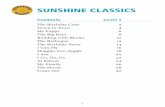

Engaging North Korea through Non-traditional Security Cooperation--Development of Inter-Korean...

Transcript of Engaging North Korea through Non-traditional Security Cooperation--Development of Inter-Korean...

1

Engaging North Korea through Non-traditional Security Cooperation--Development

of Inter-Korean Relations since the Sunshine-Policy Era

Joseph Y.S. Cheng

Professor (Political Science)

Coordinator,

Contemporary China Research Project

City University of Hong Kong

E-mail address: [email protected]

YU Mengyan:

Ph.D. City University of Hong Kong

Email address: [email protected]

2

Abstract

How to engage North Korea has always been a key concern of South Korea’s foreign

policy makers since Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy era. Instead of provoking political or

even military confrontations with North Korea in the traditional security arena, the

engagement policy is believed to allow South Korea to seek possible breakthroughs in the

non-traditional security arena. In return, engagement strategy is expected to generate a

spill-over effect enhancing both Koreas’ mutual political trust thus promoting political

cooperation in long term. Through analyzing relevant data and political events in the past

decade, this article examines the inter-Korean relationship in the non-traditional security

arena and argues that the inter-Korean relationship in the non-security arena is still a fragile

one, which is highly dependent on mutual political trust volatility and symbolic

cooperation projects. The economic and cultural cooperation initiated by South Korea

primarily targets to support North Korean in a patronizing manner instead of promoting

equal civil cooperation. Regional political powers also could easily affect the inter-Korean

cooperation dynamics. In the foreseeable future, improvement in mutual political trust and

the promotion of political dialogue between the two Koreas, as well as mindfulness to the

regional power shift, still present as the key to a peaceful inter-Korean relationship.

Keywords:

North Korea, engagement policy, U.S. foreign policy, Korean Peninsula, reunification

I. Introduction: A Framework to Consider South Korea’s Engagement Policy

When Park Geun-hye was still a presidential candidate in 2011, she already wrote in

Foreign Affairs to explain her policy framework of building trust between Seoul and

Pyongyang (Park, 2011). Her administration’s policy towards North Korea later has been

presented as a balanced combination of policy options including pressure and dialogue,

deterrence and cooperation, while separating humanitarian issues from those related to

3

politics and security. The agreement between two Koreas on the normalization of the

Gaeseong Industrial Complex in mid-2013 has been regarded as a model of Park’s

trustpolitik yielding positive results (Yun, 2013, p.8-14).

The Park administration intends to present the agreement as the consequence of its

sticking to a consistent position that Pyongyang has to respect international standards and

norms and abide by its promises, or otherwise pay a penalty for broken promises.

Meanwhile, Seoul’s decision to allow humanitarian assistance to be provided to North

Korea through international organizations such as UNICEF is also in line with one of the

central tenets of trustpolitik.

Trust is one of the most important components essential to the generation of cooperation

among individuals and among nations. It is a form of social capital that helps raise the level

of efficiency of transactions in a community. South Korean Foreign Minister Yun

Byung-se argues that in order to build a more enduring and lasting trust, one party must

clearly show the willingness to use robust and credible deterrence against breaches of

agreements by the other parties, while leaving open the possibility for constructive

cooperation (Yun, 2013, p. 13).

Chinese experts on the Peninsula affairs perceive the trust-building approach of

President Park Geun-hye as an attempt to steer a third path of engaging North Korea that

puts an emphasis on economic cooperation, dialogue and exchange along the line of her

predecessors Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. But regarding national security and

values, she would inherit the inter-Korean policy of Lee Myung-bak from the Grand

National Party, which appears a tougher one than Kim’s Sunshine Policy. Just before and

after the election of Park Geun-hye, Pyongyang launched a satellite and conducted a

nuclear test, leaving little room for compromise for the Park administration which has been

forced to maintain a hawkish line.

Social scientists like Henry Farrell and Jack Knight define trust as “a set of expectations

4

held by one party that another party or parties will behave in an appropriate manner with

regard to a specific issue” (Farrell & Knight, 2003). Mark Suchman considers that trust is

built by repeated compliance with norms and established rational expectations for

behaviors (Suchman, 1995).

The realist school of international relations scholars perceive the international system as

an anarchy without a world government and a global police force. Yet they still accept that

trust is a key element in strategies to induce, deter and compel behaviors when dealing with

friends and enemies (Schelling , 1966; George & Smoke, 1974). Richard Ned Lebow

argues that trust and cooperation are closely connected, though cooperation is still possible

without trust; sustained cooperation, however, requires a high level of trust. Treating

countries as ends in themselves helps to build trust, and facilitates cooperation, which in

turn builds common identities and more trust (Lebow, 2013; Lebow, 2008). This article

intends to examine Seoul’s engagement of North Korea through non-traditional security

cooperation, and its impact on inter-Korean relations since the Sunshine Policy era. As

observed by Mel Gustov, in authoritarian and democratic states alike, a policy of

engagement with adversaries in order to achieve peace and cooperation is often politically

risky. Failure to achieve expected goals during the past leaderships maybe perceived

domestically and internationally as weak or naïve; this failure may lead to electoral defeats

in democracies (Gustov, 2013). This is exactly the dilemma faced by South Korean leaders,

one obvious example is that both Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun are attacked by their

political competitors as ineffective and naïve in promoting engagement strategy.

Successful constructive engagement, i.e., an engagement policy which brings results,

must secure strong domestic support, especially in democratic countries. According to

David Baldwin, U.S. electoral politics have tended to reward those who take a tough line

towards states that the nation dislikes or with which it has serious disagreements. “It is

‘honorable’ to fight but ‘dishonorable’ to buy one’s way out of a fight” (Baldwin, 1971,

5

p.34). Those who advocate engagement may easily be criticized of “appeasement” by their

rivalries in elections. Baldwin’s observation of U.S. electoral politics may well apply to

other democracies such as South Korea’s engagement with North Korea.

It is thus a challenge for a South Korean political leader to promote engagement with

North Korea, such as convincing the electorate that engagement is the best option available.

Miroslav Nincic’s study of the U.S.’s post-WWII record shows that U.S. military threats

and interventions had achieved only about 40% of the planned objectives of that time; for

economic sanctions, the record is far worse (Nincic, 2013, Warren, 1999). At this stage, a

South Korean leader will find it difficult to convince the domestic public that in

inter-Korean relations, carrots are more effective than sticks. However, several studies

indicate that most South Koreans are also not inclined to support a policy of total pressure

and sanctions against North Korea, especially given the fact that both sides belong to the

one Korean ethnicity.

Foreign Minister Yun Byung-se is certainly aware of these sentiments when he presents

the trustpolitik of the Park Geun-hye administration. He quotes the Korean proverb that

“one-handed applause is impossible” and argues that “in order to build a more enduring

trust, one party must clearly show the willingness to use credible deterrence against

breaches of agreements by the other party, while leaving open the possibility for

constructive cooperation” (Yun, 2013, p.13). Walter C. Clemens Jr. proposes that lessons

could be learnt from the way of how the U.S. and the Soviet Union had slowly reduced the

tension in their bilateral relationship during the Cold War; he considers that the model

could be modified and applied on the Korean Peninsula (Clemens, 2013). He was largely

analyzing the relations between the U.S. and North Korea when he raised the question of

who would make the first move, his analysis and question may also be applied to the

inter-Korean relationship since Pyongyang regime is the weaker party which also suffers

from an acute sense of insecurity; it is generally expected that at this juncture, the initiative

6

for engagement has to come from Seoul.

The engagement policy initiated by South Korea may well be perceived as a conspiracy

attempting to bring about “peaceful evolution” in North Korea. Even Chinese leaders in the

era of economic reforms and opening to the external world share this perception of

conspiracy (Cheng, 2012, p.10-12), despite the fact that they have been trying hard but

have failed to persuade their counterparts in Pyongyang to follow their model of economic

reforms only. Few would dispute that the best way to change North Korea is to promote

change from within, and the best way to achieve such a change is to expose the country to

information and people from the outside world, in much the same way that Communist

Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were transformed by exposure to the West (Lankov,

2013; Thomson & Seo, 2013). And South Korea is the best candidate for such kind of

engagement, the U.S. and perhaps Japan too should support and coordinate with South

Korea in its approach to North Korea in the purpose of maximizing their alliance’s interests

in the region.

The Gaeseong Industrial Complex is a good example of South Korea’s engagement

policy. It was an initiative by the Hyundai Group more than ten years ago in the beginning

of Seoul’s Sunshine Policy. It has encountered many difficulties, but its significance is that

Pyongyang has never wanted to abandon the project. Recently the Park Geun-hye

administration plans to internationalize the complex by attracting non-South Korean

enterprises (Stangarone, 2013), and further brands the products of the complex in

overseas market1. The Park administration tries to include products from the GIC in its

increasing free-trade agreements (FTAs), so far India, Singapore, ASEAN and the

European Free Trade Association have included provisions granting access to their markets.

FTAs signed with the U.S. and the European Community have also offered processes

allowing both parties to add access to GIC at a later stage. GIC has fully indicated how hard

1 In April, 2014, the GIC cooperation association firstly promoted the brand of “SISBRO” to South Korea and other foreign countries, expecting to brand the products made in GIC.

7

the Park’s administration is trying to promote trustpolitik through experimental economic

cooperation projects with North Korea, in line with her predecessor Kim Dae-jung’s

Sunshine Policy, how to engage the North would remain South Korea’s central policy in

the coming years.

II. Historical Background of the Korean Peninsula’s Division

Division and Ideological Confrontation

At the end of WWII, the Soviet Union’s leader Stalin agreed to the United States’

suggestion of dividing the Korean Peninsula along the 38th

parallel. The Republic of Korea

was established on August 15, 1948, and Lee Seong-man became its first president. On

September 9 of the same year, Kim Il-sung announced the establishment of the Democratic

People’s Republic of Korea in Pyongyang (Li, 2007, p. 3-6). Since then, unification under a

victory of its own ideological camp became the central task of both Lee Seong-man and

Kim Il-sung. South Korea at that time advocated “unification first, development second”

with the enforcement of military containment. Kim Il-sung advocated a free presidential

election on the peninsula without foreign interference, and a federal political system as a

transitional mechanism towards a truly unified state (Kim, 1981, p. 243-44). However,

South Korea started facing increasing domestic challenges against Lee’s autocracy, and the

North’s economy performed better than the South at the start.

South Korea’s Focus Shifting to Economic Development and Peaceful Unification

Park Chung-hee started leading South Korea through a historic and legendary

development era from early 1960’s to late 1970’s. His unification policy evolved from the

conservative start to “construction first, unification later” stand, as he explained that the

modernization of South Korea would be the interim goal of the final national unification

with North Korea (Collection of President Park’s Speeches, 1971, p. 30).

As South Korea’s economy created the “Han River Miracle” and emerged as one of the

8

Four Little Dragons of Asia, the economic power balance between both Koreas started

changing since 1970.

Table 1

Source:

http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/286215/south-korea-vs-north-korea-gdp-edition-veronique-de-rugy

North Korea didn’t yet abandon the ideological confrontation, as Kim Il-sung regime

presented the concept of “South Korea Revolution” in 1964, by denying the legitimacy of

South Korean government and emphasized transforming South Korea through a total

political revolution. The Park administration took a series of measures consolidating its

initiatives in the unification dialogue. The Homeland Unification Ministry was established

in 19692, and President Park expounded his “Peaceful Unification Framework” on August

15, 1970. As South Korea set ambitious developmental goal for its economy, it naturally

downplayed the necessity of confronting North Korea with a hawkish line. In 1971, the

reunion meeting of separated families was successfully organized by both Koreas’ Red

Cross Societies; it was a historic start for civil communication on the peninsula. On July 4,

1972, a joint declaration was announced after high-level official meetings, it emphasized

the pursuit of peaceful unification under no foreign interferences and surpassing

2 It is the precursor of the current South Korean Unification Ministry.

9

ideological differences. The “7.4 Joint Declaration” was the first political outcome from

high-level officials’ dialogue and it was the outcome of ameliorated regional ideological

confrontation among big powers. The civil and political meetings between the North and

the South in the early 1970s established two channels for inter-Korean dialogue for the first

time. From 1960 to 1979, the average annual export growth rate of South Korea reached

39.2%, when the world average was 9.3% (Gao, 2002, p. 344). According to World Bank

data, North Korea’s GDP was more than three times of South Korea’s in 1960’s, but as

South Korea caught up in 1970’s, the discrepancy kept enlarging between them.

Table 2

On June 23, 1973, President Park Chung-hee updated his policy about unification

through the “623 Announcement”, which stressed that South Korea would accept that both

Koreas could join the United Nations and other international organizations together

(Collection of President Park's Speeches, 1971, p. 165). By the mid-1970’s Park

recognized that unification had become a long-term issue and how to ensure a peaceful

unification process should be South Korea’s concern.

On the other hand, Park’s proposal in 1973 was immediately turned down by Kim Il-sung,

who reiterated his advocacy for Korean federalism and emphasized the importance of

joining the United Nations as a unified state. However, in an official letter sent to the Chun

10

Doo-hwan administration in 1980, the North Korean Prime Minister finally used the

official name of South Korea indicating the actual acceptance of the legal status of South

Korea.

Inter-Korean Relationship in the Post-Cold War Era

South Korea went through a fundamental change until the early 1980’s as it became

of the first East Asian countries democratized. The first democratically elected president

Roh Tae-woo, at the end of the Cold War, proposed Nordpolitik Policy, which

that South Korea would pursue a normal and friendly relationship with communism

countries. By the time Roh became president, South Korea’s GDP had increased 25 times

from that of 1962 (Wang, 1992, p. 112), ranking the thirteenth in the world3. On July 7,

1988, Roh Tae-woo officially announced the arrival of an era that would be above

in his “77 Declaration”4, he argued that the unification issue should be resolved according

to international norm. The Nordpolitik Policy brought South Korea a diplomatically

fruitful era, as it became a member of UN in 1991, established formal diplomatic

with the Soviet Union (in 1990) and China (in 1992). With a further consolidated political

and economic reputation in the international community, South Korea becomes the active

party in the inter-Korean relationship.

III. Functionalism, Engagement, and Ideology

In contrast to the traditional view of political realism, functionalism views international

politics as intrinsically cooperative rather than conflictual, David Mitrany formulates

classical functionalism and argues that it is essentially “a prescription for a

welfare-oriented approach to world order” (Kim and Winters, 2004, p. 60-61).

Cooperation advocated by functionalism is usually perceived as the domain of “low

politics”, but in these less politicized dimensions, sustainable mechanisms may still be

able to maintain peace and even influence inter-state relations. “In essence, functionalism

3 Per capita GDP ranking the thirteenth, total trade volume ranking the twelfth. 4 Special Declaration in the Interest of National Self-Esteem, Unification and Prosperity

11

sees the territorial state system as incapable of resolving borderless social and economic

problems”, it instead emphasizes the construction of functional institutions following the

fluid social demands rather than rigid state interests. “Peace will not be secured, peace is

built by pieces.” (Kim and Winters, 2004, p.62)

In other words, engagement is a less confrontational way of conflict management, such

as that in the inter-Korean relationship. Conflicts exist in the political arena, but

opportunities exist for economic, social and cultural exchanges, co-operation as “conflict

management allows for dyadic interactions at multiple levels.” (Kim and Winters, 2004,

p. 62) In line with the arguments of functionalists, conflict management through

engagement implies a potential causal effect between non-traditional and traditional

security cooperation. Rejecting the perspective of a zero-sum-game in traditional security

environment, engagement in non-traditional security arenas would create more

flexibilities, and more importantly economic cooperation, cultural and ideological

influences may spill over into the political arena and ameliorate inter-state relationship.

Agreeing with the spill-over effect, scholars raise different types of engagement. Son

(2006) has elucidated three levels of comprehensive engagement: domestic, inter-state

and global, which correspond to the three parameters of identity shifts, the status quo and

integration (p.45). According to the three parameters, a comprehensive engagement

process goes through domestic identity shift, status quo between states, and final

trans-political-boundary integration. Victor Cha (2000) argues for three different modes

of engagement, namely interdependent, transnational, and concerted; which separately

focus on inter-governmental ties, non-governmental cooperation, and accommodating the

target state’s interests. The ideal type of engagement involves all the three and Cha

further argues that “the third concert engagement model might be a feasible path for

inter-Korean relations”. One essential challenge of engaging North Korea is the lack of

political trust and the “peaceful absorption/evolution” complex even if the South warily

accommodates the former’s interests, as “the two sides can only conceive of unification

as dominance of one state over the other” (p. 83), especially in an ideological sense.

12

The inter-state engagement does not rule out the imposition or threat of sanctions

(Suet-tinger, 2000, p. 28; Reiss, 2000, p. 46). It includes different forms of action,

ranging from liberal political dialogue to military deterrence, from cultural

communication, humanitarian aid to economic sanction. “As comprehensive engagement

is defined as a policy employed by a status quo power, any significant change in power

constellations, shattering the status quo, leads automatically to an end to engagement.”

(Son, 2006, p. 54) With North Korea being the traditional communism comrade of China

and South Korea being the traditional ally of United States in East Asia, the volatile

engagement dynamic between them has been typically influenced by the regional power

shift. It has to switch between “carrots” and “sticks” to both engage North Korea and

maintain the status quo with big powers. The two opposite ideologies lead them to drive

on divergent developmental paths, the North on nuclear one and the South on economic

one. Engagement targets political mutual-influences and harmony as the ultimate purpose,

engaging North Korea, though being South Korea’s strong faith, still needs much more

political trusts from the North Korean side and, more importantly, its actual cooperative

actions.

South Korea’s Engagement Strategy: from Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy to Park

Geun-hye’s Trustpolitik

Kim Dae-jung5 proposed Sunshine Policy as the guideline of his administration to

engage North Korea, it advocates mutual communication and cooperation, as well as a

separation between political and economic issues. In contrast to the containment and

confrontation with the North during Cold War, President Kim intended to initiate “a

process of strategic interaction in which a set of policies, non-coercive in nature, are

designed to elicit co-operative behavior and establish norms of reciprocity with the target

or adversary state” (Cha, 2000, p. 77). Co-operation and communication between the two

5 The former president of South Korea from 1998 to 2003.

13

Koreas had been much constrained by political suspicion derived from ideological

confrontation, and thus separating political and economic issues could greatly simplify

the process of engagement. The three principles of Sunshine Policy are: no military

offences, no ideological assimilation, co-operation in possible and operable areas; all

indicate the efforts to approach the North without offending its fundamental state

interests. As the concert engagement is mentioned by Victor Cha, the co-operation

defined by Sunshine Policy exists in the premise that promotes “adjusting one’s own

policies to accommodate the interests of the dissatisfied target state” (Cha, 2000, p. 78).

Whether this compromise will get rewarded has always been doubted within South Korea,

a survey conducted by Gallup in 2006 has proved that 50% of South Koreans agree that

economic support for North Korea can be the key to solving the North Korean nuclear

issue, with as high as 43% opposing this idea, and 26% of South Koreans say the only

solution of the North nuclear issue are strong economic and military sanctions. Originally,

the Sunshine Policy is designed to economically engage North Korea then later ignite

political intimacy and nostalgia for a political unification within their ethnicity.

However, South Korea’s engagement strategy also often faced serious resistance from

the North Korean side, as the latter maintained a zero-sum mentality by even refuting a

win-win co-existence. South Korea’s rising economic and cultural influences have

demonstrated a manifestly realpolitik possibility to impact North Korea’s developmental

path, and North Korea’s opaque policymaking process mysteriously represents a mix of

rigid self-reliance and bald tactics of brinkmanship. Such rigidness and baldness result in

a North Korea’s constant suspicious and volatile attitudes towards engagement strategy.

On August 22, 1998, North Korea enunciated its strategic goal of “Strong and Prosperous

Nation”, proposing to realize it by the beginning of the 21st century. This national goal

includes two important subordinate political goals: the ideological goal of juche6,

6 The Korean translation of this term literally means “subject”, a frequently referred term in Marxism phylogophy.

14

meaning independence and the “spirit of self-reliance” (Cumings, 2005); the military goal

of seon’gun, orienting its national investment towards military development and granting

the Korean People’s Army with a priority role in national development. Furthermore, the

North revised its Constitution in 1998 and “further strengthened the power of the

National Defense Commission (NDC)” (Haggard and Noland, 2011, p. 8) regarding the

significance of the above goal. North Korea still inherits a pattern of Cold War thinking,

it allows mere space to cultivate political trust because it still believes in communism’s

“ultimate success”, hence it regards cooperation with engagement as a form of

appeasement. Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy era, “Seoul’s responses and discourses on

the Korean conflict have shifted from conflict suppression through deterrence to conflict

regulation based on a wide range of social and economic co-operation” (Kim, 2004, p. 5).

Mel Gurtov claims that “engagement is not an act of charity or a weak-kneed attempt to

postpone the inevitable; it is a course of action chosen because of its expected benefits.

Adversaries need to be aware of the opportunity costs of rejecting engagement” (Gurtov,

2013, p. 12). Critics claim Kim’s policy has one loophole that South Korea optimistically

overestimates how much North Korea needs this amicable guideline along with the

concrete economic supports. Both Western media and South Korean media have reported

that North Korea not only relies on weapon, fake U.S. currency, and even drug deals for

concrete income, but also establishes the “38 Office” and trains its diplomats to ensure

the state’s systematic control of the illegal income channel.

The neo-functionalist metaphor of spill-over was what President Kim and his advisors

dreamed of in terms of genuine inter-Korean integration, through the envisioned nexus

between the government and civil society, between politics and economy. (Park M. L.,

2000, p. 159; Ku, 2000, p. 163). However, the progress was not smooth in reality, as both

empirical and policy evidence have argued above. Sunshine Policy is an initial

experiment of functionalism practice in inte-Korean politics. Terming it as “flexible

15

dualism”, Moon (1999, p. 39) summarizes the functionalist elements of the Sunshine

Policy as follows: (1) easy task first, difficult tasks later; (2) economy first, politics

later; (3) non-governmental organizations first, governments later; (4) give first, take

later. Previous South Korean governments failed to resolve the inter-Korean stalemate

partially because of the principle “government first, civil society later”, “politics first,

economy later” and the “primacy of mechanical reciprocity”, President Kim’s

“incremental, pragmatic and functionalist” approach symbolized a paradigm shift in

Seoul’s policy toward Pyongyang. No matter how appeasing it appears, Sunshine

Policy for the first time encouraged North Korea to promote cooperation with the

international community in pursuit of its own interests rather than to compromise its

interest.

Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy era was by far the most fruitful engagement period

between South Korea and North Korea, with the climax of his historic visit to Pyongyang

for a summit meeting with Kim Jung-il in June 2000. Domestic criticism focuses on

worries and doubts over South Korea’s democratic future, as South Korean democracy is

claimed to be accompanied with both the presence of an authoritarian historical legacy

and an anti-communist tradition (Snyder, 2004, p. 21-22).

Sunshine Policy earned Kim Dae-jung international reputation and stimulated a

ferocious domestic debate over the appropriateness of engagement attitude towards the

North. Successors of Kim all held back to different extents as North Korea sporatically

sabotaged the outside world’s political trust. Park Geun-hye’s trustpolitik inherits Kim’s

fundamental ideas by further advocating “appeasement from strength” (Son, 2006, p. 13).

Despite North Korea’s provocative attitude, Park still believes in the fundamental benefits

of conversations based upon “trust and principle”. She promotes the concept of “New

East Asia” on different occasions and takes an unprecedented active position to seek for

China and U.S.’s concrete supports.

16

IV. Dancing with Two Major Powers through Engagement: China and the U.S. as

Two Determing Stakeholders

Even though engagement is supposed to focus upon non-political arenas, the

indispensable involvement of U.S. and China as two major powers has politicized the

process of engaging North Korea inevitably. For South Korea, U.S. plays a determinant

role in its successful economic take-off in the past decades. But China’s influences start

challenging the traditional power configuration in Northeast Asia in the recent years, for

the reason that it has irreplaceable political influences on North Korea and its massive

market represents irresistible economic attractiveness to South Korea. By 2012, China

became the biggest trade partner and the second most popular investment destination of

South Korea, now it means an important friendly neighbor instead of an ideological

enemy to South Korea, and the latter correspondingly transits to a much more balanced

diplomatic stand in the region.

Since the Roh Moo-hyun administration, South Korea has re-positioned itself as a

balancer among the major powers in Northeast Asia. It did not seek to change the existing

power pattern, but pursued its own independence and maximize its pragmatic interests

out of the game. President Roh initially proposed to transfer wartime control of South

Korean forces from Washington to Seoul’s command while promising a remained

commitment to a strong alliance (Dong-A Il Bo, 2005), especially with the frequently

deteriorating relationship with Japan, another U.S. ally in the region, South Korea has

been seeking more independent flexibilities.

Although Roh’s successor Lee Myung-bak stated that the relationship between South

Korea and China would not surpass that with the U.S., the relationship between China

and South Korea has witnessed impressive developments, which are defined as a

“comprehensive and co-operative partnership” in 2003 (Wen-Wei Po, 2008). In 2013,

17

Park Geun-hye visited the U.S. and China soon after her inauguration, which was the first

time that the new South Korean president visited China before Japan. Seoul has been

working hard to gain stronger political trust from Beijing and finally persuades it to

influence North Korea. Ever since Kim Jung-il’s death, China apparently has indicated

more possibilities of changing its North Korean policy, in wake of the volatile governing

style of the young successor Kim Jung-eun highlighted the fall of Jang Seong-taek.

“Since the economic crisis in North Korea that began in the early 1990s, China has

become deeply mired in dealing with the fallout from this, providing desperately needed

food and fuel to Pyongyang and playing unwilling host to hundreds of thousands of

refugees.” (Kim, 2004, p.86) China obviously felt the burden. As China is seen as the

revisionist communism country in North Korea’s eyes, many of China’s supports of

North Korea are actually not sincerely appreciated either. Hence China would be willing

to see South Korea engage North Korea with more initiatives without itself generating

any unnecessary high-profile political turbulence7.

7 North Korea and China’s “brotherhood” used to be portrayed as a “blood alliance”. According to the

China-North Korea Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance in 1961, one party should

support the other militarily during a situation of war; the treaty was automatically extended twice in 1981 and

2001, and it would remain valid until 2021. However, their bilateral political trust is fragile now, in the eyes

of Pyongyang, China at least twice betrayed Pyongyang’s political trust. In September 1975, the then U.S.

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger proposed the idea of “cross recognition” at the 30th

United Nations

General Assembly (Koo & Suh, 1984, p. 174). This proposal was criticized by China at that time as it was

strongly opposed to the “conspiracy of legalizing a permanent split of the Korean Peninsula” (Zhu, 2010) at

that time. Changes came when the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev proposed “New Thinking” in 1986 and

the South Korean president Roh Tae-woo initiated his “Nordpolitik Policy” in 1988. The Soviet Union and

South Korea improved their relations as economic ties led to formal diplomatic relationship in September

1990 despite North Korea’s strong opposition. As China engaged itself in economic reforms and opening to

the external world since the end of 1978, it also started pursuing an independent foreign policy from 1982 to

1988. The disintegration of the Communist bloc in 1989-1990 further placed South Korea at an advantageous

position relative to North Korea. In 1992, China established diplomatic relations with South Korea, which

obviously disappointed Pyongyang. After one decade in 2003, Seoul refused to let North Korea receive bank

transfer via Chinese agencies at the final stage of the Six-Party Talks, which led Kim Jung-il to cancle his

government’s dialogue with other Six-Party Talk countries. In many other crucial historic moments, China

18

Although China has sometimes been viewed as the most influential ideological partner

of North Korea, this ideological alliance might be the exact reason why the two ended up

in estrangement. B.R. Myers described the North Koreans as a highly homogeneous

population indoctrinated by a sacred mission influenced by an anti-Japanese complex,

Confucian cultural tradition and the Communist ideology (Myers, 2010). North Koreans

often see China as having “become a corrupted revisionist country which no longer

guards the right path of Communism”8. This assessment provides the reason for North

Korea’s chronical “soft-blackmailing” of China to support its economy and tolerate its

provocative behavior in the region as it considers itself maintaining the right path. The

fragile and limited political trust between China and North Korea has been a significant

cause of North Korea’s strong determination to develop nuclear weapons to protect the

regime’s ideological legitimacy.

The U.S. is still Seoul’s security protector as the latter “asked the U.S. to consider

delaying the 2015 transfer of wartime control of South Korean forces to Seoul’s

command because of North Korea’s nuclear threat” (Kwaak, 2013). North Korea’s

nuclear program stays as the fundamental political contradiction between itself and the

U.S.; to the Barack Obama administration, the premise for a dialogue is North Korea’s

promise to give up its nuclear program. The U.S.’s interests in Northeast Asia are “first to

defend South Korean sovereignty, and second to prevent the proliferation of weapons of

mass destruction globally” (Gallucci, 2000, p. 175). However, North Korea seems

unlikely to give up its only effective bargain chip in its political dialogues with the

outside world, as well as in the protection of its ideological tradition.

In sum, both the U.S. and China are passive players in the game of engaging North

Korea by having enough reasons to believe that maintaining stability on the Peninsula is

was perceived not to have offered strong backing to Pyongyang. 8 Information from Chinese social network Weibo, and interviews with North Korean civilians in

Pyongyang, 2009.

19

the least risk-taking and the most realistic option, and their attitude to engage themselves

in the process is in general passive, thus leaving South Korea meager space to acquire

concrete political trust alone. As South Korea flounders among the big powers frequently,

it still has struggled to explore a path of engaging North Korea since the past decade.

V. Economic Engagement: Incremental Cooperation or Appeasement in the Form of

Aid?

As early as in 2002, South Korea became North Korea’s second largest trading partner

after China (Kim, 2004, p. 57), the past decade has witnessed a general steady increase in

the trade transaction between both Koreas (Table 3 & Table 4). The only set-back

occurred in 2010 when the Cheon-an Incident took place.

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

20

On March 26th

, 2010, the South Korean navy fleet Cheon-an “was attacked” and sank,

killing 46 seamen. In April the same year, President Lee Myung-bak commented on the

sinking incident that “we have to find the cause in a way that satisfies not only our people

but also the international community” (Na, 2010). A South-Korean-led official

investigation delegation composed of experts from South Korea and Western countries

later reported that the warship sank due to a North Korean torpedo attack. As North

Korea, Russia, and the People’s Republic of China either deny or seriously doubted the

credibility of this report, the inter-Korean relationship deteriorated inevitably. South

Korea took the 5.24 Measure by stopping nearly all its trade with the North by May and

prohibited North Korean vessels from shipping through South Korean waters (Choe,

2010). The weak foundation of political trust still generates direct and immediate harm to

the economic engagement of North Korea, but when political drama calms, it often

resumes fast as inter-Korean trade jumped to an even higher level by 2012. This type of

quick resumption usually indicates the effort of South Korea taking initiatives to repair

the economic relationship, and usually the deal is doubted by critics as South Korea

offers preferential conditions to North Korea all the time.

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

21

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

The inter-Korean trade types reveal its dependence on pilot economic projects such as

the Mt. Geum-gang and the Gae-seong Industrial Complex (GIC). The products of GIC

amounted to 99.55% of the total inter-Korean trade volume, with the rest 0.45%

composed of processing-on-commission and non-governmental aid (Yonhap Press, 2013).

Since South Korea’s announcement of the 5.24 Measure in 2010, even the mere 0.45%

dropped to almost nothing (Table 5 & 6). Processing-on-commission used to be a most

popular type of trade between two Koreas, as through this mode of cooperation North

Korea could provide abundant raw materials and cheap labors, South Korea could

provide technologies and facilities. However, the sustainability of such a cooperation is

always in question as a higher level of political trust between the two Koreas can hardly

be secured, as one of North Korea’s most favored tactics is to threaten the South by

cutting all the communications.

On the other hand, South Korea actually accounts non-commercial transactions into the

trade statistics too, which exactly indicates its perspective about inter-Korean trade:

economic cooperation is “a component of a functional project of expanding interactions

22

and relations” with North Korea “in pursuit of a more peaceful and harmonious

coexistence or reunified existence” (Kim & Winters, 2004, p. 66). The economic-aid-like

trade record between both Koreas in fact “lowers the real quality” of economic

communication, as economically North Korea “cannot import South Korean goods to the

extent that it might like” due to a lack of hard currency (Kim & Winters, 2004, p. 67) and

an adherence to ideological pride, and politically this appeasement-like economic aid is

criticized to have spoiled North Korea to abuse the political trust from the outside world.

To South Korea, this stance involves its ethnic complex with the North and the political

calculation of maintaining basic stability on the peninsula. However, economic

engagement in this way has been criticized as appeasement in exchange for overvalued

political returns. The aid-oriented and project-centered economic engagement has

guaranteed the increase in trade volume, yet it always implies the weak foundation of

engagement which has neither been comprehensive nor solid enough. As mentioned

above, North Korea probably hasn’t been desperately dependent on foreign economic aid

since it manages its way of illegal income, meanwhile North Korea wouldn’t be able to

proceed the nuclear program given the collapsed domestic economy.

VI. Symbolic Pilot Projects in the Process of Engaging North Korea

Gaeseong Industrial Complex: Strengthening An Enclave of Economic Cooperation

through Political Support

In 1999, the founder of Hyundai Group Chung Ju-young reached agreement with

North Korean government about launching an industrial park within North Korean

territory. The Gaeseong Industrial Complex (GIC) project was officially announced in

2002 and finally launched in 2003. Used to be the ancient capital of the Goryo Kingdom,

the city of Gaeseong has a cultural and historical symbolic significance to the Korean

Diasporas, building an industrial complex there would definitely expand its symbolic

23

influences. The GIC is a multi-functional special economic zone, including Industrial

Zone, Living Zone, and Tourist Zone. The problematic perspective of special economic

zones like the GIC and Mt. Geumgang lies in their functioning as an ‘enclave’

comparatively exclusive to other regions on the North Korean soil (Chabanol, 2013, p.

51). Even though it has provided abundant job opportunities for North Koreans (Table 7

& Table 8), it doesn’t drastically accelerate the process of engaging North Korean civil

society as the North Korean government closely monitors these pilot projects.

24

Table 7 Number of Workers in the Gaeseong Industrial Complex

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Total 6,520 11,951 23,323 39,986 43,496 47,088 50,642 54,234

South

Korean

Workers

507 791 785 1055 935 804 776 786

North

Korean

Workers

6,013 11,160 22,538 38,931 42,561 46,284 49,866 53,448

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

Since Kim Jung-eun’s assumption of power, he firstly targeted GIC to demonstrate

how much he could manipulate the inter-Korean relationship. By early May 2013, most

of the South Korean staffs in GIC returned to South Korea due to North Korea’s

unilateral and sudden announcement of GIC’s closure. On the other hand, North Korea

unilaterally withdrew all of its 53,000 workers for the first time in the nine-year history of

the GIC (Kwaak, 2013). According to the statistics released by South Korean Unification

Ministry on June 25th

, 2013, the reported economic losses of South Korean companies in

GIC have reached 1056.6 billion Korean won (around 1 billion US dollars) (China News

25

Net, 2013).

Mountain Geumgang Tourism Zone: Satisfying South Koreans’ Nostalgia and

Cultivating a United Ethnic Memory

Another symbolic project is Mountain Geumgang tourism zone. Well known as a

mountain having four names in four seasons, Mountain Geumgang not only represents “a

Korean national identity”, but also becomes “an anti-imperialist war memorial” (Park,

2013, p.35). The promotion of this project is advocated by some South Korean celebrities:

in 1991, the T’ongil Group affiliated with the controversial Rev. Moon Sun-myung

sought an authorization to develop Mountain Geumgang as a tourism zone; meanwhile,

the former Chairman Chung Ju-young of Hyundai Group, South Korea’s largest

transnational conglomerate at that time, was making the final progress in obtaining the

authorization to exclusively develop the Mountain Geumgang tourism zone (Park, 2013).

The first South Korean tourists and reporters made their maiden trip to Mt. Geumgang in

1998 (Park, 2013), marking the fact that South Korean civilians could enter North Korean

territory as a significant symbol of an ameliorating inter-Korean relationship. Both GIC

and Mt. Geumgang projects were firstly suggested by influential South Korean celebrities.

Rev. Moon’s T’ongil Group has provided many personal economic aids and investments

in North Korea, and the hometown of former Hyundai Group Chairman Chung Ju-young

is in North Korea. The promotion of inter-Korean communication still depends upon

influential individuals’ efforts. Neither the governments nor the civil societies have

constructed a strong supporting mechanism for promoting engagement.

26

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

From the Table above we come to the conclusion that Mt. Geumgang has witnessed a

generally steady growth of tourists. South Korean citizens could visit this zone and hike.

It represents a new dimension for inter-Korean communication. However, an accident

taking place in 2008 has wreaked havoc on the inter-Korean relations, generating a great

political tension. A middle-aged female South Korean tourist walked into the restricted

area beyond the Special Tourist Zone during her morning walk and was shot dead by a

newly recruited female North Korean guard. The Geumgang tourism zone has not been

resumed since the incident for a long while, resulting in a sharp drop of cross-border

travelers from both sides (Table 10).

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

27

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

Both of the above projects are highly politicized, and the reasons they stopped are both

contingent and unexpected. More importantly, because their operations are under the

political control of North Korea, the economic prosperity of both is highly

mutual-dependent. As we can see from the above two tables, the number of visits to the

GIC have dropped since 2008 due to an intensified political situation.

After refusing all South Korea’s proposals to co-investigate the incident and publicize

the reports, North Korea announced that it would change relevant terms of the Mt.

Geumgang’s lease contract to the Hyundai Corp in April 2011. Instead of Hyundai Corp’s

28

unilateral exploration, Mt. Geumgang would be co-developed by both the North Korean

side and Hyundai Corp (Xinhua, 2011). After issuing Law of Mountain Geumgang

International Special Tourism Zone in May, 2011, North Korea announced that it would

re-open the Mt. Geumgang Tourism Zone in April, 2012 (Xinhua, 2012). In August 2013,

North Korea agreed to South Korea’s proposal of family reunion on the Middle Autumn

Day (Korean Thanksgiving Day) at Mt. Geumgang area; then it promoted another new

round of negotiation over reopening Mt. Geumgang tourist zone. With such a case similar

to the GIC development route, the state-level intervention from North Korea seems to be

able to arrive any time without a rationale reason or rhyme. The lack of political trust is

still the fundamental barrier hindering the engagement process of North Korea.

VII. Engaging North Korea through Civil Society: Humanitarian Issues

Engaging North Korea is expected to bring South Korea more international influences

and supports, thus promoting more civil society interactions in the long run but initially

promoted with government-funded projects in short term. Different from economic

engagement, humanitarian aid is considered as promoting communication instead of

“being subject to accusations of appeasement or bribery” (Son, 2006, p.64). South

Korea’s generous humanitarian aid indicates its belief in the inter-Korean ethnic nexus, as

well as its purpose of an ultimate engagement, which is to ameliorate the humanitarian

and developmental situation in North Korea.

29

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

Since the first reunion meeting and mutual visits organized by the Red Cross in both

Koreas in 1985, there has been 56,544 South Korean applicants accepted for reunion with

their separated families by September, 2013, amounting to 43.8% of the total South

Korean applicants (129,218). The current mechanism of separated families’ reunion

works with a quota system, only 100 applicants can get permission every year to visit, but

the visit hasn’t even taken place in recent years at all due to deteriorating political

tensions (Chosun Daily, 2013). According to South Korean National Assembly Health

and Welfare Committee, half of the existing applicants were more than 80 years old,

Table 13 also indicates the sharp drop of separated families’ communication in recent

years, as more aged applicants might pass away. Then the separated family would

eventually become a historical term.

30

Source: UN Millennium Development Goals Indicator,

http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspx

Another humanitarian issue presenting lasting challenge is the North Korean refugee

issue. Both the deteriorating humanitarian situation in North Korea and more informal

access to information about the outside world have great impact on the defection of North

Koreans. The United Nations MDG data shows that in the past two decades, there was

almost a constant 30% or more of the North Korean population being undernourished,

whereas this figure in South Korea was generally lower than 10% (Table 14). South

Korea naturally becomes the most wanted destination of these defectors, and the South

Korean government has made a constant effort to facilitate North Korean defectors to

integrate themselves into South Korean society9.

9 South Korea has mainly launched two programs supporting North Korean defectors’ life, one is the settling down program targeting North Korean defectors, the other one is the comprehensive associative assistance program targeting North Korean youth and teenager defectors.

31

Table 15 below shows the gender proportion of the North Korean defectors in the past

decade. An increasing number of defectors left their fatherland and found their way to

South Korea, though there were three periods of a declining flow, i.e., 2004-2005,

2009-2010, and 2011-2012, which are separately marked by two nuclear crisis and Kim

Jung-il’s death. The number of defectors increased by 7.8% from 2000-2011, but sharply

dropped since the death of Kim Jung-il at the time when North Korea tightened the

political control.

Data Source: Ministry of Unification, the Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

This humanitarian concern has drawn constant attention from the international

community, which brings South Korea more supports but also potentially complicates the

engagement. As the neighbor with North Korea, China plays a vital role in the North

Korean defector issue since it is the first destination of these refugees. China has long

agreed at North Korea’s request to return all North Korean defectors in China; on the

other hand, China has to handle pressure from South Korea and international community

as it has long faced international accusation over its conducts on humanitarian issue. “The

problem confronts Beijing with a dilemma: a no-win situation that threatens to aggravate”

the relationship with both Pyongyang and Seoul (Kim, 2004, p. 88). In late February

2012, South Korean female Congressman Park Seon-young, the member of the

32

opposition Party went on an 11-day hunger strike in front of the Chinese Embassy in

Seoul, calling for a stop of over the defector issue. In order to keep engaging the North

Korean defectors, South Korea has to strike a balance between China and the

international value on human rights. For example, many South Korean religious groups

sent people to access and assist North Korean defectors along the border in Northeast

China. In 2000, one South Korean priest Mr. Kim was believed to be kidnapped by the

North Korean agents in Northeast China while he was assisting North Korean defectors

to leave China, which is denied by the Chinese side. According to the interviews with

some reliable information sources, in the border Chinese city of Tumen, a notorious

detention center keeping tens of hundreds of North Korean defectors operates for many

years. All the detained defectors are provided with food but wait to be repatriated back to

North Korea. South Korea certainly faces a policy dilemma as it cannot afford to offend

China while being unable to abandon a universal value to respect human rights.

Besides the political game behind this issue, fund shortage on various humanitarian

projects is another factor holding back the development of engaging North Korea.

Government grants have shrank drastically in the past decade and dropped sharply since

2007, private fund assistance even goes lower since then (Table 16). According to the

interview with a staff from the North Korean Strategy Center in Seoul, the lack of

confidence over North Korea’s political credibility is one major reason leading to the low

passion for donation in recent years, as many sponsors are observing North Korea with

the young Kim and calculating the possibilities. As such, engaging North Korean civil

society through humanitarian aids is facing no less political constraints than economic

cooperation, it wouldn’t be too much to claim that political engagement is the key of

solving a fundamental engagement deadlock between both Koreas.

33

Source: The Ministry of Unification, Republic of Korea, 2013 eng.unikorea.go.kr/index.do

VIII. Discussion: Fragile Trust, Dim Sunshine

The inherited engagement strategy of South Korea has successfully branded itself as an

open and friendly neighbor of North Korea in the post-Cold War era. It naturally grants

the South with more political initiatives regarding inter-Korean relation. However, the

following structural reasons have led to the destined failure of political trust construction

with North Korea: The first is an actual given-up domestic economic reform agenda of

North Korea. As brought up in the previous analysis, North Korea struggles about

whether it follows China’s opening and reform model or not, while managing a weak

domestic economy. In 2009, Jang Seong-taek, the prominent and famous liberal

economic reform pioneer within the North Korean power class, initiated the Currency

Reform but ended in complete failure at last. He himself and his faction were executed

out of the North Korean decision making club in 2013, indicating a scaling back of

reform policy in North Korea. For example, “North Korea modeled its Rajin-Sonbong

Free Economic and Trade Zone (established in December 1991) on post-Mao China’s

four special economic zones (SEZs) in Shenzhen, Shantou, Xiamen and Zhuhai” (Kim,

2000, p. 44), after North Korea announced the jurisdiction of Jang Seong-taek, his

supports of RSFETZ were defined as “a traitor behavior of his country by selling the

34

region to foreign countries”. As RSFETZ ended in abortion, it almost announces North

Korea’s failure or even refusal in experimenting economic reform. Among the three

possible scenarios raised by Kim (2000), North Korea has already crossed out the choice

of system-reforming, leading itself either towards system-maintaining or

system-decaying. By far North Korea undoubtedly strives to maintain its system and “the

viability of the system-maintaining scenario depends largely on the extent to which the

post-Kim Il Sung leadership can ride out the economic difficulties” (Kim, 2000, p. 41).

Secondly, since the economy staggers at the margin of collapsing, North Korea’s worry

over how to maintain the legitimacy of its regime increments unprecedentedly. It tries to

establish the absolute authority of “Baek-du Mountain Bloodline” even before Kim

Jung-il’s death, which claims the righteousness of the inherited power within the Kim

family. As North Korea lacks dependence on normal international trade market and its

domestic power highly concentrates within a small club, the state makes itself politically

least trustworthy as has been proved through its volatile reactions and disrespect to

international rules. Political brinkmanship is still the determinant factor in inter-Korean

relationship as it dominates North Korea’s attitude to South Korea’s engagement. History

has witnessed that domestic power shift or political instability within North Korea could

easily put the inter-Korean relation at stake. For example, during Kim Yong-sam’s

administration (1993-1998), because South Korean government didn’t send North Korea

letters of condolences when Kim Il-sung passed away in 1994 and banned relevant

condolence activities in South Korea, in the following year, North Korea detained the

South Korean shipmen who were in charge of shipping 150,000 tons rice to North Korea

as a volunteer donation. Then in 1996, the North Korean submarine “Shark” stranded on

the eastern shore of South Korea’s Gangreung city, with all the on board North Korean

staff landing in South Korea, 24 were shot dead and one arrested by the South Korean

side (Li, 2007, p. 163-170). When the political power cards are reshuffled domestically,

35

North Korea has disappointed the outside world by reinforcing its domestic legitimacy

through aggressive provocations instead of gradual reforms. After Kim Jung-il passed

away in 2012, the new young leader Kim Jung-eun surprised the whole international

community: on December 12th

, 2012, North Korea launched a satellite successfully; on

February 12, 2013, North Korea conducted a third round of nuclear test successfully

among flooding international criticisms; following the US-South Korean annual joint

winter military exercise in 2013, the Supreme Command of DPRK People’s Army

announced that the Korean War truce was invalid on March 5, 2013; then North Korea

closed the Gaeseong Industrial Complex on April 3 and expelled all the South Korean

citizens from the GIC. The new leader tries to just do something surprising to show off

North Korea’s power and determination to the outside world.

Last but not the least, based upon the above two reasons, North Korea would not easily

embrace South Korea’s engagement in the need of consolidating domestic legitimacy and

ameliorating urgent economic difficulties. Instead, guarding its ideological and national

security maintains an unnegotiable premise to North Korea that only nuclear program

seems to be trustful. It has indicated little interest in reassessing its fundamental

ideological belief and policy paradigm, the hostile and confrontational perception of

engaging efforts enforces South Korea to step back almost all the time. “It is a swollen

garrison state fielding the fifth-largest army in the world (after China, India, Russia, and

the US) with its ratio of troops to total population being by far the highest for any country

in the post-Cold War era”, around 25.2% of North Korea’s GDP goes to its defense

expenditure, making it become the third-largest defense spender. (Economist, 1995; Kim,

2000, p. 37).

During the interviews with some North Korean cadres in Pyongyang, U.S. stands out

impressively as a keyword mentioned by them as in their perception of North Korea’s

foreign strategy, a conversation and bargain with U.S. is the point, one should despise

South Korea’s engagement effort as it’s only U.S.’s small ally. In the eyes of the North

36

Korean leaders, the international isolation and the UN resolutions both attribute to the

U.S.’s propaganda and influences. On February 14, 2014, South Korea media KBS

reported that “North Korea has been constructing underground tunnels in Ham-kyung

Buk-do and came to the conclusion that it might be possible there is another nuclear test

soon (Telegraph, 2013; New York Times, 2013), nuclear ambition obviously has never

been off the to-do list of North Korea.

In sum, as the tremendous economic and social discrepancy between both Koreas

exists, it seems least possible that North Korea would initiate an all-round reform. It has

already missed the golden timing for a gradual and peaceful reform, leaving the whole

world in expectation of its system decaying or even collapsing. If it continues to readjust

its perception of engagement, the dim sunshine preserved and fragile trust constructed

wouldn’t be able to promote a peaceful unification of the peninsula.

IX. Conclusion

This article has analyzed the background of South Korea’s engagement policy, the

development of economic and humanitarian engagement of North Korea in the past

decade. No matter how much South Korea and the international society emphasizes the

non-politicized engagement, building political trust with North Korea still holds the key

to a successful engagement. South Korea’s efforts to engage North Korea economically

have always been the strategic leverage to create conditions for political conversations,

this grants North Korea with actual initiative during the engagement game, and explains

its indifference and volatility to South Korea’s economic inducements, especially when it

went through domestic political turbulences. When the target state is an authoritarian

regime with little political transparency like North Korea, economic inducement would

not be able to guarantee a continuous success of engagement. (Brooks 2002, Kahler and

37

Kastner 2006). North Korea not only is scaling back its repressive policy line in recent

years, it still has extraordinary capacity to impose political costs on its population

(Haggard and Noland, 2011, p. 7). Unless the state evolves its stance, no forces by far

seems to be able to challenge North Korea’s capricious behavior.

In recent years, the Standard & Poor’s and Goldman Sachs have both published

promising reports in anticipating a promising unified Korean Peninsula economy

(Chosun Daily, 2014c; Wall Street Journal, 2009). Other international organizations such

as World Bank and UN also have high expectation over a unified Korea, both Jim Yong

Kim and Ban Ki-moon have commented that if North Korea makes an effort to deliver

political breakthrough, the international society will be willing to offer help as it did for

Burma (Chosun Daily, 2014d). Especially since President Park Geun-hye took power,

South Korea government has brought up the concept of Korean Peninsula Unification

Process in different occasions. As Jang Seong-taek was executed in 2013, South Korean

media surged with abundant reports in anticipation of a possible unification in near

future. However, a national poll in the very start of 2014 shows that the South Korean

population in favor of “an accelerating unification of Korean Peninsula” drops to its

original half size, with the population supporting “maintaining the current situation rather

than unification” doubles, more than 25% of South Korean youth belong to the second

category (Chosun Daily, 2014a). Besides the old, a growing number of South Koreans

show a decreasing care for the unification issue, and 37.7% of them view the political

instability in North Korea would defer the agenda of unification; 40.1% of South Koreans

prefer the unification under South Korean mechanism, though the people supporting the

co-existence of two political systems rise to 27.8% (Chosun Daily, 2014b). For many

South Koreans, North Korea has sabotaged the South’s trust repeatedly and it has become

an economic burden and a waste of energy for their democratic government to offer

North Korea assistance unconditionally. In addition, they don’t trust that North Korea

would give up its nuclear program. The South Korean republic seems impatient over the

inherent long-term engagement policy as they associate “engagement with appeasement

and weakness” too (Cha, 2000, p. 90), below the governmental level, there seems to be

serious estrangement between two sides’ civil societies. “Significant efforts must be made

38

to overcome cognitive rigidities, cultivate reciprocity, and elicit cooperation” (Cha, 2000,

p. 90). Even if unification takes place on governmental level, two societies will face the

challenge of integration in long term.

South Korea’s engagement strategy is not a status quo policy. As South Korean

economy surpassed the North’s since 1960’s, it has completed an identity transition

domestically through democratization and a series of flexible foreign policies; the real

barrier for inter-Korean political trust lies in North Korea, whose collapsed domestic

economy grants the regime little confidence to evolve politically. Besides expecting the

regime itself to change, a constant effort to engage seems to be the only pragmatic choice

left.

References:

(1970). Dong-A Il Bo (East Asian Daily). Seoul, South Korea.

(1971). Collection of President Park's Speeches. Seoul, President's Secretary

Office of the Blue House.

(1995). Defense Technology Survey. Economist London.

(1999). Democracy and Trust. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

(2006a). "Gallup World Poll: Implications of Reunification of Two Koreas."

(2006b). "Gallup World Poll: South Korea's Political Dilemma."

(2008). The Economic and Foreign Policy of Lee Myung-bak. Wen-Wei Po.

(2011). North Korea Announces to Establish Mountain Geumgang International

Special Tourism Zone, To Encourage Free Investmen. Xinhua News

Agency.

(2012). North Korea Announces the Re-opening of Tourism in Mountain

Geumgang since This April. Xinhua News Agency.

(2013). Close to Half of Separated Family Members Passed away, Even Fewer to

Be Left after 20 Years. Chosun Daily. South Korea.

(2013). Inter-Korean Trade is Cut due to the Close of Gaeseong Industrial

Complex. Yonhap News Agency.

(2013). South Korean Companies in GIC Announce to Move Out Their Facilities

Out of the GIC. China News Net.

39

Alexander L. George, R. S. (1974). Deterrence in American Foreign Policy: Theory

and Practice. New York, Columbia University Press.

Baldwin, D. A. (1971). "The Power of Positive Sanction." World Politics 24(1):

19-38.

Brooks, R. A. (2002). "Sanctions and Regime Type: What Works, and When?"

Security Studies 11(4): 1-50.

Byung-se, Y. (2013). "Park Geun-hye’s Trustpolitik: A New Framework for South

Korea’s Foreign Policy." Global Asia 8(3): 8-14.

Cha, V. D. (2000). Democracy and Unification: The Dilemma of the ROK

Engagement. The Two Koreas and the United States: Issues of Peace,

Security, and Economic Cooperation. W. Dong. New York, M.E.Sharpe:

76-93.

Chabanol, E. (2013). Heritage Management in the Gae-seong Special Economic

Zone. De-bordering Korea: Tangible and Intangible Legacies of the

Sunshine Policy. K. D. C. Valerie Gelezeau, Alain Delissen. New York,

Routledge.

Cheng, J. Y. S. (2012). Challenges for Hu-Wen and Their Successes:

Consolidating the ‘Beijing Consensus’ Model. China—A New Stage of

Development for an Emerging Superpower. J. Y. S. Cheng. Hong Kong,

City University of Hong Kong Press: 10-12.

Chung-in, M. (1999). Understanding the DJ Doctrine: The Sunshine Policy and the

Korean PeninsulaUnderstanding the DJ Doctrine: The Sunshine Policy and

the Korean Peninsula. Kim Dae-jung Government and Sunshine Policy:

Promises and Challenges. D. S. Moon Chung-in. Seoul, Yonsei University

Press.

Dong, W. (2000). The Two Koreas and the United States: Issues of Peace,

Security, and Economic Cooperation. New York, M. E. Sharpe

Dunqiu, L. (2007). Inter-Korean Relationship and Power Shift in Northeast Asia in

the Post-Cold-War Era. Beijing, Xinhua Press.

Gallucci, R. L. (2000). The US-North Korea Agreed Framework and the Korea

Policy of the United States. The Two Koreas and the United States: Issues

of Peace, Security, and Economic Cooperation. W. Dong. New York, M. E.

Sharpe.

Geun-hye, P. (September/October 2011). A New Kind of Korea: Building Trust

between Seoul and Pyongyang. Foreign Affairs. 90.

Gurtov, M. (2013). "Engaging Enemies: Fraught with Risk, Necessary for Peace."

Global Asia 8(2): 8-13.

Henry Farrel, J. K. (2003). "Trust, Institutions and Institutional Change: Industrial

Districts and the Social Capital Hypothesis." Politics and Society 31(4):

40

537-566.

Hoffmann, S. (1966). "Obstinate or Obsolete? The Fate of the Nation-State and

the Case of Western Europe." Daedalus 95(3): 862-916.

Il-sung, K. (1981). The Report at the Celebration Gala of (North) Korean People's

15th Annual Anniversary of Liberation and the National Festival of August

15th. Collected Works of Kim Il-sung. Pyongyang, DPRK Labor Party Press.

14.

Jeongju, N. (2010). Lee Warns against Speculation over Cheonan. Korea Times.

Seoul.

Key-young, S. (2006). South Korean Engagement Policies and North Korea:

Identities, Norms and the Sunshine Policy. New York, Routledge.

Kim, S. S. (2000). The Future of the Post-Kim Il Sung System in North Korea. The

Two Koreas and the United States: Issues of Peace, Security, and

Economic Cooperation. W. Dong. New York, M.E.Sharpe: 32-60.

Kim, S. S. (2004). Chapter One: Introduction: Managing the Korean Conflict.

Inter-Korean Relations: Problems and Prospects. New York, Palgrave

Macmillan.

Kim, S. S. (2004). Inter-Korean Relations: Problems and Prospects. New York,

Palgrave MacMillan.

Kwaak, J. S. (2013). Koreas Agree to Reopen Industry Park. Wall Street Journal

(World News).

Kwaak, J. S. (2013). Seoul Asks US to Stall Military Handover. Wall Street Journal

(World News Section).

Lankov, A. (2013). "Getting to Know You: How Social Exchanges Can Help Solve

the North Korea Problem." Global Asia 8(2): 32-37.

Leblow, R. N. (2008). A Cultural Theory of International Relations. Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press.

Lebow, R. N. (2013). "The Role of Trust in International Relations." Global Asia

8(3): 16-23.

Lianfu, G. (2002). Foreign Strategies of Northeast Asian Countries. Beijing, Social

Science Literature Press.

Miles Kahler, S. K. (2006). "Strategic Uses of Economic Interdependence:

Engagement Policies on the Korean Peninsula and across the Taiwan

Strait." Journal of Peace Research 43(5): 523-541.

Mitrany, D. (1966). A Working Peace System. Chicago, Quadrangle Books.

Myers, B. R. (2010). The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves

and Why It Matters. U.S.A., Melville House Publishing.

Nincic, M. (2013). "Carrots, Sticks and Domestic Politics." Global Asia 8(2): 14-19.

Park, C. J. (2013). Crossing the Border: South Korean Tourism to Mount

41

Geumgang. De-bordering Korea: Tangible and Intangible Legacies of the

Sunshine Policy. K. D. C. Valerie Gelezeau, Alain Delissen. New York,

Routledge.

Park, M.-l. (2000). Pyonghwawa Tongilulwihan Taeangwa Sontaekui Mosaek (A

Search for Alternatives and Choices for Peace and Unification). 21segi

Nambukgwangyeron (Inter-Korean Relations in the 21st Century). K. A. o.

P. Studies. Seoul, Pommunsa.

Qin, Z. (2010). "Game of Boundary Powers on the Cross Recognition Issue of Two

Koreas." Journal of Eastern Liaoning University (Social Science) 12(2):

131-139.

Samuel S. Kim, M. S. W. (2004). Inter-Korean Economic Relations. Inter-Korean

Relations: Problems and Prospects. S. S. Kim. New York, Palgrave

Macmillan.

Sanghun, C. (2010). South Korea Cuts Trade Ties with North over Sinking. The

Age. Melbourne.

Schelling, T. (1966). Arms and Influence. New Hadven, Yale University Press.

Snyder, S. (2004). Chapter Two: Inter-Korean Relations: A South Korean

Perspectives. Inter-Korean Relations: Problems and Prospects. S. S. Kim.

New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Stephan Haggard, M. N. (2011). Engaging North Korea: The Role of Economic

Statecraft. Honolulu, The East-West Center.

Stuart J. Thomson, H.-j. S. (2013). "From Adversaries to Partners: Academic

Science Engagement with North Korea." Global Asia 8(2): 43-47.

Suchman, M. (1995). "Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional

Approaches." Academy of Management Review 20: 571-597.

Valerie Gelezeau, K. D. C., Alain Delissen (2013). De-bordering Korea: Tangible

and Intangible Legacies of the Sunshine Policy. New York, Routledge.

Walter C. Clemens, J. (2013). "Hubrcs Versus Grct: Put Pride Aside and Help

Korea Find Peace." Global Asia 8(2): 20-26.

Yong-rok, K. (2000). Hangukgwa Haetpyotjongchaek (South Korea and the

Sunshine Policy). Seoul, Pommunsa.

Young-nok Koo, D.-s. S. (1984). Korea and the United States: A Century of

Cooperation. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press.

Yuxin, W. (1992). Autobiography of President Roh Tae-woo. Beijing, Social

Science Literature Press.

42

References:

http://eng.unikorea.go.kr/CmsWeb/viewPage.req?idx=PG0000000541

. (1970, August 15). Dong-A Il Bo (East Asian Daily).

Collection of President Park's Speeches. (1971). (Vol. II). Seoul: President's Secretary Office

of the Blue House.

Collection of President Park's Speeches. (1971). (Vol. X). Seoul: President's Secretary Office

of the Blue House.

Defense Technology Survey. (1995, June 10). Economist

. (2005, October 22). Dong-A Il Bo.

The Economic and Foreign Policy of Lee Myung-bak. (2008, March 1). Wen-Wei Po. Retrieved

from http://paper.wenweipo.com/2008/03/01/WW0803010005.htm

North Korea Announces to Establish Mountain Geumgang International Special Tourism Zone,

To Encourage Free Investmen. (2011, April 29). Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved from

http://news.qq.com/a/20110429/000891.htm