CAPARRÓS, A., LINDMÄE, M, SAROJINI-PETES, C. (ed.) with illustrations made by CHAVES, A....

Transcript of CAPARRÓS, A., LINDMÄE, M, SAROJINI-PETES, C. (ed.) with illustrations made by CHAVES, A....

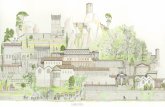

Once upon a time, in the distant land of southern Jutland, located

between the lush continental Europe to its south and the staggering

Scandinavia to its north, lay an old settlement by the name of Hamburg.

The origins of the culinary- named city go back to 808, when

Charlemagne, King of Franks sent a fleet-footed troop of soldiers to

build the castle of Hammaburg. This fortress was used to keep an eye on

the pirates and barbarians that continuously attempted to attack

through the northern part of the Elbe River.

The Elbe was easily navigable from its river mouth all the way up to

the very gates of Hamburg, reason for which people from all

neighbouring villages began to converge, bringing fishermen, traders

and sailors from afar.

Back in medieval times, a large portion of the coastal people’s diet

consisted of fish. Lübeck—a little, yet important town not far away

from Hamburg—had access to the salty waters that were home for herring

and other delicacies. But one thing held Lübeck back. With no

refrigeration or canning, the shipping of a highly perishable commodity

like fish was problematic. Now Hamburg, on the other side, played with

advantage as it had excellent access to the salt mines of Kiel through

the Jutland peninsula.This spice was the most precious resource man

could own, as it was the key to conserving fish and other edible goods.

It was therefore in the interest of the merchants of both towns to open

trade along the marketing of salt. This marked the beginning of the

celebrated League of Hanseatic cities.

The discovery of the Americas toward the end of the 15th century gave

further impetus to Hamburg’s port, as the city began to engage in close

economic ties to foreign countries. More and more ships began to sail

into the Elbe River, increasing the growth and wealth of the city with

each year that passed.

With the massive construction of factories in the 19th century, Hamburg

experienced a rapid growth of population, as nearby villages were

abandoned to find jobs in the city. By the 20th century, the city

already counted with one million residents and its port had become the

most important in the continent and the third largest in the world

after London and New York.

But not all was pretty skies and harmonious violins. Hamburg also

underwent some dark periods that cannot be ignored.

During the 1930s Hamburg became the infamous headquarter of the German

Nazi Party, for which the city suffered severe consequences, being

heavily bombed during the final years of the Second World War. The most

devastating attack was carried out by the Brits and the North Americans

in July 1943, with Operation Gomorrah, causing the immediate death of

approximately 40.000 people. By the end of the war, more than 70% of

the town was completely destroyed. The subsequent years to the war were

not easy for Hamburg. Although it remained part of West Germany, the

iron curtain was as close as 50 km from the border of the city. The

proximity of Soviet influences made matters worse, as it was an

obstacle for international trade. It wasn’t until France and England

easened the economic sanctions on Germany that the hamburgers were able

to return to a more prosperous living.

Today, Hamburg is one of Germany’s most important work locations. Most

job placements are in the business sector, followed by private and

public services, although the port is still of great importance, being

the second largest in Europe and a job provider for more than 170.000

people.

Parallel to the recovery of the city-state’s economy that is now

characterized for liberal capitalist principles, Hamburg also

experienced what these economic policies brought along: the decrease of

industrial production allowing the rise of the third sector. As a

result, the cityscape began to change, becoming an attraction for

investors and company headquarters.

As Hamburg became more visible to the eyes of Europe, it grew more

conscious of its aesthetic appearance, and began to polish up the city

and tidy up certain neighbourhoods that were not so easy on the eye.

GENTRIFICATION

...is the long word that social scientists nowadays use instead of the

milder notion of “urban regeneration”. Sanitation of marginal

neighbourhoods, conversion of old factory houses into fancy loft

apartments, public spaces owned by private entrepreneurs, construction

of sumptuous concert halls that gulp down half of the city’s budget —

this is what the inhabitants of Hamburg were and are facing until today.

Hafencity —the biggest inner-city urban development, located right on

the shores of the Elbe River— will occupy 160 hectares and the quarter

will eventually become home to numerous corporate headquarters; 5 500

apartments and hopes to create 20 000 new jobs. The new and pompous

Elbe Philharmonic Concert Hall’s budget was estimated at €40m when the

architect's design was first presented to the public in 2003, since

then it has hit €503m, with an additional €40m possibly needed over the

next two years. Hamburg's taxpayers are being asked to pay a whopping

€400m for the project.

Conflict and dissatisfaction arose when the city council decided to

renovate St Pauli’s riverbank area and its numerous abandoned buildings.

Although the project had been initiated with good intentions, St Pauli

was no place for fancy cafés nor lavish bars, where a sailor couldn’t

even afford a Bier. It was a somewhat a shabby neighbourhood that was

proud of its rich history of port trade that had brought together

fishermen, pirates and sailors from afar ever since old times. No plans

of constructing manicured looking buildings were going to succeed

amongst the working class habitants of the neighbourhood. St Pauli

decided to get out on the streets and speak up in the name of all the

neighbours. Elderly people, factory workers, transvestites and

promiscuous mistresses who earned their living on the Reeperbahn—all of

them were to preserve their access to the humble yet endearing streets

of St Pauli.

Nevertheless, such romance did not meet the interests of those who

ruled the city, and so the conflict began.

1981. The city began the renovation plan by reconstructing and

demolishing certain buildings in the Hafenstrasse (“Harbour street” in

German). The Reeperbahn and Hafenstrasse are the most infamous streets

that had initially sheltered sailors, craftsmen and travellers and,

becoming a central place for reunions amongst the alternative social

movements of Hamburg.

The local punks paid no attention to the regeneration project, as they

quietly began to occupy a block of houses owned by the City Council. In

a blink of an eye, more than 100 people started living in 13 houses

that were about to be demolished as part of the reconstruction project

in the riverbank area. Confrontations between the left wing squatters

and the police caused continuous riots and conflicts throughout the

following years.

1984: The Green Party financed the creation of an enormous mural on the

walls of one of the occupied buildings. On December 4th, political

prisoners of the RAF (Red Army Faction— a German armed resistance group)

and others began an indefinite hunger strike. On New Year’s Eve a Day

of Resistance was held at the Hafenstrasse followed by a solidarity-

demonstration to the local prisoners.

1985: With the growing atmosphere of tension, barricades were built

around the houses. A campaign against the Hafenstrasse was started by

the media in which they claimed members of the RAF were responsible

for the riots.

l986: 500 police officers occupied the Hafenstrasse area. For a whole

day the houses were under siege and close combat troops stormed in and

tried to destroy everything: six flats were evicted, household goods

were thrown out of windows, doors, toilets and electrical goods were

destroyed and tear gas was sprayed on cups and beds.

In response, 2000 people gathered to protest and show their indignation

by making their way to Hafenstrasse and confronting the police,

although the city council had closed off the neighbourhood, declaring

the area a prohibited zone. This movement spread to the rest of the

country as well as to Denmark and Holland, where people called for an

end to the police terror.

1987: The newly established "Radio Hafenstrasse" was on the air. It

became the most important media channel, informing listeners about

police movement and confrontations at all times.

Through the continuous demonstrations and wide public support the

Council was under heavy pressure. The mayor, Klaus von Dohnanyi finally

decided to remove the barricades and seek for a peaceful solution.

But the conflict continued.

1990 In May the area around the Hafenstrasse was declared a prohibited

zone, enforced by 3000 policemen.

1991: The public contract that secured squatters access to the houses

of Hafenstrasse was cancelled by the Court. Each and every occupant was

to be judged individually.

The Elbe shoreline –traditionally a working class area— continues to

provoke verbal conflicts between the public and private sphere.

Under this context emerged the popular football team of St Pauli. We

say popular because without winning a trophy in its hundred years of

existence and just 5 games in the state’s top league, Bundesliga, the

club has managed to gain over 11 million fans and 200 worldwide

supporters until today. Why? Well, they’re not just an ordinary

football team. Ever since they started in the 70s, the club openly

proclaimed its anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-sexist and anti-

homophobic values. It is known for its numerous female followers as

well as for having the first openly gay president.

In the 80s a small group known as the "Black Bloc"—occupants of

Hafenstrasse— began to gather behind the footballers’ benches during

the sport matches. They carried their own black flag with a white skull

that represented the pirate tradition of Hamburg as well as their

battles to conserve the buildings of Hafenstrasse. This flag has been

representing the fans of FC St Pauli ever since the first reunions.

Through football they defend human rights, civil solidarity,

cooperation and equality.

The original stadium of the club was completely destroyed during the II

WW.

In 1961 the construction of the new pitch began. Initially, the name of

the Stadium had been Millernot, but in 1970 it took the name of its

president, Wilhelm Koch, who thirty years later was detected of having

been a member of the Nazi Party. In discovering this, the club’s fans

forced the name to be changed back into Millerntor stadium, as we know

it nowadays. The stadium lies close the infamous Reeperbahn street,

known for its noisy bars and premises specialized on physical

satisfaction. Millerntor is a symbol of peaceful confrontation as well

as a place of festive celebrations.

The spirit of the club lies in its Fanladen —the fans— who not only

participate in cheering the team, but also in the decision making: each

member counts with one vote for every change to be made in the club’s

administration. They also manage the communication between the club’s

supporters, official leaders and members of the fanclub. It is

precisely this dense cooperation that makes FC St Pauli different from

other market-oriented football clubs.

St Pauli’s committee also offers expeditions to play in other cities,

special programs for the youth, reduced admission fees for the

unemployed and even a nursery within the stadium, where parents can

leave their kids during the matches.

A big part of the fans and members of Football club St Pauli still

represent a society distinguished from the rest, reduced to a marginal

neighbourhood that, like them, has had to find ways to survive through

the union and collaboration of its habitants.

It is thanks to this group spirit that we have grown to know St Pauli,

a small neighbourhood of Hamburg full of life and suffering, full of

everflowing tourism and time fixed communities. This identity has been

accomplished through a constant fight against those who were blinded by

economic and political interests. If today we know St Pauli it is

thanks to the youth that stood still and firm against oppressive

measures that did not take little geographies into account.