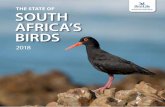

British Birds

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of British Birds

British Birds Vol. 57 No. 10

O C T O B E R 1 9 6 4

The effects of the severe winter of 1962/63 on birds in Britain

By H. M. Dobinson and A. J. Richards (Plates 58-61)

CONTENTS

(1) Introduction 373 (11) Nest record cards as evidence (2) Data obtained . . . . . . 376 of breeding strength . . 403 (3) The questionnaire . . . . 377 (12) Effects observed abroad . . 405 (4) The weather 381 (13) The winter of 1961/62 , . 407 (5) Hard weather movements . . . 382 (14) Comparison with previous (6) Numbers abnormally present hard winters 408

or absent 387 (15) Systematic list of species . . 410 (7) Birds found dead 390 (16) Acknowledgements . . . . 428 (8) Less usual foods 395 (17) Summary . . 430 (9) Condition of birds during the (18) References 431

winter 398 (19) Appendix of scientific names (10) Comparison of breeding not in the systematic list 434

strength 399

( i ) INTRODUCTION

I T H A S B E E N T H E C U S T O M after exceptionally severe win te r s t o

inc lude in this journal a paper es t imat ing the effects on b i rds in Bri tain.

H a r d winters are relatively infrequent and since the last such analysis,

cover ing 1946/47 (Ticehurs t and Har t ley 1948),* there has been a great

expansion of amateur o rn i tho logy . T h e severe wea ther of 1962/63

therefore presented an o p p o r t u n i t y of a t t empt ing a m o r e ambi t ious

assessment than in the past . W e are still falling far shor t of the a m o u n t

of detail that is desirable, however , and it is h o p e d that by the next h a r d

*The winter of 1955/56 was considerably more severe than is normal, but was not the subject of any particular British study. Nevertheless, comments on its effects on our birds are to be found in Burton and Owen (1957), Philips Price (1961), Seel (1961) and Beven (1963), while general papers on the Continent included those by Geroudet (1956) and Piechocki (1957).

373

location of Observers m area defined D area undefined

F I G . I . Areas of the British Isles from which reports of the effects on birds of the 1962/65 winter were received. Filled squares show where the sizes of the areas concerned were defined (see page 576), and open squares where they were not. Also marked are the boundaries of the broad regions of England referred to in the text and listed at the foot of this page

(drawn by Robert Gillmor)

Regions of England referred to in the text England, SE: Kent, Sussex, Surrey, Hampshire, Berkshire, Wiltshire England,E: Essex, Middlesex, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Huntingdonshire, Cambridgeshire, Suffolk,

Norfolk, Lincolnshire Midlands, E: Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Rutland,

Nottinghamshire Midlands, W: Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Shropshire, Staffordshire England, SW: Dorset, Somerset, Devon, Cornwall England, NW: Cheshire, Lancashire, Westmorland, Cumberland Midlands, N: Derbyshire, West Yorkshire England, NE: North and East Yorkshire, Co. Durham, Northumberland

374

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

F I G . 2. • Locations of reports of birds found dead in the British Isles during the 1962/6} winter (see section 7 on pages 390-395). The pattern is so similar to the distribution of contributors to the enquiry (fig. 1) that mortality could presumably

have been noted wherever observers were present {drawn by Robert Gillmor)

375

BRITISH BIRDS

winter British ornithologists will have so organised themselves as to be able to make a thorough record of its effects. In this paper we can do no more than document and analyse the events and consequences on the basis of good indications; we have not enough exact data to allow us to produce statistically significant results. It ought to be possible to remedy this in future, and all amateurs can help by supporting such censuses as the Breeding-bird Population Census and the Inland Observation Point schemes of the British Trust for Ornithology.

An enquiry of this sort is bound to attempt to record a considerable variety of effects. While the change in the size of the breeding population the following summer is an important aspect, it is by no means the only one. Some birds are so mobile—and radar is now showing us how badly their mobility has been underestimated in the past—that the effects of the winter observed at the time may well involve the deaths of birds belonging to populations which breed hundreds of miles from here; while the depletion of our own breeding stocks may be caused by weather in Iberia as much as by the weather here.

This, of course, is an argument for instituting an international enquiry; but the one we are concerned with is solely British. Our aim was to place on record the effects observed here: the mortality during the winter; the movements into, through, and out of the country; and then the changes in the numbers breeding. We chose the dates ist November 1962-3151 March 1963 as our limits, except for the estimates of numbers breeding which take us into May 1963. We are not concerned with dates of breeding, clutch size or breeding success. While the winter may have had an effect on some or all of these, they seemed to be topics falling outside the scope of our enquiry.

( 2 ) DATA OBTAINED

Most of the data we received were sent on a questionnaire (see section 3). We received questionnaires, or letters in lieu of questionnaires, relating to 261 areas in Great Britain. The locations of these are mapped on fig. 1.

Ninety-three of these reports were based on exact counts in defined areas, and the rest on estimates. Some of the latter involved detailed knowledge of the localities concerned and were almost tantamount to exact counts, while others were more general, being based on large areas or areas not visited frequently.

The sizes of the largest areas are often vague, being given as 'the southern half of the county' or something similar, but 202 of the observers defined theirs more precisely and these mav be summarised as follows:

1 t o 5 acres . . . . 14 101 acres to 1 square mile . . 55 6 t o 20 acres . . . . 14 1 to 10 square miles . . . . 5}

21 to 100 acres . . . . 15 M o r e than 10 square miles . . 51

376

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF I 9 6 2 / 6 3

A total of 182 of the reports included rural areas, and 67 included urban areas; 13 referred to beaches.

We have also drawn information from elsewhere. Others working on special aspects of the effects of the winter—for example, certain species or areas—have all been most generous over supplying us with information. In particular, the British Trust for Ornithology kindly allowed us access to its data and its officers have been extremely helpful. Data have been used from the Ringing Scheme, the Nest Record Cards, the Inland Observation Points (I.O.P.s) and special enquiries. Records from the Breeding-bird Population Census are being prepared for publication elsewhere by Kenneth Williamson. We have also seen the bulletins of 14 local societies, and been in touch with the editors of 27 local reports. Finally, we have used a variety of miscellaneous material, including about 70 letters sent to R. S. R. Fitter for The Observer, to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and to C. K. Mylne for the B.B.C.; and some press cuttings collected by the Council for Nature.

It may be that between 750 and 1,000 observers have therefore contributed records, directly or indirectly, to this enquiry. While this is an impressive total, it is a pity that there must be several thousand other observers with observations which we have not been able to use. Had we had more data—and had we been able to find some means of handling them—far greater detail would have been possible, especially in relation to differential effects in various habitats or regions.

( 3 ) THE QUESTIONNAIRE

The questionnaire that was issued is reproduced here as figs. 3 and 4. It was accompanied by instructions which asked for information on any changes observed in the breeding strength or, equally important, any good evidence that there had been no radical changes. Information was also requested for effects observed during the winter itself, either during the cold weather in November when many parts of the country had severe freezing fog, or in the period from the end of December till late February or March when temperatures were very low and there was much snow. It was stressed that it was important that, wherever possible, exact figures based on counts made at the time should be given. Only where these were not available should more general statements be made. In the section relating to changes in breeding strength, observers who had not got exact counts were asked to classify the changes into four categories: A=exterminated, B=large decrease, C=litt le or no change, and D=increase.

The questionnaire served a useful function in conveying to observers the type of information we wanted and the way it should be laid out, and this allowed us to use more records and to cope with them in less

377

BRITISH BIRDS

time. Much further information of great value was submitted on sheets of paper appended to the questionnaires or sent on their own.

The use of a questionnaire Now that various regular counts are at last being made in an attempt to gauge the population of our birds from year to year, it may be wondered whether a questionnaire of this sort can still perform any useful function. The regular counts range from intensive studies of certain areas, such as a Surrey oakwood (Beven 1963) or farmland (John Robbins, unpublished), to such national enquiries as the Wildfowl Counts, the B.T.O.'s Breeding-bird Population Census and the Inland

1

2

4

6

7

8

S

10

16

17

18

BRITISH BIRDS

INQUIRY INTO THE EFFECTS OF THE WINTER I9&2/IM3

Name of observer:

Address;

Name of area reported on :

Grid Ref.:

County

Altitude from ft. to ft.

Are your comments based on an exact count in a denned area? Yes/no

If so, give approximate size and shape of area.

If not, how large ar. area are you considering and

how thoroughly have vou examined it?

What habiiat(s) are involved? (farmland, woodland, garden, etc.)

Food supplies. Give any details possible about food supplies (e.g. berries) being exhausted or inaccessible due to snow, ice, or freezing rain, with approximate dates. Please alio indicate presence of exceptional areas (e.g. running water when surrounding area frozen.)

Did you see birds taking unusual foods? Give details,

Influence of man. Have you iny evidence of "unnatural" effects by;—

(!) Provision of abnormal food supplies. (2) Shooting. (3) Any other means?

Were there any exceptional changes in numbers after the 1961/1962 winter? If so, give details of species and changes.

37

36

34-

V,

31

30

29

26

ZJ

25

U

23

ZZ

21

2U

19

F I G S . 3 and (opposite) 4. The two sides of the questionnaire that was issued to obtain information on the effects of the 1962/63 winter; this was accompanied by a sheet of instructions which are summarised on page 377. The numbers at the

edges related to punched holes designed to assist in the analysis

378

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

Observation Point scheme. Besides these, there is work done by specialists on certain species and a considerable number of specific B.T.O. enquiries.

As yet, however, none of these can give us all the data that we need. The Wildfowl Counts are primarily designed to measure numbers in winter and are confined to only a few species; the Breeding-bird Population Census was still in its infancy in 1962 and 1963, confined to a relatively small number of farmland areas and hardly dealing with other habitats at all; and the I.O.P.s were also too few in number to provide really useful results for the winter in question.

Yet there are obvious crudities in obtaining information by means of a questionnaire. One is that observers may be reluctant to report when 'no change' has occurred, with the result that the number of reports of a serious decline may seem proportionately more numerous 38

37

36

34

33

V.

31

30

28

27

26

34

71

21

20

19

Species

(Wetmore order would be

helpful)

Change in

breeding strength

1962-1963

Abnormal numbers present

Yes/no month(s)

Abnormally

Yes/no month(s}

Departed

Date(s)

Found dead

1962 1963

Nov. Dec. Jan. ! Feb. Mar.

i 1

! 1 1 •

|

1 - 1

1 1

i i

1

1

1

4

•>

b

7

** 9

ilJ

11

1}

16

16

379

B R I T I S H B I R D S

than they should be. Another is the use of categories for recording changes in breeding strength: even if the categories are reasonably closely defined, there may be a difference in interpretation; besides this, in a small area the loss of one pair may mean total extermination and hence category A, while in a larger area the loss of ten pairs out of twelve would result in category B.

We were not happy at the thought of asking observers to estimate a small change in population if they had not made counts, and so we reduced the number of categories from the five used in previous analyses to four. This proved to be a mistake, however, as it did not allow sufficient sensitivity, and we finished by admitting two borderline categories—AB where a substantial population was reduced by about 95%, and BC for a small drop.*

Of the 4,502 records used, 37% were based on exact counts in defined areas in 1962 and 1963. This was a sufficiently large proportion to give us some idea of the accuracy of estimates made by observers and the degree of bias likely to be entering our raw data. We divided all records of breeding strength into those based on counts and those based on estimates. Where the observers had recorded the actual figures without a category we allocated these to the appropriate one. Theoretically, the proportion of records in each category should have been the same in both sections of the data. In fact, the results obtained were:

Based on counts Based on estimates

A

14-4% 7-2%

AB

1.0%

i . 7 %

B

28 .8%

34-9%

BC

4-7% 7-9%

C

39-2% 43-3%

D

" . 9 % 5.0%

There is no bias towards an exaggeration of the A category in the section based on estimates; on the contrary, there are more records in this category from the section based on counts. This, of course, is probably explained by the counts being based on smaller areas than the estimates.

There is, however, evidence that the lack of A reports is balanced by B reports in the observations based on estimates, as this and BC categories are substantially commoner. It is interesting too that the proportion of D records is less than half of that where counts have been used. The sensitivity of small areas, as with A, can apply here, but it is also possible that where counts are not made small increases are overlooked, especially in a year when observers are expecting drastic reductions.

The two sets of figures are significantly different on the x1 t e s t when taken en masse, but some of the individual pairs are either not signifi-

*In our own analysis, we have taken BC to represent a fall to between 15% and 33% of the 1962 figure and B to between 33% and 95%; any increase ranks as D.

380

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF I 9 6 2 / 6 3

cantly different or only marginally so (p^o .o j ) . While these differences exist and it is clear therefore that the two

sets of figures are not strictly comparable, the difference never exceeds 7.2% of the proportion, and, with our small samples, it has seemed best not to attempt to keep the records apart. Hence, in the systematic list, conclusions are based on both the counts and the estimates.

( 4 ) THE WEATHER

The winter of 1962/63 was the coldest recorded in central and southern England since 1740 (Booth 1964) and possibly the snowiest for 150 years (Lamb 1963). The regional variation was considerable, as can be seen from table 1. Most coastal regions (except the Channel) had little snow, but inland snowfall was heavy and high winds piled it into deep drifts. Frosts were mild and limited in north Scotland, northwest England,* and the western seaboards, but severe in many other parts of Britain and worst on the Berkshire/Wiltshire border (Tunnell 1964). The ground temperature one foot below the surface fell to — 3.2° C at Oxford and was well below freezing in many other places (Booth 1964).

Rivers and lakes almost everywhere were frozen over; the Thames was partly frozen even in London for two or three weeks in January. Two more unusual effects both had particular significance for birds. Freezing fog, especially frequent in early December and again in late December, covered trees in parts of the country with layers of ice; in Durham a thin twig was found surrounded by a shell of ice four centimetres in diameter and every tree within miles was icebound (this has occurred, often to a more marked extent, in previous severe winters: see section 14). Also, in late December and January many beaches entirely froze up, often to 400 yards below the high tide mark, and sheltered bays, such as Egypt Bay, Kent, were frozen solid. Long stretches of shore in the south resembled an arctic coastline of ice, from which floes and even small icebergs were breaking. Feeding places for waders and ducks were reduced to a minimum and some areas which were kept free of ice, such as Pagham Harbour, Sussex, had spectacular concentrations of shore-birds. Kent and Sussex perhaps suffered most severely from frozen beaches. The water temperature in the Channel fell to between 20 and 4° C, and all the North Sea south of Yorkshire cooled to below 2° C by the end of February.

November was not unusually cold, but December temperatures were as much as 4° C below average, while minima in January and February were as much as 70 C below average. The severity of the cold is vividly demonstrated by the fact that in two of the localities in table 1 the maximum temperature had an average below freezing in January.

*Areas of Britain are those used in the weather forecasts. They are defined and shown in fig. 1 on page 374.

381

B R I T I S H B I R D S

Table I. Mean temperatures in Britain in 1962/63 in ° C and deviations from averages for the last 30 years

The figures are quoted by permission of the Director-General of the Meteorological Office

Maximum Deviat ion M i n i m u m Deviat ion

Max imum Devia t ion Min imum Deviat ion

Max imum Deviat ion Min imum Deviat ion

Max imum Deviat ion Min imum Deviat ion

Max imum Deviat ion Min imum Deviat ion

K e w (Surrey)

8.8 - 0 . 8

4-7 — 0.1

4.8 — 2.1

0.8

- 2 . 4

0.6

-6.x

- 2 - 7 - 5 - 5

2 . 2

- 5 - i — 1.4

- 3 - 9

9.9 - 0 . 3

4 . 0

+ 0 . 8

Boscombe D o w n (Wiltshire)

8.2

1 .2

2.8

- 0 . 6

4.8 — 2.0

- 0 . 8 - 2 . 4

-0 .8

- 7 - 3 ~ 5 - 3 - 6 . 7

1 .2

- 5 - 9 -3 -3 -4-5

9-3 - 0 . 7

2.3

+ 0 . 5

E l m d o n Dishforth (Warwickshire) (Yorkshire)

7-7 - 1 . 4

2.3

- i - 5

4-2

- 2 - 3 - 1 . 6

- 3 - 9

— 0.1

- 6 . 3

- 5 - 5 - 7 - i

i-4 - 5 - 4 - 3 . 8

- 5 - o

9-i - 0 . 5

2 . 2

+0.5

7-2

- J - 3 2.4

— 1-4

3-5 2-7

~!-5 - 3 . 6

1.6

4.4

- 3 - 1

~ 4 - 4

i-4 - 5 - 2

- 4 . 1

- 5 - 5

8.7 - 0 . 8

1-5 - 0 . 5

Leuchars (Fife)

7.6 - 0 . 8

2 . 0

- 0 . 9

4.8

- 1 - 5 - 0 . 5 - 2 . 4

2.6

- 3 - i — 2.1

- 3 - 2

3- 2

- 3 - 5 - 3 . 2

- 4 - 5

8.4 - 0 . 3

1 .2

- 0 . 8

However, the winter was not merely exceptional for temperature. Sunshine at Kew was 11% above average, and precipitation 22% below average, between 1st December 1962 and 31st March 1963.

To sum up, then, the winter of 1962/63 was roughly divisible into three periods. A normal November and early December was interrupted by frosts and freezing fog (but little snow) in the first week of December. The hard weather started on the 26th; blizzards from the 26th to the 28th covered the country with snow and this lay in many parts until March. A very cold but sunny period at the end of January was followed by cold and unsettled weather in February, with sunshine and showers of sleet and snow alternating. The thaw came at the beginning of March, and rain and wind helped to clear Britain of snow and ice by the 10th of that month.

( 5 ) H A R D W E A T H E R M O V E M E N T S

There is much evidence to show that large-scale movements of birds occurred during the hard weather. Unfortunately, however, many difficulties beset any detailed analysis. The picture is consequently

382

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF I 9 6 2 / 6 3

much less clear than one would wish. Our data come from four sources: sightings of visible passage; inferences from changes in population size; ringing recoveries; and radar. Each category covers a particular aspect of the problem, and each adds more to the general picture.

Records of visible passage, sent to us directly or through the I.O.P.s, are perhaps potentially misleading evidence and have to be treated with great caution, as it is now clear that many migrating birds often fly above the level of ordinary observation. Another difficulty is to know whether records of visible passage refer to birds moving a great distance. Reports of large scale Starling* and Woodpigeon passage north and east in early January may refer to local feeding or roosting movements, particularly when not correlated with radar or other data. It is of course impossible to select data on an arbitrary principle, and thus all have been incorporated.

The most indirect evidence is that from the changes in population during the winter. This has the disadvantage remarked on in section 6 that sudden absence of a species does not necessarily imply departure, and that evidence from other localities, visible passage and the possibility of death should all be taken into consideration. In many cases, however, population change can provide strong circumstantial evidence of movements.

Ringing data can be very valuable in showing directions of movement, but only very limited samples are available, so that the picture obtained could be distorted. In the present context, birds both ringed and recovered within the period under consideration are clearly of greatest value, but exceptional recoveries (e.g. Linnet) may also be useful if several years are considered.

Radar is now an invaluable asset, and we are extremely grateful to Dr. E. Eastwood and his colleagues at Marconi for their co-operation and the time they spent in showing us their film records of birds over east and south-east England. Our data are too scanty for detailed correlation of the radar and visible passage records, but we have attempted as much as possible.

Our data on hard weather movements are presented in the systematic list (section 15) and chronologically here.

December The hard winter can be said to have started with December. There was hard frost throughout the country from the 1st to the 8th, with snow (chiefly in the north), and winds light and southerly: conditions were therefore good for passage. This apparently initiated movement west and south, particularly of Lapwings, Skylarks, Fieldfares and Red-

*Scientific names of species are given in the systematic list (section 15) on pages 412-428 or in the appendix on page 434.

383

BRITISH BIRDS

wings, although reports of Golden Plovers, Snipe, Blackbirds, Meadow Pipits and Linnets moving were also received.

This passage slackened with the onset of the thaw on the 9th, and the little recorded for the next ten days is assignable to typical winter movement: Golden Plovers, Fieldfares, Redwings and, in particular, Lapwings being the birds chiefly involved.

The first sign of the weather to follow showed on the 20th with a heavy frost. On the 22nd another sharp frost proved to be the first of 3 5 days of uninterrupted country-wide minimum temperatures below freezing point. This change was immediately followed by passage, probably mostly from Scandinavia, of grebes, ducks, waders (especially Lapwings), Skylarks, Fieldfares, Redwings, Song Thrushes, Blackbirds, Starlings and such semi-rarities as Bewick's Swans and Lapland Buntings, all moving west or south before a light easterly wind. On Christmas Day passage was in progress on a large scale. Then on Boxing Day most of the country suffered a severe blizzard. Heavy passage was recorded, especially on the east coast, and the continued snowfall of the 27th and the 28th led to further passage. The dominant species flying west and south were Lapwings and Skylarks, of which many millions must have poured into and through the country in this period.

Passage was wholesale, and countrywide, as was clear from radar evidence, but large-scale immigration, especially from Cap Gris Nez or Cherbourg, made the picture complicated and many species were involved for the first time in the winter; these included such birds as Herons, White-fronted Geese, Woodlarks, Greenfinches, Bramblings and Snow Buntings. Most sight records were of birds flying southwest or, near the south coast, north-west, and the appalling conditions may have forced many flocks to fly lower than usual and often within visual range.

January In the first ten days temperatures were as much as 120 C below freezing, winds were light northerly or easterly and there was light snowfall, so conditions were again good for passage. Consequently the passage which had begun on 26th December lasted till 13th January, a period of three weeks. The prolongation of very severe weather, accompanied by improved passage conditions, may have induced many birds to move which had not yet done so, and it was during early January that 'abnormal' movements into towns and to unfrozen shorelines resulted in spectacular congregations of the hungry and dying. Furthermore, the cold conditions of central Europe had become harsher than usual by early January, and it seems probable that many of the birds recorded passing through Britain in this period were of Continental origin. Radar reports on every dav available show heavv immigration from the

384

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF I 9 6 2 / 6 3

Low Countries into Kent, often accompanied by passage from mid-France into south-west England.

Reports indicate that passage slackened on the 2nd and 3rd, but a heavy departure south and south-west on the evening of the 4th continued through the 5 th and reached a peak on the 6th and 7th. Radar and sight records agree on this picture, and it seems likely that the passage on the 6th was the heaviest and most widespread of the winter. Lapwings and Golden Plovers ceased to play an important role in the reports and Woodpigeons increased, although the extent to which the latter were involved in genuine passage is uncertain. Skylarks, Fieldfares and Redwings were the birds most frequently recorded and huge numbers passed through the country in the first week of January.

Movement slackened on the 8th, but then from the 9th till the n t h radar showed birds arriving from the Low Countries and Scandinavia, and influxes were also extensively reported from the east coast on the 12th. It is possible that much of the movement from the 9th till the n t h was above the level of visibility, for many influxes inland were recorded. Skylarks were the chief participants on the east coast, but many other species included Chaffinches, Bramblings, Corn Buntings and especially Linnets.

A slight thaw occurred on the 15 th and 16th, but Continental immigration continued on the latter day with Skylarks still being seen. On the 17th the easterly winds dropped and heavy frost and snow returned. There was then an influx of Fieldfares and Redwings throughout the country, all travelling westward, but we have little indication of any other passage until the 29th when there were again heavy frosts and also light movements over many parts of Britain. These were not in any correlated direction and may have been the result of high-flying feeding movements in the clearer conditions. There was some immigration north-west from France on the 30th, however, which correlated with influxes of Skylarks into eight counties.

February February started with temperatures still below freezing and heavy snow showers. The snow may have led to a considerable immigration detected by radar on the east coast. This reached a peak on the 2nd and 3rd. Again, a wide variety of species accompanied the Skylarks, with Woodpigeons and Fieldfares predominant, and Greenfinches, Redpolls, Chaffinches, Bramblings, Yellowhammers, Corn Buntings and Reed Buntings in smaller numbers.

On the 7th there was a thaw, and rain fell until the 10th. Snow returned on the n t h . Arrivals of Fieldfares on the 10th and Skylarks and Starlings on the 13 th heralded the start of the Lapwing return on the 15 th. Ducks on the 16th, Skylarks and Redwings on the 17th, and a steady trickle of ducks and thrushes to the 22nd, occurred during

385

BRITISH BIRDS

bleak but somewhat milder weather. On the 23rd and 24th considerable Skylark return was accompanied

by a number of finch species, as well as Fieldfares and Starlings, but heavy movement did not start until the 27th. A radar record of heavy immigration into England from the south-west and south-east, passing north and north-east through Britain, continued through the night, and a departure presumed to be of Starlings was added in the morning. Sight records suggest that Skylarks and Fieldfares figured most prominently in these movements, although other thrushes and Lapwings were apparently also involved.

March There was no radar record for 2nd or 3rd March, but the same pattern of movement as at the end of February was recorded on the 4th. On the other hand, sight records documented a large return from the 2nd to the 7th; during this time there was a sudden thaw on the 5 th, which

F I G . 5. Movements of four species recorded in the British Isles during the 1962/63 winter, compiled from the numbers of records of each species over three-day periods: any records of passage involving twenty or more birds, regardless of direction, and all records of departure or arrival are included {drawn by A. J. Richards)

386

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

marked the end of the hard weather. Lapwings and Skylarks were predominant in this return, and again many millions of birds were involved. Golden Plovers, Woodpigeons and Fieldfares also figured in large numbers, but Redwings and finch species were not recorded.

The radar record for this period clearly shows heavy north-east movement continuously over Britain from north and north-west France, departing north-east from east Britain by the 7th. Dawn influxes of Starlings into this movement are clear, and this species may have been more important than the sight records suggest.

For the rest of the month, a slow return of ducks, White-fronted Geese, Lapwings, Skylarks, Fieldfares, Linnets and Chaffinches continued north into Britain and then east into the Continent. Temperatures remained above freezing and winds chiefly moderate, although radar shows that some days were more favoured for movement, in particular the 14th, 16th, 19th, 20th, 21st and 25 th and especially the 27th, on all of which easterly passage occurred.

Summary Fig. 5 illustrates movement observed or inferred for Skylarks, Lapwings, Fieldfares and Redwings from 1st November till 31st March. These figures have been compiled from the numbers of records of each species over three-day periods. Any records of passage concerning 20 or more birds, regardless of direction, and all records of departure or arrival are included.* Although far from accurate, and not a quantitative measure, this method shows the periods of chief movement quite effectively. The return of Lapwings and Fieldfares is sharply distinguished from that of Redwings, and the successive waves of immigration by Skylarks from the Continent are also characteristic. The chief periods of movement, 3rd-8th December, 21st December-8th January, i2th-i 5th January and 27th February-6th March, are clearly marked.

No account of radar observations can be included in fig. 5, so a distinct bias for recording movement which occurred in conditions when birds flew low must result. However, as most of the recorded radar movements were within the peak periods, it would seem that high-level movement was also occurring at the same time.

( 6 ) NUMBERS ABNORMALLY PRESENT OR ABSENT In an attempt to discover the status of birds in Britain during the hard winter, a section on the questionnaire requested observers to indicate whether a species was more common or less common in their areas during the period in question. This yielded a mass of data, which has served two major purposes. Firstly, it has confirmed indirectly the information on passage, showing that large-scale movements into and

*This is radically different from the method adopted in I.O.P. analyses, but seems to be most suitable here.

387

BRITISH BIRDS

out of the country did occur, and it has helped considerably to widen and consolidate our findings about these movements. Secondly, it has served to show the fate of those birds which did not emigrate: how they congregated in towns and on open water, sewage farms and spoil heaps, and when and where they disappeared, due to death or late departure.

The interpretation of these data involved several problems. One was whether reports of absence in fact indicated the death or the departure, or both, of the species concerned. In many cases, it was possible to infer the meaning from other data. For example, widespread reports of absence of Lapwings from late December onwards were accompanied by observations of large Lapwing movements west and south-west, and large increases in south-west England and Ireland. Few Lapwings were found dead over the country which they had vacated, but heavy mortality subsequently occurred in south-west England and Ireland.

In many cases, however, a clear inference of this nature is not possible. Lapwings are large birds with obvious corpses which take some time to disintegrate. Discussion in section 7 makes it clear that little reliance can be placed on finding corpses of smaller species. Some species, such as tits, Yellowhammers and Reed Buntings, became unusually frequent in towns, thus accounting for widespread reports of absence from rural areas. In the cases of other species, however, absence from large areas could not be explained in terms of movement: these were small birds whose corpses would disappear rapidly and their absence during the winter probably reflected very heavy mortality.

Nevertheless, such species as Long-tailed Tits, Treecreepers, Gold-crests and, in particular, Wrens, although they dropped heavily in breeding strength, disappeared even more completely during the winter. There is a suggestion (section 15) that their troglodyte habits may have hidden Wrens from view and it may be that some of these other small birds merely became very sluggish and retiring, and consequently difficult to observe. Again, although there is no suggestion of any movement, emigration may have occurred, particularly in the case of Goldcrests. There is, in fact, no fully satisfactory explanation to date for the sudden re-appearance in reduced numbers of these species during March and April.

The conclusions drawn from the data are included in the systematic list (section 15); species are not included when the evidence on movement is slender (less than ten records). In some cases, numbers of reports are quoted in order to give some idea of the scale of unusual presence or absence. This has two major snags. Firstly, no indication of the scale of influx or decrease is given: anything from observations of none to a decrease counts as 'abnormally absent'. Secondly,

388

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF I 9 6 2 / 6 3

observers reported normal numbers so erratically that no account could be taken of the results and the scale of abundance or scarcity created by reports quoted is thus prejudiced towards over-estimation in one direction or the other. Only in the cases of a few species, such as those already cited, is an almost total lack of observations during the winter an assured fact. Others may bear an approximation to the

F I G . 6. Proportions of birds found dead in the British Isles month by month from November 1962 to March 1963. The 'total' section covers all species and not only the groups analysed separately; 'water birds' include divers, grebes, ducks, geese and swans, while 'rails' cover the Water Rail, Moorhen and Coot {drawn by A. J.

Richards)

389

BRITISH BIRDS

degree of absence or abundance with reference to the reports quoted, but this must be of a qualitative rather than a quantitative nature.

( 7 ) BIRDS FOUND DEAD Perhaps the most dramatic evidence of the effects of a hard winter are the number of birds found dead. In the winter of 1962/63 observers reported to us a total of over 15,000 corpses that were counted, besides a further 81 reports of 'many' corpses and n o reports of 'a few' or 'several'. In addition, Ash (1964) examined and weighed 332 dead birds of 46 species, and also discussed the races of some of these.

The histograms in fig. 6 illustrate the monthly variation of the mortality for different groups of species, while table 2 gives the totals for each species. The composite picture is of heavy mortality in both January and February. As observers were probably more active in February and many of the corpses counted were fairly old, it would seem that slightly more than half the mortality may have occurred in January. (The figures for March probably relate very largely to corpses found then but lying for several weeks previously.)

Coots, Moorhens and thrushes seem to have been the first to die. In their cases the heaviest mortality was in January. Woodpigeons and Starlings also suffered more losses in January than later; and Oyster-catchers and Lapwings were succumbing then, ahead of the other waders.

However, the mortality of wildfowl seems to have been later. For this group, roughly two-thirds of the corpses found were in February. The rivers and larger areas of standing water had taken some time to freeze over and perhaps wildfowl are somewhat hardier than smaller birds. Another group that only suffered late were the gulls: there was a marked February peak and a large proportion were found in March. Here again the slow freezing of the foreshore presumably allowed longer survival, and there was plenty of opportunity for scavenging (Crisp 1964). It is not clear, in fact, why they succumbed as much as they did.

The list in table 2 includes most of the common birds present during the winter, and so it is interesting to see which species are missing. The most important are probably Lesser Black-backed Gull, Jay, Nuthatch, Treecreeper, Coal Tit, Marsh Tit, Long-tailed Tit, Gold-crest, Redpoll, Crossbill and Tree Sparrow. In the cases of the Tree-creeper and Goldcrest, and to a lesser extent the tits, their small size may have meant that dead birds were not found*; however corpses of other small birds were found, including those of Grey Wagtails and Linnets which would not normally be near human habitation. Lesser Black-backed Gulls probably emigrated. For the other species in this category, however, mortality may have been slight.

*One Goldcrest was found dead according to a report in the Western Morning News.

390

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

Table 2. Birds found dead in Britain, November 1962-March 1963

Black-throated Diver Great Northern Diver Red-throated Diver Great Crested Grebe Red-necked Grebe Slavonian Grebe Black-necked Grebe Little Grebe Great Shearwater Fulmar Gannet Cormorant Shag Heron Bittern Mallard Teal Wigeon Pintail Shoveler Scaup Tufted Duck Pochard Goldeneye Velvet Scoter Common Scoter Eider Red-breasted Merganser Goosander Smew Shelduck Grey Lag Goose White-fronted Goose Bean Goose Pink-footed Goose Brent Goose Canada Goose Mute Swan Whooper Swan Bewick's Swan Buzzard Kestrel Red Grouse Partridge Water Rail Moorhen Coot Oystercatcher Lapwing

Total records Nov Dec

9 5

2 1

2 3

9 1

1

1 1

1

1 0

1 1

7 1

2 4

1 1

3 0

1 3

2 5

5 3 9

2 0

9 5 6

1 9

8 6 7 3

38 1

5 1

1

6 2

4 0

7 2

3 4 2

6 1 9

4 2

45 33 53

1

1

1

2

3

1

1

6

1 4

1

8

Jan

1

1

2 0

4 0

5

2

2

2

2

1 0

5 51

7 35

2

1

3 2

3 4 6

1 4

8 1

4 2

1 2 6

2 2

5

3

37 2

2

1 3

'34 2 6 0

3 1 2

304

Feb

2 2

3 97

" 3 8 1

1

6 1

1 4

1 7

3

1 1

3 64 8

1 3 2

5 3

16 34 7 2

2 7

1 0 8

2 8

6 3

4 1 2

2

1 0

2

2 2

65 3 2

3 2

3 T3 76

154 69

1 1 4

Bodies Mar Undated counted

1

1

34 38

5

1 5

7 2

1

1

7 2

15 1

1

6 16

1

3 13 3 1

3 1

89

1

1 0

3

1

1

1

1

16 17 26

1 6 0

1

1

I

4

1

1

2 0

2

3 6

2 2

4 1

1

3 0

77

2

2

1 4

1

J7

1

J5 7i

"73 373 297

25 6

1 5 2

196 13

1

1

1 4

1

31

2 7

7 1

4 2

1 2

1 2 7

23 2 0 7

8 4

2 7

83 1 2

7 36

165 4 0

8 1 0

3 7 1 0

2

34 5 2

26 2

1 3 1

9 J9 4 5 3 3

4 2

297 604 780 883

Estimates Few Sev Many

1

1

1 1

1

1

2 1

1 1

4 2

1 3 1 2 1 2

2 1 5

391

BRITISH BIRDS

Ringed Plovet Grey Plover Golden Plover Turnstone Snipe Jack Snipe Woodcock Curlew Black-tailed Godwit Bar-tailed Godwit Green Sandpiper Redshank Greenshank Knot Purple Sandpiper Dunlin Sanderling Great Skua Great Black-backed

Gull Herring Gull Common Gull Glaucous Gull Black-headed Gull Kittiwake Razorbill Guillemot Puffin Stock Dove Rock Dove Woodpigeon Barn Owl Little Owl Tawny Owl Short-eared Owl Kingfisher Green Woodpecker Great Spotted

Woodpecker Lesser Spotted

Woodpecker Skylark Raven Carrion Crow Rook Jackdaw Magpie Chough Great Tit Blue Tit Wren

Total records Nov Dec Jan

7

7

14 6

2 2

3

39

4 4

5 8

1

36 2

2 0

1

2 2

1

1

7

25 30

1

39 8

2 2

2 0

1

2

1

6 9

14

9 1

1

1

1 0

3

1

27 1

9 1 1

5

3

3

7 1 2

18

6

1

3

3

1

2 9

2 13

2

6 5

1

1

1

1

2

1

1

3

15 1 2

18

2

4 4

87

5 6

1 3 0

7

34

34

1

3 1

63

1 4 0

33 69

1

1

2 6 2

7 6

5

1

28

2

2

1

2

2

6

1 2

1i

Feb

3 2 0

9 2

2 2

3^5 184

8

!5 1

3 8 0

5 1 2 2

59 1

1

42

6 4

! 7 3

1 9 4

2 1

4 6 J 3 5

2 2 6

3 1

1

2

2

13

3 6

1 1

8

1

3. 1

7 8

Bodies Mar Undated counted

8

3

9 65

1

58

6

6

5 1 0

36

1

96

1 2

18

1

77 1

1

2

I

*9

1

2

1

1

1

2

M

5 2 1

29

15

238

177

5

53

4 9

3 6 6

1

18

28

1 0 0

1

4 2

1

3, J73 2 1

2 4

2

1

1

9

18

28

53

4 9

59 2

6 0 9

516 J 3 2 7

1

6 2 1

1 2

2 1 1

3 166

1

1

49 I 2 3

3 " 1

545 2 2

95 2 2 6

1

2

1

3.749 32

8

1

1

2

8

2

1

85

3 1 0

15 1 1

3 6

1 0

23

35

Estimates Few

1

1

2

1

1

5 1

2

1

2

2

2

3

Sev Many

1

2

2

3 1

5

1 4

3

1

1

2 15

1

1

1

1

3

1 1

392

E F F E C T S O F T H E S E V E R E W I N T E R O F 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

Mistle Thrush Fieldfare Song Thrush Redwing Blackbird Stonechat Robin Dunnock Meadow Pipit Rock Pipit Pied Wagtail Grey Wagtail Starling Hawfinch Greenfinch Goldfinch Linnet Twite Bullfinch Chaffinch Brambling Yellowhammer Corn Bunting Reed Bunting House Sparrow

Totals

Total records Nov

n 38 52

77 62

2

13 6

1 5

3 7 2

49 1

8 1

5 1

1

16

3 2

1

3 I I

1,613

2

I

3 1

2 2

Dec

1

7 7

12

I I

2

3

5

2

I

126

Jan

7 43 5i

382

65

1 0

2

7 1

3 1

416

1 2

1

23 1

1

2

3.594

Feb

1

36 66

227 36

1

3 7 4 1

1

168 1

2 2

1

14 1 1

4

4,408

Bodies Mar Undated counted

4 29

17 30 26

3

2

208

8

M75

2

60

75 121

60 1

2

6

6

536

3

2

4 1

1

1

6,083

IJ 177 217

775 199

1

16

7 25

5 10

2

i ,333 1

37 0

3 0

1

43 3 1

1

2

15

15,508

Estimates Few

2

4 5 5 1

3 1

1

1

9

1

3 1

1

1

5

78

Sev

1

3

I

I

32

Many

3 4 9 6

1

1

1

5

1

1

81

At the other extreme, we can short-list the species of which most corpses were found. Neither the total of records nor the total of corpses is satisfactory in its own right, and so this list is confined to species of which at least ioo individuals were found dead and of which there were at least 20 reports of casualties—indicating, therefore, fairly widespread mortality on a considerable scale. The species concerned are:

Red-throated Diver Great Crested Grebe Mallard Wigeon Shelduck Mute Swan Moorhen Coot

Oystercatcher Lapwing Woodcock Curlew Redshank Knot Dunlin Herring Gull Common Gull

Black-headed Gull Guillemot Woodpigeon Fieldfare Song Thrush Redwing Blackbird Starling

The three species which seem to have been most affected are the Wood-pigeon, Starling and Redwing in that order, though no allowance has been made for bias.

393

BRITISH BIRDS

Boyd (1964) found that for 24 wildfowl species there was a strong association between specific abundance and numbers found dead. Unfortunately there is no good evidence yet of the specific abundance of species other than wildfowl and so it is impossible to make the same calculation for them; but it would seem likely that a similar situation held good for the waders (except Woodcock and Snipe), though not for the passerines. In severe conditions almost all wildfowl and waders are deprived of their food sources, while most passerines are often still able to find food quite apart from the supplies offered by man.

Another striking point in table 2 is the discrepancy between species we might expect to be similar. Only 59 dead Snipe were found, but no less than 609 dead Woodcock; the lack of Snipe is especially noticeable as most waders seem to have been found dead in approximate order of specific abundance. Tawny Owls (with only one casualty reported) fared notably better than Barn and l i t t le Owls (with 14 and nine records of 32 and 8 + individuals respectively). Green Woodpeckers were also found dead more often than Great and Lesser Spotted. On the other hand, the numbers of corpses of thrushes seemed to reflect the relative hardiness and abundance of the various species: only eleven records of Mistle Thrushes (15 birds) compared with 52 of Song Thrushes (217 birds), and only 38 records of Fieldfares (177 birds) compared with 77 of Redwings (775 birds). Similarly, while the totals of records of dead Moorhens and Coots were similar (42 and 45), the average numbers of individuals in each count were 8.2 and 15.1 respectively, thus reflecting the greater gregariousness of the Coot.

The distribution of the records of birds found dead is shown in fig. 2 on page 375. Coastal counts were probably increased by oiling.

The species that topped the list of corpses were not the same as those whose breeding levels fell most, presumably because many of the birds found dead were immigrants while our own populations of the same species may have survived better elsewhere; but it is important to recognise the limitations of such data which may be biased in several ways. Firstly, it is much easier—and consequently more interesting— to count the dead birds along a mile of foreshore than over a hundred acres of farmland or ten acres of woodland, and so a large proportion of the counting effort was spent on the coast with a consequent inflation of the numbers there. Secondly, it may be that some corpses are more palatable to predators than others; we have observed on Cape Clear, Co. Cork, that dead Lapwings lie with meat still on the bones long after almost all other corpses have been cleared, which suggests that they are not sought by scavengers. Thirdly, whether there is a difference in palatibility or not, the activity of scavengers is great and may seriously deplete the numbers of corpses found, especially of small

394

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

birds. * Fourthly, it is of course much easier to find the corpse of a large and conspicuous species than that of a small passerine.

Nevertheless, our list of dead birds is clear evidence of great mortality during the winter. A proportion of these would have died anyway—some in any frost, others because they were oiled, and others still through disease, predation or accident—but this 'normal' mortality would have been unlikely to produce such numbers of corpses; the totals in January, February and March would probably have been little more than those in November and December.

Evidence from ringing recoveries Further evidence of the heavy mortality was provided by a sudden spate of recoveries of ringed birds. The numbers reported to the B.T.O. Ringing Office reached an all-time peak in January and February, and were far above what might otherwise have been expected even allowing for the constant growth of ringing. After these two months, however, the numbers of recoveries fell and for the rest of the year were below the recent average; this was probably due to a combination of a lower population level and a higher survival rate of those still alive (Robert Spencer in lift.). Coulson (1961) has pointed out that, amongst suburban birds at least, there is usually a high mortality of adults during the breeding season. If this was lessened in 1963, it may have contributed considerably towards a recovery to normal numbers.

Robert Spencer is preparing a table showing the numbers of each species recovered in each month of 1963, which will be published later in this journal in the 'Report on bird-ringing for 1963'. For some species, however, the total recovered in January and February exceeded that for the whole of the previous year, and in such cases the numbers concerned are quoted here in section 15.

( 8 ) LESS USUAL FOODS Following the precedent of previous enquiries of this sort, the questionnaire included a section about the taking of abnormal foods. For some species, however, it seemed that 'anything that could be eaten was eaten'. This might lead one to the conclusion that it was pointless to pursue the discussion further, since the reports received are bound not to be representative in any case. Nevertheless, there is a broader aspect to this matter, which justifies further attention.

Firstly, it was onlv certain species that were adaptable enough to

*The only real evidence of this known to us is an experiment by C. A. Norris, who placed 20 dead House Sparrows at intervals of ten yards across rough grass, lawn and a well-grazed paddock at 11 p.m. one night in October 1962. At about 8.30 a.m. next day all but three of the corpses had disappeared, in most cases without so much as a single feather remaining to indicate the places where they had lain.

395

BRITISH BIRDS

take unusual foods, and some of those most severely hit were never observed doing so. The latter include the Little Grebe, Kingfisher, Wren, Stonechat and Dartford Warbler (great would have been the surprise, no doubt, of an observer who had any of these appear on his bird-table; but some unusual species did come into gardens, and gardens were not the only places where unusual foods were taken). Other species which were badly affected, such as the Heron, Lapwing, Green Woodpecker, Goldcrest and Grey Wagtail, were only occasionally seen taking unusual foods; and Mistle and Song Thrushes seem to have taken fewer strange foods than the other thrushes (though Redwings were hard hit in spite of their greater adaptability). The two lists in this paragraph in fact account for a large proportion of the species that were definitely reduced by the winter.

Secondly, there is evidence that when a new food habit has been learnt by a few individuals, it will spread quickly through most of the species. The opening of milk-bottles is the classic example of this (Fisher and Hinde 1949), while the appearance of Great Spotted Woodpeckers at bird-tables is something which has probably developed since the 1946/47 hard winter (Upton 1962) and may have had positive survival value this time. Grey Lag Geese began eating swedes during the 1946/47 winter and have continued to do so ever since in one part of Scotland (Kear 1962). One effect of a severe winter may therefore be to cause birds to discover new food supplies which they can then utilise afterwards, and in some cases this could help an eventual increase in numbers. The winter of 1962/63 may perhaps have done this for some species and, slender though the evidence is, attention might profitably be paid now to Reed Buntings, which were already beginning to acquire the habit of visiting gardens well away from water and did so on a much larger scale during the severe weather (reports direct and Ferguson-Lees 1963, Armitage 1964); Kent (1964) also discussed a possible change in the habitat of this species.

Thirdly, the birds of this country are undoubtedly affected by man's (and especially woman's) charity at such times. This, as we have seen above, allows the bolder and more adaptable species to thrive, while the more timid suffer 'naturally'; in consequence, there is an artificial 'unbalance' in our avifauna. Such feeding may not always be beneficial, however, and Kettlewell (1963) has pointed out that a temporary break in it may cause heavy mortality.

A considerable proportion of the records involved unusual visitors to bird-tables, doorways and window-ledges. Apart from the species which regularly come close to habitation, the following were recorded. Red Grouse approached as far as the hens on a farm, which they joined for meals (while a Moorhen accepted the hens' hospitality and roosted in a shed with them). Water Rails, Lapwings, Curlews, Knot and Woodcock were all bold enough to get as far as gardens, and Partridges

396

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

fed underneath bird-tables. Little Owls and Kestrels came to tables for food that was not intended to be provided—namely, the other birds feeding there—and there is also a record of both species taking hanging fat. The list of the boldest, that actually came on to bird-tables, is much longer and includes Snipe, Moorhen, Stock Dove, Herring Gull, Common Gull, Black-headed Gull, Green Woodpecker, Great Spotted Woodpecker, Skylark, Carrion Crow, Rook, Jackdaw, Magpie, Treecreeper, Mistle Thrush, Fieldfare, Meadow Pipit, Grey Wagtail, Siskin and Snow Bunting.

At least 90 species were recorded taking food that was thought to be unusual, but lack of space unfortunately prevents us from giving much detail here, especially since the foods involved were very varied. General kitchen scraps accounted for a great number of the records, however, and also apples, which were in great abundance. The latter are, of course, a regular food of Fieldfares, Mistle Thrushes, Redwings, Blackbirds and, to a lesser extent, Song Thrushes and Starlings (plate 60 shows some of these species feeding in this way), but other birds which turned to them on occasion during the 1962/63 winter included Teal, Green Woodpecker, Woodpigeon, Great Tit and Blue Tit. 'Swoop', the now well-known mixture of various seeds and other foods specially prepared for wild birds, was widely used and, besides the species which regularly feed on it, was eaten by Knot, Skylark, Redwing, Brambling, Reed Bunting and Yellowhammer. There were also curious records of Skylarks eating brussels sprouts (L. G. Weller) and broccoli (T. B. Silcocks).

Normal foods for some species were probably in good supply. 1962 seems to have been a good year for beechmast and acorns, and the 'Partis tits should have been able to hoard food and later find it again (Dr. C. M. Perrins and T. Royama). However, although Ash (1964) stated that there was a great abundance of natural foods, it does seem that this was somewhat local. Sixty-five observers reported on the berry crop and, of these, 31 said berries were scarce (five reported they were all taken in November and 13 more that they had gone by the end of December). Probably the large numbers of Redwings which came into the country in November helped to clear the berries faster than usual, and then the cold weather meant that those that were left were stripped by the end of Januarv.

Published references to food taken in the period record Brent Geese picking weed from the undersides of ice-floes (Crawshaw 1963), Song Thrushes taking periwinkles (reports direct, and Hope Jones 1964, Hunt 1964, Stevens 1964), and gulls feeding on dead razor-shells Ensis (Ash 1964).

A few individuals showed a distinct taste for delicatessen. A Heron was seen eating some stale kippers, and a Redpoll picked the currants from a cake. A Robin also chose currants, though a Fieldfare prefer-

397

B R I T I S H B I R D S

red oranges and a Moorhen 'Kit-e-Kat'. But Redwings did best of the lot: among the items they took were tongue and cooked peas, rich tea biscuit and cheese.

( 9 ) CONDITION OF BIRDS DURING THE WINTER The questionnaire did not include a section about the condition of birds during the winter, and consequently we received little information. From various sources we have come across the usual tale of suffering: of birds which were too weak to feed dying on door-steps from the east coast of England to the southern tip of Ireland; of starving Woodpigeons stripping brassicas and dropping dead underneath ; and of a Blackbird eating the corpse of another Blackbird while it was still warm. Records such as these convey to us—perhaps too emotionally—the meaning of the winter for individual birds. But they are no more than the inevitable concomitant of conditions when mortality is heavy; they are, indeed, merely the process of dying.

Yet, while many birds suffered, others thrived. A species encountering severe weather and shortage of food needs some system whereby enough individuals die for the rest to survive. It is probable that those which survive need to put on weight in order to do so; there is evidence to show that birds regularly increase weight as the temperature falls (Baldwin and Kendeigh 1938) and the most probable explanation is that the fat serves as an insulating layer. Suggestions have been made that it also serves as a food reserve, but this is hardly likely to apply here as a bird's metabolism is so rapid that the supply would not normally outlast a day.

Ringers operating during the severe weather had abundant evidence of the good condition of many individuals. They were asked to trap only where birds were healthy and feeding actively, but in such places they often found weights greatly in excess of the normal winter maxima.

In particular, many Greenfinches were weighed. The average weight of 64 at a roost near Oxford on 21st January was as high as 33.4 grams, which is more than a gram above any monthly average in 1961 or 1964 (B. H. B. Dickinson and H. M. Dobinson). At Rye Meads, Hertfordshire, the average of 583 weighings in January 1963 was 32.2 grams, while the peak there was reached on 2nd February when seven averaged 34.3 grams; for comparison, the average in December 1962 was 29.7 grams (Lloyd-Evans and Nau 1964). Similarly, Greenfinch weights in Surrey were one to two grams up on the average for January and February (Dr. G. Beven).

Turning to other species, I. Newton found that Bullfinches near Oxford also averaged about one gram heavier than in the same period in 1964; he points out that this species was probably taking more food than usual in the hard weather, thus increasing population pressure (this information will be expanded in a paper which he is

398

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1962/63

preparing). The average weight of Blackbirds at a roost in the Oxford area in January 1963 was 119 grams compared with 117 grams in January 1964, while in February 1963 it was 117 grams compared with only 102 grams in February 1964 (B. H. B. Dickinson and H. M. Dobinson).

Otherwise, unfortunately, too few individuals of most species were caught for averages to be calculated, but maximum weights are still of interest, as some birds were extraordinarily heavy. Those we have heard of are shown in table 3 and compared with the mean dead weights quoted by Ash (1964) for the same period. All the records in this table are more than 2 5 % heavier than the normal weight for the species concerned, so far as this is known.

Table 3. Maximum weights of some birds trapped in Britain during January and February 1963, compared where possible with mean dead weights quoted

by Ash (1964) All weights are in grams. Those marked with an asterisk have been expressed as decimals for the sake of uniformity, although the figures concerned were taken to the

nearest half-gram

Skylark

Fieldfare Mistle Thrush Song Thrush

Blackbird

Robin Dunnock Greenfinch

Redpoll Chaffinch Bullfinch Brambling Corn Bunting Tree Sparrow

Locality

Rye Meads, Hertfordshire Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire Bidston, Cheshire Dungeness, Kent Malltraeth, Anglesey Bagley Wood, Berkshire Malltraeth, Anglesey Malltraeth, Anglesey Rye Meads, Hertfordshire Bagley Wood, Berkshire Leicester Reading, Berkshire Reading, Berkshire Wytham, Oxfordshire Bookham, Surrey Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire Dungeness, Kent Newcastle under Lyme, Staffordshire

Maximum weight

56.0 55.8

131.5 147.0* 91.0 93.0*

141.0* 137.0*

25-5 28.0* 40.0 39.0 13.8 29.5* 26.7

34-3 65.0 24.9 23.7

Mean dead

}

} \

s

}

}

weight

25-7

-72.0

47-9

64.3

13.9 16.3

18.1

-16.7

-18.2

-

Dr. G. Beven in Surrey trapped 20 birds of various species twice within the hard weather period: eight put on weight, nine maintained it and only three lost any. Increases in weight of birds caught twice during the cold weather have also been quoted by Hope Jones (1964).

( i o ) COMPARISON OF BREEDING STRENGTH Table 4 gives, species by species, the total number of reports that we received of breeding strength in 1963 compared with 1962. It also

399

BRITISH BIRDS

assesses the general change in breeding strength in terms of our categories. It must be emphasised that this is no more than a rough guide—the data we have worked on is not entirely quantitative and there are too many other variable factors, such as locality and habitat—• but it is thought that, if species are to be compared, it is best to resolve the separate categories into some form of composite total.*

An attempt at a quantitative figure is being prepared by Kenneth Williamson for publication in Bird Study. This will be based on a comparison of 49 farmland areas scattered over the country, and therefore likewise subject to regional and ecological differences. Nearly half of these 49 observers also sent their records to us, and these are included in the table here.

It will be seen that the 23 species worst hit (composite categories A, AB or B, and at least three records) include ten species that depend on water or moist ground for feeding (Little Grebe, Heron, Bittern, Water Rail, Lapwing, Snipe, Redshank, Dunlin, Kingfisher and Grey Wagtail). The list also includes our two smallest birds (Wren and Gold-crest) and two species never strongly established in Britain (Bearded Tit and Dartford Warbler). Eight of the remaining nine are commonly affected by hard weather (Barn Owl, Short-eared Owl, Green Woodpecker, Woodlark, Long-tailed Tit, Treecreeper, Stonechat and Pied Wagtail).

The nine species most severely affected appear from our records to be the Kingfisher, Grey Wagtail, Goldcrest, Stonechat, Wren, Barn Owl, Snipe, Long-tailed Tit and Green Woodpecker in that order, but the Water Rail, Little Grebe and Woodlark should possibly be included with them. The Wren is so often thought of as the species that suffers most that it is interesting to find it taking only fifth place in the list.

Of the 23 species most affected, seven are mentioned by Voous (i960) as being commonly hit by hard winters, twelve are near the northern limit of their range in Europe and 20 are more or less sedentary in Britain. Of the seven other species which are near their northern limit in Britain, we have good data for only two: one of these, the Great Crested Grebe, was somewhat reduced, while the other, the Goldfinch, is always partially migratory and seems to have emigrated almost completely in 1962/63.

Species apparently not adversely affected bv the weather include three, the Mallard, Buzzard and Blackbird, which were reported as suffering decreases abroad (section 12), though the number of Nest Record Cards received for the Mallard and Blackbird fell considerably (section 11). Oystercatchers were surprisingly unaffected, although 780 were found dead. Also seeminglv unaffected were the Rook, Jay, Nuthatch, Dunnock, Greenfinch, Bullfinch and Yellowhammer.

*This has been done by weighting the categories as follows: A, —4; AB, — }; B, - 2 ; BC, - 1 ; C, o; and D, + 2.

400

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

Table 4. Breeding strength of birds in Britain in 1963 expressed as a comparison with 1962

A = exterminated, AB=reduction by about 95%, B=large decrease, BC=small decrease, C—little or no change, and D=increase. Species with records of particular interest are discussed in section 15, while those which do not appear there

are italicised here

Black-throated Diver Great Crested Grebe Little Grebe Heron Bittern Mallard Teal Gadwall Wigeon Pintail Shoveler Tufted Duck Pochard Red-breasted Merganser Goosander Shelduck Grey Lag Goose Canada Goose Mute Swan Buzzard Sparrowhawk Merlin Kestrel Red Grouse Black Grouse Red-legged Partridge Partridge Water Rail Moorhen Coot Oystercatcher Lapwing Ringed Plover Golden Plover Snipe Woodcock Curlew Redshank Dunlin Great Black-backed Gull Lesser Black-backed Gull Herring Gull Common Gull Black-headed Gull Stock Dove

A AB

1

7 3 1

2

1

2

1

3

7

1

1 1

7 2 2

6 1

1

8 1 1

3 2

1

/

3

B

8 6

2 1

6 4

1

7

7

1

7

1

4

5 3

6 1

} 1 0

6 36 2 2

3 5° 3 1

2 1

6 15 2 1

3 / 7

1

3 7

BC

3

2

1

4

2

1

4 I

3 1

1

5 4

3

1

1

1

. 4

3

C

1

6 7 8

1

35 6 7

1

2

5 3 2

5 7

2

17

7 i 1

2 0

2

7

<f 24

30

17 1 2

18

4 2

5 1 0

2 1

4 2

i 7

7 7

1 9

D

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

2

2

3 1

1

3

1

2

1

1

1

2

4

Total records

/ 2 0

2 0

34 3

47 1 0

1

2

1

7 8 4 } 1

13 7

4 28

1 1

4 1

34 4 7

7 2

36 8

83 46 16

81

7 5

36 2 0

41

31 6 4 }

9 2

1 2

26

Composite category

C BC

B B B C

BC C

BC B

BC C C

BC B

BC C C

BC BC BC

C BC BC

C BC BC

B BC BC

C B

BC BC

B BC BC

B B

BC C C

BC C

BC

401

BRITISH BIRDS

Rock Dove Woodpigeon Collared Dove Barn Owl Little Owl Tawny Owl Long-eared Owl Short-eared Owl Kingfisher Green Woodpecker Great Spotted Woodpecker Lesser Spotted Woodpecker Woodhrk Skylark Raven Carrion Crow Hooded Crow Rook Jackdaw Magpie Jay Chough Great Tit Blue Tit Coal Tit Marsh Tit Willow Tit Long-tailed Tit Bearded Tit Nuthatch Treecreeper Wren Dipper Mistle Thrush Song Thrush Blackbird Stonechat Robin Dartford Warbler Goldcrest Dunnock Meadow Pipit Rock Pipit Pied Wagtail Grey Wagtail Starling Hawfinch Greenfinch Goldfinch Siskin Linnet Twite

A

i

8 4 I

3 ?6 14

5 3 3

1

3

4 2

6 1

1

26

1

15

47 3

1 0

7 2

2 1

9 1

43 3 2

16

2 4 1

1

4

AB

1

1

4 3

1

2

3 15

1

1

2

1

7

2

2

B

4 1

7 1 1

16

1

1

4 4 1

25

; 3

27 1

2

5 1

5 2

1

4 1

39 16

14 1

4 1

3 6

25 1 1 8

2

27 1 0 2

36 1 1

57 2

39 36 27

2

37 16

6 4

*9

! 9

i 26

4 0 2

BC

9

1

2

1

5 8

8 1

2

3 2

3

7 1 1

2

1

1

4

4 7 5 1

1 1

1 2

17

9 18

2

14

5 / 8

3

7 3

4

C

1

4 0

/ 5

1 1

2 0

1

8 34 10

3 52

8

43 3

3 i

33 37 ^7

1

56 64 27

27

15 J4

25 26

13 12

38 36 88

2

4 8

1

3 61

9 7

25 2

53 4

52

36

43 3

D

3 /

1

2

1

1

1

2

2

7

6 5 9 5 1

8 1 0

4 1

5 2

5 2

2

/ 2

1 2

2 0

5

'9 2

1

17

13

7

6

Total records

/ 94

2

2 2

3° 4 0

2

6 44 71

73 20

9 89 1 0

54 3

46 4 1

5 i 4 0

4 1 1 6

1 2 6

55 44 23 89

3 4 1

78 2 0 0

19 89

170

163

45 138

4 94

133

47 7 0

87 44 80

8 92

69 3

79 3

Composite category

C BC

D B

BC BC

C B A B

BC BC

B BC

C C C C C C C

BC BC BC BC BC

C B B C B B

BC BC BC

C AB BC

B AB

C BC BC

B AB

C BC

C BC

B BC

C

EFFECTS OF THE SEVERE WINTER OF 1 9 6 2 / 6 3

Redpoll Bullfinch Crossbill Chaffinch Yellowhammer Corn Bunting Cirl Bunting Reed Bunting House Sparrow Tree Sparrow

Summer visitors Totals

A

1

2

3 1

/

3

6

9 417

AB

1

1

1

0

54

B

2

1 2

38 19

2

I

17 3

1 1

26 1,388

BC

4

I I

5 2

5

6

8 288

C

9 41

5° 36

,r /

23 51

2 1

83 1,804

D

1 0

1 1

2

17 1 0

4 1

3 1 0

6

51 351

Total records

2 2

7i 2

119

71 'J 7

5i 65 51

177 4,30 2

Composite category

C C D

BC C C C

BC C

BC

_ -

Numbers of some species probably increased slightly, notably of the Carrion Crow, Jackdaw, Magpie, Starling, Redpoll and House Sparrow.

Many of the commonest species belong in the group whose subsequent breeding strength was only slightly affected by the weather. These include the Great Crested Grebe, Mute Swan, Kestrel, Moorhen, Coot, Curlew, Woodpigeon, Little Owl, Tawny Owl, Great and Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers, Skylark, Great, Blue, Coal and Marsh Tits, Mistle and Song Thrushes, Robin, Meadow Pipit, Goldfinch, Linnet, Chaffinch, Reed Bunting and Tree Sparrow.

The temporary absence of a large proportion of our own avifauna and the heavy mortality in Britain had made ornithologists and the public at large greatly aware of the effects on bird life, and apprehensive of the reduction in breeding numbers that might result. Towards the end of the hard weather, many newspapers carried reports on this, the majority of them responsible and well-informed and usually written by ornithologists. A good assessment was commonly made of the species most hit, with the comment that numbers would quickly return to normal; but we are unable to agree with James Fisher's view, published in the Sunday Times on 24th February 1963 and then repeated (without acknowledgement) in at least five other newspapers, that 'it seems likely that at least half the wild birds living in the country before last Christmas are now dead'.

( i l ) NEST RECORD CARDS AS EVIDENCE

OF BREEDING STRENGTH Figures for the number of Nest Record Cards completed during 1965 have been supplied most kindly by H. Mayer-Gross, with the permission of the British Trust for Ornithology, and have been compared with the totals for 1962.

403

B R I T I S H B I R D S

Table 5. Numbers of B.T.O. Nest Record Cards for 17 species where the 1963 total was as low as a quarter to three-quarters of the 1962 one, suggesting a drop

in the population level

Wren Mistle Thrush Skylark Song Thrush Pied Wagtail Meadow Pipit Woodpigeon Lapwing Moorhen Reed Bunting Linnet Blackbird Mallard Dunnock Coot Robin Tree Sparrow

Total cards in 1962

I51

131 157

2,008 126

109

4 8 1

2 4 6

392

!35 733

3,'°9 120

8 0 4

105

287

3 5 0

Total cards in 1963

35 5? 64

8 5 2

54 5°

2 3 1

1 2 0

1 9 4

71 4 2 4

2,000

79 5 4 1

77 2 1 4

2 6 1

1963 total as percentage of 1962

23% 40% 4 i % 42% 43% 46% 48% 49% 49% 53% 58% 64% 66% 67% 73% 75% 75%

A total of 15,033 cards were sent in for 1962, but this figure fell to 10,229* f ° r 1963. The number of clubs and individual observers reporting nests has not changed greatly in recent years, and was 180 in both 1962 and 1963. The effort devoted to searching for nests of common species is not known to vary greatly, though the total number of nests reported for some of the less common species can be greatly altered by special investigations.

The number of clutches started by each pair of birds might vary from year to year and, as each clutch is recorded on a separate card, this could produce serious bias. H. Mayer-Gross (in litt.) considers that the finches and insectivores around Oxford had a more prolonged season in 1962 than in 1963, while the thrushes in that area made more attempts per pair in 1963.

Nevertheless, for all the limitations of the data, the numbers of cards received often varied so much from 1962 to 1963 that there can be no doubt that changes in the population level were partly responsible. T o illustrate this, table 5 lists 17 species for which more than 100 cards were submitted in 1962 and for which the 1963 total fell to 75% or less of the previous year's figure. It will be seen that nine of these 17 species had dropped to between half and three-quarters of the 1962 total, while the remainder were at levels between two-fifths and half with one (the Wren) as low as a quarter.