A Day in the Life": An International Study of Two-Year-Old Girls and Their Families

Transcript of A Day in the Life": An International Study of Two-Year-Old Girls and Their Families

"A Day in the Life": An International Study of Two-Year-Old

Girls and Their Families

Julia Gilleni, Catherine Ann Cameronii, Giuliana Pintoiii, Beatrice Accorti Gamannossiiii,

Susan Youngiv and Roger Hancockv.

i Lancaster University, UK ii University of British Columbia, University of New Brunswick and University of Victoria,

Canada iii University of Florence, Italy iv Exeter University, UK v Open University, UK

Paper presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting:

Understanding complex ecologies in a changing world, Denver. April 30 – May 5

Abstract

This paper presents a synthesis of findings from an international project studying the

moment-by-moment mutual adaptation of two-year-old girls and their families engaged in

everyday activities (Gillen & Cameron, 2010). This sociocultural study has involved a

multidisciplinary team studying seven children in family settings in Canada, Italy, Peru,

Thailand, Turkey, UK and USA. We sought to identify diverse ways of thriving, through an

interpretive methodology with the videoing of a 'day in the life' of each child and her

interactions with the environment, including caregivers, at the core. Our methodology

involved dialogues with the families and between researchers. In this presentation we

demonstrate findings from the Italian day, to illustrate activities that we have observed

common to all settings. We do this through the presentation of three vignettes selected to

illustrate our interpretive approach, our investigations into what might be considered

innovative developmental domains such as musicality and which lead us towards an

interactional perspective on multimodality. Our glimpses into the children’s domestic

worlds support a generally bidirectional view of socialisation (Pontecorvo, Fasulo, &

Sterponi, 2001), as children and adults reciprocally co-construct their lives. Close

examination of (relatively) naturalistic data has assisted the analysis of this element of the

ecocultural framework within which these children and adults mutually adapt their diverse

needs and intentions.

2

Purpose

This paper presents a synthesis of findings from an ongoing international project studying

the everyday living and learning of two-year-old girls in family settings. This sociocultural

study has involved a multidisciplinary team studying seven children in family contexts in

Canada, Italy, Peru, Thailand, Turkey, UK and USA. Seeking to work against deficit-based

understandings of development, we sought to develop a microgenetic methodology

appropriate to the study of thriving children learning through everyday play and

participation in family practices. With the videoing of a day in the life of children at the core,

supplemented by other evidence including field notes and interviews, our team of

researchers examined the children's interactions with their environment, including

caregivers. Common themes were identified for activities in which a multiplicity of

intentions and clearly identifiable elements of cultural knowledge were drawn upon as the

children pursued their interests.

Theoretical framework

Our primary aim in our ecocultural investigation of culture in the lives of two-year-old girls

in their family settings was to identify diverse ways of thriving through study of the early

home lives of ‘strong’ children in seven home contexts across the globe. We sought to avoid

a comparative approach, but rather to explore the affordances of rich empirical data for

dialogic and iterative practices, thinking about the meaning-making processes of all

involved – children and adults.

Nsamenang (1992) suggested applying an ecocultural framework to developmental studies.

He drew on Pence's (1998, p. xii) assertion that this is 'far more conceptual than

methodological, more a call to thoughtful, systematic awareness'. Studying the relationships

between researcher and researched, is not a question of accessing transparent ‘realities’ but

rather that of negotiating new meanings. Working together as participants from different

countries and from origins in multiple disciplines: early years education and

psycholinguistics, literacy research, developmental and health psychology, we evolved not a

list of specific research questions, but rather broad areas of enquiry. We sought to explore

specific aspects of cultural activities seen by participants (parents, local and distal

researchers) as constructive to strong and healthy growth. We decided to do this not by pre-

identifying the domains of activity we were going to study, e.g., play and relationships with

parents but to use a more inductive approach arising from an examination of video data to

examine what seemed significant to the children in their lives. So, for example, musicality,

although not an obvious and expected theme at first, did in fact emerge as a theme that we

have explored (Young & Gillen, 2007).

Endeavouring to take an ecocultural approach to research has value for us in our

sociohistorical perspective, as it is evocative of the complex, networked and dynamic

activities we think of as cultural. ‘Culture’ as many have observed has become far extended

in different disciplines so that it can be difficult to pin it down. Cole (1997, p. 250) proposes

that any simple correlation of culture as a uniform ensemble of ‘shared beliefs, values,

symbols, tools’ in what he refers to as a ‘configurational’ approach is flawed but suggests:

3

‚There is no doubt that culture is patterned, but there is also no doubt that it is far

from uniform and that its patterning is experienced in local, face-to-face interactions

that are locally constrained<‛

This notion of patterning as opposed for example to contrasts and comparisons that are

measured according to one particular ‘norm’ is extremely useful, and our methods are

designed to enable us to investigate the details of these ‘local, face-to-face interactions’ and

some of the ways in which we might explore some of the ‘local constraints’. Video is an

extremely useful tool for picking up not only the minutiae of spoken dialogue, but also that

of bodily alignment, attention directing and other embodied communicative actions that

could be missed by an observer.

Methods and data sources

Our approach is interpretive in the sense that we make use of multiple routes to reaching

understandings and seek to approach and understand the perspectives of research

participants, rather than thinking of ourselves as ‘objective’ outsiders. Gaskins (1999: 27)

encapsulates the two principle prongs of our approach:

"The process of development can be understood only by < a dual research agenda.

First, one must study children engaged in their daily activities to observe the unit of

child-in-activity-in-context that represents the locus of the developmental process.

Second, one must also study the cultural belief systems and institutions that are

responsible for consistency in the everyday contexts of behavior experienced by

children."

Our approach, further developing that of Tobin, Wu and Davidson (1989), documents the

daily rounds of young children in context, and inspects those contextualized activities from

a variety of both professional and personal perspectives. Colleagues indigenous to the

child’s home background as well as those from different cultural backgrounds; colleagues

from a range of different disciplines and locations observe footage of the child’s day; and

family members review and comment on segments of the day. In each country we followed a

five-phase protocol (Gillen, Cameron, Tapanya, Pinto, Hancock, Young, & Accorti

Gamannossi, 2007).

1. Locating research participants

Colleagues from different countries designed the initial protocols and located an appropriate

family, with an apparently thriving two and a half year old girl, willing to engage in the

project.

2. Pre-filming: family preparation

Two researchers visited the family to establish initial rapport and collect basic demographic,

health and lifestyle information through a semi-structured interview. The project aims,

extents of commitment, constraints on confidentiality and participants’ rights, were fully

discussed with the families. There was also a one-hour session of filming to accustom the

child and her interactants at least slightly to the experience of being in the presence of a

video camera-person and field-note taker for an entire waking day.

4

3. Day in the Life first iterative filming

The two researchers arrived at the family home soon after the child woke and stayed for as

much of the day as possible. Videoing was stopped while the child was asleep or engaged in

bathroom activities. At least six hours of film was obtained in each location. The researcher

present who was not videoing, quietly observed, making notes on a spreadsheet on a

clipboard, identifying the times the child changed her activity or location and people present

at the scene. S/he also wrote explanatory notes about other activities or features of the

environment that could support later analysis of the video material.

4. Selection of focal interchanges

Day in the Life videos were collected and perused individually and then together by two

distal project investigators. The focus on real time viewing and reviewing by the

investigators who are from two different countries and disciplines, afforded a sense of

attunement with each local day. Working together the principal investigators edited a half

hour compilation video of approximately six five-minute clips that in collaboration they

considered displayed a variety of the activities and kinds of interactions the child had

engaged in over the day, and which appeared to tap in on the family’s striving to support

the healthy development of their child.

5. Second iterative stage

After scrutinizing the compilation video, the local investigators returned to the target family

with the tape. They filmed an interview during which the participants together watched the

compilation video, pausing between sections for reflexive discussions. Families in each

context responded with reactions to the selection of video data in ways that often enhanced

or reoriented the researchers’ provisional understandings. The families demonstrably

enjoyed their participation. The meeting afterwards was welcome and of course the

participants appreciated their gift of the compilation tape.

We then had as data the video of the whole day and associated field notes, records of the

initial interview and field plans. In this paper we choose to illustrate our methodology and

discuss some findings from the Italian day.

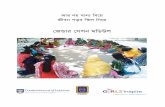

A Day in the Life: Beatrice in Italy

In order to demonstrate our approach and the development of our understandings, we will

organise this section of the paper through three vignettes. That is, we will endeavour to

present through present-tense writing and a single still image 'grabbed' from the video a few

short moments in the day. In each case, we will then as it were refocus our methodological

lens in order to illustrate some salient factors relating to our research perspective and

findings.

Vignette 1: the beginning of Beatrice's day, illuminating methodology

It is a hot day in Italy and Beatrice has already been to the park with her father Claudio and

returned home. In the living room of the compact city apartment, Claudio is blowing

bubbles, which Beatrice jumps about excitedly, trying to catch.

5

She suddenly sees a large ball in the corner of the living room and takes it, alternately

bouncing, throwing and kicking it. Each time it only goes a short way and then has to be

retrieved from under a piece of furniture. One such is a computer on a desk, clearly an adult

'office' taking up a small area of the hall adjacent to the living room; another is a toy 'kitchen'

which takes up a substantial portion of the living room rug.

In fact, of course, the apparent transparency of this brief descriptive account, seemingly so

naively evident, is a construct from the process of research. Beatrice's excited movements

are all the time in close proximity to the two researchers, Pinto and Accorti Gamannossi,

Italian developmental psychologists who have spent years working and living in or near this

city. Beatrice cannot help but engage them in her enthusiasm; they try hard to respond

warmly but quietly as they are seeking not to play with her but to record her actions

through videos and field notes during this day. It will be spent in this apartment that

although it might be deemed constrained to some observers, has a wealth of opportunities

for activities that interest Beatrice. Shortly, her mother will return home from working in her

active profession and the remainder of the day will be played out among the family of three.

The careful preparation and enjoyment of midday meals will constitute some highlights.

The research team will seek to understand the day through processes of iterative discussion

with distant researchers in the project team and, as well, through discussions a few months

later when the compilation video is discussed with the family. Also salient to the extended

analysis processes is the discussion in the interview before the day. Pinto and Accorti

Gamannossi had decided to advance as an initial translation of 'strong child' as 'bambino in

gamba' - which might in turn be back translated as 'a child standing on her own two feet').

During the interview the parents identified thriving health, the ability to act on her own

initiative, self confidence and security as valued priorities. They said they believed that

parents’ presence, modeling and sharing life experiences provided security over time, and

were fundamental. They said that 'when it is possible it is very important to do things all

three [two parents and child] together.... Surely we can’t give her the best directions, but

nevertheless we think we are able to give her our good principles and this is a good starting

point.' Both parents thought that personal disposition and character were important as an

attribute, and that Beatrice had ' a very strong character.'

6

Lucia and Claudio also felt that relationships with others were very significant as building

blocks in a thriving child, and they created opportunities for their daughter to meet and

spend time with others. They noted that Beatrice exhibited an 'evolution' after she started

attending nursery school in this respect, and that they had consciously decided that she go

to day care instead of being taken care of at home, as this experience afforded her

opportunities to build up relationships. Her mother also added that there must be a balance

between a child’s needs and parents’ needs. Understanding these goals for their own child

assists the interpretation of their interactions, although it is important not to seek any over-

simplified causal connection when considering any specific data: in this respect the Italian

parents were wise in suggesting to us: "the attributes of a hardy child do not come with

'recipes'."

Vignette 2: Lap game, illuminating musicality

This episode occurred after Beatrice had taken a midday nap and was transitioning from a

drowsy state to being more alert. Kneeling on her mother, Lucia's lap in the kitchen, facing

her and holding both her mother's hands, she rocks to and fro in a strong, duple meter.

Lucia picks up the same strong rocking rhythm and its tempo exactly in a rhythmical chant –

'tira, molla e lascia andar!'. Each word has an accent on the first syllable; a rhythmic

characteristic of the Italian language, and this synchronises with and etches the accented,

two-beat rocking movement. Each short rhythmic motif arrives at a point of climax when

Lucia pretends to let go when Beatrice is leaning backwards, as if she might tip backwards

and fall. The third, fourth and fifth repetitions extend the pattern by an extra rocking

movement and each repetition increases in intensity with longer pauses before and after the

pretend moment of dropping. Lucia ratchets up the emotional intensity of the moments

when she might drop her by vocalising mock shudders of fear. Beatrice is secure that her

mother will not drop her, but they both play with and enjoy this moment of risk and thrill.

The game increases to a pitch of excitement with squeals from Beatrice. At this point, Lucia

ceases the game, apparently suspecting that to continue it would be to spill in to over-

excitement. She winds down the activity and remains physically quite still and quiet,

diverting attention to Beatrice's hair clip.

7

H. Papousek (1996) has previously identified the value of this kind of interaction, assisting

us to recognise in all the day instances in which musicality was evidently highly salient to

the lived experienced of children.

"<parents sensitively respond to changes in infant emotional/behavioural state and

modify singing or musical elements in their speech so as to either maintain quiet and

active waking states in infants or to facilitate transitions to sleep. Thus they reduce

the proportion of transitory infant states characterised by upset and a poor level of

integrative and communicative abilities" (H. Papousek, 1996, p. 50 see also M.

Papousek, 1996).

We use the concept of musicality in its widest sense to emphasise the richness and diversity

of ways in which contoured sounds and rhythms imbued the children's activities. Perhaps

not always having access to the linguistic codes at the time of first engaging with the data

brought us fresh awareness that the sharp distinction between 'speech' as sound and

'musical' vocalisation is a historically invented distinction and a relatively recent one at that

(Ingold, 2007). As our research developed and more translations were carried out we

certainly settled to a more conventional parsing of speech, but this served to enhance our

recognition through the project that young childhood is an intrinsically multimodal state of

being. We examined ways in which the children experience themselves shape and are

shaped by essentially musical events.

So, musicality for us includes not only song singing and listening and dancing to pre-

recorded music as the term more obviously implies, it also includes instances of rhythmic or

vocalised activity woven in to the ongoing days' events (Campbell, 1998; Young & Gillen,

2007). Some of these instances were substantial and easily noticeable; some were fleeting and

woven in to other activity to be almost imperceptible. We treat music as a perfectly ordinary

human activity, not one that is marginal or in any sense privileged. We thus avoid the

prototypical tendency of Western art music to treat music and musical practices as

something set apart, floating free of context.

Vignette 3: safe spaces for explorations

Finally, we saw Beatrice just above awakening from her nap cuddling in her mother’s lap,

rhythmically singing and clapping: mutual comfort-giving is exchanged. This interaction is

a launching pad for a subsequent session Beatrice has on the terrace, where she engages in

water play, toy washing and caring for ‘Coccolone’ her life sized baby doll.

She collects a red plastic chair and - partly pushing, partly carrying - moves it, unassisted, to

the terrace that adjoins the kitchen. Beatrice places this chair next to a low seat that is

already on the balcony. She then picks up Coccolone and places her on the red plastic chair.

8

Beatrice sits next to the doll on a low seat. Smiling, she shuffles in her own low seat to

establish a suitable position and then pulls the red plastic chair and doll closer to her side as

though she is place-making.

Beatrice says ‘Nice to meet you’ and holds the doll’s hand. Lucia stimulates her play in the

background suggesting that Beatrice and her doll may need to have a nappy change.

Beatrice declines. Again Beatrice takes Coccolone’s hand and repeatedly kisses the doll’s

cheek. Realising that her own seat has moved a little away from the balcony railings, she

stands and pushes it back to locate and better secure it. Beatrice shows considerable

contentedness at being on the terrace with Coccolone, and great pleasure at managing her

play and equipping the space. Sometimes, she chuckles and rocks on her seat showing high

satisfaction with the way in which she has established herself in this safe space. Yi-Fu Tuan

writes: ‘< space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value' (Tuan,

1977, cited in Cresswell, 2004:8). Such place making, we would argue, enable rootedness

and attachment to the domestic spaces as to enhance emotional security (much as joint book

reading does [Cameron & Pinto, 2009]) within the child’s own home environment.

Conclusions

The accounts of Beatrice here as the other children in our project as a whole are not

concerned with universalising from particular instances, but in recognising and staying with

the specific, the small, the ordinary and day-to-day – all not necessarily easily noticed by

researchers. A reintegration of auditory, kinaesthetic and other sensory dimensions is part of

that commitment. It enables us to take other soundings of these children's lives and to go

beyond some of the immediate concerns of child studies. However, giving more prominence

to what might be relatively neglected senses is not about making a simple reversal of

importance. Our presentations here rest as much on visual information conveyed through

our video stills as in our verbal descriptions, combining we hope with the capacity to evoke

embodied experience. We are not attempting to displace the visual, but rather to point to the

crucial roles that sound, body rhythm, touch and placemaking contribute to the

development of understanding and healthy growth.

Our fuller analyses from the Italian day, just a portion of which have been alluded to here of

course, identify patterns that we have observed common to all settings. We have observed

nurturant interactions such as gentle pats and touches, swinging and rocking and the

9

locations in which the children create safe spaces to play in the settings. Likewise, we have

found various experiences with notational systems mediated by adults.

Children as ‘strategic actors’ (James and Prout, 1996: 47) are seen successfully to intermingle

their personal play interests with meeting the expectations of their carers. Our glimpses into

the children’s worlds support a generally bidirectional view of socialisation (Pontecorvo,

Fasulo, & Sterponi, 2001), as children and adults reciprocally co-construct their worlds in the

moment-by-moment development of activities as identified in Beatrice’s musical/rhythmical

and creating safe spaces as we have shown above. Close examination of (relatively)

naturalistic data has assisted the analysis of this element of the ecocultural framework

within which these children and adults mutually adapt their diverse needs and intentions.

We would suggest that although there is a considerable turn to multimodality in studies of

early childhood there is still potential for thinking theoretically about the relationship of

language with action (Scollon, 2001). Anning and Edwards (1999) proposed that

communication in early childhood is especially multimodal. Recently, considerable work

has been conducted in the discipline of applied linguistics (and education) concerned with

extending language-based approaches to communication into a greater consideration of

multimodality – see Jewitt, (2009a) for a synthesis. As many contributions to that edited

collection make plain, this new focus on multimodality draws upon work in disciplines

including anthropology, sociology and psychology of attention to non-verbal elements of

communication. Introducing the book's approach to multimodality, Jewitt (2009b, p. 1)

explains:

The starting point for multimodality is to extend the social interpretation of language

and its meanings to the whole range of representational and communicational modes

or semiotic resources for meaning making that are employed in a culture – such as

image, writing, gesture, gaze, speech, posture.

However, we would argue that this does seem to instantiate an individualised emphasis on

multimodality as if most essentially pertaining to the individual body. We intend in future

work to explore a more interactional focus on multimodality, drawing on our analyses of

data concerned with the interaction of the child with others and with the environment as

intrinsic to her developing understandings and communicative practices.

We venture to claim that this project makes a direct contribution to the overarching theme of

this year's AERA conference: "Understanding complex ecologies in a changing world." We

have demonstrated how the repertoires for action that these children develop in everyday

settings are intrinsically complex and ever shifting. Seeking to contribute to the emerging

field of "global-local childhood studies" (Fleer, Hedegaard & Tudge, 2009), we believe that

broader understandings of diversity can advance appreciation of the interactive impacts of

children and youth, context, material culture, and care givers in the acculturation of strong

children and thereby inform a developmental appreciation of the many paths to ‘growing

up well’ across ages across the globe.

Members of the project team have extended the project methodology into two further

current projects. The day in the life methodology has been adapted in a project studying

10

resilient early adolescents in eight international locations (Cameron, Lau & Tapanya, 2009).

The teenagers' own perspectives are elicited far more directly, from being the sole

interactant with the researchers at the initial interviews, through complementary visual

methodologies to enhance the data collection on the day and subsequent iterative stages.

Young is leading a project MyPlace MyMusic exploring everyday music in the home among

seven-year-olds in diverse locations, again through adapting the day in the life methodology.

Elsewhere the project methodology is being adapted for use in research studies concerned

with the interactions between early years education practitioners and children in bilingual

settings (Cable, Drury & Robertson, 2009) and an international study on the experiences of

early years practitioners in seven different countries (Miller, Cable and Goodliff, 2009 report

on one setting involved). Concerns about globalization becoming synonymous with North

Americanization could be attenuated by projecting light on the positive contributions of

culturally sensitive studies of children in diverse settings that provide an appreciation of the

multiplicity of opportunities for the development of well being in its many manifestations.

References

Anning A. & Edwards A. (1999). Promoting children’s learning from birth to five: Developing the

new early years professional. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Cable, C., Drury, R. & Robertson, L. H. (2009) A day in the life of a bilingual practitioner:

ways of mediating knowledge, Power point presentation, Centre for Excellence in Teaching

and Learning Conference Fellows Event, The Open University. Online at

http://www.open.ac.uk/cetl-workspace/cetlcontent/documents/4b0e9777d5cfc.pdf

accessed 7 April 2010.

Campbell P.S. (1998). Songs in their heads: Music and its meaning in children’s lives. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Cameron, C.A., Lau, C. & Tapanya, S. (2009). Passing it on during a Day in the Life of resilient

adolescents in diverse communities around the globe. Child and Youth Care Forum, 38 (5),

227-271.

Cameron, C.A. & Pinto, G. (2009). ‚A Day in the Life‛: Secure interludes with joint book

reading. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 23(4), 437-449.

Cole M. (1997). Cultural mechanisms of cognitive development. In E. Amsel & K.A.

Renninger, (Eds.), Change and development: Issues of theory, method and application (pp. 245-

263). London: Erlbaum.

Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Fleer, M., Hedegaard, M. & Tudge, J. (Eds.), (2009). Childhood studies and the impact of

globalization: Policies and practices at global and local levels. New York: Routledge.

Gaskins S. (1999). Children’s daily lives in a Mayan village. In A. Goncu (Ed.), Children’s

engagement in the world: Sociocultural perspectives (pp. 25-81). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Gillen, J. & Cameron, C.A. (Eds.) (2010). International perspectives on early childhood research: A

Day in the Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gillen, J., Cameron, C.A., Tapanya, S., Pinto, G., Hancock, R., Young, S. & Accorti

Gamannossi, B. (2007). 'A day in the life': Advancing a methodology for the cultural study of

11

development and learning in early childhood. Early Child Development and Care. 177(2), 207-

218.

Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A brief history. London: Routledge.

James, A., & Prout, A. (1996). Strategies and structures: Towards a new perspective on

children’s experience of family life. In J. Brannen & M. O’Brien (Eds.), Children in families:

Research and policy (pp. 41-52). London: Falmer Press.

Jewitt, C. (Ed.), (2009a). The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (2009b) Introduction: Handbook rationale, scope and structure. In C. Jewitt (Ed.),

The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge. pp. 1-7.

Miller, L. Cable, C. and Goodliff, G. (2007) A day in the life of an early years practitioner in

England. Power Point presentation, Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

Conference, The Open University. Online at http://www.open.ac.uk/cetl-

workspace/cetlcontent/documents/499eab18807f0.pdf

accessed 7 April 2010.

Nsamenang, A. B. (1992). Human development in cultural context: A third world perspective. New

York: Teachers College Press.

Papousek, H. (1996). Musicality in infancy research: Biological and cultural origins of early

musicality. In I. Deliège & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Musical beginnings: Origins and development of

musical competence (pp. 37-55). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Papousek, M. (1996). Intuitive parenting: A hidden source of musical stimulation in infancy.

In I. Deliège & J. Sloboda (Eds.), Musical beginnings: Origins and development of musical

competence (pp. 88-112). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pence, A.R. (1988). Ecological research with children and families: From concepts to methodology.

New York: Teachers College Press.

Pontecorvo, C., Fasulo, A. & Sterponi, L. (2001). Mutual apprentices: The making of

parenthood and childhood in family dinner conversations. Human Development, 44, 340-361.

Scollon, R. (2001) Mediated Discourse: the nexus of practice. London: Routledge.

Tobin J., Wu D., & Davidson D. (1989). Preschool in three cultures: Japan, China and the United

States. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Young, S. & Gillen, J. (2007). Toward a revised understanding of young children’s musical

activities: Reflections from the ‚Day in the life‛ project. Current Musicology, 84, 79-99.