Carrying the Burden of Past Violences: A Comparative Analysis of Transnational Palestinian Youth...

Transcript of Carrying the Burden of Past Violences: A Comparative Analysis of Transnational Palestinian Youth...

This article was downloaded by: [Mount Royal University]On: 18 December 2013, At: 14:31Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Sikh Formations: Religion, Culture,TheoryPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsfo20

CARRYING THE BURDEN OF PASTVIOLENCESMark Muhannad Ayyasha

a Address: Department of Sociology & Anthropology, Mount RoyalUniversity, 4825 Mount Royal Gate SW, Calgary, Alberta, CanadaT3E 6K6.Published online: 18 Dec 2013.

To cite this article: Mark Muhannad Ayyash (2013) CARRYING THE BURDEN OF PAST VIOLENCES, SikhFormations: Religion, Culture, Theory, 9:3, 279-297, DOI: 10.1080/17448727.2013.861695

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17448727.2013.861695

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Mark Muhannad Ayyash

CARRYING THE BURDEN OF PAST

VIOLENCES

A comparative analysis of transnational

Palestinian youth movements

Through a comparative study of two Palestinian transnational youth movements, this articleseeks to understand how the transnational sphere traverses not just space but also time. Ianalyze how the Palestinian Youth Movement and the Gaza Youth Breaks Out move-ment understand themselves as carrying the burden of past violences in their promise to con-tinue the Palestinian struggle and lead it toward a just and peaceful solution. Particularly, Iam interested in how these movements interpret and conceive of the violences of 1948 andtheir continuation in present violences from different temporal, and not just spatial, stand-points. I examine the temporalities from which and to which transnational Palestinian move-ments speak, as well as how they orient themselves, through backward and forwardmovements, toward past–present–future. The article highlights how temporal differencesform tensions that are often overlooked by transnational scholars and activists.

This article explores the ways in which activists with diverse temporal standpointsoperate in the transnational sphere. Through a comparative analysis of two Palestiniantransnational youth movements, the article observes how the transnational sphere isconstituted by, as well as contains, the interaction between multiple temporal stand-points and examines how these temporal standpoints can create unforeseen tensionsand complexities within transnational struggles for peace and justice.

‘Transnational space’ has become the primary locus of interest to social scientistsworking in numerous areas of study, from transnational methodologies to transnationalsocial movements (e.g. see collection of articles in Guidry, Kennedy, and Zald 2000;Khagram and Levitt 2008). One of the more perplexing themes of transnationalsocial movements concerns the traversal of space across nationalized boundaries, aswell as the formation, limits, and possibilities of transnational public spheres wherestruggles for social justice, liberty, and equality can be waged (Guidry, Kennedy, andZald 2000, 5–13; also see Smith and Johnston 2002). In such studies, the transnationalessentially concerns the spatial crossing of borders or a traversal that occurs across space.But in so far as time is concerned, transnational studies seem to only investigatephenomena over or across time (Khagram and Levitt 2008, 2, 6–7). Succinctly put,recent trends in transnational studies have shed light on dynamics that would have

© 2013 Taylor & Francis

Sikh Formations, 2013Vol. 9, No. 3, 279–297, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17448727.2013.861695

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

been missed had the nation-state remained the focal point of analysis, but they remainsomewhat fixed within the conceptual framework of the nation-state as they likewisemaintain the centrality of some notion or other of space at the expense of time.1

The literature thus leaves the concept of time under-theorized in its analysis andlargely operates within the ‘history of the present’ model of time (Guidry, Kennedy,and Zald 2000, 29–31; Khagram and Levitt 2008, 6–7). This model of time claimsthat transnational phenomena are to be studied in relation to various histories thatshape the present (e.g. this model emphasizes the interaction between different versionsof the history of modernity in the study of global social movements). The history of thepresent model constructively opposes the a-historical analyses of phenomena that arecommon in the singular and all-encompassing linear/evolutionist model of time (e.g.the latter would emphasize a singular history of modernity in its explanation of allsocial movements – for an example, see Beck 1992). Despite its many strengths,however, the history of the present model does not call for an understanding of transna-tional phenomena through a traversal of time in the sense of challenging our conception oftime as eternal, steadily moving forward, and as constituting one very large streamwhose various compartmentalizations are neatly connected. The challenge of traversalthat this article espouses is accordingly directed against both the linear/evolutionistmodel of time and the history of the present model (even as it shares affinities withthe latter) and instead draws on a particular postcolonial conception of transnationaltime that Achille Mbembe advances.

Although there have been some productive exchanges between the field of transna-tional studies and the field of postcolonial theory (e.g. Dasgupta and Peeren 2007; Nilanand Feixa 2006), there remains a need for a conceptualization of transnational time thatcan allow for the traversal of time and such a conceptualization can be found inMbembe’s (2001) On the postcolony. In his attempt at a different writing of Africa andthe African subject, Mbembe suggests a move away from an evolutionist/linearmodel of time as well as models of rupture, and toward a view of every ‘age’ as ‘a com-bination of several temporalities’ (2001, 15). To understand how ‘one can envisage sub-jectivity itself as temporality’ (2001, 15) or how several temporalities are conferred by aset of material practices and signs, Mbembe posits a ‘time of entanglement’ for which heasserts three postulates:

First, this time of African existence is neither a linear time nor a simple sequence inwhich each moment effaces, annuls, and replaces those that preceded it, to the pointwhere a single age exists within society. This time is not a series but an interlocking ofpresents, pasts, and futures that retain their depths of other presents, pasts, andfutures, each age bearing, altering, and maintaining the previous ones. Second,this time is made up of disturbances… of more or less regular fluctuations andoscillations, not necessarily resulting in chaos and anarchy… . Finally… thistime is not irreversible. All sharp breaks, sudden and abrupt outbursts of volatility,it cannot be forced into any simplistic model and calls into question the hypothesis ofstability and rupture underpinning social theory.

(2001, 16; original emphases)

Mbembe explores the time of entanglement in a peculiar moment of the livedexperiences in Africa, of a context ‘in which the future horizon is apparently closed,

2 8 0 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

while the horizon of the past has apparently receded’ (2001, 17). In the mixture of bothof these absences in the present time, Mbembe captures the complex displacements,arbitrariness and eccentricities of an African time of experience or of both lived experi-ence in the world and the validations (or objectifications) of this lived experience informs of subjectivity (see 2001, 66–101). His notion of the temporal basicallyemerges from the need to understand a postcolonial condition that defies linear andrupture models because varied and sometimes contradictory political imaginaries andmaterial conditions of life (Mbembe 2006), as well as African state formations and struc-tures of governance (Mbembe 2001, 24–65) have intermingled to yield diverse andcomplex postcolonial states. The postcolonial condition thus contains multiple configur-ations of temporality that must be analyzed. As opposed to acting as a stable frameworkor horizon of analysis, temporality itself, for Mbembe, becomes the object of analysisand it can be examined in the three postulates quoted above.

Leaving aside the direction of Mbembe’s oeuvre for my purposes (i.e. the differentwriting of Africa he seeks to advance),2 I borrow from his work the three postulates oftime, which can be summarized as: interlocking,3 fluctuating and reversible.4 To high-light how these three postulates operate in transnational social movements, this articleasks the following questions that are more analytically focused and amenable to the topicof interest: when youth movements situate their positions relative to past violences (asany Palestinian movement must),5 then to what temporalities do such movements speak,and from which temporalities do they speak? And how do they orient themselves,through backward and forward movements, toward past–present–future? Specifically,I examine, through a hermeneutic-deconstructivist reading6 of their online publishedmaterials (press releases, brochures, and statements), how the transnational PalestinianYouth Movement (PYM) and the Gaza Youth Breaks Out movement (GYBO) (roughly, fromthe second half of the 2000s to the present) formulate and address the beginning andcontinuation of the Palestinian struggle for justice, freedom and liberty. I am interestedin how these movements interpret and conceive of the violences of 1948 (which is acritical turning point in the history of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict) from different tem-poral, and not just spatial, standpoints.7

This article challenges the view of past violence as a contained and sealed occurrencethat is frozen in the past, and instead interrogates how dynamic interactions betweenvaried temporal standpoints toward past violences form tensions in transnational acti-vism. The major significance of the analysis is to confront transnational movementswith the enormous difficulties that are involved in their efforts to break out of theviolent cycles in which they already operate. While most analysts and activists insight-fully highlight both the possibilities and the limits of transnational social movements’abilities to traverse space (e.g. through a focus on mobilization strategies, see Peteet2000), this is accomplished at the cost of analyzing the difficulties of traversing time.Thus despite their many successes, transnational youth movements tend to overlooktemporal differences, which raises the risk that they fall short of creating a transnationalsphere where dispersed populations and groupings can join together in a continuous andsustained struggle for peace and justice.

Before proceeding, I should note that there are two main reasons why transnationalyouth movements in general, and the two specific movements in particular, are of inter-est. The first reason concerns the explosion of transnational activism in, roughly, the last10 years. Recent uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Palestine, Israel, and Syria (among others)

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 8 1

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

have forced social scientists to reconsider the ‘transnational’ in processes of political,social, and cultural revolutions in the Middle East (e.g. Dabashi 2012; Gardner 2011;Gelvin 2012). The relentless and persistent flight of ideas, tactics, and strategies ofresistance across nationalized borders has underscored a transnational sphere wherestruggles are being initiated, advanced and in some cases carried out.

The second reason is that the very terms ‘youth movement’ already force scholarsand activists to tackle questions concerning time, both in the sense of movement per seand in the sense of generational shifts. While there are many Palestinian youth move-ments that are active today, my choice to focus on PYM and GYBO is guided by theneed to better understand self-proclaimed transnational movements (PYM) and move-ments (GYBO) that accentuate the transnational and generational shifts in ways thatchallenge the kind of transnationalism of a PYM, and these two movements offer themost striking examples. Moreover, I do not argue that PYM and GYBO are a majorforce in Palestinian politics today, nor do I intend to paint either of them as large move-ments that are widespread among the Palestinian people. These are relatively newmovements, small in their membership numbers, and any claims on their scope, influ-ence and future (or lack thereof) are, I think, somewhat premature at this stage.

PYM and GYBO: backgrounds and objectives

PYM’s platform calls for a unification of all Palestinians wherever they are geographi-cally located, regardless of their political affiliations and irrespective of their religiousbeliefs. This self-proclaimed transnational movement seeks to address the dispersionof Palestinian people across the world by creating a movement that can house them.The movement in its physical meetings and conferences in geographical locations likeSpain, France, and Jordan, and also in its digital location (http://pal-youth.org/), crea-tively seeks to fix the problem of displacement and dispersion both in its contemporaryform (e.g. feelings of detachment and distance that are found in the Palestinian youth ofthe diaspora), and in its original form back in 1948.

According to its own narrative, PYM was formed on 29 April 2011 during itssecond International General Assembly in Istanbul, Turkey. Previously, this group hadcalled itself the Palestinian Youth Network (PYN), which began to meet and coordinateevents, conferences, and demonstrations, and created a digital location in 2006. Theimpetus for the change from network to movement seems to have been the Arabrevolts and uprisings of 2011. In their ‘Statement on the 2011 Arab Revolts and Pro-spects for the Palestinian Youth Movement’, PYN states that the dispersion of Palesti-nian youth cannot allow them to take to the streets in the laudable manner of theTunisians and Egyptians and thus a different path of praxis must be undertaken.8 To over-come this obstacle, PYN believed that it was:

essential to continue to work toward the consolidation of a transnational movementof Palestinian youth under occupation and in exile in order to build a united liber-ation project, one that recognizes the voices and meets the needs of all Palestinians.9

Thus the shift from a network to a movement framework highlights the group’sintention to move from a networking role, where they sought to create connections

2 8 2 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

between Palestinian youth across the globe, into a more active, organized and structuredmovement that takes on the role of unifying the dispersed Palestinian youth under onebanner that carries out, alongside other movements, the struggle for liberation andreturn. In this shift, PYM sees itself as becoming a responsible, active, and fullyengaged member of the Palestinian struggle. This role is counterposed to the ‘faultynegotiations process that has undermined Palestinian rights and national aspirations’and is posited as the true manifestation of the Palestinian struggle.10

Despite these structural changes and certain amendments to the general organiz-ation of the movement, as far as I can tell, there remained a great deal of continuitybetween PYN and PYM. Most importantly, PYM follows the by-laws established byPYN in regard to who can join the movement. There are two categories a prospectivemember (individuals or groups) must meet to join: (1) must be of Palestinian originwhich is defined as ‘Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestineregardless of whether they voluntarily emigrated, were evicted from it or stayedthere’ as well as ‘anyone born after that date, of a Palestinian father or mother, grand-father or grandmother, great-grandfather or great-grandmother, whether inside Pales-tine or outside it’ and finally anyone ‘who is entitled to Palestinian citizenship’ and (2)must be of 35 years of age or younger.11

The objectives of the movement arise directly from these two categories. Theymainly revolve around the need to fix the problem of displacement and dispersionboth in its contemporary form (i.e. the detachment of the diaspora) and in its originalform back in 1948. The crux of the latter objective is crystallized in the movement’smotto ‘Until Return and Liberation’, which appears on almost all of their press releases,announcements, and projects. It is indeed the entire vision of the movement, as it drivesall of their other objectives, methodologies, statements and beliefs. It is an unequivocal,uncompromising arch-position: the complete liberation of Palestine and the return of allPalestinians. The liberation is to be complete in the sense that it would not only meanliberation from Zionism and Israeli occupation (direct and indirect), but also a liberationfrom within that, for example, includes the liberation of women and the establishmentof equal rights for all within Palestinian society.12 The return is for all Palestinians,whether living in exile or struggling within the confines of refugee camps in Gaza,the West Bank, Lebanon, and elsewhere.

In contrast to PYM’s self-proclaimed transnationalism, GYBO offers an example ofa movement that accentuates the transnational in a more concrete manner. The GYBOmovement released its cyber ‘Manifesto 1.0’ in December 2010. Eight activists – fivemen and three women – wrote the Manifesto, which reached a wide transnational audi-ence with a speed that was beyond their expectations.13 The pressures, frustrations,injustices, and forms of oppression that led to this Manifesto were long in the making(from the building of the Wall, to Operation Cast Lead that devastated Gaza anddestroyed countless lives in 2008–2009, to the violent feud between Hamas andFatah), but the last straw for these activists seems to have been Hamas’s crackdownand violent shutdown on 30 November 2010 of the Sharek Youth Forum in Gaza,which is a charitable, well-funded,14 organization that has operated in the Palestinianterritories since 1996.15 The popularity of Manifesto 1.0 was largely due to its firstfew lines: ‘Fuck Israel. Fuck Hamas. Fuck Fatah. Fuck UN. Fuck UNWRA. FuckUSA! We, the youth in Gaza, are so fed up with Israel, Hamas, the occupation, the vio-lations of human rights and the indifference of the international community!’16 Called

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 8 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

by some in cyberspace as the ‘Fuck Movement’, GYBO seized transnational attentionwith the use of visceral language and a message that does not often come throughfrom Gaza. But it would be a mistake to reduce the text to the word ‘Fuck’.17

The most intriguing element of the Manifesto, it seems to me, is that it shifts thediscussion away from the political sphere of the state. It is no longer interested in whichpolitical party is in power, in supporting an opposition political party, in seeking the aidof international/transnational political institutions, or in destroying the political state ofIsrael which has caused Palestinians so much suffering. GYBO is only interested in threebasic demands: ‘We want to be free. We want to be able to live a normal life. We wantpeace.’18 There is nothing in the Manifesto that attempts to reach these goals through apolitical process. In fact, there is nothing that is akin to a step-by-step plan that can leadto the achievement of these three basic objectives since GYBO members have experi-enced many such attempts and they watched them fail one after the other.

This is why the movement’s leader, Abu Yazan, wrote two years after the release ofthe Manifesto: ‘Was it a manifesto or was it a cry for help? Perhaps an accusation or evenperhaps a demand to theworld and to ourselves; a demand for change from the outside andfrom within.’19 This is not to say that the GYBO activists were anti-praxis. They wereindeed involved in the organization of the protests that took place in March 2011,which demanded (among other things) a reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas.However, these protests and GYBO’s cyber activism resulted mainly in empty promisesfrom the Palestinian leadership and it brought violence and persecution tomany activists inGaza and the West Bank. This includes the GYBO movement and Abu Yazan, who wasimprisoned and tortured on numerous occasions. As Abu Yazan explains, though, itwas not the torture and the arrests that drove him, along with other GYBO activists,out of Gaza to Western countries; rather, they were driven out because they could noteven glimpse how the Manifesto’s demands could ever be supported, much less planned.

That is not where the struggle of GYBO activists ends. Indeed, in their new ‘trans-national home’, activists like Abu Yazan promise a continuation of the resistance:

But still, my story – and the stories of all the other amazing youth of Gaza – is andalways will be a story of resistance, of resilience. Of always coming back to the landwe belong to… . We struggle every day against our obstacles and for our dreams,and you can see that in all the amazing creativity coming out of Gaza, in our art,poems, writing, videos and songs, you can hear it and meet us in the talks wegive all over the world. Yes, we wrote a manifesto, and maybe that was just thebright and loud outcry of the beginning of a journey, whose path is hard andtiring, thorny and also often very quiet and dark. But it is always there.20

The demands of GYBO activists are still operating on the most basic of levels in thisstatement and that makes them all the harder to achieve. Indeed, they are admittedlyimpossible to achieve, but worthy of a continuous struggle regardless of failures andsetbacks.

These concrete and basic demands are very different from the uncompromisingarch-position of PYM, which is a position that is understandably seen as necessary inthe face of dispersal and in the face of internal Palestinian political divisions that haveled to a weak, ineffective, democratically illegitimate and capitulating Palestinian leader-ship.21 Certainly, the spatial differences between the two groups can help explain this

2 8 4 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

difference but more interesting, I argue, is the manner in which their varying temporalstandpoints create this difference. Most striking is how the uncompromising vision ofPYM emerges out of a certain kind of perspective on the Nakba (or Catastrophe) of1948 and how the GYBO activists basically never really mention past violences assuch or even mention them at all, since they are from a temporal viewpoint surroundedby them.

The burden of past violences

Beginning in 2009, PYM has released annual statements on the anniversary of theNakba. The first two of 2009 and 2010 are almost identical. They begin with brief over-views of the violences of 1948 (the Zionist plan of expulsion, the number of villagesdestroyed and people displaced); they then establish a direct link from these past vio-lences to the present, their continuation found in contemporary practices of buildingan Apartheid Wall, the siege and blockade of Gaza, ethnic cleansing, and the Judaizationof Jerusalem; then, the complicities of the international community (both Westernpowers and Arab states) are highlighted, particularly as they engage in a successfuldivide-and-conquer strategy; this leads to a disillusionment with the Palestinian Auth-orities (PA)22 and a questioning of their abilities to carry out a true negotiationprocess for peace and justice; finally, this raises the need and call for a new kind of Pales-tinian grassroots politics that is made up and advanced by all Palestinians and driven bythe quest for peace and justice for all. The entire narrative is placed within a frameworkof true Palestinian activism, which is summed up at the end of the 2009 statement: ‘Inappropriating their history, Palestinians have opted for appropriating their future.’23

This appropriation of the past – of re-claiming and re-telling the violences of 1948 –is not merely concerned with setting the historical record straight; rather, it is con-cerned with creating a concrete link with the past. Put differently, it is about the rec-lamation of the past in a way that it comes to properly explain the past’s present momentand hence opens up the possibility of making and creating the future.24 In this appropria-tion of past, present (which is not stated above but is operative in the words ‘opted for’)and future, PYM asserts that it will carry the burden of past violences because theseviolences are indeed continuous in their effects, both directly (e.g. in the continueduse of violence against Palestinians) and indirectly (e.g. dislocation). A statementtitled ‘The Old Will Die and the Young Will Never Forget’ depicts this in thesegment that is addressed to ‘David Ben-Gurion and Zionists of the World’:25

We will never forget what our eyes may not have seen, and what our feet may nothave ever touched. We will never forget the smell of our lands on an early morning,or the sound of bulldozers, gunshots, and airplanes attempting to beat us into sub-mission. We will never forget the feeling of homelessness-statelessness, imprison-ment and the world seasonally negotiating ‘what to do with the Palestinians’ as ifwe were sheep being herded… . vivid in our consciousness, engrained in our mem-ories and in-scripted in our wounds is what Palestine looks, feels, smells, tastesand sounds like… . So as the old dies, we will bury them with our tears, our gra-ciousness and for some – our anger; but as for us… . we choose how, what, andwhen to remember and we choose to remember that Palestine is worth the fight!26

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 8 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

This statement, addressed to a dead man (Ben-Gurion) recounting for him thehistory that he and his followers have attempted to cover up and thwart, announcesthat the memory of Palestine will forever be as vivid as the Palestine that has been con-quered and erased and the Palestine that continues to face erasure and extinction today.

But Palestine, both what was erased and what is precariously left of it today, is notsomething that can be smelled, heard, seen, or touched as far as the majority of the trans-national members of PYM are concerned. It is this element that sets the stage for a state-ment of steadfastness and commitment to the Palestinian cause. PYM readily carries theburden of the struggle that arose as a result of 1948 violences. Their readiness for thisburden indeed reveals a linear view of time that posits time as something that movesin one direction and at one speed. This is how PYM can pick up this steadily movingstruggle in the present moment. Moreover, this linear view of time already containswithin it a model of rupture or more properly both models of time together form anassemblage. As Mbembe argues, much of social theory asserts that a linear view oftime always conceals ruptures, and while this can be the case, it is not necessarily thecase because the two can also work together. In PYM, the rupture of 1948 is preciselythe source of a linear view of time that connects this moment of rupture with the present,dispersed, conditions of Palestine and the Palestinians. Succinctly put, PYM’s conceptionof time posits a ruptured time that has steadily moved in a linear direction to the present.The role or task of the present is to confront the rupture and deal with its injustices forthe sake of building a better future.

In their statement above, however, a line of thought that challenges such a view oftime can already be discerned, even if never announced or intended.27 I argue that thetemporalities from which, and to which, PYM speaks cannot be so neatly made to fitor concoct with each other. This can be discerned in how the statement above showsthat the burden of past violences does not lie in the violences themselves, but rather inthe transportation of the past, not only into the present (since the present cannotsmell, hear, touch, or see Palestine), but also and even more vividly back toward thepast: to a world where the homes were yet to be destroyed, could still be returned to,where the struggle as it was could still be joined, and where refugee camps were yet tobecome new homes – to a world where Ben-Gurion could still hear and fear them. Inother words, in PYM’s attempt to pick up where the ‘original’ struggle of 1948 hadleft off, we do not just see the intended creation of a direct linkage between past andpresent, we more importantly see a vision of the past being transported backwardtoward the past so as to appropriate it. The burden of the past is not simply carried bya subject who has opted for free choice as PYM intends its statements to achieve (as ifa burden can be handed from one person to another); rather, PYM transports theburden (i.e. a Palestine that once was but is no longer) that is already on their back,that is already in-scripted in their wounds, backward toward the past, both bringing itto life and simultaneously freezing it within the sufferings and the demands of the dead.

The GYBO movement’s treatment of 1948 is entirely different and can further illu-minate this line of questioning. In fact, GYBO’s treatment of the Nakba is absentaltogether, and we cannot find in GYBO the kind of commemoration that is prevalentin PYM. The reason for this is simple: in a very palpable way, GYBO activists are sur-rounded by the violences of 1948 in the sense that they do not mark the path taken fromthese past violences as the primary distortion of the Palestinian struggle – how so? I canbegin to illustrate this point with a brief example. Part of a statement that was released

2 8 6 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

to announce the heinous killing of 12-year-old Hamid Abu Daqqa, who was shot in thehead by Israeli soldiers while playing soccer with his friends, reads: ‘The percentage ofchildren among the over half a million Palestinians killed by Israel since 1948 is 30%.’28

This statement, which is intended to provide a larger context for this particular fatalshooting incident, reveals much more than simply situating this text within the ordinarysyntax of reporting. It shows how 1948 is not exactly in the past or that the violences of1948 are of the past; rather, the violences of 1948 have never ended, have never enteredthe history books because their history is still being written. GYBO’s cyber activismdoes not need to commemorate past violence because the violences of 1948, theburden of past violences, are not past but are being lived and renewed on a regularbasis (albeit on different scales and through different techniques). This is not a smalldifference, for when we counterpose GYBO’s temporal stance toward 1948 to thatof PYM, we can see the extent to which these differences create tensions.

PYM’s third commemorative statement of 2011 follows the gist and narrative of theprevious statements, but it is different in that it adds the element of the Arab uprisings.29

This statement shows how PYM views the connections between past and present vio-lences through the prism of active struggle and illuminates how the burden of past vio-lences operates in this movement. Toward the end of this statement, PYM states:

The [negotiation] processes proved to be a failure with regards to its content andapproach. This went far and beyond till it reached the arousal of Arab revolutionsin the region earlier this year in Tunisia and Egypt, and this gave a sense of optimismto the Palestinian youth and motivation towards the realization of the importance ofbeing part of the decision-making process and not just accepting decisions as theyare being taken and implemented… . The youth movement in Palestine in the WestBank, Gaza, 48, and in exile, amongst its diversity, is the biggest proof of the capa-bilities of the youth to protect their dream to their homeland.30

(Emphasis added)

There are two points I want to highlight here. First, the notion of active struggle iscounterposed to the failures of the PA at the same time that it does not offend thestruggle of the Palestinian people throughout the decades since the 1940s. This is impor-tant because PYM does not claim to appear out of nowhere or more properly, PYM feelsthe need to establish its emergence as a continuation of an already ongoing and activestruggle. Active struggle therefore has a concrete history in Palestinian politics. Thishistory has always been threatened from without (primarily but not exclusively bythe Zionist/Israeli occupation) but is now also threatened from within (i.e. the PA).

Thus PYM locates itself as the genuine form of Palestinian resistance within the his-torical movement of the struggle and this is counterposed to the regression of thestruggle undertaken by the PA. But when PYM rescues the past from the clutches ofthe PA, they not only connect the past with the present, but more importantly, theyare interlocking a certain configuration of the linkage between past, present and futureto another such configuration. Mbembe’s notion of an interlocking does not refer toan intentional act or conscious decision to intermingle and mix; rather, it refers tothe dynamic interaction between multiple configurations of temporality, and this is pre-cisely what is taking place in this case.

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 8 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

Certainly, PYM posits its configuration as the true movement of the struggle and thePA’s as its distortion. Nonetheless, PYM’s campaign is launched on the premise that theyare creating a grassroots politics within a political arena that has already been establishedby the antecedent of the PA (the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the first prominenttransnational Palestinianmovement). The problem for PYM is that the PA has saturated itsown possibilities within this arena and reached its capitulating dead-end, not that it hasceased to offer a vision (even if distorted) of a Palestinian past–present–future. Theycannot claim the latter since the PA is the direct descendant of the very struggle inwhich they want to insert themselves. This means that the interlocking of time compli-cates PYM’s position in the present, since such interlocking does not have the desiredeffect of simply connecting with one past and toward one future, claiming for PYM thegenuine, true, or authentic position in the present. Even if PYM distances itself to acertain degree from this interlocking with the PA through an outright rejection of thelatter,31 the picture remains complex as a result of PYM’s implicit (even if unintended)interlocking with GYBO’s configuration of past–present–future.

The absence of 1948 commemoration in GYBO reveals a more particular andcontext-specific configuration of past–present–future. We are no longer faced with amodel of a present that sets for itself the task of rectifying a distortion for the sake of afixed past and one true future; rather, we find a concentration on a present that hasnever left its past. In GYBO, there need not be a rectification of a distortion in thesense of a deviation from the path of true struggle: the suffering of the past and of thepresent is in itself the distortion – the distortion to basic human life. This is what Imean by the claim that GYBO is surrounded by past violences. From the temporal stand-point, then, this is completely different from the absolutist claims and objectives of PYM.

Laying claim to the genuine or true struggle against the different configurations ofGYBO is much more difficult and would not at all be convincing in the way that such aclaim might work against the PA. PYM simply cannot claim the mantle of grassroots poli-tics against the grassroots politics of GYBO. In other words, since PYM endeavors to houseall Palestinianmovements for peace and justice, PYM’s configuration cannot avoid an inter-locking with a configuration that opposes its absolutist claims/objectives and which pre-sents serious challenges to its position as the manifestation of genuine/true struggle.

The second, related, point I want to highlight is found in the italicized segment of thequote above, particularly the awkward sounding (even though commonly used) ‘48’ thatis inserted between locations (West Bank and Gaza) and dislocation (exile). The gist of thesentence is that 1948 Palestine is indeed a location that, as far as the struggle for liberationand return is concerned, is not different from locations such as the West Bank and Gaza.Indeed, earlier in the statement, the names of various villages that were destroyed in 1948were recounted and the objective of returning to these villages was reaffirmed. However,despite their efforts to paint the uncompromising vision as a continuation of a strugglebegun in the 1940s, ‘48’ stands out, starkly, as a non-location: a non-location that putsinto motion dislocation, a number that makes the reading of this sentence somewhatawkward, since ‘48’ is not a place that can be returned to, but more properly, a timethat is to be returned. PYM must speak to a temporality that moves backward towarditself if it is be understood as a location, since ‘48’ has only moved (can only move)into dislocation when it moved forward to the present.32

This reversibility of time illuminates the limits that Mbembe suggests of linear, rup-tured, models of time. Following Mbembe, reversibility does not mean that such

2 8 8 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

political imaginaries contain a possibility to travel back in time in the sense of recreating;in this case, Palestine precisely as it once was before 1948. Instead, it refers to themanner in which the youth movement’s orientation toward the past–present–futurecan produce unforeseen tensions within the movement’s arch-position. In their effortsto re-appropriate the past, PYM fails to consider that the past is not simply a place inwhich certain violent and terrible things happened; rather the past is something thatwe, in the present, continuously appropriate and reappropriate, create and recreate,and erase and re-erase, among a whole other range of dispositions/actions, and justas importantly, the past is a time that we must orient ourselves toward by, for instance,approaching it backward, forward, or by turning our back to it. Thus, when they talkabout ‘48’ as a place, as a physical location, they are doing more than highlight for theenemy the vividness of what was lost in their consciousness. They are also reversing timein the present. For instance, they address the arch-leader of the enemy, this dead mancomes alive in their discourse and is made to hear the cries of those he lead hisarmies to kill and expel. In this reversibility of time, the very movement of the strugglereaches backward, and in this backward movement, not only is the linearity of time unin-tentionally challenged, but also PYM’s position as the carriers of a past burden is chal-lenged. PYM is not carrying the burden in the simple sense of it being handed down tothem, they are throwing the burden back toward its past. They are attempting to rectifythe burden in the past itself, where Ben-Gurion, not current Prime Minister BenjaminNetanyahu, would face justice for his murderous deeds. In contrast, we find in the GYBOmovement a direct focus on Operation Cast Lead, Hamas’s crackdown of the SharekYouth Forum, the killing of Hamid Abu Daqqa and so on. There is no effort in thiscase to rectify the burden in the past itself since, once again, the burden of the pasthas never ceased and has never frozen the past in the past.

This different temporal stance helps illuminate, then, that PYM comes to speak tothe temporality of the present (e.g. siege of Gaza) and also to the temporality of the past(e.g. Ben-Gurion), not as two temporalities that are seamlessly connected, where effec-tively dealing with one means effectively dealing with the other, but as two temporalitiesthat contain two distinct movements. PYM speaks to the temporality of the past bymoving backward and the temporality of the present by moving forward (exemplifiedby ‘Until Return and Liberation’). These two movements are not so readily congruentwith one another and attention to the tensions formed between them shows the scopeand range of difficulties that PYM’s uncompromising vision faces. For instance, what isthe source of the arch-position? Is it in the past itself? Or is a backward movement creat-ing an arch-position in the past, for the past’s sake? How does this movement interactwith the forward movement of transnationality or of equality for all citizens of Palestine?Is a forward movement capable of bringing justice to the crimes of the past and/or to thepast’s present conditions and effects? Is transnationalism, for instance, equally able tobring justice to a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, a Palestinian refugee in Gaza, an afflu-ent Palestinian in Ramallah, a Palestinian laborer in Nablus, and a Palestinian-Israelicitizen in Haifa?33 Do all of these Palestinians want complete liberation and thereturn of all? Would certain segments simply prefer that basic demands for food, secur-ity, and employment be met, first and foremost?

These tensions also complicate the temporality from which PYM speaks. The fluctu-ations of time, of the constant disturbances of the Palestinian dispersion, do not lead tothe chaos and anarchy that analysts often expect of fluctuations. Rather, as Mbembe has

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 8 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

shown, such fluctuations signal dynamic processeswheremovement itself can alter the con-figurations of temporality that any given social movement engages with. This can beobserved in PYM’s two membership categories. The first category is an attempt to dealwith the spatial dispersion of Palestinians. It aims to unite Palestinians under one bannerwithout the practices of spatial exclusion practiced under the PA (which does not representthe interests of refugees and Palestinians in exile and this, in my view, is PYM’s most con-vincing challenge to the PA and in a lesser degree to GYBO). The second category dealingwith age seems simplewhere thosewho are 35 years of age or younger constitute the youth.It is not clear why 35, but suffice it to say, any attempt to delimit an age group will alwayshave an element of arbitrariness. This arbitrariness, however, reveals once again, the taken-for-granted disposition of PYM toward time and in turn complicates both categories.

PYM’s nuanced view of differing spatial standpoints is manifested in their first cat-egory. Like all categories of membership, this category practices exclusion, but PYMsmartly and progressively directs such practices toward ideology and not toward thespatial locations of Palestinians. That is, if a prospective member wants to join inorder to fundamentally change PYM, so that it comes to resemble the PA forexample, then that individual or group will not be permitted membership. So long asa prospective member is not a threat to the fundamental values and vision of PYM,then they are free to join it (even if they politically affiliate with Fatah, Hamas, etc.).In this way, the spatial standpoints with all of their different needs and demands canbe accommodated, in the sense of being given a chance to voice and share their ownunique concerns and problems, within a transnational space that can house them.Thus, the solid and rigid boundary of the space in which the debate between spatialstandpoints unfolds is not marked by space itself, but rather by the idea that spacecannot ever become the boundary itself. This is precisely what makes PYM’s boundarymore stable than the boundaries of space such as nationalized boundaries, which can beeasily shaken by officially unrecognized claims of belonging (this is especially the case forPalestine and the Palestinians). In other words, PYM engages in a creative exercise thatrefuses to allow the nationalized notion of space to become naturalized and presented asif it is an absolute. Instead, transnational space becomes the very arena in which variousspatial standpoints can converge, dissociate, debate, and assemble. In this context, spacenever becomes the absolute boundary of itself. Thus, GYBO activists, among manyothers, can join PYM’s transnational space without much issue.

But in the second category, time itself is its own solid and rigid boundary. The delimi-tation is carried out by the member’s age, or time becomes its own guardian so that when-ever a certain threshold in time is reached, membership becomes forbidden. Thiscompletely misses the temporal standpoints that are operative in PYM despite the move-ment’s efforts to operate as if it exists in one stream of time. The temporal standpoints fromwhich PYM speaks are left hidden by an overarching category of time – ‘35 years’ – that istaken as somehow natural. But this of course cannot serve as a solid or rigid boundary, sinceit is no more natural or absolute than the shifting temporal standpoints that it tries to coverup. For instance, are the disturbances of the PA to the genuine or true movement of thestruggle simply a result of their spatial distance from the refugees and the Palestinians inexile? Or, are such disturbances also emerging as a result of conflicting temporalitieswhere ‘youth’ temporalities are concerned with the injustices of the past and the failuresof the present and PA temporalities (or ‘older’ temporalities) are concerned with the fail-ures of the past and the necessity to alleviate suffering in the present?

2 9 0 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

I am not raising this question in order to settle it one way or the other – indeed, onecan find both of these formulations somewhat operative in discourses of both the ‘youth’and the ‘PA’. Though it should be noted that the PA only claims to alleviate suffering,but has never implemented real policies to properly achieve this (e.g. see Khalidi 1997;Said 2001), as both PYM and GYBO activists firmly and strongly argue. There remains adifference between the two in that the GYBO movement offers an example of a youthmovement that brings together both of these formulations in a way that accentuates thetransnational reach of the injustices, failures, and the persistence of suffering, as opposedto dividing injustices, failures, and sufferings along a neat temporal continuum. In thisaccentuation, the GYBO movement exposes the point that I want to highlight, which isthat time cannot serve as its own delimitation since such delimitation would altogetherhide from view temporal questions and tensions. Thus GYBO activists, even if under theage of 35, would introduce temporal standpoints into PYM’s transnational space thatcould not be easily or readily accommodated, debated and addressed.

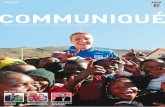

We shall return: a Palestinian child dons his father’s combat boots to continue the struggle (December 1978)

(Source: The author wishes to express his gratitude to Verso for granting non-exclusive rights to reproduce the

image of Naji al-Ali’s cartoon, which was originally published in December 1978 in the newspaper al-Seyassah

(Kuwait) and then reproduced in Verso’s A Child in Palestine: The Cartoons of Naji al-Ali (2009), with an introduc-

tion by Joe Sacco).

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 9 1

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

Concluding remarks

If we took literally, as PYM does, that the ‘The Old Will Die and the Young Will NeverForget’, we miss the complexity of how struggles move. This complexity is brilliantlycaptured above in Al-Ali’s ( [1978]2009) cartoon, specifically in the faces of the threefigures and the absence of a face for the witness, none of which portray a heroicpassing down of the revolutionary torch, and instead highlight the agony, fear, guiltand in certain senses the incomprehensibility of the passage of the burden of strugglefrom one generation to the next.

We would miss questions concerned with the transformations of struggles in theirvery movement. For example, in what kind of movement did the PA come into thePalestinian political arena? How did a transnational, democratically structured (rela-tively speaking), uncompromising movement like the PLO, against all odds, comeabout and how did it end up as the PA? Not just where, but when does the answerlie? In what temporalities did they operate and what can this tell us about PYM’s andGYBO’s movements? The debate over spatial standpoints does not stand alone sinceit is intertwined with a variety of temporal standpoints that, if left unaddressed, willcontinue to frustrate debates that are characterized as if they are solely spatial in essence.

One line of thought suggests that scholars ought to analyze spatiotemporal stand-points when studying transnational social movements. But that is not what I am referringto in this article. In highlighting the temporal dimension, I hope to have shown how tem-poral standpoints do not seamlessly connect with certain spatial standpoints. That is, it isnot necessarily the case that PYM, which seeks to build a transnational standpoint bytraversing space, speaks from one temporal standpoint that allows us to discuss a spatio-temporal standpoint of PYM. Rather, there are multiple temporal standpoints fromwhich, and to which, PYM speaks, just as there are for GYBO as well. I have notaddressed the latter in this paper, but the most important question haunting GYBO, Ithink, concerns the ways in which GYBO’s ‘fuck organized politics’ motto limits themovement’s ability to speak to the temporalities of the dispersed Palestinians in exile.I have directed most of the critical analysis toward PYM, not because I think thatthey fail in their positions and objectives (or conversely, because I think GYBO succeedsin theirs), but because PYM, in its preoccupation with the traversal of space, exemplifieswhat is accepted today as the model for transnational social movements. It is preciselythis model that I seek to disrupt through an analysis of the temporal dimension. Variedtemporal standpoints reveal questions and tensions that must be dissected and analyzed.Scholarly analysis can reveal how these temporal standpoints interlock, fluctuate andreverse among each other and with spatial standpoints. In this complex entanglement,we can perhaps open up new questions and exchange ideas and platforms that may leadto a different understanding of transnational politics and move toward different forms ofbelonging and paths of struggle in the traversal of space and time.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the Constellations, Confrontations andAspirations SSHRC-funded workshop at York University. I wish to thank the workshop’s

2 9 2 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

participants for their insightful comments and critical questions. I also want to thank theanonymous reviewers at Sikh Formations for their helpful suggestions, questions, andcomments.

Notes

1 Similarly, see the concept of ‘transnational social fields’ in Levitt and Schiller (2004),which focuses on the re-conceptualization of society in a transnational social field per-spective, where the nation-state no longer acts as the container of the social. Thisapproach is very useful and important, but it remains fixated on the question of trans-national space.

2 There is a limit to comparing the Palestinian struggle to postcolonial struggles and paststruggles for decolonization. The creation of the Israeli state contains many features ofcolonial and settler colonial practices, attitudes, institutions, and systems of oppres-sion. But like others, I believe that there are certain peculiar features of the Israeli–Palestinian case that illustrate the limits to such comparisons – for example, theunique historical forces (such as European anti-Semitism) that gave rise to the EuropeanJewish colonization of the land make this struggle for decolonization a peculiar one;also, Palestinian dispersion combined with the occupied status of the Palestinian‘state’ makes the condition of most Palestinian peoples distinctly not postcolonial. Icannot delve into the subtleties of the topic here (see Massad [2000] 2006 for an insight-ful discussion and analysis of some of these issues). Suffice it to say, the stating of thelimit to comparison has a long-standing presence in Palestinian history, politics, andculture. This limit is also observable within the two movements in question.

3 There are some similarities between Mbembe’s notion of interlocking and the inter-locking approach of certain gender, class, and race studies (e.g. see Razack 1998; Ken2007), particularly in the former’s contrast between a series and an interlocking andthe latter’s contrast between intersecting and interlocking. Since I am interested in thenotion of interlocking temporalities, I follow Mbembe’s notion in this paper.

4 The works of other postcolonial theorists such as Edward Said suggest that there areother postulates of time analysts ought to observe. Two of which are worth mention-ing here: (a) indistinguishable by virtue of a transnational temporality whereby past,present, and future can no longer be neatly compartmentalized and (b) interminableby virtue of all the closed doors that face and challenge the dispersed and exiled popu-lations and groupings of transnational youth movements. I cannot delve into this denseand large project here, but it is important to note that the three postulates above arenot conclusive even if sufficiently insightful for the present analysis.

5 In contrast to Mbembe’s assessment of the African postcolonial condition, the horizonof the past has certainly not receded in the Palestinian case.

6 In a nutshell, this kind of reading strives to (a) understand the worldview of socialactors from their own point of view, while (b) simultaneously putting into play thatwhich such a worldview contains within itself yet suppresses.

7 The focus on publicized materials is not meant to downplay the importance of whatmay be called the praxis activities of these movements (e.g. protests, creating pressureon political actors). A study of such practices could be carried out through Levitt andSchiller’s (2004) concept of ‘transnational social fields’ and would be most fruitful.However, to highlight the varied temporal standpoints, I must restrict this exploratory

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 9 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

analysis to conceptions of time at this stage. This is not to say that temporal stand-points are only operative in publicized materials, which are furthermore necessarilyconnected to the more praxis activities, but that they are best gleaned from publicizedmaterials at this stage.

8 In making this point, PYN shows part of the aforementioned limits of comparing thePalestinian struggle to other postcolonial struggles.

9 Cited from ‘Statement on the 2011 Arab Revolts and Prospects for the PalestinianYouth Movement’ (March 2011) (accessed April 25, 2012): http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=14.

10 Cited from ‘Palestinian Youth Movement 2nd International General Assembly FinalStatement’ (May 2011) (accessed April 25, 2012): http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=16.

11 Cited from the Booklet ‘The Inception of the Palestinian Youth Network’ (November2008: 19) (accessed April 25, 2012): http://pal-youth.org/booklet.

12 See ‘On International Women’s Day’ (March 2012) (accessed home page April 25,2012): http://pal-youth.org/.

13 See the following report by Ana Carbajosa in The Observer (January 2, 2011): http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jan/02/free-gaza-youth-manifesto-palestinian(accessed April 9, 2013).

14 For a list of its donors, see http://www.sharek.ps/about-donors (accessed April 9,2013).

15 See the timeline of events leading up to the shutdown of Sharek in Gaza: http://www.sharek.ps/gaza-chronology (accessed April 9, 2013).

16 Cited from ‘Manifesto 1.0’: http://gazaybo.wordpress.com/manifesto-0-1/(accessed April 9, 2013).

17 In ‘Manifesto 2.0’, GYBO expressed frustration at the large number of commentatorswho fixated on the first few lines of Manifesto 1.0 and ignored the rest of the text.They also stated the reasons behind their decision for anonymity in Manifesto 1.0 –reasons that became all too real soon after the Hamas Authorities discovered theiridentities and proceeded to imprison and torture these activists; see ‘Manifesto2.0’: http://gazaybo.wordpress.com/about/ (accessed April 9, 2013).

18 Cited from ‘Manifesto 1.0’: http://gazaybo.wordpress.com/manifesto-0-1/ (accessedApril 9, 2013).

19 Cited from ‘GYBO – 2 years after’: http://gazaybo.wordpress.com/gybo-2-years-after/ (accessed April 9, 2013).

20 Cited from ‘GYBO – 2 years after’: http://gazaybo.wordpress.com/gybo-2-years-after/ (accessed April 9, 2013).

21 This is a recurring theme in many of the movement’s statements. For an example, see‘Statement on the September 2011 Declaration of Statehood’ (September 2011)(accessed April 25, 2012): http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=18,and similarly, see the featured article on their home page ‘The Road to Liberation’(November 30, 2012) (accessed April 22, 2013): http://pal-youth.org/.

22 For the sake of brevity I will use the acronym PA. There are many problems withthis acronym, not the least of which involves international and local efforts (mostnotably, by the USA and Israel) to legitimize certain kinds of Palestinian politicsand delegitimize others in order to advance certain strategic interests. So I willuse the acronym loosely and have it refer to the Palestinian leadership ingeneral and all of its political factions, which is what PYM is referring to when

2 9 4 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

they criticize the negotiation processes and the official representatives of Palesti-nians whether they are the ‘recognized’ or ‘unrecognized’ authorities in theWest Bank and Gaza.

23 Cited from ‘The Nakba: 61 Years of Stolen History… 61 Years of Ethnic Cleansing… 61 Years of Genocide… 61 Years of Resistance’ (May 2009) (accessed April 25,2012): http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=5. Also see, ‘62 Years ofthe Palestinian Nakba’ (May 2010) (accessed April 25, 2012): http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=12.

24 It would be interesting to analyze, as does Comaroff (2005) in the context of SouthAfrica, the different dynamics between ‘learned’ and ‘lived’ history (roughly,inside and outside the classroom, respectively) of Palestine in these youth movements.One important difference in the Palestinian case is that there is not the kind of‘freedom from the burden of the past’ that forms (albeit paradoxically) part of theexperience in post-apartheid South Africa (Comaroff 2005, 127). This constitutesone of the important limits of postcolonial approaches to the study of the Israeli–Pales-tinian conflict and is one of the reasons why I focus on PYM’s stance toward past–present–future as opposed to analysing their position within the framework of ‘post-colonial identities’ or ‘decolonization struggles’.

25 David Ben-Gurion was the most influential and important Zionist leader in the 1930sand 1940s, and arguably in the entire history of Zionism/Israel. He was the first Israeliprime minister.

26 Cited from ‘The Palestinian Youth Network 2nd Year Anniversary: The Old Will Dieand the Young Will Never Forget’ (November 2010) (accessed April 25, 2012):http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=15.

27 Following Jacques Derrida, I argue that we cannot speak of intentions in writing in thefirst place. For a critique of instrumental conceptualizations of writing, see Derrida[1972] 1988, Derrida [1967] 1997.

28 Cited from ‘#Breaking: Cristiano Ronaldo, Real Madrid best player got killed in ashooting incident’: http://gazaybo.wordpress.com/2012/11/10/breaking-cristiano-ronaldo-real-madrid-best-player-got-killed-in-a-shooting-incident/(accessed April 9, 2013).

29 The 2012 statement does not contain the element of the Arab uprisings, as perhaps theoptimism that those movements inspired had waned somewhat at this stage. See‘Nakba Statement’ (May 2012) (accessed April 22, 2013): http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=19. I would not go so far as to say that such optimismor belief in the Arab uprisings had disappeared, as evident in the recent event thatPYM organized in Tunisia on 27–30 December 2012, which was titled ‘Arab YouthConference for Liberation and Dignity’: http://pal-youth.org/eventsdetail.php?id=46 (accessed April 22, 2013).

30 Cited from ‘63 Years of the Palestinian Nakba’ (May 2011) (accessed April 25, 2012):http://pal-youth.org/press_releasesdetail.php?id=17.

31 I doubt that such a rejection of the PA as a distortion can work sufficiently to distancePYM from interlocking with the PA. The picture is complex and cannot be given fullattention in this article since there are multiple configurations of past–present–futurewithin the PA itself – for instance, the ‘religious’ configurations of Hamas, the‘secular’ configurations of Fatah, the Marxist-dialectical configurations of thePopular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and so on.

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 9 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

32 I do not refer here to conventional understandings of ‘backward movements’ and all ofthe negative connotations that come along with them. Such negative connotationsoften arise from a conception of time as linear and progressive, where the presentis viewed as more desirable and superior to the past.

33 For studies that seek to capture the different demands of various Palestinian and Jewishgroups (though not necessarily from a temporal standpoint), see Lesch and Lustick(2005).

References

Al-Ali, Naji. 2009. A Child in Palestine: The Cartoons of Naji al-Ali. Introduction by Joe Sacco.London: Verso.

Beck,Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a NewModernity. Translated byM. Ritter. London: Sage.Comaroff, Jean. 2005. “The End of History, Again? Pursuing the Past in the Postcolony.” In

Postcolonial Studies and Beyond, edited by A. Loomba, S. Kaul, M. Bunzl, A. Burton,and J. Esty, 125–144. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Dabashi, Hamid. 2012. The Arab Spring: The End of Post-colonialism. London: Zed Books.Dasgupta, Sudeep, and Esther Peeren, eds. 2007. Constellations of the Transnational: Modernity,

Culture, Critique. Amsterdam: Rodopi.Derrida, Jacques. [1972] 1988. “Signature Event Context.” Translated by S. Weber and

J. Mehlman. In Limited Inc, edited by G. Graff, 1–23. Evanston, IL: NorthwesternUniversity Press.

Derrida, Jacques. [1967] 1997. Of Grammatology. Corrected edition. Translated byG. C. Spivak. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gardner, Lloyd C. 2011. The Road to Tahrir Square: Egypt and the United States from the Rise ofNasser to the Fall of Mubarak. New York: The New Press.

Gelvin, James L. 2012. The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York: OxfordUniversity Press.

Guidry, John A., Michael D. Kennedy, and Mayer N. Zald. 2000. “Globalizations and SocialMovements.” In Globalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the TransnationalPublic Sphere, edited by J. A. Guidry, M. D. Kennedy, and M. N. Zald, 1–32. AnnArbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Ken, Ivy. 2007. “Race-Class-Gender Theory: An Image(ry) Problem.” Gender Issues 24 (2):1–20.

Khagram, Sanjeev, and Peggy Levitt. 2008. “Constructing Transnational Studies.” In TheTransnational Studies Reader: Intersections & Innovations, edited by S. Khagram andP. Levitt, 1–18. New York: Routledge.

Khalidi, Rashid. 1997. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness.New York: Columbia University Press.

Lesch, Ann M., and Ian S. Lustick, eds. 2005. Exile and Return: Predicaments of Palestinians andJews. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transna-tional Social Field Perspective on Society.” International Migration Review 38 (3):1002–1039.

Massad, Joseph A. [2000] 2006. “The ‘Post-colonial’ Colony: Time, Space, and Bodies inPalestine/Israel.” In The Persistence of the Palestinian Question: Essays on Zionism and thePalestinians, 13–40. London: Routledge.

2 9 6 S I KH FORMAT I ONS

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

Mbembe, Achille. 2001. On the Postcolony. Translated by A. M. Berrett, J. Roitman, M. Last,and S. Rendall. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mbembe, Achille. 2006. “On Politics as a Form of Expenditure.” Translated byM. Anderson. In Law and Disorder in the Postcolony, edited by J. Comaroff andJ. L. Comaroff, 299–335. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Nilan, Pam, and Carles Feixa, eds. 2006. Global Youth? Hybrid Identities, Plural Worlds.London: Routledge.

Peteet, Julie. 2000. “Refugees, Resistance, and Identity.” In Globalizations and Social Move-ments: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere, edited by J. A. Guidry, M. D.Kennedy, and M. N. Zald, 183–209. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of MichiganPress.

Razack, Sherene. 1998. Looking White People in the Eye: Gender, Race, and Culture in Courtroomsand Classrooms. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Said, Edward. 2001. The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After. New York: Vintage Books.Smith, Jackie, and Hank Johnston, eds. 2002. Globalization and Resistance: Transnational

Dimensions of Social Movements. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Mark Muhannad Ayyash. Address:Department of Sociology & Anthropology, Mount RoyalUniversity, 4825 Mount Royal Gate SW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T3E 6K6. [email:[email protected]]

CARRY I NG TH E BURDEN O F PAST V I O L ENC E S 2 9 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Mou

nt R

oyal

Uni

vers

ity]

at 1

4:31

18

Dec

embe

r 20

13

![POUR UNE CONFÉDÉRATION PALESTINIENNE [For a Palestinian Confederation]](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/631617cf511772fe4510aa46/pour-une-confederation-palestinienne-for-a-palestinian-confederation.jpg)