GENERATION MINORITY COLLEGE STUDENTS WHO ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of GENERATION MINORITY COLLEGE STUDENTS WHO ...

WHAT ARE THE MOTIVATIONAL FACTORS OF FIRST-GENERATION MINORITY COLLEGE STUDENTS WHO

OVERCOME THEIR FAMILY HISTORIES TO PURSUE HIGHEREDUCATION?

DR. EDITH BLACKWELL, E D . D .

Morgan State University

DR. PATRICE JULIET PINDER, E D . D .

STEM Education Research Institute (SERI)Indiana University, Purdue University

The pathway to college is not equal for all students. Students from lowsocioeconomic backgroimds and minorities often face difficult chal-lenges in trying to obtain a college education. Thus, this study utilizeda qualitative grounded theoty approach to explore and to understandhow first-generation minority college students are motivated to over-eóme their family histories to achieve a college education. The studyconsisted of two groups of participants. The first group, the centralgroup of focus, was made up of three first-generation college students.The second group, the eomparison group, consisted of two third-gen-eration college students. Semi-structured interviews conducted in per-son and online were pivotal ways in which data were collected. Afterdata collection, the data were transcribed, coded, and emergent themesidentified. Results of the study revealed that first-generation collegestudents, unlike the third-generation college students in this study (theeomparison group), were not encouraged by family to attend collegebut their itmer drive to attend college to achieve a better way of lifefor themselves led to them being the first in their families to attendand to graduate from college. In light of the findings of this study, it issuggested that teachers become mentors who can encourage students,particularly, minority students to attend college.

Keywords: first-generation minority college students; motivationaldrive; poverty; and qualitative grounded theoty approach

Introduction households making less than $20,000 a year

Higher education is considered one of (McDonough, 2004). Those of low socio-the main paths leading to opportunify, social economic backgrounds and minorities facemobilify, and economic progress in the U.S. difficult challenges every step of the way. In(Carey, 2004). However, the pathway to col- addition to socioeconomic issues, inadequatelege is far from equal for all students. The academic preparation, lack of available infor-majorify of first-generation college students mation, and lack of peer counseling are alsoare from low socio-economic backgrounds, some of the daily roadblocks these studentsFor instance, 50% of high school graduates face as they strive to become the first inin 2008 came from households making less their extended family to attend college (Mc-than $50,000 per year, and 16% came from Donough, 2004).

45

46 / College Student Journal

Statistics show the low rates of first-genera-tion college students in the USA between 1992and 2000. In 1992, 20% of the reported firstyear college students were first-generadon col-lege students, and between 1993 and 2000,22%of first year college students were first-genera-üon college students (Wirt et al., 2004). Whilethe attendance rate of first-generation collegestudents remains significantly lower than thatof students with college-educated parents, thelevel remains at an average of about twen-ty-five percent. These first-generation collegestudents are seen as "barrier breakers," as theyare breaking down barriers or obstacles toachieve their goals of higher education. Thisqualitative study was designed to understandhow these first-generation college students aremotivated to overcome their family histories toseek a fulfilling academic pathway.

This study explored the motivational fac-tors of first-generation college students withthe focus of interest being on a single individ-ual within a large family (for the purpose ofthis study, a large family was defined as fiveor more children). Thus, the essential questionof this study was: What are the motivationalfactors of first-generation minority collegestudents who overcome their family historiesto ptirsue higher education when their siblingsdo not?

SignificanceThe theories generated from this qualita-

tive grounded theory research study shouldhelp families and educators to develop mo-tivational tools that can be used to inspiremore students of low socioeconomic status topursue higher education. As the U.S. movesfrom a more industrialized to a technologicaleconomy, higher skill levels will be required.A more educated family will positively affectthe citizens of the community, as well as thenation's workforce. Recently, technology jobshave been outsotirced to college-educated in-dividuals in foreign countries that are willingto work for much less than the average wage

of similar workers in the U.S. (Carey, 2004).The loss of these jobs has decreased the levelof job opporttmities that provided a middleclass income. Without a college degree, thoseof low socio-economic status face an tmcer-tain futtire, and might lose the ability to max-imize their earning potential and to improvetheir current living conditions.

Conceptual Framework

Researchers (Deci & Fiaste, 1995; Reeve,2005; Schunk & Pajares, 2002; Wigfield &Eccles, 2002a; Zeldin & Pajares, 2000) agreethat behavior is infiuenced by personal factors(motivation or intemal factors) and by en-vironmental factors (extemal factors or out-side influences). Sansone and Harackiewicz(2000) define motivation as a behavior thatis directed by the need or desire to achieveparticular outcomes. "Motivation energizesand guides one's behavior toward reachinga particular goal in life" (Sansone & Harac-kiewicz, 2000, p.2). Deci and Fiaste (1995)determined that it was a sense of autonomythat motivates students. Their research foundthat students needed a sense of having someconfrol over their lives. They also discussedconfrolled behavior, which is based on rigidauthority, an opposite effect of autonomy.This confrolled behavior has two forms:compliance and defiance. Compliance occurswhen an individual does what is expected;whereas, defiance occurs when an kidividu-al behaves the opposite of what is expected.Deci and Fiaste (1995) determined that moreautonomy, nurturing, and support are import-ant factors of self-motivation.

Self-efficacy, defined as the belief in one'scapability to leam or to perform, influencesself-motivation (Schunk & Pajcires, 2002).Self-efficacy is grounded in Bandura's socialcognitive theory. Bandura's theory (Zeldin &Pajares, 2000) defines the role of self-effica-cy as people's level of motivation, affectivestates, and actions. Self-efficacy is based

Motivational Factors of First-Generation Minority College Students / 47

more on what people believe, than on what istme. How people behave can be predicted bywhat they believe themselves capable of ac-complishing. Zeldin and Pajares (2000) state"self-efficacy beliefs provide the foundationfor human motivation, well-being, and per-sonal accomplishment; unless people believethat their actions can produce the outcomesthey desire, they have httle incentive to act orto persevere in the face of difficulties" (p.3).

Motivation is intemal and is derived fiomthe forces within the individual and in the en-vironment (Reeve, 2005). Reeves explainedthat an individual's intemal experiences arebased on cognitions and emotions and arederived within the individual. The extemalfactors which can also inftuence an individ-ual's motivational state can include, but arenot limited to parental inftuences and peerinfiuences. Although most feel that intrinsicmotivation has a far greater effect on a per-son's outcome, environments are believed toplay a role in the process as well. Zeldin &Pajares (2000) posttilated that social cognitivetheory factors, such as economic conditions,socioeconomic status, and educational and fa-milial stmctures do not affect htiman behaviordirectly. Instead, Zeldin and Pajares believedthe aforementioned social factors affect hu-man behavior only to the degree that theyinftuence a person's aspirations, self-efficacybeliefs, personal standards, emotional states,and other self-regulatory influences.

The family environment can influenceself-efficacy through parental support and en-couragement. Parents can niuture and supportchildren, while stimulating curiosity and en-couraging self-discovery (Schunk & Pajares,2002). Parents who provide this type of envi-ronment can promote intellectual developmentof their children (Wigfield & Eccles, 2002a).Between the ages of eight and sixteen, peerpressure influences students, while parentalinfluence declines around twelve years of age.Wigfield & Eccles (2002a) also determined

that children associated with highly motivat-ed groups change positively, and peer groupacademic socializations may influence a stu-dent's self-efficacy. School environment canalso influence the self- efficacy of a studentthrough comfort, a sense of relatedness, andthrough the fostering of a sense of autonomy(Wigfield & Eccles, 2002a).

Researcher Context

As defined hi Creswell (1998), this studycan be described or defined as a "backyard"study. This study is called a backyard studybecatise the primary researcher (first author)also experienced the same phenomena aswas identified within this study. The primaryresearcher was also the first of a family of mi-nority siblings to attend tmiversity. Thus, the"hiside/insider knowledge" that the primaryresearcher brought to the study helped all ofthe researchers to better understand the plightand experiences of the study's participants.Thus, the researcher effect here was seenmore as a positive effect than as a negativeone as no bias views or perspectives werebrought into the study.

Research Questions

The overarching question that guided thisresearch study is: What were the factors thatmotivated first-generation minority collegestudents to overcome their family historiesand to become the first in their family to ptir-sue a college education/degree? Additionalfield questions that guided this study were:

1. What experience(s) made you decideto attend college?

2. How were your home or high schoolenvironmental experiences differentfiom yotir siblings? And, do you thinkthis led to yotir decision to attend col-lege and not your siblings?

3. Who were the people who influencedyour decision to attend college?

48 / College Student Journal

4. Why was attending college importantfor you?

Methodology

This qualitative research study used agrounded theory approach in order to un-derstand the motivational factors that ledto an academic path for the first-generationcollege participants as opposed to their sib-lings. Utilizing a qualitative research methodwas best for trying to understand the "drive"experienced by these students and the mean-ings they assigned to these experiences.Inductively analyzing the data to form a the-oretical model was suited for this groundedtheory method. The sampling of participantsfollowed a two way process. First, a small,yet homogeneous selection of women (whohad the unique experience of being the firstin their family to attend college) was chosen.Next, a smaller heterogeneous sample ofthird-generation college students was chosento help the researchers to frulher understandthe phenomena, and this group of third-gen-eration college participants also served as acomparison group.

Research paradigm

The research process that guided thisstudy included the use of inductive knowl-edge to describe the context of the experienceof the participants in detail. Both axial and invivo codes were utilized and questions wererevised between interviews. A questionnairewas developed and administered afrer initialanalysis to some participants in cases wherethe researchers needed further clarificationfrom the participants (Creswell, 1998).

We also explored the meanings the partic-ipants attached to their behaviors by askingthem to tell their stories in detail, followingthe "hermeneutic tradition." The hermeneutictradition developed by Wilhelm Dilthey andMax Weber (1911/1997) cited in van Zyl,Cronje, & Payze (2006) and Stake (1978)

focuses on the subjective understanding of in-terpretation. Dilthey (cited in van Zyle, Cron-je, & Payze, 2006) believed that the humansciences involved the tinderstanding of hu-man behavior and social phenomena from theperspective of the participant rather than fromthe perspective of the observer. The emphasisof this study was placed on the perspectivesand interpretations of the lived realities of theparticipants (van Zyl et al., 2006).

Participants

There were two groups of women inter-viewed. In the first group, there were threewomen, all were first-generation college stu-dents. The ages of the first participants were53, 54, and 72 years. One of the participantswas the eldest of a family of nine; one wasthe youngest of a family of nine, and the thirdparticipant was a middle child in a familyof five. All were African-Americans and allthree went to college immediately afrer highschool. All three were married. All were askedseveral field questions. The second group ofparticipants (the comparison group, per se)received a questionnaire instead of specificfield questions. The second group of partic-ipants was also African American females,but unlike the first group of participants, thisgroup was made up of third-generation col-lege students. Each of the two participants inthis second group (the comparison group) hadonly one sibling. Also, the participants in thesecond group all went to college immediatelyfollowing high school. The ages of the partic-ipants were 41 and 53.

Data Collection and Analyses

Data was collected by way of semi-stmc-tured interviews. Audio-cassette recordingsand follow-up phone conversations wereconducted. Data collection and analyses oc-curred simultaneously (Creswell, 1998). Eachparticipant was interviewed from a list of tento twelve questions. The data consisted of twothirty minute audio-cassette recordings and

Motivational Factors of First-Generation Minority College Students / 49

approximately eighty minutes of follow-upphone conversations. In accordance withthe procedures for grounded theory researchoutlined in Sfrauss and Corbin (1990), thedata was reviewed repeatedly, with the firstinterview data read over eight times and thesubsequent interview data franscripts wereread at least six times. Questions given tothe final interviewee changed slightly overtime. The audio-cassette recordings and datataken from phone interviews were franscribedverbatim by the researchers. After transcrib-ing the data, the data was coded, with somegenerating as many as 30 to 40 initial codes.A list of codes was determined after eachreading of the interview data, to determineif any meanings were missed from previousreadings. The final lists of open codes from allinterview sessions were categorized based onwords and phrases used by the participants.The categories and subcategories were identi-fied by in vivo coding, ñirther condensing thedata, resulting in six to seven main categories

for each interview. This was followed byaxial coding. The data was ftirther analyzedby triangulation between the primary re-searcher's personal reftections, participants'questionnaires, audio-cassette franscripts ofparticipants, and follow-up phone conversa-tions with participants.

The follow-up phone conversations servedtwo purposes, first, to discuss the theories thatemerged from the first set of data analyzed.This led to additional sampling of subjectswho had the opposite experiences of the firstinterviewed participants, that is, they werenot the first ones in their families to attendcollege. A questionnaire with three ques-tions was given to the two females who werethird-generation college students, and theiranswers transcribed. The questions posed tothese third-generation college attendees wereas follows:

• Why did you go to college?

• Did you really want to go to college

Parents:Improveyour life!

Refused tolive as Igrew up

Have towork andpay tuition

Gruelingexperience

Poor, nomoney

Limitedopportunity

The path tocollege

Loved toRead!

Readingfromschool

This is myway out!

Hardest thing Iever had to do inMy life!

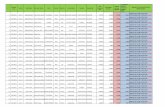

Figure 1. Partial example of initial open coding

50 / College Student Journal

• Did you major in the subject you want-ed to

• Did your siblings go to college?

The data from the aforementioned ques-tions were not combined with the first set ofdata taken from the first-generation collegeattendees. But rather, this set of data fromthe third-generation college attendees wereused to disconfirm evidence as a method ofestablishing credibilify (Creswell, 1998). Ina further effort to eliminate bias, each theo-ry developed was discussed and confirmedby the participants in the study. The secondptirpose of the follow-up conversations was toidentify any biases that may have existed.

Open Coding to Categories

The open phrases were searched forthemes. The themes are labeled in brackets.

1. birth order (middle child)

2. smart siblings (siblings)

3. one had military career, two werecops (respectable jobs) siblings

4. college aspirations (motivation)

5. parental support (parents)

6. financial issues (no money)- (poverfy)

7. limited options for women -(availabil-ify of jobs)

8. no money-(poverfy)

9. worked hard to achievegoal- (intrinsic-motivated)

10. taught responsibilities- (responsible)

11. worked 2 jobs while going to school—(intrinsic-motivated)

12. determination-must finish-(intrinsic- motivated)

13. education will lead to better opportu-nities (ex. Motivation)

14. proud of parents' strength- hard work(parents)

15. saw people who were successftil (rolemodels)

16. exposed to a bigger world throughreading from school (reading-school)

17. reading expanded my view of theworld- (reading-home)

18. family considered her to be strangeand different- (different).

The themes were then condensed into cat-egories. Here is the listing of categories:

Categories:

Birth order Siblings

Middle child smart-Decent jobs

Motivation for college (extrinsic)

Better opportunitiesLack of available jobsRole modelsReading-school

Intrinsic motivation

Had to work hardDetermineddifferent

Parental Influence Finances

Supportive poverfyParents worked hard

Findings

Camal ConditionsThree causal conditions were the moti-

vating factors that pushed these students to-ward higher education. The causal conditionswere: (a) a love of reading at an early age,(b) they each felt different from their siblingsfrom an early age, and (c) they all wanteda better life for themselves. The first causalcondition of loving to read was shared by allthree first-generation participants. One of theparticipant's story was outlined here. Edna's

Motivational Factors of First-Generation Minority College Students / 51

early education was a two-room school whichshe felt was substandard. She and her school-mates reportedly went to school only threemonths out of the year, and it took them twoyears to complete a grade. Edna later movedwith her sister to New Jersey at age twelve. Itwas in New Jersey that she discovered howfar she was behind the rest of her classmates.She was later able to catch up with her schoolpeers by the ninth grade. She recalled hav-ing to read constantly to leam, and improveher life. Another first-generation participant,Joan recalled her life being similar to thatof Edna's. Joan stated "I read all the time; Iwould escape my life through books!" So, itwas through reading that Joan started think-ing about college. The third first-generationcollege participant in this research study wasBarbara. Like Edna and Joan, she too lovedreading. Barbara recalled her childhood beingone in which she read biographies of peoplefrom humble beginnings. She particularlyliked reading about people who started outpoor and later acquired wealth.

The second causal condition experiencedby all three women was their perceived dif-ferences from that of their siblings. Barbarastated "I was different, reading set me apart."She also said her siblings did not share herlove or passion for reading. Joan also feltdifferent from her siblings, but she thought atthe time that it was due to her being the onlygirl in a family of four brothers. As an adult,she remembered a conversation she and herteenage niece shared:

"Aunt Joan, you sure are different fromthe rest of them!" "I love my grandmato death, but you are nothing like them.Are you sure you're part of this family?You know people were having babiesback then, and letting other peopleraise them!" Sometime later, she cameback to me and said, "You know AuntJoan, they got this test now, called aDNA test, and I could get the informa-tion for you!"

Edna felt different also, but she was notstire if it was due to her having spent a lot ofher early childhood alone. She talked aboutplaying with the cats and the dogs when shewas little.

The third and final catisal condition iden-tified in this study was each participant'soverwhelming sense of determination to havea better life than the one they experienced aschildren. When asked why college was im-portant to them, each of them stated that col-lege was seen as a ticket out of the situationat the time.

"I was not going back to the coun-try! That was a no-no! Period! I wasdetermined not to go back home toSouth Carolina to work in the fields. Icouldn't stand there when I was there,and my mom was eager for me toleave. She wanted us to go and betterotirselves." -Edna

"I saw my only other avenues as ba-bies, welfare and continuing to live inthe projects. I wouldn't live the waymy mother did, working two jobs. Sheworked hard in a Laundromat. I knewif I ever wanted to change my life, itwould be through education. There wasno way I was not going to do this!-Joan

"I needed a better living situa-tion. I needed to know that povertywas not going to be my ultimateexperience- Barbara

The PhenomenaAlthough each of the first-generation col-

lege participants in this study attended collegeimmediately after high school; the jotimeywas not an easy one. All of them workedthroughout college, and Joan and Barbaraworked two jobs. Edna's sister helped topay for some of her tuition, while Joan andBarbara worked to pay for their own tui-tion. Barbara stated "college was a gmeling

52 / College Student Journal

experience." She experienced a period in hercollege years where she had to be hospital-ized for stress. Working two jobs and attend-ing fiill-time classes had taken its toll on herphysical health. That was a wake-up call andshe stopped neglecting her health.

Joan also stated that attending collegefUU-time and working were the most difficultthings she ever had to do in her life. She re-membered being scared when she was placedon academic probation once, and was so ter-rified she may be asked to leave, she never lether grades drop again. Edna said she was gladwhen it was over. Despite the hardship, eachparticipant felt college was worth it, and stat-ed that they would do the same thing if theyhad to do it over again.

ContextThe terms "poverty" and "poor" were used

by all interchangeably. Edna and Barbarawere both raised in a rural area in the south,one in South Carolina and one in North Car-olina, both with large families and a strongsense of what it meant to be poor. Both de-fined rural as "having no ninning water," andEdna, the elder of the two, also described herhome as having no electricity, and no pavedroads. Edna repeatedly used the phrase "therewas no money!" The commtmity in which shelived was poor, and there was only one carin the entire neighborhood. She talked abouthow her father worked on a logging job allweek, living in a shack, and came home onFridays, earning just twenty dollars! Barbarasaid her family home was rural and they hadno indoor plumbing. She stated that her grand-father had running water, but it was only coldwater, and they still had to heat it for baths.Joan described her childhood as poor as well.Her family Hved in public housing (govem-ment sponsored housing, locally known as theprojects), and her mother worked long hoursin a Laundromat. Her neighborhood offeredlimited options for job opportunities.

Schools in poorer neighborhoods do nothave the available resources as those in uppermiddle class neighborhoods and even lesswas available sixty years ago. Edna recalledhaving a substandard education early in lifeand it created hardship for her. For you see,Edna had attended a two-room school earlyin life and spent two years in the same grade.She went to school only three months out ofthe year. She felt the teachers were unquali-fied and she stated "the government did notprovide us with an adequate education." Ednawent on to indicate that the high school wasin the next town, over twenty miles away, andno transportation was provided to get them toschool. Her older sisters went to town and hadto live with relatives through the week, just tobe able to attend high school. Joan said,

"when I told my mother I wanted to at-tend college, it knocked her for a loop!She didn't know where to begin! Shetold me I would have to pay for it and Iknew that, but I give her a lot of credit.She found out what I needed to do, andovercame all sorts of obstacles to getme the information I needed."

Intervening ConditionsParental support was a strong influence

in the backgrotind of each of the partici-pants. Edna's mother and father not only lettheir older daughters move in with relativesthrough the week to attend high school, theylet their youngest move to another state withone of their older children, to give her a bettereducation. Joan's mother overcame obstaclesto find out what her child needed to do to beable to go to college. Barbara's parents weresupportive of her decision and constantly en-couraged her in whatever she wanted to do.Although the parents of all three participantswere not educated, each participant in thisstudy exhibited a level of respect for theirparents who gave them a strong work ethic.

Motivational Factors of First-Generation Minonty College Students / 53

Barbara was the most influenced by herteacher. The other two participants were notas inspired by their teachers. Barbara recalledhow her teacher in the third and fifrh grade(same teacher) taught her and her schoolpeers how to read, write, and do arithmetic.She recalled that her teacher exposed them toculture and sports and even dancing as well.Although, Joan's influence did not come froma teacher, like Barbara's did. Still Joan recallsan experience with a visiting educator whichhad a lasting impression on her throughouther middle school years.

"I remember once, when I was aboutin the fifrh grade, and I was sitting at atable in the cafeteria with my friends.This was like 41 years ago! this ladycame in, sharp, dressed in a white suit.She stopped at our table, and told usshe made S10,000 a year (a lot of mon-ey at that time),and asked us how muchwere we going to make, when we grewup? That's all she said. I didn't knowwhy she was at our school, but I re-member how good she looked!"- Joan

A ctions/StrategiesJoan and Barbara were friends who

supported each other throughout the collegeprocess. Their common backgrounds anddetermination to succeed molded a friendshipthat is still ongohig. This was their main cop-ing strategy as they drew strength from eachother. Edna made friends in college, but hersister was a strong influence in keeping her inschool. In this study, each participant focusedon the outcomes of their hard work. Barba-ra said "If it had been done before, I knew Icould do it!" Joan stated "there was no way Iwas not going to do this!"

ConsequencesAll three participants achieved their goals

of changing their lives through education.They broke away from their family histories

and graduated from college. Two of themnow have advanced degrees. One is ctirrentlya nurse, another a chemist, and the other aneducation administrator. The siblings of theparticipants are working, some of them invery good positions, although they did notpursue the college path.

Discussion

The experiences of first-generation col-lege students were vastly different from thosestudents whose parents were college educat-ed. A telephone survey of two third-genera-tion college students (who participated as apart of the comparison grouping in this study)confirmed the differences. These third-gener-ation college students did not have to makethe decision to attend college, it was made forthem. They knew from early childhood thattheir parents expected them to attend college.Deidre, a participant in the second groupof participants in this study (the third-gen-eration college attendees-the comparisongroup in this study, per se) recalled that hergrandfather was a school principal and she,her mother, and brother spent a lot of time onthe college campus that her father attendedwhen her father went back to school for anadvanced degree. Deidre stated that she andher sibling were taught the value of a collegedegree and it was understood that they wouldattend college. The youngest of the secondgroup of participants in this study, Panla wasbom into a family of educators; both parentswere teachers and also her two aunts. She andher sister both went to college, and as in thecase of Deidre, Paula stated going to college"was expected in our family, it was like anextension of high school, which was commonin our family." However, "my parents let usmajor in what we wanted, as long as we couldpresent to them a list of possible job opportu-nities that could come from otir majors."

The strategies used by tbe first-genera-tion college participants in this study were

54 / College Student Joumal

Causal Conditions

Motivating (internal) factors-A love of reading-Considered "strange" or "different"-Determined to have a better life

Phenomenon

-First and only one of a large famuy to attend college;siblings did not choose to do so

Context

-Overcame poverty-Lack of available information-Sub-standard early education

Intervening Conditions

Environmental (external factors)- Parental encouragement- Influenee of teachers, educators

Actions/Strategies

-friends in the same situation made coping mucheasier for these students-family support-goal oriented

Consequences

-achieved goal of college degree-found sueeess in education-two obtained advanced degrees

generated as an internal method for survivalduring a very intense experience. Familysupport and establishing connections withstudents in the same situations were bothexternal influences, however, goal orientedbehavior was an internal motive based on thecognitive needs of the individual. Excerptsfrom Cushman's (2005) First in the Familymirror the views of the participants in thisstudy. Some of them are listed below:

"I didn't have a big sister or brother oreven a cousin to go to and say, what didyou do in order to get in? So I read oth-er people's accounts in books. Thingsdon't always fall in your lap; you knowwhat I'm saying? Like, everybody'snot searching you out. You have to takethe initiative."

-Mema Jordan, Oakland Tech HighSchool graduate 2004; NorthwesternUniversity graduate 2008 (p. 6).

"Education was going to be my ticketout of here," says Eric Polk, now an un-dergraduate at Wake Forest Universityin North Carolina. "The first frain thatcomes to Nashville, I'm getting on it. Iwon't be defined by a statistic, like . . .how people who grow up in this areaare more likely to turn out." (p.6).

Kathleen Cushman states that these stu-dents shared a fierce determination to achievetheir goals. The Ithacan online (2006), quotesstudent Tracy Gillaspie when she says,

"I saw what my parents wentthrough-living week to week, not know-ing what we could afford, I wanted morethan that, and I realized that I was goingto need an education to get it."

Conclusion, Limitations, and Implications

There were two major limitations in thisstudy. The first limitation involved the lack of

Figure. 2 Paradigm Model

Motivational Factors of First-Generation Minority College Students / 55

information from the siblings of the study'sparticipants. The researchers were unable tospeak with any of the siblings of the partici-pants. Thus, confirmation on the participants'stories was not obtained. Confirmed stories ofthe participants' siblings would have enrichedthis study, and may have increased the levelof understanding of each participant's story. Asecond limitation was the small sample size. Alarger sample could have provided a clearerpicture of the experiences of first-generationand third-generation college participants.

The purpose of this study was to under-stand the motivational factors of first-gener-ation college students and to develop a the-oretical model that could be applied to theirsituations as well as to other students in simi-lar situations/circumstances. "Becoming sen-sitive to the motivation of students who havebeen socialized in similar ways and who sharecommon histories is no easy task" (Ginsberg& Wlodkowski, 2000). It is not possible toreproduce that strong internal drive found inthese students; however, the environmentalfactors can be improved to facilitate a set ofconstructs that can be expanded to includeschool influence as well as parental support.The theoretical model developed below couldbe used as a motivational tool.

In school environments, it would be ide-al if all students could develop peer supportgroups, but due to differing personalities werealize that it is not always possible. In caseswhere parents cannot assist, teachers can fillin the parental gaps by becoming mentorswho can encourage students to continue theireducation. Teachers can be role models whocan inspire students to attend college. Spe-cifically, minorify K-12 students need to seecollege graduates that look like themselves.Finally, attending and participating in familyevents on college campuses could provideminorify families with sufficient exposurethat might encourage more minorify childrento want to attend college.

External Motivating Factors

Sehool

*Peer support groups*Teachers as mentors•Teachers as rolemodels

*Inerease methods ofencouraging reading

Family Life

• Encourage family librarytrips, and encourage fam-ily events held on collegecampuses.• Promotion of college out-reach programs, specificallyfor students whose parentsare not college- educated

ReferencesCarey, K. (2004, May). A matter of degrees: Improving

graduation rates in four-year colleges and universi-ties. Washington, DC: Edueation Trust.

Creswell, J. W. (1998/ Qualitative inquiry and researchdesign, choosing among five traditions. ThousandOaks, CA: SAGE PuhUcations.

Cushman, K. (2005). First in the family, your collegeyears. Providence, RI: Next Generation Press.

Deei, E. L., & Fiaste, R. (1995). Why we do what wedo: understanding self-motivation. New York: NY:Penguin Group.

Ginsberg, M. B., & Wlodkowski, R. J. (2000). Creatinghigh motivating classrooms for all students: A schoolwide approach to powerful teaching with diverselearners. San Francisco: Jersey-Bass.

McDonough, P. M. (2004). Counseling matters: Knowl-edge, assistance, and organizational commitment incollege preparation. In W. G. Tiemey, Z. B. Corwin,& J. E. Colyar (Eds.), Preparing for college: Nineelements of effective outreach. Albany, NY: SUNYi*ress.

Reeve, J. (2005). Understanding motivation and emotion.Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Sansone, C , & Haraekiewiez, J. M. (2000/ Intrinsic andextrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motiva-tion and performance. San Diego: Academic Press.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development ofacademic sclf-efficaey. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eeeles(Eds), Development of achievement motivation: Avolume in the educational psychology series (pp.15-31). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Stake, R.E. (1978). The ease study method in social m-i{Wiy. Educational Researcher, 7(2), 5-8.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basis of qualitative re-search: Grounded theory procedures and techniques.Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

56 / College Student Journal

van Zyl, J. D., Cronje, E., & Payze, C. (2006) LowSelf-esteem of psychotherapy patients: A qualitativeinquiry. The Qualitative Report, 11{\), 182-208. Re-trieved from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QRll-l/vanzyl.pdf

Wigfield, A., & Eceles, J. S. (2002a). Children's motiva-tion during the middle school years. In J. Aronson(Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Contribu-tions of social psychology. San Diego: AcademicPress.

Wirt, J., Choy, S., Rooney, P., Provasnik, S., Sen, A., &Tobin, R. (2004, June). The condition of education2004 (U. S. Department of Education No. NCES2004-077).

Zeldin, A. L., & Pajares, F. (2000). Against the odds:Self-efBeaey beliefs of women in mathematics, sci-entific, and technological careers. American Educa-tional Research Journal, 37, 215—246.

Author Note

Dr. Patrice Juliet Pinder, ED.D. is a STEMEducation Research Specialist who is thecorresponding author and editor of this paper,so significant editing of this paper was com-pleted by Dr. Pinder. Additionally, Dr. Pinderhas written about 30 STEM education relatedpapers, which include: peer-reviewed jour-nal research publication papers, conferencepapers, grant proposals, and other academicpapers. Dr. Pinder has also published a STEMEducation book in 2013 titled "Issues and In-novations in STEM Education Research" andis currently working on her second STEM Ed-ucation book titled "Socio-culttiral Issues inK-16 STEM Education: Global Perspectiveson Race, Gender, and Migration Flows."

For further information conceming thisarticle, you may contact Dr. Pinder at: [email protected].