Grain Yields and Agricultural Practice at the Castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

Transcript of Grain Yields and Agricultural Practice at the Castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

sous la direction de Catherine Verna et de Pere Benito

TOME XXVI 2013-2014

PVP : 30 €

9 782849 741764

ISBN 978-2-84974-176-4

TOM

E XX

VI20

13-2

014

ÉTVD

ES R

OVS

SILL

ON

NAIS

ES

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence

XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

couv erouss26.indd 1 21/11/13 14:19

4

Études Roussillonnaises, Revue d’HistoiRe et d’aRcHÉologie MÉditeRRanÉennes

Revue fondée en 1951 par Pierre PonsicH, annie de Pous, Marcel duRliat

directeurs de la revue

Pierre PONSICH, 1951 - † 23 décembre 1999 (1ère et 2e séries)

Claire PONSICH depuis 2000 (2e et 3e séries)

comité de lecture

Préhistoire et archéologie (dir. Françoise CLAUSTRE, CNRS-Centre d’Anthropologie de Toulouse, † 6 septembre

2006, Jean ABELANET, Musée de Tautavel et AAPO; Jean GUILAINE, Collège de France, Chaire de Néolithique)

Ramon BUXÓ (Musée archéologique de Gérone); Jean GASCO (Collège de France, Université de Toulouse-Le-Mirail);

Araceli MARTIN (Generalitat de Catalunya); Dominique SACCHI (CNRS, Centre d’anthropologie), Narcis SOLER I

MASFERRER; Enriqua PONS; Josep TARRUS; Jean VAQUER (CNRS, Centre d’anthropologie).

antiquité et archéologie (dir. Christophe PELLECUER, DRAC-Languedoc-Roussillon-Direction archéologique)

Fabienne COUDIN (Université de Pau); Pierre GARMY (CNRS), Rémy MARICHAL (Musée de Ruscino, †), Thierry

ODIOT (DRAC, Languedoc-Roussillon); Jean-Claude RICHARD (CNRS).

Moyen Âge (dir. Anscari Manual MUNDÓ I MARCET, IEC et Université de Barcelone; Michel ZIMMERMANN, Uni-

versité de Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en Yvelines, IEC de Barcelone).

Raphaela AVERKORN (Université de Hanovre), Alexandra BEAUCHAMP, Université de Limoges), Dominique BI-

DOT-GERMA (Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, ITEM), Pere BENITO I MONCLUS (Université de Lérida),

Pau CATEURA BENASSER (Université des Îles Baléares), Sylvie CAUCANAS (Archives Départementales de l’Aude),

Martine CHARAGEAT (Université de Bordeaux, Framespa), Pierre CHASTANG (Université de Versailles-Saint-Quen-

tin-en-Yvelines), Claude DENJEAN (Université de Toulouse, Framespa), Claude GAUVARD (Institut Universitaire de

France, Paris I-Panthéon Sorbonne, Lamop), Christian GUILLERÉ (Université de Chambéry), Christiane KLAPISCH-

ZUBER (EHESS), Véronique LAMAZOU-DUPLAN (Université de Pau, Framespa-ITEM), Marie-Claude MARAN-

DET (Université de Perpignan, CHRISM), Hélène MILLET (CNRS, Lamop-Paris I-Sorbonne), Stéphane PÉQUIGNOT

(Casa Velazquez, EPHE), Claire PONSICH (Lamop), Carole PUIG (CHRISM), Flocel SABATÉ (Université de Lérida),

Claire SOUSSEN (Université d’Evry, Framespa), Catherine VERNA (Université de Paris VIII, Framespa-UTAH).

Période moderne (dir. Raymond SALA, ICRESS et Université de Perpignan, Eva SERRA, Université de Barcelone)

Denis FONTAINE (Archives Départementales, Perpignan), Christine LANGÉ (Archives Départementales et Antiquités

et Objets d’Art des P.-O.), Gilbert LARGUIER (Université de Perpignan), Joan PEYTAVI I DEIXONA (ICRESS et Uni-

versité de Perpignan, IEC de Barcelone), Antoine de ROUX (Géographie historique).

Période contemporaine (dir. Jean SAGNES, Université de Perpignan) André BALENT (ICRESS et Université de Perpignan), Fernand BELLEDENT (SASL des P-O), Etienne FRESNAY,

Antoine de ROUX (Géographie historique).

Histoire de l’art (dir. Rosa ALCOY, Université de Barcelone, Françoise ROBIN, Université de Montpellier) François AMIGUES (Université de Perpignan), Pere BESERAN (Université de Barcelone), Laurence CABRERO (Uni-

versité de Montpellier), Jordi CAMPS I SORIA (MNAC de Barcelone), Immaculada LORES I OTZET (Université de

Lérida), Montserrat PAGÈS I PARETAS (MNAC de Barcelone), Francesc QUILES (MNAC de Barcelone).

Philologie et littérature catalane et hispanique (dir. Marie-Claire ZIMMERMANN, Université Paris IV-Panthéon-

Sorbonne, CEC de Paris IV et IEC de Barcelone)

Sopie HIREL (Université de Paris IV-Sorbonne), Josep MORAN (Université et IEC de Barcelone), Miquela VAILLS

(ICRESS et Université de Perpignan).

Patrimoine (dir. Christine LANGÉ, Archives départementales et Antiquités et Objets d’Art des P-O, Raymond SALA

Université et ICRESS de Perpignan, Patrimoine de la Ville)

Jean-Luc ANTONIAZZI (ASPHAR), Laurent FONQUERNIE (APHPO), Edwige PRACA (APHPO), Madeleine

SOUCHE (Université de Perpignan, APHPO), Jean-Louis VAILLS (ICRESS de Perpignan).

ethnologie Martine ARINO, Jean-Louis VAILLS (ICRESS de Perpignan)

traducteurs Jeanne ANTCZAK (anglais), Jed ENGLISH (anglais), Amin ERFANI (anglais, Université d’Atlanta), Mi-

quela VAILLS (catalan, Université et ICRESS de Perpignan), Marie-Claire ZIMMERMANN (catalan, castillan, Univer-

sité Paris IV-Panthéon- Sorbonne, CEC de Paris IV et IEC de Barcelone).

Photographie Jean-Louis VAILLS

site de la revue http://www.etudesroussillonnaises.com

Erouss25.indb 4 19/11/13 15:22

5

Études Roussillonnaises, Revue d’Histoire et d’archéologie Méditerranéennes

savoirs des campagnes catalogne, languedoc, Provence

Xiie-Xviiie siècles

sous la direction de

catherine veRna (Université Paris 8)

Pere Benito (Universitat de Lleidà)

Erouss25.indb 5 19/11/13 15:22

7

Savoirs des campagnes Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence. XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

Table des matièresMobiliser des savoirs dans les campagnes médiévales et modernes (Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence) ���������� 9Catherine Verna et Pere Benito

La médecine en milieu rural dans la Couronne d’Aragon au Moyen Âge ��������������������������������������������������������15Carmel Ferragud

Llevadores, guaridores i fetilleres� Exemples de sabers i pràctiques femenines a la Catalunya medieval ��������23teresa Vinyoles i Pau Castell

Els sabers útils al món rural català medieval : agricultura, menescalia, medicina i conservació dels aliments ����33lluís CiFuentes i Comamala

Deux ecclésiastiques (Miquel Agustí, l’abbé Marcé), deux moments du « savoir des campagnes » ����������������51gilbert Larguier

Grain Yields and Agricultural Practice at the Castle of Sitges, 1354-1411 �������������������������������������������������������65adam Franklin-lyons

Une expertise en Camargue en 1405� Bertrand Boysset et le bornage du vallatus vetus ����������������������������������79Pierre Portet

À la croisée des savoirs et des époques : le compoix de Saint-Germain-de-Calberte (Cévennes) de 1579 ������95Bruno Jaudon

L’aprenentatge de lletra en el món rural segons els Registra ordinatorum del bisbat de Barcelona, anys 1400-1500� Escolars i tonsurats ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 105Josep Hernando i delgado

Des savoirs sur les marchés des campagnes de la Couronne d’Aragon aux XIIIe et XIVe siècles��������������������115Claude DenJean

Savoirs monétaires, technique comptable et réseaux commerciaux en Andorre au XVIIe siècle �������������������� 129olivier Codina Vialette

Travail et techniques des bouchers et des poissonniers dans la Catalogne rurale (XIVe et XVe siècles) ��������� 145ramón a. Banegas lóPez

El saber i l’experiència dels sards al servei de l’explotació de les mines d’argent de Falset (1342-1358) ����� 153albert martínez elCaCHo

El transvasament de coneixement Nord-Sud: vidriers del Rosselló, Llenguadoc i Provença al sud dels Pirineus durant la primera meitat del segle XIV ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 163miquel Àngel Fumanal Pagès

L’Areny de la Sal: una aproximació a les Salines de Cardona des dels mercats ultrapirinencs (XII-XVIII) ������ 169andreu galera i Pedrosa

VARIA Activités maritimes, commerce et essor industriel : les échanges empordano-majorquins de 1280 à 1350 ��� 193anthony Pinto

savoir intro.indd 7 28/11/13 09:18

65

gRAIn yIeLdS And AgRICuLtuRAL PRACtICe At tHe CAStLe oF SItgeS, 1354-1411

Adam FRAnKLIn-LyonS(Marlboro College, United States)

aBstRact

For the second half of the fourteenth century, the Cathedral Almoina of Barcelona maintained a series of managerial records for some of its agricultural properties that illuminates agricultural practices that were both rational and highly productive. The most comprehensive documents come from the managers of the castle of Sitges, where agricultural activities involves frequent use of wage labor, high levels of capital input, irrigation, and evidence of the marketing of manure. These practices often produced high yields of staple grains – averaging over 12:1 for barley over decades. The records detail a different vision of agriculture production than is usually associated with the fourteenth century, providing a possible corrective to the gloomy forecasts that predominate in the literature.

RÉsuMÉ

Pour la seconde moitié du XIVe siècle, l’Almoina de la cathédrale de Barcelone a conservé une série de livres d’administration correspondant à certains de ses domaines qui éclairent des pratiques agricoles rationnelles et hautement productives. La série la plus FRKpUHQWH�SURYLHQW�GHV�JHVWLRQQDLUHV�GX�FKkWHDX�GH�6LWJHV��R��OHV�DFWLYLWpV�DJULFROHV�VH�IRQGHQW�VXU�O¶HPSORL�IUpTXHQW�GX�WUDYDLO�VDODULp��un haut niveau d’investissement, l’usage de l’irrigation et la commercialisation du fumier. Ces pratiques ont souvent abouti à des rendements élevés pour les céréales de base (une moyenne de 12:1 pour l’orge sur plusieurs décennies). Ces registres offrent, ainsi, une image de la production agraire assez différente de celle qui est fréquemment associée au XIVe siècle, fournissant un possible correctif aux pessimistes prévisions qui prédominent dans l’historiographie.

ResuM

Per a la segona meitat del segle XIV, l’Almoina de la catedral de Barcelona conserva sèries de llibres d’administració d’alguns dels seus dominis que il·luminen pràctiques d’agricultura racionals i altament productives. La sèrie més coherent de llibres de comptes procedeix dels administradors del castell de Sitges, on les activitats agràries incloïen sovint el recurs a mà d’obra assalariada, fortes inversions de capital, pràctiques d’irrigació i evidència de l’existència d’un mercat d’adobs naturals. Aquestes pràctiques produïren sovint alts rendiments dels principals cereals –una mitjana de 12:1 per a l’ordi al llarg de diversos decennis. Els registres ofereixen una imatge de la producció agrària diferent de la que normalment s’associa al segle XIV i aporten un possible correctiu a les pessimistes prediccions TXH�SUHGRPLQHQ�HQ�OD�KLVWRULRJUD¿D�

In 1354, the poorhouse or Almoina of the Cathedral of Barcelona, commonly known as the Pia Almoina, completed their purchase of the rights to the castle of Sitges, a small coastal town around forty kilometers south of Barcelona. Beginning that year, a series of documents written by the procurator of the castle and stored at the main house in Barcelona document extensive information about the seigniorial and agricultural practices of the land. The information drawn from these documents calls into question a number of fundamental beliefs about the structures of agrarian Europe. The general model of the crisis of food production and overpopulation in the fourteenth century relies on a relatively static agricultural output with little or no improvement in yields based on available technology. Generally, this involves an extensive view of land production and the necessity of extensive fallow or use of new non-marginal land in order to increase possible grain outputs. Additionally, crop yields throughout Europe are usually assumed to be near

the subsistence point, forcing peasants to deal with almost FHUWDLQ�LQVWDELOLW\�ZLWKRXW�VXI¿FLHQW�ODQG�UHVRXUFHV��

The Sitges records demonstrate that cultivators understood a number of methods for increasing their yields, most of which relied on an increased input of either capital or labor. Through increased manuring and FDUHIXO�¿HOG�WHQGLQJ��WKH�SURFXUDWRUV�RI�WKH�6LWJHV�FDVWOH�reported yields averaging more than 12:1 for barley and almost 10:1 for wheat, and sometimes in excess of 20:1 for both (see Appendix A). The documents also reveal some of the decision making processes of the property managers. Similar to the conclusions of David Stone’s work on the manor of Wisbech, the procurators responded to the best available market and weather information, using both extra labor and varying crop rotations to DOWHUQDWHO\� PD[LPL]H� WKH� RXWSXW� RI� WKHLU� ¿HOGV� DQG� WR�hedge against risk.1 While some of the methods might

1 David stone, Decision-making in medieval agriculture, Oxford, 2005.

67

Adam FrAnklin-lyonS : Grain yields and agricultural practice at the castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

66

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

often slipping dangerously close to not even receiving DV� PXFK� LQ� KDUYHVW� DV� ZDV� VRZQ�� SHUVLVWHQW� GLI¿FXOWLHV�with soil exhaustion, especially in the face of increasing population, and little ability on the part of cultivators to FXUE� WKHVH� GLI¿FXOWLHV�� 0DQ\� VFKRODUV� IURP� WKURXJKRXW�Europe have pegged the standard yield ratios as low as 4:1; despite the occasional report of higher yields, Georges Duby grimly stated, “They could hardly hope for more.”5 English husbandry manuals pegged yields at 8:1 for barley, 7:1 for rye, 5:1 for wheat, and 4:1 for oats. Again, Georges Duby describes these estimates as “very optimistic period”.6 Often historians describe these yields as remaining at their dismal rate for centuries, only rising during the industrial revolution.7 A recent survey of agrarian history in Catalonia itself by Antoni Furió laments the persistent stereotype of “the technological 5 Georges duby and Cynthia Postan (trans.), Rural economy and country life in the medieval west, Philadelphia, 1998, p. 101. Some areas like the Artois in France, described as having exceptional fertility against this backdrop of generally poor return, approached yields of 15:1. Georges Duby also notes the importance of Parisian consumption in driving production –we will return to this below.6 Georges duby, Rural economy and country life in the medieval west, op. cit., p. 100. For extensive data and further details on English agriculture, see: Bruce M.S. camPbell, Three centuries of English crop yields, 1211-1491 [WWW document, 2007] URL http://www.cropyields.ac.uk [accessed on 10/10/11]. Bruce Campbell tends to peg the average rates for these centuries at around 4:1 for all grain except barley, which only faired slightly better.7 Georges duby, Rural economy and country life in the medieval west, op. cit., p. 102-103. In his book on Paris, Guy Fourquin, despite his ¿QGLQJV�RI�UHODWLYHO\�KLJK�\LHOGV��QRWHV�WKDW�WKH�DJULFXOWXUDO�WHFKQLTXHV�of the fourteenth century represent the technological maximum available for the next few centuries: « Un homme de 1300 a les progrès derrière lui. Il n’y aura presque plus d’améliorations avant le XVIIIe siècle, et les techniques de 1300 allaient ainsi se maintenir des siècles durant ». Guy Fourquin, /HV� FDPSDJQHV� GH� OD� UpJLRQ� SDULVLHQQH� j� OD� ¿Q� GX�0R\HQ�Âge : du milieu du XIIIe au début du XVIe siècle, Paris, 1964, p. 117.

stagnation of medieval rural society” and “with grain yields so unbelievably low that it has been proposed that at times they did not even succeed in replacing the sown grain.”8 He notes that this stereotype persists in part due to a lack of solid local studies. However, even he draws on studies that place grain yields of 9:1 at the top of what was possible.9

Along with persistently low yields, the dominant model of agricultural production in the late middle ages describes the increased use of marginal land under constant pressure from an increasing population. The Population-Resources model assumes that “land will be expensive when it is scarce relative to labor and so too will the products of the land.”10 The rising population of the thirteenth century, therefore, forced increasing use of poor land as prices rose relative to both agricultural output and wages. The law of diminishing returns insured that even as labor became cheaper, increased human inputs for WKH�VRLO�FRXOG�QRW�FRPSHQVDWH�ZLWK�VXI¿FLHQWO\�LQFUHDVHG�output, or worse, could lead to soil exhaustion, further lowering future harvests.11 Hence, even if cultivators had the knowledge necessary to increase their harvests, they had their backs against the wall of increasing population; they would only be able escape when famine and epidemic removed a third or more of the European population.

8 L’estancament tecnològic de la societat rural medieval; and amb uns rendiments tan mesquins i tan irreals com els que de vegades s’han proposat, que no arribaven ni a duplicar el gra sembrat, Antoni Furió, « L’utillatge i les tècniques », in Emili Giralt i raVentós and Josep salracH (dirs.), Història agrària dels Països Catalans, vol. II La Edat Mitjana, Barcelona, 2004, p. 335.9 Antoni Furió, « L’utillatge i les tècniques », art. cit., p. 342-343.10 John HatcHer and Mark bailey, Modelling the Middle Ages, op. cit., p. 22.11 Ibid., op. cit., p. 23-25.

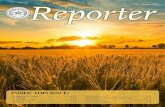

Map 1. A map of several of the major properties owned by the Barcelona Almoina in the region around Barcelona. the larger circles represent a greater level of yearly income from their holdings

(Basemap: World_Terrain_Base com-piled from sources: U.S. Geological Survey, Tele Atlas, AND, and ESRI. This map was created using ArcGIS® software by Esri. ArcGIS® and Arc-Map™ are the intellectual property of Esri and are used herein under license. Copyright © Esri. All rights reserved)

not have been available to all farmers, the motivation RI� WKH� SRRUKRXVH� PDQDJHUV� IRU� ¿QDQFLDO� JDLQ� OHG� WKHP�to adopt a number of methods that proved economically effective for an organization able to afford them. Because of the close proximity of the Barcelona market and the ability of the managers to ship or store grain to seek the EHVW� SULFH�� WKH� GHFLVLRQV� UHÀHFW� D� KLJKO\�PRQHWL]HG� DQG�mercantile attitude towards farming. Adoption of many RI� WKHVH�WHFKQLTXHV�VHHPHG�WR�UHO\�RQ�WKH�FRQÀXHQFH�RI�knowledge about the practices, the capacity to afford and implement them, and a general desire and ability to utilize increased yields.

The main administrative books from Sitges cover the years 1354 through to 1411. There are scattered other record books and documents that date from as early as the 1330’s, as well as a number of other books from after 1411. However, the most complete administrative books for the oversight of Sitges itself begin with the complete takeover of responsibility for the castle by the Barcelona poorhouse in 1354.2 The record books contain information similar to that found in the manorial accounts of England; the local books from Sitges are divided into WKUHH�VHFWLRQV��WKH�¿UVW�VXPPDUL]LQJ�DOO�RI�WKH�LQFRPH�WR�the castle, including rents, payments in kind, labor, and RWKHU�WD[�UHYHQXHV��7KLV�VHFWLRQ�RIWHQ�FRQWDLQV�WKH�VSHFL¿F�quantities of grain harvested from the castle demesnes ¿HOGV��WKRXJK�RFFDVLRQDOO\�WKH\�RQO\�UHFRUG�WRWDO�DPRXQWV�of grain collected from all sources. Additionally, this VHFWLRQ�QRWHV�WKH�¿QDO�XVH�RI�PXFK�RI�WKH�JUDLQ��ZKHWKHU�LW�is replanted, stored, or sold, in which case the price is also supplied. I have used the quantities set aside for planting combined with the harvest reported in the subsequent year to compile the seed yield ratios listed in the appendix. The second section, arranged chronologically over the ¿VFDO� \HDU� IURP�0D\� WKURXJK� WKH� IROORZLQJ�$SULO�� OLVWV�all payments made by the house and their dates. These include both the paid labor and the seigniorial obligations WKDW�SURYLGHG�WKH�DJULFXOWXUDO�ZRUN�LQ�ERWK�WKH�¿HOGV�DQG�the vineyards, as well as the food served to the workers for the main meal of the day. These records provide the discussion of the farming practices and decisions made by the castle procurators to achieve these yields. The ¿QDO�VHFWLRQ�RI�WKH�ERRNV�XVXDOO\�UHFRUGV�³H[WUDRUGLQDU\´�payments such as building repairs, sale or purchase of property, and the cost of trips to neighboring towns or to Barcelona. Occasionally, particularly when the local administrative books of the castle are missing, information VXFK�DV� VDOH�SULFH�GDWD�FDQ�EH�¿OOHG� LQ�ZLWK� WKH�JHQHUDO�management records of the Majordomia of the Cathedral Almoina, kept and recorded in Barcelona. This format

2 Other than the vicissitudes of document survival, it is unclear why they seem to stop so abruptly in 1411. The scattered remains cover the following century, but allow very little expansion of the data presented in this essay. The small books rarely contain page numbers and as such will be referred to by their administrative year (beginning in May and continuing through April of the following year). The document collection is contained in the Arxiu Capitular de Barcelona [Hereafter ACB]; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsas 1-6.

DSSHDUV�WR�EH�FRPPRQޤ�VHYHUDO�RWKHU�SURSHUWLHV�XQGHU�WKH�Almoina’s ownership recorded similar books. However, almost none have survived –in total less than a dozen such books from the other large properties in Mogoda, Vilafranca del Penedés, or the Torre Balldovina (see Map 1).3 Other poorhouses around the Mediterranean might have preserved similar records, but none are currently known that provide agricultural information like those of Sitges.

While the documents provide greater detail about agricultural practice than almost any other sources in the Crown of Aragon, there are still limitations, especially when compared to the well known richness of the English PDQRULDO� DFFRXQWV�� %HFDXVH� RI� WKH� VSHFL¿F� QDWXUH� RI�the documents, many important questions must remain without answer. At the castle of Sitges, the exact pieces of land worked are rarely described, obscuring the exact nature or scale of their labor and some of their practices RI�FURS�URWDWLRQV�DQG�IDOORZV��7KLV�ODFN�RI�VSHFL¿HG�ODQG�area also renders it impossible to know if their agricultural techniques also increased yield per acre as greatly as they seem to have increased the yield ratio.4 Further, as discussed below, one of the main features of the neo-Malthusian explanation of the late medieval economy is the falling yields per acre as the land comes under the plow more and more intensively; eventually the increasing population density runs up against the law of diminishing returns and greater labor inputs prove unable to increase yields. Without knowing how many acres the castle had at their disposal, it cannot be tested whether or not Sitges suffered the same fate, despite their apparently constant intensive use of the land. Even with these shortcomings, the records from the Barcelona poorhouses provide a new and startling view of agricultural practice in the late fourteenth century.

gRain yields

The prevailing understanding of agricultural

production in the late-medieval period generally paints a fairly bleak picture. What John Hatcher and Mark Bailey refer to as the “Population and Resources” model, often also called the “neo-Malthusian” model, assumes that population increases over the thirteenth century constituted a driving force in the rural economy, leading slowly towards the inevitable impoverishment of the peasantry. The model entails persistently low crop yields, 3 ACB, V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes.4 Yield ratio represents amount of seed harvested compared to seed sown, regardless of land area. Unfortunately, this is a serious lack. As noted above, the questions about subsistence and overpopulation rely on being able to equate land area, soil quality, and caloric output. If we do not know the relative area, we cannot know how much land would be necessary to feed a given number of people. Some of the work done on Medieval England has focused on average size of peasant landholdings and what size farm represents a minimum of subsistence. Without yield per acre, such calculations are impossible. See: John HatcHer and Mark bailet, Modelling the Middle Ages: the history and theory of England’s economic development, Oxford, 2009, p. 43-49.

69

Adam FrAnklin-lyonS : Grain yields and agricultural practice at the castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

68

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

agRicultuRal MetHods

Agriculturalists on the Mediterranean coast worked with the thin soils and dry summers through a variety of inputs and techniques. Dry summers encouraged an almost total reliance on winter cereals - there is no evidence of any summer cereal production in Sitges.21 The thin soils made water and manure the two most important inputs for improving yield, a scenario that persisted till the twentieth century.22 Ability to deal with these factors, however, varied widely with the resources and capacity of the landowners. Because of the motivation and capital resources of the overseers on poorhouse lands, their choices represent perhaps the best level of technology available in the fourteenth century.

Amongst the available agricultural techniques, V\VWHPDWLF�DQG�HI¿FLHQW�XVH�RI�ODERU�ZDV�WKH�PRVW�LPSRUWDQW�single category. Work on several farms, both in Sitges and in other agricultural land around Barcelona, involved a combination of paid day labor, full time retainers housed, paid, and fed at the institutions year round (referred to as macips and servents), and labor-rent obligations in the form of labor obligations both for individuals (called tragins) of animals (called joves).23 Often individuals

21 Other studies of Catalan agriculture note the importance of both winter and summer cereals. However, in this set of documents, winter cereals are not simply more common - they dominate. Virtually all collections of agricultural goods recorded by the Almoina come in during the late spring or early summer, between May and July. This includes rents from Sitges, Mogoda, Santa Coloma, Sant Feliu de Llobregat, and Gravalosa, among others. See: María ocaña i subirana, El món agrari i els cicles agrícoles a la Catalunya vella (s. IX-XIII), Barcelona, 1998, p. 57-62.22James simPson, Spanish agriculture: the long siesta, 1765-1965, Cambridge, 1995, p. 126-147.23 The term tragí can sometime imply transport or movement, but on the Sitges land, these laborers performed a variety of different labors and the term only seems to imply a general obligation of manual work.

worked for a single day’s pay, which hovered between one and a half and two solidos per day; unsurprisingly, women and youths (fadrins) generally received payment at the lowest end of the scale, sometimes as low as one solido per day.24 People hired with animals –virtually always either mules or oxen– received three solidos for transportation services and four for plowing and other agricultural work. While working, laborers also received their food for the day. Food usually meant only the main meal of the day, EXW�LQYROYHG�EUHDG�DQG�PHDW��RU�¿VK�RQ�IDVW�GD\V��DORQJ�with some form of companatge, including vegetables, FKHHVH��HJJV��¿JV��RU�RWKHU�IRRGVWXIIV��7KRVH�ZRUNHUV�ZKR�performed particularly heavy work such as plowing and harvesting would also receive liver for breakfast.

6WUDWHJLF�XVH�RI�PDUNHW�ODERU�DOORZHG�IRU�ÀH[LEOH�ZRUN�schedules and decreased bottlenecks in production. The labor-intensive periods of the year –particularly planting and harvesting– might involve as many as ten men and multiple draft animals for what was likely a small plot of land.25 On another, much larger, property, the castle of Mogoda, the overseers might hire more than thirty people at a time.26 The laborers could both harvest larger than usual harvests in good years, but also came in to repair the ZDOOV�RI�WKH�¿HOG��VSUHDG�DQG�SORZ�LQ�PDQXUH��SHUIRUPLQJ�extra plowings when necessary, weed around the plants LQ�ZHW�\HDUV��RU�FDUU\�ZDWHU�RXW�LQWR�WKH�¿HOG�LQ�GU\�\HDUV��This doubtless allowed the managers of the land to keep soil fertility high and respond to the vicissitudes in the 24 6XUSULVLQJO\��KRZHYHU��WKHVH�ZDJHV�FKDQJHG�OLWWOH�RYHU�WKH�¿IW\�\HDUV�of the records. Day laborers still received only two solidos in 1406 and seemed to have peaked in their wages in 1408 at two solidos two diners.25 Pere benito i monclús, « Del castillo al mercado y al silo... », art. cit., p. 22-23.26 During the harvest of 1377, not an especially remarkable year, the overseer in Mogoda hired thirty-two people for the week of the harvest; ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; H. Casa de Mogoda, 1382-83, fol. 37r°-39v°.

�

Extra labor could provide no answer, nor could improved technology go far in helping grain yields –in this model, the delicate balance between land and labor proved too strong for such responses.

In stark contrast to this picture, the yields recorded at the castle of Sitges for the second half of the fourteenth century portray a strikingly different reality. Over the FRXUVH� RI� ¿IW\� \HDUV�� EDUOH\� \LHOGV� DYHUDJHG� RYHU� �����DQG�ZKHDW� DYHUDJHG� MXVW� EHORZ������±ERWK� VLJQL¿FDQWO\�higher than the averages given for other parts of Europe (See Graphic 1). Barley rarely produced less than a ten fold yield; for virtually all of the years that do, the FLW\� UHFRUGV�RI�%DUFHORQD� UHYHDO�GLI¿FXOWLHV� LQ� WKH�JUDLQ�VXSSO\��PHDQLQJ�WKH�GLI¿FXOW�KDUYHVW�ZDV�SUREDEO\�PRUH�widespread than only Sitges.12 The lowest recorded yields of any harvest –a mere 5:1 in 1376– correspond to the closing years of perhaps the worst famine of the century in the Mediterranean.13

When the harvest proved below these averages, some procurators noted their lower quality. In 1397, the barley only yielded 8:1, and the record describes the grain as “weedy.”14 The records of another institution, the Hospital dels Malalts in Barcelona, though exceptionally sparse, reveal a few additional data points. Beginning in 1380, the hospital lands yielded just 7:1 in barley on their SHUVRQDO�¿HOG�LQ�������D�\HDU�WKDW�PDUNV�WKH�EHJLQQLQJ�RI�several rainy seasons, increased prices, and new imports to Barcelona from Sicily.15 The following year, as rains continued, the hospital harvested only 1.8:1. After that \HDU��VSHFL¿F�QXPEHUV�VWRS�DV�PRVW�RI�WKH�JUDLQ�JHWV�HDWHQ�in house rather than sold. What little grain does grow is of poor quality.16 Despite these few bad years, the general trend is quite high. The highest of these numbers are only matched by some references from Sicily –a region famous for supplying large areas of the Mediterranean with grain, and still the island that Barcelona turned to in times of

12 For 1397 and 1403, see: Juanjo càceres neVot, La participació del consell municipal en l’aprovisionament cerealer de la ciutat de Barcelona (1301-1430), Dissertation, Universitat de Barcelona, 2002, p. 161-167 and 168-172. For general prices of commodities in Barcelona, see: Adam Franklin-lyons, Famine – preparation and response in Catalonia after the Black Death, Dissertation, Yale University, 2009, p. 67-86.13 Adam Franklin-lyons, Famine – preparation and response in Catalonia after the Black Death, op. cit., p. 111-130.14 Ordi erbos. ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 5; 1397 fol. 1v°.15 This data point is not entirely certain. One note in the records mentions 2.5 quarteres sown, while another notes 2 quarteres purchased for sowing and 4 quarters (each quarter is 1/12th of a quartera) of that were fed to the chickens. In either case, 15 quarteres are harvested the following year. Assuming they used half a quartera to supplement the purchased two and then fed some to the chickens from that amount, this means around 2.15 quarteres were sown to 15 harvested - around 7:1. ACB; Capítol de la Catedral; IV. Caritat o mensa capitular; 13. Hospitals; Hospital dels Malalts, 1379, fol. 82r°.16 Lo qual forment era molt dolent. ACB; Capítol de la Catedral; IV. Caritat o mensa capitular; 13. Hospitals; Hospital dels Malalts, 1383, fol. 91v°.

shortage.17 By any measure, these are extremely good yields.18

Why are these data so different from other records of grain harvests in Europe? There is no reason to think that, like the area north of Paris, the land in Sitges is more fertile than other areas. Like much of the Catalan coastline, the castle sits against a steep backdrop of hills covered with thin, lightly watered soil –nothing like the rich alluvial soils of northern France. The Barcelona Almoina documents of the castle record a great deal about WKH�SUDFWLFHV�DQG�FKRLFHV�PDGH�WKDW�ZRXOG�KDYH�LQÀXHQFHG�their yields and productivity. The overseer of the castle, and presumably many of the laborers, understood a great deal about the health of the soil, the productive potential of different grains, and how to maximize their output, and put high amounts of both labor and capital investment into their lands. Their interest in these practices gained priority under the direction of a class of clerics with economic savvy and a strong motivation to maximize output.19 The record keeper, always interested in cost and production, but never in explanatory prose, does not often make explicit the reasoning behind their agricultural choices. However, some of these reasons can be inferred from known weather patterns and widespread harvest trends, but some must remain speculations. Finally, these often labor intensive practices occur in the second half of the fourteenth century during a time of crashing population levels. While the population resource model predicts a preference for extensive practices in a land rich, labor poor environment, the procurators of Sitges began their labor intensive practices several years after the appearance of the Black Death and continued throughout the second half of the century; they believed these practices increased output enough to be worthwhile regardless of the changing price of land and labor. The administrative books of the castle of Sitges housed at the Capitular Archive of the Cathedral of Barcelona provide a detailed view of these agricultural practices, the knowledge available to the overseers of the property, and the choices they made during the second half of the fourteenth century. Scant, but corroborating, evidence from other poorhouses in Catalonia also hint that the practices were probably widespread.20

17 As will be discussed below, Sicily also maintained a long-standing preference for the scratch plow and oxen for traction. See: Stephan ePstein, An island for itself: economic development and social change in late medieval Sicily, Cambridge, 2003, p.163.18 These yield numbers do, however, accord well with many of the comments from Roman writers which tended to assume a normal harvest of somewhere between 8:1 and 10:1 and 15:1 as an exceptional harvest; See Paul erdkamP, The grain market in the Roman Empire: a social, political and economic study, Cambridge, 2005, p. 34-41.19 Pere benito i monclús, « Del castillo al mercado y al silo. La gestión de la renta cerealista de la Almoina de Barcelona en la castellanía de Sitges (1354-1366) », Historia Agraria, vol. LI, 2010, p. 13-18. 20 These records include both other local management records of the Almoina, such as those from the castle of Mogoda, as well as general management records from other poor houses such as the Hospital d’en Colom and the Hospital d’en Vilar. All of these records are also housed at the ACB, either within the Pia Almoina archive or under: ACB; Capítol de la Catedral; IV. Caritat o mensa capitular; 13. Hospitals.

Fig 1. Crop yields of Barley, Wheat and Favas at Sitges (Seed Ratio)

Qua

rtere

s of G

rain

Har

vest

ed p

er Q

uarte

ra S

own

Barley YieldsWheat YieldFavas Yield

71

Adam FrAnklin-lyonS : Grain yields and agricultural practice at the castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

70

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

handful of years, the overseer mentions purchasing extra manure in what appears to be a general market. Other poorhouse lands in Barcelona also mention the purchasing of manure, apparently more frequently than in Sitges. Purchases especially spiked shortly after bad years, with several hospitals recording extra manure use in the late 1370’s after the major famine of 1374-1376. In 1375, the Hospital d’en Colom purchased manure directly from the UR\DO�SDODFH�IRU�WKHLU�¿HOGV�DW�D�SULFH�RI�RQO\�HLJKW�diners per somada.38 By the end of the season they had purchased more than two hundred somades, probably more than WZHOYH�WRQV��7KH�EHQH¿WV�RI�PDQXUH�ZHUH�GRXEWOHVV�ZHOO�understood, but this did not necessarily translate into this sort of commercialized and highly systematic use in other areas, as these sources seem to suggest for Catalonia.39 The presence of the market also implies that a larger city like Barcelona might have had an active trade in reselling the manure produced by the myriad animals in the city –transport animals coming and going, the royal stables, animals brought to the market for eventual slaughter– all ZRXOG�KDYH�SURGXFHG�VLJQL¿FDQW�TXDQWLWLHV�RI�PDQXUH�WKDW�the city would often attempt to regulate. Given the casual mention of manure purchases in the poorhouse records, it is somewhat surprising that the city and royal records never mention or regulate its sale.40

Another important aspect of the agriculture at Sitges is their use of changing crop rotations.41 Similar to some

Plecs de comptes; capsa 1, 1359, fol. 26r°.38 The somada is an old measurement from the Cerdanya originally used for wine and meant to be as much as one beast could carry –it is estimated at 125 kilos; see: Thomas bisson, Fiscal accounts of Catalonia under the early count-kings (1151-1213), T. I, Berkeley, 1984, p. 303-305. During the fourteenth century in Barcelona, wine was customarily measured in FD¿oRV, càrregues, botes, somades and quarters. One bota measured forty somades and each somada thirteen quarters. See: Josep trencHs, « El vi a la taula reial: documents per al seu estudi a l’època del rei cerimoniós », in Vinyes i vins: mil anys d’història. Actes i comunicacions del III Col·loqui d’Història Agrària sobre mil anys de producció, comerç i consum de vins i begudes alcohòliques als Països Catalans. Febrer del 1990, T. I, Barcelona, ������S�������$V�PLJKW�EH�H[SHFWHG�� WKLV� LV� VLJQL¿FDQWO\�FKHDSHU� WKDQ�the cost of food sold by the somada –notably wine, which often sold for more than ten solidos per somada; it is also around a quarter of the cost RI�¿UHZRRG��ZKLFK�ZDV�DOVR�VROG�LQ�WKH�somada measure; ACB; Capítol de la Catedral; IV. Caritat o mensa capitular; 13. Hospitals; Hospital d’en Colom, 1375, 43v°.39 As a side note, in the Muslim south, many of the agronomy manuals produced during the later medieval period considered the health of the soil and the use of proper manure as the single most important aspect of good farming. Some of this knowledge came originally from Roman writers such as Columella or Palladius, whose manual was translated into Catalan in the fourteenth century. However, it is impossible to know if any of the knowledge in these texts was available to even the educated overseers in the hospitals of Barcelona; see: Lois olson and Helen eddy, « Ibn-Al-Awam – A soil scientist of moorish Spain », Geographical Review, vol. XXXIII, 1943, p. 100-109; Expiración García sáncHez, « Agriculture in Muslim Spain », in Salma k. Jayyusi (dir.), The legacy of Muslim Spain, Leiden, 1992, p. 987-999; and Thomas caPuano, « Una nueva versión catalana del Opus agriculturae de Palladius », Romance Philology, vol. LIX, 2006, p. 231-239.40 More work could doubtless be done on the marketing and movement of manure –the poorhouse records prove only its existence and use, but provide very little other information.41 As a side note, the records also note the planting and harvesting of various other plants in the hortes of the hospitals, although never with

of the patterns noted by David Stone in Ely, the managers responded frequently to changes in the economy and in the climate.42 The famines of 1374-1376 and 1381-������HVSHFLDOO\��LQÀXHQFHG�IDUPLQJ�SUDFWLFHV�LQ�ERWK�WKH�VKRUW�DQG�ORQJ�WHUP��$IWHU�WKH�¿UVW�EDG�\HDU��LQ�������WKH�workers at Sitges planted an indiscriminant mix of barley and wheat –something not done previously. Presumably, they were attempting to harvest any amount possible after the miserable return of 1374. Then, in 1376, they return to planting wheat, but again reap a poor harvest. After attempting barley and broad beans in 1377, they sow wheat again in 1378, but with little better results.43 These two years would have put Sitges at a strong disadvantage since market prices in Barcelona had begun to fall already in 1375 as wheat arrived from Sicily and Flanders. In this situation, their response makes sense. After these two years, overall planting of wheat drops considerably. In the twenty years prior to the famine, barley is planted ten times, wheat six, with a couple of unknown years and a couple years of only broad beans. After the attempts at wheat planting in 1376 and 1378, wheat only appears in two record years out of the next twenty, with barley appearing fourteen times (although four record years DUH� PLVVLQJ��� 7KH� GLI¿FXOWLHV� ZLWK� ZKHDW� SUHVVXUHG� WKH�procurators to prefer the safer, though less lucrative, EDUOH\�ZHOO�DIWHU�WKH�LQLWLDO�KDUYHVW�GLI¿FXOWLHV�KDG�HQGHG��'XULQJ� WKH� GLI¿FXOWLHV� LQ� WKH� ����¶V�� WKH� PDQDJHUV� DW�the Hospital dels Malalts, also responded quickly. After WKH� GLVPDO� KDUYHVW� RI� ����� í������� WKH� ORZHVW� ,� IRXQG�recorded for barley in any source– only broad beans are planted in 1382, presumably with the goal of returning some fertility to the soil. Then, in 1383, the hospital buys 1.5 quarteres of high quality wheat for planting, relying on the new grain to produce a superior harvest. Again, the rains thwarted their efforts and the little “poor” wheat harvested is all served in the hospital.44 In 1384, again, they return to a crop of all broad beans and heavy manuring. While the severity of those years overwhelmed the usual defenses, the general response of the hospitals to climatic GLI¿FXOWLHV� VWLOO� GHPRQVWUDWHV� D� FOHDU� UHVSRQVH�� UHWUHDW�from production for a year, sow only broad beans, and maintain good fertility for when better weather returns.

Finally, it is worth noting the consistent choice to use only a scratch plow, rather than the heavier moldboard plow often found in northern Europe by the fourteenth century. The references to repeated plowings, sometimes weeks apart, particularly when manure is being spread,

quantities or amount of land. The records mention garlic, cabbage, chick peas, and even peach trees and saffron. This surely played into rotation choices, though the exact nature of the space cannot be know.42 David stone, Decision-making in medieval agriculture, op. cit., p. 51-58.43 It is actually unclear why wheat harvests remained low so long. By most accounts the famine ended in 1376 and the harvest of 1377 returned more or less to normal. Possibly Sitges was worse hit than other areas, though this is only speculation. See: Adam Franklin-lyons, Famine – preparation and response in Catalonia after the Black Death, op. cit., p. 146-148.44 ACB; Capítol de la Catedral; IV. Caritat o mensa capitular; 13. Hospitals; Hospital dels Malalts, 1382, fol. 132v° and 1383, fol. 91v°.

weather in a way that individual agriculturalists would not be able to do.

7KH� ODERU� UHFRUGV� DOVR� SURYLGH� FOXHV� WR� WKH� VSHFL¿F�practices of planting and harvesting. As noted, all grains mentioned were winter crops, sown usually sometime in November, though occasionally in very early December if rain or other bad weather delayed planting. Prior to SODQWLQJ�� WKH� ¿HOGV� ZHUH� FOHDUHG� RI� ZHHGV� �LQFOXGLQJ�redortes, gram, or erba), plowed, often more than once, and the remaining clods would be broken up (esterroçar) with mallets or spades (called càvec). For the seeds themselves, WKH�SURFXUDWRU�ZRXOG�RIWHQ�FKRRVH� WKH�¿QHVW�JUDLQ� IURP�the previous years collection to set aside, but if not high TXDOLW\� JUDLQ� ZHUH� DYDLODEOH�� WKH\� ZRXOG� VSHFL¿FDOO\�SXUFKDVH�¿QHU�JUDLQ�WKDQ�WKH\�XVXDOO\�DWH�WR�LQVXUH�D�KLJK�quality harvest.27 Finally, it appears that the seeds were sown and then covered with a new layer of well-manured soil.28 While they might have still used a broadcast method, it does appear that the planters paid closer attention to how the seeds came to rest for germination than is generally assumed in medieval agriculture. Particularly the practice of leveling or covering the seeds, and even of watering WKH�¿HOG�LI�WKH�JURXQG�ZDV�QRW�VXI¿FLHQWO\�ZHW��FRXOG�KDYH�greatly improved germination rates, thereby improving FRQVLGHUDEO\�WKH�¿QDO�\LHOG�

Throughout the winter, the overseer kept close track of the growing plants. Hired workers would alternately ZDWHU� WKH� ¿HOGV� IURP� WKH� ZHOOV� DURXQG� WKH� FDVWOH� RU�sometimes pull up weeds if too many threatened to choke off the young grain.29 In the dry Mediterranean, watering WKH�¿HOGV�DSSHDUV�UHODWLYHO\�FRPPRQ��VHH�EHORZ�IRU�PRUH�on irrigation), but weeds were often the worst threat if the winter proved rainier than usual. In 1362, in addition to a man with a two-mule team brought to sow the broad beans, the laborers included “one other man and two women who planted the broad beans (faves) and pulled weeds because there were so many.”30 Normally, only one man with a team of two mules working as a labor obligation (jova) came to sow the broad beans –the other three workers are explicitly described as extra. Again, in 1400, three teams of mules came to plow up the weeds; they needed two attempts at it because, “on account of the rain, it was all weeds!”.31 Similarly, at the Hospital dels Malalts of Barcelona, during the rainy famine of 27 ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 2, 1364, fol. 30r° and capsa 6, 1408-1409.28 Multiple records mention the spreading of manure (escampar fems), generally prior to sowing. One note from 1406 makes clear the order by listing all the work in a single payment: sembre l’orta costaren ii homens per ascampar fems e astorrosar, cavar racons e aplanar per cobrir la lavor. ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 6, 1406.29 ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 4, 1377.30 un altre hom i dos fembres qui sembraren faves i secudien erba car molta hi avia. ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 2; 1362, fol. 22v°.31 Item, gire II vagades l·ort que per les plugues tot era erba. ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 5, 1400.

����������� H[WUD� ZRUNHUV� DUH� EURXJKW� WR� WKH� ¿HOGV� LQ�1RYHPEHU� WR�HVVHQWLDOO\�UHSODQW�DQG�UH�PDQXUH� WKH�¿HOG�due to the heavy rains.32 During the winter and spring, ODERUHUV�ZRXOG�DOVR�URXWLQHO\�KRH�WKH�¿HOGV�WR�KHOS�NHHS�down the weeds. The terms used for this labor differed between grain, eixarcolar, and broad beans, entrecavar.33 Entrecavar, literally digging between, probably implies the relative ease of hoeing between the larger stems of the fava plant as opposed to weeding around the closer and more fragile grain stems.34 In both cases, it is clear evidence of the sort of careful tending that doubtlessly LPSURYHG�WKH�UHWXUQV�RQ�WKHVH�KRVSLWDO�RZQHG�¿HOGV�

After the human input, the economic resources of the Almoina also allowed the farm to invest more heavily in capital materials. Immediately after the complete purchase of the land and rights in 1354, the hired managers set about improving the agricultural space. Some of the hired laborers removed larger stones from the land, sometimes evaluating them for their workability for construction purposes. Wells supplied water both for the castles uses as well as for irrigation. In one note from 1356, they hire men to come and repair what appears to be a noria-pot water wheel, called a cenia (or sènia) in the sources. The device seems to have collapsed and the drive wheel needs to be reset or replaced.35 Certainly such irrigation practices were not uncommon in the Crown of Aragon, particularly in Valencia, but the use of such technology DOZD\V� UHTXLUHG� VXI¿FLHQW� LQVWLWXWLRQDO�EDFNLQJ� IRU� WKHLU�integrated operation, something the Almoina was well able to provide.36

Perhaps most strikingly, larger monetary resources also gave the Barcelona hospital institutions the ability to invest in soil fertility. Generally manure came from the draft animals that worked the land as well as from those collected in the stables owned by the castle.37 In a 32 ACB; Capítol de la Catedral; IV. Caritat o mensa capitular; 13. Hospitals; Hospital dels Malalts, 1382, fol. 132v°.33 The documents include the term eixarcolar –usually spelled either exercolar or axercolar– for both barley and wheat; it appears frequently but for a few examples of all the terms see: ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 1, 1357, fol. 28v°; 1358, fol. 22r°; and 1359, fol. 15v°.34 7KH� WHUPV� DOVR� SUREDEO\� LOOXPLQDWH� VRPHWKLQJ� VSHFL¿F� DERXW� WKHLU�practices of farming which would require more research into the terms in other contexts to parse out. One small tantalizing option is that since they practiced routine irrigation, they have the crops –again, especially EURDG�EHDQV±�ODLG�RXW�LQ�URZ�SDWWHUQV�WKDW�DOORZ�IRU�DQ�HDV\�ÀRZ�RI�ZDWHU�through the crops and then would also assist in hoeing down the lines to keep out weeds; see: Lucie bolens, « L’eau et l’irrigation d’après les traités d’agronomie andalous au Moyen Âge (XIe-XIIe siècles) », Options Méditerranéennes, vol. XVI, 1972, p. 72.35 que descubriren la cenia de la orta que cayha e s’enderrecava e per oR�TXH�OHV�WHXOHV�QRÂV�SHUGHVVHQ�QHÂV�WUHQFDVVHQ�¿X�OD�GHVFXEULU��H�FRVWj�peyx e carn per tot dia. ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4. Plecs de comptes; capsa 1, 1356, fol. 13r°.36 Thomas Glick, « Noria pots in Spain », Technology and Culture, vol. XVIII, 1977, p. 644-650.37 When the animal stalls were cleaned out, workers carried the manure RXW� WR� WKH� ¿HOGV� WR� EH� VSUHDG� DURXQG�� 6HH� HVSHFLDOO\�� ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; C. Sitges; 4.

73

Adam FrAnklin-lyonS : Grain yields and agricultural practice at the castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

72

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

FKXUFK�RIÀFLDOV�VXFK�DV�WKH�FDQRQV�DQG�majordoms�RI�WKH�Almoina�KDG�DFFHVV�WR�WKHVH�PDQXDOV�DQG�DFWLYHO\�GLUHFWHG�WKH�ZRUN�RI�SHDVDQWV�RQ� WKHLU�SDWULPRQLDO�KROGLQJV�� WKLV�ZRXOG�SURYLGH�D�FOHDU�DYHQXH�RI�GLIIXVLRQ�IRU�WKLV�DQFLHQW�VRXUFH�RI�NQRZOHGJH��,W�ZRXOG�EH�D�FRPSHOOLQJ�WRSLF�RI�IXWXUH� VWXG\� WR� LQYHVWLJDWH� ZKHWKHU� RU� QRW� WKH� VSHFLÀF�DFWLYLWLHV�UHFRUGHG�RQ�WKH�Almoina�ODQGV�KDYH�DQWHFHGHQWV�LQ� ZULWHUV� OLNH� 3DOODGLXV� DQG� ZKHWKHU� RU� QRW� WKLV� FRXOG�UHSUHVHQW�WKH�VSUHDG�RI�VXFK�NQRZOHGJH�RXWVLGH�WKH�XUEDQ�FHQWHUV�WKDW�WUDQVODWHG�WKH�PDQXDOV�WKHPVHOYHV�

Even if day laborers and small cultivators had access to these levels of information, their ability to make use of it would have varied widely. Many of these techniques UHOLHG� KHDYLO\� RQ� DYDLODEOH� FDSLWDO� DQG� D� ÀH[LEOH� ODERU�market. Plowings and harvests mentioned in the Mogoda records employed dozens of people per day. The Barcelona Almoina, an institution that hired literally hundreds of workers throughout its patrimonial holdings, could certainly afford the occasional spike in labor costs, particularly if it meant a larger harvest. For individual holders, this would be a different question. One of the tenants of the Population-Resources model is the law of diminishing returns. This principle states that while two ZRUNHUV�PLJKW�FRPH�FORVH�WR�GRXEOLQJ�RXWSXW�RQ�D�¿[HG�area of land, at some point the marginal return decreases, RIWHQ� TXLFNO\�� ,I� WZR� SHRSOH� PLJKW� GRXEOH� RXWSXW�� ¿YH�people might only triple output. However, one of the major reasons for this fact in medieval agriculture has to do with labor bottlenecks. If plowing requires a dozen men and several animals, this could be the only time in the agricultural year that calls for such an input. Intense bad weather could ruin a crop without immediate and intensive labor responses (such as the weeding mentioned above). Other points of labor might be performed by only two or three workers. Given this fact about labor intensive agriculture, only the frequent use of wage labor would allow a cultivator to escape both the law of diminishing

returns as well as the normal labor bottlenecks of the agricultural year (normally plowing and harvesting –something supported by the numbers of workers mentioned in the sources). Any form of tenancy where the cultivator owns the land, from free peasants to forms RI� VHUIGRP�� LGHQWL¿HV� ODERU� ZLWK� ODQG� DQG� QHFHVVDULO\�restricts the possible labor inputs available. Individual peasants with greater wealth might be able to hire enough labor, but generally this point argues in favor of the capacity of institutions to generate consistently higher cereal yields. The almost fully monetized holdings of the Barcelona Almoina, using frequent day laborers, could well accomplish all of this, avoiding such bottlenecks in production and responding more effectively to the vicissitudes of weather.

However, even given capacity and knowledge, the procurators had to make the decision –and in this case, choose these often-expensive inputs during a period of declining population and rising labor costs. Bruce Campbell recently wrote of the agricultural situation in late-medieval England that, “Typically, it was the nature and relative strength of commercial incentives which determined production strategies and investment levels.”50 In describing the incentives present in late medieval England, Campbell faults the lack of clarity in the market. The coexistence of customary and economic or contractual arrangements for land ownership or rental blunted any possible increase in output based on economic incentive because they disguised the true cost RI�ODQG�UHQWDO�DQG�PDGH�LW�DSSHDU�PRUH�SUR¿WDEOH�IRU�ERWK�peasant and lord to employ methods designed for a short-term and land rich world.51 Practices such as the intensive use of manure and high labor inputs assume the opposite –planning for harvests over a longer term and in a space

50 Bruce M. S. Campbell, « The agrarian problem in the early fourteenth century », Past and Present, vol. CLXXXVIII, 2005, p. 8.51 Ibid., p. 9-10.

Fig. 2. An areal view of Sitges. At the center is the modern ajuntament, built between 1887 and 1889 on the foundation of the old castle

indicates the probable use of a lighter plow, often requiring cross plowing. Similarly, the breaking up of clods with spades or even a subsequent plowing mentioned above indicates an incomplete tilling of the soil more likely from the lighter plow. Finally, low numbers of oxen ZRUNLQJ�WKH�¿HOGV��RIWHQ�RQO\�WZR��VXJJHVWV�WKH�DEVHQFH�of the heavy moldboard plow, which required as many as four for a single plow. This was probably a preference because repeated plowings with a moldboard plow would have excessively disturbed the soil. Other scholars have suggested that the moldboard plow was best suited for heavy and deep soils such as those found in northern river YDOOH\V�íWKH�/RLUH��WKH�7KDPHV��WKH�5KLQH�45 In contrast, the scratch plow would allow for less erosion and loss of topsoil on the Catalan coastline, despite the necessity of greater labor input.46 The Sitges territory appears to KDYH�EHHQ�ODQG�SRRU��EXW�DEOH�WR�GUDZ�RQ�VLJQL¿FDQW�ODERU��which seems to bear out the preference for a scratch plow as a sensible choice.

All of these aspects of the grain harvests on hospital lands –from the high labor input, to the use of irrigation and the resources of a manure market– demonstrate an integrated and resourceful agricultural system. It is unlikely that any one of these elements made the difference between the high yields recorded at Sitges and the relatively low averages found in other studies. However, the combination of each element allowed for greater responsiveness against the vicissitudes of the weather or diseases, increasing yields in both good years and bad years. The agriculture of the fourteenth century was an incremental science, and any small gain provided a broader reduction of risk. The managers of these properties certainly assumed that many of the inputs listed above were both effective and worth the cost.

knowledge, Motivation, and caPacity

When discussing the grain harvests and the question of technological adoption and knowledge, we may usefully ask three guiding questions that will determine the technology’s eventual use: First, does the given cultivator actually possess the skills or knowledge necessary to increase their harvest yields? Second, does the cultivator desire higher yields? Is there any reason for that particular person to feel that this would be a positive outcome? Finally, even in possession of these skills and desires, do they have the infrastructure, capital, or necessary resources to actually implement their knowledge? Of these three aspects, knowledge has the major tendency to increase over time. Techniques learned widely are relatively unlikely to be forgotten.47 Capacity is the most

45 Georges comet, « Agrarian Technology in Northern France in the Middle Ages », in Grenville astill and John lanGdon (dirs.), Medieval Farming and Technology: The Impact of Agricultural Change in Northwest Europe, Leiden, 1997, p. 21-24 and p. 256.46 Such practices might have been different in the larger river basins such as along the Ebro or around Valencia.47 John HatcHer and Mark bailey, Modelling the Middle Ages, op. cit., p. 126-127.

XQSUHGLFWDEOH�RI�WKH�YDULDEOHV��$�JLYHQ�IDUPHU�PLJKW�¿QG�the ability, time, or money to implement technological changes in one year but not in a subsequent year. Material resources, even of larger institutions, can change almost from season to season. Motivations can also vary year to year, but above all are often determined by larger social and natural forces. Areas that became “most active in adopting these more intensive and progressive farming methods were those with natural environmental advantages, good market access, and few institutional constraints in the form of servile tenures and communal property rights.”48 At Sitges, all of these factors lent themselves strongly to the adoption of the most intensive farming practices.

Of the three determinants, knowledge is in some ways WKH�PRVW� VWUDLJKWIRUZDUG�� ,W� FDQ� EH� GLI¿FXOW� WR� NQRZ� LI�certain cultivators are aware of techniques that they are not adopting, but, as noted above, knowledge generally tends to increase. Practices from manuring to tending of WKH� ¿HOGV� DSSHDU� LQ� RWKHU� KRVSLWDO� WHUULWRULHV� LQGLFDWLQJ�that the knowledge was both well known and widespread. Hospital land represents only a minority of lands in Catalonia. However, their holdings extended outward in all directions from Barcelona and it seems unlikely that many of their tenants and procurators would not have been aware of the possibilities detailed in the Sitges records. Additionally, many of the techniques listed above are not radical technological changes –use of manure, pulling of weeds, and watering and irrigation are all fairly obvious and frequently documented techniques in medieval agriculture. However, their combination clearly proved effective. As with the crop rotations discussed above, what is notable is less the information at their disposal and more how the procurators chose to act on the information available to them.

One tempting possibility about the source of knowledge is that the Sitges example demonstrates a possible avenue for the diffusion of classical and Arabic agronomic techniques. As discussed in this volume by /OXtV�&LIXHQWHV��WKHUH�DUH�WUDQVODWLRQV�RU�FRSLHV�RI�VHYHUDO�DJULFXOWXUDO� PDQXDOV� IURP� &DWDORQLD� LQ� WKH� IRXUWHHQWK�FHQWXU\�49�7KH�PDMRULW\�RI�WKHP�DUH�WUDQVODWLRQV�RU�HGLWLRQV�RI�WKH�5RPDQ�ZULWHU�5XWLOLXV�7DXUXV�$HPLOLDQXV�3DOODGLXV��EXW�D�IHZ�DUH�WUDQVODWLRQV�RI�$UDELF�ZULWHUV�VXFK�DV�,EQ�DO�¶$ZDPP�DQG�,EQ�:DÀG��7KHVH�WUDQVODWLRQV�ZHUH�PRVW�RIWHQ�WKH�SURSHUW\�RI�ZHDOWKLHU�XUEDQ�LQGLYLGXDOV�LQFOXGLQJ�PRVWO\�UR\DO�DQG�FKXUFK�RIÀFLDOV��6FKRODUV�VSHFXODWH�MXVW�KRZ�PXFK�WKLV�LQIRUPDWLRQ�FRXOG�HYHU�KDYH�DFWXDOO\�PDGH�LW� LQWR� WKH� DJULFXOWXUDO� ÀHOGV� WKHPVHOYHV�� +RZHYHU�� LI�

48 Bruce M. S. camPbell, « Ecology versus economy in late thirteenth century and early fourteenth century English agriculture », in Del sWeeney (dir.), Agriculture in the Middle Ages: technology, practice, and representation, Philadelphia, 1995, p. 92.49 /OXtV�ciFuentes i comamala�� ©� (OV� VDEHUV� ~WLOV� DO�PyQ� UXUDO� FDWDOj�PHGLHYDO�� DJULFXOWXUD�� PHQHVFDOLD�� PHGLFLQD� L� FRQVHUYDFLy� GHOV�DOLPHQWV� ª�� LQ� &DWKHULQH� VERNA� DQG� 3HUH� BENITO� �HG�), Savoirs des

campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles, Études

roussillonnaises, revue d’histoire et d’archéologie méditerranéennes,

������S��������

75

Adam FrAnklin-lyonS : Grain yields and agricultural practice at the castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

74

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

poorhouses also encouraged both rationalization and capital reinvestment. They came to their positions already with a relatively high value on the idea of maximization RI� SURGXFWLRQ� DQG� SUR¿W�� EXW� ZLWKRXW� WKH� SRVVLELOLW\�of personal aggrandizement. As church canons and ultimately as employees of the poorhouses themselves, they would have had little or no incentive towards SHUVRQDO�JDLQ��LQVWHDG�WKH�SUR¿WV�JHQHUDWHG�E\�D�JRRG�\HDU�would be plowed back in to the general budget, allowing for further expansions of their landholdings and property; such reuse of capital made the purchase of large estates like Sitges possible. The economic savvy of many of these managers and their career long dedication to the institutions, combined with the substantial resources of the poorhouses, encouraged an agriculture focused on long-term productivity and increasing capital investment.

conclusion

Crop yields found at Sitges castle demonstrate the H[LVWHQFH� RI� VLJQL¿FDQW� SRVVLEOH� LPSURYHPHQWV� LQ� WKH�agricultural system of the late medieval Mediterranean. This runs counter to the view that crop yields were unable to increase beyond a minimum necessary for survival and barely budged from that point over the course of centuries. It also undermines some of the tenants of the Population-Resources model, particularly the idea that overpopulation lead inevitably towards land exhaustion and tended to be the governing force in agricultural productivity. Given the right set of circumstances, the land could be made to yield notably more than usually assumed, given the knowledge of the time period. What is especially notable about this fact is that most of the major technology used at Sitges does not represent any real leaps forward. Manuring, weeding, variable crop rotation, and irrigation all existed elsewhere in Europe and appear widely in the documentation. The knowledge of these techniques did not make as great a difference as their application. Using both the capacity of a well-funded institution, as well as their motivations as somewhat professionalized managers, the majordoms and procurators who ran Sitges castle and the farmland of other Barcelona hospitals invested intensively in both labor and capital, maintaining high yields and seemingly avoiding land exhaustion. The high use of wage labor also allowed them to avoid the bottlenecks of production that generally create diminishing returns on labor inputs.

7KH� SUR[LPLW\� RI� ODUJH� DQG� HI¿FLHQW�PDUNHWV� KHOSHG�make many of these choices possible. The availability RI� UHODWLYHO\� ÀXLG� IDFWRU�PDUNHWV� DOORZHG� WKH�PDQDJHUV�DW�6LWJHV� WR�PDNH� HI¿FLHQW� FKRLFHV�ERWK� LQ� ODERU� DQG� LQ�land inputs, responding to changes in both weather and the economy on a year-to-year basis. The evidence of a manure market, particularly concentrated near a city, allows for the concentrated population of the city to actually increase the fertility of nearby land; cities tend to produce an excess of manure from transportation animals, as well as all the animals entering to keep the meat market supplied. This would allow capital rich farms within a certain radius of major cities to avoid all problems RI� LQVXI¿FLHQW� OLYHVWRFN�� LI� LQGHHG� VXFK� SUREOHPV� ZHUH�widespread. While the notes in this essay are only preliminary in this regard, it would be worth knowing the extent of the manure market and how far people were willing to ship it. Finally, as David Stone noted for manors in England, the proximity or availability of a large market allowed the managers to respond to, “the best and most up-to-date price information they could obtain.”57 Another area of possible further exploration could be the methods that such institutions used to communicate such market information. The records contain lists of voyages and frequent travel between the various lands under the control of the Barcelona Cathedral Almoina, which might shed light on the spread of agricultural information between areas –unfortunately such a study is beyond the scope of the present work.

As studies of irrigation have frequently demonstrated, the necessary basis of many technological advances rests not in the invention or design of new tools, but rather in a social structure that allows for the marketing of rural produce and a consistent incentive to increase yields. In the absence of these key elements, even the presence or knowledge of immediately useful technology does not insure that it will be put into service. No practice at Sitges was groundbreaking or unique, and virtually all of them probably represented very widespread knowledge about how to raise grain. However, what this information does clearly demonstrate is how many variables a cultivator would have need to be able to control in order to achieve such consistently robust results. The cost, time, capital, and motivation must often have eluded much of the medieval farming population. Clearly, the procurators of Sitges castle found all of these techniques advantageous, cost effective, and worth implementing.

57 Ibid., p. 53.

where extra land is not readily available. Finally, the inability to fully participate in the grain market and the labor market further degraded the incentives necessary to consistently increase harvest outputs.52 If there is no obvious market for extra grain –or if that market is unreliable–, there is less clear incentive to increase the harvest of any single year.

On the lands owned by the poorhouses of Barcelona, such market forces would have been paramount to their desire for constant improvements in the output of their harvests. Sitges’ geography, the institutional practices of the Almoina and the background of its leaders all FRQWULEXWHG� WR� WKH� SUHVHQFH� RI� D� VWURQJ� SUR¿W� LQFHQWLYH�in their agricultural decision making. Every year the workers at Sitges loaded a ship with all of the produce both from Sitges as well as from surrounding towns like Vilafranca del Penedés. The wine, grain, and other goods were taken directly to Barcelona either to feed the inhabitants of the poorhouse, or more often for direct sale in the large, relatively free market available in such a large trading city. Geography could hardly have made for better market access. Indeed, the market, and information about market prices, was so close at hand that year-to-\HDU� GHFLVLRQV� DERXW� VDOHV� FRXOG� UHÀHFW� TXLWH� UHFHQW�changes in the Barcelona price. A recent article by Pere Benito demonstrates that the procurators at Sitges had the capacity and understanding to decide whether it would EH�PRUH�SUR¿WDEOH�WR�VHQG�JUDLQ�WR�PDUNHW��FRQVXPH�LW�LQ�house, or to store it in large granaries to wait for a better price in the open market.53 Even before laborers loaded the grain on the boat, the managers likely knew the Barcelona market price and could decide whether or not they would UHFHLYH�VXI¿FLHQW�UHWXUQ�IRU�WKHLU�LQYHVWPHQW��(YLGHQFH�RI�large scale storage on other properties such as Mogoda and in Vilafranca del Penedès provide a tantalizing hint that this practice might have been common throughout the Almoina properties, although the records are not VXI¿FLHQW�WR�SURYLGH�WKH�SURRI�DYDLODEOH�IURP�6LWJHV�54 We can safely assume that the proximity of Barcelona insured that mercantile incentives for maximization of outputs exerted a strong force on the choices made in agricultural investment.

Institutionally, unlike the manors of England described by Campbell, the forces acting on the Barcelona Almoina also came much more from market and contractual practices. The majordoms themselves tended to come

52 Campbell refers to this problem as the, « imperfections in the operation of commodity and, especially, factor markets. » See: Bruce M. S. camPbell, « The agrarian problem in the early fourteenth century », art. cit., p. 8.53 Pere benito i monclús, « Del castillo al mercado y al silo…», art. cit., p. 32-36.54 Unfortunately, the documentation at Mogoda is nowhere near as robust as that for Sitges, so such studies would be incomplete and less convincing than the work Pere Benito has done with Sitges. For storage in the other properties, see: ACB; Pia Almoina; 3: Administracions Foranes; D: Vilafranca de Penedes; 3. Llevadors de Comptes; 1330-1569 [Capsa Mayor II] – 1386; and ACB; V. Pia Almoina; B. Administració; 3. Administracions foranes; H. Casa de Mogoda, 1377, fol. 51r°.

from large mercantile families within Barcelona, raised in a society much more responsive to the demands of the burgeoning market than their more rural counterparts. This had several effects on the institutional direction over this period. Starting from the late thirteenth century, a VLJQL¿FDQW�PDMRULW\�RI�WKH�QHZ�SDWULPRQ\�RI�WKH�Almoina came in the form of direct rents and emphiteusis tenancies – a type of contract that privileges a constant cash based income over a variety of customary payments in kind. Over the tenure of several majordoms, the percentage of the holdings that produced cash rent increased steeply.55 During the middle of the fourteenth century, the Almoina used its cash reserves to purchase consolidating houses that would allow for central control of previously scattered territories. During the middle decades of that century, they purchased full rights over a manor in Mogoda, the complete rights to the mills at the Torre Balldovina, and, of course, the castle in Sitges itself, all with the goal of FRQVROLGDWLRQ�RI�PDQDJHPHQW�DQG�PRUH�HI¿FLHQW�FRQWURO�of their patrimonial resources.

Additionally, the records in the Barcelona cathedral from the Almoina and the other hospitals also show that the clerics might return to a job like majordom multiple times in their career, and also might move from institution to institution, acting as a professional class of hospital managers. For example, one majordom, Pere Feliu, served three separate tenures at the Almoina, from 1353 to 1357, from 1364-1370, and again from 1391 till his death in the middle of 1395. Berenguer Català served as majordom of the Cathedral Almoina from 1373-1375, possibly leaving WKH� SRVW� HDUO\� GXH� WR� GLI¿FXOWLHV�ZLWK� WKH� IDPLQH�� WKHQ��from 1379 till 1382, he served as the head procurator of the Hospital dels Malalts. Apparently retiring in 1382, he is subsequently listed as a EHQH¿FLDW of the Cathedral Almoina, receiving a stipend from their yearly budget. Their long tenures and semi-professionalized positions encouraged more practiced and rational decision making over the long term. Similarly, David Stone noted that when the managers at the Ely estates began to come and go with greater frequency and their professionalization and attachment to their positions declined, so to did their economic acumen and managerial ability. In contrast, at the turn of the fourteenth century, a new culture of SUR¿W� GULYHQ� DGPLQLVWUDWLRQ� KHOSHG� WR� FXOWLYDWH� VXFK�managers as the exceptionally effective Robert Oldman, who succeeded in selling between 60% and 90% of his wheat at its highest potential value over the course of his tenure as reeve of Cuxham.56 This professionalization RI� PDQDJHPHQW� HQFRXUDJHG� HI¿FLHQW� XVH� RI� WKH� ODQGV�under the control of the various hospital institutions of Barcelona.

Finally, the nature of the managerial positions in the 55 Thomas lóPez Pizcueta�� ©� (O� XVR� GHO� FRQWUDWR� HQ¿WpXWLFR� HQ� OD�gestión del dominio territorial de la Pía Almoina de Barcelona (siglos XIII-XIV) », Cuadernos de investigación histórica, vol. XVII, 1999, p. 155-189; Id., La Pia Almoina de Barcelona (1161-1350): estudi d’un patrimoni eclesiàstic català, Barcelona, 1998.56 David stone, Decision-making in medieval agriculture, op. cit., p. 216-219.

77

Adam FrAnklin-lyonS : Grain yields and agricultural practice at the castle of Sitges, 1354-1411

76

Savoirs des campagnes, Catalogne, Languedoc, Provence, XIIe-XVIIIe siècles

Appendix 1. Harvest data from the castle of Sitges

The following chart represents all of the available data from the harvest records at the castle of Sitges. Because of the nature of the records, some information is more easily gathered than others. The sale price (sous or solidos of Barcelona per quarter of grain) appears in almost every record book still in existence, although frequently the procurator only records the sale of the aggregate grain collected from both rents and harvest. This makes the price reliable but precludes any certainty about the TXDQWLW\�KDUYHVWHG�IURP�WKH�FDVWOH¶V�RZQ�¿HOGV��WKH�llauró or horta). Similarly, the labor payments will frequently PHQWLRQ� WKH� SODQWLQJ� RU� KDUYHVWLQJ� RI� VSHFL¿F� FURSV��allowing for great certainty in the rotational practice, but without giving any quantities, again obscuring the actual yield ratios. As noted in the main text, the actual size of WKH�¿HOGV�DQG� WKH�SHUFHQWDJH�RI� WKH�DUHDV� OHIW� IDOORZ� �LI�any) never appear in any of the record books, limiting the available data to yield as a ratio of seed. Finally, the “year” FROXPQ� UHSUHVHQWV� WKH� ¿VFDO� \HDU� RI� WKH� UHFRUG� ERRN��running from May of the year listed through to April of the following year; hence the quantities sown are drawn from the previous year’s record book (for example, in 1356, the 39 quarters of barley were harvested in June of that year, the 1.5 sown quarters were planted in November of the previous fall and appear in the 1355 documents).

WH

EAT

BAR

LEY

FAVA

S = B

RO

AD

BEA

NS

Fiscal Year

Harvested

from Horta

Sown

(in quarteres)

Harvested

(quarteres)

Yield Ratio

Sale Price

(in solidos)

Harvested

from Horta

Sown

(in quarteres)

Harvested

(quarteres)

Yield Ratio

Sale Price

(in solidos)

Harvested

from Horta

Sown

(in quarteres)

Harvested

(quarteres)

Yield Ratio

Sale Price

(in solidos)

13

54

��X

81

35

5�����

X���

101

35

613

X���

39����

���

X���

���

���

13

57

12X

���

30����

�1

35

8X

1411

���

�X

61

35

9����

7X

11���

13

60

16X

���

20�������

10X

610

13

61

����

X9

10X

121

36

2X

719

���

X2

13

63

18X

189

X���

4���

13

64

X����

26�������

147

X12

13

65

�����

X1

20����

����

X����

���

������

13

66

X1

8���

136

13

67

X2

���

X2

13

68

149

13

69

167

13

70

121

37

1X

13���

X1

37

2���

13

73

X10

8X

����

13

74

4020

X3

3***

���

13

75

40X

����

19�������

20X

���

����

������

13

76

X1

����

2012

X����

13

77

14X

��7

X1

13

78

X����

9������

126

X����

13

79

147

X1

38

014

13

81

138

13

82

14X

71

38

31

38

41

38

520

X10

13

86

20X

����

13

87

����

X����

����

������

8X

����

���

������

13

88

16X

����

9�������

���

X����

�������

13

89

����

X���

24����

7X

���

����

������

13

90

17X

2*31

������

81

39

1X

����

188

X���

13

92

X����

���

�������

18X

���

16*

�������

81

39

316

X2*

��

������

���

13

94

12X

217

�������

6X

���

13

95

XX

13

96

16X

����

���

X1

39

7X

18

�����

X���

10������

13

98

X���

18����

6X

����

����

������

13

99

12X

����

����

�������

61

40

013

X���

����

��������

61

40

120

X����

��

��������

81

40

2X

918

91

40

3X

���

10������

��X

���

�����

���

14

04

17X

���

��

����

81

40

5��

X2

����

������

���

X1

14

06

18X

228

����

81

40

7X

���

����

������

13X

6���

121

40

8��

X2*

28*

����

712

14

09

13X

2*22

*����

612

14

10

12X

���

20*

�����

���

X����

6*

Bar

ley

mix

ed w

ith o

ats

** B

arle

y m