Substance Abuse among Rural and Very Rural Drug Users at Treatment Entry*

Drug-Releated Offenses and the Structure of Communities in Rural Australia.2002.Substance Use and...

Transcript of Drug-Releated Offenses and the Structure of Communities in Rural Australia.2002.Substance Use and...

DRUG-RELATED OFFENSES AND THE

STRUCTURE OF COMMUNITIES IN

RURAL AUSTRALIA

Joseph F. Donnermeyer, Ph.D.,1,*

Elaine M. Barclay, M.S.,2 and

Patrick C. Jobes, Ph.D.3

1Department of Human and Community ResourceDevelopment, The Ohio State University, Columbus,

Ohio, USA 432102Senior Project Office, Institute for Rural Futures,

University of New England, Armidale,New South Wales, Australia 2351

3School of Social Science, University of New England,Armidale, New South Wales,

Australia 2351

ABSTRACT

This article examines the relationship of drug use with thesocial and economic characteristics of rural communities inNew South Wales (NSW), Australia. Data is derived from the1996 Australian Census of Population and Housing, and dataon drug-related offenses from the NSW police between 1995and 1999. Arrest rates for breaking and entering, assault, and

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 637] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

637

Copyright & 2002 by Marcel Dekker, Inc. www.dekker.com

*Corresponding author. Department of Human and Community Resource

Development, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA 43210, Fax:614-292-7007; E-mail: [email protected]

SUBSTANCE USE & MISUSE, 37(5–7), 637–666 (2002)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

638 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

vandalism showed statistically significant associations acrosstypes of rural communities, but drug-related arrests variedconsiderably less. The widespread, relatively-even distributionof drug arrests in rural NSW suggests that the underlyingcauses of drug-related violations are unique when comparedto other types of crime. [Translations are provided in theInternational Abstracts Section of this issue.]

Key Words: Drug arrests; Rural; Social disorganizationtheory; Australia; Crime; Community indicators; Harmminimization

INTRODUCTION

This article examines variations in the official police rates of drug-related offenses among rural areas and towns in New South Wales,Australia. Research on substance use among rural populations hasbecome more extensive during the past 10 years.[1–4] In countries like theUnited States, rates of substance use among rural and urban adolescents aresimilar,[5] although there is some evidence that youth from the smallest andmost remote communities have lower prevalence rates.[6,7] The etiology ofsubstance use in terms of personality, family, peer, and school-related fac-tors appears to be largely the same among rural and urban populations.[5,8]

However, the situation with respect to community-level indicators is lesswell known.[9] The kinds of community factors associated with drug-relatedcrimes and substance use in general have only rarely been tested in eitherrural or urban settings.

The study of substance use within rural community environments hasan advantage insofar as there is a larger pool of rural places than there areurban, and there is more variability in the social and economic structure ofrural communities.[4,9] This methodological advantage is especially evidentin Australia, because rural communities there are so geographically sepa-rated and so diverse that distinct types of community structures are evident.Australia has a small (19,000,000), highly-centralized (88% live in placeswith more than 40,000 residents) population, distributed in an immense(approximately the size of the 48 contiguous United States) geographicarea.[10] This uniquely Australian combination of factors has created largenumbers of relatively isolated and socially autonomous communities,located long distances (uncontaminated) from each other, and from metro-politan areas.[11] This article examines possible variations in rates of drug-related offenses across characteristics of rural communities. It tests for the

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 638] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 639

relationship between various social and economic community-level factorswith drug-related offenses. In addition, through cluster analysis, it developsa typology of rural communities. Finally, it tests the extent to which rates ofdrug offenses vary between communities, and compares this variation withrates for other crime types.

DRUG-RELATED ARREST DATA

In the past, psychological and sociological studies of illicit substanceuse have relied on three primary sources of information. The most commonof these is the survey or questionnaire that solicits self-report informationfrom subjects about their attitudes and behaviors about using substances.The Monitoring the Future research project, conducted by the University ofMichigan,[12] and the American Drug and Alcohol Survey[13] are two widely-used surveys that collect self-report data. The second primary informationsource is observational research that investigates the context in which sub-stance use occurs. An example would be a qualitative study of needle-sharing among heroin addicts.[14,15] The third source of information isthat obtained through analysis of urine, hair, and other physical evidence.Some social scientists have used this information to cross-validate self-report studies,[16] while others have combined physical evidence with variousmeasures of attitudes and behaviors about risk-taking activities amongsubjects.[16,17] Another source is medical examiners reports of deaths fromoverdoses in emergency rooms.

Little-used is a fourth source of information—official police statisticsthat record the level of criminal activity in the possession, dealing, andmanufacture of illicit substances. Admittedly, there is a great deal of con-troversy surrounding the legalization or normalization of some substances,in particular, marijuana. Closely related to this controversy is the role ofthe police, as an agency of the state responsible for control and enforce-ment of illicit drug supplies. Some scholars have argued that official policestatistics are little more than artifacts of selective attention by the police tosubstance use and, consequently, are inappropriate for social scienceresearch.[16,18] There are other problems, also. The police know about arelatively small proportion of all illegal activities associated with substanceuse. However, this same criticism can be made about police statistics formost other types of crimes, yet a large share of social science research oncrime during the previous five decades has relied on police crime andarrest data. Dekeserdy and Schwartz[18] summarize how each sourceof data about substance use has its share of weaknesses and strengths.The debate continues over the validity of self-report surveys about

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 639] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

640 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

substance use, although they are an effective and economical way tocollect data.[19]

Observational studies are praised for their ability to provide rich,contextual data, even as they are criticized for their inability to generalizebeyond the specific case or location in which the research was conducted.Data from physical evidence offers a highly reliable and valid measure ofwhether an individual is using drugs. However, it is less used than othercollection methods because it is usually limited to incarcerated or otherspecial groups that are not representative of the general population, andthe data collection cost of securing samples in order to draw a representativesample of the population is prohibitive.[16,18]

One, largely unrecognized, advantage of official police statistics onsubstance use is that the locality or jurisdiction where the arrest was madeis recorded, which allows examination of variations in rates of drug-relatedcrimes across a variety of community settings. The concept of communityhas taken on added importance in the study of substance use and misuse.[20]

In particular, the community is seen as an important source of social parti-cipation and socialization. Regardless of the influence of television and theInternet, it is in local neighborhoods that opportunities for illicit substanceuse, as one aspect of deviant behavior, are made available.[21] It is at specificplaces that learning about substance use takes place.[22] Diversity of norms,both within and between communities, concerning alcohol, marijuana, andother drug use, influence individual behaviors through differences in theapplication of sanctions by local social control agencies, including thepolice and schools. Informal relations between members of the communitycan vary from the higher density of acquaintanceship found in many ruralcommunities, to the greater impersonality and anonymity commonly associ-ated with large metropolitan centers.[23]

DRUG USE IN RURAL AUSTRALIA

Although considerable research has been conducted on substance usein Australia, relatively little has focused on rural drug use.[24] That whichhas been done has been limited to alcohol and cannabis. Some nationallevel data suggest that alcohol use and alcoholism are inversely related tocommunity size, that is, higher rates in smaller communities.[25] This samestudy noted no differences in reported levels of cannabis use between ruraland urban Australians. Other researchers have observed that ‘‘heavy’’alcohol consumption among men at pubs and with various sporting activ-ities has historically been part of rural Australian culture.[26] Long-term

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 640] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 641

rural cannabis use has been explained by the same factors that lead toalcohol misuse.[27] Users were in their 30s, had above-average education,and average employment rates. Although drug-related violations wereuncommon in the O’Connor and Gray[28] case study of Walcha, theyreported that drunk-driving charges were more common in rural than inurban Australia. Likewise, Dempsey’s[26] study of a small Australian townfound frequent marijuana production, trafficking, and use among severalgroups in the community.

A report on drug- and alcohol-user intervention services in rural andremote Australia[24] found a reluctance among residents to acknowledge aproblem with drugs and alcohol. Those with such a problem are seen to bedifferent and become alienated from the community. Therefore, the oppor-tunities to facilitate change for an individual with an alcohol- or drug-use-related problem in rural communities are significantly less than in urbancenter. For the individual who is seeking support to change, often the onlyviable option is to leave and go where they are not known. For many, thisseparation is unacceptable, so they stay and maintain their harmful beha-vior, with subsequent consequences. The authors suggest that because ruraland remote communities respond in a different way to drug- and alcohol-related issues than do their city counterparts, programs and services shouldaddress the specific needs of these communities. However, small commu-nities cannot afford the range of specialist services required for the treatmentof alcohol- and other drug-related problems that are readily available inlarge cities. Health workers in rural communities often have to address amuch broader range of drug- and alcohol-related problems than healthworkers in the city, but have less access to training and support.

Wood[29] found the mainstream health services are particularlyinadequate in rural areas for people with both alcohol- and drug-relatedproblems, and mental disorders. There was a lack of collaboration betweendrug- and alcohol-user treatment staff and mental health workers,general practitioners, hospital staff, and generalist health workers. Policeinexperience and problems with isolation are also a concern.

Williams[30] found that between 1988 and 1998, use of illicit drugsincreased in regional Australia by 77% for heroin, 131% for amphetamines,37% for cocaine, and 47% for cannabis. Compared to metropolitanAustralia, however, there were fewer drug users in regional Australia in1988. The subsequent rates of growth and durability of drug use sincethen have also been lower in regional Australia. Consequently, the gap inrates of drug use between regional and metropolitan Australia grew over theperiod rather than diminished. Williams[30] concluded that it is unlikely thatrates of drug use in regional Australia will contemporaneously match thosefound in metropolitan areas in the near future. However, illicit drug use is

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 641] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

642 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

increasing in regional Australia; while the current levels are lower than thosefound in metropolitan Australia, they approximate rates observed in thecities just a few years ago. Williams maintains that the lessons learnedfrom the response to drugs in metropolitan areas should be adopted earlyif regional Australia is to avoid the levels of drug-related social disruptionevident in the cities.

A review of the needs of heroin users in rural Victoria[31] found thatthe increased availability and use of heroin in country areas is complicatedby the acute shortage of methadone prescribers and dispensers in ruralVictoria. The number of patients participating in methadone programshas increased steadily since 1985 to over 5300 in 1998, and the waitinglists exceed the number of places available. Daily methadone dosing isprovided through local retail pharmacies, or through rural hospital phar-macies or outpatient departments. However, many rural patients do nothave a local methadone general practitioner prescriber or pharmacist dis-penser. The distance that rural patients have to travel can be great. Stickingto set dispensing appointments and meeting employment commitments canbe difficult. In small communities, where there is no public transport, thecosts associated with travel can be prohibitive. The difficulty in obtainingmethadone doses has led to recidivism and lost opportunities to intervene,treat, and minimize harm for patients.

Darke[32] examined the coroner’s files of all 188 heroin-related fatal-ities that occurred in regional New South Wales between 1992 and 1996.There was a significant increase in fatalities, rising from 23 deaths in 1992 to53 during 1996. The mean age of cases was 31.5 years, 83% were male, andthere were no significant trends in demographic characteristics of cases overthe study period. The median blood morphine concentration of cases was0.39mg/1 (range 0.05–4.5mg/1). Alcohol was detected in 50% of cases, andbenzodiazepines in 29%. There were large regional variations in toxicologyresults. Compared to Sydney metropolitan cases, regional cases had a highermedian blood morphine concentration, were less likely to have cocainedetected, were more likely to have died in a home environment, and tohave been born in Australia.

Other studies have identified regional differences in drug use. TheVictorian Injecting Drug Users Cohort Study in a comparison of injectingdrug users from rural Victoria and the city of Melbourne[33] found numer-ous differences in behavior and serology. The primary drug for most ruralusers in the Western District of Victoria was amphetamines, whileMelbourne users preferred heroin. Injecting and sharing frequencies weremuch lower in the rural sample. Hepatitis C antibody prevalence at first testwas significantly higher in Melbourne users, although this was clearlyrelated to the difference in primary drugs; conversely, incidence among

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 642] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 643

Western District amphetamine injectors was 16.2 per 100 person-years (py)(during 18.5 py), yet no conversions occurred in metropolitan amphetamineinjectors in 29.8 py. Western District users were less educated, and morelikely to be unemployed and of aboriginal descent than metropolitan users.The findings have implications for the delivery of relevant health services. Ofparticular concern is the possibility that hepatitis C has been spreadingrelatively rapidly among rural users.

Dunne[34] examined patterns of drug use within a sample of 507students aged 9–13 years in primary schools in 19 that had high propor-tions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Four schools werelocated in metropolitan Brisbane and three in North Queensland. Thestudy found significant numbers of these children had started to experi-ment with ‘‘recreational’’ drugs. Twenty-two per cent had attempted tosmoke at least one cigarette, 14% smoked in the preceding year, while 3%had smoked more than 10 cigarettes in their lives. Thirty-eight per centhad had at least one drink of alcohol, while 6% had smoked marijuanaat least once. There was no significant association between indigenous/nonindigenous background and risk of smoking tobacco or marijuana,while indigenous children were less likely than nonindigenous children toreport experience with alcohol. The authors concluded that the excessiveuptake of drug use among indigenous youth occurs in the early stages ofsecondary school. The finding underlines the importance of preventiveeducation in primary schools, especially for indigenous children, whoare posited to have a high risk of making the transition to drug use inadolescence.

Many studies in rural and remote Australia have focused upon theproblems of drug and alcohol ‘‘abuse’’ amongst Aboriginal people.[35,36]

Some studies have focused upon specific drug use in these populations,such as petrol sniffing,[37,38] Kava,[39] and ‘‘Pituri’’.[40] One of the majorhealth and social issues facing Aboriginal youth in Australia today is theuse of volatile solvents.[38] Petrol is most commonly used, primarilybecause of its ready availability (every remote community requires petrolfor vehicles, outboards, generators), cheapness (it can be stolen, or pur-chased in small quantities), and the rapidity of mood alterations its inha-lation produces. There have been some sporadic surveys and governmentenquiries, but little socially- or policy-oriented research has been under-taken to address the issue. This means that government policy (forexample, whether to criminalize sniffing) and health education efforts (toemphasize or minimize the potential dangers) have been hampered byscanty and ill-informed data. Petrol sniffing appears to be such an intract-able drug use and Aboriginal communities themselves find it virtuallyimpossible to dislodge.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 643] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

AQ1

AQ2

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

644 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

COMMUNITY STRUCTURE AND DRUGS

The community is the primary setting in which socializationoccurs.[22,41] Communities perform this function in three ways:

. First, communities are the locations for families, ethnic enclaves,

schools, churches, and other institutions, all of which are

influential sources of socialization. Resources within commu-

nities affect how these institutions perform this socialization

function.

. Second, communities provide opportunities, albeit very different

opportunities, for all members, young and old, men and women,

rich and poor, to participate in peer group activities. Close peers

are a primary source of socialization, influencing values, beliefs

and behaviors.[20] Differential opportunities for participating

in peer groups that teach and reinforce either conforming or

deviant behaviors often vary from locality to locality. Further,

these differential opportunities influence the ability of fami-

lies, schools, and even churches, to perform their socialization

functions.[42]

. Third, community norms are generally understood and supported

by most members, even when there is considerable disagreement

with community-established standards of behavior. Even citizens

who do not completely conform to the norms typically respect

them. For example, in rigidly ‘‘tee-totaling’’ (i.e., non-drinking)

Bible Belt communities of the United States, those who drink

do so primarily in the privacy of their own residences. To

drink publicly might jeopardize important social and economic

relationships with other members of the community who are

in strong agreement with the community norms against alcohol

use.[43,44]

Communities vary in the strength of norms against consumption ofillicit substances, and conversely, for tolerance of consumption, and underwhat circumstances this consumption may occur. In particular, rural com-munities may exhibit great variation because of their smaller size and theirrelatively greater (when compared to urban communities) density ofacquaintanceship, that is, of people knowing each other.[9,23,44] For thisreason, a study of the relationship between the social and economic struc-ture of rural places, and official rates of drug offenses, can provide valuableinsights about the nature of substance use and misuse at the communitylevel.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 644] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 645

Hypotheses

This article investigates how the diversity of smaller places in NSW isassociated with officially-reported drug-use-related activities. It presents atypology of rural communities developed from cluster analysis of dataderived from the Australian census, and examines variations in officials’rates of crime across these types. Social disorganization theory providesthe theoretical framework for examination of these clusters of communities,created through the census-based independent variables.[45,46] It is assumedthat the structure of communities creates the context for the socialization ofmembers, and the individual expression of various social behaviors andattitudes.[22,45,46] Places with higher levels of social disorganization havestructures that exhibit segmentation of human groupings along racial,ethnic, economic, and lifestyle dimensions. These places have lower densityof acquaintanceship and cohesion,[46] and families exist in less supportiveenvironments.[20] These conditions are presumed to be more crimino-genic,[21,47] allowing more opportunities for socialization of members intovarious deviant behaviors, including involvement with drugs.

The general presumption has been that places with smaller popula-tions have less social disorganization, hence less crime of all types, thanlarge urban places.[20,48,44] In fact, however, a case can be made that thephysical (and presumably social and cultural isolation) of some rural com-munities produces a context in which some crimes are more strongly associ-ated with social disorganization.[9,48] It is expected that measures of thesocial and economic structure of rural places will vary in ways congruentwith the tenets of social disorganization theory. Drug-related activities (andrates of other crime) will be higher in rural places with more social disorga-nization, and lower in places with less social disorganization. Places withhigher levels of residential instability, rapid population increases ordecreases, family instability, and unemployment are expected to havehigher reported levels of crime, including drug-related violations.

The Setting

The state of New South Wales is located in southeastern Australia. Itis almost 500,000 square miles in size, representing about 10.4% of the totallandmass of Australia. New South Wales is nearly twice the size of Texas,the second largest state in the United States. New South Wales is the mostpopulous state in Australia, inhabited by over 6.4 million persons. One-in-three Australians lives in New South Wales. The principal city is Sydney, ametropolitan area that includes over 4 million persons. Another 1.8 million

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 645] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

646 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

people live in the metropolitan communities of Newcastle, Wollongong,Tweed, and Queanbeyan.[10]

The rural portion of New South Wales is an immense, sparsely-settledregion. Most of its approximately 600,000 rural residents live in or nearsmall agricultural or coastal towns. Most areas in the interior region havegradually lost population since 1950, because of technological efficiency andthe decline in commodity prices associated with globalization. As in theUnited States, attendant centralization and consolidation of services haveexacerbated the loss, in spite of new agricultural and other natural resourcesdevelopments.[49] At the same time, coastal retirement and recreation(tourist) towns have been among the most rapidly-growing in Australia.

The environmental setting of the study area is extremely diverse,including mountains and table lands, deserts, river valleys and plains, andthe South Pacific Coast. Production systems within the region are corre-spondingly mixed. Cattle and sheep grazing occur throughout the region.Dry land and irrigated farming are widespread, ranging from subtropicalplantations in the east to immense grain and cotton farms in the west.Mining occurs where there are pockets of minerals. Natural recreationalsettings are widespread.

Agriculture is the traditional multigenerational economic base in mostrural Australian communities.[50] Agriculture in Australia is associated withfamily ownership and management of land resources. Agricultural practices,however, establish extremely different systems of employment. Dry land,small grain, agricultural areas usually had fewer tourist and recreationalattractions than mining or recreational areas. Mining in most towns isbased around a single corporate operation. Recreational/retirement areasusually lack the personal familiarity of stable communities.[23] Lackingcohesion and integration, they are more prone to many types of crime.

Methodology

Analyses have been conducted on New South Wales Bureau of CrimeStatistics and Research (BOCSAR) data sets. The BOCSAR data are com-plementary with other data sets, such as the Uniform Crime Reports(UCR). Although not as detailed, refined, or for as long a period as UCRdata, the BOCSAR data provide summaries of a range of crime types,including drug-related offenses. They have a large population and allowspecification of most of the variables contained in UCR data. TheBOCSAR data are large, reliable, and immediately accessible. They aresuitable for both exploratory analysis and hypothesis testing.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 646] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 647

The analyses used recorded crime data for 1996 to make them com-patible with the 1996 Census data. In addition to drug-related violations,three other measures of crime are analyzed: Break and Enter, Assault, andMalicious Damage. These measures are analyzed in order to examinewhether structural variations across different types of crime are occurring.They measure how drug-related violations fit into the diverse and complexnature of rural crime. Drug use is ubiquitous and receives considerablemedia attention as a motivating factor for other crimes.[51] Crimes againstpersons, including assault, receive disproportionate media attention, andelicit the greatest sources of fear among potential victims. Property crimesaccount for most criminal acts. Break and Enter is measured because itreflects an important type of property crime. Malicious Damage is measuredbecause it is neither theft nor personal assault, and occurs frequently andwithout economic incentives. In essence, it is violence against property.[52]

The sample is composed of LGAs (Local Government Areas) in NSWwith fewer than 50,000 residents. Each LGA is roughly analogous to acounty in the United States. A typical LGA consists of an incorporatedplace which functions as the economic, service, and cultural center, plus asurrounding hinterland of small villages, and open country, and agriculturalareas. The sample was selected to closely approximate a common officialdefinition of rural within the U.S. census, that is, non-metropolitan areaslying outside MSAs (Metropolitan Statistical Areas).

The findings represent an examination of data from a different nation,yet within demographic parameters similar to those often used in secondaryanalyses of rural crime in the United States. All LGAs outside metropolitanareas constitute the sample. The independent variables are drawn from the1996 Census of Population and Housing.[10] These variables have beenreported to be reliable indicators of social organization,[53] as well as pre-disposing factors to crime.[54]

To reduce the problem of high correlation between census variables,all variables were converted to proportions of the total population. Forexample, rather than using raw data to describe the population of peopleborn overseas, they were measured as their proportion of the total popula-tion. Arrest data were rates calculated per 100,000 population.

Prior to analysis, all variables were screened for normality, the pres-ence of outliers, multicolinearity, and linearity. All variables producedskewed data, as a consequence of the highly varied size and structure ofrural communities in Australia. The sparsely-populated unincorporatedfar West was a consistent outlier. As this area was considered unlikely tocontribute greatly to the understanding of crime in rural areas, it was deletedfrom the analysis. To correct for skewness in the data, logarithmic trans-formations were successfully performed with 11 variables. The remainder

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 647] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

648 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

proved unsuitable for transformation and therefore extremes among thevariables were recoded to bring the variables closer to normality.[55] Nocases had missing data.

Three statistical approaches tested the hypotheses. First, regressionanalyses tested the relationship between measures of social and economicstructure and drug use (and the other three crimes). Second, cluster analysisidentified distinct categories of communities according to those structuralcharacteristics, making measurement of their respective levels and types ofcrime possible by submitting them to analyses of variance.

All variables were transformed to z scores to equate the variables in themeasurement scales. A standard regression was conducted with the identifi-cation number for the LGAs as a dummy dependent variable, and the censusvariables as predictors. Inspection of the intercorrelations between variablesand calculations of variance inflation factors revealed no evidence of multi-colinearity within the data. Inspection of the standardized residuals histo-gram and the standardized scatterplot of predicted scores against residualscores revealed the presence of multivariate outliers and slight deviation inlinearity between variables. However, the majority of variables were fairlyevenly centered around zero. Three computations required removing oneextreme multivariate outlier, leaving a sample size of 121 for these analyses.Removal of further multivariate outliers, only produced more outliers. It wasdecided to retain all remaining outliers, as Tabachnick and Fidell[55] point outthat, with a large sample size, the standard error is reduced accordingly.Nevertheless, results must be interpreted with caution.

Four individual, standard multiple-regressions were performed toinvestigate those social and economic variables which were predictive ofhigher rates of drug-related arrests and arrests for the other three types ofcrime. Five additional regression equations were calculated for substanceuse which employed data for five years, 1995 to 1999, to account for thevariability in recorded drug-related offenses in any one year. Drug-relatedoffense categories included possession of drugs, dealing in drugs, marijuanaoffenses, all other drug-related arrests (without marijuana or drunk driving),and drunk-driving. Marijuana represent the majority of drug-related arrests,which warrants this additional breakdown. Although not included in thetotal drug-related arrests, drunk-driving was included because it represents atraditional pattern associated with rural Australia, and provides a potentialpoint of comparison.[28]

In all, 19 independent variables were used in the regression analyses.The independent variables for all the regressions included the census data of:average population growth; educational qualifications, namely tertiary qua-lifications (i.e., college), vocational skills and basic qualifications (i.e., highschool) and age at leaving school; home ownership and mobile home

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 648] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

AQ3

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 649

occupancy; migration, that is persons with a different address in anotherStatistical Local Area (which is equivalent to a LGA) since the 1991 census;unemployment; medium, individual, and household income; median age;family structure, namely married, separated, and divorced persons, andproportion of sole-parent families; proportion of indigenous people inthe community and the local labor force; and proportion of those bornoverseas.

Cluster analysis can be used as both a deductive and an inductivestatistical technique.[56] Deductively, it can test hypothesized relationshipsbetween independent and dependent variables. Inductively, it can identifyrelationships among variables. The inductive findings reflect relationshipsthat emerge from the data under the assumptions of the statistic with mini-mal interference by the investigator. As such, the analyses may be regardedas independent tests that corroborate or challenge previous findings.Analyses of variance were then calculated to measure the relationshipbetween the types of communities identified through cluster analysis andthe four measures of arrest.

Results

Table 1 shows the significant independent variables for each of thefour crime types, based on the regression analyses. The proportions of vari-ance (adjusted R2) explained ranged from approximately 20% to 45%, andare similar to the analyses performed by Rephann[57] on 1995 rural U.S.data. The regression analyses indicated assault was significantly predicted bya higher proportion of the population that were Aboriginal, a lower propor-tion of persons living in their own home, and in communities with less thanaverage population growth. Two of the predictor variables for breaking andentering were the same as for assault: a higher proportion of Aboriginals,and a lower proportion of persons living in their own home. Also, there wasmore breaking and entering in communities that had higher migration.Finally, important predictors of malicious damage included higher migra-tion, yet a lower than average population growth.

There was some overlap in the predictor variables for the first threeoffenses. In contrast, drug-related offenses were related to entirely differentvariables. Drug-related violations were higher in rural communities withhigher proportions of immigrants, lower proportion of persons married,higher median age, a lower proportion of persons with skilled vocations,and higher average population growth.

The significant relationships between the census variables and non-drug-related crimes followed classic patterns of social disorganization.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 649] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

T1

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

650 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 650] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

Table

1.

SignificantPredictors

inStandard

Multiple

RegressionofCensusVariablesonArrests

RatesforAssault,Breakand

Enter,MaliciousDamage,

andDrug-R

elatedOffenses

StandardR2

t-statistic

Assault

Proportionofindigenouspopulation

0.220

3.251,p<

0.002

R2¼0.537

Proportionofpersonslivingin

theirownhome

�0.141

�2.084,p<

0.04

Adj.R2¼0.449

Averagegrowth

ofcommunities

�0.141

�2.286,p<

0.04

R¼

.732,p<

0.0001

Breakandenter

Proportionofindigenouspopulation

0.184

2.507,p<

0.01

R2¼0.429

Proportionofpersonslivingin

theirownhome

�0.231

�3.153,p<

0.002

Adj.R2¼0.358

Personswithdifferentaddress

since

the1991census

0.147

2.006,p<

0.04

R¼0.677,p<

0.0001

Proportionofsole

parents

0.133

1.184,p<

0.07

Maliciousdamage

Personswithdifferentaddress

since

the1991census

0.175

2.290,p<

0.02

R2¼0.410

Averagegrowth

�0.175

�2.290,p<

0.02

Adj.R2¼0.299

Proportionofpersonsmarried

�0.141

�1.838,p<

0.06

R¼

0.640,p<

0.0001

Drug-relatedoffenses

Proportionofpopulationborn

overseas

0.170

2.083,p<

0.04

2.083,p<

0.04

Proportionofpersonsmarried

�0.182

�2.238,p<

0.03

Adj.R2¼0.196

Medianage

0.163

2.003,p<

0.05

2.003,p<

0.05

Proportionofpersonswithskilledvocations

�0.197

�2.418,p<

0.02

Averagegrowth

0.161

1.977,p<

0.05

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 651

Migration, unemployment, a disenfranchised population, and low propertyownership were typical measures of social disorganization. Drugs werepositively related to two indicators of disorganization, lower proportionof married persons, and higher proportion of immigrants. However, druguse was higher under conditions where social disorganization theory wouldpredict it to be lower, that is, higher age, skilled vocations, higher income,and population growth.

The second type of analysis included cluster analysis and analysis ofvariance to determine if there were significant differences between clusters bythe four types of crime. The clustering procedure itself resulted in commu-nities falling into six groups with similar geographical locations. The clus-tering substantiates that social structures across geographic areas wereaffecting the commission of crime. This effect guided the preliminarylabels that were applied to the clusters.

Cluster One: Large Urban Centers (N¼ 10, 8% of the Sample)

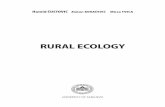

These LGAs were regional centers with an average population of33,251. They were scattered throughout the eastern half of New SouthWales (Figure 1), and several were very small in geographic size whencompared to most other rural LGAs. There were more females thanmales, an overall younger age group, and a higher rate of people movinginto the area, but only a slightly above average growth rate. These locationshad a higher level of education among the residents, less unemployment,and higher incomes. There were average numbers of people living in theirown home, but fewer couple families and more sole parents. There werefewer people married and a higher rate of separation and divorce. Therewere higher proportions of indigenous people (Aborigines) and of peopleborn overseas.

Cluster Two: Coastal Communities (N¼ 17, 13% of the Sample)

Most of the LGAs in this cluster were located along the coast. Theirmean population size was 27,925, slightly less than cluster one. There wereslightly more females than males, and an above-average median age, reflect-ing the large numbers of retirees in coastal regions. Average growth for thesecommunities was the highest of all clusters and there were greater numbersof in-migrants. There were higher proportions of skilled workers, averagenumbers of persons with tertiary and basic qualifications, and higherproportions of people who left school aged under 14 or 15 years.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 651] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

F1

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

652 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

Unemployment was the highest of all the clusters, with a correspondinglower than average income. There were high numbers of people living inmobile homes and fewer people living in their own homes. The proportionsof separated and divorced people were higher. Consequently, the propor-tions of sole parents were higher, and of married couples, lower. There wereaverage proportions of indigenous people, but higher proportions of peopleborn overseas.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 652] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

UnincorporatedFar West

Tweed

Newcastle

Sydney

Wollongong

Australian CapitalTerritory

Metropolitan areas andUnincorporated Far West*

Cluster 1: Urban Centres

Cluster 2: Coastal Communities

Cluster 3: Satellite Communities

Cluster 4: Larger Inland Communities

Cluster 5: Smaller Inland Communities

Cluster 6: Inland Farm Communities

*Areas excluded from the analysis

Figure 1. Map of New South Wales displaying the six types of nonmetropolitan

local government areas.

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 653

Cluster Three: Satellite Communities (N¼ 13, 11% of the Sample)

This cluster consisted of communities that lie close to the major metro-politan areas (>50,000) of New South Wales. The average population was8484. These communities had above-average growth rates and the highestproportion of in-migrants. The median age was below average, with moreyoung women, but more men in the 30 years and above age groups. Theresidents in this group had the highest level of tertiary qualifications andabove-average vocational skills and basic skills. Fewer people left schoolunder the ages of 14, 15, or 16 in these locales. Unemployment in thesecommunities was the lowest across all clusters. Consequently this clusterhad the highest median individual and household incomes. Family stabilitywas evident with fewer sole parents, more couple families, more peoplemarried, an average proportion of people who were separated, and fewerwho were divorced. More of the residents lived in their own homes andfewer in mobile homes. There were proportionately fewer indigenouspeople but more people born overseas.

Cluster Four: Larger Inland Communities (N¼ 23, 19%of the Sample)

Most of these communities were located just to the west of the GreatDivide Range. Their average size population was 11,046. They had above-average growth, but only average proportions of people moving into thearea. These communities also had higher proportions of males across allages. There were average proportions of tertiary-qualified and basic-skilledpersons, with above-average numbers of people with skilled vocations.These communities contained fewer people who left school under theage of 14, but more who left school under age 15 or 16. Unemploymentwas quite low and the median individual and household incomes were highin comparison to other clusters. The median age was also quite low. Therewere more couple families and average numbers of sole parents, and per-sons who were married, divorced, or separated. Slightly more of the resi-dents live in their own home, and average numbers of people lived inmobile homes. These communities had slightly below average proportionsof indigenous people, and slightly above average proportions ofpeople born overseas. This cluster had the highest number of personsemployed in the mining industry. The effects of stable, well-paid employ-ment undoubtedly contributed to many of the characteristics of thesecommunities.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 653] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

654 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

Cluster Five: Smaller Inland Communities (N¼ 29, 24%of the Sample)

Located even further inland (or east) than most of the communities inthe previous cluster, these LGAs were smaller in size (average populationwas 8115). Plus, rather than growing, they had the highest negative growthrate. Few people were moving into these areas. These communities had ahigher proportion of males in the 40–49 age range, but slightly more femalesin the other age groups. The median age was slightly below average.Education levels were also lower, with average proportions of people wholeft school aged under 14, 15, or 16 years. The unemployment rate wasslightly above average, while the median individual and household incomeswere low. The proportion of sole parents was above average; there werefewer couple families and married persons, but average rates of separationand less divorce. The numbers of people living in mobile homes was average,and there were slightly more people living in their own homes. These com-munities had the highest proportion of indigenous people and the lowestproportion of persons born overseas.

Cluster Six: Inland Farm Communities(N¼ 31, 25% of the Sample)

Most of the inland farm communities were located in the southern partof New South Wales. This group had an average population of 3982 andhad the highest rate of agricultural industry. Typical of small agriculturalcommunities, there were higher proportions of males across all age groups,and an above average-median age. There was a negative growth rate withfewer in-migrants. There were fewer people with tertiary or vocational skills,but average numbers of people with basic skills. The proportions of thoseleaving school aged under 14, 15, or 16 years were very high. Correspond-ingly, the income levels were the lowest across all clusters. Nevertheless,unemployment was below average. There were more couple families andmarried people, and more people living in their own homes and, correspond-ingly, less family breakdown. These communities had slightly below averageproportions of indigenous people and people born overseas.

A posthoc one-way multivariate analysis of variance was conducted tointernally validate the six-cluster solution and compare them across the fourtypes of crime. A significant multivariate difference was found among clus-ters (Wilks Lambda¼ 0.48163, approx F(25,418)¼ 3.63, p<0.001). Themultivariate effect size was 0.136. Therefore 14% of the variance between

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 654] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 655

the clusters can be explained by the difference in crime types. Posthocunivariate F-tests revealed significant differences between the clusters forAssault (F(5,116)¼ 4.99, p<0.001, n2¼ 0.177), Break and Enter(F(5,116)¼ 8.96, p<0.001, n2¼0.279), and Malicious Damage (F(5,116)¼5.32, p<0.001, n2¼ 0.187), but not for drug-related offenses. The latterfinding suggests that drug-related offenses are fairly universally distributedacross rural communities in New South Wales.

Figure 2 graphically displays the mean standardized score profiles forthe four crime types across each of the six clusters. Communities with rela-tively more social disorganization, especially large urban centers (cluster 1),coastal communities (cluster 2), and small inland communities (cluster 5),had higher than average assaults, burglary, and malicious damage.Communities with relatively more social disorganization, especially clusters4 (large inland communities) and 6 (inland farm communities) had lowerthan average crime. Satellite communities (cluster 3) had higher rates ofburglary, malicious damage, and drug-related offenses, but a level of assaultthat was nearly as low as found among inland farm communities.

Over all, drug-related offenses followed no logical pattern, based onsocial disorganization theory. In two of the three more socially disorganizedclusters (large urban centers and small inland communities), drug-relatedoffenses were below average and represented the lowest rates among the four

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 655] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

F2

Figure 2. Standardized crime rates by community clusters.

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

656 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

types of crime. Drug-related offenses were highest in the coastal and satellitecommunities, that is, areas with younger populations, higher than averagein-migration, and proximity to metropolitan areas of New South Wales.

To explore further the relationship of social and economic character-istics of rural Australian communities with drug-related arrests, a series of fiveregression equations was run for specific types of offenses. The dependentvariables were possession of drugs, dealing or trafficking in drugs, marijuanaoffenses, and all other drug-related arrests, except for marijuana, and drunkdriving. Drunk driving was not included into total arrests, but is included inthis analysis because of alcohol’s popularity in Australia and the strenuousefforts of police to control driving while under the influence of alcohol.

In each regression analysis, the same 19 independent or predictor vari-ables were used. Based on the adjustedR2, slightly over 23%of the variance inpossession offenses was explained (Table 2). Possession offenses were pre-dicted by a higher proportion of the population living in mobile homes andpersons born overseas, and a lower proportion of the population with voca-tional skills certification, that is, persons with degrees from technical colleges.Nearly 25% of the variance in arrests for cannabis offenses were explained.The same three independent variables were found to be statistically signifi-cant. Nearly 23% of the variance in dealing offenses was explained, but onlyone variable, a higher proportion of persons living in mobile homes, wasstatistically significant. Only 14% of variance could be accounted for indrug-related arrests other than marijuana. The factor related to other arrestsincluded a lower proportion of persons with skilled vocations. Finally, almost47% of drunk-driving arrests was explained. Significant predictors included ahigher proportion of the population living in mobile homes, a lower propor-tion of persons with vocational skills certification, a higher proportion ofpersons born overseas, and a lower proportion of persons married. Asbefore, the factors associated with drug-related offenses are different thanthose associated with assaults, breaking and entering, and vandalism.

A multivariate analysis of variance was conducted to compare thevarious types of drug-related offenses across the six clusters of rural commu-nities. A significant difference was found among the clusters (WilksLambda¼ 0.6072, approx F(30,446)¼ 1.97, p<0.01). Posthoc univariateF-tests revealed significant cluster differences for drug possession(F(5,116)¼ 2.27, p<0.05), and marijuana offenses (F(5,116)¼ 2.76,p<0.05). However, again, these findings indicate that dealing offenses,offenses involving drugs other than marijuana, and drunk driving, vary lessacross types of rural communities in New South Wales than the assault,breaking and entering, and malicious damage.

Figure 3 shows the five types of drug-related arrests across the sixcommunity types Possession, dealing, and marijuana offenses vary together,

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 656] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

T2

F3

757

758

759

760

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 657

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 657] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

Table

2.

SignificantPredictors

inStandard

MultipleRegressionofCensusVariablesonArrestsRatesforDrug-R

elatedOffenses

andDrunkDriving

StandardR2

t-statistic

Possessionofdrugs

Proportionofpopulationin

mobilehomes

0.289

2.522,p<

0.013

R2¼0.344

Proportionofpersonswithskilledvocations

�0.373

�2.652,p<

0.009

Adj.R2¼0.230

Proportionofpopulationborn

overseas

0.352

2.246,p<

0.027

R¼0.587,p<

0.0002

Dealingin

drugs

Proportionofpopulationin

mobilehomes

0.411

3.577,p<

0.0005

R2¼0.340

Adj.R2¼0.225

R¼0.583,p<

0.0003

Marijunaoffenses

Proportionofpopulationin

mobilehomes

0.305

2.696,p<

0.008

R2¼0.361

Proportionofpersonswithskilledvocations

�0.391

�2.812,p<

0.006

Adj.R2¼0.249

Proportionofpopulationborn

overseas

0.389

2.726,p<

0.008

R¼0.601,p<

0.0001

Other

drug-relatedarrests

Proportionofpopulationgraduatedfrom

highschool

0.193

1.945,p<

0.05

R2¼0.268

Proportionofpersonswithskilledvocations

�0.347

�2.328,p<

0.022

Adj.R2¼0.140

Drunkdriving

Proportionofpopulationin

mobilehomes

0.569

5.974,p<

0.000

R2¼0.546

Proportionofpersonswithskilledvocations

�0.385

�3.282,p<

0.001

Adj.R2¼0.467

Proportionofpopulationborn

overseas

0.242

2.011,p<

0.047

R¼0.739,p<

0.0000

Proportionofpersonsmarried

�0.291

�1.946,p<

0.050

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

658 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

largely due to the over-representation of marijuana offenses in these data.‘‘Other drug arrests’’ follows its own pattern among the six communitytypes. Drunk driving partially follows the same pattern as arrests forassaults, breaking and entering, and malicious damage, and partially followsthe pattern for drug-related arrests, especially marijuana. In this regard, itwould appear that drunk driving is higher in communities with social dis-organization, such as the second (coastal communities) and fifth (smallinland communities) clusters. In addition, it is high in satellite communities(cluster 3), which shows a higher level of social organization (althoughabove-average residential instability), and below average in cluster 1 (largeurban centers), which shows a higher level of social disorganization, andmore commuting, which implies having a few drinks while driving homeafter work.

DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY

The results of the clustering procedure support the hypothesis that anabsence of social cohesion was associated with an increase in crimes, but

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 658] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

Figure 3. Standardized offense rates for drugs and drunk driving by community

cluster.

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 659

much less so for drug-related violations. The results clearly identified crucialsocial and economic factors of rural communities that were associated withdrug-related violations, as a unique variety of crime. The most importantgeneral finding was that drug use is related to social and economic structuresthat vary across identifiable types of rural geographic locations.

To speak of rural drug use is insufficient. Rural drug use is a complexphenomenon that merits complex analyses and explanations. These findingsindicate the enormous diversity of the relationship between social andgeographic factors and drug use in rural Australia. It dispels the notionthat small towns have less drug use than larger towns. The further findingthat even small stable towns and small inland towns have rates ofdrug-related violations similar to other areas indicates that small size oftown is important, because other economic and social factors are presentin those locations.

Peer groups form the essential link within community structure forbecoming a drug violator. The presence and characteristics of peer groupsthat accept drug-related violations varies enormously in different types ofcommunities, rural or urban. Furthermore, the relationship of police to thelocal community strongly effects how they enforce against drug-related vio-lations. For example, Jobes[58] found that many rural New South Walespolice officers virtually ignore marijuana use.

Until recently, addictive drug use was concentrated within an identifi-able drug subculture in particular urban locales. People in that subcultureinteracted primarily within that group, and independently of conventionalsociety. Within the group, drug use created a common bond around directand indirect experiences associated with procuring and using drugs.Although known to the police, the subculture remained relatively invisibleto most people outside the locales. Police action against individual users wasrelatively rare, except when enforcing against drug sales or violations tosupport their habits. The urban scene typically had easy access to drugsamong subculture members in socially-disorganized areas. Law enforcementwas impersonal and detached.

This paper demonstrates that drug use in rural areas in Australia isnow widespread, complementing the ubiquitous presence of alcohol. Unlikeother crimes, rural drug-related violations are more common among placesthat have higher than average incomes and residents who were born over-seas. They are associated with lower than average marriage rates and smallertowns. The most important finding of the research is that there is minimaldifferentiation in drug-related violations among different types of rural com-munities.

One explanation for similar drug-related violation rates across alltypes of rural communities may be that they indeed have similar patterns

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 659] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

660 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

of drug consumption. It also is feasible that local police in organized com-munities enforced local norms against addictive drugs when they were awareof them, whereas police in disorganized communities did not. This differ-ential enforcement would elevate rates in organized communities and under-state rates in disorganized one. Even if the frequencies of drug-relatedviolations were similar, it is likely that each type of community has itsown norms and patterns of drug-related use that emerge from specific pat-terns of organization. ‘‘Organized’’ farm communities enduring economicfailure and disillusionment suffer strains which can encourage drug use andproduction, especially marijuana. So too, do high unemployment, and stag-nant inland ‘‘disorganized’’ communities. Pockets of residents in the pros-pering, larger inland towns, and the somewhat anomic coastal and touristtowns, also have their motives for using drugs. If the long-observed patternthat rural crimes lag behind, yet resemble, urban patterns, then drug use inrural areas can be expected to be on a rapid upward trajectory.[59]

Additional research about the patterns of drug use in rural communitiesof Australia is certainly called for in order to shed more light on importantissues of epidemiology and etiology, but of even greater importance is theneed for research on the relationship between substance ‘‘abuse’’ and utiliza-tion of health service. Two studies show why health care provisions is so vitaland why more research is needed. One study of crime in four rural commu-nities by the authors[60] found the major concern of residents was lack ofmental health support. In one small community, there had been five youthsuicides. All five were receiving psychiatric treatment. Two were drug users.Although there was a psychiatric help line, it was not available after hours.Consequently, the emergency services in rural areas have to cope with anypsychiatric emergency that occurs and they do not have the expertiserequired. Country doctors also lack the time or the expertise to effectivelymanage psychiatric illness. In another study,Wood[29] found that mainstreamhealth services were particularly inadequate in rural areas for people withboth alcohol- and drug-related problems and mental disorders. There was alack of collaboration between drug- and alcohol-user treatment staff andmental health workers, GPs, hospital staff, and generalist health workers.Police inexperience and problems with isolation were also a concern.

REFERENCES

1. Donnermeyer, J.F. The Use of Alcohol, Marijuana, and Hard Drugs byRural Adolescents: A Review of Recent Research. In Drug Use in RuralAmerican Communities; Edwards, R.W., Ed.; Harrington Park Press:Binghampton, NY, 1992; 31–75.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 660] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

911

912

913

914

915

916

917

918

919

920

921

922

923

924

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 661

2. Edwards, R.W. Drug Use in Rural American Communities; HarringtonPark Press: Binghampton, NY, 1992.

3. Robertson, E.B.; Sloboda, Z.; Boyd, G.M.; Kozel, N.J. RuralSubstance Abuse: State of Knowledge and Issues; NIDA ResearchMonograph Series 168. U.S. Department of Health and HumanServices, National Institute on Drug Abuse: Rockville, MD, 1997.

4. Weisheit, R.A.; Falcone, D.N.; Wells, L.E. Crime and Policing in Ruraland Small Town America, 2nd Ed.; Waveland Press: Prospect Heights,IL, 1999.

5. Scheer, S.D.; Borden, L.M.; Donnermeyer, J.F. The RelationshipBetween Family Factors and Adolescent Substance Use in Rural,Suburban, and Urban Areas. J. Child Family Stud. 2000, 9, 105–115.

6. Edwards, R.W. Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug Use by Youth inRural Communities. In Perspectives on Violence and Substance Use inRural America; Blaser, J., Ed.; Midwest Center for Drug-Free Schoolsand Communities and the North Central Regional EducationalLaboratory: Oak Brook, Il, 1994; 65–94.

7. Donnermeyer, J.F.; Scheer, S.D. An Analysis of Substance Use AmongAdolescents From Smaller Places. J. Rural Health 2001, 17, 105–113.

8. Oetting, E.R.; Edwards, R.W.; Kelly, K.; Beauvais, F. Risk andProtective Factors for Drug Use Among Rural American Youth. InRural Substance Abuse: State of Knowledge and Issues; NIDA ResearchMonograph Series 168; Sloboda Z., Boyd G., Robertson, E., Beatty L.,Eds.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, NationalInstitute on Drug Abuse: Rockville, MD.; 1997; 90–130.

9. Donnermeyer, J.F. Crime and Violence in Rural Communities. InPerspectives on Violence and Substance Use in Rural America; Blaser,J., Ed.; Midwest Center for Drug-Free Schools and Communities andthe North Central Regional Educational Laboratory: Oak Brook, Il,1994; 27–63.

10. Australian Bureau Of Statistics (1996). Census of the Population;Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, 1990–1995.

11. Bell, G.; Pandey, C. The Persistence of Family Farm Ownershipin Advanced Capitalist Economies. In A Legacy Under Threat;Lees, J., Ed.; University of New England Press: Armidale, NSW,1997; 213–244.

12. Johnston, L.D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G. National SurveyResults on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study,1975–1997; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,National Institute on Drug Abuse: Rockville, MD, 1998.

13. Oetting, E.R.; Beauvais, F.; Edwards, R.W. The American Drug andAlcohol Survey; RMBSI, Inc.: Fort Collins, CO, 1984.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 661] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

925

926

927

928

929

930

931

932

933

934

935

936

937

938

939

940

941

942

943

944

945

946

947

948

949

950

951

952

953

954

955

956

957

958

959

960

961

962

963

964

965

966

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

662 DONNERMEYER, BARCLAY, AND JOBES

14. Forney, M.A.; Inciardi, J.A.; Lockwood. Exchanging Sex for Crack-Cocaine: A Comparison of Women from Rural and UrbanCommunities. J. Community Health 1992, 17, 73–85.

15. Weatherby, N.L.; McCoy, H.V.; Metsch, L.R.; Bletzer, K.V.; McCoy,C.B.; De La Rosa, M.R. Crack Cocaine Use in Rural MigrantPopulations: Living Arrangements and Social Support. SubstanceUse Misuse 1999, 34, 685–706.

16. Caulkins, J.P. Measurement and Analysis of Drug Problems andDrug Control Efforts. In Criminal Justice 2000: Measurement andAnalysis of Crime and Justice; Duffee, D., Ed.; U.S. Department ofJustice, Office of Justice Programs: Washington, DC, 2000; Vol. 4B,391–449.

17. Roberts, C.D. Data Quality of the Drug Abuse WarningNetwork. Am. J. of Drug Alcohol Abuse 1996, 22, 389–401.

18. Dekeserdy, W.S.; Schwartz, M.D. Contemporary Criminology;Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, 1996.

19. Thornberry, T.P.; Krohn, M.D. The Self-Report Method forMeasuring Delinquency and Crime. In Criminal Justice 2000:Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice; Duffee, D., Ed.;U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs: WashingtonDC, 2000; Vol. 4, 33–84.

20. Oetting, E.R.; Donnermeyer, J.F. Primary Socialization Theory: TheEtiology of Drug Use Deviance. I. Substance Use Misuse 1998, 33,995–1026.

21. Reiss, A.J.; Tonry, M. Communities and Crime; University of Chicago:Chicago, 1986.

22. Oetting, E.R.; Donnermeyer, J.F.; Deffenbacher, J.L. PrimarySocialization Theory. The Influence of the Community onDrug Use and Deviance. III. Substance Use Misuse 1998, 33,1629–1665.

23. Jobes, P.C. Migration and Social Problems in Small Towns: AnEmpirical Analysis of Awareness Among Rural Administrators. InResearch in Community Sociology; Chekki, D.A., Ed.; JAI Press:Amsterdam, 1998; Vol. 8, 210–221.

24. Griffiths, S.; Dunn, P.; Ramanathan, S. Drug and Alcohol Services inRural and Remote Australia; The Gilmore Institute, Charles SturtUniversity: Bathurst, 1998.

25. McAllister, I.; Moore, R.A.; Makkai, T. Drugs in Australian Society;Longman Cheshire Pty Limited: Sydney, New South Wales, Australia,1991.

26. Dempsey, K. Smalltown; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne,1990.

+ [17.4.2002–1:45pm] [637–666] [Page No. 662] i:/Mdi/Ja/37(5-7)/120004277_JA_037_5-7_R1.3d Substance Use & Misuse (JA)

967

968

969

970

971

972

973

974

975

976

977

978

979

980

981

982

983

984

985

986

987

988

989

990

991

992

993

994

995

996

997

998

999

1000

1001

1002

1003

1004

1005

1006

1007

1008

120004277_JA_037_5–7_R1.pdf

DRUG OFFENSES IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 663

27. Reilly, D.; Didcott, P.; Swift, W.; Hall, W. Long-Term Cannabis Use:Characteristics of Users in an Australian Rural Area. Addiction 1998,93, 837–846.

28. O’Connor, M.; Gray, D. Crime in a Rural Community; Federation:Sydney, 1989.

29. Wood, C. Falling Through the Net: Treatment In Country NSW.Connexions 1994, 13, 17–21.

30. Williams, P. Illicit Drug Use In Regional Australia, 1988–1998. Trendsand Issues, No. 192, Australian Institute of Criminology: Canberra;2001.

31. Rural Workforce Agency. Between a Rock and a Hard Place; RuralWorkforce Agency: Chalton, Victoria, 1998.

32. Darke, M.P. Heroin-Related Deaths in Regional New South Wales,1992–96. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000, 19, 35–40.

33. Aitken, C.; Brough, R.; Crofts, N. Injecting Drug Use and Blood-Borne Viruses: A Comparison of Rural and Urban Victoria. DrugAlcohol Rev. 1999, 18, 47–52.

34. Dunne, M.P. Substance Use by Indigenous and Non-IndigenousPrimary School Students. Aust. NZ J. Public Health 2000, 24, 546–549.

35. Mammott, P.; Stacy, R.; Chambers, C.; Keys, C. Violence in IndigenousCommunities; Report to the Crime Prevention Branch of the Attorney-General’s Department; Australian Capitol Territories: Canberra, 2001.