Et-Tell is Not Bethsaida

Transcript of Et-Tell is Not Bethsaida

Et-Tell Is Not BethsaidaAuthor(s): R. Steven NotleySource: Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 70, No. 4 (Dec., 2007), pp. 220-230Published by: The American Schools of Oriental ResearchStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20361336 .

Accessed: 04/04/2013 12:31

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The American Schools of Oriental Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extendaccess to Near Eastern Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Et-Tell is .A/of Bethsaid R. Steven Notley

One of the challenging tasks for archaeologists and

biblical historians alike is the identification of sites

mentioned in the Bible, many of which were destroyed and disappeared in time without a trace. Such seems to have

been the fate of one town mentioned in the Gospels. Bethsaida

was lost for centuries, and its location the subject of speculation

by pilgrims and mapmakers alike (McCown 1929:32-58). With the advent of geographical exploration of the Holy Land

in the nineteenth century, the search intensified in the northern

regions of the Sea of Galilee. Two theories advanced at that

time still dominate the debate today. Edward Robinson followed Richard Pocockes suggestion that et-Tell?the location of the

present-day Bethsaida Excavations Project (BEP)?was the

site of ancient Bethsaida-Julias (Robinson and Smith 1867,

2:413-14)> Later, the German explorer Gottlieb Schumacher,

noting the problem of et-TelVs distance from the lake, proposed an alternative site for Bethsaida at el-Araj and distinguished it

from the site of Julias (Schumacher 1888:93). "Is it not possible that el-Araj marks the fishing village [i.e., Bethsaida], et-Tell, on the other hand the princely residence [i.e., Julias], and that

both places were closely united by the beautiful roads still vis

ible?" (Schumacher 1888:246).

Although it has never been excavated, Mendel Nun of Kibbutz 'En Gev still maintains that el-Araj is the possible site of Bethsaida (Nun 1998:12-31). Contrary to BEP director

Rami Arav's repeated assertion that "El-Araj is a ruin dating

from the Byzantine period only" (Arav 2006:150), a 1991

survey of el-Araj conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority found early-Roman-period surface remains that correspond

with Schumacher and Nun's identification:

Ancient building remains were recorded north and northwest of the

hill and sherds were collected from the Early (including a Herodian

lamp and terra stigillata bowl) and Late Roman periods. These finds

indicate that el-Araj's identification with Bethsaida cannot be

excluded. (Stepansky 1991:87; cf. Urman 1985:121; Urman and

Flesher 1995:522-24)

Over the past decade, the debate between these two opinions intensified on the pages of scholarly journals. Although Nun is widely considered one of Israel's leading authorities on the Sea of Galilee, editors of his article in Biblical Archaeology Review excised his localization of Bethsaida at el-Araj (Nun 1999:18-31, 64; cf. 1998:12-31). Less than six months later, the same journal published an article by the BEP excavators

championing the localization of Bethsaida at et-Tell (Arav, Freund, Shroder 2000, 1:44-51, 53-56). Today, the debate seems a foregone conclusion. Et-Tell is identified on Israel

government maps and road signs alike as Bethsaida.

Yet, have twenty years of excavations at et-Tell demonstrated

beyond reasonable doubt that it was the site of ancient Bethsaida?

Nagging questions remain. True, it is rare that archeology can

prove with absolute certainty the identity of a particular site. Recent exceptions are TeLMiqne (Ekron) and Tel el-Qadi (Dan), where inscriptions found at those sites identified them as

the ancient biblical cities. More often, however, the task of site identification is a complex application of multiple disciplines, including history, toponomy, topography, and archaeology (Rainey and Notley 2006:9-24; Rainey 1984:8-11). While there are limits to the certainty of conclusions

based solely on archaeological excavations, they can serve in

another way, that is, to eliminate mistaken identification. If

multiple, independent, and reliable historical sources indicate human activity during a particular period, and archaeological

investigations on a site find no corresponding material remains

that correlate to that historical period, then the paucity of the evidence should raise questions about the presumed identity of the site. In this brief study, the line of approach is simple.

We will examine the historical descriptions of Bethsaida by those who knew it firsthand in late antiquity and compare this ancient portrait of Bethsaida with the discoveries from the recent excavations at et-Tell.

220 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007)

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

_p^*.4*, *^?4to?t??#tg

''*m0m&B~

'?' - .ii7?;.s^?s:?'^:.tsi,*'l?^??:-;

,^?hw^^i^'*yT^wf

???ais- -&*???\r*

*T it% . ^^

aK?S?-.* < - -

-i?w*

#&

m>

.^ ^?

- * < ' ...-/V%. 5- ** *&V"

At?UM* ^^^-^^jv"

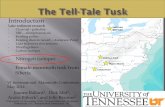

Aerial view of et-Tell looking south towards the Sea of Galilee. Between the tell and the lake lies the plain of Bethsaida, which separated it from

the lake in the days of Herod Philip just as it does today. The elevation at the base of the tell and its distance of three kilometers (1.5 miles) from

the water are natural impediments to et-Tell being identified with the first-century fishing village of Bethsaida. Photo by Duby Tal, Albatross.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007) 221

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is There a Roman-Period Component at El-Araj? While Kami Arav has asserted that the site of elAraj is only Byzantine in date (Arav 2006:150), others,

such as Dan Urman and Paul Flescher, who surveyed this site for the Israel Antiquities Authority, have

reported a variety of Roman-period ceramic

materials on the site (1985:522-24). Anyone who walks over this site today can see a wide

variety of architectural fragments sitting on its

surface. Many of these unstratified fragments could easily date to the Roman period. Note

a variety of basalt ashlar masonry and a

threshold, as well as limestone columns, column bases, capitals, and a frieze with egg and dart design.

A limestone heart-shaped double column.

Limestone column base from El-Araj, now located at Ein Gev Kibbutz.

A basalt threshold with doorhinge socket

An embossed basalt

stone. Photo by Joel $.

Fishman courtesy Jerusalem

Perspective. A beveled ashlar.

A limestone frieze with egg and dart design, now located at

Ein Gev Kibbutz. A basalt ashlar.

222 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007)

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A Fishing Village Without Water? Two insuperable problems challenge the site identification

of Bethsaida at et-Tell. First, from the time of Schumacher, et-Tell's distance from the Sea of Galilee has been

acknowledged as a natural impediment to its being Bethsaida. Both the New Testament and Josephus describe Bethsaida as situated on the lakeshore. Its very name means "place of fishing," and its reputation in rabbinical literature of the second and third centuries CE remained closely identified with the fishing industry. The location of et-Tell is about one and a half miles (3 km)

from the lake, an unlikely isolated setting for a fishing village. To overcome this challenge, the excavators theorized that et-Tell's current remoteness is the result of geological cataclysms and the

silting of the Jordan River. According to a geological study of the area provided in the first (Shroder and Inbar 1995:65-98) and second (Shroder et al. 1999:115-74) excavation reports, the Bethsaida plain was underwater at some point between 2700 and 1800 years ago (Shroder et al. 1999:167). While these studies are extensive and informative, their conclusions fail to demonstrate the particular relevance of this nine-hundred year span to our narrow window of historical interest in the early Roman period, particularly during the tetrarchy of Herod Philip (4 BCE-34 CE).

Moreover, surveys of known first-century harbors around

the Sea of Galilee provide verifiable and objective data for the levels of the lake in the New Testament period. The present lake level averages 690 feet below sea level (-210.5 m). Mendel

Nun suggests that its level today is about three feet (one meter) higher than in antiquity because of a modern-day dam that has raised the water level. The measured elevations of breakwaters and piers that belong to the sixteen first-century harbors around the lake support his contention (Nun 1991). On the other hand, basalt blocks identified by the BEP

excavators as et-Tell's "old dock facility" at the base of the tell are reported at an elevation of -669 feet/-204 meters (Shroder and Inbar 1995:86). This is over twenty-two feet (seven meters) higher than the first-century lake levels. If the BEP excavators are correct and the lake reached what they claim was the docking facility of Bethsaida, then the lake would have inundated the shoreline promenade at Capernaum (-686.5 ft.A209.25), the ports of Tiberias (683.4 ft./-208.30 m), and Kursi (-686.5 /-209.25), and every other known first-century settlement around the lake.

So, even if a catastrophic geological event at et-Tell could be determined more precisely to fall between the first and fourth centuries, it would not eliminate the topographical obstacle for

locating Bethsaida at et-Tell. The BEP excavators* identification

w^P&

In this Hellenistic-period dwelling at et-Tell?one of two large private homes excavated from this period?the excavators found implements that

they believed were used in the fishing industry, and hence the structure is known as the "Fisherman's House." All photos by the author unless

otherwise indicated.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007) 223

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

necessitates not only that the Sea of Galilee extended to the

base of et-Tell, but because of the site's elevated position, they

require that the level of the lake rose to the base of et-Tell.

Such a feat is implausible in light of the known first-century lake levels. The lake cannot have reached et-Tell, because the elevation of "the old docking facility" at the base of the mound is far too high. Our topographical observations concerning the plain

separating et-Tell and the lakeshore are consistent with

Josephus's eyewitness account that the plain was the location

of fighting between the Jewish forces that he led and troops under the command of the Roman Sulla (Life 399-406).

Josephus's horse stumbled on the marshy land and fell, injuring its rider. He escaped only to surrender a short time later in

Jotapata (J.W 3:316-339). Heinz-Wolfgang Kuhn, a member of the BEP team, has rightly read the topographical implications of Josephus's description for the skirmishes between his forces

and those of Agrippa II. Josephus's unit encamped near the

Jordan River and its advance "as far as the plain" (u?XPl too

tte??od), "presupposes the plain between et-Tell and the sea, so

that the sea at the time of Josephus did not by any means reach as far as et-Tell" (Kuhn and Arav 1991:81). The consequences of Kuhn's reading are not insignificant. The challenges raised in the nineteenth century because of et-Tell's remote setting have not been answered by the BEP excavators. The historical and topographical evidence indicates that et-Tell lay a

considerable distance from the lakeshore, an unlikely location for a renowned fishing village.

A Shortage of Early Roman Remains Equally challenging is the stark absence of material remains

from the early Roman period. We begin first with a sketch taken

from the reports of those who knew Bethsaida-Julias firsthand, and then we will give thought to the excavation results. The

earliest historical references to Bethsaida are those found in the New Testament. It was one of the Galilean cities where Jesus ministered. Here Mark records that Jesus healed a blind man

(Mark 8:22). It is also to this vicinity that Jesus withdrew on more than one occasion: "On their return the apostles told him

what they had done. And he took them and withdrew apart (that is, by boat: Mark 6:32) to a city called Bethsaida" (Luke 9:10; see also Mark 6:45).

A brief remark is warranted concerning the anachronistic

toponym, Bethsaida of Galilee in the Fourth Gospel (John 12:21). The unfortunate designation has been the genesis of futile searches for a western Bethsaida and even two Bethsaidas

(Robinson and Smith 1867, 3:358-59; Pixner 1985:207-16). Yet, the regional qualifier should be read only as a toponymie marker for the historical period of the Evangelist. Literary parallels for this anomaly can be witnessed in both biblical and non-biblical literature.1

Changes in first-century regional terminology may have followed the consolidation of political power by Agrippa I or Agrippa II on both sides of the upper Jordan River, or, as

seems more likely, resulted from geopolitical changes by the Romans after the Jewish Revolt (66-70 CE). Later, the first

century Roman writer Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. 5.71) and the Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy (Geog. 5.15.3) join the Evangelist in speaking of territory east of the Jordan River as Galilee. The region of Galilee no longer marked the frontiers of political power on the western side of the upper Jordan River.

Nonetheless, these ensuing developments in no way reflect the

toponymie or geopolitical realities in the days of Jesus. During the rule of Antipas and Philip, Bethsaida was not in Galilee.

Outside of the New Testament, our most abundant witness for

first-century Bethsaida is that of Josephus. He includes the city in

his description of the course of the Jordan River that "traverses another hundred and twenty furlongs (i.e., fifteen miles beyond Lake Semechonitis), and after the city of Julias cuts across Lake Gennesaret" (J.W 3:515). Of Herod Philip's efforts at Bethsaida,

Josephus reports, "He provided the village of Bethsaida on lake Gennesaret with the dignity of a city, by increasing the multitude of its inhabitants and by the other honor of naming it Julias, the same name as Caesar's daughter" (Ant. 18.28).

Josephus's testimony is the only record that Philip renamed the village of Bethsaida as Julias, although Pliny (23-79 CE) and

Ptolemy (ca. 150 CE) were also familiar with a city named Julias in the vicinity. Josephus is also alone in his reference to the

daughter of Augustus together with the new name for Bethsaida. Much has been written about the identity of this woman in

Josephus's report (see Strickert 2002:27-34). Julia, the daughter of Augustus from his marriage to Scribonia, was banished in 2 BCE to the isle of Pandateria (Suetonius, Aug. 65; Tacitus, Ann.

1.53; Dio Cassius 55.14). It is doubtful that Philip would have

begun his initiatives at Bethsaida already in the first two years of his rule and during the same time he was constructing the new

city of Caesarea Philippi at Paneas (contra Sch?rer, Vermes, and Millar 1979, 2:172). It is likewise difficult to imagine the tetrarch

dedicating the city to Augustus's daughter after her exile. On the other hand, Livia, the second wife of Caesar Augustus,

was adopted into the Julian family in the emperor's will, which was executed at his death in 14 CE (Tacitus, Ann. 1.8; Dio Cassius

56.46). She was thereafter officially known as Julia Augusta. E. Bartman (1999) has cataloged the inscriptional references to the empress and traced the transition of Julia's appellations during the successive phases in her life (Augustan era [31 BCE-14 CE], Tiberian era [14-29 CE], Posthumous [post-29 CE]). She is predominantly called "the wife of Augustus" during the Augustan era, and "the mother of Tiberius" during the

years of her son's reign. Neither of these two was applied to

Julia Augusta after her death in 29 CE. Instead, we find two

epigraphs after her death that refer to her as "the daughter of Augustus." These trends are consistent with the report of Velleius Paterculus in his History of Rome.

Take for example Livia. She, the daughter of the brave and noble Drusus

Claudianus, most eminent of Roman women in birth, in sincerity, and

in beauty, she, whom we later saw as the wife of Augustus, and as his

priestess and daughter after his deification. (2.75.3)

224 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007)

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Accordingly, Strickert advances the theory that it is not by chance that Josephus refers to the empress as "the wife of

Augustus," when describing the founding of another city in her honor in the transjordan (Betharamptha-Julias) in 13 CE, still in the Augustan era (see Josephus, A.J. 18.27; Jones 1937:275, 277). With equal appropriateness, he then entitles her "Caesar's

daughter" in his account of Philip's efforts at Bethsaida-Julias. The final epithet suggests that the new city north of the Sea of Galilee was founded after Livia-Julia's death.

The timing of Philip's initiative at Bethsaida-Julias may be attested further by the discovery of coins of Philip minted at Caesarea Philippi. One bears the image of Julia Augusta and is inscribed with her Greek title, IOYAIA ZEBAZTH (Julia Sebaste). The coin is dated to the thirty-fourth year of Philip's rule, which was 30/31 CE. Another coin minted in the same

year bears the image of Caesar Tiberius on the obverse and the Herodian Augusteum at Paneas on the reverse. What is

especially significant about this second coin is that it is inscribed

A small denomination coin of Herod Philip minted in 30/31 CE. After

a break of thirty years, Philip once again issued coins with his own

portrait on them. Only his name FILIPPOU ("of Philip") appears without

the designation "tetrarch." On the reverse a wreath and the date "year 34" appears. From Hendin (2001 :no. 541). Reprinted by permission.

A medium denomination coin of Herod Philip depicting Julia Sebaste

minted in 30/31 ce likely to mark the founding of Bethsaida-Julias.

On the obverse is the ?mage of the wife of Augustus with her title

SEBASTH. On the reverse is a hand holding three ears of grain. Instead

of Philip's name, it reads KARPOFOROS (fruit-bearing). This ?mage is

repeated at the mint of Paneas by the later Herodians, Agrippa I and

Agrippa II. From Hendin (2001 :no. 540). Reprinted by permission.

KTIZ, an abbreviation for KT?rjTr|? (founder). Meshorer

(2001:88) has embraced Strickert's idea (2002:65-91) that both these coins commemorate the founding of Bethsaida

Julias by Herod Philip in 30 CE, a year following the death of the empress.

So, while Josephus wrote in Jewish Antiquities that Bethsaida

Julias shared the same name as Caesar Augustus's daughter, he meant Julia Augusta, wife of Augustus and mother of Tiberius

(Grether 1946:222-52). This reading concurs with Josephus's earlier written account for Philip's founding of Bethsaida-Julias in which the empress is mentioned, but the estranged daughter of Augustus is not:

On the death of Augustus, who had directed the state for fifty-seven

years six months and two days, the empire of the Romans passed to

Tiberius, son of Julia. On his accession, Herod (Antipas) and Philip

continued to hold their tetrarchies and respectively founded cities:

Philip built Caesarea near the sources of the Jordan, in the district

of Paneas, and Julias in lower Gaulanitis (i.e., Bethsaida-Julias);

Herod built Tiberias in Galilee and a city, also named Julias, in

Peraea (i.e., Betharamptha-Julias; J.W. 2.168).

Philip died in 34 CE at Bethsaida-Julias. According to Josephus, "he died at Julias; and when he was carried to that monument, which he had already erected for himself beforehand, he was

buried with great pomp" (Ant. 18.106-108). Strickert claims that Philip's mausoleum was at Bethsaida-Julias (1998:89; cf. Robinson and Smith 1867, 2:413), but this detail is stated nowhere in Josephus's report. Josephus's reference to the location

of Philip's death and subsequent mention of his burial need not

indicate any proximity in distance between the two sites. The death of Philip's father, Herod the Great, in Jericho and his burial at Herodium, as described by Josephus, illustrates this point (cf. J.W. 1.670-673). Josephus does not inform us of the location of

Philip's tomb, and its whereabouts remain unknown.

The portrait of Bethsaida-Julias we glean from the historical eyewitnesses is at stark variance with the results of the archaeological efforts at et-Tell. The latter indicates that et-Tell was a significant fortified city in the Iron Age (Arav 1995:193-202). The archaeologists suggest it belonged to the

kingdom of Geshur (2 Sam 3:3). A monumental gate complex faced east and was discovered together with cultic stele and a basalt basin adjacent to the gate (see photo p. 226). The

Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III probably destroyed the city in

his invasion during the eighth century BCE (Arav 2006:165). There is evidence of renewed settlement during the Persian

period with a continuity of occupation into the Hellenistic

period. Yet, these material remains from earlier occupation levels

stand in marked contrast to the Roman period. According to

the BEP report by Fortner on Hellenistic and Roman fineware from et-Tell (1995:99-126),

the general time span for dating [fineware at et-Tell] ranges from

200 BCE to 100 BCE, and rarely to the first century BCE ... A decline

in the number of fineware from the first century CE is obvious. The

main evidence for fineware dates from the second and beginning of the

first centuries BCE. (Fortner 1995:106-7; my emphasis)

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007) 225

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The discovery of amphorae in this storage room belonging to one

of the two large Hellenistic-period dwellings at et-Tell led to the

excavator's dubbing the house the "Wine Grower's House."

Et-Tell was a significant fortified city in the Iron Age. The entrance

to the Iron Age gate complex seen in this photo was flanked by two

stele. Note the raised cultic basin on the right.

Fortner's observations are consistent with the ceramic typology

given in the second volume of the excavation report (Arav 1999:31-83). The totals from the detailed tables of ceramic finds from areas A and B are as follows: 296 vessels from the Iron Age, seventy-one Hellenistic and fifty-three Roman.

The decline is even more pronounced, if one removes from consideration the remains from area A that we are told are

comprised entirely of a pit filled with composite pottery. The distribution then is 294 vessels from the Iron Age, fifty-one Hellenistic and thirteen Roman.

Kindler's BEP excavation report about coins found at et-Tell is likewise compelling and points us in the same direction as

the ceramic evidence (Kindler 1999:250-68). According to Kindler there were 105 coins found minted in the Hellenistic

period (333-63 BCE); nine Herodian (Herod I [1]; Antipas [1]; Archaelaeus [1]; Philip [3]; Agrippa I [1]; Agrippa II [2]); sixteen Middle to Late Roman; four Byzantine; sixty-four Islamic (Ummayad to nineteenth century).

Fortner's remark regarding the dramatic decline in fineware is characteristic for the pottery, coins, and structural remains

and indicates a visible decline in all aspects of material culture at the beginning of the Roman period. So, while two large Hellenistic private homes are prominently displayed (see Arav and Freund 1995:26-32), only one small, poorly attested Roman period house is presented in the excavation reports.

This meager state of affairs in the Roman period at et-Tell stands in irreconcilable conflict with the historical picture of

Bethsaida-Julias in the first century of the Common Era, when

Josephus reports the city at its zenith in size and prominence. It is precisely at this point in history that Josephus records that

Herod Philip initiated efforts at the Jewish fishing village to

provide it the dignity of a Greco-Roman polis. To date there exists little if any published evidence of these

efforts attributed by Josephus to Philip's improvement of the

city. Neither is there any identifiable structure from what one

would expect of a Roman polis (cf. Tcherikover 1972:33-39; 1975:90-116). The awarding of polis status upon a city was

intended to introduce elements of Greco-Roman culture into Near Eastern societies. One might have expected to see some evidence of a theater (as at Tiberias and Sepphoris), hippodrome (as at Sebaste and Caesarea), or other elements of Roman life introduced into Bethsaida-Julias.

We should quickly add that historians may be correct that

Josephus has exaggerated the extent of Philip's efforts. In their

estimation, Julias never was a real polis (see Jones 1937:283; Smallwood 1981:116 n. 45). These hesitations notwithstanding, even if Josephus has embellished the size and significance of

Bethsaida-Julias, this does not explain away the near absence of material remains at et-Tell during the tetrarchy of Herod Philip. Remarkably, the excavators make no attempt to reconcile the

drastic decline in material remains at et-Tell in the early Roman

period with the historical descriptions of Bethsaida-Julias. After

twenty years of excavations, the only structure of any significance that the excavators can point to is the foundation of what some?

but not all?of the excavators suggest is a Roman temple.

226 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007)

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The putative Roman-period temple to Julia Augusta is situated north of the Iron Age gate complex at et-Tell. Its meager size and rough construction have raised questions even among some of its excavators concerning its identity as a temple to the mother of Caesar Tiberias.

A Temple for Julia Augusta? Arav has ventured that with Philip's founding of Bethsaida

Julias, he included the transformation of a house into a modest temple to serve the local cult of Julia Augusta (Arav 2006:162-64). Evidence of a cult to Julia Augusta in the east in this period is rare (Grether 1946:241). It is well known that

Tiberius discouraged the imperial cult of himself and his mother

(Tacitus, Ann. 4.37). Moreover, Arav's suggestion that Philip's construction of a temple in honor of Julia following her death takes no account of the reports of Suetonius, Tacitus and Dio Cassius that upon her death Tiberius forbade the deification of his mother (Seutonius, Tib. 51; Tacitus, Ann. 5.1; Dio Cassius

58.2). She was not deified until the reign of her grandson, the

emperor Claudius, who did so to strengthen his own connection to the imperial house (Suetonius, Claud. 11; Dio Cassius 60.5). According to the excavation report, the evidence for its

identification as a temple is: (1) the relative thickness of the walls in comparison to the average thickness of other structures at the site; (2) the "rough" east-west orientation of the rectangular structure; (3) a column foundation; (4) a porch in antae in both its east and west ends; (5) rooms that the excavators identify as the possible pronaos and celia (Arav 1999:18-24).

In addition to these structural identifications, nearby were discovered an incense shovel and a clay female figurine. Some of the excavators have suggested that these two items were associated with the proposed temple and local imperial cult to Julia (Arav 1999:18). Stricken goes so far as to claim that "the discovery of the incense shovel leaves no doubt that the

relatively small settlement was a place where the imperial

cult was practiced and, at least for a time, played a dominant role" (Strickert 1998:105). Yet, as Freund acknowledges, there simply is not enough information to determine the shovel's date or to know whether it belonged to Jews or

pagans (Freund 1999:413-60). It certainly does not provide conclusive evidence on the presence of the imperial cult at et-Tell (cf. Rutgers 1999:177-98). Since there is no evidence of the shovel's actual usage, even less does it identify the

nearby structure as a Roman temple.

Concerning the dating of the structure proposed to be a

temple to Julia Augusta at et-Tell, one should keep in mind

Meyer's cautious observation on the tenuous nature of the

dating by the excavators:

The architectural units (such as the bit hilani palace, Roman temple, Roman houses, and Iron Age walls) seem to be dated by accumulated

fills and not by the material in sealed loci under surfaces. If so, the

dates suggested for the structures would be problematic, as would

the hypotheses about their identity. (Meyers 2002:85)

Supporting evidence for the identification of the structure as a Roman temple is disappointing. It lacks any of the fine work one would have expected of a temple dedicated to the empress. A small threshold stone is, "the single dressed stone that was found at the site close to the in situ position" (Arav 1999:21).

However, the excavators admit that even this stone is too small

for "a main entrance."

Ball's survey of Roman temples illustrates that et-Tell's putative temple is the only one of such rough and meager construction

(2000). The recent discovery of a Roman temple in the tetrarchy

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007) 227

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of Philip underscores this disparity (Overman, Olive, and Nelson

2003:40-49, 67). The excavators acknowledge the humble state

of affairs in their comparison between their structure and Roman

temples in the Hauran and in northern Syria: "Most are built of fine dressed stones and resemble very vaguely the building at Bethsaida" (Arav 1999:22). Arav continues, "if this is the

temple built by Philip the Tetrarch ... for the cult of Livia-Julia, then it was indeed a very modest temple in comparison with the structures that Philip's father had built at Samaria and Caesarea

Mar?tima" (Arav 1999:24). Arav, Freund, and Schroder (2000:56) have theorized that the

reason we only find the temple's foundations and no dressed stones

is because the stones were taken and reused in the synagogue of Chorazin. They cite only two pieces of evidence to support this fantastic claim. First, the width of the Chorazin synagogue

approximates that of their proposed Roman Temple at et-Tell.

Second, the excavators suggest that an eagle in a frieze from the Chorazin synagogue is evidence that it originally belonged to a

Roman structure, since the eagle was the symbol for Rome.

Their line of reasoning fails on both accounts. The width of the Chorazin synagogue is consistent with other undisputed Roman-Byzantine synagogues in the region. Thus, there is no

necessary connection with the dimensions of the foundations for the building at et-Tell. Second, as Hachlili points out, the

eagle was a common motif found in the ornamentation of

regional synagogues in late antiquity (Hachlili 1988:332-35). Indeed, Herod already included the eagle in the decorations of the Jerusalem temple (J.W 1.650-656; Ant. 17.149-63). There

simply is no evidence to support the excavator's suggestion

that the missing temple of Bethsaida-Julias is to be found in

the stones of the Chorazin synagogue. Further, the differences between the structure at et-Tell and other Roman temples in the region raises serious doubts about whether the public building found at et-Tell was indeed a Roman temple.

The Disappearance of Bethsaida In the first century CE, Bethsaida increased in prominence and

size from is humble beginnings as a small, non-descript Jewish fishing village. Yet, the circumstances of its disappearance seem as elusive as its location. Regarding Bethsaida's disappearance, Arav wrote in 1997:

In 65-66 the Roman armies of Agrippa II clashed with rebels in a series of battles that failed to result in a clear victory for either

side (Life 71-73). The archaeological evidence is that the city was

destroyed and never rebuilt. (Arav 1997:303)

He does not present any archaeological evidence from et-Tell for the destruction of Bethsaida in the Jewish Revolt. Nor is there

any evidence of a first-century destruction detailed in the first volume of the excavation report, Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea of Galilee (Arav and Freund 1995). Instead, in volume two of the excavation report, Kuhn concludes,

it is certain that Bethsaida-Julias was still settled after the Jewish

Roman war (66 to c. 74 CE). I cannot recognize any evidence either

of an archaeological nature or in Josephus' works, that Bethsaida

was destroyed in the course of the Jewish-Roman war, or even that

the city was abandoned about the year 67 CE. (Kuhn 1999:284)

Kuhn's assessment of the historical and archaeological evidence of Bethsaida's continued settlement after the Jewish Revolt concurs with Freund's study in the first volume. His study includes numerous references to Bethsaida in early rabbinical literature from the period after the revolt (e.g., Qoh. Rab. 2:11; cf. Freund 1995:267-303). To the rabbinical witnesses should be added the two pagan writers cited earlier, Pliny the Elder and Claudius Ptolemy, both of whom attest to the existence of Bethsaida-Julias after the Jewish Revolt. Together these witnesses present a strong argument that the city continued to exist at least into the middle of the second century CE (contra Strickert 1999:347-72).

Freund's observation that Bethsaida was not a city familiar to the rabbis after approximately the third century CE (Freund 1995:302) is consistent with Eusebius's description of Bethsaida in his Onomasticon (Notley and Safrai 2005). Compiled at the

beginning of the fourth century CE, Eusebius cataloged most of the cities, sites, and regions mentioned in the Old and New Testaments. Supplementing his list when possible, Eusebius

provided detailed information concerning the places' history and

location, including their distances in Roman miles from other well-known metropolitan centers in fourth-century Palestine.

At times, the brevity of Eusebius's descriptions?with nothing more than the barest details taken from the biblical text?

suggest that the location of the site was already lost by the time of his writing at the beginning of the fourth century. This seems to be the case with Bethsaida, one of the cities mentioned in connection with the ministry of Jesus (Matt 11.21; Luke

10.13). Of Bethsaida, Eusebius reports: "The city of Andrew and Peter and Philip. It is located in the Galilee next to the lake of Gennesaret" (Onom. 58.11; Notley and Safrai 2005:58). Eusebius received his information about Bethsaida from the tradition of the Fourth Gospel that it was the home of Philip,

Andrew, and Peter (John 1:44), and located in the Galilee

(John 12:21). He borrowed verbatim the detail that the village was "next to the lake of Gennesaret" from the description of

Josephus (Ant. 18:28). Elsewhere Eusebius credits Josephus by name (cf. Onom. 1.2= Ant. 1.92-95; Onom. 40.9=Ant. 1.118; Onom. 82.2=Ant. 1.147). Since Eusebius only repeats details about Bethsaida found in well-known first-century sources, and he himself supplies no additional physical description, it is likely that by his own day the hometown of the apostles had been abandoned and its location forgotten. Other deserted biblical sites?which amounted to little more than visible piles of ruins in the fourth century?are described as such by Eusebius (cf. Chorazin; Onom. 174.23). The absence of additional physical details describing Bethsaida seems to indicate that our New Testament city had disappeared entirely.

Avi-Yonah has traced evidence for a general regional decline of Jewish communities in Roman Palestine in the third century. The demise of Bethsaida-Julias was not a consequence of the

Jewish Revolt against Rome, or the more recent suggestions

of geological cataclysms. The plight of Bethsaida-Julias was

228 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007)

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

shared by numerous other Jewish settlements in Galilee and

Golan, and was the effect of political and economic crises in the Roman Empire from the death of Commodus (192 CE) to the rise of Diocletian (284 CE). During a period of only 103 years, Palestine experienced twenty-five changes in emperors.

In the first generation of the crisis (200-230) the numbers of Jewish

villages in the Golan and Bashan fell below the number of city

communities. In the second generation (230-260) the same process

appears among the Jewish communities in the coastal plain. ... In

the Galilee itself a decline can be observed only in the last stages of

the crisis (260-290). (Avi-Yonah 1976:132)

Avi-Yonah's summation presents the historical background for

the disappearance of Bethsaida, as part of an overall decline in

Jewish communities in northern Roman Palestine in the third

century, beginning with the Golan and Bashan. By contrast, the

archaeological evidence from et-Tell indicates its decline began almost three hundred years earlier, and almost a century before

the tetrarchy of Herod Philip.

What we know of Bethsaida-Julias in late antiquity through the eyes of witnesses

It was a fishing village called Bn?aa??a/ (John 1:44; or

]!"%: y. Sheqal. 50:1). Accessible by boat (Life 406; Mark 6:32), it lay on the shores of the Sea of Galilee (Ant. 18:28). It was located about 200 meters from the Jordan River,

which coursed by the settlement and emptied into the lake

(J.W. 3:515). It was situated in lower Gaulanitis, opposite the higher hill

country ?.W 2:168). Bethsaida contained both Syrian and Jewish inhabitants

(J.W. 3:57; John 1:44). In about 30 CE the tetrarch Herod Philip provided the village

with the dignity of a Greco-Roman polis by increasing its

population and by renaming it Julias in honor of Livia-Julia,

the widow of Augustus and mother of Tiberius (Ant. 18:28).

It survived the two Jewish revolts against Rome and continued

with a reputation for fishing into the third century CE.

It shared the fate of other Jewish settlements of Galilee

and Golan and disappeared in the closing decades of the

third century.

The town was personally unknown by Eusebius, the bishop

of Caesarea, at the beginning of the fourth century.

Our comparison of the ancient eyewitnesses and the

archaelogical results of the Bethsaida Excavations Project has highlighted many incongruities. The evidence of twenty years of excavations is far from conclusive in demonstrating

the claim that et-Tell was first century Bethsaida-Julias. The site's elevation and remoteness from the lake, together with

its unexplained decline in material culture at the beginning of the early Roman period, challenge the identification of et-Tell with the lost city of Philip, Andrew, and Peter. Certainly more

investigation is needed, perhaps now beyond the confines of et-Tell. In the meantime, until some modicum of compelling physical evidence can be unearthed, the toponym Bethsaida should cease to be applied to the site of et-Tell.

Notes 1. Biblical: see Gen 21:32: land of the Philistines in the time of Abraham;

non-biblical: see scholion on Meg. Ta'an 21 Kislev: the Herodian place name

Antipatris for Aphek-Pegae already in the time of Alexander the Great.

References AviYonah, M.

1975 Introduction: The Rise of Rome. Pp. 3-25 in World History

of the Jewish People, First Series: Ancient Times. Vol. 7, The

Herodian Period, ed. M. AviYonah. Jerusalem: Massada.

1976 The Jews of Palestine: A Political History from the Bar Kokhba

War to the Arab Conquest. New York: Schocken.

Arav, R.

1997 Bethsaida. Pp. 302-5 in Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, vol. 1, ed. E. M. Meyers. New York: Oxford

University Press.

1999 Bethsaida Excavations: Preliminary Report, 1994-1996. Pp. 3-113 in Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea of

Galilee, vol. 2, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Kirksville, MO:

Truman State University Press.

2006 Bethsaida. Pp. 145-66 in Jesus and Archaeology, ed J. H.

Charlesworth. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Arav, R., and Freund, R. A., eds.

1995 Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea of Galilee, vol. 1. Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press.

Arav, R.; Freund, R. A.; and Shroder, J. E, Jr.

2000 Bethsaida Rediscovered: Long-Lost City Found North of

Galilee Shore. Biblical Archaeology Review 26: 44-51, 53-56.

Ball, W.

2000 Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. London:

Routledge.

Bartman, E.

1999 Portraits of Livia: Imaging the Imperial Woman in Augustan Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freund, R. A.

1995 The Search for Bethsaida in Rabbinic Literature. Pp. 267-311

in Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea of Galilee, vol.

1, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Kirksville, MO: Thomas

Jefferson University Press.

1999 The Incense Shovel of Bethsaida and Synagogue Iconography in Late Antiquity. Pp. 413-59 in Bethsaida: A City by the North

Shore of the Sea of Galilee, vol. 2, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund.

Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press.

Fortner, S.

1995 Hellenistic and Roman Fineware from Bethsaida. Pp. 99-126

in Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea of Galilee, vol.

1, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Kirksville, MO: Thomas

Jefferson University Press.

Grether, G.

1946 Livia and the Roman Imperial Cult. American Journal of

PMology 67:222-52.

NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007) 229

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Hachlili, R.

1988 Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Land of Israel. Leiden:

Brill.

Hendin, D.

2001 Guide to Biblical Coins. 4th ed. Nyack, NY: Amphora.

Jones, A. H. M.

1937 The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces. Oxford: Clarendon.

Kindler, A.

1999 The Coin Finds at the Excavations of Bethsaida. Pp. 250-68

in Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea of Galilee, vol. 2, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Kirksville, MO: Truman

State University Press.

Kuhn, H. W.

1999 An Introduction to the Excavations of Bethsaida (etTell) from

a New Testament Perspective. Pp. 283-94 in Bethsaida: A City

by the North Shore of the Sea of Galilee, vol. 2, ed. R. Arav and

R. A. Freund. Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press.

Kuhn, H. W., and Arav, R.

1991 The Bethsaida Excavations: Historical and Archaeological

Approaches. Pp. 76-106 in The Future of Early Christianity:

Essays in Honor of Helmut Koester, ed. B. A. Pearson.

Minneapolis: Fortress.

McCown, C. C.

1930 The Problem of the Site of Bethsaida. Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 10:32-58.

Meyers, C.

2002 Review of Bethsaida: A City by the North Shore of the Sea

of Galilee, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Review of Biblical

Literature 4: 84-87.

Meshorer, Y.

2001 A Treasury of Jewish Coins from the Persian Period to Bar Kokhba. Jerusalem: Yad ben-Zvi.

Notley, R. S., and Safrai, Z.

2005 Eusebius, Onomasticon: A Triglott Edition with Notes and

Commentary. Leiden: Brill.

Nun, M.

1991 The Sea of Galilee: Water Levels, Past and Present. Ein Gev:

ha-kibuts Ein Gev.

1998 Has Bethsaida Finally Been Found? Jerusalem Perspective 54:12-31.

1999 Ports of Galilee: Modern Drought Reveals Harbors from Jesus' Time. Biblical Archaeology Review 25 (4): 18-31, 64.

Overman, J. A.; Olive, J.; and Nelson, M.

2003 Discovering Herod's Shrine to Augustus: Mystery Temple Found at Omrit. Biblical Archaeology Review 29(2):40-49,

67-68.

Pixner, B.

1985 Searching for the New Testament Site of Bethsaida. Biblical

Archaeobgist 48:207-16.

Rainey, A. F.

1984 A Handbook of Historical Geography. Jerusalem: American

Institute of Holy Land Studies.

Rainey, A. F, and Notley, R. S.

2006 The Sacred Bridge: Cartas Atlas of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Carta.

Robinson, E., and Smith, E.

1867 Biblical Researches in Palestine and the Adjacent Regions, 3 vols., 3d ed. London: Murray.

Rutgers, L. V

1999 Incense Shovels at Sepphoris ? Pp. 17 7-98 in Galilee through the Centuries: Confluence of Cultures, ed. E. M. Meyers. Winona

Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Schumacher, G.

1888 The Jual?n. London: Bentley.

Sch?rer, E.; Vermes, G.; and Millar, F.

1979 The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.-A.D. 135), vol. 2. Edinburgh: Clark.

Shroder, J. F., Jr., and Inbar, M.

1995 Geologic and Geographic Background to the Bethsaida

Excavations. Pp. 65-98 in Bethsaida: A City on the North Shore

of the Sea of Galilee, vol. 1, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund.

Kirksville, MO: Thomas Jefferson University Press.

Shroder, J. F., Jr.; Bishop, M. R; Cornwell, K. J.; and Inbar, M.

1999 Catastrophic, Geomorphic Process and Bethsaida Archaeology, Israel. Pp. 115-73 in Bethsaida: A City on the North Shore of the

Sea of Galilee, vol. 2, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Kirksville,

MO: Truman State University Press.

Smallwood, E. M.

1981 The Jews Under Roman Rule: From Pompey to Diocletian. Leiden:

Brill.

Stepansky, Y.

1991 Kefar Nahum Map, Survey. Excavations and Surveys in Israel

10: 87-90.

Strickert, F. M.

1998 Bethsaida: Home of the Apostles. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical.

1999 The Destruction of Bethsaida: The Evidence of 2 Esdras 1:11.

Pp. 347-72 in Bethsaida: A City on the North Shore of the Sea of

Galilee, vol. 2, ed. R. Arav and R. A. Freund. Kirksville, MO:

Truman State University Press.

2002 Josephus' Reference to Julia, Caesar's Daughter: Jewish

Antiquities 18.27-28. Journal of Jewish Studies 53:27-34

Tcherikover, V

1972 The Cultural Background. Pp. 33-50 in The World History

of the Jewish People. First Series: Ancient Times. Vol. 6, The

Hellenistic Age, ed. A. Schalit. Jerusalem: Massada.

1975 Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews. New York: Atheneum.

Urman, D.

1985 The Golan: A Profile of a Region during the Roman and Byzantine Periods. B.A.R. International Series, 269. Oxford: British

Archaeological Reports.

Urman, D., and Flesher, R V M., eds.

1995 Ancient Synagogues: Historical Analysis and Archaeological

Discovery. Studia Post Biblica 47.2. Leiden: Brill.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

R. Steven Notley is professor of biblical studies at the New York City campus of

Nyack Co?ege. He has co-authored The

Sage from Galilee (Eerdmans, 2007) with the late David Flusser, The Sacred Bridge (Carta, 2006) with Anson F. Rainey and

Eusebius, Onomasticon: A Triglott Edition (Brill, 2005) with Zeev Safrai.

230 NEAR EASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 70:4 (2007)

This content downloaded from 64.72.67.213 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 12:31:12 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions