WILD TUNGUS AND THE SPIRITS OF PLACES Wild peoples of the Far North

Ballian et al. wild cherry 2012

Transcript of Ballian et al. wild cherry 2012

Population differentiation in the wild cherry

(Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Abstract

Background and Purpose: The wild cherry (Prunus avium) has greatand multiple importance. The fruits it produces are used for severalpurposes (as food for people, birds and other animals, as well as inphytotherapy). As many birds and mammals feed on the fruit of the wildcherry, it has the ability of dispersion over large areas in a very short time.It is present in from river deposits up to 1900 m/alt, while it is quite rare inthe Submediterranean. Wild cherry grows as a solitary tree or in smallgroups, usually at the edge of the forest or within the forest in areas withmore sunlight. The significance of the wild cherry is reflected in the higheconomic value of its wood, which makes it much demanded and popular,and thus endangered.

Materials and Methods: The plant material was collected from 22natural populations in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The fruit and leaves werecollected from marginal or solitary trees, usually from the south-facing,outer sun-exposed parts of the tree crown. We measured the following fruitcharacteristics: fruit length (FL), fruit width (FW), fruit thickness (FT),seed length (SL), seed width (SW), seed thickness (ST), length of the stalk(LOS) and width of the stalk (WOS), and leaf characteristics: length of thepetiole (LP), length of the leaf blade (LB), distance from the blade base tothe blade’s widest part (BBW), width of the leaf blade (WB), insertionangle of the leaf venation (AV), number of leaf teeth on a 2-cm length(NT), blade width at 1 cm from the blade apex (WBA) and blade width at 1cm from the blade’s base (WBB). All statistical analyses of the data weremade using the SPSS 15.0 package for Windows.

Results: The results obtained show the presence of a high level ofintrapopulational, as well as interpopulational, morphological variabilityin the natural populations of the wild cherry which have been investigated.Analyses of population differentiation have not confirmed our expectations.Our results only indicate differentiation in fruit size characteristics, but theindicators are very weak. The resulting high values of the regression coeffi-cient in this research can serve to estimate the values of some features andcharacteristics without their measurement.

Conclusions: The analyses of 16 morphological characteristics in 22natural populations of the wild cherry in Bosnia and Herzegovina showedstatistically significant differences between investigated populations. Diffe-rentiation in natural populations of the wild cherry was very low andidentified only in fruit dimension characteristics.

DALIBOR BALLIAN1

FARUK BOGUNI]1

AZRA ^ABARAVDI]1

SA[A PEKE^2

JOZO FRANJI]3

1University of SarajevoFaculty of ForestryZagreba~ka 20, 71000 SarajevoBosnia and Herzegovina

2Institute of Lowland Forestryand EnvironmentAntona ^ehova 1321000 Novi Sad, Serbia

3University of ZagrebFaculty of ForestrySveto{imunska 2510000 Zagreb, Croatia

Correspondence:Jozo Franji}University of ZagrebFaculty of ForestrySveto{imunska 25, 10000 Zagreb, CroatiaE-mail: [email protected]

Key words: wild cherry, Prunus avium,morphology, differentiation, variability

Received April 12, 2012.

PERIODICUM BIOLOGORUM UDC 57:61VOL. 114, No 1, 43–54, 2012 CODEN PDBIAD

ISSN 0031-5362

Original scientific paper

INTRODUCTION

The wild cherry (Prunus avium) has great and multi-ple importance. The fruit of the wild cherry is used

for several purposes (as food for people, birds and otheranimals, as well as in phytotherapy). As many birds andmammals feed on the fruit of the wild cherry, it has theability of dispersion over large areas in a very short time.The wild cherry grows on nutrient-rich soils of neutralreaction which are moderately moist, but is also oftenfound on sun-baked and dry habitats. It is found indeposits up to 1900 m/alt (1, 2, 3, 4), while it is quite rarein the Sub-Mediterranean. It is a fast-growing specieswith a production period of 40–60 years (5). It grows as asolitary tree or in small groups, usually at the edge of theforest or within the forest in areas with more sunlight.The significance of the wild cherry is reflected in thehigh economic value of its wood, which makes it muchdemanded and popular, and thus endangered. Literaturedata about the morphological variability of the wild che-rry are scarce and only general information for particularcharacteristics can be found, usually for seed and less forflower characteristics (6, 7), as well as some data aboutfruit size which serve for the taxonomic determination ofthe wild cherry (8).

The long-standing growth of local populations in dif-ferent ecological conditions has resulted in a high num-ber of ecotypes and forms of the wild cherry. For example,five ecotypes were defined based on morphology (9), twoforms according to fruit color (10), four forms accordingto several other morphological characteristics of leaves(11), and three forms of the wild cherry (12).

It is considered that the natural wild cherry popula-tions are distributed from West Asia to North Africa and

North Europe (4). There are several different pieces ofinformation available about the origin of the wild cherry.It is generally assumed that it originated in west Asia andCaucasus (13), while others believe its origin is in theMediterranean (14). However, some authors (15) statethat the wild cherry originated in Asia Minor, as well asSouth and Mid Europe, whereas others point out thePontic area (the east coast of Asia Minor) (16). Never-theless, existing archeological and fossil evidence suggestNorth-West Europe as the homeland of the wild cherry.

The aim of our research was to identify the level ofecological and genetic differences between the investi-gated natural wild cherry populations in Bosnia andHerzegovina, based on the application of comparativestatistical analysis on fruit, leaves, seeds and fruit stalkcharacteristics.

With this research, we wanted to evaluate the level ofvariability of several morphological characteristics by usingdescriptive statistics of parameters, variance analysis, ca-nonical and regression analysis. Efficient conservationmeasures and programmes, as well as conservation acti-vities using ex situ and in situ methods depend on theknowledge about the differentiation level of wild cherrypopulations.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The plant material was collected from 22 natural wildcherry populations in Bosnia and Herzegovina fromthree main phytogeographical provinces (Table 1, Figure1). We used the same sampling methodology as with theQuercus robur samples (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). Weused only leaves from short shoots because their cha-

44 Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012.

D. Ballian Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina

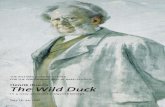

Figure 1. Studied population:1 @ep~e, 2 Olovo, 3 Majevica, 4 Posu{je, 5 Sarajevo, 6 Rogatica, 7 Livno, 8 Kalinovik, 9 Vi{egrad, 10 Drvar, 11Kongora, 12 Sanski Most, 13 Kupres, 14 Bosansko Grahovo, 15 Turbe, 16 Klju~, 17 Trnovo, 18 Sokolac, 19 Konjic, 20 Cazin, 21 Kakanj, 22Ustikolina.

racteristics reflect a recent condition of the species andare suitable for precise morphological research, as well asfor fruit research. The leaves were collected from mar-ginal or solitary trees, usually from the south-facing,outer sun-exposed parts of the tree crown, because onlysuch trees can entirely express its phenotype and geno-type (22, 23).

Following collection of the material, additional selec-tion was made and we removed all fruits and leaves thatwere not fully or properly developed, those that weredamaged or of irregular phenotype appearance. Apartfrom collection, it was necessary to herbarize all the leafmaterial to make it suitable for later measurements, so anadditional selection of the leaf material was done duringthe herbarization process.

We measured the following fruit characteristics: fruitlength (FL), fruit width (FW), fruit thickness (FT), seedlength (SL), seed width (SW), seed thickness (ST), len-gth of the stalk (LOS) and width of the stalk (WOS), andleaf characteristics: length of the petiole (LP), length ofthe leaf blade (LB), distance from the blade base to theblade’s widest part (BBW), width of the leaf blade (WB),insertion angle of the leaf venation (AV), number of leafteeth on a 2-cm length (NT), blade width at 1 cm from

the blade apex (WBA) and blade width at 1 cm from theblade base (WBB).

All measurements were made with 0,1-mm precision.Overall, we analyzed 22 populations, 204 trees, 2926fruits, seeds and stalks and 3069–3087 leaves. Altogetherwe have statistically analyzed 55.720 measurement dataitems. All measurements were entered into an Excelspreadsheet and statistical analyses of the data were madeusing the SPSS 15.0 package for Windows. We perfor-med the following statistical analysis: descriptive stati-stics, variance analysis, regression analysis and canonicaldiscriminant analyses.

RESULTS

The results obtained show the presence of a high levelof intrapopulation, as well as interpopulation, morpho-logical variability in the natural populations of the wildcherry which were investigated (Table 2, 3a and 3b). Theanalyses of population differentiation did not confirmour expectations. Our results only suggest differentiationin fruit size characteristics, but the indicators are veryweak.

As we can observe in Tables 2, 3a and 3b, the obtainedmean value for fruit length (FL) is 11.76 mm (Kongora

Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012. 45

Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina D. Ballian

TABLE 1

General information about investigated populations.

Pop.number

Population name Longitude Latitude Altitude (m) Phytogeographic Provenance

1 @ep~e 44°26’ 09’’ 17°57’ 58’’ 609 Zavidovici – Teslic area (3.4)

2 Olovo 44°10’ 32’’ 18°33’ 06’’ 563 Ozren – Okruglica region (3.5.1)

3 Majevica 44°31’ 27’’ 18°51’ 43’’ 510 North-Bosnian area (1.1)

4 Posu{je 43°32’ 30’’ 17°27’’ 24’’ 1076 Sub-Mediterranean mountain area (4.3)

5 Sarajevo 43°50’ 09’’ 18°23’ 04’’ 560 Sarajevo – Zenica region (3.3.3)

6 Rogatica 43°49’ 26’’ 18°57’ 44’’ 685 Rogatica region (2.2.2)

7 Livno 43°46’ 40’’ 16°57’ 24’’ 805 Region without evergreen elements (4.3.1)

8 Kalinovik 43°30’ 07’’ 18°28’ 41’’ 1054 Igman – Zelengora region (3.6.1)

9 Vi{egrad 43°48’ 04’’ 19°18’ 46’’ 587 Vi{egrad region (2.2.1)

10 Drvar 44°22’ 16’’ 16°22’ 22’’ 499 Sub-Mediterranean mountain area (4.3)

11 Kongora 43°38’ 28’’ 17°21’ 42’’ 958 Sub-Mediterranean mountain area (4.3)

12 Sanski Most 44°46’ 19’’ 16°40’ 20’’ 155 North-west Bosnian area (1.1)

13 Kupres 43°59’ 56’’ 17°16’ 16’’ 1226 Glamo~ – Kupres region

14 Bosansko Grahovo 44°10’ 46’’ 16°21’ 38’’ 873 Sub-Mediterranean mountain area (4.3)

15 Turbe 44°12’ 28’’ 17°30’ 39’’ 778 Vranica region (3.3.2)

16 Klju~ 44°31’ 52’’ 16°46’ 43’’ 286 Kljuc – Petrovac region (3.2.1)

17 Trnovo 43°41’ 11’’ 18°20’ 41’’ 929 Igman – Zelengora region (3.6.1)

18 Sokolac 43°56’ 25’’ 18°46’ 37’’ 954 Romanija region (3.5.2)

19 Konjic 43°34’ 37’’ 18°00’ 44’’ 696 Sub-Mediterranean mountain area (4.3)

20 Cazin 44°56’ 44’’ 15°55’ 44’’ 379 The area of Cazinska Krajina (3.1.)

21 Kakanj 44°06’ 49’’ 18°04’ 57’’ 558 Sarajevo – Zenica region (3.3.3)

22 Ustikolina 43°36’ 10’’ 18°44’ 43’’ 820 Gorazde – Foca region (2.2.3)

= 9.61 mm, Drvar = 13.23 mm) with the highest varia-tion in the Drvar population (19.21 %) and minimumvariation in the Trnovo population (5.08 %). The meanvalue for fruit width (FW) is 12.13 mm (Kongora = 9.50mm, Sarajevo = 13.70 mm) with maximum variationobserved in the Drvar population (20.00 %), and mi-nimum variation in the Posu{je population (5.42 %). Forfruit thickness (FT) the characteristic mean value is 11.05mm (Kongora = 9.01 mm, Sarajevo = 12.63 mm) withmaximum and minimum variation in the Drvar (17.71%) and the Kongora (6.51 %) populations respectively.

The obtained mean value for seed length (SL) was8.11 mm (Kongora = 7.31 mm, Bosansko Grahovo =8.76 mm) and the highest variation was displayed withinthe Cazin population (11.39 %), while the minimum vari-ation was observed in the Kongora population (5.35 %).

The mean value for seed width (SW) is 7.03 mm(Kongora = 6.61 mm, Olovo = 7.37 mm), with maxi-mum variation in the Ustikolina (10.38 %) and mini-mum variation in the Kupres (4.29 %) population. Themean value for seed thickness (ST) is 5.48 mm (Konjic =4.86 mm, Drvar = 5.88 mm) with maximum and mini-mum variation in the Konjic (14.95 %) and the Posu{je(4.44 %) populations, respectively. The mean value forlength of the fruit stalk (LOS) is 37.28 mm (Sokolac =32.10, Olovo = 43.39 mm), with maximum variationobserved in the Bosansko Grahovo population (19.60 %)and minimum variation in the Drvar population (11.87%). The mean value for width of the fruit stalk (WOS) is0.60 mm (Kakanj = 0.56 mm, Turbe i Trnovo = 0.63mm) with maximum and minimum variation in theMajevica (13.53 %) and the Kongora (9.47 %) popula-tions, respectively.

Moreover, as presented in Tables 2 and 3b the meanvalues for investigated leaf characteristics were as fo-llows: the mean value for length of the leaf blade (LB)was 80.03 mm (Kongora = 72.69 mm, Sarajevo = 85.65mm) with maximum variation in the Kalinovik popu-lation (18.61 %) and minimum variation in the Majevicapopulation (6.63 %), the mean value for length of thepetiole (LP) was 29.51 mm (Kalinovik = 24.18 mm,Olovo = 33.15 mm) with maximum and minimum va-riation in the Sanski Most (19.19 %) and the Kongora(10.31 %) populations, respectively, the mean value fordistance from the blade base to the blade’s widest part(BBW) was 44.45 mm (Turbe = 39.62 mm, Sarajevo =49.18 mm) with maximum and minimum variation inthe Kalinovnik (21.77 %) and the Majevica (8.60 %)population, the mean value for width of the leaf blade(WB) was 42.94 mm (Kalinovik = 37.81 mm, Kakanj =49.95 mm) with maximum and minimum variation ob-served in the @ep~e (13.55 %) and the Rogatica (7.03 %)populations, respectively, the mean value for insertionangle of the leaf venation characteristic (AV) was 45.20°(Sanski Most = 48.68°, @ep~e = 42.37°) with maximumand minimum variation recorded in the Konjic (16.38 %)and the Majevica (9.79 %) population, the mean valuefor the number of teeth on a 2-cm leaf length (NT) was10.16 (Olovo i Sarajevo = 9.41, Kakanj = 11.44) with

46 Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012.

D. Ballian Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and HerzegovinaTA

BLE

2

Descrip

tive

sta

tistica

ld

ata

describ

ing

fruit,

seed

,fr

uit

sta

lka

nd

lea

f–

sum

ma

ry.

FR

UIT

SE

ED

FR

UIT

ST

AL

KL

EA

F

FL

(mm

)F

W(m

m)

FT

(mm

)S

L(m

m)

SW

(mm

)S

T(m

m)

LO

S(m

m)

WO

S(m

m)

LP

(mm

)L

B(m

m)

BB

W(m

m)

WB

(mm

)A

VN

TW

BA

(mm

)W

BB

(mm

)

N29

2629

2629

2629

2629

2629

2629

2529

2530

5730

8730

8730

8730

8730

8730

7930

69

Min

imum

7.83

8.18

7.48

6.05

5.01

2.32

20.2

40.

3810

.82

49.5

324

.22

15.4

026

.00

6.00

1.58

9.36

Max

imum

21.1

221

.88

18.6

211

.16

9.13

7.43

68.5

70.

8848

.54

112.

9066

.62

65.5

178

.00

16.0

032

.69

41.5

7

Mea

n11

.76

12.1

311

.05

8.11

7.03

5.48

37.2

80.

6029

.51

80.0

344

.45

42.9

445

.20

10.1

614

.79

22.2

4

Std.

Dev

iatio

n1.

471.

701.

430.

720.

550.

516.

720.

074.

969.

166.

675.

846.

441.

575.

064.

66

CV

(%)

12.5

313

.99

12.8

98.

947.

889.

3518

.01

11.7

916

.80

11.4

415

.01

10.9

414

.25

15.4

634

.21

20.9

5

Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012. 47

Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina D. BallianT

AB

LE

3a.

Descriptive

statisticaldatafor

investigatedpopulations

describingm

easuredfruit,seed

andfruitstalk

characteristics.

Po

pu

lation

nu

mb

erP

op

ulatio

nn

ame

FR

UIT

SE

ED

FR

UIT

ST

AL

K

FL

(mm

)F

W(m

m)

FT

(mm

)S

L(m

m)

SW

(mm

)S

T(m

m)

LO

S(m

m)

WO

S(m

m)

Mean

(mm

)C

V(%

)M

ean(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mean

(mm

)C

V(%

)M

ean(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mean

(mm

)C

V(%

)M

ean(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mean

(mm

)C

V(%

)M

ean(m

m)

CV

(%)

1@

ep~e11.86

8.1612.43

10.9811.55

10.188.15

6.727.19

8.255.55

13.2039.22

17.580.59

11.86

2O

lovo12.70

8.9712.91

11.2111.94

10.248.70

7.537.37

6.615.67

8.1943.39

13.860.62

11.86

3M

ajevica10.33

9.1210.66

13.289.86

12.817.89

6.176.73

8.435.38

9.5433.52

18.150.62

13.53

4P

osu{je11.04

5.4910.43

5.429.81

6.588.33

7.366.88

4.995.44

4.4438.92

16.270.57

12.47

5Sarajevo

12.9414.26

13.7013.86

12.6313.65

8.038.03

7.125.90

5.506.96

39.7713.93

0.6012.75

6R

ogatica11.54

9.5012.35

10.3411.34

10.127.89

7.477.29

6.735.57

7.0937.49

18.150.61

12.44

7L

ivno12.09

7.3411.25

6.7610.54

7.408.64

6.697.12

5.035.43

6.1442.61

12.860.60

9.87

8K

alinovik10.38

8.2210.45

10.149.63

10.007.89

8.046.93

9.835.33

13.2936.56

15.420.60

12.12

9V

isegrad10.41

7.0710.83

8.699.98

8.027.66

7.026.73

6.305.26

5.8936.02

14.840.57

13.51

10D

rvar13.23

19.2113.45

20.0012.27

17.718.63

9.397.37

5.985.88

6.9334.37

11.870.61

10.69

11K

ongora9.61

6.329.50

6.969.01

6.517.31

5.356.61

5.545.27

4.9841.10

13.630.57

9.47

12SanskiM

ost11.88

10.0912.83

12.3311.29

10.817.97

7.526.75

7.125.44

7.3742.25

16.460.58

10.34

13K

upres11.07

7.3311.17

7.9110.26

7.137.98

7.146.97

4.295.46

4.6536.34

12.510.57

11.79

14B

osanskoG

rahovo12.09

7.7011.93

10.5510.81

8.968.76

7.947.11

5.355.59

6.6740.83

19.600.61

10.46

15T

urbe12.99

12.3713.29

12.5211.84

11.068.70

10.207.38

7.615.79

7.4734.37

18.420.63

10.33

16K

lju~12.20

6.7312.63

9.1011.27

7.078.14

6.137.09

9.795.46

6.9932.53

17.000.60

10.68

17T

rnovo11.78

5.0812.52

7.7411.35

7.628.18

5.897.31

5.275.72

7.1738.72

14.780.63

12.42

18Sokolac

11.806.47

12.506.70

11.216.15

7.945.68

6.996.22

5.556.72

32.1013.03

0.6110.79

19K

onjic12.16

6.9312.44

8.1711.14

8.418.05

7.836.63

8.084.86

14.9533.04

13.220.61

9.69

20C

azin11.25

5.7712.26

7.6610.71

5.127.93

11.397.06

7.565.58

6.6136.21

17.470.60

10.58

21K

akanj11.31

10.0412.15

8.9310.91

7.857.68

8.176.68

6.225.17

6.8133.99

16.050.56

11.28

22U

stikolina12.47

6.8812.89

9.9911.87

9.948.00

6.227.09

10.385.54

11.3434.50

17.360.59

10.68

Average

11.7612.53

12.1313.99

11.0512.89

8.118.94

7.037.88

5.489.35

37.2818.01

0.6011.79

48 Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012.

D. Ballian Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and HerzegovinaTA

BLE

3b

Descrip

tive

sta

tistica

ld

ata

for

investig

ate

dp

op

ula

tio

ns

describ

ing

mea

sure

dle

afcha

racte

ristics.

Po

p.

nu

mb

erP

op

.n

ame

LE

AF

LP

(mm

)L

B(m

m)

BB

W(m

m)

WB

(mm

)A

VN

TW

BA

(mm

)W

BB

(mm

)

Mea

n(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mea

n(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mea

n(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mea

n(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mea

n(°

)C

V(%

)M

ean

CV

(%)

Mea

n(m

m)

CV

(%)

Mea

n(m

m)

CV

(%)

1@

ep~e

82.7

710

.76

29.8

618

.53

44.8

914

.90

47.0

313

.55

42.3

714

.26

9.77

16.1

513

.71

41.6

824

.16

18.3

3

2O

lovo

82.0

58.

5733

.15

12.5

046

.14

11.8

147

.10

8.98

46.7

115

.89

9.41

14.4

715

.74

30.9

524

.21

19.4

1

3M

ajev

ica

77.8

16.

6325

.72

12.9

142

.98

8.60

41.6

38.

0743

.89

9.79

10.4

29.

9113

.10

19.2

922

.12

14.5

1

4P

osu{

je84

.71

11.0

729

.93

17.0

646

.60

12.3

944

.39

9.51

45.2

311

.34

9.87

12.1

211

.07

34.5

322

.13

15.7

9

5Sa

raje

vo85

.65

9.52

33.8

216

.28

49.1

813

.05

44.1

38.

3344

.20

10.6

79.

4111

.75

14.3

033

.59

20.4

514

.66

6R

ogat

ica

76.9

18.

6627

.65

13.1

441

.50

13.4

544

.99

7.03

47.7

013

.18

9.99

11.7

215

.35

26.8

926

.10

19.4

4

7L

ivno

79.0

88.

6832

.66

12.4

745

.24

12.6

245

.56

7.80

44.2

111

.57

10.6

317

.01

15.3

029

.37

22.6

616

.04

8K

alin

ovik

73.9

918

.61

24.1

819

.12

40.1

121

.77

37.8

113

.45

44.7

010

.95

10.6

014

.70

15.0

830

.21

20.8

818

.92

9V

i{eg

rad

80.8

78.

0330

.83

15.4

146

.78

11.9

742

.86

10.6

444

.39

12.3

610

.10

12.7

615

.67

34.7

021

.91

19.6

1

10D

rvar

78.5

610

.02

29.7

113

.22

44.0

513

.32

39.1

79.

9943

.27

12.5

410

.60

12.6

013

.41

33.7

520

.30

14.9

8

11K

ongo

ra72

.69

8.22

28.4

510

.31

39.9

711

.91

46.8

411

.19

43.8

814

.83

9.68

10.1

820

.15

18.7

725

.03

17.0

1

12Sa

nski

Mos

t84

.05

13.2

730

.90

19.1

945

.75

16.4

545

.74

13.0

048

.68

14.0

210

.34

13.0

115

.83

27.2

324

.08

19.7

8

13K

upre

s80

.76

9.86

29.5

417

.49

47.5

011

.94

40.1

211

.44

42.5

215

.29

9.76

13.3

615

.02

31.0

517

.67

17.3

1

14B

osan

sko

Gra

hovo

83.9

58.

5930

.00

13.8

246

.81

11.6

039

.03

12.9

345

.27

15.0

89.

5913

.25

12.8

134

.00

19.9

422

.29

15T

urbe

75.2

611

.12

29.4

218

.51

39.6

214

.98

41.2

413

.35

48.5

514

.10

11.0

416

.75

16.6

526

.66

22.1

216

.42

16K

lju~

77.5

814

.22

28.1

516

.15

42.0

117

.89

37.9

012

.08

45.2

314

.31

11.2

616

.92

12.4

636

.16

20.8

220

.09

17T

rnov

o81

.73

12.7

128

.40

16.2

045

.77

14.1

342

.96

11.5

246

.09

14.1

89.

8017

.04

15.6

736

.70

21.5

417

.66

18So

kola

c76

.76

10.5

429

.36

15.5

241

.84

14.0

943

.07

11.8

846

.95

12.3

110

.11

15.4

717

.20

26.3

423

.47

20.5

2

19K

onjic

81.2

48.

7229

.83

11.8

546

.40

10.8

740

.29

13.5

443

.05

16.3

810

.13

14.0

810

.94

45.2

620

.15

19.8

2

20C

azin

8518

8.72

28.0

414

.53

46.6

212

.43

41.6

19.

5744

.98

13.6

89.

6512

.83

11.7

232

.46

22.1

818

.76

21K

akan

j83

.35

7.45

30.3

012

.24

45.8

511

.84

49.9

510

.26

45.1

015

.16

11.4

413

.21

14.7

425

.67

25.2

918

.14

22U

stik

olin

a77

.57

10.8

027

.03

12.5

942

.79

14.9

140

.73

12.6

546

.63

13.2

69.

8217

.70

15.3

137

.30

21.4

524

.28

Ave

rage

80.0

311

.44

29.5

116

.80

44.4

515

.01

42.9

410

.94

45.2

014

.25

10.1

615

.46

14.7

934

.21

22.2

420

.95

Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012. 49

Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina D. BallianTA

BLE

4

AN

OV

AF

valu

es.

Po

p.n

ame

FR

UIT

SE

ED

FR

UIT

ST

AL

KL

EA

F

FL

(mm

)F

W(m

m)

FT

(mm

)S

L(m

m)

SW

(mm

)S

T(m

m)

LO

S(m

m)

WO

S(m

m)

LP

(mm

)L

B(m

m)

BB

W(m

m)

WB

(mm

)A

VN

TW

BA

(mm

)W

BB

(mm

)

@ep~e

15.2327.65

20.1727.86

23.7177.19

23.6610.15

41.1754.65

22.6573.69

10.6617.93

37.1013.06

Olovo

37.0536.81

43.1814.16

16.2721.47

13.4710.34

9.4010.55

5.3220.53

15.898.19

23.537.13

Majevica

13.6128.72

25.2321.00

54.3383.20

60.0814.42

2.7725.34

0.5436.53

1.110.63

4.616.57

Posu{je

8.520.62

1.3637.66

1.342.56

3.619.95

4.088.78

15.149.99

22.490.00

0.349.66

Sarajevo120.35

97.6892.69

54.3518.50

33.949.60

16.8227.15

21.0516.27

18.048.19

4.2234.89

15.38

Rogatica

39.3829.19

23.3421.51

9.7512.09

17.967.14

12.458.62

9.185.10

4.843.76

9.458.08

Livno

26.9710.52

8.3427.07

13.3916.61

12.564.64

10.2217.85

9.568.27

5.8424.46

41.7113.38

Kalinovik

63.9675.66

77.6353.71

98.7580.55

17.1530.38

70.1226.95

65.4619.01

7.5414.53

18.7516.51

Vi{egrad

12.1331.97

19.6016.82

22.0224.54

32.9115.83

15.8031.65

11.7617.67

5.336.40

50.1612.97

Drvar

314.86287.12

259.40147.20

44.8647.24

8.3818.63

20.519.74

12.2215.84

9.576.95

18.869.86

Kongora

15.349.41

6.526.69

6.287.65

16.9112.11

10.194.89

8.9723.27

5.414.32

6.333.26

SanskiMost

50.3063.77

41.4544.98

38.2734.52

39.437.00

27.7048.20

21.2213.51

12.383.29

8.9318.71

Kupres

36.4330.40

30.7139.10

9.2712.51

6.888.32

13.5224.96

13.4210.12

14.168.05

13.4210.94

Bosansko

Grahovo

21.1820.16

18.4326.16

10.0924.97

14.146.50

10.8415.04

10.9344.93

6.696.68

36.0820.92

Turbe

102.7091.61

90.2566.76

67.3756.04

17.7011.24

21.1043.74

9.7525.60

4.0220.01

8.581.60

Klju~

28.2037.91

25.5030.89

44.0125.27

17.083.03

34.0121.38

25.9624.45

9.0020.44

32.3511.52

Trnovo

7.4023.64

33.6223.18

30.3733.32

17.9113.16

24.2316.63

10.7220.70

5.2418.09

18.108.98

Sokolac27.47

20.5124.62

20.7833.43

29.525.98

4.859.64

25.8911.88

15.104.02

13.486.25

10.88

Konjic

43.7135.80

62.1056.89

25.76115.56

10.426.87

5.875.85

7.3539.83

13.0218.67

26.2919.97

Cazin

16.6234.79

29.27170.87

101.6476.10

33.015.38

4.9011.74

8.086.49

7.354.68

4.9814.95

Kakanj

43.8825.25

22.0540.60

15.7429.60

26.625.47

2.086.04

1.223.60

6.485.75

1.432.63

Ustikolina

24.8151.89

45.4829.03

111.80119.84

31.596.57

25.9618.62

21.0453.24

10.4032.01

68.1324.08

BE

TW

EE

NP

OP

UL

AT

ION

S90.69

90.2689.85

53.1435.85

33.1048.42

13.0427.48

33.9828.24

71.2012.32

23.2627.32

35.75

INTRAPOPULATION

maximum variation in the Trnovo population (17.04 %)and minimum variation in the Majevica population(9.91 %), the mean value for characteristic blade width at1 cm from the blade apex (WBA) was 14.79 mm (Konjic= 10.94 mm, Kongora = 20.15 mm) with maximum and

minimum variation in the Konjic (45.26 %) and theKongora (18.77 %) population and, finally, the meanvalue for characteristic blade width at 1 cm from theblade’s base (WBB) was 22.24 mm (Grahovo = 19.94mm, Rogatica = 26.10 mm) with maximum and mi-

50 Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012.

D. Ballian Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Figure 2. Discriminant analysis of fruit. Figure 3. Discriminant analysis of seeds.

Figure 4. Discriminant analysis of fruit stalk. Figure 5. Discriminant analysis of seed.

TABLE 5

Regression analysis of fruit. seed. fruit stalk and leaf (linear regression parameters correlation coefficient and coefficient of determination).

Variable Dependent Independent Intercept b1 b2 R R²

FRUITFL

FW2.87 0.73 0.84 0.71

FT 1.57 0.78 0.93 0.87

SEED

SL

SW

3.90 0.60 0.46 0.21

ST 0.33 0.73 0.79 0.63

LOS 23.39 0.16 0.22 0.05

FRUIT STALK WOS LOS 0.628 –0.001 0.08 0.01

nimum variation observed in the Ustikolina (24.28 %)and the Majevica (14.41 %) populations, respectively.

For all measured characteristics, statistically highlysignificant interpopulation variability was obtained atthe 99% significance level, as well as for the tree-popu-lation interaction, as shown in Table 4 where linearregression parameters, the correlation coefficient and co-efficient of determination were used.

Statistical analysis at the individual level by the ANOVAF-test showed statistically significant differences for al-most all characteristics and in all populations (Table 4).Such results should have a significant influence on suc-ceeding analyses of population differentiation.

In canonical discriminant analysis, where we the grou-ped measured characteristics (fruit, seed, fruit stalk andleaf) of investigated populations from the central Dina-rides, no differentiated groups were obtained by use ofanalyzed morphological markers (Table 5 and Figure

2–5). Therefore, populations did not form groups ac-cording to the Ecological Vegetation Classes, altitudeabove sea level, soil type, aspect of a slope, etc. Only weakdifferentiation was noticeable for fruit characteristics whichcan be associated with altitude above sea level.

For specific characteristics, high regression values wereobtained by regression analysis, as, for example, for fruitthickness (FT) (R2 = 0.87) (Table 5), while other chara-cteristics displayed very low values, as in the case of fruitstalk characteristic relationship (R2 = 0.01). As an exam-ple of high regression value (R2 = 0.71), the relationbetween seed thickness and seed width is shown in Figure6. A similar three- dimensional regression model wasobtained by analysis of three different characteristics (len-gth of the leaf blade, blade width at 1 cm from the bladeapex and width of the leaf blade) where high regressionvalue was obtained but without significant influence onpopulation differentiation (shown in Figure 7). Regar-ding soil reaction (pH), wild cherry populations in acidsoil did not show any difference with respect to popu-lations in limestone soil.

DISCUSSION

Based on our results from this research, we can seethat the wild cherry represents a very specific species,characterized by high variability at the individual as wellas interpopulational level, with a lack of differentiationbetween populations. From available literature data aboutthe wild cherry, we were able to observe certain vari-ability at the morphological level (5, 6, 7, 8, 25, 26, 27, 28,29, 30, 31) and less variation at the molecular and geneticlevel (32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42), whichprovided a certain specificity to this species, that is thetopic of much research. In earlier studies of the wildcherry (7, 43) with smaller number of populations, negli-gible differences were recorded between populations. Thisis the reason why this research included a higher numberof populations from different habitats and investigated ahigher number of characteristics.

For some characteristics, we confirmed differences atthe individual and population level using an F-test, butwith very weak or, in most cases, absent population dif-ferentiation. Earlier studies, due to their small scope,could not explain the obtained weak interpopulationaldifferentiation of the wild cherry. Analyses of obtainedresults, along with those from other researchers, indicatethat phylogenetic youth of the species could be one of thereasons for such results. This is reflected in the late andrelatively fast colonization of these areas, although someresearchers based on the wild cherry fossil records, pointout that it was spread over Europe in the ancient past (15).

As the usage of particular morphological markers en-ables detection of differences within or between popula-tions, as demonstrated with results for Pedunculate Oak(17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24), we expected the sameresults in this research, but they were not confirmed.Possible causes for these differences, if we exclude naturalselection and anthropogenic effects, are developmental

Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012. 51

Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina D. Ballian

Figure 7. Regression model of overall length of the leaf blade(LIST_DU_PLO) in relation to blade width (LIST_OD-STOJANJE) at 1 cm from the blade apex and width of theleaf blade(LIST_SIR_PLOJ).

Figure 6. Regression model of relation between seed thickness(PLOD_DEB) and seed width (PLOD_SIR).

factors, that is, the process of adaptation to given ecolo-gical conditions in which the individual appears, as wellas very complex fertilization mechanism and fast geneflow among populations (40). From all investigated cha-racteristics, results imply that we can indicate very lowdifferentiation only in fruit dimension characteristics,which can be explained by specific ecological conditions.In this way, we can conditionally group populations withsmall, middle-size and large fruits but with a high riskand precaution because the values are too small to spe-culate about strong and clear differentiation betweenpopulations.

The reproduction system of the wild cherry is verycomplex and genetic analyses indicate that gametophyticself-incompatibility is controlled by the multi-allelic S--locus (S1, S2, S3,..., Sn) (15, 43). Some authors report sixS alleles (44), while others believe that they producecertain proteins in the pollen, which control the in-compatibility phenomenon by the enzymatic degrada-tion of the growth hormone in the pollen tube whenidentical male and female allele appear both in the pollengrain and the style (45). In addition, there are explana-tions for the gametophytic self-incompatibility mecha-nism provided by hereditary regulatory mechanism the-ory (46, 47). New data (4) obtained by the analysis ofamino-acids and DNA of the sweet cherry confirm thepresence of 12 S alleles, whereas 25–30 alleles controllingthe incompatibility were identified in the wild cherry.The self-incompatibility phenomena have to be takeninto account when analyzing intrapopulation and inter-population variation because the presence of S allelesdecreases differentiation, along with very fast gene flowby seed and pollen dispersal (entomophily and ornitho-chory).

From all investigated characteristics, results imply thatwe can indicate very low differentiation only in fruitdimension characteristics, which can be explained byspecific ecological conditions. In this way, we can con-ditionally group populations with small, middle-size andlarge fruits but with a high risk and precaution becausethe values are too small to speculate about strong andclear differentiation between populations.

For other analyzed characteristics (seed, fruit stalkand leaf characteristics) we did not find such or similarresults. When drawing conclusions based on the analysisof obtained results, we must not overlook the presence ofadjacent glacial refugia where the wild cherry probablysurvived the glacial period. One of these refugia is situ-ated in the South, in the area of Greece (48, 49), whileother secondary refugia, mentioned in the research ofEuropean oaks (50, 51), is situated in the vicinity ofmiddle Dalmatia and could have influenced the lowdifferentiation. Usually species close to their glacial re-fugia do not lose much of their genetic potential and aretherefore less differentiated, as opposed to species quitedistant from their refugia. However, in this research itwas not possible to answer in a satisfactory way whetherthis had any influence on the low differentiation of inve-stigated wild cherry populations.

Taking into account that the wild cherry grows inareas where morphological characteristics depend on cli-matic, edaphic and orographic factors which can havedirect influence on morphological characteristics andadaptation of the wild cherry, we expected the formationof matching ecotypes, which, however, could not be con-firmed by this research. Unlike in this study, severalresearchers working with other species successfully cor-related obtained statistical differences between investiga-ted characteristics with climatic conditions in investiga-ted areas (52, 53, 54).

To explain the weak differentiation, we can refer toseveral studies carried out at a molecular level (55, 56, 57, 58,59, 60), and dealing with gene flow analyses in tree specieswhere seed dispersal by birds was present. In the researchof Frangula alnus (61), it was pointed out that birds arethe crucial factor for fast gene flow, which also happens tobe the case with the wild cherry. According to the sameauthor, species migration is influenced by bird migrationroutes, as well as the movement routes of other animalsthat feed on fruits of this scrub species. As we have thesame situation with the wild cherry which serves as foodfor numerous birds and animals, this statement is verylogical. Nevertheless, we must not forget the complexreproduction system present in the wild cherry, regulatedby a series of multiple S-alleles mentioned by many re-searchers (4, 15, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47). The aforemen-tioned multiple alleles regulate incompatibility duringfertilization, functioning independently one from another(4, 15, 44, 45, 46, 47). The number of discovered multiplealleles ranges from 25 to 30, depending on the appliedmethod of research. Based on these findings, the geneflow from one population to another is quite fast and,along with good ecological adaptation of the wild cherry,it does not allow significant population differentiation.

When we cannot exclude the effects of applied metho-dology (the number of sampled individuals or selectionof analyzed characteristics) or developmental and an-thropogenic factors in the wild cherry, the existing dif-ferences can sometimes indicate that different adaptationprocesses are taking effect in investigated populations,and can drive the populations from divergent ecologicalconditions toward the same evolutionary direction, thatis, toward the establishment of genetic equilibrium bet-ween populations. Based on our results and the argu-ments given in the discussion, we can present certainpoints of view about the wild cherry:

– The obtained variability in the intrapopulational,and individual level can be associated with verycomplex fertilization mechanisms in the wild che-rry, above all with the activity of a large number ofmultiple S-alleles which are the key factor for thedifferentiation decrease between populations.

– Pollination by insects indicates very rapid gene flowbetween populations, which additionally contribu-tes to the overall low level of differentiation.

– Fast long-distance seed dispersal by birds contribu-tes to fast gene exchange which has a significanteffect on low differentiation level.

52 Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012.

D. Ballian Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina

– Based on analyses of investigated morphologicalfeatures, we could not identify the differentiation ofwild cherry populations in given ecological condi-tions on any basis. Apart from complex and fastgene flow, such results could be a consequence ofthe late colonization of these areas, phylogeneticyouth and fast expansion of the species, and finallystrong anthropogenic and zoogenic impact.

– Regarding soil reaction (pH), wild cherry popula-tions in acid soil did not show any difference withrespect to populations in limestone soil. Further-more, according to geology and soil type, we couldnot find any strong differences between investiga-ted populations.

– Relatively small, isolated populations from higheraltitudes (in our case we are referring to the po-pulations of Kupres, Kalinovik and Sokolac) do notshow any differences at the morphological levelfrom the populations from lower altitudes of thecentral Dinarides and the Alps, which have a lon-ger vegetation period and grow in soils of higherquality. These three populations show a relativelyhigh level of degradation due to very pronouncednegative anthropogenic and zoogenic impact.

Based on our results and our obtained knowledgeabout the variability of the wild cherry in Bosnia andHerzegovina, we can develop quality regeneration plansfor this species, as well as in situ and ex situ geneticdiversity conservation plans.

As we have at our disposal small-size populations oronly individual trees, often with low quality and scarcearrangement of trees in the stand, it is necessary to adopta number of breeding regulations in order to improve thecondition of the trees in the field. This is specificallymeaningful for some of the investigated populations (Kup-res, Kalinovik, Sokolac). For the adaptation and main-tenance of a certain population in situ we have to con-sider the fact that survival depends on basic life factors, aswell as on the individual itself which carries the geneticmaterial, that is, on its ability to transfer the geneticinheritance to the next generation (through vitality, resis-tance, fructification…). Therefore, it is necessary, apartfrom knowing the variability obtained by the appliedmarkers, to know and understand the ecological con-ditions in which the species develops. In general, we canconclude that research of the wild cherry and similarspecies, which are bird-dispersed (ornithochory) and ha-ve a specific fertilization mechanism, is very complexand has to be based on individual-level research, becauseindividuals can grow one next to the other and originatein very distant areas at the same time.

REFERENCES

1. STANKOVI] D 1981 Tre{nja i vi{nja. Nolit. Beograd

2. BOJKOV D, ZAHOV T 1952 Vi{nja i ^ere{a. Zamizdat, Sofija.

3. [ILI] ^ 2005 Atlas dendroflore (drve}e i grmlje) Bosne i Herce-govine. Matica Hrvatska, ^itluk, p 575

4. RUSSELL K 2003 EUFORGEN tehnical Guidelines for geneticconsevation and use for wild cherry (Prunus avium). InternationalPlant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome,Italy, p 6

5. JOVANOVI B 2000 Dendrologija. Univerzitet u Beogradu, p 5366. BALLIAN D 2000 Po~etna istra`ivanja varijabilnosti morfolo{kih

svojstava sjemena divlje tre{nje (Prunus avium L.). [um list 124(5–6):271–278

7. BALLIAN D 2002 Variability of characteristies of the wild cherryblossom (Prunus avium L.) in the region of central Bosnia. Ann SciFor 25(2): 19

8. HERMAN J 1971 [umarska dendrologija. Stanbiro. Zagreb, p 4669. KOLESNIKOVA A F 1975 Breeding and some biological cha-

racteristics of sour cherries in central Russia. Priokstos izdelstvo,Orel, USSR.

10. VULF E V 1960 Flora Krima. t.z.11. MIJAKU[KO T J, MIJAKU[KO V K 1971 Pro formovu rizno

manitnist dikorasloj ^ere{ni (Cerasus avium Moench) na Ukrajini.Ukr Bot @urn 28: 3

12. HRYNKIEWICZ-SUDNIK J 1972 Studia and razmieszeniem iz-mienoscia ozeresni ptasiej (C. avium Moench). Wrostow.

13. VAVILOV N I 1935 Teoreti~erskie osnovi selekcii rastenij. Gosizdatkolhoznoj i sovhoznoj literaturi, Moskva-Leningrad.

14. @UKOVSKY P M 1965 Main gene centers of cultivated plants andtheir wild relation within the territory of the USSR. Euphytica, p 14

15. MI[I] P 1987 Op{te oplemenjivanje vo}aka. Noli, Beograd, p 27016. NINKOVSKI I 1998 Tre{nja. »Nauka i praksa«, Beograd, p 15117. TRINAJSTI] I 1989 1. Morfolo{ka i morfometrijska analiza varija-

bilnosti lu`njaka unutar jednog stabla. 2. Izrada modela za analizumorfolo{ke varijabilnosti. U: Vidakovi} M (ur.) Oplemenjivanje hra-sta lu`njaka. Izvje{taj o znanstveno istra`iva~kom radu u 1988.godini. Zagreb.

18. FRANJI] J 1993 Morfometrijska analiza lista i ploda hrasta lu`nja-ka (Quercus robur L.) u Hrvatskoj. Magistarski rad, Zagreb.

19. FRANJI] J 1994 Odnos du`ine i {irine plojke lista kao pokazateljvarijabilnosti hrasta lu`njaka (Quercus robur L.) Simpozij-Pevalek25–34, Zagreb

20. FRANJI] J 1994 Morphometric leaf analysis as on indicator ofcommon oak (Quercus robur L.) variability in Croatia. Ann Forest19(1): 1–32

21. FRANJI] J 1996 Multivarijatna analiza posavskih i podravskihpopulacija hrasta lu`njaka (Quercus robur L., Fagaceae) u Hrvatskoj.Disertacija PMF, Zagreb.

22. FRANJI] J 1996 Multivariate analysis of leaf properties in thecommon oak (Quercus robur L., Fagaceae) populations of Posavinaand Podravina in Croatia. Ann Forest 21(2): 23–60

23. TRINAJSTI] I, FRANJI] J 1996 Listovi kratkoga plodnoga iz-bojka, osnova za morfometrijsku analizu lista hrasta lu`njaka (Quer-cus robur L., Fagaceae). U: Mati} S, Gra~an J (ur.): Skrb za hrvatske{ume od 1846. do 1996. Unapre|enje proizvodnje biomase {umskihekosustava 1, p 169–178. Hrvatsko {umarsko dru{tvo, Zagreb.

24. FRANJI] J 1996 Morfometrijska analiza varijabilnosti lista posav-skih i podravskih populacija hrasta lu`njaka (Quercus robur L.,Fagaceae) u Hrvatskoj. Glasn [um Pokuse 33: 153–214

25. FRANJI] J, [KVORC @ 2010 [umsko drve}e i grmlje Hrvatske.Sveu~ili{te u Zagrebu, [umarski fakultet. Zagreb, p 423

26. CLEMANTS G 1996 Sweet chery (Prunus avium L.). Metropoli-tana flora, New York.

27. HIEKE K 1989 Praktische dendrologie. Berlin, p 187–21928. JOVANOVI] B 1972 Prunus L. In: Josifovi} M (ed) Flora Srbije, IV,

p 19829. KRSTINI] A, TRINAJSTI] I, GRA^AN J, FRANJI] J, KAJBA

D, BRITVEC M 1996 Genetska izdiferenciranost lokalnih popula-cija hrasta lu`njaka (Quercus robur L.) u Hrvatskoj. U: Mati} S,Gra~an J (ur.) Skrb za hrvatske {ume od 1846. do 1996. Hrvatsko{umarsko dru{tvo, Zagreb.Za{tita {uma i pridobivanje drva 2: 159–168

30. KRÜSSMAN G 1978 Handbuch der Laubghözle. Berlin und Ham-burg, Bd I–II.

31. RUSHFORTH K 1999 Trees. In: Brickell C (ed.) New Encyclo-pedia of Plants and Flowers. London, p 60–111

32. BALLIAN D 2004 Varijabilnost mikrosatelitne DNK u popula-cijama divlje tre{nje (Prunus avium L.) iz sredi{nje Bosne. [um list128(11–12): 649–654

Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012. 53

Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina D. Ballian

33. CIPRIANI G, LOT G, HUANG W G, MARRAZZO M T, PE-TERLUNGER E, TESTOLIN R 1999 AC/GT and AG/CT micro-satellite repeats in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch.): isolations, cha-racterisation and cross-species amplification in Prunus. Theoreticaland Applied Genetics 99(1–2): 65–72

34. GERLACH H K, STROSSER R 1997 Patterns of random amplifiedpolymorphic DNAs for sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cultivaridentification. Angewandte Botanic 71(5–6): 212–218

35. GERLACH H K, STROSSER R 1998 Chain reactions in fruti-cultivar identification with aid of DNA fingerprinting. Erwebsobtban40(4): 103–106

36. GERLACH H K, STROSSER R, YATAAS J 1998 Sweet cherrycultivar identification using RAPD derived DNA finger prints. ActaHorticulturae 468: 63–69

37. IEZZONI A F, HACOCK A H, HAMPSON C R, ANDERSON RL, PERRY R L, WEBESTER A D 1996 Chloroplast DNA variationin sour cherry. Acta Horticulturae 410: 115–120

38. LEVI A, RAWLAND L J, HARTUNG J S 1993 Production ofreliable randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markersfrom DNA of woody plants. Hor Science 28(12): 1188–1190

39. MALUSA E 1993 Molecular biology in philogenetic studies. Evolu-tion and development of cherry species. Rivista di Frutticulture e diOrtofloricultura 55(5): 110–112

40. MALUSA E, MARSCHESINI A 1993 A new method to study thegenetic variation of vegetals for breeding purposes. Note i: study onPrunus. Fitoterapia 64(5): 427–432

41. MALUSA E, SANSAVINI S 1993 Investigation on the interspecificrelations of cherry species by means of restriction fragment lengthpolymorphism (RELP) of chloroplast DNA. Agro Bio Frut: 203–208

42. MALUSA E, SANSAVINI S 1995 Phylogenetic analysis of Prunusspecies with RAPDs. Agro Bio Frut (Italia 6 maggio 1994): 145–149

43. BRIGGS D, WALTERS S M 1997 Plant Variation and Evolution. 3rd

edition. University Press Cambridge, Cambridge, p 51244. PEJKI] B 1980 Oplemenjivanje vo}aka i vinove loze. Nau~na knji-

ga, Beograd, str. 48645. PANDEY K K 1976 Origin of genetic variability: combination of

peroxidase isoenymes determine multiple allelism of the S-gene.Nature 213: 669–672

46. ASCHER P 1966 Gene action model to explain gametophytic self--incompatibility. Euphytica 15: 179–183

47. ASCHER P 1976 Self-incompatibility systems in floriculture crops.Acta Horticultura 63: 205–215

48. BALLIAN D, BOGUNI] F 2006 Preliminary results of investi-gation of morphological traits variation of wild cherry (Prunus aviumL.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Scientific Conference

on occasion of 60 years of activity of Institute of Forestry, Belgrade.PROCEEDINGS, p 47–51

49. LOWE A, HARIS S, ASHTON P 2004 Ecological Genetics: De-sign, Analysis and application. Blackwell Publishing, p 326

50. TZEDAKIS P C, LAWSON I T, FROGLEY M R, HEWITT G M,PREECE R C 2002 Buffered tree population changes in a qua-ternary refugium: evolutionary implications. Science 297: 2044–2047

51. PETI R J, BREWER S, BORDACS S, BURG K, CHEDDADI R,COART E, COTTRELL J, CSAIKL U M, VAN DAM B C, DE-ANS J D, FINESCHI S, FINKELDEY R, GLAZ I, GOICOE-CHEA P G, JENSEN J S, KÖNIG A O, LOWE A J, MADSEN S F,MÁTYÁS G, MUNRO R C, POPESCU F, SLADE D, TABBE-NER H, DE VRIES S M G, ZIEGENHAGEN B, DE BEAULIEUJ L, KREMER A 2002 Identification of refugia and postglacialcolonization routes of European white oaks based on chloroplastDNA and fossil pollen evidence. For Ecol Manage 156: 49–74

52. CHIARUCCI A, PACINI E, LOPPI S 1993 Influence of tem-perature and rainfall on fruit and seed production of Arbutus unedoL. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 111: 71–82

53. JOHANSSON A K, KUUSISTO P H, LAAKSO P H, DEROMEK K, SEPPONEN P J, KATAJISTO J K, KALLIO H P 1997Geographical variations in seed oils from Rubus chamaemorus andEmpetrum nigrum. Phytochemistry 44: 1421–1427

54. KOLLMANN J, PFLUGSHAUPT K 2001 Flower and fruit chara-cteristics in small and isolated populations of a fleshy-fruited shrub.Plant Biology 3: 62–71

55. WILLSON M F, RICE B L, WESTOBY M 1990 Seed dispersalspectra: a comparison of temperate plant communities. Journal ofVegetation Science 1: 547–562

56. LORD J 1999 Fleshy-fruitedness in the New Zealand Flora. Journalof Biogeography 26: 1249–1253

57. HERRERA C M 2002 Seed dispersal by vertebrates. In: Herrera CM, Pellmyrblackwell O (eds). Plant–animal interactions: an evolu-tionary approach Oxford, UK, p 185–208

58. JORDANO P 1995 Angiosperm fleshy fruits and seed dispersers: acomparative analysis of adaptation and constraints in plant– animalinteractions. American Naturalist 145: 163–191

59. JORDANO P, GODOY J A 2000 RAPD variation and populationgenetic structure in Prunus mahaleb (Rosaceae), an animal-dispersedtree. Molecular Ecology 9: 1293–1305

60. HAMPE A 2003 Large-scale geographical trends in fruit traits ofvertebrae-dispersed temperate plants. Journal of Biogeography 30:487–496

61. HAMPE A, ARROYO J, JORDANO P, PETIT R J 2003 Rangewidephylogeography of a bird-dispersed Eurasian shrub:contrasting Me-diterranean and temperate glacial refugia. Molecular Ecology 12:3415–3426

54 Period biol, Vol 114, No 1, 2012.

D. Ballian Population differentiation in the wild cherry (Prunus avium L.) in Bosnia and Herzegovina