From Church-Based to Cultural Nationalism: Early Ukrainophiles, Ritual-Purification Movement and...

-

Upload

ukrainiancatholic -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of From Church-Based to Cultural Nationalism: Early Ukrainophiles, Ritual-Purification Movement and...

OSTAP SEREDA

FROM CHURCH-BASED TO CULTURAI,NATIONALISM : EARLY UKRAINOPHILE S,

RI TU A L- P U N F I CATI OI{ M OV EM E NT AN DEVIERGING CULT OFTARAS SHEVCHENKO IN

AUSTNAN EASTERN GALICIA IN THE 1860S

'l'his articlc aims to explore one of the turning points in the history of

Llkrainian nation-building in nineteenth-century Austrian Eastern Galicia"This process, and the rivalry among supporters of different concepts of the

national identity of Galician Ljkrainians (customarily called at that time

Rutheniurs), became the focus of several path-breaking studies over thelast two decades.r Some authors treated the shaping of a national identity'in terms of profound cultural transformation, discoursive shift and elabora-tion of new meaning.2 In the course of forming national discourse(s), edu-cated Ruthenians reconsidered in different ways the identificatory conceptsthey inherited from the pre-modern era, such as "Slavdom," "Rus',""Ukraine," "Greek Catholicism," and so on. Nation-building among theRuthenians of Galicia not only influenced how other potential modern na-

tions, Polish and Russian, were built, but aiso contributed to the process ofthe disintegration of various pre-modem, proto-national communities (like

Pof ish rroble natio, Slavia Orthodoxa, or Rus'), As Yaroslav Hrytsak per-

ceptively stresses in a recently published article, "the making of modemtlkraine \,vas not just unmaking of modem Poland, Rus', or Russia. It wasalso the unmaking of pre-modem Rus'. Therefore, modern nation-buildingamoug ttrose Habsburg Ruthcnians who also belong to Rus' (Ruthenia)was, in a senst:, more complicated than for the Habsburg Poies."3

l . Sce thc most rcccnt historiographical survey of this f icld in Marian Mudry,"Natsional 'no-pol i tychnr oricnta$i i v ukratns'kornu suspi l 'stvi [ lalychyny avstr i is 'koho

lreriodu u vysvitlenni suchasnoi istoriografii," Visn.l'k i..'t'ivs'koho i.lnitertltetu. Seria i.s'

I ttr'.t'c hna 31 / | (2002): 465-500.2. Scc the ssminal sturly ofthis prohlem by john-Paul t l imka, "The Conslruct ion ofNa-

rional i ty in Galician Rus': Icarian Fl ights in Ahnost Al l Direct ions." in Ronald Crigor Suny

arrd Michacl D. Kcnnedy. c,Js., lntel!ectuals und the,4rtitulation of lhe NalLotl (Ann Arbor.

MI: lJnir ' . ol 'Michigan Press, 1999), pp. 109-64.3. Yarrrslav l{rytsak. "Crossroads of East and West: Lcnrbcrg, l.w6u', L'viv on thc

'Ilrrcslrol tl ol Modernity," ,4 us t ri an I I is t o rl' )' e a rb oo k 34 (2003): 1 08.

canadian American slavic Studies/Revue canadienne Am6ricaine d'6tudes slaves

This article attempts to highlight one of the aspects of the transition

from haditional Ruthenian church culture to modem Ukrainian national

culture in Galicia by illustrating horv the emerging cult of Taras

shevchenko was connected with the ritual-purihcation (ohriadoryi)

movement. It shall also shed some light on how religioirs elements of

Ruthenian identity became "nationalized" and politicized, and how in turn

a new secular cultural system acquired crypto-religious character'

Since 1848, the entire Ruthenian national movement was organized

around the hierarchy of the Greek Catholic Church. It emerged out of

ethno-confessional tensions with Polish Roman catholics, dominant in

Eastem Galicia. At that time, loyalty to the Greek catholic church was

considered an essential part of Galician Ruthenian identity, and the Church

was the main symbol of the Ruthenian nation, history and culture. One

perhaps may call the Ruthenian national movement prior to the constitu-

tiona! reforms of the 1860s as "church-based nationalism," paraphrasing

how the movement was characterized still in 1862 (tserkovno-narodnyi)'.

Starting from the political modernization of the 1860s, new cultural insti-

tutions of Ruthenian (lJkrainian) nationalism emerged. By analyzing this

evolution, one may observe the interplay of religious and secular elements

in modern nationalism, and trace how tlkrainian cultural nationalism

gradually superseded the more traditional Ruthenian church-based nation-

alism. This pfocess was not unique in the case of Galician Ruthenians and

reflected the emergence of modern national cultures out of the spiritual

sphere of the Slavia Orthodoxa.

Nineteenth-century Galicia was a Flabsburg crownland with an agricul-

furally-based economy and social strtlctrre, numerous small towns and two

important cultural and administrative centers, L'viv and Krak6w. Its popu-

lation was ethnically diverse and consisted mainly of three ethno-religiousgroups: Greek Catholic Ruthenians, Roman Catholic Poles and Jews'

These'three groups comprised in 1857 respectively 44.83 percent, 44'"14

percent and 9.69 percent of the whole population.a In the eastern part of

4. These figures are calculated ftorn the 1857 Austrian census. See KrzysztofZamorski.

Informator statVstyczny do dziej(ttrt spoleczno-gospodarczych Galicji. Ludnolc GaliQi tt

latach t857-19l0 (Krak6w, 1989), pp. 69-71. Thc absolute number of the inhabitants of

Galicia in 1857 was 4,632,866 in total, including 2,077,112 Ruthenian Greek catholics,

2,072,633 Roman Catholics and 448,973 Jews. According to the 1869 census, these three

groups comprised respectively 42.53 percent, 46.08 percent and 10.57 percent of5,444,689

Galicians. The number of Roman Catholics includes small number of Catholic Czechs an<l

Germans. The rapidly changing portion of Greek Catholics and Roman Catholics in the

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in the I g60s 23

the province, Eastern Galicia,5 Greek catholics were the majority (66.53percent in 1857),6 although the representative landed "lurs, ,rlor'hla, usu-ally regarded itselfas a part ofpolish noble narjo.

John-Paul Himka rightly comments that "religion, or rather rite, wasone of the most constant factors differentiating [ftrainians from poles."?F-or the most par| of the nineteenth century, the history of Galician Ruthe-nians could be written as the history of the Greek catholic church in aprovince that traced its origin to the church tjnion of Berestia (1596).cireek catholics in Galicia had a long history of struggle for equal rightswith the Roman catholics. Since the creek catholic secular clergy couldrnarry and have children who, in turn, often became priests, many Grcekcatholic "dynasties" were formed that cultivated a certain sense of corpo-rate, if not cultural-national, Ruthenian separateness. As eiuly as in thefirst half of the nineteenth centurv, a noticeable part of Greek catholicclergy in Galicia stressed the link between Ruthenian national tradition anda distinctly "Ruthenian" confession (ruska vira). The Greek catholic ritein the mid-nineteenth century was generaily recognized as having a spe-cific "Ruthenian," "Greek Ruthenian,,' ,.Greek Slavonic,,' or ..iatholicRuthenian" character.s The church rite was the primary source of ethno-confessional identification for the masses of East Galician inhabitants.

However, it would be oversimplification to state that confessional linesclearly divided the population of Galicia into Foles, Ruthenians, Jews,Armenians, Germans and others. The polish-Ruthenian line, in particular,was often blurred. In spite of the differences in rite, the clergy and faithfulof both catholic confessions in Galicia inreracted quite intensively on an

provlnce was due to the fluctuating character of ethno-confessional identifications in thecarly I 860s. and probably to the inconsistency ofthe contemporary sraristical caliularions.

5. Eastenr Galicia was administiatively differentiated as an entity from lg4B through1867. It consisred of rwelve circles (Berezhany, chortkiv, Kolomyia, L'viv, percmyshl,.Samhir, Sanok, Stanislaviv. Stryi, Ternopil', Zhovkva. Zolochiv), and betwecn lg59 antll86l it also includcd Bukovlna.

(r. 'l-his percentage includcs small number of Armcnian Greek catholics (numberingarorrntl 2-,{xx) pcople in all Galicia). Two other largc rcligious groups, Rornan catholrcs andJeu's compriscd 2 I .44 pcrccnt and I I .25 percent respectivcly of the total calician popula-t ion. Al l othcr rcl igious groups had lcss than 1.00 pcrcent. In wcstern Galicia Romancatholics totaletl 88.71 perccnt, Jcws 6.7j pcrccnr and Greck catholics 4.04 percent. SccZrrnorski, lnfbrmutor stat))stt'czl"v do dziej|w spoleczno,gospoclarczych Galicji. LudnoitGalicji ry latat:h I 857-l 9/0, pp. 88-89.

7. .lohn-Paul [{irnka, "Thc Greek catholic church and Nation-Builciing in calicia,1172-l9lE," Ilarvanl LTtainian Studie.s g, no.3-4 il9g4\:434.

6. That is hcw lhc Caliciarr Crcck Cathol ics werc refcncd to in Varrcan lerters from ths1850s' See Athan;rsius G. welykyj oSB[4, cd., Lifiertte s.c. de propagonda Fide llccle-siam catholitan {Jkrtiinie er Brclarrusjac s:petrttnttes,vol.T: 179()-lB6j (Rorne: p. p. Basil-innr . I9 .s7 l . pp 2 : ;6 . , )6 -1 .

Canadian Americ.rn Slavic Studies/Revue Canadienne Am6ricaine d'6tudes Slaves

everyday level. Till mid-nineteenth century there were many cases of per-sonal change of rite. Most commonly, people left the Uniate Church forthe Latin one. Very often it was connected with intermarriage and changeof social position. In the middle of the 1860s, nationally-minded Rutheni-ans complained that as soon as a Ruthenian villager settles in a town hestops speaking Ruthenian and attending the ,Greek Catholic Church be-cause he sees it as incompatible with the urban way of lifee.'lhe complicated history of the Greek Catholic Church in Galicia re-sulted in its inhicate identity. As John-Paul Himka comments, "the GreekCatholic had an Orthodox face, Roman Catholic citizenship and [. . .] anenlightened Austrian soul."r0 But in fact, this "face" *or noi purely Ortho-dox. The Latinization of Eastern Christian Church rituals of the RuthenianUniates prior to the rniddle of the nineteenth century took various forms.Some innovations were normalized by the decision of the Council ofZamostia (1720), while some penetrated Uniate ritual practices later. Onthe eve of the 1860s even the outward appearance of a Uniate priest dif-fered greatly from a typical Orthodox clergyman and was almost identicalwith the Roman Catholic: he was normally beardless, abandoning specificEastern head covering fkolpalcl, and wearing the usual catholic soutarne.Several changes affected church interiors: iconostases were often madesimilar to the Latin altar decorations (for example in the main St. GeorgeL'viv Cathedral) or completely abolished, while "Latin" benches, organsand pulpits were introduced. Sung lspivanil liturgies were often replacedby much shorter and allegedly more understandable, recited [chytani]ones. There were many other important liturgical changes that sometimesinterfered with the nuances of Eastern Christian spirituality.rr

In the first half of the nineteenth century Ruthenian language seemedless irnportant as a marker of national identity than church ritual, due to as-similationist processes and polyglot practices, the spread of polish andLatin and tlen of German as the languages of administration and secularliterature. A significant part of educated Ruthenians used polish in every-day life as an indication of their superiority to the Ruthenian-speakingpeasantry, and turned to vernacular Ruthenian only for communication

9. "Dopysy. Iz mista (K podncsen'iu nashoho obriada)," S'1ovo, no. 10, Febr. 15, lg65:

10. tlimka, "The Greek Catholic church and Narion-Bukling in Galicia, lllz-tgtl,,,438 .

11. wodzinrierz osadczy, Koiciol i cerkiew na v,sp6lnej drodze. Concordia tg63. zdziej6w poronmienia miqd4t sfsq4l(iem greckol:atolickin a lacinskim w Gaticiilltschodniej (Lublin: Redakcja Wydawnicrw KUB, I 999). pp. I I 3- I 9.

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in thc I g60s

with pcasants.t' Even the Greek catholic clergy was deepry assimilatedwith the Polish culture of Galician nobility and urban dwellers.r3 Ruthe-nian literary language developed in close connection with church Sla-vonic, the sacral language of liturgy and church books in slay,ia ortho-doxa. The knowledge of literary Ruthenian was diminishing to the extentthat even the Greek catholic priests often did not master its rures.ra In gen-eral, in the first half of the nineteenth century, the existing Ruthenian liter-ary hadition was too weak, too isolated from oral culture, and still notcodified. Simplifyingly one can state that there were two separate (peasantand ecclesiastical) Ruthcnian cultures in Galicia, and an underdevelopedsecular one. cultural assimilation with the Poles was the dorninant ten-dency among educated Galicia' Ruthenians of that time. Most of themcalled themselves Ruthenian and were quite aware of being of separatechurch rite and cultural tradition. But this feeling did not lead automatr-cally to Ruthenian national aspirations. A significant part of educatedRuthenians sympathized with the Polish political cause, spoke polish, andconsidered contemporary Polish secular culture as their own.

under the impact of Romanticism in the 1820s-40s, linguistic prefer-ences of some educated Ruthenians changed in favor of the folk ldio-.Yet the issue of to what extent vemacular could be used in Ruthenian litbr-ary language remained open for many decades. A radical attempt by thefamous group of Romantic writers, Ruska Triitsia (Markian Shashkevych,Iakiv Holovats'kyi and Ivan Vahylevych), to develop a new Ruthenian lit-erature based on local vernacular was rejected as subversive by localGreek catholic authorities, and did not have wider public resonance till therevolution of 1848.

During the revolution of 1848, when the Greek catholic hierarchy, un-der the protection of imperial authonties, succeeded in mobilizing theRuthenian political movement and securing support of the East Galicianpeasants, educated Galician Ruthenians began an intensive search for ade-quate cultural backing for their national claims. Not sulprisingly the dif-

12. Anatol' Vakhnianyn, Spoml,ny z zhytia (L'viv: pccharnia Shyikovs,kola, l90g), p.37. Another educated Ruthcnian, Izydor lakymovych recallcd that as a child he communr-catcd with lris parents and relatives in potish, and that Ruthenian rvas spoken only,,withser'/:rnts, or peasants [. . .] or near the church." See /lolos na hokx dlio llulycyny ((.emivci,! 8 6 l ) , p . 2 .

13. This assirrrilation was stimulated by thc clcvation of thc cclucalional level of CreekCatholic clergy in the first half of the rrinetecnfr century, and its entrance into Galician"educatcd society" Sec l{imka, "The Greek catholic church and Nation-Building inGal ic ia , I 77 i .1918, " pp . 435-36.

i4. oleh rurii, "Nalsional'ne i politychnc polonofil'st'r'o sered hrcko-katolyts'kohodukhovenstva llaly,cfiynt pid chas revoliutsii 1848-1849 rokiv," Zapysky NTS| 2Zg (1994):1 86-8E

Canadian American Slavic Studres/Revue Canadienne Amiricaine d'6tudes Slaves

ferences between "Ruthenian" and "Polish" church rituals were seen bymany Galician Ruthenians with increasing patriotic sentiments in 1848.Discussion around the "ritualist" issues intensified again in 1851-1855, butunder the political conditions of neo-absolutism it rvds limited to a circle ofGalician bishops of both rites and mostly confined to their correspon-dence. l5

The confessional identity of the Galician Greek Catholics, like the na-tional one, was still in the making in the middle of the nineteenth century.As a llkrainian scholar, Oleh Turii comments, "the clergy and faithful ofthe Greek Catholic Church [. . .] depending on circumstances could stresstheir "Orthodox origins" or not less convincingly prove their "Catholic af-finity."16 Already in the late 1840s there were two separate groupingswithin the Church with a vacillating majonty in between. Those who fa-vored integration with the Catholic Church opposed the pro-Orthodox tn-clinations of their opponents and vice versa. Orthodox schismatic in con-temporary Catholic wording) sympathies were kept under caret'ul surveil-lance of Church authorities and sometimes scornfully revealed. The "Lati-

nization" of the Greek Catholic Church in turn met with the disapproval ofa sigrrificant part of Ruthenian clergy who stressed the pre-Uniate historyand statutes of their Church. With the beginning of the age of nationalism,the argumentation of both sides became increasingly nationally charged:the opposing sides accused each other of pro-Russian or pro-Polish ten-dencies.

The vague confessional identification of Galician Ruthenians corre-sponded to the vague understanding of the meaning of Rus' as a historicalconcept. For many it stressed the pre-Polish historical past of Galicia, andits membership in the historical tradition of Kyivan and later Galician-Volhynian Rus' principalities (tenth-fourteenth centuries)-. Yet the under-standing of Rus' remained indefinite in regard to whether it included otherEastem Slavs that claimed Kyivan Rus' heritage as their own, namely"Muscovites" (the ancestors of present-day Russians). This ambivalencewas one of the reasons for the changing instability of national identifrca-tion of the Ruthenian inhabitants of Eastern Galicia. The traditionalethnonymes "Rus"' or "Little Rus"' ("Little Russia") could be interpretedin various ways and did not contain a clear answer to the question ofRuthenian national identity.

15. Wodzimiez- Osadczy, Koiciol i cerkiew na wsp6lnej drodze. Concordia 1863. Zdziej6v,porozunienia miqdzv obrzqdkiem greckokatolickim a lacinskim w CalicjiLl/s chod niej, pp. I 05-06.

16. Oleh Turii, "Konfesiino-obriadoryi chynnyk u natsional'nii samoidentyfikatsiiukraintsiv Halychyny v seredyni XIX stolittia," Zapyslq: NTSU233 (1997):14.

Emerging Cult of Taras Shevchenko in Austrian Fastem Galicia in the 1860s

During the period of "constitutional experiments" in Austria (1860-1867), the national activities in Galicia acquired public forms for the sec-ond time, and Ruthenian intelligentsia more clearly split into Old Ruthe-nian, Russophile and tlkrainophile groupings. It was caused by the factthat the emerging public sphere provided new venues for debate over thequestion of national ideutity, and new possibilities to reformulate and re-codifo existing traditions appeared. Along with the Polish, somc newRuthenian newspapers and journals were founded in the early 1860s. TheRuthenian press of the 1 860s did not conoentrate so much on informing thepublic about the most recent news, rather it provided educated Ruthenianswith a possibility to debate issues related to their nationality.

Almost all Galician Ruthenian periodicals began their opening editorialswith the question "what nation are we?" The responses varied. Tradition-ally, the fecling of affinity with a pre-modern Rus' culture that derivedfrom the cultural heritage of Kyivan R.us' and Galician-Volhynian Rus'was typical for those educated Ruthenian clerical elites that rejected as-similation to the Polish culture. In the early 1860s also the tlkrainian Cos-sackophilism began to dominate the public moods. At the same tirne, mostof the patriotic eclucated Ruthenians for various reasons felt loyalty toCatholic Church and imperial dynasty. They thus had to adjust Rutheniancultural affinity with a pro-Catholic and Habsburg imperial-religiousstance. Those, whose sense of Catholic and Habsburg loyalty dominatedover Ruthenian cuitural affinity, manifested their views in semi-officialand conservative Viennese Vistnyk. The definition of Paul Robed Magocsiof Old Ruthenians as of those "whose national, political, and religious loy-alties did not extend beyond the boundaries of the Austrian Empire" ap-plies to this group.tT Those who, in spite of political and ecclesiastical bor-ders, felt stronger affiliation with a pre-modem Ruthenian (or rather EastSlavic) culture that derived from the cultural heritage of Kyivan Rus' andGalician-Volhynian Rus', turned mostly to the more liberal L'viv-basedby-weekly Slovo that since January 1861 became the leading Ruthenianpolitical periodical" The latter attitudcs rnay lead to more definite Ukraino-phile (stressing tlkrainian/Little Russian separateness fron all neighbors)or Russophile (stressing cultrral relatedness of all branches of Rus') iden-tities. 'I'herefore, in the beginning SYr.ruo had an ambivalent character. Theposition of early Llkrainophrles in the Galician public debates in the hrsthalf of the 1860s was also articuiated through their own periodical joumalsVechern-vtsi (1862-1863) and Meta (1863-1865). Yet, the main line of dis-

17. Paul Robcrt Nlagocsi, "Old Ruthenianism and Russophilism: A New ConceplualFramcwork for nnalyzing National Ideologics in Late-Nirretecnth-Certury EastcrnGalicia," in Ejustl. The Raols of (.tkrainian i',latioialism: Galicia as {,tkraine'.s Piednont(Toronto: LJn:v. *i"I'oronto Prcss, 2Ct02). p. 105.

28 Canadian American Slavic StudieslRevue Clanadienne Amdricaine d'6tudes Slaves

cussion in l86l-63 was not between S/ovo and the likrainophile press, butinstead between Vistnyk and Slovo. Only later. over the course of time,more and more contributors to S/ovo opposed the views of the lftraino-philes, and it became the main organ of Galician Rus'sophilism.

Besides constitutional reforms, the growth of the contacts wlth Ukrain-ian and later also Russian pan-Slavist activis$ fiom the Romanov Empirewas another factor that stimulated shaping of competing Ukrainophile andRussophile trends. In the first half of the nineteenth century only the maincultural figures of Galician Ruthenian revival were informed about themodern Ukrainian and Russian literatures to a some extent.r8 Aft,er 1848,there were first attempts to re-publish the literary works of Ukrainian writ-ers, Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko and Ivan Kotliarevs'kyi in Galicia, yetthey still were read in narrow circles of patriotic friends. At that time onlya small circle of people personally connected with the first Galician-Ruthenian "awakeners" had read Taras Shevchenko's poetry.re (ln theearly 1860s there was real influx of tlkrainian publications from the Rus-sian Empire into Austrian Galicia.)

Regular transfer of Ukrainian literary works into Galicia was estab-lished in the 1860s. As is well known, in the spring of 1862, MykhailoDymet, a Ruthenian merchant from L'viv, carried a parcel of books on hisway back from Kyiv with 1860 St. Petersburg Platon Symyrenko's editionofTaras Shevchenko's Kobzar, and quickly sold them all. The book-tradesuddenly proved to be profitable for Dymet, thus during the next years hebrought more and more poems of Shevchenko from the Russian Empire.All of them met with a tremendous interest and enthusiasm from a signifi-cant part of Galician Ruthenian students.2o Together with the taste for Eastllkrainian literary production many of them developed admiration of theCossack past and interest in the llkrainian national movement. In 1862-1864 they formed a network of semi-secret circles under the name of hro-

18. Mykhailo Vozniak, "Pohliad na kul'turnoliteratumi znosyny halyts'koi tlkrainy tarosi is 'koi vI pol. XIX v.," Nedil ia, no.43-44 ( l9l l ) : 3-10.

19. Kyrylo Studyns'kyi could number only fivc Galician Ruthenians who, as heassumcd, knew Shevchenko's verscs well enough belore t86l Kyrylo Studyns'kyi,,Doistorii vzaiemyn Halychyny z Ukrainoiu v n. I 860- I 87 3, Ukraina 27 , no. 2 (1928): I 3). Seealso Bohdan Zahaikerych, "Kul't Shevchenka v Halychyni do Pershoi svitovoi viiny,"Zapysky NTSL 176 (1962): 2541' M. I. Dubyna, Za pravdu slova Shevchenka. Ideologichnaborot'ba navkolo spadshchyny T.H. Shevchenka v Zukltidnii Ukraini (1812-1939) (Kytv:Vyshcha shkola, I 989), pp. 7- I 1 .

20. Iaroslav Hordyns'kyi, Do istorii kulturnaho i politychnoho zhyttia v Halycftyni u 69-tyh rr. XIXv. (L'viv: NTSh, i9l7), pp.4043.

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Fastem Galicia in the I 860s

mada (hrornady in plural, which can be literary translated as "community"

or village commune) across Eastern Galicia.2rSome contemporaries and scholars attributed the interest in Shevchenko

exclusively to the import of Kobzor flom the Russian-ruled Ukraine. Infact, the greatest.ukrainian poet's cult was introduced into Galicia evenbefore Dymet's merchandise arrived in Galicia. Galician-Ruthenian peri-odicals spread information on Shevchenko a year before his texts actuallyreached the readers. In 1861 S/oyo commented several times on the deathof Shevchenko. In these articles Shevchenko was praised as the greatest"prophet, artist and bard-nightingale" of Little Russia whose truly Ruthe-nian heart (shchyro-ruslaila hrud') was full of love for the steppes of'hisnative Ukraine.2' Slovo also stated the L'viv Ruthenians sympathized withthis great loss of [Jkraine.23 Another obituary, written by Volodymyr Ber-natovych, an llkrainophile activist from Right-Bank Ukraine, was pub-lished in July 1861. Bernatovych's article, with information onShevchenko's funeral and funeral speeches, was representative of thepopulist rhetoric on Shevchenko already developed in Russian-ruledUkraine. tsematovych emphasized the poet's deep devotion to his nativeukraine' and his martyrdom. The relationship of Kyiv students withShevchenko tvas characterized as similar to that between children and theirfather. This reference to Shevchenko as "our father" fbat'ko)became a re-current expression in the letters "from llkraine" published in ,S/ovo andwas soon accepted by the Galician Ukrainophiles.

All this was quite new for the Galician Ruthenian educated public, whofelt the need to "discover" and honor the poet so significant for the "Little

Russians". Already on the first anniversary of Shevchenko's death in earlyMarch 1862, before Dymet made his famous trip to Kyiv, the first requiemmass for Shevchenko was organized in L'viv. This event had tremendouspublic resonance. Thus, the birth of the cult of Shevchenko, which soonbecame a crucial element of Galician Ukrainophilism, was stimulated by,amongst other factors, the changes in Ruthenian Greek Catholic religioussphere and its wider opening to the East. This process will be discussed inthe following paragraphs.

Before bcing overwhelmed with secular Ukrainian litcrary production, asignificant part of Ruthenian educateci elite tumed to their own church-based cultural tradiiion, and attempted to imbue tradittonal religious prac-

21. On thc eatly hronrudy network in l,:aslern Galicia and theilinitiational function inshaping sacnficd sense ofnationality arnong Ruthcnian studcnts, see my articlc "Hromady

rannikh narodor,lsiv u Skhidr,ii Halychyri (60-ti roky XIX st.)," published in (tkramt:kul'turnaspi:tlsirth1,a6, nalsional'nu st'idomist', tlezhav,nisl'9 (2001): 178-92.

22 . S lavo , no . 15 , March 15 , 1851.2-j ."V. sponrv, rka o Shevchenku," Slavo, na. 27, May I l, l 86 l : l -5o.

Canadian American Slavic Studies/Revue Canadienne Amdricaine d'6tudes Slaves

tices with an ideological and national meaning. Attention to the rituals andto the clerical sphere in general was quite obvious since it was an impor-tant part of the spiritual and intellectual life of all educated GalicianRuthenians. Since 1861 the differences betwecn "Litin" and "Ruthenian"

Church rituals were brought to the fore of public attention by the editors ofS/ovo. Within two years, S/ovo managed to cambine the patriotic feelingsand anti-Catholic sentiments of some Greek Catholics, mostly parochialclergy and lay intelligentsia, into a visible public movement. For manyGreek Catholic priests, who did not think in modem national terms, theRuthenian identity was based upon the extemals of the religion, and theyexpressed it by defending their ntual tradition. However, this "tradition"

had to be re-invented and in many aspects it contradicted with the "real"

tradition expressed by everyday church practices. Such issues as kneelingand ringing small bells during the liturgy, the use of a sponge for chalice,adding hot water for the Eucharist. the use of side altars, the priestlyclothes and beards were at the center of the Ruthenian public debate. Vari-ous Greek Catholic Church practices, particularly processions connectedwith Julian religious holidays, were increasingly seen as "Ruthenian na-tional" manifestations.2o

The articles published in Slo"-o by two leading figures in the ritual-purification movement, Fathers Vladymyr Terlecki and Ioann Naumovych,provided the ritual-purification movement with the concepts that owedmuch from national and Romantic thinking. A lengthy piece by FatherTerlecki25 entitled "something about the Ruthenian nationality" was pub-lished in Slovo in April-July of 1861. It endowed the ritual-purificationmovement with a universal mission. The author argued that full preserva-tion of Orthodox liturgy and ritual culture by the Uniates would convinceother Orthodox Slavic nations that it was possible to preserve church ritualand Slavic culture while being part of the Catholtc Church. The mission ofRus' and padicularly of the Ruthenian Uniates (because of their providen-tial location in the center of the Slavic world) was to restore church unityand convince the Orthodox Slavs to accept a union with Rome. Terlecki

24. See, e.g.. the dcscriptions ofthc Thcophany (Bohoiavlewria) processions and ritualsirr L'viv and Peremyshl ' in 1862: Vistnyk, no. 4, Jan. 25. 1862: 14. The tradit ion ofpubl icRohoiavlennia procession in L'viv was rntem-rpted in the mid-l8th century and then rc-newed in 1789 by the Grcek Cathol ic Bishop of L'r ' iv Petro Bi l ians'kyi. Yet the scrmonsdelivered there and its descriptions werc done in Polish. Vasyl' Shchurat, "lordan u L'vovi1789r . . " Ned i l ia3 (1911) : l -2 .

25. On his colourful personaliry sec lvan L. Rudnytsky, "Hipolit Vladimir Tcrlecki," inIvan L. Rudnl.tsky, Esscl,s in Modern Ilkrainian Iksto4 (Edmonlon: Canadian Institute ofLlkrainian Studies. l9E7), pp. l-13-72; antl Ostap Scrcda, "Aeni.o,na ontbulans: o Volo-dymyr (lppolyt) 'l'erlets'kyi i 'rus'ka narodna ideia' u Halychyni u (rO-kh rokakh XIX st.,"{Jkraina modema 4-5 (2000): 8l-104.

Emerging Cult of Taras Shevchenko in Austrian F.astem Galicia in rhe 1860s

rvrote in quite a liberal spint. greeting the democratization of the HabsburgMonarchy and the introduction of liberal freedoms there. He argued thatreligious culture was an inevitable part of national culture, and since onlysimple Rutheuian people preserved the spiritual virtucs of Slavdom, theirchurch ritual was of great cultural imporlance.26

Father Naumovych in an article "About the things basic for Rus"' statedthat the "Greek ritual" was irnportant for Catholic Church aspirations touniversaiity and therefore, should be preserved in purity and in accordancervith the original spint of Byzantine liturgy. He argued that undcr the thencurrent state of affairs, a non-educated faithful copied rituals withoutdeeper thought, though these rituals v'ere corrupted by Latin influencesand deprived of their initial meaning. To avoid this situation andstrengthen the belief and morality of the "simple people," the extemal sideof Greek Catholic liturgy should be restored in accordance with EastemChristian spiritual religiosity. I{is argumentation was also heavily imbuedwith Ruthenian national patriotism. The Latin admixtures in the UniateChurch were explained as the result of a conscious Polish policy of assimi-lation and oppression against the Ruthenians.2T

The Polish press actively responded to what was called the schismaticagitation. The ritual-purification activists, who as a rule contributed arti-cles in Ruthenian to Slovo, were opposed mostly by the Greek Catholicpriests who wrote in Polish to the Polish press (Tygodnik Katolicki, Dzien-nik Polski, Gazeta Narodowa). Thus, the "ritualist" discussion obtained aPolish-Ruthenian character. While the ritual-purifrcation activists pictureda return to a more Eastern form of liturgy as a liberation from Polishdomination and assinilation, their opponents argued that if all ritual dif-f"erences between Greek Catholics and the Orthodox would be eradicated,ttren Ruthenians of Galicia could easily be persuadcd by Russian Orthodoxagitators. They argued that ntual changes had preceded the abolition oflJniate Church in the Russian monarchy, and warned about the "terrible

consequcnces" that the purification of ritual could lead to. The anti-"rituaiists" did not value Eastem Christian spirituality highly (the tJniateClhurch was seen as progressing from thc backward schismatism to thecivilizcd state of the West) and argued that exaggerated attention to the ex-ternals of the religion, some of u'hich were allegedly incompatible with thenrodern hygienic standards, undcrplayed the more important aspects oftheology. Discussion also touched upon such matters as the character of

26. Vladymyr Terletskyi, "Dc-ncshcho o ruskoi narodnosti," ,llovo, no.24, April 27.l 8 6 l : l - 2 : n o . 2 5 , M a y l , l 8 6 l : 1 3 7 ; n o . 3 7 , J u n e 1 5 , 1 8 6 1 : 2 1 2 - 1 5 ; n o . 4 0 , J u n e 2 9 , l 8 6 l :2 3 3 ; n o . 4 l , J u l y 3 , I 3 6 l : 2 4 0 ; n o . 4 2 , J u l y 5 , 1 8 6 1 : 2 4 3 4 4 ; n o . 4 3 , J u l y I 0 , l 8 6 l : 2 4 9 - 5 0 .

2'7. lvan Naumorych, "O di lakh dl ia Rusi osnovnykh,".9/oyo, no. 69, Oct. 9, l86l: 357-5 8 : n o . 7 0 , O c L 1 2 , l 8 6 l : 3 6 1 ; n o . 7 l , O c t . l ( r . 1 8 ( r 1 : 3 6 5 - 6 7 .

C'anadian Amerirzn Slavic StudiesiRevue (--anadienne Amdiicaine d'etudes Slavcs

Catholicism, its pluralism and relationship to the Orthodox Church. Bothsides based their arguments on the works of renowned Catholic writers:the "ntualists" used the ideas of Russian Catholics, rvho at that time hadestablishetl contacts with the Galician Greek Catholics,28 parlicularlyPrince lvan Gagarin, their opponents the anti-Orlhodox rhstoric of deMaistre.2n

'l'hose criticizing ntual-purification reforms did not hide their Polono-

phile sentiments and accused "ritualists" of provoking anti-Polish hatred,which was alien to the ideal of Christian brotherly love. In the political at-rnosphere of the early 1860s, inflarned by the Polish patriotic demonstra-tions in Warsaw that often had religious character, loyalty to the RornanCatholic Church was easily conflated with support of the Polish cause.

There were also many Greek Catholic priests who saw the main instru-ment of promoting their interests in stubborn loyalty to Vienna and Romeand who were fearful of loosing their reputation of the "Tyrolians of theEast." They may have sympathized with the ritual-purification cause butsuspected that the whole issue was provoked by the Polish side that wantedto compromise Ruthenians as schismatics in the eyes of Austrian govern-

ment and Rome.3n The semi-ofhcial Viennese Ytstnyk adopted a differentperspective from S/ovo. Its authors always stressed loyalty to the dynastyand the Catholic Church. The attitude to the "ritualism" of the higher hier-archy of the Greek Catholic Church was also ambivalent.3r MetropolitanHryhorii Iakhymovych attempted to keep ritual-purification agitation un-der control; he therefore disciplined Father Naumovych in February1862,32 and removed Father Terlecki from L'viv to a remote Hoshiv mon-

2E. In l86l , Father Ivan Martynov v'isited Metropolitan l{ryhorii Iakhymovych and dis-cussed the possibility oferecting a Russian Catholic Jesuit Church in l-'viv. Bohdan Didyt-skyi, Svoezhytticvj,v zapysk.v", vol. I (1,'viv: Pechatnia Stavropigiiskoho instituta, 1908), p.

29. Scc most manifest cxanrplcs ofthe r i tual ist discussion from l86l-1862 published in

[Jan l]oliriski], ed.0 obrzqduch grecko-unickichjako kwesty'i czas6w dzisiejszl'cl1 w (iali-

c.vi Ll/schodniei (l-rv<iw: Druk. Zakladu Narodowe go im. Ossolinskich, 1862).30, "Prymichaniia o otnosheniiakh l{alyskoi Rusy k Rymovy," Slovo, no. 19, March

1 9 . 1 8 7 0 : 2 .31. Sonrc ol thc Poiish Galician pol i t ic ians had no doubts that Metropol i tan lakhy-

nror,rych "considcrs the only redemptiou for Rus' in Russia, sccrctly pron.)otes sthyzra anJmost likely is paid by Nloscow" (Bibliotcka Czartoryskich, manuscript division. rlps. 5688lll, str. (>77). Father Terlecki claimcd that Mctropolitan gladly received him in L'viv butwas not sure whethcr ritual can be really changcd back to its original purity. L'vivs'kaNaukova tsiblioteka im. V. Stefanyka NAN Llkrainy, rnanuscript division,pnrl | (Naukovetovarystvo itn. T. Shevchenka) opys l. od.zb,438/10, ark. 1 zr,. (V. Terletskyi to I. Leslr-chyns 'ky i . Sept . 12 . 1862) .

32. Kyrylo Studyns'kyi, Z pozhovklykh l),stkiv (Zamitxt\ i studii) (L'viv: Drukornia A.Coldmana. l9 I 7). pp. 28-4 I .

Emerging Cult of Taras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in the 1860s 3 3

astery in May of the same year. In January 1862, Metropolitan HryhoriiIakhymovych issued a pastoral letter in which he prohibited self-willedchanges in the ritual but at the same time promised to conven€ a churchSobor that would establish the principles of ntual reform and present themto the Vatican.'3 These plans, if implemented, might have resulted in thepreviously unseen national forum of Galician Ruthenians, similar to that

held already by other clergy-led nationalities in the empire such as the

Romanians and Serbs. The Metropolitan suddenly passed away on April

29,1863, his death slowing dorvn the ritual-purifrcation movement. Also,

the Vatican became more involved in resolving the confessional tensionsin Galicia (among other measures it reprimanded Father Terlecki several

times) and stimulated Polish-Ruthenian rapprochement on the question of

personal changes ofthe church rite.3awere the early lJkrainophiles in any way involved into the "ritualist"

debate? ln fact, for a while, this issue also obtained primary significancefor them. Those who formed the ukrainophile hromady were among the

most sympathetic supporters of the ritual-purification movement. At this

time they viewed Orthodoxy as the faith of their fathers, for which Cos-

sacks fought with the Poles.35 At a later stage, several Ukrainophiles spokefavorably about the ritual purification ofthe 186cs as ajustified undedak-

ing.36 This was underlined already by several contemporaries and later by

scholars. Ostap Terlets'kyi, an active participant in the tlkrainophilemovement of the 1850s, commented that due to the paramount position of

clergy among the educated Ruthenians, church issues played a major role

in all Galician-Ruthenian endeavors, and thus "all educated Rus"' [aslapys'menna Ras'] were engaged in the purification of the church ritual.''The Pre-Soviet Ukrainian scholar Iaroslav Hordyns'kyi, although criticalof the "ritualists" as potential Russophiles, acknowledged on the basis ofthe correspondence that young tlkrainophiles supported leading "ritual-

ists" as national patriots.38 Another tlkrainian scholar of pre-soviet epoch,Kyrylo Studyns'kyi noticed that no other issue managed to unite people so

3-t. [.l.rn Bolinski], ed., O obnqdach grecko-unickichiako kwestyi czas6w dzisieiszych w

Gulicyi WtchodnreT, pp. 88-95.J:l. See lctters of the Vatican Congcgalion de Propaganda Filie fron 1860-1862 pub-

lishccl in P. Athanasius G. Welykf OSBM, ed., Litterae S.C. de Propaganda f;ide ficcle-

sit,'n r:atholicam Llkrainae et Bielarusjae spectanles, vol. VII: I 790- I 862, pp. 3ll-12, 317'

I t 322-325,321--123-s. "Hadky." [ 'cchernytsi, no. 18, May 31, 1862: 141.36. Anatol' Vakhnianyn, Spomyny z zhl'tla, p. 5}.37. Ostap Tcl icts'kyi, "Halyts'ko-rus'ke pys'menstvo 1848-1865 r. iJvahy ispornyny,"

!, it e ra I u r t i * i'i ; : ),. ko v r- i l/ i st ny k 241 I 1 ( I 903 ) : 85 - 36.lJ8. hinslav i{rrtl5,ns'ky.i, Do istorii kul'turp.oho i politychnoln zhytia v }luly:hyni u 6C-

tr^iih rr.,Y!,Y v., p, f 5.

Canadian Ameriqrn Slavic Studies/Revue Canadienne Amdricaine d'6tudes Slaves

different by age and national views as the ritualist one. Old and young,Russophiles and Ukrainians removed the small bells from the churches,did not kneel down, curtained the Royal Doors at the minute of the trans-formation of bread and wine into the Christ's body and blood, receivedcommunion standing with crossed hands (instead of kneeling), and dis-puted with Poles on the ritualist subjects.3e

The young generation even wanted to be more consistent in conf'es-sional issuc than majority of Greek Catholic priests. Ostap Terlets'kyi re-called later that the young people did not pay attention to church traditionsand convictions of contemporary Galician clergy, that were Uniate to thecore, but considered the issue from a patriotic position, and from this posi-tion they raised the question: why shall not we take consequences that areoffered by history to a Ruthenian patriot, and try resolutely to free theRuthenian people from the Polish influence, why do not we leave all theUnion and come back to Orthodox religion?40

In a letter of "young Galicians" to "brothers-Ukrainians," published inSlovo, the "ritualist question" was described as the most important issue incontemporary Galicia, and supported by all young Ruthenians.at Both Fa-thers Terlecki and Naumovych, proscribed to that or another extent by thechurch hierarchy, were highly respected at that moment in the GalicianUkrainophile circles as devoted Ruthenian pakiots. In a public letter writ-ten by 40 Ruthenian universify lay students, Naumovych was called "fa-

ther" lbat'ko] and praised for "purification of our fatherly Greek Catholicfaith from the foreign to our Ruthenian spirit, and alien to the developmentof Ruthenian nationality harmful influences." The letter was published inSlovo at a time when the Metropolitan Hryhorii Iakhymovych disciplinedFather Naumovych.o' In February 1863, the llkrainophiles petitioned theMetropolitan to let Father Terlecki stay in Galicia after the Austrian gov-ernment requested his dismissal.a3

Ruthenian patriotically-minded students considered a public demonstra-tion of sympathy with the Orthodox Church as an indicator of individualfreedom. Future Ukrainophile and Greek Catholic priest, Emanuil Ly-

39. Kyrylo Studyns'kyi, Z pozhovkl),kh l1'tkiv. p.28.40. Ostap Tcrlets'kyi, "Haly'ts'ko-rus'ke pys'menstvo 1848-1865 r. Uvahy i spomyny,"

Lite ratu rno- naukovlt i Ttislnr' 1, 24l I I ( t 903): 80.41. "Molodiy Halychanc. De-shcho na otvit bratiam ukrayntsiam," S/ovn, no. 70, Sept.

l ' l ,1862:277.42. "Prepodobnomu Ottsu Yvanovy Naumovychu, Prykhodnyku Korostna y Pcre-

mfshlian," Sloyo,no.6, Jan. 20, 1862:22. 'Ihis supJnrt for FatherNaumovych clearly con-

trasted with the critical attitude ofthe Ukrainophile studens ofthe 1870s also expresed ina public letter. See "Otvetryi lyst ruskykh akademykiv do ortsia Naurnovycha, rydavatelia'Nauky'," Pravda, no. 2, Febr. 27, 1873:89-92.

43. " 'Moloda Rus'v rokakh 1860-66," Dtlo,no.29" i .ebr. 18. 1892: l-2.

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in the I g60s

synets'kyi recalled later that in 1862 Ruthenian gyrnnasium students ofL'viv were inspired by the articles of Naumovych in s/ovo. Before ..theyear of ritualism" (rik obriadovshchyny) the only orthodox church inL'viv that belonged to Bukovynian bishopric was seen as a ..Greek" one.The church was normally attended only by the soldiers from Bukovynawho were stationed in L'viv. suddenly, gymnasium^students discoveredthat church service was, besides in Romanian, arso in Ruthenian, due tothe initiative of local priest, Father Kharanevych. From then on, they fre-quented these orthodox services and enjoyed "the punty of the liturgy ofthe Eastern church." Father Kharanevych was married to the daughter of aGerman official from Bukovlma, Leopoldine Laterne, and conversed withher in German. However, as soon as his church became the focus ofRuthenian national interest, he "acquired Ruthenian patriotism," andchanged his coltoquial language. The admiration of the students grewwhen in 1862 Father Kharanelych celebrated his first requiem mass inhonor of Taras Shevchenko.{

At that time the church requiem was used as a public national manifes-tation: for example, in r 862 such a mass was organized in honor of theGalician Ruthenian historian Denys Zubryts'kyi.as But Shevchenko wasorthodox, and it provoked a public scandal. The fact that patriotic gather-ings of the Ruthenian public took place in the orthodox Church was dis-reputable in the eyes of conservative Greek catholics and poles,a6 but at-hacted all those who supported the ritual-purification movement. The req-uiem mass was numerously attended by many gymnasium and universitystudents, a few dozen ladies and several prominent Ruthenians. some hadnot heard of shevchenko until the moment when the posters with the three-barrow "orthodox" cross announcing the event were posted across the city(see Illustration l). some attended the requiem service for the sake ofsympathy with the orthodox church.aT Father Emanuil Lysynets'kyi, who

44. Vesyl' Shchurat, "S'viatkovanie rokovyn smerty Shevchenka v Halychy,ni (1g62-

1870)zi spc'nrynamy o. E. Lysynets'koho i st. rad. T. Revakovycha," Nediria n -tz (tcit),1 0 .

45. l4sinyk,no. 10, Febr. 13, lg62:3g.45. hr 1863 the Polish Gazeta Narodown qualifietl this,tequiem in schizmatic L,viv

church" as one ofthe rnain anti-polish aclions organized by Ruihenians. lt was especiallyalarrrred by thc "young Rus"'attraction to the schismatic rituar. Ksi4dz otrzqdkuriirwianskiego, "lidzieniem w sprawach naszych domowych," cazeta Narotrowa, no. 40,lvlarch 31, 1863: l-2.

47. on the synrbolic importance that ahe three-barrow crosses, commonly associatedrvith orthodoxy. i;cquirctl in Galicia in thi no:1 dccade, see John-paul Hirka, Retigion a^dNationalii; lii ii|ilen'! Likraine: The GreLii C. tholic church and the Rurhe:nian"NationatMctvemeri;n t idi tciu. 1867-rga7 (Mo:i ireai. McGil l-eueen's Univ. press, 1999), pp.6a-67. {iii 'i,,::,;}';icl:, i'1xlouncing Sher.chenkc's first requiem service, s,,e lv:rn verkirras,kv,.

Canadian American Slavic Studies/Revue Canadienne Am6ricaine d'dtudes Slaves

in 1862 was a glmnasizz student in L'viv, recalled later that because ofthe general favorable attitude to the ntual-purification issue, the requiem

service in the Orthodox Church for Shevchenko announced through theposters attracted "[. . .] many devout Uniates, young and old Ruthenians.At this time Rus' ftom Narodnyi Dim lmain national institutionl honoredShevchenko differently [than now]. Old Zubryts'kyi just passed away at

this moment, otherwise he .arould follow all others. All lay Ruthenians asmany them were in L'viv, without few officials and professors, with devo-tion (not formally) listened to the church seryice."o8

The excited contributor to Slovo (probably Volodymyr Shashkevych'one of the intellectual leaders of early tlkrainophilism in Galicia and son

of Markian Shashkevychae) called this first Shevchenko's requiem servicethe beginning of a "New Era" that would succeed the previous "Dark

Age." He proudly stated that numerous participants showed that they"were not afraid to pray for Orthodox Taras in an Orthodox church," andproved that they have a "true Little Russian heart."so For a moment lllaai-nophilism merged with the ritual-purification mood of Ruthenian activ-ists.5l

Those Greek Catholic priests who objected to the ritual-purification re-forms ssornfully criticized the requiem masses for Shevchenko. They ar-gued that such a public manifestation of sympathy for the "schismatic lit-urgy" gives reason to suspect the participants of sympathy with Orthodoxreligious principles. Valuing the confessional sense of identity over the na-tional, they argued that the Catholics could not pray for Shevchenko since

"Perve pomynal'ne bohosluzhenie za upokoi Tarasa Shevchenka 1862 roku u L'vovi,"

Zapysky N75'n 108 (1912):145-41.48. Vasyl' Shchurat, "S'viatkovanie rokovyn smerty Shevchenka v Halychyni (1862-

1970\ z.i spomlnamy o. E.Lysynets'koho i st. rad. T.Revakovycha," Nedilia 1l-12 (1911):

6.49. Kyrylo Studyns'kf, "Do istorii vzaianyn Halychyry z Ukrainoiu v n. 1860-1873,"

p . 18 .50. "Pomynky Tarasa Shevchenk a," Slovo, no. 17, March 1 2, I 862: 68.

5l . It'is interesting how in this light the first Shevchenko's requiem mass was perceived

by some of the participants, for cxample by Zenovii Zaval'nyts'kyi, the church singer from

Perernyshliany, a small town ncar L'viv wherc Ivan Naumovych served as local priest. in a

letter to S'/ovo, prompted probabiy by Naumorrych, hc acknowledged that before he had no

idea that Shcvchenko already "sang Ruthenian sougs lor the glory ofour poor Ruthenian

nation [spivav rusky pisnS, no slavu nashoho bidnohtt ruskolrc narodal." He'read somc in-

lormation about him and the planned rcquiem mass in this newspaper. However, the

lengthy articlc was devoted not 1o Shcvchenko's poetry, but to irnprcssions ofthe Orthodox

Church service, and was obviously used as an opp.:rlunitv to describe it publicly in detail.

Zaval'nyts'kyi tried lo convince Slovo readets that tlte Cllhodox C'hurch was also a Ruthe-

nian Church with Ruthenian icons and Ruthenian pricst. Sec -S;ovr.r, no. 18, March 15, I 862:'t2.

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Calicia in the I 860s

he did not belong to the Catholic Church, and there is no spiritual connec-tion with him.52 Also, most conservative Old Ruthenians were afraid ofloosing their loyalist reputation.t' Their views were often expressed inVistnyk that also debated with tlkrainophiles on the wide range of culturaland political issues. Among other things, contributors to Vistnyk attemptedto preserve their control over the development of Ruthenian language inGalicia and to ignore the national-political message of Shevchenko. Thus,those who participated in the Shevchenko's requiem masses clearly feltthat they were transgressing established cultural borders and consideredthe attendance of the Orthodox Church as an act of civic courage.tu

Some of Galician {.Ikrainophiles did not want to obey the restrictions ofCatholic Church authorities and still tned to make Uniate priests andmonks pray for him. Interestingly enough, in 1861, just after S/ovo pub-lished first information on his death, somebody wrote his name in the me-morial book of the monastery in Pidhirtsi.ss One of the Ukrainophiles re-called that thc gymnasiarn students in Stanislaviv often ordered GreekCatholic requiem service for "father Taras" pretending he was the real fa-ther of one of them.56

Galician Ukrainophiles also began to include readings of Shevchenko'spoetry into the public "declamational evenings" organized since 1862 by anewly founded Ruthenian social club in L'viv, Ruska Besida. Normallysuch evanings combined the elements of Austrian loyalty, local GalicianRuthenian patriotism and an interest in Cossack Llkraine. For example, theevening on February 26,1862. held on the first anniversary of the Febru-ary Patent, was opened by the speech of gymnasiun professor MaksymIskryts'kyi who thanked the emperor for freedom and constitution, fol-lowed by a choir singing the Austrian anthem. During the artistic part,gymnasium professor Oleksii Torons'kyi recited a poem of the GalicianRuthenian poet Antin Mohyl'nyts'kyi Slq)t Maniavs'leyi, another g)mna-siazr professor Ievhen Zhars'kyi delivered a shod lecture on Ukrainianwriter Kvitka-Osnovianenko, prominent tlkrainophile publicist KsenofontKlymkovylch recited Shevchenko's Ivan Pidkova, and a certain Kul-chyts'kyi recited Cossack histoncal duma on Samilo Kishka. Poems by lo-cal l,rkrainophile authors, Volodymyr Shashkevych and Iurii Fed'kovych,

:t2. Uan Bolitiskif" O obrzqdach grecko-unickic:h jako kwestyi czasitw dzisiejs4,ch w,; )r!ir.li t'Yschodniry, pp. 98-99,

53. In*nS,k. no. i9. March 21,1862:74-'15.54. "Moloria Rir'," Drlo, no. 29, Febr. ! 8. 1892: I -2.

-55. V. Iiishc!:rns'kyi, "Vasyliany vymoli'.riut' dlia Shevchenka rai," Vysolqti Zannk.March E, : !11)2.

56. \'ii.:i,'i i,;trvkevt'ch, Isit:,nia kul 'tit Shet'rlienka seritd gitnnazuial'noi ;nolodizhy( P r : ' . ' . : i i h l ' , t r . i r . r . X { - i \ .

38 Canadian American Slavic Studies/RevueCanadienneAmeiicained'6tudes Slaves

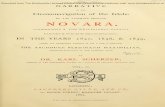

were also read.57 Smaller declamational evenings were held in some pro-vincial towns of Eastern Galicia with the participation of both ..old', and"young" Rus'.58 However, attempts to hold a commemorative evenrng onthe day of shevchenko's death were blocked since lg63 by the directors ofBesida who were afraid that it would be perceived as the second, civic partof an orthodox requiem mass. The refusal of the directo rs of Ruska Besiclacaused the first open public manifestation of ukrainophiles against the"old Rus'." The former decided to boycott the following declamationalevenings in Besida in protest.se Accordingly, in lg63 the directors ofRu.ska Besida decided to remove Shevchenko's portrait from the walls ofthe institution that were also the walls of Ruthenian Narodnyi Dim. rtturned into a public scandal and was heated by ukrainophiles as a sign ofopen discord with the "old Rus'."60 Interestingly enough, the caricaturist ofthe viennese Ruthenian satirical journal strakhopud still saw this conflictin terms of the ritual-purification struggle (see Illustration 2). For him,shevchenko was removed from Besidu as a schyzmatyk, in spite of hisfame in the whole Rus'.6r

Until the mid-1860s the orthodox requiem services for Shevchenko,regulaily organized in L'viv on the anniversary of his death, were the mainpublic form of manifesting admiration of the poet. They turned into anewly-established tradition and important patriotic event for many edu-cated Galician Ruthenians irrespective of national preferences, old h.uthe-nians and Russophiles included. within a couple of years, a special ritualemerged according to which the Ruthenian public celebrated ih" m"-oryof shevchenko. It followed the basic rules of the Eastem christian ntualand some folk customs, however there were some essential additions. Thetetrapod was decorated with the lithographic and later painted portrait ofthe poet decorated by laurels and two transparent glass pyramids with lyreand three-barow cross on both sides. Twelve young students dressed in

57. slovo, no. 14, March r, 1862:56; no. rg, March 15, rg62:7r. The next,.decrama-tional cVening," held on May I 5, I 8(r2, the annivcrsary of the abolition of serfdom, startedwith a thankful spcech by Zhan'kf on thc liberation of the peasants, and ended with a recr_tation by volodyrnyr Shashkevych of Shevchenko's passionate cossackorphilc poem lRoz_ryta mohlla. See Vistnyk, no. 52. May 22, lE62 2A6_07 .

58. on declamational evenings in Sambir, see letters of the local hromada members toTaniachkevych: L'vivs'ka Naukova tsiblioteka im. v. stcfanyka NAN Ukrainy, manuscriptdivision,fond l, od.zb. 560, ark. 18-23.

59 ' I l s tnvk , no .29 , Apr i l 29 , 1863 114- r5 ; no .3r , May6. rg63; 122. See arso Myk-hailo Vozniak, "Narodl.ny kul'tu shevchenka v Halychyn i," Naditia I I - l2 (t 9l I ): 4.

60' " 'Moloda Rus' v rokakh r860-60'. Z rukopysy u roku 1g66,, ' Di lo,no. zs, rebr. ts.1892: l-2.

6l. , l i rakhopud, no. 3, J,:ne 2I, I r j63: I 5.

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastern Galicia in the 1860s 39

Cossack costumes and mourning scarves stood at both sides of thetetrapod with lighted candles in their hands.62

In general, the ritual-purification movement caused a certain shift fromthe religious sphere of thinking to the national one. It created a specificmood among educated Galician Ruthenians that facilitated transconfes-sional intellectual contacts with the East Ukrainian or"Bukovynian Ruthe-nian activists and made everything connected with Rus' Orthodox heritage(Cossacks including) attractive. For a moment, the growing cult of Ukrain-ian poet, Orthodox Taras Shevchenko was also one of the signs of Ruthe-nian "ritualism". As one can see, young lJkrainophiles were not non-interested passive observers of the "ritualist" debates but active partici-pants.

The ritual-purifrcation movement slowed with the death of MetropolitanHryhorii Iakhymovych and the direct intervention of the Vatican in settlinginter-confessional relations in Galicia. Still, up to this date it had not lostits appeal for a considerable part of the Ukrainian Greek Catholics. Itsimmediate results in the 1860s cannot be limited to the growth of politicaland religious Russophilism in Galicia. In fact, its consequences were muchbroader. One consequence wai the so-called Concordia of 1863 - anagreement between the Greek Catholic and Roman Catholic prelates"ofGalicia initiated by the Vatican. Concordia strictly regulated the procedureof the change of ritual affiliation and made it exceptional from widespreadpractice.63

After the Concordia was publicly announced, the attention of GreekCatholic clergy shifted from the purification of rituals to the regulation ofchanges of the rite, and then, in 1864-1865, to the situation in theneighbonng Chelm Greek Catholic eparchy, the only one left under theRussian monarchy. The so-called "Chelm affair" became important foreducated Galician Ruthenians, mostly young priests and teachers, becausein 1864 many of them u'ere recruited by the Russian government to settlethere in attractive material conditions. After the defeat of the Polish Janu-ary uprising, in which many Chelm Uniates (unlike Galician Ruthenians)supported the Polish cause, the Russian government decided to combatPolish influences among them. It tried to make the ritual practices in theChelm Uniate eparchy uniform with those of the Russian Orthodoxs and toprohibit the use of Polish in the church life. As John-Paul Himka com-..rrcrts, Galician Ruthenian activists possessed all the qualities that madeihein attractivc assistants for the Russian government: they hated thePoles, atteinptcd to bring ritual practices closer to the Orthodox standard,

,i2. Vrl,lor i)etrykcvych, Istrtryia kul'tu Shev,chenJca sered gimnazuial'noi moladizhy,XXXViII; "Pi:,myrky Tar.asa Shevchenka," Sla',,c, no. 17, March 12, l8t:2:63.

ti3. 'irlcd;:imrciz OsadczJ. iit:lcio! i cerkiew na wspolnej drodze, 107 -10, 163-68.

and were becoming pro-Russian.uo As a resurt of the mass campaign,around 500 Galicians moved to Russia (according to the estimation ofStudyns'kyi).ut Not surprisingly. ,s/ovo commented favorably on the Rus-sian policy in the chelm eparchy (in l g64 arcund 40 articles were devotedto this issue). The tone of publications was becoming morri pro-orthodoxand anti-Uniate. some of Galician Ru(henian leaders, as IakivHolovats'kyi, engaged in the Russian nationalist discourse on ..polishquestion," contnbuting various materials on "the subjugation of RussianSlavs by the Roman church" to Russian periodicals.66 obviously, the ac-tive involvement of Galician Greek catholic public in the ,.ritualist" dis-cord in the chelm eparchy was seen by many scholars as a logical con-tinuation of the ritual-purification movement, especially taking into ac-count that Father Markel Popel', one of the leading ..ritualists" from early1860s, played a paramount role in the conversion of chelm eparchy to or-thodoxy in 1875.

From the perspective of Galician ukrainophiles, who until the mid-1860s crystallized into a separate ideological movement, the chelm cam-paign clearly promoted Russian imperial interests. A new concept was in-troduced into the public debates in 1863 by Meta - the idea that Russranorthodox clergy subordinated to imperial bureaucracy is .,the strongestfactor of the Moscowficationfmoskovshchenniaf of Rus,.', The creation ofa new ukrainian national narration of Greek catholicism was begun in anattempt to save the union (as the only possible llkrainian national institu_tion) from the unfavorable attitudes that dominated among the ,.youngRus'." Together with a developing anti-Russian polifical ptog*-, ukrai-nophiles changed their attitude to the uniate church. uia iamiued that"union was a great misfortune for Rus' and that Ruthenian people hatedthe union until recently," but stressed that the abolition of uni,on under theRussian monarchy resulted in the Russification of ukrainians.6T Thus, theconcept of the "lesser evil" appeared: taking into account the situation inRussian-rule'rl llkraine, Galician Ruthenians should defend their Greekcatholic character and combat orthodox influences. In general, Ilkraino-philes adopted many of the ritual-purification rhetoric and emphasi zed anunderstanding of the church as a social institution representative of theirnation' They focused on receiving church autonomy from Rome as a pre-condition of resolving the "ritualist" question. In 1g65, Meta stated that"the recent failure of so-called ritualist issue was caused by the fact fhat

canadian American slavic Studies/Revue canadienne Amdricaine d'dtudes Slavc

64. Hinrka, Religion arul Nationaliq,,p.34.65. Kyrylo Studyns'kyi, Z pozhovkll,kh l1,stki,,p.7l.(16. see, for example, "rvlaterialy dria istorii pravosravria v Galitsii,,' vesrnik lugo-

Zapadnoi i Zapadnot Rusi 4 l3i ( I 863): 29-34.67. "r lus'ke pytannie," &lera 3 (Ncrv. 1863): 2j0_it

Emerg'ing Cult of Taras Shevchenko in Auslrian F"\tem Galicia in the 1860s

rnstead of raising the question of church autonomy the "ritualist" questionwas raised, which was contained within [the problem of] autonomy anddid not need a decision from Rome." Mete also stressed that the autonomy"of our national church lnarodna tserkva]" was the main precondition ofits union with Rome.ut

Compared with the early 1860s, on the eve of Ausgleicft Ukrainophilesclearly changed their attitude to the ritual-purification movement and con-fessional issues in general. They aspired to build Greek Catholicism into aRuthenian national church with its own seltruling institutions, but at thesame time declared that the confessional differences with Russian tlkraini-ans would not handicap cooperation with them. The informal leader of thehromady network, Danylo Taniachkevych, proclaimed in 1867, "we arefor tlre Uniate Church, because we consider it as something better than aMoscow Jesuit Orthodoxy, with its autocratic synod."6e At the same time,he incorporated some important elements of Father Terlecki's progftrm,namely the demand for the creation of a patriarchate for the Austro-Ruthenian dioceses. If among the Galician Ukrainophiles in the early1860s there existed a certain longing for confessional and spintual uni-formity with the bulk of Ukrainians (Orthodox by religion), in the secondhalf of the 1860s the relations with the Ukrainians from the Russian Em-pire were clearly seen from an anti-Russian perspective, and a national-political solidarity was valued higher than a confessional one. GalicianRuthenians were to stay Greek Catholics but co-operate with OrthodoxUkrainians.To The Church was, as much as possible, to become nationaland autonomous.Tl

The growing reserve on the llkrainophile's side towards the ritual-purification issue, and the Old Ruthenian/Russophile annoyance with thecultural and political radicalism caused by Shevchenko's influence, plusthe restrictions of the Catholic authorities combined together, resulted inthe gradual disappearance of the "invented tradition" of Shevchenko'scommemorative church requiems. Already in 1865 the contributors toMeta felt the need to clariS, that Shevchenko's requiem mass in the Ortho-dox Llhurch was not a ritual demonstration or anti-Catholic action.72 A

68. "Ohliad pol i tychni i ," Meta, no. 2, Febr. 28, 1865: 60-61.(ri). Fcdor Chonrohora [Danylo Taniachkevych], I\s'mo narodovtsiv rus'kt,h do

redaktora politychnei chasopysi "Rws"' iako protest i memoriial (Vienna: Tyskonr:iomnrcra, I 867), p. 14.

70. "Iak my po::tupaly dosr i iak by narn dal 'she postupaty," Ras', no. 21, June 9,1867:L - q .

71. See the analysis ofthc ccclesiastical part ofTaniachkevych's pamphlet in Himka,ileligion at'ii Nationalih,, pp. 52-53.

72. ll,leta, no. 2, Fcbr.28. 1865: 61-64;"7-akazariieMety," Meta,no.3, tvlarch 15, 1865:72

Canadian American Slavic Studies/Revue Canadienne Amiricaine d'6tudes Slaves

year later LJkrainophiles in Vienna did not want to associate the celebra-tions of Shevchenko with the religious demonstrations and restrained fromorganizing and participating in requiem services.t3 The cult of Shevchenkobecame then associated not with the revival of an ancient OrthodoxChurch ritual as with the introduction of populist (narodiyts 'kyi) princi-ples into the Rutherrian language. "All announcements and invitationswere printed according to the Kulish's spelling, and, therefore, the olderRus' did not really participate in this event," complained Slovo in 1869.74Only Bohdan Didyts'kyi, the editor of Slovo, regularly attendedShevchenko celebrations in accordance with his own concept of llkrainianliterature.Ts Also, school authorities alarmed by such "ritualism," prohib-ited students from attending the Orthodox Church.76 Shevchenko's req-uiem masses continued into the 1880s, but attracted fewer people. Thesituation was not saved by the fact that a prominent Bukovynian Ruthenianwriter, Father Hryhorii Vorobkevych, a good friend of Galician llkraino-philes, became an Orthodox priest in L'viv at the end of the 1860s. He no-ticed in 1869 that while only a few attended church requiern services,many more (including.around 200 ladies) came to the evening concert de-voted to Shevchenko.

When the tradition of the requiem church services vanished, a new insti-tution of Shevchenko's yearly commemorative "evening" (vechir or ve'chernytsi) again evolved from the irregular musical-poetical concerts or-ganized by Ruska Besida in 1862-1863. For the first time Ukrainophilesorganized separate "evening" devoted to the memory of Shevchenko inPeremyshl' on March 10, 1865.78I1consisted of public readings of his po-

73. L'vivs'ka Naukova Biblioteka im. V. Stefanyka NAN Ukrainy, manuscript division,

fond 1, opys 2, od. zb. 175, ark. 541-541 zv. ln 1867, Volodyml'r Shashkevych evenclaimed that Shevchenko's requiem services in the Orthodox Church were secretly inspiredby St. Petersburg in order to promote pro-Russian feelings among the Ruthenians. See

[Volodymyr Shashkevych], "Iak my postupaly dosi i iak nam dal'she postupaty," Ras', no.21. June 9. 1867: 3-4.

74. Slovo, no. 18, March 13, 1869;4.75. Aohdan Didytskyi, a prominent Galician Russophile, belicved that the works of

Ukrainian writers made Galician Ruthenians losc the habit of stressing words in a Polish-like way and, notwithstanding the use of vemacular Ukrainian, introduced "Russian syl-labic systern" into Galicia. He highly valued Shevchenko, but insisted that Ukrainians andRussians should in future create common literature and culture. See Bohdan Didyts'kfi,Svoezhyttievly zapysky. vol. l. p. 3 | .

76. See the cornplaining articles in Meta on the prohibitions: Metd, no. l, Febr. 17,I 865: 32.

77. "Materyialy do istoryi znosyn Halychan z BukovYritsiamy," Ruslan, no. 183, Aug.2 6 , 1 9 0 8 : 3 .

78. This first Shevcheirko conlmemorative evctlng was organized, nevertheless, withsome assistance fiom the church authorities. '!'ire "evening'' was held in the hall belonging

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in the I 860s

etry, poetry devoted to the poet, a commemorative speech by DanyloTaniachkevych (which became the model for such speeches for the nextdecadeTe) and of several musical performances including a choral singingof Shche ne vmerla Ukraina. The concluding part of the evening had aclear "resurrectionist" message. Ksenofont Klymkovych read the poemwhich stated that although "our great nation" still did,not enjoy freedom,with the effort of patriotic Ukrainians, it would resurrect from the ashes asa phoenix; then the motto "Llkraine is not dead yet" (ascribed toShevchenko) was repeated by the choir.8o

In a similar fashion, the Galician Ukrainophile students organizedShevchenko's cornmemorative evenings in 1866 in Vienna. In 1868-1871through the efforts of Ruska Besida, which finally passed in 1870 into thehands of Likrainophiles, after a certain interlude these evenings were againheld in L'viv.8r At that time, the Old Ruthenians and Russophiles boy-cotted all activities of the Ukainophiles and did not let them in the Narod-nyi Dim. Thus, the "evenings" in 1869-1871 took part in the hall of theSharpshooters' society (L'vivs'ka Strilnytsia) controlled by the Poles.82 Atthat time Galician Ul:rainophiles tried to reach a compromise withGalician Polish politicians that received upper hand in the province. Thelatter were interested in using the former against the Russophiles. In 1872,the L'viv {,Ikrainophiles could use the hall of L'viv city council, what wasseen as a clear sign ofPolish support for their undertakings. In 1873-1874the Shevchenko cornnemorative evenings again took place in the L'vivcify council hall, and were attended by the Galician Viceroy Count AgenorGoluchowski and the speaker of the Diet Prince Leon Sapieha.t' Tyt Re-vakovych, an flkrainophile activist, who deliberately came to L'viv to takepart in the 1872 evening, noticed with satisfaction that "by the unusualgreat number of participants [500 according to the estimations of Ukraino-phile journal Osnovaf, one could see the unceasing growth of

to thc Grcek Catholic cadredra'l chapter. and the entrance fee was collected for the buildingof anothcr Crcek Catholic Church (nn Bktniakh) in Peremyshl'. Anatol' Vakhnianyn, ,Spo-rnyxy 7 lfi1'rid, pp. 66-67.

79. Viktor Petrykerych, lstoryiu kul'tu Shevchenka sered ginnazS,ial'noi molotlizhy, pp.XL,VI]I-LII .

d0. "Vechemytsi v pamiat ' ' Iarasa. Dopys'z Percnryshl ia," Meta, no.3. lv ' larch 15,I ri(r-s: '/9-88.

8 l . In I 868. the tradition of choral singing of Shcvchenko's Zapovit on the music ofL4l,kola Lysenko r';as introduced (Pravdu, rro. 8, Nov. 30, 1868: 95-96). See the description::f other Slrer,chenko's cvenings in Pravda, no. 9, March 8, 1869: 83-84; )'ravla 3 (1870):144-45l ' Osnova. rro. I 9, March 17, I 87 | : I 8l-82.

82. Prn;au, no. 7, l jebr. 22,1869:64.83. Siov,-r. no. 25, March 11, 1t7,1: 3; Pravdu. no. 3, lvlarch 2"7, 1873: 134-i1

"Novy:rkV". ! ' ruvda. ro.4, March I3. i874: 13941.

Canadian American Slavic Studes/Revue Canadienne Americaine d'dtudes Slaves

Shevchenko's cult in Galicia."8a Those members of provincial hromadywho could not take part personally in the Shevchenko's evening sent greet-ing telegrams. A similar public Shevchenko evening was held in 1872 inPeremyshl'. In the second halfofthe 1870s and early 1880s, such eveningsstarted to be organized in other provincial towns of Galiiia: Stanislaviv(1877), Kolomyia (1880), Temopil' (1882), then in Zharazh, SudovaVyshnia, Kalush, and later even in the countryside.8s They became an im-portant element of the emerging cult of Taras Shevchenko in Galicia andwith the course of time obtained the character of national tradition.

In the 1870-80s, along with the officially sanctioned public celebrationsof Shevchenko, the members of hromady continued to organize their ownsecret yearly evenings. The pre-Soviet llkrainian scholar ViktorPetrykevych, attempting to catch the mood of these events, commented:"secrecy

[. . .] sunounded them with the nirnbus of the devotion to theidea. All felt as one family, all were aware that they were united by thesingle idea."86

The commemorative "evenings," devoted to Shevchenko, obtainedmany ritualistic features, since they recalled "the divine pattern" of poet'slife. The life and poetry of Shevchenko were often associated in UkrainianGalician national discourse with the sacrifice and message of the Savior oran Apostle. Even the rhetoric of worshipping Shevchenko, employed bothin public and private texts, was directly borrowed from church practices.Sometimes the members of hromady wrote about themselves as about thefollowers of the "Apostle Taras [Shevchenko]."tt In the correspondence ofTernopil' hromada members with Volodymyr Shashkevych in 1865,Shevchenko was named *immortal Father," and his verses celebrated as"the sacral words of our immortal Prophet."88 This crypto-religious side ofShevchenko's cult in Galicia was probably reinforced by the fact that hiscult was introduced ltrst in religious form, as a part of the ritual-purification movement.

84. Vasyl' Shchurat, "S'viatkovanie rokovyn smerty Shevchenka v Halychyni (1862-1870) zi spomynamy o. E. Lysynets'koho i st. rad. T. Revakovycha," Nedilia t I -12 (l9l 1.1:(ti Osnova, no. 17, Febr. 29,1872: l-2.

85. Viktor Pefykerych, Lstoryia kul'tu Shevchenku sered gimnaltial'noi molodizhy, pp.

XXXX.XLI.86. I bid., pp. XLV-XLVIII.87. L'vivs'ka Naukova Biblioteka im. V. Stelanyka NAN Ukrainy, manuscript division,

.{ond l, od. zb.560, nrk. i2.88. L'vivs'ka Naukova Biblioteka im. V. Siclar 'ylra N,\N Ukrainy, man',rscript division,

fond 2, opys 2. od.zb 175, ark.483-484, 536.

Emerging Cult of 'faras

Shevchenko in Austrian Faqtem Galicia inthe 1860s

Interestingly enough that for short but crucial period of the early 1860sthe ritual-purification movement on the one hand and on the other Cos-sackophilism were two principal attempts of Galician Ruthenian intellec-tuals to find a "useful past" for modern national discourse. Both stimulatededucated Ruthenians to think beyond the limits of Habsburg and Catholicloyalties, and both were inspired by the anti-Polish staqce typical for a partof Galician Ruthenians since 1848. Galician Ukrainophiles initially playedan important role in both endeavors, since they accented their affiliationwith the East llkrainians. This explains why "Orthodox" Llkrainian writersand historical heritage became so popular among the Greek CatholicGalician Ruthenians. Interest in Eastern Church ritual prevailed at the be-ginning of the 1860s, as a sign of solidarity with pre-modern Rus', andserved as the basis for both cultural Russophilism and Ukrainophilism.Paradoxically, the cult of Shevchenko and the Cossacks appeared inGalicia not in spite of the fact that they were seen as Orthodox figures, butprecisely because they were. With the course of time the Galician Ukrai-nophiles reformulated their position in the confessional question, becom-ing less interested in ritual reform, but focusing instead on the nationalautonomy of the Greek Catholic church.

In general, the endeavors of the early Ukrainophiles in 1860s and eady1870s resulted in the "cultural revolution" that profoundly influenced thenational identity of Galician Ruthenians. One could hardly overestimatethe effects of their activities. During the 1860s and early 1870s GalicianlJkrainophiles accomplished several important cultural proiects, cruciallytransforming the culture of the educated Ruthenian public, which then be-came the main factor that united educated Galician Ruthenians withLlkrainians from the Russian Empire.

Emerging Cult ofTaras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in the I 860s

$"rrc", I,,an Vrtkh*t 'WF'pFt*-p"*y*i'tt" Uot'^osluzhenie za upokoi Tarasa

Emerging Cult of Taras Shevchenko in Austrian Eastem Galicia in the 1860s

Illustration 2. Cartoon Presenting the Attitude of Ruska Besida toShevchenko. 1 863.

sfiocfia Bb BE0B[B.

I2lrctpd -' .,t lo u1,rr ? .,tltitil91 .' lf u lrrr ,t.y,lir

Iro l1li"l<lrli f).y<.lr ?

foperyn: Iu ! I 'nr. --

. i rr .n!_. 'rO l l f t l t r - r t( ,1t, _ t(o.

Iroc'Ta - tr((, ?,itlf,l. eJflRut,tii

' , i

1'0t4 utn$nta ' t ' t r l t r - t r - l ' t ) u( : l . rn l la(r?,

isource: Source: .Srra!@

"'Yurets [St. Georgian]: What is it? . . Ahal

Yurets [upside down]: Did you not hear -famous tirio,rshout all of Rus"/

-- It is Shev - chen - ko.about a poet - he is'so

f Eisdls fL fldlil.aTtl

Tapacat i l $ f f iX t r

flralauro p*cr'nitt afq;*. ft';tr.fp*.!rr{"{t {}1* * d*xylr tt't* 6tct{ti.,tabt q !'ry* 6ttu+t rrrt44!"4 sr :a {F* rK Sa a tr{f, t&d r* t sg{pej

{.l,as* .a lF{w**tii t$* s. *tx,i

llffissr$sn$ $ffifYffifre$.* rfri r$at Sstr*t irr.dep .t &.sw!4e 4Wn '!\r +\.f'ttr&ret*i tt{'*

Shevchenka 1 862 roku V L' " ryi!yrySll4!/1-1!8j1 9 1 2) : I 45'Yurets'.IIirrm! Flmm - this Schvzmatvk - this is not for us."