An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade

Agreement

This report represents STAR-Vietnam's professional analysis in cooperation with appropriate government counterparts based on available information. It

does not in any way represent an official interpretation of the BTA or monitoring of the BTA implementation process by either the United States or

Vietnamese governments.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

84

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgements 85 Executive Summary 87 I. Introduction 91 II. Vietnam’s International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and

Performance 93 1. Protecting import-competing industry 93 2. Promoting exports 97 3. Vietnam’s recent macroeconomic performance 100 4. International trade performance 103 5. International investment 106 III. The BTA and the Bilateral Economic Relationship 110 1. The BTA and the principle of reciprocity 110 2. Key characteristics of the BTA: obligations and BTA-related policy

reforms 111 3. Bilateral trade and investment: trends and recent developments 117 4. The U.S. market for Vietnamese exports 124 IV. Exporting to the U.S. Under the BTA: The Perspective of Vietnamese

Businesses 131 1. Clothing exporters 131 2. Footwear and leather goods exporters 132 3. How the U.S. business community in Vietnam views the BTA 134 4. Summing up the survey of businesses 135 V. Conclusion 136 VI. Postscript 138 References 143

Executive Summary

85

Tables

Table 1: Products Subject to Quantitative Restriction 94 Table 2: Nominal Tariffs in Vietnam 95 Table 3: Nominal and Effective Tariff Rates by Sector in Vietnam: 1997 and 2002 96 Table 4: Sectoral Growth Rates, Contributions to GDP and Shares in GDP 101 Table 5: Total and Manufacturing GDP by Ownership: 1995 and 2001 102 Table 6: The Number of Private Companies by Type and Sector 102 Table 7: Newly Established Firms since the Enterprise Law 103 Table 8: Export and Import Growth Rates, Shares in GDP and the Trade Deficit 104 Table 9: The Commodity Composition of Exports and Imports: 1995-2002 106 Table 10: FDI and the Capital Account 108 Table 11: The Sector Composition of Foreign Direct Investment Disbursements 109 Table 12: Bilateral Trade Between Vietnam and the US: 1996 to 2002 118 Table 13: MFN and General U.S. Tariff Rates, and Shares in Exports to the EU,

Japan and the U.S. 119 Table 14: The Composition of Vietnamese Exports to the US: 1996 to 2002* 120 Table 15: The composition of Vietnamese Imports from the US: 1996 to 2002* 121 Table 16: Foreign Direct Investment in Vietnam as of December 20, 2002 122 Table 17: US Foreign Direct Investment in Vietnam by Sector as of June 20, 2002 123 Table 18: U.S. Imports of Textiles and Clothing by Country of Origin, 2000 125 Table 19: Asian Exports to the US and the EU in 2000 128 Table 20: Clothing Exports of Selected Asian Countries in 2000 129 Table 21: The Rate of Growth of Vietnamese Exports to the U.S.

by Commodity in the First Months of 2003 141 Table 22: The Rate of Growth of Vietnamese Imports from the U.S.

by Commodity Category in the First Months of 2003 143 Table 23: U.S. Foreign Direct Investment in the First Months of 2003 143 Figures Figure 1: Trade Taxes as a Share of Tax Revenue 96 Figure 2: Effective Rates of Protection in Manufacturing: Selected Southeast Asian

Countries 97 Figure 3: GDP Growth and Inflation: 1996-2002 100 Figure 4: The Share of East and Southeast Asia in Vietnam's Exports and Imports 104 Figure 5: Anti-dumping duty orders in effect on 31 December 2000 126 Figure 6: Countervailing duty orders in effect on 31 December 2000 127

NOTE BY THE PUBLISHER

he Bilateral Trade Agreement between the United States of America and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, herein called the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement came into force on December 10, 2001 and has

advanced the bilateral trade and investment relations between the United States and Vietnam to new heights. The United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement creates opportunities for Vietnamese enterprises to enter into the vast markets of the United States, helping to develop traditional products in which Vietnam has comparative advantage. Implementing the commitments made in the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement, as well, helps Vietnam to improve its business environment in conformity with international best practices and to accede to World Trade Organization. At the same time, however, it presents new competitive challenges that are strong and complex.

In an effort to provide an initial assessment of the positive benefits as well as

remaining challenges and the need for timely adjustments following the first year of BTA implementation, STAR Vietnam in co-operation with the Central Institute of Economic Management has prepared an annual economic report for 2002 with the title of An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement.

The National Political Publishing House hopes that this publication will provide

readers who are interested in this area with important, up-to-date and useful information.

Hanoi, June 2003 THE NATIONAL POLITICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE

T

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

84

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

his Report was prepared by Professor James Riedel, Senior Economic Advisor, and Mr. Steve Parker, Project Director, of the USAID-funded STAR-Vietnam Project, working in cooperation with the Vietnam Central Institute of Economic

Management (CIEM). The report was prepared at the request of the Vietnamese Government Steering Committee for Technical Assistance on BTA Implementation and USAID. Funding for this report was provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development (O6

The authors were assisted by the staff of the STAR project, including: Mr. Phan Vinh Quang, Assistant Project Director; Ms. Do Hoang Anh, Policy and Training Specialist; Ms. Trinh Kieu Trang, Administrative Assistant; and, Mr. Nguyen Duy Minh, Translator. The report benefited from a number of insightful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft and from guidance by Mr. Nguyen Thu Do of our Government Steering Committee and Ms. Jean Gilson, Country Manager of USAID, Vietnam. A preliminary draft of the report was presented at a workshop organized and hosted by CIEM, at which many participants offered comments and suggestions, including: Dr. Dinh Van An, President of CIEM; Dr. Le Xuan Ba, Vice President of CIEM; Dr. Le Dang Doanh, Senior Advisor to MPI; Dr. Vo Tri Thanh, CIEM and, Mr. Vo Van Thuy, Vietnam Institute for Trade of the Ministry of Trade. In addition we are grateful for the written comments and suggestions of: Dr. Susan Adams, IMF; Dr. Ramesh Adhikari, ADB; Mr. John Bentley, Mr. Hank Baker and Ms. Helle Weeke of the STAR-Vietnam Project; Mr. Fred Burke, Baker & McKenzie and Legal Advisor to STAR; Ms. Pham Thi Le Dung, USAID; Mr. Demetrios Marantis, U.S.-Vietnam Trade Council; and, Ms. Claire Pierangelo and Ms. Jessica Adkins, U.S. Embassy and Mr. Michael Cavanaugh, U.S. Consulate in Ho Chi Minh City.

As well, the Report has benefited greatly from the efforts of: Ms. Phan Thanh Ha CIEM and the main coordinator for STAR/CIEM cooperation; Ms. Nguyen Thi Kim Chi, CIEM; Mr. Pham Hoang Ha, CIEM; and Ms. Tran Thi Kim Chi, translator. All remaining errors and omissions, and of course the interpretations and opinions expressed in the Report, are the sole responsibility of the authors.

T

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

his is the first annual assessment of the economic impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement (hereafter BTA or the Agreement) conducted by STAR-Vietnam in cooperation with Vietnam’s Central Institute of

Economic Management. The BTA came into force on 10 December 2001 (“entry into force”). The BTA serves two purposes: (1) it establishes the rules that apply to trade and investment relations between the contracting parties, and (2) it enumerates the trade and investment commitments made by each party (agreed upon reductions or elimination of barriers to trade and investment). Much of the work of STAR-Vietnam over the past year has been the provision of technical assistance to the Government of Vietnam on legal issues related to the implementation of the BTA.1 A further responsibility of STAR-Vietnam is to conduct ongoing analysis of the economic impact of the Agreement, to which aim this report contributes.

Reciprocity is a fundamental principle of every trade agreement, and so too is it fundamental to the BTA. In the more than 100 pages of text and annexes that comprise the Agreement, both parties make numerous and significant commitments with respect to their trade and investment regimes and their legal systems, which in many cases are similar to those required by the WTO. The commitments made by the U.S. and Vietnam, however, are quite different for each party in terms of its scope and timing, largely because of the different levels of development of their legal systems and trade regimes. As a result, the scope and timing of the economic impact on each country from full implementation of the BTA will differ as well.

Because the U.S. is a founding member of the WTO and was a member of the GATT long before the WTO came into being, its legal system and trade regime already had been adjusted to meet the BTA commitments at the time of entry into force. Thus, the principal change made by the U.S. was to grant Vietnam Normal Trade Relations (NTR) or Most Favored Nation (MFN) access to the U.S. market immediately upon entry into force of the Agreement—in other words, to treat Vietnam no less favorably than it treats any of its other trading partners. With the granting of MFN status, U.S. tariffs on imports from Vietnam fell dramatically and immediately, on average from around 40 percent to around 3-4 percent, for the first time opening up the U.S. market

1. The STAR-Vietnam Project, which is funded by the U.S. Agency for International

Development, began operations in Vietnam in mid-October 2001 with the objective of providing technical assistance to support Vietnam’s effective and timely implementation of the BTA. STAR Project activities completed in 2002 and planned for 2003 are described in the Workplan for 2003, which was approved by the Government Steering Committee for Technical Assistance on BTA Implementation. The development of the STAR Project is documented in the Project Document submitted to the Vietnamese government for project approval.

T

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

86

for many products in which Vietnam has a strong comparative advantage (in particular, labor-intensive manufactures).

In response to the new opportunities afforded by the BTA, Vietnamese exports to the U.S. increased by 128 percent in 2002 compared to 2001, while over the same time Vietnam’s exports to the world as a whole increased by only 10 percent. Indeed, about 90 percent of the incremental increase in Vietnamese total exports in 2002 was attributable to the increase in exports to the United States. Not surprisingly, exports of manufactures, which had been most severely restrained by high U.S. tariffs before the BTA, grew disproportionately at an impressive rate of over 500 percent on an annual basis. Within manufacturing, the biggest gainer was clothing exports, which increased to around $900 million in 2002, an 18-fold increase over the amount exported in 2001. While clothing became Vietnam’s single largest export to the United States, dramatic increases in exports of many other manufactured products were also recorded in 2002, such as electrical appliances (270%), furniture (499%), travel goods (5422%) and miscellaneous manufactures (847%). The findings of this report suggest that Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. should continue to grow strongly well into the future, spurred over time by expected increases in investment in export-oriented sectors resulting both from increased demand for exports to the U.S. market and from an improved investment environment in part resulting from full implementation of the BTA.

For Vietnam, although the scope of commitments made in the BTA is extensive, with a number of important changes required upon entry into force of the Agreement, consideration is given to Vietnam’s status as a developing country by allowing for a number of other commitments to be phased in over time. Although the bulk of Vietnam’s commitments are scheduled for implementation within three to four years after entry into force (by December 2004 or 2005), the phasing in of a few commitments extends out to as long as ten years (by December 2011). Many BTA commitments made by Vietnam will require substantial changes in its laws, regulations and administrative procedures and its institutional capacity to implement those changes. These commitments will bring Vietnam much more closely into conformity with international trade norms and standards, and the “applicable rules of customary international law” in many realms of commercial relations, including with regard to the transparency of laws and regulations, intellectual property rights protection, commercial dispute settlement, market access for trade in services, foreign investment regulation, customs procedures and business facilitation.

Most of the impact of the phased-in implementation of Vietnam’s BTA commitments on U.S. trade and investment is expected to be realized over a number of years – noting in particular that Vietnam applied MFN-level tariffs on imports from the U.S. well before entry into force of the BTA. Nevertheless, U.S. exports to Vietnam in 2002, the first year under the BTA, increased by 26 percent, remaining on trend from the previous years even though overall U.S. exports and global trade in general weakened in 2002. Furthermore, U.S. FDI (commitments) in Vietnam increased in 2002, albeit from a relatively low base. As Vietnam’s full obligations under the BTA are implemented, one can expect that bilateral trade and the role of U.S. investment in Vietnam will expand even further to the mutual benefit of both countries.

Carrying out the BTA commitments will contribute importantly to Vietnam’s stated goal of integration into the world economy. The BTA is, however, not the only

Executive Summary

87

instrument Vietnam is using to liberalize international trade and investment policy. It has been engaged for years in trade and investment liberalization unilaterally, and has recently liberalized regionally through participation in the ASEAN Free Trade Area. Vietnam has also stated an intention to make the reforms that will be required to join the WTO, many of which mirror similar commitments in the BTA.

It is useful, therefore, to consider the BTA and its economic effects not in isolation but rather within the context of the overall efforts of the government to integrate into the world economy. This report begins, therefore, with an assessment of Vietnam’s overall international trade and investment policy and performance. It then goes on to review the content of the BTA and to assess its impact on bilateral trade and investment flows. This assessment relies not only on the officially published trade and investment statistics of the two countries, but also on the experiences of Vietnamese businessmen/women engaged in exploiting the commercial opportunities created by the BTA, whose viewpoints were obtained through a series of interviews conducted by STAR in conjunction with CIEM. Since the relative impact of the first year’s implementation of the BTA will be stronger on the Vietnamese economy than on the U.S. economy, this first report on the economic impact of the BTA focuses almost exclusively on the Vietnamese economy.

The review of overall international trade and investment policy and performance clearly reveals a policy of liberalization toward the goal of integration into the world economy. In recent years, trading rights have been expanded and most quantitative restrictions on trade have been eliminated. Although the average tariff rate has not been reduced, the dispersion of tariff rates has declined somewhat, albeit remaining relatively high. As a result, although the average nominal tariff of about 16 percent is not especially high as compared to other developing countries, the average effective tariff (about 70 percent) is quite high. In many respects, the effective tariff is more important than the nominal tariff because it reveals how the overall tariff structure affects the distribution of resources in the direction of industries in which the country lacks a comparative advantage. Previous studies of the effective rate of protection in Vietnam have also concluded that the trade regime contains a strong “anti-export bias.” In this report, we question that conclusion, suggesting instead that whatever anti-export bias there is stems more importantly from the overall policy framework and the relatively high cost of infrastructure services than from the trade regime per se.

Our review of the trade sector and the economy more broadly indicates a structure of production and trade that is somewhat anomalous for a country with Vietnam’s resource endowment and level of development. One anomaly is the relatively small share of manufacturing in domestic production and exports. Within manufacturing, another anomaly is the relatively small share contributed by small and medium sized (SMEs), export-oriented companies, particularly private ones. Although there are these anomalies, it is also apparent that the manufacturing sector is growing in importance and that the role of export-oriented SMEs is expanding, especially in the last few years. This is in part the result of measures taken by the government to make the “playing field” for private companies more level, such as the adoption of the new Enterprise Law. However, it is our contention that another important obstacle to export-oriented manufacturing has been the lack of MFN access to the world’s largest market for labor-

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

88

intensive manufactures, the United States. With the implementation of the BTA, a major obstacle to export-oriented industrialization, and thus most likely also private-sector development, has been eliminated.

The BTA, by conferring the right to export to the U.S. on an MFN basis, has opened up enormous opportunities for Vietnam to expand exports, especially those exports that were most severely restrained by the high level of non-MFN tariffs that applied prior to the BTA, mainly labor-intensive manufactured products. In spite of these opportunities, a great deal of pessimism about the prospects for Vietnamese companies to expand exports to the U.S. prevailed when the BTA was ratified and brought into force in 2001. A commonly held view was that Vietnamese companies lacked the experience, know-how, and information needed to penetrate the large, sophisticated and distant market of the United States.

Vietnam’s strong export response to the BTA in 2002 suggests that much of this pessimism was overstated. The same story told by the trade statistics was revealed by the Vietnamese business managers we interviewed in two important sectors, clothing and footwear. Almost all managers interviewed recognized that the BTA created enormous opportunities for expanding production and exports. Contrary to the often-expressed pessimism, almost none of those interviewed found it particularly difficult to locate customers in the United States. Indeed, most indicated that they had more demand in the U.S. market than they could satisfy. Instead, the main constraint that they face in expanding exports further is insufficient production capacity, a constraint they are working hard to remove through ambitious plans for investments to expand and upgrade plant and equipment.

While the trade statistics and interviews with exporters give a glowing picture of market opportunities in the U.S. opened up by the BTA, another form of pessimism emerged in Vietnam over the course of the first year of BTA implementation, stemming mainly from the publicity surrounding the U.S. anti-dumping case against Vietnamese “catfish” and the negotiations with the U.S. on clothing and textile export quotas. Anti-dumping duties on Vietnamese fish, should they be imposed at the conclusion of the investigation, may well constrain the industry, and it is also possible that the growth in clothing exports will be limited by the U.S. export quotas when they are imposed.

The fact remains, however, that the U.S. is the world’s single largest and perhaps the most open market for manufactures exports from developing countries. U.S. imports of most manufactured products from developing countries, including clothing and textiles, exceed by fifty percent or more the imports of similar products by the European Union, in spite of the fact that the gross income of the EU exceeds that of the United States. “Catfish” and clothing are concerns for Vietnamese producers and government officials, as such concerns are for producers and officials in many other countries that have had similar disputes with the U.S., but the fact remains that the U.S. market offers the greatest opportunity for Vietnam to expand exports.

A Postscript is appended to this Report to provide an update of trade and investment flows for the first two months of 2003 and to respond to several important comments made by reviewers of earlier drafts of this Report.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

89

I. INTRODUCTION

This report is the first annual assessment of the economic impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement (hereafter BTA) to be conducted by the STAR-Vietnam Project in cooperation with Vietnam’s Central Institute of Economic Management. Coming as it does just a year after the BTA went into effect, this assessment is necessarily tentative, since the economic impact of the BTA is for the most part yet to be observed.

The BTA serves two purposes. First, it establishes, and makes legally binding, the rules that apply to trade and investment between the contracting parties. Second, it serves as an instrument of trade liberalization, since in the process of negotiating the BTA each country made “concessions” (promises to reduce or eliminate certain barriers to trade) to the other on a reciprocal basis. The BTA includes an extensive set of commitments by both parties with regard not only to tariffs and quotas on trade in goods, but also to the transparency of laws and regulations, intellectual property rights protection, commercial dispute settlement, market access for trade in services, foreign investment regulation, customs procedures and business facilitation.

The BTA is not, of course, the only instrument Vietnam has employed to liberalize trade. It has been implementing trade liberalization unilaterally for more than a decade and more recently regionally through participation in the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). Vietnam, as well, has committed to join the WTO. It is, therefore, useful at this stage to begin our analysis with a review of Vietnam’s overall economic performance with an emphasis on international trade and investment policy and performance, which we do in Chapter II.

Chapter III provides a summary of the BTA and reviews some of the BTA-related legal and policy reforms made by Vietnam. The chapter also reviews the level and rate of growth of bilateral trade and investment flows from the mid-1990s to the end of 2002, showing that overall Vietnamese exports to the U.S. more than doubled in 2002 in response to the opportunities opened by the BTA, while exports of manufactures grew by more than 500 percent. It concludes with an assessment of the obstacles and opportunities to the expansion of manufactured exports to the U.S. market.

Even though the BTA has been in effect for little more than one year, many Vietnamese companies—state-owned, private and foreign-invested—are responding to the opportunities opened up by the BTA, some more successfully than others. Chapter IV reports the findings of an initial series of interviews undertaken by STAR, in conjunction with the CIEM, of Vietnamese firms exporting, or planning to export, to the United States. We find that many of the early concerns shared by both business managers and government officials in Vietnam about the difficulty of accessing the U.S.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

90

market have proved unwarranted for a number of sectors where Vietnam has a strong comparative advantage. The views of a sample of American businessmen/women working in Vietnam on how the BTA has influenced the business environment in Vietnam and business prospects for the future is also reported in Chapter IV. We conclude in Chapter V with a summary of findings and suggestions for future research and analysis of the impact of the BTA as more and more provisions of the Agreement come into effect over time. A postscript is added that assesses bilateral trade and investment in the first two months of 2003.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

91

II. VIETNAM’S INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT: POLICY AND PERFORMANCE

Vietnam has a stated goal of integrating into the world economy, and has taken measures unilaterally and within regional and bilateral trade agreements to achieve that goal. International economic integration implies a policy of liberalization of international trade and investment, and certainly the overall direction of trade policy in Vietnam is one of liberalization. Nevertheless, while many restrictions on international trade and investment have been removed in the recent past, others remain in effect, and will continue to do so in the foreseeable future. Trade policy in Vietnam, like that in most countries, serves multiple purposes, some of which are mutually incompatible.

1. Protecting import-competing industry

In spite of the overall trend of trade policy toward liberalization, the government’s trade and investment regime remains biased toward protecting a number of import-competing sectors, sectors most typically dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). However, while SOEs remain the principal beneficiaries of trade restrictions, the level and scope of the restrictions that protect them have been progressively reduced over the past decade and will be reduced further in the years to come as Vietnam fulfills its obligations to AFTA, the BTA and eventually the WTO.

a. Restrictions on trading rights have been significantly loosened

Before 1989, SOEs had a monopoly on international trade. In 1989, this monopoly was broken, but the ability of non-SOEs to engage in trade was severely restricted because export and import licenses were required and conditions for obtaining such licenses were onerous (including requiring a contract to export or import in advance, having minimum working capital, and having appropriate “skills”). Since 1998, the licensing requirements for exporting and importing have been largely abolished. Although some restrictions on the products permitted to be traded remain, they are being progressively loosened. In 2001, all legal entities (companies and individuals) were permitted to export most goods without license.2

b. Products with import quotas have been significantly reduced

In the past, import quotas were an important instrument of protection in Vietnam. SOEs dominate in every sector that has been protected by quantitative restrictions. Moreover, SOEs received the bulk of import quota allocations, although in recent years

2. See the implementing decree of the Commercial Law, Decree 44/2001/ND-CP, August 2, 2001.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

92

non-SOEs have been allocated quota for the importation of some of the restricted products. As Table 1 indicates, the number of commodities under quantitative restriction doubled in 1999, mainly as a temporary measure to reduce demand on foreign exchange reserves in the wake of the Asian financial crisis. From 2000 to 2002, however, the use of quantitative restrictions has diminished considerably. Indeed at the end of 2002, only two commodities, petroleum products and sugar, will remain under quota.3

Table 1: Products Subject to Quantitative Restriction

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Petroleum Petroleum Petroleum Petroleum Petroleum Sugar Sugar Sugar Sugar Sugar Fertilizer Fertilizer Steel Steel Cement* Steel Steel Cement/Clinker Cement/Clinker Motorcycles* Cement/Clinker Cement/Clinker Glass Motorcycles Glass Glass Motorcycles Cars Motorcycles Motorcycles Cars Vegetable oil Cars Cars Paper Paper Paper Vegetable oil Electric fans Ceramic tiles Porcelain Caustic soda Bicycles Vegetable oil Plastics Plastic

packaging

*Removed as of December 31, 2002. Source: World Bank, Vietnam: Delivering on its Promises, 2003; World Bank, Vietnam Economic Monitor, 2001; World Bank, Vietnam: Entering the 21st Century, 2000; IMF, Selected Issues and Statistical Annex, 2002; and Decision of the Prime Minister on managing exports and imports in the 2001-2005 period, No.: 46/2001/QD-TTg, April 4, 2001.

c. The average tariff rate has not fallen

Tariffs, like quantitative restrictions, are designed mainly to protect SOEs in Vietnam. In the 1990s, the tariff structure was repeatedly revised and many rates increased to compensate for the loosening of the quota system.4 A recent study reports

3. The imposition of ad hoc quotas remains a problem, however. For example, in September 2002 the government abruptly imposed a quota on motorbike components that was expected to disrupt production of foreign firms like Honda. “Honda’s sweet success goes sour,” Financial Times, September 30, 2002. In response to pressure from the Japanese in particular, and in line with the IMF-WB commitments on import quotas noted in Table 1, this quota was rescinded at the end of December, 2002.

4. There is on-going controversy with regard to how tariff rates are applied on a day-to-day basis, with businesses reporting that the tariff rate applied to a particular good can change over time, often without notice. Given the difficulties that such uncertainty holds for competitive business activity, a careful study of the degree to which this problem occurs and the reason why it occurs could be quite helpful.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

93

that tariffs were raised on certain consumer goods (e.g., cosmetics), upstream activities related to clothing production (e.g., silk, cotton and certain fibers), and selected intermediate inputs (e.g., metal products, cement, and glass), while only in a few sectors (one being machinery) were tariff rates lowered.5 Thus, as Table 2 indicates, the average tariff rate has risen in recent years, while the dispersion of tariff rates (measured by the coefficient of variation) has fallen.6

Table 2: Nominal Tariffs in Vietnam

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001a

Mean tariff rate 12.3 13.4 13.6 16.3 16.2 15.7 CVb 127 128 117 115 118 116 Number of bands 31 35 26 12 19 15

a. As of January, 2002. b Coefficient of Variation = standard deviation/mean. Sources: 1996-2000: IE/NCSSH/IDRC “An Overview of Vietnam’s Trade Policy in the 1990s: The

Changes and Impacts,” Draft, April 2001, p.16; For the year 2001: P. Athukorala, “Trade Policy Reforms, Export Strategies and Incentive Structure in Vietnam,” Draft, March 2002.

An exception to the general rise in average tariff rates is AFTA’s Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) scheme. As a member of AFTA, Vietnam is committed to reduce rates on all but a few “excluded” tariff lines to less than 5 percent by the year 2006. With the promulgation of Decree 21/2002/ND-CP in February, 2002, some 5558 tariff lines out of a total of 6,324 were already on the so-called “inclusion list,” with tariffs lower than 20 percent and destined to be reduced to less than 5 percent over the next three years

Tariffs also serve as an important source of tax revenue. Indeed, before the compression of imports in 1999 and 2000, trade taxes (mainly import duties) were the government’s largest single revenue source, exceeding revenue from the VAT or from personal and corporate income taxes. Government dependence on trade taxes is a matter of considerable concern, since it may well serve as an obstacle to tariff rate reduction in the years to come. In this regard, improving Vietnam’s tax system, in particular its trade-neutral value-added-tax system, will be a critical factor for providing the “revenue space” for reducing tariff levels over time.

5. Athukorala, P., “Trade Policy Reforms, Export Strategies and the Incentive Structure in

Vietnam,” Draft, March 2002, p. 3. 6. The effective tariff rate, which measures the effect of the tariff structure on resource allocation

depends as much on the dispersion of tariff rates across product lines as on the rate of the tariff. See section d below.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

94

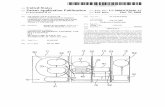

Figure 1: Trade Taxes as a Share of Tax Revenue (percentages)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Source: IMF, Vietnam: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix, January 2002.

d. Effective protection is relatively high

The incentive and resource allocation effects of the tariff structure on any particular sector depend not only on the tariff rate for that sector, but also on the tariff rates that apply to all sectors throughout the economy that provide intermediate and capital goods inputs to the sector, either directly or indirectly. This essentially includes all traded goods sectors. The concept that is frequently used to capture the system-wide effects of the tariff structure is the “effective rate of protection.”7 When the tariff structure is “cascading,” by which is meant that tariffs are higher on final goods and services than on primary goods and intermediate inputs, the result is that the effective tariff rates on final goods and services are likely to be considerably higher than the nominal tariff rate.

As Table 3 indicates, the tariff schedule in Vietnam is one that cascades, with nominal tariffs in agriculture averaging only 6.2 percent as compared to the average in manufacturing of 21.9 percent. Consequently, the effective tariff rate in manufacturing (77.8 percent) is almost four times the nominal rate, suggesting a significant bias in favor of import-competing industries dominated by SOEs.

Table 3: Nominal and Effective Tariff Rates by Sector in Vietnam: 1997 and 2002 (percentages)

1997 2002 Vietnam:

Nominal tariff rate

Effective tariff rate

Nominal tariff rate

Effective tariff rate

Agriculture 8.1 9.1 6.2 12.6 Mining 9.4 5.7 17.8 0.13 Manufacturing 26.9 111.1 21.1 77.8 Overall average 17.4 59.7 15.9 54.2

Source: Prema-Chandra Athuokorala, “Trade Policy Reforms, Export Strategies and Incentive Structures in Vietnam,” Draft, March 2002.

7. For an excellent exposition of the concept of effective protection see W. M. Corden, The Theory

of Protection, Oxford University Press, 1971.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

95

Figure 2 contains estimates of effective protection rates in manufacturing in selected East Asian countries. While the average nominal tariff rate in Vietnam is not significantly higher than in other East Asian developing countries, the effective tariff rate is, an outcome of the relatively high rate of dispersion of tariff rates across industrial sectors.8 For example, in the Philippines where the average nominal tariff in manufacturing is 8.4 percent with a coefficient of variation of 18.9, the effective protection rate is only 10 percent.9

Figure 2: Effective Rates of Protection in Manufacturing: Selected Southeast Asian Countries

0 20 40 60 80 100

Philippines

Malaysia

South Korea

Indonesia

Thailand

Vietnam

Source: Prema-Chandra Athukorala, "Trade Policy Reforms, Export Strategies and the Incentive

Structure in Vietnam,” Draft, March 2002.

2. Promoting exports

Trade policy in Vietnam not only serves to protect SOEs from import competition, it also serves to promote exports. An important theorem of international trade theory (the Lerner Symmetry Theorem) holds that a tax on imports is equivalent to a tax on exports. In other words, restricting imports has the unintended by-product effect of restricting exports. In Vietnam, the government has taken measures to offset the bias against exports that results from tariffs and quotas on imports. For the most part these consist of different kinds of tax exemptions for exporters.

a. Import duty drawbacks for exporters work reasonably well

Vietnam first introduced a scheme to rebate duties on imports of intermediate goods used in export production in 1991. In 1993, a duty suspension scheme was added that allowed exporters to suspend duty payments on imported inputs for 90 days. In 1998, the suspension period was extended to 275 days. According to a recent analysis, the scheme “seems to operate reasonably well.”10 The shortcomings of the scheme derive mainly from the lack of clear operational guidelines at customs. As a

8. With a uniform tariff rate across all sectors, the nominal and effective tariff rates are equal. 9. Prema-Chandra Athukorala, “Trade Policy Reforms and Export Strategies and Incentive

Structures in Vietnam, Draft, March 2002. 10. Athukorala, ibid. p. 9.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

96

consequence, it is reported, customs officials sometimes make arbitrary and unpredictable decisions about what import duties may be rebated or suspended, which of course undermines the incentive effects of the scheme and creates conditions conducive to corruption. Since SOEs typically fare better in this kind of environment than smaller private companies, SMEs tend to rely on SOEs for imported inputs.

b. Other tax exemptions

In addition to rebates of import duties, exporters are exempted from the value-added tax (VAT) and are given concessions on profit taxes, the amount of concession depending on the degree of export-orientation and location (e.g., in rural areas or in industrial and export-processing zones). Foreign-invested firms receive particularly generous tax incentives, typically including duty-free access for machinery and other capital goods imports.11

c. Export subsidies

Vietnam does not provide direct subsidies to exports to any significant extent. However, like many other countries in the region, it does have special facilities to provide credit to exporters. The government has established a Development Assistance Fund and recently a Credit Fund for Supporting Exports. However, a recent assessment of these credit facilities notes that they mainly serve SOEs, which because of their privileged access to commercial bank financing are the least in need of credit assistance.12 Moreover, these funds are mainly limited to investment loans, when in fact exporting firms report that working capital is often of more immediate need.13

d. Export taxes

Export taxes do not usually count as a measure to promote exports, at least not directly. However, to the extent that export taxes apply to intermediate inputs, they may serve that purpose indirectly. This occurs because an export tax tends to reduce the domestic price of the taxed product, which if used as an input in the production of a downstream product, may serve to “subsidize” the export of that product by reducing its input costs. Rice is one product that has been subject to an export tax, albeit at low rates, while metal scrap is subject to a much higher export tax, presumably to promote domestic producers of steel products.

e. Anti-export bias?

Does Vietnam’s trade regime, which serves both to protect SOEs and promote exports, contain an overall bias against exports? Several recent studies argue that in spite of the export promotion measures surveyed above, overall the system remains heavily biased against exports.14 A recent report of the EU Multilateral Trade Policy

11. MPI, Viet Nam: A Destination for Foreign Investment: A guide for business and investment in

Viet Nam, 2002. 12. Athukorala, ibid., p. 14. 13. See Chapter IV below, which reports the findings of interviews with exporting firms. 14. E. Ianchovinchina E. Fukase and W. Martin, “The Effects of the US Vietnam Trade

Agreement,” World Bank, 2000; P. Athukorala, op. cit. and MUTRAP, EU Multilateral Trade Policy

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

97

Assistance Program (MUTRAP) concludes that “Despite the large role of export production in Vietnam’s economy, its trade regime asymmetrically favors domestic production over export production.”15 A recent World Bank study concludes that “The upshot of this analysis is that, while various indirect measures to counterbalance the anti-export bias of the protectionist regime seem to have some effect, they are unlikely to achieve the desired neutrality in the incentive structure even if the efficiency of their implementation is substantially improved.”16

The analysis on which these assessments are based is the application of the effective rate of protection concept. A high effective rate of protection implies that selling in the domestic market is more profitable than selling in export markets. Of course, account must be taken of duty drawbacks and other tax exemptions that apply to exporting but not for selling in the domestic market. However, even after such adjustments are made, these analyses find that there is a strong bias in favor of the domestic market over exporting, even in sectors in which Vietnam has recorded rapid export growth in recent years, such as seafood, food processing, footwear, and clothing.

These analyses lead one to an obvious question, albeit one that none of the studies attempts to answer. That is, how did Vietnam achieve rapid export growth in sectors where the profitability from selling domestically is presumably 50 to 100 percent higher than from selling in the world market?17 The likely answer is that these analyses are misleading because of problems that arise from aggregation. Even within a well-defined sector like clothing, there is great variation across firms in terms of product variety, product quality, the scale of operation and the technology of production. The relatively small firms that produce the variety of clothing favored by local consumers bear little resemblance to the large-scale clothing manufacturers that often use advanced technology to produce a limited variety of clothing items under contract to buyers in the world market. Are the small-scale clothing makers more profitable by virtue of tariffs on clothing imports than the large-scale firms that produce for the world market? There is no evidence that they are. Would the lowering of tariffs on clothing imports negatively affect many small producers supplying the domestic market? Likely so. Would the resources released from import-competing firms be readily absorbed in export production? If what constrains production for export is the overall economic environment, and not the supply of labor and other domestic resources, then probably not.

There may, however, be a potential bias against exports from what could be called “the adding-up” or “resource-pull” constraint. If an economy’s resources are limited, the more resources that are allocated to one sector (e.g., import-competing sectors), the fewer are available to be allocated to other sectors (e.g., export-oriented sectors). Policies that protect and favor the import-competing firms, accordingly, may unprotect and disadvantage the export-oriented firms. In the Vietnamese context, however, this argument is perhaps less applicable than for other countries. In Vietnam some key resources for export production are seemingly unlimited under existing conditions, Assistance Program, “Vietnam’s Industrial Competitiveness under International Economic Integration,” Hanoi, July 18, 2002.

15 . EU Multilateral Trade Policy Assistance Program, op. cit. 16. Athukorala, ibid., p. 21. 17. As noted in Table 3, Vietnam’s average effective rate of protection for manufactures in 2002 is

78 percent. Taken literally, this implies that the profitability for selling manufactures on the domestic market is 78 percent higher than for selling the same product for export.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

98

principally labor. The trade regime makes capital goods and imported raw materials available at close to world market prices, hence the heavy reliance of exporters on imported materials and capital goods. The adding up constraint, where it applies in Vietnam, is mainly in regard to credit, which is limited in availability and allocated unevenly in favor of SOEs. Since private companies are more export-oriented than SOEs, the system of credit allocation may constitute an anti-export bias. If so, then the bias derives more from the overall policy framework, especially those favoring SOEs, than from trade policy per se.

One constraint on exports not related to the trade policy regime is the insufficient availability and high cost of infrastructure services. Port services are reported to be more than twice as expensive in Vietnam than in neighboring countries. Telecommunications rates are among the highest in the world, and electricity tariffs, while reasonably priced, do not compensate for the cost of power cuts. According to a recent report, in spite of relatively low wages, “higher costs for telecommunications, electricity, transportation and other infrastructure services make Vietnamese products 20 to 30 percent more expensive than those produced in other countries.”18

3. Vietnam’s recent macroeconomic performance

a. Growth and stability

Vietnam’s international trade and investment performance should be looked at within the context of the overall economic performance of the economy. In the mid 1990s, Vietnam achieved a remarkable record of rapid growth and falling inflation. With the onset of the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98, however, these positive trends were reversed, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: GDP Growth and Inflation: 1996-2002

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

Inflation Rate Growth Rate

Sources: IMF, Vietnam: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix, 2002, World Bank, Vietnam

Delivering on its Promises, Development Report 2003, December 2003.

Since 1999 the economic growth rate has rebounded, albeit at rates below those recorded in the mid 1990s, and the inflation rate has declined significantly. Given the turmoil in many neighboring countries and the general slowdown in the world economy

18. Le Duc Tan, “Tall Order,” Vietnam Economic Times, June 2002, p. 29.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

99

in recent years, the economy of Vietnam must be judged to have performed reasonably well, if not quite the “beacon of light” that it has been described as.19

b. Structural change

In addition to macroeconomic stability and growth, the economy has been undergoing steady, if not remarkable, structural change. In the early 1990s, the main sources of growth were productivity advances in agriculture, exploitation of oil resources and the flourishing of the commercial sector.20 However, as Table 4 indicates, since 1995, growth of the industrial sector (at an average 10.2 percent) has accounted for over half of the incremental increase in GDP. Within the industrial sector (which also includes mining and quarrying, utilities and construction), manufacturing has grown most rapidly, accounting for more than half the expansion of the industrial sector and almost one-third of the overall increase in GDP over this period.

Table 4: Sectoral Growth Rates, Contributions to GDP and Shares in GDP (percentages)

Growth rate: 1995-2001

Contribution to GDP growth:

1995-2001

Shares in GDP 1995 2001

Agriculture 4.2 17.3 26.2 23.3 Industry 10.2 54.1 29.9 37.7 Manufacturing 11.5 30.9 15.5 20.1 Services 4.1 28.6 43.8 40.0 GDP 6.1 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: GSO, 2002.

The acceleration of manufacturing growth is a significant development, since manufacturing is the single most important potential source of productivity growth over the long run. However, with a share of 20 percent in GDP and a growth rate of 11.5 percent in recent years, there is clearly considerable scope for an acceleration of growth and a greater role for manufacturing in the economy.

c. Pattern of ownership

Structural change has occurred not only in the composition of output but also in the pattern of ownership. By 1995, the domestic private sector accounted for about 44 percent of GDP (see Table 5). Including the foreign-invested sector, the non-state sector accounted for 50 percent of GDP. From 1995 to 2001, the relative role of the non-state sector has remained roughly the same, although the role of foreign-invested companies and private companies has increased while the role of household enterprises has declined. Nevertheless, even by 2001, an important and often overlooked feature of the private domestic sector remains, namely that over 80 percent of the domestic private sector consists of household enterprises and family farms. Private domestic companies,

19. Adam Fforde, “Light with the ASEAN gloom? The Vietnamese economy since the first Asian

Economic Crisis and the light of the 2001 downturn.” Mimeo, 2001. 20. James Riedel, “The Vietnamese Economy in the 1990s,” Asia Pacific Economic Literature,

11(2), November 1997, 58-65.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

100

where capital accumulation and productivity growth is most likely to occur, accounted for only about 7 to 8 percent of GDP in 2001.

In the manufacturing sector, changes in the pattern of ownership have been more profound, with the state’s share falling from 59 to 51 percent from 1995 to 2001. The counterpart of this decline was not, however, a rise in the share of the domestic private sector, but instead a rather dramatic rise in the share of the foreign-invested enterprises in the manufacturing sector, many of which investments are joint-ventures with state-owned enterprises. In 2001, private domestic companies, although growing rapidly from a low base, still account for only about 9 percent of manufacturing value-added (GDP).

Table 5: Total and Manufacturing GDP by Ownership: 1995 and 2001 (percentages)

Share in total GDP Share in mfg. GDP 1995 2001 1995 2001 Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 Public (State & collective) 50.3 49.1 59.1 51.0 Private (Total) 44.4 40.2 28.7 29.0 Household Enterprises 40.3 32.6 26.0 20.0 Private Companies 3.1 7.6 2.7 9.0 Foreign Invested Companies 6.3 10.7 11.4 21.0

Source: GSO, 2002.

The small share of private companies in the economy as a whole and the manufacturing sector in particular is a unique feature of the Vietnamese economy. Even in China, the equivalent of private companies, the township and village enterprises (TVEs), account for a large share of manufacturing value added. Of course, it is useful to remember that, as the saying goes, “Rome wasn’t built in a day.” Vietnam’s private corporate sector has only had a legal foundation for 10 years (since the adoption of the 1992 Constitution), and certainly there has been a flourishing of entrepreneurial activity, though, as Table 6 indicates, mainly in trade and commerce rather than in manufacturing.21

Table 6: The Number of Private Companies by Type and Sector 1995 2000 1995 2000

Total 15,276 31,519 Total 15,276 31,519 Household Enterprises 10,916 23,850 Trade 7,645 18,000 Limited Liability Companies 4,242 7,200 Manufacturing 5,006 6,617 Joint-stock Companies 118 469 Other 2,625 6,902

Source: GSO, 2001.

There are, no doubt, many reasons for the reticence of Vietnamese entrepreneurs to invest in manufacturing, especially in export-oriented manufacturing. An obvious explanation is that the level of investor confidence has not been sufficiently high to attract investors to the manufacturing sector where capital requirements are relatively high and the ability to liquidate in the case of a reversal of fortunes is rather limited. Importantly, another reason has been the lack of MFN access to the U.S. market.

21. See J. Riedel, “The Role of the State and the Market in the Economy of Vietnam,” UNDP, 2000.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

101

Obviously, export-oriented firms are at a distinct disadvantage when the world’s largest market is effectively closed to them. That issue, the topic of the following chapter, has been effectively resolved with the signing of the BTA. As for the business environment, that too has seen some significant improvements in recent years, in particular with the implementation of the new Enterprise Law in 2000.

The response to the new Enterprise Law, which abolished hundreds of needless licenses and permits for doing business, has been quite remarkable (See Table 7). In the nine years prior to the implementation of the Enterprise Law, only 30,000 enterprises were established nationwide, while in the three years since, 56,000 new firms have been established, 31 percent of which have been in the industrial sector (including construction).22

Table 7: Newly Established Firms since the Enterprise Law

Year

Number of enterprises newly established

Registered capital VN dong trillions

2000 14,413 14 2001 21,040 27 2002 20,797 32

Source: Ministry of Planning and Investment

4. International trade performance

a. Trade expansion

As Table 8 indicates, international trade has been the most dynamic component of the Vietnamese economy. The collapse of export growth in 1998 is widely attributed to the Asian financial crisis, since Asian countries are an important destination of Vietnam’s exports (see Figure 4 below).23 However, the compression of imports, which began in 1997, no doubt contributed to the decline in export growth in 1998, since about 40 percent of inputs in industrial production are imported. The decline in export growth in 2001 is also attributable to the slowdown in the world economy and its deleterious effect on the prices of Vietnam’s key primary commodity exports—rice, coffee and petroleum.

22. It has been suggested that some not insignificant proportion of newly registered firms are not

new at all, but instead existed as unregistered (“informal”) firms that took advantage of the Enterprise Law to register as legal entities.

23. In 1997 many companies reported that they were unable to obtain adequate foreign exchange for imports of raw materials and capital goods, hence the subsequent fall off of exports in 1998 may also have been due to domestic supply as well as to foreign demand constraints.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

102

Table 8: Export and Import Growth Rates, Shares in GDP and the Trade Deficit (percentages)

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Export growth rate 34.4 33.2 26.6 1.9 23.3 24.0 4.5 10.0 Import growth rate 40.0 36.6 4.0 -0.8 1.1 30.8 2.3 19.4 Exports/GDP 26.3 29.4 34.3 34.5 40.2 45.6 46.2 n/a Imports/GDP 39.3 45.2 43.3 42.4 40.5 48.5 49.5 n/a Trade balance/GDP -13.1 -15.8 -9.0 -7.9 -0.3 -2.8 2.9 n/a

Source: GSO and CIEM data base.

The shares of exports and imports in GDP, approaching 50 percent, would suggest that Vietnam is one of the more open economies in the world.24 Certainly these figures belie the assertion often made that it is one of the most closed economies of the world. However, an important qualification is in order. Since typically a large proportion of the inputs used in the production of industrial exports is imported, a significant share (the precise amount being unknown) of exports represent the re-export of imported inputs.

Figure 4: The Share of East and Southeast Asia in Vietnam’s Exports and Imports (percentages)

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

70.0%

80.0%

90.0%

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

Exports Imports

Source: GSO as provided by the CIEM.

b. Domestic content

Much is made of the high share of imported inputs in industrial production, especially in export-oriented industries, and often it is recommended that measures be

24. If account were taken for smuggling, the openness of the economy would be even more

apparent than it is in the officially published statistics.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

103

taken to increase “domestic value-added.” However, the concern about “low value-added” is misplaced and rests on a false premise. The fact is that importing inputs does not necessarily reduce domestic value-added, it only skews the ratios of exports and imports to GDP, as noted above. Importing inputs does not reduce value-added because imported inputs must be purchased in the world market with foreign exchange earned by exporting domestic value-added. For example, a shirt that is made of domestic cloth contains no more (and perhaps less) domestic value-added than one that is made of imported cloth that is obtained in the world market with the foreign exchange earned from exporting, say, rice or shrimp or footwear. In effect, domestic shirt makers are using domestically produced rice, etc. rather than cloth to make shirts. Indeed, often the implicit domestic value-added in imported inputs is higher, not lower, than in domestically produced substitutes, because the later are often more capital intensive, less in line with the country’s comparative advantage, and hence contain less “net” value-added. That, after all, is why such inputs are often cheaper to buy in the world market than at home.25

c. Commodity composition

The commodity composition of exports and imports is shown in Table 9. The share of manufactures in total exports does not appear to have increased significantly in spite of an acceleration in manufacturing activity.26 Within manufactured exports, the dominance of clothing and footwear attests to Vietnam’s strong comparative advantage in these traditional labor-intensive products. Certainly there is room for greater diversification into new labor-intensive products (electrical appliances, plastic products, toys and other miscellaneous products) that other developing countries, especially Asian countries, exported in great abundance when they were at a stage of development comparable to Vietnam today.

The commodity composition of imports also reflects Vietnam’s low level of industrial development. At its current level of development, Vietnam is not internationally competitive in many capital goods and industrial raw materials, hence the heavy reliance on imports of these categories of goods. The low share of consumer goods in total imports is no doubt also the outcome of Vietnam’s aggressive policy of import-substitution in sectors producing consumer goods.27

25. The theory and empirical evidence behind this argument was set out more than 25 years ago in

James Riedel: “Factor Proportions, Linkages and the Open Developing Economy”, Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 57, (November 1975), 487-494; “A Balanced Growth Version of the Linkage Hypothesis,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 90 (May 1976), 319-322; “Intermediate Inputs and the Theory of International Trade: A Generalization of the Pure Intermediate Good Case”, American Economic Review, Vol. 68, No. 3 (June 1976) 441-447.

26. Vietnamese trade data do not allow one to aggregate exports and imports into the traditional analytical aggregates of primary products and manufactures. Rough estimates indicate that about primary exports account for about 60 percent and manufactured exports about 40 percent of total merchandise exports.

27. Smuggling almost surely also accounts for the relatively low share of imported consumer goods.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

104

Table 9: The Commodity Composition of Exports and Imports: 1995-2002 (percentages)

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Exports Primary products Rice 9.5 11.7 9.5 10.9 8.9 4.6 4.1 4.4 Coffee 10.6 4.6 5.4 6.3 5.1 3.5 2.7 1.9 Fish/Seafood 8.3 8.9 8.6 9.2 8.4 10.2 12.3 12.2 Petroleum 19.7 18.3 15.6 13.2 18.1 24.2 21.9 19.5 Manufactured products Clothing 8.3 15.7 16.4 15.5 15.1 13.1 13.6 16.4 Footwear 3.8 7.2 10.7 11.0 12.0 10.1 10.8 11.1 Electronic products 4.8 5.3 5.1 5.4 4.2 3.1 Handicrafts 1.3 1.1 1.3 1.2 1.5 1.6 1.6 2.0 Imports Machinery & equipment 25.7 27.6 30.3 30.5 30.1 30.9 Fuels & raw materials 59.1 60.0 59.6 61.0 63.5 63.8 Consumer goods 15.2 12.4 10.1 8.5 6.4 5.3

Source: GSO as provided by CIEM.

5. International investment28

a. FDI policy

Vietnam promulgated its first Foreign Investment Law in 1987 following the decision taken at the Sixth Party Congress in December 1986 to abandon central planning in favor of a “market economy with a Socialist orientation.” Having been created under doi moi, the Foreign Investment Law was considerably more market oriented than the existing domestic commercial law, which was established earlier during the era of central planning and consequently borrowed heavily from the Soviet model. Recognizing that Vietnam would have to compete with other countries in the region for foreign investment, the 1987 law established a remarkably liberal regime for foreign direct investment in Vietnam.29 Since 1987 the foreign investment law has been revised on several occasions, most recently in 2000, in each instance moving the law closer into conformity with the principle of national treatment.

The Foreign Investment Law of Vietnam governs a wide range of issues, including the forms of direct capital investment, procedures for licensing foreign investment, management of foreign-invested enterprises, capital contribution, personnel matters, taxation, accounting, foreign exchange and liquidation.30 As in most other

28. For an excellent discussion of FDI in Vietnam, with interesting comparisons to other countries

in the region, see Le Dang Doanh, “Foreign Direct Investment in Vietnam: Results, Achievements, Challenges and Prospects,” Hanoi, August 16, 2002.

29. Alan Gutterman, ed., Commercial Laws of East Asia, Hong Kong, 1997. 30. Pham Duy Nghia, Vietnam Business Law in Transition, Hanoi, 2002. p. 266.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

105

Asian countries, foreign investment is prohibited where it is deemed to have adverse effects on national defense, culture and historical heritage, or the natural environment. Otherwise foreign investment is permitted in most sectors, although it must be approved and licensed by the authorities. In the case of “sensitive projects,” approval is required by the Prime Minister himself. Amendments to the law in 2000 allow for some “less sensitive” projects to be implemented without the licensing scrutiny of the Ministry of Planning and Investment, with such projects being limited mainly to export-oriented investments.31

The existing Law on Foreign Investment requires a minimum foreign participation of 30% in joint ventures, but does allow 100 percent foreign ownership, except for sectors where FDI is limited to the joint venture form.32 Foreign investors in Vietnam receive a number of special incentives, such as customs duty exemptions in export processing zones and various tax exemptions.33 In addition, as in other countries in the region, the law provides an explicit pledge against expropriation or nationalization and guarantees the right to repatriate capital and profits.34 Foreign investors are subject to higher prices for certain services, though these forms of discrimination are gradually being eliminated as the country moves ever closer to national treatment of foreign investors, as required the BTA and ultimately the WTO. In March 2003 the government further liberalized the foreign investment law (Decree 27 amending Decree 24), moving further toward a registration (vs. licensing) regime and making the process of registration and licensing more transparent. Furthermore, in April 2003, the Prime Minister lifted the compulsory sale of foreign currency for both foreign and domestic enterprises.35

b. FDI performance

Data on Vietnamese FDI vary widely, with different FDI definitions and sources often providing conflicting pictures of reality. 36 The two most common statistics published by the Ministry of Planning and Investment are: 1) FDI commitments; and, 2) FDI disbursements. Disbursements obviously provide a better indicator of net capital inflows for balance of payments purposes, and also should more accurately reflect the impact of FDI on the domestic economy.

In the mid 1990s, Vietnam attracted large inflows of foreign capital, relative to the size of the economy, equivalent to 11.2 percent of GDP in 1995, mostly in the form of FDI. With the onset of the Asian financial crisis, however, foreign capital of

31. It is worth noting that the BTA calls for Vietnam to rely increasingly on registration rather than

licensing of FDI. 32. In practice, a number of foreign-invested firms have 100 percent foreign ownership. Note that

the BTA requires that Vietnam reduce the number of sectors where U.S. ownership is limited, particularly for a number of service sectors.

33. For a useful summary of incentives for FDI see MPI, Vietnam: Destination for Foreign Investment: A guide for business and investment in Viet Nam, 2002.

34. Again, these provisions are to be strengthened with the implementation of the BTA. 35. Decision number 46/2003/QD-TTg, published in the Official Gazette on 22 April 2003. 36. FDI statistics are notoriously inaccurate. Not surprisingly, the statistics reported by the

Government of Vietnam and those reported by the IMF (which net out domestic equity) are often different by a large order of magnitude.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

106

all kinds dried up. Simultaneously, while capital inflows fell, Vietnam still had to repay short-term foreign loans and the longer-term loans of foreign investors. Thus, by 2000, Vietnam generated a net capital outflow, equivalent to 2.5 percent of GDP (see Table 10).

Table 10: FDI and the Capital Account (US$ millions)

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Capital account balance 2333 2105 1681 580 -337 -823 -576 Net FDI inflow 2276 1838 2074 800 700 800 900 Medium & long-term loans -253 43 278 70 -423 77

-276

Short-term capital 311 224 -612 -290 -614 -1700 -1200

Capital account as %GDP 11.2 8.4 6.2 0.8 -1.2 -2.5

1.8

FDI as % capital account 97.9 88.1 124.8 370.4 -209.6 -103.6 156.2 Source: World Bank, Vietnam Development Report, 2003.

c. FDI structure

Table 11 shows the sector composition of FDI flows to Vietnam since 1995. Several notable trends are worth mentioning. First and foremost is the relatively low, albeit rising, share of FDI in light, labor-intensive manufacturing. Most industrial FDI is in heavy industry, which is a capital-intensive activity, as are the other main areas of FDI—oil, construction, transportation and communication, and real estate. Consequently, while FDI accounts for a significant share of GDP (13.3 percent), industrial production (35.5 percent) and domestic investment (18.5 percent), it accounts for only a miniscule share of employment (about 400,000 jobs out of a work force of 40 million).37

A second notable trend in FDI is its growing export orientation. Between 1995 and 2000, the share of FDI in manufactured exports increased from 8.8 percent to 33.8 percent.38 This highly favorable trend reflects several notable features of Vietnam’s international economic relations: first, the dominance of other Asian developing countries as investors in Vietnam, investing increasingly in labor-intensive manufacturing, and secondly, the heavy reliance of Vietnam on Asian countries as both a destination of exports and the source of imports.

Vietnam’s reliance on Asia for investment capital and export markets has both risks and rewards. The Asian Tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, perhaps Thailand and Malaysia) have much to offer Vietnam, having recently traversed the same terrain of economic development. On the other hand, as dynamic as these markets are, they are also relatively shallow compared to those of Europe and North America, where

37. Prema-Chandra Athukorala, “Foreign Direct Investment and Manufacturing Exports:

Opportunities and Strategies,” World Bank, 2002. 38. Ibid.

Vietnam's International Trade and Foreign Investment: Policy and Performance

107

the potential for export growth is greater and the risk from economic disturbances is less because of the very size of these markets.

Table 11: The Sector Composition of Foreign Direct Investment Disbursements

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Total FDI disbursements (US$ mil) 2341 2491 2878 2246 2041 1959Total IMF estimates (US$ millions) 2276 1831 2074 800 700 800Total FDI flows as % of GDP 11.3 10.1 10.7 8.3 7.2 6.5IMF total as % of GDP 11.0 7.4 7.7 3.0 2.5 2.7Flows in US$ millions Industry 801 1141 1326 922 835 910 Heavy industry 314 478 701 491 424 445 Export processing 34 136 88 43 49 14 Light industry 267 412 363 225 182 326 Food 186 116 174 164 178 126Oil and gas 576 377 261 375 345 205Construction 133 261 407 198 152 221Transport & communications 155 82 101 80 106 28Real estate 433 421 488 471 340 299Ag, forestry & fisheries 130 113 234 124 192 208Services 120 95 61 77 71 87Flows as % of total disbursements Industry 34.2 45.8 46.1 41.1 40.9 46.5 Heavy industry 13.4 19.2 24.4 21.9 20.8 22.7 Export processing 1.5 5.5 3.1 1.9 2.4 0.7 Light industry 11.4 16.5 12.6 10.0 8.9 16.6 Food 7.9 4.7 6.0 7.3 8.7 6.4Oil and gas 24.6 15.1 9.1 16.7 16.9 10.5Construction 5.7 10.5 14.1 8.8 7.4 11.3Transport & communications 6.6 3.3 3.5 3.6 5.2 1.4Real estate 18.5 16.9 17.0 21.0 16.7 15.3Ag, forestry & fisheries 5.6 4.5 8.1 5.5 9.4 10.6Services 5.1 3.8 2.1 3.4 3.5 4.4Total disbursements 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source: IMF, Vietnam: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix, 2002. Total FDI disbursements are collected according to Vietnamese government definitions.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

108

III. THE BTA AND THE BILATERAL ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP

1. The BTA and the principle of reciprocity

a. The principle of reciprocity

Trade and investment agreements between countries, whether bilateral, regional or multilateral, serve two purposes. First, they establish, and make legally binding, the rules that apply to trade and investment between the contracting parties, which are especially important because of the inevitable intrusion of domestic politics into international trade policy and the likelihood of trade disputes. Secondly, trade agreements serve as an instrument of trade liberalization, since in the process of negotiating a trade agreement each country, as a rule, offers commitments (promises to reduce or eliminate certain barriers to trade) to the other on a reciprocal basis. Where these commitments involve a requirement that a country change its policies at the request of another country, such commitments are sometimes called “concessions.”

“Reciprocity” is a key principle of all trade agreements, since it is the promise of greater access to the other country’s market that is the political rationale for the parties to negotiate a trade agreement with each other. From an economics perspective, reciprocity is not significant, since the main beneficiary of trade barrier reductions is the country reducing its own barriers. The principle of reciprocity makes sense from a political perspective, however, since trade agreements have to be “sold” to domestic political constituents who often mistakenly consider the favorable effect on exports of other countries’ “concessions” to be the main source of benefit from trade liberalization agreements. Most of the benefit of trade and investment reform, however, flow from the more efficient allocation of resources in the country making those reforms, resulting in more productive industries that contribute to higher levels of productivity and sustained economic development.

b. Reciprocity in the BTA

The BTA, like other trade agreements, establishes legally binding rules that henceforth will govern trade and investment relations between the two countries, and it specifies the reciprocal commitments that each country will make to reduce barriers to bilateral trade and investment flows. In the more than 100 pages of text and tables that comprise the Agreement, both countries make numerous and significant commitments with respect to their trade and investment regimes and their legal systems, in large part mirroring similar requirements in the WTO. In reading the extensive BTA document, one may be struck by the fact that the BTA commitments require Vietnam to make many more changes to its trade and investment regime and its legal system than is required to be made by the United States. For the U.S., the principal BTA commitment requiring change in its legal and trade regime was to grant Vietnam NTR/MFN access to the U.S. market immediately upon entry into force of the Agreement.

The principle of reciprocity is, however, alive and well in the BTA. The United States, an advanced economy that has been engaged in multilateral trade liberalization for decades, has already eliminated most barriers to trade and investment on a MFN

The BTA and the Bilateral Economic Relationship

109

basis. With the granting of MFN status, Vietnam immediately becomes the beneficiary of the commitments (concessions) that the United States has made to other countries on a MFN (now NTR) basis over the past fifty years. Vietnam, on the other hand, as a developing economy, is allowed to retain certain trade and investment barriers that the WTO prohibits in developed countries, and is permitted to phase-in the concessions it made in the BTA over a number of years.

The BTA, nevertheless, is quite demanding in terms of the commitments Vietnam has agreed to make. As a latecomer to international trade negotiations, Vietnam has been required to meet standards that are higher than were demanded of developing countries in the past. While meeting the BTA commitments will impose an adjustment burden on sectors that in the past have been highly protected from international competition, it will also encourage efficient resource allocation and prepare Vietnam for accession to the WTO.39

2. Key characteristics of the BTA: obligations and BTA-related policy reforms

a. BTA obligations

The BTA is the most comprehensive bilateral trade agreement ever negotiated by either Vietnam or the United States, with extensive obligations for both Parties. The Agreement consists of well over 100 pages of text and tables and is elaborated in seven Chapters: I) Trade in Goods; II) Intellectual Property Rights; III) Trade in Services; IV) Development of Investment Relations; V) Business Facilitation; VI) Transparency-Related Provisions and Right to Appeal; and, VII) General Articles.40 Many of the obligations in the BTA reflect the internationally recognized rules, regulations and administrative procedures that are incorporated in the WTO and other international conventions and agreements that have been developed to govern global trade and investment relations.

The BTA specifically recognizes Vietnam’s status as a developing country. Accordingly, while a number of Vietnam’s commitments in the BTA were due immediately upon entry into force of the Agreement (December 10, 2001), others will be phased in over various time periods from one to ten years, with most key commitments due within three to four years after entry into force of the Agreement. The U.S. met all its obligations when the Agreement came into effect by providing NTR/MFN trade status for Vietnam. This reduced the average U.S. tariff rate for Vietnamese exports to the United States from around 40 percent to around 3-4 percent.

The BTA, much like the WTO, is a modern “trade” agreement, in the sense that it includes extensive obligations related not just to import tariffs and quotas, but also to transparency, dispute settlement, investment, intellectual property protection, market access for services, and business facilitation. In fact, the BTA requires that Vietnam cut

39. Much the same situation holds for Vietnam’s accession to the WTO. Standards for those countries recently entering the WTO are far more stringent than standards for developing economies joining the GATT in previous decades.

40. The English text of the BTA, with accompanying side letters, is available on the USTR webpage (www.ustr.gov). The Vietnamese language text is published in the Official Gazette of the Vietnamese Government.

An Assessment of the Economic Impact of the United States - Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement

110