Cablegate in the Congo: Mapping the Digital Trail of Wikileaks Cables about the “Forgotten” DRC

Transcript of Cablegate in the Congo: Mapping the Digital Trail of Wikileaks Cables about the “Forgotten” DRC

Cablegate in the Congo:

Mapping the Digital Trail of Wikileaks Cables

about the “Forgotten” DRC

Lisa Lynch

On November 28, 2010, the transparency group Wikileaks began to release the most widely circulated documents in its brief history of leaking: a cache of diplo-matic cables downloaded from US intelligence networks by a disaffected soldier and made public through collaboration between Wikileaks and the New York Times, the Guardian, Der Spiegel, El País, and Le Monde. In the weeks following the first dis-closures made by these five partners, media outlets throughout Europe and North America inundated readers with reports on what was quickly termed “Cablegate,” republishing tantalizing selections from cables covering everything from Silvio Ber-lusconi’s deals with Vladimir Putin to corruption in Afghanistan.1 In the months to come, Wikileaks would go on to work with scores of additional, regional outlets, allowing for the distribution of cables in Latin America, Asia, and the Middle East.

As the cables traveled beyond the first waves of media partners, however, Cablegate was seen through a different lens. Wikileaks’ collaboration with Ameri-can and European media outlets has been celebrated by Western observers as an example of how a free press should operate in liberal democracies and as a dem-onstration that the new online tools that route around potential censorship have helped advance the rise of a “transparency movement” that will force greater gov-ernment accountability.2 But in countries ranging from Pakistan to Belarus, press

Radical History Review Issue 117 (Fall 2013) doi 10.1215/01636545-2210455© 2013 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc.

49

50 Radical History Review

restrictions or fear of reprisal thwarted efforts of journalists to access, let alone publish, cables containing sensitive information about their own governments. The notion that such a leak could foster any kind of “transparency” was thus seen as suspect — and in some cases, the cables themselves were seen as fabrications. If Cablegate was a “global” media event in 2010 – 11, it was one that revealed persistent tensions between access to information engendered by the worldwide penetration of new communications technologies and the local conditions that determine the circulation and reception of such information.

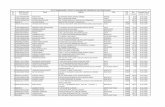

This article explores these tensions by focusing on the extent to which leaked diplomatic cables pertaining to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were discussed by media outlets and alternative online sources, both inside and outside the DRC. Before Cablegate, the Congo had already served as the source of revela-tory cable leaks; diplomatic cables obtained by an American journalist in the late 1970s through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request had revealed much about the United States’ involvement in the Congo during the 1960s, including alliances between the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and state officials in US attempts to remove Patrice Lumumba from power and to control the influence of the Soviets on Congolese politics.3 But while the DRC was a frequent topic of dis-cussion in Cablegate cables (over five thousand of the leaked cables referred to the country, half emanating from the embassy in Kinshasa), the leak proved under-whelming not only in terms of the drama of the disclosures but also in terms of the range and quality of reporting.

Telling the story of how Congolese Wikileaks cables circulated via print, broadcast, and (overwhelmingly) online media outlets, I hope to illuminate how information travels in a digital sphere that is at once local, regional, and global, at once constrained by conditions on the ground, and capable, on occasion, of circum-venting such conditions. My findings about the circulation of Congolese cables sup-port those who caution against overly general or overly optimistic assessments about the global effects of new media technologies and especially the equation between the online access to information and its unfettered circulation in a “global public sphere.” At the same time, these same circulation patterns suggest that it would be equally foolish to ignore the potential of online communications in the current Con-golese mediascape, even if that potential remains evanescent and largely untapped.4

To map out how Cablegate came to the Congo, I begin with a brief overview of the DRC’s current media, including its diasporic press. Then I explore how cable disclosures unfolded chronologically in the Congolese mediascape between late November 2010 and late September 2011, ending with cables discussed immediately before the November 2011 DRC elections in which incumbent Joseph Kabila and opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi both claimed victory. To locate such cover-age, the database of available Wikileaks cables was cross- checked against the DRC- focused cables covered by the group’s initial media partners, its regional partners,

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 51

the pan- African press, Congolese domestic and diasporic media, and Congo- focused blogs and aggregation sites. Since many of these media outlets are francophone, I have translated quotations and included the original French in endnotes.

Journalists as “Little Soldiers”: Congolese Media, War, and DiasporaSince 1996, the DRC has been involved in a series of conflicts — including a five- year war involving Rwanda and Uganda — that have resulted in more than 5 million direct and indirect Congolese casualties.5 The eastern Congo remains a site of active military engagement, and on both sides, the continued fighting has been funded by the expropriation of Congolese mineral resources. This has engendered, in turn, such a degree of illicit activity around Congolese mining that Transparency Inter-national has rated the country as one of the most corrupt countries on the planet.6 Ostensibly an electoral democracy, the DRC remains at heart an authoritarian state in which “patronage networks and authoritarian procedures, rather than democratic institutions based on the rule of law, characterize the regime.”7 Overseeing this state is Kabila, who gained control of the country after his father, Laurent Kabila, was assassinated in 2001. Though initially seen as a relatively benign force, Kabila has grown into a style of governance characteristic of many central African leaders (and of his father before him), maintaining the semblance of democratic institutions while keeping a firm grip on power and focusing on personal gain rather than the establishment of strong state institutions.

The persistence of the Congo as a weak authoritarian state has meant that the country’s infrastructure has been continually neglected. Few roads are paved, and inland waterways provide the most reliable means of transportation. Landline phones are practically nonexistent, and though mobile phones are available to a larger demographic (24 percent of the population), the lack of 3G networks in the country has made smartphone use difficult.8 Presently, most Internet connections are satellite- based; a recent Chinese investment in the Congo promises to broaden Internet access, but the country remains disconnected from a recently developed cable system that has resulted in faster and more reliable Internet access elsewhere in Africa.

Access to news in the DRC is compromised by this lack of effective infra-structure. Print newspapers are consumed primarily by an elite audience living in or around Kinshasa, the capital city, and few have a daily circulation of more than three thousand copies.9 The high price of paper (which is imported) and the lack of effective materials transport have meant that Congolese have traditionally gotten their news from broadcast sources. In Kinshasa, television news is paramount; view-ers watch state- sponsored news broadcasts from Radio Télévision Nationale Con-golaise (RTNC), obtain news from private television stations that are usually pro- government (including Digital Congo, a private pro- Kabila station), or view foreign channels including TV5 Monde and Euronews.

52 Radical History Review

Outside the capital, radio is the more accessible option, serving in the DRC, as elsewhere in Africa, as the primary information source. Leading domestic radio stations include Radio Okapi, run by the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO), the state- run La Voix du Congo, and the private sta-tions Raga FM and Top Congo FM. The dominant broadcast language for domestic stations is French, the country’s official language, though broadcasters sometimes air programs in Swahili, Lingala, and “Indoubil,” a patois that comprises Lingala, French, and elements from other local vernaculars.10 BBC World and Radio France International also broadcast in the DRC, though the latter has experienced signal interruptions due to government objections to content (one such blockage lasted from July 2009 to October 2010).11

These print and broadcast options are complemented by a limited though increasing number of domestically based online media outlets. Beginning in 2001, the official government press agency, Agence Congolaise de Presse, established a website, and the country’s major newspapers, including Le Phare, Le Potentiel, L’Obsevateur, and L’Avenir, followed suit with sites that repurposed the content of their print publications. More recently, online- only news sites such as the aggrega-tion site Direct.cd have also emerged. At present, online media outlets, hobbled by the paucity of Internet access, have even less domestic distribution than print ones. But the importance of the Internet has been growing, particularly among educated, politically engaged Congolese. Though direct Internet access remains at about 1 percent of the population, by December 2011 there were more than 915,000 Internet users in the Congo, for the most part reliant on Internet cafés to deliver service.12 One reason for the increased interest in online media is that for the exchange of ideas it remains a potentially freer space than print or broadcast media: partly because the Internet is still a weak force for communication in the Congo, the government does not actively monitor online content as much as it does print and broadcast content.13 As well, the country does not filter incoming Internet content, making Western online media readily available to (and frequently accessed by) Con-golese media outlets.

This relatively hands- off approach to the Internet is significant, because — though freedom of expression is constitutionally protected in the DRC — media out-lets operate in an environment in which press freedom is severely curtailed. In the Congo, as elsewhere in Africa, the news media are seen as an important tool of polit-ical communication and are thus subject to strong press restrictions.14 As Congolese advocacy group Journalists en Danger (JED) notes in a 2011 report, crackdowns on the press in the Congo have typically “ebbed and increased with domestic political tensions,” but recent years have seen an increase in press harassment.15 According to JED, such harassment has led journalists to constrain their reporting or to promote causes for personal gain, allowing the watchdog function of journalism to be sup-planted by cronyism and direct profit (via a payoff system known as coupage). This

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 53

has been especially true for broadcast media, which has often become a mouthpiece for politicians and interest groups that will pay for airtime.16 As JED notes in its report on media coverage of the 2011 elections, journalists have become “little sol-diers” who take their orders from the wealthy and powerful.17

What this means is that though the Congolese media is still occasionally a mechanism for expressing civic dissent, such dissent is often selective and can incur great personal and professional cost.18 For example, the recent importance within the Congo of radio and television call- in programs (émission d’un téléphone ouvert) in which Congolese voice concerns about infrastructure issues, poor policing, or other civic concerns can be seen as a step toward a more politically engaged media; at the same time, one well- known presenter was forced out of the country after his show became too overtly political, only to be invited back by Kabila himself with the stipulation that his program be more respectful.19 More recently, the government has forbidden Congolese media — including call- in shows — to discuss the ongoing conflict in the eastern Congo.20

Despite Kabila’s effectiveness at subduing the domestic Congolese press, the emigration of Congolese to other countries has resulted in the emergence of an oppositional Congolese media located outside the DRC itself. Since the mid- 1990s, a substantial number of Congolese have emigrated to countries inside and outside Africa, principally the Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia, Belgium, France, and Germany.21 Like similar diaspora communities in Africa and elsewhere, Congolese migrants have turned to the Internet as a means to circulate news and opinion, creating media outlets and online forums based abroad but focusing on Congolese affairs.22 These sites feature news and opinion pieces that not only would be excluded from domestic Congolese media sources but would likely be seen as too insignificant to merit attention from Western media outlets. They are read both by Congolese abroad and by those in the Congo with Internet access. Most often they are collaborative and anonymous efforts, but some — like Alex Engwete, the epony-mous blog of a journalist who divides his time between the Congo and the United States — are the work of individual authors.

Predictably, examples of such diasporic outlets can be found in places where the Congolese diaspora has achieved critical mass. Belgium, the former colonial ruler of the DRC and the current home to a substantial Congolese population, is home to the Congo Forum, the Congo Indépendent, and JamboNews (covering central Africa’s entire Great Lakes region), while Le Congo Hebdo is published in South Africa, Congo Vision in the United States, and Mwinda in France. But other publications, including the Ireland- based KongoTimes!, support the idea that the online space allows Congolese to build virtual community in the face of relative isolation from their countrymen and women. Congolese in the diaspora may be spread around the globe, but their online access allows them to connect both with the larger expatriate community and with news sources emanating from the DRC

54 Radical History Review

itself, sometimes connecting more effectively than those living inside the country. Given the scarcity of Internet access for domestic Congolese, this online diaspora community also forms a significant audience base for the online editions of domestic media outlets.23

Beyond the Congolese domestic and diaspora press, the DRC is served by a number of international media outlets (print and online) with broad coverage of African issues, including AllAfrica, based in the United States and Africa, and Jeune Afrique, based in Paris. Finally, a number of foreign Congo experts regularly blog about the Congo; these include Congo Siasa, written by American political scientist Jason Stearns, and Congo Masquerade, written by Belgian political scientist Theo-dore Trefon.

In sum, the Congolese mediascape consists of a number of different arenas: a highly controlled broadcast space with some incursions from foreign broadcasters; a highly controlled print space with limited circulation; an emergent online domestic space that, although still frequently self- censored, has the potential to evade some press restrictions; a pan- African and online diasporic media that is less constrained and accessible to those inside and outside the DRC; and an “expert” blogosphere authored by non- Congolese yet read by Congolese and members of the diaspora. As the discussion below will demonstrate, each of these arenas responded differently to Cablegate. Congo leaks scarcely registered in the broadcast arena, were taken up cautiously by newspapers in the print and online space, and were discussed heatedly in the diasporic and pan- African press, where the cables were used as a means to criticize Kabila and other political figures in the DRC.

Diplomats, Spies, and Uranium: Western Media on CablegateDespite such differences in approach, one thing most observers interested in the Congo cables shared was a common lack of access to the cables themselves for the better part of a year. The DRC serves as an example of countries left out of the loop by Wikileaks’ plan to coordinate with first international and then regional media outlets for the distribution of leaked cables. Elsewhere in the world, Wikileaks exploited regional media partnerships to great advantage, at times — particularly in North Africa and Latin America — producing significant local effects through cable disclosures.24 But it was unable, for the most part, to successfully partner with outlets in countries with severe press restrictions, which meant that they were largely shut out of Africa.25 Thus while a selection of cables relating to Africa went both to South Africa (where Wikileaks partnered with an online media outlet called News24) and to Kenya (where Wikileaks established a relationship with the Nation and the Star), Congolese journalists received no cables about their country. This gap in distribution meant that until September 2011, when the cable database was released in its entirety, Congolese domestic and diaspora media interested in the Congo cables had to rely (with several exceptions) on the news stories written by

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 55

Wikileaks’ initial partners.26 Their wait for such stories proved frustrating, as the cables deemed newsworthy by these publications were largely those of interest to their European and American audiences.27

Though disappointing, the paucity of reporting on the Congo cables was characteristic of an overall lack of Western media interest in the DRC’s political landscape.28 Compared to other war- torn regions in Africa (Rwanda, most notably), the Congo has gotten far less media attention, leading the country’s recent conflict to be labeled the “forgotten war.”29 When Western outlets have covered the DRC, most often it has been in moments when Congolese affairs have implications for Western media audiences; even then, journalists have tended to repeat common themes — such as the mining of so- called conflict minerals and the high incidence of sexual violence as a tool during wartime — instead of analyzing the underlying causes of the region’s troubles.30

In line with this lack of engagement, the first mention of the Congo by Wikileaks’ initial media partners came as little more than an aside in a Guardian story about State Department intelligence gathering. On November 28, 2011, the Guardian described a cable featuring an intelligence directive from US secretary of state Hillary Rodham Clinton (09STATE80163) that asked State Department offi-cials to covertly collect “biometric data” (including fingerprints and DNA samples) from UN leaders.31 Following the coverage in the Guardian, the legality of Clin-ton’s directive was debated by media outlets in countries including India, Pakistan, Israel, Russia, Mexico, Peru, Italy, and France, while in the United States the cables prompted a discussion of whether Clinton should resign.32

The Guardian article also drew attention in the African and African dias-pora press, but not because of suggestions that State Department officers were spying at the UN. Instead, journalists in African publications focused on a second cable (09STATE37561) that merited only a brief mention in the Guardian article. This cable, the Guardian noted, asked that State Department officials collect simi-lar information from political and religious leaders in Africa’s Great Lakes region, including leaders in Rwanda and the DRC. The cable was included in the Guardian database without an accompanying article, its relatively sparse coverage suggesting that if spying at the UN was deemed to be of interest to Guardian readers, spying in central Africa was considered less newsworthy. This was hardly the case in Africa: by the following day, the directive had been read and analyzed by media outlets across the continent, including Ethiopian Review, Jeune Afrique, the Rwanda News Agency, AllAfrica, and the Congolese newspapers Le Potentiel and L’Avenir, pro-voking a discussion in these outlets about the role of US diplomats in the Great Lakes region.33

A few weeks later, the Guardian devoted more space to discussion of a Congo cable; in this instance, the coverage assessed whether insecure conditions in the DRC might pose a threat to the West. On December 19, the newspaper reported

56 Radical History Review

on State Department fears that the deterioration of infrastructure in the Congo had made uranium stores accessible to potential terrorists, thus leading to what CNN and other US outlets subsequently described as a “loose nukes” scenario.34 Cables dat-ing from 2006 and 2007 (07KAMPALA1752, 06DARESSALAAM1593) described illicit trade in Congolese uranium, while a 2008 cable (08KINSHASA247) noted that lax security conditions at the Kinshasa Nuclear Research Center might make the site vulnerable to theft.35 In a rare example of two of Wikileaks’ initial media partners simultaneously drawing attention to the same leaked material, an article on cables about uranium also appeared in El País. The El País article mentioned possible uranium smuggling and the insecure conditions at the Kinshasa research center but added discussion of a cable (07KINSHASA797) claiming that Malta For-rest, a Belgium- based mining company, was mining and exporting uranium from the Congo under the pretense of exporting only cobalt and copper.36

Within days, the Guardian story and the El País story were picked up by both African and international media outlets. These articles, however, tended to focus less on the idea of nuclear terrorism than on conditions on the ground in the Congo and the accuracy of depictions of DRC nuclear sites. The pan- African news site Le Griot accepted the Guardian’s assessment of conditions at the facility, assert-ing that it was a “paradox” that the DRC maintained nuclear ambitions in the face of such evidence of its negligence.37 But Jeune Afrique, another pan- African outlet, treated the Guardian’s article more skeptically, ending its report with interviews with DRC officials who claimed that the conditions at the Kinshasa nuclear facility had improved in the past few years.38 The El País article was similarly questioned by Le Soir, Belgium’s leading francophone newspaper. A post on the BEkileaks (Bel-gium leaks) blog on the newspaper’s website dismissed the allegations about Malta Forrest, noting that “the Great Lakes Region is far more dangerous for the free cir-culations of such rumors than for the possible smuggling of radioactive resources.”39 The Belgian- based diaspora site Congo Independent, however, faulted El País for not going far enough, arguing that while the cable “scratched” at Malta Forrest, it failed to draw attention to financial connections between the mining company and Kabila himself.40

This additional coverage of the “loose nukes” cables reveals two key aspects of secondary media coverage of Cablegate (i.e., coverage based on cables published by other media outlets). First, the contested interpretations of the nuclear cables dem-onstrated that the evidentiary status that the cables seemed to have for Wikileaks’ initial media partners — as documents revealing truths not only about US diplo-mats’ actions but also about the countries in which these diplomats resided — was often challenged by other media outlets, especially those without direct access to the cables. Second, if it was the case that cable stories authored by the initial media partners circulated primarily in countries implicated in these cables, the same was true of the secondary coverage. In that regard, the prompt attention to the El País

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 57

story in the francophone Belgian media indicated that economic and social ties between Belgium and the Congo persisted more than a half century after the Congo emerged from colonial rule. Due to Belgian investment in the Congo and the con-tinued growth of the Belgian Congolese diaspora, Belgian media is routinely read by Congolese political elites, and discussion of Congolese political and economic topics appear more frequently in Belgian newspapers than elsewhere in Europe.41

This connection between the Congo and Belgium meant that the Congo cables were discussed in Belgian newspapers even after interest in the Congo cables had faded among Wikileaks’ initial media partners. In February 2011, the Belgian newspaper Der Standaard wrote about a 2009 cable (09KINSHASA191) describing Kabila’s attempts to oust rival Vital Kamerhe from Parliament by bribing officials.42 The cable, highly critical of Kabila’s actions, was subsequently picked up by the Belgian newsmagazine Le Vif, which interviewed a “shocked” Kamerhe about the claims.43 Criticism of Kabila based on the cable also appeared in the pan- African media outlets Jeune Afrique, Africa News, and the Cameroon Voice.44 Publishing inside the DRC, however, the Congolese daily L’Avenir avoided criticism of Kabila. In an article titled “Kamerhe Is Not Credible,” it focused instead on portions of the cable critical of Kamerhe.45

“Fucking Internet!” Wikileaks, African Media, and the “Balkanization Conspiracy”L’Avenir’s treatment of the Kamerhe cable was representative of a general tendency in coverage of the Congo cables: cables directly critical of Kabila were described as such in the international and pan- Africa press, while the domestic press, if mention-ing such cables at all, found a way to describe their content that did not reflect badly on the DRC’s leader. This tendency was similarly evident in March 2011, when the first African “exclusives” on Cablegate began to appear following partnership arrangements between Wikileaks, the Nation, and the Star. The East African, a Kenyan newspaper that likely had an informal sharing agreement with the Nation or the Star, published articles on several cables concerning Nigerian president Oluse-gun Obasanjo. In a cable (09USUNNEWYORK652) written in 2009, shortly after the end of the Second Congo War, Obasanjo voiced concerns about the leadership abilities of Congolese president Kabila and suggested that the Congo might need to be further divided to ensure peace.46 In the pan- African press and in Congo-lese diaspora media — including JamboNews and the Congo Diaspora Forum — Obasanjo’s remarks were cited as evidence of Kabila’s incompetence.47 Yet an article in the domestic newspaper Le Phare interpreted the cable differently, citing it as evidence that both the United States and Congo’s African neighbors were strategi-cally interested in dividing the DRC.48

Discussing the cables in terms of a commonly perceived threat to the DRC’s national integrity, Le Phare managed to write about a cable critical of Kabila in an article that shifted focus to an issue that has become central to Congolese identity:

58 Radical History Review

the national struggle against “balkanization,” or the further division of the country along ethnic lines. As the Congo has struggled to maintain peace with its neighbors and peace within its borders, the belief that the Congo ought to remain undivided has been, paradoxically, one of the strongest ties binding a nation with deep politi-cal and ethnic divisions.49 This belief is continually reinforced through the claim that outside forces are pressing for the balkanization of the Congo. Inside the DRC, one of the chief voices of antibalkanization sentiment is Le Potentiel. The news-paper declares “Non a la balkanization de la RDC!” (“No to the Balkanization of the DRC!”) at the top of its masthead and frequently writes about possible balkanization plots, ascribing them most frequently to the United States or “the West” but also to Rwanda, the UN, and nongovernmental organizations including the Red Cross. Outside the country, diasporic media outlets are equally obsessed with the question of balkanization, though they occasionally invoke different figures (including Kabila) as players in the plan to split the Congo.

The possibility that cables might provide evidence of a balkanization plot was floated by Congolese observers soon after the first cables were released. In Decem-ber 2010, Julien Paluku, the governor of the eastern Congolese district of North Kivu, published an editorial on Beni- Lubero Online asserting that the absence of Wikileaks cables regarding balkanization was linked to Western government censor-ship of the Wikileaks releases: “As the secrets published by the aforementioned five newspapers have been cleared by their respective governments, it could be that all governments involved in the plan of the balkanization of the DRC have not autho-rized the disclosure of these secrets.”50 Paluku’s suspicion that Wikileaks’ media partners needed government consent to publish leaked information challenges the notion that Cablegate served as an indicator of the continued vitality of “free press.” Coming from a country in which press freedom was more a facade than a reality, Paluku assumed that countries in the West faced the same strictures, despite their claiming otherwise. A similar skepticism was voiced by the French- based diaspora outlet Mwinda about the lack of Congo cables in Le Monde; Mwinda did not suggest that the government had censored the outlet but instead speculated that Le Monde had held back the Congo cables due to the business interests of one of that news-paper’s central shareholders.51

In February, after two months of scant disclosures, Le Phare published two editorials about Wikileaks’ lack of Congo coverage, also wondering whether Wikileaks suppressed evidence of balkanization. The first editorial (February 9) questioned what motives guided Wikileaks’ choice to hold back the cables from pub-lication, asking why Wikileaks was “so ready to unpack ‘monsters’ such as the FBI [Federal Bureau of Investigation] and the CIA or leaders of major world powers” but unwilling to give the Congolese information about balkanization.52 The second editorial (February 16) called the cables a “Pandora’s box,” noting that despite the lack of coverage from Wikileaks’ media partners, Congolese were “convinced that

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 59

Wikileaks hides many cables about their country” and “continue to expect from this site [elements of the response to the insecurity in the north and east] but also in terms of the balkanization of their land.”53

Those who hoped for specific mention of the balkanization of the DRC dur-ing Cablegate had their wish granted in the late summer of 2011, when Wikileaks made the entire cable database available on its website. Almost as soon as cables became accessible online, blogger Alex Engwete identified a cable dating from 2010 (10KINSHASA260) devoted to the balkanization issue. Far from being evidence of a US plan to divide the Congo, however, the cable was instead an expression of concern about what it labeled the “conspiracy theory that foreign interests seek to divide the DRC into smaller client states in order to facilitate access to the country’s vast mineral reserves.”54 Engwete published the cable in English and in French on his blog, responding to its concerns with a mix of incredulity and amusement. Gesturing to the history of United States – Congo relations, he suggested that the cable reflected the inability of US diplomats to understand the real- world conditions prompting “conspiracy” thinking:

The cable provides fascinating reading — with one caveat: it should be clarified to the US Kinshasa embassy that what it calls “conspiracy theory” is “broad- based” and deeply held as indisputable truth by virtually all the Congolese. What’s more, this belief is reinforced by insensitive remarks that some American officials make now and then about the Congo, such as the infamous comment by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton during her visit in the DRC advising the Congolese on the need to forget about the past and to move on!55

Within days, Engwete’s discovery of the cable drew the attention of Le Potentiel, which chose to run a description of the cable accompanied by both Engwete’s French translation of its contents and an editorial cartoon drawn by the newspaper’s cartoonist. The cartoon featured a State Department officer slump-ing at his desk, apparently in despair because he realizes that the Congolese have learned from reading online news sources that the United States is trying to divide their country. The caption reads: “They’re definitely not stupid! They understood everything! Fucking Internet!”56 The balkanization cable was also discussed on Télé 7, the television station owned by Le Potentiel, thus becoming perhaps the only Cablegate leak to reach a broad audience in the Congo through exposure in domestic broad cast media.57

More than any other reporting stemming from the Congo cables, the bal-kanization coverage provided by Engwete, Le Potentiel, and other outlets seemed to reflect a rare moment of consensus in a deeply factionalized DRC mediascape. While other cables were interpreted differently in the domestic and diasporic media space, there seemed little disagreement about how to interpret the “conspiracy” cable: namely, as a document meaning exactly the opposite of what it appeared to

60 Radical History Review

mean. This inversion of meaning further demonstrates how Cablegate was some-times viewed skeptically by those far removed from Wikileaks and the cables’ origi-nal publication contexts. Le Potentiel, which described Wikileaks only as a “Twitter site” in its coverage, refused to accept the evidentiary status of the diplomatic cables, choosing instead an interpretation that fed into a preexisting belief about United States – Congo relations.

Kabila as “Weak Leader”: Wikileaks Cables and the Congolese ElectionsIf the skeptical accounts of the “balkanization” cable reflected a shared belief among Congolese about the US role in Congo politics, discussion of other cables that emerged in August and September 2011 pointed to the sharp divisions that characterized Congolese political life. As bloggers and journalists pored through the Congo cables now freely accessible online, they seized on those that described the foibles of Congolese political figures. The emergence of these cables during the lead- up period to Congolese elections meant that the cables became, to some degree, part of the conversation about whether Kabila should continue as president and whether his rivals were themselves worthy of office.

Much of this conversation took place not in the Congo itself but in the pan- African and diasporic press. In advance of the November 2011 elections, Kabila imposed still further restrictions on the domestic press, creating a press commission that effectively shut down opposition media. As well, Kabila loyalists began harass-ing and attacking journalists.58 One news outlet that came under attack, the news aggregation site Direct.cd, published critical articles about the government and mil-itary, including articles that explored some of the more damaging Wikileaks cables concerning Kabila. In November 2011, the newspaper’s editor, Benjamin Listani Shura, had his equipment seized and received a death threat. Given this climate, it was perhaps to be expected that, for the most part, critical cables about Kabila were thus either disregarded by Congolese newspapers or mentioned obliquely.

One preelection cable (09Kinshasa453) that received attention outside the DRC touched on what US officials thought was the disproportionate influence of Augustin Katumba Mwanke, who was a powerful advisor to Kabila and had been influential in securing mining contracts and negotiating Chinese investment in Con-golese infrastructure. Though Mwanke had been dismissed from a formal post after he was accused of financial mismanagement by UN experts, his political influence persisted.59 For the most part, articles about the Mwanke cable focused on corrup-tion in the Kabila regime and thus appeared in media outlets outside the Congo. The diaspora site KongoTimes! highlighted the cable’s mention of Mwanke as the “single point of access” to Kabila, while Jeune Afrique wrote about Mwanke in an article that used the cables to portray Kabila as ineffective, drawing attention as well to a 2009 cable in which then ambassador William Garvelink described Kabila as a “weak leader” (10KINSHASA133).60

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 61

The cables released by Wikileaks levied most of their criticism at Kabila, but other Congolese presidential candidates were implicated by Cablegate as well. Kamerhe, the advisor criticized as lacking credibility in the cable published by Der Standaard in February 2011, was also a candidate for office, as was Léon Kengo, who a cable described as fishing for US political support. Eighty cables referred to the Congolese opposition leader, Tshisekedi; one in particular (04KINSHASA1999) noted that he discussed political strategy privately with US embassy staff. Engwete predicted on his blog that the idea that Tshisekedi had taken US diplomats into confidence might cause “a hoo- ha in the tense pre- electoral atmosphere prevailing now in the DRC.”61

Though the cables were seen outside the Congo as evidence of the foibles of current or potential leaders, within the Congo itself they were seen as evidence of possible election interference. Le Phare speculated that Wikileaks might have deliberately timed the release to influence the November presidential elections. “The big question that crosses many minds,” Le Phare asked, “is why Wikileaks wishes to throw stones into the pool, when Congolese presidential candidates are working to present the best possible image of themselves.” Le Phare also equivo-cated about the accuracy of the claims in the cables, noting that it was difficult to “know where the truth lies” but adding that “the wealth of information should give voters a good idea of where to turn.”62

Though the Le Phare article and Engwete’s blog post both suggest that the Wikileaks cables might shape election outcomes, Le Phare is overstating the case in imagining that Wikileaks’ “stones” produced more than the barest of ripples: any discussion of Cablegate during the elections was constrained by both the restric-tions placed on the press and the limited circulation of online media within the Congo itself. And even if cables did cost Kabila votes in the 2011 election, the results of the election may have ultimately had little to do with a democratic vote. After Kabila’s primary opponent, Tshisekedi, gained the majority of votes, the Supreme Court of the DRC handed power back to Kabila.

Conclusion: Cablegate in the CongoShortly after the first disclosures of Cablegate, a Ugandan journalist used a Congo-lese analogy to explain the significance of the leaks to European politicians and citi-zens. He asked readers to imagine “waking up one morning and all the newspapers, FM stations and television channels are reporting on what exactly went on during the second Congo war that began in 1998 and ended in 2003.”63 While the journal-ist was describing what he imagined to be an impossible situation (as much of the political and economic dimensions of that conflict remain shrouded in mystery), his comments hinted at the hopes of some observers that the cables might unpack some of the Congo’s persistent secrets.

In the end, such hopes went unrealized. The Congo’s secrets remained

62 Radical History Review

mostly intact, and the results of Cablegate were mixed at best. Inside the coun-try, the Cablegate disclosures had little effect. Cablegate was viewed with suspi-cion by the domestic press, and the leaks remained essentially a nonissue for the majority of citizens with access only to broadcast media, while those with access to news papers saw coverage that touched on “safe” topics and steered clear of cables critical of Kabila. The only leak that prompted sustained public discussion was the 2010 “balkanization” cable, which was used to draw attention to the United States’ interference in Congolese affairs. A stronger case could be made, however, for the effect of the leaks outside the Congo’s borders; pan- African and diasporic media kept the focus on the cable’s criticisms of Kabila and his cabinet, and this focus, in turn, helped fuel the diaspora’s growing anger with conditions in their homeland. In the months following the contested elections, thousands of Congolese took to the streets in London, South Africa, Italy, France, Belgium, the United States, Aus-tralia, and Canada. Using social media to publicize and document their protests, they forged a narrative of a globally connected, empowered Congolese community working for change from abroad.64 Thus if the cables could hardly have been said to fuel a “Congo Spring” within the country’s borders, they can be seen as a catalyst for mobilizing those on the outside who consider themselves as speaking on behalf of silenced Congolese.

Beyond whatever effects the cables may have produced, their circulation inside and outside the DRC also illustrates how online news flows operate at a moment in which Internet penetration inside the Congo is scant but increasing. Discussion of the Wikileaks Congo cables took place primarily in the world of newer media: in the nascent Congolese blogosphere, the online Congolese diasporic press, and a Congolese domestic press making forays into the online space. And within this online space, individuals and media outlets were impressively networked. In searching for information about relevant cables, journalists sourced stories from one another, from the regional press, and even from individual bloggers. This cross- pollination in the Congolese mediascape suggests that certain kinds of information blocked from broader distribution are now readily available to a growing population of Internet users inside the Congo, including those in the domestic media. This broader access, coupled with the ever- increasing online coordination of the Congo-lese diaspora, may mean that the effect of future “Cablegates” might be greater than in the present case.

Such optimism, however, needs to be tempered with patience and caution. As observers of the Arab Spring have noted, the recent uptick in the use of online communications tools in social movements may seem like something of a snowball effect, but in reality it is an indication that long- standing online civil society move-ments are beginning to bear fruit.65 The difficulty of online access means that the DRC is far from having such online movements. And as the potential of online tools has become all too obvious to governments interested in keeping control over their

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 63

populations, it would be naive to imagine that such a society will form in due course, just as it would be naive to assume that governments that now confine press restric-tions to off- line media will not look more closely at all forms of online communica-tion. Mapping the digital trail of the Congolese cables thus reveals how pitted and precarious this trail remains for those who hope that the gradual digital transforma-tion of the Congo might prove empowering for Congolese citizens. Yet the process of mapping also suggests that unseen pathways might be on the horizon, as shifts in politics, economic relations, and communications technology in the Congo reshape the ways in which Congolese can negotiate their own national destiny and their rela-tion with the world at large.

Notes1. Examples of early Cablegate reporting include Rob Evens, Luke Harding, and John Hooper,

“Berlusconi Profited from Secret Deals with Putin,” Guardian, December 2, 2010.2. For a discussion of Wikileaks in the context of press freedom, see Yochai Benkler, “A Free

Irresponsible Press: Wikileaks and the Battle over the Soul of the Networked Fourth Estate,” Harvard Civil Liberties Law Review 46, no. 2 (2011): 311 – 97. For a discussion of the group’s ability to route around censorship restrictions and bolster the “global transparency movement,” see Micah Sifry, WikiLeaks and the Age of Transparency (New York: OR Books, 2011).

3. Madeleine G. Kalb, The Congo Cables: The Cold War in Africa — from Eisenhower to Kennedy (New York: Macmillan, 1982).

4. Since the first wave of optimistic scholarship on the transformative potential of the Internet, many scholars have had second thoughts. To cite a few examples, in The Myth of Media Globalization (Cambridge: Polity, 2007), Kai Hafez warns that what we imagine to be a global civil society emerging from online communications is really limited interaction among cosmopolitans. Eva Anzaldua, Michael Jensen, and Laia Jorba point out that what scholars have described as the “Internet Effect” is not consistent across all countries. Eva Anzaldua, Michael Jensen, and Laia Jorba, eds., Digital Media and Political Engagement Worldwide: A Comparative Study (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 242. Evgeny Morozov details the efforts of repressive governments to use the Internet as a tool of surveillance and control. Evgeny Morozov, The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom (New York: Public Affairs, 2011).

5. For a discussion of the political situation in present- day Congo, see Jason Stearns, Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa (New York: Public Affairs, 2011).

6. Stacey Burnett, “Country Profile: Democratic Republic of Congo,” Transparency International, 2011, www.transparency.org/country#COD.

7. Stephanie A. Matti, “The Democratic Republic of the Congo? Corruption, Patronage, and Competitive Authoritarianism in the DRC,” Africa Today 56, no. 4 (2010): 44.

8. Paul Budde, “DRC: Telecoms, Mobile, and Internet,” BuddeComm, March 29, 2012, www .budde.com.au/Research/Democratic- Republic- of- Congo- Telecoms- Mobile- and- Broadband .html.

9. For more on Congo media circulation, see Jason Stearns, “Sources for News on the Congo,” Congo Siasa (blog), October 4, 2011, congosiasa.blogspot.ca/2011/10/sources- for- news- on - congo.html.

64 Radical History Review

10. Marie- Soleil Frère, The Media and Conflicts in Central Africa (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2007).

11. “Democratic Republic of Congo Profile,” BBC News, October 23, 2012, www.bbc.co.uk /news/world- africa- 13283212. It should be noted that at the time my article went to press, Radio Okapi had also been blocked by the DRC.

12. Ibid. As well, much online content in the DRC is hosted on foreign servers, making sites less vulnerable to shutdown (though not to blockages).

13. “Freedom of the Press 2011: Congo, Democratic Republic of (Kinshasa),” Freedom House, www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom- press/2011/congo- democratic- republic- kinshasa (accessed May 16, 2013).

14. For a broader discussion of African media systems, see Adrian Hadland, “Africanizing Three Models of Media and Politics,” in Comparing Media Systems beyond the Western World, ed. Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 96 – 118.

15. The regime of Mobutu Sese Soko exercised strict control of the Congolese media until 1990, when the regime was pressured into a series of reforms. The result was a brief flowering of the Congolese press; dozens of new media outlets emerged, and many — including Le Potentiel, still the country’s leading newspaper — were openly critical of the regime. Over time, however, such criticism was met with government reprisals, first from the Mobutu regime, then under Laurent and then Joseph Kabila. See Steph Matti, “Corruption Patronage, and Competitive Authoritarianism in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” ebookbrowse.com/corruption- patronage- and- competitive- authoritarianism- in- the - democratic- republic- of- the- congo- pdf- d1442832 (accessed May 16, 2013).

16. Marie- Soleil Frère, “Popular TV Programs and Audiences in Kinshasa,” in Popular Media, Democracy, and Development in Africa, ed. Herman Wasserman (New York: Routledge, 2011), 188 – 206.

17. Donat M’Baya Tshimanga, La liberté de la presse pendant les élections: Des médias en campagne (Freedom of the Press during the Elections: The Campaign in the Media) (Kinshasa, DRC: JED, November 2011), 6. The original reads: “Derrière les journalistes corrompus se cache une élite politique prête à tout, et surtout à continuer à faire tourner une machine destructrice qui leur assure gloire et argent. Les journalistes là- dedans sont de petits soldats.”

18. See Mvemba Phezo Dizolele, “The Mirage of Democracy in the DRC,” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 3 (2010): 143 – 57. Press freedom in the Congo was actually the subject of a number of US diplomatic cables concerning the DRC. In one 2009 cable, then ambassador to the Congo William Garvelink notes that “the media environment in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is unusually problematic and complicated, even by African standards.” See 09KINSHASA 1090, www.cablegatesearch.net/cable .php?id=09KINSHASA1090.

19. Katrien Pype, “Taboos and Rebels — or, Transgression and Regulation in the Work and Lives of Kinshasa’s Television Journalists,” Popular Communication 9, no. 2 (2011): 114 – 25.

20. “Attacks on the Press 2011: Democratic Republic of Congo,” Committee to Protect Journalists, http://cpj.org/attacks_on_the_press_2011.pdf, 325 (accessed February 2012).

21. There is a fair amount of uncertainty about the exact size of the Congolese diaspora. See Dilip Ratha and Sonia Plaza, “Harnessing Diasporas: Africa Can Tap Some of its Millions of Emigrants to Help Development Efforts,” Finance and Development 48, no. 3 (2011): 48 – 51.

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 65

22. See Andoni Alonso and Pedro J. Oiarzabal, Diasporas in the New Media Age: Identity, Politics, and Community (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2010); Karim Karim, The Media of Diaspora: Mapping the Globe (New York: Routledge, 2003); and Anne Biersteker, “Horn of Africa and Kenya Diaspora Websites as Alternative Media Sources,” in Media and Identity in Africa, ed. Kimani Ngoju and John Middleton (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), 151 – 59.

23. For more on the relationship between domestic publishing and the diaspora, see Lilian N. Ndangam, “Free Lunch? Cameroon’s Diaspora and Online News Publishing,” New Media and Society 10, no. 4 (2008): 585 – 99.

24. It is difficult to say how many “official” regional partnerships Wikileaks established, as some media outlets that have been labeled partners have ended a formal relationship with Wikileaks. For a more detailed description of these partnerships, see Lisa Lynch, “The Leak Heard Round the World,” in Beyond WikiLeaks: Implications for the Future of Communications, Journalism, and Society, ed. Benedetta Brevini, Arne Hintz, and Patrick McCurdy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 56 – 77. For a discussion of the effects of Cablegate, see, e.g., Peter Kornbluh, “WikiLeaks: The Latin America Files,” Nation, July 25, 2012, www.thenation.com/article/169079/wikileaks- latin- america- files; or Peter Walker, “Amnesty International Hails WikiLeaks and Guardian as Arab Spring ‘Catalysts,’ ” Guardian, May 13, 2011, www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/may/13/amnesty- international - wikileaks- arab- spring.

25. Okoth Fred Mudhai, “Immediacy and Openness in a Digital Africa: Networked- Convergent Journalisms in Kenya,” Journalism 13, no. 2 (2012): 674 – 91.

26. An encrypted file containing the full cache of unredacted cables was found online and publicized by the German newspaper Der Freitag, reportedly placed there by former Wikileaks staff member Daniel Domscheit- Berg. Following this incident, the temporary password given to Guardian reporter David Leigh by Wikileaks founder Julian Assange was used to open the file. Aware that the cables were now circulating freely beyond their control, Wikileaks released the full cache itself, publicizing the event on Twitter. A Wikileaks insider claimed that Assange would have released the full file at some point regardless of the incident, but Assange blamed Leigh and Domscheit- Berg for the mass release. See “Leak at WikiLeaks: Accidental Release of US Cables Endangers Sources,” Der Spiegel, August 29, 2011, www.spiegel.de/international/world/leak- at- wikileaks- accidental- release- of- us- cables - endangers- sources- a- 783084.html.

27. For a discussion of how the news filters of Wikileaks’ initial media partners affected cable reporting, see Lisa Lynch, “The Leak Heard Round the World.”

28. For a discussion of media silence regarding the DRC, see Stearns, Dancing in the Glory; and Alison Holder, “Forgotten or Ignored? News Media Silence and the Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo” (master of science thesis, London School of Economics, 2004).

29. Nicholas D. Kristof, “Congo’s Forgotten War,” New York Times, February 10, 2010.30. The common tropes used in Congo reportage are described in Severine Autesserre,

“Dangerous Tales: Dominant Narratives on the Congo and Their Unintended Consequences,” African Affairs 111, no. 445 (2012): 1 – 21; Susan L. Carruthers, “Tribalism and Tribulation: Media Constructions of ‘African Savagery’ and ‘Western Humanitarianism’ in the 1990s,” in Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime, ed. Stuart Allan and Barbie Zelizer (New York: Routledge, 2004), 155 – 73.

31. All cables in this article are referred to by their official State Department reference tag and are archived at Cablesearch.org, a web cache of the Wikileaks archive. Robert Booth and

66 Radical History Review

Julian Borger, “US Diplomats Spied on UN Leadership,” Guardian, November 28, 2010, www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/nov/28/us- embassy- cables- spying- un.

32. For press speculation regarding Clinton’s resignation, see Howard Chua- Eoan, “WikiLeaks Founder Julian Assange Tells Time: Hillary Clinton ‘Should Resign,’ ” Time, November 30, 2010; David Corn, “Should Clinton Resign over WikiLeaks?,” The Last Word with Lawrence O’Donnell, MSNBC, November 30, 2010, www.nbcnews.com/id/45755883/ns /msnbc- the_last_word/vp/40445068#40445068; Jack Shafer, “WikiLeaks, Hillary Clinton, and the Smoking Gun,” Slate, November 29, 2010, www.slate.com/articles/news_and _politics/press_box/2010/11/wikileaks_hillary_clinton_and_the_smoking_gun.html.

33. Examples of such coverage include “Africa: U.S. Sought Personal Details of Great Lakes, Sahel Leaders,” AllAfrica, November 29, 2010, allafrica.com/stories/201011291834.html; Pierre Boisselet, “Washington place la région des Grand Lacs sous haute surveillance” (“Washington Places the Great Lakes Region under High Surveillance”), Jeune Afrique, November 29, 2010; “Africa: US Sought Personal Details of Great Lakes, Sahel Leaders,” Ethiopian Review, November 29, 2010; “Le Cobalt Congolais sous surveillance Américain” (“Congolese Cobalt under American Surveillance”), Le Potential, December 7, 2010, quoted in Congo Forum, December 2, 2012, www.congoforum.be/fr/nieuwsdetail.asp?subitem=1&newsid=172862&Actualiteit; “US Embassy Ordered to Collect Information on Rwandan Military,” Rwanda News Agency, November 29, 2010, www.rnanews.com/politics/4505 – us - embassy- ordered- to- collect- information- on- rwanda- military; “WikiLeaks: Kabila, Kagame, Museveni, Nkurunziza dans le Scanner des USA” (“WikiLeaks: Kabila, Kagame, Museveni, Nkurunziza under the Scanner of the USA”), L’Avenir, December 2, 2012, www.groupe lavenir.cd/spip.php?article37030.

34. Tim Lister, “WikiLeaks: From Congo to the Caucasus — Chasing Loose Nukes,” CNN, December 20, 2010, articles.cnn.com/2010 – 12 – 20/us/wikileaks.loose.nukes_1_uranium - nuclear- research- center- congo- capital/3?_s=PM:US.

35. Julian Borger and Karen McVeigh, “WikiLeaks Cables: How US ‘Second Line of Defence’ Tackles Nuclear Threat,” Guardian, December 19, 2010, www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010 /dec/19/wikileaks- cables- us- nuclear- threat.

36. Luis Prado and Alvarado de Cozar, “El material nuclear circule sin control en el corazón de Africa” (“Nuclear Materials Circulate out of Control in the Heart of Africa”), El País, December 19, 2010, www.elpais.com/articulo/internacional/material/nuclear/circula /control/corazon/Africa/elpepuint/20101219elpepuint_31/Tes.

37. Mimouna Hafidh, “RD Congo: Des équipements nucléaires à la abandon” (“DR Congo: Nuclear Equipment Has Been Abandoned”), Le Griot, December 31, 2010, www.legriot .info/860 – rd- congo- des- equipements- nucleaires- a- l%E2%80%99abandon.

38. Pierre Boisselet, “WikiLeaks: Ces inquiétants vestiges de nucléaire congolais” (“Wikileaks: Worrying Remains of Congolese Nuclear Activity”), Jeune Afrique, December 22, 2010, www.jeuneafrique.com/Articles/Dossier/ARTJAWEB20101222172155/italie- securite- etats - unis- uraniumwikileaks- ces- inquietants- vestiges- du- nucleaire- congolais.html.

39. Alain Lallemand, “WikiLeaks: Alertes à l’uranium congolais” (“Wikileaks: Warnings about Congolese Uranium”), Le Soir, December 20, 2010, www.lesoir.be/archives?url=/actualite /monde/2010 – 12 – 20/wikileaks- alertes- a- l- uranium- congolais- 809934.php. The original reads: “Bref, avec trois ans de recul, il apparaît que la région des Grands Lacs est bien plus dangereuse par la libre circulation de ses rumeurs que par l’éventuelle contrebande de ses ressources radioactives.”

40. “Uranium: WikiLeaks égratigne le Groupe Malta Forrest, mais . . . ” (“Uranium: Wikileaks

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 67

Scratches the Malta Forrest Group, but . . .”), Congo Independent, December 23, 2010, www.congoindependant.com/article.php?articleid=6200.

41. Frère, The Media and Conflicts.42. The cable noted that Kabila feared that Kamerhe was becoming too influential, an

observation supported by the politician’s subsequent run for president in the fall of 2011. Bart Beirlant, “Kabila kocht parlement om” (“Kabila Bought Parliament”), Der Standaard, February 7, 2011, www.standaard.be/artikel/detail.aspx?artikelid=HD360NM5.

43. “Kabila avait un problème personnel avec Karel De Gucht” (“Kabilia Has A Personal Problem with Karel De Gucht”), Le Vif, February 7, 2011, www.levif.be/info/actualite /international/kabila- avait- un- probleme- personnel- avec- karel- de- gucht/article - 1194944942867.htm.

44. Pierre Boisselet, “WikiLeaks – DRC: La rivalité Kabila- Kamerhe, vu par Washington” (“The Rivalry between Kabila and Kamarhe, Seen by Washington”), Jeune Afrique, February 9, 2011, www.jeuneafrique.com/Articles/Dossier/ARTJAWEB20110208193931/onu- france - chine- etats- uniswikileaks- rdc- la- rivalite- kabila- kamerhe- vue- par- washington.html; “RDC: Wikileaks expose la corruption de ‘Joseph Kabila’ dans le affaire Vital Kamerhe” (“RDC: Wikileaks exposes the Corruption of ‘Joseph Kabila’ in the Case of Vital Kamerhe”), Cameroon Voice, March 4, 2012, www.cameroonvoice.com/news/article- news- 3011.html; “Africa News: Secrets sur WikiLeaks: Kamerhe photographié sous son vrai jour” (“Africa News: Secrets on Wikileaks: Kamerhe Photographed in His True Light”), Radio Okapi, February 9, 2011, radiookapi.net/revue- de- presse/2011/02/09/africa- news- secrets- sur - wikileaks- kamerhe- photographie- sous- son- vrai- jour.

45. “Selon un ambassadeur américain, Kamerhe est peu crédible” (“According to the American Ambassador, Kamarhe Is Not Credible”), Groupe L’Avenir, February 11, 2011, www .groupelavenir.cd/spip.php?article38368.

46. Emmanuel Chidiogo, “Obasanjo Wanted Kagame to Rule Congo,” Daily Times, March 6, 2011, dailytimes.com.ng/article/obasanjo- wanted- kagame- rule- congo.

47. See the online discussion titled “Kagame ‘President’ of the DRC” at Congo Diaspora Forum, March 9 – 10, 2010, congodiaspora.forumdediscussions.com/t3877 – kagame - president- de- la- rdc- wikileaks; and Jean Mitari, “WikiLeaks: Obasanjo verrait bien Kagame diriger la RDC” (“Obasanjo Would See Kagame Direct the DRC”), JamboNews, March 11, 2011, www.jambonews.net/actualites/20110311 – wikileaks- obasanjo- verrait- bien- kagame - diriger- la- rdc.

48. “Le pavé de Général Obasanjo suscite de terribles questions” (“General Obasanjo’s Advice Raises Terrible Questions”), Le Phare (Kinshasa, Congo), March 9, 2011.

49. Pierre Englebert, “Why Congo Persists: Sovereignty, Globalization, and the Violent Reproduction of a Weak State,” Queen Elizabeth House Working Papers Series 95 (University of Oxford, Oxford, 2003).

50. Julien Paluku, “Révélations de WikiLeaks sur le plan de balkanisation de la RDC?” (“Revelations by Wikileaks about the Plan to Balkanize the DRC?”), Beni- Lubero Online, December 12, 2010, benilubero.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id =2258:revelations- de- wikileaks- sur- le- plan- de- balkanisation- de- la- rdc- &catid=19:culture - grale&Itemid=88. The original reads: “Comme les secrets publiés par les 5 journaux précités ne l’ont été que sur accord de leurs gouvernements respectifs, il se pourrait que tous les gouvernements impliqués dans le plan de Balkanisation de la RDC n’aient pas autorisé la divulgation des secrets y afférant pour ne pas faire voler l’oiseau avant qu’on ne l’attrape.”

68 Radical History Review

51. “Le Congo, oublie à Wikileaks?” (“Congo, Forget Wikileaks?”), Mwinda, December 13, 2010. www.planete- islam.com/showthread.php?18039 – Le- Congo- oubli%E9 – de- Wikileaks.

52. “Projet de balkanisation de la RDC: Les Congolais interrogent WikiLeaks” (“The Project to Balkanize the DRC: The Congolese Interrogate Wikileaks”), Le Phare, February 9, 2011, www.lephareonline.net/lephare/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3332 :projet- de- balkanisation- de- la- rdc- les- congolais- interrogent- wikileaks&catid=44:rokstories&Itemid=106. The original reads: “Pourquoi WikiLeaks, si prompt à déballer des ‘monstres’ tels que le FBI (Police fédérale américaine) et la CIA (services des renseignements américains) ou des dirigeants de grandes puissances de la planète.”

53. “Congo – Angola: Embarrassantes révélations de WikiLeaks” (“Congo – Angola: Embarrassing Revelations from Wikileaks”), Le Phare, February 16, 2011, www.lephareonline.net/lephare /index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3367:congo- angola- embarrassantes - revelations- de- wikileaks&catid=46:rokstories&Itemid=106. The original reads: “Convaincus que WikiLeaks cache de nombreux câbles sur leur pays, les Congolais continuent d’attendre de ce site des éléments de réponse face à l’insécurité qui accable les parties Nord et Est de la République mais aussi au plan de balkanisation des terres leur laissées par leurs ancêtres. Si la boîte à Pandore pouvait être ouverte, chaque Congolaise et chaque Congolais pourraient savoir sur quel pied danser dans les semaines et mois à venir.”

54. Quoted in Alex Engwete, “WikiLeaks: US Kinshasa Embassy Concerns over ‘Balkanization Conspiracy Theory,’ ” Alex Engwete (blog), August 28, 2011, alexengwete.blogspot.ca/2011 /08/drc- elections- 2011 – watch- 1 – wikileaks- us.html.

55. Ibid.56. “La balkanisation de la RDC préoccupe les USA” (“The Balkanization of the DRC

Concerns the USA”), Le Potential, August 31, 2011, www.lepotentiel.com/afficher_article .php?id_edition=&id_article=114536.

57. Freddy Mata Matundu (Congolese journalist), personal correspondence. Radio France International ran a story about the Kamerhe cable in February 2011 that also would have been available to radio audiences.

58. Mohammed Keita, “DRC Journalists Urge Ruling Party to Halt Abuse,” CPJ Blog, Committee to Protect Journalists, August 29, 2011, www.cpj.org/blog/2011/08/drc - journalists- urge- ruling- party- to- halt- abuse.php.

59. Theodore Trefon, “Augustin Katumba Mwanke: Profile and Analysis,” Congo Masquerade (blog), February 12, 2012, congomasquerade.blogspot.ca/2012/02/augustin- katumba - mwanke- profile.html.

60. Pierre Boisselet, “RDC – WikiLeaks: Faible susceptible et mystérieux . . . Kabila vu par Washington” (“DRC – Wikileaks: Weak, Susceptible, and Mysterious . . . Kabila Seen by Washington”), Jeune Afrique, November 21, 2011, www.jeuneafrique.com/Articles/Dossier /ARTJAWEB20111121164838/joseph- kabila- kinshasa- rdc- etats- unisrdc- wikileaks- faible - susceptible- et- mysterieux- kabila- vu- par- washington.html. “Augustin Katumba Mwanke: L’unique point d’accès à Joseph Kabila” (“Augustin Katumbe Mwanke: The Only Access Point to Joseph Kabila”), KongoTimes!, September 19, 2011.

61. Alex Engwete, “WikiLeaks: Joseph Kabila, Augustin Katumba Mwanke, and Dan Gertler,” Alex Engwete (blog), September 5, 2011, alexengwete.blogspot.ca/2011/09/drc - elections- 2011 – watch- 1 – wikileaks_05.html.

62. Kimp [pseud.], “Déballage de WikiLeaks: Jusqu’ou?” (“Unpacking Wikileaks: How Far?”), Le Phare, September 22, 2011, www.lephareonline.net/lephare/index.php?option=com _content&view=article&id=4435:deballage- de- wikileaks- jusquou- &catid=42:rokstories &Itemid=102. The original reads: “La grande interrogation qui traverse de nombreux esprits

Lynch | Cablegate in the Congo 69

est celle de savoir pourquoi le site WikiLeaks donne- t- il l’impression de vouloir jeter des pavés dans la mare, au moment précis où nombre de Congolaises et Congolais candidats à la présidentielle et à la députation nationale s’emploient à présenter au grand public la meilleure image possible de leur personne . . . il est difficile de savoir de quel côté se trouve la vérité. En tous les cas, avec la moisson d’informations leur fournies à ce stade, candidats et électeurs savent à peu près sur quel pied danser à partir de novembre 2011.”

63. Robert Kalumba, “Uganda: Questions on Democracy following the Wikileaks Crisis,” Daily Monitor (Kampala, Uganda), December 6, 2010.

64. Julie Owono, “D.R. of Congo: Congolese Diaspora Erupts against Kabila,” Global Voices (blog), December 9, 2011, globalvoicesonline.org/2011/12/09/d- r- of- congo- congolese - diaspora- erupts- against- kabila.

65. For further discussion of online civil society movements, see Muzzamil Hussain and Philip M. Howard, “Opening Closed Regimes: Civil Society, Information Infrastructure, and Political Islam” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC, July 2010).