Falling between the real and the ideal: The role of the New Zealand principal

Transcript of Falling between the real and the ideal: The role of the New Zealand principal

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 3 3

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS

The Real and the Ideal:The Role and Workload of SecondaryPrincipals in New Zealand

JENNIE BILLOTCentre for Educational Research and Development,UNITEC Institute of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand.

Abstract: The role ojschool principals has changed markedly since the introduction of Tonwnow'sSchools for whilst being expected to be leaders, it is acknowledged that principals have theresponsibility Jar managing their schools within the oversight of a governing body. Research hasidentified detrimental impacts on the principal's role in terms of increased workload and stress (Harold,Hawksworlh, Mansell & Thrupp, 2000), so given that the principal's role is pivotaJ in ike schoolcontext, it is imperative to address the (fusion between role and workload.

This paper provides discussion on the New Zealand component of a collaborative study undertakenin New Zealand and Queensland, Australia. Tlic project focused upon what principals report theyactually do compared with both what they would like to do, as well as what they believe theiremployers expect them to do. The underpinning skills and competencies for school leadership were alsoinvestigated.

Key Words: Secondary Principals; Role; Workload; Self-managing Schools

IntroductionTHERE IS A GROWING concern about the role and workload of the New Zealand secondaryschool principal, particularly with regard lo sustainability within the current demands ofeducational reform under Tomorrow's Schools. The study informing this paper is a collaborativeproject with Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Australia primarily concerned withthe Role and Workload of Secondary Principals in New Zealand and Queensland. The NewZealand component is the focus of this discussion and draws on findings from the data collectedfrom a questionnaire from 240 principals, a focus group of principals and a number of interviewswith stakeholders. There was an exceptional receipt of questionnaires from principals indicatinghow critical the issue is in the present New Zealand educational environment. Given that theprincipal's role is pivotal in ihe school context it is imperative to address the tension between roleand workload.

The perceptions of roles, responsibilities and workloads with regard to recent and currentchange agendas in New Zealand are of particular interest to this study as is the reported alignment(or lack of alignment) between actual (real) and preferred (ideal) roles lor principals. Theimplications for professional development are also noted. In the context of continual change for

3 4 ISEA • Volumes, Number 1,2003

schools, school leaders and educational systems this study is a timely contribution to both pohcyand practice.

Background and contextSocio-economic changes in the western world over the last 20 years have been characierised byforces that have propelled "fundamental changes in the policy world surrounding schools"(Murphy & Hallinger, 1992 p.78). These changes acknowledge that education plays a major partin not only developing citizens as national assets but also does so in a way that reflects thepolitical values of public participation and decentralisation (passing the responsibility of practicesfrom the government to others).

Hence government initiatives over the last two decades have aimed at advancing theeffectiveness of schools (Creissen & Ellison, 1998) by LUllising changed forms of organisationand governance. One consequence has been school restructuring that gives schools greater powerto control their own finances and resourcing. Tbis has had major implications for the principalwhose role has changed both in form and function (Moore, George & Haplin, 2002),

It is well documented in the literature that the roles and workloads of principals have changedin recent years (see for example Blase and Blase. 1997; Cranston, 1999; Moore et al. 2002). Inpart this has been the consequence of organizational reforms such as school-based managementinitiatives together with increasing demands on schools to respond to often rapid anddiscontinuous societal, political and economic changes. Decentralisation has been seen toprovide the means to improve tbe performance of education systems Oohansson & Lundberg.2000) and one of the most prevalent approaches in the public educational system bas been thedevelopment of [he school-based management model. However the resultant changes haveresulted in the principal's role and workload becoming more complex (Fullan, 1998) withpressure arising from role ambiguity and role overload.

School-based management has had a significant impact in New Zealand and a brief review ofthe restructuring that occurred al the school level can aid an understanding of what ii means tobe a New Zealand principal today Whilst other countries have chosen a similar devolution pathwithin education. New Zealand's move to self-managing schools within the policy of Tomorrow'sSchools (Minister of Education, 1988) has been implemented at a fast pace. It is well known thatthe aim of the reforms was to:

...increase the responsiveness of the New Zealand education system and the satisfaction witheducation of all significant stakeholders (by),..altering the incentive structure within theadministration of education through two major structural changes.

Education Review Office 1994, p. 5

The two changes were to abolisb "layers of administration in order to locate decision-making asclose to the point of implementation" and secondly to "alter the balance of power between theproviders and clients of education" (1994. p. 5). This represents shared decision-making amongkey stakeholders at the local level becoming a defining characteristic (Cranston, 1999). Hallingerand Murphy (1992) noted that the changes in the policy context of schools has transformedprincipalship through a greater emphasis on managerial functions, a transition consistent with theeconomic rationalisation of the state before the education reforms were implemented (Codd. 1993),

Research over the last two decades on school effectiveness reinforces the claim thai principalleadership is the key to school success (Portin, Shen & Williams, 1998) with the prmcipal's role

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 3 5

seen as central and having major responsibility for decision-making (Harold. Hawksworth,Mansell & Thrupp, 2000). In essence, 'principals are crucial to the development and maintenanceof effective schools' (Hausman, Crow iSr Sperry, 2000, p. 5).

Hallinger and Hausman (1994) extend this to suggest that principals of schools shaped by

restructuring Initiatives are:

Sandwiched between local pressures exerted by school-based management and centralizingforces ... principals are under constant pressure to remain responsive to parents and staff,while simultaneously meeting the expectations of centrally imposed guidelines.

Hallinger & Hausman, 1994, p. 163

This more recent redefinition of principalship presents enormous challenges for school leadersas they evaluate the different skills and capacities needed to carry out their roles.

The principal's role within this educational context is unique with respect to the manyoccupational roles that it encompasses; in reality it spans the interface between external andinternal environments. This can result in principals feeling tom in different directions with muchof their time being spent not on instructional or curriculum leadership, but the managerialconcerns of school operation (Ornstein, 1993). Hausman et al., (2000) prefer to view idealprincipals as negotiators of the environment and less as managers of a school system but for manyprincipals the leadership challenge under Tomorrow's Schools is to balance all, often conflictingroles.

It bas been observed that "self-management has brought new discourses into schools-that ofa 'public management' and a 'new work order' ". (Helsby. 1999, cited in Harold et a!.., 2000. p. 6),within which principals experience ambivalence and tension between professional andmanagerial roles (Harold et al., 2000). This has had implications not only for the day-to-day roleof the principal in New Zealand but also the gradual acceptance of, and consequent developmentof. associated managerial structures that perpetuate role ambiguity Wildy and Louden believethat principals are forced to "steer a steady course between apparent opposites" (2000, p. 173)and successful principals are those wbo manage to negotiate contradictory dilemmas. This hasfuture implications for school leaders as they have less room to move within externally initiatedchanges and continue to wrestle with increasingly complex yet constrained circumstances(Fullan, 1998).

Dimmock and Walker (2000) encapsulate the challenge for principals in this way:

School principals become more isolated from teachers and students and from Lbe corecurriculum functions of the school as they become office managers focxising on administrativeissues and meeting accountability expectations of central bureaucracies. An administrativerather than educational or instructional emphasis to the principal's leadership role is alsomore likely from the policy of scbool-based management.

2000. p. 2

It is in this context that it is important to hear the voices of principals as to bow structural andsocietal changes are affecting their role and workload. The research study undertaken in NewZealand and Queensland that informs this paper seeks to examine the degree of fit between therole of the principal as systemically defined and that expressed through principals' comments.

3 6 ISEA • Vohime.'il, Number 1, 2003

The focus here is upon New Zealand data with reference to the principals' viewpoints as to whatthey actually do compared with what they would like to do and also what they believe theiremployers expect them to do. Both role and workload issues are explored which according toLovegrove (2001) underpin the two areas of concern for principals in New Zealand, principalprofessional development and workload. The findings will therefore also inform recommendationsfor possible professional development needs for school leaders.

MethodologyThe data that informs this report is drawn from three methods.

Focus Group

A locus group was conducted in 2001 with a group of eight principals, focusing on issues such asthe main responsibilities of being a principal, the main challenges encountered, the skills andcompetencies necessary for the role and their understanding of the expectations of the Ministry ofEducation. The focus group process provided a vehicle for the expression of principal perceptionsof their role and an appreciation of their aspirations and frustrations. The advantage of using thismethod is that group discussion provides more valuable insight into issues than does a "summationof individual narratives extracted in inter\'iews" (Goss & Leinbach 1996, p.U5).

InterviewsInterviews were semi-structured with an interview schedule developed after reviewing the literature.Questions were based around issues including the roles of principals; main challenges for principals;and skills and competencies identified as necessary to be a principal. Interviews were held withrepresentatives from the New Zealand School Trustees Association (NZSTA), Principals' Council(PC) and Secondary Principals' Association of New Zealand (SPANZ). An interview was also heldwilh a representative from the Ministry of Education whose influence on education in New Zealand

... is iiidirect as we are not a provider of education. Our role is facilitative rather than directiveand we empower through our leadership and management of the infrastructure, problem-solvingability and assistance to those at risk of undcrachievement.

Ministry of Education, 2002

As the Ministry advises on and implements edtication policy, develops curriculum statements,allocates resources and monitors effectiveness in the sector's providers, their involvement in framingthe role of the principal within the devolved model of education in New Zealand is crucial and needsinput to this study.

QuestionnairesThe qucsiionnaire was developed in consultation with the Queensland research partner and ideasand concepts emerging from a study of the literature and used within a similar study examining theroles of secondary' deputy principals. The questionnaire was designed to elicit data on principals"views of their daily workload, a typical weeks responsibilities, the type of work undertaken, skillsand competencies needed for the joh and suggestions for appropriate professional development.Some of the questions aimed at obtaining information on what prineipals actually do in iheir rolewhile others sought to gain principals' personal viewpoints and perceptions of what their role shouldand eould include.

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 3 7

The format of the questionnaire aimed at a high response rate (acknowledging the busy lifeof principals) and so comprised 18 closed questions and three open-ended (more general)questions. The latter focused on principals' views on the persona! strengths they brought to therole and the skills and competencies they would like to develop through professionaldevelopment and support opportunities.

Questionnaire responses were collected in 2001 from secondary school principals across NewZealand and there was a 59% response rate for the New Zealand questionnaires (compared to35% in Queensland), with the majority of questionnaires being personalised.

FindingsThese arc reported under a number of key headings using the data from the questionnaires andillustrated by comments from the interviews and group discussion.

School and General Characteristics of RespondentsThe majority of respondents ((i4%) were located in urban areas as against rural areas, with schoolsbeing represented in all decile categories. Within the data collected for this project, fewer schools(13%) were in the lowest decile category with the highest being 34% in decile 3-5. This representsa lesser response from principals at schools with the lower decile ratings.

The majority of respondents (94%) were working in state schools with only 6% representingindependent schools, 69% of the respondents were male and 31% were female. Only one-thirdof respondents have more than nine or more years experience although only one-quarter haveless than three years. Three-quarters of respondents have been principal al their current schoolfor more than four years and most principals (95%) have been principal at two schools or less.Of the respondents 83% are satisfied or very satisfied with their role as principal with only 7%being dissatisfied.

The principals in tbe focus group and those interviewed reported that they found being aprincipal very rewarding. One principal from the focus group emphatically declared: "1thoroughly enjoy tbe role of principal and it gives me a huge sense of satisfaction". The group asa whole affirmed that being a principal allowed them to "make a difference" for students, staffand the community.

Unsolicited comments from the open-ended questions in the questionnaire included:I love my job.Despite the workload it is a hugely satisfying job.A stimulating, challenging and very rewarding job.

Level of satisfaction was related to:

• pressure felt by the principal;• role overload as a principal;• time principals dedicated to strategic leadership in a typical week (actual);• time dedicated to curriculum leadership in a typical week (actual);• difference between the time they actually dedicate to strategic leadership and what tbey sec

as ideal in this regard;• difference between the time they actually dedicate to strategic leadership and what they see

as the system wanting in this regard; and

3 8 ISEA • Volume .31. Numher 1.2003

• difference between the time they actually spend on student issues and what they see the systemwanting in this regard.

Importantly, at a macro level, overall satisfaction was related to:

• the overall difference between principals" actual tor real) and the ideal (preferred) timeallocations; and,

• the overall difference between principals' actual (or real) and the system preferred time allocations

Two-ihirds of respondents believe role ambiguity is a concern for them and more than three-quarters believe the same for role conflict. Role overload exists to a great extent by three-quartersof respondents. Additional comments received supported this data:

The workload is relentless.The workload is unrealistic.The role and workload is oui of control.U is a whirlwind exigence.We are being crushed by the workload.

Many principals expressed the concern that the workload affects home and personal life and in oneinterview the principal suggested that the incessant demands were creating "tentacles of misery".Another principal blamed work overload on the "lack of vision/strategy of the Ministry ofEducation in their processes and hence the ambiguous demands and constant moving sands."

In general, the summation of comments indicated that competing demands from thecommunity. Ministry, and other stakeholders ofien left the principal feeling overwhelmed. Oneprincipal summed this up by stating that "just getting through the day is an achievement''. Thedilemma appears to be "balancing/managing the huge requirements for accountability,administration etc with the requirements for educational and professional leadership,"

General Aspects of the Role and Responsibilities of PrincipalsJusi under a half of the respondents indicated that the number of hours worked in their role hadincreased compared with earlier. Of the respondents 85% indicated the pressure they felt in the rolewas high although only about one-half indicated that this pressure had increased compared withearlier. 40% felt that therewasnochangein the pressure experienced. Just less than three-quartersreported that the variety and diversity of what they did in their role had increased. It appears thatgenerally principals feel that while the pressure in the job is high, it has not changed significantlyfrom earlier although tbere is a significant increase in diversity in tbe principal's roie.

Focus group and interview responses placed more emphasis on the increasing role demands.One principal stated that "the job is at least four times tbe job it was wben I started in 1991" wbileanother explained that "sadly the demands increase each year" with "too many compliance issuesand now the Education Standards Act witb iLs planning and reporting," One source of tbe problemwas attributed to tbe "rate of change" and the Governtnent wbo constantly "cbanges tbe goalposts." "A lot of time is spent by principals focusing the school and community to new issues suchas NCEA." All interviewees conceded that the principal now had a greater workload than inprevious years, causing tbem to work longer hours and increased pressures from more sources.Several principals asserted tbat they work 80-100 hours per week.

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 3 9

The reai concern expressed by the respondents was the future repercussions of the heavy

workload. This comment summarises this concem.

My staff perceive the principal's role as being enoTinously challenging and demanding. Themarket force environment of the Nineties, together with the constancy of change, has placedhuge demands on the principal to the extent that many potential principals are being put offsenior management.

Specif ic Aspects of the RoleThis section of the questionnaire sought to identify the focus that the principals identified as'actual' as against 'preferred' in their role. The data collected related to how the principals viewedtheir role from three different perspectives:

• how they actually spend their time in a typical week;• how they would prefer to spend iheir time in an ideal week; and• how they believed the system would like them to spend their time in an ideal week.

For each of these perspectives the principals identified those activities on which they spent mosttime, including different forms of leadership, management and issues involving students,community and staff

The categories of activities were constructed after searching the literature on the changingrole of principals, noting especially the competition between administration and educationalleadership with the former often taking up tnore of the principals' time (Wylie, 1997). This hasbeen reiterated by Leithwood and Menzies (1998) who noted that under all forms of school-basedmanagement principals spent less time on educational roles and more on managerialarrangements. The balance between the content of the questions acknowledged these assertions.

As educational/curriculum leadership facilitates the teaching-learning process it underpinsthe work of school leaders, for if principals are going to co-ordinate school improvement effortsthey need a sound base of knowledge in curriculum and instmetion (Murphy & Hallinger, 1992).Baker and Dellar (1999) see this form of leadership as going beyond administrative managementto attend to the quality of teaching and learning.

Sitnilarly, as principals are accountable to both school, community and system they are oftenfaced with competing interests so being a strategist becomes a necessity Thus strategic leadership(a category within the questionnaire) utilises the ability to read the political scene, use in-depthknowledge of research coupled with theabihiy to model excellent teaching and learning strategiesand communicate to the wider educational community (Boyle, 2000). While these terms havecreated different categories they overlap in reaHty, for as Catdwell and Spinks (1992) claim, theprincipal needs to be expert in the areas traditionally associated with instructional andtransformational leadership, but in which special emphasis is given to the leader being able toformulate strategic intentions.

4 0 ISEA* Volume3], Number 1,2003

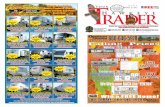

Table 1: Rating of Principals on Time Dedicated to Specific Artivities in a TYPiCAL Week.

Activity

strategic leadership

educational/curriculum leadership

management/administration

student issues

parent/community issues

staffing issues

Time dedicated

Great deal of time (%)

21

14

78

34

44

46

Total 241 respondents

Some time (%)

44

57

20

51

46

49

A little time (%)

34

29

2

14

10

5

Tiie role of the principal in a lypical (or real week) (Table 1) was reported as dominated bymanagement and administration (78% of principals devoting a great deal of time), student andstaffing issues, community issues were also doniiiiant. Notably strategic leadership (21% devotinga great deal of time) and educational and curriculum leadership (14%) both had significantly lessprominence. This pattern has been examined by Moore et al., (2002) who promulgated thenotion that "the work of the headteacher is located within models and discourses of management(op cit) many of which have equally long-established histories in ihe world of business" (2002.p. 178).

From the comments offered in the questionnaire, one principal summed up the challenge ast^p ".juggling of competing demands of paper and people" while several used the term 'CEO' todescribe their position. This notion of the principal as "CEO' appears lo be an issue for debate asit was strongly rejected within one interview as an acceptable description of a school principal.The interviewee was adamant that the term may fit a market model of leadership but does not sitwell with the professional beadteacher role. However the leadership role is expressed, there isgeneral consensus that "the administrative requirements, along with the management of students,leaves little time for the big things to discuss with stakeholders."

Table 2: Rating of Principals on Time Dedicated to Specific Activities in an IDEAL Week.

Activity

strategic leadership

educational/curriculum leadership

management/administration

student issues

parent/community issues

staffing issues

Time dedicated

Great deal of time {%)

73

70

3

a13

10

Total 241 respondents

Some time (%)

26

27

61

44

64

62

A little time (%)

1

3

35

45

22

28

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 4 1

The frustration arising from balancing what the prineipals believe to be important strands of theirleadership, with the e.xternally driven administration and management demands, seemsencapsulated in this comment:

No matter how hard or efficiently I work, I have accepted that I will never catch up lei alone

get ahead.

In contrast, in an "ideal week" (Table 2) the principals would reverse the typical situation asoutlined above. Of the principals, 73% stated that they would devote a great deal of time tostrategic leadership and 70% to educational leadership. In other words strategic leadership andeducational leadership would have more focus with a far less emphasis placed on managementand administration and student issues.

Table 3: Rating of Principals on Time Dedicated to Specific Activities in an IDEAL Week froma SYSTEM Perspective.

Activity

strategic leadership

educational/curriculum leadership

management/administration

student issues

parent/community issues

staffing issues

Time dedicated

Great deal of time (%)

76

77

56

24

45

34

Total 241 respondents

Some time (%)

19

16

31

33

40

39

A little time (%)

3

5

11

37

13

23

The role of the principal in an ideal week from a "system" perspective (as viewed by principals)(Table 3) is more balanced. While management and community issues are still seen as a priority,strategic and educational and curriculum leadership siill feature as the most significant activities.The principals identify a focus on both leadership and management as dominant from a systemperspective. The comtnents recorded in both questionnaires and interviews also supported amore balanced role as being essential. One comment saw this as the principal "standing in themiddle of all demands" not only achieving work accomplished by a CEO but also "leading avision for the school" (community).

Achieving this balance is not an easy achievement as one principal explained:

The dilemma of balancing/managing the htige requirements for accountability, administrationetc with the requirements in educational and professional leadership is the problem andpressure for the principals.

Principals reported their "typical" role as being quite different from both what they would Uketo see ideally, as well as what they expected the system would like to see of them as principals

4 2 ISEA • Volume 3 /, NiifnWr 1,2003

Table 4: Comparison -Typical and Ideal Week: Rating of Principals Spending a Great Deal ofTime on Specific Activities.

Activity

strategic leadership

educational/curriculum leadership

management/administration

student issues

parent/community issues

staffing issues

Great deal of time dedicated in

Typical week%

21

14

78

34

44

45

Total 241

Ideal week %(principal perspective) (

73

70

3

8

13

10

respondents

Ideal week %isystem perspective)

76

77

56

24

45

34

(Table 4). In general, respondents suggested they would like to see their role more concernedwith leadership, while the system expects boih leadership and management roles. At present,management and administration have a high dominance which principals would prefer they didnot hold. The earlier comments on role conflict and ambiguity are relevant here as these issuesaffect the degree of satisfaction felt by principals.

Skills and Competencies Important to the Roles and Responsibilities of Principals

Table 5: Rating of Principals on Skills and Competencies Important to Role as Principal.

Importance

Skills & Competencies very important % important %

inspiring, visioning change for school 90 10

demonstrating strong interpersonal, people skills 92 8

capacity to delegate, empower others 72 27

managing uncertainty for self and others 40 S3

managing change for self and others 50 4g

capacity lo develop networks 41 55

effeaive and efficient manager, administrator 66 32

Total 241 respondents

NOTE: Not ail respondents provided daia hence in some caiegories 100% was not achieved

Over 90% of the principals identified "inspiring and vi.sioning change for their schools" and"strong interpersonal/people skills" as the key skills in undertaking their role (Table 5). Thesewere supported by sound "delegation and management skills".

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 43

The Focus group principals echoed this emphasis on inspiring and visioning and also reflected onthe "passion and the mission" that they broughi to the role. Another comment highlighted the "needfor a vision from which you do not deviate, even though how you arrive at it may have tnany variedroutes".

Being a visionary/inspiring lcLider is not without its problems as other comments also indicated:

/ feel like a Traffic Officer on points duty at times, holding it all together, celebrating successes, keepingit whole, fostering a sense of community, selj worth, vibrunt and growing.

With respect to interpersonal skills, some commented as follows:

/( is a complex people-intensive posilioti (being a principal), demanding much. It is impossiMe

to please everyone, so all one can do is operate according to principle, be constant as all need

to trust you.

You've got to be able to manage every single member of your staff Individually and in teams.

You need to relate to students, business, community and parents and hold all the ne(worfes together.

Another observation from an interviewee reinforced these views:

(Principals) have lo be people who have huge people skills and the ability to manage and co-ordinateand keep whole large teams of disparate groups of people worliing at the best possible way they can.

While leaders hip skills are identified as very important, it is conceded that management andad tn in is I rat ion skills are also highly relevant to the demands of the principals role. One principalexpressed that he saw his job "as managing a business" but added that "schools need moreadministration support."

An associated issue for principals was raised in some comments that indicated resentment aboutdifferences between the schools in terms of workload demands.

Small schools suffer here, the principal is all things to all people.

It is totally unsatisfactory that I should run a school of 76 staff and be paid the same rate as someone

running a school of 20.

This issue of differential workload in different types of schools (as perceived by principals) isexacerbated by "the competitive nature of the present structure (which) increases stress and detractsfrom the core business of schools. This creates the need to market." The need to market schools inthe current competitive sehool environment links with workload issues as one principal explained:

I am very conscious of the large amount of time I spend on what would loosely be termed as'marketing'. There is an inequity between principal workload in this respect: (especially for) lowerdecile, falling school rolls where disproportionate amounts of time and money are spent onmarketing through necessity.

4 4 ISE.A • Volume .iI, Numi^er 1. 2003

Although many principals expressed concern and pessimism regarding workload and thecomplexity of the demands placed upon them, some optimistically indicated that they wished to"do the right thing" and feel that they 'have the power to do so". Observations were also maderegarding strengths that principals need to possess, namely being hard workers, keeping a senseor humour, being able to speak their mind bul also he trustworthy, honest and firm in order to"achieve common goals".

Two interviewees reflected that since "a principal stands in the middle of it all' with the taskof "bringing a pedagogical understanding of what's appropriate in the modern day" they will need"learnt capacities" to support ethical, moral and professional strengths that they should bring tothe role. These capacities have been identified hy Gurr as vital in:

"the current climate of change, scarce resources, decentralization, increased accountabilityand external pressures on schools, (where) the need to reflect upon the decisions tbat aremade and to justify these in terms of doing the right thing are becoming more important."

19Q7,p. 11

This assertion provides a richer conception of leadership with 'a greater emphasis on theprincipal as leader in learning (but also) on the moral dimension of leadership and on beingresponsive and accountable!" {Gurr. 1997. para. 69: conclusion). "As the role of principalchanges so leadership in self-managed schools increasingly demands leadership that lias moral,technical and educational foundations" (Murphy & Hallinger, 1992).

Issues for discussionThe findings as given above may well come as no surprise to secondary principals but do serveto illustrate a number of salient points for examination of the overall role of New Zealandprincipals. It is encouraging that the majority of principals (85%) are satisfied or very satisfiedwith their role despite citing significant role overload (76%). role conflict (85% to some or greatextent) and role ambiguity (54% to some extent and 10% to a great extent).

Tbe majority of principals have declared role overload, a problem noted by Portin et al.,(1998) in their study of principals in the state of Washington, Ofthe sample, 91% had increasedworking hours and 81% cited managerial functions reducing their ahility to provide instructionalleadership. Whilst the majority of the New Zealand principals cited increasing workload, therespondenus who have been a principal for 4-9 years were the group (more than any other group)that felt tbat the workload had noticeably increased but also felt the highest pres.sure being aprincipal (39%).

Whilst themajorityofrespondentsexpresssatisfaction with their role tbey also indicate thatthe aspects of leadership tbat they felt to be tbe most important (strategic 73% andeducational/curriculum 70%) for their school community, were least demonstrated in reality(21% and 14%), However principals indicated that their ideal balance of activities was in concertwith a system perspective. This mis-matching of what principals actually do compared to whatis viewed as both appropriate (from a system perspective) and ideal (from the principals'perspective) demands further investigation if future principal positions are to be effectivelyfulfilled.

Indeed the researcb as reported here indicates a real frustration emerging from processesimplemented under Tomorrow's Schools. Whilst the majority of principals claimed to he satisfiedwith being a principal, tbere was real dissatisfaction encountered through managing the continual

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 4 5

interventions of the Ministry of Education. This is summarized by the following comments fromprincipals:

Work overload is primarily a product oj the compliance accountability process JromMimsiry of Educalion, New Zealand Qiialijications Authority (NZQA) and Education ReviewOfjia- (ERO).

I amjrusirated hy the volume oja range of non-professional requirements, constant change inlegislation, curriculum and qualificationfi.

One can be well organized, all tasks planned and then something happens which is crucial, like animmediate requirement for the Ministiy and the day (ums to custard.

Ludicrously unrealistic views from Ministry, Special Education Services (SES) and NZQA on whatis manageable.

These comments illuminate issues that beg analysis by those in the education system and itsrelated pohcy-makers. There arc clear messages given here from practising principals, who notonly wish lo be effective professional leaders and enjoy their role as such, but also wish to maketransparent their concerns as to the more dysfunctional aspects of both their role alignment (thedifference between real and the ideal) and iheir relationship with government departments andtheir demands. Some of the respondents were referring to the new managerial requirements ofthe Ministry and other educational bureaucracies which Sullivan (1998) sees as resulting fromthe pace of change that forces the educational role to lake the back scat, as "the New Right reformshave introduced generic managers instead of professionals" (p. 119).

In addition, Baker and Dellar (1999) confirm that the principal's leadership skills now needto be significantly more complex due to increased demands from multiple stakeholders,compared to when the school principal used education department guidelines and could overridethe advice of staff, community and students. However they also assert that issues confrontingprincipals should not be interpreted as evidence that current system-wide change has createddysfunctional work overload for principals for many of the issues are simply concerns typicallyassociated with the complex role of the busy school administrator.

Throughout the project it is evident that there is a tension between professionalism andmanageriatism (Boyle 2000) as tbere has been a strong recognition by principals that bothleadership and management skills were required in the course of their daily work. In concert withthis acknowledgement, comments from tbe open-ended questions revealed that the dominantstrengths that were brought lo the role included skills oi decision-making, multi-tasking,innovation and passion for young people and their achievements.

As the role of the principal bas changed to encompass more diverse responsibilities so thereare increased demands for appropriate forms of professional development. Such opportunitieswere seen as vital by the principals and stakeholders, with comments extracted from the datasuggesting the following:

It is essential to attend PD opportunities and the principal network to reduce professional isolation.

There is a lack ofprofessic nal development for aspiring principals.

4 6 lSr:A-V(i(mnc3I.Num/)(Ti,2003

There needs to be mentoring of Year 1 and 2 principols.

We need (raining before starting the job and regularly through the first couple of years.

Orientation programmes are essential with support networks for regional consistency.

The preferences for professional development included areas of financial management, bestpractices (including managing change for self and others, efficient management and best practicecurriculum options) and school culture issues (includitig cultural change managetnent and bettercross-cultural understanding). These responses support the principals' acknowledgement of thetwo .strands of leadership and management heing integral to their role. Many responses alsoindicated that support from the Ministry was often lacking and that despite the initiative for trainingfor new principals (impletnented by the Ministry since this data was collected) there was noorficialty provided professional development for the areas as identified.

One of the main challenges for the profession is"finding people who are able and willing toreplace principals when they retire". One interviewee was adamant that new principals have to hementored before heing appointed so ihai they learn through a type of internal professionalapprenticeship.

There was a strong consensus that professional development is necessary at all stages of beinga principal and no less before the job begins. Such training would enhance skills identified ashandling public relations, financial management, property, resourcing, staff management andchange management. Such skills are identified in the Endings of this research as underpinning thecompetencies required of principals,

In New Zealand, the Ministry of Education initiated training for new principals from 2002. Thetraining is based on a framework of competencies identified as essential for effective principalshipwith a focus on improving learning outcomes. This is in line with Black (2000); Hausman et al.,(2000);McConchie. (2000); and Ornstein (1993), who all present strong arguments for educationalleaders to have a range of competencies suited to the educational context. However Williams andHarold (1997) believe that leaders have been forced to pick up too many managerial respotisibilitiesand Goetis (1998) warns of too much dependence placed on professional development for whilethere is "a crush of expectations" for principals (p. 103) with confliets arising from high stress, lowrewards, tangled dilemmas and constant controversy, expectations are as varied as the groups thathold them, it has been asserted that it cannot be assumed that skill training will equip principalsfor their role for "conflici and managing multiple systems are facts of life for principals" (Goens,1998, p. 110). The provision of professional development that supports on-going professionaldevelopment therefore seems a realistic expectation lor educational leaders.

ConclusionSecondary principals in New Zealand are grappling with a complex and often conflicting role butstill they indicate, not only a continuing passion for the job, but also illustrate significant effortsto manage externally initiated demands in a way that is appropriate for iheir particular school,As a principal's leadership is essential lo initiate and sustain school improvement efforts, anyreview of educational reform requires more attention focused upon the relationship betweenschool practices and the "web of ideological, economic and social relationships" (Angus 1989,p. 88) in which the principal works.

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 4 7

The future shaping of the principalls role is paramount in long-term strategy building for "asmore decisions arc devolved to schools, ihe dilemmas of restructuring will hecome more acute"(Wildy & Louden, 2000, p. 183). In effect:

The school restructuring movement has had an impact on the knowledge, skills anddispositions required of school leaders. Principals are expected to share their power vt'ithother members of the school community: to he more democratic, collahorative andparticipative. At the same time, principals are under more pressure to provide clearleadership, to guarantee the efficiency of school management processes and to be moreaccountable to external stakeholders and authorities.

Wildy & Louden, 2000, p, 182

This role complexity has been highlighted by the findings of this research project that mirrorsissues explored in recent literature. In particular, there has been exposure of the tensionsexperienced by principals as they "act as mediators between government policy and their staff,but as agents between the school and its 'clientele' " (Moore et al., 2002). Moore et a l , alsoobserve that, with continual reforms, principals have had to re-identify themselves in a way thatcombines both "headmasterly traditions" and the "social democratic" tradition of the bureauprofessional (2002, p. 178). This reflects the shifts in the traditional educational leadership rolethrough conforming lo market values and externally-initiated policy changes.

Lack of role clarity and consistency are issues of concern for ali the respondents, whoexpressed their frustrations at the continual need to cope with often contradictory demands,while maintaining institutional and visionary stability. This is reinforced hy Robenstine (2000).who believes that principals experience managerial challenges as well as dislocation anduncertainty, while Sullivan (1998) asks whether the principal can actually do both jobs effectivelyor if there is a need for continual reform adjustments to compensate for, and correct, theimbalances and mistakes. Further disquiet is expressed by Murphy and Haliinger (1992), whonote the resulting sense of schizophrenia that accompanies the simultaneous efforts of centra!agencies to both decentralise and yei hold on to authority. These questions and viewpoints havea resonance with the principals' opinions as voiced through this research.

While this paper focuses on the data received from ihe New Zealand principals it is worthyof note here that Findings from the Queensland principals echoed those from New Zealand inmany areas, particularly in the high proportion of principals being satisfied with their role. Therewas also a similarity in terms of the tensions and dilemmas surrounding the aspects of leadershipand management. However there was a significant difference in the focus placed on theimportance of being an effective manager, with Queensland principals placing far less importanceon this aspect of their role. This lesser emphasis for Queensland principals probably reflects thegreater devolution of responsibility and accountability for managing budgets and resources forNew Zealand principals compared to those in Queensland. There was also signifieant agreementin both localities on the skills and competencies needed by principals in schools, resulting insimilar suggestions for professional development. Further comparison of the role of the principalin both New Zealand and Queensland has been examined in the context of differing models ofgovernance (Cranston & Billot, forthcoming).

Currently there is a concern in New Zealand in both retaining and recruiting principals andproviding the necessary professional support, both in terms of training and developmentopportunities, to sustain new and experienced principals In their roles. Furthermore if

4 8 ISEA • Volume 31. Numlicr I, 2003

professional development focuses upon management and administrative skills to support thisshift in focus to the principal's role does this squeeze educational leadership to an even lowerpriority? If this is not the desired outcome, then should there be more resourcing foradministrative staff to support the managerial functions of principalship? Perhaps the real focusshould be on examining the coincidence or conflict in practice relative to reform objectives?

NotesThe decile indicator syslem was developed by Ihe Ministry of Education (in 1995) to identify schools deseiving more central funding and incorooratesinformalion about the ethnic mix of Ihe school students and five socio-economic characteristics. These consist of levels of household income,percentage of parents with no school qualifications, parents receiving income support and parents In lower occupational grcHjps and average personsperbedroom. These variables are weighted and ihe total assigned to tbe schools as a decile ranking (from 1 (or the lowest to tO for the highest) Thisinformation was sourced from Fiske and Ladd (2000).

•NCEA (National Certificate of Educationai Achievement) is ihe new system of assessment introduced at years 11 and 12 from 2002.

ReferencesAngus, !„ (1989). New Leadership atid the Possibility of Educational Refonn. InJ. Smyth (Ed), CriiicalPtTsj)t'c[rvfs on Educational Leadership. London; The Palmer Press, pp 63-92.

Baker. R. G,, &DelIar, G. (1999). If It's Not One Thing It's Another Issues of Concem to Sehool Principals.]nten\aiiona} Studies in Educational Administration. Vol. 27, 2 ppI2-2t.

Black. S. (2000). Finding Time to Lead. American School Boardjournal. September, pp 46-48.

Blase, J., &:B!a5e.J. (1997), The Fire JsBack! Principals Sharing Schoo] Governance. Califomia: Sage.

Boyle, M. (2000) The 'new style' principal; Roles, reflections ant! reality in ihe self-managed school. ThePractising Administrator, 4, pp 4-7.

Caldwell.B.J. SrSpinks, L. M. (1992). Leading the Self-Managing School. London; Fahner.

Codd.J. (1993). Managerial ism, Market Liberalism and ihe Move to Self-Managing Schools in New Zealand. inJ,Smyth, (ed). A Socially Critical View oj the Self-Managing School. London: Falmer Press, pp 153-170,

Cranston, N. (1999). CEO or Headteacher? Challenges and Dilemmas for Primary Principals in Queensland.Leading and Managing. 5, 2, pp 100-113.

Creissen, T. & Ellison, L. (1998). Reinventing school leadership-back lo the fuiurc in ihe UK? internationalJaitrnal of Educational Management, 12, 1. pp 28-38.

Dimmock, C , & Walker, A. (2000). Giobalisaiion and socielal culture: Redefining schooling and schoolleadeiship in the twenty-firsi century Compare, Vol 30, 3, pp 303-312.

Education Review Office. (1994). Effective Governance: School Boards of Trustees. 'National Education EvaluationReport. 7, Winter. Wellington: ERO.

Eiske. E., & Ladd, H. (2000). W'Ttrn schools compete: A cautionary tale. Washington: Brookings Institute.

Ftillan, M. (1998). Breaking the Bonds of Dependency Educational Leadership, April pp6-10.

Gocns, Ci. A. (1998). Too Many Coxswains: Leadership and Principalship. NASSP Bulletin. October, pp 103-110.

Goss, J, D., & Leinbach, T. R. (1996). Focus groups as alternative research practice: experience withtransmigrants in Indonesia, Area, 28, 2,1.pp 115-123.

Gurr, D. (1997), Principal Leadership; What Does it Do, What Does It Look Like? Department of EducationPaiicy and Management, University of Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved December 10 2000 fromhttp:/wvi'w.apcen tre.edu.au/respapers/gurd. html

Hallinger, P. 6r Hausman, C. (1994). The changing role of the principal in a school of choice. In Murphy,), &Hiillinger, V. (Eds) Restructuring schooling: Leaming/rom ongoing efforts. Newbur^' Park, Corwin Press, California,

PRINCIPALSHIP MATTERS 4 9

Harold, B., Hawksworth. L., Mansell. H., & Thrupp, M. (2000). Self Managemem: The Experience of New ZealandPrincipals, (online) from hup;//www.icponline.org/feature_articles. Retrieved September 12 2000,

Hausman.C. S., Crow. G. M., &rSperr>; D.J. (2000). Portrail of the "Ideal principal": Context and Self. NASSPBulletin, Vol. 8f, 617 pp5-H.

Johansson, O., &r Lundberg, L. (2000). Changed Leadership Roles in Swedish School. Presentation to the NZEASConference. Hobart, September.

LetlKwood, K., & Menzies, T. (1998). Forms and effects of school-based management: a review, EducationalPdlicv, 12, (3). pp 325-346.

Lovegrove. G. (2001). Focus on the Big Issues. NZ Principal. March, 16, 1, 3.

McConchic, R. (2000), Challenges for Educaiional Leadership in the 21st Centur>- ICP Online downloadedm/09/00 ww\v.icporiline.org/feature_artlcles.

Minisier of Education. (1988). Tornonuw's Schools. Wellington: Government Printer.

Ministr>' of Education. (2002). About the Ministry of Education: Our Mission, Our Purpose, www.minedu.govt.nz,

Moore, A.. George, R., & Halpin. D. (2002). The Developing Role of the Headieacher in English SchoolEducaiional Management and Adminisiration, Vol 30, 2, pp 175-188.

Murphy.]., & Hallinger. P (1992), The principalship in an era of transformation. JouiTialo/EducationalAdminisiralion, 30 (3), pp77-88.

Ornstein, A. C. (1993). Leaders and Losers: How Principals Succeed, Educaiion Digest. Vol. 59, 4, pp27-31.

Portin, B. S., Shen,J. & Williams, R. C. (1998). The Changing Printipalshipand its Impact: Voices fromPrincipals. NASSP Bulletin, December, ppl-4.

Robenstine, C. (2000). How school choice can change the culture of cdut:alional leadership. ContemporaryEducation. Vol. 71, 2. pp26-30.

Sullivan, K. (1998). Principals wiih Principles: A Crisis of Leadership in New Zealand Education. In Ehrich, L.& Knight, J. (Eds.) Leadership in Crisis.'Rcsfrucdiringprincipied practice. Essay's OH Cofi(cmptirar>'Ei(ucutio(iaJLcadtrsiiip. Wilby Flaxton, Queensland, Australia, pp 112-120.

Wildy, IL, & Louden, W. (2000). School Restructuring and the Dilemmas of Principals' Work. EducationalManagement cirid Admiiii.'i(r«(ii>M. Vol. 28, 2. pp 173-184.

Williams, R. C, & Harold, B. (1997). Sweeping Decentralisation of Educational Decision-Making Authority. PhiDelta Kappan, 78. 8. pp 626-632,

Wylie, C. (1997). Sel/-managing StJiools Seven Vears On; What have we Learnt? NZCER Wellington.

AuthorDr Jennie BillotDirectorCentre for Educational Research and DevelopmentUNITEC Institute of TechnologyPrivate Bag 92025AUCKLANDNEWZE.\L.'\ND

Ph: 6498154321 .s7465Fax: 64 9 8154310Email: [email protected]