[ERC] The World of the Skandapurana. Northern India in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries

-

Upload

britishmuseum -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of [ERC] The World of the Skandapurana. Northern India in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries

The World of the Skandapuran.a

Supplement

to

Groningen Oriental Studies

Published under the auspices of the J. Gonda FoundationRoyal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

Editor

H.T. Bakker, Groningen

Editorial Board

P.C. Bisschop • D.D.S. Goodall

H. Isaacson • G.J. Meulenbeld

Advisory Board

R.F. Gombrich, Oxford • J. Heesterman †, Leiden

D. Shulman, Jerusalem • J. Williams, Berkeley

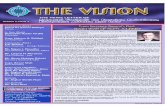

The Skandapuran. a research team on Mount Kalanjara

from left to right: Mudassir Ansari, Elizabeth Cecil, Peter Bisschop, Nina Mirnig,Hans Bakker, Anna Ślączka, Judit Torzsok, Yuko Yokochi, Bijendra Singh

Hans T. Bakker

The World of the Skandapuran. a

Northern India in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries

Leiden | Boston

Typesetting and layout: H.T. Bakker

Research and production of this book have been made possible byfinancial support from:

the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research

the European Research Council

ISBN . . .

...........

Copyright c© 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands

............

Preface

In this book our research on the original Skandapuran. a, pursued over along period of time, comes to a temporary conclusion. And yet, the resultsof our studies cannot be qualified as anything but provisional. Though wehave been working on this Puran. a as a team since the early 1990s, thesheer size of the text has limited the degree to which we are able tocomprehend its full significance. At the moment of writing the adhyayas1 to 69 and 167 have been critically edited and studied in detail, whichis about one third of the text. However, despite this limited progress, ithas become abundantly clear that the Skandapuran. a is a major exampleof Sanskrit literature, an invaluable source for the cultural and religiousworld of early medieval northern India. To explore this world is the aimof this monograph.

The book is divided into two parts.

The first part is a survey of the political landscape, from the fall of theGupta Empire to the chaotic days of Hars.avardhana’s successors. This isa turbulent period in Indian history, seeing the fall of one empire and therise of another in barely more than one century. We have to situate thecomposition of our text in this landscape. It is my sincere conviction thatan appraisal of its religious content cannot be done properly, unless thematrix of the political history of North India in the sixth and seventhcenturies is first carefully worked out.

The present survey is not an economic and social history of early me-dieval India, nor are questions regarding the changing nature and organ-isation of the state addressed. This I have to leave to historians. Thepresent historical survey is informed by the question of how the cultureand religion embedded in the Skandapuran. a could have developed withinthe political ramifications of the investigated period. Due to the scarcityof our historical sources as well as the nature thereof, such historiographynecessarily assumes the form of a description of royal dynasties, their com-ing to power, their wars and decline. I am aware that many Indologistsfind this a rather tedious branch of the discipline. If it does not put themoff altogether, an option could be to pass over Part I and to begin with

vii

viii Preface

Part II, in which, through cross-references, readers are directed towardsthe relevant historical circumstances elaborated in Part I.

In order to lay bare the historical ramifications, my methodologicalstrategy has been to give priority to the Sanskrit sources, which for thegreater part are inscriptions. I have presented these sources by renderingthem into English, while the Sanskrit texts are given in the footnotes,in orthographic spelling and, when needed, in slightly emended form, if Iwas confident of the intended reading. When the significance hinges on aproblematic or dubious reading this has been made explicit. For consultingthe original, diplomatic edition, scholars are referred to the publicationsof the inscriptions in Epigraphia Indica etc.

The preference given to the primary sources has also been motivatedby the state of Indian historiography. I find the extent to which old ideasare being recycled without being checked against the actual sources oftenunacceptable. Instances thereof include, for example, the untenable theorythat the Later Guptas moved to Malwa after their defeat by the Maukharis(discussed in n. 247 on p. 86), and the supposedly epoch-making battlebetween Hars.avardhana of Kanauj and Pulakeśin II of Badami, which isgenerally believed to have been ‘a turning point in the history of India,’discussed on p. 109.

Part II of this study is devoted to the exploration of the Skandapura-n. a’s connection with the major religious movement of its time, PaśupataSaivism, and of historical sites where archaeological remnants still testifyto this connection. Here we had to be pragmatic. It was impossible to visitand explore all the places mentioned in the text for obvious reasons. Weselected six sites or areas which play an important part in the mythologyrelated by our text and which have preserved enough sixth and seventh-century remains to allow an assessment of their links with the Skandapura-n. a. The findings of our fieldwork sometimes reached beyond the world ofthe Puran. a. This, for instance, was the case on Kalinjar Hill (Kalanjara).The impressiveness of the remains there and their relative obscurity haveled me to indulge in them a little more than can strictly be justified bythe Skandapuran. a.

The fieldwork that underlies Part II has partly been a joint undertakingby the team of scholars that has worked with me on the Skandapuran. aover the last five years. A photograph of this team on Mount Kalanjara ispresented in the frontispiece. The sixth site which I have chosen to discussin this book, Kot.ivars.a or Bangarh in West Bengal, I did not visit myself.It was investigated, however, by my friend and teammate Yuko Yokochi(Kyoto), and I am grateful that she has been willing to share her findingsand to write this chapter together with me. Professor Yokochi has also

Preface ix

prepared an edition of the Kot. ıvars.amahatmya in Skandapuran. a 171, andwe present this text in an Appendix to this chapter.

The purpose of the six studies contained in Part II is to give the Puran. aa Sitz im Leben. The Mahatmyas related in the text were not value-free.They served the interests of the Maheśvara or Paśupata communities byproviding them with an authoritative basis for the claims to holiness ofthe sites and institutions in their charge. As such the text supported thesefellow believers in their rivalry with other religious organisations, andthis may have been one of the considerations that inspired some learneddevotees to compose a huge work like the Skandapuran. a. Though thepolitical history in Part I is meant to supply a coherent framework, thesix studies still remain fragmented to some extent. In the present stateof our knowledge this seems unavoidable. However, if the mosaic work ofPart II can evoke a sense of the historical actuality of the world of theSkandapuran. a, my aim has been achieved.

As I have noted above, the present book is very much the product ofcollaborative work.

A team was formed in September 2008, when we were awarded a grantfor the project A Historical Enquiry Concerning the Composition andSpread of the Skandapuran. a by the Netherlands Organisation for Scien-tific Research (NWO) to continue our efforts to disclose the world of theSkandapuran. a. In addition to the old team members, Harunaga Isaac-son (Hamburg), Yuko Yokochi (Kyoto) and Peter Bisschop (Leiden), MsNatasja Bosma and Ms Martine Kropman joined our group and were in-stalled as PhD researchers at the University of Groningen. We regret thatMs Kropman was obliged to resign for reasons of health, but in the yearthat she worked with us she contributed important new ideas, which havebeen incorporated into this book. Ms Kropman was succeeded by Dr NinaMirnig, who as a postdoc researcher explored the history of early Saivismin Nepal and its connection with northern India. In writing this book Ihave greatly benefited from the results of her studies, and from those ob-tained by Ms Natasja Bosma, who investigated forms of early Saivism inDaks.in. a Kosala (Chhattisgarh). Drafts of this study in various stages havebeen discussed during the meetings of the research team, which has beenreinforced by Dr Judit Torzsok (Lille) since 2010. Unforgettable was ourjoint fieldwork trip in January 2012, which has contributed so much tothe present study. I owe a large debt of gratitude to all members of thisresearch group.

In the course of my research within the framework of the Skandapuran. ascheme, I became increasingly aware of the important role of temples andmonastic institutions with their landed estates in the formation of Gupta

x Preface

and post-Gupta culture and society. The Paśupata movement played a keyrole in this development and the Skandapuran. a is just one of its tangibleand remaining results. My thoughts on this subject were brought intofocus by intensive discussions and joint fieldwork with Michael Willis,curator South Asian Collections at the British Museum. Gradually theplan evolved to couch our ideas into a concrete research scheme. The firstoutcome of this joint effort was the project Politics, Ritual and Religion:Cultural Formation in Early Medieval India, which was awarded a grantby the Leverhulme Trust (2011). Our work at this project inspired a morecomprehensive, cooperative ambition, resulting in the research proposalBeyond Boundaries: Religion, Region, Language and the State, which wasawarded a ‘Synergy Grant’ by the European Research Council (2013).

The present book is very much the consequence of the forces com-bined in these three programmes, the ‘Skandapuran. a Project’ (NWO),the ‘Politics, Ritual and Religion Project’ (Leverhulme) and the ‘BeyondBoundaries’ programme (ERC). I am deeply grateful to these three bodiesfor the trust placed in our research and the financial facilities put at ourdisposal, and in particular my thanks are due to my friend and colleagueMichael Willis who took the lead in applying to the latter two of thesethree institutions.

In addition to the people and institutions mentioned above, I havebeen helped at various stages by friends who read parts of this studyand from whose criticism and suggestions I have derived great benefit. Iwould particularly like to mention Alexis Sanderson (Oxford), Arlo Grif-fiths (EFEO), and Phyllis Granoff (Yale). A special word of thanks is dueto Yuko Yokochi, who not only joined me in my research during everystage of this study, contributing to it and providing many of its ideas, butwho also went meticulously through the whole manuscript, keeping mefrom many inaccuracies or worse by her Sanskrit learning.

I am also indebted to Julia Harvey who tirelessly ploughed her waythrough the English, and to Egbert Forsten, my life-long friend and pub-lisher, who continued to give valuable advice on the graphic design of thisbook, even after the Groningen Oriental Studies was taken over by BrillLeiden. I am grateful to my new publisher Brill for continuing this seriesin Egbert’s spirit.

However, the greatest debt of gratitude I owe to my wife Aafke, whoselove has never failed and thanks to whose patient support this work hasseen the light of day. This book is dedicated to her.

Hans Bakker

Table of Contents

Introduction

A tour d’horizon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Preamble . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1The geographical and historical perimeter . . . . . . . . . . 1The cultural framework . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

The Vais.n. ava world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4The sphere of Goddess worship . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5The outside world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7The heterodox religions and the Sam. khya . . . . . . . . . 8The Śaiva world . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

The centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Composition and spread of the Skandapuran.a:A possible scenario . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

I The World of PowerThe Political Landscape

from Skandagupta to Hars.avardhana’s successors

The Twilight of the Gupta Empire . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Hun. a Attacks and Inner Fragmentation . . . . . . . . . . 25Skandagupta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Budhagupta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28Harivarman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29Toraman. a . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30The Aulikara rulers of Daśapura, Mandasor . . . . . . . 32Yaśodharman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Mihirakula . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

xi

xii Contents

The Maukharis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

The Origin of the Maukhari Dynasty . . . . . . . . . . . . 41Harivarman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41The Maukharis of the Gaya Region . . . . . . . . . . . 42

The Maukharis of Kanauj . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47Iśvaravarman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Iśanavarman . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

The Sulikas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53The Andhras . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55The Gaud. as . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

A Period of Stability and Cultural Bloom . . . . . . . . . 62Śarvavarman and Avantivarman . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62The Kaumudımahotsava . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71Viśakhadatta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

A Reshuffle of Power in Madhyadeśa . . . . . . . . . . 77

The Thanesar–Kanauj Axis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77Preamble . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77Sthaneśvara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77Malava . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80The Malava–Gaud. a conspiracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84Hars.avardhana’s consecration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86Śaśanka . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

The Reign of Hars.avardhana (ad 612–647) . . . . . . . 95

A Literary and a Buddhist Record . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95Ban. a’s introduction to the court . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95Hars.a’s campaigns against Gaud. a . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

The Establishment of an Empire . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102The East: Bengal and Orissa . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102The South: Hars.a’s struggle with the Calukyas . . . . . 104A looming threat from the West . . . . . . . . . . . . 113Foreign Affairs: The empire in the international arena . . 119The ‘Arena of Charitable Offerings’ . . . . . . . . . . 123The end of an epoch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128The aftermath: the rise of the Gupta kings of Magadha . 130The Skandapuran. a reaches Nepal . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

Contents xiii

II The World of CultureThe Skandapuran. a

its composition and positionwithin the literary and religious landscape

The Paśupata Movement and the Skandapuran.ad Benares d . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

The Composition and Transmission of the Skandapuran. a . 137The historical time frame . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137Varan. ası . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 138The Paśupata history as told in SPS 167 . . . . . . . . 140The Junvanı Copperplate Inscription of Mahaśivagupta . 143The Lagud. i tradition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145Diversity and coherence of the Paśupata movement . . . 147

The Kapalikas of Magadha . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 151The Mahavrata . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

The Skandapuran.a and Ban.a’s Hars.acaritad The Sarasvatı, Kuruks.etra and Thanesar d . . . . . . . . . 155

Preamble . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155

The Puran. a in Performance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156

Ban. a’s Family Tree and the Foundation of Sthaneśvara . . . 158The myth of Dadhıca . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 158

The Abhis.eka of Skanda and Hars.avardhana . . . . . . . . 161Nılalohita and Kuruks.etra . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165Kuruks.etra . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 169

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172

The Myth of Daks.a’s Sacrificed Hardwar and Rishikesh d . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

Preamble . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173

Bhadreśvara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174The initiation of the gods in the Paśupata vrata . . . . 174Bhadreśvara: the site . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 178Kubjamraka . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181Brahmavarta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183

Kanakhala . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186

xiv Contents

The Seven Brahmins, King Udayana,and Śveta’s Struggle with Deathd Kalanjara Hill d . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189

The Legend of the Seven Brahmins . . . . . . . . . . . . 189Historical evidence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 189Literary evidence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192

The seven deer of Kalanjara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 193Mr.gadhara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194

King Udayana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200The Kalacuris of Ujjain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203Udayana, Vasanta, and the carrier . . . . . . . . . . . 205

The Story of Śveta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209Śveta in the Skandapuran. a . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 210The Kalacuris of Kalanjara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 213The twenty-eight incarnations . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214

The Paśupatas and Śaiva of the Nılakan. t.ha Temple Complex 215

Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 218

The Myth of Tilottama and Man.d.aleśvarad Mun.d. eśvarı Hill d . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221

Man. d. aleśvarasvamin and the Skandapuran. a . . . . . . . . 221The myth of Tilottama . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 221Mun.d. eśvarı Hill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222The inscription of Udayasena, Year 30 . . . . . . . . . 225

The Sites of Mun. d. eśvarı Hill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228The Temple of Man. d. aleśvara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 228Vinıteśvara . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231The Tapovana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234Narayan. adevakula . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 235

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 236

Goddesses from the Eastd Bangarh or Kot.ivars.a d

In cooperation with Yuko Yokochi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 241

Bangarh or Kot.ivars.a: the Material Evidence . . . . . . . . 241The Damodarpur copper-plate inscriptions . . . . . . . 241The Bangarh excavations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

Contents xv

Kot.ivars.a in Sanskrit Literature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251Vais.n. ava sources of the Gupta age . . . . . . . . . . . 251Kot.ivars.a and the Skandapuran. a . . . . . . . . . . . . 252The Matr.tantras or the seven Yamalas . . . . . . . . . 257

Later Skandapuran. a Transmission and the Pala Kingdom . 260

Appendixd The Kot.ıvars.amahatmya of the Skandapuran. a d

Edited by Yuko Yokochi (Kyoto) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

Part I (S recension): KoM(S) 1–23 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 263

Part I (RA recension): KoM(RA) 1–56 . . . . . . . . . . . 265

Part II (S & RA recensions): KoM 24–44 . . . . . . . . . . 268

ReferencesFigures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273

Plates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 273

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 301

Introduction

A tour d’horizon

Preamble

Fifteen years ago, in 1998, when we were working on the Prolegomenaof the first volume of our critical edition of the Skandapuran. a, we wrotethat,

In the present state of our knowledge, with so much of the text notyet critically established and carefully examined, we cannot assign avery precise date to it; we postpone a full discussion of this point toa later occasion. It must suffice to say that we are inclined to situateit between the sixth and eighth century ad. A firm terminus antequem is of course given by the date of the earliest manuscript, viz.ad 810. (SP I, 5)

Now that our edition has covered about one third of the text, the situationhas improved, though still precious little can be said with great confidence.Yet it seemed to us no longer warranted once again to ‘postpone a fulldiscussion.’ The ‘later occasion’ has arrived and the present book is meantto fulfill this long-standing desideratum, for better or for worse. Latergenerations of scholars, we have little doubt, will find much to reject andto improve, but we welcome that as the natural way of making progress inthe domain of historical knowledge. Our present endeavour is meant to bea modest contribution to this continuing process of learning, a true workof the longue duree.

The geographical and historical perimeter

The Skandapuran. a in its first redaction pertains to Northern India of thesixth and seventh centuries.

The geographical heart of this text is located between Kuruks.etra inthe west, Varan. ası in the east, the Vindhya Range in the south and Uttara-khand in the Himalaya in the north.1 This is not to say that its composers

1 Cf. Bisschop’s observation regarding the distribution of places listed in SP 167: ‘A

1

2 Hans Bakker

had no knowledge of the cultural and geographical identity of the Subcon-tinent as a whole. They were very aware that the religious movement,among whose proponents they counted themselves, had its origin in southGujarat (Karohan. a). The legendary history of the Pancartha doctrine aspropounded by Lagud. i, told in adhyaya 167, is there to prove it. Theyalso had enough information about outlying Śaiva or Paśupata centresto mention them and to include their mythology in the text. This is at-tested by the Mahatmyas of Śankukarn. eśvara at the mouth of the RiverIndus,2 Puriścandra in the Western Ghat.s,3 two Gokarn. as, a northern anda southern one,4 Śrıparvata in Andhra Pradesh,5 and Kot.ivars.a in WestBengal.6

What these latter Mahatmyas have in common, with the exception ofthe one of Kot.ıvars.a, is that they hardly, if at all, betray first-hand infor-mation about the topography. This differentiates them from, for instance,the Mahatmyas of Kuruks.etra, Bhadreśvara, or Varan. ası. The importanceof these places is acknowledged and guaranteed by connecting them withŚaiva mythology, but the text does not bear witness to a direct acquain-

few things strike me as significant. First, the absence of any place south of the Dec-can. The north-east is likewise conspicuously absent. The Himalaya, by contrast,takes up a prominent position. Śiva’s longstanding connection with mountains ingeneral, and the Himalaya in particular, is well-known. A similar picture arisesfrom the mythology of Śiva in the entire Skandapuran. a. It is especially the presentGarhwal region down to Kuruks.etra which is richly endowed with sanctuaries: pos-sibly all sanctuaries listed from Mahalaya up to Taks.akeśvara are to be located inthis area. If so, more than half of the mundane sanctuaries mentioned (thirteenout of twenty-four) belong to this area, which indicates its prominent position forearly Śaivism. Ancient Kashmir, on the other hand, is another area conspicuousby its absence’ (Bisschop 2006, 14).

2 SPBh 73.8–106. Granoff 2004, 114f. argues that, ‘a story like the one in SPBh 73represents an effort to remake a holy site, once sacred to Śankukarn. a, into a Śaivasite. [. . . ] The existence of a holy site bearing the name of Śankukarn. a furthersuggests that the Gan. a Śankukarn. a may well have been a figure, like Ghan. t.akarn. aor Naigames.in, to whom an independent cult was dedicated.’ See also below, n. 471on p. 151 and n. 534 on p. 173; Bisschop 2006, 220.

3 SPBh 122.73–88. The place is situated near the Hariścandra hilltop, modern Hariś-candragarh, 80 km north of Pune. Bisschop 2006, 203.

4 The southern one is the well-known Gokarn. a on the west coast south of Goa. Thenorthern one may refer to the Gokarn. eśvara in the Kathmandu Valley. Yokochi2013b (SP III, 105) thinks that the Mahatmya told in SP 60.22–71 may refer tothe northern Gokarn. a, but whether it is to be located in Nepal remains an openquestion.

5 SPBh 70.42–59. This hill is to be identified with Śrıśaila in the Kurnool District ofAndhra Pradesh. See Bakker 1997, 46; SP I, 107; Bisschop 2006, 201. It became amajor centre under the dynasty of the Vis.n. ukun.d. ins (below, p. 3).

6 SPBh 171.78–137. For this Mahatmya see below, p. 263 ff. The place can be iden-tified with Bangarh near the village of Gangarampur in the Dakshin DinajpurDistrict of West Bengal (India). For further discussion see below, p. 252.

Introduction 3

tanceship of the composers with the local situation.Regarding the time-frame, it can be observed that the composers were

very well acquainted with the Mahabharata,7 Harivam. śa,8 and the Pura-n. a,9 from which texts verses, whole passages, or myths are occasionallyborrowed. This makes the beginning of the sixth century a plausible ter-minus post quem.

On the other hand, the Skandapuran. a specifies a holy place in Andhra,Citraratha (SPS 167.92–94), which we know from epigraphical and archae-ological sources pertaining to the fourth and fifth centuries to have been animportant sanctuary of the Śalankayana dynasty, whose kings are said tohave been devotees of Citrarathasvamin.10 The site, identified with Vengı-pura, modern Peddavegi near Ellore, obviously went into a decline whenthe Śalankayanas were being eclipsed by the Vis.n. ukun. d. ins under KingMadhavavarman II in the second half of the fifth century, a dynasty thatdirected its devotion to the Lord of the Śrıparvata.11 The Skandapuran. ais the last text known to us that mentions Citraratha. Though this evi-dence does not contradict our proposed terminus post quem, it may pointnevertheless to a date for our text that cannot be much later than thesixth or seventh century.12

This tallies with the fact that the Skandapuran. a seems to be barelyacquainted with Tantric forms of Saivism. Here we should tread cautiously.In SP I, 4 we observed:

The background of the text must presumably be sought in circlesof lay Śaiva devotees, associated perhaps rather with Paśupatas ofsome kind than with Tantric Śaivas proper. The SP does howevershow awareness of Tantric Śaivism of some sort. See especially the

7 E.g. SPBh 164.1–3 ≈ MBh 9.43.50–52 (Skanda’s abhis.eka). See below, p. 162 andSP I, 25f.

8 E.g. SP 57.39 = HV 19.18 (the story of the seven brahmins; see below, p. 193). Cf.also the Mahatmya of Kot.ıvars.a (p. 252).

9 The reference in SP 1.9 to ‘the Puran. a’ may refer to a text basically consistingof the Puran. apancalaks.an. a (see SP I, 20–22). Our text seems to borrow directlyfrom (an early) version of the Vayupuran. a/Brahman. d. apuran. a in the Nılakan. t.hamyth—SPBh 114 ≈ VaPVenk 1.54 (Bd. P 1.2.25)—and in its concluding descriptionof the Śivapura (SPBh 183.1–40 ≈ VaPVenk 2.39.209–255, Bd. P 3.4.2.211–238). SeeBisschop 2007.

10 E.g. the Plates of Vijayadevavarman in EI IX (1907–08), 58: bhagavato cittaratha-sami-padanujjhatassa bappabhat.t.arakapadabhattassa paramamahessarassa salanka-yanassa assamedhayajino maharajasirıvijayadevavammassa vayan. ena elure mul.u-d. a-pamukho gamo bhan. itavvo | Cf. HCI III, 204–06; Bisschop 2006, 200.

11 E.g. the Ipur Plates (set I) of Madhavavarman, Year 37 (Sankaranarayanan 1977,159): bhagavacchrıparvatasvamipadanudhyatasya vis.n. ukun. d. ınam [. . . ] śrıgovinda-varmanah. putrah. [. . . ] maharajaśrımadhavavarma vijayaskandhavarat [. . . ]. Cf.Sankaranarayanan 1977, 19, 54, 141.

12 See Bisschop 2006, 14, 200.

4 Hans Bakker

intriguing reference to and list of what are called Matr.tantras (SPBh

171.127–131).

This ‘intriguing reference’ is found in the context of the Kot. ıvars.amaha-tmya. Again, Kot.ivars.a seems to be the exception. We will deal with thispassage in greater detail below (p. 257). In the present context it willsuffice to note that this reference appears to be isolated and inconclusive.

Apart from this instance, we have not been able to trace any knowledgeof texts, rituals, or ideas typical of the Mantramarga in the Skandapuran. aas represented in the Nepalese manuscripts. The Mahatmya of Kot.ıvars.a isthe last one presented in the text, contained in adhyaya 171.13 Obviouslythis Mahatmya was included in a phase in which the first redaction of thetext was about to fix the final composition. Here the geographical andreligious scope of the composers reached its maximum span.

The above observations lead us to consider the end of the seventhcentury as a plausible terminus ante quem.

The cultural framework

These two termini serve as points of departure for our reconstruction ofthe cultural framework in which the composition of the Skandapuran. a wasembedded. This is the book’s principal aim.

The Vais.n. ava world

The composers of the Skandapuran. a contributed to the rising tide of earlyŚaiva or Paśupata religion. Whether they were ascetics, acaryas, laymendevotees (laukika), or a mix, they belonged to a milieu of learned Maheśva-ras. As such they were well aware that the Vais.n. avas had been and werestill serious competitors in the pursuit of popular support and patronageof the rich and powerful.

However it seems that Vaisnavism was compromised by having beenthe offical religion of the empire and, since the fall of the Guptas, Vais.n. a-vas were in bad grace. All the rulers and dynasties that play a role in thisbook had turned to Saivism: Maitrakas, Kalacuris, Aulikaras, Maukharis,Hun. as, Vardhanas, Pan.d. uvam. śins, Śaśanka, and the Licchavis. Only the

13 SPBh 171.78–137. After this Mahatmya the text continues, in SPBh 172, with themyth of Indra clipping the wings of the mountains, Prahlada’s fight with Vis.n. u(see Granoff 2004, 128–30), after which he becomes the Sam. khya teacher Panca-śikha (SPBh 172.63; see below, p. 8); in SPBh 173 with a eulogy on the greatnessof brahmins; in SPBh 174–182 with an exposition of Paśupata yoga; and in SPBh

183, the last chapter of the text, with a description of the Śivapura and Vya-sa’s practising of Paśupata yoga, after which he sets out on a tırthayatra (SPBh

183.61–62).

Introduction 5

Later Gupta king Adityasena is a paramabhagavata; his successors, Deva-gupta and Vis.n. ugupta, were again paramamaheśvaras. The preponderanceof Saivism over Vaisnavism owed just as much or more, in my view, topolitical considerations, than to an alleged greater expediency in providingthe religious rituals that were in demand by kings and their ministers.

The intricate relationship between the Vais.n. avas and Śaivas in thisformative stage of ‘the Śaiva Age,’ was the subject of a penetrating analysisby Phyllis Granoff, who observed:

While there is no denying the element of sectarian propaganda in the earlySkandapuran. a stories [. . . ], the combined weight of the evidence from othertexts suggests that sectarian concerns are not the sole factor responsiblefor the form these stories took. [. . . ]

My hypothesis is that [the tradition] remakes itself in conformity withsomething that is happening around it in Vaisnavism. This is the restruc-turing of earlier, in some cases, cosmogonic stories, and the creation of newstories with a single pattern: the appearance of a god in the world of mor-tals and demons in order to destroy evil. It is perhaps not incidental thatone of the earliest such stories in the Śaiva corpus, the story of the defeat ofAndhaka,14 is explicitly linked to the Vais.n. ava corpus in that Andhaka isthe child of the demon Hiran. yaks.a,15 who is defeated by Vis.n. u in the boarincarnation,16 and whose brother Hiran. yakaśipu is defeated by Vis.n. u asthe Man-lion.17 I believe that the stories in the early Skandapuran. a makeclear some of the problems that both the newly emerging Vaisnavism andSaivism, which owed so much to Vais.n. ava mythological models, faced.18

The Vais.n. ava myths accommodated to the Saivism of the Skandapura-n. a occupy a comparatively large proportion of the text.19 This seems tosupport the view that Vaisnavism was a major concern in early medievalSaivism. But the attitude of the composers could not be better illustratedthan by the fact that within the entire Mahatmya of Varan. ası (SP 26–31.14), with all its detailed descriptions of bathing places and sacred spotsin the holy town, not a single Vais.n. ava tırtha is mentioned.

The sphere of Goddess worshipThe text’s attitude is different when it comes to accommodating forms ofgoddess worship to the world of the Skandapuran. a: viz. embracing ratherthan opposing.

14 The Andhaka Cycle (including many subplots) in the Skandapuran. a roughly coversSPBh 73–157. It comes to an end when Devı accepts Andhaka as her son (SPBh

157). See below, p. 69.15 SPBh 73.89–94.16 SPBh 99–108.17 SPBh 71.1–47.18 Granoff 2004, 130, 133f.19 SPBh 70–72, 75–110, 115–122.

6 Hans Bakker

Taking their starting point from Śiva’s spouse, Parvatı, the embodi-ment of the brahminical ideal of womanhood, a chaste and loyal wife, whois an affectionate mother to boot, the composers of our text envisage twomore classes of goddesses which are subsumed under, and at the same timeincluded by Parvatı, ‘Mother of the World.’ In the Vindhyavasinı Cycle,which is the subject of SP III, Parvatı sloughs off her dark skin/side, whichbecomes embodied in the goddess Kauśikı, alias Vindhyavasinı, since sheis located in the Vindhya mountains. She is the personification of theformidable, dark-skinned, virgin warrior and demon-slayer. The figure ofVindhyavasinı contains a type of deity that might have emerged from god-desses worshipped in the Vindhyas. This warrior goddess, again, is con-sidered to be the source of hosts of terrifying goddesses called ‘Mothers,’often with animal or bird’s heads, who represent a plethora of female folkdeities (SP 64.19–29).20 That we are here concerned with local goddessesfollows from SP 68.1–9, in which these goddesses are assigned by Kau-śikı to various actual countries, cities and villages, such as, for instance,Revatı to Gokarn. a, Prabha to Vatsagulma, Laks.mı to Mt Kola, S. as.t.hı toKaśmıra, Bahumam. sa to Kot.ıvars.a, and Citraghan. t.a to Varan. ası.21

Lifting up the tail of Indra’s en-emy (i.e. the buffalo demon),putting her foot on his head withforce, and taking her trident,she pierced his back and quicklyrobbed the demon of his life.22

Skandapuran. a 68.22

Plate 0Mahis. asuramardinı

Nachna, Ramvan Museum

20 See Yokochi (2013b) in SP III, 25–32.21 In SPBh 164.142–178 Kauśikı gives these Mothers (Matr.s) to Skanda on the occa-

sion of his abhis.eka. In this context more than two hundred names of goddessesare mentioned. See Yokochi 2013b (SP III, 135f.).

22 SP 68.22: udgr.hya sa valadhim indraśatroh. kr. tva ca padam. śirasi prasahya | triśu-lam adaya bibheda pr.s. t.he vyayojayac casubhir aśu daityam ‖

Introduction 7

The Skandapuran. a thus represents one of the first Sanskrit texts thatgives prominence to this type of goddess devotion, and in its systematicattempt to accommodate these female deities to the highbrow world ofŚaiva mythology it contributed significantly to the emancipation of folkreligion. This development was well underway in the sixth century. Brah-manical sites of goddess worship as attested by the artistic production oficons, especially of Mahis.asuramardinı, came to the fore in northern Indiaduring Gupta rule, and this process continued to grow in the followingcenturies.

SP 68.22 describes how Kauśikı-Vindhyavasinı slays the buffalo de-mon, and this description agrees exactly with an iconographic type of theMahis.asuramardinı icon that made its appearance by the end of the fifthcentury, a type that Yokochi has classified as ‘Vindhya subtype.’23 An im-age found in Nachna, now in the Ramvan Museum, represents the earliestknown specimen of this type (Plate 0).24 Styllistically it may be dated toaround ad 500. If we follow Yokochi 2013b, and allow about half a century‘for the dissemination of a specific icon, ad 550 would be plausible as asafe upper limit for this description’ in the Skandapuran. a.25

The emancipation of female deities initiated by the Skandapuran. a fi-nally led to a dominance of the Goddess in some forms of Tantric Saivism,in which she was conceived of as a supreme, feminine power, śakti, some-times even transcending Śiva himself. This concept of śakti, however, isstill unknown to the Skandapuran. a,26 though the start of this developmentis maybe visible in the Skandapuran. a’s reference to the Matr.tantras.27

The outside worldThe Skandapuran. a professes to be a staunchly orthodox work, which isshown, inter alia, by the nearly total neglect of anything outside the worldof Brahmanism. It does not seem to know the Hun. as, mentions the coun-tries of the Persians (Paraśıka) and Yavanas only once, viz. as places towhich the goddesses Upaka and Vayası are assigned by Kauśikı,28 and theword mleccha occurs in the text only twice, once when the demons withangry-faces are compared to Mlecchas, at the moment that they struck

23 See Yokochi 1999 and 2004b, 137–152.24 Another, somewhat later, example of the ‘Northern subtype,’ is illustrated in Plate

3 (below, p. 44).25 SP III, 57.26 In the extraordinary hymn to the Goddess in Dan.d. aka metre found in SP 32.113–

117, she is once called ‘power (śakti) of Maheśa.’ This is, as far as we have beenable to check, the only occurrence in the Skandapuran. a in which the Goddess iscalled the Śakti of Śiva.

27 Above, p. 4 and below, p. 257.28 SP 68.4: vatsagulme prabham. devım. laks.mım. kolagirav api | upakam. paraśıkes.u

vayasım. yavanes.u ca ‖ 4 ‖

8 Hans Bakker

down with their axes, lances, swords and hatchets the elder brother ofSkanda (i.e. Vinayaka),29 and a second time, when it mentions a rebirth,after a stay in hell, among the Mlecchas where one lives like an immortal,a rebirth that is the result of a donation of food in a preceding life, evenif that food was impure and not consecrated.30

The heterodox religions and the Sam. khya

The heterodox religions meet with similar neglect. Only once, apparently,when the text sums up the people who will go to the Mahapadma Hell,does it refer to heretic mendicants, with whom probably the Buddhists aremeant, Nirgranthas and Ajıvakas and the brahmins who support them.31

In a similar context, the followers of the false doctrine of Kapila, i.e. theSam. khyas, are condemned, but here the situation is more complex.32

Although Paśupata Saivism considers the Sam. khya philosophy as suchinferior, it does not usually condemn it since its doctrine is acknowledgedas the basis of its own system. This is explicitly the case in the Skanda-puran. a chapters that deal with the Paśupata yoga (SPBh 174–181). More-over, SPBh 172.59–66 tells us that the Daitya Prahlada turns to Asuri,the pupil of Kapila, and becomes the Sam. khya acarya Pancaśikha, who,thanks to the Sam. khyasiddhanta, transcends the threefold suffering andreaches brahman.33 The declaration of the Sam. khya as a false doctrine

29 SPBh 136.19: jambhe ’vasanne ’ribale prasanne, s.ad. danavah. s.an. mukhapurvajam.tam | kut.haraśulasiparaśvadhais tu, mleccha yatha kruddhamukhas tataks.uh. ‖

30 SPBh 111.16cd–19cd:avadhutam avajnatam asatkr. tam athapi ca |annam. pradadyad yo devyo yadr.śam. tadr.śam. śubhah. |tasyapi narake ghore yatyamanasya raks.asaih. ‖upatis. t.heta bahudha tr.ptir yenasya jayate |yadi manus.yam ayati kadacit sa narah. punah. |mlecches.u bhogı bhavati ramate ca yathamarah. |annam evam. * viśis. t.am. hi tasmad na paramam. bhuvi ‖

* Bhat.t.araı’s edition reads annemevam. .31 SP 45.11: dus.t.aśravan. anirgranthas tathaivajıvakaś ca ye | bhaktas tebhyo dvijo yaś

ca narakam. samprapadyate ‖32 SP 48.10: śastran. i harate yaś ca goghno yaś ca narah. smr.tah. | kapilaś ca vr. thadr.s. t.ir

vedadharmarthadus.akah. | nastikaś ca duratmana ity ete tam. prayanti vai ‖33 SPBh 172.59–62:

param. tattvam athanves.t.um. gun. atıtam ajam. śivam |saks. ad bhagavatah. śis.yam. kapilasyasurim. munim ‖ 59 ‖śis.yatvenopasam. gamya moks.avidyam avaptavan |prakr. tınam. param. tattvam. vikaran. am. param. tatha ‖ 60 ‖ks.etrajnam. purus.am. jnatva bhoktaram. bhoktr.varjitam |moks.avidyapararthajnah. sam. khyasiddhantaparagah. ‖ 61 ‖siddhah. pancaśikho namna so ’bhavad munisattama |sa yogam. paramam. labdhva sam. khyacaryo mahamunih. |duh. khatrayavinirmuktah. praptavan padam avyayam ‖ 62 ‖

Introduction 9

seems, therefore, to be out of place, and may be seen as an indicationthat the chapters on the thirteen hells (SP 37–51) have a non-Paśupatabackground.34

The Śaiva worldFascination with hell was to become a regular feature of texts belong-ing to the Śaiva Siddhanta corpus, in which the concept of 32 basic hellsprevails.35 The Skandapuran. a’s representation is closer to the hell descrip-tions that are found in the Śivadharma corpus, a collection of texts thatwas intended for the Maheśvaras at large, and of which the nucleus isgenerally conceived of as predating the Śaiva Siddhanta.36

In addition to the number of hells, viz. thirteen, the hell conception ofthe Skandapuran. a distinguishes itself from all similar descriptions in oneother important aspect. This is the concept of ‘elevations’ (ucchraya). Thisconcept, explained in SP 37.9, is not known from Śaiva literature otherthan the Skandapuran. a, but it is strikingly similar to that of the utsada

Cf. Sam. khyakarika 70: etat pavitram agryam. munir [i.e. Kapila] asuraye ’nukampa-ya pradadau | asurir api pancaśikhaya tena ca bahudha kr. tam. tantram ‖ 70 ‖Larson 1987, 107f. formulates a scholarly consensus to the effect that ‘by the sixth-century of the Common Era (the approximate date of the Chinese translation) andthereafter, the writers of Sam. khya texts (a) identified Kapila as the founder of thesystem, (b) recognized Asuri as someone who inherited the teaching, (c) consideredPancaśikha as someone who further formulated the system (tantra) and widelydisseminated it, and (d) described Iśvarakr.s.n. a as someone who summarized andsimplified the old system after an interval of some centuries (Paramartha’s Chinesetranslation) or more (Yuktidıpika).’

34 See the Introduction to SP II B, pp. 9–10.35 Sanderson 2003–04, 422; Goodall 2004, 282f. n. 490.36 Sanderson forthcoming, 8f: ‘The Śivadharma and the Śivadharmottara were pro-

duced when initiatory Śaivism was restricted to ascetics or at least in the context ofthat form of Śaivism. That the Śivadharmottara was written in the context of theearlier ascetic Śaivism is evident from its instruction (2.147–50) that there shouldbe a shrine next to a monastery’s hall for public instruction in which one shouldinstall an image of Śiva as Lakulıśa. [. . . ] But later texts of this corpus, such asthe Śivadharmasam. graha and the Vr.s.asarasam. graha, show awareness of the laterform of the religion, in which Śaivism had diversified through its expansion amonghouseholders. Thus the Śivadharmasam. graha shows evidence of dependence onthe Niśvasamukha and the Niśvasaguhya.’ The latter two texts, belonging to thecorpus of the Niśvasatattvasam. hita, are generally seen as early representatives ofthe Mantramarga, initiating a development that would lead to the mature ŚaivaSiddhanta. Sanderson 2013, 234f., following Goodall and Isaacson (2007, 6), datesthis corpus very early indeed, assigning a date of c. 450–550 to the Niśvasamula,the oldest text in the corpus. Since this dating is mainly based on palaeography,and developments therein are difficult to pin-point within an interval of a hundredyears (cf. Sanderson 2013, 221: ‘notoriously unreliable’), we have serious doubtsabout this early date and find it more likely that the corpus began to evolve onecentury later, that is more or less simultaneously with the Skandapuran. a (cf. below,n. 469 on p. 150).

10 Hans Bakker

(Pali: ussada) found in (later) Buddhist literature on hells. It signifies asort of supplementary hell belonging to a major hell (mahanaraka), inwhich the sinner finds some temporary relief.37 Within the Śaiva contextit makes an archaic impression, which, on the one hand, may point toa certain indirect Buddhist influence,38 and, on the other, may be anindication that the description of the thirteen hells in the Skandapuran. ais earlier than related descriptions in the Śivadharma corpus.

Research on this corpus is still in its infancy. Although, admittedly, theŚivadharma seems to have originated in an environment that may havebeen close to the milieu that produced the Skandapuran. a and would merita thorough investigation, we have to limit ourselves in the present contextto a brief mention of one more issue, viz. the arrangement of forty Śaivaholy places into five sets of eight ayatanas, the Pancas.t.aka. This idea hasbeen dealt with by Sanderson, Goodall and Bisschop. Sanderson believesthat this classification ‘was already current when the first scriptures ofthe Mantramarga came into existence, which is not likely to be later thanthe sixth century,’ and Goodall observed that these five sets of eight form‘an earlier, not exclusively Tantric structure.’39 As pointed out by Bis-schop, it ‘is especially significant that the Śivadharma corpus also liststhese five ogdoads (as.t.akas) and mentions no other,’ as is common inlater Śaiva scriptures. He further observed that the Skandapuran. a doesnot yet seem to know this classification of forty places, but that ‘aboutthirty of them are mentioned in the ayatana list of the Skandapuran. a.’40

Like its description of the thirteen hells, the list of ayatanas in SPS 167thus suggests that our text is either more conservative, which would agreewith the Puranic genre, or is slightly earlier than the Śivadharma corpus.In both cases a sixth century date would match the evidence.

The centreA central aim of the Skandapuran. a was to sanctify the landscape of North-ern India. Many of the myths, regardless of over how many chapters theyextend, are geared towards a final section, in which what has been told isrelated to a specific locality. The Andhaka myth cycle appears to be anexception to this rule. Nevertheless, with some exaggeration, it could bemaintained that the Puran. a is to a large extent a sequence of Mahatmyas,whose purpose is to legitimize and lend authority to local communities ofthe Śaiva movement in the sixth and seventh centuries, thus supporting

37 SP 37.9. For the Buddhist utsada see Edgerton’s BHSD s.v.; Kirfel 1967, 201f.;Van Put 2007, 205ff.

38 See the Introduction to SP II B, p. 9.39 Sanderson 2003–04, 405f.; Goodall 2004, 315.40 Bisschop 2006, 27. For a thorough investigation of the Pancas.t.aka in the Śaiva

scriptures see Bisschop 2006, 27–34.

Introduction 11

them in their rivalry with other religious groups. It does so by declaringthe transcendent quality of a particular site, of which the intrinsically di-vine and soteriological value is imparted by representing it as the scene ofprimordial events.

Having stated this much, the reader may ask, why Skandapuran. a, whynot just a Maheśvara or Mahadeva Puran. a? The answer is not easily given.Actually, Skanda does not play a major role in this Puran. a, nor is heconceived of as an object of a special cult besides as a son of Śiva.41 Hisbirth and deeds are only reached at the very end of the text, contained inchapters SPBh 163–65, and 171.42 Apart from occasional references to hisassociation with the Matr.s, Skanda in this Puran. a is first and foremost aSenapati, the god of war. As such he outclasses Indra, who is cut down tosize in SPBh 171.1–77.

The Skandapuran. a may thus be seen as articulating a change of per-spective in a time that was riven by war. It mirrors these conflicts in themany chapters in which it describes in detail the recurrent battles be-tween Devas and Asuras. In addition to the significant role given in themto the warrior goddess Kauśikı Vindhyavasinı (SP 61–66), who as suchmakes her first appearance in the Sanskrit literature, it is the young armygeneral Skanda, Śiva’s son, rather than the old king of the gods, Indra,who should be held in high regard. Or in the blustery words of Skandahimself: ‘Brahma and the rest, Siddhas, and those who know the Vedas,they know who I am; it is immaterial whether you know (who I am, ornot), and for what reasons should I pay my respects to you, O Śakra, youwhose kingship is obtained by tapas and who will soon go down?’43

The centre in which and from which the world is viewed in this way isVaran. ası. The Mahatmya of this holy town is by far the longest and mostdetailed in the Puran. a. Varan. ası is the town where Śiva created by hismind his own divine palace (vimana) of matchless beauty, as well as apleasure grove, more beautiful than any other divine garden (SP 26.64–

41 Yokochi SP III, 24f. n. 45: ‘For a historical study of various characteristics of Ska-nda, see Mann 2001, 2007 and 2012. There are, however, significant differences.According to Mann [2012], the rise of Skanda in mainstream Hinduism as the godof war and Śiva’s son caused the decline of Skanda’s cult. In the case of Vindhya-vasinı, on the other hand, her evolution into the Warrior Goddess was the keyfactor in her establishment in mainstream Hinduism. The decline of Skanda’s cultin this respect may have been caused by the rise of the Warrior Goddess, by whomSkanda was replaced in the function of war god.’

42 The narrative structure required that the birth of Skanda is anticipated in SPBh

72. For a summary of these chapters see Mann 2012, 187–95.43 SPBh 171.7cd–8cd: brahmadya mam. vijananti siddha vedavidaś ca ye | tapasa la-

bdharajyena na cirad astam es.yata | kim. tvaya janata śakra karyam. kim. pujitenava ‖ 8 ‖

12 Hans Bakker

67). In the words of the myth-maker:

This Avimuktaks.etra is holier than other holy places where Devaresides, such as Mahalaya, Kedara, and Madhyama; this is becausethere one only attains gan. a-hood, whereas here one attains finalrelease, which is superior to the state of being a Gan. apati. Eversince the worlds were created, Deva has not left (mukta) it, hence itsname ‘Avimukta.’ When one sees the Avimukteśvara linga, one willbe freed at once from all the fetters of bound souls (paśupaśa).44

The history of Varan. ası has been investigated in the Introduction to Vol-ume II A of our edition of the Skandapuran. a. There it was tentatively con-cluded, after collating all available evidence, that the composition of theMahatmya took place in ‘the 6th or, maybe, first half of the 7th century,’and that the first redaction of the text as a whole was finished ‘under therule of either the Maukharis or Hars.avardhana of Kanauj.’45 This conclu-sion has been roughly confirmed in the following years of research, whichhave resulted in the present study, although at this stage, more than inthe past, we take into consideration that the process of composition andredaction of the text may have extended over a considerable period—theduration of a man’s working life, say about thirty to fifty years.

This is how far historical research can bring us to date. As remarkedabove, precious little can be said with great confidence. The hypothesisadvanced in this book is merely an informed guess. It leaves various sce-narios open. However, in order to satisfy our desire for a palpable resultand a real picture, I have worked out one scenario in more detail andcouched it in an apodictic style. I hope that the reader can appreciate itfor what it is and will not lose sight of its highly speculative nature.

Composition and spread of the Skandapuran.a:A possible scenario

When Avantivarman ascended the Maukhari throne in Kanyakubja in thelast quarter of the sixth century, it may have appeared as if the old daysof stability and prosperity had returned to Madhyadeśa. Thanks to theincessant war efforts of his grandfather, Iśanavarman, the cruel intruderscalled Hun. as had been driven back to the foothills of the western Hima-layas after a long and devastating period of war. A close friendship haddeveloped between the rulers in Kanyakubja and Sthaneśvara, where the

44 Synoptic paraphrase of SP 29.53–57 (SP II A, 129f., 214).45 SP II A, 52.

Introduction 13

dynasty of the Vardhanas guarded the western part of the kingdom. Theeastern enemies, the Gaud. as and their allies the Guptas, had been forcedto take refuge at the borders of the ocean, where they were being kept incheck by Kanyakubja’s powerful southern allies in Daks.in. a Kosala, whotraced their respectable pedigree straight back to Pan.d.u and his mightyson Arjuna.

The ancient land of the Buddha and the cradle of empire was firmly un-der control. Avantivarman proudly bore the title ‘sovereign of Magadha.’ ABuddhist settlement there was developing into a place of learning of highinternational repute. The university of Nalanda attracted students andscholars from all over India and abroad, and the Maukhari king, thoughnot a Buddhist, prided himself on being its chancellor.

The monarch watched over the Bull of the Dharma, which was shep-herded by his countrymen. The Bull, shown on the royal seal, had inrecent years become a forceful emblem, a symbol appropriated by anotherreligion, one to which the Maukharis had confessed ever since they hadthrown off the yoke of the Imperial Guptas with their state deity Vis.n. u.46

Worship of Śiva had opened up new avenues for the imagination and en-shrined royal authority in burgeoning forms of early Tantric Hinduism.

Though familiar with all sorts of asceticism, Northern India in thesixth century saw a new type of strange sadhus travelling around, whosmeared themselves with ashes and imitated the god of their devotion,Śiva Paśupati. A lineage of gurus pertaining to this movement had settledin Kanyakubja, an establishment founded in the capital by a saint fromKuruks.etra, the ancient battlefield, now firmly under the control of thefriendly Vardhanas or Pus.yabhutis, who themselves had become staunchfollowers of this type of religion. Avantivarman, too, was well disposedtowards them and invited some of them to his court.

The Paśupatas, as these Śiva worshippers were called, made good useof the patronage that fell to their lot. They set up religious centres (stha-na), temples (ayatana) and monasteries (mat.ha) in the country’s mosthallowed places, such as the Kapalasthana in Kuruks.etra, Bhadreśvaranear Gangadvara, the great Deva temple, ayatana, in Prayaga, and thesiddhasthana, ‘home of the saints,’ called Madhyameśvara, circa one kilo-meter north of the renowned cremation grounds of Avimukta or Varan. ası.

A network of itinerant sadhus connected these centres, which becamewell integrated with the local religious infrastructure and developed into

46 Cf. Dundas 2006, 390: ‘It might well be argued that a standard feature of consol-idation of imperial state formations of any variety at any place and time is thefostering of quasi-imperial religions whose totalizing claims and concomitant sym-bolic discourse connected to kingly authority reciprocally bolster the ideology ofsecular power with its ambitions of control and expansion.’

14 Hans Bakker

junctions within a fabric of yogins and religious teachers. The Paśupa-tas had had a good look at their Buddhist counterparts and had copiedtheir formula for success, namely a standing organisation of professionalreligious specialists—yogins, ascetics, and acaryas—supported by a fol-lowing of ordinary devotees, the Maheśvara community at large, to whosespiritual needs it catered.47 One of the peculiar facilities offered to thecommunity of laukikas, by at least some of these Paśupata ascetics, wasto extend services in and around the cremation grounds. Living in thecremation ground was a highly acclaimed strategy within Paśupata as-ceticism. Mahakala in Ujjain, Avimukteśvara in Benares, Paśupatinathain Nepal, to mention just the best known, were run by Paśupatas andbecame key to their success.

Avantivarman, therefore, acted in tune with the spirit of his time whenhe supported the movement. Earlier his uncle Suryavarman had spentlarge sums on the rebuilding of a dilapidated temple of the ‘Foe of Andha-ka,’ whose images were beginning to appear around this time. The princehad hired a poet to sing the praises of the god as well as of himself,chiselled into stone, for everyone to read:

May that figure of Andhaka’s Foe, on whose body snakes glimmer,offer you a stable abode—a figure who wears a lion skin that isslightly crimsoned by the light of the jewel in the hood of the serpent[that is his sacred thread], and who reddens the white line of skullsthat is the chaplet by the radiance from his third eye, and who bearson his crest the slender, darkness dispelling digit of the moon.

He (the prince) had youth that was beautiful like the waxing moonand dear to all the world; he was at peace and his mind was devotedto reflection on the branches of learning; he had mastered fully (all)the arts; it was as if Laks.mı (fortune), Kırti (fame) and Sarasvatı(learning), among others, vied with one another for his patronage:in the world, women in love experience the feeling (of love) all themore, if their lover is beloved.48

Poets were held in high esteem and Avantivarman invited them to hiscourt. Imagine the glamorous world in which plays like the Mudraraks.asawere staged, attended by the playwright Viśakhadatta in person, or theKaumudımahotsava, to mention another play, in which the entrance ofthe ruler himself is announced:

A son of the House of Magadha has arrived, thronged by hundredsof eminent ministers, like the moon enhanced by an aureole of stars,

47 Cf. Brancaccio 2011, 154f.48 For the Sanskrit text of these two verses see n. 202 on p. 70 and n. 203 on p. 71.

Introduction 15

that prince, who is a feast for the eyes of his delighted subjects.49

This is the world in which Sanskrit flourished, the world in which the kaviBhatsu, Ban. a’s respected teacher, was honoured by crowned heads. Thiscourt was sustained by the inhabitants of Kanyakubja who, in the words ofthe famous Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, were ‘honest and sincere, noble andgracious in appearance, clothed in ornamented and bright-shining fabrics,’inhabitants who ‘applied themselves much to learning, and in their travelswere very much given to discussion on religious subjects, whereas the fameof their pure language was far spread.’50 To this court the leading figuresof the community of Maheśvaras were also welcomed. Sanskrit was theirlanguage and in Sanskrit they composed their learned treatises and wittymythology.

For learned treatises and religious expositions the educated classes ofnorthern India looked to Varan. ası. This trading town on the River Gangeshad emerged under the Guptas in the preceding century as a centre of tra-ditional Hindu learning. The arrival of the Paśupata movement added toits reputation for holiness, whereas the collective Sanskrit learning of thetown added to the literary achievements of the Maheśvaras.

The composition of the two classic Sanskrit epics was closed by thefourth century. Some of the new religious ideas concerning the god Śivahad still made it into the latest layers of the Mahabharata. After theRamayan. a had been completed, mythology related to the tutelary deityof the Gupta Empire, Vis.n. u, and his popular manifestation of Kr.s.n. a inparticular, had found expression in an Appendix to the great epic, theHarivam. śa, as well as in a new type of Sanskrit text styled ‘Ancient Lore,’i.e. Puran. a.

The Puran. a as a literary genre in its first stages of development dealtwith the creation of the universe, the origin of the world and its royal dy-nasties. However, as for instance the Vis.n. upuran. a had shown, the genrealso lent itself perfectly to the circulation of popular, religious and mytho-logical material. After the civilized world had recovered from a period ofdevastating wars and invasions, and now that Vis.n. u had ceded his placeof prominence to Śiva, the sixth century embraced a new form of devo-tion. The time had come to collect the mythology of the Great God. Inthe words of the Skandapuran. a: ‘having heard the story of Bharata aswell as the Ancient Lore, we wish to hear about the birth of Śiva’s son,Karttikeya.’51

49 For the Sanskrit text of this verse see n. 210 on p. 72.50 Si-yu-ki I, 206f.51 See below, p. 124.

16 Hans Bakker

A senior brahmin member of the Maheśvara community in Varan. ası,well-versed in Sanskrit literature, an expert on the epic tradition, initiatedin the Paśupata sacred texts, in short, a brahmin with great prestigeamong his fellow believers, charismatic and dynamic, that man, let us callhim the Suta, took the initiative to fulfill this wish and to compose aPuran. a text that would do justice to the rich mythology of Śiva and hisfamily, that would be accessible to the whole community, and, last but notleast, that would validate local claims of the sanctity of holy places andreligious establishments by telling their Mahatmyas. In order to possessthis authority, the text should be in the anonymous, pseudohistoric style ofthe Puran. a, reportedly spoken by a sage of yore with intimate knowledgeof the Great God’s own thoughts and deeds.

It happened in the days of Avantivarman’s reign that a group of kin-dred spirits and literary talents convened in an institution of the commu-nity in Benares. They discussed the plan and pledged their commitment.The Suta, the editor-in-chief, began his composition in Śloka verses, whilean inventory was being agreed on of the myths, stories, topics and placesthat had to be treated in the course of the work, a narrative that wasdesigned to lead to the birth, consecration and heroic deeds of Karttike-ya, but should not reach that point before an extensive cycle of Andhakamyths had been told first—Andhaka who, like the Mleccha foes of theMaukharis, could not be defeated until after an endless series of battles.52

The materials were arranged in a preliminary order in versified form.This inventory or blueprint, Anukraman. ika as it was called, has survivedand come down to us in the second adhyaya of the Skandapuran. a. Theeditor-in-chief was assisted by some editors who were assigned specific por-tions of the composition. The Paśupata network was called in to assembleinformation about places sacred to the Maheśvara community. Sometimesthis resulted in new collaborators entering the group, bringing in localknowledge couched in Mahatmya-style texts, sometimes the editor him-self used the information to compose the story. Rarely were ready-madetexts taken from existing literature. The Suta guaranteed the unity ofliterary style and the quality of the Sanskrit, but this could not preventminor differences remaining. He also took great care that the arrangementof stories, the complex narrative structure of the text, remained consis-tent and logical. However, soon it appeared that the original blueprintcould not be implemented except in broad outline; the myths and storiescomposed had too powerful a dynamic of their own to link up with eachother perfectly. Here the genius of the Suta was most needed and he did

52 SPBh 130–56. Andhaka becomes Śiva’s devotee—his gan. a and adopted son, a myththat was probably narrated for the first time in our text.

Introduction 17

a brilliant job.53

The Paśupata network was strongest along the east-west axis, Vara-n. ası–Kanyakubja–Kuruks.etra. It had been decided to begin in the west,since it was one of the underlying aims of the work to cover, or rather torecover the entire landscape of northern India, transforming it into sacredspace, a landscape on which the deeds of the Great God and his entouragehad bestowed holiness at the beginning of time. The work was well underway—the myths relating to Kuruks.etra and the Sarasvatı, Sthaneśvara,Bhadreśvara and Kanakhala, and Varan. ası itself had been composed, andthe Vindhyavasinı Cycle was drafted—when political reality threatened todisrupt the literary activity. A joint attack from the east and the south-west brought to an end the rule of the Maukharis, just when Grahavarmanhad succeeded his father Avantivarman, while that of its allies in Thane-sar was shaking on its foundations. For a while Benares came under thecontrol of the easterners, the Gaud. as.

A young prince, a kumara from Sthaneśvara, installed as chief of the armyon the banks of the Sarasvatı, as it were the embodiment of Skanda himself,came to the rescue of the kingdom of Kanyakubja. In a war that lastedseveral years, Hars.avardhana succeeded in pushing the Gaud. as under theirking ‘Moon,’ Śaśanka, back across the rivers Son. a and Gan.d. akı.

In about ad 606, the political situation had stabilized enough toorganize a magnificent royal coronation ceremony. Hars.avardhana wasenthroned in Kanyakubja. It would take Hars.a six more years, however,to consolidate his sovereignty over the combined hereditary lands of theVardhanas and Maukharis, including Magadha, and before finally, toparaphrase the closing metaphor of Hars.a’s Deeds sung by the greatestwriter of the time, Ban. a—after a day of bloody contest, at the fall ofnight, while the sinking sun crimsoned the sky and waters of the ocean,the Fame of his House, the Glory of his Rule, and the Force of his Destinyunited to hand over to him a pale-looking Moon.54

Varan. ası was back in the kingdom of Kanyakubja, but the new politicalsituation had an effect on the perspective and scope of the composition inprogress.

To begin with, the historical consecration of a young prince (kumara)on the banks of the Sarasvatı to lead an army against the Gaud. a king‘Moon’ (śaśanka), reflected the mythology of Skanda, the main subject ofthe Puran. a—Skanda, the god of war, who, after his consecration as sena-

53 An illustration of this intricate process is the inclusion of the legend of the sevenbrahmins into the Vindhyavasinı Cycle, for which see Yokochi’s Introduction SPIII, 15–22.

54 For the Sanskrit text see below, n. 270 on p. 93.

18 Hans Bakker

pati on the banks of the same river, led the Devas against the Asuras inorder to destroy the demon king ‘Star’ (taraka).55 The composers decidedto bring their work to the attention of King Hars.avardhana, solicitinghis blessing. After all, Hars.a himself confessed to be a paramamaheśvara,and his court offered a venue to the most promising literary men of thecountry, among whom was the king himself.

Secondly, the king’s military successes against Gaud. a called atten-tion to the east, bringing a Śaiva settlement in western Gaud. a within thepurview of the composers. The Suta, or his successor, made the decisionto conlude the sanctification of the sacred landscape of northern India inKot.ivars.a, an important commercial and religious centre in the provinceof Pun.d. ra, which was situated 80 km north-east of the army camp of KingHars.a on the Lower Ganges, the camp where the king would eventuallymeet the Chinese pilgrim. The concluding chapters of the Puran. a werereserved for philosophy and an exposition of Paśupata yoga, which, alongwith devotion and pilgrimage, would bring the Maheśvara, yogin and lay-man alike, to paradise, the City of Śiva at the top of the universe (SPBh

183), while the accomplished yogin may unite with Śiva (SPBh 182).

The day arrived when the composition of the Puran. a was concluded andthe text could be copied into a carefully prepared book, a pustaka, thatcould be offered to the Great God and donated to the king and the com-munity of the Maheśvaras. As usual when a work of such magnitude wascompleted, a solemn occasion had to be found when parts of the work couldbe recited and the book could be consecrated and ritually entrusted to atemple. Such an occasion was King Hars.a’s ‘arena of charitable offerings,’a spectacular event that was staged every five years at the confluence ofthe Ganga and Yamuna. The great ayatana or temple of Deva there wouldbe an excellent repository.

The permission was obtained. In the middle of Hars.a’s reign, when hewas at the pinnacle of power, a great assembly of feudatories, Śraman. as,and Brahmins, convened in Kanyakubja around the beginning of the NewYear, in preparation of the quinquennial event. The procession to Prayagaand the festivities there were part of the Festival of Spring in the month ofCaitra. The king rode on his magnificent elephant Darpaśata towards Pra-yaga, scattering pearls and other riches, while dressed as Indra. His mobilecourt offered splendid opportunities for staging theatrical productions,first and foremost, of course, those of his own. The Sutradhara in theRatnavalı and Priyadarśika introduces Hars.a’s plays:

Today, on the occasion of the Spring Festival, I have been respect-fully called by the assembly of kings, which has convened from all

55 SPBh 163–65. Below, p. 161f.

Introduction 19

quarters of the world, and which is subservient to the lotus-feetof King Śrı-Hars.adeva. I have been addressed as follows: ‘We haveheard by hearsay that a play entitled Ratnavalı, which is embellishedby an unprecedented arrangement of the material, was composed byour lord Śrı-Hars.a, but we have not yet seen it performed.’56

The play turned out to be a great success, and would stand the test oftime. But Hars.avardhana was too great a king to hear only his own voice.A date for the first recitation of the Skandapuran. a was agreed on. TheSuta and his team were offered their platform. In order to sustain theillusion of its being a work from time immemorial, an essential featureof the genre of Ancient Lore, a professional reader, a pustakavacaka, wasasked to recite it. The first presentation of the work went ahead before anaudience including the king, courtiers, sadhus, monks, literati of all sorts,pandits and a selection of educated Maheśvaras. It was a great tamaśa,going by the consolidated words of the Suta and his fellow kavi, Ban. a:

The sages, assembling in Prayaga to bathe in the confluence of the Gangaand Yamuna on the day of full moon, see the Singer of Ancient Lore comingtowards them to pay his respects.

Dressed in white silk made in Pun.d. ra, his forehead marked by a tilaka con-sisting of lines of orpiment on a white clay coating, his topknot ornamentedby a small bunch of flowers, his lips reddened by betel, and his eyes beau-tified by lines of collyrium, he takes his seat and begins his performance.

He pauses for a moment before he places, on a desk made of reed stalksthat is put in front of him, a pustaka, which, although its wrapping hasbeen removed by that time, is still wrapped, as it were, in the halo of hisnails, which shine softly like the fibres of a lotus.

They ask him about the birth of Karttikeya, a story that equals the Maha-bharata and surpasses the Puran. a, both of which he had recited in theNaimis.a forest on the occasion of a brahmasattra.

Then, while he assigns two places behind him to two flautists, Madhukara,‘the bee,’ and Paravata, ‘the turtle-dove,’ his close associates, he turns overthe frontispiece, takes a small bundle of folios, and announces the story ofthe birth of Skanda, of his friendliness towards brahmins, his glory and hisheroism, greater than that of the gods.

By his chanting he enchants the hearts of his audience with sweet intona-tions, evoking as it were, the tinkling of the anklets of Sarasvatı, as shepresents herself in his mouth, while it seems as if, by the sparkling of histeeth, he whitewashes the ink-stained syllables and worships the book withshowers of white flowers.57

56 For the Sanskrit text see below, n. 393 on p. 126.57 This is a coalescence of two passages, SP 1.4–13 and HC 3 p. 137f. For the separate

texts see p. 124 and p. 156.

20 Hans Bakker

The performance received favourable reactions. After having done theirritual duties, attended the great potlatch ceremony at the confluence, andpaid obeisance to the Great God in his temple and the king in his court,the Suta and his entourage returned to Varan. ası. More copies of the bookwere produced. Small emendations were made and the first transcriber’sfaults slipped in. The different versions of the text were born.

The subsequent transmission and distribution of the Puran. a over var-ious centres of the Maheśvaras added more flaws. The copying took placein focal points of Sanskrit learning, to the west and the east of Varan. ası.In Magadha, some Paśupata acaryas were not entirely satisfied with thetext. They missed in particular an account of the Lakulıśa tradition intheir own country, and, in general, they felt that the holy places in theeast and in the north, in Magadha, Orissa and Nepal, had not been donejustice. They decided to amend this shortcoming by inserting an addi-tional list of tırthas in an adhyaya that appeared to be the right place forit.58

While these processes were underway, the political situation in Indiachanged dramatically. What a few years earlier had still seemed far awayor downright impossible, happened. Hars.a’s empire collapsed. Chaosprevailed all over northern India, whereas the north-east was confrontedby a military invasion from Nepal and Tibet.

Magadha was the first country in which order was restored under theauthority of the dynasty of the Later Guptas. The daughter of Adityaguptamarried the Maukhari prince Bhogavarman, a wise move, contributingsignificantly to political stability. And while the kingdoms of Kanyakubja,Pun.d. ra and Kamarupa were still in disarray, the Gupta House of Maga-dha consolidated its power further by re-establishing good relations withits northern neighbour, the Licchavi kingdom of Nepal. A daughter bornof the marriage with the Maukhari prince, Vatsadevı, was married off tothe Licchavi king Śivadeva.

During the last two decades of the seventh century, relations with Ne-pal became close and cultural exchange between the two countries intensi-fied. Paśupata yogins and acaryas wandered from Magadha into Nepal tovisit the great shrine of Paśupatinatha, which had developed into a statesanctuary and received substantial financial support from Vatsadevı andher Nepalese husband. The priesthood of this temple was firmly in thehands of a local branch of Paśupatas. They were happy with the growingreputation of their temple. It brought them pilgrims from afar and theircoffers filled accordingly. At the same time the intensive traffic kept them

58 SPS 167.163–87. Below, p. 137.

Introduction 21

up-to-date with new religious developments and informed about the latestliterary productions.

Thus the reputation of the Skandapuran. a spread to Nepal, and friendsin Magadha were asked for a copy. They brought one, naturally a manu-script that contained the insertion mentioning Paśupatinatha in Nepala.The new acquisition was treasured. In order to preserve the text, themanuscript was copied in the century that followed. And so it happenedthat on the twelfth day of the bright half of the month of Caitra in theyear 234 (= ad 810/11) a scribe in Nepal could complete his work onthe Skandapuran. a, a labour that he had undertaken for the sake of theperfection of all beings. It would become our manuscript S1. And, if it hasnot contributed to our perfection, we are certainly the only ones to blame.

The Twilight of the Gupta Empire

Hun.a Attacks and Inner Fragmentation

Skandagupta

The heyday of the Gupta Empire was over when, in ad 456, Skanda-gupta was able to proclaim himself emperor after a protracted war ofsuccession, a struggle which may have lasted for about ten years. As usual,the triumph is expressed through religious metaphor, in which the emperoris compared to the king of the gods, Indra, who is confirmed in his royaloffice by the dynasty’s supreme, tutelary deity Vis.n. u.59

The inscription testifies to the fact that Skandagupta’s authority stillstretched from coast to coast, and that even in the far-off western provinceof Saurashtra he was able to appoint a governor, called Parn. adatta, whowas still willing to accept the emperor’s overlordship.60 However, the sameinscription also obliquely refers to the dangers that had nearly preventedhis accession to power: the Nagas and the Mlecchas.61 The Nagas may have

59 Skandagupta’s Junagar.h Rock Inscription (CII III (1888), 58f. v. 1; Sircar SI I,308):

śriyam abhimatabhogyam. naikakalapanıtam. ,tridaśapatisukhartham. yo baler ajahara |kamalanilayanayah. śaśvatam. dhama laks.myah. ,sa jayati vijitartir vis.n. ur atyantajis.n. uh. ‖‘Vis.n. u, whose triumph is supreme, who has triumphed over pain, the perpet-ual abode of Laks.mı, who is alighting on (her) lotus throne—He is (truly) tri-umphant, when He takes Śrı, i.e. Royal Glory, away from (the demon king) Bali,in order to make the king of the gods (Indra) happy, (Royal Glory) that is his(Indra’s) dear object of enjoyment but that had been denied to him more thanonce.’

Cf. the Kahaum Stone Pillar Inscription of Skandagupta (CII III (1888), 67):śakropamasya ks. itipaśatapateh. skandaguptasya. For the Gupta succession wars seeBakker 2006.

60 Virkus 2004, 60, 72f.61 Junagar.h Rock Inscription of Skandagupta vv. 2–4 (CII III (1888), 59; Sircar SI I,

308f.):tadanu jayati śaśvat śrıpariks. iptavaks. ah. ,svabhujajanitavıryo rajarajadhirajah. |

25

26 Hans Bakker