Between Religion and Nation in the Palestinian Diaspora (in Nations and Nationalism)

Transcript of Between Religion and Nation in the Palestinian Diaspora (in Nations and Nationalism)

Between religion and nationalism inthe Palestinian diaspora

MICHAEL VICENTE PÈREZ

Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

ABSTRACT. This article examines Palestinian refugee articulations of the Palestinianhomeland and struggle in relation to religion and nationalism. My contention is thatthe impact of Hamas’s electoral victory in Palestine is visible within the discourse ofPalestinians in Jordan. This discourse suggests a transformation of the meaning ofPalestinian nationalism in which religion is taking an important albeit complex role innationalism. Using the concept of intertwining, this article considers how Islam hasbeen intertwined with Palestinian nationalism in ways that have privileged particularideas about the national homeland and fight for liberation. While many suggest thatIslamist politics is incompatible with nationalism, this article takes the local discourseof refugees and argues that Hamas and its supporters have yet to abandon the frame-work of nationalism, although certain tensions exist.

KEYWORDS: Hamas, Jordan, nationalism, Palestinian, refugees, religion

Introduction

In 2006, Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip voted in favor of a newgovernment led by Hamas.1 The organization’s victory signaled a critical shiftin Palestinian national politics as the dominant party, Fatah, suffered its firstelectoral defeat since the creation of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA)in 1994. Many scholars have since examined the implications of Hamas’spolitical ascent for Palestinians living in the occupied territories (Baumgarten2005; Hroub 2011; Lybarger 2007; Usher 2006). Few, however, have consid-ered its significance for the millions of Palestinians living throughout theregion who could not participate in the national elections. Thus most of theliterature about Hamas and its supporters has shed little light on the organiz-ation’s importance for Palestinian refugees living in Jordan, Lebanon or Syria,and whose fate remains inextricably linked to the political future of the Occu-pied Palestinian Territories (OPT).

Drawing on two years of ethnographic research in Jordan,2 this articleexamines how Palestinian refugees in Amman articulate the meaning of thePalestinian homeland, struggle and nation. In particular, my analysis showshow Palestinian refugees frame the meaning of nationhood in ways that (1)intertwines Islam and nationalist ideology, and (2) underscores the significanceof homeland politics for the meaning of nationalism to one segment of the

bs_bs_banner

ENASJ OURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION

FOR THE STUDY OF ETHNICITYAND NATIONALISM

NATIONS ANDNATIONALISM

Nations and Nationalism 20 (4), 2014, 801–820.DOI: 10.1111/nana.12081

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

Palestinian diaspora.3 As such, this study highlights multiple issues relevantfor the analysis of religion and nationalism and the meaning of nationhood fordisplaced peoples.

Recent scholarship on the question of religion and nationalism suggestssignificant disagreement over what role, if any, religion can play in themeaning of nationhood (Brubaker 2012; Friedland 2002; Juergensmeyer 1994;Mihelj 2007; Smith 2000; van der Veer 1994). In areas of the Middle East, thepopularity and success of political organizations including Hamas andHizbillah have raised considerable suspicion about the national status ofMuslim political actors. My analysis engages these debates by arguing thatneither Hamas nor its supporters in the diaspora can be easily written out ofthe fold of nationalism. Rather, the discursive representations of nationhoodoffered by Palestinians in Jordan indicate a complex intertwining (Brubaker2012) of Islam and nationalism that underscores the possibility of a religiouslyinflected form of nationhood. By privileging ideas about the sacred ‘Islamic’homeland and the particular status of Muslims within the nation, Palestinianshave yet to undermine their nationalist agenda. Rather, they have onlyre-inspired their nationalist dreams of liberation and return through an inten-sified sanctification (Smith 1999) of the homeland and people.

Although my analysis considers the elite discourse of Hamas, I am ultimatelyinterested in the meaning of nationalism for non-elite Palestinians who identifyas part of the nation in the diaspora. In particular, I examine how ordinaryPalestinians articulate the nation in ways that are both reflective and constitu-tive of dominant ideologies in the field of Palestinian politics. Such a focusrepresents one contribution to the growing interest in what has been called‘everyday’ (Fox and Miller-Idriss 2008; Menon 2012) or ‘banal’ (Billig 1995)nationalism. According to this approach, understanding nationalism requiresattention to how national identities take shape among ordinary people; that is,how those for whom nationalists speak – the ‘folk’ (Smith 2000) – engagedominant conceptions of the nation. As Billig (1995) notes, attention to banalnationalism means attending to the ideological habits that enable the reproduc-tion of particular nation forms. Informed by these approaches, I examine howa displaced community living beyond the center of nationalist politics impli-cates itself in national debates and the Palestinian future. In particular, I showthat ‘nation talk’ (Fox and Miller-Idriss 2008) among refugees not only revealstheir ideological support for Hamas but, more importantly, their positioning asa displaced portion of the Palestinian nation. More than a simple endorsementof Hamas, the appropriation of the organization’s nationalist discourse amongrefugees reflects their particular status as a community stranded in refugeecamps still hoping for the liberation of Palestine and an opportunity to return.

Research context

My research began in 2006,4 less than two weeks before Hamas won a decisiveelectoral victory claiming 74 seats in the PNA’s 132-member parliament.5

802 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

Despite international disbelief, Hamas’s victory was no surprise. Indeed,several factors assured Hamas’s win long before the elections. One of thosefactors had to do with Palestinian frustrations over the failures of Fatah andthe Palestinian Authority. Between 1996 and 2004, for example, the Palestin-ian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PSR) suggested a steady decline insupport for Fatah (Shiqaqi 2006). At the heart of public concerns were issueslinked to governance and state-building including public services and corrup-tion. These issues reached their peak in the 2006 elections when PSR pollingsuggested that corruption, inadequate services, lawlessness and an inability toend the Israeli occupation led Palestinians to cast their votes against Fatahcandidates in a ‘protest vote’ (Hroub 2004; Milton-Edwards 2006; Turner2006; Usher 2006; Zweiri 2006). In addition to voter disapproval of Fatah, theorganization itself made several mistakes that weakened its chances ofwinning. One of its principal errors had to do with internal divisions. Prior tothe elections, Fatah failed to unify its own candidates despite warnings byhigh-ranking officials.6 Instead of running all candidates on a single list – asHamas did – divisions within the party resulted in multiple party lists and,consequently, a split vote (Milton-Edwards 2007).

While the protest vote gave certain advantages to Hamas candidates in theelections, it alone cannot account for its 2006 victory. Only a year prior to thenational vote, local elections in 2005 resulted in significant wins for the organi-zation. In areas of Ramallah and throughout most cities in Gaza, Hamascandidates took a majority of seats in elections that, to some extent, signaledthe rising popularity of the organization among Palestinians (Shiqaqi 2006;Zweiri 2006). Even before the 2005 elections, but certainly after that, Hamascultivated a positive image among Palestinians through the development of itsown institutional apparatus and its shifting political discourse (Chehab 2008;Hroub 2004; Mishal and Sela 2006). As Milton-Edwards (2007) noted, formany Palestinians, the motivation to vote for Hamas lay in its proven capacityas a sustainable organization and its already substantial network of social,religious, welfare and political activities in the OPT. Polling after the 2006elections support this view as the PSR documented governance and state-building as two of the top voter priorities. Moreover, contrary to its image asa militant organization, Hamas ran its 2006 campaign agenda on a ‘Changeand Reform’ agenda. Accordingly, it promoted itself not as a religious organi-zation devoted to the destruction of Israel but as a trustworthy institutioncapable of providing effective services and ending corruption (Hroub 2006).

The importance of Hamas’s ascent in the Palestinian territories notwith-standing, I was in Jordan. And while I was certain that the elections wereparamount for Palestinians in the OPT, I was unsure of its importance forPalestinians in Jordan. As I soon discovered, within Jordan’s refugee camps, adifferent kind of discussion was taking place. Glued to Arabic news networkslike Al-Jazeera and Al-Arabi, Palestinians closely followed the elections.Whatever the world had to say about Hamas, Palestinians were articulatingtheir own ideas about the new Palestinian government. For many Palestinians

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 803

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

I met, Hamas’s political ascent signaled new possibilities both politically anddiscursively. On the political front, refugees spoke optimistically about a newcourse for the Palestinian struggle for independence and, more specifically, thereturn of the refugees. Discursively, many Palestinians spoke in terms of a newnational framework in which Muslim political activists would play a certainrole. In other words, while Palestinians in the OPT judged Hamas according tolocal matters, in Jordan, the organization received a different kind of endorse-ment. As a Muslim political organization, Palestinians in Jordan believedHamas represented a new phase in the Palestinian national struggle. Accord-ing to their reading, which I will discuss below, Hamas was their newly electedleader of the national movement.

Religion and nationalism

The recent success of religious political actors throughout the world hasbreathed new life into the question of religion and nationalism (Hibbard 2012;Juergensmeyer 2009). While traditional scholars of nationalism have definednationhood outside of, or against, religious communal identifications (Ander-son 2006, Hobsbawm 1991), a recent stream of scholarship suggests otherpossibilities (Friedland 2002; Juergensmeyer 1994; van der Veer 1994).Juergensmeyer, for example, suggests that religion can play a constitutive rolein the formation of what he calls ‘religious nationalism’. What distinguishesthis form of nationalism from other nationalisms is the inclusion of a religiousperspective in the social and political destiny of the nation (Juergensmeyer1994: 6).7 The new religious revolutionaries, he claims, are not so much con-cerned about the political structure of the nation-state as they are with therationale for having one – its moral basis – and why it should elicit people’sloyalty (Juergensmeyer 1994: 6–7).

In a recent article in this journal, Brubaker (2012) argued against the idea ofa distinct form of religious nationalism. Whatever the nexus between religionand nation espoused by religious political actors may be, it must be groundedin the nation as the primary source of value, legitimacy, loyalty and identity(Brubaker 2012). It is for this reason that Brubaker rejects the idea of religiousnationalism presented by Juergensmeyer and others. In the particular case of‘Islamist movements’ like Hamas, he believes that working through the idea ofthe nation-state is insufficient for saying that they are working for the nation.Commitment to the idea of a modern state, in other words, is not the same ascommitment to the modern nation.

Despite his objections, Brubaker does not completely refuse the idea thatreligion can play a role in nationalism. According to him, religious ideas can beintertwined with nationalism in three particular ways. First, the religiousboundaries can be imagined as coterminous with national ones; that is, thereligious community is the nation. Second, religious and national boundariescan coincide but not so far as to include all co-religionists; such is the case of

804 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

Northern Ireland where the borders of the nation include all Irish Catholicsbut not all Catholics. A third kind of intertwining has to do with the religiousinflection of nationalist discourse. In this form, Brubaker suggests that ‘reli-gion does not necessarily define the boundaries of the nation, but it suppliesmyths, metaphors and symbols that are central to the discursive or iconicrepresentation of the nation’ (Brubaker 2012: 9). In this approach, Brubaker isnot alone. Smith (2000) has also explored this issue by highlighting the role ofreligion in the formation and maintenance of national identities. According tohim, ‘religious traditions, and especially beliefs about the sacred, underpin andsuffuse to a greater or lesser degree the national identities of the populations ofconstituent states’ (Smith 2000: 795).

Central to the approaches offered by Brubaker and Smith is an identifiablecommitment to the idea of the nation. Religion, in other words, is not neces-sarily antithetical to the nations it supports. Rather:

[Nationalism] and religion are often deeply intertwined; political actors may makeclaims both in the name of the nation and in the name of God. Nationalist politics canaccommodate the claims of religion, and nationalist rhetoric often deploys religiouslanguage, imagery and symbolism. Similarly, religion can accommodate the claims ofthe nation-state, and religious movements can deploy nationalist language (Brubaker2012: 16).

Thus whether the nation is imagined as a geographically bounded religiouscommunity, or a community that draws some of its strength and legitimationfrom religious resources, it nevertheless remains the orienting force behind thevision of community; that is, an imagined political community that is inher-ently limited, sovereign and characterized by a deep horizontal comradeship(Anderson 1991).

In the analysis that follows, I engage the debate over religion and nation-alism in the context of the Palestinian diaspora. By putting contemporarywork on Hamas in conversation with my own work among refugees in Jordan,I argue that within the Palestinian field of discourse, neither religion nor nationhas conceded victory. It is my contention that groups like Hamas, and thosewho support them, are engaged in a complex intertwining of ideas supplied byreligion – in this case Islam – that are radically shaped and acted upon withinthe ideology of nationalism. But this intertwining of religion with the ideologyof nationalism is not enough to distinguish it as a unique form of nationalismor to preclude its connection to the nation. It is, rather, a nationalism infusedwith religious meanings.

Hamas and nationalism

Since its founding, Hamas has proved to be a flexible and dynamic organiza-tion.8 At times reformist, at others militant, its essential character as a socio-political movement has been difficult to define in any certain terms. Perhapsmore challenging has been accessing a framework capable of accounting for

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 805

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

the movement’s shifting positions on the question of religion and nationalism.While some scholars have prioritized Hamas’s religious dimensions and thuslocated it within broader trends of what has been called ‘political Islam’ or‘Islamism’, I believe there are several factors that suggest the organization’sreligious hue is insufficient for fully negating its nationalist character. First,while Hamas employs a discourse saturated with religious references to theQuran, hadith and the concept of jihad, the target audience of this discourse isnonetheless confined to the Palestinian people. Put simply, Hamas is notspeaking to the Muslim umma9; rather, it is speaking particularly to PalestinianMuslims and more generally to the Palestinian nation. It wants to put MuslimPalestinians at the forefront of the national movement. Palestinian Muslimsthus represent a vanguard of the nation who, in virtue of their inventedreligious tradition and identification, have a critical role to play in the libera-tion of Palestine from Israel. In pragmatic terms, Hamas has also confined itsefforts to the geography of the national context. It has not, for example,directed its attacks beyond the borders of historic Palestine nor has it called forviolence against any other state but Israel. Its disdain for US support of Israelhas not compelled it to endorse Palestinian attacks on US citizens or govern-ment officials.

Hamas’s reformist and military approach to the struggle against Israel hasalso been defined within the limits of the Palestinian territories. It does notwork for a transnational reformation of the Muslim world in preparation fora global jihad against Israel and its allies. Rather, it works through a diversenetwork of charitable institutions in Palestine to support all Palestinians whilepromoting an Islamic reformation within Palestinian society (Roy 2011).While such a program has been interpreted by some scholars as an‘Islamization’, such an interpretation is not without complications. Hamaslocates the Islamic reformation of Palestinian society within a greater programof national liberation. Thus turning Palestinian Muslims toward a more pious(Islamic) lifestyle is inextricably linked to the struggle against Israeli occupa-tion and the Palestinian nationalist cause. As Hroub notes, the more ‘devoutthe individual is, the more self-sacrificing on the battlefield he or she will be’(Hroub 2006: 28)’. In this sense, religious reformation is understood as anessential step toward succeeding in the national struggle where secular organi-zations have failed. Finally, even the very distinction between what is defini-tively Islamic and what is definitively national about Hamas remains unclear.An analysis of Hamas’s discourse suggests that it is appropriating religiousconcepts in Islam for nationalist purposes. As Aburaiya has observed, since itsestablishment ‘Hamas [has] appropriated the goals of secular Palestiniannationalism, as defined by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) andother Palestinian organizations – the liberation of historic Palestine from the(Jordan) River to the (Mediterranean) by armed resistance’ (Aburaiya 2009:63). In a similar assessment, Baumgarten has argued that Hamas’s religiousdiscourse has never sufficiently negated its status as a nationalist organization.Whatever the Islamic underpinnings of Hamas’s positions may be, she

806 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

suggests that the organization has retained an ‘essential nationalism’ that,according to its own charter, is ‘part and parcel of its religious ideology’(Baumgarten 2005: 39)’.

To the extent that religious ideology can be distinguished from nationalismin Hamas’s discourse and practice, it is clear that neither is sufficient fortrumping the other. Indeed, an analysis of Hamas’s engagement with nation-alist ideology suggests that it has had a significant impact on the shape of itsreligious politics. Thus the idea that Hamas offers a distinct form of nation-alism seems untenable. Rather, it appears that Hamas is engaged in an inter-twining of religion and nationalism that, while privileging religious symbols,concepts and, at times, identifications, is nonetheless still committed to thenation and nationalist goals. Hamas can thus be described as a ‘blend ofnational liberation movement and Islamist religious group . . . [whose] drivingforces are dual, its daily functioning is biaxial and its end goals are bifocal,where each side of each binary serves the other’ (Hroub 2006: 26).

This duality is not only visible within the organization’s rhetoric and activ-ities in Palestine but, as I will show, it is also visible within the discourse ofPalestinian refugees in Jordan who identify with the organization’s articula-tions of a religiously inflected nationalism. In the following sections, I will thusmove to demonstrate the complexity of Hamas’s intertwining within the dis-course of Palestinian refugees living in the camps of Amman. My analysis willfocus on two particular themes that reveal the dense intertwining of Islam andnationalism: the homeland and the national struggle. By focusing on refugees,I seek to emphasize how ordinary Palestinians (non-elite actors) interpret andrepresent nationalist ideologies in ways that not only reflects the influence ofhomeland nationalism but also their active engagement with these ideologies.

Intertwinings

a. The Islamic national homeland: Muslim Palestine

The idea of Palestine as a land of religious importance to Palestinians has along historical record. Khalidi, for example, described the religious connota-tions of Palestine expressed in the Fada’il Al-Quds literature of the nineteenthcentury, which offered pilgrims and visitors information about Jerusalem andholy sites throughout historic Palestine (Khalidi 1998: 29). Since the 1990s,however, the religious value of Palestine has gained significant traction amongPalestinian Muslims. To a large extent, the increasing popularity of what hasbeen called ‘Muslim Palestine’ (Nusse 1998) can be attributed to Hamas.10

Playing a critical role in organizing social welfare and resistance activitiesduring the intifada, their intertwining of religion and nationalism has offereda compelling discourse for Palestinian Muslims seeking an alternative tosecular politics and a fresh approach to the conflict with Israel. Echoinghistorical conceptions of Palestine as an integral component of an imaginedprecolonial Islamic homeland, the idea of Muslim Palestine articulated by

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 807

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

Hamas stands as one of the most precise offered by any Palestinian nationalmovement. According to Article 11 of its charter, ‘the land of Palestine is anIslamic Waqf [Trust] upon all Muslim generations till the day of Resurrection.It is not right to give it up nor any part of it?’ (Maqdisi 1993: 125) Palestine’sunique Islamic character is further articulated in Article 14, where the home-land is described as an ‘Islamic land accommodating the first Qibla, the thirdHoly Sanctuary, [and] the place where the ascent of the Messenger took place’(Maqdisi 1993: 126).

In Jordan, such articulations were widespread among Palestinian refugees.In particular, the idea that Palestine was a sacred territory and that its libera-tion represented a sacred national duty was common among PalestinianMuslims when articulating their relationship to the homeland. During ourdiscussions, Rashid in the Baqa’a camp, for example, described Palestine inways that resonated with those offered by Hamas. Displaced in 1967, he andhis family lived modestly within a small corner dwelling that was walkingdistance from his shop. Rashid claimed that Palestine was of equal religiousvalue to him as it was to all Palestinian Muslims. ‘Praise to God’, he saidduring our discussion, ‘Palestine is our land and is an Islamic land’. ‘It is likea creed and (the) Al-Aqsa mosque is our sanctuary. Palestine will thus bedefended with our blood’. My discussions with Rıma, a Palestinian woman atan Islamic women’s center in the Nasr camp, resulted in similar ideas. Accord-ing to her, Palestine was a religious land with a specific connection to Muslims.‘All Muslims have a right in Palestine’, she said, ‘because Al-Aqsa mosque isthere; it ties us [Muslims] all to Palestine’. ‘There are muqaddassat (holy sites)in Palestine that makes it our Islamic land’. During a visit with Abu ‘Imran inthe Baqa’a camp, I asked him about the status of Palestine for the refugees.‘What’, I asked, ‘is the significance of Palestine for you as a Palestinian and forthe Palestinians in Jordan?’ Emphasizing his homeland’s religious value as anIslamic territory, he claimed that

Palestine is for all the Muslims and the Palestinian issue is [fundamentally] an Islamicissue. So this is more important than my existence as a Palestinian. But this does notnegate [the importance it has for a Palestinian]. We say that Palestine is not for thePalestinians alone. Palestine is for the Muslims. And we do not . . . we will not forgetPalestine. We did not and will not forget Palestine and we will remember it for the restof our lives and we will work for the sake of its return to its people – the legitimatepeople – in all the permissible [observable, in religious terms] ways.

These excerpts emphasize the significance of Palestine to Muslims and Pales-tinian Muslims in ways that privilege its sacred religious value. In particular,the designation of Palestine as an Islamic territory in these representationsreflects a sanctification of territory (Smith 1999) in which the faithful areinseparably bound to the land. It is thus a territory whose holy sites andlocation within an imagined Islamic precolonial geography establishes its con-nection and importance to all Muslims. As such, Palestine achieves a statusresonant with previous ideas about the territory that draw their significance

808 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

from its religious sites and history. Yet within this seemingly historic andreligious identification of a homeland for all Muslims remains a basic nationalclaim for Palestinian Muslims. To see how, one has to begin with the very ideaof Palestine implicit within these claims. The antiquity and religious impor-tance of Palestine’s holy sites notwithstanding, the specific geographic identi-fication of Palestine referred to above reflects a fairly recent idea. The Palestineof Hamas and Abu ‘Imran, in other words, is a modern one adapted to thelanguage of history. It is a Palestine constituted within the structures of theBritish Mandate and the creation of the state of Israel. It is also a Palestineidentified through the nationalist framework of those who fought for itsindependence during both historical periods. Thus one can say that the idea ofIslamic Palestine represents an imagined territory that, while deriving its valuefrom Islam, gains its identity through modern nationalism.

In addition, although the discussion of Palestine above suggests the mereidentification of a territory, the more important issue concerns the implica-tions of that identification. To say that Palestine is an Islamic territory is asmuch a statement about its meaning as it is about the duty one has toward it.As Abu ‘Imran indicates, Palestine’s religious status among Muslims meansthat he and others must work for the ‘return of its people – the legitimatepeople’. By ‘legitimate people’, it is clear that Abu ‘Imran is referring toPalestinians since its connection to the idea of return matters most for thosewho, like him, were forced to leave. In this sense, the idea that Palestine is asacred Islamic territory serves to legitimize Palestinians’ claim to that territoryand thus the intertwining of religion and nationalism become readily apparent.By emphasizing the homeland’s Islamic significance, in other words, Palestin-ians can claim the validity of their national struggle.

b. The indivisible homeland and the national struggle

Understood as a territory with religious significance, the idea of Palestineamong refugees also reflected an additional claim, namely that no authoritycould legitimately partition the homeland. Embracing the discourse of Hamas,Palestine was widely described as an Islamic waqf that could not be divided byany secular political authority. Consequently, political negotiations based onthe partition of Palestine in 1947 represented a violation of the basic unity ofPalestine as a distinct territory but also as an integral component of thebroader Islamic homeland. According to Rashid, for example, the Islamicimportance of the Palestinian homeland meant that the territory could not bedivided. As he stated:

Palestine is an Islamic land. There is no person anywhere in the world . . . that can rejectthis fact. [Palestine] is from the river to the sea.

‘Aqil, another Palestinian refugee I interviewed in the Hittın camp, rejectedany attempts by the Palestinian Authority to negotiate a settlement with Israelthat did not include the totality of Palestine. ‘Palestine’, he explained, ‘is an

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 809

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

Islamic land’. ‘It is not Jewish nor was it divided in 1947. Maybe the politiciansspeak this way but we know that this is not true. Palestine cannot be divided’.Here both Rashid and ‘Aqil stressed that Palestine’s religious status meantthat it cannot be divided by secular political decisions. Speaking against thepossibility of any settlement between the PA and Israel that entails partition-ing Palestine, their basic claim rested on the idea that the homeland is foreverfor the Palestinians and Islam makes it so.

Affirming the indivisibility of Palestine has to do with more than the Pal-estinian leadership; it also meant that, for these Palestinians, exclusive Jewishrule in the territory is illegitimate and that the struggle against Israel representsa duty incumbent upon all Palestinian Muslims. The state of Israel, in otherwords, cannot legitimately assert its authority in Palestine since its rule iscontrary to Muslim rights in the territory. As Shadi expressed during ourinterview in the Wihdat camp:

The Jews do not have the right to control or occupy our land even if we are not there.We reject their occupation . . . Palestine is part of the Islamic lands. Why did they comeand expel the people from Palestine and steal our homes and homeland?

According to Palestinians, the illegitimacy of Israeli rule in the homeland alsounderscores the legitimacy of armed struggle to liberate Palestine. In termssimilar to those expressed by Hamas, Ghassan, another Palestinian refugeefrom the camps, stated that:

The land of Palestine is an Islamic land. And regarding those that describe Palestine asa divided Arabic land, Palestine will not be returned by or through negotiations.Palestine will be returned by the power of arms just as it was taken. The Day ofJudgment will not come until the Jews understand the right of the Palestinian people totheir land. And this is a central point. Every Palestinian in the shatat [diaspora] knowsthis. And even the Jews know that Palestine will be returned to the Muslims.

For Ghassan, Palestine belongs to the Palestinians and its liberation will occurthrough the specific actions of Palestinian Muslims. The ‘Jews’ will thus‘return Palestine to the Muslims’.

Nadia, a Muslim Palestinian refugee active within a women’s center in theWihdat camp, also framed the struggle for Palestine in religious nationalterms. Palestine, she claimed, is an Islamic land and will be returned to its‘rightful’ owners.

100% of the ahadith [sayings of the Prophet Muhammad] say that Palestine will bereturned to us. Even if not during our generation or the next generation, or even thegeneration after that, Palestine will return to the following generation of Palestinians.There will be a generation [of Palestinians] to whom the God of all worlds will returnPalestine. By the will of God, we will struggle [jahid] for Palestine and it will return tous.

Nadia was careful to balance the general significance of Palestine to Muslimswith the particular significance of Palestine to Palestinians. Thus she believedthat the Prophet of Islam’s own words support the idea that Palestine will be

810 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

returned to a generation of Palestinians and by doing so, Palestine will returnto its original status as an ‘Islamic land’. Only through Palestinian Muslimliberation could Palestine become part of the larger Islamic homeland. This, inmany ways, resembled the claims of Arab nationalists working within theframework of pan-Arab nationalism. Like Nadia, many Arab nationalists helda particularist view in which the idea of a greater Arab homeland did notdissolve the presence of individual Arab nationalities. Rather, the integrity ofthe Arab homeland was sustained through the independence and unity of eachindividual Arab nation. Thus for Nadia and others, while the liberation ofPalestine will restore the integrity of an Islamic homeland, it will not cease toexist. Palestine will remain a distinguishable territory within the greater terri-tory of Islam.

c. The national martyr

Dying for the nation, according to Anderson, reflects ‘disinterested love andsolidarity’ (Anderson 2006: 144). It is an act grounded in the ideals of sacrificeand historical destiny and thus distinguishable from racism and hatred. More-over, as Smith (1999) has observed, martyrdom represents a critical dimensionof the sanctification of territory in which dying for the homeland constitutes asacred act for and by the people. Linked to the quest for liberation and utopia,the willingness to give one’s life for the homeland draws its strength from, andgives meaning to, the sacred territory for which one dies. In the history ofPalestinian nationalism, sacrifice has played no small part. Faced with ongoingwar, dispossession and occupation, Palestinian nationalism has committedinnumerable lives for the liberation of the nation and homeland. Among thePalestinians I worked with in Jordan, the idea of sacrifice for the liberation andreturn of the homeland to its people was a prominent theme that reworkedreligious conceptions of martyrdom within the context of national struggle.The religious connection between Palestine and Palestinian Muslims meantthat sacrifice or, more specifically, dying for the homeland, represented asacred duty. It was an act reflective of the religious value of Palestine and of thesacred nature of its liberation. Understood this way, Palestinian resistance waswidely constructed in terms that offered its fighters a particular religiousstatus. More specifically, insofar as the fight for national liberation was areligiously sanctioned national struggle, its mujahidın (fighters in the jihad)were granted the status of martyrs.11 During our discussions in the camp, forinstance, Nadia described the Palestinian resistance movement as a divinelyguided struggle of religious significance. To die for the cause of Palestine thusmeant that one died as a martyr.

Our goal [to liberate Palestine] is by the will of God. It is akharawı [pertaining to thejudgment day]: it is religious. Our end is by the will of God almighty because theProphet said that Palestine is for the Muslims and he who dies without his country is amartyr. And the Prophet said that he who dies without his family is also a martyr. Weare without Palestine, our homeland. If we die fighting for our homeland or die without

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 811

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

our homeland, then we are all martyrs. Whether with Palestine or without it, ourstruggle means we are the winners by God.

The idea that death in the struggle for Palestine earns one the status of amartyr has been a fairly consistent theme within the Palestinian strugglebeginning with the PLO. During the 1960–1970s, PLO fighters who gave theirlives in battle were honored as feda’iyın (those who sacrifice). Emphasizing thereligious status of a Muslim martyr within struggle for Palestine, however,Hamas crafted its own vision of martyrdom during the first Intifada: theistishadı (Abu Amr 1993; Abu-Amr 1994; Abufarha 2009; Hroub 2000).According to Abufarha, the creation and rise of the discourse of theistishadiyın (plural of istishadı) in the resistance movement created a newcultural space for the status of the martyr, one that occupies the highest, mostnoble ground in the Palestinian national struggle (Abufarha 2009: 10). In thissense, Hamas attempted to exalt the status of its own Muslim Palestinianmartyrs above those of secularists working within the national independencemovement.

The religious value of the national struggle for Palestine and the status of‘those who struggle fıl sabıl-illah (in the path of God)’ as martyrs articulatedabove was reflected within the da’wa12 activities of young Palestinians workingin the refugee camps. Several students I met who attended a college in Zarqa’said they promoted the message of Islam among Palestinians in order to‘remind’ them of their duty as Muslims in the national cause. Concerned aboutthe Jordanian authorities and the idea that their work represented extremism,these Palestinians often relied on more anonymous methods of communica-tion including the distribution of audiocassettes and multimedia CDs. Forexample, one of the students I met provided me with one of the CDs hisorganization distributed among Palestinians.13 On the disc were a variety ofmultimedia options including audio lectures by Hamas leaders, recitations ofQuranic excerpts and key Quranic verses for thikr,14 anashıd,15 photographsof the resistance in Palestine, and the position points of the organization. Oneof the more striking features of the disc concerned its attempt to situate thenational struggle of Palestine with a larger imagined ‘Islamic’ struggle against‘invaders’, ‘colonizers’ and ‘infidels’.

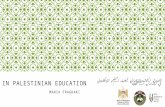

For example, in the organization’s position points shown below (Figure 1),the group articulated a call for a ‘return to Islam’ and promoted the vision ofa pan-Islamic struggle in which Palestine was but one site of a larger Muslimbattle. Titled thawabatna n’alnaha lakum (a clarification of our positions), thepage begins with the idea that deviation from Islam has limited Muslims’ability to deal effectively with ‘their’ issues. It then proceeds to underscore theimportance of intıma’, or attachment to the ‘homeland’, which according tothem, is a foundational brick in the unity of Arab Muslims (Al-WahdaAl-‘Arabıya Al-Islamıya). In this sense, the liberation of particular homelandsrepresented a duty necessary for restoring the integrity of the united Arab-Islamic peoples – a claim not unlike those of pan-Arab nationalists committedto the preservation of particular nationalisms. Although the idea of a united

812 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

‘Arab-Islamic’ people is suggested, the page goes on to describe the conditionsof non-Arab countries including Chechnya and Afghanistan as ‘bleedingwounds’ that Muslims must ‘remember [be aware of] and/or defend’. Reflect-ing the reformist strategy of Hamas, the position points conclude by statingthat ‘activism’ on the part of the students is necessary for the completion of a‘balanced personality’.

While this may seem an exclusively religious calling, as the CD goes on tosuggest, a ‘balanced personality’ has a much more important purpose. Spe-cifically, achieving moral excellence via an Islamic lifestyle is intimately linkedto national liberation. This directly represents Hamas’s intertwining of religionand nationalism. Educating Palestinian Muslims about Islam, as these stu-dents do, is much more than a religious imperative. It is a national imperativesince the liberation of Palestine cannot occur without a social reformation.Da’wa efforts, in this sense, are constituted within a nationalist paradigm inwhich moral and military training goes hand in hand: only the religious willsucceed in the struggle for liberation.

Whereas in the position page the students promoted a more generic visionof a pan-Islamic struggle against invaders in which the liberation of Palestineconstituted an integral albeit particular effort, the menu page (and followingpages) offered a much clearer appeal to Muslim Palestinians regarding therelevance of the national struggle and the importance of martyrdom. Forexample, in the menu page shown below, titled qadatna shahda’ (our martyredleaders), only two Palestinian martyrs are represented (Figure 2): Abdl AzızAl-Rantısı and Ahmed Yasın. In addition, while the figure depicted in thelower right-hand corner could be any Muslim fighter, it is clear that the imageis that of a Hamas fighter,16 which again emphasizes the Palestinian dimension

Figure 1. Position page of the CD.

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 813

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

of the struggle. Moreover, the first option in the menu specifically concerns themartyrdom of Al-Rantısı and Yasın. Within this feature, the CD provides anin-depth account of the two Palestinian leaders and their dedication andsacrifice (martyrdom) for the struggle. In the top center icon, titled sabahAl-Khair ya biladı (good morning my country), and the bottom right-handicon, titled ‘sawt Al-Watan’ (the voice of the homeland), Palestine againemerges as a prominent feature of the organization’s da’wa. In both cases,‘country’ and ‘homeland’ refer specifically to Palestine and thus furtheremphasize the centrality of the Palestinian national struggle in the imaginedpan-Islamic battle.

National ambiguities: Christians in Muslim Palestine

The Palestinian refugee camps of Jordan are diverse in the backgrounds oftheir populations. Despite such diversity, the majority of camp residentsthroughout the Kingdom are Muslims. This is not to say that Christian Pal-estinians were not refugees or displaced during 1948 or 1967. On the contrary,a significant population of Christians fled alongside their Muslim neighborsduring all of the major wars of Palestine. Yet these communities do not residein the refugee camps of Jordan and thus remain separate from the camppopulations. The result was that my discussions with refugees took a Muslim-centered approach that raised an important question about the status ofChristians vis-à-vis Palestinian Muslim national discourse.

During my interviews with Muslim Palestinians, I asked about the relation-ship between Christians and Muslims and the status of their claims to Pales-tine. The most common response concerned the idea that both religious

Figure 2. Menu page from multimedia CD titled ‘Our Martyred Leaders’.

814 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

communities shared the same origin and goals in Palestine. ‘Both Christiansand Muslims’, Rıma said, ‘suffered the same and thus felt the same about theirhomeland’. Similarly, Asad, a Palestinian refugee who worked at an Islamicorphanage, described the differences between the two communities as ‘trivial’.For him, both shared a commonality of experience and, more importantly, acommon goal: the liberation of Palestine and the realization of the right toreturn to the homeland.

The Muslim and Christian Palestinian share the same foundation and goal. There areno differences in our goals. We are from the same country and share the same struggle.Just as in Palestine, during the holidays, we still visit each other and share everything.There is no conflict between us.

Regarding the more specific issue of Christian Palestinian rights to Palestine,however, Palestinian Muslims offered an important qualification. As anIslamic territory, my interlocutors believed Palestine belonged to the Muslimsand thus could only be ruled by a Muslim government. Christians, as ahl-Al-Kitab (people of the book), had rights to their holy sites and, as Palestinians,had rights to live in their homeland. They did not, however, have the right torule over Muslims. During her discussion of the homeland, for example, Iasked Amal, a young Palestinian from the Wihdat camp, what she believedregarding the rights of Christians in Palestine. In a clear and assertiveresponse, she said:

Regardless of whether one is Christian or Muslim, they all have a right to their holysites in Palestine. There is no conflict between the religions. In terms of the Palestiniansin the diaspora spread throughout the world including Europe, even if he has British orAmerican citizenship, he carries in his veins [his Palestinianness] and in his dialect [heexpresses his connection to Palestine]. He is therefore a Palestinian and has his rights inhis homeland. But Palestine belongs to the Muslims. Since ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab‘opened’ Jerusalem, it has belonged to the Muslims.

For Amal, an individual’s origin in Palestine was sufficient for establishing herrights in the territory. Christian Palestinians thus had as much right to Pales-tine as Muslim Palestinians. But that right was restricted in religious nationalterms. As her comments illustrate above, insofar as Christians are Palestinian,they had a right to live in Palestine. Moreover, because they are Christians,they also had a right to their holy sites within Palestine. They did not, however,have the right to rule as an authority over the territory. That right, accordingto her, was the exclusive privilege of ‘the Muslims’ grounded in the Caliph‘Umar’s conquest of Jerusalem. Abu ‘Imran offered a similar answer to thequestion of Christian Palestinians. Although Palestine was a Muslim territory,he said, Islam did not preclude the rights of Christians or even Jews in Pales-tine. ‘They could live in Muslim Palestine without fear.’

First, the Christians are our brothers in humanity. They are our brothers as membersof the human family and Islam compels cooperation between all humans . . . they areall welcome.

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 815

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

The comments above suggest an interesting attempt to resolve a fundamentalproblem within the discourse of Palestinians concerning the unequal status ofreligious communities within the imagined nation. According to Abu ‘Imran’svision of Palestine, its identity as a Muslim territory did not negate the rightsof non-Muslim Palestinians to live within it. Palestinian Christians thus hadrights within Palestine both because of their religious status as people of thebook and as members of the Palestinian nation displaced from the homeland.Moreover, many Palestinians did not see the presence of Palestinian Christiansor even Jews in Palestine as a necessary source of conflict. Rather, theybelieved it was their idea of an exclusivist Jewish state in Palestine that contra-dicted the idea of Muslim Palestine. In addition, most Palestinians believedthat only through a return to Islam could Palestine be liberated. Consequently,Palestine’s liberation at the hands of the Muslims would bring about Muslimrule in the territory. Hamas, as the leading Palestinian national movement,reflected the closest approximation of an Islamic authority and their success inthe Palestinian national elections served to underscore the idea that onlythrough Islam could Palestine be freed from Israeli control. Finally, Palestin-ians conceptualized Muslim Palestine as a utopian ideal in which both Chris-tians and Jews could live in peace and as relative equals, yet subordinate to theMuslims. Insofar as the idea of Muslim Palestine did not represent anexclusivist form of Zionism, that is, the idea that Israel exists only for the Jews,the homeland was imagined as a ‘progressive’ ideal and solution to the conflictin general.17

The positioning of Palestinian Christians as unequal subjects in an Islamichomeland revealed a certain tension in the relationship between religion andnationhood as envisioned by Palestinians in the camps and in Hamas’s dis-course more generally. In particular, the idea of Muslim rule in Palestineunderscored the challenges of asserting the sovereignty of the nation whileprivileging the status of a specific religious community within that nation. Ittherefore revealed the inherent vulnerability of nationalism when intertwinedwith religion. Indeed, the subordinate status of Christians underscored theway religious identifications can mediate national ones. Thus despite the ideathat Muslim Palestinians were members of the Palestinian nation, their reli-gious identification gave them a privileged position vis-à-vis Christians. Thenation, in this case, was fundamentally unequal.

It is clear that these problems highlight the limitations of the kind ofintertwining among Palestinians claiming the discourse of Hamas. They revealthe challenge of making claims as and for the Palestinian nation while privi-leging the religious meaning of that nation, its homeland, and its struggle to itsMuslim members. These issues also point to the undefined vision of a Pales-tinian polity. In all of the discussions represented above, Palestinians did notassert any particular idea of what a Muslim-ruled polity would actually looklike. Offering Christians and Jews a place within a Muslim-ruled Palestine thusdoes not explain how these communities would participate in the governing ofthe state. Moreover, the lack of a developed idea of the future Palestinian state

816 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

underscores the marginalized location of a ‘nation’ far removed from the‘state’. Living in refugee camps for decades has meant that many refugeesemphasize a discourse focused on the nation more than on the state. Refugeesseem to be more concerned with a nationalism that can ensure a future returnthan with the state they will return to.

Conclusion

This article has taken the question of religion and nationalism from a localperspective among a displaced community of Palestinians in Jordan. In sodoing, it breaks with a tradition of analysis that takes nationalist leaders as thefocus of nationalism. Instead, I have examined how the recipients of nation-alist politics and discourse engage the field of nationalism and articulate theirown claims of identification. From this analysis, two particular points areimportant.

First, this article argues that the division in studies of nationalism has failedto adequately account for the complexities of religious national discourse. Onone hand, the position that nationalism can be distinctly religious does notcapture the nature of claims put forth by Muslim political actors such asHamas and their supporters. The Muslim Palestinians I worked with have notabandoned the idea of a national community nor have they focused theirefforts on the exclusive question of the state. On the other hand, the idea that‘Islamists’ have sacrificed the nation at the altar of the umma is not necessarilytrue. In the Palestinian context, there remains a central role for the Palestiniannation: its struggle for the liberation and reunification in the homeland. Myargument thus rests on an intermediary position grounded in the notion ofintertwining. I suggest this approach offers a more productive analysis that canaccount for the ways religion is brought into nationalist discourse withoutnecessarily undermining nationalism. Given the continued rise of religiouspolitical actors working within the structures of the nation-state, such ananalysis is critical as it points to the necessity of seeing the subtle and oftentense interactions between religious ideals and nationalist visions.

The second contribution this article makes concerns the significance of‘nationalism from below’ (Hobsbawm 1991) or ‘folk’ nationalism (Smith2000). My analysis has focused on a displaced community of Palestinians whoremain marginal both within the local–national context of Jordan and to thePalestinian center in the OPT. In their articulations of the homeland and itsstruggle, it is clear that this community has embraced the discourse of Hamas.However, this does not mean that refugees are passive recipients of the politicsof the Palestinian national ‘center’. Instead, the appropriation of Hamas’sdiscourse should also be seen within the specific context of displacement inwhich Palestinian refugees lived. The appeal of this discourse cannot bedivorced from the growing marginalization of refugees from the Palestinianpolitical process in general and the larger conflict with Israel in particular.

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 817

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

In this sense, my analysis offers an opening for examining how local‘diasporic’ communities engage homeland politics from afar. The ongoingdeterritorialization of peoples and simultaneous weakening and strengtheningof borders (Appadurai 1996) suggests a need for understanding how move-ment and confinement shape visions of community. Attending to the localconstruction of nationhood in Jordan affords us a perspective on nationalismthat highlights its continued relevance for populations (paradoxically)excluded by its logic. It allows us to see how nationhood remains hegemonicfor peoples struggling with its political, economic and geographicconsequences.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Wenner-Grenn Foundation and Fulbright IIE Fel-lowship for generously funding the research for this article. I also want tothank Drs. Sahera Bleibleh and Cabeiri Robinson, in addition to the anony-mous reviewers of this publication, for their helpful comments on the draft ofthis article.

Notes

1 Hamas won 76 out of 132 parliamentary seats.2 My research was generously funded by a Wenner-Gren dissertation research grant and a

Fulbright IIE.3 By ‘diaspora’, I am relying on Tölölyan’s idea of ‘diasporicity’, which manifests itself in

relations of difference wherein a community sees itself as linked to, but different from, thoseamong who it has settled and sees itself as linked to the people in the ‘homeland’ (Tölölyan 2007).

4 This research is based on two years of ethnographic fieldwork in UNRWA refugee camps inAmman, Jordan. The research period began in January 2006 and concluded in December 2007.During my time in Amman, I conducted over 100 formal and informal interviews with registeredPalestinian refugees of multiple generations in the camps of Amman, Jarash and Irbid. In addi-tion, I observed several functions within the camps that emphasized aspects of Palestinian identityand nationalism including weddings, summer camp activities with refugee youth, orphan centeractivities and camp meetings between activists.

5 One could increase the number to 78 by including four Hamas supporters that ran as inde-pendents (Shiqaqi 2006).

6 According to Zweiri (2006), Palestinian President Mahmood Abbas ignored warnings by theprime minister Ahmed Qurei that divisions among Fatah candidates could compromise theelections.

7 Emphasis mine.8 For Hamas’s political structure, see Milton-Edwards and Farrell (2010); Tamimi (2011); Roy

(2011); Gunning (2010); and Mishal and Sela (2006).9 This is not to suggest that Hamas is disinterested in regional political actors. Its external

leadership is fully engaged with states throughout the region and thus employs multiple rhetoricalapproaches that speak both to the Palestinian ‘inside’ and regional ‘outside’ (Hroub 2010; Mishaland Sela 2006).10 In addition to Hamas, one could add Islamic Jihad and, more recently, ‘salfist’ organizations.However, none have been as institutionally successful as Hamas.

818 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

11 The status of martyrs has been thoroughly discussed in several works including (Abufarha2009; Allen 2006; Khalili 2009).12 In Arabic, the word da’wa means to call, appeal, request or summons.13 The CD referred to Al-Ittijaha Al-Islamiı, Jam’iat Al-Zarqa’ Al-Ahlıya (The Islamic Positionof the Civil University of Zarqa’).14 Thikr, in this context, refers to particular words and/or phrases meant for promoting the‘remembrance of God’ through religious invocations.15 Anashıd is commonly used to refer to songs that do not include particular instruments andthus do not violate what some Muslims believe is a prohibition on music.16 Hamas fighters are known for their black hoods and green bandanas bearing the Muslimtestament of faith, ‘there is no God but God and Muhammad is God’s messenger’.17 For a detailed exposition of Hamas’s official and practical position on Christian Palestinians,see Hroub, 2000 (especially chapter 3, p. 139).

References

Abu Amr, Z. 1993. ‘Hamas: a historical and political background’, Journal of Palestine Studies 22,4: 5–19.

Abu-Amr, Z. 1994. Islamic Fundamentalism in the West Bank and Gaza: Muslim Brotherhood andIslamic Jihad. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Abufarha, N. 2009. The Making of a Human Bomb: An Ethnography of Palestinian Resistance.Durham: Duke University Press.

Aburaiya, I. 2009. ‘Islamism, nationalism, and Western modernity: the case of Iran and Palestine’,International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 22, 1: 57–68.

Allen, L. 2006. ‘The Polyvalent politics of martyr commemorations in the Palestinian Intifada’,History and Memory 18, 2: 107–38.

Anderson, B. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism.2nd edn. London: Verso.

Anderson, B. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism.New York: Verso Books.

Appadurai, A. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press.

Baumgarten, H. 2005. ‘The three faces/phases of Palestinian nationalism, 1948–2005’, Journal ofPalestine Studies 34, 4: 25–48.

Billig, M. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage Publications.Brubaker, R. 2012. ‘Religion and nationalism: four approaches’, Nations and Nationalism 18, 1:

2–20.Chehab, Z. 2008. Inside Hamas: The Untold Story of the Militant Islamic Movement. New York:

Nation Books.Fox, J. and Miller-Idriss, C. 2008. ‘Everyday nationalism’, Ethnicities 8, 4: 536–63.Friedland, R. 2002. ‘Money, sex, and God: the erotic logic of religious nationalism’, Sociological

Theory 20, 3: 381–425.Gunning, J. 2010. Hamas in Politics: Democracy, Religion, and Violence. New York: Columbia

University Press.Hibbard, S. 2012. Religious Politics and Secular States: Egypt, India, and the United States.

Washington DC: Johns Hopkins University Press.Hobsbawm, E. 1991. Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2nd edn.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Hroub, K. 2000. Hamas: Political Thought and Practice. Washington DC: Institute for Palestine

Studies.Hroub, K. 2004. ‘Hamas After Shaykh Yasin and Rantisis’, Journal of Palestine Studies 33, 4:

21–38.

Religion and nationalism in the Palestinian diaspora 819

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

Hroub, K. 2006. ‘A ‘New Hamas’ through its new documents’, Journal of Palestine Studies 35, 4:6–27.

Hroub, K. 2010. Hamas: A Beginner’s Guide. New York: Pluto Press.Hroub, K. 2011. ‘Hamas: conflating national liberation and socio-political change’ in K. Hroub

(ed.), Political Islam: Context Versus Ideology. London: SAQI Press.Juergensmeyer, M. 1994. The New Cold War?: Religious Nationalism Confronts the Secular State.

Berkeley: University of California Press.Juergensmeyer, M. 2009. Global Rebellion: Religious Challenges to the Secular State, from Chris-

tian Militias to Al Qaeda. Berkeley: University of California Press.Khalidi, R. 1998. Palestinian Identity. New York: Columbia University Press.Khalili, L. 2009. Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine: The Politics of National Commemoration.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Lybarger, L. 2007. Identity and Religion in Palestine: The Struggle between Islamism and Secular-

ism in the Occupied Territories. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Maqdisi, M. 1993. ‘Charter of the Islamic resistance movement (Hamas) of Palestine’, Journal of

Palestine Studies 22, 4: 122–34.Menon, K. 2012. Everday Nationalism: Women of the Hindu Right in India. Philadelphia: Univer-

sity of Pennsylvania Press.Mihelj, S. 2007. ‘Faith in nation comes in different guises’: modernist visions of religious nation-

alism’, Nations and Nationalism 13, 2: 265–84.Milton-Edwards, B. 2007. ‘Hamas: Victory with Ballots and Bullets’, Global Change, Peace and

Security 19, 3: 301–316.Milton-Edwards, B. and Farrell, S. 2010. Hamas: The Islamic Resistance Movement. Cambridge:

Polity Press.Mishal, S. and Sela, A. 2006. The Palestinian Hamas: Vision, Violence, and Coexistence. New

York: Columbia University Press.Nusse, A. 1998. Muslim Palestine: The Ideology of Hamas. London: Routledge Press.Roy, S. 2011. Hamas and Civil Society in Gaza: Engaging the Islamist Social Sector. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.Shiqaqi, K. 2006. ‘Sweeping victory, uncertain mandate’, Journal of Democracy 17, 3: 116–30.Smith, A. 1999. ‘Ethnic Election and National Destiny: Some Religious Origins of Nationalist

Ideals’, Nations and Nationalism 5, 3: 331–355.Smith, A. 2000. ‘The “Sacred” Dimensions of Nationalism’, Millennium – Journal of International

Studies 29, 3: 791–814.Tamimi, A. 2011. Hamas: A History from Within. Ithica: Olive Branch Press.Tölölyan, K. 2007. ‘The contemporary discourse of diaspora studies’, Comparative Studies of

South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 27, 3: 647–55.Turner, M. 2006. ‘Building democracy in Palestine: liberal peace theory and the election of

Hamas’, Democratization 13, 5: 739–55.Usher, G. 2006. ‘The democratic resistance: Hamas, Fatah, and the Palestinian elections’, Journal

of Palestine Studies 35, 3: 20–6.van der Veer, P. 1994. Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India. Berkeley: University of

California Press.Zweiri, M. 2006. ‘The Hamas victory: shifting sands or major earthquake?’, Third World Quarterly

27, 4: 675–87.

820 Michael Vicente Pèrez

© The author(s) 2014. Nations and Nationalism © ASEN/John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2014

![Milliyetçilik Milliyetçiliğin Kurdudur: Arap ve Türk Milliyetçilikleri Örneği [Nationalism is the Worm of Nationalism: The Cases of Arabic and Turkish Nationalism]](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/6325391d7fd2bfd0cb0359ca/milliyetcilik-milliyetciligin-kurdudur-arap-ve-tuerk-milliyetcilikleri-oernegi.jpg)