charles-édouard brown-séquard - CiteSeerX

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of charles-édouard brown-séquard - CiteSeerX

Charles Édouard Brown (Fig. 1) was bornin 1817 at Port Louis, the capital city ofthe island of Mauritius, located 550 miles

east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Hisfather, Edward Brown, an American of Irishdescent, was originally from Philadelphia and amerchant sea captain. His mother, Mademoi-selle Séquard, was of French descent and hadsettled in Mauritius when it was a Frenchcolony (2, 5, 9, 11). At the time of CharlesBrown’s birth, however, the island had beenceded to British rule, and, thus, Charles Brownwas a British citizen by birth, a fact that wouldgreatly affect his future career (36).

A major calamity occurred while Mlle.Séquard was pregnant. During a voyage toIndia to obtain rice for Mauritian islanderswho were dying from famine, Edward Brownwas lost at sea. It is probable that he wasdrowned in a heavy monsoon or killed bypirates. Thus, Charles Brown was born father-less. His mother was forced to work as a seam-

stress and struggled to raise her son. When heturned 15, Charles took a job as a clerk in thegeneral store at Port Louis, where he hadaccess to the books on the shelves of the store(21). He attempted to write poems and plays,which seemed to have been well received bylocal critics. At the age of 20, life was becominghard for Charles and his mother, and theymade the decision to leave Mauritius forFrance in the hope of finding a better life (5,39). Once in Paris, Charles Brown’s literarywork was evaluated by the academicianCharles Nodier, who concluded, “My youngfriend, you must take a trade to live” (10). Onthe basis of this brusque advice, Charlesdecided to study medicine (25, 32). He workedsteadfastly in pursuit of this craft, spendingapproximately 18 hours a day learning andworking, a habit he maintained for the rest ofhis career. His mother supported him throughthe modest income she attained from running

954 | VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 www.neurosurgery-online.com

LEGACIES

Setti S. Rengachary, M.D.Department of Neurosurgery,Wayne State UniversitySchool of Medicine andDetroit Medical Center,Detroit, Michigan

Chaim Colen, M.D.Department of Neurosurgery,Wayne State UniversitySchool of Medicine andDetroit Medical Center,Detroit, Michigan

Murali Guthikonda, M.D.Department of Neurosurgery,Wayne State UniversitySchool of Medicine andDetroit Medical Center,Detroit, Michigan

Reprint requests:Setti S. Rengachary, M.D.,Department of Neurosurgery,Wayne State UniversitySchool of Medicine andDetroit Medical Center,4160 John R Street, Suite 930,Detroit, MI 48201.Email: [email protected]

Received, July 11, 2007.

Accepted, October 3, 2007.

CHARLES-ÉDOUARD BROWN-SÉQUARD:AN ECCENTRIC GENIUS

BROWN-SÉQUARD IS known eponymously for the syndrome of hemisection of thespinal cord, but most clinicians are not familiar with his colorful, quixotic, and eccen-tric life history. His contributions to medicine and neuroscience reached much furtherthan his discovery of the spinal hemisection syndrome. He lived in five countries onthree continents and crossed the Atlantic 60 times, spending a total of almost 6 yearson the sea. He contributed more than 500 papers in his lifetime, was even the editor ofmany prestigious journals, and spent his last years as Professeur au Collège de France,a most coveted position for a French neuroscientist. Many are not aware of his contri-butions to endocrinology and hormone replacement therapy, even those who considerhim the father of modern endocrinology. Brown-Séquard was a skillful experimental-ist. He pioneered the concept of the advancement of neuroscience through experimen-tal physiological observation. He was devoted to science. He was not interested inmonetary gains through his inventions or patient care. Although he may be criticizedfor arriving at some incorrect conclusions from his experiments, his visionary ideas andprescient statements have stood the test of time; he truly was an eccentric genius. Thisarticle highlights Brown-Séquard’s life history, specifically his time in France and NorthAmerica, and his contributions to neuroscience and endocrinology.

KEY WORDS: Brown-Séquard, Brown-Séquard elixir, Endocrinology, Hormone replacement therapy,Neuroscience, Self-experimentation, Spinal cord, Spinal hemisection syndrome, Spinal sensory physiology,Sympathetic vasomotor nerves

Neurosurgery 62:954–964, 2008 DOI: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000297136.38560.D0 www.neurosurgery-online.com

Because of his excellence inexperimental physiology,Brown-Séquard was invitedto serve as secretary of theSocietie de Biologie, a presti-gious scientific association inFrance. During his tenurewith this organization, Brown-Séquard became acquaintedwith Claude-Bernard (1813–1878), 10 years his senior,who established the scientificmethod in medicine. Thisrelationship quickly becamerivalrous, competitive, friendly,and mutually respectful; theyexchanged many emergingideas in experimental physi-ology.

However, not all was wellfor Brown-Séquard at thisperiod of his life. He wasunder a great deal of stressfrom combined financial inad-equacy, lonely life, and longhours of tedious research withno avenues for relaxation. In a

later autobiographical note, he stated “…a scientific man, 34years old, of strong constitution, but reduced from several causesto a lamentable state of health…for eight years he had beenworking very hard, taking no exercise and living almost all thetime in a vitiated atmosphere…he slept very little and spent 18or 19 hours a day writing, reading, or experimenting. His dietwas miserable and with the object of avoiding the need of muchfood, he took a great deal of coffee. He gradually, though slowly,became exceedingly weak” (11).

With the help of his friends, however, Brown-Séquard’s lifeslowly improved. Unfortunately, the political climate in Francetook a turn for the worse; the President of the French Republicdissolved Parliament and moved to transform himself as anemperor. Brown-Séquard’s life was at risk because of his repub-lican views (7).

Despite these personal setbacks, Brown-Séquard dreamt ofbeing selected as a Professeur au Collège de France, a mostcoveted position in France at the time. However, he was aBritish citizen by birth, and the rules and regulations prohibiteda foreign national from becoming a professor at the collegedespite his enormous academic achievements. Brown-Séquarddecided to move to the United States in the hope of finding bet-ter opportunities. He carried a letter of reference from PaulBroca (1824–1880) (Fig. 3), which stated: “For eight years BrownSéquard has exhausted his resources and imposed upon him-self incredible sacrifices in order to carry out expensiveresearches in experimental physiology. Today he has nothingleft save an honorable character, profound erudition and scien-tific articles which everyone can appreciate” (36).

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 | 955

CHARLES-ÉDOUARD BROWN-SÉQUARD

a boarding house for Mauritian students (30), where Browntutored his fellow students to support himself.

Brown’s mother died unexpectedly while he was in medicalschool. This loss affected him immensely, and he impulsivelyreturned to Mauritius. A quick decision to move from one coun-try to another, and a long sea voyage, seemed to set a patternthat Brown would adopt whenever he was under extreme pres-sure and emotionally drained. He is said to have crossed theAtlantic 60 times in his life, spending a total of 6 years at sea. Hisstay in Mauritius did not last long, and Brown returned to Paristo complete his medical degree. He spent his time in the labora-tory of a noted physiologist, Martin-Magnon, and completed hisdoctoral thesis on spinal cord physiology in 1846, which earnedhim the medical degree he had long coveted (Fig. 2). He dedi-cated his doctoral thesis to his mother as an expression of hisgratitude for her lifelong support. In addition, Brown adoptedher surname and designated himself Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard (8, 30).

Brown-Séquard’s thesis was entitled “Researches andExperiments on the Physiology of the Spinal Cord.” In it, hehinted that sensory pathways may cross over to the oppositeside in the spinal cord, not at the level of the cerebellum, whichwas the prevailing opinion at the time: “I should point outanother important fact, shown by my experiments, the facilitywith which sensory impressions are transmitted from one sideof the cord to the other” (4). This was a radically new idea.

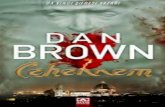

FIGURE 1. Brown-Séquard was an “eccentric genius”and a foremost neurophysiologist of the 19th century. Inaddition to the syndrome bearing his name, he discov-ered the functional significance of sympathetic vasomo-tor nerves. He conducted several experiments on him-self, endangering his own life. His greatest contributionwas his serendipitous discovery of hormone replacementtherapy; he is the father of modern endocrinology. Hedevoted his entire career to the benefit of mankind.

FIGURE 2. Brown-Séquard’s 1846thesis, entitled “Researches andExperiments on the Physiologyof the Spinal Cord,” qualified himas a doctor of medicine. This thesiswas dedicated to his mother in grat-itude for her support. A copy of thefull text is available at http://web2.bium.univ-paris5.fr/livanc/?cote�

TPAR1846�002&do�pages.

Brown-Séquard chose Phil-adelphia as his port of entryfor two reasons. First, Phila-delphia was his father’s home-town, so he had a sentimentalattachment to the city. Second,Philadelphia was the home ofthe most respected and oldestmedical school in the UnitedStates.

Over the Sea and Back, Twice

Up to this point, Brown-Séquard did not speak English.He decided to teach himselfthe language during themonth-long transatlantic voy-age, and he chose a slower shipto allow himself more time.When he reached the UnitedStates, he sustained himselfteaching French lessons anddelivering babies for a fee of$5 each. He traveled exten-

sively and gave several stunning lectures at various medicalcenters; many of these were published in the Boston Medicaland Surgical Journal (5). Tributes were paid by local newspaperssuch as the New York Tribune and Philadelphia Medical Examinerfor Brown-Séquard’s introduction of the concepts of scientificmethodology in physiology to North America.

In 1853, he met and married Miss Ellen Fletcher, the niece ofGrace Fletcher, who was the first wife of Daniel Webster, one ofthe greatest statesmen and politicians of his time. After his mar-riage, Brown-Séquard decided to return to his hometown ofPort Louis (28). Unfortunately, there was a cholera epidemic inMauritius; Brown-Séquard instantly volunteered himself toestablish a treatment unit in the local hospital, and he personallyundertook all efforts to quell the epidemic. The local authoritiesawarded Brown-Séquard a medal for his contributions in treat-ing the cholera victims.

At this time, the Medical School of Virginia, now a part ofVirginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond, was at-tempting to establish a Professorship in Physiology andMedical Jurisprudence; Brown-Séquard was nominated for thepost. There was some initial reluctance to select a foreigner tothis newly established position, but a letter of support fromPaul Broca allayed any fears: “He is not a Frenchman, althougheducated in Paris and speaking the language like one of us;although acknowledged to be possessed of eminent talent, hehas nevertheless been unable to obtain any official position,only because he was a foreigner” (2).

The newly arrived “eccentric genius” taught in the recentlyconstructed Egyptian Building (Fig. 4). The Egyptian architec-ture was chosen because “there is mystery in the spirit ofEgyptian style of architecture which makes it to our taste singu-

larly appropriate for this temple of medical science” (13). TheEgyptian theme is particularly appropriate because Imhotep isthought to be the first physician known by name in history. Theclassroom in the Egyptian Building has been the oldest contin-uously used classroom in any medical school in North America;the building and its related facilities housed the ConfederateArmy during the Civil War, and the hospital was used to treatConfederate soldiers. “What old Nassau Hall is to Princeton,what the Wren Building is to William and Mary, what the Ro-tunda is to the University of Virginia, the Egyptian Building isto the Medical College of Virginia” (13).

Brown-Séquard delivered lectures in the upper-level class-room and performed his experiments in the lower level (16).However, things did not always go well. Taylor, one of Brown-Séquard’s students, recalls the professor having considerabledifficulty in expressing himself because of the language barrier:

Dr. Brown-Séquard was my teacher, yet reluctantly Imust say he did not teach me anything. But let me has-ten to explain that this was not owing to any want ofcapacity of the reservoir, which was indeed superabun-dantly full, but to the inadequacy of the receptaclewhich was completely swamped by the copiousnessof the overflow. His expositions were far beyond thecomprehension of a medical neophyte, and I questionif I do any injustice to the great lights of the professionof the day when I say that even some of them staggeredunder the weight of his elementary fact and principles.He was, in truth, one of those not very uncommon

956 | VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 www.neurosurgery-online.com

RENGACHARY ET AL.

FIGURE 3. Paul Broca was astaunch supporter of Brown-Séquard. He generously providedrecommendation letters for Brown-Séquard to obtain academic positionsin the United States. Broca was alsoa member of the committee commis-sioned by the Societe de Biologie thatvindicated Brown-Séquard’s work inspinal sensory physiology.

FIGURE 4. The Egyptian Building at the MedicalCollege of Virginia in Richmond. The oldest continu-ously used classroom in a North American medicalschool is located on the upper floor of the EgyptianBuilding. Brown-Séquard taught in this classroom andconducted animal experiments in the basement. As hehad no formal method of procuring experimental ani-mals, his students roamed around Richmond collectingwhatever stray animals they could find. He is thoughtto have completed his seminal work on spinal cord sen-sory physiology in this building. The building alsoserved as a hospital outpost for the Confederate Armyduring the Civil War.

teachers, who very wise themselves, yet do not knowenough to understand how very ignorant their pupilsare. Moreover, his ability to speak the English languagefluently was far from first rate. A discourse rendered byhim was not very unlike an attack of spasmodicasthma, and frequently his agony in trying to makehimself comprehended, was, if anything, greater thatours in trying to comprehend him (43).

In contrast, Brown-Séquard’s practical demonstrations werefirst class; they were “like wonders wrought by a stage magi-cian” (38). He was a very skilled vivisectionist, thoroughgoingwithout exerting wanton cruelty. He treated his subjects as wellas the circumstances of the case permitted, and he would patthe dogs on the head and whistle lullabies while he was oper-ating on them. However, he did not let his humanity stifle hisscientific exploration.

Moreover, at the time, there was no designated animal carefacility at the Medical School of Virginia; to assist Brown-Séquard, his medical students: “…had gathered together forhim an innumerable caravan of dogs and cats and raccoons andterrapins and specimens of nearly every other variety of theinferior forms of animal life which roamed the fields or thewaters or the streets or the housetops of Richmond and HenricoCounty, and all these were quartered in harmonious juxtaposi-tion with one another in the depths of the college cellar” (43).One of his students recalls, “holding the cats by the tail, whilethe Professor worked his way into their insides” (43).

Unfortunately, conflict brewed between Brown-Séquard andRichmonders in general and specific school officials in particu-lar. The constant growling, roaring, and bellowing noise fromthe animal storage area disturbed the sleep of the students; “thejanitor and his wife aged rapidly and would have perished frominsomnia and compound comminuted delirium tremens if themenagerie had held together a month longer” (43). Brown-Séquard was so engrossed in teaching and experimentation,constantly thinking of new ideas, that he had no time left forsocializing with colleagues. His inability to express himself influent English irked those who were opposed to a foreign intel-lectual being awarded a teaching position in the newly estab-lished medical school. In addition, his republican ideas andabhorrence of slavery did not fit well with the prevailing idealsin the Confederate stronghold. The concurrence of these situa-tions and problems led Brown-Séquard to conclude that he wasa misfit and to depart from the United States.

Nevertheless, trouble seemed to follow him across the sea toFrance. On his arrival in Paris, a conflict was brewing onwhether Brown-Séquard’s most important contribution to neu-roscience, the idea that sensory pathways cross at the level ofthe spinal cord, was an accurate observation. Brown-Séquardchallenged the Societie de Biologie to conduct an independentassessment. At his request, a committee was created comprisedof the most prominent French neurologists and neurophysiolo-gists of the time: Paul Broca, Claude-Bernard, and Vulpian, withClaude-Bernard leading the committee (Fig. 5). Brown-Séquardwas given the opportunity to present his ideas, supplemented

by live demonstration of the experiments. His great operativeskill was clearly evident as were the logical conclusions from theexperiments. A verdict was finally issued through Broca, whichvindicated the conclusions of Brown-Séquard on the basis of hisexperimental results. This result boosted his reputation as anauthority on spinal cord physiology; many more accolades fol-lowed after the committee’s decision was made public.

Brown-Séquard at Harvard Medical SchoolIn the mid-1860s, Brown-Séquard was rapidly gaining a rep-

utation on both sides of the Atlantic as a foremost experimen-tal physiologist in the same rank as Claude-Bernard, FrancoisMagendie, and others. Coincidentally, the administrators atHarvard Medical School in Boston were considering a com-plete revamp of the medical school curriculum to includeexperimental physiology. Up to that point, the Harvard facultyhad primarily consisted of private practitioners who also gave

FIGURE 5. Illustration of a gathering of the members of the Societe deBiologie, an organization that promoted the true spirit of science throughpassionate, heated discussions and exchange of ideas. Brown-Séquard isstanding second from the left (with a white beard); Claude-Bernard isstanding second from the right (wearing an apron).

FIGURE 6. An admission ticket issued to students ofHarvard Medical School to attend one of Brown-Séquard’s lectures. Brown-Séquard was the first profes-sor of physiology and pathology at Harvard.

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 | 957

CHARLES-ÉDOUARD BROWN-SÉQUARD

lectures in the school for a fee charged to each student; therewere no provisions for experimental research. America wasbehind Western Europe in this regard; Harvard administratorswere cognizant of this fact and wanted to remedy the situation.At the same time, Brown-Séquard was seeking an academicposition to pursue his research. The goals of the school and thescientist seemed to coincide.

The transition of Brown-Séquard to a newly created positionas the first professor of physiology and pathology of the nerv-ous system was not as smooth as anticipated. Tyler and Tyler(44), two contemporary neurologists at Harvard MedicalSchool, located more than 50 documents, primarily throughthe Countway Library, that included unpublished letters, min-utes of faculty meetings, and other documents (Fig. 6). Theypainstakingly analyzed the career and performance of Brown-Séquard at Harvard during a 3-year period. The results of theanalysis are not as positive as one would anticipate, given thesynergy between the needs of the medical school and the rep-utation of Brown-Séquard as an experimentalist.

Brown-Séquard’s behavior during his tenure at Harvardwas unpredictable, impulsive, inconsiderate, and wavering. Hetendered his resignation to Dean Shattuck on as many as sixoccasions, only to withdraw it each time. Reasons given for hisresignations included physical ailments (headaches), the deathof his wife, friction with his Boston in-laws (“There is alsoanother decisive reason for my resignation, and that is thatwhatever may be my future home, whether in the United Statesor abroad, it will not be in Boston” [3]), poor salary, a busy lec-ture schedule, inadequate setting for his experimental animals,and lack of an assistant to share his burden to give lectures andassist in experiments. Dean Shattuck, after receiving each res-ignation letter from Brown-Séquard, did not submit them to theMedical School Corporation, anticipating that Brown-Séquardwould change his mind and withdraw the resignation.However, Shattuck was correct only five of the six times, andthe final letter proved to be mutually acceptable to both parties.

PROFESSIONAL COLLABORATIONS

Brown-Séquard and Weir Mitchell

Recently, Goetz and Aminoff (24) have systematically revieweda collection of letters exchanged between Mitchell and Brown-Séquard compiled from two sources: the Brown-SéquardArchives at the Royal College of Physicians in London and theTrent Collection of Duke University (Fig. 7). Letters writtenbetween the two during a 30-year period provide great insightinto their mutual dependence and respect, as well as their desireto assist each other in the advancement of their causes. The con-tact between the two men seems to have been mainly through let-ters, not personal meetings, given the fact that Mitchell spent hisentire career in Philadelphia, whereas Brown-Séquard was mov-ing around three continents in various academic centers. Thebond between the two was cemented by their mutual interest inthe burgeoning field of experimental neurophysiology, asopposed to classic clinical neurology. At the time, clinical neurol-

ogy was based on astute butempiric bedside observationswith postmortem correlationof pathological anatomy.Mitchell addressed the ques-tions related to peripheralnervous systems, specificallythe physiology of phantomlimb pain, causalgia, posttrau-matic neuropathy, and effectsof exposure to cold; Brown-Séquard, on the other hand,focused on the central nervoussystem with special emphasison the sensory pathways inthe spinal cord. Because thesetwo great men were editors ofprestigious neurology journalspublished from both sides ofthe Atlantic, they helped eachother with the publishing

process for their respective journals; Brown-Séquard, in addition,helped to translate Mitchell’s manuscripts into “purer French” sothey would be better received in France.

The following is an example of letters exemplifying the pro-motion of each other’s candidacy, through recommendations,when an academic position became vacant. For example, whena faculty position became vacant at Jefferson Medical College,Mitchell was interested in the job and requested that Brown-Séquard write a letter of reference on his behalf:

I am in the miseries of a canvass for Dr. Dunlison’s[sic] vacant chair, in connection with which I have afavor to ask of you which you must freely decline if itis not in accordance with your views. I would like youto address through me a letter to the Board of Trusteesof the Jefferson Medical College saying what you canin my favor as a physiologist. This I should have atonce. Again, begging you to decline without scruple ifit so suits you, I am faithfully yours” (24).

Brown-Séquard responded with the following recommenda-tion letter for Mitchell:

To the Board of Trustees of the Jefferson MedicalCollege: Gentlemen, I beg to certify that Dr. S. WeirMitchell justly stands very high among Physiologists,not only of this country but of Europe also. I willinglybear witness that in the old world, as well as here, heis well known as an enthusiastic lover of Science—asa most ingenious experimenter,—as a discoverer ofvery important facts, doctrines and laws in physiol-ogy and in Scientific and Practical Medicine,—and asa clean, forcible and learned writer. I sincerely believethat, even if the vacant chair were opened to the com-petition of European as well as American Physiolo-gists, few of the competitors could occupy that chair

958 | VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 www.neurosurgery-online.com

RENGACHARY ET AL.

FIGURE 7. Weir Mitchell was afamed American neurologist duringthe Civil War. He was an admirerand friend of Brown-Séquard; theyhelped each other in numerousways, and their mutual respectlasted throughout their lifetimes.

with so much benefit to the students and so muchcredit to themselves and to the College as WeirMitchell (24).

Brown-Séquard and Louis AgassizLouis Agassiz was a leading scientist in 19th century Amer-

ica and a professor of zoology at Harvard (Fig. 8). He was aSwiss physician but devoted his entire professional career topaleontology, geology, glaciology, and zoology. He was afounding member of the National Academy of Sciences and atireless promoter of science in America (2).

Brown-Séquard and Agassiz were good friends throughtheir acquaintance at Harvard; Brown-Séquard was also a per-sonal physician to Agassiz. There is evidence that Brown-Séquard repeatedly discouraged Agassiz from smokingbecause of its presumed detrimental effects on the nervoussystem. Agassiz maintained a personal laboratory at Nahant,MA, where he allowed Brown-Séquard to conduct experi-ments. It is thought that Brown-Séquard conducted experi-ments on the effects of testicular extracts at Nahant, but theresults were inconclusive. Brown-Séquard repeated theseexperiments at a later date, which led to the controversial useof injections of testicular extracts to overcome the physiologi-cal effects of aging, known as the “Elixir of Brown-Séquard.”

CONTRIBUTIONSTO NEUROSCIENCE

Experimental Work on the Sensory Pathways in the Spinal Cord

To put Brown-Séquard’scontributions in proper con-text, it is best to trace the his-tory of the knowledge ofspinal cord physiology fromthe remote past (3). Galenmade attempts to section thespinal cord in primates; withcomplete transection, therewas loss of motor strengthand sensibilities in the bodilypoints below the level of thecut. However, if only half ofthe spinal cord was severed,the weakness was confined tothe ipsilateral limb distal tothe cut; there was no mentionof sensory loss.

Through ablation experi-ments and anatomic sections,two contemporary neurosci-entists of Brown-Séquard, SirCharles Bell and Francois

Magendie, had established that the ventral root subservedmotor function, and the dorsal root, sensory function. Theypostulated that the anterolateral segment of the cord carriedmotor fibers, whereas the posterior columns subserved sen-sory fibers. However, they did not make a distinction amongmodalities of sensation and were not aware of distinct path-ways for each.

Brown-Séquard’s contribution to this knowledge evolvedthrough several years of research. His initial thesis work of 1846,performed when he was a medical student in the laboratory ofDr. Martin-Magnon, conclusively demonstrated that the poste-rior column did not transmit all of the sensations to the highercenters. His work also hinted at “the ease with which sensoryimpressions were transmitted from one side of the cord to theother” (Fig. 9) (31). He continued to refine his observations, andthe final definitive triad of the syndrome was published in the

FIGURE 8. Louis Agassiz, aHarvard professor, is consideredone of the founding fathers of themodern American scientific tradi-tion. A Swiss physician by earlytraining, he spent his entire careeras a paleontologist, geologist,glaciologist, and zoologist. He wasa founding member of the NationalAcademy of Sciences. He was aclose friend, faithful supporter, andeven a patient of Brown-Séquard.He allowed Brown-Séquard the useof his private laboratory at Nahant,MA to conduct testicular trans-plantation experiments.

FIGURE 9. Drawings from Brown-Séquard’s work showing levels of spinalcord hemisection. The drawing at top left shows decussation of sensorypathways at the level of the spinal cord, a revolutionary concept that he intro-duced to neuroscience and for the first time in history.

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 | 959

CHARLES-ÉDOUARD BROWN-SÉQUARD

late 1850s, after he had con-ducted additional experimentsin the basement of the Egyp-tian Building in Richmondand after observing the clini-cal syndrome in humans (Fig.10) (17, 20).

Of historic interest, Brown-Séquard made one additionalobservation to the classic triad,namely the presence of ipsilat-eral hyperesthesia on the sideof the hemisection; this phe-nomenon of hyperesthesia isnot generally observed inhuman cases. The discrepancymay be related to the follow-ing factors: 1) the difficulty inconducting precise, sophisti-cated sensory examination inan experimental animal thathas undergone a major lamin-

ectomy under no anesthesia; 2) an animal in this setting will besensitive to any stimulus except in the anesthetized areas; and 3)the method of sensory testing may not be refined to determinelack of position sense in an experimental animal.

Brown-Séquard does not seem to have been aware, on thebasis of a review of his publications, that there are two distinctpathways in the spinal cord for sensation: the spinothalamic tractfor pain and temperature, and the posterior column for joint andposition sense. Credit for this discovery should be given to MoritzSchiff, a student of Magendie and a contemporary of Brown-Séquard, who, after intensive studies in cats and dogs, demon-strated that there are distinct pathways for sensations in thespinal cord, the spinothalamic tract, and the posterior columnsubserving two separate modalities of sensation. Brown-Séquardwas aware of Schiff’s work; however, he delineates the triad offindings very clearly and unambiguously in humans; he does notdescribe the ipsilateral hyperesthesia that he observed in experi-mental animals: ”Facts proving that a lesion in one of the lateralhalves of the spinal cord produces: 1st, paralyzis of the volun-tary movements in the same side; 2nd, anesthesia to touch, tick-ling and painful impressions and changes of temperature in theopposite side; 3rd, paralyzis of the muscular sense on the sameside” (17).

“Spinal Epilepsy”Brown-Séquard noted that some of his experimental animals,

especially the guinea pigs that had undergone spinal cordhemisection, developed seizure-like activity, especially in thefacial and neck regions (33). He described this entity in numer-ous articles to the point that it became a well-recognized entityand was designated as “spinal epilepsy” or “Brown-Séquardseizures.” He gained a reputation as a specialist in epileptology,and his practice expanded rapidly as patients with seizure dis-orders sought his opinion. He was among the first to advocate

bromide therapy for epilepsy (40). Later, however, carefulanalysis indicated that the condition did not represent trueepilepsy. It was first attributed to hyperactive reflex activity,and later authors postulated that the effect was the result ofinfestation with lice with mechanical irritation of the skin orpossible release of neurotoxin. It is unfortunate that the term“spinal epilepsy” or “Brown-Séquard epilepsy” did not standthe test of time, but “Jacksonian seizures,” named after Brown-Séquard’s protégé, are established as a classic clinical entity.

Brown-Séquard further observed that the offspring of epilepticguinea pigs were also susceptible to have the same type ofepilepsy, implying for the first time in the history of genetics thatan acquired disorder can be inherited and transmitted to futuregenerations, a radically new concept at the time, but one that hasnot held true since. Charles Darwin, who was a contemporary ofBrown-Séquard (Fig. 11), showed a keen interest in his findings;they were published at the same time Darwin was preparing hisbook, On the Origin of Species.

Cerebral LocalizationCerebral localization was an extremely controversial subject in

the mid- to late 19th century because the basic neural mecha-nisms and pathways were just beginning to be understood.The French neurologist and professor of anatomic pathology,

960 | VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 www.neurosurgery-online.com

RENGACHARY ET AL.

FIGURE 11. The sign-in register of the May 20, 1858, meeting of thePhilosophical Club of the Royal Society. The signatures of Brown-Séquardand Charles Darwin are clearly identifiable.

FIGURE 10. The title page ofBrown-Séquard’s monograph, “Ex-perimental and Clinical Resear-ches in the Physiology andPathology of the Spinal Cord,”published in Richmond in 1855.

FIGURE 12. A, Thomas Addi-son, a physician at Guy’s Hospitalin London, provided the earliestdescription of a disease affectingthe suprarenal capsules thatresults in anemia, asthenia, loss ofmuscle tone, and a peculiar bronzediscoloration of the skin. Hisastute observations led to the rev-olutionary concepts of the role ofadrenal glands in humans. It pro-vided the impetus for Brown-Séquard to perform ablation exper-iments that proved the importanceof the adrenal glands for mammalian survival; it was a landmark discov-ery in the field of endocrinology. B, illustration showing a patient withbronze discoloration of the face from a monograph published by Addisonin “Of the Constitutional and Local Effects of Disease of SuprarenalCapsules.” C, autopsy specimen showing destruction of the suprarenalcapsules by tuberculous infection.

Charcot (1825–1893), and Brown-Séquard were exactly oppositein their views (34, 45). Charcot based his views on his large clin-ical experience at Salpetriere, long-term follow-up of hispatients, and the availability of meticulous postmortem studiesin those patients. In turn, Brown-Séquard was an experimental-ist and based his conclusions on objective laboratory studies.Charcot believed that there were many centers in the brain sub-serving specific function and that anatomic loss of these centersby focal lesions (discrete cerebral hemorrhages) resulted in lossof function of that region.

Brown-Séquard placed greater emphasis on the network the-ory, which implies a large network of neural interconnection,both excitatory and inhibitory; any brain function requires con-stant, simultaneous interaction between these dispersed neu-rons and, as such, there were no centers. The composite infor-mation at the time, including the works of Fritsch and Hitzigon motor cortical stimulation, Ferrier’s ablation experiment indogs, and Hughlings Jackson’s description of focal epilepsy,all supported Charcot’s viewpoint of brain centers. Subsequentelectrophysiological work has supported the network theory ofBrown-Séquard. Nevertheless, the direct confrontation of thesetwo neurological giants marks an important page in the historyof neurology. The following is an excerpt from a debate at theSociete de Biologie between the two:

Charcot: “Certainly there exists in the brain areaswhere a lesion inescapably leads to the same symp-toms. Outside of this law, everything else is confusion.”

Brown-Séquard: “I regret to be in complete dis-agreement with Dr. Charcot and cannot accept local-ization theory as presently formulated” (23).

Self-experimentationIn his zeal to conduct physiological experiments, Brown-

Séquard sometimes used himself as the subject, often at a detri-ment to his health and even risk to his life. A few examples fol-low. While teaching at the Medical School of Virginia, in theEgyptian Building, he attempted to elucidate important func-tions of the skin. He coated himself with varnish from head tofoot and was later found unconscious on the floor. Only thequick work of a student to remove the varnish with alcoholsaved Brown-Séquard’s life. In another example, during thecholera epidemic on Mauritius, Brown-Séquard personally vol-unteered to treat the victims. He had known from Magendie’swork that opium might be effective. To prove the efficiency ofthe drug, he attempted to catch cholera by swallowing thevomit of one of his patients and taking a large dose of lau-danum. He was found unconscious in the corner of his room,pointing his fingers toward a coffee pot; he was resuscitated. Inanother example, Brown-Séquard, again while in Richmond,was studying the phenomenon of gastric digestion. Taylor, onehis students, had this to say regarding the experiments:

Dr. Brown-Séquard, however, never hesitated to puthimself to the question if he thought thereby he couldobtain a more satisfactory answer than cats and dogs

A B

C

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 | 961

CHARLES-ÉDOUARD BROWN-SÉQUARD

could give. Accordingly, in studying the phenomenonof digestion, he let down into his stomach pieces ofsponge tied to the end of strings and therewith fishedup material for subjection to the processes of science.He did it so zealously that at length the constant titil-lation of the organ turned him into sort of a cow, hisfood as fast as he got it down insisted on coming backinto his mouth to be chewed over and over again. Adisorder of this kind, which would make any otherman hang himself, was no doubt to one of his inquir-ing spirit a source of unspeakable satisfaction, for it

dinner. All my friends know what an immense changethat implies for me….I can now without difficulty,and even without thinking about it, go up and downstairs almost running, a thing which I always didbefore the age of sixty. By using the dynamometer, Ihave established that there has been an incontestableincrease in the force of my limbs. For my forearm inparticular, I find that the average of trials since thefirst two injections is greater by 6 to 7 kilograms thanthe average before the injection (37).

This stunning observation created uproar in the scientificcommunity and the lay press. Brown-Séquard was beginning tolose respect among his colleagues; they argued that his conclu-sions had been hastily drawn, that the process had not beentried in a large series of patients, that there was no control

962 | VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 www.neurosurgery-online.com

RENGACHARY ET AL.

was of great rarity, so that he was in possession of anew and delightful field of research all to himself (43).

Research of Vasomotor NervesIn the early 1850s, Claude-Bernard initiated experiments study-

ing the effect of sectioning the cervical sympathetic nerves (35).He noticed increased temperature in the distribution of the sec-tioned nerve and concluded that there was higher metabolicactivity with greater generation of heat after sympathectomy.Brown-Séquard performed similar experiments in Philadelphiaand observed the same phenomenon but offered a differentexplanation; he thought that the increased heat was generatedthrough vasodilatation of blood vessels after sympathectomy.Impassioned arguments ensued between the two giants withrepeated exchanges in several published articles until Bernardeventually conceded and accepted Brown-Séquard’s explanation.

Brown-Séquard: Father of EndocrinologyThe earliest clue to the existence of hormones came from the

experiments conducted by Arnold Berthold (12), who was cura-tor of the zoo in Gottingen, Germany. In 1849, he surgicallycastrated roosters and noted several physical and biologicalphenomena; they lost their combs, wattles, and spurs; becamedocile; and also failed to fight, crow, or mate. When theseeffects were reversed by reimplantation of the testes, Bertholdconcluded, “the testes act upon the blood, and the blood actsupon the whole organism” (12).

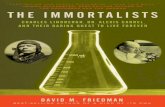

In 1855, Thomas Addison (Fig. 12A) (1), a physician at Guy’sHospital in London, published reports of a series of patientswho presented with rapidly progressive asthenia, motor weak-ness, bronze discoloration of the skin, and severe anemia.Carefully conducted autopsies revealed complete destructionof bilateral suprarenal capsules by tuberculous infection (Fig.12, B and C). On the basis of Addison’s research, it seemed thatadrenal glands are essential for normal physiological function-ing, but the mechanism was unclear (14).

Brown-Séquard was impressed with these observations. In1886, he reported adrenalectomy in dogs, guinea pigs, rabbits,and mice, which led to death within 24 hours; however, shamlaparotomies leaving the suprarenals intact did not. He alsomade a startling announcement in a paper presented at theSociete de Biologie in Paris (18, 19): He had rejuvenated himselfwith injections of testicular extracts prepared from young dogsand guinea pigs. He was 72 years old, and during the preced-ing decade had noticed easy fatigability, loss of strength andendurance, and insomnia. After the injections, he stated:

…I have regained at least all the force which I pos-sessed a number of years ago. Experimental work atthe laboratory tires me little now. I can, to the aston-ishment of my assistant, remain standing for hourstogether without feeling the need of sitting down.There are some days when after three and a quarterhours of work standing, I have been able, contrary tomy habits for twenty years, to work at the preparationof a memoir for more than an hour and a half after

FIGURE 13. A, a magazine advertisement showingextracts of animal organs, including testicular fluid; itwas known as “Brown-Séquard Elixir.” Because theagent was prepared by the same organization that man-ufactured vaccines with proven efficiency in combatinginfectious diseases, there was a degree of faith in the effi-ciency of all biological agents produced by the insti-tute. B, an advertisement for “Sequarine,” also knownas “Brown-Séquard Elixir.” Advertisements for theelixir made outrageous claims of its efficacy and thenumber of medical disorders it could cure. Such claimsin the lay press brought disrepute to the scientificintegrity of Brown-Séquard.

A

B

group, and that there had beenno laboratory validation. Un-scrupulous manufacturersmade extravagant claims inadvertisements in the lay press(15) with preparations called,

“Elixir of Life,” “Brown-Séquard Elixir,” and “Sequarine.” Theindications for the injections broadened to include “nervous-ness, neurasthemia, anemia, rheumatism, gout, sciatica, kidneydisease, diabetes, dropsy, dyspepsia, liver complaints, indiges-tion, paralyzis, locomotor ataxy, general weakness, influenza,pulmonary troubles, leprosy, and TB” (Fig. 13).

In 1889, Jim “Pud” Galvin (Fig. 14), a Pittsburgh baseballpitcher, was the first player in the history of baseball to try aperformance-enhancing substance. He is reported to have used“Brown-Séquard Elixir” to improve his pitching prowess in agame against Boston. Use of such performance-enhancing drugswas not illegal in the 19th century; an article from the WashingtonPost in 1889 states, “…if there still be doubting Thomases whoconcede no virtue to the elixir, they are respectfully referred toGalvin’s record in yesterday’s Boston–Pittsburgh game. It is thebest proof yet furnished of the values of the discovery” (41).

Brown-Séquard did not receive any monetary compensationfor his popular product. He prepared the extracts under strin-gent conditions with the help of his laboratory assistant,d’Arsonval, and distributed them free of cost to the requestingphysicians until the number of requests outstripped hisresources. Despite growing criticism, Brown-Séquard continuedto work undaunted, exploring other applications for his “elixir.”

Brown-Séquard was convinced that most glands that haveducts and external secretions also have internal secretions thatenter the bloodstream directly and affect distant organs. Hereis his prescient statement that foresaw the function of hor-mones, a term that had not been coined at this time:

I say now merely that all glands with an externalsecretion have at the same time, like the testicles, aninternal secretion. The kidneys, the salivary glands, thepancreas are not merely organs of elimination. Theyare like the thyroid, the spleen, etc., organs giving to theblood important principals, either in a direct manner orby resorption after their external secretion (37).

Brown-Séquard attempted to treat patients with Addison’sdisease by use of adrenal extracts but was unsuccessful. He triedtreatment of diabetes with pancreatic extracts but could not iso-late insulin because the pancreas was autodigested in its ownexternal secretion. Brown-Séquard was finally vindicated whenMurray, in 1891, successfully treated myxedema via subcuta-neously administered injections of thyroid extract with dramaticreversal of symptoms.

CONCLUSIONHistorians will agree that Brown-Séquard came to premature

conclusions regarding hormone replacement therapy beforethere was solid experimental validation (22, 42), but he cannotbe faulted for his prescient ideas that paved the way for thebirth of the modern science of endocrinology. He is the father ofmodern endocrinology and hormone replacement theory. Theinscription on the pedestal of the bust of Brown-Séquard in thePublic Garden in Port Louis, Mauritius, summarizes the great-ness of the man (Fig. 15):

Here truly was a Mauritian of whom his compatriotsmay well and justly be proud—a man whose characterselfishness and self-assumption were utter strangers, anoble life of high gifts and powers of intellect andresearch devoted absolutely and unsparingly to thewelfare of mankind in ages yet to come (26, 27, 36).

REFERENCES1. Addison T: On the Constitutional and Local Effects of Diseases of the Supra-Renal

Capsules. Birmingham, Classics of Medicine Library, 1980.2. Aminoff MJ: Brown-Séquard: A Visionary of Science. New York, Raven Press, 1993.3. Aminoff MJ: Historical perspective: Brown-Séquard and his work on the

spinal cord. Spine 21:133–140, 1996.4. Anonymous: M. Brown-Séquard’s discoveries. Boston Med Surg J 55:

252–254, 1856.5. Anonymous: Brown-Séquard’s teaching. Boston Med Surg J 130:370–371,

1894.6. Deleted in proof.7. Anonymous: Death of Professor Brown-Séquard. Lancet 1:906–907, 1894.8. Anonymous: Obituary of Brown-Séquard. Am J Insanity 50:593–595, 1894.9. Anonymous: Obituary: Professor Brown-Séquard. Lancet 1:975–977, 1894.

10. Anonymous: Heroes of medicine: Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard.Practitioner 66:550–554, 1901.

11. Bendiner E: Brown-Séquard: Scientific triumphs and fiascoes. Hosp Pract(Off Ed) 23:127–158, 1988.

12. Berthold AA: The transplantation of testes. Bull Hist Med 16:399–401, 1944.13. Blanton WB: The Egyptian Building and its place in medicine. Bull Med

Coll Virginia 37:1–16, 1940.14. Borell M: Brown-Séquard’s organotherapy and its appearance in America at

the end of the nineteenth century. Bull Hist Med 50:309–320, 1976.15. Borell M: Organotherapy, British physiology, and discovery of the internal

secretions. J Hist Biol 9:235–268, 1976.

FIGURE 15. Bust of Brown-Séquard at Port Louis, Mauritius.The inscription at its base reflectsthe lifetime achievements and thecharacter of this great 19th cen-tury neurophysiologist.

NEUROSURGERY VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 | 963

CHARLES-ÉDOUARD BROWN-SÉQUARD

FIGURE 14. “Pud” Galvin, aPittsburgh pitcher, was the firstbaseball player in North Americaknown to have used “Brown-Séquard Elixir,” to improve hispitching prowess in a game againstBoston in 1889. Such perform-ance-enhancing drugs were notcondemned in the 19th century.

964 | VOLUME 62 | NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2008 www.neurosurgery-online.com

RENGACHARY ET AL.

16. Brown-Séquard CE: Experiments and Clinical Researches on the Physiology andPathology of the Spinal Cord and Some Other Parts of the Nervous Centres.Richmond, Colin & Nowlan, 1855.

17. Brown-Séquard CE: Lectures on the physiology and pathology of the nervoussystem; and on the treatment of organic nervous affections. Lancet 1:1–3,1869.

18. Brown-Séquard CE: Note on the effects produced on man by subcutaneousinjections of a liquid obtained from the testicles of animals. Lancet 2:105–107,1889.

19. Brown-Séquard CE: On a new therapeutic method consisting in the use oforganic liquids extracted from glands and other organs. Br Med J 1:1145–1147, 1893.

20. Brown-Séquard CE: Course of Lectures on the Physiology and Pathology of theCentral Nervous System. Whitefish, Kessinger Publishing, 2004.

21. Cabell D: The life and work of Brown-Séquard. Education 20:431–436, 1900.22. Cussons AJ, Bhagat CI, Fletcher SJ, Walsh JP: Brown-Séquard revisited: A les-

son from history on the placebo effect of androgen treatment. Med J Aust177:678–679, 2002.

23. Goetz CG: Battle of the titans: Charcot and Brown-Séquard on cerebral local-ization. Neurology 54:1840–1847, 2000.

24. Goetz CG, Aminoff MJ: The Brown-Séquard and S. Weir Mitchell letters.Neurology 57:2100–2104, 2001.

25. Gooddy W: Some aspects of the life of Dr. C.E. Brown-Séquard. Proc R SocMed 57:189–192, 1964.

26. Gooddy W: Dr. Brown-Séquard in space and time. Proc Aust Assoc Neurol7:1–5, 1970.

27. Gooddy W: Charles Edward Brown-Séquard, in Rose FC, Bynum WF (eds):Historical Aspects of the Neurosciences. New York, Raven Press, 1982, pp371–378.

28. Grmek MD: Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard, in Gillispie CC (ed): Dictionaryof Scientific Biography. New York, Scribner, 1970, pp 524–526.

29. Deleted in proof.30. Herman JR, Schutte H: Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard (1817–1894). Invest

Urol 15:432, 1978.31. Jay V: A portrait in history: The extraordinary international career of Dr.

Brown-Séquard. Arch Pathol Lab Med 123:662, 1999.32. Jefferson M: Brown-Séquard: A biographical essay. Lancet 1:760–761, 1952.33. Koehler PJ: Brown-Séquard’s spinal epilepsy. Med Hist 38:189–203, 1994.34. Koehler PJ: Brown-Séquard and cerebral localization as illustrated by his

ideas on aphasia. J Hist Neurosci 5:26–33, 1996.35. Laporte Y: Brown-Séquard and the discovery of the vasoconstrictor nerves.

J Hist Neurosci 5:21–25, 1996.36. Laporte Y: Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard: An eventful life and a significant

contribution to the study of the nervous system. C R Biol 329:363–368, 2006.37. Olmsted JMD: Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard: A Nineteenth Century

Neurologist and Endocrinologist. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1946.38. Olmsted JMD: Edouard Brown-Séquard, in Haymaker W, Schiller F (eds): The

Founders of Neurology. Springfield, Charles C. Thomas, 1970, ed 2, pp 181–186.39. Ruch TC: Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard (1817–1894). Yale J Biol Med

18:227–238, 1946.40. Simonetti F, Viviani R, Ceroni M: Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard. Funct

Neurol 9:303–306, 1994.41. Smith R: A different kind of performance enhancer. www.npr.org/tem-

plates/story/story.php?storyId�5314753. Accessed 11/28/07.42. Tattersall RB: Charles-Edouard Brown-Séquard: Double-hyphenated neurol-

ogist and forgotten father of endocrinology. Diabet Med 11:728–731, 1994.43. Taylor WH: Old days at the old college. Old Dominion J Med Surg 17:57–

100, 1913.44. Tyler HR, Tyler KL: Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard: Professor of physiol-

ogy and pathology of the nervous system at Harvard Medical School.Neurology 34:1231–1236, 1984.

45. Walker AE: The development of the concept of cerebral localization in thenineteenth century. Bull Hist Med 31:99–121, 1957.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank Brandon Parker, B.A., for editorial assistance and for compilation of

references. We also thank the staff of the Vera Shiffman Medical Library atWayne State University for assistance finding references essential to the comple-tion of this work.

COMMENTS

This is a well-documented and nicely illustrated article that wasenjoyable to read, like an adventure tale. In Charles-Édouard Brown-

Séquard’s story, there were many of the strong ingredients to make lifegenial and to make reactive personalities creative, that is, deep roots setin ungrateful soils and hard obstacles to overcome. He started with adifficult childhood, fatherless but with a devoted mother and educatedin an environment of poverty, which necessitated hard work. As ascholar, he was hurt by a rude teacher in literature but reacted by decid-ing to be a medical doctor and scientist. He studied and worked in lab-oratories in a tireless and passionate fashion. He was excluded from sta-ble positions in France because he was considered a foreigner, althoughhis native language was French. He had the chance to meet and shareknowledge with outstanding, open-minded scientists on both sides ofthe Atlantic: Claude-Bernard, the pioneer of experimental medicine;Broca, who made significant advances on localization of functions in thehuman brain; and Weir-Mitchell, whose works contributed to betterknowledge on the mechanisms of pain from peripheral origin.

Brown-Séquard’s experiments on himself in the endocrinologicfields, although disputable from a scientific point of view and impru-dent for his own safety, were nevertheless courageous. The use of hisresearch by mercenary trade companies deserves deep critical reflec-tion. The perfection of the Sequarine serum in a form for everyday useplaces animal therapy far in advance of other branches of medical sci-ence! Currently, there are still too many immature and overly enthusi-astic therapeutic promises.

Marc SindouLyon, France

Over the years, I have read a number of interesting pieces on Brown-Séquard and knew he was always considered a bit of an eccentric.

How little I really understood this until it was revealed in this mar-velous article on Brown-Séquard. To read of a man who crossed theAtlantic Ocean more than 60 times, spending nearly 6 years at sea, wasjust a start! On the one hand, he was a truly brilliant neurophysiologistwith magnificent contributions to our literature, and on the other hand,he was a near lunatic who was overworked, socially deviant, and attimes off on scientific tangents (e.g., elixirs of life). Included in this arti-cle are some interesting tidbits, including what seems to be the firstdoping by a professional athlete looking to increase his prowess at thebaseball mound. Reading of his lectures as viewed by his students wasdaunting indeed; he was clearly an eclectic individual. His self-experi-mentation including painting himself with varnish and then collapsingnear death or swallowing the vomit of a cholera victim: true vignettesmost remarkable to read. From all this extreme eccentricity came somesuperb and original science. What I wonder is how his contemporariestolerated him so well. The classic example was his time at Harvard andhis six different efforts to resign his post, five of which he withdrew.Brown-Séquard was clearly held in high esteem, and the authors havenicely documented this through various correspondence. Then therewere his vivisection studies in Virginia and the poor custodian and hiswife who nearly went crazy from all the animal cries. It is insights suchas these that truly bring this eccentric genius to life. He was a genius butclearly eccentric, being moody, unpredictable, impulsive, inconsider-ate, and wavering: What a combination of behaviors! My complimentsto the authors for an enjoyable and readable historical vignette. Thisarticle should be added to the collection of anyone even remotely inter-ested in the history of the neurosciences.

James T. GoodrichBronx, New York