Cover – Tennant Creek Brio 'Artist Studio' (2020)

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Cover – Tennant Creek Brio 'Artist Studio' (2020)

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ 3

Cover – Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ (2020)

Statement

‘We are the creatives and the culture men, we can travel in our dreams – Winkarra. We’ve got to go back to country for those dreams. Our country has spirits – its alive – and it needs us: ‘our spirits and country are crying for us,’ because we are not practising on our grounds. We need strong resolve.

Our ArtIt’s a new cultural art for us mob where we can express our stories – it’s not inside our culture – it’s on the edge, coming in. Some of our dreams have different kinds of effects that come in the night, in our head, and we create something stranger. They’ve got meaning and it’s part of healing. The healing is also found in our ceremonies and our expression, it keeps people together and strong – if we lost that it would harm us and it would harm our future – if we lose it now what will we have for our future generations, they’ll never know anything, they’ll miss out on what we know.— Kamarnta wilyanka pakamarra (we are holding it strong)

The Italian word brio means mettle, fire, or vivacity of style or performance. It expresses the energetic, experimental and transformative spirit of the Tennant Creek Brio, whose collective work is a dynamic interplay of influences including Aboriginal desert traditions, abstract expressionism, action painting, found or junk art, street art and art activism.

The Tennant Creek Brio is an artist collective based in the Barkly regional town of Tennant Creek, (population 3,200) which is located in Warumungu country in the Northern Territory. The collective began in 2016 as an Aboriginal men’s art therapy program through Anyinginyi Aboriginal Health Organisation to help men with issues of alcohol and substance misuse. Under the direction of artist Rupert Betheras and supported by fellow artist Fabian Brown, Joseph Williams and the more senior David Duggie, the collective quickly gained traction amongst local men. The collective soon grew its core membership to include Marcus Camphoo, Simon Wilson, Lindsay Nelson, Clifford Thompson, Matthew Ladd and Joseph Williams alongside several occasional members and fellow travellers. By 2018, the art therapy program had moved out of Anyinginyi and under Nyinkka Nyunyu, the Tennant Creek’s art and culture centre, where the collective was joined by artist Jimmy Frank.

To cite this contribution: Tennant Creek Brio. ‘Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ (2020).’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 4 (2021): cover, http://www.oarplatform.com/cover-tennant-creek-brio-artist-studio-2020.

Tennant Creek Brio

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ 4

Each artist had been exposed to various traditional forms of cultural expression, i.e. sand, rock and body painting, along with canvas, print, TV, film, social media and religious and protest imagery before joining the Brio. The seeds of Brown’s iconic figurative style, for instance, were planted when he was young, producing sketches on the walls of his childhood dwellings. As a teenager, Williams learnt to carve from his grandfather, while Wilson also developed an interest in painting during his teens. Additionally, Betheras’ early teenage years were marked by Melbourne 1980s graffiti subculture. The artists share a rebellious streak and commitment to unsettling the status quo born from a shared experience of outsider status.

Working collectively, the artists are also challenged to reinvigorate their individual practices through exposure to new materials and mediums, and through new approaches that are collaborative and dialogical. No individual’s authorship necessarily takes priority over the others. At times one artist might finish the work of another through reimagining the intentions and possibilities of their art in the act of both making and presenting their work. While the collective remains true to its art therapy origins, it has also developed a significant social and cultural voice reflecting on the rigours of life in a frontier town that remains marred by the ongoing impacts of colonisation and the unending struggle to maintain cultural identity.

Some of the collective’s ‘found’ materials – such as disused metal, plan drawings from a nearby abandoned mine site, and disused poker machines – potently feed into the force of this commentary and outsider status.

(Artist Statement by Tennant Creek Brio and Nyinkka Nyunyu Arts and Culture Centre)

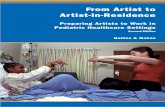

Cover Image: Installation view from Tennant Creek Brio artist studio, including works by:Lindsay Nelson, Clifford Thompson, Fabian Brown, Marcus Camphoo, Joseph Williams, Jimmy Frank, Simon Wilson and Rupert Betheras, left to right: Pot of Gold, 2 Woman 5 Dragons, Country/Swagman, Indian Dreaming, Titan, and One-eyed Man. Image courtsey of Nyinkka Nyunyu Arts and Culture Centre.

1 Jimmy Frank and Joseph Williams, in consultation with Michael Jones, Norman Frank and Fabian Brown, ‘Minngalangala Anyula Wilyangka Pakkamarra, From the Edge We’re Holding it Strong, Living on the Edge’, in NIRIN NGAAY, Jessyca Hutchens, Brook Andrew, Stuart Geddes and Trent Walter (eds.), published by the Biennale of Sydney Ltd, Sydney, 2020, available online: https://nirin-ngaay.net

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ 5

Studio view, works by various artists, central works by Fabian Brown and Rupert Betheras. Image courtesy of

Nyinkka Nyunyu Arts and Culture Centre.

Left to right: Lindsay Nelson, Marcus Camphoo (Double-O), Clifford Thompson, Fabian Brown and Rupert Betheras.

Image courtesy of Nyinkka Nyunyu Arts and Culture Centre.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ 6

The Tennant Creek Brio is an artist collective based in the Barkly regional town of Tennant Creek, (population 3,200) which is located in Warumungu country in the Northern Territory. Following their debut exhibition in 2016 at Nyinkka Nyunyu, in 2017 the Brio’s exhibition ‘Present Tense: Tennant Creek Men’s Centre Art’ was held at the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art in Darwin, garnering, albeit limited, acclaim. In 2019, the Brio exhibited ‘King of the Roosters’ at Raft Artspace, Alice Springs and also ‘Wanjjal Payinti’ (Past and Present) as part of the 2019 ‘Desert Mob’ group exhibition, Alice Springs. In 2020, The Tennant Creek Brio were participants in the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, titled NIRIN, contributing major installations of work at Cockatoo Island and Artspace.

Fabian Brown and Rupert Betheras, 2019, Ancestor Boards series: Blue-bird and Trump, She-Wolf, Enamel and mixed media on board. Image courtesy of Nyinkka

Nyunyu Arts and Culture Centre.

7CreditsOAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021

Issue Four, May. 2021 Working with you,

Editors Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, and Nina Wakeford

Contributors Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, Nina Wakeford, Francois Blom, Garth Erasmus and Esther Marié Pauw, Elisabeth Lebovici (translated by Naomi Vogt), Martina Schmuecker, E.C. Feiss, Katherine Guinness, Charlotte Kent, and Martina Tanga, Rib Davis, Marie Caffari and Johanne Mohs, Sarah Jessica Rinland, Johann Arens, and Mihai Florea

Design Julien Mercier

Issue Design 0ffsh0.re

Advisory Board Kathryn Eccles, Clare Hills-Nova, Laura Molloy, and David Zeitlyn

ISSN 2399-5092

Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, and Nina Wakeford

OAR is published once a year by OAR: The Oxford Artistic & Practice Based Research Platform.

E-mail [email protected] www.oarplatform.com

Author generated contentOAR Platform attempts to provide a range of views from the academic and research community, and only publishes material submitted in accordance with our submission policy.

The views expressed are the personal opinions of the authors named. They may not represent the views of OAR Platform or any other organisation unless specifically stated. We accept no liability in respect of any material submitted by users and published by us. We are not responsible for its content and accuracy.

RepublishingAll contributions published by OAR Platform are done so under a Creative Commons – Attribution/ Non Commercial/No Derivatives – License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). This means that material published on OAR Platform is free to re-publish provided the following criteria are met:

1. The work is not altered, transformed, or built upon, and is published in full. 2. The work is attributed to the author and OAR Platform.3. The work is not used for any commercial purposes.

Further information can be accessed here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/.

SubmissionsAbstracts for submissions (approx. 300 words) should be sent to [email protected] may propose either a response to this issue or a contribution for future issues.A more detailed call for responses and submissions can be found on the final page of this issue, and at http://www.oarplatform.com/contribute/.

Introduction 8OAR Issue 1 / APR 2017

Cover – Tennant Creek Brio ‘Artist Studio’ (2020)

10 Introduction – Working and not working with you, Working with you, and you, and you Dear Jess, Naomi and Anita Working with you, Alone Together With Them,

19 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms?

31 TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER

59 Re:Site (after R.M.), 2018

61 The Art of Resource Development: Here to Support in the Institution of Art.

74 Collaborative Reflections on The Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative

80 Talking about Oral History

81 In the Name of Art: Literary Mentoring as a Collaborative Process

Tennant Creek Brio

The EditorsJessyca Hutchens Nina WakefordAnita PazNaomi Vogt

Francois Blom, Garth Erasmus and Esther Marie Pauw

Elisabeth Lebovici Translated by Naomi Vogt

Martina Schmuecker

E.C. Feiss

Katherine Guinness, Charlotte Kent, and Martina Tanga

Rib Davis

Marie Caffari and Johanne Mohs

Contents

Contents Page 8OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021

Introduction 9OAR Issue 1 / APR 2017

90 Hand in Glove

111 Immobilisation

113 Collaborating with a stick — Algernon Schtick Meets Nina Bambina

Jessica Sarah Rinland

Johann Arens

Mihai Florea

Contents

Contents Page 9OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 10

Working and not working with you,Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, and Nina Wakeford

To cite this contribution:Hutchens, Jessyca, Anita Paz, Naomi Vogt, and Nina Wakeford. ‘Working and not working with you,.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 4 (2021): 10–18, http://www.oarplatform.com/working-working/.

In this, our fourth and final issue, Working with you, we decided that instead of our usual co-authored editorial introduction, we would each contribute our own separately authored introduction on the theme, both as an ostensible nod to collaborative research relationships and as a final subversion of our own prior adherence to editorial norms. As it has worked out, an extensive series of delays and disruptions have effected this issue in particular, leaving us feeling particularly sheepish about making introductions on behalf of ourselves and others, while making claims about the nature of working relationships that are set in motion by OAR as a project. And yet, we also couldn’t resist presenting some collective thoughts on the contributions to this issue, precisely because our performative separation as editors (our individual pieces will directly follow this one) proved to re-engage us with the stakes of this issue and the complex ways contributors have articulated relations as something greatly moved on from reductive notions of individual versus collective authorship.

Currently, in art making and practice based research, working under the rubric of the collaborative, the collective, or the participatory is frequently rhetorically celebrated but in our view, often not materially or conceptually supported in-line with the specificities demanded by new working relationships, with participation, networking, and interdisciplinary dialogue often offered as their own reward. Debates more specific to contemporary art that have centred on the aesthetic, affective, ethical, and political stakes of community engagement and artistic representations of social projects are moreover not necessarily widely applicable to the wide spectrum of collaborative acts elicited through artistic and practice based research. But rather than setting their arguments against the failure of the potential of the collaborative, this issue seems to rest on the way very particular research contexts engender certain modes of relating, and their associated processes, rituals, materials, and outcomes. They suggest our working relationships always need attentiveness, wherever they may sit within any particular scale of autonomy and heteronomy.

Several contributions to this issue reflect a growing interest on the collaborative nature of research processes that are less examined on these terms, or might usually be considered to undergird forms of creative autonomy, drawing out the subtle social and artistic exchanges that are usually in the background of more individuated projects or projections. This includes a piece by oral historian Rib Davis, presented in the form of a recorded conversation between himself and three other historians, on how interviewees shape their own narratives through the dialogic process. Marie Caffari and Johanne Mohs investigate the underexamined collaborative exchanges that take place between creative writing students and mentors/supervisors. Mihai Florea, meanwhile, progresses an examination of the anxieties of preferring

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 11

lone research within a Theatre Studies department and the potentialities of performative thought processes, through a ludic collaboration with a stick. Indeed, collaborations with and between non-human actors are a major theme within this issue. Jessica Sarah Rinland’s essay expounds upon the artistic research processes that led to the creation of a ceramic replica of an elephant tusk, as a means to reflect on and replicate museum conservation practices. Johann Arens’s video work explores the intimate tactile relationship between objects being packed and sent and the customised cradles (created from foam moulds) that ensure their care and safety.

Pieces that turn more towards collaborative contemporary art production each refute reductive framings of identity-positions, such as between artist and participant, collaborator, community, or audience. The cover for this issue, by the artistic collective the Tennant Creek Brio, reflects their shifting set of artistic positions and collective formations across artworks and mediums, their practice forming a diverse mediation of issues inherent to the contexts where the artists live, work, practice culture, and resist on-going colonialism. A text by Elisabeth Lebovici, translated from French to English by Naomi Vogt, considers the role of collaborative exhibition cultures acting within the social transformations of the Lower East Side in New York during the midst of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and early 1990s. Martina Schmuecker’s filmed performance collaborates with other artists across time, re-enacting and re-working pieces by Robert Morris and Carolee Schneemann. In a study of self-organised groups in the Netherlands, E.C. Feiss unpacks the complex mechanisms of collaboration between undocumented people and the contemporary art world.

Other works more directly grapple with artistic collaborations as participants, reflecting back on their involvements. Katherine Guinness, Charlotte Kent, and Martina Tanga reflect on a specific collaborative endeavor, a workshop titled FAAC YOUR SYLLABUS, that they ran as participants of the research group The Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative (FAAC), pushing past the often utopian ideals of collaboration to also explore its challenges and performative aspects. Three musicians, Francois Blom, Garth Erasmus, and Esther Marié Pauw listen back and reflect on recordings of the music theatre production Khoi’npsalms, exploring its multiple meanings as a work of decolonial art, and its creation of both tensions and intimacies through collective sound-making.

Finally, in the four pieces that begin this issue, four OAR editors (Jessyca Hutchens, Nina Wakeford, Anita Paz, and Naomi Vogt) consider what it has meant to work together on this collective project, which has entailed various forms of coming together (often across four time-zones, and sometimes in shared physical space), as well as a various forms of working with contributors and institutions. We left the title of this issue as an unfinished sentence, ‘Working with you,’ because there is rarely only a singular you, but a great many you’s that form our creative working relationships. Rather than a simple valorisation or critique of the collaborative, this issue hopes to be attentive to the relations of our working lives, and the multitude of ways they produce creative work.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 12

WORKING WITH YOU, AND YOU, AND YOU Jessyca Hutchens

Ideas around artistic autonomy have made a comeback in recent years, largely within the context of discourse around creative labour as a model for the ideal neoliberal subject – one who is both highly individuated but also sociable, flexible, mobile, networked, and able to leverage vast horizontal social networks. On the one hand, ideas of artistic autonomy are now said to be imbedded within the professional values of neoliberalism, and its conditional promise of greater personal freedom and flexibility, while also often leading to precarious conditions and a blurring of work and social life. At the same time, theorists are still optimistic about the potential for artists to reclaim forms of autonomy away from neoliberal professional values and labour conditions.1

Fidelity to self, to one’s own ideas, to deeper relationships that exist in excess of or outside of productive relations, as well as to certain forms of rootedness, slowness, and retreat from hyper-productive environments are now often being positioned as oppositional to dominant modes of production. Papers extol the radical political potential of everything from friendship to remote artist retreats. But there is also much critique around how such forms and practices have also been long incorporated into the stop-start patterns of neoliberal work, even part of a broad imperative to self-manage: to find time, to take time-out, to retreat, to set boundaries, to re-centre, to be mindful, to find that ever elusive work-life balance.

OAR is highly exemplary of the on-going negotiations that collaborative work now so often demands. As editors we schedule and re-schedule meetings across three or four time-zones, divide and re-divide up tasks in response to our own shifting workloads and the time pressures of those we work with, we regularly type out the familiar scripts of apology and appeals for more time, another time, a better time. We make space for our friendship, and also sink into long delays and silences. We place and face pressure, retreat, and re-emerge. Instead of a regular shared time and place to work, we have only our shared commitment to a collective project to keep us going, which is itself an amorphous, highly flexible entity.

The idea of the ‘project’ has been much theorised as a particular mode of production within contemporary art, generally understood as an on-going processual way of working that tends to exacerbate the blurring of professional and personal domains. Bojana Kunst describes art projects as ‘processual, contingent and open practice’, a mode of working she argues unduly focuses on possibilities in the future at the expense of connections to social life in the present, leading to a kind of unending speculative mode of working/living.2 This way of thinking about projects has particular relevance to the paradigms of practice-based and artistic research, that place high value on open processual modes and forms of research documentation. OAR is explicitly a platform that accretes outputs from open-ended research-based projects, and itself eschews the traditional temporal modes of most journals. On the one hand, it seemed valuable to actually help give ground to some of this on-going, iterative work, which often exists through even more ephemeral formats, yet are we also contributing to work cultures that become all-consuming due to their endless deferrals?

Boris Groys has written of the loneliness of the project, due to the way projects immerse subjects in a heterogeneous time that is desynchronised from the time experienced by society.3 Groys acknowledges that while projects are often a collective effort, loneliness

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 13

persists in the form of ‘shared isolation.’4 The demand (and also pleasure) of large collective projects like exhibitions, or films, or journals, is to retreat from the time pressures of ‘regular’ social life, into a more immersive and separate time-space. This notion of the project shares with traditional conceptions of artistic autonomy the idea of a separate space of creation away from the mundanity, routine, and utility of daily life and labour. Project-time is antisocial in one sense, yet also promises an intense and exciting form of sociality through a shared endeavour.

If only we could be alone together more often…

Yet, with OAR, like many other kinds of on-going projects, we only rarely step into project-time together. Most notably, we undertook a residency together at the remotely located Bibliothek Andreas Züst, spending our days balancing frantic working with long alpine walks, the ultimate form of enacting collective isolation to immerse in our project. More often though, OAR takes a backseat to the demands of other projects we’re each involved in as researchers, only asserting the heterogenous time of the project intermittently through global video calls, periods of intensive work, and our on-going sense of commitment to something that no longer has an institutional home or on-going funding. In many ways the loneliness of a single project begins to sound ideal in comparison to the variegated time of multiple, overlapping, open-ended projects.

Although strongly associated with contemporary forms of precarious labour, project-work perhaps also offers pleasures that have been eroded elsewhere, creating intimate forms of collective engagement amidst widespread social isolation and work based around competition and self-management. I often wonder in regard to OAR if we would we have stayed in such close contact as friends without the promise, excuse, demand, and energy of a collective project. Recently I made a film with my 92-year-old grandmother, a project that entailed us completely up-ending the usual routines and spaces of the house we currently share with other family, in ways that felt exciting and bonding. Is it that domestic and social life is now more subject to project-logics (do we need ‘projects’ to justify time at home?), or maybe it is more that work has long managed to co-opt something of the collective spirit of family and community life, the heterogenous time of communal ritual or the kind of community or civic projects that once committed to distant futures. Maybe we need more communal projects that strengthen our social bonds outside of our working lives. While OAR is definitely a form of work within our respective fields, unaffiliated to any of our current places of employment, it allows for certain kinds of freedom and interruptions to our work for institutions.

Maybe it is always pertinent to ask: what is a particular project interrupting to instantiate its own collective autonomy away from things? While project-work is a dominant form of labour, we should be attentive to the specific textures, demands, energies, and pleasures that different projects create. Pascal Gielen has argued that ‘autonomy can only be through heteronomy’, and also that ‘artistic autonomy does not coincide with individual discretion and exemption from collective obligations.’5 Perhaps this means finding forms of mutual support and collective passion that are generous and attentive to our lives and obligations as individuals. Autonomy, not as lone researchers within precarious institutions, but through collective arrangements that are consciously protective.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 14

OAR has teetered on drifting away at times, becoming increasingly unmoored as we have moved to live and work in different places. Keeping it going is more than just the time-puzzle of administering collective work, it’s marshalling a kind of shifting collective energy that feels special and particular to this project and to us. I wonder now if that’s sort of what we were thinking about when we titled this issue ‘Working with you,’ an unfinished sentence that addresses a particular subject, a you, instead of focusing on particular collective forms: collaboration, participation, social engagement or so on, terms which all have their own way of reducing the nature of social/working relations down to a kind of desired product or outcome. Through OAR, I am working with you, and you, and you…

DEAR JESS, NAOMI AND ANITANina Wakeford

Hi there. It has been such a joy working with you, three. We have lived through many of each other’s rites of passages – educational, paid employment, domestic. I was remembering recently the afternoon we pitched our proposal to the (was it IT?) grants committee at Oxford. I recall that we were up against ‘ap developers’ and it seemed improbable that a small, fine art-led humanities project led by four DPhil students could be convincing in terms of what appeared to be criteria tipped more towards entrepreneurship or digital ‘quick wins’. What prompted me to also work with Hannah for our first issue – revisiting Adrian’s words on capture of art by academia. The University funding scheme was geared to an outcome much smaller and more discrete than this has ended up being. This morning, when we all discussed the introduction, I showed you these photos of us in the Alps. It was when we were trying to sort out the article order for one of the issues, and we cooked together the large kitchen so generously at our disposal. (You didn’t expect me to avoid sentimentality, did you?). And then the group shot – I think another resident took this? This morning three of us agreed that we’d share them here (So I hope Anita is ok with that). I’ve followed them with a diagram I found in an article on ‘team effectiveness’ and I’d love to know what you thought an OAR version of this diagram would look like!

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 15

Figure 1: from Kozlowski, Steve W.J., and Daniel R. Ilgen. “Enhancing the Effectiveness of Work Groups and Teams.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 7, no. 3 (December 2006): 77–124.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 16

WORKING WITH YOU, Anita Paz

Working with you was a negotiation. Give and take. You give some thoughts; not all – some you may want to keep for later, for and to yourself. You take some thoughts; not many – after all, take too much and it’s no longer with you. At times a conquest, at others, a surrender. Working with you is working in the space between not giving too much and not taking too much. It is there that a compromise must be found. A middle line of no-one.

Working with you was a translation. An attempt to think, to talk, to write in at least four different languages, and to do so at once. Negotiating my owns for yours, and all of yours for all of mine. And at the end of that, all these different forms of expression, all these languages which are ours, condensed into a single one. Which is of no one. All the thoughts that we gave pushed into a single utterance. No longer a plurality, but a hybrid. It is ours, but it is not yours, nor is it mine.

ALONE TOGETHER WITH THEMNaomi Vogt

From the very start, establishing OAR required mapping out all the issues we would publish, with timelines and themes. This was the lot of a hopeful project that needed a handful of hard facts to demonstrate feasibility, including when it came to convincing ourselves. Thus an editorial arc was traced with Jessyca Hutchens, Anita Paz, and Nina Wakeford: the colleagues with whom I would end up editing this journal. Working with them, in a sense, meant imagining our collaboration until its end. And building that required methods not unlike those of make-believe.

We would write and put together a prologue, which we would call issue zero. Because one of the platform’s aims was to foster forms of dialogue, citation, and response which we felt were lacking in the arts and humanities, we found a designer – Julien Mercier – who would not only make space for these features but would structure an entire platform according to them. When he finished building the site, he thought OAR would need its own typeface, so he half-secretly designed a full alphabet font and called it Oar. Everywhere around us, artistic research seemed to be proliferating without formally accreting. So we decided that any work responding to a previous output would become quotable as a response. And the timeframe to submit response proposals would be unbound. The published responses would present as horizontal reactions to a primary output. This way, pairs or clusters of publications would stand in relation to each other like shot-counter-shots in a film, rather than forcing the reactions to gather at the bottom, creating vertical hierarchies and the suggestion of increasing remoteness. On this platform, we wanted researchers and artists to be able to think, work, research, write, and produce together, whether at once or asynchronously.

Once we started working together as an editorial team, the day-to-day facts of this collaboration became as salient as the ideals at the heart of the journal. For me, the strongest realization remains – perhaps quite unspectacularly – the experience of sharing an inbox with three other people. It was unsettling at first, this decision to trust in three individuals to share my mail, to address someone I might admire, to handle prickly administration or to hold a

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 17

meeting with a contributor on my behalf if needed. None of this involved the assumption that they would think or act similarly to me – sometimes quite the opposite. This shared custody of communication and email became natural in a way that still feels meaningful now. I don’t think I would want to share an inbox with anyone else, including with people whom I might know even better and whose work I trust just as much.

Of course, working with my co-editors has entailed many other events, some of which are more conducive to narrative. We spent a week in residency at an Alpine library barely sleeping to get our first issue out while the weather turned from hot sun to piles of snow overnight. We presented our work at conferences, standing for the first time in front of an audience not alone (an audience that would occasionally remark on the fact that we were a team of four women – to which we tended to answer: ‘Yes’). We had long debates on the rare occasions where a submission would receive both the highest and lowest review rating, followed by the strange experience of trying to convey why something is very bad or very good to people who – by then I had started to assume – read, watch, listen, and judge in ways that are coextensive with mine. Yet somehow the form of collaboration I still find most remarkable continues to happen mundanely via the interfaces of electronic mail systems and word processing software. I can fathom the fact that I work with them most clearly when I am able to identify which one of us has edited (or, more nerdily still, copyedited) a piece we are publishing based solely on the nature of the suggested changes.

In this issue, the two submissions that I followed are a sound work by Rib Davis and an article by E.C. Feiss. Davis led a workshop on oral history interviewing which I attended at the British Library a couple years ago. Intrigued by the course’s approach to oral history as a form of research where ‘the product is the process’, I invited Davis to submit something to OAR. He developed a project akin to a short oral history of oral history practice. The work generously weaves together three conversations between Davis and other historians. Together, they explore the ethics of their work, the benefits of simply listening, and the peculiar ways in which subjects shape the narratives of their lives by expressing them orally. Feiss’s article carefully unpacks the complex mechanisms of collaboration between undocumented people and the contemporary art world. Her research here focuses on We Are Here (WAH), a self-organised group of undocumented people based in the Netherlands. The text considers another group’s practice, called Here To Support, which quietly orchestrated the insertion of WAH into the Dutch art system. Simultaneously emerging from Feiss’s article is an analysis of the ubiquitous incorporation of refugees into contemporary art.

My role in a third contribution to this issue was more involved. I translated to English the text by Elisabeth Lebovici ‘Exposer, montrer, démontrer, informer, offrir’, which was first published in 2017 in her book Ce que le sida m’a fait – Art et activisme à la fin du XXème siècle, but which partly originated in 1983 as a chapter of her doctoral thesis. In this text, the city of New York and particularly the Lower East Side is connected with the transformation of contemporary art exhibitions. In the 1980s and early 90s, HIV/AIDS provoked panic and silence. At that time, collaborative exhibitions – which Lebovici experienced and participated in directly – created time and space for the epidemic’s political visibility.

Translation work is how I funded most of my life as an undergraduate. I started by working for a search engine dedicated to design products, and was later hired by a film festival. Only very rarely did I translate texts written by an identifiable person. This time things were

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 Working and not working with you, 18

1 For example see Pascal Gielen, Mobile Autonomy: Exercises in Artists’ Self-Organization (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2015).2 Bojana Kunst, ‘The Project Horizon: On the Temporality of Making,’ Maska, Performing Arts Journal 27 (2012): 149–50.3 Boris Groys, Going Public, 1st edition (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2011), 70–84.4 Ibid.5 Op.cit., Paschal Gielen, p. 78–9.

different – I specifically wanted to translate something written by Lebovici. I had admired her work and read her art criticism when I lived in France. Her focus on queer histories and feminism was in many ways the diametrical opposite of the art history I was studying at the Sorbonne, as was the seminar ‘Something You Should Know’ which she has co-convened with the EHESS for fifteen years. I was excited to help translate a small piece of this world into English. And I enjoyed doing it partly while living in New York, walking through streets whose existence was differently vivid in Lebovici’s text. I liked imagining this text reaching a wider Anglophone or polyglot readership, since English of course also holds this dubious role of lingua franca.

Describing the collaborative work of translation is delicate. This is in part because my theoretical understanding of it is limited. I attended a translation study day once. In the French-to-English seminar I chose, we looked at Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le petit prince (The Little Prince), pausing on a famous passage in which the little prince asks the narrator: ‘S’il vous plaît… dessine-moi un mouton!’ (‘Please… draw me a sheep!’). We discussed the impossibility of conveying the French sentence’s cherished strangeness which results from the child’s mixed use of ‘vous’ – the polite form – and ‘tu’ via the imperative ‘dessine’ – the informal form – in a story that is all about making friends via taming animals and people. It came up that certain translations had later opted for the English sentence: ‘Please… draw me a lamb!’. Since the connotation of innocence stemming from the French bumbling conjugations was untranslatable, it was the animal in the sentence who, instead, had been rejuvenated and made tenderly inexperienced.

This philosophy of the lamb is what I turn to every time I am stuck in translation. Most of the time translation can indeed feel both lonely and too crowded – a constant tug between faithfulness to and emancipation from the original author, who often becomes an imaginary interlocutor. In this case, I was lucky to find a generous and responsive real interlocutor in Lebovici. I wondered if I had undertaken a translation as an act of scholarly fandom. But by the end what mattered was how this text taught me to work with even more people than before. There was the researcher and writer of 2017 who had written the chapter; the emerging art historian who had experienced the matter first-hand in the 1980s and had later lost to AIDS friends she made at the time; and the embodied author and reader of my translation in 2019-2020 (namely all three Elisabeths), as well as, from the start, my co-editors as readers, and myself as a translator, collaborating alone, together with them all.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 19

What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms?

Francois Blom, Garth Erasmus and Esther Marie Pauw 1

To cite this contribution: Blom, Francois, Garth Erasmus & Esther Marie Pauw. ‘What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms?’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 4 (2021): 19–30, http://www.oarplatform.com/what-do-we-learn-from-listening-back-to-a-decolonial-khoinpsalms/.

Khoi’npsalms is the title of a music theatre production that took place in March 2018, in Stellenbosch, South Africa, and that was presented by a flutist, an organist, and a Khoi memory music instrumentalist. The three musicians in Khoi’npsalms are also the three authors of this article compilation in which we reflect on aspects of our collaboration. Our music event was conceptualised over a period of ten months, but then improvised in live performance. The production did not make use of props other than our instruments, made use of occasional dramatic body gestures, and audiences were supplied with programme notes2 that indicated context and sources of the material that we improvised on. The source materials for our improvisation came from (what we call) ‘Khoi memory music’ (music, largely extinct, made by pre-colonial peoples of South Africa) and six Genevan Psalms (16th century psalm tunes and texts still in use in some Reformed church liturgies today).

What do we learn about our collaboration, as we each listen back to a selected clip from a recording made of our performances – performances that we conceptualised as a narrative that explored historical settings of colonial, postcolonial and decolonial tension? To explore this question, and taking impetus from scholars such as Walter Mignolo (2012, 2013, 2018) who explore decolonial art, this essay sketches our conceptualisation to the music event and presents four sound clips, chosen by ourselves and taken from one of our performances. We provide our individual reflections to these sound clips to explore a ‘listening back’. We conclude by commenting on aspects of our collaboration, and these include reflections on decolonial art that delves into aspects of harm to also find sensings of intimacy and trust. Photographs are included to support some of the arguments made.

CONCEPTUALISATION TO KHOI’NPSALMS

Khoi’npsalms translates as ‘Khoi and Psalms’, and is a new word that we coined. The word suggests an impossibility for South African colonial history: the merging, (in one space; in one music-making) of Khoi music and Genevan Psalms, never before sounded together in church spaces. In our live music event, South African Khoi music on bow, saxophone and ‘blik’nsnaar’ (an instrument built from an oil can and strings) was played by Garth Erasmus. His music laced into fragments of Genevan psalm melodies played by Esther Marié Pauw (flute) and Francois Blom (organ).

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 20

Historically, Genevan Psalm melodies and psalm texts, translated into Dutch, were brought to South Africa by the ‘Hollanders’ of the Dutch East India Company in 1652. In 1937, Totius – an Afrikaner cultural activist – translated the texts into Afrikaans (and the texts and melodies are still in use today). In our music event there appeared no sustained, worded dialogue, but extracts of the Afrikaans psalm texts were printed in the programme notes. Sonically, the psalm fragments were woven into remnants of Khoi memory music to engage with shared, violent histories, including imperial genocide and violence from apartheid social engineering of people, legislated in 1948 – harms that, in aftermath, continue to persist.

‘THERE’S SOMETHING IN THE CHARGE OF THE AIR’

Our 45-minute travelling production was performed on four occasions on an art festival (the ‘Woordfees’) in Stellenbosch. Each of the four church venues where we played have, over the years, carried particular histories of complex and complicit entwinement of racial history, with colonial and apartheid readings of religion, enmeshed with political power. One of the venues’ complete audio recording is available online.3

The photographs were taken at a rehearsal in the ‘Moederkerk’ (‘Mother church’, one of the Dutch Reformed Church congregations in Stellenbosch) and these show the grandeur of the building. The built structure has prominent white-washed pillars, a cathedral-high ceiling, stained glass windows, three separate galleries, an imposing ‘preekstoel’ (sermon lectern: a two-story high wooden structure with a roof and chamber that is reached by climbing ten stairs), and, at the back, a pipe organ that is considered by some to be the best church organ in Stellenbosch.

Hildegard Conradie, South to North view, Moederkerk, 2018.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 21

At a rehearsal, a filmmaker, Aryan Kaganof, was present, and he filmed a few sentences spoken by Garth.4 Garth talks about each space being different, and the differences stemming from ‘something in the charge of the air of each church’.

Afterwards, Garth reflects on his words: ‘There is something special about the space where the air we breathe is the air of the Moederkerk.’ He notes that this church has

…a particular charged air that reverberates with the history of sermonic orations amidst a history of specific calender dates from our shared colonial and apartheid timeline. This Dutch Reformed Church represents the chapter and verse of ‘apartheid divine’, as the justifications for apartheid legislation were based on theological arguments emanating from Reformed interpretations and teachings.

Garth also notes that his comment delves for critical self-awareness, asking questions such as: ‘How will our collaboration be received? Will we be seen to be desecrating the sacred canon of Genevan Psalms? Will our audiences join us as we improvise and perhaps decolonise? The air is fraught…’

When Garth speaks of ‘the charge of the air’ in Moederkerk, he alludes to various aspects about the venue that influence ‘mood, acoustics and timbres of the instruments’. Garth’s comment also alludes to aspects that relate to the socio-political contextual history of the church, as well as the building’s architecture: The building stems from the first colonial church congregation in Stellenbosch, from a church denomination that descends from the Dutch church traditions brought to the Cape in the 1600s, traditions that are still alive. In

Hildegard Conradie, West to East view, Moederkerk, 2018.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 22

the aftermath of South Africa’s material-racial privileges of colonialism and apartheid, the Moederkerk congregation is the most well-to-do, and most racially ‘white’, congregation of the four church venues where we performed.

The subsequent film that was made by Aryan Kaganof concludes the section screening Garth’s words by inserting a poetic text written by Garth prior to our music event:

ek onthou my kinderstem skreemaar wie gaan my lippeverniel met ‘n soen?

This text translates as, ‘I remember my child voice scream, but who will harm my lips with a kiss?’ This text, inserted into the film by the filmmaker, alludes to the bodily, spiritual and psychic injury that emanates from the present-day aftermath of colonialism and apartheid.

LISTENING BACK: WHAT DO WE HEAR?

The sound clips presented here appear in the chronological order that they were improvised on during our music-making. The first and second clips are from the live performance on 8 March 2018, whereas the final clip was recorded during an open rehearsal in the same venue, a week earlier, when passersby were welcome to attend.

LISTENING BACK: DECEIT: ESTHER MARIE’S REFLECTIONS5

Listen to audio clip of Khoi’npsalms 1, available here: http://www.oarplatform.com/what-do-we-learn-from-listening-back-to-a-decolonial-khoinpsalms/

It is in the liturgical space at the front of the Moederkerk, underneath the imposing ‘preekstoel’, that the Khoi music bow begins to play, quietly at first, as if tuning the instrument. People in the audience, who have arrived for the fourth 7am performance of Khoi’npsalms, keep on talking, coughing, but then begin to fall silent. A Khoi music bow, reminding of the hunting bow, has not been heard in this church before. The bow is disconcerting for its simple, direct appeal; its quiet invasion of a space usually filled with organ playing, hymn singing, sermons and prayers. The ongoing bow music serves to increasingly establish the Khoi presence in this space. This presence affirms the notion that bow music ‘belongs here’, in the South, and perhaps that bow music ‘knows how to live here’. The bow music player appears intent on exploring the act and skill of music-making, taking pleasure in the various melodic and percussive sounds that emit in a slow working-through of the playing and listening body, the space, and the listeners in the church pews.

Without announcement, I enter from the back of the church, with many steps to take in order to cover the distance between myself and the bow player at the front. My flute plays sounds of air, mimicking the winds that have blown the Dutch sailors from the north. I move down the aisle deliberately, to the front, playing air (sails billowing in the wind), and then play tones that erupt into overtones: the tones wisp

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 23

and disappear. I arrive, still playing, at the front of the church, meet the bow player, and emit a single, ‘exhausted’ note that resonates into the ample space. The note is pitched on F. (The note asks for water. The Khoi can show the sailor where the water is. This is a psalm that sings of a deer that ‘pants’ for water.)

I then play the first three notes of the psalm melody: pitched F—GA, with the first note twice as long in duration as the other two. The flute’s notes are gentle, pleading, tired, on the verge of physical disintegration and need. (The Khoi bow player knows how to help: recognises a fellow human in need, offers water.) But already in the taking, there lies deceit. In Khoi’npsalms, Psalm 42 is the disguise for an imperialist who has come to take, expand, convert, use, impose and report back to Amsterdam that the ‘refreshment station’ at the southern tip of Africa is now well-regimented and in good order.

After those three flute notes, there is a moment of hesitation and listening, after which the organ responds by playing the same three notes. ‘F—GA, Soos ’n hert…’ (As the deer). I listen, lingering, and then play a B natural pitch: a pitch that is not included in the scale or the melody of this psalm (to announce secretively to the colonizer: here will be betrayal in the receiving: We will take their water, land, culture, their souls, and convince them by force that our god is now their god.) The organ takes up the deceit and plays the fully harmonised psalm melody, pretending to ask for water and blessing amidst hardship. The bow continues to play, but now with scratches and a persistent rhythm, as if already signifying some trepidation of not adequately sensing the subtle nuances of power between colonizer flute and colonizer organ.

The scene is set for centuries of slow genocide, penned to a date of 16 April 1652 (called Settler’s Day in the former ‘national’ South African calender) when the Dutch (and before them the Portuguese and the Arabs, and after them the British) began harvesting southern Africa’s labour and natural resources. The genocide slips easily into South African apartheid of the 20th century where white-ness is perceived as superior to all shades of black-ness. The racial knowledge spills into a religious knowledge, and an assumed identity of racial superiority that enmeshes with a Christian way of doing, especially where religious and political power are intertwined uncritically. The treachery that lies in the acceptance of the water, after those first three notes, becomes a festering boil that infiltrates the habits, beliefs and humanity of people who live in South of Africa.

I learn the power of a single note: its symbolic strength of being out-of-place, in the same way that a Khoi music bow in a Reformed church is ‘out of place’, disconcerting, and therefore powerful. The flute’s potent B natural note, later taken up by the organ, becomes not only a symbol of (what I call) deceit, but is also an intentional offering of collaboration that states-asks: ‘Take this or not? Play with it?’

I learn that music-making in collaboration thrives on my intent to occasionally remain quiet, to listen, before responding in sound. I learn that our collaboration is a fragile discussion ‘laying bare’ thoughts in sound. That we have to trust that what we say will add to the conversation, and will be responded to.

I also learn, listening back, of a moment when I had in actuality ‘pre-decided’ the course of our improvised collaboration, and hear, in the flute’s insistent sound, when I had disagreed

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 24

with organ (‘on stage’): When I had thought Psalm 42 had almost been brought to its closure, I afterwards ‘hear’ dismay in my own playing when the organist then breaks into prominent melismatic, variation-like treatment of the hymn, to me overstepping a moment that ought to have belonged to a quiet closing and seeming-neutral statement of sonic material.

I learn that there are few securities (of prior rehearsal tropes repeated or written-out score) that steer our playing, even though I know ‘in which key’ the Genevan psalm is written (F major), and even though I can hear ‘in which pitches’ the organ and I talk to one another.

I learn, now, that these aspects (listening, conversing, fragility, laying bare, moments of apparent dispute, the symbolic nature of our music-making) are not things we musicians could have planned before the time: they happened in safe-unsafe collaboration, during live performance. These aspects perhaps hinged on three things in particular: First, our individual and collective acute sensings of the material we were working with: Genevan psalms and Khoi memory music placed in a contextual symbolic history; and, second, our willingness to explore as musicians and engage a mode of collaborating-in-waiting through sound. Third, these aspects could occur because we never knew whether what we were doing would be good enough, would work, would be convincing. As Garth put it: ‘The air is fraught…’

POWER-FUL

A sonic representation of colonial power enmeshed with religious sanction that celebrates the subjugation of ‘heathen’ people, amidst unwavering praise for an imperial god, is relayed in the audio clip that follows. While the flutist’s outstretched arm gestures a military suppression of the Khoi musician’s bow, the organ plays Psalm 47 with triumph, using tropes such as chromatic harmonic passages, cadences with delayed endings, and a slow tempo.6 The Khoi bow rasps and scratches in pitch-less throes.

Listen to audio clip of Khoi’npsalms 2, available here: http://www.oarplatform.com/what-do-we-learn-from-listening-back-to-a-decolonial-khoinpsalms/

After Psalm 47, the flutist exits the ‘preekstoel’ space, and the Khoi musician is left alone, playing a rainfall of teetering sounds, and then speaking into the calabash as he crouches to the floor. The clip that follows depicts this scene.

LISTENING BACK: MY HART, MY TONG: FRANCOIS’S REFLECTIONS7

Listen to audio clip of Khoi’npsalms 3, available here: http://www.oarplatform.com/what-do-we-learn-from-listening-back-to-a-decolonial-khoinpsalms/

In the clip from Psalm 45, I hear laments of longing and mourning, audible through the spoken – but structurally broken – words that are recited. Garth recites fragments from the words by a still-living Khoi chief, Chief Margaret: ‘Ons is krom en skewe instrumente’ (We are bent and mangled instruments). He also recites from the Afrikaans psalm’s text ‘My hart, my tong’ (My heart, my tongue) as well as the motto on the South African national coat of arms, ‘’!ke e:/xarra//ke’ (which translates as

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 25

‘Diverse people unite’ in a KhoiSan dialect). By using a playback recording and loop pedal, the voice, with flute interjections on single, drooping notes, interact with the organ, and combine into an aurality of intensity and brokenness. Painful subjugation is signified by the flute’s downward-falling notes, in counterpoint with the organ’s hymn and its melismatic tropes of church organ-like improvised passages, while the spoken voice carries the counterpoint as a firming bass. The voice’s broken utterances, the flute calls, and the persistent, variated hymn, all weave as a tapestried outpouring of lament and pain. Towards the end, the organ falls silent, leaving spoken words to resonate forth. ‘My hart, my tong…’

When I listen to my chosen excerpt I remember how I sat playing the organ, attempting to sound a sense of pain: Pain from our individual and collective pasts, both in the story we were referencing, as well as other stories of subjugation, violence, and abuse.

I also hear moments of dissonance in our playing, moving from dissonance to resolution, and sometimes in reverse order. The previous three psalms (42, 8 and 47) had ended on markedly strong claims to consonance (suggesting successful colonial power). However, Psalm 45 became the voice of the subjugated Khoi, speaking form the heart, in broken narratives, and after a while the flute returned (as if to ask, ‘Where is the pain? What is going on?’). The organ then responded by playing the same hymn, celebrating ‘a just king’ (and justice) that may have existed for the Khoi. However, the organ’s insistent trope-like chromatic and melismatic passages perhaps portrayed the irony: ‘a just king’, was not enacted by the colonial powers. The dissonances in sound, I suggest, relay some of these tensions.

When I listen to this clip, I learn that our collaboration was a sonic weaving of strands. Throughout Khoi’npsalms, I sense that we played amidst various aspects of being-different, re-imagining through sound how to perhaps pull together the unravelled strings of our past into a sonic understanding of the present South African political and human tapestry. Khoi’npsalms was the result of a collaboration by three individual musicians, each identifying

Aryan Kaganof, My hart, my tong…, 2018.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 26

with their own pain, but also strengths, spiritual awareness, musical input, cultural roots, placements and identity within present-day society. Our music exploration possibly gave a re-interpretation of the South African motto by symbolically uniting us (and perhaps our audiences included) into a multi-stranded improvisational music essay that relays South African history through sonic collaboration of improvisation, innovation and imagination.

LISTENING BACK: A WALL PUSHED OVER: GARTH’S REFLECTIONS8

The clip that I’ve selected is taken from the rehearsal at Moederkerk, a few days prior to the series of concert events. Before Khoi’npsalms, I was ignorant of the socio-historical significance of this church, but as we rehearsed there, and I experienced the space, I wanted to comment, in sound, on our collaboration as a form of ‘heightened awareness’ in response to that space.

We had arrived on a day when there was noisy activity in the church: tourists casually passing through, as well as a maintenance team at work. In the recording, these sounds are distinctly audible while we are rehearsing – up until the point at which I have chosen my clip. In the clip, the extraneous sounds fall completely silent.

In the moments before this clip begins, Esther Marié had been playing a brief, delicate flute solo with high-pitched notes that I had not heard her play before. Instinctively, I wanted to emulate these sounds on the saxophone to begin a conversation.

Listen to audio clip of Khoi’npsalms 4, available here: http://www.oarplatform.com/what-do-we-learn-from-listening-back-to-a-decolonial-khoinpsalms/

The sounds are a free interplay between the flute and saxophone, with both exploring their highest pitch ranges. There are moments where I cannot distinguish the flute sound from the saxophone’s sounds. The organ enters to provide the altissimo sounds with a foundation so that the music acquires a forward-moving momentum with a sense of (what I call) inevitability. Having started, there is no turning back: For the first time all three of us are ‘together’, sounding the same mood, and the same story. Our togetherness, sounding brokenness, ‘a wall that has been pushed over’, is retained throughout the remainder of the piece.

Up until this music rendition, our playing had been exploratory and tentative, as we were becoming musically acquainted with one another while grappling with the sonic and symbolic material of Khoi’npsalms. Our improvised collaboration of ‘togetherness’ forced us out of exposed self-awareness and perhaps taught us to be collectively brave. We increasingly relied on being sonically involved to build a collective installation around the material of this psalm.

Collaboration is perhaps about surrendering individuality for the well-being of the collective, but not at the expense of individuality. Instead, when the music improvisation is at its most intense level (as is sounded in the clip that I chose) there is a sense of the affirmation of individuality and equality.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 27

What I also learn from this collaboration is that (what I call) ‘application-involvement’ is even more important than technical facility, because application is a key to taking part, being involved, and being committed. In our country of separate histories with regard to geographical spaces, racial sociality and separated musics, our collaboration is perhaps a metaphorical template that offers a way of dealing with our troubled past: What better reason has one for existing other than to be involved with what is being created in one’s particular time and space, and with one’s particular creative capacities? Collaboration is perhaps an antidote to forced separation and to idle standing-by – as if watching from the outside. Collaboration demands involvement.

THINKING BACK COLLECTIVELY: WHAT DO WE LEARN ABOUT COLLABORATION?

In the quagmire of being sonically human – in and out and between cultures, beliefs and ways of doing – there lies the tension of the sounds that Khoi’npsalms brought to the fore, playing through fragments of six Genevan Psalms, with Khoi memory music, to tell the story.

In the processes of individual listening back (to the clips we had each selected), we learn that collaboration with one another as musicians, and collaboration around a history of harm, combine to make us vulnerable, and create music that is fragile, unsettling, despite (and maybe as a result of) the appearances of triumphant psalms (Psalms 8 and 47) that marked the first half of the music production. (These psalms were sonically so violent, that they served to unsettle us for their sheer force.) After Psalm 45 our emotional-sensing was alerted to agonies perhaps too harmful ‘to play about’, except for the capacity of allowing ourselves ‘to play into’ these harms through the creative space that art offers. We now collectively know that we cannot heal the past, or slip into easy ‘reconciliation’, but we have also learned that we are able to tell the stories as we hear them from our source materials in the interpretative space that art and music theatre offers. Fragility comes with our medium: improvisation, but fragility also comes with the harsh harmed topic that we are speaking to: a shared history that still infests and infects our ways of living and music-making.

Our collaboration ended with a psalm that references rain, crops and harvest, and as the flutist walks out, and the organ quietens, the Khoi memory musician is left alone at the front of the church playing the ‘blik’nsnaar’. The symbol of a pre-colonial person becomes the last person (standing) that bears witness to a complex story. However, there is more: the Khoi music is what ‘holds’ our complex stories, as if to say, in sound, ‘I am here, I hold you; I hold us, whether I play bow, or calabash, or sax, or blik’nsnaar.’ Khoi ‘belongs here’, ‘knows how to live here’, and, as a ‘firming bass’, takes us with: we all are here, together, making newly imagined music.

As a form of decolonial art that speaks from the global South and engages aspects of a harmed past that emanates from colonial encounter, our music theatre used aspects of mimicry and symbolic representation. However, what we were mimicking and representing were also our real and perceived ourselves: we are familiar with the Genevan psalms; with ‘imported religion’; with a South African nation of many heritages; with the harms that emanate from ruthless racial classification; with the perceptions of superiority of certain person-types and of some music-types. A film press release described the musicians in Khoi’npsalms as a flutist

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 28

and organist – ‘two Dutch descendants – and a Khoi descendant’ (International Encounters Documentary Film Festival and film premiere, June 2018). Together with the visible racial classification that our bodies showed to be decolonising (music-making together), it is perhaps our music instruments that were the strongest decolonizing tools – a church organ telling Khoi history; a transverse Western flute sounding notes of lament into a calabash, and a blik’nsnaar, built by Garth from an oil can and strings – that weave us together. These all signify decolonial, new ways of being and sonic storytelling. The capacity of Khoi memory music to perhaps ‘hold us’, is the strongest trace of art that is ‘decolonial’, speaking with a voice that comes from this place, at this time; music playing from a place of harm and sounding into options for a better, caring, more respectful pluriversal world.

DECOLONIAL ART AS INTIMACY

Our storytelling in 2018, metonymic of the historical meeting of cultures, set out to explore some of the violences and erasures that occurred in our past. However, as we worked together, driven by the dramatic energy of live performance, we found that the bringing together of historically impossible relationships of music-making (and friendship) helped us to re-imagine not only trauma, but also aspects of intimacies, care and conflict management amidst remembering.

As we each listened back to our individual clips, we noted, to one another in discussion, some moments of dis-ease with one another: the flutist noted that the organ’s melismatic tropes, at quiet, sensitive times (in Psalms 42, 45) when the stage could perhaps have ‘belonged to’ the Khoi musician, were present; and the Khoi musician noted times when the flutist had become overly prominent (Psalms 47, 62). The organist, in return, noted that there were moments when the two musicians ‘at the front’ seemingly excluded the organist ‘at the back’ (Psalm 65).

We suggest that intimacies, and tensions that are allowed-for in the space of intimacy, lie at the heart of decolonial arts projects that move through troubling history to traverse into archaeological, improvisatory and unexpected engagements with the present.9 We therefore found that, through listening to music-making, we were drawn into a collaboration of companion-ing honesty and of taking pleasure in our music. We found that we were surprised and delighted by the improvised sounds that emitted between us, and showed us inroads to our human natures. We also found that we were challenged existentially, as the production of sounds of horror and anguish, and a meandering into realms of history that senses ghosts not lain to rest, are physically and sensorically and emotionally taxing; emptying. As we listen back, we realise that our collaboration drove us into spaces of openness in our relationships, so that aspects of care, as well as moments of disillusionment with one another, arose. Our performances, and our experiences of ‘re-performance’ (as we listened back to the recording), impacted on our-selves and on our ways of music-making. We found that collaboration, and listening back to collaboration, changed us – in the act, on stage – and enabled us to reflect critically – afterwards, listening back.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 29

1 The authors wish to thank Mario Pissarra (Director: Africa South Art Initiative, University of Cape Town), and Antoinette Theron (musician and artistic researcher, Amsterdam) for their comments made on a draft version of this article.2 Programme notes can be viewed in the section on concept in the article at <http://www.ellipses.org.za/project/khoinpsalms/>. Erasmus, Garth, Francois Blom, Marietjie Pauw & Andrea Hayes. 2020. ‘Improvising Khoi’npsalms’ in Ellipses journal <http://www.ellipses.org.za>, Issue Three http://www.ellipses.org.za/project/khoinpsalms/. An adapted version of the article (with visual editing by Aryan Kaganof) is available at: Erasmus, Garth, Francois Blom, Marietjie Pauw. 2020. ‘Improvising Khoi’npsalms’. Ellipses article adapted and republished in Herri journal, Issue no 4. <https://herri.org.za/4/marietjie-pauw- garth-erasmus-francois-blom/>.3 Blom, Francois, Garth Erasmus & Marietjie Pauw. 2018. Khoi’npsalms (45-minute sound recording of final performance of Khoi’npsalms (8/3/2018, Stellenbosch). <https://soundcloud.com/francois_69/khoinpsalms>.4 The film can be accessed at https://vimeo.com/260032997, as well as on the Ellipses online journal <http://www.ellipses.org.za/ project/khoinpsalms/> and Herri online journal <https://herri.org.za/4/marietjie-pauw-garth-erasmus-francois-blom/>. The film is titled Nege fragmente uit ses khoi’npsalms (‘Nine fragments from six Khoi’npsalms’), and it is a 21-minute film made by Aryan Kaganof (2018). The film makes use of material shot at the four improvised performances and the one rehearsal in the Moederkerk. The section in the film we are referring to takes place at 03’56”-04’23”. Duration of clip: 0’27”.5 The programme note reads: Khoi, wind, water / Psalm 42: Khoi music on bow reminds us of the first peoples who lived at the Cape. These people saw foreign ships with sailors come to land, brought to the tip of Africa by winds from the north and the east. Sailors were shown where fresh water was to be found. Psalm 42 (Bourgeois, 1551) reminds of the thirst for water: Like an antelope in arid stretches of land, my soul thirsts for water, for quiet [...] (Totius, 1937, translated freely).6 The programme note reads: VOC Song of triumph / Psalm 47: Jan van Riebeeck delivered a prayer that was scripted by the VOC when he arrived at the Cape in 1652. The prayer conflates religious justification for land, commerce, power of the VOC, and the subjugation of ‘these wild and barbaric peoples’. The VOC began an imperial reign at the Cape. Psalm 47 (Bourgeois, 1551) claims the Imperial God as the highest King over all peoples: Rejoice, oh nations, rejoice! Clap your hands and testify [...] to the Lord your joy [...] He is King of the heathen [...] He is the highest, He is exalted (Totius, 1937, translated freely).7 The programme note reads: Khoi Song for highest justice / Psalm 45: Khoi music became quiet, erased. For human survival, Khoi persons learnt new languages and new skills. Psalm 45, a love psalm in the Judaic texts, sings of a ‘just’ king, as also scripted by Totius. When the text becomes the poetry of a Khoi speaker, he longs for ‘highest righteousness’. Flute and organ sense an outpouring of emotion, and are drawn to accompany the Khoi narrative: My heart, moved by sensing, will sing intimately, strongly, of a King. My tongue, moved by poetic fire, is like a pen that writes with artistic skill [...] Clothe yourself with weapons for a victorious battle, oh Hero, so that Your Majesty may ride in all glamour and triumph to find highest righteousness [...] From your house of ivory there sounds a wonder-filling stirring of calming string music (Totius, 1937, translated freely).8 The programme note reads: Song of anguish / Psalm 62: Khoi musicians learnt to play new instruments—to adapt. The saxophone (with flute and organ) sounds a song of mourning that becomes a song of anguish. The song wails of a wall that has already been destructed, ‘pushed over’, as in the words of Psalm 62 (Franc, 1542):

Aryan Kaganof, Decolonial intimacy, 2018.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 What do we learn from listening back to a decolonial Khoi’npsalms? 30

For how long, still, do you seek the downfall and injustice done to a man who is deeply in need, oh cruel tormentors? [...] You seek the destruction of a stone wall that has already been pushed over (Totius, 1937, translated freely).9 In an article published in the Ellipses journal <http://www.ellipses.org.za> we discuss how the film that Aryan Kaganof made revealed to us aspects of intimacy and care that emerged amidst large-scale themes of addressing genocide, colonialism and racial prejudice. See the article by Erasmus, Blom, Pauw and Hayes titled ‘Improvising Khoi’npsalms’ in Issue 3 of Ellipses at http://www.ellipses.org.za/project/khoinpsalms/. The article was republished, with an Addendum, on <http://www.ellipses.org. za/project/khoinpsalms/>.

Francois Blom was organist at the Dutch Reformed Church, Stellenbosch West Congregation, South Africa, for eleven years (until 2018), and now free-lances as organist in the Eastern Cape. He is a trained choral singer, an actor, cabaret pianist, choral assistant and accompanist. [email protected].

Garth Erasmus is a visual artist and musician and founding member and chairperson of Africa South Art Initiative (ASAI). Garth plays with groups such as Khoi Khonnexxion, and As Is, and is publishing a book of his work with artist book maker Helène van Aswegen. [email protected].

Esther Marie Pauw’s doctoral artistic research explored intersections of interventionist curating, landscape as critical lens and her performances of South African flute compositions. She improvises with a collective of improvisers at Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation, University of Stellenbosch, where she is also an affiliated research fellow. [email protected].

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER 31

TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER 1

Elisabeth Lebovici Translated by Naomi Vogt

To cite this contribution: Lebovici, Elisabeth, translated by Naomi Vogt. ‘TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 4 (2021): 31–58, http://www.oarplatform.com/expose-show-demonstrate-inform-offer-1/.

PREAMBLE

This text was originally the fourth chapter of the book Ce que le sida m’a fait (What AIDS did to me). It connects the city of New York, and particularly the Lower East Side (with some forays into Times Square), with the transformation of the nature and concept of contemporary art exhibitions. My direct experience of the exhibitions I discuss here left its mark on me, as did an exhibition organized years later by Douglas Crimp and Lynne Cooke: Mixed Use, Manhattan (Reina Sofia, 2010). These exhibitions set about examining how, in the midst of the city’s recession since the 1970s, Lower Manhattan became a central scene for the experimentation of new artistic practices and forms of sexual contact. Thus, this chapter seeks a genealogy for the rather exemplary forms of display manifested through the different versions of Group Material’s AIDS Timeline, at the turn of the 1990s. This genealogy is structured by the idea that the exhibition site can also be a context of and for sociability and public assembly. At a time when HIV/AIDS provoked panic and silence, the time and space of certain exhibitions opened themselves to speech, to information, to exchange, to protest, in short, to the epidemic’s political visibility. All images used for this translation are scanned pages excerpted from Ce que le sida m’a fait, published by JRP Ringier et La maison rouge in 2017.

Our mourning strives to be public, and to engage public institutions, because it is in the public domain that the value of the lives of our dead loved ones is so frequently questioned or denied. Thus the epidemic requires a public art, which might adequately memorialise and pay respect to our dead. — Simon Watney, ‘Memorializing AIDS,’ Parkett, 1993.

Every genealogy is a fiction. There is no such thing. There’s only one genealogy. It takes place in our dreams. Every specific genealogy is a fiction.— Jill Johnston, ‘Untitled’, Marmelade Me, 1998.

OAR Issue 4 / MAY 2021 TO EXPOSE, TO SHOW, TO DEMONSTRATE, TO INFORM, TO OFFER 32

‘The East Village stinks. Garbage covers every inch of the streets. The few inches garbage doesn’t cover reek of dog and rat piss. All of the buildings are either burnt down, half-burnt down, or falling down. None of the landlords who own the slum live in their disgusting buildings. In the winter when temperatures average 0º, these buildings have no hot water or heat, and in the summer at 100º average, roaches and rats cover the inside walls and ceilings.’2 This is how the astounding writer Kathy Acker described the area of Manhattan situated below 14th Street on the urban grid. Since that time, the East Village has undergone a full process of gentrification.3 The word – first coined in 1964 by the sociologist Ruth Glass regarding neighborhoods of London – was also used by Acker’s friend, the writer and lesbian activist historian of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power), Sarah Schulman. ‘Kathy is emblematic to me of one of the stages of gentrification, the forgetting of pioneering artists and their innovative contributions’, she writes. ‘Her death, in the midst of the AIDS crisis, was another elimination of free space, another shrinking of the community of non-corporate thinking. Another victory for the power of homogeneity’.4 For Schulman, the gentrification of minds occurs simultaneously with the urban policies that follow real-estate speculation. Both bear the responsibility for discarding people with AIDS – those who are dying, their lifetime belongings, the partners of those who are dead, as well as gays of color, lesbians, and socially fragile human beings who cannot afford apartments at market rates. Gentrification reshapes the material of lived urban experience. It affects the ways in which people make contact, think, and interact, restricting the availability and viability of the ebullient, inventive forms of culture that are jointly created through the mix of residents and their neighborhoods.