Efficacy of Interventions Promoting Blood Donation: A Systematic Review

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Efficacy of Interventions Promoting Blood Donation: A Systematic Review

Efficacy of Interventions Promoting Blood Donation:A Systematic Review

Gaston Godin, Lydi-Anne Vézina-Im, Ariane Bélanger-Gravel, and Steve Amireault

Findings about the efficacy of interventions promotingblood donation are scattered and sometime incon-sistent. The aim of the present systematic reviewwas to identify the most effective types of interven-tions and modes of delivery to increase blooddonation. The following databases were investigated:MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, andProquest Dissertations and Theses. Additional studieswere also included by checking the references of thearticles included in the review and by looking at ourpersonal collection. The outcomes of interest wereeither blood drive attendance or blood donations. Atotal of 29 randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies were included in the review,

From the Canada Research Chair on Behaviour and Health,Laval University, Québec, Canada; Faculty of Nursing, LavalUniversity, Québec, Canada; and Department of Social andPreventive Medicine, Laval University, Québec, Canada.The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.Address reprint requests to Gaston Godin, PhD, Canada

Research Chair on Behaviour and Health, Laval University,Québec, Canada G1V 0A6.E-mail: [email protected]/$ - see front matter© 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.10.001

Transfusion224

detailing 36 interventions tested among independentsamples. Interventions targeting psychosocial cogni-tions (s = 8, s to represent the number ofindependent samples; odds ratio [OR], 2.47; 95%confidence interval [CI], 1.42-4.28), those stressingthe altruistic motives to give blood (s = 4; OR, 3.89;95% CI, 1.03-14.76), and reminders (s = 7; OR,1.91; 95% CI, 1.22-2.99) were the most successfulin increasing blood donation. The results suggest thatmotivational interventions and reminders are the mosteffective in increasing blood donation, but additionalstudies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of othertypes of interventions.© 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

B LOOD AGENCIES ARE investing mucheffort to recruit new blood donors and to

ensure that those who have donated return foradditional donations. This preoccupation is well-founded given that, according to the American RedCross, only 3% of the population gives blood [1].To further complicate matters, blood donation is acyclic process in which once an individual hasdonated blood, he/she must wait a certain time (eg,56 days) before being eligible to give blood again[2]. Moreover, many medical and nonmedicalreasons such as foreign traveling can preventsomeone from successfully giving blood [2]. Thisis done to ensure donor and recipient safety [3].Effective interventions to retain blood donors andrecruit new donors are thus imperative to maintain asafe and sufficient level of blood supply.In a previous review on the motives and the

characteristics of blood donors, Piliavin [4] madean inventory of potential successful approaches toincrease blood donation, particularly among first-

time donors. For instance, this author suggested thatan increase in the perception for the need of bloodin the community and in the perception of theadequate support for blood donation provided inthese communities as well as the use of modelingwere promising approaches to increase blooddonation. The author also observed that face-to-face solicitations, the use of personal reminders,and the foot-in-the-door technique (consisting of asmall request followed by a bigger one) appeared tobe effective techniques to motivate individualsto give blood, given that individuals are sensitive tosocial pressure. These observations were alsosupported in a more recent review by Fergusonet al [5], in which the use of reminders and the foot-in-the-door technique were mentioned as effectivestrategies to favor blood donation.

Mixed evidences were observed concerning theefficacy of interventions aimed at increasingaltruistic motives vs the use of different forms ofincentives [4]. However, as pointed out earlier byPiliavin [4], the use of incentives might underminethe development of an altruistic motivation andprovoke a backfire effect on future donationsamong active blood donors. Moreover, in a recentreview of the literature among active blood donors,Ringwald et al [6] mentioned that the use ofincentives might not be the best strategy to keeplong-term and committed blood donors given thatas a donor advances in his/her career, his/hermotives for giving blood become more internalized.The role of altruism also needs some consideration.According to a deeper analysis by Ferguson et al [5]

Medicine Reviews, Vol 26, No 3 (July), 2012: pp 224-237.e6

1Other classifications can be found in the scientific literature(eg, Ferguson and Bibby (2002): occasional, b5 donations;regular, ≥5 donations).

225INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

of previous studies aimed at promoting blooddonation with the use of the altruism concept,results seem to provide more support for the use ofthe moral norm concept or the benevolenceresponse rather than pure altruism. Consequently,the role of altruism in the promotion of blooddonation has to be more clearly defined to furtherincrease the efficacy of such interventions.

Bednall and Bove [7] also did a review of self-reported motivators and deterrents of blood dona-tion. In particular, they verified that the motivesbehind blood donation differed among differenttypes of donors (first-time, repeat, lapsed, aphere-sis, and eligible nondonors). They concluded that,among first-time and repeat donors, the mostcommon motivators were convenience (eg, blooddrive nearby), prosocial motivation (eg, altruism),and personal values (eg, moral norm). They alsoidentified several deterrents among which the mostfrequently mentioned barrier was low self-efficacyto donate (eg, ability to overcome barriers such aslack of time).

Notwithstanding the very useful informationprovided by these previous reviews concerningthe potential efficacy of different strategies toincrease blood donation, none of them systemati-cally reviewed the literature and provided infor-mation on the effect sizes of such approaches. Inaddition, in the review by Ferguson et al [5],studies whose outcome was the intention orwillingness to give blood were also included intheir narrative analysis. Acknowledging the scien-tific evidence that intention is identified as one ofthe most important determinants of blood donation[2], it is, nonetheless, well documented that not allpeople will act on their stated intention, that is thereis an “intention-behavior gap” [8]. Moreover, in areview by Webb and Sheeran [9] on the effective-ness of interventions to promote health-relatedbehaviors, it was observed that a medium-to-largeeffect size in increasing levels of intention leads toa small-to-medium effect in changing behaviors.Consequently, the efficacy of interventions onblood donation and not only intention or willing-ness has to be determined.

To our knowledge, there is no systematic reviewon the efficacy of interventions to promote blooddonation. Thus, the objective of the presentsystematic review was to identify the most effectivetypes of interventions and their modes of delivery toincrease blood donation.

METHODS

Study Eligibility Criteria

The focus of the present systematic review wason interventions aimed at increasing blood donationamong the general population (ie, recruitmentstudies) and blood donors (ie, retention studies).Studies aimed at increasing different or specifictypes of donations such as bone marrow donation orapheresis were not included in the present review.To evaluate the efficacy of interventions, onlyexperimental and quasi-experimental studies wereincluded in the review; studies adopting a 1-grouppre-post design were excluded.

Studies concerned with different stages in thelifetime experience of blood donors, that is, novice,experienced, lapsed, or temporarily deferred donors,were included. According to Masser [10], indivi-duals who already gave blood once were consideredas novice donors (also referred to as first-timedonors), and individuals who already gave bloodmore than once were considered as experienceddonors (also referred to as repeat donors)1. Studiesinterested in lapsed donors (ie, individuals whoalready gave blood in the past but who did notdonate blood in the past 2 years without any knowncause for permanent or temporary deferral [11]) ortemporarily deferred donors (ie, individuals whoattended a blood center but were not eligible todonate blood for a certain period because of variousmedical reasons [12]) were also considered in thepresent systematic review.

Studies reporting results on the attendance at ablood drive or the number of successful blooddonations after the exposure to an intervention wereboth included in the present systematic review.Attendancewas defined as the number of participantswho registered at a blood drive. This outcome waschosen given that although some individuals can bedeferred for various medical reasons, attendancetakes into account the fact that participants had actedtoward their goal of giving blood after the exposureto the intervention [13,14]. To avoid duplication ofthe results, attendance was primarily used in thestatistical analyses in cases where attendance and thenumber of actual blood donationswere both providedin a given study. Studies reporting the results of an

226 GODIN ET AL

intervention on the level of intention orwillingness aswell as studies reporting results in terms ofphysiologic reaction, stress, and symptoms relatedto blood donation were excluded from the presentsystematic review.

Search Strategy

The following databases were investigated:MEDLINE/PubMed (1950+), PsycINFO (1806+),CINAHL (1982+), and EMBASE (1974+). Pro-quest Dissertations and Theses (1861+) was alsoinvestigated for gray literature (ie, unpublishedtrials). No restriction was placed on the year ofpublication of the articles. The search wasperformed between June 8 and July 31, 2010. Inall the databases, the search terms were alwaysrelated to 2 themes, that is, blood donation andintervention (see Table 1). In MEDLINE/PubMed,a combination of keywords and MeSH terms wasused. In PsycINFO, only keywords were usedbecause no psychological index terms corre-sponded to blood donation and intervention. InCINAHL, a combination of keywords and de-scriptors was used. In EMBASE, a combination ofkeywords and Emtree terms was used. Finally, inProquest Dissertations and Theses, only keywordswere used. The search was limited to studiespublished in English. Additional studies were alsoincluded by checking the references of the articlesincluded in the systematic review (ie, secondaryreferences) as well as by looking at our personalcollection of articles on blood donation.

Data Extraction

Data were independently extracted by GG andLAVI using a standardized data extraction form (seeTable 2). Disagreements were resolved by discus-sion. Before extracting the data, several decisionswere made. First, in instances where there was morethan 1 experimental group in a study, only the groupthat had the greatest impact on blood donation was

Table 1. Search Terms Used for Investigating All 5 Databases

Keywords

Theme 1: blood donation Blood donation ORBlood donor ORBlood bank

Theme 2: intervention Intervention ORProgram OREducation

considered and compared with the control group.This decisionwas taken given that themain objectiveof the present review was to verify which types ofintervention were more successful in increasingblood donation and also because this group corre-sponded to the hypothesis stated in the articlesincluded in the meta-analysis in 90% of the cases.Second, when several tests of an intervention wereperformed among independent samples but reportedin 1 article, these were all included in the analysis (ie,studies 1 and 2). Consequently, the number ofindependent comparisons in the meta-analysis mightbe more important than the number of includedstudies in some of the subgroup analyses. Finally,authors were personally contacted by e-mail foradditional information when necessary.

Interventions were classified according to anadapted version of the categorization proposed in arecent review by Ferguson et al [5] (see Table 3).These authors regrouped the social interventionsinto 4 types: (1) altruism-egoism, (2) reminders andcommitments, (3) foot-in-the-door, and (4) inten-tion based. Social interventions were aimed atincreasing blood donation and were mainly focusedon recruitment. They also identified behavioralinterventions that can be classified in 3 categories:(5) distraction, (6) muscle tension, and (7) caffeineand water loading. These behavioral interventionsare primarily aimed at reducing unpleasant symp-toms associated with blood donation and mainlyfocused on retention of donors.

The first category of social interventionsincluded interventions that use manipulations ofaltruism and egoism to encourage blood donation.In the present review, however, the interventionsbased on altruism were imbedded in a largermotivational category that included all the in-terventions aimed at increasing motivation towardblood donation. These studies used techniquessuch as providing information about positive ornegative consequences of blood donation, barriersmanagement, modeling, comparison with thesocial norm, providing feedback and praise, andother. However, given the importance of theconcept of altruism in the literature on blooddonation, the independent efficacy of interven-tions based on altruism was compared with theefficacy of other motivational interventions in thesubgroup analyses. The second category includedinterventions generally focusing on retention thatuse a reminder, such as a telephone call, before

Table 2. Information Contained in the Data Extraction Form

Type of information Subcategory

Main objective of the study Recruit new donorsEncourage donors to returnBoth objectivesUnspecified

Population of the study Potential donors/general populationNovice donorsExperienced donorsUnspecified

Study design Randomized, controlled trialQuasi-experimental design

Group allocation Type of assignmentStrategy used for assignmentTechnique used for assignmentPerson who performed assignmentType of control group

Type of intervention MotivationalRemindersMeasurement of cognitionsIncentivesMuscle tension

Mode of delivery Face-to-faceBy mail (eg, letter)By telephone (eg, telephone call prompt)By e-mailBy tape recorderMix

Use of a theory YesNo

Behavior measured Registrations at a blood driveBlood donationsBoth

Behavioral measure Type of behavioral measureValidation of the measure

Sample SizeAttrition at postinterventionAttrition at follow-upCharacteristics of participants at baselineEquivalence of groups at baselineDropout analysis

Statistical analyses Statistical test usedIntention to treatCovariatesTechnique to replace missing data

Results of the intervention Percentage of participants who registered at a blood drivePercentage of participants who gave bloodOther

227INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

the blood drive takes place. The third categorywas the foot-in-the-door [15] or door-in-the-face[16] interventions that are well-known techniquesissued from the social psychology literature. Thelast category, that is, the intention-based category,initially included interventions that manipulatedintentions. Given that the intention-based categorywas too specific to the measurement of intention,

a new category was created (ie, measurement ofcognitions or the question-behavior effect) toinclude all studies that measured cognitions withthe specific objective of promoting blood dona-tion. Finally, the use of incentives (financial ornot) was added as a separate category, and thebehavioral categories were classified using thedescription provided by Ferguson et al [5]. All of

Table 3. Classification of the Interventions Based on the Categorization of Ferguson et al [5]

Type of intervention Definition

Motivational Interventions aimed at increasing motivation toward blood donationCognitions based Interventions targeting psychosocial cognitions related to motivation,

such as social norms, attitudes, and barriersFoot-in-the-door/door-in-the-face Interventions using the foot-in-the-door, the door-in-the-face,

or a combination of both techniques to motivate people to give bloodFoot-in-the-door involves asking a small request that should be accepted

and then asking a critical large request. Door-in-the-face involvesasking a large request that should be refused

and then asking a critical small request.Altruism Interventions using altruistic motives to motivate people to give bloodModeling Interventions showing another person giving blood to motivate

people to give bloodReminders Interventions using reminders about the next eligibility date and/or the next

appointment to give blood (eg, telephone call prompt)Measurement of cognitions Interventions using the completion of a questionnaire about the intention to give

blood to activate cognitions about blood donation (eg, question-behavior effectIncentives Interventions using incentives for donating blood such as a T-shirt, money,

prizes, tickets, and otherMuscle tension Interventions using the contraction of muscles during blood donation to avoid

dizziness and fainting

228 GODIN ET AL

the interventions were independently classifiedaccording to their type by LAVI and ABG,and disagreements were resolved by a thirdreviewer (GG).

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics of the studies, such asfrequencies and means, was analyzed using SASversion 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All the otherstatistical analyses were done using Cochrane'sReviewManager 5.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Center,Copenhagen, Denmark) [17] statistical software. Tocompute pooled effect sizes, a random-effect modelusing the Mantel-Haenszel method was chosen forall the analyses because we assumed that themagnitude of the effect sizes would vary acrossstudies given the difference in samples and in-terventions across studies [18].When computing thepooled effect size, each study was weightedaccording to its sample size. Between-study hetero-geneity was verified by using 2 common statisticalapproaches: a χ2 test (Cochran's Q) and the I2

statistic [19], representing the percentage of totalvariation in estimated effects that is due toheterogeneity rather than chance. A significant Qstatistic (P b .05) indicates significant heterogeneitybetween the studies, whereas an I2 statistic of 25% isconsidered low heterogeneity; 50%, moderateheterogeneity; and 75%, high heterogeneity [20].To test the robustness of the results, separate 80%

)

prediction intervals (PIs) were calculated for eachpooled effect size (see Supplementary file 1 onlinefor the formula used). The computation of PIs isrecommended when confronted with a random-effect meta-analysis that has a low number of studiesand high heterogeneity [21]. Prediction intervalsshow the distribution of effect sizes around thepooled effect size. The effect sizes of interventionstudies were reported as odds ratios (ORs) given thatmost of the outcomes were reported as dichotomousdata (ie, the proportion of attendance or blooddonation in the experimental group compared withthe control group). Unless otherwise stated, all effectsizes are zero order (ie, no covariates are included inthe computation of the effect size). The ORs werealso converted to Cohen's d [22] to facilitateinterpretation and allow comparison with standardeffect sizes reported in other studies. A Cohen's d of0.20 is considered a small effect size; 0.50, amedium effect size; and 0.80, a large effect size [22].The efficacy of the interventions according to typeof intervention and mode of delivery was alsoexamined by means of prespecified subgroupanalyses. However, pooled effect sizes were com-puted only when the category contained results froma minimum of 3 independent samples. Finally,publication bias was assessed by visually inspectingthe distribution of the funnel plot in RevMan 5.1(The Nordic Cochrane Center) in instances wherethere were about 10 studies per category [23].

229INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

RESULTS

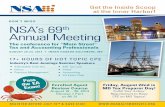

The results of the search strategy are presentedin Figure 1 [24]. A total of 29 studies (k = 29)were included in the present review, detailing 36different interventions tested among independentsamples (s = 36). In the rest of the text, the letterk will be used to represent the number of studies,and the letter s to represent the number ofindependent samples.

Characteristics of the Interventions

A summary of the interventions is given inSupplementary file 2. When no effect sizes could be

Fig 1. Preferred reporting for systematic rev

calculated because of missing information such asthe number of participants per condition, the origi-nal results are reported. Most interventions wereaimed at retaining current donors (s = 12) or bothrecruiting new donors and retaining donors (s = 8).One intervention had the objective to recruit newdonors. In 15 interventions, the objective did notclearly specify if it was more about recruiting orretaining blood donors or vice versa. Again, fewstudies clearly specified the type of donors targetedby the intervention; only 6 studies mentioned thisinformation (novice donors, s = 5; experienceddonors, s = 1). Given that more than 3 studies weretargeting novice donors, a pooled effect size was

iews and meta-analyses flowchart [24].

230 GODIN ET AL

calculated (s = 5; OR, 1.21; 95% confidenceinterval [CI], 1.10-1.32; Q = 1.68; P = .80; I2 =0%); it represented a small effect size (d = 0.11). Nosignificant heterogeneity between the studies wasdetected. Unfortunately, given the low number ofstudies, no pooled effect sizes could be calculatedfor other types of donors, such as experienced,lapsed, and deferred donors.Of the 36 interventions included in the review,

24 were randomized controlled trials, althoughmost of them (s = 16) did not provide informationon the randomization procedure. The other 12interventions either adopted a quasi-experimentaldesign (s = 3) or did not provide informationabout the design adopted (s = 9). Although itwould have been interesting to compare thedifference in effect sizes between both pure andquasi-experimental studies, 2 problems arose: (1)many studies did not specify their study design(s = 9) and (2) older studies tended to have littleinformation about their randomization procedurecompared with more recent studies; this phenom-enon could reflect different editorial requirementsthrough the years.Twenty-one interventions were clearly based

on a theory. The theories most frequently used todesign interventions promoting blood donationswere the self-perception theory [25] (s = 4), thesocial learning/social cognitive theory [26,27](s = 4), the theory of reasoned action [28] andits extension, the theory of planned behavior [29]

Table 4. Pooled Effect Size

Variable s n

Type of interventionMotivational 20 37 102 2Cognitions based 8 23 198 2Foot-in-the door/door-in-the-face 6 1303 1Altruism 4 7619 3Reminders 7 286 615 1Measurement of cognitions 3 6812 1

Mode of deliveryFace-to-face 5 239 2Mail 4 5536 1Telephone 10 287 882 2Mix of modes 10 15 896 1

NOTE. I2 is an indicator of heterogeneity. Twenty-five percent is cons

high heterogeneity.⁎ P b .05, significant heterogeneity (Q statistic).† P b .01, significant heterogeneity (Q statistic).‡ P b .001, significant heterogeneity (Q statistic).

(s = 4), and Schwartz's norm activation theory[30] (s = 2).

Characteristics of the Participants

Only 12 studies provided information on theage of their participants. The mean age of theparticipants was 25.72 ± 8.61 years (range,18-44.3 years). Eighteen interventions wereconducted among samples of college students,and 3 others, among samples of high schoolstudents. Seventeen interventions indicated thepercentage of male participants in their sample.A little less than half (44.8%) of the sampleswere composed of male respondents. Threeinterventions mentioned having samples contain-ing participants of both sexes without specifyingthe percentage of male respondents. One inter-vention had a sample exclusively of femaleparticipants. The typical sample was thus com-posed of college students with slightly more thanhalf being female students.

Efficacy of the Interventions

A summary of the pooled effect sizes computed,their heterogeneity, and their robustness is pre-sented in Table 4. Where exact information aboutnumbers of participants or effect sizes weremissing [31-35], we attempted to obtain therelevant information directly from the authors. In3 cases [33-35], we were unable to obtain thisinformation. Thus, of the 29 studies describing 36

s, OR with 95% CIs

OR (95% CI) Q I2 (80% PI)

.09 (1.64-2.67) 117.21 ‡ 84% (1.23-3.53)

.47 (1.42-4.28) 42.18 ‡ 83% (0.88-6.97)

.86 (1.02-3.39) 12.72 ⁎ 61% (0.74-4.69)

.89 (1.03-14.76) 51.43 ‡ 94% (0.30-50.96

.91 (1.22-2.99) 19.71 † 70% (0.91-4.01)

.23 (1.06-1.41) 3.01 34% (0.85-1.79)

.57 (1.29-5.11) 5.14 22% (1.11-5.95)

.25 (1.12-1.40) 2.49 0% (0.89-1.76)

.41 (1.38-4.20) 84.50 ‡ 89% (0.77-7.50)

.60 (1.27-2.00) 40.23 ‡ 78% (1.07-2.39)

idered low heterogeneity; 50%, moderate heterogeneity; and 75%

)

,

231INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

interventions, 26 studies describing 33 interven-tions among independent samples could beincluded in the meta-analysis.

Motivational Interventions

Twenty-two interventions [32,33,36-50] wereclassified in the motivational category. However,2 interventions [33,48] did not report the number ofparticipants in their samples and were thus excludedfrom the meta-analysis. The study of Evans [33]reported nonsignificant results (P = .67), whereasthe study of Sarason et al [48] had significant results(P b .01). The pooled effect size (s = 20) indicatedthat motivational interventions were successful inincreasing blood drive attendance, and this repre-sented a small-to-medium effect size (d = 0.41).Significant heterogeneity between the studies wasdetected, which justified subgroup analyses. The80% PI indicated, however, that the significantresult was robust.

Cognitions-Based Interventions

Nine interventions [32,33,36,38,41,43,44] wereclassified as cognitions based because they weretargeting psychosocial cognitions related to moti-vation, such as social norms, attitudes, and barriers.However, 1 intervention [33] could not be enteredin the meta-analysis because it did provide thenumber of participants per condition (ie, in theexperimental and control groups). This studyreported nonsignificant results (P = .67). Thepooled effect size (s = 8) indicated that cogni-tions-based interventions were successful in in-creasing attendance at blood drives, and thisrepresented a medium effect size (d = 0.50).Significant heterogeneity was detected, and exam-ination of the 80% PI indicated that the resultshould be interpreted carefully. Moreover, theexamination of the funnel plot (see Supplementaryfile 3 online) indicated that there is probably apublication bias [23].

Foot-in-the-Door and Door-in-the-FaceTechniques

A total of 6 interventions [37,40,42,46] were usingthe foot-in-the-door, the door-in-the-face, or acombination of both techniques to encourage peopleto give blood. The pooled effect size (s = 6) indicatedthat these types of interventions were successful atincreasing attendance at blood drives. When thepooled OR was converted to Cohen's d [22], it

represented a small-to-medium effect size (d = 0.34).The Q statistic indicated that there was significantheterogeneity between the studies, although the I2

statistic was still below 75%. The 80% PI indicatedthat the result is not very robust.

Altruism

Four interventions [39,45,50] aimed to increaseblood donation by stressing the altruistic reasons togive blood. The pooled effect size (s = 4) revealedthat this kind of intervention was successful inincreasing blood drive attendance; this representeda medium-to-large effect size (d = 0.75). Significantheterogeneity between the studies was detected,and the 80% PI was very large, which indicates thatthe result is not robust at all.

Modeling

Three interventions [47-49] were using model-ing, such as showing a model giving blood, toincrease blood donations. However, 1 study [48]did not report the exact number of participants intheir experimental and control groups. This studyby Sarason et al [48] reported that their interven-tion had significant results (P b .01). Given thatonly 2 studies could have been entered in a meta-analysis, no pooled effect size was computed forthis type of intervention. Examination of theindividual effect sizes of the studies indicated thatall the studies reported significant results (Rushtonand Campbell [47]: OR, 39.67; 95% CI, 1.28-1229.87; and Sarason et al [49]: OR, 1.25; 95% CI,1.06-1.47). Additional studies will be neededbefore any effect size can be computed about theefficacy of interventions that use modeling toincrease blood donation.

Reminders

Seven interventions [51-55] were using re-minders, such as telephone call prompts, as ameans to increase blood donations. The pooledeffect size (s = 7) for this type of interventionindicated that they were successful in increasingattendance at blood drives, and this represented asmall-to-medium effect size (d = 0.36). Significantheterogeneity between the studies was detected,and the 80% PI was close to significance, whichindicates that the result is somewhat robust. Theinspection of the funnel plot (see Supplementaryfile 4 online) indicated the likely presence of apublication bias [23].

232 GODIN ET AL

Measurement of Cognitions

Three interventions [13,56,57] used answeringquestions about cognitions related to blood dona-tion to increase this behavior. One study [57]reported a continuous outcome (ie, mean number ofblood donations), which allowed the calculation ofa standard mean difference (SMD). This SMD wasthen converted to an OR to pool it with the rest ofthe studies (see Supplementary file 5 online for theformula used). The pooled effect size (s = 3)indicated that interventions using the measurementof cognitions are effective in increasing blooddonation and that no significant heterogeneity wasdetected. Once converted to Cohen's d, the pooledeffect size represented a small effect size (d = 0.11).The 80% PI, however, indicated that the resultshould be interpreted carefully.

Incentives

Two interventions [34,58] used incentives, suchas tickets to a Broadway play and a college footballgame, gift certificates, prizes, free meals, and other,to increase blood donation. One intervention [34]did not report the exact number of study partici-pants but stated that the intervention was successfulin increasing blood drive attendance (P b .01). Theother study by Ferrari et al [58] also had significantresults (OR, 3.86; 95% CI, 1.47-10.13). The lownumber of studies using incentives and the fact thatonly 1 study reported the information necessary tocompute an effect size precluded any meta-analysis.Additional studies will be needed to verify theaccuracy of the present finding and before anydefinite conclusion can be reached about theefficacy of incentives to increase blood donation.

Muscle Tension

Two interventions [31,59] used muscle tensionto decrease negative symptoms associated toblood donation such as dizziness and fainting toincrease blood donors return. Given the lownumber of studies using this technique, no effectsize was computed. Examination of the individualeffect sizes indicated that both studies hadnonsignificant results (Ditto et al [59]: OR,1.48; 95% CI, 0.95-2.30; and Ditto et al [31]:OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.82-1.66). Additional studieswill be needed to verify the definite efficacy ofmuscle tension on blood donation.

Modes of Delivery

The efficacy of interventions according to theirmode of delivery was also evaluated. In 1intervention [41], a brochure was used to contactparticipants, but it was not specified if it was sent bymail or if it was given in person, thereby making itimpossible to classify its mode of delivery.

Face-to-Face

A total of 6 interventions [34,37,40,43,47,58]were delivered face-to-face. However, 1 study [34]did not report the exact number of participants intheir intervention but still presented significantresults (P b .01). The pooled effect size was thuscomputed on 5 studies, and it indicated thatinterventions delivered face-to-face are effective inincreasing attendance at blood drives. Thisrepresented a medium effect size (d = 0.52). Nosignificant heterogeneity between the studies wasdetected, and the 80% PI indicated that the resultis robust.

Four interventions [13,46,53] were delivered bymail, such as the mailing of a brochure, a letter, or aquestionnaire. The pooled effect size (s = 4)indicated that interventions using this mode ofdelivery were effective in increasing blood driveattendance, and this represented a small effect size(d = 0.12). No heterogeneity between the studieswas detected, and the 80% PI was close tosignificance, which indicates that the result issomewhat robust.

Telephone

A total of 11 interventions [32,33,38,40,42,50-52,54,55] were delivered by telephone, such astelephone call prompts, making it the most commonmode of delivery. However, 1 study [33] did notreport the number of participants per condition andwas thus excluded from the meta-analysis. Thisstudy by Evans [33] reported that its interventiondid not significantly increase blood donation in theexperimental condition (P = .67). The pooled effectsize (s = 10) for interventions delivered bytelephone indicated that this mode of delivery waseffective in increasing blood drive registration, andthis value was very close to a medium effect size(d = 0.49). Significant heterogeneity was detected,and the 80% PI indicated that the results should be

233INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

interpreted carefully. In addition, the visual inspec-tion of the funnel plot (see Supplementary file 6online) indicated that there might be a publicationbias [23].

Tape Recorder

One study [39] that reported 2 interventionscarried out on 2 different samples mentioned usinga tape recorder to deliver the interventions. Giventhe low number of studies, no pooled effect size wascomputed. Examination of the individual effectsizes indicated that this mode of delivery iseffective in increasing blood drive attendance(Ferrari and Leippe [39], study 1: OR, 2.24; 95%CI, 0.36-13.78; study 2: OR, 22.14; 95% CI, 2.58-190.16). Additional studies are needed before adefinite conclusion about the efficacy of interven-tions delivered by tape recorder can be reached.

Only 1 study [56] mentioned the use of an e-mailto conduct its intervention. Examination of theeffect size indicated that this mode of delivery iseffective (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.04-5.73) andrepresents a small-to-medium effect size (d = 0.45).

Mix of Modes of Delivery

A total of 11 interventions [31,36,40,44,45,48,49,57,59] were using a combination of differentmodes of delivery, such as a letter delivered bymail and a telephone call or instructions givenface-to-face and a video presentation. However, 1study [48] did not provide the exact number ofparticipants in its experimental and control groupsand was thus excluded from the meta-analysis.This study by Sarason et al [48] reported asignificant difference in the number of blooddrive registrations between the experimental andthe control groups (P b .01). The pooled effectsize (n = 10) indicated that interventions using amix of different modes of delivery were success-ful in increasing attendance at blood drives. Thisrepresented a small-to-medium effect size (d =0.26). Significant heterogeneity was detected, butthe 80% PI indicated that the result is robust.

DISCUSSION

According to our review, the first studiesreporting interventions to increase blood donationwere published in the 1970s. Therefore, it is rathersurprising that more than 4 decades later, the

number of papers available in the scientific literatureis low (n = 29). When we look at the flowchart (seeFig 1), this phenomenon does not seem to originatefrom the fact that many interventions did not report abehavioral outcome (n = 25) or that studies adopteda 1-group pre-post design (n = 3) but, rather, that theliterature in blood donation has mainly focused onidentifying the motives of blood donors by means ofsurveys (n = 102).

Effective Interventions

Earlier reviews [5,60] also identified reminders,such as telephone call prompts to inform donors ofthe time, date, and location of blood drives, as aneffective means to increase blood donation. More-over, the results of a recent study conducted amongfirst-time donors indicated that a telephone callreminder about the upcoming opportunity to giveblood increases the number of donors who returnand that they also return more quickly comparedwith those not telephoned [61]. Telephone calls actas a “cue-to-action,” that is, they represent anenvironmental cue that is used to remind people toperform a given behavior [62].

In the present review, cognition-based interven-tions included all interventions targeting psychoso-cial constructs underlying motivation, such associal norms, attitudes, and barriers (for a completetaxonomy, see Michie et al [63]). The effectivenessof this type of intervention at increasing blooddonations provides further support to previousobservations that intention, a construct expressingones' motivation toward a given behavior, is one ofthe main determinants of blood donation [2,64].This observation is also in agreement with thetheory of planned behavior [29], a model thatalready has been successfully applied to predictblood donation [64-66].

Interventions based on altruism seemed to beeffective in encouraging people to give blood.However, this result should be interpreted carefullygiven that quantification of the efficacy proveddifficult. Earlier reviews [4,60] already noted thatmost donors cite altruistic motives as the mainreason to give blood. It was also suggested thatwomen and young people respond well to altruisticappeals [60]. Thus, given that most interventionswere offered at samples of college students withslightly more than half of these samples containingfemale students, this might explain the efficacy ofthis type of interventions. It remains to be

234 GODIN ET AL

documented if appeals to altruism are effectiveamong older male samples.In the present review, interventions using the

measurement of cognitions were also effective toincrease attendance at blood drives. The impact ofthis type of intervention on behavior is generallyconsidered as the question-behavior effect or themere-measurement effect. According to the ques-tion-behavior effect, asking questions on relevantcognitions can change behavior [67]. It was notsurprising that only 3 studies were identified in thatcategory given that the literature on the question-behavior effect is still in its infancy; only recentlyhas such an effect been observed in blood donation[13,57]. It will thus be important to obtainadditional information on the type of questionsthat provoke taking action as well as the potentialmoderators of this effect (eg, level of experiencewith blood donation).

Interventions Whose Efficacy Could NotBe Determined

Caution should be exercised before concludingthat offering incentives is an effective way toencourage blood donation because only 2 studiestested this approach, and no effect size could becomputed. It is also noteworthy that incentives weresometime used in combination with other interven-tion components (eg, altruistic motives to giveblood and T-shirt). Other reviews [4,60] haveindicated that there was little evidence that the useof incentives such as money, prizes, and similartokens were effective in increasing blood donation.There is even evidence that they may actuallydecrease donations by decreasing the altruisticmotives to give blood [5,60].In the present review, the foot-in-the-door and the

door-in-the-face techniques emerged as effectivemethods to increase blood donation, although theresult is not very robust. Piliavin [4] alreadyacknowledged that the use of these 2 techniqueswas yielding to inconsistent results. Ferguson et al[5] also noted that the foot-in-the-door techniqueappeared a more effective approach than the door-in-the-face technique. In the present study, we didnot compute an effect size for each of the 2techniques separately, given the small number ofstudies using only 1 of the 2 techniques. Nonethe-less, even if such techniques were found effective atincreasing blood donations, their use on a large scalecan be questioned for ethical or practical reasons.

Effective Modes of Delivery

The present review also quantitatively evaluatedwhich modes of delivery are most effective atincreasing blood donations. In this regard, 3 modesemerged as the most promising avenues to deliverinterventions on blood donation: face-to-face, bytelephone, and by mail. Previous reviews [4,60] hadhighlighted that face-to-face solicitation was ahighly effective recruitment technique that couldbe up to 4 times more effective than recruitment bytelephone. In the present meta-analysis, there was atrend suggesting that the more a mode of deliverywas personal, the more effective it was in increasingblood donation. However, given that face-to-facesolicitation is more time-consuming and moreexpensive [60], interventions delivered by tele-phone might be the most cost-efficient method.Finally, there is a lack of studies using newtechnologies; only 1 study [56] used an e-mail tocarry out its intervention. Therefore, it will beimportant in the future to document the potential ofusing e-mail, SMS, and other new technologies asnovel approaches to promote blood donation,especially among young blood donors.

Areas Where Additional Studies Are Needed

Unfortunately, very few interventions weredeveloped to target a specific type of donors (eg,novice donors, regular donors, etc). This is rathersurprising given that previous studies have clearlyshown that the motives for giving blood differbetween types of donors. For example, it has beenshown that the determinants of return to give bloodagain differ between novice and experienced donors[64] and current and lapsed donors [11]. This wouldsuggest that different interventions should bedeveloped for first-time, novice, experienced, andregular donors. Alas, the results of the presentreview that indicated that interventions amongnovice donors are effective could not be comparedwith those of other types of donors. Moreover, mostinterventions were carried out among samples ofcollege students, thereby making the results hard togeneralize to the general population.

The present review also revealed that someauthors omit important information when describ-ing their intervention. Authors should be required torefer to the Consolidated Standards for ReportingTrials (CONSORT) statement [68]. The CON-SORT statement comprises a 25-item checklist of

235INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

information authors should report in their random-ized controlled trials. The use of this checklistshould lead to more transparent reporting andfacilitate replication of the findings.

Another observation is that additional interven-tions based on modeling and muscle tension areneeded before a definite conclusion about theirefficacy can be reached. Modeling is a techniquegrounded in the social learning theory of Bandura[27]. It has already been successfully applied toencourage children to eat more fruits and vegetables[69] and to perform regular physical activity [70]. Itremains to be seen if this technique can be appliedin adult populations. In addition, behavioral in-terventions such as applied muscle tension are still anew type of interventions to reduce discomfort (eg,dizziness) associated with donating blood [59].Although the results obtained were nonsignificant,it could still be an interesting avenue for retainingdonors given that it can be implemented directly onsite during blood drives.

Limitations of the Systematic Review

The present review has some limitations thatare worth mentioning. First, the relatively smallnumber of studies prevented the computation ofsome comparisons and affected the robustness ofthe pooled effect sizes. Second, not all in-terventions could be included in the meta-analysis because they did not report the infor-mation needed to compute an effect size (ie, thenumber of participants in the experimental andthe control groups).

CONCLUSIONS

Finally, to our knowledge, this is the first study tosystematically review blood donation interventionsand to quantify their effect. As such, the presentreview contributes to improve current knowledge,to identify gaps in knowledge, and to suggest newdirections for future interventions aimed at promot-ing blood donation.

REFERENCES

[1] American Red Cross. Give Blood. 2011 [cited 2011 January12]; Available from: http://www.redcross.org/portal/site/en/uitem.mend8aaecf214c576bf971e4cfe43181aa0/?vgnextoid=d0061a53f1c37110VgnVCM1000003481a10aRCRD.

[2] Ferguson E. Predictors of future behaviour: a review ofthe psychological literature on blood donation. Br J HealthPsychol 1996;1:287-308.

[3] Linden JV, Gregorio DI, Kalish RI. An estimate of blooddonor eligibility in the general population. Vox Sang1988;54:96-100.

[4] Piliavin PA. Why do they give the gift of life? A review ofresearch on blood donors since 1977. Transfusion 1990;30:444-59.

[5] Ferguson E, France CR, Abraham C, Ditto B, Sheeran P.Improving blood donor recruitment and retention: integrat-ing theoretical advances from social and behavioral scienceresearch agendas. Transfusion 2007;47:1999-2010.

[6] Ringwald J, Zimmermann R, Eckstein R. Keys to open thedoor for blood donors to return. Transfus Med Rev2010;24:295-304.

[7] Bednall TC, Bove LL. Donating blood: a meta-analyticreview of self-reported motivators and deterrents. TransfusMed Rev 2011;25:317-34.

[8] Sheeran P. Intention-behavior relations: a conceptual andempirical review. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2002;2:1-36.

[9] Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentionsengender behavior change? A meta-analysis of theexperimental evidence. Psychol Bull 2006;132:249-68.

[10] Masser BM, White KM, Hyde MK, Terry DJ. Thepsychology of blood donation: current research and futuredirections. Transfus Med Rev 2008;22:215-33.

[11] Germain M, Glynn SA, Schreiber GB, Gelinas S, King M,Jones M, et al. Determinants of return behavior: a

comparison of current and lapsed donors. Transfusion2007;47:1862-70.

[12] Riley W, Schwei M, McCullough J. The United States'potential blood donor pool: estimating the prevalence ofdonor-exclusion factors on the pool of potential donors.Transfusion 2007;47:1180-8.

[13] Godin G, Sheeran P, Conner M, Germain M. Askingquestions changes behavior: mere measurement effects onfrequency of blood donation. Health Psychol 2008;27:179-84.

[14] James RC, Matthews DE. The donation cycle: a frameworkfor the measurement and analysis of blood donor returnbehaviour. Vox Sang 1993;64:37-42.

[15] Freedman JL, Fraser SC. Compliance without pressure: thefoot-in-the-door technique. J Pers Soc Psychol 1966;14:195-202.

[16] Cialdini RB, Vincent JE, Lewis SK, Catalan J, Wheeler D,Darby BL. Reciprocal concessions procedure for inducingcompliance: the door-in-the-face technique. J Pers SocPsychol 1975;31:206-15.

[17] ReviewManager (RevMan) 5.1 ed. Copenhagen: TheNordicCochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008.

[18] Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR.Introduction to meta-analysis. Chippenham: John Wiley &Sons; 2009.

[19] Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in ameta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-58.

[20] Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG.Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60.

[21] Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. Are-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R StatistSoc 2009;172:137-59.

236 GODIN ET AL

[22] Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155-9.[23] Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie RL, Abrams KR, Jones DR.

Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. BMJ 2000;320:1574-7.

[24] Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferredreporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264-9.

[25] Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. Adv Exp Soc Psychol1972;6:1-62.

[26] Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory ofbehavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191-215.

[27] Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall: Engle-wood Cliff; 1977.

[28] Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention andbehavior: an introduction to theory of research. DonMills: Addison-Wesley; 1975.

[29] Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ BehavHum Decis Process 1991;50:179-211.

[30] Schwartz SH. Normative influences on altruism. Adv ExpSoc Psychol 1977;10:221-79.

[31] Ditto B, France CR, Holly C. Applied tension may helpretain donors who are ambivalent about needles. Vox Sang2010;98:e225-30.

[32] Sinclair KS, Campbell TS, Carey PM, Langevin E, BowserB, France CR. An adapted postdonation motivationalinterview enhances blood donor retention. Transfusion2010;50:1178-786.

[33] Evans DE. Development of intrinsic motivation forvoluntary blood donation among first-time donors [Ph.D.].Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin –Madison; 1981.

[34] Jason LA, Jackson K, Obradovic JL. Behavioral ap-proaches in increasing blood donations. Eval Health Prof1986;9:439-48.

[35] Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR, Shearin EN. A sociallearning approach to increasing blood donations. J ApplSoc Psychol 1991;21:896-918.

[36] Chamla JH, Leland LS, Walsh K. Eliciting repeat blooddonations: tell early career donors why their blood type isspecial and more will give again. Vox Sang 2006;90:302-7.

[37] Cialdini RB, Ascani K. Test of a concession procedurefor inducing verbal, behavioral, and further compliancewith a request to give blood. J Appl Psychol 1976;61:295-300.

[38] Clee MA, Henion KE. Blood donorship and psychologicalreactance. Transfusion 1979;19:463-6.

[39] Ferrari JR, Leippe MR. Noncompliance with persuasiveappeals for a prosocial, altruistic act: blood donating. J ApplSoc Psychol 1992;22:83-101.

[40] Foss RD, Dempsey CB. Blood donation and the foot-in-the-door technique: a limiting case. J Pers Soc Psychol1979;37:580-90.

[41] Gimble JG, Kline L, Makris N, Muenz LR, Friedman LI.Effects of new brochures on blood donor recruitment andretention. Transfusion 1994;34:586-91.

[42] Hayes TJ, Dwyer FR,Greenwalt TJ, CoeNA.A comparisonof two behavioral influence techniques for improving blooddonor recruitment. Transfusion 1984;24:399-403.

[43] Jason LA, Rose T, Ferrari JR, Barone R. Personal versusimpersonal methods for recruiting blood donations. J SocPsychol 1984;123:139-40.

[44] LaTour SA, Manrai AJ. Interactive impact of informationaland normative influence on donations. J Mark Res 1989;26:327-35.

[45] Reich P, Roberts P, Laabs N, Chinn A, McEvoy P,Hirschler N, et al. A randomized trial of blood donorrecruitment strategies. Transfusion 2006;46:1090-6.

[46] Royse D. Exploring ways to retain first-time volunteerblood donors. Res Soc Work Pract 1999;9:76-85.

[47] Rushton J, Campbell A. Modelling, vicarious reinforcementand extraversion and blood donating in adults: immediate andlong-term effects. Eur J Soc Psychol 1977;7:297-306.

[48] Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR, Shearin EN, SayersMH. A social learning approach to increasing blooddonations. J Appl Soc Psychol 1991;21:896-918.

[49] Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR, Sayers MH,Rosenkranz SL. Promotion of high school blood donations:testing the efficacy of a videotaped intervention. Transfu-sion 1992;32:818-23.

[50] Upton WE. Altruism, attribution, and intrinsic motivationin the recruitment of blood donors [Ph.D.]. New York, NY:Cornell University; 1973.

[51] Ferrari JR, Barone RC, Jason LA, Rose T. The effects of apersonal phone call prompt on blood donor commitment.J Community Psychol 1985;13:295-8.

[52] Lipsitz A, Kallmeyer K, Ferguson M, Abas A. Counting onblood donors: increasing the impact of reminder calls.J Appl Soc Psychol 1989;19:1057-67.

[53] Pittman TS, Pallak MS, Riggs JM, Gotay CC. Increasingblood donor pledge fulfillment. Pers Soc Psychol Bull1981;7:195-200.

[54] Whitney JG, Hall RF. Using an integrated automatedsystem to optimize retention and increase frequency ofblood donations. Transfusion 2010;50:1618-24.

[55] Wiesenthal DL, Spindel L. The effect of telephonemessages/prompts on return rates of first-time blooddonors. J Community Psychol 1989;17:194-7.

[56] Cioffi D, Garner R. The effect of response options ondecisions and subsequent behavior: sometimes inaction isbetter. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 1998;24:463-72.

[57] Godin G, Sheeran P, Conner M, Delage G, Germain M,Bélanger-Gravel A, et al. Which survey questions changebehavior? Randomized controlled trial of mere measure-ment interventions. Health Psychol 2010;9:636-64.

[58] Ferrari JR, Barone RC, Jason LA, Rose T. The use ofincentives to increase blood donations. J Soc Psychol1985;125:791-3.

[59] Ditto B, France CR, Albert M, Byrne N, Smyth-Laporte J.Effects of applied muscle tension on the likelihood of blooddonor return. Transfusion 2009;49:858-62.

[60] Oswalt RM. A review of blood donor motivation andrecruitment. Transfusion 1977;17:123-35.

[61] Godin G, Amireault S, Vezina-Im LA, Germain M,Delage G: The effects of a phone call prompt on sub-sequent blood donation among first-time donors. Trans-fusion, Epub aehad of print, June 9, 2011. DOI: 10.1111(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21658045).

[62] Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior changetechniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008;27:379-87.

[63] Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D,Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for

237INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

implementing evidence based practice: a consensusapproach. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:26-33.

[64] Godin G, Conner M, Sheeran P, Belanger-Gravel A,Germain M. Determinants of repeated blood donationamong new and experienced blood donors. Transfusion2007;47:1607-15.

[65] Godin G, Sheeran P, Conner M, Germain M, BlondeauD, Gagne C, et al. Factors explaining the intention togive blood among the general population. Vox Sang2005;89:140-9.

[66] Armitage CJ, Conner M. Social cognitive determi-nants of blood donation. J Appl Soc Psychol 2001;31:1431-57.

[67] Dholakia UM. A critical review of question-behavior effectresearch. Rev Mark Res 2010;7:145-97.

[68] Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel grouprandomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:726-32.

[69] Lowe CF, Horne PJ, Tapper K, Bowdery M, Egerton C.Effects of a peer modelling and rewards-based interventionto increase fruit and vegetable consumption in children. EurJ Clin Nutr 2004;58:510-22.

[70] Hardman CA, Horne PJ, Fergus Lowe C. Effects ofrewards, peer-modelling and pedometer targets on chil-dren's physical activity: a school-based intervention study.Psychol Health 2011;26:3-21.

[71] Brehm JW. A theory of psychological reactance. NewYork: Academic Press; 1966.

[72] Titmuss RM. The gift relationship: from human blood tosocial policy. London: Allen & Unwin; 1970.

237.e1INTERVENTIONS PROMOTING BLOOD DONATION

APPENDIX A

Supplementary file 1. Formula used to calculate 80% PIs and transformations applied.The following formula and transformations were applied given that the effect sizes of the present review

were OR:

PI ¼ M*� tffiffiffiffiffiffi

T2p

þ Vm*

PI = ex (exponential of the result obtained)Effect size [M*] = lnORt = t valueT2 = τ2 (an indicator of heterogeneity computed automatically by RevMan)Variance [Vm⁎] = (lnCIupper − lnOR)/1.96 = SE2

Source: Borenstein et al [18].

Supplementary File 2. Summary of the Studies Included and Their Results

Reference Objective of the study Population Study design Sample Type of intervention Mode of deliveryTheoryused OR (95% CI)

Chamla et al [36] Retentionof donors

Novice andexperienced

donors

RCT N = 316 42.1% ♂ Cognitions based Mail andtelephone

SCT Exp: experimentalCont: control

2.08 (1.14-3.80)Cialdini andAscani [37]

Unspecified Unspecified Unspecified N = 189College studentsof both sexes

Foot-in-the-door/door-in-the-

face

Face-to-face RCM Exp: extreme-then-critical

request conditionCont: critical-

request-only control1.17 (0.36-3.78)

Cioffi andGarner [56]

Unspecified Unspecified RCT † N = 1121College students

Measurement ofcognitions

E-mail FPP Exp: active-noresponse option

Cont: no message sent2.44 (1.04-5.73)

Clee andHenion [38]

Retentionof donors

Novice donors RCT † N = 338 Cognitions based Telephone RT Exp: HN/LICont: LN/HI

1.52 (0.64-3.62)Ditto et al [59] Retention

of donorsNovice andexperienced

donors

RCT N = 1209Age, 21.9 ± 3.4 y

49.6% ♂

Muscle tension Video and face-to-face

– Exp: upper bodyCont: no treatment1.48 (0.95-2.30) §

Ditto et al [31] Retention of donors Experienceddonors

RCT N = 726Age Exp:

22.2 ± 6.8 yAge Cont:

21.7 ± 5.8 y41% ♂

Muscle tension Video and face-to-face

– Exp: applied tensionCont: no treatment1.16 (0.82-1.66)) ⁎⁎

Evans, 1981 [33](study 2)

Recruitmentand retentionof donors

Potential, novice, andexperienced donors

RCT N = 488Age, 18 y40.2% ♂

Cognitions based Telephone EAT F2,440 = 0.392,P = .67

Ferrari et al [51] Unspecified Unspecified RCT † N = 68Age, 18-20 y

Reminders Telephone – Exp: prompt conditionCont: nonprompt

condition13.91 (1.68-114.82)

Ferrari et al [58] Unspecified Novice andexperienced

donors

RCT † N = 80 Collegestudents

of both sexes

Incentives Face-to-face – Exp: E conditionCont: C condition3.86 (1.47-10.13)

237.e2

GODIN

ETAL

Ferrari andLeippe [39](study 1)

Unspecified Potentialand donors †

RCT † N = 84Age: 19.6 y30.1% ♂

Altruism Tape recorder NAT Exp: combined conditionCont: no message2.24 (0.36-13.78)

Ferrari and Leippe [39](study 2)

Unspecified Potentialand donors †

RCT † N = 112Age, 18.8 y19.6% ♂

Altruism Tape recorder NAT Exp: low RD/no accessCont: high RD/no access22.14 (2.58-190.16)

Foss and Dempsey[40] (study 1)

Recruitment andretention of donors

Potentialand donors †

Unspecified N = 76Dormitory residents

47.8% ♂

Foot-in-the-door/door-in-the-

face

Face-to-face SPT Exp: 3-d delayCont: control condition

1.75 (0.39-7.95)Foss and Dempsey[40] (study 2)

Recruitment andretention of donors

Potentialand donors †

Unspecified N = 135Dormitory residents of

both sexes

Foot-in-the-door/door-in-the-

face

Telephone SPT Exp: poster requestPotential and donors ¶

Cont: control condition1.07 (0.06-18.04)

Foss and Dempsey[40] (study 3)

Recruitmentand retentionof donors

Potential and donors † Unspecified N = 163Dormitory residents

of both sexes

Foot-in-the-door/door-in-the-

face

Face-to-faceand telephone

SPT Exp: poster requestCont: control condition

7.73 (1.54-38.66)Gimble et al [41] Recruitment and

retention of donorsNovice, experienced,

and temporarydeferred donors

RCT N = 65 874Age, 38-40 y

Exp: 57%-63% ♂

Cont.: 57-59% ♂

Cognitions based Unspecified CIPT Exp: group ECont: group C

1.11 (1.02-1.21)

Godin et al [13] Retention of donors Novice andexperienced donors

RCT † N = 4672Age Exp: 44.7 ± 11.8 yAge Cont: 43.8 ± 12.1 y

Exp: 61.7% ♂

Cont: 61.3% ♂

Measurement ofcognitions

Mail TPB Exp: experimental groupCont: control group1.24 (1.09-1.41) ††

Godin et al [57] Retention of donors Novice donors RCT N = 4391Age, 30.4 ± 12.9 y

47% ♂

Measurement ofcognitions

Mail andtelephone

TPB Exp: implementationintention

Cont: control condition1.16 (0.98-1.36)

Hayes et al [42] Recruitment andretention of donors

Potential, novice, andexperienced donors

RCT † N = 914Adults

Foot-in-the-door/door-in-the-

face

Telephone SPT Exp: FIDCont.: control request

2.82 (1.69-4.69)Jason et al [43](study 1)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT † N = 300College students

Cognitions based Mail andtelephone

– Exp: MLCont: M

4.13 (0.45-37.57)Jason et al [43](study 2)

Recruitment ofdonors

Unspecified QE N = 64College students

Cognitions based Face-to-face – Exp: friendsCont: strangers

2.86 (0.80-10.24)Jason et al [34] Unspecified Unspecified QE Unspecified N

Workers anduniversity students

Incentives Face-to-face – F1,25 = 12.30, P b .01

237.e3

INTER

VEN

TIO

NSPROMOTING

BLO

OD

DONATIO

N

(continued on next page)

237.e4

GODIN

ETAL

LaTour andManrai [44] (study 1)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT ⁎ N = 680Residents of a

Midwestern community

Cognitions based Mail andtelephone

TRA Exp: informational andnormative influencesCont: no informational

nor normative influences13.70 (4.74-39.65)

LaTour andManrai [44] (study 2)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT ⁎ N = 1200Residents of a

Midwestern community

Cognitions based Mail andtelephone

TRA Exp: strong informationalinfluence and

normative influenceCont: no informationalnor normative influence

4.17 (2.01-8.66)Lipsitz et al [52](study 1)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT ⁎ N = 156College students

Reminders Telephone – Exp: experimentalCont: control

2.63 (1.27-5.42)Lipsitz et al [52](study 2)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT ⁎ N = 156University students

Reminders Telephone – Exp: experimental conditionCont: control condition

2.86 (1.01-8.10)Pittman et al [53](study 1)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT ⁎ N = 284College students,faculty, and staff

Reminders Mail – Exp: 3-name reminderCont: 1-name reminder

1.59 (0.96-2.64)Pittman et al [53](study 2)

Unspecified Unspecified RCT ⁎ N = 122College students,faculty, and staff

Reminders Mail – Exp: group reminder)O

Cont: 1-name reminder2.27 (0.79-6.49)

Reich et al [45] Retention of donors Novice donors RCT N = 691952.5% ♂

Altruism Telephone ande-mail

– Exp: script ACont: script B

1.23 (1.09-1.38) #

Royse [46] Retention of donors Novice donors RCT ⁎ N = 1003Median age, 22 y

46% ♂

Foot-in-the-door/door-in-the-

face

Mail SPT Exp: volunteer groupCont: control group1.12 (0.79-1.59)

Rushton andCampbell [47]

Unspecified Unspecified Unspecified N = 43Age, 18-21 y

All ♀

Modeling Face-to-face SLT Exp: vicariouspunishment condition

Cont: no-model condition39.67 (1.28-1229.87)

Sarason et al [48] Recruitment andretention of donors

Potential andnovice donors

Unspecified N = 9378High school students

Modeling Face-to-faceand video

SLT Combined treatment(55.4%) vs control

(44.6%) = P b .013 ‡‡

Sarason et al [49] Recruitment andretention of donors

Potential andnovice donors

Unspecified N = 4970High school students

48% ♂

Modeling Face-to-faceand video

SLT Exp: videotapeCont: control presentation

1.25 (1.06-1.47)

Supplementary File 2. (continued)

Reference Objective of the study Population Study design Sample Type of intervention Mode of deliveryTheoryused OR (95% CI)

Sinclair et al [32] ‡ Retention of donors Novice andexperienced donors

RCT N = 427Age, 31.1 ± 13.5 y

Exp: 46.2% ♂

Cont: 35.8% ♂

Cognitions based Telephone – Exp: motivationalinterview group

Cont: no-interviewcontrol group

1.61 (0.93-2.78)Upton [50] Retention of donors Experienced and lapsed

donorsUnspecified N = 1261

82% ♂

Altruism Telephone TOA Exp: low reward/high motivation

Cont: high motivation/high reward

6.91 (4.22-11.34)Whitney andHall [54]

Retention of donors Novice and experienceddonors

QE N = 285 87954% ♂

Reminders Telephone – Exp: heard messageCont: did nothear message

1.09 (1.07-1.12)Wiesenthaland Spindel [55]

Retention of donors Novice donors Unspecified N = 209 Reminders Telephone – Exp: experimentalcondition 1

Cont: control group1.84 (0.76-4.49)

The symbol (♂) represents the percentage of the sample that is male.

Abbreviations: NAT indicates norm activation theory [30]; CIPT, consumer information processing theory; Cont, control group used to compute the effect size; EAT, endogenous attribution theory;

Exp, experimental group used to compute the effect size; FPP, feature-positive paradigm; QE, quasi-experimental design; RCM, reciprocal concession model [16]; RCT, randomized, controlled trial; RT:

reactance theory [71]; SCT, social cognitive theory [26]; SLT, social learning theory [27]; SPT, self-perception theory [25]; TOA, theory of altruism [72]; TPB, theory of planned behavior [29]; TRA, theory of

reasoned action [28]; HN/LI, high need/low implication; LN/HI, low implication/high need; low RD, low reponsibility denial; high RD, high responsibility denial; FID, foot-in-the-door; ML, media plus a

personal letter; M, media only.⁎ No information on the randomization procedure.† The authors did not specify which type of donors was included in their study.‡ Although the study had a 12-month follow-up, we only used the 9-month outcome to have intention-to-treat results.§ The results of men and women were combined within the control and the experimental groups.O The group reminder condition was used as the experimental group to compute the effect size to differentiate it from the study 1 of Pittman et al [53].¶ The poster request condition was used as the experimental group to compute the effect size, given that it was testing the effect of the foot-in-the-door technique.# The results reported are for the second donation (ie, percentage of first-time donors who returned for a second donation).⁎⁎ Analyses controlled for age, sex, previous blood donations, experience, and body mass index.†† Analyses controlled for age.‡‡ Analyses controlled for school, blood center, donation history, and size.

237.e5

INTER

VEN

TIO

NSPROMOTING

BLO

OD

DONATIO

N

237.e6 GODIN ET AL

Supplementary file 3. Funnel plot of cognition-based interventions (s = 8).

Supplementary file 4. Funnel plot of interven-tions using reminders (s = 7).

Supplementary file 5. Formula used to convertSMD into OR.

logOR ¼ dðπ=ffiffiffi

3p

Þ

d = SMDSource: Borenstein et al [18].Supplementary file 6. Funnel plot of interven-

tions delivered by telephone (s = 10).