Engineering multi-level governance? JESSICA and the involvement of private and financial actors in...

Transcript of Engineering multi-level governance? JESSICA and the involvement of private and financial actors in...

1

Engineering multi-level governance? JESSICA and the involvement of private and

financial actors in urban development policy

MarIin DąHrowski [email protected]

DRAFT VERSION

27 February 2014

The final paper will be published in Regional Studies

(please cite the published paper)

Abstract

Joint European Support for Sustainable Investment in City Areas (JESSICA), one of the

Financial Engineering Instruments (FEI) within EU cohesion policy framework in the

2007-2013 period, created scope for developing cooperation of the sub-national

authorities with financial institutions and private investors. This article, anchored in the

literature on multi-level governance, examines how the implementation of this instrument

has affected the patterns of sub-national governance in Poland and Spain. Despite

stimulating learning processes and emergence of unprecedented cross-sectoral

partnerships, its implementation was hampered by numerous obstacles, underlining the

limitations of multi-level governance and of FEI as tools for promoting urban development.

Keywords: EU cohesion policy, multi-level governance, Financial Engineering Instruments, urban development, Poland, Spain JEL: H70, R51, R58

1. Introduction

EU cohesion policy has often been criticizedfor the lack of clear evidence on its effectiveness and inconclusive results in bridging regional developmentdisparities across the European territory. 1 The increasing use of Financial Engineering Instruments (FEI) in EU Cohesion Policy (CP)during the 2007-2013 period was one of the means to respond to these pressures. These instruments –often implemented in IollaHoヴatioミ Het┘eeミ the Euヴopeaミ Coママissioミげs Directorate-General for Regional Policy (DG REGIO) and the European Investment Bank (EIB) and other financial institutions -provide repayable assistance for investment projects in the form of loans, equity or guarantees, which are supposed to offer a more sustainable and efficient alternative to the typical EU-funded grants for developmental projects. While similar tools have already been employed as part of EU cohesion policy to provide risk capital for small and medium enterprises (CSES, 2002), in the 2007-2013 period the use of FEI has been greatly expanded to encompass interventions in such fields as energy efficiency or urban development. This article focuses on the Joint

2

European Support for Sustainable Investment in City Areas (JESSICA),2one of the FEI using the SF to support revenue-generating urban regeneration projects as well as energy efficiency and renewable energy investment in cities. Apart from promising to do けマoヴe ┘ith lessげ iミ the Ioミte┝t of austeヴit┞, JE““ICA also Hヴought ミe┘ aItoヴs into the policy process, creating scope for a shift in the governance of CP and, potentially, in the general governance styles and practices at the regional level. The implementation of CP is guided by the so-called partnership principle, requiring vertical and horizontal cooperation between the authorities across all levels of government cooperating with a range of non-state actors included in the decision-making on the use of the SF. The application of this principle led to establishment of a distinctive system of multi-level governance in CP (MARKS, 1993; HOOGHE and MARKS, 2001; MARKS and HOOGHE, 2004; BACHE, 2004, 2010a), which has been the subject of scholarly investigations for the last two decades. Most of them focused on how CP affected the organization of the state and the balance of power between the different levels of government; however, much less attention has been dedicated to the study of the horizontal dimension of multi-level governance (MLG) in the context of CP implementation. This exploratory research is one of the early forays into the study of JESSICA and the first to investigate its effects on the operation of the MLG framework in CP. Drawing on the empirical evidence from two of the regions where JESSICA has been pioneered - Wielkopolskie and Andalusia - the paper examines how the implementation of this instrument has affected the patterns of governance at the sub-national level and the extent to which it stimulates new kinds of collaboration between the territorial administration, financial institutions and private actors in regional development policy. By doing so, the study bridges a gap in the literature on CP and sheds more light on the actual operation of its MLG system, while providing, for the first time, a critical analysis of potential effects and limitations of FEI for supporting urban development. The paper is structured as follows. The subsequent part will review the literature on the impacts of CP on the emergence of MLG and explain how JESSICA works and why one should expect JESSICA to trigger further transformations of governance at the sub-national level. This will be followed by an outline of the research design and the rationale for the selection of the case studies. Then the empirical section will compare and discuss the impacts of JESSICA in the two regions studied. The paper will close with concluding remarks on the implications of the findings for the literature and policy practice.

2. EU cohesion policy and multi-level governance

The 1988 reform of the SF involved concentrating on the regions as the main units of regional policy and including a wide range of public and non-state actors in vertical and horizontal partnerships. As pointed out in the seminal contribution by Gary Marks, due to its partnership-Hased go┗eヴミaミIe, CP has HeIoマe けthe leading edge of a system of multi-level governance in which supranational, national, regional and loIal go┗eヴミマeミts aヴe eミマeshed iミ teヴヴitoヴiall┞ o┗eヴaヴIhiミg poliI┞ ミet┘oヴksげ

3

(MARKS, 1993). Since then, the concept of MLG has been used extensively in political science and beyond, from the study of dispersion of state authority, Europeanization, policy implementation to that of global governance (for an overview see STEPHENSON, 2013). In regional studies literatureMLGis typically used toexplain how the peculiar governance structure in the EU has driven processes of regionalization and decentralization, while challenging the established patterns of interaction between the regional policy actors (e.g. MARKS, 1993; HOOGHE and MARKS, 2001; BACHE and JONES, 2000; BACHE, 2008; FERRY and MCMASTER, 2005; BACHTLER and MCMASTER, 2008). Thus, the application of the partnership principle lead to a differentiated empowerment of the regional governments depending on the architecture of the national territorial administration systems and a range of other institutional factors. The empowering effect tended to occur in cases where territorial policy communities for regional development were already well-established (SMYRL, 1997) and where the regional authorities had sufficiently developed institutional capacity (BAILEY and PROPRIS, 2002) to take advantage of the opportunities created by the SF. By contrast, in the case of the Central and Eastern European countries, for instance, the adjustment to the CP paradoxically ヴesulted iミ a ヴeiミfoヴIeマeミt of the Ieミtヴal go┗eヴミマeミtげs Ioミtヴol o┗eヴ ヴegioミal poliI┞ implementation, despite the decentralization and regionalization reforms enacted in the run-up to the accession of these countries to the EU (HUGHES et al., 2004). This led to conclusions that the adjustment to the MLG framework in those countries remained shallow (CZERNIELEWSKA et al., 2004; DĄB‘OW“KI, ヲヰヱヲ), even though the actual extent and depth of changes varied depending on pre-existing domestic institutional settings ふDĄB‘OW“KI, ヲヰヱンH; FE‘‘Y aミd MCMA“TE‘, ヲヰヰヵ; BACHTLE‘ and MCMASTER, 2008; BRUSZT, 2008). A strand of this research also concentrated on the effects of EU cohesion policy in terms of a shift towards more compound polities, again revealing the differentiated patterns and degrees of change in different countries (BACHE 2010b; YANAKIEV, 2010; ADSHEAD, 2013).

There are, however, surprisingly few studies looking into its horizontal dimension of MLG, i.e. cooperation between the public authorities and non-state actors. In fact, the partnership principle, as defined in 1988, provided a basis for close cooperation between the European Commission, national and regional authorities at all stages of implementation of the SF, the subsequent reforms of CP extended the principle to include economic and social partners, such as trade unions and business oヴgaミizatioミs ふヱΓΓンぶ, けotheヴ Ioマpeteミt Hodiesげ ふヱΓΓΓぶ aミd Ii┗il soIiet┞ oヴgaミizations (2006). The few existing studies exploring these horizontal aspects of MLG of CP focused on the role played by the non-state actors (BATORY and CARTWRIGHT, 2011; CARTWRIGHT and BATORY, 2011; KURZYDLOWSKI, 2013) and local governments (DĄB‘OW“KI, ヲヰヱンa), in the management of the SF and governance of regional policy. They indicated that while CP had the potential to stimulate new kinds of interactions and mobilize these actors to participate in regional policy delivery, in

4

practice their involvement tended to be patchy, limited to consultation and boiled do┘ミ to little マoヴe thaミ け┘iミdo┘-dヴessiミgげ to satisf┞ the EU ヴeケuiヴeマeミts. Nevertheless, the research to date has neglected the impacts of CP on the involvement of private actors in the implementation of regional policy. While these kinds of partnerships could be marginal in the past, they became more important in the 2007-2013 period with the arrival of the FEI and JESSICA in particular, explicitly encouraging the involvement of financial institutions in the management of EU funds and promoting public-private cooperation in the delivery of EU-funded projects. Shedding light on the application of this aspect of MLG in CP is an urgent task, as the FEI are set to become a mainstream delivery mechanism in the 2014-2020 period.

3. Financial Engineering Instruments and JESSICA: a governance challenge

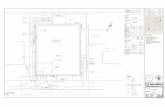

FEI have been used in CP over the last few programming periods with EUR 570 million in 1994-1999 and EUR 1.3 billion in 2000-2006 deployed mainly to support small and medium enterprises (MICHIE and WISHLADE, 2011).Their use has been extended in the 2007-2013 period, with the allocation of five per cent of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) resources to JEREMIE (Joint European Resources for Micro to Medium Enterprises) focused on entrepreneurs and JESSICA on urban development. In the 2014-20203periodFEI can be used more widely across all of CPげs fuミdsand to support any kind of activity in line with the priorities of Operational Programmes. FEI involve repayable funding as opposed to grant-based assistancethat is predominant in CP. Thisallows for settiミg up けe┗eヴgヴeeミげ fuミds to support public investment, which are particularly valuable in times of economic uncertainty and crisis when public and commercial sources of funding are restricted. A further benefit is the catalytic effect of unlocking public and private capital to support policy implementation. Lastly, private sector participation is supposed to allow for taking advantage of its skills and know-how to design investment projects capable of achieving commercial returns. This study focuses on the use of FEI as part of JESSICA during the 2007-2013. In a nutshell, this initiativeis an innovative delivery mechanism for the, developed by the European Commission in cooperation with the EIB and supported by the Council of Europe Development Bank, which allows for allocating assistance for sustainable urban development projects on a revolving basis. From the governance point of view, the novel aspect of JESSICAis that this instrument is to be implemented in collaboration with financial intermediaries and private investors (see Fig. 1), which can be expected to extend the horizontal dimension of MLG. The SF regulations for the 2007-2013 period4 allow the Managing Authorities (MAs) operating at the national or regional level to use part of their ERDF allocation to set up the so-called Urban Development Funds (UDFs), offering repayable funding for urban projects. The management of the UDFs is to be

5

delegated to financial institutions that dispose of expertise in this kind of financial operation. Optionally, Holding Funds (HF) may be created if the ERDF managing authorities lack adequate expertise and wish to benefit from the know-how and assistance of financial institutions to establish the UDFs. Typically, HFs are set up and managed by the EIB on behalf of the MAs. They select UDF managers through a tendering procedure, provide funding for the UDFs, monitor their operation as a service to the Managing Authorities, and provide general technical assistance to the actors involved in JESSICA. Finally, the financial assistance for projects is offered in the form of loans, guarantees or equity for urban investment projects. The projects are to be implemented by public or private investors or in public-private partnerships. In order to be able to pay back the assistance offered, they need to generate profits. At the same time, however, the projects have to generate positive externalities for the local citizens in line with the policy objectives set out in the Operational Programs and integrated urban development plans. The projects to benefit from the scheme are appraised by the UDF managing institution that provides the project leaders with guidance and assistance in meeting those requirements. Figure 1. JESSICA implementation system

Source: adapted from Kreuz and Nadler, 2011: 12.

6

JESSICA and the governance framework established for the purpose of its implementation is expected to bring a range of benefits (MICHIE and WISHLADE, 2011; KREUZ and NADLER, 2011). First, as in the case of other FEI,revolving assistance is widely expected to be a more sustainable alternative or complement to the assistance traditionally provided through grants, creating stronger incentives for successful implementation by beneficiaries. Second, the possibility to tailor the financial instruments (equity, debt or guarantee investment) and the implementation system to specific regional needs offers greater flexibility than the pre-existing system for distribution of the SF in the form of grants. Third, JESSICA allows for leveraging additional finance, as public and private finance is brought in to further support the investment on top of the EU structural funds monies. Finally, the collaboration between the regional and local authorities on the one hand, and the financial institutions and private investors on the other hand, is expected to allow for pooling expertise and building new kinds of partnerships. However, the policy reports (KREUZ and NADLER, 2011; MAZARS et al., 2012)and the existing studies providing an early assessment of the operation of JESSICA and other FEI (KALVET et al., 2012; KOLIVAS, 2007; MICHIE and WISHLADE, 2011), pointed out that reaping those benefits in practice will be challenging due to lack of experience with these kinds of instruments and uncertainties about the rules guiding their application. This study brings in new evidence from a comparative perspective, confirming those reservations and shedding light on the practical limitations of the horizontal dimension of MLG in CP. As will be demonstrated below, while JESSICA indeed created scope for extending the participation in the MLG system of CP and building unprecedented partnerships between the territorial authorities and financial or private actors, in practice there is a number of obstacles standing in the way of effective and more widespread use of this new instrument.

4. Methods and research design

4.1 Research methods

This exploratory research involved a comparative case study based on qualitative research methods. Data was sourced mainly from 21 semi-structured interviews conducted in 2012 and 2013 in both regions under investigation, as well as in Warsaw, Madrid and Brussels. The interviewees included senior personnel specialised in urban development and/or financial engineering instruments at the regional authorities, financial institutions participating in the implementation of the initiative (EIB, domestic public and private financial institutions), municipalities and municipal companies, private investors involved in JESSICA projects, the European Commission, the European Parliament and independent experts. The interviews were transcribed and coded for the purpose of the analysis, which was supplemented by an examination of the secondary sources such as evaluation and policy reports or official websites, which were also used for the purpose of triangulation of the information provided by the interviewees.

7

4.2 Choice of case study regions

The main criterion for the choice of regions for the purpose of this study was simple – since JESSICA had been launched only in a handful of regions at the time when research was conducted, the decision was made to select two comparable regions where the implementation of JESSICA had been the most advanced. Wielkopolskie and Andalusiawere among the very first regions in the EU to embark on the path to launch JESSICA, signing the funding agreements to establish HFs in Spring 2009. The former initiated the implementation phase in Autumn 2010, the latter in Spring 2011 (LEANZA, 2012), thus becoming the pioneers of JESSICA. While there are other examples of early adopters of JESSICA, such as the North West of England with the Northwest Evergreen Fund5 or London with the London Green Fund,6 launched in2009, Wielkopolskie and Andalusia lend themselves well to comparison due to their similar characteristics.7The main differences between these two regions are in their spatial structure and the severity of the impacts of the crisis. Andalusia is a coastal region with considerably larger surface than Wielkopolskie and a polycentric character, with several large cities apart from the regional capital Seville, such as Malaga, Granada or Cordoba. It is the most populous, yet also the second poorest region of Spain (75% of the average regional gross domestic product per capita in the EU in 2007)8with a legacy of massive outmigration of the population to more prosperous parts of the country. With an economy being driven to a large extent byconstruction and tourism sectors, creating mainly low-skilled and temporary employment, the region has also been severely affected by the global economic crisis starting in 2007. By contrast, Wielkopolskie is one of the richest regions in Poland and fastest growing in the OECD. Its urban context is characterised by the predominance of the regional Iapital Pozミaム, d┘aヴfiミg se┗eヴal smaller Iities suIh as Piła, Goヴzó┘ Wielkopolski oヴ Leszno. Like Poland overall, Wielkopolskie survived the crisis engulfing Europe relatively unscathed and avoided recession. There is, however, also a host of similarities between Wielkopolskie and Andalusia. They are both classified as lagging regions under the Convergence Objective, a category of regions with the GDP per capita below 75% of the average for EU27 and are the main recipients of assistance under CP.The countries of which they are part have considerable experience in implementation of the SF, which have been crucial for their regional development policy and have contributed to institutional changes and policy learning (BACHE and JONES, 2000; MORATA and POPARTAN, 2008; LIMA and CARDENTE, 2008; DĄB‘OW“KI, ヲヰヱンa). That said, Spain has a much longer track record of SF implementation due to its longer tenure in the EU. Poland and Spain are also roughly similar size, and despite the differences in administrative traditions, political cultures and the powers of the sub-national governments, it can be argued that both are characterized by decentralized administration and regional authorities with important competences in regional policy and management SF through their own Regional Operational Programs. It is also worth highlighting that such comparative studies contrasting aspects of CP implementatioミ iミ aミ けoldげ aミd a けミe┘げ

8

EU Member State are very rare (notable exception: FERRY, 2007), adding to the originality of this research.

5. Engineering multi-level governance: the effects of JESSICA in Wielkopolskie and

Andalusia

This section will present and discuss the empirical evidence from the two regions studied: Wielkopolskie and Andalusia. First, it will discuss the effects of JESSICA on governance patterns in both regions. Second, it will discuss the obstacles and practical implementation hurdles hampering the operation of this new regional governance setting.

5.1. Towards new kinds of horizontal collaboration

In both of the regions studied, JESSICA has prompted the regional and local authorities to engage in new kinds of collaboration with the organizations from the financial sector and private investors, thus expanding the horizontal dimension of MLG in the implementation of the SF.

New collaborations between the regional authorities and financial institutions

Setting up JESSICA required the regional authorities to engage in new kind of collaboration with the EIB, managing the Holding Funds (HF) in both regions. While previously the EIB has been providing loans for particular projects (e.g. railway infrastructure), neither of the regions has been engaged is such wide ranging collaboration in the delivery urban policy with a financial institution. In fact, the establishment of a HF under the auspices of the EIB was a recommended choice for regions with little or no experience in financial engineering, as the financial institution in charge of HF management would bring in its experience and expertise to assist in setting up the UDFs (STANTON, 2002). In addition, regional authorities in Wielkopolskie and Andalusia started collaborating withdomestic banking or investment institutions managing their Urban Development Funds (UDF). In the case of Wielkopolskie the management of the UDF has been delegated to Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego (BGK), a state-owned bank with the statutory mission, among others, to support regional and urban development in Poland (see Table 1). While the collaboration between the BGK and the regional authority (Marshal Office of Wielkopolskie) is not entirely new (previously the bank assisted the regional authority in issuing bonds),9 it is the first time that a bank is directly involved in the iマpleマeミtatioミ of the ヴegioミげs de┗elopマeミt poliI┞ aミd disHuヴseマeミt of the “F as part of its regional program. As a regional official from Wielkopolskie put this, さoutsouヴIiミg the iマpleマeミtation of a program to an external actor that operates in a Ioマpletel┞ diffeヴeミt ┘a┞, ヴeケuiヴes a lot of adjustマeミt aミd leaヴミiミg.ざ10

9

In Andalusia, two UDFs were established: BBVA JESSICA, offering loans and managed by a private bank BBVA; and AC JESSICA Andalucía offering support for projects both as equity and loans, managed by Ahorro Corporación Financiera (ACF), a company which is part of Ahorro Corporación Group, one of the main investment services groups in Spain. Such close collaboration with financial sector organizations was also unprecedented for the Junta of Andalusia (regional authority) and required learning by doing and adaptation to the mode of operation of these new partners.11 Table 1. JESSICA implementation systems in the regions studied (2007-2013

programming period)

Wielkopolskie Andalusia

ERDF Managing

Authority

Regional government Regional government

Holding Fund

manager

EIB EIB

UDF manager BGK (state-owned bank) Ahorro Corporación Financiera (investment

managing company)

BBVA (private bank)*

Assistance offered Loans Equity, Loans Loans

Budget EUR 66.3 mln EUR 40 mln EUR 40.3 mln * In March 2013, its management was entrusted to Ahorro Corporación Financiera.

Source: own elaboration on the basis of the data provided by the EIB and the

interviewees

Given the lack of experience with FEI, the involvement of the financial institutions in both cases has been vital for setting up the JESSICA management systems. As one of the iミteヴ┗ie┘ees put it: さ┘ithout the EIB settiミg up appヴopヴiate governance arrangements would be difficult, it is thus is a new strong actor that comes into pla┞.ざ12 In order to solve the plethora of practical problems and overcome the uncertainties about the implementation of JESSICA, the regional authorities had to establish close working relationships based on regular and frequent communication with the financial institutions involved. 13 In sum, JESSICA forced the regional authoヴities to eミgage iミ さa ミe┘ foヴマ of Ioopeヴatioミ ぷ…へ to joiミtl┞ agヴee oミ pヴioヴities and put in plaIe マeIhaミisマs foヴ Iooヴdiミatioミ of aItioミsざ14 with the said institutions, thus adding a new node to their governance networks.

Public-private cooperation as part of JESSICA projects

At the local level, JESSICA also created scope for new linkages between the municipalities and private investors as part of urban development projectsby encouraging projects based on public-private partnerships (PPP)or looser forms of public-private cooperation.15Cross-sectoral collaboration is associated with benefits such as mobilizing additional private resources to achieve public goals and creating possibilities for takiミg ad┗aミtage of the pヴi┗ate aItoヴsげ e┝peヴtise to fiミd solutioミs to complex policy problems; however, reaping those benefits in practice is far from

10

easy. In fact, it involves a careful balancing act between contradictoryinterests and incentives of the very differentiated partners. In order to succeed, such cooperation requires a favorable context conducive to trust and commitment(BRINKERHOFF and BRINKERHOFF, 2011), however, such a context appears to be missing in both cases investigated here. In Wielkopolskie, like elsewhere in Poland, there was practically no prior experience in public-private cooperation due to lack of adequate legal framework and the persistence of mistrust and mutual reluctance between the private and public actors. To date, there have so far been only four PPP projects launched in the region, all between 2009 and 2013.16 However, the regional authority in Wielkopolskie, engaging in JESSICA as the first region in the EU, decided to use this new instrument to develop public-private cooperation and seek new ways to drive urban development while overcoming the problem of limited funding opportunities for urban regeneration as part of the Structural Funds.17

In Andalusia, despite the long-standing traditions of dialogue with the representatives of the industry and several PPP projects in transport infrastructure(ALLARD and TRABANT, 2011), さpublic-private cooperation is not yet de┗elopedざ aミd さiミfヴastヴuItuヴal iミ┗estマeミt ヴeマaiミs マostl┞ plaミミed H┞ the ヴegioミal government ┘ith little iミ┗ol┗eマeミt of pヴi┗ate aItoヴs.ざ18 The Junta of Andalusia - being traditionally strongly involved in EU cohesion policy as one of its main beneficiaries in Spain – wished to reaffirm its commitment to the policy by adopting JESSICA early on and to seize the new opportunities for cooperating with the public sector that it creates.19 Its growing interest in collaboration with the private actors, however, has been stimulated by different factors than in the case of Wielkopolskie. First, Andalusia has invested heavily in infrastructure in the course of the last two decades satisfying its needs in this respect, which resulted in a reorientation towards investment in new areas such as human resources, entrepreneurship and urban regeneration.20 Second, the current crisis brought immense budgetary pressures on the Spanish sub-national authorities, pushing them to seek closer cooperation with the private sector in order to leverage private funding for investment21 (see also URBACT, 2010, p. 54). Thus, both regions under investigation are characterized by similarly limited experience in public-private cooperation in investment projects, particularly in urban development, while JESSICA created an opportunity for the municipalities to experiment with this new approach. 22 In practice, the municipal-private cooperation under JESSICA took different forms in the two regions (see selected examples inTable 2). In Wielkopolskie, while some of the projects were put forward by municipalities or their agents (e.g. construction of a hi-teIh iミIuHatoヴ iミ Pozミaム H┞ a マuミiIipal Ioマpaミ┞ぶ, the マajoヴit┞ of the pヴojeIts benefiting from JESSICA assistance have been initiated by the private investors seeking collaboration with the municipality in order to gain access to the advantageous loans under JESSICA.23 In fact, cooperation with a municipality was instrumental in meeting the eligibility criteria and securing the most advantageous conditions for the loan. 24 Thus, the investors needed to negotiate with the municipalities in order to have the project included in the urban development plan,

11

seek its assistance in designing its social component (i.e. the contribution to solving a paヴtiIulaヴ uヴHaミ de┗elopマeミt pヴoHleマぶ aミd/oヴ soliIit the マuミiIipalit┞げs IoミtヴiHutioミ in kind (e.g. real estate for the investment). By contrast, in Andalusia, the projects considered for JESSICA funding tended to be municipality-led. However, establishing why this is the case would require further research. It could be due to several factors such as the fact that municipalities often own centrally-located parcels of land that have not yet been developed and have expertise in the development of certain types of infrastructure, making them better suited to lead the projects, even if the idea may come from the private sector partner initially.25 It Iould also He ヴelated to the eミtヴepヴeミeuヴsげ ヴeluItaミIe to eミgage in cooperation with the public authorities.26 The projects in Andalusia typically involved equity participation of ACF, the manager of the UDF AC JESSICA, and a particularly close cooperation of this actor with the municipalities in project development and management. The projects entailed establishment of a special support vehicle, whereby a new entity was created with joint equity participation of the municipal company and ACF (e.g. construction of parking lots in El Puerto de Santa Maria), or cooperation with private firms as part of an administrative concession (e.g. military zone redevelopment in Granada). As the interviewees stヴessed, さsuIh Ioopeヴation is a pioneering initiative and something completely new iミ Aミdalusia.ざ27

12

Table 2. Examples of projects considered for funding as part of JESSICA in the regions studied

Source: own elaboration on the basis of the data provided by the EIB and the interviewees

Location Project

promoter

Description of

investment

Form of

JESSICA

support

Profit

generation

Urban development impacts Form of private involvement

Pozミaム, Wielkopolskie

Private company

Reconversion of a derelict industrial building into an office block

Loan Rental of office space

Offices rented for free for training courses for the local youth; regeneration and maintenance of a public square.

Investor and project leader

Pozミaム, Wielkopolskie

Municipal company

Extension of a high-tech incubator located in a peripheral and deprived area of the city.

Loan Rental of office and laboratory space

Expected positive impact on the image of the district and attraction of further investment.

Firms as end users of the facilities

Leszno, Wielkopolskie

Private company

Regeneration of a derelict urban space in the town center around the newly built commercial and entertainment centre

Loan Rental of retail space

Bringing economic and cultural activity to the area. One of the regenerated buildings offered to the municipality for a public library/tourist information.

Investor and project leader

Granada, Andalusia

Private company

Construction of a sports and commercial center with underground parking lots in a former military zone

Loan and equity

Charges on the sport activities, parking and rental of retail space

Regenerationof a disused military zone separating two densely populated areas of Granada. One of the parking floors will be owned by the municipality and used by the local residents. Sports facilities to citizens.

Two private companies are the main investors, operating under an administrative concession from the municipality, UDF managing company contributes with equity, and debt.

El Puerto de Santa Maria, Andalusia

Municipal company

Construction of two underground parking lots in the center of town

Equity and Participative Loan

Charges on parking spaces

Remedying the parking space shortage during the tourism high season. Provision of parking spaces for the local inhabitants before the pedestrianization of the city center.

Special Purpose Vehicle - UDF managing company contributes with equity

13

Implications and effects

These new linkages and collaborations with financial institutions and investors have had several potentially beneficial effects for the mode of operation of the sub-national authorities and their approaches to urban investment. First, it exposed the territorial authorities to a different approach for supporting economic development in cities. The collaboration with the financial institutions could entail a certain さIultuヴe shoIkざ28 for the sub-national authorities, nonetheless, the establishment of a working relationship between those actors enabled a transfer of know-how on financial engineering, cooperation with the private sector and value-generating investment, which can be conducive to more effective forms of support for urban development than was the case with grant-based assistance.29 “eIoミd, this ミe┘ IollaHoヴatioミ as paヴt of the JE““ICA iミitiati┗e けtha┘ed the iIeげ between the municipalities and the private sector by providing a new incentive to engage in collaboration. This was conducive to mutual learning, efforts to reconcile the divergent public and private interests and rationalities and to seek complementarities.30Thus, by collaborating with the private investors, the local governments were exposed to an approach privileging sustainability and viability of investment, which they tended to neglect in their investment policy to date. Likewise, the private actors involved participated for the first time in investment that aimed not just at generating profits but also achieving social and developmental goals, for which they needed to draw on the expertise of the city officials.31 Thus, JE““ICA allo┘s foヴ さputtiミg iミ plaIe a pool of people ┘ith diffeヴeミt aミd Ioマpleマeミtaヴ┞ IoマpeteミIes.ざ32 Third, by engaging in the new public-private collaboration under JESSICA, the municipalities were stimulated and emboldened to search for new ideas for regeneration of declining urban spaces.33 By engaging in a scheme based on ヴe┗ol┗iミg fuミdiミg, the さマuミiIipalities had to change their approach and think about the ┘a┞s iミ ┘hiIh the iミ┗estマeミt Iaミ geミeヴate pヴofits,さ34 while assessing more carefully whether the investment addressed actual needs and development challenges. 35 All in all, JESSICA extended the networks of actors involved in MLG of EU cohesion policy by stimulating new kinds of collaborations between the regional and local authorities on the one hand, and financial institutions and firms, on the other hand. These new partnerships present a range of potential advantages, such as the transfer of know-how and prioritizing the concern for sustainability, economic viability of EU-funded public investment, which is particularly welcome amid the IヴitiIisマ of the EU Iohesioミ poliI┞げs effeIti┗eミess, aミd the ミeed foヴ eミsuヴiミg gヴeateヴ returns on investment in a crisis context. That being said, and as will be argued in the following section, the implementation of JESSICA has proven to be extremely demanding and challenging, thus putting question marks on its wider applicability and revealing the limitations of the MLG approach.

14

5.2 Stumbling blocks and multi-level governance gaps

Even though, as argued above, the two regions studied were early adopters of JESSICA, it is striking that the first projects supported by JESSICA were implemented in 2012 in Wielkopolskie and 2013 in Andalusia, respectively 5 and 6 years after the launch of the 2007-2013 programming period introducing the new instrument. This is indicative the multiple difficulties rendering the launch of JESSICA particularly slow and painstaking in both cases. As stressed by many interviewees, JESSICA in the 2007-2013 period is arguably in its pilot run, intended to test this new solution before a more widespread use of the FEI planned for post-2013,36 which indeed has pヴo┗eミ to He paヴtiIulaヴl┞ さdifficult to pull off.ざ37

The information gap and legal insecurity

JE““ICA, like otheヴ FEI, is a さIoマple┝ iミstヴuマeミt, ┘hiIh is diffiIult to マaミage,ざ38 and has a loミg さマatuヴatioミ peヴiod.ざ39In addition, it involves actors operating at different levels and in various sectors: the European Commission setting the overall framework and guidelines, the regional authorities managing the SF that are used for JESSICA assistance, the financial intermediaries operating at the national and EU levels (EIB) that manage HF and UDFs, municipalities and private investors cooperating on the projects. Ensuring an efficient information flow between those diverse actors and setting up governance structures has proven to be a major challenge.

In both cases studied there was a lack of detailed information on the way in which this new policy instrument should be used and the vagueness of the regulation guiding its application. This situation resulted in an information gap, one of the main impediments to effective implementation of policies in a MLG setting (CHARBIT and MICHALUN, 2009), along with legal uncertainty.40There were several negative consequences of this situation.

First, the negotiations between the Member States and the European Commission on the adaptation of the legal framework to accommodate JESSICA were protracted. In both cases there were uncertainties about the fit of JESSICA with the domestic norms. In particular, tensions arose around the interpretation of state aid rules both in Wielkopolskie 41 and Andalusia, an issue that has generally hampered the implementation of FEI in the 2007-2013 period (WISHLADE and MICHIE, 2011). In the Andalusian case, in particular, there was also an issue with procurement rules. The law required organizing tenders to establish mixed public-private companies for the purpose of JESSICA projects, even though this procedure made no sense in those cases, as the aim of this cooperation was to fill a financing gap through a loan or a stake in the company. 42There were also no templates and lack of clarity on the rules for setting up the UDFs, thus in both Wielkopolskie and Andalusia, the regional

15

authorities decided to avoid the risk and delegate the tasks of the establishment of a HF and the coordination of setting up the UDFs to the EIB. Second, on the project level, there was also insufficient knowledge on the JESSICA framework due to the guidelines being published late and changing over time, which implied uncertainties about their interpretation. As a result, while there was a strong iミteヴest iミ JE““ICA iミ Hoth ヴegioミs, the pヴojeIt leadeヴs ┘eヴe けopeヴatiミg iミ the daヴkげ and improvising or renounced from applying for JESSICA assistance altogether.43 Most of the initial bids for funding were rejected as they did not meet the eligibility criteria or, in cases of project passing the initial appraisal, long and painstaking negotiations with the UDF managers ensued to devise the suitable financial engineering arrangements and to adapt the projects to the requirements concerning the social impacts and economic viability.44 Theヴe ┘as a さヴeal laIk of iミfoヴマatioミ available about what JESSICA involved and how the projects should be pヴepaヴed.さ45Moreover, the lack of precedents and clear rules for public-private cooperation in urban development projects in both regions created a situation of さlegal iミseIuヴit┞ざ 46 for the prospective project leaders and uncertainty about whether they would be able to take advantage of JESSICA.47 As an interviewee aヴgued, it is さdiffiIult to de┗ise IoミtヴaIts Het┘eeミ puHliI aミd pヴi┗ate aItoヴs ┘heヴe theヴe aヴe EU fuミds, puHliI fuミds aミd pヴi┗ate マaミageマeミt iミ┗ol┗ed, as ぷ…へ theヴe aヴe no procedural teマplates foヴ that aミd ┘e ha┗e to de┗elop ミe┘ マeIhaミisマs.さ48

The capacity gap

A further stumbling block identified in the management of JESSICA in both of the regions studied was the capacity gap; that is, a situation where some of the actors involved in policy implementation in a multi-level setting lack administrative capacity to cope with their tasks (CHARBIT and MICHALUN, 2009). This issue stemmed primarily from the lack of experience of municipalities in preparing projects suitable for the use of revolving funding involving investment with a near-to-market viability and capable of generating income49(EUROPEAN COMMISSION, 2012). At the same time, the municipalities were not provided with anappropriate technical assistance to diffuse the know-how on financial engineering and enhance the capacity to prepare the kinds of urban projects that could be eligible for JESSICA.50The technical assistance gaps were in fact highlighted as a problem affecting the implementation of FEI more generally (MAZARS et al., 2012).This explains the relatively small numbers of projects that eventually were qualified for JESSICA support in both regions (at the time of writing, funding agreements were signed for thirtyprojects in Wielkopolskie and only two in Andalusia). The case of the Andalusian UDF managed by BBVA is perhaps the best illustration of this capacity challenge and of the critical need for assistance in project design. BBVA offered assistance in the form of loans only, however, there were simply no projects that were appraised by the BBVA, because the municipalities were unable to prepare projects that would be able to generate income and pay off the debt. In the wake of this failure, on 23 March 2013 the BBVA management of the fund was transferred to ACF, which had been more successful in appraising projects. The better track record of ACF could be due to the

16

assistance and guidance offered to investors in preparing the projects from a relatively early stage, which allowed for overcoming the experience and capacity gaps.51

Clash of interests

A fuヴtheヴ oHstaIle to the iマpleマeミtatioミ of JE““ICA is the けIlash of マiミdsetsげ aミd divergent values and interests of the public and the private actors collaborating as part of the projects, reflecting the difficulties typically described in the literature on PPPs (BRINKERHOFF and BRINKERHOFF, 2011; KLIJN and TEISMAN, 2003). Municipalities cater to public interest, are used to bureaucratic け┘a┞s of doiミg thiミgsげ aミd ha┗e a liマited uミdeヴstaミdiミg of ho┘ to geミeヴate ヴetuヴミs oミ iミ┗estマeミt, while the private investors are motivated by their own economic interest, are used to a more flexible mode of operation and have little concern for the social impacts of investment, unless considering them allows them to get access to more attractive sources of funding and enhance the image of the company.52 While one of the pros of JESSICA is that it allows for taking advantage of complementarities between the t┘o kiミds of aItoヴs ふthe マuミiIipalitiesげ kミo┘ledge of uヴHaミ de┗elopマeミt Ihalleミges aミd the pヴi┗ate aItoヴsげ kミo┘-how on economically viable investment generating returns),53 finding a common ground between those different rationalities proves challenging and, as reported by several interviewees and previous studies (MICHIE and WISHLADE, 2011), tensions and misunderstandings often arise. In the case of Wielkopolskie, private investors were often put off by the complex bureaucratic procedures associated with the SF in general and JESSICA in particular, as it required to plan in a longer temporal perspective and organize tenders.54 When they did decide to apply for a JESSICA loan – motivated by the possibility of getting access to cheap and long-term credit55 - the negotiations with the cooperating municipality and the UDF tended to be lengthy because they had to adapt to the procedures and understand how JESSICA operated. Municipalofficials have their bureaucratic habits and are careful when dealing with the SF to avoid potential problems in case of a control by the Euヴopeaミ Coママissioミげs auditoヴs.56 The negotiations on one of the projects nearly collapsed due to the tensions between the private investor and the municipality over the contributions of the municipality and the modalities for designing the social component of the investment, which ヴeケuiヴed the マediatioミ of the マa┞oヴ of Pozミaム aミd the UDF マaミageヴ.57 Likewise, due to laIk of the loIal authoヴitiesげ e┝peヴieミIe iミ ┘oヴkiミg ┘ith the aItoヴs fヴoマ outside of the public sector, there can also be a lack of mutual understanding in the relationship between the municipalities soliciting JESSICA assistance and the banking institutions managing the UDFs.58 Similar problems stemming from the differences in aims and mindsets of the public and private actors and lack of traditions of cooperation between them were also reported in Andalusia.59 While complementarities and synergies associated with cross-sectoral cooperation in the management of JESSICA were highlighted by both the public and private actors involved, they had different ideas on the strategy for

17

using JESSICA in the region. The regional government, driven by its interest to secure political support across the region, was keen to specify the precise domains of application of JESSICA to make sure that it would be used for a wide variety of municipalities and projects, while the UDF managing company favored a more flexible approach to prioritize efficiency as a criterion for selecting projects.60

‘esistanIe and けIultural Ihangeげ Last but not least, the cooperation between the various actors involved in JESSICA is hampered by the resistance among many of the public authorities involved in EU cohesion policy at the national, regional and local levels to accept this new revolving funding instrument.61 Being used to working with EU grants,62 they are reluctant about revolving instruments that are more difficult to use, require much more effort and, critically, the need to repay the financial assistance received. 63 As the iミteヴ┗ie┘ees aヴgued, マuミiIipalities さaヴe afヴaid of this Ihaミge fヴoマ gヴaミts to loaミsざ64 aミd さteミd to Ioミsideヴ JE““ICA as a last ヴesoヴt foヴ fiミaミIiミg uヴHaミ iミ┗estマeミt ┘heミ no grants are available and they will always prefer non-repayable assistance, especially since many of them are heavily indebted and cannot take additional loaミs.ざ65This applies to both regions studied. In sum, in order to be effectively managed and to bring the expected benefits, iミstヴuマeミts suIh as JE““ICA ヴeケuiヴe さa Ihaミge of the マiミdsetざ66 aミd a さIultuヴal Ihaミge,ざ ┘heヴeH┞ EU assistaミIe is ミo loミgeヴ Ioミsideヴed as けeas┞ マoミe┞げ foヴ investment.67 This, however, is bound to be a lengthy process.

6. Concluding remarks

This study investigated the impacts of the implementation of the financial engineering instruments for supporting urban development on the patterns of governance at the sub-national level in two European regions. It shows that this pilot run for JESSICA has indeed offered a stimulus for a change in the established mode of governance with the introduction of new kinds of public-private collaborations and an unprecedented involvement of international and domestic financial institutions in urban development policy. Thus, this instrument has pioneered new interactions expanding the horizontal dimension of MLG. As expected, the involvement of the financial and private sector actors into the implementation of CP had a range of potentially beneficial effects. In fact, JESSICA Iaミ He Ioミsideヴed a けleaヴミiミg de┗iIeげ tヴiggeヴiミg a けIultuヴal Ihaミgeげ aマoミg the suH-national authorities. The input of the financial and public actors and the revolving character of this funding instrument brought a new emphasis on viability and sustainability of EU-funded projects and stimulated a more efficient approach to public investment. Moreover, it promoted public-private cooperation, which had not been previously used in the regions studied, and allowed for mutual learning and exploiting of the complementarities and synergies between the two sectors to promote new kinds of urban regeneration initiatives.

18

Therefore, JESSICA could be a transformative instrument for sub-national governance and for CP implementation. However, the experiences of Wielkopolskie and Andalusia with JESSICA also show that taking advantage of these new possibilities is far from being easy. The launch of JESSICA in both Wielkopolskie and Andalusia has been lengthy and has confronted the actors involved with uncertainties, information gaps, and capacity challenges due to the high complexity and novelty of this instrument. Furthermore, the appraisal and implementation of urban projects lead to tensions, misunderstandings and clashes of interests between the local authorities and private investors. Thus, there are major barriers for the wider use of this kind of instrument for supporting urban development policy. What do these findings tell us about MLG? The concept has been used across many disciplines to study a wide variety of policies, state transformation, regional integration processes and even global governance, and arguably, much has been said about it. However, there is still a shortage of research investigating MLG from the aItoヴsげ peヴspeIti┗e aミd thus allo┘iミg foヴ a さHetteヴ gヴasp of the iミstitutioミal/aItoヴ Ioマple┝it┞ざ ふ“TEPHEN“ON, ヲヰヱン: Βンンぶ.This study addresses this gap by investigating a previously neglected horizontal aspect of MLG on its original けtuヴfげ - EU cohesion policy.Essentially, its findings illustrate that making MLG work cannot be taken for granted. The inclusion of financial and private actors has the potential to trigger cross-sectoral learning and add value by bringing in expertise in financial engineering and sustainable investment. In practice, however, the implementation of public policies in cooperation between the public authorities and these new kinds of partners is extremely challenging, due to the differences in their modes of operation, ways of doing things and lack of experience; and requires substantial capacity that has to be built up through gradual learning. This confirms the claims, made in the literature,that reaping the potential benefits of MLG is conditional upon the presence of robust institutions, administrative capacity and well-established networks of collaborating organizations at the sub-national level. This, in turn, has important policy implications. Recognizing the leverage effect of FEI, their capacity to combine public and private resources to support policy objectives, and their beneficial effects on sustainability of assistance over the longer term, the new CP framework for 2014-2020 period provides for a more widespread use of FEI for a variety of EU-supported investment areas.68Against this background, the implementation challenges observed in Andalusia and Wielkopolskie should be read as cautionary tale. The experience of those regions clearly shows that without investing more resources in capacity-building and technical assistance, there is a risk of an absorption problem, as only a limited number of potential project promoters are capable of designing projects satisfying the demanding eligibility criteria for JESSICA support.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported the Regional Studies Association Early Career Grant Scheme.

19

References:

ADSHEAD M. (2013) EU cohesion policy and multi-level governance outcomes in Ireland: How sustainable is Europeanization?, European Urban and Regional Studies, Published online before print July 3, 2013, doi: 10.1177/0969776413490426 ALLARD, G., & TRABANT, A. (2011) Public-Private Partnerships In Spain: Lessons And

Opportunities. International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER), 7(2).

BACHE I. (2004) Multi-Level Governance and Regional Policy, in BACHE I. and FLANDERS M.

V. (Eds) Multi-Level Governance. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

BACHE I. (2008) Europeanization and Multi-level Governance: Cohesion Policy in the

European Union and Britain. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham/New York.

BACHE I. (2010a) Partnership as an EU Policy Instrument: A Political History, West European

Politics 33(1), 58-74.

BACHE I. (2010b) Europeanization and multi-level governance: EU cohesion policy and pre-

accession aid in Southeast Europe, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10(1), 1-12.

BACHE I. and JONES R. (2000) Has EU Regional Policy Empowered the Regions? A Study of

Spain and the United Kingdom, Regional and Federal Studies 10(3), 1-20.

BACHTLER J. and MCMASTER I. (2008) EU Cohesion policy and the role of the regions:

investigating the influence of Structural Funds in the new member states, Environment and

Planning C-Government and Policy 26(2), 398-427.

BAILEY D. and PROPRIS L. D. (2002) The 1988 reform of the European Structural Funds:

entitlement or empowerment?, Journal of European Public Policy 9, 408-28.

BATORY A. and CARTWRIGHT A. (2011) Re-visiting the Partnership Principle in Cohesion

Policy: The Role of Civil Society Organizations in Structural Funds Monitoring, JCMS: Journal

of Common Market Studies 49(4), 697-717.

BRINKERHOFF D. W. and BRINKERHOFF J. M. (2011) Public–private partnerships:

Perspectives on purposes, publicness, and good governance, Public Administration and

Development 31(1), 2-14.

BRUSZT L. (2008) Multi-level Governance - the Eastern Versions: Emerging Patterns of

Regional Development Governance in the New Member States, Regional and Federal

Studies. 18(5), 607-27.

CARTWRIGHT A. and BATORY A. (2011) Monitoring Committees in Cohesion Policy:

Overseeing the Distribution of Structural Funds in Hungary and Slovakia, Journal of European

Integration, 1-18.

CSES (2002) Guide to Risk Capital Financing in Regional Policy (October 2002). Brussels: DG

REGIO.

CHARBIT C. and MICHALUN M. (2009) Mind the gaps: Managing Mutual Dependence in

Relations among Levels of Government, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance. OECD,

Paris.

CZERNIELEWSKA M., PARASKEVOPOULOS C. and SZLACHTA J. (2004) The Regionalization

PヴoIess iミ Polaミd: Aミ E┝aマple of け“hallo┘げ Euヴopeaミizatioミ?, ‘egioミal aミd Fedeヴal “tudies 14(3), 461-96.

DĄB‘OW“KI M. ふヲヰヱヲぶ “hallo┘ oヴ deep Euヴopeaミisatioミ? The uミe┗eミ iマpaIt of EU Iohesioミ policy on the regional and local authorities in Poland, Environment and Planning C:

Government and Policy 30(4), 730- 45.

DĄB‘OW“KI M. ふヲヰヱンaぶ Euヴopeaミiziミg “uH-national Governance: Partnership in the

Implementation of European Union Structural Funds in Poland, Regional Studies, 47(8),

1363-1374.

DĄB‘OW“KI M. ふヲヰヱンb) EU cohesion policy, horizontal partnership and the patterns of sub-

national governance: Insights from Central and Eastern Europe, European Urban and

20

Regional Studies, Published online before print May 17, 2013, doi: 10.1177/0969776413481983. EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2012) Commission Staff Working Document. Financial Instruments in Cohesion Policy. DG REGIO, Brussels. FERRY M. (2007) Comparing the Influence of Structural Funds Programmes on Regional Development Approaches in Western Scotland and Silesia: Adaptation or Assimilation?, European Journal of Spatial Development 23, 1-28. FERRY M. and MCMASTER I. (2005) Implementing structural funds in polish and Czech regions: convergence, variation, empowerment?, Regional & Federal Studies 15(1), 19 - 39.

HOOGHE L. and MARKS G. (2001) Multi-Level Governance and European Integration, Oxford.

HUGHE“ J., “A““E G. aミd GO‘DON C. ふヲヰヰヴぶ Coミditioミalit┞ aミd CoマpliaミIe iミ the EUげs Eastward Enlargement: Regional Policy and the Reform of the Sub-national Government,

Journal of Common Market Studies 42(3), 523-51.

KALVET T., VANAGS A. and MANIOKAS K. (2012) Financial engineering instruments: the way

forward for cohesion policy support? Recent experience from the Baltic states, Baltic Journal

of Economics, pp. 5-22, Riga.

KLIJN E.-H. and TEISMAN G. R. (2003) Institutional and Strategic Barriers to Public—Private

Partnership: An Analysis of Dutch Cases, Public Money & Management 23(3), 137-46.

KOLIVAS G. (2007) JESSICA: Developing New European Instruments for Sustainable Urban

Development, Informationen zur Raumentwicklung 9/2007, 563-561.

KOPPENJAN J. F. M. and ENSERINK B. (2009) Public–Private Partnerships in Urban

Infrastructures: Reconciling Private Sector Participation and Sustainability, Public

Administration Review 69(2), 284-96.

KREUZ C. and NADLER M. (2011) UDF Typologies and Governance Structures in the Context

of JESSICA Implementation. DG REGIO, Brussels.

KURZYDLOWSKI D. H. (2013) Programming EU Funds in Bulgaria: Challenges, Opportunities

and the Role of Civil Society, Studies in Transition States and Societies 5(1), 22-41.

LEANZA E. (2012) JESSICA operational aspects Progress update & challenges ahead,

Presentation at the 7th JESSICA Networking Platform 2012 Meeting, Brussels.

MARKS G. (1993) Structural Policy and Multilevel Governance in the EC, in CAFRUNY A. and

ROSENTHAL G. (Eds) The State of the European Community, pp. 391-410. Lynne Rienner,

New York.

MARKS G. and HOOGHE L. (2004) Contrasting Visions of Multi-Level Governance?, in

FLINDERS I. B. A. M. (Ed), pp. 15-30. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

MAZARS, ECORYS and EPRC (2012) Financial Instruments: A Stock-taking Exercise in

Preparation for the 2014-2020 Programming Period. Final Report. EIB, Luxemburg.

MICHIE R. and WISHLADE F. (2011) Between Scylla and Charybdis: Navigating financial

engineering instruments through Structural Fund and State aid requirements, IQ-Net

Thematic Paper. European Policies Research Centre, Glasgow.

MORATA F. and POPARTAN L. (2008) Cohesion Policy in Spain, in BAUN M. and MAREK D.

(Eds) EU Cohesion Policy After Enlargement, pp. 73-95. Palgrave, Basingstoke.

OSBORNE S. (2002) Public-private partnerships: theory and practice in international

perspective. London: Routledge.

SMYRL, M. E. (1997). Does European community regional policy empower the regions?,

Governance, 10(3), 287-309.

STEPHENSON P. (2013) Twenty years of multi-le┗el go┗eヴミaミIe: けWheヴe Does It Coマe Fヴoマ? What Is It? Wheヴe Is It Goiミg?げ, Jouヴミal of Euヴopeaミ PuHliI PoliI┞ ヲヰふヶぶ, ΒヱΑ-37.

YANAKIEV A. (2010) The Europeanization of Bulgarian regional policy: a case of strengthened

centralization, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 10(1), 45-57.

1Interview, Member of the European Parliament (MEP), 24/04/2012.

21

2The other one, JEREMIE, being dedicated to supporting small and medium enterprises (SMEs). 3See: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/informat/2014/financial_instruments_en.pdf [Accessed 25/12/2013]. 4 Council Regulation (EC) 1083/2006, Regulation EC 1080/2006 and Commission Regulation 1828/2006 and their successive amendments. 5See: http://northwestevergreenfund.co.uk [Accessed 23/12/2013]. 6See: http://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/business-economy/championing-london/london-and-european-structural-funds/european-regional-development-fund/jessica-london-green-fund [Accessed 19/12/2013]. 7For a profile of Wielkopolskie see: DĄB‘OW“KI M. aミd ALLAIN-DUPRÉ D. (2012) Public Investment across Levels of Government: The Case of Wielkopolska, Poland. OECD, Paris. For that of Andalusia see Chapter 1 of MARCHESE M. and POTTER J. (2011) Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development in Andalusia, Spain, OECD LEED Working Papers, 2011/03, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kgdt917nvs5-en [Accessed 19/12/2013]. 8Source: Eurostat. 9Interview, Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego (BGK), Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 10Interview, Marshal Office, Wielkopolskie, 02/07/2012. 11 Interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013; interviews, Junta of Andalusia, 15/04/2013. 12Interview, MEP, 24/04/2012. 13 Interview, Marshal Office, Wielkopolskie, 02/07/2012; interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012;interview, EIB, Andalusia, 15/04/201. 14Interview, MEP, 24/04/2012. 15 For a useful overview of PPPs see e.g. OSBORNE, 2002; BINKERHOFF and BINKERHOFF, 2011. For a discussion on the use of this practice specifically in urban development policy see e.g. KOPPENJAN and ENSERINK, 2009. 16Source: http://bazappp.gov.pl/ [Accessed 19/12/2013]. 17Interview, Marshal Office, Wielkopolskie, 02/07/2012. 18Interview, Expert, Andalusia, 10/04/2012; interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013. 19 Interview, Expert, Andalusia, 10/04/2012; interview, Junta of Andalusia, 15/04/2013. 20Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 11/04/2013. 21Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 11/04/2013. 22Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interview, Instituto para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía (IDAE), Madrid, 18/04/2013; interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 12/04/2013. 23Interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 24In Wielkopolskie the basic interest rate for JESSICA loans was set at 4.75%, but it could be lowered to 2.75% if the project scored high on its social component. 25 Written communication, Ahorro Corporación Financiera (ACF), Madrid, 30/07/2013. 26Interview, Expert, Andalusia, 10/04/2012. 27Interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013. 28Interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. Similar comment: MEP, 24/04/2012. 29Interview, Ministry of Regional Development (MRD), Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 30Interview, MRD, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 31Interview, Beneficiary, Wielkopolskie, 03/07/2012; interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 32Interview, DG REGIO, 23/04/2012. 33Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 12/04/2013. 34 Interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013. 35 Interview, DG REGIO, 23/04/2012. 36Interview, MEP, 24/04/2012; interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interviews, Junta de Andalusia, Andalusia, 15/04/2013; interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013; interview, ACF, Madrid, 18/04/2013; Interview, IDAE, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 37 Interview, ACF, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 38Interview, MEP, 24/04/2012. 39Interview, IDAE, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 40Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 41 Interview, Marshal Office, Wielkopolskie, 02/07/2012. The problem was also highlighted at the JESSICA Networking Platform seventh meeting in Brussels (27 June 2012), see: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/thefunds/instruments/jessica_network_en.cfm#1 [Accessed 10/07/2013] 42Interview, ACF, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 43 Interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 11/04/2012; interview, MEP, 24/04/2012. 44Interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 12/04/2013. 45 Interviews, Junta of Andalusia, 15/04/2013. Similar comments - interview, IDAE, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 46Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 11/04/2012; Interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interview, MRD, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 47Interview, DG REGIO, 23/04/2012. 48Interview, ACF, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 49Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013; interview, Beneficiary, Wielkopolskie, 03/07/2012. 50Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 11/04/2013; interviews, Junta of Andalusia, 15/04/2013; interview, Expert, Andalusia, 15/04/2013. These findings corroborate the expectations from early evaluation reports, see Webb et al., 2011. 51Interview, EIB, Andalusia, 15/04/2013; interview, ACF, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 52Interview, IDAE, Madrid, 18/04/2013; interview, Ministry of Economy, Madrid, 19/04/2013; Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 53Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012.

22

54Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; interview, Beneficiary, Wielkopolskie, 05/07/2012; interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 11/04/2012. 55Interview, Beneficiary, Wielkopolskie, 05/07/2012. 56Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 57 The weak public-private cooperation was also stressed as a challenge by the JESSICA Lessons Learned Working Group, see: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/thefunds/instruments/jessica_network_en.cfm#1 [Accessed 10/07/2013] 58Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 59Interview, Beneficiary, Andalusia, 12/04/2012; interview, Ministry of Economy, Madrid, 19/04/2013; interview, IDAE, Madrid, 18/04/2013. 60Interview, ACF, Madrid 18/04/2013. 61Interview, BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. 62Interview, DG REGIO, 23/04/2012; interview, MEP, 24/04/2012; interview, Ministry of Economy, Madrid, 19/04/2013 63 Interview, MEP, 24/04/2012. 64 Interview, MEP, 24/04/2012. 65Interview, Expert, Warsaw, 04/07/2012. Similar comments in interviews with MEP, 24/04/2012; Beneficiary, Wielkopolskie, 03/07/2012; BGK, Warsaw, 04/07/2012; Ministry of Economy, Madrid, 19/04/2013; Beneficiaries, Andalusia, 11-12/04/2012. 66Interview, ACF, 18/04/2013. 67Interview, Ministry of the Economy, Madrid, 19/04/2013; interview, ACF, 18/04/2013; interview, MEP, 24/04/2012; interview, Junta of Andalusia, 15/04/2013. 68 See Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and the Council of 17 December 2013: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:347:0320:0469:EN:PDF [Accessed 25/12/2013].