Brazilian Journal of - ANESTHESIOLOGY - Amazon S3

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Brazilian Journal of - ANESTHESIOLOGY - Amazon S3

Contact us

[email protected] www.bjan-sba.org +55 21 979 770 024

Brazilian Journal ofA n e s t h e s i o l o g y

BJAN Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology

Vol. 71 N. 3 | M

ay-Jun

2021

Brazilian Journal ofANESTHESIOLOGYR e v i s t a B r a s i l e i r a d e A n e s t e s i o l o g i a

Obstetric anesthesia

Vol. 71, N. 3 | May-Jun 2021 | ISSN 0104-0014

M.S.: 1.0497.1449

Broad range of packaging content sizesAppropriate for every kind of procedure

Short-acting sedation withrapid and safe patient recovery

Packaging content sizes appropriate for all anesthesia steps, from induction to maintenance

Reference: 1. Drug package insert.

For further information, scan the QR Code.

The Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia/Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology (BJAN) is the official journal of Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia (SBA). The BJAN only accepts original articles for publication that can be submitted in English or Portuguese, and are published in English. Before submitting a manuscript, authors must read carefully the Instructions to Authors. It can be found at: <https://bjan-sba.org/instructions>Manuscripts must be submitted electronically via the Journal’s online submission system <http://www.editorialmanager.com/bjan>.

The BJAN publishes original work in all areas of anesthesia, surgical critical care, perioperative medicine and pain medicine, including basic, translational and clinical research, as well as education and technological innovation. In addition, the Journal publishes review articles, relevant case reports, pictorial essays or contextualized images, special articles, correspondence, and letters to the editor. Special articles such as guidelines and historical manuscripts are published upon invitation only, and authors should seek subject approval by the Editorial Office before submission.

The BJAN accepts only original articles that are not under consideration by any other journal and that have not been published before, except as academic theses or abstracts presented at conferences or meetings. A cloud-based intuitive platform is used to compare submitted manuscripts to previous publications, and submissions must not contain any instances of plagiarism. Authors must obtain and send the Editorial Office all required permissions for any overlapping material and properly identify them in the manuscript to avoid plagiarism.

All articles submitted for publication are assessed by two or more members of the Editorial Board or external peer reviewers, assigned at the discretion of the Editor- in-chief or the Associate editors.Published articles are a property of Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia, and their total ou partial reproduction can be made with previous authorization. The BJAN assumes no responsibility for the opinions expressed in the signed works.

Edited by | Editada por Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia (SBA)Rua Prof. Alfredo Gomes, 36, Rio de Janeiro/RJ, Brazil – CEP 22251-080Telefone: +55 21 3528-1050E-mail: [email protected]

Published by | Publicada porElsevier Editora Ltda.Telefone RJ: +55 21 3970-9300Telefone SP: +55 11 5105-8555www.elsevier.comISSN: 0104-0014 © 2021 Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia. Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. All rights reserved.

Editor-in-Chief Maria José Carvalho Carmona – Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Co-Editor André Prato Schmidt – Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, RS, Brazil

Associate Editors Ana Maria Menezes Caetano – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, BrazilCláudia Marquez Simões – Hospital Sírio Libanês, São Paulo, SP, BrazilFlorentino F. Mendes – Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, RS, BrazilGabriel Magalhães Nunes Guimarães – Universidade de Brasília, DF, BrazilGuilherme A.M. Barros – Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu da Universidade Estadual Paulista, SP, BrazilLeonardo Henrique Cunha Ferraro – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilLiana Maria Torres de Araújo Azi – Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, BA, BrazilLuciana Paula Cadore Stefani – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, RS, BrazilLuis Vicente Garcia – Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, BrazilLuiz Marcelo Sá Malbouisson – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilMarcello Fonseca Salgado-Filho – Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, BrazilNorma Sueli Pinheiro Módolo – Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu da Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, SP, BrazilPaulo do Nascimento Junior – Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu da Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, SP, BrazilRodrigo Leal Alves – Hospital São Rafael, Salvador, BA, BrazilVanessa Henriques Carvalho – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, SP, BrazilVinicius Caldeira Quintão – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, Brazil

Editorial Committee Adrian Alvarez – Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, BA, ArgentinaAdrian Gelb – University of California, San Francisco, CA, USAAlexandra Rezende Assad – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, BrazilAngela Maria de Sousa – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de MedicinaAntônio Carlos Aguiar Brandão – Universidade do Vale do Sapucaí, Pouso Alegre, MG, BrazilAugusto Key Takaschima – Serviços Integrados de Anestesiologia, Florianópolis, SC, BrazilBernd W. Böttiger – University Hospital of Cologne, Klinikum Köln, GermanyBobbie Jean Sweitzer – Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, USACarlos Galhardo Júnior – Instituto de Cardiologia, MS/RJ, BrazilCarlos Manuel Correia Rodrigues de Almeida – Hospital CUF Viseu, Viseu, PortugalCarolina Baeta Neves D. Ferreira – Hospital Moriah, São Paulo, SP, BrazilCátia Sousa Govêia – Universidade de Brasília, DF, BrazilCélio Gomes de Amorim – Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, MG, BrazilClarita Bandeira Margarido – Sunnybrook Health Sciences Care, Toronto, Ontário, CanadaClaudia Regina Fernandes – Universidade Federal do Ceará, CE, BrazilClyde Matava – The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontário, CanadaDavid Ferez – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilDeborah Culley – Harvard University, Boston, USADomingos Cicarelli – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da USP, SP, BrazilDurval Campos Kraychette – Universidade Federal da Bahia, BA, BrazilEdmundo Pereira de Souza Neto – Centre Hospitalier de Montauban, Tarn-et-Garonne, FranceEduardo Giroud Joaquim – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilEliane Cristina de Souza Soares – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, MG, BrazilEmery Brown – Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts USAEric Benedet Lineburger – Hospital São José, Criciúma, SC, BrazilErick Freitas Curi – Hospital Santa Rita, Vitória, ES, BrazilFabiana A. Penachi Bosco Ferreira – Universidade Federal de Goiás, GO, BrazilFábio Papa – University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, CanadaFátima Carneiro Fernandes – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, RJ, BrazilFederico Bilotta – Sapienza Università Di Roma, Rome, ItalyFelipe Chiodini – Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilFernando Abelha – Hospital de São João, Porto, PortugalFrederic Michard – MiCo, Consulting and Research, Denens, SwitzerlandGastão Duval Neto – Universidade Federal de Pelotas, RS, BrazilGiovanni Landoni – Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, ItalyGildásio de Oliveira Júnior – Alpert Medical School - Brown University, Providence, USA Giovanni Landoni – Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milano, ItalyHazem Adel Ashmawi – Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilIsmar Lima Cavalcanti – Hospital Geral de Nova Iguaçu, RJ, BrazilJean Jacques Rouby – Pierreand Marie Curie University, Paris, FranceJean Louis Teboul – Paris-Sud University, Paris, France

Jean Louis Vincent – Université Libre De Bruxelles, Brussels, BelgiumJoão Batista Santos Garcia – Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, MA, BrazilJoão Manoel da Silva Júnior – Hospital do Servidor Público, SP, BrazilJoão Paulo Jordão Pontes – Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, MG, BrazilJudymara Lauzi Gozzani – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilKurt Ruetzler – Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USALaszlo Vutskits – Geneva University Hospitals, Geneve, GE, SwitzerlandLeandro Gobbo Braz – Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu da Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, SP, BrazilLuciano Gattinoni – University of Göttingen, Göttingen, GermanyLeopoldo Muniz da Silva – Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu da Universidade Estadual Paulista, SP, BrazilLigia Andrade da S. Telles Mathias – Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, SP, BrazilLuiz Antônio Diego – Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, BrazilLuiz Fernando dos Reis Falcão – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilLuiz Marciano Cangiani – Hospital da Fundação Centro Médico Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil Marcelo Gama de Abreu – University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden, SN, GermanyMarcelo Luis Abramides Torres – Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilMárcio Matsumoto – Hospital Sírio Libanês, São Paulo, SP, BrazilMarcos Antônio Costa de Albuquerque – Universidade Federal de Sergipe, SE, BrazilMarcos Francisco Vidal Melo – Harvard University, Boston, MA, USAMaria Ângela Tardelli – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilMariana Fontes Lima Neville – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, SP, BrazilMário José da Conceição – Fundação Universidade Regional de Blumenau, SC, BrazilMassimiliano Sorbello – AOU Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele, Catania, ItalyMatheus Fachini Vane – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilMônica Maria Siaulys – Hospital e Maternidade Santa Joana, São Paulo, SP, BrazilNádia Maria da Conceição Duarte – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, BrazilNeuber Martins Fonseca – Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, MG, BrazilNicola Disma – Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Génova, ItalyOscar César Pires – Universidade de Taubaté, SP, BrazilPaolo Pelosi – Universita Degli Studi Di Genova, Genoa, LI, ItalyPaulo Alípio – Universidade Federal Fluminense, RJ, BrazilPedro Amorim – Centro Hospitalar e Universitário do Porto, PortugalPedro Francisco Brandão – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, ES, BrazilPedro Paulo Tanaka – Stanford University School of Medicine, California, USAPhilip Peng – University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, CanadaPriscilla Ferreira Neto – Instituto da Criança HCFMUSP, SP, BrazilRaffael Pereira Cezar Zamper – London Health Science Center, London, UKRajinder K. Mirakhur – Royal Hospital, Belfast, Northern Ireland, United KingdomRicardo Antônio Guimarães Barbosa – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilRicardo Vieira Carlos – Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, SP, BrazilRodrigo Lima – Queens University, Toronto, Ontário, Canadá Rogean Rodrigues Nunes – Hospital São Lucas, Fortaleza, CE, BrazilRonald Miller – University of California, San Francisco, CA, USASara Lúcia Ferreira Cavalcante – Hospital Geral do Inamps de Fortaleza, CE, BrazilThaís Cançado – Serviço de Anestesologia de Campo Grande, MS, BrazilWaynice Paula-Garcia – Universidade de São Paulo, BrazilWolnei Caumo – Universidade do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

Previous Editors-in-Chief Oscar Vasconcellos Ribeiro (1951-1957) Zairo Eira Garcia Vieira (1958-1964) Bento Mário Villamil Gonçalves (1965-1979) Masami Katayama (1980-1988) Antônio Leite Oliva Filho (1989-1994) Luiz Marciano Cangiani (1995-2003) Judymara Lauzi Gozzani (2004-2009) Mario José da Conceição (2010-2015) Maria Ângela Tardelli (2016-2018)

Editorial Office Managing Editor – Mel RibeiroCommunications and Marketing Coordinator – Felipe Eduardo Ramos BarbosaEditorial Assistant – Pedro SaldanhaLibrarian – Teresa LibórioTranslator – Emily Catapano

The Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology is indexed by Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS) since 1989, Excerpta Médica Database (EMBASE) since 1994, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO – Brasil) since 2002, MEDLINE since 2008,

Scopus since 2010 and Web of Science (SCIE - Science Citation Index Expanded) since 2011.

ISSN 0104-0014 • Volume 71 • Number 3 • May-June, 2021

ii Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology Vol. 71, N. 3, May–Jun, 2021

Editorial

205 Challenges in obstetric anesthesiaAna Maria M. Caetano, André P. Schmidt

Infographic

207 Epidural analgesia in the obese obstetric patientAna Maria M. Caetano, André P. Schmidt

Clinical Research

208 Association of postpartum depression and epidural analgesia in women during labor: an observational studyIpek Saadet Edipoglu, Duygu Demiroz Aslan

214 Epidural analgesia in the obese obstetric patient: a retrospective and comparative study with non-obese patients at a tertiary hospitalClaudia Cuesta González-Tascón, Elena Gredilla Díaz, Itsaso Losantos García

221 Effect of anesthetic technique on the quality of anesthesia recovery for abdominal histerectomy: a cross-observational studyDaniel de Carli, José Fernando Amaral Meletti, Rodrigo Pauperio Soares de Camargo, Larissa Schneider Gratacós, Victor Cristiano Ramos Gomes, Nicole Dutra Marques

228 Pain catastrophizing in daughters of women with fi bromyalgia: a case-control studyRégis Junior Muniz, Mariane Schäffer Castro, Jairo Alberto Dussán-Sarria, Wolnei Caumo, Andressa de Souza

233 Effect of ondansetron on spinal anesthesia-induced hypotension in non-obstetric surgeries: a randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled trialFabrício Tavares Mendonça, Luis Carlos Crepaldi Junior, Rafaela Carvalho Gersanti, Kamila Christine de Araújo

241 Effect of anesthesia induction on cerebral tissue oxygen saturation in hypertensive patients: an observational studyYasi Taşkaldıran, Özlem Şen, Tuğba Aşkın, Süheyla Ünver

247 Effect of preoperative oral liquid carbohydrate intake on blood glucose, fasting-thirst, and fatigue levels: a randomized controlled studyGökçen Aydın Akbuğa, Mürüvvet Başer

254 General anesthesia for emergency cesarean delivery: simulation-based evaluation of residentsJúlio Alberto Rodrigues Maldonado Teixeira, Cláudia Alves, Conceição Martins, Joana Carvalhas, Margarida Pereira

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology iiiVol. 71, N. 3, May–Jun, 2021

259 Intubating conditions and hemodynamic changes during awake fi beroptic intubation using fentanyl with ketamine versus dexmedetomidine for anticipated diffi cult airway: a randomized clinical trialAnil Kumar Verma, Shipra Verma, Amiya Kumar Barik, Vinay Kanaujia, Sangeeta Arya

265 Referral to immediate postoperative care in an intensive care unit from the perspective of anesthesiologists, surgeons, and intensive care physicians: a cross-sectional questionnaireJoão Manoel Silva Jr, Henrique Tadashi Katayama, Felipe Manuel Vasconcellos Lopes, Diogo Oliveira Toledo, Cristina Prata Amendola, Fernanda dos Santos Oliveira, Leusi Magda Romano Andraus, Maria José C. Carmona, Suzana Margareth Lobo, Luiz Marcelo Sá Malbouisson

Experimental Trials

271 Dose-related effects of dexmedetomidine on sepsis-initiated lung injury in ratsGülsüm Karabulut, Nurdan Bedirli, Nalan Akyürek, Emin Ümit Bağrıaçık

Case Reports

278 Thromboelastography as a point-of-care guide for spinal anesthesia in an eclamptic patient: a case reportVendhan Ramanujam, Usama Iqbal, Mary Im

281 Perioperative anesthesia management of a pregnant patient with central airway obstruction: a case reportKeevan Singh, Shenelle Balliram, Rachael Ramkissun

285 Ultrasound-guided quadratus lumborum block for surgical treatment of endometriosis: case reportIdelberto do Val Ribeiro-Junior, Luiz Gustavo Oliveira Brito, Maíra Rossmann-Machado, Rose Luce Gomes do Amaral, Angélica F.A. Braga, Vanessa Henriques Carvalho

288 Evaluation of the density spectral array in the Wada test: report of six casesSusana Pacreu, Esther Vilà, Luis Moltó, Rodrigo Rocamora, Juan Luis Fernández-Candil

292 Pulmonary embolism confounded with COVID-19 suspicion in a catatonic patient presenting to anesthesia for ECT: a case reportB. Naveen Naik, Nidhi Singh, Ashish S. Aditya, Aakriti Gupta, Nidhi Prabhakar, Sandeep Grover

295 Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of pneumocephalus associated with epidural block: case reportJoão Castedo, António Pedro Ferreira, Óscar Camacho

299 Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia for abdominoplasty and liposuction in Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy: case reportPlinio da Cunha Leal, Wildney Leite Lima, Eduardo José Silva Gomes de Oliveira, Caio Márcio Barros de Oliveira, Lyvia Maria Rodrigues de Sousa Gomes, Elizabeth Teixeira Noguera Servin, Ed Carlos Rey Moura

Letters to the Editor

302 Donning N95 respirator masks during COVID-19 pandemic: look before you leap!Anju Gupta, Ajisha Aravindan, Kapil Dev Soni

303 Occupational team safety in ECT practice and COVID-19Rujitika Mungmunpuntipantip, Viroj Wiwanitkit

304 Validation of the Surgical Outcome Risk Tool (SORT) in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgeryDimitrios E. Magouliotis, Athina Samara, Maria P. Fergadi, Dimitrios Symeonidis, Dimitris Zacharoulis

305 Airway management in obese patientsManuel Ángel Gómez-Ríos, David Gómez-Ríos, Zeping Xu, Antonio M. Esquinas

306 Medicinal cannabis: new challenges for the anesthesiologistIgor P. Saffi er, Claudia C.A. Palmeira

307 Regional analgesia technique for postoperative analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: have we hit the bull’s eye yet?Kartik Sonawane, Hrudini Dixit, J. Balavenkatasubramanian

309 Challenges of prototyping, developing, and using video laryngoscopes produced by inhouse manufacturing on 3D printersVictor Sampaio de Almeida, Vinicius Sampaio de Almeida, Guilherme Oliveira Campos

311 Reorganization of obstetric anesthesia services during the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown – experience from an Indian tertiary hospitalAnjuman Chander, Vighnesh Ashok, Vanita Suri

313 Perspectives on Pecs I block in breast surgeriesRaghuraman M. Sethuraman

iv Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology Vol. 71, N. 3, May–Jun, 2021

E

C

SvqGsy

(uGJrp(o

tahqRehva

g(woaiiiqo

adn

h©B

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 2021;71(3):205---206

DITORIAL

hallenges in obstetric anesthesia

itht

(tTrapo

cngqicuugsusag

pewdTal

ince the dawn of humanity, childbirth has taken place in aery painful way, being accepted as such even with biblicaluotes. One of them, possibly the best-known, appears inenesis, chapter 03, verse 16: ‘‘To the woman, He [God]aid: ‘I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in painou shall bring forth children’’’.

In October 1846, dentist William Thomas Green Morton1819---1868) successfully demonstrated the first anesthesiasing ether to remove a neck tumor at the Massachusettseneral Hospital in Boston. After this event, the obstetricianames Young Simpson (1811---1870) has used ether and chlo-oform as anesthesia for deliveries in Scotland, and similarlyroceeded John Snow (1813---1858) and Walter Channing1786---1876), respectively in England and the United Statesf America.

At that time, there was great religious and medical resis-ance to this innovation. However, in 1853, Queen Victoriasked John Snow to administer chloroform for the birth ofer eighth child. After this event, the technique becameuite popular, being known in England as ‘‘Anesthesia a laeine’’.1---5 These modalities of labor analgesia were consid-red the standard care for a long time until other techniquesave emerged, including the use of nitrous oxide,6 intra-enous opioids,7 ketamine,8,9 and, eventually, neuroaxialnesthesia for vaginal delivery.

In Brazil, the right to methods of pain relief during labor isuaranteed by law to all women in the Unified Health SystemSUS).10 Nevertheless, for many years, general anesthesiaas the technique of choice for both elective and emergencybstetric procedures. In the last 30 years, there has beenn overall increasing trend towards neuroaxial anesthesianstead of general anesthesia for obstetric women. Neuroax-al anesthesia has become the state-of-the-art essentiallyn all obstetric centers, reflecting the improvement in theuality of care for pregnant women, with many advantagesver the techniques previously used.11

Consensus has not always existed in scientific communitybout neuroaxial labor analgesia. Many controversies andoubts were raised regarding the effects of neuroaxial tech-iques for labor analgesia, especially regarding the potential

ewdt

ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.04.025 2021 Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. on behalf of Sociedade BrasilY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

ncrease in labor duration and the increase in instrumen-al delivery rates. Fortunately, most of these controversiesave been solved by solid scientific evidence, and neuroaxialechniques are currently widely used and accepted.12,13

In this issue of the Brazilian Journal of AnesthesiologyBJAN), three interesting studies may significantly con-ribute to the good practice of obstetric anesthesia.14---16

hose manuscripts have addressed exciting topics in obstet-ic anesthesia, including education strategies for futurenesthesiologists,14 the association of labor pain with post-artum depression,15 and the influence of obesity onbstetric anesthesia outcomes.16

General anaesthesia is mostly performed for emergencyesarean sections and due to a lack of time to administereuraxial anaesthesia.17 However, for most anaesthesiolo-ists, the clinical experience with general anaesthesia isuite low in the obstetric population. Notably, simulations a well-known modern teaching tool, which can greatlyontribute to the training in anesthesiology, especially innusual clinical circumstances. Hence, Teixeira et al.14 eval-ated the ability of anesthesiology residents to performeneral anesthesia for emergency cesarean section in a safeimulation environment. Although the performance eval-ation was satisfactory, authors have recommended thetandardization of simulation techniques in the obstetricrea in order to further improve the development of futureenerations of anesthesiologists.

Furthermore, Edipoglu et al.15 have demonstrated thatatients who underwent epidural analgesia for vaginal deliv-ry, when compared to those in which delivery occurredithout neuroaxial analgesia, displayed lower pain scoresuring labor and lower incidence of postpartum depression.his study has demonstrated the importance of a flawlessnesthetic care for women in labor in order to improveong-term postpartum outcomes.

Finally, González-Tascón et al.16 have retrospectively

valuated approximately one thousand obese obstetricomen who received neuraxial analgesia for labor andelivery, focusing on outcomes related to the neuroaxialechniques and their success rate. Remarkably, the authorseira de Anestesiologia. This is an open access article under the CC.

TORI

oftoprtlo

latitsilo

C

T

R

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

Brazil

∗

EDI

bserved a greater number of puncture attempts to per-orm neuroaxial anesthesia and a surprising increase inhe cesarean section rate in obese as compared with non-bese patients.16 Obesity is currently a major public healthroblem worldwide, overwhelmingly affecting the obstet-ic population. Therefore, more research is warranted inhis field, providing strong scientific evidence and guide-ines to optimize multidisciplinary perinatal care in high-riskbstetric patients.18,19

Obstetric anesthesia is still a hot topic in the anesthesiaiterature. Despite many recent advances in the field, thessistance of obstetric patients is still frequently challengingo the anesthesiologists everywhere. The studies publishedn this issue of BJAN aimed to present new insights intohe obstetric anesthesia scenario. In summary, they havehown that advances in training techniques and understand-ng the potential benefits of anesthetic techniques and theirimitations is essential to improve clinical outcomes in thebstetric setting.

onflicts of interest

he authors declare no conflicts of interest.

eferences

1. Caton D. Obstetric anesthesia: the first ten years. Anesthesiol-ogy. 1971;33:102---9.

2. Edwards ML, Jackson AD. The historical development of obstet-ric anesthesia and its contributions to perinatology. Am JPerinatol. 2017;34:211---6.

3. Gibson ME. An Early History of Anesthesia in Labor. J ObstetGynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46:619---27.

4. Melzack R, Taenzer P, Feldman P, Kinch RA. Labour is stillpainful after prepared childbirth training. Can Med Assoc J.1981;125:357---63.

5. Whitfield A. A short history of obstetric anaesthesia. Res Medica.1992;III:28---30.

6. Carstoniu J, Levytam S, Norman P, Daley D, Katz J, SandlerAN. Nitrous oxide in early labor. Safety and analgesic efficacy

assessed by a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesthe-siology. 1994;80:30---5.7. McIntosh DG, Rayburn WF. Patient-controlled analgesia inobstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:1129---35.

20

AL

8. Akamatsu TJ, Bonica JJ. Ketamine for obstetric delivery. Anes-thesiology. 1977;46:78.

9. Akamatsu TJ, Bonica JJ, Rehmet R, Eng M, Ueland K. Expe-riences with the use of ketamine for parturition. I. Primaryanesthetic for vaginal delivery. Anesth Analg. 1974;53:284---7.

0. Ministério da Saúde. Diretrizes nacionais de assistência ao partonormal: relatório de recomendação; 2017.

1. Rosa T, Ribeiro I. History of the evolution of anesthesiafor obstetrics in a European Hospital. Eur J Anaesthesiol.2014;31:188.

2. Cambic CR, Wong CA. Labour analgesia and obstetric outcomes.Br J Anaesth. 2010;105 Suppl 1:i50---60.

3. Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, et al. Pain management forwomen in labour: an overview of systematic reviews. CochraneDatabase Syst Rev. 2012:CD009234.

4. Teixeira J, Carvalhas J, Pereira M, et al. General anesthesia foremergent cesarean delivery: simulation-based resident assess-ment. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021;71:254---8.

5. Edipoglu IS, Aslan DD. Association of postpartum depressionand epidural analgesia in women during labor: an observationalstudy. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021;71:208---13.

6. González-Tascón CC, Díaz EG, Losantos I. Epidural analgesia inthe obese obstetric patient: a retrospective and comparativestudy with non-obese patients at a tertiary hospital. Braz JAnesthesiol. 2021;71:214---20.

7. Devroe S, Van de Velde M, Rex S. General anesthesia for cae-sarean section. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:240---6.

8. Denison FC, Aedla NR, Keag O, et al. Care of women withobesity in pregnancy: green-top guideline No. 72. BJOG.2019;126:e62---106.

9. Mace HS, Paech MJ, McDonnell NJ. Obesity and obstetric anaes-thesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39:559---70.

Ana Maria M. Caetano a,∗, André P. Schmidtb

a Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE),Departamento de Cirurgia, Disciplina de Anestesiologia,

Recife, PE, Brazilb Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS),

Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Serviço deAnestesia e Medicina Perioperatória, Porto Alegre, RS,

Corresponding author.E-mail: [email protected] (A.M. Caetano).

6

I

E

A

a

b

M

A

h

c

h©B

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 2021;71(3):207

NFOGRAPHIC

pidural analgesia in the obese obstetric patient�

na Maria M. Caetano a,∗, André P. Schmidtb

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Departamento de Cirurgia, Disciplina de Anestesiologia, Recife, PE, BrazilUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Serviço de Anestesia eedicina Perioperatória, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

vailable online 27 April 2021

DOI of original article:ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.054� Article reference. González-Tascón CC, Díaz EG, Losantos I. Epiduromparative study with non-obese patients at a tertiary hospital. Braz J∗ Corresponding author.

E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] (A.M. Ca

ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.04.026 2021 Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. on behalf of Sociedade BrasilY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

al analgesia in the obese obstetric patient: a retrospective and Anesthesiol. 2021;71:214---20.

etano).

eira de Anestesiologia. This is an open access article under the CC.

C

Aas

I

a

Ib

RA

h©B

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 2021;71(3):208---213

LINICAL RESEARCH

ssociation of postpartum depression and epiduralnalgesia in women during labor: an observationaltudy

pek Saadet Edipoglu a,∗, Duygu Demiroz Aslanb

Marmara University, Faculty of Medicine, Division of Pain Medicine, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,stanbul, TurkeyIstanbul Training and Research Hospital, Department of Anesthesiology, Istanbul, Turkey

eceived 28 April 2019; accepted 9 December 2020vailable online 19 February 2021

KEYWORDSPostpartumdepression;Edinburgh postnataldepression scale;Epidural analgesia;Visual AnalogueScale;Vaginal birth

AbstractBackground and objectives: Postpartum depression affects women, manifesting with depressedmood, insomnia, psychomotor retardation, and suicidal thoughts. Our study examined if thereis an association between epidural analgesia use and postpartum depression.Methods: Patients were divided into two groups. One group received epidural analgesia duringlabor while the second group did not. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) wasadministered to patients prior to birth and 6 weeks postpartum. Pain severity was assessed bythe Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) during labor and at 24 hours postpartum.Results: Of the 92 patients analyzed, 47.8% (n = 44) received epidural analgesia. We detectedsignificantly higher VAS score during labor (p = 0.007) and 24 hours postpartum (p = 0.0001)in the group without epidural analgesia. At 6 weeks postpartum, a significant difference wasobserved between the EPDS scores of both groups (p = 0.0001). Regression analysis revealedhigher depression scores in patients experiencing higher levels of pain during labor (OR = 0.572,p = 0.039). Epidural analgesia strongly correlated with lower scores of depression (OR = 0.29,p = 0.0001).Conclusion: The group that received epidural analgesia had lower pain scores. A high correlationbetween epidural analgesia and lower depression levels was found. Pregnant women givingbirth via the vaginal route and having high pain scores could reduce postnatal depression scoresusing epidural labor analgesia. Pregnant women should opt for epidural analgesia during laborto lessen postpartum depression levels.

© 2021 Published by Elsevier EdThis is an open access article ulicenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).∗ Corresponding author.E-mail: [email protected] (I.S. Edipoglu).

ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.021 2021 Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. on behalf of Sociedade BrasilY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

itora Ltda. on behalf of Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia.nder the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/

eira de Anestesiologia. This is an open access article under the CC.

esio

I

CfrbnadsaiiiPotp

tndtsrHtdd

hssSt

M

OmIDIsOpwoswoiuiPss

cet

ewi(aegoapo3taeafdw(ipt(Eotettfdstwdtt(sts

S

SsmTpdldatti

Brazilian Journal of Anesth

ntroduction

urrently, increasing the rates of vaginal deliveries is theocus of attention because giving birth by the vaginaloute is one of the most important factors associated withoth maternal and infant health.1,2 Unfortunately, vagi-al delivery is not completely free of complications, suchs its association with postpartum depression.3 Postpartumepression, manifested as a depressed mood, insomnia oromnolence, marked weight loss, psychomotor retardation,

lowered self-esteem and self-worth, and suicidal thoughtss a disorder of pregnant women after giving birth.3,4 Thencidence of postpartum depression may be as high as 1n every 10 postpartum women in developed countries.5

ostpartum depression may lead to behavioral and devel-pmental problems both in the mother and the infant, andhose problems may extend into childhood and adolescenceeriods.6

Among women who deliver vaginally, a number prefero receive epidural analgesia for delivery while some doot. Epidural analgesia is commonly used to alleviate painuring labor and is well tolerated by both the mother andhe infant. Several studies and meta-analyses have demon-trated that epidural analgesia is an effective method toeduce the severity of pain during normal vaginal delivery.7

owever, there are only a few studies in the literature inves-igating the effect of epidural labor analgesia on postpartumepression which reported a decreased risk of postpartumepression with epidural labor analgesia.4

In this study, our primary hypothesis was that women whoad epidural labor analgesia would have lower depressioneverity scores 6 weeks postpartum. Our secondary hypothe-is was that those patients would have lower Visual Analoguecale (VAS) scores during labor and 24 hours postpartum ifhey received epidural analgesia.

ethods

ur study is a prospective observational study over a 6-onth period. The institutional ethics committee of the

stanbul Education and Research Hospital’s Anesthesiologyepartment approved this study. It is registered via the

SRCTN registry with study ID ISRCTN84174861 (recruitmenttart date of March 25, 2018 and recruitment end date ofctober 25, 2018). Women aged 18-45 years, who werelanning to give birth electively via a normal vaginal routeith or without epidural analgesia, with American Societyf Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-III, and who con-ented to participate were included in the study. Patientsere excluded if they had a history of schizophrenia, bipolarr obsessive-compulsive disorders in the prepartum period,f they had any hematological disorders that contraindicatedse of regional anesthesia, and if they had skin infectionsn the lumbar area or inadequate fetal vitality concepts.atients were also excluded if the route of delivery waswitched to a cesarean section or have prepartum depres-ion (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale ≥ 10).

Upon admission to our hospital, when patients met theriteria of inclusion, informed consent was obtained fromach patient in the waiting room and they were allocatedo one of the two groups. Initially we used ‘‘patient prefer-

Pfat

20

logy 2021;71(3):208---213

nce’’ for the decision of the technique. But for patientsho have contraindications for regional anesthesia, we

nformed and inclined the patient for the indicated approachinfection in the intervention site, bleeding, pathologies,nd intracranial disorders were our contraindications forpidural analgesia). One group consisted of women whoave birth without receiving epidural analgesia and the sec-nd group consisted of women who gave birth with epiduralnalgesia. The second group received an epidural catheter,laced in the intervertebral space between either L3---L4r L4---L5, when cervical dilatation of the patient reached---5 cm, while the other group received no intervention forheir labor. Patients in the epidural analgesia group received

bolus dose of bupivacaine 0.125% + 100 �g fentanyl via thepidural catheter. This was followed by patient-controllednalgesia (PCA) containing 0.125% bupivacaine + 2 �g.mL-1

entanyl with 6 ml.h-1 continuous infusion and 6 ml PCAemand dose with 10-minute lockouts. Prior to birth and 6eeks postpartum, an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

EPDS) was administered to both patient groups. The EPDSs a commonly used 10-item scale validated for our studyopulation. A score ≥ 10 was the cut-off score for postpar-um depression. If a patient responded positively to item 10the thought of harming myself has occurred to me) of thePDS, they were evaluated for overt depression regardlessf the patient’s total score and were reported to our hospi-al’s psychiatric department. EPDS were applied by the samexperienced anesthesiologist. Both groups received postpar-um analgesia. One group received epidural PCA containinghe previously started dose (0.125% bupivacaine + 2 �g.mL-1

entanyl with 6 ml.h-1 continuous infusion and 6 ml PCAemand dose with 10-minute lockouts) until discharge. Theecond group received intravenous (IV) tramadol 1 mg.kg-1

wice a day and 15 mg.kg-1 paracetamol three times a day asell as rescue tramadol doses of 1 mg.kg-1 if necessary, untilischarge. The patient’s severity of the pain was assessed byhe VAS during the birth and 24 hours postpartum. In the VAS,he lowest score is 0 (no pain at all) and the highest is 10worst pain imaginable). The aim was to keep patient VAScores below 4. We recorded demographic parameters, ges-ational age, number of pregnancies, VAS scores, and EPDScores.

tatistical analysis

PSS 21.0 software was used for the statistical analysis. Thetudy data were summarized with the descriptive statisticalethods (mean, standard deviation, frequency, and ratio).he Mann---Whitney U test was used for inter-group com-arisons of quantitative data not conforming to a normalistribution. The correlation between the use of epiduralabor analgesia, VAS score, and occurrence of postpartumepression was assessed with multivariate logistic regressionnalysis. The Hosmer---Lemeshow test was used for the logis-ic regression model. Qualitative data was compared withhe Student’s t test. Results were evaluated in a confidencenterval of 95% and at a significance level of p < 0.05. The

ower and Sample Size program (PS version 3.1.2) was usedor patient number analysis. If the change in the EPDS wasssumed to be at least 20%,4 the lowest number of patientso be included in the study should be 88 to meet an � = 0.059

I.S. Edipoglu and D.D. Aslan

F artuw

aht

R

OfAatl

4TTdT

ga

igure 1 Flow Diagram. A comparison of the severity of postpithout epidural analgesia.

nd a power = 0.80. It was assumed that there would be aigh number of drop-outs in the study, therefore we plannedo include 127 patients at baseline.

esults

f the 198 patients analyzed for eligibility, 166 wereound eligible according to the exclusion/ inclusion criteria.

mong these 166 eligible patients, 129 patients gave consentnd participated in the study. After excluding patients losto follow-up and change of delivery, 92 patients were ana-yzed in the final evaluation (Fig. 1). Of these 92 patients,a

rs

21

m depression in women who gave normal vaginal birth with or

7.8% (n = 44) preferred delivery with epidural analgesia.he remaining patients did not receive epidural analgesia.he mean age of the patients was 29.81 ± 7.19 years. Theemographic data of the study patients are presented inable 1.

No statistically significant differences in patient demo-raphics were detected between the epidural labornalgesia group and the group who did not receive epidural

nalgesia (p > 0.05). These data are presented in Table 2.In the group of women who gave birth without epidu-al analgesia, we detected significant differences in the VAScores both during labor (p = 0.0001) and 24 hours after deliv-

0

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 2021;71(3):208---213

Table 1 Patient Demographic Data.

Epidural analgesia group 47.8% (n = 44)Age (years) 29.81 ± 7.19Body Mass Index (BMI) 28.24 ± 4.39Gestation (weeks) 38.47 ± 0.79Number of pregnancies 1.88 ± 1.16VAS score during labor 5.58 ± 2.52VAS 24 hours postpartum 4.17 ± 2.18Prepartum EPDS scores 8.32 ± 4.66EPDS score 6 weeks postpartum 6.08 ± 4.58ASA score

II 60 (64.5%)III 32 (34.4%)

VAS, Visual analogue scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depres-sion Scale; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physicalstatus.

Table 2 Comparison of the demographic data between thetwo groups.

Epiduralanalgesia(n = 44)

No epiduralanalgesia(n = 48)

p-value

Age (years) 28.88 ± 6.81 30.64 ± 7.49 0.243Body Mass Index (BMI) 28.07 ± 4.12 28.4 ±4.65 0.723Gestational age (weeks)38.43 ± 0.72 38.52 ± 0.85 0.593Number of pregnancies 1.28 ± 0.48 2.31 ± 1.33 0.076ASA score

II 29 (65.9%) 31 (64.5%) 0.894III 15 (34.1%) 17 (35.5%)

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

ebpipsbde

s

Table 4 Multiple regression analysis of EPDS scores.

Odds Ratio (OR) p-value

VAS score 24 hours postpartum 0.288 0.117VAS score at labor 0.572 0.039*Epidural analgesia 0.290 0.0001*

VAS, Visual analogue scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depres-sion Scale.An EPDS score ≥ 10 equals depression.

ldonwd

D

Iebdibchairwsbd

pltr

ciation between epidural analgesia and decreased severity

Mann---Whitney U test and Student’s t test were used.p < 0.05 was determined statistically significant.

ry (p = 0.007). Overall, we report that the women givingirth with epidural analgesia experienced significantly lowerain levels (Table 3). There was not a significant differencen the EPDS scores between the groups in the prepartumeriod (p = 0.191); however, we detected a high degree ofignificant difference in the EPDS scores 6 weeks postpartumetween the two groups (p = 0.0001). Therefore, postnatalepression score was lower among women who received

pidural analgesia (Table 3).Multiple regression analysis (Table 4) revealed that EPDScores correlated with receiving epidural analgesia during

otl

Table 3 Comparison of VAS and EPDS scores between groups.

Epiduralanalgesia(n = 44)

VAS score during labor 3.28 ± 0.95

VAS score 24 hours postpartum 2.71 ± 0.82

Prepartum EPDS score 7.63 ± 4.72

EPDS score 6 weeks postpartum 3.89 ± 3.43

VAS, Visual analogue scale; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression ScaMann---Whitney U test and Student’s t test were used.

a p < 0.05 was determined statistically significant.

21

The Hosmer---Lemeshow test was used for the logistic regressionmodel.

abor and with VAS scores during delivery. Higher scores ofepression were found in patients experiencing higher levelsf pain during labor (OR = 0.572, p = 0.039). This finding wasot detected 24 hours postpartum in VAS scores. In addition,omen who received epidural analgesia had lower scores ofepressions (OR = 0.29, p = 0.0001) (Table 4).

iscussion

n this study, we investigated the relationship betweenpidural analgesia and depression score in women who gaveirth vaginally. The EPDS, which is widely used and vali-ated, was selected to assess the probability of depressionn the women included in the study.8,9 This scale has alsoeen validated for the pregnant patient population in ourountry.10 We observed that pain severity was significantlyigher in the women who did not prefer to receive epiduralnalgesia during labor, with significantly higher VAS scoresn both the prepartum and postpartum periods. Logisticegression analysis identified that the VAS score at laboras correlated with the development of postnatal depres-

ion (OR = 0.572, p = 0.039). We report a very high correlationetween the use of epidural analgesia and lower postpartumepression levels (OR = 0.29, p = 0.0001).

In a recent study, Lim et al. reviewed a total of 201atients retrospectively and reported that alleviation ofabor pain with epidural analgesia resulted in a reduction inhe severity of depression symptoms.6 We reported similaresults in this observational and prospective study.

Again, similar to our results, Ding et al. reported an asso-

f depression in a study including 200 individuals.4 We addi-ionally evaluated patient depression levels both beforeabor and in the postpartum period. In our study, there was

No epiduralanalgesia(n = 48)

p-value

7.21 ± 1.93 0.0001a

5.30 ± 2.26 0.007a

8.91 ± 4.58 0.1918.08 ± 4.61 0.0001a

le; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

1

and

nptarbsdaObd

ibwebasttiectecma

wpeargVobs

adAresaarcoc

nwlmfce

ttAtcet

C

IapgsdtIg

T

Or

C

T

R

I.S. Edipoglu

o difference in depression levels between the two groupsrior to labor, however, there was a significant difference inhe EPDS scores 6 weeks postpartum (p = 0.0001). Regressionnalysis demonstrated the correlation between the epidu-al analgesia and depression effectively. A study performedy Badou et al. with 43 patients was the first to demon-trate an association between the severity of labor pain andepression.11 Contrary, some studies were unable to detect

relationship between depression and labor pain severity.ur study is in line with that published by Badou et al. Weelieve the discrepancy in outcomes are due to insufficientata regarding pain scores.4

There are a wide range of studies in the literaturenvestigating the outcomes of postpartum depression onoth mother and infant. One study investigated patientsho underwent a cesarean section and those who deliv-red vaginally, and they suggested a significant relationshipetween severe pain and postpartum depression.12 Theylso reported that postpartum depression may be respon-ible for 17% of late-phase maternal deaths.12 In addition tohose studies, a number of studies in the literature reporthat postpartum depression adversely affected nursing thenfant.13,14 In their study including 2,729 patients, Verbeekt al. reported that postpartum depression affected thehildhood period unfavorably. Furthermore, they added thathose effects may be so extensive that they negatively influ-nce the adolescent period.15 These findings lead to theonclusion that postpartum depression is a major cause oforbidity in women and attempts to lower its incidence rate

re needed.In our current study, we report that the VAS score 6

eeks postpartum was correlated with development ofostnatal depression. Several studies, available in the lit-rature, report similar results to those of our study in whichdministration of epidural analgesia resulted in a significanteduction in VAS scores.16---18 We believe that epidural anal-esia is the main determinant for pain reduction and lowerAS scores. We also assume that this reduction in pain wasne of the most important factors creating the correlationetween epidural analgesia and lower postpartum depres-ion rates.

On the other hand, other studies report that epiduralnalgesia in pregnant women cause unfavorable or contra-icting results. In a meta-analysis including 9,658 patients,nim et al. reported results different from those summa-ized above.7 They found that women who received anpidural mode of administration experienced more hypoten-ion compared to women that did not.7,19---21 Other studieslso reported that epidural modes of administration caused

delay in the second phase of labor.7,22,23 Although epidu-al analgesia allows for better pain control, the authorsould not demonstrate significant differences in the levelsf maternal satisfaction, reporting that there were someontradicting findings.7

The limitations of our study are the low number of preg-ant women included. Increasing the number of patientsould maybe enhance the value of our findings. Another

imitation is that VAS scores are a subjective means of assess-

ent for pain. However, a more effective scoring systemor pain assessment is not available. Therefore, the VAS isommonly used in the literature. One of the best ways ofvaluating postoperative pain is the opioid consumption of

21

D.D. Aslan

he patient but we could not use this approach because ofhe different methods of analgesia for postpartum period.lso, there are other confounding factors that may influencehe chance of postpartum depression like patients’ socioe-onomic class and postpartum BMI at the time of the secondvaluation but we did not investigate these variables andhis is another limitation for our study.

onclusion

n conclusion, our study found an association between favor-ble VAS scores and lower depression severity 6 weeksostpartum in women who received epidural analgesia andave birth vaginally. In addition, we report that increasedcores of pain at labor were correlated with postpartumepression score and there was a very high correlation withhe use of epidural analgesia and lower depression levels.n light of these results, we suggest that pregnant womeniving birth via the vaginal route should use analgesia.

rial registry

ur study was registered February 15, 2016 via the ISRCTNegistry with study ID ISRCTN84174861.

onflict of interest

he authors declare no conflicts of interest.

eferences

1. World Health Organization. Monitoring Emergency ObstetricCare: A Handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2009.WHO.

2. Bayrampour H, Salmon C, Vinturache A, et al. Effect of depres-sive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy on risk of obstetricinterventions. J. Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:1040---8.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and StatisticalManual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition; text revision Washing-ton, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

4. Ding T, Wang DX, Qu Y, et al. Epidural Labor Analgesia IsAssociated with a Decreased Risk of Postpartum Depression: AProspective Cohort Study. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:383---92.

5. Orbach-Zinger S, Landau R, Harousch AB, et al. The RelationshipBetween Women’s Intention to Request a Labor Epidural Anal-gesia, Actually Delivering With Labor Epidural Analgesia, andPostpartum Depression at 6 Weeks: A Prospective ObservationalStudy. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1590---7.

6. Lim G, Farrell LM, Facco FL, et al. Labor Analgesia as a Predic-tor for Reduced Postpartum Depression Scores: A RetrospectiveObservational Study. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:1598---605.

7. Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2011;7:CD000331.

8. Zanardo V, Giliberti L, Volpe F, et al. Cohort study of thedepression, anxiety, and anhedonia components of the Edin-burgh Postnatal Depression Scale after delivery. Int J GynaecolObstet. 2017;137:277---81.

9. Matthey S, Souter K, Mortimer K, et al. Routine antenatal mater-nal screening for current mental health: evaluation of a changein the use of the Edinburgh Depression Scale in clinical practice.Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19:367---72.

2

esio

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

Brazilian Journal of Anesth

0. Aksu S, Varol FG, Hotun Sahin N. Long-term postpartum healthproblems in Turkish women: prevalence and associations withself-rated health. Contemporary Nurse. 2017;53:167---81.

1. Boudou M, Teissèdre F, Walburg V, et al. Association betweenthe intensity of childbirth pain and the intensity of postpartumblues. Encephale. 2007;33:805---10.

2. Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain afterchildbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain andpostpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87---9.

3. Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: a system-atic review of the literature. Affect Disord. 2015;171:142---54.

4. Figueiredo B, Canário C, Field T. Breast feeding is nega-tively affected by prenatal depression and reduces postpartumdepression. Psychol.Med. 2014;43:1---10.

5. Verbeek T, Bockting CL, van Pampus MG, et al. Postpartumdepression predicts offspring mental health problems in ado-lescence independently of parental lifetime psychopathology. JAffect Disord. 2012;136:948---54.

6. Pugliese PL, Cinnella G, Raimondo P, et al. Implementation ofepidural analgesia for labor: is the standard of effective anal-gesia reachable in all women? An audit of two years. Eur RevMed Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:1262---8.

2

21

logy 2021;71(3):208---213

7. Sikdar I, Singh S, Setlur R, et al. A prospective review of thelabor analgesia programme in a teaching hospital. Med J ArmedForces India. 2013;69:361---5.

8. Sweed N, Sabry N, Azab T, et al. Regional versus IV analgesicsin labor. Minerva Med. 2011;102:353---61.

9. El-Kerdawy H, Farouk A. Labor analgesia in preeclampsia:remifentanil patient controlled intravenous analgesia versusepidural analgesia. Middle East Journal of Anesthesiology.2010;20:539---45.

0. Head B, Owen J, Vincent R, et al. A randomized trial ofintrapartum analgesia in women with severe preeclampsia.Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2002;99:452---7.

1. Gambling DR, Sharma SK, Ramin SM, et al. A randomizedstudy of combined spinal epidural analgesia versus intravenousmeperidine during labor: impact on cesarean delivery rate.Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1336---44.

2. Lian Q, Ye X. The effects of neuraxial analgesia of combinationof ropivacaine and fentanyl on uterine contraction. Anesthesi-

ology. 2008;109:A1332.3. Long J, Yue Y. Patient controlled intravenous analgesiawith tramadol for pain relief. Chinese Medical Journal.2003;116:1752---5.

3

C

Erp

C

a

b

RA

h©l

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology 2021;71(3):214---220

LINICAL RESEARCH

pidural analgesia in the obese obstetric patient: aetrospective and comparative study with non-obeseatients at a tertiary hospital

laudia Cuesta González-Tascón a,∗, Elena Gredilla Díaz a, Itsaso Losantos Garcíab

Servicio de Anestesiología y Reanimación, Hospital universitario La Paz, Madrid, SpainDepartamento de Bioestadística, Hospital universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain

eceived 18 February 2020; accepted 27 February 2021vailable online 9 April 2021

KEYWORDSObesity;Neuraxial anesthesia;Labor analgesia;Cesarean section

AbstractBackground and objectives: Obesity is becoming a frequent condition among obstetric patients.A high body mass index (BMI) has been closely related to a higher difficulty to perform theneuraxial technique and to the failure of epidural analgesia. Our study is aimed at analyzingobese obstetric patients who received neuraxial analgesia for labor at a tertiary hospital andassessing aspects related to the technique and its success.Methods: Retrospective observational descriptive study during one year. Women with a BMIhigher than 30 were identified, and variables related to the difficulty and complications ofperforming the technique, and to analgesia failure rate were assessed.Results and conclusions: Out of 3653 patients, 27.4% had their BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-2. Neuraxialtechniques are difficult to be performed in obese obstetric patients, as showed by the numberof puncture attempts (≥ 3 in 9.1% obese versus 5.3% in non-obese being p < 0.001), but theincidence of complications, as hematic puncture (6.6%) and accidental dural puncture (0.7%)seems to be similar in both obese and non-obese patients. The incidence of cesarean section inobese patients was 23.4% (p < 0.001). Thus, an early performance of epidural analgesia turnsout to be essential to control labor pain and to avoid a general anesthesia in such high-riskpatients.

© 2021 Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia. Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. This is anopen access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).∗ Corresponding author.E-mail: [email protected] (C.C. González-Tascón).

ttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.054 2021 Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia. Published by Elsevier Ed

icense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

itora Ltda. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-NDesio

B

OcentO3no3tIowladt

nittprb3fpmtptrttwa

otsadc

ota

M

Bnmrhwb

ninappgca

wocwdow

mdtctwottp

a

awmtdctinftllN

R

D

Ta7g

Brazilian Journal of Anesth

ackground

besity has become an increasi ng concern worldwide andontinues to rise in developed countries, both among gen-ral and obstetric population. Body mass index (BMI) isowadays considered a reliable and well-known indica-or used worldwide in overweight and obesity diagnosis.verweight and obesity are defined as a BMI ≥ 25 and ≥0 kg.m-2, respectively. According to the World Health Orga-ization (WHO), obesity is classified in three categories:besity grade I (BMI range, 30---34.9 kg.m-2), grade II (range,5---39.9 kg.m-2), and grade III (> 40 kg.m-2). According tohe last data published by the Spanish National Statisticsnstitute in 2017, 44.3% of men and 30% of women wereverweight, and obesity rate was 18.2% in men and 16.7% inomen.1 BMI has in fact increased up to 0.4% during the

ast 30 years worldwide.2 Overweight and obese patientsre associated with greater comorbidity, such as coronaryiseases, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, or gas-rointestinal reflux.2

Obesity during pregnancy is also implicated in the mater-al and perinatal outcome. On one hand, obesity is anmportant risk factor of hypertensive disorders and gesta-ional diabetes during pregnancy.3,4 Hypertension can evolveo preeclampsia, which considerably increases maternal anderinatal morbimortality, and causes intrauterine growthetardation of the fetus. Moreover, a BMI ≥ 25 kg.m-2 haseen associated to a greater risk of miscarriage (58% versus7% in non-obese pregnant women) and congenital mal-ormations, mainly spina bifida, neural tube defects, cleftalate and congenital heart diseases.5 A delayed diagnoseay be due to the greater difficulty of using ultrasound in

hese patients. On the other hand, the placenta of obeseregnant women weighs around 60---80 grams more at theime of birth, and it is just placenta weight that has a greaterelation to the weight of the newborn.5 Therefore, it seemshat fetal macrosomia index, defined as a weight at theime of birth over 4000---4500 grams, is greater among obeseomen, which justifies a higher odd of cesarean sectionmong these patients.5---7

The greater rates of instrumental or cesarean delivery inbese pregnant women turns neuraxial anesthesia into theechnique of choice. The key is to avoid general anesthe-ia in patients, whose pregnant condition plus their obesityltogether, increase complications dramatically, such as aifficult airway or failed resuscitation after hemodynamicollapse.4

Therefore, we will discuss the impact of obesity in thebstetric and anesthetic management, as well as focus onhe importance of a suitable neuraxial technique on time sos so guarantee the safety of this kind of patient.

aterial and methods

ased on the increasing prevalence of obesity among preg-ant women and the close relationship between obesity andaternal and perinatal outcomes, we have carried out a

etrospective observational descriptive study at a tertiaryospital among pregnant women (obese and non-obese),ho received neuraxial analgesia for labor at our centeretween January and December 2017.

1ir(

21

logy 2021;71(3):214---220

The main purpose was to analyze the features of all preg-ant women over 18 years old, as well as different variablesn relation to the difficulty of performing the neuraxial tech-ique, and the maternal and neonatal outcomes, so as to beble to establish a comparison with the non-obese obstetricopulation for the same period. For such reason, we pro-osed the hypotheses that a high BMI was associated withreater maternal and neonatal comorbidity, a higher diffi-ulty to perform the neuraxial technique and failure rate,s well as a higher cesarean section rate.

Out of the whole sample, women with a BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-2

ere identified, while variables related to the difficultyf performing the technique, to analgesia failure rate andomplications were evaluated. Maternal body mass indexas calculated based on the recorded height and weight atelivery. Thus, patients were classified into two groups: non-bese pregnant women (BMI < 30 kg.m-2) and obese pregnantomen (BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-2).

Demographic data related to maternal age, to BMI andaternal pathologies, were collected as well as obstetricata (i.e. gestational age, parity, single or twin pregnancy,ype of labor (spontaneous or instrumental delivery, andesarean section), and neonatal data. Information on theechnique performed (epidural or combined spinal-epidural)as collected as well. On the bases of the complicationsf the technique, we defined the success or failure of ourechnique as the number of puncture attempts, as well ashe incidence of hematic puncture (HP) and accidental duraluncture (ADP).

Finally, we identified those cases that required generalnesthesia due to a failed neuraxial technique.

Qualitative data description was made in the form ofbsolute frequencies and percentages. Quantitative dataere presented through an average ± typical deviation,inimum and maximum when they were continuous and

hrough the percentile and the interquartile range whenealing with ordinary variables. Qualitative variable asso-iation was analyzed by the chi-square test or Fisher’s exactest. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing qual-tative and quantitative data, for independent data, ason-parametric evidence, and the Student’s t-student testor independent data as parametric evidence. All statisticests were considered bilateral and those including p-valuesower than 0.05 were considered significant. Data were ana-yzed by the statistics software SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary,C, USA).

esults

emographic data

he study covered a total number of 3653 patients with anverage age of 32.82 ± 5.8 years and an average weight of4.51 ± 12.16 kg (average BMI 27.51 ± 5.75 kg.m-2). Averageestational age was 38.83 ± 2.49 weeks.

Out of the total number of patients observed (n = 3653),

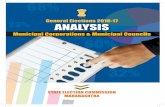

001 patients (27,4%) had a BMI ≥ 30 kg.m-2 (Fig. 1). Accord-ng to the BMI, 747 patients (74.62%) had obesity grade I (BMIange, 30---34.99), 189 patients (18.88%) had obesity grade IIBMI range, 35---39.99), 63 patients (6.3%) had obesity grade5

C.C. González-Tascón, E.G. Díaz and I.L. García

74.62%

18.88%

6.30%0.20%

G R A D E 1 G R A D E 2 G R A D E 3 G R A D E 4

DISTRIBUT ION OF OBESI TY GRADE INPREGNANT PATIENTS

Figure 1 Distribution of obesity grade among obese pregnant women.

Table 1 Hypertensive disorders in obese and non-obesepregnant women (p = 0,799).

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy PATIENT COLLECTION

NON-OBESES 2,3% (n = 60)OBESES 2,1% (n = 20)

Obesity grade I 2,1% (n = 15)Obesity grade II 1,6% (n = 3)Obesity grade III 3,3% (n = 2)

Ih

O

GIipw(ot

HItnhsI(

N

IbbpucOot

Table 2 Difficulty of neuraxial technique regarding punc-ture attempts (p < 0,001).*

PUNCTURE ATTEMPTS % OBESE % NON-OBESES

1---2 90,8% (n = 883) 94,8% (n = 2373)3---4 8,3% (n = 81) * 5,2% (n = 129) *> 4 0,8% (n = 8) * 0,1% (n = 2) *

qp

icoawua(oortonosip(pptl

gaasg

Obesity grade IV 0%

II or extreme (BMI range, 40---49.99), and 2 patients (0.2%)ad obesity grade IV or morbid (BMI 50 or greater).

bstetric pathology

estational Diabetes (GD)n our study, gestational diabetes rate was slightly highern obese women (5.2% versus 5% in non-obese), being

= 0.757. Out of the total number of obese pregnant womenith GD (n = 51), 39 patients presented obesity grade I

76.5%), 9 patients obesity grade II (17.6%) and 3 patientsbesity grade III (5.9%). We did not find any patient amonghe population studied with obesity grade IV who had GD.

ypertensive disorders in pregnancyn spite of the fact that the incidence of gestational hyper-ension has turned out to be greater in non-obese (2.3%,

= 60) versus obese (2.1%; n = 20), being p = 0.799, it must beighlighted that there was a greater presence of hyperten-ive disorders in those pregnant women with obesity gradeII (3.3%) versus the other obese patients, with p = 0.882Table 1).

euroaxial technique and complications

t was performed 3237 epidural techniques and 416 com-ined spinal-epidural (CSE). The technique was required toe repeated in 52 patients out of the total number of obeseregnant women (5.19%) due to the lack of analgesia 45 min-tes after the placement of the catheter, and this time, a

ombined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique was performed.ne or two puncture attempts were needed in 94.8% of non-bese compared to 90.7% of obese. According to our data,he need of three or more attempts was clearly more fre-E

A(

21

* These results are statistically significant (p < 0,001).

uent among obese, 9.1% against 5.3% of non-obese, being < 0.001 (Table 2).

If all possible complications related to the neurax-al technique are taken into account, the odds of theseomplications altogether were 72.7% (n = 2021) in the groupf non-obese and 27.3% (n = 758) in the obese one. Whennalyzing each of the complications separately, HP incidenceas 6,6% in both groups, being n = 50 among the obese pop-lation against n = 133 in non-obese, with p = 0,659, as wells the odds of ADP, which was 0,7% (n = 5) in obese and 0,7%n = 15) in non-obese with p = 0.659. However, the numberf patients who had headache after delivery was higher (8bese and 37 non-obese women) than the number of ADPecorded in both groups. This can be explained because ofhe fact that post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is onef the most common postpartum complications followingeuraxial block, but dural puncture is not the only causef postpartum headache. Other possible causes can be ten-ion headache, migraine or cortical vein thrombosis, whosencidence is increased during pregnancy and in the puer-erium. A blood patch was performed in only two patients25%) out of the total obese pregnant women with post-artum headache (n = 8), against 22 out of 37 non-obeseregnant women with postpartum headache (Table 3). Inhis case, p-value could not be calculated because of theack of data.

Despite the fact that the number of HP and ADP alto-ether was greater among non-obese population, whennalyzing these complications among the obese population,nd depending on the BMI of the patient, we faced in ourtudy a greater incidence in those patients with obesityrade III (16.36%, n = 9), being p = 0.022.

xpulsive phase of labor

mong our studied population, labor was induced in 63.1%n = 632) of obese versus 26.2% (n = 694) of non-obese. On

6

Brazilian Journal of Anesthesio

Table 3 Incidence of postpartum headache and accidentaldural puncture (ADP) and the need of blood patch in obeseand non-obese parturients.

OBESE(IMC > 30)

NON-OBESE(IMC < 30)

Accidental duralpuncture (ADP)

5/1001 15/2652

Postpartum headache 8/1001 37/2652

OBESE(IMC > 30)

NON-OBESE(IMC < 30)

ooO(F2=cb

aawe

naoap

D

Boat

imioocsittotaah

apvp

ganat

totstcua

padh

BLOOD PATCH 2 (25%) 22 (59,45%)NO BLOOD PATCH 6 (75%) 15 (40,54%)

ne hand, delivery was spontaneous in 79% (n = 2096) of non-bese, against 67,6% (n = 677) of obese, where p < 0,001.n the other hand, instrumental delivery was recorded in 9%

n = 90) of obese, contrary to 9.2% (n = 246) of non-obese.inally, cesarean section rate in obese pregnant women was3,4% (n = 234), whereas among non-obese was 11.7% (n

310), being p < 0,001. In our study, the main reason foresarean section was failure of induction or disproportionetween the fetus and the uterus (Table 4).

In our population, seven of the patients who underwent cesarean section required sedation besides the epiduralnesthesia due to the lack of pain control. In addition, fiveomen needed general anesthesia because of an incompletepidural block.

On the bases of our database, the average weight of aewborn child was 3187.26 ± 455.53 grams in non-obesend 3326.67 ± 485.12 grams in obese, being the incidencef fetal macrosomia higher in this latter group (5.6%, n = 51)gainst 2.6% (n = 64) in non-obese pregnant women, where

< 0.001.

iscussion

ased on our study results, the prevalence of overweight andbesity in obstetric patients is markedly high in our centre,s it has recently become a reference center nationwide forhe obstetric follow-up of obese pregnant women. Accord-

bls

Table 4 Delivery in obese and non-obese parturients (p < 0,001).

OBESE (IM

SPONTANEOUS DELIVERY 677 (67INSTRUMENTAL DELIVERY 90 (9

Spatula 29 (2Forceps 47 (4

Ventouse 14 (1

OBESE

CESAREAN SECTION 234

- FI or disproportion (NICE III) 19- NRFS (NICE I) 44

NON CESAREAN SECTION 767

* FI (Failed Induction); NRFS (Non-reassuring Fetal Status).

21

logy 2021;71(3):214---220

ng to test results, obese pregnant women show greateredical comorbidity, which had been widely studied and

dentified in previous studies. Our findings suggest that thedds of gestational diabetes are slightly higher in the groupf obese pregnant women, although statistical significanceould not be reached. However, the incidence of hyperten-ive disorders was 25% (n = 20) in obese against 75% (n = 60)n non-obese. Therefore, although it has not been possibleo find a close relation between obese women and hyper-ensive conditions, it is quite interesting the higher ratef hypertension in obesity grade III. We should be awarehat obesity is only one of the multiple risk factors associ-ted with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, such asdvanced gestational age or medical conditions (e.g. chronicypertension, diabetes mellitus or chronic renal disease).

In our center, the epidural technique is the first option inny case, but when pregnant women show a breakthroughain related to strong uterine dynamics or advanced cer-ical dilatation, then the CSE technique will be preferablyerformed.

Recent studies show that a high BMI is correlated to4,5,7,8:reater complication to perform the technique, determineds a higher number of puncture attempts and more timeeeded to find the epidural space; greater failure of epiduralnalgesia; and greater delay in detecting the failure of theechnique.

Despite the fact that a high BMI means a risk factor forhe failure of the technique, in our daily practice, we do notbserve such a high failure rate in obese pregnant women ashe one described in the literature. In our hospital, analge-ia for delivery is performed by residents from second up toheir last year of training. However, neuraxial techniques inomplicated patients (e.g. obese patients or scoliosis) aresually carried out by residents in their last year or thettending anesthesiologist.

In most cases, locating the epidural space in obeseregnant women becomes complicated due to the loss ofnatomical references and because the epidural skin-spaceistance (ESD) may be bigger than usual.4,8 Previous studiesave already recorded the directly proportional association

etween BMI and ESD, although this distance is not normallyonger than 8 cm in most patients.9,10 Our study did not mea-ure ESD, but has collected a greater number of puncture*.

C >30) NON-OBESE (IMC < 30)

,6%) * 2096 (79%) *%) * 246 (9,2%) *,9%) 91 (3,4%),7%) 101 (3,8%),4%) 54 (2%)

(IMC >30) NON-OBESE (IMC < 30)

(23,4%) * 310 (11,7%) *0 (19%) 234 (8,8%)

(4,4%) 76 (2,9%)(76,6%) * 2342 (88,2%) *

7

E.G

ad

rtpicTplmtn(trturTnasrtUotntioiotenftldnttnttgsrypitp

r1aha

tcitewAPtetiltsn

tiltsehSnrfwai

iastIess

smwcibraS

peienoc

C.C. González-Tascón,

ttempts in obese pregnant women, which confirms a higherifficulty in locating epidural spaces in this type of patient.

Air or saline solution can be used to identify the loss ofesistance when finding the epidural space. It is importanto highlight that ligaments are softer in obese and pregnantatients due to the influence of progesterone. Based on this,t seems that the feeling of losing resistance using air is moreonfusing and so the likelihood of false positives increases.herefore, we can state that the greater the BMI of theatient, the more difficult the puncture becomes, and so theoss of resistance technique with saline solution is recom-ended for these patients.11 However, we should be aware

hat epidural space localization using loss of resistance tech-ique with saline can hinder the identification of an ADPinadvertent dural puncture). When air is used to identifyhe epidural space, any cerebrospinal leak can be easilyecognized, unlike when saline is used. Hence, the idealechnique for identification of the epidural space remainsnclear. Moreover, accurate identification of the anatomicaleferences in the obese patient can be widely complicated.he risk of a general anesthesia in such patients is so high,ot only because of the pregnancy but also the obesity, thatn adequate epidural analgesia must be achieved. Ultra-ound (US) techniques are proposed to improve the successate during epidural catheter insertion, as well as to reducehe complications related to the accidental dural puncture.S imaging of the spine is thought to reduce the likelihoodf a failed and traumatic catheterization. Several studiesried to investigate the ease of catheter insertion, the timeeeded for the procedure and the rate of success, comparedo the traditional palpation technique. Some of these stud-es compared the US examination of the spine in lean andbese patients12 and others analyzed the US guidance onlyn obese patients scheduled for elective cesarean section13

r otherwise only in patients with BMI < 35 kg.m-2.14 Givenhe results of these studies, US imaging helps locate thepidural space in the obese parturient, and so reduces theumber of puncture attempts and the time needed to per-orm the technique. Nonetheless, the use of US appears noto be that helpful in lean parturients, in which anatomicalandmarks are clearly palpable. Thus, there is some evi-ence that US guidance may improve the success of theeuraxial block in the obese parturient, as well as reducehe rate of procedure-related adverse events. Furthermore,he impact of US on patient satisfaction regarding the tech-ique and analgesia has been highly positive.15 However,he learning curve can be complicated and so US-guidedechniques are recommended only when the anesthesiolo-ist is used to perform and interpret US images. In fact, thetudies mentioned above have been carried out by expe-ienced anesthesiologists trained in US scanning. In recentears, the use of ultrasonography has become increasinglyopular in anesthesiology. Hence, it should be consideredn obstetric anesthesia because of its potential benefits inhe obese parturient, avoiding a general anesthesia in theseatients.

According to the literature, ADP incidence in the obstet-ic population is up to 4% in obese pregnant women versus

% in non-obese ones.16---18 In our study, complications suchs ADP or HP seem to be similar in both groups, although weave not been able to demonstrate that such associationsre statistically significant. When all complications relatedccan

21

. Díaz and I.L. García

o the neuraxial technique are considered, the rate of theseomplications in the obese patient is not higher compar-ng to non-obese in our study. As previously mentioned, theechnique in the obese parturient has been performed byxperienced anesthesiologists, so the probability of successas higher in such patients. Around 50-80% of patients withDP develop PDPH.19---22 Our study has not found a higherDPH incidence among obese population, which matcheshe results obtained in previous studies. In fact, the Peraltat al. study16 demonstrated that a BMI ≥ 35 kg.m-2 was a pro-ective factor against the development of PDPH. The reasons related to a higher pressure in the epidural space, whichimits the leak of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) just throughhe dural rent. Nonetheless, once PDPH has developed, itseverity and treatment (analgesia and/or blood patch) doot seem to be related to the BMI of the patient.

As there is not still a standard definition of failure ofhe epidural technique, it appears to be difficult to reportts real incidence. A widely acceptable definition is theack of analgesia during the first 45 minutes after placinghe catheter in the epidural space.8 Kula et al., in theirtudy,4 mentioned the assessment of the number of nec-ssary attempts to place a catheter as the way to estimateow difficult the technique was and the likelihood of failure.aravanakumar et al. found in their study that 74% of preg-ant women needed more than one attempt, and up to 14%equired three or more attempts, being the total failure rateor this technique 42% in this kind of patient.23 In our study,e have been able to assess the success of the techniqueccording to the number of puncture attempts and we diddentify a correlation with data obtained in the literature.

Finally, we noted a higher rate of cesarean deliveryn obese pregnant women. The literature states a greaternesthetic risk among obese women who undergo cesareanection under general anesthesia, as it is expected due tohe physiological and anatomical changes during pregnancy.n this sense, Brick et al. do mention a higher cesarean deliv-ry rate among obese multiparous pregnant women, whileuch relation between BMI and the likelihood of cesareanection is not found in obese nulliparous pregnant women.24

Eventually, we observed in our population significanttatistics when referring to a greater incidence of fetalacrosomia in obese pregnant women, which is in lineith the latest breakthroughs in the literature. Thisan be related to a greater concentration of leptin andnterleukin-6 (IL6) in the umbilical cord of babies deliveredy obese mothers, which seems to be in relation to a higheresistance to insulin and long-term metabolic disordersmong these newborn children, according to Catalano andhankar studies.5