafficking in human beings for sexual exploitation carried out in night clubs involving victims from Eastern Europe (especially Poland and Romania). This case was indicted by the Court of Campobasso (Molise region) in 2010.

● Case study 2 deals with trafficking in human beings for sexual exploita-tion carried out on the street involving victims from Nigeria. This case was indicted by the Court of Ancona (Marche region) in 2009.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 144_Cognition and Crime.indb 144 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 145

Both arrest warrants consist of approximately 500 pages describing the organiza-tions in detail and containing wiretap transcriptions, witnesses’ examination and other police activities. These cases have been considered because they refer to two main sex trafficking entrance flows in Italy: from Eastern Europe and from Nigeria (Transcrime 2010). Despite being both focused on sex trafficking, the two cases are different in a number of ways. They show two different modalities of sex trafficking developed in Italy and elsewhere. In the first case trafficking is carried out in nightclubs, so the focus is on indoor prostitution. In the second case trafficking is carried out on the street, so it refers to outdoor prostitution. Secondly, the nationalities of the victims and of the traffickers are different: in one case they are people from Eastern Europe and the offenders are principally Italians having contacts with Polish and Romanian brokers; while in the other case both victims and traf-fickers are Nigerian. A major female offender involvement is registered in this second case, given the high relevance of the Nigerian “madams,” women who, as those described in the paper written by Zhang, Chin and Miller (2007) on female participation in the Chinese criminal associations involved in human smuggling, manage the entire human trafficking process thanks to their wide social and rela-tional resources, to the reduced use of violence that characterizes this crime and to their gender affinity with the victims (Ministry of the Interior 2007). Finally the cases involve a different number of offenders (respectively 17 and 67). These differences can lead to diverse ways of committing the crime. The two cases have been analyzed using the script analysis proposed by Cornish (1994). More labels, not directly connected to those suggested by Cornish, have been selected using a particular graphic visualization that adds value to the understanding of the analysis. This will help to understand the continuous flow of actions that characterize crime script approach: when one finishes, another starts. This approach avoids the risk of representing the crime-commission process in a rigid and static way and the offenders as passive actors not directly connected to specific decisions and choices. In order to overcome these limits and to highlight the rationality of the subjects involved, the solution proposed here is to show all the activities committed, the decisions taken by offenders and the environmental factors influencing these decisions (opportuni-ties). This means that not only the track is described (single cubes concatenated to represent the minimum detail level of the crime process), but also the differ-ent ways used to carry out each scene. This aspect is important because in some cases, facilitators and impeding factors can influence the normal sequence of actions requiring fewer activities to be carried out in the same scene or forcing the offenders to implement additional actions to perpetrate crime. The steps con-sidered by this analysis are the following:

● identification of the stage process (what was defined as the cubes and that hereafter will be defined as stages);

● drawing for each stage the cast, activities, decisions, alternatives, comprising a complete process;

_Cognition and Crime.indb 145_Cognition and Crime.indb 145 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

146 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

● determination of opportunities and vulnerabilities within the crime commis-sion process exploited by the offenders;

● application of situational crime prevention techniques aiming at reducing the above mentioned vulnerabilities.

The first step is to identify the stages constituting the crime. As already mentioned, there are no settled terms even if most authors (Beauregard et al. 2007; Hancock and Laycock 2010; Morselli and Roy 2008; Savona 2009; Tremblay et al. 2001; Willison and Siponen 2009) adopted the subdivision proposed by Cornish (1994) and derived from cognitive sciences. This division usually entails the following stages: preparation, entry, pre-condition, instrumental pre-condition, instrumental initiation, instrumental actualization, doing, post-condition and exit. This subdivi-sion has been adapted case by case to different crime phenomena analyzed fixing the stages to the crime commission flow. Recently some authors (Brayley, Cockbain and Laycock 2011; Tompson and Chainey 2011) have argued that that following the cognitive sciences terminology could be misleading, and have proposed instead an ad hoc subdivision that does not take into account the items advanced by Cornish. This new proposal does not alter the script process but redistributes the action flow within the script with a terminology focused on the problem considered. Thus Brayley et al. (2011), for internal child sex trafficking, divided the crime commission process into find, groom and abuse. Tompson and Chainey (2011), for the illegal waste smuggling, divided the process into creation, storage, collection, treatment, transport and dis-posal. This review does not affect the meaning of script analysis but just proposes a different way to organize the knowledge. In this chapter existing terms describ-ing the different stages of the trafficking in human beings for sexual exploitation have been used. These are: recruitment, transportation and exploitation. To these three stages a fourth stage has been added, the so-called aftermath. This stage considers the actions taken after the crime commission that, as Cornish writes, “may include further crimes and their sequel” (Cornish 1994: 155). Both case studies will be divided according to these stages.

Trafficking in human beings for sexual exploitation in Italy

In this section the two crime scripts are presented and represented in a flow chart. This approach highlights the conditions allowing crime to be committed, the alter-natives, and the spots where the offenders can readapt quicker. This means a deep focus on offender involvement in the crime commission process, as main actor, but also the role played by the others involved in the scenes, as supporting actors or counterparts. Unlike other authors (Brayley et al. 2011), we also considered the actions undertaken by the victims. Although in the majority of cases these are not criminal actions, they are critical to the crime commission. Without the decisions of victims (even if not fully informed) crime would not take place.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 146_Cognition and Crime.indb 146 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 147

Case study 1: Sex trafficking from Eastern Europe to Italy

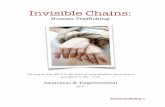

The script analysis referring to the first case study7 is represented as a flow of concatenated actions producing the different phases of the crime (see Figure 8.1 and Table 8.1). As emerges from the script represented in Figure 1.1, crime starts with the recruitment. This phase is principally carried out in the source countries (Poland and Romania) and coordinated from Italy by the group leaders. The head of the group gets into contact with a broker (already known to him/her) acting in the country of origin and asks him to advertise a job in local newspapers and on the Internet. These advertisements are for young women to be employed as wait-resses, barmaids or hostesses in Italy. The job is presented as completely legal and as offering a good income (about 1,300/1,500 euros per month). Since the offer seems promising, many women respond to this advertisement and get in con-tact with the broker. The first request from the broker is to send him an updated curriculum vitae together with some photos. In this way a first selection of the possible victims to be trafficked is made: only good looking women are selected. To these girls, the broker gives some indications on the job, reassuring them about the legality of the activities and specifying that they will not be involved in pros-titution once they arrive in Italy. These explanations succeed in convincing some girls to leave. Others, reluctant to depart, are contacted by one of the leaders (the boss or his mistress) or, in some cases, another girl of the same nationality already involved in the job. They give further explanations and reassurances to potential victims. The recruitment is based on the deception of the victims, who receive fake information about their future job. According to the indications obtained and the need to have a job, the victims decide whether to leave or not to leave. In the first case, the transportation phase starts, while in the second case the process finishes here. The transportation stage consists principally of the journey from the country of origin to the country of destination. The journey may be carried out by car, bus or plane. The choice of transport depends on the event considered. In general, the traffickers organize the trip in detail, trying to have victims leave as early as possible in order to minimize the chances of them changing their minds. A car is chosen when accomplices have to go to Italy for other reasons and can offer them a lift. When the transport is by bus or plane the victims travel alone follow-ing the orders of the traffickers.8 The cost of the trip is borne by the women, who are reassured that they will quickly recoup their money once they arrived at their destination. Once the victims arrive in Italy, one of the group leaders (the boss, his mistress or his brother) meets the women at the bus stop or at the airport to take them to the boss’s house. During the transport toward the apartment, some police routine controls might take place. This does not constitute a problem for the offenders because the victims are from EU countries and therefore they have the right to stay in Italy for three months without any particular document. At this point, the third stage starts. From the first evening the women are involved in the new job. They are told to put on scanty clothes and high-heeled

_Cognition and Crime.indb 147_Cognition and Crime.indb 147 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

148 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

shoes. A man (the barman of the night club) brings the women to the night club. Here they learn that the club is an entertainment club and they are figuranti di sala (girls that have to entertain the clients). They also receive information on the job and some rules of conduct to be respected. At first these rules seem to be referred to legal activities: the women should spend time with clients having a drink with them and entertaining them without carrying out any sexual behavior. To enforce this position, the women are invited to inform the boss or his brother if anybody tries to touch them in an inappropriate manner. In return they receive a fixed pay from 50 to 70 euros per day with free accommodation and transport. On the sur-face, clients entering this club can spend an evening together with some girls and can hobnob with one of them, chatting and dancing with her in common spaces or in a privé. But despite this reassuring information, the girls’ freedom of move-ment is limited. They are prevented from leaving the club or the house unescorted and they are permitted just a few moments in the toilet.9

After a few nights’ work, respecting the rules and receiving the corresponding fixed wage, the girls understand what the real nature of the job is. In order to have a high number of clients, they have to excite them by providing sexual services, induce them to pay for many drinks and try to seduce them so that they ask the boss or his brother about the possibility of having a serata with the girls outside the club.10

The system develops through mechanisms of incentives/disincentives involv-ing the girl together with her boss and club manager: girls can move to prostitution by force or by choice because they are aware that if they do not accept the advances made by the clients in the privé and if they do not spend a serata with them, their wages are reduced. In the club the clients pay to obtain the physical company of a girl and the cost of the service offered changes according to the time spent together: if she is not able to attract the client and to satisfy his requests, he stops drinking and consequently stops giving money to the club manager. Also, if she does not play pretty, the client does not invite her for a serata, thus producing less profit for the boss. This causes a corresponding reduction in the money designated for the girl (her salary becomes directly proportional to the number of drinks her clients have). In order to receive the payment for their work, these women have to undergo this exploiting mechanism. The constriction–violence process is oriented towards those girls who do not accept the rules imposed on them by the boss: from being friendly and solicitous, the bosses become strict and exacting. In particular, they withhold the victims’ documents (officially required to draw up the employ-ment contract), add rental and transport expenses initially not charged, and so on. A delicate psychological violence is carried out with a progressive reduction of the material benefits. In this situation, some women decide to escape and return to their country of origin, while others get involved in prostitution.11 The latter victims can be sold to other exploiters, obtain some privileges12 or become the boss or his brother’s mistress, thus joining the criminal group and gaining a promotion. They pass from being prostitutes to bar girls, or collaborators in Italy or in their country of origin.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 148_Cognition and Crime.indb 148 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Rec

ruitm

ent

Gro

uple

ader

s

Bro

ker

Dec

eptiv

ead

vert

s

Pro

stitu

tes

Pho

neco

ntac

t

Pho

neco

ntac

t

Pho

neco

ntac

t

Girl

s

Yes

Yes

No

No

Exi

t

Jour

ney

Bus

Car

Pla

ne

Italy

(Cam

poba

sso)

Nig

htcl

ubA

void

traffi

cker

s ar

rest

No

sex

nigh

tclu

bK

now

n/tru

sted

clie

nts

No

paym

ent o

fth

e se

rata

at t

heni

ghtc

lub

No

sex

at h

ome

Sol

d

Priv

ilage

s

Join

gro

up

Fake

info

rmat

ion

Forc

ed in

topr

ostit

utio

n

Pro

stitu

tion

Con

trol

Wag

ere

duct

ion

Incr

ease

cost

s

Vis

are

tirem

ent

Tran

spor

tatio

nE

xplo

itatio

nA

fterm

ath

Act

ion

perfo

rmed

Pro

cess

end

ing

Mul

tiple

act

ion

Dec

isio

n

Alte

rnat

ive

Flo

w li

ne

Eve

ntua

l flo

w li

ne

Leg

end

Fig

ure

8.1

Cri

me

scri

pt c

ase

stud

y 1:

fro

m E

aste

rn E

urop

e to

Ita

ly.

Sour

ce: A

utho

rs’

elab

orat

ion

of th

e in

form

atio

n co

ntai

ned

in th

e ar

rest

war

rant

ref

erre

d to

cas

e st

udy

1.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 149_Cognition and Crime.indb 149 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

150 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

In order to ensure the trafficking goes smoothly and to avoid being identified and arrested by the law enforcement agencies, the leaders of the group adopt several strategies (the “aftermath” stage of the script). They do not allow clients to have sex with the girls inside the club in order to avoid the discovery of illegal practices during possible police controls. Similarly they do not permit the women to have sex in the house in which they live, since it is owned by the boss and might link him to illegal activities committed on the premises.13 A third strategy is to prohibit the payment of the serata inside the nightclub, because the owner of the club might be accused of pimping: in general the client meets the girl outside the club and then pays her for the service she will provide. The girl only passes the money back to the boss on the second occasion she is with the client. This last measure is to give the boss or his brother the opportunity to check out the client and to ensure that he is not a plain clothes policeman. These strategies demonstrate how traffickers take into account all the risks connected with trafficking girls and take prudential measures for minimizing them.

Case study 2: Sex trafficking from Nigeria to Italy

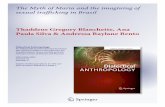

The second case considered has also been divided into four main stages (see Figure 8.2). While the first case involved indoor prostitution, the second case refers to outdoor prostitution. The different phases occur between Nigeria and Italy. In this case a pivotal role is played by the madam, a Nigerian woman who is the leader of the criminal group involved in this crime. According to her requests, the members of the criminal group acting in Nigeria recruit young and good-looking girls to be transported and exploited in Italy. They focus their attention on people with a low level of education and who are part of big and poor families. The first contact happens between these people, the girl and her family. The recruiters offer a regular job in Europe and offer to pay for their travel expenses (40,000 to 60,000 euros according to the place of origin, the economic possibilities of the family, the cost of the trip), which the girls will have to reimburse to the madam using part of the wages earned. These conditions are in general accepted by the girl and by her family who hope thereby to solve their economic problems. A contract of sorts is agreed upon by the parties. Then, the girl has to participate in a voodoo ritual in which she has to swear she will respect the contract. This ritual is celebrated by a magician who intimidates the victim by warning of future misfortunes and misery if she walks away from her responsibilities. This ritual is very important for Nigerians: they believe in the magic power of the magician, and therefore they are willing to do what the madam orders in order to avoid negative consequences to the victim and her family. In this case the soliciting of new girls is carried out by creating a debt that binds the victims to the madam until it is fully repaid. This link is cemented by the celebration of the ritual. After the oath, the transportation stage starts. The victims are forced to move into some houses owned by the criminal group for the period necessary to organize the trip and to obtain fake documents. This a delicate phase since it involves the crossing of European borders. The success of this trip depends both

_Cognition and Crime.indb 150_Cognition and Crime.indb 150 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Rec

ruitm

ent

Tran

spor

tatio

nE

xplo

itatio

nA

fterm

ath

Mad

am

Thr

eats

Deb

ts

incr

ease

Vio

lenc

e

Pro

stitu

tion

Com

plai

nt

Vio

loen

ceag

ains

tth

e fa

mily

Mat

eria

las

sist

ance

Lega

las

sist

ance

Thr

eat/

intim

idat

ion

Girl

s ar

e so

ldto

oth

ergr

oups

Pai

d by

girl

s

Girl

s

The

Net

herla

nds

Turk

ey

Italy

Gre

ece

Con

tract

/deb

t

Oat

h/w

odoo

Mag

icia

n

Gro

upm

embe

rs in

Nig

eria

Girl

sid

endi

ficat

ion

byla

w e

nfor

ecm

ent

Bro

ker

Join

t

Forg

eddo

cum

ents

Jour

ney

Cor

rupt

ion

Inte

rmed

iate

stop

s

Lago

sK

ano

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

Forc

ed in

topr

ostit

utio

n

Avo

idde

cept

ion/

colla

bora

tion

Exi

t

Fig

ure

8.2

Cri

me

scri

pt c

ase

stud

y 2:

Fro

m N

iger

ia to

Ita

ly.

Sour

ce: A

utho

rs’

elab

orat

ion

of th

e in

form

atio

n co

ntai

ned

in th

e ar

rest

war

rant

ref

erre

d to

cas

e st

udy

2.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 151_Cognition and Crime.indb 151 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

152 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

on the strategies adopted by the madams (i.e. the routes of the travel and the means of transport chosen), and on the national legislations of the transit coun-tries, which generally criminalize this activity. The arrest warrant records that some victims are transferred by air, stopping over in several European coun-tries, and others arrive in Italy by land or sea. For air travel, the most common transfer method, the victims leave from the airport of Lagos or Kano using fake documents. If there is a problem passing through immigration controls, the traf-fickers bribe the immigration officers. In general the first destination is Turkey or the Netherlands. The Netherlands is the best point of entrance in Europe thanks to its legisla-tion concerning the protection of human trafficking victims. According to the Dutch legislation, minors who declare being a victim of this crime can receive temporary residence documentation and can be accommodated in a specific reha-bilitation center where they have also the possibility of using a telephone. Once a visa is obtained, and consequently the possibility to continue the trip towards Italy, the victims get in contact with the local representative of the group (of whom they have the telephone number) who gives indications on how to escape from the center. Then, the victims meet this representative who arranges the travel towards the next destination of the trip. He is responsible for the victims from their entrance in his country to their departure.14 The trip is very long (it can last weeks) with many intermediate stops before arriving in Italy; during these stops the victims can spend one or more days under the protection of people acting as local representatives in the respective country. The choice of the stops depends on the contacts activated in the different areas and on the relationships with the madam. The second route is through Turkey: in this country a very active cell has been established and has good success in corrupting officials and facilitating the entrance of the victims. The victims are transferred from Turkey to Greece and then on to Italy. When the victims reach their destination—in this case, in Ancona, Macerata and Ascoli Piceno—the exploitation stage begins. The girls are entrusted to the madam who acquired them. She pays the travel expenses to the traffickers and takes the girls’ passports in order to give them to the traf-fickers. With no documents, work or knowledge of the Italian language, the victims are completely dependent on the madams, who give them accommoda-tion and manage all logistical issues connected to their activities (e.g. finding phone cards). The debt payment binds the victims to the madams, who consider them as property. In this case, an important precondition connected to outdoor sexual exploita-tion is the “joint”. This term refers to the place (footpath or stretch of road) where the prostitute works: those who do not have the possibility of using a joint can-not stay in that place and cannot work according to the code of conduct existing among the criminals involved in outdoor prostitution. Since prostitution is the source of the money required by the girls to compensate the madam, if there are no joints available the victims have two alternatives: they can be sold to another madam who can engage them immediately in prostitution or, to use the joint, they

_Cognition and Crime.indb 152_Cognition and Crime.indb 152 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 153

have to pay rent for it. The cost of the joint, together with the cost of board and lodging, is added to the initial debt. When the joint is available, threats and violence against the girls or their fami-lies are made to force them to prostitute themselves. The increase of the debt and the commitment taken with the voodoo ritual are also two important factors con-tributing to enforce the slavery status of the victims.15 Continuous and pervading control is exercised over the victims: the exploiters supervise the time dedicated to work as well as spare time, the freedom of movement and access to external contacts. Some victims become exploiters themselves in order to use their earnings to pay the debt more quickly: the madams give them the possibility of recruit-ing a girl (generally a sister or a friend) to be exploited in prostitution so that they can obtain the money in a shorter time. This is an important feature of the modalities used to carry out the exploitation because in this way the victims are directly involved in the criminal activities and less disposed to denounce the crime to law enforcement authorities. Since outdoor prostitution is more obvious than indoor prostitution, the arrest warrant contains many examples of victims identified by police during routine controls and held in Centers of Temporary Permanence. In order to avoid victims’ deportation or prosecution, madams offer legal and material assistance to the identified girls. They also use threats and intimidation: the fear of suffering retaliation, and the dependency and the bond with the exploiter, as a consequence of the voodoo ritual, can discourage the girls from collaborating with the authorities and force them to provide fake personal details. The girls reassure the madam of their faithfulness and their respect for the conspiracy of silence, telling her they wish to escape from the center and return to work in order to pay their debt. Only few girls report to the police their status of victims and even fewer are able to exit from the illegal exploitation.

Vulnerabilities/opportunities and possible situational crime prevention techniques

The cornerstone of situational crime prevention and the main idea introduced by script analysis is the shift of attention from “remote” causes of crime (moti-vation) to “near situational causes of crime” (motive) (Clarke 2008: 181–182). Whereas changing so-called “root causes” of crime (such as poverty, parental love, psychological problems etc.) may produce results in the long term, inter-ventions focused on immediate factors of crime, namely opportunities, can bring immediate benefits and results (Ibid.). Despite this, most of the studies on human trafficking focus on long-term factors that make victims more vulnerable to such crime (namely, poverty, underdevelopment, etc.) and propose the improvement of economic opportunities as the main solution. We are not denying that such a response may help reduce human trafficking in the long term, but the meth-odological procedure adopted in this chapter shows what it is like to wear the offender’s shoes and to thereby understand the modus operandi of the crime

_Cognition and Crime.indb 153_Cognition and Crime.indb 153 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

154 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

(Ekblom 1995: 128), identifying the immediate vulnerabilities/opportunities behind the offender’s decisions. Breaking down the complexity of the complete crime commission process through script analysis shows up the weak points in current attempts to control trafficking which are exploited by traffickers. The next step here is to make more difficult the crime commission by acting upon the benefits and costs associated with offending. This involves the application of the 25 situational crime prevention techniques. These techniques are grouped in five categories which are: increase in the efforts, increase in the risks, reduction of the rewards, reduction of provocations and removal of excuses. Five situational prevention techniques correspond to each category and, as the entire chapter, they focus on immediate responses to reduce crime. Although this classification can be useful to understand the aim of each situational measure (each category cor-responds to the aim of the measure), in practice these may often overlap and work for more purposes (Clarke and Eck 2003). As has already been discussed, even if the analysis is more focused on the crime commission from the offender point of view, the role of victims and of their decisions is crucial for the crime to be accomplished. Thus, situational crime prevention techniques may also be applied to victims, with the aim of increasing the risks and reducing rewards associated with their participation in trafficking. This approach is not designed to blame victims, but it aims at explaining that crime is, as defined by Felson (2008: 75), “a kind of social chemistry” where the simultaneous presence of offenders and victims (and of their decisions) in a given time/place and under certain circumstances is needed for the crime commission. For these reasons situational crime prevention techniques are suitable for victims as well. Some possible and useful situational crime prevention techniques aimed at reducing trafficking in human beings are presented below. These possible solu-tions, based on the two scripts discussed in this chapter, can be extended to other cases of human trafficking. The suggested strategies follow the four different script phases: recruitment, transportation, exploitation, aftermath. The situational crime prevention measures proposed in this section are not intended to be exhaus-tive but are illustrative of the sorts of strategies that might be applied in these and similar cases.

Preventing recruitment

The involvement of women in sex trafficking is associated with many risk fac-tors. Some refer to the personal conditions experienced by these people in the country of origin, while others are connected to their socio-economic and political background. As concerns their personal conditions, the literature underlines that women are more vulnerable and they can be easily manipulated because they are less able to protect themselves and to claim their rights. In addition to this, they are generally not as educated as men and this results in high rates of unemploy-ment forcing them to look for job opportunities abroad. Besides these personal conditions, the environment in which they grow up plays an important role. These

_Cognition and Crime.indb 154_Cognition and Crime.indb 154 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 155

countries are characterized by poverty, job discrimination and underdevelopment (Limanowska 2002; Okojie et al. 2003; Wijers and Lap-Chew 1999). The application of preventive measures to human trafficking at the recruit-ment stage means acting upon the supply of services provided. The measures should aim to reduce the push factors that lead young girls to leave their own country by giving a more accurate picture of risks and benefits: limited free-dom, being abused, mistreated, beaten and threatened. Raising consciousness through campaigns about the risks and dangers of such overseas trips is the first step toward reducing the number of recruited girls. This could be achieved by several means: through newspapers, TV advertisements, local leaders and so on. Potential victims may also be targeted by creating anti-trafficking watch-dog committees (UNESCO 2006: 59). In particular, watchdog committees would focus on rural areas in the African countries (less exposed to media sensitization) and to young girls from Eastern countries working in the entertainment indus-try (who are more vulnerable). Finally, the recruitment of girls may be reduced by monitoring advertisements on local/national newspapers, websites etc. These advertisements give little or no information about the job, the workplace and the entrepreneurs. Since case study 1 showed advertisements to be one of the main lures to “capture” victims, reducing advertisement anonymity (requiring further information) may increase risks for whoever (traffickers or brokers) publish them. For example, the policies on the information needed to publish journals or dedicated public advertisements should be revised and should oblige whoever publishes them to require more details on workplace, place (address) and manag-ers’ personal details.

Preventing transportation

The application of situational crime prevention to the transportation stage is dif-ficult within the EU countries owing to the principle of freedom of movement within them. The main problems to face in the transportation stage are two con-nected criminal phenomena, namely corruption and forged documents. The role of corruption in trafficking of human beings has been previously highlighted as a crucial factor (Zhang and Pineda 2008). Corruption not only occurs within the source countries, but it takes place in destination and transit countries as well. Illegal trafficking of people across countries requires negotiating a number of checks: visa/documents/resident permit checks and embassy/border patrol checks. Traffickers need to avoid or overcome these checks so as not to interrupt the traf-ficking process. Criminal organizations use corruption to obtain forged documents and to facilitate border crossings. As Van de Bunt and Van der Schoot (2003) pointed out in their recommended situational crime measures against organized crime, forged documents are important tools exploited by criminals, and conse-quently decreasing their availability can help reduce human trafficking/smuggling. Countermeasures identified by Van de Bunt and Van der Schoot (2003: 23), aiming at limiting the availability of such tools, include improving controls where docu-ments are stored and an improving technical instruments to reduce their forgery

_Cognition and Crime.indb 155_Cognition and Crime.indb 155 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

156 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

(such as biometric technologies). Moreover, airline companies and officials across all European countries should increase their commitment to controlling passen-gers’ identity documents, acknowledging (thus removing excuses and assisting compliance) that their negligence could favor criminal activities. Case study 2 demonstrated a clear case of offender adaptation (defined as cir-cumventing the preventive measures implemented with the aim to tackle criminal activities), namely the response of traffickers to the B9-regulation of the Dutch Code (Chapter 9 of the Aliens Act Implementation Guidelines). The B9-regulation allowed to whoever declared having been a victim or witness of trafficking to reside legally in the Netherlands upon condition that they collaborated with the authorities. During their stay victims can take advantage of a place to stay, wel-fare benefits and medical assistance. Traffickers exploit this regulation to let victims enter the Netherlands and, once in, they help them to escape from refugee centers. Respecting everyone’s human rights, B9 application should require some further evidence of being victims of trafficking and, moreover, victims should be informed of the risks (being beaten, exploited, threatened, etc.) they run if they want to escape from the refugee centers. This duty should be covered with the help of NGOs in the Netherlands.

Preventing exploitation

The application of preventive measures to the exploitation stage of human traf-ficking mainly involves acting on the demand side for such service, and this requires attempts to reduce requests for illegal sex workers. There are various available interventions. The most extreme, the legalization of prostitution as a profession, was applied for the first time in the Netherlands in 2000. Other practical actions may be designed to disrupt the market. One strategy is to con-centrate on those points where the legal and illegal world come into contact since these are the places that facilitate the exploitation of prostitution. They include restaurants, hotels, motels, discos, nightclubs, taxis, beauty centers and so on. Suspending licenses or imposing high costs on those operators who facilitate the exploitation of illegal immigrants would deter entrepreneurs from investing in such activities. Finckenauer and Chin (2010: 75) also suggested targeting unan-nounced raids on the above-mentioned businesses as a way to break down the illegal sex worker market. Information campaigns have already been mentioned as measures to reduce the supply of illegal workers, thus increasing risks (or represented risks) for potential victims of exploitation by traffickers. But the purpose of information/sensitization campaigns may go further and help to crack down on the market for alien workers. In fact, demand (the clients) and supply (the illegal sex workers) meet in a “grey area” halfway between the hidden (to law enforcement) and the known (by clients). Information campaigns should focus on those people (for instance postal workers, doorkeepers, etc.) who may have access to such a “grey area” and would be willing to report to law enforcement possible cases of sexual workers’ exploitation.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 156_Cognition and Crime.indb 156 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 157

Another counteraction to decrease demand for victims of human trafficking is to act directly on buyers of such services by deterring clients (by increasing costs) of illegal sex workers. Measures aimed at acting on this side of the sexual market are controversial and no agreement has been reached yet in Western countries. In Italy prostitute clients are not criminalized, but other Western countries apply criminal sanctions for soliciting prostitutes. In France and Sweden clients of pros-titutes are criminally liable, whereas some cities in the US apply car confiscation programs for soliciting prostitutes (Finkenauer and Chin 2010). Car confiscation programs, driving license withdrawal and other administrative measures offer ways to act upon costumers without criminalizing them. One of the vulnerabilities exploited by criminal organizations that was iden-tified in the two case studies is the misuse of non-banking financial institutes. These have been defined by Van de Bunt and Van der Schoot (2003: 13) as the “weak spot” in the fight against money laundering. Case study 2 showed that money is sent via Western Union Money Transfer. Van de Bunt and Van der Schoot argue that such entities, even if they are not banks, should be ruled by anti-money laundering legislation to make the payments traceable and to close off the vulnerability gap exploited by criminal organizations.

Preventing aftermath

The last pinch-point identified where it is possible to apply situational prevention measures is the collaboration between law enforcement and victims of traffick-ing. Usually this collaboration is quite poor owing to the victims’ lack of trust in the law enforcement and their fear of being deported from the country (since they are illegal immigrants). The victims’ collaboration with the law enforcement agency can be disruptive for the criminal organization for two main reasons: (1) the loss of the sexual services offered by the victims for whom traffickers have paid travel expenses to the destination country represents an increase in the costs (this is shown in case study 2, where traffickers paid legal assistance for those victims identified by law enforcement); (2) as any form of collaboration with police forces, this can reveal information for targeted law enforcement measures. Policies to reinforce collaboration should be enforced. In particular, residence permits for those immigrants who are exploited by criminal organizations should be made available in all the European countries as provided for in existing Italian legislation (i.e. Legislative Decree 286/1998 called “Immigration Law”—in particular Article 18 of this Decree “Residence for social protection motives”). Usually victims are not aware of the existence of such measures and their mistrust of the police means that these measures are rarely applied. NGOs are the first line in victims’ collaboration and can inform victims of their rights and facilitate their collaboration, protection and assistance. All the situational crime prevention techniques identified in order to reduce sex trafficking are shown in Table 8.1.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 157_Cognition and Crime.indb 157 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

158 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

Table 8.1 Proposed situational crime prevention techniques

Situational crime prevention measure

Related situational prevention technique

Aim Crime script stage

Awareness campaigns and anti-trafficking watchdog committees

Alert conscience Increase risks and remove excuses

Recruitment

Reducing announcement anonymity

Reduce anonymity Increase risks Recruitment

Improving controls over documents store

Control access to facilities

Increase efforts Transportation

Improving technical instruments against documents forgery

Target harden Increase efforts Transportation

Improve commitment to control passengers documents

Assist compliance Reduce excuses Transportation

Unannounced raids and suspended licenses

Disrupt market Reduce rewards Exploitation

Information campaigns Alert conscience Reduce excuses Exploitation

Car confiscation and driving license withdrawal

Deny benefits Reduce rewards Exploitation

Traceable payments Reduce anonymity Increase risks Exploitation

Favor victims collaboration Assist compliance Remove excuses Aftermath

Conclusions

The analysis proposed in this chapter represents a new approach to human traf-ficking. The shortage of data on human trafficking led the authors to shift from a macro analysis to an in-depth study applying script analysis. This chapter follows and develops this line of research, aiming to present the crime commission pro-cess in terms of environmental opportunities/vulnerabilities. The breaking down of the complex components of the crime through script analysis helped to identify those vulnerabilities/opportunities exploited by criminals and to suggest possible crime prevention measures to address such vulnerabilities. This chapter provides examples of how script analysis could be applied to crimes related to the phenomenon of human trafficking. The scripts represent the two main exploitation typologies of alien sexual workers: indoor and outdoor prostitution. In highlighting the main situational prevention interventions to address the different phases of human trafficking we are not suggesting that we have neces-sarily added any new strategies to those already known from past experience. Governments, law enforcement agencies and NGOs have known about and prac-ticed some of these interventions for a long time, on and off. The added value of

_Cognition and Crime.indb 158_Cognition and Crime.indb 158 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 159

this analysis is to incorporate these interventions into a broader and more coherent strategy for addressing the phenomenon. Script analysis provides a framework for monitoring the impact of each intervention and consequently for understanding and modifying interventions if they do not work. We argue that script analysis can improve the effectiveness of the entire situational prevention effort. More generally, this chapter has been an opportunity to develop, building on previous research (Savona 2009), the crime script approach to organized crime. Crime scripts and organized crime do not go easily together. Organized crime, owing to its international nature, complexity and connections with legal economy, cannot be simplified into steps without naming properly these steps in relation to the content of the crime considered and without pointing out how these steps are in relation to other variables. The adoption of flow chart terminology and computer-based semiotics represent the next step (and the next challenge) for a more precise approach to scripting that permit the analysis of crimes with a high level of complexity. If this ambition represents the main meal for the future of crime scripts applied to complex crimes, this chapter has been an appetizer.

Notes

1 To each phase different collateral crimes can be associated, many of them strictly connected to the commission of the crime. These crimes can be carried out against victims (e.g. kidnapping, simple and aggravated assault, rape, extortion, threat and so on) or against the State (e.g. document forgery, corruption of governmental officials, abuse of immigration law, tax evasion, money laundering) (Aronowitz 2009; Comitato parlamentare per la sicurezza della Repubblica 2009).

2 According to Paragraph b of Article 3, the consent of the victims should be considered irrelevant because it is obtained using deception, violence or other means and for this reason it is not a valid consent. In many cases, consent is given without knowing the real conditions of exploitation that will be suffered in the destination country (Goodey 2004).

3 These networks can be informal or organized. The informal networks are associated with small-scale trafficking and the members are connected by ethnic and/or familiar bonds (Bosco et al. 2009; Väyrynen 2003) while the organized networks operate on a large scale with criminals specialized in each phase of the trafficking. They are very flexible, horizontal and able to change their action according to legislative variations and to the affirmation of new profitable opportunities (Schloenhardt 1999).

4 There are three main international organizations that produce global data on human trafficking: the International Labour Organization, the International Organization for Migration and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Bosco et al. 2009).

5 The law enforcement agencies collect data on the victims identified and registered by the police, the border guards and other control structures while the social services and the NGOs are focused only on the victims involved in specific assistance and protec-tion programs (Savona and Stefanizzi 2007; Vermeulen et al. 2010; IOM 2005).

6 Only one study based on this technique has been carried out, by Cockbain et al. in 2011, in order to analyze UK internal child sex trafficking.

7 It concerns trafficking in human beings for sexual exploitation carried out in night-clubs involving victims from Eastern Europe (especially Polish and Romanian). This case was indicted by the Court of Campobasso (Molise region) in 2010.

8 The traffickers give the victims precise instructions concerning the departure and the arrival time, the bus stops or the airport chosen. This is done in order both to control

_Cognition and Crime.indb 159_Cognition and Crime.indb 159 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

160 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

the victims and to assure their arrival, considering that they do not know the language and have no experience in travelling.

9 Victims can go out only if accompanied by the boss or the boss’s brother and at certain times of the day in order to avoid having contact with other people.

10 The term serata is used to indicate the services given to some clients, involving spend-ing time with the girls in the club and having sex with them outside the night club (this service costs about 200/250 euros). The possibility of serata depends on the drinks paid for by the client: only those buying a large number of drinks and consequently ensuring high earnings to the club can have sexual intercourse with the girl.

11 Many women are not psychologically and materially able to escape because they live in a very vulnerable condition: they have no money and they need to work, they do not speak Italian and do not know the place where they live; they depend on the traffickers for all their primary requirements, and they have no documents.

12 The wishes of those girls who ensure a high profit are often met. For example, they can stay at home some evenings and can wear trousers.

13 If the girls receive the clients at home they might attract the attention of the neighbors, who could advise the police.

14 Each lap of the trip is coordinated and managed by the local representative who is directly connected to the madam.

15 The increase of the debt is arbitrarily chosen by the madams and is given as sanction to complaints or violation of agreements.

References

Adepoju, A. (2005) “Review of research and data on human trafficking in sub-Saharan Africa,” in International Organization for Migration (ed.) Data and research on human trafficking: A global survey (pp. 75–98), Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Aronowitz, A. (2001) “Smuggling and trafficking in human beings: The phenomenon, the markets that drive it and the organizations that promote it,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 9: 163–195.

Aronowitz, A. (2009) Human trafficking, human misery: The global trade in human beings, Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Beauregard, E., Proulx, J., Rossmo, K., Leclerc, B., and Allaire, J. F. (2007) “Script analysis of the hunting process of serial sex offenders,” Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34: 1069–1084.

Beeks, K. and Amir, D. (eds.) (2006) Trafficking and the global sex industry, Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Bosco, F., Di Cortemiglia, V.L., and Serojitdinov, A. (2009) “Human trafficking patterns,” in C. Friesendorf (ed.) Strategies against human trafficking: The rule of the security sector (pp. 35–82), Vienna: National Defence Academy and Austrian Ministry of Defence and Sports.

Brayley, H., Cockbain, E., and Laycock, G. (2011) “The value of crime scripting: Deconstructing internal child sex trafficking,” Policing, 5(2): 132–143.

Chiu, Y. N., Leclerc, B. and Townsley, M. (2011) “Crime script analysis of drug manufacturing in clandestine laboratories: Implications for strategic intervention,” British Journal of Criminology, 51: 355–374.

Clarke, R. V. (2008) “Situational crime prevention,” in R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis (pp. 178–194), Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 160_Cognition and Crime.indb 160 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 161

Clarke, R. V. and Eck, J. (2003) Become a problem solving crime analyst in 55 small steps, London: Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science.

Cockbain, E., Brayley, H., and Laycock, G. (2011) “The value of the crime scripting: Deconstructing internal child sex trafficking,” Policing, 5(2): 132–143.

Comitato parlamentare per la sicurezza della Repubblica (2009) Relazione. La tratta degli esseri umani e le sue implicazioni per la sicurezza della Repubblica, Doc. XXXIV, n. 2, XVI Legislatura.

Cornish, D. (1994) “The procedural analysis of offending and its relevance for situational prevention,” in R. Clarke (ed.), Crime Prevention Studies,Vol. 3 (pp. 151–196), New York: Criminal Justice Press.

Cornish, D. and Clarke R. V. (eds.) (1986) The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Cornish, D. and Clarke R. V. (2008) “The rational choice perspective,” in R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental criminology and crime analysis (pp. 21–47), Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

David, F. and Monzini, P. (2000) Human smuggling and trafficking: A desk review on the trafficking in women from the Philippines. Paper presented at the Tenth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, Vienna, 10–17 April 2000; Doc A/Conf.187/CRP.1 15 April 2000.

Ekblom, P. (1995) “Less crime, by design,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sceince, 539: 114–129.

Europol—European Law Enforcement Agency (2002) Crime assessment: Trafficking in human beings into the European Union, Aja: Europol.

Felson M. (2008) “Routine activity approach,” in R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental criminology and crime analysis, Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

Finckenauer, J. O. and Chin, K. (2010) “Sex trafficking: A target for situational crime prevention?” in K. Bullock, R. V. Clarke, and N. Tilley (eds.) Situational prevention of organized crime (pp. 58–80), Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

Friesendorf, C. (2007) “Pathologies of security governance: Efforts against human trafficking in Europe,” Security Dialogue, 38(3): 379–402.

Goodey, J. (2004) “Sex trafficking in women from Central and East European countries: Promoting a ‘victim-centered’ and a ‘woman-centered’ approach to criminal justice intervention,” Feminist Review, 76: 26–45.

Hancock, G. and Laycock, G. (2010) “Organized crime and crime scripts: Prospects for disruption,” in K. Bullock, R. V. Clarke, and N. Tilley (eds.), Situational prevention of organized crime (pp. 172–192), Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

IOM—International Organisation for Migration (2005) Data and research on human trafficking: A global survey, Geneva: International Organisation for Migration.

IOM—International Organisation for Migration (2009) Guidelines for the collection of data on trafficking in human beings, including comparable indicators, Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

Iselin, B. (2003) Trafficking in human beings: New patterns of an old phenomenon. Paper presented at Trafficking in Persons: Theory and practice in regional and international cooperation, Bogota, Colombia, November 19–21.

Kleemans, E. R. (2011) “Expanding the domain of human trafficking research: Introduction to the special issue of human trafficking,” Trends in Organized Crime, 14: 95–99.

Lacoste, J. and Tremblay, P. (2003) “Crime and innovation: A script analysis of patterns in check forgery,” in M. Smith and D. B. Cornish (eds.) Crime prevention studies:

_Cognition and Crime.indb 161_Cognition and Crime.indb 161 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

162 E. Savona, L. Giommoni, M. Mancuso

Theory for practise in situational crime prevention, Vol. 16, pp. 169–196). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

Laczko, F. and Gramegna, M.A. (2003) “Developing better indicators of human trafficking,” Brown Journal of World Affairs, X(1): 179–194.

Lebov, K. (2010) “Human trafficking in Scotland,” European Journal of Criminology, 7(1): 77–93.

Leclerc, B., Wortley, R., and Smallbone, S. (2011) “Getting into the script of adult child sexual offenders and mapping out situational measures,” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48: 209–237.

Limanowska, B. (2002) Trafficking in Human Beings in South Eastern Europe, Geneva: UNICEF, UNOHCHR and OSCE.

Liu, M. (2011) Migration, prostitution and human trafficking: The voice of Chinese women, New Brunswick, NJ and London: Transaction Publishers.

Ministero dell’Interno (2007) Rapporto sulla criminalità in Italia, Analisi, prevenzione, contrasto, Roma, 18 giugno.

Morselli, C. and Roy, J. (2008) “Brokerage qualifications in ringing operations,” Criminology, 46(1): 71–98.

Motta, C. (2008) Contrasto alla tratta di persone: normative, investigazioni, esigenza di azioni integrate. Relazione del dott. Cataldo Motta, Procuratore distrettuale antimafia di Lecce, al two day meeting di Zagreb 16 e 17 maggio 2008 nell’ambito del progetto E.n.a.t. —European network against trafficking.

Motta, C. (2010) La tratta delle donne e lo sfruttamento della prostituzione, in Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura—Ufficio per gli incontri di studio, Incontro di studio sul tema: Violenza di genere, mobbing e stalking , Roma 17–19 maggio 2010 Ergife Palace Hotel.

Okojie, C.E.E., Okojie, O., Eghafona, K., Vincent-Osaghae, G., and Kalu, V. (2003) Trafficking of Nigerian girls to Italy. Report of field survey in Edo State, Nigeria, Turin: United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute.

Picarelli, J. (2009) “Human trafficking and organized crime in the US & Western Europe,” in C. Friesendorf (ed.) Strategies against Human Trafficking: The rule of the security sector (pp. 115–136), Vienna: National Defence Academy and Austrian Ministry of Defence and Sports.

Salt, J. (2000) Trafficking and human smuggling: A European perspective, Oxford: Blackwell.

Savona, E. U. (2010) “Infiltration of the public construction industry by the Italian organized crime,” in K. Bullok, R. V. Clarke, and N. Tilley (eds.) Situational Prevention of Organized Crimes (pp. 130–150). Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing.

Savona, E. U. and Stefanizzi, S. (eds.) (2007) Measuring human trafficking: Complexities and pitfalls, Dordrecht: Springer.

Schank, R. C. and Abelson R. P. (1977) Script, plans, goals and understanding: An inquiry into human knowledge, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schloenhardt, A. (1999) “Organized crime and the business of migrant trafficking,” Crime, Law and Social Change, 32: 203–233.

Shelley, L. (2010) Human trafficking: A global perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Tompson, L. and Chainey, S. (2011) “Profiling illegal waste activity: Using crime scripts as a data collection and analytical strategy,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 17: 179–201.

Transcrime (2003) Trafficking and smuggling of migrants into Italy. Analyzing the phenomenon and suggesting remedies, report realized in collaboration with Direzione

_Cognition and Crime.indb 162_Cognition and Crime.indb 162 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52

Human trafficking for sexual exploitation 163

Nazionale Antimafia for Italian Ministry of Justice and Italian Ministry for Equal Opportunities.

Transcrime (2010) Servizio di expertises e competenze per il monitoraggio, raccolta dati, ricerche sperimentali, elaborazione ed implementazione di un sistema informatico per supportare l’attivazione dell’Osservazione sul fenomeno della tratta degli esseri umani, DPO Project, Dipartimento per le Pari Opportunità.

Tremblay, P., Talon, B., and Hurley, D. (2001) “Body switching and related adaptations in the resale of stolen vehicles,” British Journal of Criminology, 41: 561–569.

UNESCO (2006) Human trafficking in Nigeria: Root causes and recommendations, Policy Paper Poverty Series N. 14.2 (E).

UNICRI—United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research (2005) Programme of action against trafficking in minors and young Women from Nigeria into Italy for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

UNODC—United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2009) Global report on trafficking in persons.

UNODC—United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2010) The globalization of crime: A transnational organized crime threat assessment.

US Department of State (2005) Trafficking in persons report.US Department of State (2008) Trafficking in persons report.Van de Bunt, H. and Van der Schoot, C. (2003) Prevention of organized crime: A

situational approach, Research and Documentation Centre of the Ministry of Justice in the Netherlands (WODC).

Van Duyne, P. and Spencer, J. (2011) Flesh and money. Trafficking in human beings, Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers.

Van Liemt, G. (2004) Human trafficking in Europe: An economic perspective, Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Väyrynen, R. (2003) Illegal migration, human trafficking, and organized crime, Discussion Paper N. 2003/72, United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research.

Vermeulen, G., Van Damme, Y., and De Bondt, W. (2010) “Perceived involvement of ‘organised crime’ in human trafficking and smuggling,” International Review of Penal Code, 81: 247–273.

Wijers, M. and Lap-Chew, L. (1999) Trafficking in women, forced labour and slavery-like practices in marriage, domestic labour and prostitution, Utrecht: STV.

Willison, R. and Siponen, M. (2009) “Overcoming the insider: Reducing the employee computer crime through Situational Crime Prevention,” Communication of the ACM, 52(9): 133–137.

Zhang, S. X. and Pineda, S. L. (2008) “Corruption as a casual factor in human trafficking,” in D. Siegel and H. Nelen (eds.), Organized crime: Culture, markets and policies (PP. 41–55), New York, NY: Springer.

Zhang, S., Chin, K., and Miller, J. (2007) “Women’s participation in Chinese transnational human smuggling: A gendered market perspective,” Criminology, 45: 699–733.

Zimmerman, C. (2003) The health risks and consequences of trafficking in women and adolescents, London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

_Cognition and Crime.indb 163_Cognition and Crime.indb 163 26/04/2013 16:5226/04/2013 16:52