Structural and Convergent Validity of Intelligence Composites

“A limp with rhythm”: Convergent Choreographies in Black Atlantic time

Transcript of “A limp with rhythm”: Convergent Choreographies in Black Atlantic time

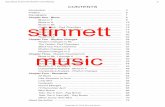

2012 YEARBOOK FOR

TRADITIONAL MUSICVolume 44

SALWA EL-SHAWAN CASTELO-BRANCOBEvERLEY DIAMOND

C. K. SZEGOGuest Editors

DON NILESGeneral Editor

SYDNEY HUTCHINSONBook Reviews

BYRON DUECKAudio Reviews

LISA URKEvICHFilm/video Reviews

BARBARA ALGEWebsite Reviews

Published by theInternatIonal CounCIl for tradItIonal MusIC

under the auspices of theunIted natIons eduCatIonal, sCIentIfIC and Cultural organIzatIon

(unesCo)

Yearbook for Traditional Music 44 (2012)

“A limp with rhythm”: Convergent ChoreogrAphies in BlACk AtlAntiC time

by Sydney Hutchinson

Until at least the 1980s, scholarship on Caribbean carnivals tended to overem-phasize European roots because of the celebration’s ties to the Christian calendar. Meanwhile, scholarship on Caribbean music has long been embroiled in nation-alistic paradigms that have hindered a view of the Caribbean as a cultural region with more commonalities than differences among the music cultures of the various nations (see Bilby 1985). In this paper, I combat these paradigms with the concept of convergence, an alternative to the problematic “syncretism.” It is complemen-tary to current notions of creolization and hybridity, but unlike those concepts, it serves to emphasize the construction of cultural meaning over biological notions of race or ethnicity.

In order to explain how convergence works, I will examine a particular aes-thetic concept—“limping” (adjective cojo, verb cojear are the terms used by my interlocutors)—which is widespread in various forms of music and dance in the northern Cibao region of the Dominican Republic. A “limp” is said to characterize merengue típico rhythms, típico dance, and the lechón (literally “pig”), the princi-pal character in the carnival of the Cibao’s largest city, Santiago. The limp is, how-ever, not only a local stylistic feature, but one that connects Cibaeño culture with other “limps” around the Caribbean region, including US cultural expressions from blues rhythms to zydeco dancing to the “pimp walk.” Although “limping devils” also appear in European folklore, the connective tissue between all these diverse cultural expressions is more likely Eshu, Elegua, or Papa Legba, some of the vari-ous names used for the Yoruba/Fon limping deity of the crossroads who converged with the European devil and is invoked at the beginning and end of Afro-Caribbean religious ceremonies. My examination of these convergent choreographies empha-sizes the force of the multiple meanings these movements and rhythms have had around the region.

Kinetic and sonic aspects of merengue típico and carnival provide deeper com-mentary on the activities being performed, their history, and their current mean-ings. Eduard Glissant wrote, “for us [Caribbeans], music, gesture, dance are forms of communication, just as important as the gift of speech,” and so Paul Gilroy sug-gests that we turn away from textuality and narrative and towards kinesics, drama-turgy, and gesture to better understand diasporic performance traditions (cited in Gilroy 1993:75). In this article, I will do just that. I utilize data collected through interviews with merengue típico musicians and dancers, and four years’ participa-tion in Santiago carnival to analyse the multiple meanings of the limp, explore Black Atlantic expressions in a Dominican context, and explain the relationship between dance and music from a Cibaeño perspective. This interpretation is my own, rather than my interlocutors; nonetheless, this case study of convergent cho-

88 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

reography in the Caribbean will illustrate the kinds of interlaced connections that have long existed between numerous Black Atlantic artistic expressions, providing an updated framework for analysing both content and meaning.

Carnival and merengue típico, expressions of Cibaeño identity

Merengue típico is an important, even central, feature of Cibaeño identity in the Dominican Republic. Its rhythms, repertoire, movements, and instruments distin-guish it from merengues found in other parts of the country and the Caribbean. Similarly, particular masked characters are emblematic of particular parts of the Cibao: the lechón or “pig” of Santiago, the Cibao’s largest city, and the diablo cojuelo or “limping devil” of nearby La Vega1 (figures 1 and 2).2 And while schol-ars have thus far written almost exclusively about the masks and costumes of these

1. Oddly, the Vegan “limping devil” does not actually limp. Its name is now used to create spurious European origins for the carnival. Thus, I will not discuss its movements (mainly a vigorous hopping) here. 2. While each local carnival includes multiple costumed characters, most are found in many or most of the country’s carnivals rather than being linked with one particular place. Only the masked devil-like characters have this characteristic, and indeed they are usually the only characters in masks. Each local carnival has a masked character of its own, and most of these have their own name, from the lechones of Santiago to the cachúas (so named for the horns or cachos on their masks) of Cabral or the toros (bulls) of Montecristi; all could (argu-ably) be interpreted as devils. To my knowledge, none of the unmasked characters limp.

Figure 1. lechones from Santiago (author is third from right), 2006 (photo: Sydney Hutchinson).

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 89

characters, those who wear them emphasize that rhythmic movements are also key features of both the characters and their local identities.

While studying carnival and merengue comparatively would seem strange to many Dominicans, who consider them separate realms, it makes sense to do so not only because they are practised in the same places and sometimes even by the same people, but also because the two are unified by a set of aesthetic preferences—a style—manifest in both music and movement. Movement style has also been iden-tified by literary critic Antonio Benítez-Rojo as a key feature of Caribbean culture. He writes that many Caribbeans make an effort to walk with style, or to walk “in a certain kind of way.” By this expression, he means a way that connects rhythm with bodily movement and sensation (1996:20). Likewise, Máximo Zapata, the presi-dent of a Santiago carnival organization (MOSACA), told me, “We [Cibaeños] have a different way of doing things … a way of seeing things and presenting things” (2009). Máximo saw that difference in the “style” of carnival movement and music in Santiago, seemingly echoing Benítez-Rojo’s theory of Caribbean rhythm as a “metarhythm” that can come through any system of signs, even those as pedestrian as walking (1996:18).3

According to Gilroy’s suggestion, it is imperative that carnival masks and cos-tumes be examined in their performance context, one in which sound and move-ment are of central importance. Connections between sound and motion can best be understood through doing, and thus it was through participation in both merengue music and carnival movement that I noted stylistic links between the two expres-

3. Pun intended.

Figure 2. diablo cojuelo from La Vega. 2006 (photo: Sydney Hutchinson).

90 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

sions. As Benítez-Rojo and Zapata both imply, rhythm and movement are here related through motifs that are not only aesthetically valued but also meaningful.

the limp as a Cibaeño aesthetic feature

Here I focus on just one Cibaeño and Caribbean kineto-rhythmic motif, the so-called “limp” or cojo. Over the course of ten years of research in new York and the Dominican Republic, I have found the limp mentioned repeatedly as an important feature of merengue típico dance, carnival movement, and even merengue típico rhythm. Here I outline the appearance and function of the limp in each of these contexts.

The limp in merengue típico dancing

The first place I encountered the limp was in merengue típico dancing, where it is considered a defining feature of the style, one that distinguishes it from the nation-ally and internationally popular merengue de orquesta (big-band merengue). I probably first heard of the limp during the many nights I spent dancing to merengue típico in Brooklyn, new York, between 2001 and 2003, learning the style by fol-lowing the movements of partners who were nearly all immigrants from the Cibao.

Because I took no field notes at the time, I can only reconstruct my limping initiation through memory traces. The movement is associated in my mind with a tiny club called El Rinconcito de nagua that used to be on Jamaica Avenue in Woodhaven, Queens, just over the border from East new York, and which featured live merengue típico every weekend. For the follower, it consists of altering the usual even merengue walking movement by adding a deeper knee bend on the right side, accompanied by a slight scooping of the hip, the rib cage moving in opposi-tion. This bending intensifies the movement and deepens its relation to the music by accentuating downbeats and creating a wave-like, rolling feeling between the scoop on count one and the lift on count two. It can be done to the side or in a tight circle, and may be exaggerated in the depth of the knee bend and the motion of the hip, but is generally quite subtle. It seemed to me that it occurred more often during the second section of merengues, the mambo (today) or jaleo (formerly) sec-tion when the rhythmic drive and groove is intensified through riff-based playing, improvisation, and, sometimes, call-and-response singing. When I took videos of típico dancing later on, I found that it was difficult to identify the limp visually, but I always know it when I feel it.

The limp was certainly already a feature of the dance by the 1940s, as a popular merengue written by Cibaeño composer Luis Alberti in 1943 and called “El jincao” (very roughly, “the one with the deep knee bends”) testifies.

no te apures más muchacha Don’t worry any more, girlsi cojeo al merenguear. If I limp when I dance merengue.Si este paso no te agrada If you don’t like this stepte lo voy a apambichar … I’ll dance apambichao…(Alberti 1983:258)

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 91

These lyrics connect the limping step to rhythm, and particularly to merengue apambichao or the new, more syncopated pambiche rhythm that appeared in the 1910s and is now considered central to merengue típico; it is played comparatively infrequently by orquestas (bands that play the popular, but contrasting, style of merengue de orquesta).4

nonetheless, musicians and fans alike seemed to agree that the limp was not always present, and they frequently told a similar story to explain how it entered merengue típico. I believe it was first whispered into my ear in El Rinconcito de nagua as one of my dancing partners took it upon himself to reveal the myster-ies of the dance to me. While it sounded apocryphal, the story seemed important both because of the frequency with which it came up, and because of the way it was used to rhetorically tie the limp to other important features and characters in merengue history. For instance, accordionist Arsenio de la Rosa told this version, imparting additional legitimacy by tying it to his grandmother, Merceditas Lora, first cousin to Ñico Lora, a foundational accordionist and folk hero to merengue típico enthusiasts:

I asked her … “How did they dance merengue back then?” So she told me that merengue was not danced limping [in those days] … I asked her why. She told me the reason was that in the time of what they called the bolos and rabuses—they were two political parties, we’re talking about before Trujillo’s time—they used to fight a lot and there were wars in the countryside, in the mountains. My grandmother told me that … in a party where [Ñico] was playing, some soldiers came from the battles … and one had been shot in the leg. They said he was a general [but he could have been any rank] … He came bandaged up, but when he was passing by he heard the tambora [drum] … and said, “no, no, I’m going to dance” …

The so-called general … had a wounded leg, so every time he danced, his leg was limping, but he did it to the rhythm of the tambora and the güira [scraper], right? So … those who didn’t know what was wrong with him said, “Ah, well, this guy dances really well. That’s how we have to dance.” So the limp went with the rhythm … They noticed that when they limped they carried the rhythm better. So, according to my grandmother, that was when they started to dance the merengue with a limp. (de la Rosa 2006)

Arsenio thus dates the appearance of the limp to before 1930. Like Alberti, Arsenio also emphasizes the limp’s connection to the rhythm of the tambora, and he included this anecdote in a merengue he wrote called “Historia Dominicana”:

en tiempos de revolución In revolutionary timescuando Ñico iba a tocar When Ñico was going to playlos guardias se hacían enfermos The soldiers would play sickpero ellos podían bailar But they could danceotros jugaban lechuzas Others “played owls” [i.e., skipped out]pero era para ir a gozar. But only to go out and have fun.un general que llegó A general who camea una fiesta en el Cibao To a party in the Cibao

4. Today, most people do not distinguish between pambiche and merengue in their dancing.

92 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

bailaba el merengue cojo Danced merengue with a limpporque tenía un pie baleao. Because his foot had been shot.

Other sources concur with the assertion that the merengue was once danced without a limp,5 but disagree on the source of the change. For instance, Ñico’s son Antonio Lora, who was seventy years old when interviewed in 1981, stated that when he was a boy merengue was “serene and without figures, without sudden movements or limping. Then the [merengue] apambichao and the spasms arrived” (Brusiloff 1981:28). Lora’s use of “spasm” reflects his low opinion of the new form of dance, whose “sudden movements” may have articulated certain rhythms or added excitement. He refers specifically to the pambiche, a highly syncopated rhythm that is one of the bases of merengue típico. The same article quotes the well-known Cibaeño dancer and folklore enthusiast Tin Pichardo, who explained:

When the Americans arrived [in 1916], they brought their music—the “one-step”—and already in 1918 the girls in the countryside said, “Let’s dance Yankee style” … Merengue today is [thus] a gringo style. But it’s a gringo style that was reformed with the emergence of the pambiche [rhythm] around 1926, when the dance was brought from Dajabón, with the influence of Haitian rhythm, with the movement of the waist and the rear end.

Like the de la Rosas, Tin also dates the appearance of the limp to the 1920s. But Tin’s testimony is significant because it directly contradicts the usual pambiche origin myth. This myth states that the pambiche emerged because the American occupying forces were unable to dance to the faster merengue, and that it takes its name from the “Palm Beach” fabric they wore. However, Tin specifically ties the modern way of dancing merengue to the pambiche rhythm, and the pambiche to the Haitian border area. For him, both the rhythm and the way it is danced derive from Haitian precursors: it was the merengue dance style—not the pambiche—that derived from north American dances. Elsewhere, I have demonstrated that the pambiche rhythm was seen as a Haitian or at least a border import at the time of its emergence in the Dominican Republic (Hutchinson 2008), so Tin’s story is far more persuasive than the other.

The story of the “general” further loses credibility as historical fact when one notes its similarities to other choreographic origin myths in the Caribbean region. For instance, a nearly identical story appears just across the water in Louisiana to explain a limping step in the “Cajun jitterbug” dance. Dance instructors Plater, Speyer, and Speyer write, “According to one account, a man with his leg in a cast came to a dance in Cajun country, and everyone started to copy his limp” (1993:37). And the Urban Dictionary website offers a similar explanation of the African American walking style sometimes termed the “pimp limp”:

Once upon a time there was a pimp and one day he got in a skirmish with a local cop and while he was running away he got shot in the leg and had to walk with a limp.

5. Indeed, even today some merengueros do not know or dance the step. They are some-times described as “elegant” or “classic” dancers.

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 93

now the pimp was limping around with a cane keeping up with his hoes [sic]. Every other pimp liked it and copy ed [sic] him and that’s why pimps walk with a limp. (FRenchPorker 2009)

nonetheless, the story of the general still has some important information to impart. First, it rhetorically ties the limping dance style to (white) folk hero Ñico Lora, thus legitimizing it as a part of Dominican and Cibaeño culture and history. This would have been an important rhetorical move in the time of Rafael Trujillo (in power, 1930–61), when the racism against Haitians, which already had a long history in the Dominican Republic, reached dangerous heights and led to an infa-mous massacre on the border in 1937.

Second, it dates the limp to before Trujillo’s time, and thus to a time of rural liv-ing thought to be simpler and more genuinely Dominican. Finally, since the time of Trujillo, a military man has been someone to respect, but also someone to fear, and thus stories about limping generals at Dominican dances may be related to dancing devil stories that appear in other parts of Latin America during times of conflict. For instance, Lise Waxer writes that when the dance scene in Cali, Colombia, was declining in the 1980s due to drug-related violence, stories began to circulate about the devil appearing in nightclubs (2002:107). Similarly, José Limón has written about devils dancing in south Texas nightclubs in the 1970s, explaining them as a “critical reaction to an increasing saturation from the ‘outside’ by an intensifying culture of post-modernity”—in particular, the clash of Mexican-American tradition with Euro-American modernity, as well as between modern Latina womanhood and old-school patriarchy encapsulated in the dance clubs (1994:180). The limping general also appears at a critical juncture: the clash of Dominican tradition with US modernity and proto-imperialism. I return to the idea of the general as a devil and to the limping pimp further below.

The limp in carnival dancing

While participating in a Santiago carnival group during four carnival seasons (2006–9), I interviewed a number of fellow lechones (pl. of lechón) about the car-nival and, particularly, about the lechón’s movements. lechones themselves turned my attention to this feature of the celebration by describing their dance movements as a distinguishing characteristic of Santiago carnival.

When I presented my carnival research in a talk in Santiago, some local folk-lorists strongly objected to my use of the term “dance.” However, it was the term lechones themselves often used when speaking to me and when teaching me how to move through the streets in my heavy costume. In the past, this factor was even used to judge lechones and award prizes. Long-time carnival aficionado Manuel Ulises Bonnelly (2009) explained that during his time organizing carnival in the 1970s, lechones were judged not only on their costumes but also on “if they knew how to do the little dance” and use the whip.

The lechón “dances” to any music that happens to be playing, or even to no music at all, performing a variety of movements. Máximo Zapata, president of local carnival organization MOSACA, noted that the character hops, jumps, walks,

94 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

and moves through space, and explained that, to do these movements, “he doesn’t even need music, because he has his own structural dance within the character.” He continued:

Here people don’t understand that the lechón has … its own structure, because it has its dance, because it has its cadence, it has its music … The only place you will find the devil moving with grace, with style, is in Santiago. Because it has a structure of how to move: forward, back, to the side, turn around, so they see him, the nobility. He presents himself before he cracks the whip. (Zapata 2009)

As in the discussions of merengue típico dancing, here movement is again clearly tied to music. In this case, the linkage is even more striking because lechones say that no music at all accompanied their antics in the past. The only sounds were the chants children shouted after them, or the sounds they made themselves with their whips and the bells on their costume. Thus, the lechón’s movement is its music—it makes its own sound, both acoustically and visually.

Once again, the most discussed feature of the lechón’s movement was his limp. And again, this fact is striking because the limping motion is hardly perceptible to observers, if they are able to detect it at all. A lechón may experience the limp as a very slight unevenness to the gait that imparts a swagger to his (or, less commonly, her) ambulations.

lechón José Reyes explained that the limp marks the lechón as a devil, because it is the result of the devil’s fall from heaven (Reyes 2006–9) (this explanation is a frequent one worldwide for the devil’s limp; see Pedrosa 2001:74). Máximo’s colleague Carlos Batista also singled out the limp as an important feature, but told a different story about it:

Tradition says that the limping devil was a little devil who tried God’s patience and God sent him to hell, but the little devil was so irritating that the Devil would not accept him either, and he sent him to earth … The little devil went from roof to roof, lifting the tin sheets to see what people were doing, to take people’s lives. And he fell into one of them and was lamed. (Batista 2009)

These stories are significant because they show participants believe the lechón is a devil, even though the mask does not look like either a devil or the pig it pur-ports to represent.6 In addition, Carlos’s version seems to be a retelling of el diablo cojuelo, the popular 1641 novel by Luis Vélez de Guevara (2004), and the French le diable boiteux by Alain-René Lesage (1707; repub. 2001), both of which recount a very similar tale. In this case, the story of the mischievous devil is Dominicanized with the detail of the tin roof.

Carlos Batista further described the traditional lechón dance as “a rhythmic jump” and noted that the limp also served a more practical purpose:

The lechón acted like he was lame so they would feel sorry for him, “oh, he’s lame,” and they wouldn’t send him away … [So then] he could grab people and hit them

6. Various theories account for the character’s name. A more plausible one contends it may be due to carnival participants’ formerly “dirty” or undesirable reputations.

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 95

with the bladder.7 Because if you thought he was fine and you didn’t want him to hit you, you’d send him away; he’d leave. But if you saw him kind of limping, “no, this one won’t get me, this one won’t hit me,” and then the lechón would come along—pow!—and hit you. (Batista 2009)

As in merengue típico dancing, lechones also describe the limp’s connection to rhythm, its “cadence,” as significant. To borrow Benítez-Rojo’s expression (1996:20), we might call it “limping in a certain way.” As Carlos stated in an inter-view, “It has a style, because it’s not a typical limp. It’s a limp with rhythm … a show-off limp.” When I mentioned the limp in merengue típico dancing, Carlos concurred that there could be a relation between these two forms of movement, both considered typically Cibaeño. The relation is not a rhetorical one, since it is never made verbally, but a physical one, where a certain bodily habitus is mani-fested in both expressions.

The limp in merengue típico music

Only recently did I become aware that the limp is also expressed sonically in merengue típico: it emerges in the music as well as the dance. This connection was described to me principally by a conguero típico (conga player). Although the conga entered the típico ensemble comparatively recently, in the 1960s–70s, the way its rhythm fits into the larger pattern created with the tambora drum and güira scraper seems to draw from folk sources like Afro-Dominican palos drumming.

José Blanco (figure 3) has played conga with my own accordion teacher, Rafaelito Román, for many years, but he actually started his musical career playing

7. lechones carry an inflated animal bladder or vejiga, which is used to hit passers-by.

Figure 3. José Blanco, conguero. 2010 (photo: Sydney Hutchinson).

96 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

Figure 4a. Key to the symbols used in tambora drum notation. Adapted from Pablo Peña. noteheads above the line

indicate those played by the right hand, noteheads below the line indicate those

played by the left hand.

Figure 5. Merengue típico rhythm on conga and tambora: the “limping rhythm” or ritmo cojo (source: José Blanco).

conga

Tambora

Basic ritmo cojo

Left hand slap

Left hand open tone

Right hand stick on drum head

Right hand stick on rim

Tambora key:

Open tone, left hand

Slap, left hand

Open tone, right hand

conga key:

Figure 4b. Key to the symbols used in conga drum notation.

with orquestas. Probably precisely because the conga entered the merengue típico ensemble comparatively recently, and because of his prior experience in a different genre, José had thought carefully about how the rhythm of his instrument fit into the larger pattern created with the tambora and güira.

He explained to me in an interview (Blanco 2010) that the rhythm congueros in popular merengue big bands (orquestas) play is similar to that of salsa, but that the rhythm of merengue típico is different because it has a golpe cojo, a limping beat. He played both versions together with tambora to demonstrate (figures 4 and 5). He also stated that the limp is found in the tambora when it plays the pambiche—which, as we earlier saw, is a rhythm with Haitian roots. In fact, after initially play-ing the rhythm orquesta style, he found the limp was the key to lining the conga up with the tambora in típico: “I didn’t know the swing, I didn’t know about the little space, that limp … I had a different swing. I would play típico, but I would come out a beat behind.” The solution, Román told him, was in the limp. When José dem-onstrated the rhythm for me at full speed in combination with the tambora player, the tamborero commented, “that’ll make them dance!”

Thus, both musicians tied the rhythm to danceability, and in fact throughout the interview José singled out movement as an important aspect of playing the rhythm. When I asked for elaboration, he used a kinetic metaphor: “When you put on a pair of shoes, and one is flat and the other has a heel, when you put one down, the other

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 97

goes like this, right?” He demonstrated an uneven gait and then put it in musical terms. “It has a little contratiempo, like an off-beat syncopation, which you have to play in order to complete [the rhythm] with the tambora.” Later, he continued, “the right [hand] is falling and [the left hand is] left up.” And when he played the rhythms for my video camera, again he signalled the difference was in “the position of the hands.”

I then asked José outright if there could be a connection between the limping rhythm and the limp in merengue típico dance. He replied, “It’s possible that there could be, because the tambora also has it.” The young tamborero who had been helping José demonstrate the rhythms played the basic pambiche rhythm to dem-onstrate (figure 6). José then added that the guinchao rhythm in the tambora (figure 7) also has a limp, and that it was related to the carabiné, a folk dance from the southwestern part of the country that is believed to have come from Haiti.

In sum, this discussion showed that some musicians perceive a limp in all típico percussion parts; that this limping rhythm distinguishes típico from other, related genres; and that the limp is particularly noticeable in the pambiche and guinchao rhythms, which, I have noted, are linked to Haitian sources. Furthermore, Blanco and his companion thought of the limp in terms of movement: not only did they feel that the hand motions required to play the rhythm were distinctive, but they also tied this rhythmic motion to “swing” and dance.

the limp as an Afro-Caribbean aesthetic feature

In Santiago, then, the limp appears in both music and movement, often connect-ing the one to the other, and it is frequently seen as a significant feature of local or Cibaeño identity. However, the limp as a rhythmic and kinetic motif is not restricted to the Cibao; it actually appears throughout the Caribbean. I believe that these limps are meaningful and connected, and that, while limping devils also appear in European folklore, the link between them in the Caribbean is more likely the figure variously termed Eshu, Elegua, Elegba, Legba, or Papa LaBas (with numerous variant spellings).8 In Yoruba and Fon cultures and their new World descendants,

8. Already complicated enough, this character assumes even more forms than this list sug-

Figure 7. Guinchao rhythm on tambora for merengue típico (source: Rafaelito Román).

Figure 6. Pambiche rhythm on tambora for merengue típico (source: Rafaelito Román).

R

98 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

Elegua9 is the mediator between gods and humans, symbolizing the liminal state of being between worlds or categories. He deals with transformations, opposites, magic, dance, and sex. He is a trickster, and like any trickster he is ambivalent, but serves to unite or mediate opposites. His symbols include the phallus, horns, the cross, and crossroads. He also limps.

Gates explains, “In Yoruba mythology, Esu [variant spelling of Eshu] is said to limp as he walks precisely because of his mediating function: his legs are of dif-ferent lengths because he keeps one anchored in the realm of the gods while the other rests in this, our human world” (1988:6). In the new World, he became even more important, and no wonder, since he is linked to transitions and heterogeneity (Mackey 1987). There, he maintains an important role in Afro-American religions of Cuba, Brazil, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic: in most such ceremonies, he is the first loa (lwa, luá) or spirit invoked since he is the one who opens ways. Those who are possessed or mounted by this loa or misterio—the Haitian and Dominican terms, respectively, for such deities or life forces—may find themselves bent over and moving with a pronounced limp (e.g., Pedrosa 2001:74).

Legba (the Fon name corresponding to the Yoruba Eshu) is certainly known in the Dominican Republic. Folklorist Fradique Lizardo reports that there is an entire division of Dominican loas called the “Legba division,” which includes the most ancient and wise deities. The chief of the division—and indeed of all twenty-one divisions of Dominican practice—is Papa Legba, the opener of paths who Lizardo says is syncretized with St. Anthony of Padua (1982:14–15); in ceremonies, he manifests himself as an old man with a cane (ibid.:22). Interestingly, the more potent features of the African Eshu seem to have been transferred to a different, wholly Dominican loa: Belié Belcán, syncretized with St. Michael, who is known as a lover and who limps because he has one goat’s foot, according to Lizardo (ibid.:23, 28); he is also the favourite saint of palos drummers (Payano 2003:415). Other sources, however, say he limps because of a wound received in battle, calling to mind the stories of the limping general (Gade nou Leve Society 2005–9).

Some Dominican practitioners seem to remember Elegua’s name, but not his stories. Payano quotes Bartola Colón, a folk poet who grew up near the Haitian border, reciting a poem she termed “plena” with a refrain, “Asilié, ay asilié / Asilié ay papa lewa.” The poet did not know the meaning of “papa lewa,” although it should now be clear to readers—significantly, the opening of the verse calls to “St. Michael with the cross,” recalling the limping Belié Belcán in connection with another of Elegua’s symbols,10 and the singer herself said “Asilié” was a kreyol

gests. In Haiti, Papa Legba is also related to Baron Carrefour (Baron of the Highway (or Crossroads)) and Papa Guédé, also important in the Dominican Republic. In both coun-tries, Legba deals with life and Guédé with death, while in some Dominican ceremonies, El Barón del Cementerio (the Baron of the Cemetery), a local guédé is the first misterio (spirit). (Guédé is also the name of a family of spirits.) It has also been suggested that the Barón del Cementerio is manifested in carnival through Califé, the leader of the carnival parade in the capital city. 9. Here I will use the name Elegua for convenience, although it could as easily be exchanged for any of the others as I will not distinguish between them. 10. Payano offers another gloss: he believes the word is a transformation of papa-loa, or a

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 99

word for the Holy Spirit (Payano 2003:394–96). In addition, when I was learning to play palos drums with Grupo Mello, a Santiago-based group originally from Las Matas de Farfán, a part of the southwest known for its Afro-Dominican religious practices, its members told me that one always has to play a piece for “Leyva” first—although they could or would not explain why.

While Dominicans might find it surprising that Elegua should live on in some of their most cherished identity symbols, it may not be a surprise for scholars. His appearances in African American arts are well known: Mackey notes that he appears in concrete form in the work of Zora neale Hurston, metaphorically in that of other writers like Raymond Williams and Ralph Ellison, and even in the characteristic syncopations—unevennesses—of African American music (Mackey 1987). In folklore, as we shall see, there are numerous stories from all around the Caribbean about those who have encountered the “devil” at the crossroads. It is not surprising, then, that this god of dance should appear in regional dance practices.

If syncopations and swing eighths can be manifestations of this being, then surely so can the limping rhythms of merengue típico, particularly when musicians sometimes describe them in just such terms. Many Dominicans grow up partici-pating in religious ceremonies where limping misterios (the Dominican term for the spirits called loa or lwa in Haitian vodou) may manifest, dancing to merengue típico, and in other ways internalizing the rhythms of merengue and carnival. If the body has a memory of its own—muscle memory—then it is understandable that Elegua can be echoed through the repetition of movements and rhythms across these seemingly unrelated genres, although cultural features like stories and belief systems may be required to activate the memories.

Most salient of all for this discussion, however, is the case of the lechón, whose similarities with Eshu-Elegba are multiple. Often, the lechón and the loa or miste-rios (Afro-Haitian and Afro-Dominican spirits, respectively) serve the same func-tion. Just as Elegua deals with transitions and is thus invoked at the beginning of every ceremony, so was the lechón or diablo used to the open way for carnival. Folklorist Tomás Morel wrote, “The first lechones emerged as keepers of order in the old Santiago carnival. They went ahead of the comparsas [themed carnival groups], herding them, in order to make way among the multitudes and to impede the children’s mischief” (Morel 1994). Like Elegua, the lechón’s function was to create a border zone between the audience and the masqueraders and thus to medi-ate the transition between everyday time and festive time. The lechón opened the way for carnival just as Elegua opens the way to the spirit world.

In addition, the lechón is a trickster like Elegua. Carlos made the lechón’s trick-ster function clear by noting that the limp may be used to throw off spectators and thus take them by surprise. The “show-off” aspect of his movements, as well as the sharp contrasts between stillness, graceful motion, and abrupt jumps, are also characteristics of the trickster. When Santiagueros, or residents of Santiago, talk about what makes a “good lechón,” more often than not they speak of the ability to use the whip to fearful effect as well as to provoke laughter with their dance

vodou priest. I think it is more likely an alternate pronunciation of Papa Legba.

100 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

moves. Some “good lechones” even imitate hypersexualized popular styles like reggaetón to achieve this result, echoing Elegua’s potency. As a trickster, Legba (= Elegua) is “a symbol of the liminal state itself” (Pelton 1980:35), and, by walking the boundaries between the carnival space of masqueraders and the borders occu-pied by spectators, the lechón also deals with the transformative power of masking and carnival’s potential to temporarily subvert social orders.

There are also similarities between the iconographies of Elegua and the lechón. The lechón has exaggerated horns and other potentially phallic symbols, both Elegua attributes. The lechón wears a kind of tubular belt called a morcilla, or sausage; although today the “sausage” does not much look like one, years ago, lechones also hung shorter cylinders or even bananas vertically from this belt (Reyes 2006–9:interview, 27 Jan 2009).

However, Elegua changed in his travels to the new World, and these changes have implications for the meaning of this Caribbean limp. For instance, while he/she was a symbol of sexual potency for the Fon, Papa Legba became a very old man, essentially impotent, in Haiti (Cosentino 1987). In some places, he gained additional importance through the middle passage because of his ties to transi-tions and heterogeneity (Mackey 1987). And just as Elegua himself changed, so is there another, darker dimension to the lechón: his whip. Zairian scholar and priest Pedro Muamba Tujibikile, who lived and worked in the Dominican town of Cabral, hypothesized that the carnival whip represented the punishing slave owner as well as the resisting slave and the slaves’ rage (1993:43). Rosenberg has noted a similar meaning for the whip in gagá, a Haitian-Dominican Holy Week musical tradition (in Haiti, it is called rará) (1979:259); Tejeda Ortiz explains that this whip comes from the Papa Legba of vodou’s Petro rites (1996:65). In Cabral and Montecristi, carnival participants still do what lechones once did, but have since ceased to do: they actually whip each other in a cathartic annual ritual. Finally, compar-sas (themed carnival groups) that literally represent slaves and owners frequently appear in Latin American carnivals. In nineteenth-century cannes brulées celebra-tions and in today’s “Jab Jabs” (from French diables), Trinidadians crack their whips while wearing Pierrot costumes similar to the lechón’s (Liverpool 1988:30). In the nineteenth-century son de los diablos, Afro-Peruvians danced with whips for Corpus Christi; and today, masqueraders in Carriacou use them along with verbal competition. In the Dominican Republic, a comparsa (called Olí-Olí) that depicts slavery and uses whips is still performed in the Samaná peninsula.

The lechón’s whip demonstrates that while Dominican carnival may have arisen from Spanish practices, it has since acquired additional meanings. It and the limp could both be interpreted as kinds of resistance to colonial regimes. For Tujibikile, carnival whipping traditions are a form of liberation, since dancing is an act of con-trol over one’s own body. Irobi adds that “the body has a memory and can be a site of resistance through performance” (2007:901). The limp therefore evokes both the power of Elegua and the suffering of the slave.

As mentioned, the limping Elegua can be found in expressive culture from other parts of the Caribbean. Thomas suggests that “the pimp limp,” seen in hip-hop

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 101

videos worldwide, is also derived from Eshu (=Elegua) (Thomas 2009:68). The movement itself is elsewhere defined as:

not a stiff strut but a relaxed, self-assured, super-cool saunter, performed slowly with a rhythmic, subtle limp, bounce, and drag in the stride … the walk has to be done just right, with a certain cadence and leisurely, measured side-to-side limp and slight hitch and jerk in one’s gait, and with the arms swinging loosely, an upright posture, shoulders and head back, and perhaps even a slight lean backward. (Wojcik 2006:983)

Walking with this stylized limp is a key component of the pimp persona (Quinn 2000:123–24), and the pimp is himself a trickster character in today’s gangsta rap,11 just as he was earlier a “folk hero symbolizing resistance and the dignity of the Bad Man living outside the white man’s rules” (Wojcik 2006:983; see also Quinn 2000:118). He is also explicitly connected with the Signifying Monkey—like Elegua, a verbal trickster—in some African American verbal folklore like folk tales, the dozens, and toasting, Quinn says (ibid.:119).

The limping devil appears alone with no musical component in Afro-Colombian (Pedrosa n.d.), Haitian, and Cuban (Pedrosa 2001:73–74) folklore, including myths, legends, and beliefs. Elsewhere, the devil appears without a limp, but in conjunction with both music and the crossroads, as in the blues or in zydeco tales (Tisserand 1998:43–44). The dancing, masked ireme of the Cuban Abakuá society were once called diablitos as well (Bettelheim 1990:32). Stories about devil-trick-sters appearing in music competition abound, appearing in Colombia (cf. films, los viajes del viento and el acordeón del diablo), the Dominican Republic (Aretz and Ramón y Rivera 1963:204), and Venezuela (ibid.; see also the poem “Florentino y el Diablo,” originally written in 1940, in Arvelo 1999 or the Venezuelan film of the same name). In Cuba, Fernando Ortiz even wrote that the scandalous colonial-era dances zarabanda (sarabande) and chacona (chaconne) were attributed to the limp-ing devil (in Pedrosa 2001:73).

These examples indicate Eshu-Elegua lives on in Caribbean music, particularly through the limp, a pleasing rhythmic unevenness in sound and movement that unites music and dance practice in the region. Although outsiders may have trou-ble even detecting its existence, the importance of this aesthetic feature is clearly noticed and sometimes debated by merengue musicians and dancers as well as carnival participants, who frequently go so far as to come up with origin myths to explain its presence.

Convergent choreographies

Because Elegua is present in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, it is not a stretch to imagine that Dominican dancing devils and limping rhythms also are related to this loa. But the Caribbean limping devil is complicated by the fact that Europe,

11. Similarly, Keyes details how crossroads as places of spiritual power continue to reap-pear in rap today as an extension of Southern black vernacular traditions (2004:27–28).

102 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

too, has its own, similar tradition. I have already noted the similar iconography of Elegua and the devil, which caused the two to be conflated and/or syncretized, and I have mentioned the popular seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European novels featuring limping-devil protagonists. Folk sayings in Spain relate to this character today (Caro Baroja 1998:529), as they did already in the seventeenth cen-tury (Rodríguez Marín 2004). For Europeans, too, the devil can be a hypersexual-ized trickster who dances during carnival time. I have even seen videos of Spanish carnival in which a man danced graphically with a corncob tied around his waist underneath an apron—and in fact, some Dominican devils of yesteryear also wore little aprons (Tejeda Ortiz 2008:100).

Given these similarities, it would be as false to say that the lechón is Elegua or that he is a direct African inheritance as it would be to claim that the merengue and its dance were imported from Spain. What I wish to argue is that the lechón is the result of the same processes that have characterized the majority of religions and musical genres of the Caribbean for centuries, those usually termed syncretism or creolization, and it is therefore probable that he has more than one meaning.12 As Thomas suggests, the limp is “a telltale sign” that “has as much double-meaning as the trickster’s ‘trick’ ” (2009:85). I also mean to suggest that merengue típico and Dominican carnival have certain features that link them to other Caribbean and Afro-Caribbean cultures—and to source materials in Africa, as well as Spain and France.

The similarities in form and function between European and African trickster figures, and the merging of the two in the Caribbean limping devils, make me think again of the merengue and the long-standing debate over its etymology. Multitudes of scholars have argued over whether it is African or European in ori-gin, but Dominican anthropologist José Guerrero has convincingly argued that we must see it as a case of “convergent etymology”: that in the nineteenth century, when merengue music and dance first emerged, the term had one meaning for those of European heritage—a fluffy dessert—and another for those of African herit-age—music or dance (Guerrero 2006:80–81). I would add that it was precisely because of this double meaning that the dance and music became so popular so fast, eventually turning them into powerful symbols of Dominican identity. Here, in this doubleness, we can again see Elegua at work—not a destructive devil, but a mischievous trickster and a generating life force.

I argue that we should similarly see this Caribbean limp as a case of convergent choreography. The limp and the merengue had one meaning for observers with a primarily European cultural background, and another for those with an African cultural background. It is because of its doubleness that the limp is still important in Dominican music and dance today. In fact, its multiple meanings can even provide

12. In Andalucia, Spain, people say that “the point of carnival … is that it erases the borders between people and between things” (Gilmore 1998:18). Who inhabits the borders between things if not Legba? And who inhabits the border between carnival and normal life if not the lechón? One can imagine that in past centuries, people of African descent may have had similar thoughts when seeing the Spanish carnival, and they looked for ways in which to insert their own values, ways of thinking, and dancing into the festivities.

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 103

aesthetic enjoyment. As Ruth Stone writes, for the Kpelle in Liberia, “part of the pleasure of proverbs is that they represent a … variety of connections to be made. And people find that delightful” (2005:15).

In The repeating island, Benítez-Rojo suggests that “supersyncretisms” are a particular feature of Caribbean culture. As an example, he cites the trinity of the Taino deity Atabey, the Spanish Virgin of Illescas, and the African Oshun. The term “syncretization” is not sufficient to describe what happened when these three dei-ties came together, because the “original” gods were themselves syncretic. Thus, he argues, they show us something that is “not ‘original’ but rather ‘originating’ ” (1996:12–13). In the limp, we have an example of a supersyncretism in music and dance, which has given way to a variety of music and dance styles that endure precisely because of their mixtures. Instead of speaking of “syncretism,” though, which may lead us into the traps of devaluing mixture or supposing that “original” forms were more “pure” (Stewart 1999:40–41), I suggest “convergence.” While “hybridity,” “creolization,” and “transculturation” have all been similarly proposed as alternatives, the first two have their own colonial baggage about genetic and cultural “purity,” while none of the three deal adequately with the construction of meaning. The questions that need to be asked are partly about reception (in a situ-ation of culture contact, how does each group interpret the outward manifestations of the other’s culture, including music and dance?) and partly about performance (how is one meaning projected or a new one created in subsequent iterations of these cultural expressions?). Convergence is better able to deal with these ques-tions. It emphasizes process over product as well as the production of shared mean-ing out of complex prior cultural materials, without assuming that these were once “pure.” Convergence, I would argue, can be found in many kinds of Caribbean expressive culture—not only music and dance, but language and the visual arts as well. Bettelheim, for instance, has shown how Jamaican masks like the Horsehead have strong and continuing ties to both African (Malian, in this case) and British precursors (1988:54–55).

Other disciplines also speak of “convergences.” In linguistic convergence, bilin-gual speakers change both languages by adapting features of one language into another—this convergent development “expresses unity, a feeling of shared iden-tity” (Patrick n.d.). Here, a person “fluent” in both Western European and West African mythologies could have similarly chosen to adapt features of the limping devil to Elegua or vice versa, causing enduring changes in performance. Local, Caribbean identities were then formed by performing movements and sounds found in the overlap between cultures. In media studies, Henry Jenkins uses “con-vergence” differently: to describe “the flow of content across multiple media plat-forms … and the migratory behavior of media audiences” (2006:2). While the flows I’m describing occurred long before those he describes, they are similar in that they involve migrating observers and cross multiple “platforms”—in this case, modes of performance (music, dance, ritual, carnival). The technologies are different, but both lead to the crossover of cultural material to other genres, modes, and places.

104 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

Because such exchanges did not take place on equal footing13 in the Caribbean slave economy, Black Atlantic culture came to rely on “syncopated temporality” or “temporal disjunction” (Gilroy 1993:202). The limp itself emphasizes the disjunct nature of Black Atlantic time in both music and movement, as well as the conver-gence of Black Atlantic and Iberian Atlantic forms—both of them always already mixed. As a convergent choreography, the limp acquires layers of meanings in a semantic snowballing effect, rolling together African deities, European devils, and Caribbean suffering into one masterful performance of Black Atlantic history.

Conclusions

If I had not danced merengue típico, played accordion, and become a lechón, I would not have noticed the connections between these forms of expressive cul-ture. This fact demonstrates that dance itself is an important methodology through which one can come to understand the links between peoples and the characteris-tics that distinguish the Caribbean as a cultural region. Beyond that, dance plays an important role in the lives of individuals: it is an opportunity to distinguish oneself and, at the same time, create community cohesion.

Attending to dance and music together can help us to have a more complete pic-ture of Caribbean culture, where the two are usually intertwined. Both the lechón and merengue típico draw on the limp’s multiple meanings to create a meaningful distinctiveness. The limp therefore helps us to see carnival and merengue típico as related practices, related not only to one another but to broader Caribbean aes-thetic concepts. As Paul Austerlitz has suggested, music and dance are as inex-tricably interrelated in the Caribbean as they are in sub-Saharan Africa, so that “Aural rhythms are thus best understood in the context of related body movement” (2003:104). A “hidden” or base rhythm that may not be heard in a literal fashion, like the clave (“key” or timeline) in salsa, may manifest itself instead in dance movement, he states. The uneven limp—so hard to see and hear but so salient to dancers and musicians—may be one such “hidden rhythm” acting as a “key” to aesthetic expression and to Caribbean convergence.

Acknowledgements and epilogue

My carnival research was supported by a nadia and nicholas nahumck Fellowship from the Society for Ethnomusicology. The writing of this article was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation hosted by the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv in the Ethnological Museum, Berlin. Thanks to my host, Lars-Christian Koch; to Paul Austerlitz, Maurice Mengel, and the Yearbook’s reviewers for their comments on this paper; to my accordion teacher Rafaelito Román; and to Los Confraternos de Pueblo nuevo.

13. This pun was actually unintentional.

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 105

I presented an early version of this paper at the International Council for Traditional Music World Conference in St. John’s, newfoundland. Several days later, my husband and I hiked to the fishing village Quidi Vidi and ate chowder in the only open restaurant. At the table next to ours, an Ecuadoran pianist was telling his friends a story that began, “So you know the merengue, and how you dance it like this? Do you know why? Well, there used to be pirates in the Dominican Republic, and one of them had a peg leg …”

reFerenCes Cited

Alberti, Luis 1983 Merengues. Ed. Manuel Marino Miniño Marion-Landais. Santo Domingo:

Editora de Santo Domingo.Aretz, Isabel, and Luis Felipe Ramón y Rivera 1963 “Reseña de un viaje a la República Dominicana.” boletín del instituto de

folklore [Caracas] 4/4:157–204.Arvelo Torrealba, Alberto 1999 obra poética, Caracas: Monte Ávila.Austerlitz, Paul 2003 “Mambo Kings to West African Textiles: A Synesthetic Approach to Black

Atlantic Aesthetics.” In Musical migrations, ed. Francis Aparicio and Cándida Jáquez, 99–116. new York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Batista, Carlos 2009 Interview. Leader of Los Reyes del Mambo lechón group and Movimiento de

Santiago en Carnaval. Santiago. 3 and 19 February.Benítez-Rojo, Antonio 1996 The repeating island: The caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective. 2nd ed.

Trans. James Maraniss. Durham: Duke University Press.Bettelheim, Judith 1988 “Jonkonnu and Other Christmas Masquerades.” In caribbean festival arts:

each and every bit of difference, ed. John W. nunley and Judith Bettelheim, 39–83. Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum and Seattle: University of Washington Press.

1990 “Carnaval in Cuba: Another Chapter in the nationalization of Culture.” caribbean Quarterly 36/3–4: 29–41.

Bilby, Kenneth 1985 “The Caribbean as a Musical Region.” In caribbean contours, ed. Sidney Mintz

and Sally Price, 181–218. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.Blanco, José 2010 Interview. conguero. Santiago. 12 May.Bonnelly, Manuel Ulises 2009 Interview. Carnival enthusiast. Santiago. 18 February.Brusiloff, Carmenchu 1981 “El merengue de ahora: ‘una gringada’ reformada con pambiche.” Hoy 7 (Oct.):

28.Caro Baroja, Julio 1998 “Sobre el diablo cojuelo.” In Miscelánea histórica y etnográfica, ed. A. Carreira

y Carmen Ortiz, 527–32. Madrid: CSIC.

106 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

Cosentino, Donald 1987 “Who Is That Fellow in the Many-Colored Cap? Transformations of Eshu in Old

and new World Mythologies.” Journal of american folklore 100/397: 261–275.de la Rosa, Arsenio 2006 Interview. Accordionist. The Bronx, new York. 7 July.Gade nou Leve Society 2005–9 “Belié Belcán.” international Vodou Society. http://www.ezilikonnen.com/

dominican/belie-belcan.html (accessed 1 June 2011).FRenchPorker 2009 “2. Pimp Limp.” urban dictionary. http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.

php?term=pimp+limp (accessed 21 June 2012).Gates, Henry Louis 1988 The Signifying Monkey: a Theory of african american literary criticism. new

York: Oxford University Press.Gilmore, David D. 1998 carnaval and culture: Sex, Symbol, and Status in Spain. new Haven: Yale

University Press.Gilroy, Paul 1993 The black atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.Guerrero, José 2006 “El merengue: ¿cubano, puertorriqueño, haitiano, o dominicano? La prob-

lemática antropológica de los orígenes.” In el merengue en la cultura dominicana y del caribe, ed. Darío Tejeda and Rafael Emilio Yunén, 69–104. Proceedings of the Primer Congreso de Música, Identidad, y Cultura en el Caribe, Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, 8–10 April 2005. Santiago: Centro León; Santo Domingo: Instituto de Estudios Caribeños.

Hutchinson, Sydney 2008 “Merengue Típico in Transnational Dominican Communities: Gender,

Geography, Migration, and Memory in a Traditional Music.” PhD dissertation, new York University.

Irobi, Esiaba 2007 “What They Came With: Carnival and the Persistence of African Performance

Aesthetics in the Diaspora.” Journal of black Studies 37/6: 896–913.Jenkins, Henry 2006 convergence culture: Where old and new Media collide. new York: nYU

Press.Keyes, Cheryl Lynette 2004 rap Music and Street consciousness. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.Lesage, Alain-René 2001 le diable boiteux. Ed. Pierre Jannet. (Orig. pub. 1707). http://www.gutenberg.

org/ebooks/35019 (accessed 21 June 2012).Limón, José 1994 dancing with the devil: Society and cultural Poetics in Mexican-american

South Texas. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.Liverpool, Hollis 1988 “Origins of Rituals and Customs in the Trinidad Carnival: African or European?”

Tdr 42/3: 24–37.

HUTCHInSOn “A LIMP WITH RHYTHM”: COnVERGEnT CHOREOGRAPHIES 107

Lizardo, Fradique 1982 “Apuntes. Investigación de campo para el montaje del espectáculo religiosidad

popular dominicana, Auditorio de Bellas Artes 15, 16, 17, 18 de abril 1982.” Santo Domingo, República Dominicana: Dirección General de Bellas Artes, Museo del Hombre Dominicano.

Mackey, nathaniel 1987 “Sound and Sentiment, Sound and Symbol.” callalloo 30: 29–54.Morel, Tomás 1994 obras competas. Santiago de los Caballeros: Ayuntamiento de Santiago.Patrick, Peter n.d. “Linguistic Convergence and Divergence, and Acts of Identity.” Course notes for

LG 232 Sociolinguistics, University of Essex, UK. http://courses.essex.ac.uk/lg/lg232/ActsIDcriteria.html (accessed 29 June 2011).

Payano, Héctor 2003 “La décima popular dominicana: Recopilación, clasificación y análisis de sus

recursos más sobresalientes.” PhD dissertation, City University of new York.Pedrosa, José Manuel 2001 “El diablo cojuelo en América y Africa; de las mitologías nativas a Rubén Darío,

nicolás Guillén y Miguel Littin.” Revista de filología e letterature ispanische 4: 69–84.

n.d. “Leyendas de Timbiqui (Cauca, Colombia): Etnotextos y estudio comparativo.” revista de folklore [Fundación Joaquín Díaz] 21a/245: 168–175. http://www.funjdiaz.net/folklore/07ficha.cfm?id=1946 (accessed 1 June 2011)

Pelton, Robert D 1980 The Trickster in West africa: a Study of Mythic irony and Sacred delight.

Berkeley: University of California Press.Plater, Ormonde, Cynthia Speyrer, and Rand Speyrer 1993 cajun dancing. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company.Quinn, Eithne 2000 “ ‘Who’s the Mack?’ The Performativity and Politics of the Pimp Figure in

Gangsta Rap.” Journal of american Studies 34: 115–36.Reyes, José 2006–9 Conversations and interviews. Individual lechón. Santiago.Rodríguez Marín, Francisco 2004 Prologue and notes to el diablo cojuelo by Luis Vélez de Guevara. (Orig. pub.

1922). http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12457/12457-h/12457-h.htm (accessed 21 June 2012).

Rosenberg, June C. 1979 el gagá: religión y sociedad de un culto dominicano; un estudio comparativo.

Santo Domingo: Editora de la UASD.Stewart, Charles 1999 “Syncretism and Its Synonyms: Reflections on Cultural Mixture.” diacritics

29/3: 40–62.Stone, Ruth 2005 Music in West africa: experiencing Music, expressing culture. new York:

Oxford University Press.Tejeda Ortiz, Dagoberto 1996 cultura popular e identidad nacional. Santo Domingo, República Dominicana:

Consejo Presidencial de Cultura, Instituto Dominicano de Folklore.

108 2012 Yearbook for TradiTional MuSic

2008 el carnaval dominicano. antecedentes, tendencias y perspectivas. Santo Domingo, República Dominicana: Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia Sección nacional de Dominicana.

Thomas, Greg 2009 Hip-hop revolution in the flesh: Power, knowledge, and Pleasure in lil’ kim’s

lyricism. Palgrave Macmillan.Tisserand, Michael 1998 The kingdom of Zydeco. new York: Arcade Publishing.Tujibikile, Pedro Muamba 1993 las cachúas: revelación de una historia encubierta. Santo Domingo: Ediciones

CEPAE.Vélez de Guevara, Luis 2004 el diablo cojuelo. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. (Orig. pub.

1641). http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/el-diablo-cojuelo--0/ (accessed 21 June 2012)

Waxer, Lise A. 2002 The city of Musical Memory: Salsa, record Grooves, and Popular culture in

cali, colombia. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.Wojcik, Daniel 2006 “Pimp Walk.” In Greenwood encyclopedia of african american folklore, ed.

Anand Prahlad, 983–84. Westport: Greenwood Press.Zapata, Máximo 2009 Interview. President of Movimiento de Santiago en Carnaval. Santiago. 19

February.

Abstract in spanish

El concepto de “cojear” está muy extendido en diversos géneros de música y de baile en la región norteña de la República Dominicana denominada el Cibao. Se dice que el “cojo” caracteriza la forma en que el acordeón y los instrumentos de percusión interpretan los ritmos del merengue típico, y algunos lo consideran una característica que distingue el es-tilo típico cibaeño del merengue de los merengues de otras regiones el país. El merengue típico tradicional también se bailaba “cojeando.” Por otra parte, los personajes típicos del carnaval cibaeño en las ciudades de Santiago y La Vega también avanzan, según se dice, con un “cojo.” Músicos, bailarines, y carnavaleros dan varias explicaciones verbales sobre la historia y la importancia del cojo, y muchas se lo atan a historias sobre diablos y otros personajes amorales.

Sin embargo, el cojo no es solamente una característica estilística local, sino una que conecta la cultura cibaeña con otras expresiones del “cojo” en toda la región caribeña, desde los ritmos blues hasta el baile del zydeco y el “pimp walk.” El tejido conectivo entre todas estas diversas expresiones culturales podría ser Esu, Eleguá, o Papa Legba, el dios de las encrucijadas que cojea, que a veces se sincretiza con el diablo cristiano, y a quien se invoca al comienzo y al final de las ceremonias de vudú y de la santería. El presente artículo utiliza los datos recogidos a través de entrevistas con músicos y bailarines del merengue típico, cuatro años de participación en el carnaval santiaguero, y las teorías de Henry Louis Gates y Paul Gilroy para explorar las expresiones del Atlántico negro en un contexto dominicano, mientras explique las conexiones entre la danza y la música desde una perspectiva cibaeña.