DRUG TRAFFICKING, POROUS BORDERS AND HUMAN INSECURITY: TRANSNATIONAL SECURITY AND DEMOCRATIC...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of DRUG TRAFFICKING, POROUS BORDERS AND HUMAN INSECURITY: TRANSNATIONAL SECURITY AND DEMOCRATIC...

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND

DRUG TRAFFICKING, POROUS BORDERS AND

HUMAN INSECURITY: TRANSNATIONAL SECURITY

AND DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION IN MYANMAR

A dissertation submitted by Gerad Collingwood, BA

FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE

BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONOURS)

FACULTY OF ARTS (USQ)

2014

1

ABSTRACT

Since the end of the Cold War there has been increased recognition of non-traditional

security threats, such as drug trafficking, as contributors to instability within and amongst

states. Myanmar (formerly Burma), the hub of the ‘Golden Triangle’ drug trade, has been a

state in constant conflict since its independence in 1948. Using the theoretical framework of

human security, this thesis analyses the impact of the drug trade on both Myanmar’s society

and its transnational impacts. First, this thesis examines the extent to which the drug trade

in Myanmar permeates to other states through porous borders creating a situation of

transnational human insecurity. Secondly, Myanmar’s current democratic transition is

examined to determine how the state of Myanmar is undergoing changes in its state-

building process. Finally, these two themes are intersected to demonstrate how illicit

narcotics trafficking are hampering Myanmar’s transition towards a liberal democracy. This

thesis provides new insight into the problems posed by transnational narcotics trafficking

and human insecurity to the democratisation process.

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis, being a labour of love coloured by despair, owes its successful completion to

many people. Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Anna Hayes, for her invaluable

insight, support, and ceaseless encouragement. I would also like to thank Richard Gehrmann

for inspiring me for so long through my undergraduate degree, which has led to this thesis.

The staff at the Sydney South East Asia Centre and the students who attended the 2014

Honours bootcamp also have my gratitude for helping me hone my writing skills and ideas.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family. They have politely pretended to be

interested in my thesis while I waxed lyrical about its implications and also provided me with

much needed breaks from study throughout the year.

3

CERTIFICATION OF THESIS

I certify that the ideas, results, analyses and conclusions written in this thesis are entirely my

own effort, except where otherwise acknowledged. I also certify that this work is original

and has not been submitted for any other award.

_________________________ _______________

Signature of Candidate Date

ENDORSEMENT:

_________________________ _______________

Signature of Supervisor Date

4

Contents

ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................. 2

CERTIFICATION OF THESIS ......................................................................................................... 3

ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................ 6

MAP: UNION OF MYANMAR ...................................................................................................... 8

CHAPTER 1.................................................................................................................................. 9

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 9

Topic Statement and Central Questions ................................................................................ 9

Definition of Key Terms ....................................................................................................... 13

Democracy ....................................................................................................................... 13

Methodology and Analytical Framework ............................................................................ 14

Literature Review ................................................................................................................. 17

Chapter Outlines .................................................................................................................. 24

CHAPTER 2................................................................................................................................ 26

THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE DRUG TRADE ..................................................................................... 26

The nature of the Golden Triangle....................................................................................... 26

5

Securing the state with drugs .............................................................................................. 32

Myanmar’s human security dichotomy ............................................................................... 37

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 43

CHAPTER 3................................................................................................................................ 45

MYANMAR’S DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION ................................................................................ 45

A history of failure ............................................................................................................... 45

‘Quasi’-civilian government in Myanmar............................................................................. 50

Exclusion and marginalisation in democratic Myanmar ...................................................... 57

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 60

CHAPTER 4................................................................................................................................ 62

OPIUM FOR THE MASSES ......................................................................................................... 62

LIST OF REFERENCES ................................................................................................................ 67

6

ACRONYMS

AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ATS Amphetamine-Type Stimulant

BSPP Burma Socialist Programme Party

CCP Chinese Communist Party

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CPB Communist Party of Burma

GMD Guomindang (Kuomintang)

HIV Human Immuno-deficiency Virus

IDP Internally Displaced Person

IDU Injecting Drug User

KIO Kachin Independence Organisation

KKY Ka Kwe Ye

MNDAA Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army

NDA National Democratic Army

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

7

NLD National League for Democracy

NUP National Unity Party

SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

SLORC State Law and Order Restoration Council

SPDC State Peace and Development Council

SSA-E Shan State Army – East

SSA-N Shan State Army – North

UMEH Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

USA United States of America

USDA Union Solidarity and Development Association

USDP Union Solidarity and Development Party

UWSA United Wa State Army

WHO World Health Organisation

8

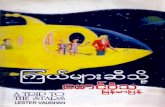

MAP: UNION OF MYANMAR

UN 2012, Map No. 4168, Rev. 3, http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/map/profile/myanmar.pdf

9

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Topic Statement and Central Questions

This thesis examines the Golden Triangle drug trade and its relationship with

democratisation in Myanmar.1 Security and democracy are two key issues that are often

intertwined, thereby influencing the other. Illicit drug trafficking has been recognised as a

non-traditional security issue for many years. In addition, it has also been recognised that

illegal drugs, and the traffic of illegal drugs, can significantly affect both human and state

security.2 However, the human impact of the international drug trade is often viewed

through the prism of its effect on developed western consumer countries. As a result, this

approach marginalises the experience of developing production and transit countries, such

as Myanmar, which are disproportionately affected. The transnational nature of the drug

trade and the existence of long and porous borders along Myanmar’s boundaries mean

domestic insecurity in one country can easily become a transnational issue.

1 The use of either Myanmar or Burma can often be contentious. For the purpose of this thesis, and attempt to

remain apolitical, the approach followed by Steinberg shall be used. The term Myanmar will be used for the period after the military coup in 1988 and the term Burma shall be used for the period before that. The term Burma/Myanmar may also be used to reflect historical continuity. City names such Rangoon becoming Yangon also reflect this change. Burman refers to the majority ethnic group in the country, the Bamar. Burmese refers to the inhabitants of Burma/Myanmar as a whole. These clarifications should not be taken as accepting the legitimacy of military rule in Burma/Myanmar. For further reading see Steinberg, D 2001, Burma: the State of Myanmar, Georgetown University Press, Washington, D.C.

2 For further reading see Swanstrom, N 2007, 'The Narcotics Trade: a threat to security? National and

transnational implications', Global Crime, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1-25, viewed 09/03/2014, Taylor & Francis.

10

Since the end of the Cold War, non-traditional security threats have come to play an

increasing role in interpretations and responses to global security. Identified non-traditional

security threats include transnational crime, disease epidemics, large people flows and

terrorism (Commission on Human Security 2003). Non-traditional security threats challenge

the security of states in a variety of ways. They may challenge the state’s monopoly on

violence or create social instability through economic, political or health insecurity

(Commission on Human Security 2003). Drug trafficking is one aspect of transnational crime

that has come to receive increasing attention from the international community in recent

years.

This thesis provides a timely human security analysis of the Golden Triangle drug trade. The

extremely fluid and volatile nature of transnational crime means that the Golden Triangle

drug trade often changes and scholarly work on these topics needs frequent updating. The

majority of works written about the Golden Triangle are older articles written before the

dramatic rise of the Golden Crescent after the 2002 Afghanistan invasion. Of the articles

written later, few deal with the overarching theme of human security in the region and the

impacts it may have. This is especially important now as Myanmar once again attempts,

albeit slowly, a democratic transition. Human security in Myanmar will be an important

factor in determining whether the transition is successful or not.

The idea of drug trafficking as threat is not in itself a new concept. The United States of

America (USA) launched its ‘War on Drugs’ well before the end of the Cold War (McFarlane

2000, p. 36). However, this was more a statist response to a social ill rather than a genuine

identification of the security implications the drug trade may actually have (Crick 2012).

Additionally, the illicit trade in drugs is strongly linked to the spread of disease epidemics

11

such as HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C (Xiao et al. 2007, p. 666). The large sums of money created

by the drug trade also frequently help fund insurgency groups and encourage corruption

(Isacson 2002; Sanderson 2004). Drug trafficking is often linked with the issue of porous

borders. Porous borders by their nature enable and may even encourage drug trafficking;

people movements are hard to track and so drugs and money may flow virtually unimpeded

across borders (Singh & Nunes 2013). Transnational crime, disease epidemics, large

uncontrolled people flows and insurgency are all extant threats in and around Myanmar.

This makes Myanmar an excellent example of how these threats, resulting from the drug

trade, affect the democratisation process.

The Golden Triangle is located in South-East Asia and is comprised of the countries

Myanmar, Thailand and Laos. Historically, the Golden Triangle has been a major producer of

heroin for the South-East Asian and Pacific market (Chalk 2000). It is currently the second

largest heroin producing area in the world, after the Golden Crescent states, Afghanistan,

Pakistan and Iran, in South-West Asia (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2013).

There is also now a large trade in amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), especially

methamphetamine, produced by the Golden Triangle (Meehan 2011). It is this adaption to

new and emerging drug markets that currently differentiates the Golden Triangle from the

Golden Crescent, which remains predominately an opium-growing region.

12

Figure 1. Map of opium producing areas and ethnic armed groups. Source: http://www.economist.com/node/15707981

The drug trade in the Golden Triangle is

centred mainly upon Myanmar, specifically

the marginalised hill tribes of the Shan and

the Wa (See Figure 1.) (Meehan 2011).

Borders within the Golden Triangle are

typically porous with frequent uncontrolled

people movements (Dupont 1998). Large

porous borders exist between Myanmar, the

main driving force behind Golden Triangle

drug production, and China and India (Dupont

1998; Singh & Nunes 2013). Both China and

India have rising rates of drug use centred

particularly on those areas closest to these

borders and along transit routes for drug

trafficking (Chalk 2000; Dupont 1998; Huang,

Zhang & Liu 2011). This has given rise to

significant issues regarding the spread of

HIV/AIDS in these regions, as well as contributing to an insurgency in North-East India (Singh

& Nunes 2013).

This thesis analyses the relationship between Myanmar’s transition towards democracy, the

Golden Triangle drug trade and human (in)security. It will critically assess the following

questions;

1. What is the Golden Triangle and how does it operate in the region?

13

1.1 How does the Golden Triangle affect state security in the region?

1.2 How is human security affected by the narcotics trade in the Golden

Triangle?

2. What is the nature of the democratic transition in Myanmar?

2.1 How has democracy been treated historically in Burma/Myanmar?

2.2 Is Myanmar’s current transition actually democratic?

2.3 Is the current system adequately representative and inclusive?

3. Is the Golden Triangle drug trade affecting the course of democratic transition in

Myanmar?

Definition of Key Terms

Democracy

Democracy is a very broad term that can have many meanings. For the purpose of this

thesis, democracy will be defined as posited by Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung that,

the term “democracy” incorporates both the procedure to elect governing

authorities (competitive, multiparty elections, public participation in politics);

liberal principles such as social, political, economic, and religious rights; and

14

the setting of limits to government power over society and individuals (2003,

p.444).3

This is intended to clarify the use of democracy throughout this thesis as meaning a liberal

democracy and not an illiberal democracy.

Methodology and Analytical Framework

This thesis follows a mixed method approach, utilising a wide variety of secondary and

primary sources. The research for this dissertation will be primarily resourced by peer

reviewed works from journal articles, topic specific book and edited book chapters. News

articles as well as reports and statistics authored by non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

will also be used. NGO sources will include the United Nations (UN) and its various organs

such as United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the World Health

Organisation (WHO). It will also include reports issued by various research organisations.

These sources will be used to attempt to overcome the inherent limitations in this thesis

that are presented by the secretive nature of the drug trade and the previous junta in

Myanmar. Secondary sources will be used to gain perspectives on the many issues involved

in this area and to provide general information of the situation however, qualitative and

quantitative data from all sources will form the majority of research used. The period of

research will be principally focused from the late-1980s until June 2014, however may

extend to earlier time periods as appropriate.

3 Burmese names are a whole and generally not separable into first and surnames. This thesis will follow this

convention in using names in their entirety.

15

This thesis will use human security as its analytical framework to examine the relationship

between drug trafficking in Southeast Asia’s Golden Triangle region and democratic

development in Myanmar. Human security offers an alternative to the traditional realist or

liberalist approaches to international relations. Unlike realism or liberalism, human security

focuses on the individual’s security rather than the security of the state (Commission on

Human Security 2003). The concept of human security was first articulated in the United

Nations Development Program’s (UNDP) 1994 Human Development Report (United Nations

Development Program 1994). The UNDP (1994) delineated the following essential elements

of human security; food security (access to basic food provisions), political security

(protection of human rights and basic freedoms), economic security (access to an income),

personal security (protection from violence), health security (protection from disease),

environmental security (protection from environmental disaster, both natural and

anthropogenic in nature) and community security (protection of traditions). Human security

is centred on the idea that people are ‘the most active participants in determining their

well-being’ (Commission on Human Security 2003, p. 4).

While human security changes the current paradigm of statist security, it is not in conflict

with it; rather it compliments it. It does so by expanding the range of actors from states

alone, by identifying dangers that may not have been viewed as traditional threats to state

security and by empowering people (Commission on Human Security 2003, p. 4). This makes

a human security approach particularly useful in analysing conflicts involving both non-state

actors, such as transnational criminal groups and separatists, and non-traditional threats,

such as drug trafficking and disease epidemics. This is because it enables these groups and

phenomena to be analysed as actors and contributors within a conflict, rather than, as state

16

centric theories contend, criminals or domestic policy issues under the authority of the state

(Campos 2007; Commission on Human Security 2003). Dupont (2001), in his theory of

extended security, also argues for the inclusion of non-state actors and the non-traditional

security threats in modern security analyses. He does this while still recognising, ‘that

maintaining the territorial integrity, political sovereignty, economic viability and social

cohesion of the state are key measures of security.’ (Dupont 2001, p. 8). However, given

that the purpose of this thesis is to analyse democratic development, human security, with

its main referent of security being the individual, is more suitable. As democratic

development is all about the process of giving power to the people, human security is a

more suitable analytical tool to examine exactly how empowered people are. The UNDP’s

1994 Human Development Report asserts the recognition of human security is vital in

preventing future conflicts (United Nations Development Program 1994). Given the nature

of ongoing conflicts to stifle democracy, human security has a clearly defined role to play in

countries transitioning to democracy.

The line of argument taken by both the UNDP and the Commission on Human Security

formulate the broad school of human security theory. This school of thought views all

human insecurities as equal and part of a whole. The basic securities listed by the UNDP are

often differentiated into two categories; freedom from fear and freedom from want. While

the broad school of human security generally does not view one as more important than the

other, the narrow school of human security theory contends that freedom from fear is the

more important in analytical terms.

Authors such as Andrew Mack contend that using the broad school of human security

‘comes at a real analytical cost’ and ‘loses any real descriptive power’ (2004, p. 367).

17

Further, he argues that although there does exist an interconnectedness between the

different realms of the broad school it is ‘unhelpful’ and real analytical value can only be

ascertained by separate analyses (Mack 2004, p. 367). Richard Jolly and Deepayan Basu Ray

however, take the view, ‘unless one wishes to argue there is no interconnectedness at all,

the case for taking account of the interactions and consequences seems overwhelming

(cited in Smith & Whelan 2008, p. 5). On Myanmar more specifically, Selth (2010, p.423) has

said that there is a diverse range of issues present, many of which are inter-related. Hayes

(2010, p. 91) also approaches human security from a broad perspective saying, ‘both state

security and human security are interdependent…[and] a deficiency in one could lead to

another.’ Given that in many areas experiencing conflict and societal transitions there are a

myriad of different phenomena and actors involved, not analysing the interplay between

them would give an incomplete account of the situation. The broad school of human

security is clearly important to this dissertation as the situation in Myanmar involves several

different state and non-state actors connected through a complex web of human

interaction.

Literature Review

The discussion surrounding the global narcotics trade and its security implications has been

largely focused upon the ‘hard security’ threat of the link between drugs and financing for

terrorist and/or separatist groups. The end of the Cold War saw a rapid decline in the state-

sponsorship of terrorism and separatism, which necessitated a search for new forms of

income from many of these groups (Piazza 2011; Sanderson 2004). An increasing number of

these groups, including groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan,

have now turned to transnational crime as a means of finance, in particular drug production

18

and trafficking (Piazza 2011; Sanderson 2004; Swanstrom 2007, p. 5). This has also been the

case in India and Burma/Myanmar where ethnic insurgencies have used drug trafficking as a

source of income to fund their armies (Lall 2006, p. 432; Singh & Nunes 2013; Swanstrom

2007, p. 20).

The illicit nature of the narcotics trade has also led to an increased militarisation of the

criminal groups themselves. This is especially apparent in countries like Mexico where the

drug cartels are growing increasingly sophisticated and professional; making use of military

tactics and high-powered weapons to secure trafficking routes (Chelluri 2011). In Columbia

too there was a time when drug cartels directly threatened the authority of the state, using

political assassinations, kidnappings and bombings in an attempt to become equal

shareholders of authority (R Godson & W Olsen cited in Dupont 2001, p. 29). The literature

clearly shows a strong correlation between the transnational narcotics trade and challenges

to states’ monopoly of violence.

While there is a demonstrable relationship between the drug trade and a propensity for

violence, it does not follow that this relationship must exist. In support of this point,

Tagliacozzo argued in his work that ‘violence seems to be less inherent in Southeast Asia’s

drug trade than is the case in Afghanistan or the Andes’ (2009, p. 249). Indeed, many of the

ethnic insurgent groups present in Myanmar have been, and are actively involved in, the

drug trade. However, while the violence of these insurgencies has dropped significantly

since the 1980s, it is important to note that the drug trade has skyrocketed (Ball 1999, p. 3;

Kivimäki 2008). Tagliacozzo reasoned this may be due to political accommodations reached

between elites in this area and groups on the borders that participate in the trade (2009, p.

249).

19

This is supported by the works of Ball and Lintner (1999; 2000), in which both concluded

there has been involvement of elites in Myanmar’s political circle in the drug trade.

However, both of these articles were written before the deaths of Khun Sa and Lo Hsing-

Han; two major figures in the drug trade and its government links. In Meehan’s (2011) more

recent article, discussing state-building and the drug trade in Myanmar, the still significant

links between the state and the drug trade were illuminated. However, according to

Meehan this in itself does not weaken the state. Indeed, many authors argued that the drug

trade, and its co-option by authorities, has been instrumental in halting the violence with

concessions being given to ethnic insurgents to allow them to continue trafficking in

narcotics in exchange for a cessation of hostilities (Ball 1999; Dupont 1998; Emmers 2004;

Kivimäki 2008). It seems that the relationship between the narcotics trade and violence is

dependent upon the reaction of the given states’ government. It would appear that when

governments pursue direct efforts to stem the flow, the cumulative result is higher levels of

conflict, whereas co-option can result in a decrease in violence.

While drugs and violence may not always be present simultaneously, the high level of

correlation has led to the view that the narcotics trade is an issue that needs to become

securitised in order for an effective resolution be found. Crick (2012), examined the

progression of the securitisation agenda in the attempt to stem the international narcotics

trade. He found that since the inception of the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs in

1961, the paradigm of the debate around narcotics control has shifted from one based on

human security to one based on the threat presented by narcotics trafficking to the global

order and state stability (Crick 2012). In his paper on Mexico’s narcotics trade Chelluri

(2011) strongly advocated for this securitisation of the drug trade and argued for a military

20

response to the powerful cartels operating in Mexico. Dupont identified drug trafficking as

a security issue, arguing that ‘narcotics trafficking is…challenging East Asian states’

traditional monopoly on violence and taxation…[and it cannot] be addressed without

substantial regional cooperation’ (1998, p. 22). While Dupont did not argue for a direct

military response, he did recognise that the issue of transnational drug trafficking is no

longer just a matter of law-enforcement and it required a cooperative transnational

response (1998). The USA has been instrumental in perpetuating the securitisation of the

illicit narcotics industry through promoting its ‘War on Drugs’ often by providing material

support for eradication programs and military responses (Chelluri 2011, p. 96; Crick 2012, p.

411). Despite the move to an increased securitisation of narcotics problem the efforts have

often been unsuccessful and done little more than moved the problem to another part of

the producing country or to an adjacent state (Isacson 2002; Sanderson 2004). The

movement between states of narcotics trafficking and production highlights the

transnational aspect of the security dilemma.

Perhaps the failure of certain state responses in the securitisation of drugs has been the

result of an under-appreciation of the transnational nature of narcotics trafficking. Authors

such as Dupont (2001) argued that transnational security is an important consideration in

modern international relations as threats of a transnational nature may move free of

territorial borders; yet in their attempts to combat transnational threats states are confined

by the very territorial boundaries which define the state. Both Emmers and Swanstrom also

recognised that the state’s ability to effectively combat transnational crime is compromised

by its inability to assert jurisdiction outside its territorial borders; a problem that

transnational criminal groups take full advantage of (2004, p. 5; 2007, p. 21).

21

Even regional organisations such as the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN),

which attempt to transcend territorial borders and create transnational solutions, often do

not ultimately succeed in securitising transnational threats (Haacke & Williams 2008). Hacke

and Williams reasoned this is because for an issue to be successfully securitised, states must

share a similar perception of the threat and agree collectively on an appropriate response

(2008, p. 776). They demonstrated that securitisation through regional organisations is

possible, as in ASEAN’s response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) (Haacke &

Williams 2008, p. 803). However, without the collective recognition of the severity of the

threat, as has been the case with transnational crime, those threats will be left unresolved

(Haacke & Williams 2008). This is also demonstrated in McCarthy’s analysis of Myanmar-

ASEAN relations. McCarthy argues that although ASEAN recognises the transnational threats

emanating from Myanmar, it has been approached in a haphazard and inconsistent manner

(2008). Therefore, it would seem that transnational security threats are currently still dealt

with primarily on an individual basis by states that are reluctant to accept infringements

upon their sovereignty.

Another significant issue, with particular relevance for Myanmar, is that of ethnic relations.

The ethnicities in Myanmar are broken down into eight major national races and 135

distinct ethnic groups (Holliday 2010, p. 118). This structure excludes Rohingya’s, referred to

as Bengali’s by most other ethnic groups, as they are seen as migrants and not actual

citizens of Myanmar (Holliday 2014). Burma/Myanmar has long struggled with the

complexity of its ethnic relations, and since independence this has frequently led to

separatism and insurgency by ethnic armies (Brown 1994; Holliday 2010; Smith 1999).

Brown (1994, p. 33), argued this has been largely the result of Burma/Myanmar becoming

22

an ‘ethnocratic’ state. He claimed that as the state favours the values of the ethnic majority

and attempts to spread them throughout lands of the ethnic minorities, the values of the

ethnic minorities are then marginalised, creating a backlash (Brown 1994, pp. 38, 48). Smith

concluded that suspicions from the ethnic minorities towards the Bamar majority already

existed before the Burman dominated state, evident in the absence of representatives from

several key ethnic groups at the Panglong agreement (1999, p. 79).

Strengthening this line of argument, Lintner states that warring had been prevalent

between the Burmese kings and the hill tribes before the British arrived and simply resumed

after the British withdrawal (2013, p. 108). The ceasing of power by General Ne Win in 1962

and the tearing up of the constitution served to reinforce the ethnic divide (Smith 1999, p.

79). This is further supported by Holliday, who reasoned that Burma descended into a

quagmire of ethnic conflict because of its inability to respond to the needs of the various

ethnicities and create an inclusive state (2010, p. 112). Burma/Myanmar’s failure in the past

to create a cohesive and stable state certainly has left a legacy that will be difficult to

overcome.

The current character of change in Myanmar, and exactly how much it represents a genuine

move towards democracy, is still very much contested. In the current debate of Myanmar’s

future, Udai Bhanu Singh supported the changes and has said, ‘[t]his time the change that is

occurring is substantive, not cosmetic’ (Singh 2013, p. 101). Singh pointed to the release of

political prisoners, the return of the National League for Democracy (NLD) and transition

from the military State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) to a ‘quasi-civilian’

government, among other reasons, for seeing this change as a genuine positive step

23

towards democracy (2013). The International Crisis Group also views the transition

positively and argues it represents genuine change (2013).

Lintner however, in his appraisal of the situation, noted that despite this seeming transition

to civilian government the military is still firmly entrenched in power, a position enshrined

within the 2008 constitution (Lintner 2013, p. 109). While Singh appeared optimistic in his

assessment of upcoming elections in 2015, predicting the NLD should win more seats, both

Lintner and Bhatia were more critical (Singh 2013, p. 101). They took the position that as the

2010 elections were not free and fair there is little reason to expect the 2015 elections to be

either (Bhatia 2013, p. 110; Lintner 2013, p. 108). The recurrent failure to address the issue

of ethnicity effectively and in such a way as to affect genuine reconciliation will also stunt

the prospect for political change (Bhatia 2013, p. 111; Lintner 2013, p. 109).

Bhatia departs from Lintner and Singh in his characterisation of exactly what kind of change

is important in Myanmar. He asserted that it is not so much whether the current changes

mark a transition but rather can these changes be undone (Bhatia 2013, p. 110). It is this, he

argued, that is most important as even if the changes were real and significant, so long as

the military still possessed the power to roll back any changes, which they still currently do,

then it is not possible to ascertain the chances of democratic transition (Bhatia 2013). Jones,

examined the issue from a political economy perspective and found that the power

structures from the old regime were still present in the new Myanmar (2013). As such, he

concluded that there has been little genuine change because the main stakeholders in

power have not really changed (Jones 2013).

The current literature concerning the overarching themes this thesis addresses, suggests

Myanmar’s situation is precarious. In certain countries, transnational drug trafficking

24

organisations have, in the past, challenged the power of the state. Although there are

increasing moves to securitise the issue of transnational crime, including narcotics

trafficking, there is a lack of effective action at the regional level between states to

effectively securitise the problem. The unresolved issues of Burma/Myanmar’s ethnic

tensions also serve to complicate the already difficult issue of Myanmar’s transition to

democracy. The literature also suggests the military in Myanmar, the tatmadaw, is still a

potential threat to a democratic transition under the current system. There is however, an

absence of research considering the threat of drug trafficking to Myanmar’s current

democratic transition. This thesis examines that query and links it to ideas of transnational

and human security.

Chapter Outlines

This dissertation is composed of four chapters that examine the themes of drug trafficking

and democratic development in Myanmar. The first chapter provides an introduction to this

topic and includes the topic statement, central questions, key terms, methodology,

theoretical framework and literature review. This chapter positions the dissertation within

the current research field and outlines the argument of the thesis. The chapter concludes

with the chapter outlines.

Chapter Two, ‘The Golden Triangle Drug Trade’, examines the extent of drug trafficking in

Myanmar and the surrounding region. This chapter begins by chronologically examining the

development and changes in the drug trade that have taken place. It then analyses the

effect on state security by examining the level of state involvement in Myanmar. The

25

chapter concludes with an extensive examination of the human security impact the

narcotics trade has in Myanmar.

Chapter Three, ‘Myanmar’s Democratic Transition’, analyses the political changes in

Myanmar. The chapter begins by tracing Myanmar’s previous experiences with democracy

since independence in order to contextualise the significance of the current transition. It

then moves to an examination of the current changes and how democratic the new system

really is. Finally, the chapter concludes with an analysis of how representative and inclusive

the democratic transition has been.

Chapter Four, ‘Opium for the Masses’, is the concluding chapter of this dissertation. It

synthesises the findings from Chapter Two and Chapter Three. It concludes the drug trade is

hampering the democratic transition. It identifies that there are significant levels of

corruption throughout the state that directly affect people’s human security. The tatmadaw

is still significantly involved with the drug trade both directly and indirectly. These

conditions are frequently related to increased conflict driving thousands to become

refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) devoid of rights. The rampant human

insecurity resulting from the drug trade is slowing democratic transition.

26

CHAPTER 2

THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE DRUG TRADE

This chapter examines the Golden Triangle drug trade within Myanmar and neighbouring

countries and its effect on security. Firstly, it contextualises the situation by outlining the

extent of the drug trade in the Golden Triangle; its geographic expanse, history and how it

operates. This contextualisation is important to grasp the scale and scope of the complex

networks that are active in order to be able to analyse the impacts upon security. Secondly,

the issue of state security and how it is affected by the drug trade is analysed. As Myanmar

shifts towards democracy, the security of the state is essential to ensuring the stability

needed for a successful transition. Finally, the relationship between human security and the

drug trade is scrutinized. The role of human security and how it is affected by the drug trade

is vital. It establishes the human insecurity that results from the drug trade, the problems

facing the Burmese people and how they affect their democratic rights.

The nature of the Golden Triangle

As a geographic region the Golden Triangle straddles the borders of Myanmar, Laos and

Thailand. For many years the Golden Triangle has been synonymous with opium however,

opium was never grown in the region on any commercial scale until the 19th century (Lintner

2000). More widespread cultivation began as hill tribes from China’s opium growing Yunnan

province migrated into Burma and the surrounds following political instability in China

27

(Lintner 2000, p. 3). 4 Large scale growing for cash purposes really began after the Chinese

Communist Party’s (CCP) victory over Chiang Kai-Shek’s Guomindang (GMD). Some GMD

forces were unable to reach Taiwan and so moved into the Shan hills of Burma (Lintner

1994, pp. 93-4). In order to finance their continued fight against the CCP, the GMD needed

cash to support their effort. As a result the GMD forces began the cultivation of opium, and

with the help of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), began selling it to fund their

insurgency (Lintner 1994, p. 105; McCoy 2003). This led to a major change in the opium

trade in Burma. What had previously been a small industry to support local addicts soon

became a transnational enterprise. The GMD encouraged people to grow more and

exported up to 500kg of opium per week through Thailand to buy arms (Lintner 1994, p.

117). This led to the entrenchment of the opium trade as a way of financing insurgencies.

This method of financing insurgencies was embraced by many of the groups opposed to the

central government in Rangoon.

Insurgency has plagued Burma since its independence in 1948. This conflict has often been

based along ethnic divisions and their demand for autonomy (Lintner 1994). The Communist

Party of Burma (CPB) was for a long time a serious threat to the Burmese state (Lintner

1994). These forces needed money to continue their insurgency and in the mountainous

ranges of eastern Burma there are few sources of easy currency. Some groups, such as the

Kachin rebels, captured jade mines to help finance their struggle but for others, particularly

the Shan, there was little option except opium (Lintner 2000, p. 9). In response to this

4 The opium poppy itself is also not native to China but was brought by Arab traders in the 7

th and 8

th century.

For a more comprehensive history of opium in China, see Beeching, J 1975, The Chinese Opium Wars,

Hutchinson & Co Ltd, London.

28

insurgency, General Ne Win created special counter-insurgency units. The units, called the

Ka Kwe Ye (KKY), were given free rein of Burma’s roads to conduct drug trafficking

operations in the hope they would be self-funding (Meehan 2011, p. 381). These units

established extensive drug trafficking networks. By the time of their disbandment in 1973,

the program had produced two of Burma’s most notorious drug traffickers, Khun Sa and Lo

Hsing-han (Meehan 2011, p. 382). These men subsequently built large business empires,

both licit and illicit, and gained significant power within the state off the back of their drug

trafficking activities (Meehan 2011).

Eventually, the vast trade in opium led to the development of the heroin trade. GMD forces

operating in Laos and the Burma-Thai border began setting up heroin laboratories in the

1960s (Lintner 2000, p. 9). This was also followed by the building of heroin laboratories in

Laos under the control of the Laotian military (McCoy 2003). Local opium traders, often

Panthays, frequently received an armed guard from Lo Hsing-han’s KKY forces to transport

their goods to the GMD controlled heroin laboratories (Lintner 1994, p. 214).5 The heroin

was then sold in the rapidly growing Southeast Asian market, including to American troops

fighting in Vietnam. In addition, through the GMD’s extensive connections in Hong Kong,

Macau and Taiwan it was also distributed internationally (Lintner 1994, p. 215; McCoy

2003). Many more refineries began to start operations along the Thai-Burma border in the

years that followed (Lintner 1994). By this time the trade had penetrated deep into

Thailand’s security forces, who were heavily involved in facilitating the cross border trade

(Lintner 1994, p. 247). Thailand had become dependent upon the trade economically as

5 Panthays are one of Burma’s Muslim ethnic groups and of Chinese descent. They are known as Hui in China

and Haw in Thailand.

29

well, especially in the border areas (Lintner 1994, p. 248). Powerful drug kingpins, such as

Khun Sa and Lo Hsing-han, created strong networks including politicians and military figures

in both Thailand and Burma (Lintner 1994, p. 249). The Laotian military was also heavily

involved. Opium was traded by Shan insurgents in exchange for weapons from Laos (McCoy

2003, pp. 344-5). The corruption also penetrated the highest echelons of the military.

General Ouane, the commander of the Royal Laos Army, was directly involved in importing

opium and refining heroin in laboratories he owned; even using the military in battles to

secure the drug trade (McCoy 2003, pp. 344-5. ).

In 1989, the CPB disintegrated as ethnic groups within revolted against the primarily

Burman leadership and split into four separate ethnic armies: the United Wa State Army

(UWSA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), the Shan State Army

East (SSA-E) and the National Democratic Army (NDA) (Lintner 2000, p. 16). The new military

junta in Burma acted quickly to head off the chance of renewed conflict with these and

other armed groups and negotiated ceasefire agreements; offering inducements such as

freedom to trade in opium (Ball 1999, p. 3). To this end, ex-KKY commander Lo Hsing-han,

was sent to negotiate with the rebels in northern Shan state (McCoy 2003, p. 434). The

result was a massive spike in production (Ball 1999, p. 3). Heroin refineries also began

operation in areas under control of these ethnic armies, close to the Yunnan border (Lintner

2000, p. 17). This was to feed the growing Chinese demand for heroin and create a new

trade route to Hong Kong via southern China (McCoy 2003, pp. 434-5). Khun Sa, having now

positioned himself as the leader of the Shan nationalist movement, was facing increased

pressure from the SLORC and surrendered to government forces New Year’s Day, 1996

(Lintner 2000, p. 17; McCoy 2003, p. 439). Khun Sa began a new life in Yangon and opened a

30

Figure 2: Area under cultivation separated by country. Source: UNODC Southeast Asia Opium Survey 2013

company widely rumoured to be used for laundering money (Lintner 2000, p. 17). The

changes did little to affect the narcotics trade.

Initially, opium production expanded considerably. The area under cultivation in

Burma/Myanmar went from 103 000 hectares in 1988 to 160 000 in 1991 then finally

peaking in 1996 at 165 000 hectares with a yield of 1 791 metric tons of opium (Lintner

1994, p. 317; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2005, pp. 3-4). Then, after the peaks

of the mid-1990s, opium production fell slowly reaching a low of 310 tons in 2005 and 320

tons in 2006 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2014, p. 59). This has been

attributed to the opium bans in Kokang, Wa and Mongla as well as increased eradication

efforts by the government (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2014). This downturn

in production was only temporary and opium production today has now more than doubled

to 870 tons (See Figure 2.) (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2014, p. 43). This

opium is then refined into heroin and trafficked along routes through China, Thailand and

Laos for consumption in regional markets and also further abroad in Australia, New Zealand

the USA (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2013). Furthermore, although the UWSA

31

no longer appears to be cultivating opium on its territory, it is still believed to be a major

drug trafficking organisation and is sanctioned by the USA (Office of Foreign Assets Control

2014, p. 7; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2014, p. 79). The UWSA is implicated

in the trade in ATS and believed to be a major manufacturer of ATS (UNODC Global SMART

Program 2010). The expansion in the drug trade from solely opiates to ATS also indicates a

noteworthy shift in the dynamic of the illicit narcotics trade.

The trade in ATS originating from Myanmar has grown considerably in the past 20 years. The

trafficking of ATS is believed to have begun during Khun Sa’s final years before his surrender

to the state (McCoy 2003, p. 439). His power declining, Khun Sa, began the manufacture of

ATS to supplement opiate sales (McCoy 2003, p. 439). ATS have the advantage of being

purely synthetic drugs. They are not reliant on farmers or crop yields and are made in small

mobile laboratories and bamboo shacks to avoid detection (Boot 2012; UNODC Global

SMART Program 2010). The trade in ATS has spiked dramatically and is now a major narcotic

of export. China is a major destination for methamphetamine from Myanmar with

authorities in Yunnan, on the China-Myanmar border, seizing 9 tons of tablets in 2012

(UNODC Global SMART Program 2013, p. 64). In Thailand, Myanmar is the main source of

methamphetamine in the country (UNODC Global SMART Program 2013, p. 132). These

drugs are smuggled easily across the highly porous borders that exist between Myanmar,

Thailand and China (McDonell 2013). As the Chinese and Thai authorities become more

vigilant, drug traffickers are beginning to use Laos as an alternate smuggling route (UNODC

Global SMART Program 2013, pp. 64, 132). When comparing the seizure numbers of

Thailand and China to that of Myanmar, the amounts seized are disproportionate. Only 18

million pills were seized in Myanmar in 2012, this is far outweighed by the excessive

32

amounts seized in China and Thailand (UNODC Global SMART Program 2013, pp. 64, 98,

132). ATS are a rapidly evolving and growing part of the Myanmar’s thriving drug trade.

The market for illicit narcotics has a long and sometimes violent history in Myanmar. The

farming of opium to support various rebellions soon gave way to the manufacture of heroin.

The government, ethnic armies and other various politically aligned movements began to

use the drug trade to finance their conflicts and counter-insurgency operations. This often

simply resulted in the groups involved becoming more concerned with drug trafficking than

the aspirations they had initially taken up arms for. This has resulted in Myanmar becoming

a major epicentre for drug production in the region. Being a major centre for drug

production could ostensibly have serious implications for state security. This thesis now

examines the state security-drug trade nexus and determines the extent to which state

security is impacted.

Securing the state with drugs

As discussed earlier, the Burmese state has had a complex but long relationship with the

narcotics trade. This relationship has often cycled through periods of co-option and

rejection as has suited the needs of the state at the time. During the 1960s and 1970s, the

central government instituted the formation of the KKY to combat the ethnic armies and

CPB that at the time threatened the state. The government used the enticement of freedom

to trade in opium as an incentive for warlords to swear allegiance to Rangoon (Lintner 1994,

p. 188). This was taken advantage of by some warlords who initially agreed until they had

enough arms to continue fighting once more (Lintner 1994, p. 188). Others, such as Khun Sa

and Lo Hsing-han, did discharge their duties and fought against the CPB (Lintner 1994, pp.

33

189-90). The impact that the KKY units had on protecting state security overall appears to be

negligible. Lo Hsing-han was routed when fighting the CPB and Khun Sa arrested for high

treason (Lintner 1994, pp. 202, 11). The years of the KKY did little more than foster the drug

trade and help it expand. It also made powerful figures out of Lo Hsing-han and Khun Sa.

Despite this, the government’s use of the KKY and drug trade had been a novel idea and

useful experiment.

During this same period, neighbouring countries fostered the drug trade to create instability

in Burma. Key figures in the drug trade were often well connected to the Thai military,

which supported their activities (Lintner 1994, p. 249). This was done by the Thai security

forces in order to create a buffer along the Thai-Burma border (Lintner 1994, p. 255). This

perpetuated the instability and ethnic conflict in Burma at the time. Warlords were free to

engage in the heroin trade, without interference from Thailand, meaning they had free reign

over the territories they controlled. The situation in Laos also contributed to the instability.

The military’s iron grip on the heroin trade in Laos fomented increased demand for opium

from Burma (McCoy 2003, p. 356). With this increased demand came increased trade, often

in exchange for weapons for the ethnic armies to continue their rebellion (McCoy 2003, pp.

344-5). The tacit approval and direct involvement of neighbouring countries in supporting

the transnational drug trade diminished state security. Eventually, as is the nature of the

drug trade, this situation changed.

Following the political turmoil of the late 1980s and early 1990s, Myanmar set out to once

more co-opt the drug trade. A key focus of the new government, SLORC, was to end the

continuous conflict in its border regions (Lintner 1994, p. 297). The government called on Lo

Hsing-han to act as an intermediary and establish ceasefires with the remnant factions of

34

the CPB (Lintner 1994, p. 297). The SLORC promised increased development and economic

opportunities to the various armies however, most importantly, they promised the freedom

to engage in the narcotics trade (Ball 1999, p. 3; Lintner 1994, p. 299). The majority of the

armed ethnic resistances signed up for the ceasefires including the larger groups such as the

Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO), the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N) and the UWSA

(Kramer et al. 2014, pp. 27-8). Rhetoric from Yangon soon changed from branding the ethnic

army commanders as ‘drug traffickers’ to ‘leaders of the national races’ (Lintner 1994, p.

298). This also represented a departure from the previous tactic of trying to control the

lands by purely military force (Meehan 2011, p. 396). Although some rebel groups refused

to participate in the ceasefire agreements, the Myanmar government successfully quelled

much of the previous violence that had existed along its borders (Meehan 2011). These

concessions granted for increased state security were not without a price for the ethnic

insurgents.

The tatmadaw did not allow complete carte blanche for the signatories of the ceasefire. In

2009 the junta announced the creation of Border Guard Forces (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 31).

The expectation was for all ceasefire groups to transform into small units under the

command of the tatmadaw and include a contingent of Burmese Army forces (Kramer et al.

2014, p. 31). This would break the ethnic identity of the groups and assimilate them into the

wider military machine. Only some of the smaller groups agreed to this change and all of the

larger groups declined (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 31). Following the refusal by the KIO, SSA-N

and UWSA, the tatmadaw began to apply pressure to these groups and launched attacks

(Meehan 2011, p. 397). Of those that agreed to the proposition, they have been free to

continue their activities in the drug trade (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 31; Meehan 2011, p. 397).

35

The fact the main opium producing areas in northern Shan State are under government

backed militia control serves to illustrate this point (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 32). Meehan

(2011, p. 397), has termed this the ‘limited access order’, whereby the government uses the

drug trade as a tool for co-option and coercion to maintain state security.

The tatmadaw maintains strict control of the conditions under which these groups may

carry out their business. New ceasefires after the transfer of power to the new government

in 2011 have allowed large groups like the UWSA to continue their illicit activities; smaller

government backed militias and armed groups have also continued (UWSA 2014; Kramer et

al. 2014). Tentative peace treaties between the UWSA, SSA-N and Myanmar government

have also included clauses to cooperate on counter-narcotics measures (SSPP/SSA-N

Government Preliminary Peace and 5-point Peace Agreement 2012; UWSA Government 6-

point Union-Level Peace Agreement 2012). Given the primacy of the military in these areas

and their involvement with the trade, it is uncertain what such agreements will bring.

Nonetheless, the adeptness of the junta in manipulating the drug trade to its benefit is

apparent.

The military junta has also generated significant profits from the drug trade and has used

this to enhance state security. There are numerous ties between business, government, the

tatmadaw and high profile drug traffickers (Jones 2013; Lintner 2000; Meehan 2011). In the

1990s, many drug traffickers started businesses in order to launder money within Myanmar

with the junta’s blessing (Meehan 2011, p. 391). These businesses also receive highly

lucrative government contracts and business permits (Meehan 2011, p. 391). Two notable

examples of this are the Asia World Company, founded by Lo Hsing-han and now run by his

son Steven Law, and the Hong Pang Group, run by Wei Hseuh-kang, commander of the

36

UWSA’s Southern forces and a former associate of Khun Sa (Lintner 2000, pp. 20-1; Meehan

2011, p. 392). Both Steven Law and Wei Hseuh-kang have been indicted in the USA on drug

trafficking charges and Wei is also wanted in Thailand (Meehan 2011, p. 392; Office of

Foreign Assets Control 2014, p. 4). Yet both men still enjoy the confidence of the

government and are even protected from international scrutiny (Lin Thant & Martov 2014;

The Irrawaddy 2003).

Many of the groups involved in the trafficking of narcotics also own businesses. These are

used to launder money through links with government owned companies, such as the Union

of Myanmar Economic Holdings (UMEH) and the now defunct Mayflower Bank (Meehan

2011, p. 391; U.S Department of the Treasury 2012). In 1996, the US Embassy in Yangon

reported a $600 million discrepancy in financial in-flows in Myanmar, $200 million of which

were used for defence expenditure (Lintner 2000, p. 20; Meehan 2011, p. 398). This was

reasoned to have originated from the drug trade, most likely from levies on laundering

money, as Myanmar lacks any other source of income that could generate such large illicit

profits (Lintner 2000, p. 20; Meehan 2011, p. 398). This demonstrates clear links between

the narcotics trade and the tatmadaw. The use of laundered money in Myanmar’s economy

and on defence expenditure is a clear demonstration of the tatamdaw’s ability to use the

drug trade to ensure state security.

The Golden Triangle drug trade has been a concern for the security of the state in

Burma/Myanmar. In the past, it has been used by neighbouring nations to foster an insecure

state. Burma’s early attempts at using the drug trade to guarantee state security were

ineffectual and actually heightened state insecurity through the creation of high profile drug

traffickers out of state control. Later attempts at co-opting the drug trade have proven more

37

successful. Myanmar has even turned failure into success by using figures from the failed

KKY initiative in a successful bid to gain ceasefire agreements. The tatmadaw has ensured

security by creating a limited access order to the narcotics trade. However, some larger

groups have been resistant to this and there is now some instability and conflict again in

these regions.

Money from the drug trade has been used to strengthen the defence capacity of the military

and build the state. The current state of security in Myanmar is largely positively affected by

the presence of the illicit narcotics trade. While state security may be ensured by the drug

trade, human security is a much more complex issue, which this thesis will now explore.

Myanmar’s human security dichotomy

The human security-drug trade nexus in Myanmar is complex and varied. The cultivation of

opium provides a human security dividend to impoverished farmers by providing a level of

economic stability and security. This must be counter-posed with the issues surrounding

drug use in these areas and the associated health, political and economic implications they

entail. The massive amounts of money generated in this illicit trade also inevitably lead to

corruption, which only further degrades human security. This section examines these effects

of the drug trade and determines the extent of human (in)security resulting from the drug

trade.

When examining reasons for people’s involvement in the narcotics trade, insecurity is a

common factor. The vast majority of opium is farmed in areas where ongoing conflict has

stunted development and people, especially ethnic minorities, have been forced to move

into the less productive mountainous areas (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

38

2014, p. 45). Unable to cultivate sufficient rice for their needs in the highlands and with little

to no economic opportunities in the surrounding areas, many farmers turn to opium as a

cash crop (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 7; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2014, p. 56).

For many, this is the only way to ensure they are able to cover the food shortage they will

inevitably face during the year. Cash derived from opium is also commonly used to afford

access to education and health services (Transnational Institute & Paung Ku 2013, p. 3).

Opium is also used itself for medicinal purposes, religious ceremonies and personal use

(Kramer et al. 2014, p. 13). The trade in ATS though offers no such benefit. The labs are

small and mobile, and because ATS are completely synthetic, there is no involvement with

farmers (UNODC Global SMART Program 2010). So while the trade in opium provides a clear

human security dividend, ATS manufacture does not.

Economic insecurity is a prominent factor in the causes of opium farming. Land grabs are

commonplace in Myanmar, especially among the poor rural villages (Kramer et al. 2014, pp.

15-6). Land grabs have been exacerbated by China’s opium substitution program as it

privileges large companies that subsequently appropriate land from poor rural farmers

(Kramer et al. 2014, p. 16; Kramer & Woods 2012). This is commonly followed by forced

labour, dislocation of previous landholders and the importation of Bamar workers (Kramer

& Woods 2012, p. 48). This has led to migration of ethnic minorities in search of work and

claims that the central government is pursuing a policy of ‘Bamarisation’ of the ethnic states

(Keenan 2011; Kramer & Woods 2012, p. 48). As farmers do not know if or when they will be

dispossessed this prevents the farming of lower profit licit cash crops and promotes the

farming of higher profit illicit crops (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 16; Kramer & Woods 2012). There

are also a significant number of cases where farmers on productive land, growing licit crops,

39

have been forced off and into less productive areas where opium is the only option (Kramer

et al. 2014, p. 14; Kramer & Woods 2012). While most of the opium produced is then sold to

traders, some farmers keep an amount for use as an emergency savings fund (Kramer et al.

2014, p. 42). Here it can be seen that opium is used again as a survival strategy to provide a

modicum security in an otherwise insecure situation. Conversely, China’s crop substitution

program only exacerbates the insecurity.

However, the production of large quantities of drugs has led to significant issues

surrounding the levels of drug use in Myanmar. Opium usage can frequently become

problematic, especially in rural opium farming villages (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 42). Usage

rates in opium growing villages are 1.9 percent, which is more than six times higher than

non-growing villages (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2014, p. 75). Similar trends

are seen in all drug use, with opium cultivating villages having consistently higher rates of

heroin and ATS usage; this is also increasing (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

2014, p. 75). Drug use in these villages is having a considerable impact on human security.

For example, children drop out of school to support parents with opium habits (Kramer et

al. 2014, p. 42). This affects the future generations in Myanmar, as without education, they

will suffer from the same limited choices their parents had and the cycle is likely to

continue. It may also lead to discord among the community as drug users are often

stigmatised or even expelled from villages (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 95). Familial breakdowns

are also common with partners separating over drug use issues (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 47).

There is also a loss of pride and hope for the future generations. As one Kachin man stated,

‘the young people who are using heroin are no benefit to our nation and future. If we lose

our Kachin national pride, we also lose our Kachin politics’ (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 41). This

40

statement, combined with the other effects discussed, are reflective of the growing human

insecurity associated with the drug use in these areas.

Of the many problems of human insecurity associated with drug use, health insecurity is

perhaps the most important. Blood-borne disease and sexually transmitted infections are

common health problems that affect drug users, particularly injecting drug users (IDUs)

(Jarlais 2010; World Health Organisation 2014a; Xiao et al. 2007). HIV and Hepatitis C

infections are rampant throughout Southeast Asia among the IDU population. It is estimated

there are 30 million people in Southeast Asia infected with Hepatitis C and some 60-80

percent of IDUs in Burma and China are infected (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 49; World Health

Organisation 2014b). IDUs are also at serious risk of contracting HIV and HIV prevalence

among IDUs in Myanmar is estimated at 18 percent (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 78; UNAIDS 2013,

p. 49). These diseases are often spread to the general population as well through sex

workers who are IDUs themselves or have IDU partners (UNAIDS 2013, p. 50). Recent

changes in policy, to focus on harm reduction, have slowed rates of new transmissions of

HIV among IDU (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 78; UNAIDS 2013, p. 49). HIV infection is also closely

linked with an increased incidence of tuberculosis in Myanmar, compounding the health

issues already faced by the IDU population (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 78). These health issues

can have detrimental outcomes on social cohesion and the cost to society. This is especially

the case when these issues disproportionately affect ethnic minorities, as is the case in

Myanmar (Hayes & Qarluq 2011; Kramer et al. 2014).

The problem of corruption is a major issue in Myanmar today. Corruption is widespread

throughout the country and even approaches the upper echelons of power (Kramer et al.

2014). It is also heavily influenced by the huge sums of cash available as a result of the drug

41

trade (Kramer et al. 2014). Police have been reported to seek out positions that will offer

opportunities to extort bribes (Selth 2012, p. 70). Indeed, the extortion of bribes from

opium farmers, drug users and drug sellers by police is commonplace in many areas in

Myanmar (Kramer et al. 2014, pp. 22, 52, 84). One police office in northern Shan State was

quoted as saying, ‘many police are becoming thieves…[and] accepting bribe[s] a lot and I am

also doing that, because we do not have enough salary’ (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 84). The

quote also serves to highlight the reasoning behind some corruption. Economic insecurity is

a recurrent theme and here it perpetuates further insecurity. People are also denied the

right to legitimate representation. Corruption has led to officials exchanging rights to grow

opium in return for support at the ballot box (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 32). This kind of

corruption among officials and police officers creates a situation of political and economic

insecurity among those involved with narcotics.

People cannot be sure if or when bribes will no longer be enough, leading to uncertain

futures. As opium farmers, drug users and drug dealers consistently act in contravention to

state laws, they are effectively living outside the state system. Farmers may face having

their fields eradicated should they be unable to pay sufficient bribes to local police officers

and officials (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 64). The army has also been directly involved in

corruption as well. One former captain spoke of his time in Lashio, Shan State saying, ‘we

were happy to be sent to Shan State during opium harvests because there was more money

to share when we made confiscation from the traffickers’ (Cliff 2013). The inability of drug

users and dealers to pay bribes can often lead them into mandatory treatment facilities

where they are commonly used as forced labour and denied basic human rights (Kramer et

al. 2014, p. 83). Some ethnic political groups, such as the KIO, have also been involved in

42

these compulsory treatment camps (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 75). This forces those who

already face considerable economic insecurity further into poverty, making them reliant on

the illicit trade. These kinds of corruption, and the inherent threat of increased insecurity,

serve to reinforce people’s situation as existing outside the state system.

A loss of principles by some organisations due to the influence of the drug trade is also

marginalising people. Some ethnic armies have become corrupted by the influence of

money from the drug trade (Kramer et al. 2014, p. 27). The Palaung militia is an example of

a group claiming to represent the community yet in reality it is more concerned with drug

profits. A Palaung villager, Nyee Kyaw, was forced to join the militia when he was 15 (Cliff

2013). In an interview for the Irrawaddy magazine he states, ‘I hated the militia. It never

worked for the community, only for business’ (Cliff 2013). These groups are no longer

capable of expressing the aspirations of the people they once represented or providing the

political security people once sought. These minorities are hence denied any legitimate

recourse. Corruption, which preys upon those involved in the drug trade, clearly

exacerbates the situation of human insecurity that many already live in.

There is an inherent dichotomy in the relationship between human security and the

narcotics trade in Myanmar. The growing of opium is a boon to farmers who have little to

no other options available to gain economic and food security. However, with this comes

the social cost of drug use and corruption. The use of drugs is leading to serious health

implications and a loss of social cohesion. Similarly, corruption is denying people political

and economic security. In addition, both of these are linked to a gradual loss of ethnic

groups’ abilities to express their aspirations. The ability of ethnic groups to have their voices

43

heard and become part of a new, inclusive and democratic Myanmar is essential if the

democratic transition is to be successful.

Conclusion

The drug trade in Myanmar is a widespread and complicated issue. There are many actors

involved including ethnic armies, militias and the military of Burma/Myanmar itself. The

participation of security services from surrounding states such as Laos and Thailand create a

transnational security issue. This has impacted upon the security of the state at various

times in Burma/Myanmar. Ethnic armies have used revenues generated from drug

trafficking to continue their struggle against the central government. Similarly, Thai security

forces have abetted the trade to create a buffer zone along their border. However, the

tatmadaw have been quite successful in using the drug trade to prosecute their agenda for

a secure state. The creation of a limited access order has enabled the tatmadaw a certain

degree of control over drug trafficking and separatist forces. The military has also raised

money to fund itself through allowing known drug traffickers to launder money and create

legitimate businesses.

In relation to human security there exists a dichotomy. The income generated for poor

farmers by farming opium help maintain food security and give access to education and

health services. The social impacts of drug use decrease human security. HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis

C and B, and tuberculosis are all major health problems associated with drug use in

Myanmar. Corruption, induced by the money flows inherent in the drug trade, is serving to

deny people political and economic security. State involvement, corruption and human

44

insecurity could all potentially affect democratic transition. This thesis will now analyse the

current the democratic transition in Myanmar.

45

CHAPTER 3

MYANMAR’S DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION

This chapter analyses Myanmar’s current democratic transition. Firstly, this chapter outlines

Burma/Myanmar’s history of democracy and dictatorship. Without first examining the long

history of conflict and failed attempts at democracy it is not possible to construct a

thorough analysis of the current democratic transition. Secondly, this chapter analyses the

nature of the current democratic reforms. It demonstrates the recent changes to

Myanmar’s political system are a positive step. However, there are still serious flaws that

must be overcome such as the legacy of previous power structures and inherently

undemocratic nature of the constitution. Finally, the inclusiveness of the current transition

is examined. This chapter concludes that the democratic system, as it currently stands, is

not sufficiently representative and inclusive; failing to address the issues of marginalisation

that have long plagued the country.

A history of failure

Burma officially gained its independence from British rule on 4th January 1948. From the day

of its independence it has faced problems in reconciling the many demographics its borders

encompass. Armed rebellion had even started the year before independence in Arakan state

(Keenan 2011, p. 56). This was followed post-independence by ‘leftist’ and further ethnic

rebellions (Keenan 2011, p. 56). Although Burma was a democracy, after independence it

struggled to reconcile the desires of ethnic minorities (Holliday 2011; Keenan 2011). As

conflict continued the government became increasingly brutal yet further unable to find a

46

suitable resolution to the conflicts (Keenan 2011). This ultimately led to the tatmadaw

positioning itself as the sole institution capable of maintaining the cohesion of the state

(Holliday 2011, p. 45). The failure to adequately provide for the aspirations of ethnic

minorities and build a strong state led to the failure of Burma’s democracy and

entrenchment of military power for decades since (Holliday 2010, p. 112; 2011).

The 4th of March 1962 marked the official end of Burma’s democracy as General Ne Win

assumed power in a coup. Ne Win legitimised his actions and subsequent rule by citing the

need to maintain a unified Burmese state (Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung 2003, p. 444). The

1947 constitution was rescinded and Ne Win began to institute his ‘Burmese way to

socialism’ (Holliday 2011, p. 47). The tatmadaw became the state builder, responsible for

maintaining territorial integrity and moulding government institutions (Holliday 2011, p. 47).

This led to brutal repression of any dissent and military actions against the ethnic armies