Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

Transcript of Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

Introduction

‘World War I was clearly an important turning point in changing the

conditions that surrounded the birth of eugenics in France as well

as … Germany’. 1 Whilst the fear of depopulation underpinned by a

declining birth rate first emerged following the Franco-Prussian War

of 1870, World War One (WW1) increased and spread this anxiety,

instilling the impression that “quality” had been lost due to the

heavy casualties of able men. This fear is no better exemplified

than within the contexts of France and Germany. France experienced

1.3 million combat deaths as well as having an acutely declining

birth rate since the Franco-Prussian war, 2 whilst Germany’s own

fears of the Minderwetigen (unproductive), underlined by a diminishing

birth rate and degeneration, were sharpened by the psychological and

material devastation of the Treaty of Versailles (1919). By

heightening the effects of degeneration and depopulation WW1

encouraged increased expansion, beyond the limited attention given

to eugenic ideas of both the French Eugenics Society (FES) and the

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rassenhygiene (German Society for Racial

Hygiene or GSRH), before 1914. Whilst William Schneider and Sheila

Weiss have respectively examined the eugenics movements of France

and Germany, there is a significant lack of literature evaluating

the precise impact of WW1 on these movements. Furthermore, the

significance of a comparative context between Europe’s two biggest

military rivals has been overlooked. Therefore, going beyond

recognition of WW1 as a contextual “turning point”, both the short

and long term impact of WW1 will be assessed. Primarily, examination

of ideological shifts in both the FES and GSRH following the war

will highlight immediate post-war demands. Subsequently, the impact 1 Schneider, William H. ‘The Eugenics Movement in France 1890-1940’ in Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 103 2 Ibid, p. 76

129489 1

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

of post-war institutionalisation of eugenics will be assessed with

regards to both societies, before considering the long-term legacies

of the movements. Throughout the essay, comparing the French and

German contexts will uncover specific notions, whilst also

uncovering broader eugenic trends.

The Ideological Effects of the War

During the pre-war context both the FES and GSRH had diverse policy

measures reflecting views from both positive and negative eugenic

standpoints (positive eugenics means encouraging genetically

beneficial actions, whereas negative eugenics would prevent

genetically harmful actions). However, the impact of the First World

War pushed the FES towards positive eugenics. Similarly, in the GSRH

advocates of negative eugenics inspired by social Darwinist’s Ernst

Haeckel and August Weissmann were supressed, instead emphasising the

positive aspect of Rassenhygiene. Comparisons of pre- and post-war

ideas within both societies will highlight the specific impact of

WW1 on eugenic policy in each context.

When the GSRH was established in 1905 the society adopted the

views of its two co-founders, William Schallmayer and Alfred Ploetz,

encapsulating both positive and negative measures. Schallmayer’s

treatise Heredity and Selection in the Life Process of Nations (1903) argued for

rational management of the population to optimise national

efficiency and international power. To do this he encouraged

“fitter” social classes to increase their fertility rate, whilst

espousing negative measures such as sterilisation of the

Lumpenproletariat (mental defectives). The diversity of his programme

was underlined by the “selectionist principle”, popularised by

Haeckel during the late 19th century, which ascribed to the Darwinian

idea that it was possible to pick and choose favoured genotypes via

129489 2

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

the management of the population. 3 Similarly, Ploetz’s ideas also

comprised both positive and negative measures. Based upon

Schallmayer’s previous works, Ploetz popularised the term

Rassenhygiene in The Fitness of Our Race and Protection of the Weak (1895).

Ambiguously translatable as ‘the optimal preservation and

development of the race’, 4 his utopian goal was a conscious

‘control over variation’; 5 the ability to affect germ plasm during

the pre-fertilisation stage. However, whilst control over variation

was a positive measure, his adherence to rational selection inherent

in Rassenhygiene represents pragmatism and contextual logic rather than

strictly adhering to positive or negative eugenics. The ambiguity

over practical goals alongside internationalisation of the society

from 1907 until 1918 meant that the GSRH ‘did not articulate any

specific social policy or proposals’ 6 prior to WW1.

When the FES was founded in 1912 hoping to become a ‘French

society for the study of questions relative to the amelioration of

future generations’, 7 it faced similar policy ambiguities. The FES

had a diverse array of views among its ranks, despite the common

mis-association with wholly neo-Lamarckian principles; Jean-Baptiste

Lamarck theorised during the late 18th century that organisms can

pass on characteristics that it acquired during its own lifetime. 8

Exemplifying diversity, whilst natalists such as Adolphe Landry

3 Schallmayer, Wilhelm. Heredity and Selection in the Life Process of Nations (Gustav Fischer, 1903) 4 Bulmer, Michael. Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry (The John Hopkins University Press, 2003) p. 935 Ploetz, Alfred. The Fitness of Our Race and Protection of the Weak (Gustav Fischer, 1895) p. 226 6 Weiss, Sheila F. ‘The Race Hygiene Movement in Germany 1904-1945’ in Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 237 Eugénique (Vol. 1) (1913) quoted in Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 898 Sapp, Jan. Genesis: The Evolution of Biology (Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 68

129489 3

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

sought to preserve and improve the species via an increased birth

rate, others such as Frédéric Houssay and the society’s post-war

Vice-President Charles Richet supported negative eugenics based upon

the Darwinian rejection of neo-Lamarckism. Articles written before

the war emphasise the diversity of views. Whilst Landry wrote for

the periodical Revue bleu focusing on improving unhealthy elements

whilst ‘fortifying elements of mediocre quality and preserving from

evil those that are healthy’, 9 Richet’s book La Sélection Humaine

perceived neo-Lamarckian measures seeking to improve the gene pool

by changing environmental factors as working against nature, stating

that ‘everything is distorted by our social institutions …

civilization, which did so much for the progress of the individual,

only leads to degradation of the species’. 10 Therefore Richet’s

claim that environment has little effect on hereditarily acquired

characteristics is attributable to Darwinian thought; contradicting

Landry’s neo-Lamarckian depiction that environmental changes were

the cure for social ills. William Schneider states that despite

common association with neo-Lamarckian ideas, ‘perhaps the most

important characteristic about French eugenics in this early period

was its breadth of scope.’ 11

Therefore pre-war policy in both Germany and France was

underlined by breadth. Ambiguity underscored the German context as

the broad policy of Rassenhygiene implied that the GSRH had no clear

adherence to either positive or negative measures. Slightly

differently, ambiguous policy aims in France during the pre-war

9 Landry, Adolphe. ‘Eugénique’ in Revue bleu (1913) quoted in Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 10910 Richet, Charles. La Selection Humaine (Félix Alcan, 1919) (The quote was translated by me and is reproduced without any further alterations from theoriginal source) p. 2211 Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 109

129489 4

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

period were underscored more by diversity than by adherence to a

broad idea. Richet’s theory that the environment only had a small

effect on acquired characteristics suggests that the pre-war society

encompassed both Lamarckian and Darwinian measures; loosely

synonymous with positive and negative eugenics. Notably, neither

society sought to enact influence on policy until after the war, by

which time practical goals were clearer.

Whilst the GSRH adhered to Rassenhygiene and Schallmayer’s

rational efficiency before the war, the conflict increased fears

over population and degeneration, intensifying vastly differing

ideologies within the broader idea; social-democracy became a

synonym for the Berlin branch of the GSRH, whilst pro-Aryanism and

conservatism became synonymous with Munich. Whereas before the war

Ploetz and other conservative academics such as Fritz Lenz didn’t

overly express their “Aryan-Nordic mystique”, the Great War

intensified their Volkish views due to the subsequent migration of

previous colonial subjects. Their racial bias is expressed by their

bitterness toward the new democratic order, opposing Weimar’s

promise to increase social equality as being both biologically and

socially dangerous. Exemplifying such racial fervour is Principles of

Human Heredity and Race Hygiene which Lenz co-authored in 1923. Veering

into the realm of pseudo-science, Lenz and other eugenicists showed

their adherence to Darwinian thought, expressing that the hierarchy

of races was underlined by spiritual differences, or, ‘the sum total

of all nonphysical qualities of the major races’. 12 Illustrating

German culture as the yardstick to which fitness should be measured,

he depicted the Negro race at the bottom of the pile. Whilst Munich

became a hotbed for political reaction and was the home to the

12 Weiss, Sheila F. ‘The Race Hygiene Movement in Germany 1904-1945’ in Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 31

129489 5

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

National Socialist Party, Berlin was Weimar’s biggest supporter. 13

Opposition to the Munich chapter was both terminological and

institutional. Whilst Schallmayer rejected the term Rassenhygiene which

was popularised by Ploetz, Alfred Grotjahn popularised a new term to

counter the term’s racist connotations; Fortpflanzungshygiene

(reproductive hygiene). 14 Furthermore, as a result of conflict

during a meeting at Munich in 1922 the GSRH’s headquarters moved to

Berlin, diminishing the control of Lenz and Ploetz. 15 Significantly,

the Berlin chapter managed to suppress the racist sentiment in

Munich during the early 1920s, partly in response to government

calls for national efficiency, as the GSRH orientated itself towards

positive hygienic measures.

Whereas in Germany the war encouraged divergence underlined by

the ambiguous Rassenhygiene policy, ideological unity was less

difficult for the FES following the war. In October 1919 Prime

Minister Georges Clémenceau exclaimed that ‘if France stops

producing large families, you can put the grandest clauses in the

treaty [of Versailles], confiscate all Germany’s cannon, do anything

you please and it will be no purpose: France will be lost, because

there will be no more Frenchmen.’ 16 His message encouraging an

increased birth rate reflected the loss of 1.3 million soldiers

during WW1; intensifying the historical population problem in

France. This issue encouraged a pro-natalist movement, and in 1920

the Birth Control Law was passed prohibiting the sale or

13 Ibid, p. 3414 Baur, Erwin, Eugen Fischer and Fritz Lenz. Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene (J. F. Lehmann, 1931) p. 162 15 Weindling, Paul. ‘Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Social Context’ in Annals of Science (Vol. 42, No. 3) (1985) p. 30616 Reynolds, Sian. France Between the Wars: Gender and Politics (Routledge, 1996) p. 18

129489 6

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

distribution of birth control and related propaganda. 17 The

ideological effects of WW1 on the FES must be viewed in the context

of this legislation, as members postulated their concerns over the

quality of reproduction. In the immediate aftermath of the law

Richet spoke out against natalists, reminding them of their duty ‘to

assure not a numerous posterity but an elite one. It is not a

question of quantity for us but of quality.’ 18 The concern over

hereditary defects served to unite the FES in order to prevent

unintelligent reproduction. This is exemplified by their first post-

war conference in 1920 entitled “The Eugenics Consequences of War”,

during which the issue of positive versus negative eugenics was

displaced by the desire to regulate state-sponsored natalism.

President Edmond Perrier’s keynote address entitled “Eugenics and

Biology” offered an amended definition of the goals of the FES: ‘To

research, define and spread the means of perfecting the human races

by indicating the conditions which each individual, each couple must

strive to fulfil in order to have healthy and beautiful babies.’ 19

Thus the immediate threat of potentially dysgenic natalism

encouraged a more defined objective underlined by positive eugenics

and neo-Lamarckism in order to prevent the transmission of undesired

traits. Showing the severity of their natalist reservations was

Adolphe Pinard, the forefather of puériculture (management of the

prenatal and postnatal processes), pronouncing in the 1924 National

Assembly that raising the birth rate was only half the task;

‘quantity is not enough. In addition and above all quality is

17 Poston Jr., Dudley L. and Bouvier, Leon F. Population and Society: An Introduction to Demography (Cambridge University Press, 2010) p. 34518 Eugénique (Vol. 2) (1914-22) quoted in Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 12919 Perrier, Edmond. ‘Eugénique et biologie’ in Eugénique et sélection (Librarie Felix Alcan, 1922) p. 2

129489 7

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

necessary.’ 20

Whilst WW1 encouraged divergence and ideological conflict

within the factions of the GSRH, the FES and their desire to

regulate rampant natalism served to unite its less-prominent

advocates of negative eugenics behind a positive course.

Significantly, whilst figures such as Richet espoused negative

eugenics akin to Darwinism, they still categorised themselves as

Lamarckian. Alternatively, adherence to the Darwinian rejected of

acquired characteristics in Germany gave rise to the right-wing

faction in Munich encouraging negative eugenics, which Berlin

eugenicists were able to supress. This key ideological difference

following WW1’s intensification of birth rate decline and

degeneration is therefore that whilst France reacted with neo-

Lamarckian ideas such as puériculture, German adherence to Darwinist

principles, rejecting the possibility of environmentally acquired

characteristics, influenced the rise of both positive and negative

eugenics. However, post-war policy was also influenced and shaped by

the institutional expansion of eugenics.

Institutional Expansion of Eugenics

When the FES restarted its activities after the war, alongside

tightening their pre-war theories of decline and degeneration at the

1920 meeting, ‘the conference was also indicative of a new

organizational strategy of the French Eugenics Society that aimed at

reaching the intellectual, scientific, and political decision makers

in France’. 21 Similarly in Germany, pre-war ideas of race hygiene

had shifted from improvement of the “race” to preventing the decline

20 Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 12921 Schneider, William H. ‘The Eugenics Movement in France 1890-1940’ in Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 77

129489 8

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

of the Volk, meaning that ‘whereas before the war eugenic ideas were

rejected, the toll of the war and the apparent task of

reconstruction immediately afterward had led to a more receptive

attitude.’ 22 Therefore ideology changes in both contexts, by

reflecting immediate post-war needs, can arguably be described as an

effort to make inroads into public administration following

governmental expansion. Whilst this was successful, governmental and

private involvement in eugenics following the war ultimately proved

detrimental to a biological programme specifically based on the

prevention of degeneration and population policy.

The first cabinet-level health ministry (Ministére de

l’hygiéne) was established in France in 1920, as well as the

Committee of Union against the Venereal Peril in 1922, following the

war-time establishment of 65 venereal centres. 23 Similarly,

establishment of the Prussian Ministry of Public Welfare in Germany

the same year included a Committee for Race Hygiene (Beirat fúr

Rassenhygiene) with the role of evaluating ‘scientifically the

racial hygienic legacy of the War, as part of the government

programme of social reconstruction.’ 24 However, both societies soon

found that they were losing control of their eugenic programmes

emphasising both quality and quanitity.

In France, the fears of being associated with rampant natalism

were realised. Whilst Pinard’s pre-war concept of puériculture

encouraged the creation of the Ecole de puériculture in 1920,

natalist groups within the institution such as the Association of

Christian Marriage, overlooked the “quality” aspect instead

22 Weingart, Peter. ‘German Eugenics between Science and Politics’ in Osiris (Vol. 5) (1989) p. 26223 March, Lucien. ‘Some Attempts Towards Race Hygiene in France during the war’ in Eugenics Review (Vol. 10, No. 4) (1919) p. 20424 Weindling, Paul. ‘Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Social Context’ in Annals of Science (Vol. 42, No. 3) (1985) p. 306

129489 9

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

popularising puériculture as the burden of ‘official repopulators’. 25

Similarly in Germany, plant geneticist Erwin Baur recognized an

opportunity to gain funds for the Berlin chapter of the society when

he wrote to the imperial government late in 1917 seeking to ‘awaken

senior health officials in the Reich to the national importance and

cost effectiveness of Rassenhygiene.’ 26 If the GSRH had any hope of

enacting influence in the political sphere they had to disregard

their concerns for quality of human stock, instead concentrating on

the immediate post-war demand for quantity. Additionally,

establishment of the German Society for Population Policy during the

war encouraged strong opposition towards negative eugenics, such as

compulsory health certificates before marriage as well as

sterilisation and abortion; typified by a draft bill in 1918

explicitly ruling out sterilisation and abortion on eugenic grounds.27 Therefore similarly to France, the goal of prevention was largely

displaced by the short-term goal of treating social deficiencies

inherited from the war.

Furthermore, private funding in combination with governmental

expansion encouraged the creation of new institutions to tackle

post-war degeneration and declining birth rate. Establishment of the

National Office of Social Hygiene in France in 1924 exemplifies

this; ‘The establishment of this new office reveals yet another

facet of the postwar organizational politics of health and social

reform in France that affected the eugenics society.’ 28 The

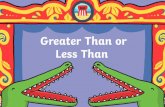

significance of WW1 in its creation is tied directly to the wartime

25 Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 12926 Weiss, Sheila Faith. ‘Wilhelm Schallmayer and the Logic of German Eugenics’ in Isis (Vol. 77, No. 1) (1986) p. 3327 Weingart, Peter. ‘German Eugenics between Science and Politics’ in Osiris (Vol. 5) (1989) p. 26228 Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 135

129489 10

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

battle against tuberculosis. In 1916 a permanent committee (Comité

d’assistance aux militaires tuberculeux de guerre) recommended a law

establishing ‘public dispensaries in connection with social hygiene

and the prevention of consumption’ 29 to screen recruits and soldiers

before discharge; countering the French mortality rate from the

disease which was the highest in Europe at 21.7 for every 10,000

inhabitants. 30 The significance of this new initiative was the

involvement of the Rockefeller Foundation, greatly expanding it into

a mass movement; evidenced by the hitherto unseen use of propaganda

in French politics (see figure 1), as well as that ‘the first 5

years of the tuberculosis campaign … cost over 2.5 million dollars …

more than one-quarter of all the expenditures by the foundation’s

International Health Board in these postwar years.’ 31 Whilst the new

office included eugenicists from the FES such as Andre Honorrat as

president and puériculture pioneer Pinard, the scope and support of the

Rockefeller Foundation entrenched the shift away from prevention in

favour of treatment, marginalising the remaining FES members.

Exemplifying this, the office established services to treat cancer,

venereal disease, alcoholism, typhoid fever, mental health issues

and diphtheria but advanced no prevention techniques. 32 Therefore

despite the fears created by WW1 placing eugenics and members of the

FES in the limelight, by 1924 they were unable to enact any real

influence in regards to their neo-Lamarckian goals of managing

quality and quantity. Instead, ‘the long-range goals of eugenicists

were quickly lost in the effort to meet the immediate needs of

29 Ibid, p. 20230 March, Lucien. ‘Some Attempts Towards Race Hygiene in France during the war’ in Eugenics Review (Vol. 10, No. 4) (1919) p. 20031 Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990) p. 13932 Bashford, Alison and Levine, Philippa. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics (Oxford University Press, 2010) p. 336

129489 11

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

particular groups supported by the office.’ 33

Unlike the French context, whilst individuals within the GSRH

lost control, German concessions were limited to policy and the

society remained prominent throughout the institutionalisation of

eugenics. This key difference is due to a post-war alliance ‘between

public health officials … and geneticists, offering the state

important new technical expertise.’ 34 Exemplifying this, in 1922

leading Prussian health official Otto Krohne took over the

presidency of the GSRH at the same time as it began receiving annual

government grants; the Berlin branch received 3000 marks, whilst the

government sponsored a special society for eugenic propaganda called

the Association for Genetic Improvement (Bund für Volksaufartung),

receiving up to 10,000 marks per annum from 1925. 35 Therefore unlike

the FES concessions were limited to policy. Whilst they were also

forced to focus on treatment rather than prevention, the GSRH

remained central to eugenics programmes. Exemplifying their

prominence throughout the 1920s was the establishment of the Kaiser

Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics

(KWI) in 1927, which like the French National Office of Social

Hygiene, was the culmination of decades of effort to influence

government policy.

As Paul Weindling stated, ‘the origins and obligations of the

Institute cannot be explained without reference to distinctive

features of Weimar genetics, and of the newly defined social role of

science after 1918.’ 36 In 1922 Hermann Muckermann became a prominent

33 Schneider, William H. ‘Toward the Improvement of the Human Race: The History of Eugenics in France’ in The Journal of Modern History (Vol. 54, No. 2) (1982) pp. 282-283 34 Weindling, Paul. ‘Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Social Context’ in Annals of Science (Vol. 42, No. 3) (1985) p. 30635 Idem.36 Ibid, p. 305

129489 12

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

member of the GSRH due to his role as middle-man between the society

and Heinrich Hirtsiefer, a pro-eugenic Minister of Welfare within

the Centre Party. In 1923 Muckermann suggested that a national

institute would best organise disparate eugenicists via a broad-

church approach, however the Reich Ministry of the Interior decided

that the post-war economic context was not favourable, postponing

its establishment. When the KWI was eventually established with help

from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1927, it retained members of the

GSRH including Muckermann and the right-wing faction from Munich;

Erwin Baur, Eugen Fischer and Fritz Lenz. Whilst the FES lost

control following the establishment of the National Office of Social

Hygiene, the KWI represented the culmination of the GSRH’s efforts;

as ‘the keystone in a grand eugenic edifice.’ 37

Notably, both the French and German governments were attracted

to the concept of “hygiene” during the post-war era. Whilst the FES

adopted the concept in their first post-war conference in 1920, the

notion of “hygiene” was attributed to Wilhelm Schallmayer’s

pioneering treatise entitled Concerning the Threatening Physical Degeneration

of Civilized Humanity (1891) by Alfred Ploetz in 1895; influencing the

GSRH since its establishment in 1910. Importantly, the terms

original meaning is the combination of social health with individual

hereditary sought to impart a ‘rational influence upon human

selection’. 38 Thus, “hygiene” has a much broader scope than the

English word “eugenics”, including ‘not only all attempts aimed at

“improving” the hereditary quality of the population but also

measures directed toward an absolute increase in population.’ 39

37 Weindling, Paul. ‘Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Social Context’ in Annals of Science (Vol. 42, No. 3) (1985) p. 30938 Schallmayer, Wilhelm. Ueber die drohende physische Entartung der Culturvölker (Louis Heuser, 1891) p. 939 Weiss, Sheila Faith. ‘Wilhelm Schallmayer and the Logic of German Eugenics’ in Isis (Vol. 77, No. 1) (1986) p. 33

129489 13

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

Therefore complying with “hygiene” measures in the post-war period

highlights that whilst policy was directly influenced by WW1,

adhering to “hygiene” can also be seen as a compromise effort to

attract government interest in order to influence broad social

programmes highlighted by both government’s short-term goals.

Therefore in both France and Germany immediate post-war fears,

such as birth-rate decline and tuberculosis, encouraged the

institutionalisation of eugenics; suppressing long-term goals of

quality during the reconstruction period in order to enact

influence. However, despite adhering to “social hygiene” the FES was

displaced in the French movement, whilst the GSRH remained prominent

in Germany; exemplified by the establishment of the KWI in 1927.

Underlying this was the fact that whilst the French National Office

of Social Hygiene was an expansion of a wartime establishment which

the FES had nothing to do with, the KWI represented the culmination

of both Berlin and Munich’s post-war eugenic ideas. Despite this

difference, both the FES and GSRH had significant legacies.

The Legacy of post-War Eugenics

Ideologies and institutions established in the aftermath of WW1

proved significant throughout subsequent decades in both German and

French eugenic movements. Individuals within the Munich faction

directly influenced Hitler’s works, as well as contributing to

Nazism through the KWI. Whilst the French context is less dramatic,

the post-war premarital examination was subsequently adopted by the

Vichy regime, whilst Pinard’s puériculture played a significant role in

creation of the Popular Front.

When Lenz, Fischer and Erwin Baur collaborated to write

Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene in 1923, they feared that WW1 had

129489 14

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

led Germany to the brink of eugenic disaster. 40 The views expressed

in Principles are underlined by the Darwinian idea that degeneration

cannot be improved by the environment, stating that migration of

previous subjects from Africa and South America to Germany under the

terms of the Treaty of Versailles will cause a cultural decline in

intelligence as well as degeneration. The low birth rate of the

upper classes will exacerbate the problem, leaving Germany with a

‘destitute proletariat’. 41 Inherent to this theory is belief in the

pseudo-scientific idea of racial hierarchy, as they argue that the

Volk (mixture of different peoples) will be fundamentally altered by

interbreeding; encouraging a decline of German culture due to the

introduction of diverse races. For example, whilst commending Jewish

intelligence, the book discusses ‘their strong sense of tribal

interdependence’ 42 on Teutonic people; denoting minority status for

the Jewish race. This post-war theory created by key members of the

Munich faction was then expanded by Hitler in the programme of

racial purity and Aryan supremacy visible in Mein Kampf; Lenz himself

boasted about the books influence on Hitler’s philosophy. 43

Perhaps more important than influencing Nazism was the co-

operation of eugenicists in the KWI. The role in which Baur, Fischer

and Lenz played under National Socialism within this institution

further exemplifies WW1’s legacy on German eugenic thought.

Demonstrating this, ‘none reveals the continuity between pre- and

post-1933 race hygiene better than the sterilization law.’ 44 The 40 Idem.41 Baur, Erwin. ‘Eugenics in the New Germany’ quoted in Glass, Bentley. ‘A Hidden Chapter of German Eugenics between the Two World Wars’ in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (Vol. 125, No. 5) (1981) p. 36442 Baur, Erwin, Eugen Fischer and Fritz Lenz. Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene (J. F. Lehmann, 1931) pp. 673-674 43 Glass, Bentley. ‘A Hidden Chapter of German Eugenics between the Two World Wars’ in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (Vol. 125, No. 5) (1981) p. 36344 Weiss, Sheila F. ‘The Race Hygiene Movement in Germany 1904-1945’ in Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia

129489 15

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

“Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring” was

introduced in 1933 based upon a proposal initiated by Muckermann

allowing mandatory sterilisation of the “unfit”. Significantly, as

director of eugenics in 1934 Lenz believed that the concept was too

narrow, broadening the law into sterilising ‘1 million feebleminded,

1 million mentally ill, and 170,000 idiots in “the social

interest.”’ 45 Notably, whilst the initial proposal suggested no

racial bias, Lenz’s inherent correlation between race and

intelligence, as depicted in Principles, arguably hinted that such

expansion was underlined by Nordic prejudice. In a similar vein,

Fischer’s leadership of the anthropological division gave him

responsibility for genetic analysis of race-crossing, as well as

executing the sterilisation law by providing Gutachten (expert

testimony) for the genetic health courts. Therefore, ‘far eclipsing

the Munich institute in importance, Berlin’s KWI for Anthropology,

Human Heredity, and Eugenics remained the institutional center of

German race hygiene research throughout the Nazi period.’ 46

Whilst not as striking as providing the underbelly to National

Socialism, ideologies and the institutionalisation of FES policies

following WW1 also proved to have a significant legacy. Primarily,

whilst the 1920 post-war conference was almost wholly espousing

positive eugenics, there was one exception. Georges Schreiber

presented “Eugenics and Marriage”, conveying that the dysgenic

effects of war made more pertinent the need for a physical

examination prior to marriage in order to eradicate “hereditary”

diseases such as tuberculosis, syphilis, alcoholism and others. 47

Following usurpation of their eugenic cause by government ministries

(Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 4345 Ibid, p. 4446 Ibid, p. 4547 Schreiber, Georges. ‘Eugénique et Mariage’ in Eugénique et selection (Librarie Felix Alcan, 1922) pp. 172-182

129489 16

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

as a result of the war, the FES underwent significant personnel

changes; President Perrier died in 1921, Richet retired from

medicine in 1925 as did Lucien March, whilst Pinard’s political

career occupied his time. Amongst the changes, Schreiber became

Secretary-Treasurer of the Office of Social Hygiene in 1925. Renewed

attention to negative measures under a newly organised FES is

exemplified by Schreiber’s leadership of the campaign for “The

Prenuptial Medical Examination” in 1926; the society’s first

concrete legislative proposition. 48 Whilst the proposition was side-

tracked by the Great Depression which cut back government funding

and focused on more extreme negative measures, exemplified by the

proposition of a sterilisation bill in 1933, Schreiber’s pre-marital

exam resurged a decade later. In 1942 the Vichy regime passed a law

requiring a pre-marital examination as part of Germany’s imposition

of strict ‘National Regeneration’, 49 a law still in existence today.

Whilst the regime had clear ties with Nazi eugenicists, the

legislation was clearly influenced by Schreiber’s idea following the

war.

Whilst the premarital law represents the legacy of negative

post-war eugenics in France, the actions of the French Communist

Party (PCF) in the 1930s emphasises positive eugenics. In reaction

to the rise of right-wing movements in France as well as Nazism,

Maurice Thorez sought to unite the French left and centre groups by

broadening the appeal of the Communist Party, subsequently

discussing motherhood, children and country whilst emphasising the

need for quality. To attract centrists, Thorez highlighted that

contrary to bourgeois belief, workers and peasants do not always

48 Schneider, William H. ‘Toward the Improvement of the Human Race: The History of Eugenics in France’ in The Journal of Modern History (Vol. 54, No. 2) (1982) p. 28449 Lackerstein, Debbie. National Regeneration in Vichy France: Ideas and Policies, 1930-1944 (Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2012) p. 229

129489 17

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

want children, ‘they are afraid of not being able to give birth to

children in full health, robust and intelligent instead of being the

misfortunates who will only know a life of misery.’ 50 Notably, the

PCF began formulating a family policy akin to neo-Lamarckian

eugenics in 1935 in L’Humanité. Refinement of the policy led to a bill

in 1936, further reflected eugenic ideas; as Paul Vaillant-

Couturier’s statement that ‘the guiding principle of our proposition

resides in the recognition of motherhood as a social function’ 51

highlights. More significantly, virtually every part of Pinard’s

puériculture was included; from surveillance of pregnant women, to a

longer rest period before and after pregnancy the encouragement of

breast-feeding. Recognising the significance of puériculture in post-

war policy, alongside the popularisation of eugenic discussion, the

French Communist Party joined the eugenic debate, adopting the

populist policy which Pinard had embedded within French culture

during the early 1920s.

Therefore the long lasting impact of post-war eugenics is

exemplified in a number of ways. Degeneration and birth-rate decline

following the war encouraged Baur, Fischer and Lenz to write

Principles. Despite it being overlooked in the immediate post-war

period, adherence to the ideas of racial purity subsequently

influenced Hitler’s thinking. Additionally, the post-war incarnation

of the KWI played a pivotal role under National Socialism. In

France, Schreiber’s premarital examination, also ignored during the

immediate post-war period, was influential in establishing a

cornerstone of France’s marriage laws. Equally, puériculture was

utilised to provide the PCF with a political platform which 50 Thorez, Maurice. ‘Rapport á l’Assemblé Communiste du Paris’ (1935) quotedin Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 99 51 Schneider, William H. ‘The Eugenics Movement in France 1890-1940’ in Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (Oxford University Press, 1990) p. 100

129489 18

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

catalysed the rise of the Popular Front during the mid-1930s.

Importantly, the legacies of both the GSRH and the FES highlight

that whilst eugenic ideas were not relevant in the immediate post-

war context, which emphasised reproduction, they were largely

relevant following the Great Depression and the socio-economic

changes this caused; notably attributed to radical far-right and

populist movements.

Conclusion

WW1 had a significant impact on both the FES and the GSRH. Fears of

the quality of genetic stock served to unite pre-war differences

within the FES behind positive eugenics in order to prevent

unintelligent natalism, whilst the war served to factionalise the

GSRH. Underlining this, whilst adherence to positive eugenics was

underlined by Lamarckian ideas that the environment effects

inherited characteristics, the GSRH followed the Darwinian idea that

they could not. Furthermore, whilst both societies conceded quality

following the war, a German post-war alliance between health

officials and eugenicists kept them central to their movement.

Contrarily, the FES lost control due to the wartime creation of what

became the National Office of Social Hygiene. Whilst this was

largely misfortune than anything else, legacies in both countries

also highlight the fundamental difference between France and

Germany. Respectively, whilst neo-Lamarckism was representative of

French positivism and Revolutionary spirit, Germany’s adherence to

the Darwinian idea highlights post-defeat insecurities; this was

highlighted by Lenz’s believe in the decline of German culture which

influenced pro-Aryanism. Whilst the Darwinian “selectionist”

principle advanced by Baur, Lenz and Fischer encouraged negative

eugenics, as was later espoused in the KWI, Lamarck’s ideas inspired

129489 19

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

the resurgence of puériculture following the Great Depression, and only

mild negative measures such as the premarital examination under the

Vichy Regime. Notably, contextual influence of both WW1 and its

legacy following the Great Depression emphasises significant

differences between the FES and GSRH. Broadly speaking, despite

following familiar themes such as ideological changes and

institutionalisation, WW1 had strikingly different effects depending

on underlying eugenic ideas. Conclusively, the war proved to be an

influential turning point within both France and Germany,

encouraging the rise of both neo-Lamarckian and Darwinian ideas and

institutions that would retain influence for decades, whilst

emphasising the importance of contextual influence on socio-

scientific thought.

129489 20

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

Appendix

Figure 1 - Poster created by the Rockefeller Foundation for the tuberculosis campaign

129489 21

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

Translation: “The German eagle will be defeated, tuberculosis should be too.”Source: Dorival, Geo, ‘L'aigle boche sera vaincu la tuberculose doitl'être aussi’ (1918) in 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation (Accessed April 30, 2015) [http://rockefeller100.org/items/show/2258]

Bibliography

Primary SourcesBaur, Erwin, Eugen Fischer and Fritz Lenz. Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene (J. F. Lehmann, 1931)Dorival, Geo, ‘L'aigle boche sera vaincu la tuberculose doit l'être aussi’ (1918) in 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation Levy, Georges. ‘For a Policy of Protection for the Family and Childhood’ inCahiers du Bolchevisme (Vol. 16) (1939) March, Lucien. ‘Some Attempts Towards Race Hygiene in France during the war’ in Eugenics Review (Vol. 10, No. 4) (1919) Perrier, Edmond. ‘Eugénique et biologie’ in Eugénique et sélection (Librarie Felix Alcan, 1922)Ploetz, Alfred. The Fitness of Our Race and Protection of the Weak (Gustav Fischer, 1895)Richet, Charles. La Selection Humaine (Félix Alcan, 1919)Schallmayer, Wilhelm. Heredity and Selection in the Life Process of Nations (Gustav Fischer, 1903)Schreiber, Georges. ‘Eugénique et Mariage’ in Eugénique et selection (Librarie Felix Alcan, 1922)

Secondary Sources Adams, Mark B. (ed.) The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia

129489 22

Compare the impact of the First World War on the eugenics movements in France and Germany

(Oxford University Press, 1990) Bashford, Alison and Levine, Philippa. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics (Oxford University Press, 2010)Bulmer, Michael. Francis Galton: Pioneer of Heredity and Biometry (The John Hopkins University Press, 2003)Glass, Bentley. ‘A Hidden Chapter of German Eugenics between the Two World Wars’ in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (Vol. 125, No. 5) (1981) Lackerstein, Debbie. National Regeneration in Vichy France: Ideas and Policies, 1930-1944 (Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2012) Poston Jr., Dudley L. and Bouvier, Leon F. Population and Society: An Introduction to Demography (Cambridge University Press, 2010)Reynolds, Sian. France Between the Wars: Gender and Politics (Routledge, 1996)Sapp, Jan. Genesis: The Evolution of Biology (Oxford University Press, 2003)Schneider, William H. Quality and Quantity: The Quest for Biological Regeneration in Twentieth-Century France (Cambridge University Press, 1990)Schneider, William H. ‘Toward the Improvement of the Human Race: The History of Eugenics in France’ in The Journal of Modern History (Vol. 54, No. 2) (1982)Weindling, Paul. Health, Race and German Politics between National Unification and Nazism, 1870-1945 (Cambridge University Press, 1989) Weindling, Paul. ‘Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Social Context’ in Annals of Science (Vol. 42, No. 3) (1985)Weingart, Peter. ‘German Eugenics between Science and Politics’ in Osiris (Vol. 5) (1989) Weiss, Sheila Faith. ‘Wilhelm Schallmayer and the Logic of German Eugenics’in Isis (Vol. 77, No. 1) (1986)

129489 23