Person centred discharge education following coronary artery ...

A survey on provision of patient-centred care by a government homeopathic hospital in India

-

Upload

drranjanbhattacharyya -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of A survey on provision of patient-centred care by a government homeopathic hospital in India

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Spatula DD 79

Original Research Spatula DD. 2014; 4(2):79-88

A survey on provision of patient-centred care by a government homeopathic hospital in India

Hindistan’daki bir homeopatik devlet hastanesinde hasta merkezli bakımın sağlanması üzerine bir anket

Subhranil Saha1, Munmun Koley1, Shubhamoy Ghosh2, Goutam Nag2, Monojit Kundu2, Ramkumar Mondal2, Rajib Purkait2, Supratim Patra2, Seikh Swaif Ali2

1Clinical Research Unit (Homeopathy), Siliguri, under Central Council for Research in Homeopathy, Government of India.

2Mahesh Bhattacharyya Homeopathic Medical College and Hospital, Government of West Bengal, Howrah, West Bengal, India

SUMMARY Objective: We derived 32 indicators from the International Alliance of Patients’ Organization’s (IAPO) patient-centred healthcare indicator review those seemed to be applicable for a homeopathic context and intended to test it on the patients suffering from various chronic conditions and visiting the out-patients of a homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, India. Methods: The patient-centred care (PCC) questionnaire was developed in eight steps, and approved by an expert committee. It had three subscales – system level indicators [SLIs: 14 items], patient feedback indicators [PFIs: 3 items], and practitioner level indicators [PLIs: 15 items]. Face validity was tested by 15 people for comprehension. Test-retest reliability was tested on 30 patients and internal consistency on systematically sampled 377 patients. Results: The overall PCC-32 score% appeared to be moderate, of 67.63% ± 14.39; and the subscale scores were 64.82% ± 14.95, 65.03% ± 29.47, and 70.77% ± 11.96. Only PFI scores differed significantly by education [P = 0.009] and health status [P = 0.006]. The questionnaire showed acceptable item-corrected correlations for the subscales [SLIs: ICC 0.98 (0.97, 0.98); PFIs: 0.89 (0.87, 0.91); PLIs: 0.98 (0.97, 0.98)], considerable test-rest reliability [SLIs: 0.19 – 1.00; PFIs: 0.60 – 0.65; PLIs: 0.07 – 1.00], strong internal consistency [Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87 overall and 0.84 – 0.87 for subscales], and considerable responsiveness [0.3 – 2.2]. Conclusion: The provision of patient-centred care by a government homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, India appeared to be quite promising. The psychometric properties of the Bengali PCC-32 were satisfactory, rendering it a valid and reliable instrument. Keywords: Patient centred care, Disease management, Homeopathy, India

ÖZET Amaç: Uluslararası Hastalar Örgütü Birliğinin (International Alliance of Patients’ Organization-IAPO) hasta merkezli sağlık göstergesi incelemesinden homeopatik bağlamda uygulanabilir olan, çeşitli kronik durumlardan muzdarip hastalar üzerindeki testler için tasarlanmış, Batı-Bengal/Hindistan homeopatik hastanesine ayaktan başvuran hastalara uygulanmak üzere 32 indikatör belirlendi. Yöntem: Hasta merkezli bakım anketi sekiz aşamalı olarak tasarlandı ve uzman bir komite tarafından onaylandı. Anketin üç alt skalası bulunmaktaydı; system seviye göstergesi [SLIs: 14 madde], hasta geribildirim göstergesi [PFIs: 3 madde] ve uygulayıcı seviye göstergesi [PLIs: 15 madde]. Nominal geçerliliğin anlaşılması için 15 kişi üzerinde test yapıldı. Test- tekrar test güvenilirliği iç tutarlılık ile sistematik olarak örneklenmiş 377 hastadan 30 hasta üzerinde test edildi. Bulgular: Genel olarak % PCC-32 skorunun orta seviyede (% 67.63 ± 14.39) olduğu görüldü, ayrıca alt grup skorları da % 64.82 ± 14.95, % 65.03 ± 29.47 ve % 70.77 ± 11.96 şeklinde sıralanmaktadır. Sadece PFI skorlarında eğitim ve sağlık durumu ile farklılık ortaya çıkmıştır [P = 0.009] ve [P = 0.006]. Anket; alt skalalar için kabul edilebilir madde-düzeltmeli korelasyon [SLIs: ICC 0.98 (0.97, 0.98); PFIs: 0.89 (0.87, 0.91); PLIs: 0.98 (0.97, 0.98)], önemli ölçüde test-tekrar test güvenilirliği [SLIs: 0.19 – 1.00; PFIs: 0.60 – 0.65; PLIs: 0.07 – 1.00], güçlü iç tutarlılık [Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87 genel ve 0.84 – 0.87 alt skalalar için] ve önemli ölçüde duyarlılık göstermiştir [0.3 – 2.2]. Sonuç: Batı Bengal/Hindistan’da homeopatik bir devlet hastanesinde hasta merkezli bakımın sağlanmasının oldukça umut verici olduğu görülmüştür. Bengalce hazırlanmş olan PCC-32 anketinin psikometrik özellikleri tatmin edici düzeydeydi, bu durum da anketi değerli ve güvenilir bir araç yapmaktadır. Anahtar kelimler:

Corresponding Author: Subhranil Saha, Clinical Research Unit (Homeopathy), Siliguri, under Central Council for Research in Homeopathy, Government of India; Gokhel Road, Arabindapally, Siliguri, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India. Email: [email protected]

Received March 10, 2014 ; accepted April 16, 2014 DOI 10.5455/spatula.20140416032809 Published online in ScopeMed (www.scopemed.org). Spatula DD. 2014; 4(2):79-88.

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Survey on patient-centred care

80 Spatula DD

INTRODUCTION

Patient-centred care (PCC) is health care that is respectful of, and responsive to, the preferences, needs and values of patients and consumers [1]. It is “a balanced consideration of the values, needs, expectations, preferences, capacities, and health and wellbeing of all the constituents and stakeholders of the health care system” [1]. The widely accepted dimensions of PCC are respect, emotional support, physical comfort, information and communication, continuity and transition, care coordination, involvement of family and carers, and access to care [2]. Research demonstrates that PCC improves patient care experience and creates public value for services. When healthcare administrators, providers, patients and families work in partnership, the quality and safety of health care rise, costs decrease, and provider satisfaction increases and patient care experience improves. PCC can also positively affect business metrics such as finances, quality, safety, satisfaction and market share.

In the 4th Geneva conference on person-centred medicine, held during April 30 – May 4, 2011, a considerable body of evidence was summarized indicating that crucial elements of clinician-patient interaction such as empathy, respect, acceptance, non-judgmental attitudes, openness, information-sharing and joint decision-making may lead to greater patient satisfaction, acceptance of treatment and better health outcomes. Also emphasized was the importance of building trust and striving to attain professional competence, ethics, faithfulness and effective communication and collaboration [3].

Responses to homeopathic treatment, patient benefits, empathy and enablement have previously been evaluated in some earlier studies in Western countries using the Glasgow Homoeopathic Hospital Outcomes Scale (GHHOS), Outcome in Relation to Impact on Daily Living (ORIDL), Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP), Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE), Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI), European Quality of Life Questionnaire (EQoL), and Short Form-12 (SF-12) questionnaire [4-9]. The authors themselves studied patient satisfaction using a translated version of Japanese consultation satisfaction questionnaire for the first time in any Indian homeopathic hospital and reported elsewhere [10]. However, PCC has not been evaluated before in the true sense of the term. We derived 32 indicators from the IAPO Patient-centred Healthcare Indicator Review (for consultation) those seemed to be applicable for a homeopathic perspective and tested it on the patients visiting the

out-patients of a homeopathic hospital in West Bengal, India. Assessment of current practice with a valid set of indicators is the key to successfully improving the quality of PCC.

METHODOLOGY

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of MBHMC&H. All participants were provided with patient information sheets in local vernacular Bengali and informed consents were obtained. The survey matter and question items were also explained verbally to the participants by the research assistant to facilitate easy understanding.

Inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 years and above, suffering from chronic diseases for more than a year, completing their physician’s consult, giving written informed consent, and being ready to share information. Exclusion criteria were patients, who were too sick for consultation, unable to read patient information sheets, unwilling to stay after the doctor’s visit, not giving consent to join the survey, and patients involved in the ongoing research projects in the institution to minimize ‘extra care’ bias provided to this sample.

No patients’ identifiable information was required, ensuring anonymized protection of patient’s privacy. Also the filled-in questionnaires by the research assistants were concealed by putting those inside opaque envelops, which were sealed at the survey site. All these were sent for data extraction in a specially designed Microsoft Excel master chart that was subjected to statistical analysis in different statistical computational websites.

The eight different stages that were needed for the development of the study questionnaire are seen in Figure 1.

Stage 1 (draft of initial version): Items were derived from the IAPO review [2] and the initial version was drafted by incorporating the items those seemed to be appropriate in homeopathic perspective.

Stage 2 (committee approval): After little modifications, the items were finalized in the committee meeting.

Stage 3 (forward translation): For the forward translation from English into Bengali, two independent native Bengali speaking translators translated the English version of PCC-32 into the target language Bengali (T1 and T2). One of the translators was a clinician and therefore aware of the concepts that were being measured with the PCC-32 and the other translator was a language specialist with no medical background.

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Saha et al.

Spatula DD 81

Figure 1. Translation and development sequence of the Bengali PCC-32 questionnaire

Stage 4 (synthesis of T1 and T2 into T1,2): The two translators had to then agree on one new consensus version of the translation (T1,2). This consensus version was overseen by the expert committee overseeing the project.

Stage 5 (back translation): For the back translation from Bengali into English, two English language translators (BT1 and BT2) were required. Though born in India, they both have been residing in the United States for over 15 years. They both independently translated T1,2 back into English. They were blinded to the original English version of the PCC-32 during this process.

Stage 6 (expert committee): The committee consisted of methodologists, health professionals, translators and a language professional. The committee reviewed all the translations (T1 and T2, T1,2, B1 and B2) and the written report comparing the back-translations with the forward translation T1,2. Based on those translations, the pre-final version was developed.

Stage 7 (face validity): The pre-final version of the questionnaire was tested on randomly (simple random sampling) chosen 15 patients visiting out-patients of MBHMCH. Each completed the questionnaire and was then asked the meaning of each questionnaire item as well as whether or not they had problems with the questionnaire format, layout, content, clarity, language, instructions or response scales. Any difficulties were noted and included in the final report. A detailed report written by the interviewing person, including proposed changes of the pre-final version based on the results of the face validity test was then submitted to the expert committee.

Stage 8 (committee appraisal): The final version of the Bengali PCC-32 was developed by the committee based on the results of the face validity testing and the written report. Thus all stages 1-8 were successfully completed. The final version of the PCC-32 for patients can be found in figures 2a and 2b.

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Survey on patient-centred care

82 Spatula DD

Figure 2a. PCC-32 survey questionnaire English version (page 1)

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Saha et al.

Spatula DD 83

Figure 2b. PCC-32 survey questionnaire English version (page 2)

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Survey on patient-centred care

84 Spatula DD

Test-retest reliability The Bengali PCC-32 questionnaire was tested for

reliability by administering repeatedly on 30 patients at 2 months interval. The questionnaire item domains were given in different random order for the second administration to avoid the patients memorizing their initial responses.

Validation The purpose of cross-cultural adaptation is to try

and ensure consistency in the content and face validity between the original and the translated versions of a questionnaire. Content validity of the PCC-32 questionnaire was previously evaluated in the original English version, and was therefore not tested in this study. Thus in a cross-sectional study in January - February 2014, 377 patients from different outpatient clinics of MBHMCH were asked to fill in the new Bengali version of the PCC-32 provided with a 4-point frequency Likert (strongly agree: 4, strongly disagree: 1). Another section in the questionnaire sought information regarding patients’ gender, age, chronic conditions, self-rated health status, level of education, and monthly household income. The questionnaires were given to them in the practice to fill in immediately. Sample size of 377 was determined taking into account a margin of error of 5%, confidence level of 95%, population size unknown, and response distribution estimated to be 50%. Systematic sampling method was used for recruitment of the patients. Sampling fraction was estimated (and approximated) to be 5/6 (n/N; n = required sample size of 377; N = average number of out-patient patients every day, that is 450); 5 was decided as the sampling unit by simple random sampling, and thus every 5th patient was interviewed.

Statistical analysis Test-retest reliability of the Bengali PCC-32 was

evaluated by using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) values of ≥ 0.30 considered as good. The internal consistency of the Bengali PCC-32, which measured the degree to which items that made up the total score were all measuring the same underlying attribute, was assessed using Cronbach α values of ≥ 0.6 as acceptable. The sensitivity to change over time of one month of the questionnaire was assessed with the standardized response mean (SRM).

Descriptive statistics was presented as absolute values, percentages, means and standard deviations. Baseline differences were tested using one way analysis of variance and independent t test. P values

less than 0.05 two-tailed were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics Out of 445 patients approached, 377 (response rate

84.7%) returned complete questionnaire. Mean total PCC-32 score% seemed to be moderate; 67.63% (s.d. 14.39), and those of the three subscales were 64.82% (s.d. 14.95), 65.03% (s.d. 29.47), and 70.77% (s.d. 11.96). Majority of the respondents were women (n = 205; 54.4%), belonged to the age group of 18-30 years (n = 128; 33.9%), had education status of less than high school (n = 212; 56.2%), monthly household income of less than rupees 10,000 (n = 286; 75.9%), suffering mostly from gynaecologic complaints (n = 123; 32.6%), with self-rated health status of poor to fair (n = 217; 57.6%). (Table 1)

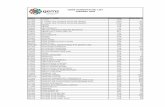

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n = 377)

Patient group N (%)

Gender

� Men 172 (45.6)

� Women 205 (54.4)

Age groups (years)

� 18 – 30 128 (33.9)

� 31 – 45 105 (27.9)

� 46 – 60 96 (25.5)

� > 60 48 (12.7)

Educational status

� Less than high school 212 (56.2)

� High school 149 (39.3)

� Graduate or above 17 (4.5)

Monthly income (Indian rupees)

� < 10,000 286 (75.9)

� ≥ 10,000 91 (24.1)

Chronic conditions

� Gynaecologic 123 (32.6)

� Surgical 57 (15.1)

� Rheumatologic 50 (13.3)

� Others 147 (39.0)

Health status

� Poor to fair 217 (57.6)

� Good 154 (40.8)

� Very good to excellent 6 (1.6)

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Saha et al.

Spatula DD 85

Table 2. Results for overall PCC-32 scale and subscales score% by patient characteristics (n = 377)

Patient groups SLIs P value PFIs P value PLIs P value

Gender‡

� Men 65.7 (15.3) 0.278

66.8 (29.2) 0.270

71.7 (11.8) 0.135

� Women 64.0 (14.6) 63.5 (29.6) 70.3 (11.9)

Age groups (years) †

� 18 – 30 65.9 (11.2)

0.569

69.5 (27.9)

0.080

71.7 (9.4)

0.575 � 31 – 45 63.3 (16.6) 59.7 (30.8) 69.7 (13.6)

� 46 – 60 64.5 (15.5) 65.9 (28.0) 70.8 (11.9)

� > 60 65.8 (18.1) 63.0 (31.3) 71.9 (13.7)

Educational status†

� < High school 64.5 (16.9)

0.738

61.2 (31.9)

0.009*

70.3 (13.4)

0.396 � High school 64.9 (12.2) 68.9 (25.8) 71.5 (9.9)

� Graduate or above 67.4 (9.3) 77.9 (15.4) 73.7 (6.7)

Monthly income‡

� ≤ 10,000 65.3 (15.9) 0.240

64.0 (30.3) 0.252

71.2 (12.7) 0.520

� > 10,000 63.2 (11.1) 68.1 (26.3) 70.2 (8.9)

Chronic conditions†

� Gynaecologic 65.4 (15.5)

0.827

61.9 (31.6)

0.237

70.9 (12.9)

0.512 � Surgical 64.6 (16.7) 62.4 (31.9) 70.5 (13.1)

� Rheumatologic 66.5 (16.1) 70.3 (24.7) 73.1 (11.9)

Health status†

� Poor to fair 65.9 (16.7)

0.086

61.7 (33.6)

0.006*

71.2 (13.5)

0.250 � Good 63.7 (11.5) 70.4 (21.5) 70.9 (9.0)

� Very good - excellent 54.5 (18.5) 47.2 (19.6) 63.0 (14.4)

Values are presented as mean (s.d.); ‡ Independent t test; † One way ANOVA; *P less than 0.05 two-tailed considered as statistically significant

Subscale scores and sample characteristics PCC-32 subscale score% did not seem to differ

significantly by the variables. Only education (F = 4.824; P = 0.009) and health status (F = 5.173; P = 0.006) could influence PFIs significantly; SLIs and PLIs were not influenced by any. (Table 2)

Item-corrected correlations and internal

consistency of the Bengali PCC-32 The Cronbach α of the three subscales ranged

between 0.84 and 0.87; and of the overall instrument was 0.87 indicating acceptable consistency. Item-corrected total correlations (Pearson’s r) of the SLIs, PFIs, and PLIs were 0.98 (95% CI 0.97, 0.98), 0.89 (95% CI 0.87, 0.91), and 0.98 (95% CI 0.97, 0.98) respectively. Except few items (questions 1, 6, 18, 24, 26, and 30), individual item-corrected total correlations of the question items were above the cut-

off point of 0.30 and contributed to the subscale scores. (Table 3)

Test-retest reliability of the Bengali PCC-32 The ICC values for the Bengali PCC-32

questionnaire are presented in Table 4. The SLIs (0.19 – 1.00), PFIs (0.60 – 0.65), and PLIs (0.07 – 1.00) reflected negligible to very strong positive correlations and significance (P < 0.05 two-tailed). Except question items 21, 23, 25, and 31, SRM (responsiveness) of the question items was quite considerable of 0.3 – 2.2. (Table 4)

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Survey on patient-centred care

86 Spatula DD

Table 3. Item-corrected total correlations and internal consistency of the Bengali PCC-32 (n = 377)

Question items and subscales Pearson’s r (95% CI) Cronbach’s alpha

System level indicators 0.98 (0.97, 0.98) 0.86

� Q-1 -0.20 (-0.30, -0.10)

� Q-2 0.41 (0.32, 0.49)

� Q-3 0.90 (0.88, 0.92)

� Q-4 0.87 (0.84, 0.89)

� Q-5 0.89 (0.87, 0.91)

� Q-6 0.28 (0.19, 0.37)

� Q-7 0.61 (0.54, 0.67)

� Q-8 0.59 (0.52, 0.65)

� Q-9 0.62 (0.55, 0.68)

� Q-10 0.54 (0.47, 0.61)

� Q-11 0.56 (0.49, 0.63)

� Q-12 0.51 (0.43, 0.58)

� Q-13 0.77 (0.73, 0.81)

� Q-14 0.78 (0.74, 0.82)

Patient feedback indicators 0.89 (0.87, 0.91) 0.84

� Q-15 0.72 (0.67, 0.77)

� Q-16 0.89 (0.87, 0.91)

� Q-17 0.88 (0.86, 0.90)

Practitioner level indicators 0.98 (0.97, 0.98) 0.87

� Q-18 0.10 (-0.001, 0.20)

� Q-19 0.56 (0.49, 0.63)

� Q-20 0.65 (0.59, 0.70)

� Q-21 0.53 (0.45, 0.60)

� Q-22 0.43 (0.34, 0.51)

� Q-23 0.81 (0.77, 0.84)

� Q-24 0.20 (0.10, 0.30)

� Q-25 0.55 (0.48, 0.62)

� Q-26 0.05 (-0.05, 0.15)

� Q-27 0.93 (0.92, 0.94)

� Q-28 0.82 (0.78, 0.85)

� Q-29 0.80 (0.76, 0.83)

� Q-30 0.27 (0.17, 0.36)

� Q-31 0.64 (0.58, 0.70)

� Q-32 0.34 (0.25, 0.43)

Total score 0.87

DISCUSSION

The developed questionnaire appeared to be a reliable instrument to measure patient-centred care in homeopathic hospital setting. The level of internal consistency was strong, inter-class correlations were acceptable, and the test-retest reliability and responsiveness of the instrument were considerable. Patient-centred care was found to be moderate, and its three subscales scores as well. Only PFI scores

differed significantly by education and health status; however, cross-sectional design of the study impedes to establish any cause and effect relations. Internal consistency might further be improved by rephrasing few question items which have relatively low item-rest correlations.Our study was limited in the sense that the respondents who were absent in the days of the survey, might have scored differently. Also, our study was restricted to the respondents from a single government homeopathic hospital in West Bengal

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Saha et al.

Spatula DD 87

only, limiting generalizability to other Indian scenario. Additionally, inevitable incorporation of central tendency bias and acquiescence bias arising from the use of Likert scale responses into the analysis could not be eliminated. Despite these limitations, this study also has several strengths. First, it was the first ever conducted study that captured

information on this context. Second, to reduce bias, the respondents were sampled systematically. Third, the homeopathic care provided by the homeopathic hospital was similar to the average Indian homeopathic care, and thus our study appears to be generalizable to India.

Table 4. Test-retest reliability of the Bengali PCC-32 questionnaire (n = 30)

Question items and subscales ICC 95% CI P value SRM

System level indicators

� Q-1 1.00 0.99, 1.00 0.001* 0.728

� Q-2 0.39 0.04, 0.66 0.0001* 0.883

� Q-3 0.53 0.21, 0.75 0.0001* 0.928

� Q-4 0.19 -0.18, 0.52 0.0001* 1.177

� Q-5 0.67 0.41, 0.83 0.0001* 0.702

� Q-6 0.39 0.04, 0.66 0.0001* 0.883

� Q-7 0.66 0.39, 0.82 0.006* 0.392

� Q-8 0.42 0.07, 0.68 0.0006* 0.970

� Q-9 0.79 0.60, 0.89 0.006* 0.460

� Q-10 0.25 -0.12, 0.56 < 0.00001* 1.213

� Q-11 0.92 0.84, 0.96 0.0007* 0.347

� Q-12 0.44 0.09, 0.69 0.0007* 0.663

� Q-13 0.51 0.18, 0.74 0.003* 0.442

� Q-14 0.30 -0.07, 0.59 0.002* 0.663

Patient feedback indicators

� Q-15 0.65 0.38, 0.82 0.0007* 0.588

� Q-16 0.60 0.31, 0.79 0.0005* 0.728

� Q-17 0.64 0.36, 0.81 0.012* 0.525

Practitioner level indicators

� Q-18 0.07 -0.30, 0.42 < 0.00001* 1.250

� Q-19 0.64 0.36, 0.81 0.057 0.392

� Q-20 0.09 -0.28, 0.44 < 0.00001* 1.50

� Q-21 0.47 0.13, 0.71 0.083 0.0

� Q-22 0.19 -0.18, 0.52 0.0001* 1.20

� Q-23 0.86 0.73, 0.93 0.161 0.0

� Q-24 0.20 -0.17, 0.52 < 0.00001* 1.50

� Q-25 0.69 0.44, 0.84 0.326 0.0

� Q-26 0.29 -0.08, 0.59 0.001* 0.883

� Q-27 0.24 -0.13, 0.55 0.184 0.316

� Q-28 0.13 -0.24, 0.47 < 0.00001* 2.214

� Q-29 0.41 0.06, 0.67 0.043* 0.316

� Q-30 0.21 -0.16, 0.53 0.0002* 0.883

� Q-31 1.00 0.99, 1.00 1.000 0.0

� Q-32 0.24 -0.13, 0.55 0.0005* 0.883

ǂ Paired t test; *P < 0.05 two-tailed considered a statistically significant; SRM = standardized response mean or responsiveness

Though preferred, PCC often raises debates.

While some have argued that consumers would make wise, cost-conscious, and informed decisions in a free

health care marketplace [11], this metaphor has been criticized for the ‘coexistence in a therapeutic, social, and economic relation of mutual and highly

www.eJM

anag

er.co

m

Survey on patient-centred care

88 Spatula DD

interwoven prerogatives’ [12]. Better option is to leave ‘patients and physicians meeting as equals, bringing different knowledge, needs, concerns, and gravitational pull, but neither claiming a position of centrality’ [12]. This understanding will lead to better health outcomes as healthcare is provided in a way that better meets the needs of patients and doctors as well. Indicators of patient-centeredness relevant to activities, organizations and countries can support the necessary development to promote a balanced healthcare. The generation of evidence and examples of good practice can enable a shift in the culture, organization and delivery of healthcare to maximize the benefit.

Finally, patient-centred healthcare should be considered as an integral element of the philosophy of organizations, governments and healthcare providers and is a key part of a cultural shift in the prioritization, organization and delivery of healthcare. Patient involvement in the development of measures of patient-centeredness should be fundamental. The indicators utilized were only preliminary and probable set of standards developed in order for homeopathic practitioners to understand what is important to their patients, with the aim that they practice and provide patient-centred services. These are amendable to further development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Nikhil Saha, Principal in-Charge, MBHMCH for allowing us to carry out the study successfully in his institution. The authors would like to thank Mr. Kohinoor Chakraborty, MA and Dr. Achintya Kumar Datta, MD for doing the English to Bengali translations as well as Dr. Sankar Sengupta, PhD and Mr. Indrajit Mitra, MBA for back translations. Additionally, the authors wish to thank Prof. Malay Mundle, MD, Prof. Satadal Das, MD, and Dr. Mahua Pal, PhD, Mr. Kohinoor Chakraborty, MA for serving on the expert committee and providing input in the final version of the questionnaire. The authors will also remain grateful to Mr. Arunabha Bhowmick for technical supports and to the patients for their participation in the study.

Funding

The authors received no financial support or funding to report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

1. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC); September, 2010. Patient-centred care: improving quality and safety by focusing care on patients and consumers – Discussion paper. Available at: www.safetyandquality.gov.au; accessed December 19, 2013.

2. International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations, 2006. Declaration on Patient-Centred Healthcare. Available at: http://www.patientsorganizations.org; accessed December 19, 2013.

3. Mezzich JE, Miles A, Snaedal J, van Weel C, Botbol M, Salloum I, et al. The fourth Geneva conference on person-centered medicine: articulating person-centered medicine and people-centered public health. The International Journal of Person Centered Medicine 2012; 2(1):1-5.

4. Richardson WR. Patient benefit survey: Liverpool Regional Department of Homeopathic Medicine. British Homoeopathic Journal 2001; 90:158-62.

5. Itamura R, Hosoya R. Homeopathic treatment of Japanese patients with intractable atopic dermatitis. Homeopathy 2003; 92:108-14.

6. Robinson T. Responses to homeopathic treatment in National Health Service general practice. Homeopathy 2006; 95:9-14.

7. Reilly D, Mercer SW, Bikker AP, Harrison T. Outcome related to impact on daily living: preliminary validation of the ORIDL instrument. BMC Health Services Res. 2007; 7:139.

8. Bikker AP, Mercer SW, Reilly D. A plot prospective study on the consultation and relational empathy, patient enablement, and health changes over 12 months in patients going to the Glasgow Homeopathic Hospital. J Altern Complement Med. 2005; 11(4):591-600.

9. Itamura R. Effect of homeopathic treatment of 60 Japanese patients with chronic skin disease. Complement Ther Med. 2007; 15:115-20.

10. Koley M, Saha S, Ghosh S, Mukherjee R, Kundu B, Mondal R, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction in a government homeopathic hospital in India. Int J High Dilution Res. 2013; 12 (43):52-61.

11. Berwick DM. What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009; 28(4):555-65.

12. Bardes CL. Defining “Patient-Centered Medicine”. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366(9):782-3.