Episode III: Enjoy Poverty: An Aesthetic Virus of Political Discomfort

Transcript of Episode III: Enjoy Poverty: An Aesthetic Virus of Political Discomfort

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty: An Aesthetic Virusof Political Discomfort

Caitlin Frances Bruce

Department of Communication Studies, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

This article considers Renzo Martens’s controversial 2008 film, Episode III (EnjoyPoverty). Martens’s film is a conceptual film that satirizes documentaries about povertyin Africa by exposing the ways in which consumers of poverty images enjoy such images.It argues that the film, which creates troubling identifications and disidentifications fora Western spectator, offers a politically productive lesson on the power of discomfort todisrupt unethical image practices. Communication studies scholars have engaged in theseconversations via studies about identification and disidentification and the documentarygenre; affect in cinematic media; and more directly, through work that investigates theperils of cookie-cutter frames for representing (racialized) poverty.

Keywords: Identification, Disidentification, Documentary Film, Affect, Photography,Sentimentality, Politics of Representation.

doi:10.1111/cccr.12109

“To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means puttingoneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and,therefore, like power.” Susan Sontag, On Photography (1977)

Susan Sontag’s opening salvo in her landmark essay, On Photography, encapsulatesa longstanding anxiety about photographic practice. To picture the world is to have(or believe one has) power over it. Moreover, the passage implies that belief in suchknowledge feels powerful, yet, such agentive inflation involves an act of unsanctionedcapture. Thus, in Sontag’s view, photography occupies a slippery ethical location and,at best, a questionable epistemological one. From the muckraker journalism of JacobRiis and fellows photography has played a key role as political and documentary tech-nology, relied upon heavily to promote humanitarian aid projects (Chouliaraki, 2010;Manzo, 2008), using images as forms of evidence with the implied belief that seeingcan be tied to action. Lamentably, such well-intentioned practices frequently serve to

Corresponding author: Caitlin Frances Bruce; e-mail: [email protected]

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 1

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

bolster or foster disidentification on the part of a socially distant spectator with respectto the marginalized photographic subject. By disidentification I mean the reinforcedperception of social distance and difference. Such disidentification, T. J. Demos andHilde Van Gelder (2013) and Reginald Twigg (2008) have argued, produces an expe-rience of pleasure or enjoyment in spectators. Such pleasure can be derived from theself-righteous feelings of pity that such images may evoke, as well as from gratificationinsofar as such images reinforce the privilege and distance from suffering on the partof the viewer.

The documentary film, in particular, about Africa as a scene of suffering (Klot-man & Cutler, 1999; Murphy, 2000; Ukadike, 2009), offers an exemplary genre wheretechnologies of representation, sentimentality, identification, and disidentificationcome into play, and this genre has received substantial scholarly attention (Bruzzi,2006; Colleyn, 2009; Ruby, 2000; Spence & Navarro, 2010). In this article, I investigatea film that inhabits the documentary impulse in order to transform it (Minh-ha,1990). Renzo Martens’s 2008 film, Episode III (Enjoy Poverty), is a conceptual filmthat satirizes documentaries about poverty in Africa by exposing the ways in whichconsumers of poverty images enjoy such spectatorship. Communication studiesscholars have obliquely engaged in conversations about the politics, affect, and ethicsof witnessing the suffering of another via studies about Burkean identification anddisidentification (Biesecker, 1997); affect in cinematic media (Irwin, 2013; Ott, 2010);and more directly, through work that investigates the perils and possibilities ofrepresenting suffering (Bell, 2008; Chouliaraki, 2010; Shome, 1996) or representing(racialized) poverty (Parameswaran, 2009; Twigg, 2008). This film in particularis a compelling object for communication studies because it not only criticizeshumanitarian and documentary forms, but it also literally enacts those very regimesthat it criticizes to generate discomfort. The film triggers an effect of disgust inaudiences and critics—evident in Paul O’Kane’s observation that the film “gets underone’s skin,” Demos’s claim that it “haunts,” and blogger Koen’s complaint that it is“uncomfortable,”—disgust that propels its ongoing circulation in blogs, journals,and art magazines.

From its opening scene, Enjoy Poverty is a study in discomfort. Interviews are car-ried out with painful transparency; self-important monologs trail off into silence andwandering camera shots; images of fragile and broken African bodies are displayedto pornographic effect; while vulture-like media agents, as well as humanitarians, aredisplayed at their most Machiavellian. The film yields an alienating palimpsest of dis-aster pornography, documentary realism, and surrealist high art. But for whom doesthe film incite discomfort? Lest the viewer be unsure, Martens insists at key juncturesthat the final product will be in English and shown in Europe for a White and affluentaudience that is socially and spatially distant from the manifold scenes of sufferingin which Congolese subjects of the film are situated. Following the reflexive practiceof cineastes such as Jean Rouch and Trinh Minh-hà, Martens refuses the feel-goodapproach that he believes infuse aid and documentary photo regimes by exposingthe self-interest that underwrites sentimental approaches to representing poverty,

2 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

no matter how well intentioned. In the film, we follow Martens to villages, refugeecamps, plantations, gold and oil prospecting ventures, an art gallery, and a WorldBank meeting, each illuminating different facets of structural poverty in the Demo-cratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Through this cinematographic collage, Martensexplores the Congolese individuals’ subjective experience of poverty as well as thedifferent responses to poverty that range from bald indifference, to well-intentionedaid, to depoliticizing pity. However, the process of creating such a spectacle forWestern eyes is not simple documentation, but rather involves reproducing feelingsof chronic disappointment to be experienced by Congolese subjects.

Enjoy Poverty exposes the ethical quandaries that arise in visual encounters withpoverty on the part of a privileged, often Western subject. In viewing poverty, oneoften experiences a pleasurable sense of disidentification—the recognition that thesubject on display is economically and socially other, but also a sense of identificationwith the anticipated subject position of spectator and potential humanitarian donor.This communicative function of identification and disidentification has been exploredin rhetorical studies where scholars have challenged common-sense understandingsof identification as simple audience acceptance or agreement. For instance, BarbaraBiesecker explores Kenneth Burke’s influential identity-division dyad, arguing that“Identification does not, however, produce a unity in the proper sense of the word,”evident in Burke’s own argument that to think about identification is “to confront theimplications of Division” (Biesecker, 1997, p. 48–49). Instead of promoting a restoredsensus communis, identification is part of the work of the social that is a continuallyunfolding chain of differences, a “catachresis [misnaming].”

In this reading of Martens’s film, disidentification is more ambivalent than plea-surable, and identification shifts from being a guarantee of cathartic communion to anindication of culpability. Instead of trying to reduce distance, or inspire identification,Martens turns the process of disidentification into an uneasy experience by high-lighting the pleasure in such viewing transactions, a phenomenon that is frequentlyeffaced. The film renders the distance between poor and privileged subject even moreunbridgeable by calling into question the spectator’s capacity for agentive and repara-tive action, forcing them to reidentify with several unsavory characters in the film,such as donor, plantation owner, opportunistic photojournalist, self-interested aidworker, and cynical prospector.

In this article, I suggest that the film, a scandalous work of artistic egoism, offersa tentative political strategy of discomfort that has potential political and even ethicalpurchase. The film offers an aesthetic and political critique that works as an affec-tive virus that is not easily satisfied or expunged. To develop this argument, the essayunfolds in four parts. First, I situate this study among discussions in documentarytheory and communication studies about reflexive documentary and humanitarianrepresentations of suffering. Second, I discuss the narrative arc of the film in whichMartens illuminates but also participates in perpetuating misery. Third, by investi-gating critical receptions of the film, I suggest that the pattern of responses (mostlynegative and angry) indicates that the film works along an infection model as a kind

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 3

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

of aesthetic virus. Fourth, I conclude with a discussion of the political potential thatthe film germinates as an enactment (and critique) of what Lauren Berlant (2011)describes as cruel optimism, an alternative that allows for the possibility of more equi-table relationships with photographic subjects as subjects (and not objects) of aid, butonly insofar as such practices are taken with a substantial grain of discomfort.

Reflexive documentary and humanitarian representation

From its beginnings, documentary has been a difficult to define genre. Often definedin the negative, as a “non-fiction film” (Bruzzi, 2006, p. 6), documentary can rangefrom impersonal narrations of human and natural landscapes, to intensely subjectiveengagements with an individual or individuals’ lives. In the space afforded here, it isnot possible to fully account for the range of practices in documentary from 1926 tothe present, nor the critical discourse that has surrounded it. For the purposes of thisessay, documentary refers to a nonfiction film that is “predicated upon a dialecticalrelationship between aspiration and potential… between the documentary pursuitof the most authentic mode of factual representation and the impossibility of thisaim” (Bruzzi, 2006, pp. 6–7). Martens’s film is a kind of art-documentary, an increas-ing trend in the art world that evinces yet another key element of the documentaryimpulse, the potential for documentary to be a means of political worldmaking. Inthis model, documentary filmmaking is a public sphere activity where those on themargins can articulate new or different interpretations of reality, “one of the formsthrough which new attitudes enter wider circulation, through… the articulation ofthe social actors who participate as subjects” (Chanan, 2007, p. 7).

Martens’s film critiques this political aspiration of some documentary practice,and my analysis of Enjoy Poverty contributes to conversations about how one canimagine the documentary’s role as a social and political resource (Bell, 2008; Chanan,2007; Hermansen, 2014; Irwin, 2013; Lancioni, 1996; Nisbet & Aufderheide, 2009).Enjoy Poverty elicits affects of discomfort in audiences and challenges their agencyas members of a public sphere. In so doing, it exhibits Bruzzi’s characterization ofdocumentary as a “performative” practice of aspiration coming up against limitationsof the apparatus.

Martens’s film can be characterized as a “reflexive” documentary (Nichols, 2001)because it makes explicit the performative and constructive character of the filmitself, spotlighting the role of the filmmaker as author who produces a particularizedmodel of truth. This reflexive mode shares a critical perspective with another schol-arly tendency that provides an implicit frame for Martens’s work, critiques of shockapproaches to humanitarian witnessing as well as skepticism about rosy representa-tions of suffering populations. Lille Chouliaraki (2010) charts these dual tendencies incommunication studies approaches to humanitarian representation, pointing to themove from “shock politics” to a more contemporary approach that can be character-ized as a “post humanitarian” style of appeal that “privilege[s] low-intensity emotionsand short term forms of agency” (p. 108). The two approaches, grand emotional appeal

4 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

and more modest suggestions (liking a page on Facebook, for instance) also evincetwo understandings of the political. The former, based on Enlightenment, Universalistmorality approach links “justice with pity,” while the latter, in avoiding pity, also avoidsquestions of justice. The language of “grand suffering” in the shock politics model,however, paradoxically undermines justice, claims Chouliaraki, by collapsing thepolitical into the social, avoiding long-term assessments in favor of short-term crisismanagement. Communication studies of humanitarian discourses and representa-tions (Aradau, 2004, p. 277), Chouliaraki clarifies, can be understood as “a historyof the critique of its aesthetics of suffering,” which criticizes both the “emotions ofguilt and indignation” that align with “‘shock’ aesthetics” as well as “the emotions ofempathy and gratitude associated with the ‘positive image’ campaigns” (2010, p. 110).

Both approaches, shock and positive image, rely on a “documentary mode.”In shock approaches, however, the content is largely of suffering, characterized bystarving children, damaged bodies, with a “lack of eye contact” that incites a voyeuris-tic gaze (Chouliaraki, 2010, p. 110). This representative mode reinforces distancebetween the spectator and the suffering body (Chouliaraki, 2010, pp. 110–111).Positive image appeals, on the other hand, “focus on the sufferer’s agency anddignity,” individualizing suffering and emphasizing sufferers as “participants indevelopment projects” as well as personalizing the relationship between donor andrecipient through practices like child sponsorship (Chouliaraki, 2010, p. 112). Bothapproaches can have perverse effects. Shock approaches can mire the spectator intoinaction from guilt and shame, and the latter, in avoiding these affects, can ignorespectator complicity that perpetuates practices that drive suffering (Chouliaraki,2010, p. 114). The “post-humanitarian” move, then, is when some NGOs use brand-ing campaigns that focus less on those who suffer and more on the feelings of donors.It is, Chouliaraki cautions, a “political culture of communitarian narcissism… thatrenders the emotions of the self the measure of our understanding of the sufferingsof the world at large,” or a sort of simple identification model that ignores how the“public circulation of emotion and action” is “inscribed in systematic patterns ofglobal inequality… hierarchies that divide the world into zones of Western comfortand safety and non-Western need and vulnerability” (pp. 120–121). It is preciselythis unequal economy of emotion that Enjoy Poverty activates through repertoires ofreflexive documentary, photographic realism, and the repetition of such “shock” and“positive image” approaches within a larger frame of satirical narcissism.

Enjoy Poverty: Moving from photographic promise to photographic crueltyin the imaging of poverty

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty, directed and produced by Martens, is the product of 2 yearsof filming across the DRC. It opens with an image of a plantation field over the diegeticsounds of a worker cutting foliage. Laboring under a blindingly bright sun, he explainsto the camera how 3 days of work amounts to little more than half a dollar. This firstscene is cut to another, in a refugee camp, covered with UN logos, where smiling aid

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 5

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

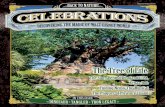

Figure 1 Martens in Fishing Village. Renzo Martens, Episode III, 2008 (Film Still). Courtesyof the Artist and Galerie Fons Welters

workers both distribute blankets and gleefully take photographs of their colleagues’efforts. The grinning Caucasian aid workers offer a sharp contrast to the malnourishedand grim African bodies that serve as objects of aid and photography. The camerazooms in on the lower body of a UN soldier, blue helmet held in the same hand thatrests lightly on a machine gun. Thus, in the first 5 minutes of Enjoy Poverty, through aseries of “contrasts and contradictions” (Spence & Navarro, 2010, p. 175), we see thatplantation labor, unequal processes of image making, aid apparatuses, and militaryinstitutions are linked together as integrated components of a system that is fuelledby poverty, producing kinds of enjoyment.

The third scene features Martens as protagonist and primary object. The spectatoris transported to a boat, the scene captured by a shaky, handheld camera. Disembark-ing from the vessel a second hand-held camera zooms in on Martens’s face, sweaty,pale, and covered in a straw hat. Behind him the Congolese fishing village becomesmere background (Figure 1).

Martens blinks sweat out of his eyes, and is followed by three Congolesepack-bearers, who carry heavy metal boxes atop their heads. Martens states, to thecamera, or to himself, underscoring the reflexive character of the film: “You cannotgive them anything they do not already have. You have to empower them… theworld has changed… [there are] new markets, new opportunities.” In this scene,Martens is revealed to be a sort of avatar for Western, neoliberal savior figures whoattempt to teach locals to escape from misery, a cinematic trope with a long history(Shome, 1996). He also parrots an “empowerment” discourse that mimics NGOproclamations (Chandler, 2001).

The film is readable as a documentary, in large part, because of the key rolethat interviews play as forms of evidence (Spence & Navarro, 2010). After visitinga site with international photographers who photograph militia members’ corpses,Martens interviews an Italian photographer for Agency France Presse (AFP). Thisconversation later serves as an evidentiary frame for Martens’s “lessons” for localphotographers. The photographer explains to Martens that he receives 50 euros

6 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

per image and 300 euros per story, an image market driven by “supply and demand”for negative imagery of death and dying, underscoring the film’s critique of the“shock” approach to humanitarian documentation. As the photographer edits imagesof corpses on his computer, Martens asks. “Who is the owner…Whose property arethe pictures…And the people that you have photographed… are they the ownerstoo?” “No, because I took the pictures,” the photographer retorts, matter of factly.Martens presses: “But they make the situations that create the picture.” The responderreflects, “But I make of that situation a picture… there are thousands of situations, tomake of a situation a picture makes that picture mine.” This central scene underscoresthe unequal relations that structure nearly every photojournalistic or humanitarianencounter in the film and we have come to the crux of the film’s critique: Thesituations that provide the raw material for photographs and images of suffering,that justify the massive flows of development aid that amount to a greater percentof the DRC’s Gross Domestic Product than gold, coltan, and oil, are not consideredthe property of those represented. The moment of photographic decision, electedby the photographer, figures as sovereign. In the AFP photographer’s argumentsa picture of the common-sense approach of the media regime emerges, one thatprivileges photographers and not subjects. Instead of a civil contract of photography,what philosopher Ariella Azoulay (2008) describes as the triangular relationshipbetween photographer, subject, and spectator, where each party takes part in anongoing negotiation over meaning, the subject is cut out, and the image becomes aspace of exchange for only the photographer and the spectator. This situation also isa metaphor for the unequal power relations involved in constructing a documentary,where, even though the genre implies a robust relationship between filmmaker, socialactors, and audience, we instead see at every juncture of Enjoy Poverty the agency ofthe social actor being mitigated.

Martens uses this information to formulate the lesson he delivers to a group oflocal photographers in a schoolhouse, taking on the role of messianic Western figure.Dramatically written on a whiteboard is the question: “A qui appartient la pauvreté?”Martens expounds,

The fundamental question is: to whom does poverty belong? If it can be sold, it isimportant to know who the owner is… Since it brings in money, donors, andeven individuals…You are not only the beneficiaries of the good will of others,of NGO’s and agencies that come to help you, [to whom] you should be endlesslygrateful. No. You are also actors, important actors in this world. If poverty is likea gift that creates deeper understanding, you also give it back to the world.People come to visit you. It is something that makes us happy…There willalways be people visiting you, taking pictures, supposedly fundingprojects… Let’s say they will have freely captured your poverty while you don’tbenefit too much. It’s a resource.

In this lesson, Martens exhorts local photographers to take hold of their agencyas “important actors in the world” who are partners, not just beneficiaries, a

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 7

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

Figure 2 Kanyabayonga Photographers in Hospital. Renzo Martens, Episode III, 2008 (FilmStill). Courtesy of the Artist and Galerie Fons Welters

performance of the “positive image” approach to humanitarian representation. Inplain terms, he describes the experience of viewing poverty by a Western subjectas an experience of being made happy. We are reminded of the aid workers in earlymoments of the film who gleefully take photos of refugees as they hand out blankets,their enjoyment visceral and visible. The local photographers, who own a photoshop that specializes in celebrations (birthdays, weddings, etc.), are accustomed toa photographic economy that privileges moments of happiness. However, in light ofthe conversation with the AFP photographer, we the viewers know that positive pressdoes not sell, and, thus, Martens endeavors to persuade the local photographers toshift from positive to negative subject matter, a performance that brutally caricaturesthe “shock” or disaster pornography approach to journalistic and humanitarianimage making (Chandler, 2001).

Again, at the Whiteboard, Martens highlights profit over positive content andposits that the two photographic genres that one can partake in are of celebrations andwar. He explains that were they to act “rationally” local photographers would be pho-tographing suffering, explaining that photographers make one dollar a month pho-tographing parties, but 1,000 a month photographing “the option of raped woman,cadavers and malnourished children.” Martens brings his students into the field, vis-iting a plantation and a clinic. In the clinic, two malnourished children sit on a cotcrying (Figure 2).

“You must choose the worst cases,” he urges, pantomiming photojournalistic eco-nomic imperatives. The doctor takes the children’s clothing off in order to showcasetheir protruding ribs, scapula, and distended bellies. After the lesson Martens unpacks(for a second time) the metal boxes with which he has travelled. Inside are fluorescentlights in the shape of letters that, when mounted on a sign made out of crosshatchedsticks, and powered by a mobile generator, reads “Enjoy Poverty” with “please” blink-ing in a smaller font between “Enjoy” and “Poverty” (Figure 3).

8 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

Figure 3 Enjoy Poverty Celebration. Renzo Martens, Episode III, 2008 (film still). Courtesy ofthe Artist and Galerie Fons Welters

It is dusk, and villagers have gathered around Martens. He announces: “Youare… the people that aid the rest of the world… Africans are taking charge of theirown resources.” The villagers clap and he turns on the sign and a celebration begins.Here, this paradoxical injunction to represent the photographers as agents, a kind of“positive image approach” is sustained through the repetition of shock images by theCongolese themselves.

In this first movement of Martens-as-savior, we are offered an optimistic visionof what can take place when the Congolese take hold of their own situation. Yet, thisfeeling of elation is soon disrupted. In the following scene, Martens brings the localphotographers to meet with a Mr. Fred of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to try toget press passes for MSF hospitals. Seated around a low table, Martens explains toMr. Fred that the photographers of Kanyabayonga have learned that there is moremoney in poverty than parties, and they would like press passes in order to take pho-tographs in MSF hospitals. Unsurpisingly Mr. Fred is taken aback, angrily respondingthat the MSF is not there to “make an exhibit of…misery,” clearly troubled by theidea that the photographic economy of misery might infect discourses of good willand MSF ideologies of “humanitarian witnessing” (Givoni, 2011). Martens retortsthat international photographers do the same thing, selling their photographs of suf-fering. Mr. Fred shifts tactics, first arguing that international photographers “makenews, not money,” and then criticizes the aesthetic flaws in the local photographers’sample images, conveying the hypocrisy at work in Western media-aid apparatuses.In trying to enable the Kanyabayonga photographers to benefit from their own mediarepresentations, and failing in the face of unequal power relationships, Martens illu-minates, painfully, how a just civil contract of photography is structurally undonethrough self-serving humanitarian aid regimes that largely benefit Western denizens.At the end of the meeting, walking along a dusty road, Martens turns to the local pho-tographers and flatly states: “I think it will fail. You do not have a press card, you donot have internet access… I have the impression there are many obstacles.” The local

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 9

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

photographers are crestfallen, mouths open, shoulders hunched, they stare off intothe distance and then walk away aimlessly in different directions.

Did Martens ever think his endeavor would succeed? Before coming to Kanyabay-onga he reveals multiples scenes of structural inequality, all pointing to the fact thatthe poverty of the Congolese is enjoyed specifically when they are positioned as vic-tims and objects of aid, not subjects of their own future. Martens could have predictedsuch an outcome from the beginning. So why the cruel, and narcissistic, demonstra-tion? The lesson for the photographers is yet another form of demonstration for thefilm’s viewers, one that works based on the cruel experience of disappointment by theCongolese photographers. This demonstration of disappointment happens at otherjunctures in the film. During a third celebration around the “Enjoy Poverty” sign,Martens tells the plantation worker shown at the opening of the film that he will neverescape poverty. The hurtfulness of such a statement is evident, as the man’s featuresslacken, his eyes widen, and he is rendered speechless. Martens explains:

Martens: “If you are going to wait for your salary to increase so you can be happy,you’ll be unhappy your whole lives.”

Man 1: “We’ll gladly accept whatever you can do for us when you get back.”Martens: “There is nothing prepared.”Man 1: “There is nothing prepared?”Martens: “There is nothing prepared.”Man 1: “Once you go back, you can’t deliver reports?”Man 2: “Why did you come here?”Martens: “To tell you [that] you better enjoy poverty, rather than fight it and be

unhappy. Do you want to remain unhappy all of your life, because of poverty? Youneed to accept things the way they are. Be happy despite poverty… If you accept whatyou cannot change you can have a bit of peace in your hearts and minds.”

Man 3: “Will you project the film here?”Martens: “The film will be shown in Europe, not here.”Man 1: “We accept poverty… and will be happy despite it.”Martens: “Experiencing your suffering makes me a better person. You really help

me. Thank you.”

This scene takes place in the glow of the “Enjoy Poverty” sign at night on a beach. Inthis third scene, Martens performs a reversal of the meaning of the sign: The Con-golese must enjoy their poverty as destiny rather than profitable resource. The usualprocedures of humanitarian aid, which involve collecting data, creating reports, allof which Martens has done, are rendered meaningless. “There is nothing prepared,”he emphasizes. The “nothing” is not a lack of a material, but absence of belief in thepromise of data collection and reparative action. The film too is “nothing” in this sec-ond sense, it is ineffective, purely a vehicle for enjoyment. Moreover, the tacit (but, perMartens, erroneous) belief that the contract of taking pictures or images of the poorin some way benefits them is disrupted. The film will never be shown to those whocreate the situation that enables Martens to make an image. In a final blow, Martens

10 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

expresses that he benefits from the vicarious experience of suffering, an asymmetricalenjoyment from which the Congolese can never fully benefit.

The scene is profoundly discomforting, revealing that it is not quite “nothing,”because we witness not only optimism being shattered, but also the persistence ofan unequal power relationship even after its promise of rescue has been revoked: theinfectious nature of humanitarianism, repeated and mutated by Martens. Martens,standing in for exploitative aid and image regimes, demonstrates the perversity of asystem where those who are the most subjugated must enjoy their position of subor-dination and affectively buy into it. The three men quickly adopt his proposition: “Weaccept poverty… and will be happy despite it.”

Uncomfortable viewers: Disidentification, reidentification, and disgust

Paul O’Kane observes that Martens’s film “gets under everyone’s skin” (2009, p. 813).Indeed, in the blogosphere following the release of the film, viewers describe theirexperience as one of shock, offense, and discomfort. On May 11, 2009, Nikolaj Niel-son posted a review of the film on the blog “Human Rights: A World Affairs BlogNetwork,” a subsidiary of a network of global-issues-blogs made up of contributorsfrom “journalism, academia, business, non-profits and think tanks.” Established in2007 as part of the Foreign Policy Association, itself founded in 1918 “by concernedjournalists and citizens,” Human Rights is populated by the very agents that Martens’sfilm satirizes: aid workers, foreign policy experts, NGO members, and journalists.Nielsen glosses the film, noting Martens’s criticisms of humanitarian organizationsand their consumption of poverty and concludes noting that “decontextualization”of agencies such as MSF “will surely offend” (2009). What is notable is the limitedrange of comments in response to Nielson’s piece, such relative silence on the messageboards evidence that the film renders viewers ill, or mute. First, Felani Manu (2009)notes that Martens sparks “offense” because he is challenging “conventions.” Second,Yaco8 (2010) laments that the structural nature of poverty is so entrenched that littlewill change until reductions in Western consumption and collective commitments to“sustainability principles” can take place. Yaco8 continues: “In the meantime, RenzoMartens is right, Congolese may as well get used to poverty and enjoy it,” a cinematicproposition presented in a manner that is “shockingly excellent” (2010). The first post,which notes the sense of offense or scandal Martens’s film elicits, gestures to the per-verse identification that it can induce. As we see in the second post, viewers can nolonger see themselves as benevolent donors. Instead of a safe, protected distance, suchdistance is rooted in misunderstanding and incomprehension that is responded to notby dialogic engagement on the basis of equality, but instead interventions that per-petuate injustice. Such difference and disidentification with the poor makes viewerscomplicit in a structure of exploitation, forcing them to assume a troubling reidenti-fication with their position as potential donor.

The film’s infectious nature is evident in two other posts marking the sense ofpowerlessness that it elicits. Koen (2009) states: “Hate it or love it… just watch it. And

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 11

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

then, well, go do something meaningless like writing a post on some internet site.”The film produces the proliferation of yet more empty gestures, an uncontrollablerepetition. Ernie responds (2009): “I came across this movie on TV but the sceneit just showed was the little boy discovered dead. I couldn’t bear it… So here I go,Koen, doing something meaningless—shedding my tears and postin [sic] this one.Peace.” Repeating a sense of political impotence, Ernie’s gesture seems to be one ofthe primary effects of the film. It generates a sense of stuckness and deflation. The“shocking” nature of Martens’s film lies in its “scandalousness and exploitation [that]perfectly mirrors the scandalousness of exploitative relations of power between theCongo and the West” (Downey, 2009, pp. 599–600).

It is telling that a film that performatively repeats humanitarian documentary con-ventions also inspires repetitive lamentation. Martens elaborates:

Episode III doesn’t critique by showing something that is bad, it critiques byduplicating what may be bad… So, the critique in the film is… the film as awhole… the copy in a way of existing power relationships…Most documentaryfilms critique, or reveal, or show some kind of outside phenomena, like oh this isbad, or this is good, or this is tragic… In this film, it is not the subject that istragic, like poverty in Africa, it is the very way that the film deals with the subjectthat is tragic. (Penney, 2013)

Martens’s definition of documentary as “oh this is good… this is bad… this is tragic”is oversimplified and ignores over 50 years of reflexive documentary practice. Per-haps this is a deliberate omission, meant to magnify the outrage the film creates. Weare left wondering if this comment is made by Martens the filmmaker or Martens thenarcissistic antihero of Enjoy Poverty. Martens’s claim that the critique of the film isits “duplication” and “copy” of unequal forms of power relations along with its queasyreception on message boards, suggests that the film circulates virally in both sensesof the word: as a kind of virus that is infectious, but also viral in how it prolifer-ates, replicating itself through media apparatuses (Lukes, 2012). Sampson observesthat virality implies contagion, rapid transportation, and vulnerability. But it is alsoa nonrepresentational or prelinguistic force that works affectively, proliferating feltstates that shape subjectivities (2012, pp. 2–6). Reduplication requires an operationof repetition, and Enjoy Poverty repeats and marks rather than escapes the forms andpractices that Martens believes constitutes humanitarian documentary filmmaking.However, in repeating conventions it also brings into being a monstrosity that inhab-its a genre rendering it strange, showing the very ugliness of the convention itself andperhaps having the effect of infecting (with skepticism) other documentary films. Wecan see how this affective virality works on other films, such as Silverlake Life (1993),or Nuit et Brouillard (1955), where watching the films is to endure emotional suffer-ing. However, in both films painful watching is linked to an explicit endorsement ofa kind of witnessing done on behalf of the social actor. Resnais and Joplin ascribeethical import to witnessing qua watching, while Enjoy Poverty frames watching asexploitative.

12 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

It is not surprising then that Enjoy Poverty inspired anger and outrage. Referred toas “condescending,” one blogger notes that the film’s approach “generally isn’t some-thing I enjoy” (Kenzie, 2009). Such reactive statements attest to the viewers’ expecta-tions about documentary being violated. Although the film’s title demands enjoyment,in the imperative tense, the viewer’s experience is the opposite. Another commentreinforces this claim, noting: “That made me feel very uncomfortable” (Afro-EuropeInternational, 2010). Enjoy Poverty incites discomfort, anger, and refusal, disidenti-fication instead of cathartic identification. However, these noncathartic affects, “uglyfeelings” (Ngai, 2009), function as important element of politics, affective indexes ofthe uneven distribution of emotion that is masked by sentimentality.

Martens characterizes such discomfort as an effect of demystification. FollowingSusan Sontag, he is skeptical of the “potential of showing the suffering and pain ofothers in images” because, Sontag argues, it creates a fantasy of a “a link between thefaraway sufferers—seen close-up on the television screen—and the privileged viewerthat is simply untrue.” Sympathy, per Sontag, also masks the viewers’ role in the roleof causing suffering, putting off a reflection on “how our privileges are located onthe same maps as their suffering, as the wealth of some may imply the destitutionof others, is a taste for which the painful, stirring images supply only an initial spark”(Roelandt, 2008, p. 6, quoting Sontag). By inciting outrage, anger, and frustration, andother forms of disidentification, the film disrupts economies of sympathy, and perhapsdangerously excludes considerations of justice, which, contra Sontag and Martens,theorists like Luc Boltanski (1999) link to particular experiences of pity.

The film’s challenge to the usual normative rubrics of identification and disiden-tification operative in disaster imagery invites us to challenge the prioritization of(comfortable) identification over disidentification in communication studies morebroadly. It raises the question of what it would mean to craft a visual rhetoric of suffer-ing through nonfictional documentary that grapples with the inevitable productionas well as representation of suffering victims. By changing identification from a spaceof resolution, to a space of ambiguity, Enjoy Poverty elicits moments of disidentifi-cation and identification for viewers that are described as condescending, insulting,paralyzing, or scandalous. The “condescending” tone of the film and its gross over-simplifications of both humanitarian practice and documentary genre are rooted inits form. Martens locates himself in a tradition of satirical critique, following JonathanSwift’s A Modest Proposal (Roelandt, 2008). The viewers are also objects for critique,and are brought into the frame through the visible body of the filmmaker, and ire atthe character of Renzo is gradually revealed to the viewer to be “the quintessentialsymptom of our own refusal—witting or unwitting—to acknowledge complicity inthe reality of poverty” (Ersoy, 2011, p. 398). This circuit of rage, disidentification,and then gradual identification by viewers with Martens’s character may cause asuspension in the easy operation of liberal identification and sympathy, in itself apolitical act.

The Congolese photographic subject is not constructed as a knowing coparticipantin the imagistic scene. Instead, power rests on the side of the photographer and the

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 13

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

spectator. Nevertheless, the film constructs, as if it were a photographic negative, aspectral image of what a more just civil contract of photography may be. T. J. Demosenthusiastically explains that Martens literally and metaphorically trains the cameraon himself, the “key target of the film… a kind of reverse photojournalism, or reversedocumentarism, one that centers on the documentarian-artist-photojournalist, whois normally hidden in such projects” (Demos, 2013, p. 8). Even so, other modelsof documentary, notably, indigenous cinema and reflexive documentary, engagesocial actors as authors without necessarily reducing them to victims. Martens’sfilm appears pessimistic about such a possibility. Indeed, Enjoy Poverty argues thatthe investments that structure humanitarianism and its normative discourses andpractices of avaricious resource extraction, crisis-based aid regimes, donor-biasedaid systems are coconstitutive. Thus, instead of a progress narrative, the film createsmoments in which aspirations fall apart, affective scenes that have been described bytheorist Lauren Berlant (2011) as cruel optimism.

Constructing an uncomfortable alternative: Discomfort as politicaland ethical strategy

Lauren Berlant has argued that “an optimistic attachment is cruel when the object[or] scene of desire itself is an obstacle to fulfilling the very wants that bring peopleto it: but its life-organizing status can trump interfering with the damage it provokes”(2011, pp. 227–228).

Berlant’s diagnosis particularly targets liberal democratic enactments in whichthose on the fringes of the bourgeois public sphere continually reinvest in practicesthat continue their disenfranchisement. However, cruel optimism also may includeother pernicious attachments, including narratives of upward mobility while in a sit-uation of structural poverty. In the first two celebration scenes in which Martens’ssign is lit, we witness moments when both Martens and the Congolese subjects in thefilm participate in a ritual of recommitment to the normative tenets of aid regimes,regimes that ostensibly perpetuate exploitation. The film produces and implicates thespectator as a guilty member of a regime of cruel optimism, mirroring such a systemby reproducing disappointment. Given the politically depressing morass that the filmwitnesses and induces, what alternatives are offered esthetically, ethically, or politicallyby Martens’s project?

Thomas Keenan suggests that the film demands more than “response and nonresponse,” but rather, “asks us to make [a] much more subtle distinction about thepossible ways of responding to a situation that calls to us” (Keenan et al., 2013, p. 22).Keenan’s commentary casts the film as a metalesson in response and responsibility. Ina Derridean tenor, one’s response is both inevitable, and impossible (Derrida, 2007).The film leaves the spectator guilty, anxious, and with a sense of powerlessness, yet,in its very virality and the difficulty of exorcizing the images and affects that the filminduces it guarantees a more durational disruption in the circuit between humanitar-ian/documentary discourses and positive feeling, challenging the short-term nature

14 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

of shock and positive image regimes. The viral nature of the film helps guarantee itseffectiveness as a demand for critique. Demos elaborates:

[Images in Enjoy Poverty haunt]… precisely because we as viewers can donothing about the tragedies; we can only confront the impotency of theempathetic response… it’s not enough that these images should be stoicallyembraced…we need to critically address the larger economic and politicalcauses of such suffering, and thereby exorcize the ineffective strategies and breakthe spell of the haunting. (2013, p. 118)

As Demos articulates, the film troubles empathetic response. It forces the viewer tochallenge sentimental approaches to international aid and image making, acknowl-edging limits to understanding and the need for openness to a greater variety ofimages. The film does not just offer lessons of hopelessness to the Congolese, it offersa lesson about being a critic and analyst of normative discourses that perpetuate crueloptimism. Martens’s work is an exegesis of the critic’s role as an analyst of interna-tional idioms, images, and affects that impact distributions of voice and agency. Itis a call to be attentive, and to recognize oneself as implicated in the constructionsof situations that make up the violent photographs to which we are too often morethan accustomed. An aesthetic of misery that is infectious and impossible to shake,“haunting,” per Demos, “under your skin,” for O’Kane, destabilizing and affectivelydistancing per Luntumbue (2013), and “uncomfortable” for Koen. Enjoy Poverty,produces a politically productive sour taste in the mouth of spectators that maymake them pause and reflect more critically when confronting feel-good frameworksfor international image-reception, and aid regimes. As an infectious supplement tothe lessons of Cruel Optimism (Berlant, 2011), Enjoy Poverty draws a geopoliticalas well as an affective map of the relationships between humanitarian discoursesand investments in upward mobility, implicating the Western viewer and aid workerin perpetuating cruel optimism for the Congolese. By constructing a geneaologyof where such optimism is derived, how spectators are also producers of the verynarratives that inevitably disappoint, the film offers a vehicle for rewriting suchnarratives, and an aesthetic method for infecting them. As a complement to Berlant’stheorizations, it suggests rhetorics of painful identification, uneasy disidentification,affective distancing, and even mendacity as reparative means to create space forother narratives. And yet, despite its discomfort, watching Enjoy Poverty feels likeknowledge that feels like it might mobilize a different kind of power, or, to putit another way, despite Martens’s qualms about humanitarian documentary andimagery the film itself feels toward a new relation to power and knowledge. Morehumble, more durational, more caustic, and yet, a negativity that imagines the imagebeing otherwise. A sentinel, a phantom, a reminder, a ghost—it is not a nothing thatis prepared but a something of potentiality.

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 15

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

Conclusion

In this article, I have attempted to map, through audience reception and critical anal-ysis of the film’s affective structure, how Enjoy Poverty offers a political strategy ofdiscomfort that is a corrective to representations of suffering that elide structures ofinequality and mask the affects of enjoyment that spectators may experience. Limitsof this study include the impossibility of following all of Enjoy Poverty’s antecedents,notably, the multiple documentaries and humanitarian visibility campaigns that thefilm mimics or critiques, due to the breadth of the documentary genre. There are manyfilms that both occupy and stretch the limits of the genre. I focus on Enjoy Povertybecause it performs elements of shock as well as positive image promotion and yetrests comfortably in neither mode of nonfiction filmmaking.

Moreover, due to the film’s subject matter and its relative recency, audienceresponse is limited, although I suggest that this can function as evidence of the film’simpact—it temporarily takes words away. Like many esthetics that use satire or irony,Enjoy Poverty runs the risk of being read literally, or taken as yet another instance ofdisaster pornography (Moeller, 1999). To follow these potential reactions, drawingon how the film circulates—where it has been shown, how it has been transmittedto place-based audiences as well as virtually, and its life in academia—will alsoprovide fruitful areas of future research. It also gestures to growing scholarly interestin scrutinizing the blogosphere as a space for public communication, a virtual spacethat audiences negotiate and make meaning of documentary. This piece contributesto such a trajectory by focusing on audience reception, “how people actually argue,construct, and contest the media worlds in which they live and why they do or donot matter” (Putnam Hughes, 2011, p. 211 [emphasis in original]), serving as acontribution to scholarship in communication and cultural studies on documentary,the reflexive mode, and humanitarian representations of suffering. Finally, this pieceprovides a means to link rhetorical studies with communication and cultural studiesin general by attending how affective practices of identification and disidentificationare induced by filmic practice. The film, despite its clear ethical and political pitfalls,notably how it dismisses the ethical power in humanitarian witnessing, illuminateshow documentary can activate more ambivalent and sometimes negative affects.These affects of distancing, anxiety, and discomfort that induce reflexivity in audi-ences can force to them to confront the impulse to respond to images of sufferingwith a knee-jerk reaction and put it out of mind. Instead, by mixing shock, positiveimages, and outright cruelty with regard to the expectations Martens the charactergenerates for the social actors in the film, it induces longer-term possessions, or eveninfections in audiences, and raises the question of justice rather than mere sympathy.It redistributes affective agency away from the powerful without neatly relocating itto those bearing the brunt of poverty. Instead it rests somewhere more veiled. Thisincomplete redistribution, a politics of cruel optimism and practice of affective viral-ity, illuminates how reflexive documentary may productively question documentary’srole as a public art that functions in the public sphere. Against Chanan’s optimism

16 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

about the power of documentary, Martens’s Enjoy Poverty is a cruel demonstrationof the limits of such aspirations, a meditation on the promise and perils of docu-mentary itself, not necessarily always resting in the public sphere, but sometimesoccupying a juxtapolitical idiom (Berlant, 2008), a difficult meditation that may be aprecursor to more effective practices. The imperative to “enjoy poverty” mutates intothe queasy after effects of overenjoyment: a lingering unease and persistent drum ofrecollection.

Acknowledgments

C.F.B.’s work focuses on questions of affect, esthetics, and public space. She wouldlike to thank Anjali Vats, Robert Hariman, Michael Mario Albrecht, Sarah MannO’Donnell, and Hannah Feldman for their comments on earlier versions of this essay.

References

Aradau, C. (2004). The perverse politics of four-letter words: Risk and pity in thesecuritization of human trafficking. Millenium—Journal of International studies, 33(2),251–277. doi: 10.1177/03058298040330020101.

Azoulay, A. (2008). The civil contract of photography. New York, NY: Zone Books.Bell, V. (2008). The burden of sensation and the ethics of form: Watching capturing the

Friedmans. Theory, Culture & Society, 25(3), 89–101. doi: 10.1177/0263276408090659.Berlant, L. (2008). The female complaint: The unfinished business of sentimentality in American

culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.Biesecker, B. (1997). Addressing postmodernity: Kenneth Burke, rhetoric, and a theory of social

change. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.Boltanski, L. (1999). Distant suffering: Morality, media and politics. Cambridge, MA:

Cambridge University Press.Bruzzi, S. (2006). The new documentary. New York, NY: Routledge.Chanan, M. (2007). The politics of documentary. London, England: British Film Institute.Chandler, D. G. (2001). The road to military humanitarianism: How the human rights NGOs

shaped a new humanitarian agenda. Human Rights Quarterly, 23(3), 678–700. doi:10.1353/hrq.2001.0031.

Chouliaraki, L. (2010). Post-humanitarianism: Humanitarian communication beyond apolitics of pity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(2), 107–126. doi:10.1177/1367877909356720.

Colleyn, J. P. (2009). Jean Rouch: cinéma et anthropologie. Paris, France: Cahiers du cinéma.Demos, T. J. (2013). The migrant image: The art and politics of documentary during global

crisis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.Demos, T. J., & Van Gelder, H. (Eds.) (2013). In and out of Brussels: Figuring postcolonial

Africa and Europe in the films of Herman Asselberghs, Sven Augustijnen, Renzo Martens,and Els Opsomer (Vol. 14). Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Derrida, J. (2007). A certain impossible possibility of saying the event. Critical Inquiry, 33(2),441–461. doi: 10.1086/511506.

Downey, A. (2009). An ethics of engagement: Collaborative art practices and the return ofthe ethnographer. Third Text, 23(5), 593–603. doi: 10.1080/09528820903184849.

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 17

Episode III: Enjoy Poverty C. F. Bruce

Ernie. (2009, December 27). Enjoy poverty. Foreign Policy Blogs. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20110824101428/http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2009/05/11/enjoy-poverty/

Ersoy, Ö. (2011). Review: Episode III: Enjoy poverty. The Journal of the Society of ArchitecturalHistorians, 70(3), 396–398. Retrieved from http://m-est.org/2012/01/07/on-renzo-martenss-episode-iii-enjoy-poverty/.

Givoni, M. (2011). Beyond the humanitarian/political divide: Witnessing and the making ofhumanitarian ethics. Journal of Human Rights, 10(1), 55–75. doi:10.1080/14754835.2011.546235.

Hermansen, P. M. (2014). “There was no one coming with enough power to save us”: Waitingfor “Superman” and the rhetoric of the new education documentary. Rhetoric & PublicAffairs, 17(3), 511–539. doi: 10.1353/rap.2014.0035.

Irwin, M. J. (2013). “Their experience is the immigrant experience”: Ellis Island,documentary film, and rhetorically reversible Whiteness. Quarterly Journal of Speech,99(1), 74–97. doi: 10.1080/00335630.2012.749416.

Keenan, T., Guerra, C., Muteba Luntumbue, T., Martens, R., Demos, T. J., & Van Gelder, H.(2013). Roundtable one: A discussion of Renzo Martens’s Episode III (Enjoy poverty). InS. Augustijnen, R. Martens, & E. Opsomer (Eds.), In and out of Brussels: Figuringpostcolonial Africa and Europe in the films of Herman Asselberghs. Leuven, Belgium:Leuven University Press.

Kenzie. (2009). Silver Docs. Retrieved from http://silverdocs.bside.com/2009/films/episode3enjoypoverty_silverdocs2009;jsessionid=184596DAA928D998439401355BF770D1/

Klotman, P. R., & Cutler, J. (Eds.) (1999). Struggles for representation: African Americandocumentary film and video. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Koen. (2009, November 19). Enjoy poverty. Foreign Policy Blogs. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20110824101428/http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2009/05/11/enjoy-poverty/

Lancioni, J. (1996). The rhetoric of the frame: Revisioning archival photographs in The CivilWar. Western Journal of Communication, 60(4), 397–414. doi:10.1080/10570319609374556.

Lukes, H. N. (2012). Portrait of the artist as social symptom: Viral affect and mass culture inThe Day of The Locust. Womens Studies Quarterly, 40(1), 187–200.

Felani Manu. (2009, November 11). Enjoy poverty. Foreign Policy Blogs. Retrieved fromhttp://web.archive.org/web/20110824101428/http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2009/05/11/enjoy-poverty/

Manzo, K. (2008). Imaging humanitarianism: NGO identity and the iconography ofchildhood. Antipode, 40(4), 632–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2008.00627.x.

Martens, R. (Director and Producer). 2008. Episode III: Enjoy poverty [Motion Picture].Netherlands: Inti Films/The Image and Sound Factory.

Minh-Ha, T. T. (1990). Documentary is/not a name. October, 52(Spring), 77–98. doi:10.2307/778886.

Moeller, S. D. (1999). Compassion fatigue: How the media sell disease, famine, war and death.New York, NY: Routledge.

Murphy, D. (2000). Africans filming Africa: Questioning theories of an authentic Africancinema. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 13(2), 239–249. doi: 10.1080/713674315.

Ngai, S. (2009). Ugly Feelings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

18 Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association

C. F. Bruce Episode III: Enjoy Poverty

Nichols, B. (2001). Documentary film and the modernist avant-garde. Critical Inquiry, 27(4),580–610. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344315/.

Nielson, N. 2009. Enjoy Poverty. Foreign Policy Blogs, May 11. Retrieved September 1, 2014,from http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2009/05/11/enjoy-poverty/

Nisbet, M. C., & Aufderheide, P. (2009). Documentary film: Towards a research agenda onforms, functions, and impacts. Mass Communication and Society, 12(4), 450–456. doi:10.1080/15205430903276863.

O’Kane, P. (2009). Renzo Martens, Episode III. Third Text, 23(6), 813–816. doi:10.1080/09528820903371214.

Ott, B. L. (2010). The visceral politics of V for Vendetta: On political affect in cinema. CriticalStudies in Media Communication, 27(1), 39–54. doi: 10.1080/15295030903554359.

Parameswaran, R. (2009). Facing Barack Hussein Obama race, globalization, andtransnational America. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 33(3), 195–205. doi:10.1177/0196859909333896.

Penney, J. (2013). The politics of helping others: Interview with Renzo Martens.JoePenney.com. Retrieved from http://www.joepenney.com/index.php?/project/interview-with-renzo-martens/

Putnam Hughes, S. (2011). Anthropology and the problem of audience reception. In M.Banks & J. Ruby (Eds.), Made to be seen: Perspectives on the history of visual anthropology.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Roelandt, E. (2008). Renzo Martens’ Episode 3: Analysis of a film process in threeconversations. A Prior, 16, 176–185. Retrieved from http://www.deburen.eu/uploads/documents/Renzo%20Martens%20-%20A%20Prior.pdf/.

Ruby, J. (2000). Picturing culture: Explorations of film and anthropology. Chicago, IL:University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, T. D. (2012). Virality: Contagion theory in the age of networks. Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press.

Shome, R. (1996). Race and popular cinema: Rhetorical strategies of Whiteness in City of Joy.Communication Quarterly, 44(4), 502–518. doi: 10.1080/01463379609370035.

Sontag, S. (1977). On photography. New York, NY: Macmillan.Spence, L., & Navarro, V. (2010). Crafting truth: Documentary form and meaning. Piscataway,

NJ: Rutgers University Press.Twigg, R. (2008). The performative dimensions of surveillance; Jacob Riis’ “How the other half

lives.” In L. C. Olson, C. A. Finnegan, & D. S. Hope (Eds.), Visual rhetoric: A reader incommunication and American culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ukadike, F. (2009). Critical dialogues: Transcultural modernities and modes of narratingAfrica in documentary films. In S. H. Bekers & D. Merolla (Eds.), Transculturalmodernities: Narrating Africa in Europe. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Rodopi.

Unknown Author. (2010, September 10). Film “Enjoy Poverty” from Dutch artist RenzoMartens. Afro-Europe, International Blog. Retrieved from http://afroeurope.blogspot.com/2010/09/film-enjoy-poverty-from-dutch-artist.html/

Yaco8. (2010, November 5). Enjoy poverty. Foreign Policy Blogs. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20110824101428/http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2009/05/11/enjoy-poverty/

Communication, Culture & Critique (2015) © 2015 International Communication Association 19