"Belonging in the Academy: Building a 'Casa Away from Casa' for Latino/a Undergraduate Students

Transcript of "Belonging in the Academy: Building a 'Casa Away from Casa' for Latino/a Undergraduate Students

http://jhh.sagepub.com/Education

Journal of Hispanic Higher

http://jhh.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/11/25/1538192714556892The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1538192714556892

published online 25 November 2014Journal of Hispanic Higher EducationSandra M. Gonzales, Ethriam Cash Brammer and Shlomo Sawilowsky

Undergraduate StudentsBelonging in the Academy: Building a ''Casa Away From Casa'' for Latino/a

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:Journal of Hispanic Higher EducationAdditional services and information for

http://jhh.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://jhh.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://jhh.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/11/25/1538192714556892.refs.htmlCitations:

What is This?

- Nov 25, 2014OnlineFirst Version of Record >>

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 1 –17

© The Author(s) 2014Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1538192714556892

jhh.sagepub.com

Article

Belonging in the Academy: Building a “Casa Away From Casa” for Latino/a Undergraduate Students

Sandra M. Gonzales1, Ethriam Cash Brammer1, and Shlomo Sawilowsky1

AbstractThis action research study, supported by a quantitative data analysis, presents a counternarrative to the deficit discourse regarding Latino/a First Time in Any College (FTIAC) departure during the first year of college. It argues that an intentional learning community model, that is culturally and linguistically responsive to Latino/a student needs, can produce significant gains in first- to second-year retention rates and better predicts retention than either high school grade point average or standardized test scores.

Resumen Este estudio de investigación en acción, apoyado por análisis de información cuantitativa, presenta una narrativa contraria al discurso de déficit en cuanto al abandono durante el primer año de la Universidad del [estudiante] Latino/a Por Primera Vez Universitario/a (siglas en Ingles FTIAC). Además, argumenta que un modelo de aprendizaje comunitario internacional, que responde a las necesidades de estudiantes Latino/as culturales y linguísticas, puede producir ganancias significativas en taza de retención del primer y segundo año y predice mejor la retención que el puntaje promedio de preparatoria y el resultado de pruebas estandarizadas.

Keywordshigher education, Latino/a, qualitative, retention, resilience

1Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA

Corresponding Author:Sandra M. Gonzales, Assistant Professor, Bilingual/Bicultural Education, College of Education, Wayne State University, 285 Teacher Education Division, Detroit, MI 48202, USA. Email: [email protected]

556892 JHHXXX10.1177/1538192714556892Journal of Hispanic Higher EducationGonzales et al.research-article2014

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

2 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

Introduction: The Center, O Sea, “La Casa Away From Casa”

Formerly known as the Center for Chicano-Boricua Studies (CBS), the Wayne State University (WSU) Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (the Center) was founded in 1970 as an Affirmative Action program designed to increase college access and opportunity for Latino/a students, primarily from the Southwest region of Detroit, Michigan.

The Latino en Marcha (LEM) Leadership Training Program, the Center’s name during its first year of existence before being established as a research center at WSU, was created through a University and community partnership. The partnership, between WSU; New Detroit, Inc.; and Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development (LA SED), was, according to archived documents, created to provide access for one of the most underrepresented ethnic groups on campus at the time. Indeed, the Center’s stated mission “to transform the University, and ultimately soci-ety, by providing equitable access to a quality university education” is a testament to its historical commitment to increasing educational attainment for Latino/a students at WSU.

As one of the first Latino/a Studies programs in the Midwest, the Center is one of the early pioneers in providing academic support services for Latino/a students. Currently, there are very few research centers in the country that provide the kind of comprehensive, one-stop, wrap-around, bilingual/bicultural student services available through the Center, including student recruitment, admissions, financial aid, direct financial support, academic and personal advising, while having access to tenured Latino/a professors, who are actively engaged in scholarship.

In 2007, the Center began to integrate learning community models within its stu-dent success programming to address the persistent gap in retention rates between students participating in its program and other First Time in Any College (FTIAC) students matriculating at WSU. The Center saw significant improvement in first- to second-year retention rates beginning in 2008, after new learning community strate-gies were fully implemented.

Purpose of the Study

This study investigates changes in first- to second-year student retention, from 2004 to 2012, to determine whether participation in the Center’s new learning community model—the casa away from casa for its students—had a statistically significant impact on retention for the cohorts of students studied. Also, the comparative predictive val-ues of high school grade point averages (GPAs) and standardized ACT scores are examined for students participating in the learning community.

There is a need for more research with regard to how institutions of higher learning can shift to better support Latino/a student retention and success. One way to answer this call is by asking questions, such as: How have historically negative stereotypes and deficit thinking shaped institutional policies and perspectives about Latino/a

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 3

students and their academic success? How is our learning community model helping to mitigate such factors? And is the new learning community model statistically sig-nificant at improving first- to second-year student retention?

Methods and Theoretical Framework

This action research study, supported by an analysis of quantitative data, uses critical theories in education, and an autoethnographic lens, to narrate the evolution of the Center’s learning community which was implemented in the Fall semester of 2007. Student data were tracked through the Winter semester of 2013 to measure first- to second-year retention for students entering the CBS Scholars Program through the Fall 2012 cohort.

All three authors, collectively, shape the analysis and concluding thoughts and rec-ommendations. The first author weaves the story into a theoretical framework; the second author, a program insider, narrates the sections about the Center’s development during this period; and the third author provides a quantitative analysis of the Center’s FTIAC incoming GPA and standardized test scores. A regression analysis on student high school GPAs, test scores, and the year that the students enrolled in the learning community was conducted to determine possible predictive ability for these variables.

Sample

This study examines each of the Center’s freshman FTIAC cohorts from 2004 to 2012, a total of 320 students over the 9-year period. Pre-existing, de-identified retention, high school GPA, and standardized test score data from internally generated reports are used to compare cohorts prior to the learning community interventions (2004-2006) with those after the interventions (2008-2012) to determine impact for first- to second-year retention. The Fall 2007 FTIAC cohort is defined as the transitional cohort for this study, as the learning community intervention was being implemented during this academic year.

Only minimal demographic data were available for the study. Because the data were pulled from previously existing reports and surveys, the authors did not have the opportunity to consider demographic patterns with regard to age, gender, socio-eco-nomic background, multilingual characteristics, family background, and so on. However, the authors were able to note the percentage of students who self-identified as Hispanic for each year of analysis (Table 1). The authors were not able to distin-guish between the various Hispanic ethnicities or nations of origin.

It is recognized that this study is limited to a specific group of students having participated in a specific learning community on the WSU campus, and the findings of the study are not necessarily generalizable beyond this group. Nevertheless, it is important to report on the outcomes of this learning community, as it may prove a helpful contribution to the woeful lack of research on Latino/a learning communities.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

4 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

The Autoethnography of a Casa Builder

I remember when I arrived at the Center in early 2007. My task was to systematically review the Center’s recruitment and retention practices to see what enhancements could be made to more effectively bridge the growing Latino/a population in Southeastern Michigan to WSU.

In the same year as my appointment within the Center, WSU opened an internal grant competition, encouraging the establishment of learning communities as a way to improve retention and student success on campus. This provided the perfect opportu-nity for the Center to formulate specific student support interventions and measure their impact on students participating in its programs.

It was with this intent that the faculty and staff at the Center collectively embarked upon the difficult, but transformative work, of revamping their entire student recruit-ment and retention model while applying for the 2007-2008 WSU Learning Community Initiative grant competition. According to the original request for proposals distributed by the WSU (2007) Division of Academic Affairs, the vision for the WSU Learning Community Initiative was “to enhance our undergraduates’ experience by providing all interested students dynamic, focused communities in which students, staff, and faculty learn and grow together” (p. 1).

I recall how the Learning Community Initiative’s focus on “learn[ing] and grow[ing] together” resonated with our own desire to maintain a sense of familia within the Center where close, family-like, interpersonal relationships between faculty, staff, and students were emphasized. Indeed, Consoli and Llamas (2013) explained how institu-tions that embrace the concept of familismo can help reduce assimilationist pressures by recognizing how it can be “a significant source of inspiration during adversity, a contributor to academic motivation and self-esteem” (p. 618).

My Center colleagues and I, many having participated in similar college access programs as undergraduate students ourselves, had a deep understanding of the

Table 1. CBS Scholars Cohorts Percent Hispanic by Year (2004-2012).

Year % Hispanic n

2004 94.8 55/582005 89.2 34/372006 87.5 35/402007 92.3 36/392008 85.3 29/342009 90.6 29/322010 89.5 34/382011 77.5 31/402012 90.0 36/40

Source. CBS scholars retention report.Note. CBS = Chicano-Boricua Studies.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 5

cultural and linguistic strengths of our students that were often overlooked, or too often perceived negatively due to deficit thinking, by some university officials. Two of us came to the Midwest from the West Coast and two others from the East Coast; and, we each had our own stories to tell with regard to championing increased access and an expanded support for Latino/as at our own alma maters as well as part of our sub-sequent professional careers.

Through our own experiences, we found college admissions were often rooted in a deficit discourse which asserts that certain students “don’t belong” in higher educa-tion, due to lower levels of college readiness as demonstrated by low standardized test scores or a lack of curricular rigor in high school. Western educational institutions, from kindergarten to college, have historically applied a deficit model to account for Latino/a student attrition or departure, perpetuating a wide range of theories which focus on student deficiencies, rather than institutional responsibility, asserting that: students are culturally or linguistically deprived, ill prepared, lack the proper family values or support, refuse to assimilate and/or simply do not care about education (Donato, 1997; Nieto, 2010; Spring, 2012; Valdes, 1996; Valenzuela, 1999).

We felt that many educators today not only reference these same deficits, by mea-suring intellectual preparedness via GPAs and high stakes testing formularies, but they also blame “school failure on poor attendance, high transience, bilingualism and a culture that was unresponsive to school” as cited by Donato (1997, p. 19). Rather than critiquing the system of inequality inherent in schools, students are instead blamed for their own mis-education which then deflects responsibility from the institution and educational policy makers (Donato, 1997). The inherent inequality within the system is rendered invisible which allows disadvantages to become reproduced, validated, and perpetuated. These stereotypes follow the student as they move through the edu-cational pipeline reinforcing how their culture, their intellect, and their language are incompatible with school and incompatible with more rigorous and “higher” forms of education (Gándara & Contreras, 2009).

Consider how tracking systems, advising practices, disciplinary policies, school activities, and the curriculum can serve to reinforce a discourse of cultural incompat-ibility, a discourse often used to justify the exclusion of some and the privileging of others (Nieto, 2010). Such a discourse has inappropriately molded school policies and practices and has become a normalized part of educational spaces (Attinasi, 1989; Nieto, 2010; Torres, 2006).

Deficit theories about Latino/as permeate the K-12 school environment, and history has shown us that it permeates the post-secondary environment as well. Blossfeld and Shavit (via Cervantes, 2008, p. 13) wrote, “Cultural and social capital and social reproduction models are perpetuated by academic institutions through admissions and selectivity standards.”

Such discourse is significant, because it has shaped not only institutional policies and protocols, but also deeply embedded itself in the institutional psyche. We, at the Center, recognized that a failure to address and rectify this history in meaningful ways could have strong implications for the institution as well as the student. These legacies can serve as an institutional blind spot that negatively impacts the institution’s ability

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

6 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

to recruit and retain students. It may, in addition to other factors, also positively or negatively impact the student’s perception of university affability and thus their will-ingness to attend as well as their perceived probability of failure or success.

Minikel-Lacocque (2013) argued that university faculties and administrations need to move beyond the binary of student success or failure as measured by GPAs and col-lege graduation rates, because these indicators do not demonstrate the complexities of life for undergraduate students of color. What is more, these commonly used frame-works, as Tinto (1993) pointed out, rarely ask the university to take responsibility for its student success, nor do they shed light on “how institutions need to change to meet the needs of all students” (Minikel-Lacocque, 2013, p. 433).

In another study, Gándara and Contreras (2009) described how Latino/as are not only at a disadvantage with regard to entering high school GPAs and standardized test scores, but they also face significant disadvantages when considering other suppos-edly “race neutral” attributes during the college admissions process, such as extracur-ricular activities, enrollment in honors courses, playing a musical instrument, and participating in intramural sports, to which minoritized communities often have less access. Gándara and Contreras attributed this to the fact that many Latino/as attend under-resourced schools that might not have an honors curriculum or even music. In addition, “Latino students are often less able to participate in critically important extracurricular activities because of constraints on their time or resources, or a lack of information or a sense of belonging” (Gándara & Contreras, 2009, p. 248).

Nonetheless, measures of student engagement and student activities in high school are frequently used as an indicator of college persistence, by universities, when review-ing a student’s profile for admission (Gándara & Contreras, 2009). These types of admissions standards continue to privilege the social and cultural capital of the domi-nant culture while neglecting the cultural assets and strengths of Latino/as. This dem-onstrates how student development theories and models of engagement are sorely lacking in literature that reflect the needs of students by race and ethnicity (Teranishsi, Behringer, Grey, & Parker, 2009).

Feeling out of place, not belonging, feeling judged, and pressures to assimilate are often cited in the literature as explanations for the lack of Latino/a student success, retention, and graduation (Cervantes, 2008; Consoli & Llamas, 2013; Donato, 1997; Gándara & Contreras, 2009; Minikel-Lacocque, 2013; Yosso, Smith, Ceja, & Solórzano, 2009). Tinto (1993) explained that, although student departure has been a well-studied phenomenon, “researchers have failed to distinguish between involuntary departure resulting from academic dismissal and voluntary departures occurring despite the maintenance of adequate grades” (p. 35).

In the case of the Center, we began to wonder what we could do within our learning community to prevent the voluntary departure of our students resulting from institu-tional factors such as those mentioned above. We noticed that very few of our students were involuntary departures resulting from poor academic performance, despite the perception of colleagues within our institution to the contrary. It was this analysis that brought us together to more closely examine the lineage of deficit discourses in the academy.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 7

Indeed, it is the internalization of these negative stereotypes, labels, and criticisms by underrepresented, low-income, and first-generation students—and faculty mem-bers acting upon these same negative stereotypes in their classrooms—that often serve as the key obstacles to student success (Gándara & Contreras, 2009; Minikel-Lacocque, 2013; Scribner & Reyes, 1999). Resisting the temptation to blame the victim for the social inequities leading to generally lower levels of college preparation, the Center determined to implement strategies that would change institutional attitudes about the Center’s programs without significantly changing the composition of the student body itself.

Strengthening the Center’s Role as a “Casa Away From Casa”

Prior to 2007, the program was thought of as a 1-year “access” intervention. There was no coherent or structured path for students to enroll in the various ethnic studies courses taught by the Center’s faculty and affiliates. Many students took only CBS courses, foregoing math, English, and other general education requirements altogether. In these cases, students would often perform well while working closely with Center faculty, when the “interactions with faculty and peers” were high (Kuh, O’Donnell, & Reed, 2013, p. 11), but suffered as soon as they were outside of that support structure. Upon that realization, we began to consider ways the Center could extend this continu-ity of care beyond the first year, to college graduation, and truly build a casa away from casa.

Part of the solution was to redesign the curriculum so that students would receive a focused education on student success strategies along with an introduction to ethnic studies in CBS 1410, the Center’s Student Success Seminar, during their first year. They would also be required to take English and math upfront, two of the most critical hurdles for students to overcome to graduate. They would accomplish these tasks by enrolling in these gateway courses as a cohort to “encourage [greater] contact between students and faculty” (Chickering & Gamson, 1987, p. 1). It was our belief that cohort-ing our students would facilitate stronger support networks among them and strengthen the link between students, faculty, and staff, thus strengthening the Center’s role as a home away from home, or a casa away from casa.

The Center also aligned itself with “high impact practices,” which recommend “significant investment of time and effort by students over an extended period of time” as well as “performance expectations set at appropriately high levels” (Kuh, O’Donnell, & Reed, 2013, p. 13) echoing Chickering and Gamson (1987), who said to “commu-nicate high expectations” (p. 1). As a result, after 2007, the Center began to emphasize increased expectations and academic rigor in every phase of its programs, increasing the credit hours—and course work—assigned to its first-year transition workshop, CBS 1410, the Student Success Workshop.

Early coursework in math and English are also important to the success of Latino/as. Indeed, students who succeed in these gateway courses are more likely to graduate

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

8 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

according to Musoba and Krichevskiy (2014). Thus, beginning the fall semester of 2008, using block schedules, students were routed into the same math sections sponsored by the Center for Excellence and Equity in Mathematics (CEEM), which requires students to complete an additional workshop section leading to increased credit hours, above the Math Departments’ regular WSU offerings (i.e., 7 credit hours for the CEEM version of MAT 1050: Algebra with Trigonometry vs. only 5 for the standard MAT 1050 course).

Prior to 2008, many students participating in the program tended to delay their math courses and then they were unable to pass their math competency which either delayed or prevented them from graduating from the University. By placing them in the high-intensity math courses that had additional lab hours and learning community tutorial support, the pass rates for mathematics were significantly higher than the uni-versity’s FTIAC average in the same course. In 2008, only 44% of university FTIACs passed their Math 0993 course, while 78% of the CBS Scholars passed this same course. In 2009, the university pass rate was only 59% compared with 100% of CBS Scholars. The CBS scholars pass rates continued to outpace the university’s pass rate ever since. In addition, students who were previously fearful of the math requirement saw they could be successful; subsequently, many even sought out careers in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

A similar class cohorting strategy was implemented in 2007, in collaboration with the English Department, allowing students to enroll in the same course sections of ENG 1010: Basic Writing and ENG 1020: Introductory College Writing, maintaining cohort cohesion and support while building, what we hoped would be, a very strong sense of collectivity, community, and familia. We intentionally paired students with caring faculty who could scaffold culturally reflective content knowledge on top of critical and urban literacies. Our goal was to maximize engagement and reduce stig-matization thereby positively impacting retention and success (Torres, 2006). These practices are supported by Gabelnick, MacGregor, Matthews, and Smith (1990), who stated that a learning community is

any one of a variety of curricular structures that link together several existing courses—or actually restructure the material entirely—so that students have opportunities for deeper understanding and integration of the material they are learning, and more interaction with one another and their teachers as fellow participants in the learning enterprise. (p. 19)

Shapiro and Levine (1999) also cited Alexander Astin’s (1985) definition for comparison:

These can be used to build a sense of group identity, cohesiveness, and uniqueness; to encourage continuity and the integration of diverse curricular and co-curricular experiences; and to counteract the isolation that many students feel. (p. 161)

Hence, beginning in 2007, the first year of program was focused on facilitating a suc-cessful transition for students, through the establishment of a strong sense of community by cohorting and block scheduling (Tinto, 1998), while communicating high expectations and promoting a culturally reflective curriculum. Our hope was that by the second year of

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 9

the program, many students would possess the academic tools and survival skills they needed to be successful at WSU, and they would have the necessary background in read-ing, writing, mathematics, and critical thinking, or what Robbins, Lauver, Le, Davis, Langley, and Carlstrom (2004) referred to as “academic-related skills” (p. 269), the most powerful predictor of student retention, according to their study.

The 2007 cohort continued to receive academic support during their second year on campus, which began with the fall semester of 2008. This extended their programming an additional year beyond what was previously offered to students prior to 2007. During Year 2 of the learning community, students were allowed to choose from the various ethnic studies courses like CBS 2410: History of Mexico, CBS 2420: History of Puerto Rico and Cuba, or CBS 2110: Puerto Rican Literature and Culture. Additionally, as Tinto (1998) suggested, they took these courses with many of the same students that they had taken CBS 1410, MAT 0993, MAT 1050, ENG 1010, and ENG 1020 the previous year, thus extending the learning community that they had established as a cohort into the following year while increasing what Kuh, O’Donnell, and Reed (2013) called a “significant investment of time and effort over an extended period of time” (p. 10).

With a great deal of intentionality, the Center began to embrace the quality of its mission, without losing its traditional identity of providing access to those who might not otherwise be able to go on to higher education without the Center’s intervention. Still holding true to the pre-transition (2004-2006) commitment to provide special admissions to students who needed it, in 2007, the learning community transition year, the Center also began to emphasize rigorous standards and high expectations. During this time, the Center provided the highest levels of academic and personal support pos-sible, through low counselor-to-student ratios.

Another transition goal, in 2007, was for all incoming students to be mixed together in the same sections, none knowing who was Honors and who was a “special admit.” Many of the students, before and after the learning community intervention, came from the same neighborhoods, from the same high schools, and, indeed, many strug-gled with the same kinds of socio-economic realities. Regardless of their incoming GPA or test score, all students were to be given the same assignments, held to the same high standards and expectations, and, most importantly, they were all to be treated with the same level of caring, dignity, and respect.

Due to the success of the learning community intervention, the Center would no longer allow itself to be perceived as only a special admissions program, but it would provide an Honors College quality of education to all of its students, regardless of their entering high school GPA and/or ACT score. Interestingly, although many post-secondary Latino/a students are labeled “unprepared” and “at risk,” according to a mixed-methods study by Torres (2006), it was found that

the traditional predictors of retention such as previous academic performance or measures of academic achievement (Nora et al., 1997; Tinto, 1993) did not seem to be the most important factors influencing student success in this context. Instead, campus experiences emerged as being more important in helping these students stay in college. (p. 307)

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

10 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

In a subsequent quantitative analysis of the program’s first- to second-year reten-tion data, which we conducted to study the effectiveness of the new learning commu-nity interventions, we found that our results seem to concur with the work of scholars, such as Nora, Kraemer, and Itzen (1997); Tinto (1993); and Torres (2006).

In the 2007-2008 academic year, the Center received its first year of Learning Community funding and immediately saw modest gains in first-year retention, as the new peer mentoring and revamped curricular components were being implemented. However, it was in 2008 (with the fall 2008 cohort), after full implementation and some additional tinkering and refining, that the program saw its greatest gains in first-year retention: 85.3% (2010) versus a baseline range of 48.3% (2004) to 59.0% (2007). These gains were achieved essentially without statistically significant increases in stu-dent high school GPAs or ACT scores, as demonstrated in Table 2.

Data Collection

To determine whether the new learning community model was statistically significant at improving first- to second-year student retention, we collected three different data sets for this study. One set included data from nine different de-identified annual reten-tion reports for each of the cohort years of 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012. Each of these reports was previously generated by the Center for programmatic evaluation. Each report included the year students in that cohort entered the program, whether or not they were retained in their second year along with their high school GPA and ACT score. The same data were collected for the general univer-sity FTIAC population.

The second data set included fall semester first-year math and English pass rates for the Center’s cohorts in addition to the general university FTIAC population.

The third data set detailed the total number and percentage of self-identified Hispanics in the program, by cohort year. It also included the number of

Table 2. Average Retention, HS GPAs, and ACT Scores for CBS Scholars (2004-2008).

Year Retention (%) Average HS GPA Average ACT composite

2004 48.3 2.85 17.152005 56.8 2.86 16.812006 57.5 3.06 16.812007 59.0 2.86 18.082008 85.3 3.01 17.972009 81.3 3.11 18.252010 86.8 3.01 19.892011 77.5 2.99 19.052012 85.0 2.98 19.07

Note. HS GPAs = high school grade point averages; CBS = Chicano-Boricua Studies.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 11

non-Hispanics enrolled in the program. These data were purely informational, no fur-ther analysis was conducted.

Both the retention and the racial/ethnic data were stored in Excel spreadsheets. Only the retention data were imported into SPSS version 22. Frequencies were com-puted, along with the range for each input variable, which were then checked against the Excel file to ensure the data were imported accurately.

Research Design

We studied three retention groups: (a) pre-transition, which refers to those students who entered the program in 2004-2006, which was prior to the learning community intervention; (b) transition, which refers to those students who entered in 2007 while the learning community was being implemented; and (c) post-transition, which refers to students in 2008-2012 who participated in the established learning community.

Baseline equality was sought on the basis of ACT and high school GPA for the three groups. The design is

O OA GPA A GPA1 3 5 2 4 6, , : , , , : ,( , x,X)− − −

where O1, O3, and O5 are covariates for ACT and high school GPA scores; X is the learning community intervention; and O2, O4, and O6 represent the outcome variable of retention (see Table 3).

Research Hypotheses and Sample Size Determination

In the initial stage, the research question was whether the retention rates differed based on cohort group. It was determined that controlling for ACT and high school GPA would give a more precise answer to this research question. The sample size available for this analysis N = 320 (pre-transition n1 = 117, transition n2 = 29, post-transition n3 = 174). Assuming a medium effect size of 0.25, and minimum power of 0.80, a sample size of N = 158 (denominator df = 143) is required.

The main research question was whether ACT and high school GPA were predic-tors of retention. The sample size requirements do not differ from the initial stage, indicated above.

Table 3. Research Design.

Group Covariate Intervention Retention

1. Pre-transition O1A,G – O2R

2. Transition O3A,G x O4R

3. Post-transition O5A,G X O6R

Note. A = ACT, G = grade point average, R = Retention, x = Intervention in transition, X = Intervention.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

12 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

Results

Preliminary Analysis

The initial analysis for this design was a one-way ANCOVA, conducted on retention by cohort group (CBS Scholars), with ACT and high school GPA serving as covari-ates. Levene’s test of equality of error variances was statistically significant (F = 45.9, df = 2, 317, p = .000). However, an inspection of variances for the three groups (pre-transition, transition, and post-transition) indicated the level of heteroscedasticity was very mild (Group 1 variance = .25, Group 2 variance = .25, Group 3 variance = .14). Hartley’s test for equality of error variances was not significant (H = 1.78, p > .05), and therefore this underlying assumption of the ANCOVA is not of concern.

The analysis of effects following the tests for underlying assumptions is the ANCOVA on Group. The result was statistically significant (F = 12.93, df = 2, 315, p = .000), as indicated in Table 4. The R2 was .093 (adjusted R2 = .081).

Main Analysis

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to determine if ACT and high school GPA were predictors of retention. The obtained regression equation was

′ = +Y . . ,388 107HSGPA

where ′Y is the predicted score, .388 is a constant (or Y intercept), beta (a weighting value) is .107, and HS GPA is high school GPA. The R2 was .014, and the adjusted R2 was only .011, meaning that although the regression equation is statistically signifi-cant, high school GPA does not explain 98.9% of the variability in retention.

ACT was excluded from the regression equation, as the t test on its beta was 1.17, p = .243. Hence, ACT is not a predictor of retention. What predicted retention, however, was the year that a student entered the program, with post-transition cohort years

Table 4. Dependent Variable: Retention.

SourceType III sum of

squares df MS F Significance

Corrected model 6.15 4 1.54 8.04 .000Intercept 1.12 1 1.11 5.82 .016ACT 0.01 1 0.01 0.02 .878High school GPA 0.43 1 0.43 2.24 .136Group 4.95 2 2.47 12.93 .000Error 60.24 315 0.19 Total 226.0 320 Corrected total 66.39 319

Note. df = degrees of freedom, MS = Mean Square, GPA = grade point average.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 13

2008-2012 having the highest predictors for successful first- to second-year retention. This is strong evidence of the positive impact of the Center’s learning community model.

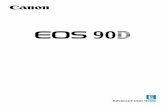

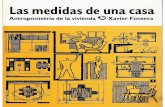

Moreover, after 4 years of program implementation, the Center’s learning commu-nity model was able to sustain much higher first- to second-year retention rates, with-out abandoning its commitment to access for students who, statistically, were among the least well prepared at WSU. In addition, it was discovered that the new academic success interventions had closed the educational achievement gap for CBS Scholars as measured by first- to second-year retention rates between both WSU FTIACs and WSU White FTIACs (Figures 1 and 2). Thus, with these findings, we concluded that the Center’s learning community model could help to mitigate negative stereotypes and deficit thinking about Latino/a student potential.

Discussion

In a massive qualitative interview (N = 227), Walpole et al. (2005) found many Latino/a students expressed the belief that standard college admission tests were not culturally fair and left little opportunity to perform well. In the current study, therefore, the focus was on retention instead of the ACT/SAT. Robbins et al.’s (2004) meta-analysis indi-cated the correlation of ACT/SAT scores and retention was only r = .121. Among the best psychosocial predictors were academic-related skills (r = .298), academic self-efficacy (r = .257), socio-economic status (SES; r = .212), and institutional commit-ment (r = .204). The results of our study support both a reconsideration of the predictor of success, from standardized tests to the CBS learning community, as well as the criterion for success, from GPA or graduation to the more immediate retention. Retention was the immediate concern over graduation rates, because dropout pre-cludes graduation.

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012CBS Scholars 48.3 56.8 57.5 59.0 85.3 81.3 86.8 77.5 85.0WSU FTIACs 71.7 69.2 68.8 69.7 76.1 77.1 76.7 74.8 74.8

0.010.020.030.040.050.060.070.080.090.0

100.0Pe

rcen

t Ret

aine

d

Figure 1. CBS Scholars versus all WSU FTIACs.Note. CBS = Chicano-Boricua studies; WSU = Wayne State University; FTIACs = First Time in Any Colleges.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

14 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

Our study was consistent with a variety of previous studies. Lopez’s (2005) survey of N = 54 of Latino/a freshman and Niemann, Romero, and Arbona’s (2000) survey (N = 536) which indicated socio-cultural interactions, behaviors, and peer support while at college are major contributing factors to success when transitioning into cul-turally different universities. Another study that supports the significance of Latino/a learning communities was a small study conducted by Zalaquett (2005). Based on a small sample (N = 12) at a larger urban university, a qualitative narrative of Latino/a students’ stories indicated the positive impact of friendship and community support and responsibility were important for success at college. Zalaquett also recommended the creation of Latino/a clubs and creating collaborative and mentoring linkages with teachers as factors increasing academic success. A later study by Nora (2003) demon-strated that habitus (“whether they see themselves fitting in,” p. 263; Arbona & Nora, 2007) plays a major role in college success.

These previous studies, combined with our current study, demonstrate the signifi-cance of culturally relevant learning communities. To illustrate, the Center was able to achieve better outcomes with students who might be labeled “unprepared” and “at risk,” by creating “a casa away from casa” where students could be mentored by Latino/a faculty who utilized a culturally reflective curriculum, while communicating high expectations (Chickering & Gamson, 1987) and employing high-impact practices (Kuh, O’Donnell, & Reed, 2013) as part of an intentional Latino/a-centered learning community model (Shapiro & Levine, 1999).

Importantly, we were able to demonstrate that students continued to progress toward graduation, not because of higher incoming GPAs or standardized test scores but because they were able to build lasting bonds with fellow students and faculty. A sense of collectivity, belonging, and familia was created that now carry these students well beyond their first year at WSU.

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012CBS Scholars 48.3 56.8 57.5 59.0 85.3 81.3 86.8 77.5 85.0WSU White FTIACs 77.6 74.9 75.0 76.5 79.0 79.5 78.4 80.5 79.0

0.010.020.030.040.050.060.070.080.090.0

100.0Pe

rcen

t Ret

aine

d

Figure 2. CBS Scholars versus WSU White FTIACs.Note. CBS = Chicano-Boricua studies; WSU = Wayne State University; FTIACs = First Time in Any Colleges.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 15

As a result of improved student learning outcomes and increased retention, in 2011, the Center was named a national finalist in the baccalaureate division of the “Examples in Excelencia! Awards” given by Excelencia! in Education, an organization dedicated to helping close the Latino/a educational achievement gap. The Center’s model has also been studied and replicated at a number of different institutions in Michigan hop-ing to better serve the Latino/a population.

As the Latino/a community continues to grow in the Unites States, and the edu-cational achievement gap between Latino/as and other ethnic groups in the country continues to persist, it is critical that more research be done to better understand the institutionalized obstacles impeding Latino/a degree attainment (Fry & Lopez, 2012), as well as discovering data-driven solutions for overcoming these challenges. To that end, the authors intend on continuing the research begun with this prelimi-nary study.

In a possible follow-up study, the authors hope to replicate aspects of the meta-analysis conducted in 2004 by Robbins et al. to understand the effects on Latino/a student success of other variables not examined in this current study. These variables include gender, SES, high school rigor, summer bridge participation, Latino/a Studies coursework as well as an analysis of first-year gateway courses such as English and math with the hopes of demonstrating that there are more culturally responsive alter-natives to standardized test scores that might better predict Latino/a student retention and success.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article acknowledge the support of the faculty, staff, and students at the Wayne State University (WSU) Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies. In particular, the authors thank Dr. Jorge L. Chinea, the Center’s director, without whose support this research project would not have been possible. Mil gracias a todos!

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: One of the contributors is employed by the center where the data were collected.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Arbona, C., & Nora, A. (2007). The influence of academic and environmental factors on Hispanic college degree attainment. The Review of Higher Education, 30, 247-269.

Astin, A. W. (1985). Achieving educational excellence. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.Attinasi, L. C. (1989). Getting in: Mexican Americans’ perceptions of university attendance

and the implications for freshman year persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 60, 247-277.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

16 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

Cervantes, C. C. (2008). The impact of learning communities on the retention and academic integration of Latino students at a highly selective private four-year institution (Doctoral dissertation). University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. (1987). The seven principles for good practice in undergradu-ate education. AAHE bulletin, 3, 7.

Consoli, M. L., & Llamas, J. D. (2013). The relationship between Mexican American cultural values and resilience among Mexican American college students: A mixed methods study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 617-624. doi:10.1037/a0033998

Donato, R. (1997). The other struggle for equal schools: Mexican-Americans during the Civil Rights era. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Fry, R., & Lopez, M. H. (2012). Hispanic student enrollments reach new highs in 2011. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center.

Gabelnick, F., MacGregor, J., Matthews, R. S., & Smith, B. L. (1990). Learning communi-ties: Creating connections among students, faculty, and disciplines (New Directions for Teaching and Learning, No. 41). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Gándara, P., & Contreras, F. (2009). The Latino education crisis: The consequences of failed social policies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kuh, G. D., O’Donnell, K., & Reed, S. (2013). Ensuring quality & taking high-impact practices to scale. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Lopez, J. D. (2005). Race-related stress and sociocultural orientation among Latino students during their transition into a predominately White, highly selective institution. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 4(4), 354-365.

Minikel-Lacocque, J. (2013). Racism, college and the power of words: Racial micro-aggressions reconsidered. American Educational Research Journal, 50, 432-465. doi:10.3102/0002831212468048

Musoba, G. D., & Krichevskiy, D. (2014). Early coursework and college experience predictors of persistence at a Hispanic serving institution. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 13, 48-62. doi:10.1177/1538192713513463

Niemann, Y. F., Romero, A., & Arbona, C. (2000). Effects of cultural orientation on the percep-tion of conflict between relationship and education goals for Mexican American college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 22, 46-63.

Nieto, S. (2010). The light in their eyes: Creating multicultural learning communities. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Nora, A. (2003). Access to higher education for Hispanic students: Real or illusory? In J. Castellanos & L. Jones (Eds.), The majority in the minority: Expanding representation of Latino/a faculty, administration and students in higher education (pp. 47–67). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Nora, A., Kraemer, B., & Itzen, R. (1997). Persistence among non-traditional Hispanic col-lege students: A casual case model. Presented at the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Albuquerque, NM. (ED 415 824).

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psycho-logical and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 261-288. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261

Scribner, J. D., & Reyes, P. (1999). Creating learning communities for high-performing Hispanic students: A conceptual framework. In P. Reyes, J. D. Scribner, & A. P. Scribner (Eds.), Lessons from high-performing Hispanic high schools: Creating learning communi-ties (pp. 188-210). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Gonzales et al. 17

Shapiro, N. S., & Levine, J. H. (1999). Creating learning communities: A practical guide to winning support, organizing for change, and implementing programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Spring, J. H. (2012). Deculturalization and the struggle for equality: A brief history of the edu-cation of dominated cultures in the United States. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Teranishsi, R. T., Behringer, L. B., Grey, E. A., & Parker, T. L. (2009). Critical race theory and research on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in higher education. New Directions for Institutional Research, 142, 57-68. doi:10.1002/ir.296

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (1998). Colleges as communities taking research on student persistence seriously. The Review of Higher Education, 21, 161-177.

Torres, V. (2006). A mixed-method study testing data-model fit of a retention model for Latino/a students at urban universities. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 299-318.

Valdes, G. (1996). Con respeto: Bridging the distances between culturally diverse families and schools: An ethnographic portrait. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S. Mexican youth and the politics of caring. New York: State University of New York Press.

Walpole, M., McDonough, P. M., Bauer, C. J., Gibson, C., Kanyi, K., & Toliver, R. (2005). This test is unfair: Urban African American and Latino high school students’ perceptions of standardized college admission tests. Urban Education, 40, 321-349.

Wayne State University. (2007). 2007-2008 WSU learning community initiative call for propos-als. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Office of Academic Affairs.

Yosso, T. J., Smith, W. A., Ceja, M., & Solórzano, D. G. (2009). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate for Latino/a undergraduates. Harvard Educational Review, 79, 659-690.

Zalaquett, C. P. (2005). Study of successful Latina/o students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 5, 35-47.

Author Biographies

Sandra M. Gonzales is an Assistant Professor of Bilingual/Bicultural Education at Wayne State University. She received her doctorate in International Educational Development from Columbia University, Teachers College.

Ethriam Cash Brammer holds a doctorate in English from Wayne State University, where he currently serves as the Associate Director of the Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies.

Shlomo Sawilowsky is Professor and Wayne State University Distinuished Faculy Fellow in Educational Evaluation and Resarch in the College of Education. He is the editor of the Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, and the author of Real Data Analysis (2007) published by the American Educational Research Association SIG/Educational Statisticians.

by guest on November 26, 2014jhh.sagepub.comDownloaded from

![[Salis M.] Casa aragonese](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/632402435f71497ea9049a67/salis-m-casa-aragonese.jpg)