Calculation scripts for ensemble hydrograph separation - HESS

Grammatology and digital technologies. Different applications of the concept of ‘character’ in...

Transcript of Grammatology and digital technologies. Different applications of the concept of ‘character’ in...

QUADERNI DELLA RICERCA SCIENTIFICA

Serie Beni culturali 20

Comitato di redazione

Gennaro Carillo, Giovanni Coppola, Piero Craveri, Edoardo D’Angelo, Pierluigi Leone de Castris,

Emma Giammattei, Massimiliano Marazzi

I volumi della collana sono distribuiti da HERDER 00186 Roma piazza Montecitorio, 120 tel. +39 06.6794628 / 6795304 fax +39 06.6784751 www.herder.it [email protected] ISBN 978-88-960-55-342

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDÎ SUOR ORSOLA BENINCASA

CENTRO MEDITERRANEO PRECLASSICO

studi e ricerche

III

studi vari di egeistica, anatolistica e del mondo mediterraneo

a cura di Natalia Bolatti-Guzzo,

Silvia Festuccia, Massimiliano Marazzi

indice 9 premessa 11 günter neumann

System und Ausbau der hethitischen Hieroglyphenschrift traduzione e note critiche a cura di natalia bolatti-guzzo e massimiliano marazzi

MONDO ANATOLICO E VICINO ORIENTE

53 paola dardano

il vento, i piedi e i calzari: i messaggeri degli dei nei miti ittiti e nei poemi omerici

89 silvia festuccia

the bronze age moulds from the levant: typology and materials

111 rita francia

la struttura ‘poetica’ degli exempla ittiti nel “canto della liberazione”

145 federico giusfredi

note di lessico e di cultura “scribale” ittita e luvia 173 clelia mora – matteo vigo

attività femminili a Ḫattuša: la testimonianza dei testi di inventario e degli archivi di cretulae

225 alfredo rizza grammatology and digital technologies. different applications of the concept of ‘character’ in unicode and other non-technical problems about ancient scripts

MONDO EGEO

255 carmine afeltra

la pittura minoica d’epoca neopalaziale: aspetti iconografici, contestualizzazione architettonica e interconnessioni nel Mediterraneo orientale

291 serena di tonto

settlement patterns in the Mesara plain during the neolithic period

317 arianna rizio

evidence of destruction from the Peloponnese during the late helladic period

MEDITERRANEO: TUTELA E CONSERVAZIONE DEI BENI CULTURALI

337 stefano bartone

il problema del golfo della Sirte e del patrimonio archeologico sommerso, i crimini contro i beni culturali e l’azione UNESCO

345 valeria li vigni l’opera dei pupi siciliani: patrimonio immateriale orale dell’umanità

367 claudio mocchegiani carpano archeologia in acqua: dalla conoscenza alla tutela

383 sebastiano tusa aspetti etico-giuridici nella ricerca archeologica subacquea

alfredo rizza

grammatology and digital technologies different applications of the concept of

‘character’ in Unicode and other non-technical problems about ancient scripts∗

Ἔστι µὲν οὖν τὰ ἐν τῇ φωνῇ τῶν ἐν τῇ ψυχῇ παθηµάτων σύµβολα, καὶ τὰ

γραφόµενα τῶν ἐν τῇ φονῇ. καὶ ὥσπερ οὐδὲ γράµµατα πᾶσι τὰ αὐτὰ, οὐδὲ

φωναὶ αἱ αὐταί

(Arist. de int. 16a)

..., eine Tasse mehr! (G. Neumann, de civ. gramm., o.p.)

1. The concept of ‘character’ in the encoding of ancient scripts

1.1 Definition of character in Unicode1

The definition of ‘character’ in the online ‘Glossary of Unicode Terms’2 reads:

«Character. (1) The smallest component of written language that has semantic value; refers to the abstract meaning and/or shape, rather than a specific shape (see also glyph), though in code tables some form of visual representation is essential for the reader’s understanding. (2) Synonym for abstract character. (3) The basic unit of encoding for the Unicode character encoding. (4) The English name for the ideographic written elements of Chinese origin.»

(3) is, so to say, a rather ‘tricky’ definition (whatever is a character in Unicode, is a character in Unicode), but it is nonetheless necessary as otherwise the definition would cause inconsistencies in the application of the concept. In particular we are interested here in (1), where the character is defined with

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

226

respect to a ‘written language’,3 and we come directly to the point: are Hittite Cuneiform and, e.g., Sumerian Cuneiform two different written languages, or just one? If two, we should have two independent code charts each; if not, one is enough.

1.2. The application of the concept in the encoding of

ancient scripts

Obviously, Hittite Cuneiform is an independent written language that applies a notational logosyllabographic cuneiform system adapting it in shapes and orthographical rules to its own aims. Sumerian as well makes use of a notational logosyllabographic cuneiform system that in the Sumerian tradition4 is embodied through rules and shapes that differentiate greatly from the ones of Hittite. So Latin and Greek are two written languages that adapted a notational alphabetic system developing single traditions in shapes and orthographic rules. We can say more: Latin and Ancient Greek are today represented as written language by a tradition that produced normalized notational systems for all the geo-chronological variants of the two languages. This tradition does not exist for the cuneiform written languages.

What is evident in the encoding of cuneiform, on the one hand, and other ancient scripts, on the other side, is that cuneiform is treated as a notational system firmly independent of the various cultures that made use of it. The alphabets, instead, are more often treated historically.

2. The different application of the concept ‘character’

2.1. Alphabets

2.1.1. Old Semitic The historic alphabets are normally considered as

independent written languages, and this is grounded on their historical developments, geo-chronological variants, scholarly traditions and political-cultural reasons. That is to say, the

grammatology and digital technologies

227

definition of character for alphabets is, as a norm, compliant with point (1) in the definition reported above (§1). For the encoding of the characters of an ancient alphabetic script, one needs to go through a watchful paleographic analysis and a careful evaluation of the distinctive functions of the signs in the documents, but to define the boundaries that make a certain script worthy of being independently listed in Unicode, we normally resort to our scholarly tradition in assigning to the different historical cultures their own recognizable historical products.

Many alphabetical scripts share a common origin for the notational unit ‘a’, but for each ancient script each unit is a different character and so perfectly understandable within a system that specifically wants to avoid any code point-sharing (cf. T1). Unicode solved the problem still present in preceding standards such as ISO-8859-x, where a number of present-day and ancient scripts had to share a 256 code points table.5 Still, some of the fonts used in this article encode a certain script into two different ranges. Let us take for example the fonts provided by Yoram Gnat for Ancient Semitic Scripts used in T1.6

«The basic Canaanite alphabet consisted of 22 signs representing consonants (in some languages like Ugarit up to 27 signs). The names of the signs are/were very similar to the still used names of Hebrew letters.

All the fonts contain the glyphs in the Hebrew Unicode code range (0590-05FF). Starting with Unicode standard 5.2, the Phoenician, Imperial Aramaic and Samaritan languages have their own designated code ranges. Therefore, the relevant fonts have the glyphs encoded in their respective Unicode designated ranges as well.

Fonts 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and 9 contain the glyphs in the Phoenician Unicode range (10900-1091F).»7

Some of the glyphs designed to represent Aramaic or other Semitic scripts were simply assigned the code point of the Hebrew characters. When the single script was given the Unicode codification, they were also mapped to the respective

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

228

ranges. The author of the font explicitly speaks of a Canaanite alphabet that is treated as a notational system within a number of written languages that can thus share the same code-points. This is also what occurred with Cuneiform. But if we want to be able to recognize and unequivocally encode not only notational systems in abstract, but also historical written languages, then we have to introduce specific ranges for all the alphabets of Ancient Palestine, which are, indeed, very similar.

(T1): encoding of common origin8 notational unit ‘a’

original script derived scripts / written languages examples of glyphs code-points

Imperial Aramaic letter aleph � � � 10840

Phoenician letter alf 10900 א

Samaritan letter alaf 0800 ࠀ

Hebrew letter alef

א א אא

א א א א

אא א

05D0

Inscriptional Pahlavi

letter aleph 10B60

Inscriptional

Parthian letter aleph 10B40

Avestan letter A 10B00

Lydian letter A � 10920

Lycian letter A � 10280

‘Original’ aleph

א

Carian letter A � 102A0

grammatology and digital technologies

229

2.1.2 Old Italic Let us now briefly comment the encoding of Old Italic.

The code range for Old Italic was previously denominated Etruscan. The label ‘Old Italic’ includes languages of different genetic origin that, in part or in all their surviving corpus, made use of an alphabet mediated by the Etruscans. The picture of the spread of alphabetical notations in Old Italy may be much more complex. The interesting points here, which are not easy to understand in the present Unicode encoding, are (1) why the Old Semitic alphabets each receive a code range while the Old Italic ones share the same; (2) why only the alphabets of Etruscan origin and not also the Italiote Greek one (used, e.g., for Oscan) were included. The Old Italic writing systems, as a matter of fact, have at least three different origins: Etruscan, southern Italian Greek and Roman.9 Only a specific scholarly tradition can justify, in my opinion, the selection made. Little 2011 explains to the UTC10 why the scripts of Old Northern Italy can be unified with the Old Italic block. I cite here the treatment of the shapes of the unit ‘a’:

«Within northern Italic, Α (Ven, Rh, Lep, Lig), Ϝ (Rh, Lep, Gal, Lig), and Α (Ven, Rh, Lep) are the most common forms [...]. The widespread northern Italic use of Α and Ϝ (itself not elsewhere attested, though clearly related to the former) suggests the possibility that northern Italic constitutes a script distinct from Old Italic, but all forms retain the same general phonetic value and are clearly derived from a common model.»11

It is very interesting to note that the reduction to one single character is grounded on: (a) identical glottic function («same general phonetic value») and (b) common notational origin (i.e. from within a set of shapes that can be subsumed to a single class). Is this not also the case for Old Semitic scripts? To me, it is evident that the application of the concept of ‘character’ is dynamic and, at least, is conditioned by notational evidence, glottic function, and, very importantly, socio-cultural

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

230

premises. Nothing bad in all this. Only worth keeping it in mind.

2.2 Cuneiform

Cuneiform is subsumed under a unique generic ‘script’ (or written language?) detached from its historical developments, geo-chronological variants and socio-cultural peculiarities.12

This picture correspond to the ‘script-based’ solution proposed as a possible encoding method in Bunz 2000. Bunz attempts to classify different ancient scripts in view of their encoding into Unicode. In Bunz 2000 the ancient scripts are grouped together according to specific criteria. There are ancient scripts that are highly significant in present day social and religious communities (Bunz 2000 category A). To be part of this category a script should also have been «properly analyzed so that a paleographic database can be established which allows for a quasi-standardization of functional script units».13

(T2): encoding(s) of common origin notational unit ‘LI’

original script derived scripts/written languages

examples of glyphs code point(s)

Palaeo Babylonian �, �

Neo Assyrian �

Hittite �, �

Hurrian (Mittanni)

Elamite

121F7

The typical case is exemplified with Avestan:

«Avestan is a yet unencoded script of this category. This is a

grammatology and digital technologies

231

phonetic alphabet created by the Zoroastrians, presumably about 400 B.C., on the basis of the so-called Pahlavi book script, in order to render precisely the pronunciation of the sacred texts as realized in ritual performance. Like this, Avestan is the first known instance of a narrow phonetic transcription. In encoding, unification with Pahlavi is not recommended, since the majority of the characters are specific modifications or new shapes added to the original set.»14

A number of very interesting assertions in the quotation deserve a proper comment. Let us here only briefly remark that Avestan is considered an independent script because (a) it is created with a specific aim, (b) it changes the shapes of the original set. Nothing about the language is mentioned. We will come back to these points later on.

Bunz 2000 category B comprises scripts that are «in the first place an object of scientific research» and are subdivided into two sets: B1, i.e. scripts encodable from the scientific point of view;15 B2, i.e. scripts not yet encodable from the scientific point of view.16 Then comes cuneiform. Bunz 2000 category C1 defines historic «scripts which are dealt with almost exclusively in the academic world [...] All scripts of this category are unencodable by definition, i.e. any attempt to derive abstract characters will necessarily fail, since the repertoires do not support it.» Or, maybe better explained:

«According to the Unicode design principles, one would establish a unified encoding for cuneiform. But the attempt to draw up an abstract encoding even for one single language dependent writing system is useless, because in the course of its long history no standardization has ever been made. What has come down to us from the extensive text production of the Ancient Near East, are exclusively manuscripts in the very sense of hand-writings, showing up features of date, writing school, office, but also the particular features of the scribe’s personal manner of handling the pencil. Deriving standard shapes from more than a sixscore of ductus of different scriptoria as well as of individual and often abbreviated graphic shapes, would mean to introduce something intrinsically alien to cuneiform writing [...]. There is a sharp contrast to the situation with Old Persian

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

232

cuneiform [...].»17

This quotation also demands a long commentary, in many aspects. Let us touch on some of them. Old Persian has «a high degree of regularity and balance in the script [...], the opportunity never occurred for a cursive writing to be derived from the geometrically balanced wedge lengths and positions [...].»18 The question here is the following: what does the process of deriving standard shapes have to do with the collection of a character repertoire if the character is an abstraction from the specific shape variants? Together with the application of the concept of character, another problem is here at work, i.e. the sense of the creation of specific fonts that would never be able to give the minimal information required for scholarly use. The problem concerns more the glyph here, not the character in itself. A good transcription, from a linguistic aspect, is far more illustrative than the original document itself. But it is the original alone that can offer information about its being part of a certain scribal tradition with ductus peculiarities and so on. The point can be made even more clearly: creating fonts, Unicode or not, regardless, for the study of the cuneiform texts, be this philological, epigraphical or linguistic, is not only useless, but also misleading. In my opinion the same is true for educational aims. Cuneiform would be better understood by making clay tablets and printing the signs on them. Reducing the cuneiform script from a 3-D Schrifträger to a 2-D one, like paper or a normal word processor page, is something that has been already done in antiquity.19

Another point of interest in the quotation is that according to Unicode principles, cuneiform should be encoded as a unified system. We saw that the principles involved in the decision of what is an independent “Unicode script” are multiple and can be contradictory if one does not pay enough attention to the history of the script as well as to the history of the pertinent scholarly tradition.

grammatology and digital technologies

233

In Bunz 2000 we find also a road-map of possible strategies for the encoding of Cuneiform (p. 25). One possibility is script-based. The other is language-based. Both can be subdivided into three different approaches.

(T3): Bunz 2000 category C1 encoding methods20

encoding methods

(a) script based: (b) language specific:

- minimal element to be composed by a rendering engine

1. minimalistic - representation by Latin characters with mark-up

- unified syllabary, i.e. precomposed syllabic characters

2. intermediate - syllabaries

- unified paleographic database

3. maximalistic - paleographic database

1.b coincides with a transcription using formatting or mark-up means to describe the nature of the signs and the language used. 2.a is more or less what is now available in the Unicode standard. To add paleographic and/or language information we can design individual fonts, with all the caveats already expressed. This is why I consider the encoding of Cuneiform to resemble more the encoding of the alphabets in the standard ISO 8859-x rather than ISO 10646-UCS-x.

Within ISO-8859-x we had to change fonts for every alphabetical script traditions. In the same way we have to change fonts for every cuneiform script traditions, but the original idea of Unicode was specifically to avoid the code-sharing of 8859-x.

2.3 A first overview We can sum up differences and similarities in the

methods of the two standards.

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

234

(T4)

8859-x alphabets share a 256 code points table

10646-x (a) some alphabets do not share any code point (b) some alphabets share a coding range (mainly historic scripts)

10646-x cuneiform shares a 1152 code points range21

The distinction ‘script-based’ vs. ‘language-based’, if

taken loosely, can be applied also to the historic alphabets we mentioned in the preceding sections. Old Italic would be ‘script-based’, while Old Semitic would be ‘language-based’. As a matter of fact, however, Old Semitic has a double possibility. The code range of Hebrew has already been used to map glyphs that correspond to Phoenician, Aramaic etc.22 This is also interesting also because the Hebrew script has a tradition as a mean of transliteration for Old Semitic scripts.23 We try to organize the different solutions taken in the following table.

(T5)

script based mapping of pertinent glyphs (may require mark-up and specific software to recognize the language and the paleographic level automatically)

Old Italic

language based

notational units correspond to the character repertoire of a specific written language

Carian Lydian Lycian

double according to different requirements one written language is or is not represented by an independent character repertoire

Old Semitic

3. On the function of the encoding

The encoding of cuneiform is not really meaningless. Perhaps we first have to remember that all this is conditioned by

grammatology and digital technologies

235

conceptual/cultural precomprehensions and aims that are per force different from the ones that led to the historical formation of the single cuneiform scripts. The observations in Bunz 2000, however, are still in largely valid, because the essence of the discipline is epigraphical and the document as a whole is (or should be) the center of the research. It would be a very long procedure to represent the co-occurrence of Hittite and Mittannian graphs in some Hittite documents such as KBo 1.224 or the letters sent from the Hattusa court to Assyria (e.g. KBo 1.14) and in general the so-called ‘mixed Mittanni-Middle Assyrian’ script with specific fonts. However, to distinguish within the Hittite documents which texts have a Syrian25, Mittannian script, Middle Assyrian, or Hittite script and what relation we can find among scripts and languages are also of great importance for essays dedicated to the general public. If the aim is to publish online cuneiform documents in electronic text format (‘plain txt’-based) able to show such differences, a separate encoding for written language would be more practical, but still a long and almost useless job.

Nonetheless it is my firm opinion that an abstract coded character set can be meaningful, if we only look outside of the realm of printing, be it digital, paper based, online, traditional... Such an unequivocal, universal, standardized encoding becomes useful and practical for the research agenda once it is linked to the pertinent single instances in an electronic corpus where the single instances of the script are 3D vector-based reproductions. This would be a matter of mark-up within 3D objects, mapping the single signs to their unique digital ID.26 A database of unique IDs for notational units that set aside the different contextual values can be useful for a computational-based and/or -oriented research. Some of the possible applications include: (a) searching for clusters of signs without specifying all the possible values of a unit; (b) automated databases of mapped notational units and contextual values for comparative

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

236

aims among different cuneiform written languages; (c) probability algorithms for text restoration; (d) parsing engines for the the evaluation of false input; (e) statistical and computational analysis such as rank/frequency distributions and many other more complex applications.

I hope I could give some explanations here for the scientific need of good electronic corpora. But to go back to the problem of the definition of ‘character’, it should be evident that in this section the concept shifted from the linkage to a «smallest component of written language that has semantic value» to a pure (aggregational?) abstraction of shapes and functions. In so doing we get closer to the ‘real’ meaning of ‘character’ in Unicode and we can also try to comment briefly upon the relationship of this meaning to the problem of defining independent scripts.

4. Towards a conceptual solution

4.1. Unicode characters between technology and ideology

In both BMP and SMP of UCS we find at least two different ways of defining scripts. Modern written languages are normally grouped so that multiple written languages fall together into a single script, e.g., Latin, or Cyrillic. Ancient written languages are sometimes treated in the same way, sometimes one single written language corresponds to one script, in the sense that it receives a dedicated code range. Ancient written languages, so to say, sometimes present problems in the definition of their corresponding independent scripts. One reason for this is very simple. Written languages that came to us through a normalized tradition (relatively old or recent) are somehow naturally admitted into the rules of a system that is, in principle, still a typographic one. So Latin or Ancient Greek do not really represent a problem as long as the major and more requested documents27 have an established typographic tradition. We do not have a normalized ‘academic’

grammatology and digital technologies

237

cuneiform script and it would be non-sense to develop one.28 So after having tried to uncover some of the reasons that

led to the discussion in defining independent code ranges, it may be the time to address again the problem of what is a ‘character’ and what is a ‘script’.

The “real” definition of character in Unicode is the definition of ‘abstract character’ and can be found in ch. 3 of the current Unicode Standard:

«Abstract character: A unit of information used for the organization, control, or representation of textual data.»

In the light of this definition, a problem like whether the

Aramaic and the Phoenician letter aleph should be distinct characters or not is, technically, always solved. Ideologically, probably never.

The ideological problem lies not in what is a character, but in what deserves to be a character. Are Umbrian and Venetic distinct scripts? Probably yes, but do they deserve distinct code ranges? To answer this question one must follow precise recommendations for the encoding, consult specialists and keep in mind, as limpid as possible, the aims of the encoding not only in technical processes, but also in social, cultural, scientific and sometimes even religious and political contexts.

Another important recognition of Bunz 2000 is that the encoding of a dead script is always revisable.29 “Not a standard”, in the terms of Bunz 2000, a “scientific revisable standard” in the terms of this paper.

4.2. The definition of independent scripts

We are left now with the problem of the definition of distinct scripts. A question that somehow receives a new input from the consequences of the Unicode encoding process.

A first point is that the character is not the grapheme. This is quite evident, but do ‘character’ and ‘grapheme’ both

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

238

pertain to the script level? Should the ‘character’ unproble-matically pertain to the script level we would not have had any occasion to write this paper. In fact, if the real problem is to designate what deserves to be a character, and consequently, what is an independent script, we have to try to understand better what could ‘script’ mean. The difference between the grapheme and the character is that the grapheme is a scientific problem, the character is not. In the light of the definition quoted above (§4.1) the character presents no gnoseological problem. It is more a question of organizing the material to be encoded in order to be useful for present and, possibly, future goals. The scientific aspect concerns what is an independent script, or more generally, what is an independent writing system. While the grapheme has, even if not exclusively, precise glottic aspects, the character does not. While the grapheme turns, so to say, potential values into actual ones, the character only subsumes distinct visual shapes into a class.

The grapheme has analyzable applications in the different layers of a graphically-encoded message. It may be necessary to explain how ‘grapheme’ is intended to be used here. With ‘grapheme’ I only mean a predicative function. ‘X is a grapheme’ means thus nothing more than ‘X is a graphic mean with a distinctive function in all pertinent levels’. So ‹p› and ‹t› in pin and tin are ‘graphemes’. But the letter ‘p’ and ‘t’ alone are not. The letter distinction works also at a lower level where ‘grapheme’ is not a pertinent concept.

(T6) Layers of a written language message

30

communicative 4. pragmatic

3. labeling

2. phonemic graphemic{

glottic {

1. phonic

grammatology and digital technologies

239

1. Any graphic sign (or character?)31 is a set of articulatory instructions32. 2. The signs are brought together to build syllables and through syllables (potentially) all the morphs of a language.33 This is the first level of graphematic pertinence. The graph(em)ic strings recode phonemic strings.34 3. Strings of signs play a distinguishing role at a higher lexical or grammatical level. Most typically, here, determinatives disambiguate graphemic strings and as a consequence the morphs or their content. A banal example: Italian ‘anno’ vs.

‘hanno’;35 Sumerian ��, ��, uzuti, gišti.36

4. The selection of signs at this level, that is here labeled ‘pragmatic’, aims at producing certain reactions, at organizing the information, at establishing social statuses and many others. Clear examples can be found in the Anatolian Hieroglyphic system where a strong iconic variant can be used for a personal name; or the selection of variants within a document can be justified on iconic grounds with reading directions independent of the linguistic one and so on.37

At this level the socio-cultural context becomes decisive

and the graphemic function is to be understood only within this broader context. With ancient documents we can sometimes perfectly understand that a sign is ‘graphemic’ in this sense, but we can hardly reconstruct exactly how. One example can be represented by the sign selection for the royal names in the Hittite empire written in Anatolian hieroglyphs.38

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

240

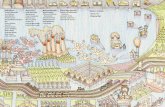

(T7) Iconic links among the last Hittite kings

(from Herbordt – Bawanypeck - Hawkins 2011)

The figure shows a seal impression of Tuthalija IV and

one of Arnuwanda III. In the middle field we see a deified mountain. Both Tuthalija and Arnuwanda are, besides anthroponyms, oronyms.39 In the seal 97.1 the name of Tuthalija is written with the logogram MONS₂, disambiguated by the TU sign beneath.40 In the seal of Arnuwanda (138.2) the name is syllabically written.41 MONS₂, in both istances, surely plays also non glottic roles. A symbol of continuity with the predecessor in Arnuwanda’s seal is almost certain.42 More interesting, but, more difficult to confirm, is that with Tuthalija IV, for the first time, a royal name is written with a sign visually depicting a god and this may be of interest for the hypothesis of an ongoing process of deification of the kings.43

Finally we can now briefly add something about the

definition of independent scripts. Some interesting premises and insights in this problem can be found in Prosdocimi 1990,44 where the question of writing within the teaching/learning process is addressed. Writing has two essential features, conventionality and totality. A writing is ‘total’, in a first meaning, because it tends to express all that is expressed in a language. In a second meaning, as a system, a writing cannot

grammatology and digital technologies

241

admit deficiencies, otherwise the system collapses. That is to say that the system can be non-optimal, but it is always total. It is a matter of dynamic relationship between economy and redundancy.45 As long as a writing is conventional, it has to be learned and taught. Among the dynamics of teaching/learning we have to place the problem of the transmission of a system and to evaluate wheter the script is adapted in such a way that it can be termed ‘new’ or ‘independent’.46 The foundations of a writing system are placed in its proper rules of usage. If we take for example the Old Italic scripts, we noticed that they are generally treated as independent of their Greek origin. The Etruscan mediation plays a significant role. The rules given in teaching for using an alphabet for the sake of expressing a language (e.g. Etruscan) separate this script from its origin.47 Now, the teaching process is to be understood in a cultural dimension, so that the rules of usage can refer to many levels, depending on how and to what degree writing is important in a specific cultural environment.48 These thoughts are also valid, more or less, for defining at once the boundaries of the cuneiform applications (cuneiform written languages) and their common ‘meta-rules’ (cuneiform notational system). Prosdocimi 1990, p. 160:

«Nell’alfabeto umbro ci sono due grafi caratterizzanti, e ciò è la sphragis di umbricità; ma l’alfabeto, anzi gli alfabeti umbri seguono pari pari le evoluzioni dei contigui alfabeti etruschi, così da dover pensare a comuni scuole scrittorie, fondamentalmente etrusche, con regole suppletive per notare l’umbro: si ritorna al concetto centrale di scrittura come ‘scuola’ di scrittura.»

This system may be tentatively schematized separating the

concepts ‘notational system’, ‘script’ and ‘written language’. A notational system gathers meta-rules from which different applications can be derived. A script may be such an appli-cation, making a notational system able to express a language conventionally and totally. In this sense I would tend to speak of

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

242

one cuneiform ‘notational system’, but different cuneiform scripts that embody different languages as written languages.

This, I think, can also explain some ambivalence in the definition of scripts in the Unicode encoding. Different scripts are closer, while others are more remote applications of an original notational system. In the story of the different applications new notational systems may arise from older ones. Especially when shapes and rules simultaneously convey definitions of socio-cultural identity.

In the light of what is proposed here, English and Italian, for example, may be considered different scripts. English ‘home’ and Italian ‘chele’ show an astonishing diversity of rules.49 The different articulatory instruction of ‘h’ is the least interesting. Much more important is the usage of the final ‘e’ that in English marks the preceding ‘o’ as long, thus attesting a determinative that operates backwards and crosses other notational units. This makes clear that the rules of the two systems may have developed from a common origin, but currently show a great gap.

I conclude with a graphic representation of the concept of ‘script’ as the interface level between notational system50 and language in the formation of a written language.

NOTATIONAL SYSTEM

(META -RULES) Shapes potential values

↓↓↓↓

LANGUAGE →→→→

(RULES)

SCRIPT (INTERFACE LEVEL )

Shapes Values

⇒⇒⇒⇒ WRITTEN LANGUAGE

grammatology and digital technologies

243

5. The ‘Unicode’ opportunity

This paper tried to describe some interesting ambiguities in the encoding of Unicode and took the occasion to offer a simple model for the relationship of concepts such as ‘notational system’, ‘script’ and ‘written language’. There are also at least two practical results.

1. Unicode strongly reveals much of the typical alphabetocentrical prejudices,51 but it gives an unrivaled opportunity for scholars to regain the use of the traditional scripts, provided that there is a consensus on a normalized script.

2. The process of the assignment of unique code points can be understood as a collection of unique IDs for computational research.

∗ A. The fonts used in the table T1 and T2 are taken from: 1. “Ancient Semitic Scripts”, culmus.sourceforge.net/ancient/index.html

2. zhmono.sourceforge.net/ (zhmono.otf);

3. www.alanwood.net/unicode/fonts-middle-eastern.html#zavesta (zavesta.ttf);

4. Unicode Fonts for Ancient Scripts, users.teilar.gr/~g1951d/ (aegean.ttf);

5. Unicode Cuneiform Fonts, Sylvie Vanséveren, www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/cuneifont/ ;

6. Cuneiform fonts for TeX/LaTeX/PDFLaTeX Karel Piska, www-hep2.fzu.cz/~piska/cuneiform.html.

B. Scans in T2 are taken from: 1. Archaic cuneiform, Labat 1948;

2. Hurrian, Dietrich/Mayer 2010;

3. Elamite, Steve 1992.

1 I wish to thank the editors of this volume for granting me

the occasion of remembering Günter Neumann. O. Carruba ‘sent’ me to Würzburg in 2002 when I could spend some days with G. Neumann

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

244

discussing about Sidetic, Carian, Luvian and other micrasiatic languages and scripts. Once I reached his home, he was waiting for me at the door and as he saw that, unexpectedly, my friend A. Intilia was also approaching, he did not greet us. He turned inwards and smiling said to his wife: «eine Tasse mehr». Many thanks to G. Müller, C. Mora, P. Cotticelli, O. Carruba. Charles Steitler was so nice to help me with English. I hope this paper will not disappoint them too much.

2 www.unicode.org/glossary/ [25mar2012]. 3 Written language: a simplified functional metalanguage.

This definition is taken from M. Barbera’s online Introduzione alla linguistica generale, www.bmanuel.org/corling/corling_idx.html, cap. 1.6.

4 Which is actually a rather complicated issue. The Sumerian written language of the Sumerians (III mill. B.C.) may actually be considered as independent from the Sumerian written language of the Assyrians and the Babylonians (I mill. B.C.). This problem cannot be treated here.

5 The advantage of ISO-8859-x was to give for each written language a standard coded character set.

6 Ancient Semitic Scripts. culmus.sourceforge.net/ancient/ index.html.

7 I am citing from the ‘readme.txt’ file included in the font package [3/2012].

8 Intermediate passages and mediation are not relevant here. 9 For all: Wallace 2007, p. 6. 10 Unicode Technical Committee. 11 Little 2011, p. 6. I am not sure I reproduced exactly the

same glyphs used in the original document, but this is not so important. The font used for the glyphs is D. J. Perry’s Cardo 1.04 (scholarfonts.net).

12 Cf., however, at least Everson - Feuerherm - Tinney 2004 and consult the website of the Initiative for Cuneiform Encoding. www.jhu.edu/digitalhammurabi/ice/ice.html.

13 Bunz 2000, p. 12. 14 Bunz 2000, p. 14. 15 E.g. Old Persian, Bunz 2000, pp. 17-18.

grammatology and digital technologies

245

16 E.g. Egyptian Hieroglyphs, Bunz 2000, pp. 20-21. 17 Bunz 2000, p. 24. 18 Bunz 2000, p. 18. 19 Not for word processors. 20 Bunz 2000, p. 25. 21 Cuneiform: 1024 code points (range: 12000-123FF) +

Cuneiform numbers and punctuation: 128 code points (range 12400-1247F).

22 Cf. supra §2.1. 23 Contrast Friedrich 1932, pp. 109-110 and Gusmani 1964,

p. 250 (Aramaic-Lydian inscription). We cannot treat here the complex and fascinating history of such a change in the transliteration methods.

24 Treaty with Šattiwaza of Mittanni, Akkadian version. 25 Klinger 2003. 26 This link needs not to be direct. The signs of a document

can be at first described for their content as ‘interpreted graphic units’, i.e. with their value in the document, and then, through concordances, being retrievable as ‘un-intepreted graphic unit’, i.e. avoiding a pre-selection of a contextual value. On interpreted vs. uninterpreted graphic units, with consequences for the computational research, see, e.g. Giusfredi - Rizza 2011.

27 Epigraphical documents, on the other hand, arise the same questions as Old Italic, Old Semitic, cuneiform, etc.

28 In this sense see already Bunz 2000. Another question is, however, as said above, the definition of a standard of unique IDs.

29 Bunz 2000, p. 7. 30 Only a simplified model is here described. Cf., for more

complex models, e.g., Robertson 2004 and the recent overview Marazzi, forth. The background from which this notes come is mainly in the line of Gelb 1963, DeFrancis 1988, Prosdocimi 1990, Daniels - Brigth 1996.

31 Or ‘gram’, alfabetogram, syllabogram, logogram. 32 Including the instruction: «do not articulate». Correspond

to the γράµµατα in Aristotle’s de interpretatione, 16a. Only a very quick reference to a grammatology of Aristotle can here be made, but it has a significant role within a project on the metalanguage of

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

246

linguistics to which the author is linked (PRIN, Unit of the Univ. of Verona).

33 Prosdocimi 1990, pp. 170-187. 34 Aristotle’s τὰ γραφόµενα as symbols of τὰ ἐν τῇ φωνῇ,

i.e. the content of a string of φωναὶ, the symbols of the παθήµατα ἐν τῇ ψυχῇ. It may be worth remembering that some scripts tend to aggregate allophonic variations, some tend to keep them distinct.

35 ‘year’ vs. ‘they have’. ‘h’ has no phonetic realization (articulatory instruction: do not articulate).

36 ‘rib’, ‘arrow’. 37 For all: Marazzi 2010, with previous references. 38 For a reconstruction of the development of the iconology

of royal names in Hieroglyphic Anatolian in the last phase of the Hittite empire: Bolatti Guzzo 2004.

39 Cf. del Monte - Tischler 1978, p. 39, 446; del Monte 1992, p. 12.

40 SOL2 MONS2-tu MAGNUS.REX IUDEX-la. 41 SOL2 AVIS3-nú-tá MAGNUS.REX IUDEX-la. 42 For the problems Tuthalija IV had in assuring his own

descendant line, cf. Giorgieri - Mora 1996. The brother and successor of Arnuwanda III, Suppiluliuma II seems to use MONS2 in (at least one of) his seals. Marazzi 1991, fig. 26. Non vidi Herbordt 2006.

43 For a discussion about this hypothesis, cf. Giorgieri - Mora 1996, pp. 77-79, with relevant references.

44 Grounded on preceding papers. 45 Prosdocimi 1990, pp. 157-158. 46 Prosdocimi 1990, p. 158: «Di solito si focalizza la

trasmissione in un punto o punti cruciali, e cioè quando un alfabeto che nota una lingua viene impiegato con adeguamenti per notare un’altra lingua; vi è correlata la questione di quando, se e come si possa o si debba parlare di alfabeto nuovo (autonomo o simili)».

47 Prosdocimi 1990, p. 159: «Come in ogni scrittura, nell’alfabeto è fondamentale il concetto di regola d’uso, spesso sottovalutata in rapporto agli aspetti formali: un alfabeto di VII a.C. è etrusco e non greco non tanto per le forme ma per le regole d’uso che sono date nell’insegnarlo per l’uso etrusco.»

grammatology and digital technologies

247

48 Prosdocimi 1990, p. 159: «Le regole d’uso possono

attingere vari livelli e avere meccaniche di trasmissione diverse a seconda della posizione qualitativa e quantitativa della scrittura nella società: la frequenza di lettura e di scrittura può separare o annullare l’oralità della scrittura [...]». On the relation among readers/writers (production/response) cf. etiam Houston 2008.

49 Italian ‘h’ conveys here the instruction: select in ‘c’ the articulation [k] instead of [ʈʃ].

50 A notational system needs not to be restricted to recoding processes starting from (spoken) language. For a brief overview of some notational systems for non linguistic messages cf. Hill Boon 2004.

51 Cf. Perri 2009.

References

BAINES – BENNET – HOUSTON 2008 J. Baines – J. Bennet – S. Houston (eds.), The disappea-

rance of writing systems. Perspectives on literacy and commu-nication, London 2008.

BECKMAN 1993 G. Beckman, Some observations on the Šuppiluliuma -

Šattiwaza treaties, in M.E. Cohen – D.C. Snell – D.B. Weisberg (eds.), The tablet and the scroll. Near Eastern studies in honor of William W. Hallo, Bethesda 1993, pp. 53-57.

BECKMAN 1999 G. Beckman, Hittite Diplomatic Texts. Second Edition

(Society of Biblical Literature Writings from the Ancient World, 7), Atlanta 1999.

BOLATTI GUZZO 2004 N. Bolatti Guzzo, La glittica hittita e il geroglifico anato-

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

248

lico, in M. Marazzi (ed.), Centro Mediterraneo Preclassico. Studi e ricerche I (Quaderni della Ricerca Scientifica, 2), Napoli: Università degli studî Suor Orsola Benincasa, 2004, pp. 215-306.

BUNZ 1998 C.-M. Bunz, Unicode and Historical Linguistics, Studia

Iranica, Mesopotamica et Anatolica 3, 1998, pp. 41-65.

BUNZ 2000 C.-M. Bunz, Encoding scripts from the Past: conceptual

and practical problems and solutions, 16th & 17th International Unicode Conference, Amsterdam & San Jose 2000.

DANIELS – BRIGTH 1996 P.T. Daniels – W. Brigth, (ed.), The world’s writing

systems, Oxford 1996.

DEFRANCIS 1989 J. DeFrancis, Visible Speech: the diverse oneness of

writing systems, Honolulu 1989.

DIETRICH – MAYER 2010 M. Dietrich – W. Mayer, Der hurritische Brief des

Dusratta von Mittanni an Amenhotep III. : Text, Grammatik, Kopie (Alter Orient und Altes Testament 382), Munster 2010.

EVERSON – FEUERHERM – TINNEY 2004 M. Everson – K. Feuerherm – S. Tinney, Final proposal

to encode the Cuneiform script in the SMP of the UCS. Working group document. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2786. L2/04-189.

FRIEDRICH 1932 J. Friedrich, Kleinasiatische Sprachdenkmäler, Berlin 1932.

GELB 1963 I.J. Gelb, A study of writing. Revised edition, Chicago 1963.

grammatology and digital technologies

249

GIORGIERI – MORA 1996 M. Giorgieri – C. Mora, Aspetti della regalità ittita nel

XIII secolo a.C. (Biblioteca di Athenaeum 32), Como 1996.

GUSMANI 1964 R. Gusmani, Lydisches Wörterbuch, Heidelberg 1964.

HERBORDT 2006 S. Herbordt, The Hittite Royal Cylinder Seal of Tuthaliya

IV with Umarmungsszene, in P. Taylor (ed.), The Iconography of Cylinder Seals. Colloquium at the Warburg Institute on October 18 and 19, 2002 (Warburg Institute Colloquia 9), London - Turin, 2006, pp. 82-91.

HERBORDT – BAWANYPECK – HAWKINS 2011 S. Herbordt – D. Bawanypeck – J.D. Hawkins, Die Siegel

der Großkönige und Großköniginnen auf Tonbullen aus dem Nişantepe-Archiv in Hattusa (Boğazköy-Ḫattuša, 23), Darmstadt 2011.

HILL BOONE 2004 E. Hill Boone, Beyond writing, in Houston, Stephen D.

(ed.), The first writing. Script invention as history and process, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 313-348.

HOUSTON 2004 S.D. Houston (ed.), The first writing. Script invention as

history and process, Cambridge 2004.

KLINGER 2003 J. Klinger, Zur Paläographie akkadischsprachiger Texte

aus Ḫattuša, in G. Beckman – R. Beal – G. McMahon (eds.), Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the occasion of His 65th birthday, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 237-248.

LABAT 1948 R. Labat, Manuel d’épigraphie akkadienne (Signes,

mondo anatolico e vicino oriente

250

Syllabaire, Idéogrammes), Paris 1948.

LITTLE 2011 C.C. Little, Proposal to encode additional Old Italic

characters, Working Group Document. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4046, L2/11-146R.

MARAZZI 1991 M. Marazzi, Il cosiddetto geroglifico anatolico: spunti e

riflessioni per una sua definizione, Scrittura e civiltà 15, 1991, pp. 31-77 (with 41 fig.).

MARAZZI 2010 M. Marazzi, Scrittura, percezione e cultura: qualche

riflessione sull’Anatolia in età ittita, Kaskal 7, 2010, pp. 219-255.

MARAZZI (forth.) M. Marazzi, Lingua vs. scrittura: storia di un rapporto

difficile (forthcoming).

DEL MONTE - TISCHLER 1978 G.F. del Monte – J. Tischler, Die Orts- und Gewässer-

namen der hethitischen Texte, Wiesbaden 1978.

DEL MONTE 1992 G.F. del Monte, Die Orts- und Gewässernamen der

hethitischen Texte. Supplement, Wiesbaden 1992.

MORA – GIORGIERI 2004 C. Mora – M. Giorgieri, Le Lettere tra i re ittiti e i re

assiri ritrovate a Hattuša (History of the Ancient Near East/Monographs, VII.), Padova 2004.

PERRI 2009 A. Perri, Aldilà della tecnologia, la scrittura. Il caso

Unicode, Annali di ateneo. Università degli studî Suor Orsola Benincasa 2009/2, pp. 725-748.

grammatology and digital technologies

251

PROSDOCIMI 1990 A.L. Prosdocimi, Insegnamento e apprendimento della

scrittura nell’Italia antica, in M. Pandolfini – A.L. Prosdocimi (eds.), Alfabetari e insegnamento della scrittura in Etruria e nell’Italia antica (Biblioteca di Studi Etruschi, 20), Firenze 1990, pp. 155-298.

ROBERTSON 2004 J.S. Robertson, The possibility and actuality of writing, in

S.D. Houston (ed.), The first writing. Script invention as history and process, Cambridge 2004, pp. 16-38.

STEVE 1992 M.-J. Steve, Syllabaire élamite. Histoire et paléographie,

Neuchâtel 1992.

VOOGT – FINKEL 2010 A. Voogt – I. Finkel (eds.), The idea of writing : play and

complexity, Leiden-Boston 2010.

WALLACE 2007 R.E. Wallace, The Sabellic languages of Ancient Italy

(Languages of the World/Materials, 371), Muenchen 2007.