Cardiovascular risk in patients admitted for psychosis compared with findings from a...

-

Upload

helse-bergen -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Cardiovascular risk in patients admitted for psychosis compared with findings from a...

Cardiovascular risk in patients admitted for psychosis compared with fi ndings from a population-based study ERIK JOHNSEN , ROLF GJESTAD , RUNE A. KROKEN , LIV MELLESDAL , ELSE-MARIE L Ø BERG, HUGO A. J Ø RGENSEN

Johnsen E, Gjestad R, Kroken RA, Mellesdal L, L ø berg E-M, J ø rgensen HA. Cardiovascular risk in patients admitted for psychosis compared with fi ndings from a population-based study. Nord J Psychiatry 2011;65:192–202.

Background: Schizophrenia and related psychoses are associated with excess morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD). Single-site studies on CVD-related risk factors in representative samples of acutely admitted inpatients are scarce. Aims: To assess the levels of risk factors related to CVD in patients acutely admitted to hospital for symptoms of psychosis. Methods: Eligible patients aged 18 – 65 years were included consecutively in the Bergen Psycho-sis Project (BPP). CVD-related risk factors were recorded at admittance and at discharge or after 6 weeks at the latest. The recordings of 218 patients with psychosis (BPP) were compared with the fi ndings of 50,219 subjects from the population-based Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97 (HUNT2) survey. Results: Diastolic blood pressures were higher for BPP women and men, whereas body mass indexes (BMIs) and total cholesterol levels were higher in HUNT2 women and men. On categorical measures, smoking was more prevalent in the patients com-pared with the HUNT2 subjects. Metabolic syndrome was present in 11.8% and 21.9% of BPP women and men, respectively. At discharge or 6 weeks from admission, 3.2% and 18.6% of BPP women and men, respectively, had metabolic syndrome. BMIs and total cholesterol levels had worsened during the inpatient treatment period. Only one patient had a diagnosis corre-sponding to the CVD risk found, and only four patients received antidiabetics, antihypertensives or lipid-lowering drugs. Conclusions: Some CVD-related risk factors were high in the patients at admission, some worsened and CVD risk factors seem to be suboptimally addressed, which should warrant increased awareness on the topic in clinical practice.

• Adverse effects , Antipsychotics , Psychosis.

Erik Johnsen, M.D., Ph.D, Haukeland University Hospital, University of Bergen, Department of Clinical Medicine, Section of Psychiatry, Sandviken, Pb 23, N-5812 Bergen, Norway, E-mail: [email protected]; Accepted 2 September 2010.

For patients suffering from schizophrenia and related

psychoses, the excess morbidity and mortality associ-

ated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) is indicated in

both US and European populations (1 – 3). The association

seems to be multifactorial, and may include factors

related to the mental disorders themselves and to general

characteristics of the modern western society with easy

access to tobacco and high-caloric foods and beverages,

combined with physically undemanding environments.

Mental-disease-related factors include the passive lifestyle

associated with symptoms of psychosis and inpatient

treatment, as well as adverse metabolic effects of antipsy-

chotic drugs. With the introduction of second-generation

antipsychotics (SGAs), the focus has increasingly been

directed at antipsychotic-induced dyslipidemia, diabetes

mellitus and obesity, even though these metabolic effects

have been associated with antipsychotic drugs for half a

century (4, 5). Several recent pragmatic trials on the

effectiveness of antipsychotics supply valuable informa-

tion on the present CVD risk profi les in large, well-char-

acterized samples of psychotic patients (6). In the US

CATIE study that included 1493 patients with chronic

schizophrenia with an antipsychotic drug history of about

14 years, disturbingly high baseline prevalence fi gures for

CVD risk factors were revealed (7). Similar trends were

found in a Norwegian survey, the Ulleval 600 (U600)

outpatient study, including outpatients with severe mental

illness (8). In the EUFEST study conducted in Europe

and Israel, 498 fi rst-episode patients with schizophrenia,

schizophreniform disorder or schizoaffective disorder

© 2011 Informa Healthcare DOI: 10.3109/08039488.2010.522729

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PATIENTS ADMITTED FOR PSYCHOSIS

NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011 193

Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (10). Eligible patients met

ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffec-

tive disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic

episode, delusional disorder, drug-induced psychosis,

bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder with psy-

chotic features, as determined by experienced clinicians

(11). No inter-rater reliability testing was performed.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were

unable to use oral antipsychotics, were suffering from a

manic psychosis, were unable to cooperate reliably dur-

ing investigations, did not understand spoken Norwegian,

were candidates for electroconvulsive therapy or were

medicated with clozapine on admittance. Two hundred

and eighteen patients were consecutively included. The

sample represents 30.5% of all patients acutely admitted

from the catchment area because of symptoms of psycho-

sis and who were candidates for oral antipsychotic drugs.

To the best knowledge of the authors, this fi gure is prob-

ably higher than in most other clinical antipsychotic drug

studies (12 – 15). The distribution of reasons for exclusion

were not meeting inclusion criteria according to the

PANSS (1.2%); patients unable to assess because of

uncooperativeness or organic brain disorders (46.5%);

participation in the study not acceptable to the treating

clinician or patient (6.8%); and administrative causes,

principally discharge of patient before assessments could

be made (15.0%).

Assessments Assessments were made at admittance and at discharge

or 6 weeks from admittance at the latest. The patients ’

levels of psychiatric symptoms were rated. Height and

weight were measured with the patient wearing light

clothes and no shoes. Blood pressure (BP) was usually

measured after rest in the supine position using a manual

Welch Allyn CE 0123 BP unit. The same cuff size was

applied in all patients. On rare occasions, the patient ’ s

mental condition made physical examination impossible

on admittance, and the examinations had to be performed

within the next few days. Blood samples were collected

in the fasting state within the fi rst few days and analyzed

for levels of glucose, total cholesterols, high-density lipo-

protein (HDL)-cholesterols and triglycerides at the Hauke-

land University Hospital, Department of Clinical

Chemistry, by means of a Modular Analytics from Roche

Diagnostics, Roche Holding AG, Switzerland. The clini-

cal characteristics of the BPP sample are presented in

Table 1 (16 – 19).

The Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97 (HUNT2) The HUNT2 study was a population-based health survey

conducted in the Nord-Tr ø ndelag County in Norway

between August 1995 and June 1997. Nord-Tr ø ndelag

County is considered representative of Norway in most

were included, of whom about one-third were antipsy-

chotic drug na ï ve (9). Lower levels of CVD risk factors

were found in the EUFEST study compared with the

CATIE and U600 studies. The obvious dissimilarities in

CVD risk profi les between different studies, regions and

populations necessitate more studies to elaborate further

the CVD risk characteristics in different well-defi ned

populations suffering from psychosis. In this regard, stud-

ies on the CVD risk in samples of patients admitted to

hospital are particularly scarce.

Aims The primary aim of the present study was to assess the

levels of risk factors related to CVD in psychotic patients

admitted to the Division of Psychiatry at Haukeland Uni-

versity Hospital, which is responsible for all the acute

admissions in the catchment area of about 400,000 inhab-

itants, thus supplying information from a diverse popula-

tion representing everyday clinical practice, and compare

the fi ndings with fi gures in the general population. Sec-

ondary aims were to investigate the association between

demographic variables and metabolic risk factors, to

assess the level of CVD risk factors at discharge or at 6

weeks from admittance at the latest, and to assess the

prevalence of prescriptions of antihypertensives, antidia-

betics and lipid-lowering drugs.

Material and Methods The Bergen Psychosis Project (BPP) The BPP is a prospective study comparing SGAs in the

treatment of psychosis. The assessment of risk factors

associated with the disorders and their treatments is a

primary objective in the BPP. Patients were recruited

from March 2004 until February 2009. All patients were

recruited from Haukeland University Hospital, Division

of Psychiatry, with a catchment population of about

400,000. The BPP was approved by the Regional Com-

mittee for Medical Research Ethics, and the Norwegian

Social Science Data Services. Funding of the project was

initiated by the Research Council of Norway, followed

by Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psychia-

try. The BPP has not received any fi nancial or other sup-

port from the pharmaceutical industry. All assessments

reported in this paper were part of the hospital ’ s routine

for the management of patients suffering from psychosis

and have become part of the patients ’ medical records.

Patients Patients from 18 – 65 years of age were eligible for the

study if they were admitted to the emergency ward for

symptoms of acute psychosis as determined by a score of

� 4 on one or more of the items Delusions, Hallucinatory

behavior, Grandiosity, Suspiciousness/persecution or

Unusual thought content from the Positive and Negative

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

E JOHNSEN ET AL.

194 NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011

BP was measured by specifi cally trained nurses or tech-

nicians using a Dinamap 845XT (Critikon) based on osc-

illometry, with cuff sizes adjusted to the arm

circumferences. Child cuff, adult cuff, large adult cuff

and adult thigh cuff were used when arm circumference

ranges (cm) at midpoint were � 27, 27 – 34, 35 – 44 or 45 –

52, respectively. BP was measured three times at 1-min

intervals after the participant had been seated for 2 min.

During height and weight measurements, the participants

were wearing light clothes and no shoes. Whole blood

was drawn in the non-fasting state and analyzed for

serum total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides

and glucose. The samples were sent in a cooler to the

Central Laboratory at Levanger Hospital, Levanger, on

the same day or within the fi rst few days, and serum

analyses were performed on fresh blood samples.

Data analysis The analyses were performed in women and men sepa-

rately both in the total sample, and in strata according to

the three age groups: young age (18 – 34 years), middle

age (35 – 49 years) and old age (50 – 65 years). Cut-off

values for continuous metabolic risk factors associated

with CVD, in the following labeled CVD risk factors,

were set according to the following values defi ned by

the World Health Organization (WHO) (21): obesity as

body mass index (BMI) � 30 body weight in kilograms

(kg)/height in meters squared (m 2 ); hypertension as arte-

rial systolic BP � 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP � 90

mmHg; hyperglycemia as fasting plasma glucose � 6.1

mmol/l; low HDL as � 0.9 mmol/l in men and � 1.0 in

women; hypertriglyceridemia as fasting triglycerides

� 1.7 mmol/l. As the BP was determined from a single

measurement in the BPP, whereas three measurements

were performed in the HUNT2 followed by calculating

the average of measurements 2 and 3, the fi rst recording

was used in comparisons with the BPP. In addition, to

adjust for only one BP measurement in the BPP, the dif-

ference between the fi rst and the mean of the second and

third recordings in the HUNT2 was used in a linear

regression model to estimate a BP-measurement-adjusted

value in the BPP, corresponding to the mean BP of

recordings 2 and 3 in the HUNT2. Hypercholesterolemia

was defi ned as total cholesterol � 6.2 mmol/l (22). Meta-

bolic syndrome was defi ned according to the Third Report

of the National Cholesterol Education Program with later

modifi cations (22, 23). The syndrome is present when

three or more of the criteria abdominal obesity, hyperten-

sion, low HDL, hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia

are present. In this study, BMI � 30 kg/m 2 was used in

lieu of waist circumference to defi ne obesity. As blood

samples were drawn in the non-fasting state in the

HUNT2 sample, metabolic syndrome was calculated for

the BPP sample only.

respects (20). The primary objectives of the survey were

related to major public health issues such as CVD, diabe-

tes, obstructive lung disease, osteoporosis and mental

health. The survey was approved by the Data Inspectorate

of Norway, and recommended by the Regional Commit-

tee for Medical Research Ethics. Each participant pro-

vided written consent. Further details about the study

have been presented in previous publications (20).

Subjects All citizens aged 20 years and older were invited by let-

ter to participate in the survey. Of the 94,194 individuals

invited, 66,140 (70.2%) participated. For comparison pur-

poses, subjects older than 65 years were excluded from

analyses. The remaining reference group included 26,444

women and 23,775 men.

Assessments The participants completed two separate questionnaires

on health-related issues, one sent by mail attached to the

invitation letter, and one handed out at the screening site.

Table 1 . Clinical characteristics of the Bergen Psychosis Project (BPP) sample.

Women

( n � 71)

Men

( n � 147)

Diagnosis, %

Schizophrenia and related 44.9 43.2

Acute 15.9 24.1

Drug-induced 11.6 14.9

Affective 11.6 9.9

Psychosis unspecifi ed 15.8 7.7

Alcohol use, %

None 22.5 17.8

Misuse 11.3 10.3

Illicit drug use, %

None 75.7 63.0

Misuse 11.5 22.0

Antipsychotic na ï ve, % 47.9 42.9

First admission, % 50.7 57.1

Symptoms, mean ( s )

PANSS total 75.5 (12.9) 73.8 (13.7)

PANSS positive subscale 20.0 (4.5) 19.9 (4.4)

PANSS negative subscale 20.5 (7.2) 19.5 (7.6)

PANSS general subscale 35.1 (6.9) 34.4 (6.9)

CDSS 6.9 (5.4) 6.4 (5.3)

GAF-F 30.3 (5.0) 30.8 (6.5)

CGI-S 5.2 (0.6) 5.2 (0.6)

s , standard deviation; Antipsychotic na ï ve, has not used antipsychotic drugs

before index admission; First admission, index admission is the fi rst

admission to a mental hospital; Misuse, misuse or dependence (16);

Schizophrenia and related, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional

disorder; Acute, acute and transient psychotic disorders; Drug-induced, drug-

induced psychosis; Affective, bipolar disorder or unipolar depression with

psychotic features; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (10);

CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (17); GAF-F, Global

Assessment of Functioning, split version, Functions scale (18); CGI-S,

Clinical Global Impression, severity of symptoms scale (19).

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PATIENTS ADMITTED FOR PSYCHOSIS

NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011 195

fi ve patients were south-east Asians, three were Africans,

fi ve were South-Americans, three were from the Middle

East; four patients had a multi-ethnic background.

Age-adjusted levels of continuous CVD risk factors

in the two samples are compared in Table 3. Supple-

mental multivariate analyses of variance that adjusted

for differences in marital status and level of education,

in addition to age, revealed similar fi ndings in compari-

sons between the samples, with two exceptions: there

were interaction effects between sample and marital sta-

tus for systolic BP in women, and the systolic BP was

signifi cantly higher in unmarried HUNT2 women com-

pared with their BPP counterparts [GLM: P � 0.041;

mean difference 5.47 mmHg; 95% confi dence interval

(CI) 0.23 – 10.71]. Furthermore, there were interaction

effects between sample and age, and between sample

and level of education in men for diastolic BP, and dia-

stolic BP was not different between samples in men

with higher education. In analyses across the samples,

higher levels of education were generally associated with

lower levels of CVD risk factors in both sexes. Unmar-

ried status was associated with higher CVD risk factor

levels in women, whereas the associations were less

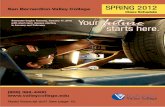

clear-cut in men. Prevalence of categorical risk factors

is displayed in Fig. 1. Metabolic syndrome was present

in 11.8% and 21.9% of BPP women and men, respec-

tively. When BP-measurement-adjusted recordings were

applied, systolic hypertension was present in 13.4% and

30.4% of BPP women and men, respectively, whereas

the corresponding fi gures for diastolic hypertension were

14.9% and 25.9%. Systolic hypertension was no longer

statistically different between the samples in logistic

regression analyses that adjusted for age differences.

Statistics Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 15

(SPSS, Chicago, IL). A one-way ANOVA was used for

comparisons of continuous demographic and clinical base-

line data. To adjust for differences in mean age between

BPP and HUNT2 groups, multivariate analyses of vari-

ance – general linear models (GLM) were applied for con-

tinuous metabolic risk factor data. For multiple comparisons,

Bonferroni adjustments were used. Supplemental analyses

that adjusted for differences in marital status and educa-

tional level, in addition to age, between the samples were

also carried out. Analyses on associations between demo-

graphic characteristics and metabolic risk factors were

done by means of Pearson ’ s correlation coeffi cient ( r ).

Cross-tabulation of categorical data was analyzed by means

of χ 2 tests (Fisher ’ s exact test). To adjust for age differ-

ences across the samples, categorical data were analyzed

by means of logistic regression. For analyzing differences

between baseline and retest, continuous CVD risk factors

in the BPP sample a paired samples t -test was used. Two-

tailed levels of signifi cance were used.

Results The demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Mean age was signifi cantly higher in the HUNT2 sample

for the overall age comparisons and the young age groups

comparisons. In the HUNT2 study, 52.7% of the subjects

were women, compared with 32.6% in the BPP. Less

than 3% of the HUNT2 sample was non-Caucasian (20),

whereas the corresponding fi gure was 9.2% in the BPP.

No further details on the ethnicity of the non-Caucasians

in the HUNT2 sample were available. In the BPP sample,

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the Bergen Psychosis Project (BPP) and Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97 (HUNT2) samples.

Women Men

Variables BPP HUNT BPP HUNT

All ages (18 – 65 years) n � 71 n � 26444 n � 147 n � 23775

Age, years ( s ) 34.3 (13.0) 42.6 (12.3) ∗ ∗ ∗ 32.9 (12.1) 43.1 (12.1) ∗ ∗ ∗

Higher education, % 18.6 23.8 13.6 22.6 ∗ ∗

Unmarried, % 58.6 25.2 ∗ ∗ ∗ 82.1 33.5 ∗ ∗ ∗

Young (18 – 35 years) n � 41 n � 8308 n � 98 n � 7102

Age, years ( s ) 24.6 (4.9) 28.1 (4.6) ∗ ∗ ∗ 25.7 (4.9) 28.3 (4.5) ∗ ∗ ∗

Higher education, % 15.0 31.3 ∗ 10.2 21.9 ∗ ∗

Unmarried, % 77.5 64.1 96.9 77.0 ∗ ∗ ∗

Middle (36 – 50 years) n � 22 n � 10335 n � 32 n � 9452

Age, years ( s ) 44.0 (4.5) 43.2 (4.3) 41.6 (4.1) 43.3 (4.3) ∗

Higher education, % 22.7 25.3 25.0 25.8

Unmarried, % 31.8 10.6 ∗ ∗ 59.4 19.7 ∗ ∗ ∗

Old (51 – 65 years) n � 8 n � 7801 n � 17 n � 7221

Age, years ( s ) 57.9 (2.3) 57.4 (4.2) 57.9 (4.8) 57.4 (4.4)

Higher education, % 25.0 13.6 11.8 19.0

Unmarried, % 37.5 3.4 ∗ ∗ 41.2 8.6 ∗ ∗ ∗

Higher education, university level education or corresponding; s , standard deviation.

∗ P � 0.05; ∗ ∗ P � 0.01; ∗ ∗ ∗ P � 0.001, refers to comparisons between BPP and HUNT2 for women and men separately.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

E JOHNSEN ET AL.

196 NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011

rates of systolic hypertension and obesity (logistic regres-

sion: P � 0.001). Unmarried HUNT2 women had higher

rates of diastolic hypertension, hyperglycemia, hypercho-

lesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic syn-

drome (logistic regression: P � 0.05 for all) compared with

the rest. Unmarried HUNT2 men had higher smoking

rates lower rates of hypercholesterolemia and hypertrig-

lyceridemia compared with the rest (logistic regression:

P � 0.01 for all).

Subanalyses in the BPP revealed that male but not

female patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective dis-

order had a lower mean level of HDL-cholesterol ( t -test:

P � 0.014; mean difference 0.01 mM/l; CI � 0.34 to

� 0.04), higher mean level of triglycerides ( t -test:

P � 0.018; mean difference 0.43 mM/l; CI 0.07 – 0.78). The

results remained essentially the same in age-adjusted

analyses. Male but not female patients with schizophrenia

When BP-measurement-adjusted values were applied,

metabolic syndrome was present in 8.1% and 17.9% of

BPP women and men, respectively.

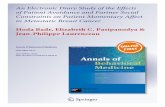

The rates of categorical CVD risk factors in the dif-

ferent age strata are displayed in Fig. 2. In the BPP, age

was signifi cantly positively correlated with diastolic BP

( r � 0.251; P � 0.001) and total cholesterols ( r � 0.288;

P � 0.001) for both sexes, but with systolic BP ( r � 0.627,

P � 0.001) and BMI ( r � 0.358; P � 0.006) in women only.

Unmarried BPP men had a higher rate of smoking com-

pared with married men in age adjusted analyses (logis-

tic regression: P � 0.012), whereas non-Caucasian men

had higher rates of hyperglycemia compared with Cauca-

sian men (logistic regression: P � 0.010). In the HUNT2

sample, age was positively correlated with levels of all

CVD risk factors in both sexes ( r between 0.060 and

0.464; P � 0.001). Unmarried HUNT2 subjects had higher

Table 3 . Baseline cardiovascular disease-related risk factors; age-adjusted measures by sex and sample.

Women Men

Variables (95% CI) BPP HUNT BPP HUNT

All ages (18 – 65 years) n � 71 n � 26444 n � 147 n � 23775

Systolic BP (mmHg) 132.18 (128.19 – 136.17) 132.72 (132.52 – 132.92) 141.56 (138.92 – 144.19) 140.63 (140.43 – 140.83)

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 84.84 (82.17 – 87.52) 80.12 (79.99 – 80.25) ∗ ∗ 91.57(89.69 – 93.45) 84.43 (84.29 – 84.57) ∗ ∗ ∗

BMI (kg/m 2 ) 24.30 (23.16 – 25.43) 25.85 (25.80 – 25.90) ∗ ∗ 24.41 (23.79 – 25.03) 26.41 (26.37 – 26.45) ∗ ∗ ∗

Glucose (mM/l) 5.38 (5.12 – 5.63) 5.20 (5.18 – 5.21) † 5.70 (5.47 – 5.92) 5.39 (5.37 – 5.40) †

Cholesterol (mM/l) 5.00 (4.73 – 5.28) 5.69 (5.67 – 5.70) ∗ ∗ ∗ 4.98 (4.79 – 5.17) 5.73 (5.72 – 5.74) ∗ ∗ ∗

HDL (mM/l) 1.49 (1.38 – 1.59) 1.51 (1.50 – 1.51) 1.29 (1.22 – 1.35) 1.24 (1.23 – 1.24)

Triglycerides (mM/l) 1.29 (1.05 – 1.53) 1.45 (1.44 – 1.46) † 1.53 (1.29 – 1.77) 1.97 (1.95 – 1.99)†

Young (18 – 35 years) n � 41 n � 8308 n � 98 n � 7102

Systolic BP (mmHg) 117.83 (113.87 – 121.78) 125.15 (124.87 – 125.42) ∗ ∗ ∗ 135.67 (133.01 – 138.32) 137.72 (137.42 – 138.02)

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 77.91 (74.86 – 80.96) 74.64 (74.43 – 74.85) ∗ 86.76 (84.66 – 88.85) 78.43 (78.19 – 78.66) ∗ ∗ ∗

BMI (kg/m 2 ) 21.93 (20.46 – 23.39) 24.81 (24.72 – 24.90) ∗ ∗ ∗ 24.13 (23.36 – 24.90) 25.54 (25.46 – 25.62) ∗ ∗ ∗

Glucose (mM/l) 5.11 (4.85 – 5.37) 4.90 (4.88 – 4.92) † 5.41 (5.19 – 5.63) 5.04 (5.01 – 5.06) †

Cholesterol (mM/l) 4.39 (4.05 – 4.72) 5.00 (4.98 – 5.02) ∗ ∗ ∗ 4.64 (4.43 – 4.85) 5.06 (5.03 – 5.08) ∗ ∗ ∗

HDL (mM/l) 1.42 (1.30 – 1.54) 1.48 (1.47 – 1.48) 1.24 (1.18 – 1.31) 1.21 (1.21 – 1.22)

Triglycerides (mM/l) 0.99 (0.74 – 1.24) 1.24 (1.23 – 1.26) † 1.44 (1.18 – 1.69) 1.73 (1.71 – 1.76) †

Middle (36 – 50 years) n � 22 n � 10335 n � 32 n � 9452

Systolic BP (mmHg) 132.79 (126.00 – 139.57) 130.64 (130.32 – 130.95) 145.52 (140.21 – 150.83) 138.51 (138.21 – 138.80) ∗

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 86.09 (81.42 – 90.76) 80.22 (80.01 – 80.44) ∗ 94.64 (90.65 – 98.62) 85.09 (84.87 – 85.31) ∗ ∗ ∗

BMI (kg/m 2 ) 26.53 (24.63 – 28.43) 25.68 (25.59 – 25.76) 24.15 (22.81 – 25.48) 26.57 (26.50 – 26.63) ∗ ∗ ∗

Glucose (mM/l) 5.19 (4.77 – 5.61) 5.20 (5.18 – 5.22) † 5.57 (5.15 – 5.99) 5.35 (5.33 – 5.38)†

Cholesterol (mM/l) 4.77 (4.32 – 5.22) 5.59 (5.57 – 5.61) ∗ ∗ ∗ 4.93 (4.52 – 5.35) 5.89 (5.87 – 5.91) ∗ ∗ ∗

HDL (mM/l) 1.56 (1.39 – 1.73) 1.50 (1.50 – 1.51) 1.21 (1.08 – 1.35) 1.23 (1.22 – 1.23)

Triglycerides (mM/l) 1.40 (0.99 – 1.82) 1.39 (1.37 – 1.41) † 1.49 (0.93 – 2.05) 2.08 (2.06 – 2.11) †

Old (51 – 65 years) n � 8 n � 7801 n � 17 n � 7221

Systolic BP (mmHg) 158.10 (142.20 – 173.99) 143.61 (143.17 – 144.05) 142.87 (134.02 – 151.73) 146.33 (145.90 – 146.76)

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 91.57 (81.55 – 101.59) 85.85 (85.57 – 86.12) 89.40 (83.62 – 95.17) 89.53 (89.25 – 89.81)

BMI (kg/m 2 ) 24.85 (20.80 – 28.89) 27.19 (27.09 – 27.29) 24.26 (22.51 – 26.01) 27.06 (26.98 – 27.14) ∗ ∗

Glucose (mM/l) 5.88 (4.83 – 6.93) 5.52 (5.48 – 5.55) † 5.86 (5.01 – 6.72) 5.78 (5.73 – 5.82) †

Cholesterol (mM/l) 5.21 (4.17 – 6.25) 6.55 (6.53 – 6.58) ∗ 4.97 (4.41 – 5.52) 6.18 (6.15 – 6.20) ∗ ∗ ∗

HDL (mM/l) 1.31 (0.73 – 1.90) 1.54 (1.53 – 1.55) 1.47 (1.27 – 1.66) 1.28 (1.27 – 1.29)

Triglycerides (mM/l) 0.93 ( � 0.27 to 2.13) 1.75 (1.72 – 1.77) † 1.68 (0.95 – 2.41) 2.06 (2.03 – 2.09) †

BPP, Bergen Psychosis Project; HUNT2, Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97; BP, arterial blood pressure, single-measurement values; BMI, body

mass index; Cholesterol, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; IU, International Units.

∗ P � 0.05; ∗ ∗ P � 0.01; ∗ ∗ ∗ P � 0.001, refers to comparisons between BPP and HUNT2 for women and men separately. Bonferroni adjustments were made

for multiple comparisons. † Signifi cance testing not performed because of non-fasting state in the HUNT2 sample.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PATIENTS ADMITTED FOR PSYCHOSIS

NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011 197

times. When BP-measurement-adjusted recordings were

applied, the rates at retest for women and men respec-

tively, were 6.7% and 25.0% for systolic hypertension,

6.7% and 13.3% diastolic hypertension, and 3.2% and

16.7% metabolic syndrome. One woman used cholester-

ol-reducing medication, whereas two men used antihy-

pertensive drugs and one man used antidiabetic

medication. Regarding diagnoses of medical illness or a

condition relevant to CVD or risk of such, diagnoses of

diabetes mellitus type 2 and chronic obstructive lung dis-

ease were registered in only one patient at discharge.

Discussion The high rates of hypertension and smoking were the

most signifi cant fi ndings in this consecutive BPP sample

admitted for acute psychosis. The BPP patients had higher

mean diastolic BP at admittance compared with the

HUNT2 participants, and the differences of the respective

means were generally substantial, exceeding 7 mmHg in

the male groups. Almost 60% of BPP men had diastolic

hypertension at baseline according to the WHO defi ni-

tions. Arterial hypertension is a strong risk factor for

myocardial infarction, and the hypertension-related risk

of infarction seems to be relatively more pronounced in

the younger population, and in women (24). Furthermore,

diastolic BP seems to be a stronger predictor of coronary

also had higher rates of low HDL (38.7% vs. 20.8%),

triglyceridemia 50.0% vs. 14.1%) and metabolic syn-

drome (44.8% vs. 11.0%) compared with the other

patients (logistic regression: P � 0.05 for all). Antipsy-

chotic-naive male but not female patients had lower

mean values for BMI ( t -test: P � 0.014; mean

difference � – 2.03 kg/m 2 ; CI – 3.65 to – 0.41) and for trig-

lycerides ( t -test: P � 0.031; mean difference � – 0.35 mM/l;

CI – 0.67 to – 0.03). The results remained essentially the

same in age-adjusted analyses. Antipsychotic-na ï ve male

but not female patients also had lower rates of low HDL

(17.0% vs. 35.4%), hypertriglyceridemia (9.3% vs.

35.0%) and metabolic syndrome (7.1% vs. 31.3%) (logis-

tic regression: P � 0.05 for all).

One hundred and fi ve of the BPP patients were

retested at discharge or at 6 weeks at the latest. There

were no baseline differences with regards to demo-

graphic, clinical, or metabolic parameters between those

only tested at baseline and those retested, with the excep-

tion of a slightly higher, though statistically signifi cant

PANSS negative subscale score in those only tested at

baseline ( t -test: P � 0.027; mean difference 2.24 points;

CI 0.26 – 4.22); and a higher proportion with diastolic

hypertension in those tested only at baseline (57.9% vs.

42.1%, Fischer ’ s exact test: P � 0.034). The CVD risk

factor prevalence fi gures and levels at baseline and retest

are displayed in Table 4 for patients with data on both

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Wom

en

Men

Smokers BP-syst BP-diast Obesity Glc Chol Low HDL TG

Prevalen

ce, %

HUNT BPP******

***

****

***

***

¶ ¶

¶

¶

Fig. 1 . Bergen Psychosis Project (BPP) baseline vs. Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97 (HUNT2): prevalence of cardiovascular

disease-related risk factors. The prevalence rates are descriptive and unadjusted for age differences between the samples. Smokers,

present tobacco smokers; BP-syst, systolic hypertension ( � 140 mmHg, single-measurement value); BP-diast, diastolic hypertension

( � 90 mmHg, single-measurement value); obesity, body mass index � 30 kg/m 2 ); Glc, hyperglycemia (serum glucose � 6.1 mM/l; Chol,

hypercholesterolemia (serum total cholesterol � 6.2 mM/l); low HDL, low high-density lipoprotein (serum HDL � 0.9 mM/l in women

and � 1.0 mM/l in men); TG, hypertriglyceridemia (serum triglycerides � 1.7 mM/l). Glc and TG measured in non-fasting state in the

HUNT sample. ∗ P � 0.05; ∗ ∗ P � 0.01; ∗ ∗ ∗ P � 0.001, refers to age-adjusted comparisons between BPP and HUNT2 for women and men

separately. ¶ Signifi cance testing not performed because of non-fasting state in the HUNT2 sample.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

E JOHNSEN ET AL.

198 NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Age groups

Sm

okin

g - P

revalen

ce % ******

***

*

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Sy

sto

lic

H

yp

erte

ns

io

n - P

re

va

le

nc

e %

**

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Dia

sto

lic

H

yp

erte

ns

io

n - P

re

va

le

nc

e %

***

***

*

***

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Ob

esity - P

revalen

ce %

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 yearsAge groups

18-35 years 36-50 years

Age groups

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 years

51-65 years

Age groups

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 years

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Hyp

erg

lycem

ia - P

revalen

ce %

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Hyp

erch

olestero

lem

ia - P

revalen

ce %

Age groups

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 yearsAge groups

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 years

Age groups

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

HUNT WomenBPP Women

HUNT MenBPP Men

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 yearsAge groups

18-35 years 36-50 years 51-65 years0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Lo

w H

DL

- P

revalen

ce %

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Hyp

ertrig

lycerid

em

ia - P

revalen

ce %

Fig. 2. Bergen Psychosis Project (BPP) baseline vs. Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97 (HUNT2): prevalence of cardiovascular disease-related

risk factors in different age groups. The prevalence rates are descriptive and unadjusted for age differences between the samples. Smoking, present

tobacco smokers; Systolic hypertension, systolic blood pressure (BP) � 140 mmHg, single-measurement value; Diastolic hypertension, diastolic

BP � 90 mmHg, single-measurement value; Obesity, body mass index � 30 kg/m 2 ; Hyperglycemia, serum glucose � 6.1 mM/l; Hypercholesterolemia,

serum total cholesterol � 6.2 mM/l; Low HDL, serum low high-density lipoprotein � 0.9 mM/l in women and � 1.0 mM/l in men;

Hypertriglyceridemia, serum triglycerides � 1.7 mM/l. ∗ P � 0.05; ∗ ∗ P � 0.01; ∗ ∗ ∗ P � 0.001; refers to age-adjusted comparisons between BPP and

HUNT2 for women and men separately. Signifi cance testing not performed for Glc and TG because of non-fasting state in the HUNT2 sample.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PATIENTS ADMITTED FOR PSYCHOSIS

NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011 199

range, whereas it will overestimate diastolic BP in the

high range (29). The direction of any resulting bias to the

mean diastolic BPs registered in the HUNT2 sample is

accordingly hard to predict, but we have no reason to

believe this should signifi cantly infl uence the results of

the study. Furthermore, cuff sizes were adjusted accord-

ing to arm circumferences in the HUNT2 sample only. In

patients with large arm circumferences, the standard cuff

generally overestimates the BP (30). However, in the BPP

sample, only about 8% were obese, and we do not believe

this to be the cause of any major bias. Finally, some of

the patients may have been in an aroused state during the

BP recordings at admittance, resulting in artifi cially high

BP measurements. The signifi cantly lower BPs recorded

at discharge or after 6 weeks supports this hypothesis.

The BP recordings at discharge or after 6 weeks are

probably less state dependent, however, but may still be

biased because of stress in the patients.

About two-thirds of the BPP sample were smokers.

In the years since 1997, the proportion of daily smok-

ers has decreased in the general Norwegian population,

and in 2008 was about 21% among adults, which makes

the difference towards BPP patients even more pro-

nounced (31). The WHO Tobacco control database

states that years lost from death by smoking range from

12 – 20 years, and up to 21% of deaths are related to

smoking (32).

About 11% and 22% of BPP women and men,

respectively, had a metabolic syndrome at admittance. The

heart disease risk than systolic BP in those younger than

50 years of age (25). Hypertension is also the most

important risk factor for cerebrovascular stroke (26). A

possible bias may be that only one BP measurement was

performed in the BPP, and for the primary comparisons,

we had to use the fi rst of the three recordings in the

HUNT2 sample. The fi rst recording is usually the high-

est, and it is generally recommended that three succeed-

ing measurements should be undertaken, and the average

used as the BP reading (27). For comparisons, it is note-

worthy, however, that the BP in both the CATIE and the

U600 studies was also determined based on a single mea-

surement (7, 8). Higher BPs were registered in the BPP

compared with the BPs in both of these studies. We

adjusted the BPP recordings for the potential bias associ-

ated with single measurements only, and even after

adjustments, more than a quarter of BPP men had hyper-

tension. Another potential problem may be the fact that

BP measurements were performed in the sitting position

in the HUNT2, whereas most of the BPP measurements

were carried out in supine patients. In a review on the

infl uence of body position on BP readings, the results

differ markedly between studies, as some studies fi nd

equal readings in the sitting and supine position, whereas

other studies report differences that contradict each other

regarding the direction of difference between readings

(28). Different BP measurement equipment was used in

the samples. The Dinamap used in the HUNT2 is known

to underestimate diastolic BP, but only in the lower BP

Table 4 . Prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related risk factors at baseline and discharge/ after 6 weeks.

Baseline Discharge/ 6 weeks

CVD risk factors Women Men Women Men

Rate (%) n � 34 n � 69 n � 34 n � 69

BP-syst 23.5 54.5 10.0 33.3

BP-diast 26.5 47.0 6.7 18.3

Obesity 10.7 8.5 12.0 11.1

Glc 17.6 15.9 3.1 8.1

Chol 6.9 9.8 9.4 6.3

LowHDL 6.9 20.3 3.1 26.6

TG 13.3 20.0 20.7 27.9

MBS 13.8 15.5 3.2 18.6

Mean ( s )

Systolic BP (mmHg) 126.30 (20.59) 137.72 (18.98) 115.63 (14.79) ∗ 133.88 (17.56)

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 80.50 (10.94) 85.89 (13.53) 73.90 (10.99) ∗ 79.81 (11.80) ∗ ∗

BMI (kg/m 2 ) 24.75 (5.65) 23.77 (4.46) 25.29 (5.27) ∗ 24.53 (4.21) ∗ ∗ ∗

Glucose (mM/l) 5.14 (1.07) 5.38 (1.16) 4.89 (0.58) 5.30 (1.85)

Cholesterol (mM/l) 4.74 (1.16) 4.48 (1.11) 5.16 (1.13) ∗ 4.94 (0.94) ∗ ∗ ∗

HDL (mM/l) 1.44 (0.38) 1.29 (0.32) 1.53 (0.39) 1.33 (0.35)

Triglycerides (mM/l) 1.14 (0.83) 1.32 (0.68) 1.23 (0.65) 1.51 (0.78)

BP-syst, systolic hypertension ( � 140 mmHg, single-measurement value); BP-diast, diastolic hypertension ( � 90 mmHg, single-measurement value);

Obesity, body mass index (BMI � 30 kg/m 2 ); Glc, hyperglycemia (serum glucose � 6.1 mM/l; Chol, hypercholesterolemia (serum total cholesterol � 6.2

mM/l); low HDL, low high-density lipoprotein (serum HDL � 0.9 mM/l in women and � 1.0 mM/l in men); TG, hypertriglyceridemia (serum triglycerides

� 1.7 mM/l); MBS, metabolic syndrome; s , standard deviation; BP, arterial blood pressure, single-measurement values; BMI, body mass index;

Cholesterol, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; IU, International Units.

∗ P � 0.05; ∗ ∗ P � 0.01; ∗ ∗ ∗ P � 0.001, refers to paired samples comparisons for women and men separately.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

E JOHNSEN ET AL.

200 NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011

not have mortality as an outcome in our study. Finally,

there were differences between the samples in propor-

tions that were non-Caucasians as about 9% of the BPP

patients were non-Caucasians compared with less than

3% in the HUNT2 sample. Ethnic differences regarding

CVD risk factors are well recognized (7). This may be a

source of bias in the comparisons between the samples.

Given the heterogeneous group of non-Caucasians in the

BPP, the direction of the bias is hard to predict, also

because the details on the non-Caucasians in the HUNT2

sample is unavailable. We do not believe that this intro-

duces any systematic bias to the comparisons between

samples.

At discharge or 6 weeks at the latest, signifi cant propor-

tions of the patients still had adverse CVD risk profi les.

Interestingly, mean BMIs and total cholesterol levels

increased signifi cantly in both genders between baseline

and retest, which may point to adverse infl uences of

treatment-related factors associated with the inpatient

treatment. Only four patients received medication directed

at lowering one or more of the CVD risk factors, and a

diagnosis corresponding to the CVD risk was only regis-

tered in one patient. The relation between the CVD risk

load and the apparent underdiagnosis and undertreatment

of the metabolic adversities is consistent with the fi nd-

ings of others, and indicates that central CVD risk fac-

tors are suboptimally addressed in patients suffering from

psychosis (43, 44).

Some limitations to the study should be discussed.

Even though the exclusion criteria were limited, the BPP

sample represents only about 30% of those assessed for

eligibility, which could be a source of selection bias. As

the main reason for non-inclusion was inability to coop-

erate reliably during assessments, we have reason to

believe that the most gravely ill patients are not repre-

sented in the BPP sample. Theoretically, these patients

are also the least capable of living healthy lives, and

hence our fi ndings may represent underestimations of

CVD risk in the population. Others have found the pro-

portion of patients included in clinical trials to be in the

range of 7 – 27% of those initially assessed (12 – 16).

Patients were included consecutively because of psycho-

sis per se , and diagnostic evaluations were performed

later by the treating clinicians according to usual clinical

practice. No reliability testing among the treating clini-

cians regarding diagnostics was performed, and the diag-

noses should be regarded with some caution. However,

the design was aimed at mimicking the usual clinical

circumstances at admittance, which is often before the

diagnosis for a particular patient is specifi ed, and patients

were accordingly included based on the presence of psy-

chosis per se . The rather low rates of misuse of alcohol

and illicit drugs may point to possible under-estimation

of the misuse. We used the Drake scale (16), which is

interview based. There were no laboratory assessments

proportions with obesity were higher in the HUNT2

sample, though not signifi cantly different from the BPP.

In the general population, the proportions of women

and men with obesity are 8% and 9%, respectively,

but increasing (33, 34). The fi gures are close to the

proportions with obesity in the BPP.

When comparing the categorical risk factors in differ-

ent age strata, the age-specifi c rates generally follow a

relatively linear curve over increasing age strata, with

the highest rates in the highest age groups for the

HUNT2 sample. In BPP patients, on the other hand, the

rates peak in the middle-age stratum for several CVD

risk factors in men. One possible explanation for the dif-

ference between the patients and the normal population

may be a selection effect related to the fact that the

patients die earlier than the controls. In the old-age stra-

tum, proportionally more of the CVD high-risk patients

are already dead because of CVD, and the remaining

survivors are the fi ttest ones in the population. We can-

not explain the major difference in rates of low HDL in

BPP patients older than 50 years.

The BPP sample had an overall more favorable CVD

risk factor profi le compared with the majority of studies

in chronic schizophrenia patients where the prevalence of

metabolic syndrome is above 30% in most other studies

also including European samples (35 – 39). Compared

with fi rst-episode studies, the EUFEST sample had lower

rates of obesity compared with the BPP sample, whereas

the prevalence of most other CVD risk factors were not

substantially different between the studies. In a European

retrospective chart review of fi rst-episode schizophrenia,

the rate of metabolic syndrome was only 5% at baseline

(40). In the BPP sample, more than 50% were fi rst time

admissions to hospital, which probably explains why the

metabolic profi le is closer to that of the fi rst-episode

studies. Furthermore, the BPP sample is more heteroge-

neous with respect to diagnostic categories compared

with the other studies, resulting in the representation also

of populations with less severe psychopathology and

metabolic profi les. This is relevant, as different psychiat-

ric diagnoses have been demonstrated to be independent

risk factors for metabolic disturbances (41).

Regarding differences in demographic variables, BPP

patients were younger than the HUNT2 subjects, which

is adjusted for in the analyses. There were differences

between the samples concerning the proportions with

higher education and unmarried status. Those with

higher education had lower levels of CVD risk factors

in both sexes, which is consistent with fi ndings in other

studies (42). In our study, unmarried status was associ-

ated with higher levels of CVD risk factors, but the

association was most consistent in women. Unmarried

status has previously been demonstrated to be associated

with a higher risk of mortality from CVD in men only

(42). The studies are not directly comparable, as we did

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PATIENTS ADMITTED FOR PSYCHOSIS

NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011 201

Disclosure of interest Funding support: Funding of the project was initiated by

the Research Council of Norway, followed by Helse Vest

RHF and Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psy-

chiatry.

Financial disclosure: EJ has received honoraria for lectures

given in meetings arranged by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli

Lilly and AstraZeneca, and for a contribution to an informa-

tion brochure by Eli Lilly.

References Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in 1. schizophrenia. Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1123 – 31. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, Casey DE. Schizophre-2. nia and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J 2005;150:1115 – 21. Ö sby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Spar é n P. Time trends 3. in schizophrenia mortality in Stockholm County, Sweden: Cohort study. BMJ 2000;321:483 – 4. Henderson DC. Weight gain with atypical antipsychotics: Evi-4. dence and insights. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68 Suppl 12:18 – 26. Newcomer JW. Metabolic considerations in the use of antipsy-5. chotic medications: A review of recent evidence. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68 Suppl 1:20 – 7. March JS, Silva SG, Compton S, Shapiro M, Califf R, Krishnan 6. R. The case for practical clinical trials in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:836 – 46. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, Nashrallah HA, Davis SM, 7. Sullivan L, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophrenia Res 2005;80:19 – 32. Birkenaes AB, S ø gaard AJ, Engh JA, Jonsdottir H, Ringen A, 8. Engh JA, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics and cardiovascu-lar risk factors in patients with severe mental disorders compared with the general population. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:425 – 33. Kahn R, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, Davidson M, Vergouwe Y, 9. Keet IPM, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in fi rst-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: An open randomized clinical trial. Lancet 2008;371:1085 – 97. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome 10. scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987;13:261 – 76. World Health Organization. International statistical classifi cation 11. of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, version for 2007. World Health Organization/German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information; 1994/2006. http://www.who.int/classifi cations/apps/icd/icd10online/. Accessed November 2, 2008. Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, Liu-Mares W, Collins J, 12. Warren S, et al. Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperi-dol in the treatment of schizophrenia. JAMA 2003;290:2693 – 702. Bowen J, Hirsch S. Recruitment rates and factors affecting recruit-13. ments for a clinical trial of a putative anti-psychotic agent in the treatment of acute schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol 1992;7:337 – 41. Robinson D, Woerner M, Pollack S, Lerner C. Subject selection 14. biases in clinical trials: Data from a multicenter schizophrenia treat-ment study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:170 – 6. Hofer A, Hummer M, Huber R, Kurz M, Walch T, Fleischhacker 15. WW. Selection bias in clinical trials with antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:699 – 702. Drake RE, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT. Assessing substance use dis-16. order in persons with severe mental illness. New Dir Ment Health Serv 1996;70:3 – 17.

in this regard. The sample was collected in a single site

hospital, which could limit the generalizability of the

results. On the other hand, the hospital was responsible

for all the acute admissions in the catchment area of

about 400,000, thus supplying information from a large

and diverse population representing everyday clinical

practice. Also, the single-site design theoretically facili-

tates better control with the recruitment process. As

mentioned for the BP recordings, some of the other data

may also be state dependent. The retest data may accord-

ingly have higher validity. We used obesity in lieu of

the waist circumference criterion, which could have led

to an underestimation of metabolic syndrome in our

sample (45). Moreover, there was an 8 – 10-year gap in

time between the BPP and HUNT2 studies. Metabolic

characteristics in a population may change in this period,

as we have already commented on concerning smoking

habits and obesity. The large number of subjects in the

HUNT2 study increases the risk of statistical type 1

errors, as statistically signifi cant differences may be

found that are not clinically relevant. By reporting abso-

lute fi gures for the variables in question for both sam-

ples, as well as reporting confi dence intervals for

continuous data, the issue of clinically relevant differ-

ences should be handled. Finally, some of the subgroup

analyses may have too low numbers to make valid sta-

tistical conclusions.

Conclusion Despite the limitations mentioned, we conclude that in

this sample of patients, some risk factors related to CVD

are prevalent. Compared with the general population,

smoking and arterial hypertension seems to be especially

prevalent and should call for attention. Other risk factors

were equally prevalent in the population-based study,

thus modifying the fi ndings of other studies such as the

CATIE. Importantly, some CVD risk factors worsened

during the inpatient treatment. The risk factors are all

modifi able, but seem to be suboptimally recognized and

treated. Because of issues related to the mental illness

itself, such as suspiciousness and lack of insight, some of

the patients may be reluctant to visit their GPs. Admit-

tance to hospital thus represents an important opportunity

to monitor and manage the risk factors in question and

updated guidelines are available in this regard (46, 47).

Acknowledgement — Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov ID; URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/: NCT00932529. The Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study (HUNT Study) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Nord-Tr ø ndelag County Council and the Norwe-gian Institute of Public Health. The authors thank research nurses Ingvild Helle and Marianne Langeland at the Research Department, Division of Psychiatry, Haukeland University Hospital, for their contri-butions. We also wish to thank the Division of Psychiatry, Haukeland University Hospital, for fi nancial support, and the Clinical Departments for enthusiasm and cooperation.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.

E JOHNSEN ET AL.

202 NORD J PSYCHIATRY·VOL 65·NO 3·2011

De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, Van Winkel R. Metabolic 35. syndrome in people with schizophrenia: A review. World Psychiatry 2009;8:15 – 22. Meyer JM, Stahl. The metabolic syndrome and schizophrenia. Acta 36. Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:4 – 14. Schorr SG, Slooff CJ, Bruggeman R, Taxis K. The incidence of 37. metabolic syndrome and its reversal in a cohort of schizophrenic patients followed for one year. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43:1106 – 11. Bobes J, Arango C, Aranda P, Carmena R, Garcia-Garcia M, Rejas 38. J. Cardiovascular and metabolic risk in outpatients with schizophre-nia treated with antipsychotics: Results of the CLAMORS Study. Schizophrenia Res 2007;90:162 – 73. De Hert M, Van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, Wampers M, 39. Scheen A, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia over the course of the ill-ness: A cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2006;2:14. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K., Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, 40. Š inko S, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in fi rst-episode patients with schizophrenia: A retrospective chart review. Schizophrenia Res 2008;101:295 – 303. van Winkel R, van Os J, Celic I, Van Eyck D, Wampers M, Scheen 41. A, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis as an independent risk factor for met-abolic disturbances: Results from a comprehensive, naturalistic screening program. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:1319 – 27. Strand BH, Tverdal A. Can cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle 42. explain the educational inequalities in mortality from ischaemic heart disease and from other heart diseases? 26 year follow up of 50 000 Norwegian men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:705 – 9. Meyer JM, Koro CE. The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum 43. lipids: A comprehensive review. Schizophrenia Res 2004;70:1 – 17. Frayne SM, Halanych JH, Miller DR, Wang F, Liu H, Pogach L, 44. et al. Disparities in diabetes care. Impact of mental illness. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:2631 – 8. Hu G, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Balkau B, Borch-Johnsen K, Pyorala 45. K; for the DECODE Study Group. Prevalence of the metabolic syn-drome and its relation to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in nondiabetic European men and women. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1066 – 76. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, Erlinge D, Jarbin H, 46. Lindstr ö m K, et al. Swedish Clinical Guidelines — Prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry; in press. De Hert M, Dekker JM, Wood D, Kahl KG, Holt RIG, M ö ller HJ, 47. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Dia-betes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Psychiatry 2009;24:412 – 24.

Erik Johnsen, M.D., Ph.D., Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psychiatry, Sandviken, Pb 23, N-5812 Bergen, Norway. Rolf Gjestad, cand.psychol., University of Bergen, Department of Clinical Medicine, Psychiatry, Norway. Rune A. Kroken, M.D., Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psychiatry, Sandviken, Pb 23, N-5812 Bergen, Norway. Liv Mellesdal, M.Sc., Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psychiatry, Sandviken, Pb 23, N-5812 Bergen, Norway. Else-Marie L ø berg, assoc. professor, dr. psychol., Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psychiatry, Sandviken, Pb 23, N-5812 Bergen, Nor-way, and University of Bergen, Cognitive NeuroScience Group, Norway. Hugo A. J ø rgensen, M.D., Professor Emeritus, Ph.D., Haukeland University Hospital, Division of Psychiatry, Sandviken, Pb 23, N-5812 Bergen, Norway, and University of Bergen, Department of Clinical Medicine, Psychiatry, Norway.

Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B. A depression rating scale for 17. schizophrenics. Schizophrenia Res 1990;3:247 – 51. Karterud S, Pedersen G, Loevdahl H, Friis S. Global Assessment of 18. Functioning — Split Version (S-GAF): Background and scoring man-ual. Oslo: Ullevaal University Hospital, Department of Psychiatry; 1998. Guy W. EDDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology —19. Revisited (DHHS publ NO ADM 91-338). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1976. Holmen J, Midthjell K, Kr ü ger Ø , Langhammer A, Holmen TL, 20. Bratberg GH. The Nord-Tr ø ndelag Health Study 1995 – 97 (HUNT 2): Objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemi-ologi 2003;13:19 – 32. Alberti KGMM, Zimmet PZ. Defi nition, diagnosis and classifi cation 21. of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classifi cation of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15:539 – 53. Third report of the National Cholesterol Education program (NCEP) 22. expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Final report. Cir-culation 2002;106:3143 – 421. Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith Jr S, Lenfant C. Defi -23. nition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on Scientifi c Issues Related to Defi nition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:e13 – e18. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ô unpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. 24. Effect of potentially modifi able risk factors associated with myocar-dial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case – control study. Lancet 2004;364:937 – 52. Franklin SS, Larson MG, Khan SA, Wong ND, Leip EP, Kannel 25. WB, et al. Does the relation of blood pressure to coronary heart dis-ease risk change with aging? The Framingham Heart Study. Circula-tion 2001;103:1245 – 9. Weinehall L, Ö hgren B, Persson M, Stegmayr B, Boman K, 26. Hallmans G, et al. High remaining risk in poorly treated hyperten-sion: The ‘ rule of halves ’ still exists. J Hypertens 2002;20:2081 – 8. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, 27. et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: A statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Associa-tion Council on high blood pressure research. Circulation 2005;111:697 – 716. Netea RT, Lenders JWM, Smits P, Thien T. Infl uence of body and 28. arm position on blood pressure readings: An overview. J Hypertens 2003;21:237 – 41. Lund-Larsen PG. Blood pressure measured with a sphygmomanom-29. eter and with Dinamap under fi eld conditions — A comparison. Nor J Epidemiol 1997;7:235 – 41. Bovet P, Hungerbuhler P, Quilindo J, Grettve ML, Waeber B, Burn-30. and B. Systematic difference between blood pressure readings caused by cuff type. Hypertension 1994;24:786 – 92. Fodnesbergene G, editor. Smoking in Norway, 2008. Steady decline 31. in number of daily smokers. Statistics Norway 2009. http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/03/01/royk_en/. Accessed February 12, 2009. World Health Organization Regional Offi ce for Europe. Tobacco-32. free Europe. World Health Organization 2009. http://www.euro.who.int/tobaccofree/projects/20090209_3. Accessed March 06, 2009. Ramm J, editor. Mindre r ø yking, men mer overvekt. Statistics Nor-33. way 2009. http://www.ssb.no/vis/magasinet/slik_lever_vi/art-2004-01-22-01.html. Accessed February 12, 2009. Statistics Norway 2009. StatBank Norway. Health, social condi-34. tions, social services and crime. Health conditions. Survey of level of living, health conditions. Lifestyle habits, by sex and age (per-cent) (1998 – 2005). http://statbank.ssb.no//statistikkbanken/default_fr.asp?PLanguage � 1. Accessed February 12, 2009.

Nor

d J

Psyc

hiat

ry D

ownl

oade

d fr

om in

form

ahea

lthca

re.c

om b

y H

else

Ber

gen

- H

auke

land

uni

vers

itets

syke

hus

on 0

1/16

/15

For

pers

onal

use

onl

y.