“Blessed in my own way”: Pedagogical affordances for dialogical voice construction in...

Transcript of “Blessed in my own way”: Pedagogical affordances for dialogical voice construction in...

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139

‘‘Blessed in my own way:’’ Pedagogical affordances for dialogical

voice construction in multilingual student writing

A. Suresh Canagarajah *

Departments of Applied Linguistics and English, Pennsylvania State University, 303 Sparks Building, University Park, PA 16802, USA

Received 21 June 2013; received in revised form 1 September 2014; accepted 3 September 2014

Abstract

While the theoretical orientation of voice as an amalgamated dialogical effect has received consensus in second language writing

circles, classroom practice and research have not kept pace with these developments. This article reports the trajectory of a Japanese

student in negotiating the classroom affordances provided by a dialogical pedagogy to construct her desired voice. Analysis of the

ways this pedagogy facilitated awareness in the student and progressive understanding in the teacher suggests implications for a

pedagogy of voice. The study unveils the components that are amalgamated, process of dialogicality, and the challenges in

achieving a co-constructed voice.

# 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Though voice is a young field of scholarship in multilingual writing, second language scholars have gained from

poststructuralist theories to formulate a complex perspective. As recent publications on the state of the art show

(Sancho Guinda & Hyland, 2012; Tardy, 2012a, in press), orientations to voice as amalgamated of diverse textual and

extra-textual resources (Matsuda, 2001), dialogical of the personal and the social (Prior, 2001), and achieved as an

effect by readers (Matsuda & Tardy, 2007) have gained acceptance in the field. The provenance of these metaphors is

obvious. That identities are multiple (Peirce, 1995), multimodal (Gee, 1990), negotiated (Bakhtin, 1981), and

constructed (Goffman, 1981) has been widely discussed in poststructuralist circles in diverse disciplines for some

time. However, such theoretical discourse among multilingual writing scholars has not been matched by effective

pedagogical applications or empirical research. Tardy (in press) points to the irony ‘‘that many studies on identity and

voice that are influential in second language writing actually examine L1 writers and/or texts rather than L2 writers’’

(p. 18). Therefore, she has called for more research on how multilingual writers draw from diverse cultural and

linguistic resources, especially in classroom contexts, for voice. Such a research agenda will provide more complexity

to ongoing definitions of voice, informed by actual experiences of teachers and students.

* Tel.: +1 814 865 6229.

E-mail address: [email protected].

URL: http://www.personal.psu.edu/asc16/

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2014.09.001

1060-3743/# 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 123

Pedagogical practice is marked by other inconsistencies. Jeffery’s (2011) interview of secondary school teachers

reveals that a majority of them still hold an expressivist orientation to voice despite the theoretical dominance of social

and dialogical models. Matsuda and Jeffery’s (2012) textual study of assessment rubrics (in tests such as TOEFL,

IELTS, and SAT) shows that voice is inadequately operationalized, even though statements of writing outcomes (such

as those of Writing Program Administrators) increasingly make a place for voice. Outside the United States, we find a

similar inconsistency. Through interviews with master’s degree students in Central Europe, Petric (2010) found that

the most frequent conceptions of voice were individualistic, based on expression of opinion, authorial presence, and

personal experience. This theory/practice disconnect is partly attributable to the fact that teachers have not benefited

from research in multilingual pedagogical contexts to inform their practice. The existing studies on voice focus on its

textual features (Hyland, 2012; Matsuda & Tardy, 2007; Tardy, 2012b). Others focus on the broader construct of

identity in L2 contexts outside composition (Harklau, 2000; Peirce, 1995; Starfield, 2002). While some of the textual

studies focus on reader perceptions, Tardy (2012b) argues for the need to move beyond texts and readers to the full

writing ecology in which voice is negotiated.

In charting such a course for voice studies in multilingual contexts, Tardy (in press) makes a special case for

classroom ecology. Observing that ‘‘surprisingly few studies of voice are situated in classrooms’’ (p. 17), Tardy calls

for practitioner research. She argues, ‘‘Future research that examines how instructors construct voice through the

writing of their own students could help broaden an understanding of the influences on voice construction when there

is an existing relationship between the reader and writer. In addition, classroom-based studies of voice may help to

shed more light on pedagogical techniques that aid students in developing control over their written identities’’ (p. 17).

In this article, I describe how a dialogical pedagogy I adopted, with an ecological orientation to the learning

environment, helped my students construct their voices. Focusing on the trajectory of a Japanese student, whom I call

Kyoko, I explicate the types of negotiations and affordances that helped her develop her voice. Integral to her voice

construction was my own influences and negotiations as a teacher in facilitating relevant affordances. In focusing on

this classroom co-construction of voice, I hope to clarify the complex negotiations that teachers have to take into

consideration in designing their pedagogies for multilingual writing. Before I discuss my pedagogy and research

method, I outline how I operationalized the dominant theoretical constructs for my classroom purposes.

Uncovering dialogical voice

Teachers influenced by the notion of voice as an amalgamated dialogical effect will be left with the following

practical questions as they design their course:

1. W

1

sub

hat are the components amalgamated in voice?

2. W

hat is the nature of the negotiations that characterize dialogical voice?3. H

ow do interlocutors (i.e., teachers, peers) mitigate their appropriation of writers’ voices in the achievement of‘‘effect’’?

Though Matsuda’s (2001) treatment of voice as amalgamated reveals how discoursal and non-discoursal (i.e.,

citations) features contribute to voice, there are diverse other components that other researchers have identified.

Kramsch and Lam (1999) identify personal identity and social identity as separate from textual identity (which

corresponds to voice). Ivanic (1998) has classified the diverse textual identities of a writer that require amalgamation:

i.e., the autobiographical self, discoursal self, self as author, and possibilities for self-hood. However, Tardy (2012b)

further points out that while textual components of voice have been discussed well, extra-textual components have not

been studied: ‘‘While scholarship has drawn attention to the ways in which voice (as self-representation) is constructed

through text, we still know little about how aspects of a writer’s identity beyond the text (e.g., sex, age, and race) may

influence voice construction’’ (p. 65).

In this article, I adopt a heuristic featuring identity, role, subjectivity, and awareness to explore how such

‘‘identity[ies] beyond the text’’ find amalgamation in the textual voices of multilingual students.1 Though there are

I develop this heuristic from a model constituting identity, role, and awareness in the theorization of voice by Kramsch (2000). I added

jectivity to address ideological considerations in voice. For a detailed discussion, see Canagarajah (2002), pp. 105–110.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139124

Text

Role

Iden� ty

Subjec�vity

Iden�t y

Role Subjec�vity

nego�a�on

Voice

READER

WRITER

Awareness

Awareness

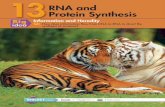

Fig. 1. Heuristic for voice analysis.

many theoretical debates on the constructs constituting voice (as demonstrated in the previous paragraph) and their

relationships (i.e., is voice part of identity, or vice versa?), I adopt an orientation that accommodates the

interrelationship of these constructs as a way of tentatively resolving such controversies for pedagogical purposes. An

exhaustive theorization of these constructs is beyond the scope and aim of this article. The objective behind my

heuristic is to help identify the interactions between the textual and extra-textual, unveil the diverse components and

relationships involved in voice construction, and track the nature of classroom negotiations to facilitate the practice of

teachers in multilingual writing.

In my heuristic (see Fig. 1 above), ‘‘identity’’ (as in Tardy’s, 2012b, restricted extra-textual sense) relates to features

such as language, ethnic, and national affiliations that are part of one’s history. Though we should not treat them as

monolithic or essentialized, we should also be open to the possibility that students might desire to represent their

heritage with pride or draw from it positively for fashioning their voices. ‘‘Role’’ is a social category and refers to

varying subject positions people are provided in institutions such as schools, workplaces, professional communities,

and the family. The roles one plays come with expectations about the voice one should adopt in communicative

interactions. Though the power differentials behind these roles can be renegotiated (such as graduate students earning

the authoritative voice that seems readymade for established scholars), one should still be mindful of the constraints in

negotiating one’s role. ‘‘Subjectivity’’ is an ideological construct and indexes the discourses that shape one’s voice, as

they find expression through genre conventions, communicative norms, and value systems. This construct might help

address the lack of clarity on how genre conventions and content knowledge in disciplinary discourses are

amalgamated in voice, which Tardy (in press) identifies as a limitation.

Though all three features above might appear to present constraints for the voice of the author, it is possible for the

writer to index his/her ‘‘take’’ on these through language. Kramsch and Lam (1999) make a case for including

‘‘awareness’’ as a reflective process facilitated by language and writing, in correcting Peirce’s (1995) sole focus on

social ‘‘identity.’’ The fact that language is creative and polysemous provides resources for writers to rise above

historical, social, and ideological impositions, register a reflexive awareness of their constraints, and adopt a strategic

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 125

footing in relation to them. Language choice can also index the author’s reshaping of identity, subjectivity, and role,

providing additional layers to voice at the microtextual level. In adopting this heuristic, teachers can explore how

students may negotiate constraint and agency, determinism and autonomy, and ascribed and acquired identities (which

Tardy, 2012a, reviews as dichotomies that have been debated in the field of L2 writing).

To move to the second question—i.e., the nature of dialogicality—this heuristic accommodates Bakhtin’s (1981)

notion of voice as polyphonous. Negotiation is made up of different, sometimes conflicting, layers. Authors have to

negotiate these layers to gain a measure of coherence. The voice components mediate, modify, and motivate each other

in the construction of voice. Providing even more scope for negotiation is the fact that voice also depends on the ways

readers and writers negotiate these layers. The negotiations with the reader—sometimes confronting biases and

impositions—can help writers develop a reflexivity and awareness of the multiple components of their voice. Burgess

and Ivanic (2010) develop a similar model of negotiation for the components of textual identities. They attempt to

show how diverse textual identities interact with each other, in relation to the reader’s conception of these identities,

helping writers renegotiate the components for further development.

In the ideal outcome of ‘‘effect’’ both authors and readers should move towards a co-construction of voice that is fair,

open, and sensitive to all the amalgamative components involved. However, as Ratcliffe (1999) has pointed out in her

influential model of rhetorical listening, such interaction requires a complex ethic of negotiation. Readers should engage

with the otherness of the author to move towards a more reflexive and critical understanding of texts. Her theorization

makes us alert to the many ways in which effect has to navigate the pitfalls of biases, ideological and cultural

conditioning, and appropriation. For this reason, Ratcliffe recommends relentless engagement—i.e., ‘‘ongoing’’

negotiations (p. 207)—with the understanding that interpretation is always evolving. Note the recursive arrow

characterizing the ‘‘negotiation’’ leading to voice in the heuristic. We have to also note that the voice effect of all these

components and interactions is shaped by the writing ecology. The features in each specific writing or pedagogical

context have a bearing on the nature of the negotiations. A different writing ecology would lead to different voice effects.

Pedagogy and research

The challenge for a pedagogy of negotiated (not prescribed) voice is that teachers have to be mindful of students’

investments, desires, and histories that will motivate them to write differently even as they manage their own

investments. Based on a longitudinal study of a Japanese student’s literacy development, which takes unexpected

trajectories, Spack (1997) argues that teachers ‘‘should be careful not to create curricula on unexamined assumptions

about what students will need to succeed’’ (p. 48). She argues that ‘‘we cannot safely predict’’ (p. 48) what texts and

activities will be most beneficial for one’s writing development. Furthermore, heeding Ratcliffe’s (1999) warning, I

would suggest that teachers should keep themselves open to hearing diverse layers in their students’ texts that both

challenge their biases and point to new textual possibilities. In consideration of these factors, I have found it useful to

adopt a less directive dialogical pedagogy that enables students to engage with the ecological resources in the

classroom to develop their texts and voices in their preferred trajectories.

An ecological orientation treats languages and literacies as shaped by the participants, processes, artifacts, and

structures (collectively labeled ‘‘ecological resources’’ by Guerrattaz and Johnston, 2013) in the classroom treated as

an ecosystem. These resources can serve as affordances for critical learning and literacy practice. Van Lier (2004)

defines affordances as: ‘‘what is available to the learner to do something with’’ (p. 91). To function positively as

affordances, ecological resources must gain uptake. Therefore, Guerrattaz and Johnston (2013) argue, ‘‘affordances

may either enable or constrain language learning’’ (p. 782). For this reason, Van Lier (1997) further defines

affordances as ‘‘signs that acquire meaning and relevance as a result of purposeful activity and participation by the

learner and the perceptual, cognitive, and emotional engagement that such activity stimulates’’ (p. 783). I will discuss

below the ecological resources I designed and the types of activities I orchestrated to help students appropriate them as

affordances. Affordances can lead to the emergence of new genres and voices. The concept of emergence in ecological

models adopts a complex orientation to cause/effect. Van Lier (1997) warns, ‘‘evidence of learning... cannot be based

on the establishment of causal (or correlational) links between something in the input and something in the output’’ (p.

786). For teachers and researchers, it might be difficult to isolate one pedagogical factor as leading to the construction

of voice. Several factors might act in dynamic and subtle ways to contribute to new possibilities.

The web-supplemented course on teaching second language writing that I taught for 14 advanced undergraduates

and early graduate students was primarily for teacher development. I designed the course as practice-based and

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139126

collaborative, as I assumed that writing and negotiating texts would help future teachers develop a reflexive awareness

of their own literacy trajectories and practices to develop effective pedagogies. Therefore, the main requirement for the

course was a serially drafted and peer-reviewed literacy autobiography (LA, hereafter). Though voice was not the sole

concern of the course, my expectation was that students would develop an understanding of their identities, engage

with scholarship on composition, and benefit from the collaborative process of composing to both practice and teach

writing effectively.

To clarify the objectives behind the writing activity, I mentioned the following in the syllabus: ‘‘a. by narrating our

own writing development, we can develop greater self-awareness about our literacy background and understand the

ramifications of the articles we read about writing with greater personal relevance; b. by analyzing our narratives

collectively, we develop a research knowledge on diverse writing trajectories and complicate published research on

writing development.’’ To facilitate such reflective awareness, the writing assignment was deeply integrated into the

classroom and course ecology. I provided ample opportunities for students to reflect on their evolving narrative and

construction of self. In their weekly journals, I asked students to write about the writing challenges and insights into

their literacy trajectory. I turned the essays into an exercise on narrative analysis, asking students to compare and

contrast all of them for thematic and/or stylistic findings. I gave appropriate exercises on the readings for the course to

be interpreted in the light of their narrative. Students posted at least six drafts of their literacy autobiography at various

stages of development into their online folder on the course website. The peers and the instructor were expected to read

the drafts and post their feedback into the author’s folder. The authors had an opportunity to respond to the feedback,

reflect on their writing challenges, and pose further questions in their weekly journal entries as they revised the draft

for another review. At the end of the semester, I asked them to write a reflective essay for their portfolio, tracing their

language awareness, composing practices, and rhetorical strategies during the course. While these exercises

encouraged students to engage with the diverse voice components (i.e., identity, role, subjectivity) in text construction,

they also enabled them to transmute the ecological affordances into textual voice.

Setting up the course as open to negotiations was an attempt to facilitate engagement with the classroom ecological

resources and help students adopt them as positive affordances. However, I also took care to provide access to

competing discourses and norms, as the negotiation depended on students’ expectations, objectives, and investments

to adopt the ecological resources for their desired ends. The dialogical process articulated above encouraged

interactions with one’s peers and the instructor—the participants in this course ecology. Learning from course

artifacts was also dialogical, with classroom discussions and group activities complementing reflection, journaling,

and writing on the Internet. The main course artifacts were three textbooks on second language writing (Canagarajah,

2002; Casanave, 2003; Ferris & Hedgcock, 2005). Though one of the books (my own Critical Academic Writing and

Multilingual Students) was motivated by critical theories and sought ways to affirm the values and norms students

brought with them, the other two books did not adopt this ideological position (though they were sensitive to the

concerns of second language students). I expected the latter texts to orientate students to the more established norms in

U.S. academic institutions and academic writing. These normative structures also indirectly (sometimes

unconsciously) informed teacher and peer feedback in the course. Students had to negotiate the dominant structures

in academic literacy for voice through their own strategies and motivation. Some of the artifacts that emerged through

the processes articulated above—such as the LA’s of other students, diverse drafts of one’s own writing, the journals,

and classroom assignments—also functioned as artifacts for affordance.

What are the implications of the prescribed writing genre for enabling students to negotiate voice? LA is a hybrid

genre that straddles the personal and the academic. It can find expression through a personal narrative, reflective essay,

creative nonfiction, or autoethnography, all terms I used in my course to clarify the genre. At the point of

autoethnography, the genre can accommodate introspective research on one’s memory, discourse analysis of one’s

literate artifacts, and library research to interpret the ramifications of one’s literacy development (see Chang, 2008).

While most students usually start their early drafts as a straightforward first person narrative, many are motivated to

develop their drafts into a thematically focused essay that accommodates research, theory, and narrative. LA motivates

students to negotiate the writing process ground up, trying out forms that suit their rhetorical objectives and

experiences. The reflexive nature of the genre also invites negotiation. When students reflect on ways their voices were

shaped by conflicting language and cultural influences in their literacy development, it is understandable for them to

consider the implications for the voice in this very essay. Students were mindful of the performative nature of their

writing and experimented with accommodating resources from their learning history. It must be acknowledged that

many students were new to this writing. They developed their awareness of the genre in practice—i.e., as they engaged

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 127

in writing. However, at the beginning of the course, I offered one of my own literacy narratives (Canagarajah, 2001) as

an example and also presented the definition and heuristics for LA by Belcher and Connor (2001, pp. 185–188) for

guidance. In all of them, the emphasis was on LA as a hybrid genre that merged the personal and the scholarly,

narrative and analysis, as suitable for academic contexts. In accommodating the personal into the scholarly, I hoped

that students would become sensitive to the fact that all academic genres are hybrid, inviting a negotiation of different

texts, codes, and voices, with a personal engagement to discover the appropriate mix.

My adoption of teacher research displays both the benefits and limitations of naturalistic inquiry. I have not

experimentally manipulated or controlled specific features of student voice for research purposes. However, the

trajectories and strategies of negotiation adopted in the light of these mediating features will suggest intuitive

approaches students might adopt for voice. In fact, all 14 students in this course adopted different strategies for voice

(as reported in Canagarajah, 2013). In addition to Kyoko, the class included seven other multilinguals (namely, Abdul,

Buthainah, and Fawzia [from Saudi Arabia], Chang [Taiwan], Qin [China], Nurdan [United Arab Emirates], and Eunja

[Korea]), and six who claimed English as first language (namely, Tim, Rita, Chrissie, Christie, and Cissy [USA], and

Mark [Canada]).2 In focusing on Kyoko’s development in this article, I am not promoting hers as the only option, but

unveiling with greater specificity one of the most dramatic shifts in voice to theorize the intricacies of such negotiation

and the possibilities in this pedagogy.

The design of the course and assignments helped me gather multiple forms of data on classroom negotiation of

writing. In addition to the serial drafts (identified below as D1, D2, etc.), students’ weekly journals (abbreviated as J),

classroom activities (A), peer commentary (PC), and interviews (I) provided further insights into their attitudes and

strategies. My own negotiation of meaning with the students (teacher feedback, TF) educated me on their rhetorical

options and helped me problematize the effect. I am not claiming that my research elicited spontaneous or intuitive

responses from my students. The very process of research enabled students to develop a better informed and articulated

position on what they were doing. Thus the research procedure and pedagogical practice fed into each other, in the

tradition of teacher research (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004; Nickoson, 2012). This method enabled me to learn from

students’ interaction styles and motivations to progressively refine my teaching practice.

Teacher research encourages us to acknowledge the significant role instructor identities play in student writing and

learning outcomes. Understanding the place of their own values in students’ negotiations will help teachers manage

their role appropriately. As it can be expected from the heuristic above, my own voice is characterized by tensions that

need to be situationally negotiated. As a multilingual scholar, former ESL student, and Asian, my identity is in many

ways similar to Kyoko’s and other multilingual students. My experience as a multilingual writer enabled me to provide

feedback that encouraged agency, and it is possible that students felt comfortable experimenting because of my

identity. However, my role as a teacher invests me with institutional power and makes me represent dominant

educational discourses that can be in tension with my multilingual identity. Furthermore, my subjectivity is

considerably influenced by critical ideologies, as reflected in my composition textbook (see Canagarajah, 2002) and

my LA read by students (Canagarajah, 2001). This subjectivity can be in tension with my role. The negotiation of these

dimensions of myself, especially with students in classrooms, can lead to a new awareness about my own values and

voice. Kyoko sometimes resisted my intervention, motivating me to critically reflect on my values and moving me to

alternate positions. While I focus primarily on Kyoko’s voice development in this article, I address my own teacherly

negotiations and changed awareness as a secondary theme.

Though I admit that my curriculum, identity, and writings may have influenced students to negotiate their voices in

ways specific to my course, my position is that pedagogy is not neutral. The unique conditions in each classroom, as in

all contexts of writing ecology, have to be negotiated by students for voice. Tardy (2012b) sees precisely this situated

engagement of the instructor as the value of teacher research, ‘‘examining both textual and embodied interactions as

they co-mingle in instructional spaces’’ (p. 92). As Kyoko’s writing is considerably shaped by my own pedagogical

framing and activities, her voice would have been different in a course taught by another instructor.

I present my research report as a narrative, drawing from the methods and assumptions of narrative inquiry (see

Clandinin & Connelly, 2004). Teacher research has often been reported in narrative form, as it is suitable for

representing the holistic, contextualized, and embodied nature of teacher/student negotiations as they evolve

temporally in a given course. It can also permit the personal voice of the teacher/researcher in representing the

2 These are pseudonyms. Consent was obtained from all the students in this course for reporting the data, following IRB approval.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139128

engaged, affective, and insider orientation of the experience. However, texts and voices of teachers and students can be

coded for grounded theorization. Narrative scholars have promoted coding procedures to identify emergent themes

(see Pavlenko, 2007). I coded all the discursive data (i.e., students’ drafts, interview statements, surveys, journal

entries, and teacher/student feedback) to identify the relevant voice components and negotiations. As scholars in

grounded theory would argue, our own agendas and assumptions considerably shape the coding process (Clarke,

2005). My analysis was recursive, as I interpreted the coded data by shuttling between my evolving heuristic (outlined

earlier), scholarly discourses on voice, and classroom interactions.

I must emphasize that the interpretation I offer of Kyoko’s voice is my construction, based on my vantage point in

the course. Though I had the advantage of checking my interpretation in relation to other data where Kyoko

metapragmatically comments on her own attitudes, intentions, and trajectories, I am not claiming objective truth. As

readers will see from the narrative to follow, Kyoko looked back at her development in her journals and interviews at

various points throughout the course. Since LA is reflexive, her essay also comments on her intended and achieved

trajectories in writing and voice. In addition, I also interviewed her and other students at the end of the semester on

their writing trajectories. Yet, I make my own education on her voice development and my discovery of the different

layers in her text an important theme in my narrative below. In other words, I am problematizing the shifting nature of

my interpretation of her voice in this report.

What kind of validity does a teacher’s representation of his own influences on and perceptions of a student’s voice

claim?3 Is the depiction of Kyoko true of her voice in all her writing or of all multilingual students? As in other reports

of teacher research and narrative studies, the type of validity claimed for a qualitative study is different from those in

traditional positivistic research. An important consideration is credibility (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004, pp. 366–371).

To the extent possible in a research article, I provide the diverse artifacts of Kyoko’s writing and course interactions

together with my changing interpretations, which readers are encouraged to triangulate for a more complex

representation of voice negotiations. Furthermore, such research aims for catalytic validity (Lankshear & Knobel,

2004, pp. 366–371). That is, its usefulness lies in the extent to which it promotes changes on the ways we look at

student voices and our pedagogical practices, in order to design more effective and fair courses. In keeping with my

orientation to dialogicality and effect, I emphasize that teachers have to critically reflect on their influences in writing

classrooms and keep their minds open to discovering the polyphony of student texts. An understanding of the nature of

these negotiations will help teachers design ecologically rich courses with suitable affordances, as I outline in the end.

Kyoko’s trajectory

Kyoko was a Master’s degree student in TESL (Teaching English as a Second Language), during her fourth and

final semester in the United States. She had completed a bachelor’s degree with a major in linguistics in Japan. She had

studied English as a foreign language at high school under Japanese teachers, and a college level course on English

composition under an instructor from the United States. She had also done a more advanced course on writing in

Japanese and written a BA thesis on a topic in applied linguistics in English under a Japanese instructor with graduate

training in the United States. Her early schooling had involved more personal writing in Japanese under Japanese

instructors, which she considered more creative and engaging compared to her later academic writing in English and

Japanese, which were very form-focused. Kyoko was interested in returning to Japan to pursue a teaching career, and

departed soon after graduating. She always identified herself as an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) student and

teacher, and considered her professional development from that point of view. Her LA has to be read in the light of her

developing professional identity and gradual mastery of the disciplinary discourses of language teaching. The LA

provides her a way of bringing together the knowledge she has developed in the courses, featuring both theoretical

discourses on language acquisition and pedagogical discourses. We must bear in mind that Kyoko’s representation of

Japanese and English literacies are her own, and cannot be generalized to other Japanese students.

Kyoko’s early LA drafts and journals suggested some diffidence and a search for directions. For example, in the

first exercise where students were asked to write a paragraph on their theory of writing, Kyoko added a surprisingly

personal note about her own status: ‘‘I’m in the middle of taking in North American academic discourse, and I have

been struggling with how I express myself in L2 writing. I feel like being in the middle of nowhere when I write in

3 Since Kyoko left the university soon after her graduation to teach in Japan, I have not been able to share this report with her for a member check.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 129

English’’ (A, 09/08). ‘‘Middle of nowhere’’ is a phrase she will repeat a few other times in her early journals and

drafts. Kyoko’s drafts adopted a chronological progression in the first-person, starting with childhood language

learning, proceeding to personal genres, and concluding with academic genres in Japanese and English. She opened

as follows:

4 Da

For me, wiring [writing] always associates with pain and embarrassment. When I imagine my journal to be

accidentally or intentionally read by someone, I cannot stop worrying. I would prefer reading others’ voice to

writing my voice. After all, I’m too self-conscious to keep on journaling. So, have I had excessive self-

consciousness since I was born? (D2)4

I was struck by Kyoko’s expressed discomfort with her own voice. I wondered if Kyoko was aware of the way

dominant discourses in Anglo-American academic contexts might cast such identities as passive. Though she was

honest about her feelings toward English and resisted the optimistic outlook most students typically present in the

beginning to impress their instructors, the repeated mentions of discomfort made me associate them with the diffident

Japanese identity which has been discussed widely in composition scholarship (see Atkinson, 1997; Fox, 1994).

Though her linguistic/cultural tension resonated with my multilingual identity, my role as the teacher and my

subjectivity as a critical practitioner influenced me to consider ways of nudging Kyoko towards a more agentive and

critical voice.

In an effort to intervene, I posed the following questions on Kyoko’s draft and posted them in the electronic

discussion forum for a large group discussion:

How is Kyoko presenting herself through these statements? Would you consider this passive and deferential?

Does this attitude characterize her whole essay?

Is there indirect criticism here [i.e., of American pedagogies and discourses]? Can she develop this further?

Would a more critical attitude make this essay better? (TF, 10/27)

The questions reveal my ideological bias. I am assuming Kyoko’s writing to be uncritical, perhaps influenced by the

professional discourse that Asian students may have difficulty in adopting a critical stance. However, her peers read

Kyoko differently. Chrissie responded: ‘‘I see multiple selves in Kyoko’s writing or multiple identities—Japanese,

middle child, good student. Although these are obvious to me she doesn’t talk about them explicitly in the context of

identity’’ (PC, 10/27). Tim reflected on the extent to which Kyoko can be critical in institutional relationships,

considering the student roles she was socialized into in Japan:

There is the issue of desirability (what does the teacher [want] and what can I do to get a positive response) bound up

in the identities we take on in these situations (student v teacher, employee v employer). Beneath or underscoring

these relationships is a power contrast; the consequences of ‘‘dissent’’ involved in these scenarios may be

disapproval, shame, embarrassment, or ostracism, making us uncomfortable to challenge the dynamic. I feel that

these exist (for myself and perhaps Kyoko) no matter how ‘‘cool’’ or ‘‘open’’ a teacher/boss is. (PC, 10/27)

Tim is pondering on the ways one’s social roles mediate voice. In other words, Kyoko’s identity and subjectivity

have to be considered in relation to her student status—and how that role is defined in Japan and in the United

States. Tim frames this beyond the native/nonnative dichotomy, as he says that he experiences such role constraints

himself.

Such interactions encouraged my rhetorical listening. I was reminded of the layered nature of Kyoko’s writing (i.e.,

the way identities, roles, and subjectivities mediated each other), and I began to focus on other voices represented

besides the national/cultural that I had highlighted in my response. I gradually shifted my own position on criticality in

voice. Kyoko responded to our feedback directly in her journal responses and indirectly in her revisions (as I will

demonstrate below). This dialogical process served to encourage Kyoko’s greater involvement in writing. When we

engaged thus with the diverse ecological resources in the course, Kyoko turned them into positive affordances for

voice construction, and her peers and I reconfigured our stance towards her voice.

ta is slightly edited for clarity.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139130

Between roles and identities

The course artifacts helped Kyoko’s negotiation of her heritage identity in relation to her student and professional

status. Consider her reflections after she read the section on contrastive rhetoric (in Chapter 3 of Canagarajah, 2002,

abbreviated by Kyoko in her journal as CAW for Critical Academic Writing and Multilingual Students):

In my opinion, the notion of critical itself is very western culture originated. Japanese doesn’t have the exact

counterpart word of English ‘‘critical.’’ Of course we approach to one thing from diverse perspective in our own

way, but, I don’t know why and how, there must be something different between two language cultures. As

western democracy does not fit all the country, the concepts of intelligence, critical, negotiation, rights, and

education might be slightly different in each culture. (J, 10/16)

Kyoko considers how the notion of critical as presented in textbooks can be ethnocentric. She draws an analogy from

other concepts, such as democracy and rights, to consider how criticality might be realized differently in different

communities. She begins to formulate how Japanese students might engage in critical and objective thinking ‘‘in our

own way.’’ To accommodate this possibility, she redefines criticality broadly as ‘‘approach to one thing from diverse

perspective’’—i.e., resembling triangulated thinking. I wondered if Kyoko was speaking back to me in writing this.

Was she indirectly pointing to different realizations of criticality in different students, as an answer to my earlier

questions?

Kyoko takes this reflection further in her self-selected reading of the literacy biography by Connor (1999), a Finnish

professional, who narrated her trajectory of acculturating to American notions of voice. Kyoko initially chose this

reading as a model for her LA. The research component in the course also motivated her to look for additional artifacts.

However, Kyoko felt uncomfortable with the trajectory Connor charted for her literacy development:

She rejected her L1 background and has acquired a new identity as an American through her life in the US.

However, I am not her, obviously. Neither do I want to deny my history nor become a mini American. I cannot

smoothly sift [shift?] my L1 to L2 as Connor does. Am I wrong? Shouldn’t I mention too much about L1? What

should I do in writing autobiography? It’s not about language anymore. I thought reading other ESL writers’ writing

would help me make my ideas more clear, but in reality, I got confused more after reading Connor’s. (J, 10/27)

Kyoko adopts Connor’s narrative as a scaffold to develop her own position, and articulates what kind of voice she does not

like. Kyoko prefers an option that involves neither ‘‘deny(ing) my history’’ nor becoming ‘‘a mini American.’’ I see her as

recognizing that there are discoursal and voice implications beyond language proficiency when she observes that the

challenge for her is ‘‘not about language anymore.’’ In saying that it is not easy for her to shift ‘‘smoothly’’ from L1 to L2,

presumably in a linear fashion, she acknowledges the struggles in achieving an amalgamation of her roles and identities.

Kyoko articulates a way out of her ‘‘confusion’’ (a word she uses in the journal above and the one that follows)

when she reads another chapter from the textbook. The fourth chapter introduces five different options for voice,

labeling Connor’s as ‘‘accommodation.’’ Kyoko reflects on this chapter as follows: ‘‘Right after reading Connor’s

autobiography, I read CAW Chapter 4 to prepare for the last class. It gave an answer to my confusion. CAW refers to

Connor as one example of development of self in writing, and offers us with other four approaches. I understood that

my approach must be different from Connor as my first impression, and such divergence in expressing self might be all

right’’ (J, 10/27). The range of options presented in the chapter presumably helps Kyoko depart from treating Connor’s

approach as the one she should adopt. I see Kyoko as thus progressively engaging with the course artifacts to develop a

critical awareness of possibilities in voice.

As she continues her search, I see Kyoko gaining more confidence to retain the strengths from her heritage identity

in her writing. She reflects: ‘‘I’ve been struggling with how I position myself in L2 context. After coming to an ESL

setting, I realized how my literacy background is blessed in my own way. I am not taking over the L2 discourse but I’d

rather take advantage of this difference as an ESL speaker, which might be a reason why I mentioned a lot about my L1

literacy development’’ (A, 10/29). I discern here a more conscious resistance to adopting a voice that loses the

strengths and resources from her Japanese heritage. She begins to affirm the resources she brings from her first

language, and considers herself ‘‘blessed in my own way.’’ For this reason, she justifies the important place she has

given her L1 literacy development in her narrative.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 131

As she proceeds with reflections on her reading, she specifically identifies her in-between position as a worthy

alternative that might satisfy her preferences for voice. She develops this position in relation to the metaphors third

positions and transposition introduced in the textbook:

As long as I can refer to CAW chap 4, the concept of ‘‘third position’’ by Kramsh and Lam (1999) and the

responses from ESOL students by Canagarajah (1999) exactly represents my current situation. Therefore, I’m

planning to take the transposition approach at this stage. It’s difficult to be critical to analyze my own writing (A,

10/29).

The book defines transposition as a merger of competing discourses, in the writer’s own terms, to develop a hybrid

voice (Canagarajah, 2002, p. 116). Kyoko is thus opting for a voice that draws from her heritage, despite her awareness

of the dominant western/academic discourses that perceive Japanese writing as lacking criticality. However, she

engages with the preferred discourses of English academic writing in her merging of discourses. The trajectory of

arriving at this option suggests that she is adopting transposition because it resonates with her experiences and needs

(i.e., ‘‘internally persuasive’’ in Bakhtin’s (1981) terms). There are subtle pressures from the context that influence her,

though. As a future teacher of writing, she cannot be negative towards English writing. The very textbook she is

responding to is designed to develop a positive teacher identity and represents my voice. The tensions between her

different voice components might have also encouraged her to engage positively with the course resources. In her

readings and revisions, she wrestles with the competing claims between her heritage Japanese identity and her

academic roles (as a graduate student in the United States and future teacher of English). These negotiations lead to the

identification of a subject position (i.e., transposition) that I find more complex.

Kyoko’s evolving reflections influenced me to revise my own position on criticality. I realized that criticality has to

be encoded in ways consonant with our heritage values, which might differ from western notions of agency. Kyoko’s

position resonated better with my own multilingual background and heritage identity, as it gained positive uptake.

Subjectivity

Formulating a position on voice is one thing; finding textual representation for it in the dominant discourses of the

intended genre is another. Kyoko’s early drafts had suggested to me a preference for affective writing. As her writing

progresses, however, she seems to engage more with academic conventions and textual resources and integrates them

into her discourse. The shift to greater objectivity occurs gradually and through diverse affordances. For example, the

peer interaction may have helped her to gain detachment from her writing, look at her trajectory objectively, and find

alternate directions for development. In her fifth journal entry, she reflects:

This week I had a profitable experience of getting feedbacks for my literature autobiography. One of my biggest

concerns was whether my writing style in the autobio is appropriate for this academic context. [...] In my second

draft, I just described my memories of writing like talking to my friend. Then, I got stuck what to write my

current situation. . ..The comments from the class gave me a clue to explore the direction of my essay. I should be

more objective by referencing articles or by approaching to an event from other perspectives. . ..I mentioned my

appreciation in the class already, but let me say that again. Thanks for all for your powerful comments! (J, 10/2)

She is now critical of the conversational tone (‘‘like talking to my friend’’) in her early drafts. Wondering whether her

style is ‘‘appropriate for this academic context,’’ she considers if she ‘‘should be more objective.’’ Because the course

readings had defined LA as a hybrid genre that merged research, as suitable for academic contexts, her peers had asked

her more analytical questions on her narrative. I had also questioned the emotionality of her writing, which I found in

some places to be excessive. My academic role and subjectivity to its dominant discourses made me uncomfortable

with Kyoko’s level of emotionality.

Responding to such feedback, Kyoko incorporated references and citations in her article and developed a more

analytical orientation. She mentions in her journal: ‘‘In revision process of 4th draft, I tried to connect my story to

researches.... This time, I decided to cut intro and other tiny stories for coherence. Academic resources might have

helped me to narrow down what I am going to say’’ (J, 12/4). Other models of literacy development she encountered in

her reference readings probably enabled her to compare her own trajectory and represent it more clearly. In her

subsequent draft, she deletes the opening paragraph on her early journal writing and adopts a brief thematic

introduction, highlighting the thesis of her essay. She also omits many digressive vignettes and focuses solely on

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139132

academic literacy development. I applaud these changes: ‘‘You have developed your ideas better here. I like also your

citations. They are important academic texts’’ (TF, 12/4). I am thus revealing my genre biases favoring qualified

arguments and finessed feelings, nudging Kyoko further in this direction.

My attempts to suppress her emotional discourse are sometimes quite direct. In my feedback on her second draft of

autobiography, for example, I added a sarcastic note on her excessive display of emotions: ‘‘There are many directions

in which you can take this narrative. . . . And I cried a lot when I read some sections of your narrative. (No, I am

kidding. I am trying to respond like a Japanese writing teacher!)’’ (TF, 9/29). The last reference is to the feedback

Kyoko received from Japanese instructors, as represented in her narrative. My sarcasm may have conveyed to Kyoko

the biases against excessive emotion in academic discourse. In response, Kyoko cut down some very emotional

sentences from her narrative. She completely omitted the following reminiscence on her family car in the fourth draft:

‘‘While writing, my eyes were full of tears. It may be because I was so touched by recalling our dear old car, because I

couldn’t see the goal of the writing, or because I was too exhausted by long hour writing’’ (D3).

However, Kyoko didn’t give up emotive writing completely. She chose the extent of objectivity in her own terms.

Consider her response to my request that she theorize the importance she gives for feelings and make a case for this

kind of discourse in her literacy trajectory (TF, 9/29). I asked this question because I assumed that I should find a way

to validate her expressive discourse if it comes from her heritage culture, which resonated with my own multilingual

identity. In response, Kyoko provides some sources on Japanese educational tradition to show how the whole person is

addressed:

Since an elementary school classroom teacher addresses students’ whole personality, it builds an intimate

teacher-student relationship. Several researches (Lewis, 1988; Easley & Easley, 1981; Lee et al., 1996;

Stevenson & Stigler, 1992) state that Japanese elementary school teachers apply various approaches to

encourage students cognitive and literacy skills in various subject areas. (D6)

I interpret Kyoko’s argument as being that Japanese education addresses the ‘‘whole personality,’’ whereas the

pedagogies of English writing she has encountered have been product-oriented, formulaic, and functional. In this

sense, Kyoko is affirming the place of feelings in her writing. I also see an attempt to theorize empathy and subjectivity

here. Paradoxically, she constructs a relatively impersonal academic subjectivity through her citations on empathy.

Kyoko goes on to adopt a genre that is layered, opening it up for polyphony. Even though Kyoko acknowledged that

her LA needed to become more objective, she retained an emotional and poetic discourse. Her resistance to omitting

the following episode displays her preference. It remained with slight modifications in her final draft:

I knew I had no creativity in writing, and I was not brave to venture to disclose my shame.... On the final day of

the summer break, the day before the submission deadline, I finally settled down to work on writing. Facing

blank writing paper, I had been bewildered for a long hours by fingering with a pencil. Then, suddenly, one

unforgettable moment of the summer crossed my mind. . .. I decided to write about my bitter-sweet feeling of

saying good-bye to the old car and welcoming a new one. Once I got started to write, my deep and longer

attention span assisted me to drive a pencil. Noise around me got mused, light around me got dark, and time flow

stopped. I wrote, wrote and wrote as my heart tells. When I finished writing the last sentence, it was already at the

break of dawn. (D6)

Considering the rhythm and imagery in the paragraph, I consider the opening sentence a disarming move. Taken at

face value, the opening might be interpreted as typical Asian humility and self-abnegation. However, ‘‘I had no

creativity in writing’’ is contradicted in the actual episode this topic sentence prefaces. There is almost a mystical

quality in the inspired writing at night time that follows. Consider especially the parallelism and personification in:

‘‘Noise around me got [muted], light around me got dark, and time flow stopped. I wrote, wrote and wrote as my heart

tells.’’ The romantic discourse of an inspired lone writer driven by a compelling motive and emotional urgency is

something I see in other places in her LA.

What might have helped Kyoko retain her passionate and imaginative writing style were the positive comments she

had received from her peers. The instructor’s bias against feelings was countered by the uptake of her peers. For

example, Cissy wrote in response to the second draft of her autobiography: ‘‘In your literacy autobiography I see a very

poetic writing, especially when there is an emotional memory, and that is something I wish my writing could be more

like’’ (PC, 10/1). Similarly, Mark noted how the rhetorical effect was heightened by the self-deprecating framing:

‘‘The identity you write about in the start of the paper seems very different from the person who wrote such an

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 133

interesting and personal story’’ (PC, 9/30). It appears that Kyoko has triangulated the divergent comments from her

instructor and her peers and chosen the extent of emotionality in her essay. She thus displays agency in her discoursal

choices and subtle rhetorical resistance.

Kyoko’s revisions suggest to me an attempt to position herself as an insider in the academic discourse, with an edge

provided by the discourses from her heritage identity. The expressive discourse is qualified by the ‘‘academic’’ moves

(i.e., citations, greater objectivity), countering the impression of deficiency an excessive emotional investment might

convey. At the same time, she is able to rise above a potentially impersonal academic genre by making a place for her

preferred expressive discourses. This strategy enables her to achieve the transposition she identified as her option for

voice.

Kyoko’s resistance helped me revise my own position on feelings in academic discourse. In fact, my multilingual

and Asian identity had always experienced tensions in this regard with the purported objectivity of academic

discourse. Kyoko’s evolving voice made me consider favorably a higher threshold for feelings in hybrid academic

texts. I gradually relaxed my attitude and began to consider Kyoko’s subsequent drafts favorably.

Awareness

Paralleling the achievement of discoursal hybridity, I also detected an irony that develops gradually after a

somewhat straightforward and transparent narration in Kyoko’s early drafts. After noting ‘‘It’s difficult to be critical to

analyze my own writing’’ (A, 10/29; see above), Kyoko succeeds in detaching herself from her text. I see a more

dialogical approach to composing around the midterm, having represented her as lacking reflexivity earlier. Kyoko

embeds marginal comments, with questions about possible trajectories and rhetorical choices in her later drafts. She

clarifies the purpose of her questions in her cover note to her third draft: ‘‘To those who read this draft, please ignore

comments I inserted. I’m questioning myself by these comments’’ (J, 11/09). An embedded comment says: ‘‘In the end

writing is not for my joy but just for academic purposes. ‘The desire to be approved’ How do I make this part coherent

to other parts of the essay?’’ (D4). Such comments suggest to me Kyoko’s analysis of her preferred attitudes and their

implications for the academic voice. She also seems to be seeking ways of appropriately representing feelings in

academic discourses. The tensions between personal and institutional expectations suggest how her construction of

voice takes into account the structures of dominant academic and language norms. Notable in this development is how

the ecological resource of structure serves as a positive affordance. Even normative expectations (i.e., limited place for

feelings as expressed in my TF and some course artifacts) can have positive effects. They can help writers negotiate

hybrid and qualified discourses that take account of dominant norms.

Such reflexive engagement with her own drafts and ecological resources seems to lead to greater self-

understanding, a clearer articulation of her literacy trajectory, and a more strategic construction of the self. Consider

the concluding paragraph, where she summarizes her literacy trajectory:

My literacy development process started from a personal level, expression of my feelings, and then extended to

more complex and intellectual language production process. Through the socializing process via language, I

have acquired various registers in Japanese. Although these development processes mainly occurred within

schooling systems, the L1 literacy education addressed my whole personality development so that I was able to

internalize Japanese as my language. Entrance to English as a foreign language introduced me the forms of a

new language, but its learning process failed to offer me contexts to internalize its language production and

processing processes. Current ESL academic context has been limited to classroom and academic texts, and I

have never had a feeling provoking occasion yet. That is, English was more detached and still alien to me. In the

end, as a graduate student, academic writing is the final goal to master English. Perhaps, I am in the middle of the

shifting process of thinking in English from personal to objective, or from emotional to logical. And I don’t

know how long it will take for me to master it. (D6)

The paragraph delineates her literacy trajectory with a surer footing and clearer prose in comparison with her earlier

drafts. The ‘‘alienation’’ she experiences (a term she uses above and in the next excerpt) in English academic writing is

attributed important social and pedagogical reasons. English has been acquired for functional academic purposes,

unlike Japanese which performs diverse personal and social functions in her development. To make matters

complicated, English academic writing was taught to her in such a form-focused and product-oriented manner that it

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139134

failed to engage her. This distinction offered to me a reasonable explanation for her differing investments in both

languages. It also helped me understand her expressed diffidence in English writing earlier.

Yet, Kyoko’s attitude to English is now presented in more positive and constructive terms. She is not in the ‘‘middle

of nowhere’’ nor pessimistic about finding her voice in English, as she had mentioned in her initial drafts and journals.

She presents herself now ‘‘in the middle of a shifting process.’’ Her prose, informed by terminology related to the field

of applied linguistics—i.e., ‘‘internalize Japanese... learning process... language production and processing

processes... socializing process... registers... L1 literacy education’’—shows her developing a good understanding of

the field of study from her readings and interactions. In a sense, LA enables her to bring together her evolving

disciplinary knowledge from this and other courses in the MATESL program. At the culmination of her studies, she

gains an opportunity to represent that knowledge. The greater control over these disciplinary discourses also

contributes to the optimism and confidence I hear in this prose. More importantly, the process of writing could have

given her an opportunity to reflect on her discoursal challenges and adopt a critical perspective on her desired

trajectory. Her mature awareness is reflected in the fact that she has clearly identified the shifts she has to make to move

towards her desired voice—i.e., ‘‘from personal to objective, or from emotional to logical.’’ She concludes with a

humble admission of the progress needed to attain the voice she is fashioning in English: ‘‘I don’t know how long it

will take.’’ But she knows the direction in which she has to proceed to reach this objective.

Consider, in the light of this trajectory, the opening of her final draft which presents her thesis statement and a title:

Close Encounter of the Alien

Japanese is a part of my self. Japanese (L1) literacy development has addressed to my emotional, mental,

cognitive, social, and intellectual growth as a whole person. On the other hand, my second language, English,

especially academic writing is detached from my self. Possibly the current ESL discourse is limited in academic

discourse which mainly address to intellectual competence. (D6)

On my first reading, this opening played into the discoursal dichotomies of Japanese as personal, English as

impersonal; or L1 as self, L2 as alien. These dichotomies initially created an impression of her subjectivity as alienated

and deficient, confirming my bias at the beginning of the semester. However, I began to hear the way these sentiments

are mediated by other components of her voice, when I considered them in the evolving context. Consider, first of all,

her awareness. Kyoko is making a real observation of the investments of both languages in her life. The sentiments are

also informed by her student status/role in both languages, accompanied by their divergent pedagogies. Furthermore,

the romantic metaphor of organic unity between writer, language, and voice (‘‘growth as a whole person’’) informs

Kyoko’s sentiments. She claims this connection with Japanese but not with English. It appears to me, however, that she

is seeking this harmony with English also (as confirmed by the concluding paragraph quoted earlier). It is possibly

because of this preference that Kyoko comments on her detachment from English. In other words, Kyoko is not

affirming stereotypical dichotomies and identities that present one language as alien. She is rather seeking to transcend

such alienation through further investment, relevant pedagogies, and meaningful writing in English. Still, she is

seeking this investment while grounded in her heritage languages and literacies. As we saw in her evolving orientation

to the transposition approach, Kyoko is in fact taking ownership of her Japanese heritage and constructing a voice that

agentively accommodates it.

To appreciate the complexity of her awareness and confidence in voice, I had to also become sensitive to some of the

ironies in her discourse. The title for the essay, ‘‘Close Encounter of the Alien,’’ is enigmatic. Kyoko is perhaps

borrowing this metaphor from popular culture (i.e., movies related to aliens have had a special place in Japanese film

culture). The allusion playfully subverts the impersonality of the academic discourse. Furthermore, I wondered who

was referred to as ‘‘alien.’’ Is English or Kyoko alien? Both are possible in the context of her essay. Given the self-

abnegation in previous drafts, it is probable that she is referring to herself. It could be a frank acknowledgment of the

stressful positioning at the contact zone. She is not simplifying or romanticizing the linguistic and cultural encounter.

Yet, Kyoko also displays a capacity to laugh at herself. She is being playful and sarcastic.

Other places in the final draft also register an ironic tone, giving me evidence of Kyoko’s advanced reflectivity. This

is how she presents her learning when she moved to college-level English writing in Japan, which turned out to be

extremely formulaic:

Once I learned the writing rules of a particular school of thought in Applied Linguistics, it was quite smooth to

write a research paper since all I had to do was imitate their writing styles. Research design and implement

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 135

processes made me realize how to make up the findings ‘‘sound objective.’’ I gained some peculiar word usage in

the field from reading articles, and I made repeated use of these words as children do when they learned a new

vocabulary. My thesis advisor checked my draft a couple of times, and every time she said nothing but ‘‘you

were doing well.’’ The final draft was edited by the ‘‘Mac enthusiast’’ native English speaking teacher. It was

predictable that he corrected my all grammatical mistakes in detail. Of course, my findings were not one of the

major finding in the 21st century. And of course, nobody knows my BA thesis is well done (D6).

I had to guard against interpreting the expression of passivity in this paragraph as literal, motivated by my teacherly

biases and earlier impressions. Kyoko seems to be playing up the pedagogical practices and dominant discourses of

impersonal academic writing to her advantage. Writing a research article became ‘‘quite smooth’’ because all that she

had to do was ‘‘imitate’’ the form. These were tricks she learned to ‘‘sound objective’’—and her quotation marks show

that she is deliberately sarcastic. Sounding objective involved repeating the jargon belonging to academic discourse.

Repetition ‘‘as children do’’ is appropriate, as it turns out that the teachers were not engaging with her writing

meaningfully. The thesis advisor gives her perfunctory compliments. The American instructor (‘‘Mac Enthusiast’’)

edits only the grammar mistakes. Therefore, Kyoko resorts to parodying academic discourse, exploiting the limitations

in this product-oriented pedagogical approach. The fact that the writing activity lacked purpose is also indicated by the

concluding sentence where she says that the final product did not eventually matter to anyone. I hear her courage to be

self-critical and laugh at herself when she says that her research didn’t produce ‘‘one of the major findings of the 21st

century.’’ However, Kyoko’s criticism is so subdued and tone so deceptive that readers who are not sufficiently alert

might be misled, as I initially was. In fact, what I discovered was the outward maintenance of her good student (and

future teacher) roles and stereotypical Japanese passiveness, both of which are mediated by her critical awareness and

ironic prose, which represent her voice as complex and self-aware. In a sense, Kyoko is subverting the dominant

discourses on Japanese uncritical writing through her expression of performed passiveness.

At the end of the course, I was in a better position to appreciate Kyoko’s self-awareness and irony, revising my

earlier impression of her ideological and academic innocence. I wondered whether I had missed these acts of irony in

the beginning or whether Kyoko was also growing in reflexivity through the semester, gaining from the dialogicality

and ecology of the course. It is possible that both of us were growing in awareness through these classroom

negotiations.

Voice effect

Kyoko’s trajectory suggests that she is engaging with the pedagogical affordances and classroom ecology

agentively to develop a more informed, layered, and hybrid voice. While she moves considerably closer to the norms

of English academic writing in North American universities, she merges resources from her Japanese language,

education, and cultural heritage to provide a difference. Her progression is in line with the approach of transposition

she had identified for her voice earlier in the semester. I perceive her development as resulting from a negotiation of the

following components of voice. The components mediate and modify each other to facilitate reflexivity in Kyoko and

complexity in her prose:

Identity: Kyoko makes a space for her Japanese heritage in her English writing, providing it a qualified

representation within the dominant academic conventions. She shows a preference for more personal and expressive

writing, which she identifies as deriving from her formative educational and writing experience in Japan. Thus she

does not essentialize her identity as deriving from the whole of Japanese language or culture. However, this identity is

mediated by the genre conventions and institutional structures of academic writing, to provide a qualified layering and

critical stance in her discourse.

Role: Kyoko navigates pedagogical experiences spanning form-focused and personal writing and critical and

deferential stances, in English and Japanese educational contexts respectively, to develop a strategic academic voice.

Her evolving disciplinary knowledge and professional identity may account for her confidence. Her status in the

teacher education program probably gives her the investment to engage with the ecological affordances for

constructive positioning. She goes on to develop a subtle and subdued criticality in English academic writing that is

agentive in U.S. higher education but befitting her socialization in Japanese educational institutions as well.

Subjectivity: Despite her awareness of affective writing being treated as lacking complexity and, thus, silenced in

certain western academic genres, Kyoko adopts a hybridity that enables her to rise above this possible marginalization.

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139136

She charts for herself an in-between position beyond the dichotomies of feelings and objectivity to construct a hybrid

discourse. She also goes on to develop a position critical of what she perceives as western notions of criticality.

Awareness: Her evolving reflexive orientation to her own and her interlocutors’ writing preferences, marked by a

playful and sarcastic tone, demonstrate a critical awareness. This awareness enables a strategic construction of voice in

her narrative, taking account of the competing discourses at play. Her critical awareness enables readers to strive

beyond any stereotypical and deficient reading of her voice. Though I still see some limitations in her written products,

especially an insufficient grammatical control, her self-awareness persuades me of her growing proficiency and

promise of further development.

Voice: In effect, I see a writing that is frank about the writer’s preferences, rooted in her cultural/linguistic heritage

and socialization contexts, but also ironic, critical, and agentive. I recognize how the layers of her voice components

mediate each other to facilitate her awareness and writing complexity. Her voice finds representation as confident and

aware, assuring us of a constructive learning trajectory towards greater grammatical and textual control. I hear a voice

that is evolving and layered, resisting stereotyping or essentialization. More importantly, this is a voice that draws from

her own resources and preferences to confirm that she is indeed ‘‘blessed in my own way.’’

Pedagogical implications

In constructing this voice, Kyoko had to engage with the diverse layers of herself and with the classroom ecological

resources. The dialogical pedagogy facilitated such negotiations. I submit that the ecological resources and dialogical

interactions enabled Kyoko to become more aware of the tensions and possibilities among the diverse components of

her voice. We will consider Kyoko’s testimony on how her writing benefited from these affordances, before we analyze

my role as the instructor in negotiating her changes. Kyoko’s reflective comments in her portfolio and two final online

interviews confirm her awareness of her own trajectory (as delineated above) and the ways the pedagogical affordances

helped her in voice construction.

As we saw in the narrative above, Kyoko engaged with both limited and imaginative readings of her drafts by her

peers and her instructor, triangulated them, and treated them as scaffolds for her own evolving discourse. We also saw

how she engaged with the narratives of other students and scholars, and textbooks and reference readings, treating

these artifacts as affordances to shape her voice. The course-end interviews, reflection, and portfolio further facilitated

her reflexive understanding. They also show her own awareness of the ways other pedagogical resources helped her

metacognitive development. The connection between her reflexivity and the affordances is intricate. While the

ecological resources develop her reflectivity, her evolving awareness enabled her to turn diverse resources into positive

affordances. As Van Lier (1997) reminds us above, one’s investment and awareness are critical for turning ecologies

into affordances.

The focus in this course on learning trajectory and awareness building rather than on finished products had many

other positive consequences. For example, the portfolio enabled Kyoko to reflect on her interactions, trace her learning

trajectory, and adopt a critical orientation to her own writing. In her preface to the portfolio, Kyoko observed:

‘‘Looking back the trace of my learning of this course, now I can see an evidence of my knowledge construction and

intellectual interaction with peers.... I think our portfolio will be visible evidences of our thinking process. Also, the

portfolio is an evidence of collaboration with peers. Both teaching and writing are abstract concept, so we cannot fully

understand them by just reading articles and textbooks’’ (A, 12/10). I interpret the final statement as implying that

having an opportunity to reflect on one’s own literacy development in the portfolio enriches one’s understanding of

composition theory and teaching practice.

Her course-end reflections also reveal that the genre of writing has functioned positively. Kyoko observes,

‘‘Autobiography also makes our own literacy development tangible. Once we could see our own trajectory to academic

writing, we may be able to expect or understand our students’ academic literacy development process’’ (A, 12/10). In

providing students opportunities to explore and represent their writing development, LA has facilitated meta-cognitive

development. Kyoko further observes in the interview, ‘‘I think literacy autobiography is an effective tool to shift from

personal writing to critical writing. The writer can start from telling her own personal story, and then she can narrow

down to specific and objective perspective through revision process’’ (I, 12/10). In this manner, Kyoko feels that the

genre has enabled her to develop more complex and hybrid discourses, confirming my understanding of her trajectory.

She also valued reading the LAs of other students. The drafts of her peers suggested useful alternatives for negotiating

voice. She stated: ‘‘By reading other students’ experiences, I realized that wiring [writing] development is

A.S. Canagarajah / Journal of Second Language Writing 27 (2015) 122–139 137

interconnected to the development of their personality.... For example, some students mention about their religion’’

(I, 12/10). Others’ narratives appear to have empowered her and scaffolded her voice construction.