A cluster randomised trial of a telephone-based intervention for parents to increase fruit and...

-

Upload

newcastle-au -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of A cluster randomised trial of a telephone-based intervention for parents to increase fruit and...

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Open AccessS T U D Y P R O T O C O L

Study protocolA cluster randomised trial of a telephone-based intervention for parents to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in their 3- to 5-year-old children: study protocolRebecca J Wyse*1, Luke Wolfenden1, Elizabeth Campbell1,2, Leah Brennan3, Karen J Campbell4, Amanda Fletcher1, Jenny Bowman5, Todd R Heard2 and John Wiggers1,2

AbstractBackground: Inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption in childhood increases the risk of developing chronic disease. Despite this, a substantial proportion of children in developed nations, including Australia, do not consume sufficient quantities of fruits and vegetables. Parents are influential in the development of dietary habits of young children but often lack the necessary knowledge and skills to promote healthy eating in their children. The aim of this study is to assess the efficacy of a telephone-based intervention for parents to increase the fruit and vegetable consumption of their 3- to 5-year-old children.

Methods/Design: The study, conducted in the Hunter region of New South Wales, Australia, employs a cluster randomised controlled trial design. Two hundred parents from 15 randomly selected preschools will be randomised to receive the intervention, which consists of print resources and four weekly 30-minute telephone support calls delivered by trained telephone interviewers. The calls will assist parents to increase the availability and accessibility of fruit and vegetables in the home, create supportive family eating routines and role-model fruit and vegetable consumption. A further two hundred parents will be randomly allocated to the control group and will receive printed nutrition information only. The primary outcome of the trial will be the change in the child's consumption of fruit and vegetables as measured by the fruit and vegetable subscale of the Children's Dietary Questionnaire. Pre-intervention and post-intervention parent surveys will be administered over the telephone. Baseline surveys will occur one to two weeks prior to intervention delivery, with follow-up data collection calls occurring two, six, 12 and 18 months following baseline data collection.

Discussion: If effective, this telephone-based intervention may represent a promising public health strategy to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in childhood and reduce the risk of subsequent chronic disease.

Trial registration: Australian Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12609000820202

BackgroundInadequate fruit and vegetable consumption contributesto a variety of chronic diseases and is estimated to beresponsible for 2.6 million deaths per year worldwide [1].A substantial proportion of adults [2,3] and children [4]from developed countries, including Australia [5,6], con-

sume insufficient quantities of fruit and vegetables. The2002 World Health Report estimated that 4% of the dis-ease burden in developed countries was attributable tolow fruit and vegetable intake [7]. Increasing consump-tion in early childhood may be an effective strategy toreduce the risk of subsequent chronic disease associatedwith insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption, asdietary patterns in childhood appear to track into adult-hood [8].

* Correspondence: [email protected] School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, AustraliaFull list of author information is available at the end of the article

BioMed Central© 2010 Wyse et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative CommonsAttribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction inany medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 2 of 12

Parents are likely to be influential in the development ofchildren's eating behaviours [9]. Parental practices associ-ated with increased child consumption of fruit and vege-tables include increasing the availability and accessibilityof fruit and vegetables within the home [10], role-model-ling fruit and vegetable consumption [11] and establish-ing family eating routines supportive of fruit andvegetable consumption, such as eating meals as a family[12] not in view of a television [13]. Despite such influ-ence, a lack of knowledge and skills can prevent parentsfrom utilising these opportunities to promote healthy eat-ing habits in their children [14].

Assisting parents to create supportive home environ-ments can be an effective strategy to increase the fruitand vegetable consumption of their children [15]. How-ever, studies involving traditional means of deliveringinterventions to parents, such as education sessions,often report high drop-out rates [16] and low attendancedue to barriers associated with transport, work schedulesand lack of interest [17]. Parent participation in healthyeating interventions is also reportedly constrained byspecific barriers associated with preschool-aged children,including unpredictable sleep times and frequent sick-ness [18]. Telephone-based interventions may overcomemany of these barriers and provide a convenient andeffective means for parents to receive healthy eating sup-port for their children. For example, previous researchwith adults has found that telephone support is anacceptable method of delivering health information [19]and is an effective strategy in modifying a range of healthbehaviours, including smoking [20], physical activity [21]and diet [22-24]. Furthermore, almost all Australianhouseholds have telephones [25]; thus, telephone-deliv-ered interventions have the capacity for broad reach, andmay hold promise in specifically targeting disadvantagedcommunities [26].

Despite the potential of telephone-based interventionsto provide effective and acceptable support to parents,the authors are not aware of any randomised controlledtrials of such interventions specifically targeting healthyeating behaviours in preschool children. The studyattempts to address this gap in evidence through the con-duct of a cluster randomised controlled trial of a tele-phone-based parent-focused intervention to increase thefruit and vegetable consumption of children aged 3 to 5years. This paper describes the methodology to beemployed in the conduct of this trial.

Methods/DesignStudy AimThe aim of this study is to examine the efficacy of a four-week telephone-based parent intervention in increasingfruit and vegetable consumption of 3- to 5-year-old chil-dren, as assessed by parental report.

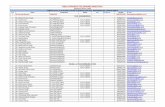

Study DesignOverview of study designThe study employs a cluster randomised design, as out-lined in Figure 1. The research will be reported in accor-dance with the requirements of the CONSORT statement[27]. Parents of 3- to 5-year-old children attending ran-domly selected preschools in the Hunter region of NewSouth Wales, Australia, are being approached to partici-pate. Preschools will be randomised to either control orintervention groups using a random number function inMicrosoft Excel. Parents of children attending preschoolsallocated to the intervention group will receive a series ofinstructional resources and four 30-minute telephonecalls delivered weekly by trained telephone interviewers.Parents of children attending preschools allocated to thecontrol group will receive a readily available nutritionresource published by the Australian Government [28].To assess the efficacy of the intervention, surveys will beconducted with parents via Computer Assisted Tele-phone Interview (CATI) at baseline (occurring one to twoweeks prior to commencement of intervention delivery)and two, six, 12 and 18 months following baseline datacollection.

The trial is funded by the Cancer Institute New SouthWales (Ref no. 08/ECF/1-18). In-kind support for the trialis also provided by the Hunter New England PopulationHealth Service. The trial has been approved by theHuman Research Ethics Committees of the University ofNewcastle (Ref No. H-2008-0410) and the Hunter NewEngland Area Health Service (Ref No. 08/10/15/5.09).

Research SettingThe study region encompasses non-metropolitan 'majorcities' and 'inner regional' areas as described by the Aus-tralian Standard Geographic Classification system [29].The region has lower indices of socio-economic statusthan the national average and has 485,700 residents, with18,200 children aged 3 to 5 years [29]. Nine percent ofHunter residents speak languages other than English [30].

Participants and Research EligibilityPreschoolsThirty preschools will be recruited into the trial. Pre-schools in Australia provide educational and develop-mental programs for children (3 to 5 years) for up to twoyears prior to the commencement of full-time primaryschool education [31]. Preschool services are usually pro-vided by qualified teachers for approximately six hoursper weekday [32]. Sixty-four percent of all 4-year-oldchildren in New South Wales attend preschool, with anaverage attendance of 17 hours per week [33]. Each pre-school in the study area provides, on average, care for 27children per day [34].

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 3 of 12

A current list of all preschools in the region that arelicensed to provide care for 3- to 5-year-old children willbe obtained from the New South Wales Department ofCommunity Services (the licensing agency). Preschoolswill be excluded from the trial if they provide meals tochildren in their care (as this limits parents' capacity to

influence the foods their children consume), cater exclu-sively for children with special needs (given the specialistcare required for such children), are Government pre-schools (as conduct of the research has not beenapproved by the New South Wales Government Depart-ment of Education and Training) or have participated in

Figure 1 CONSORT flow diagram estimating the progress of preschools and parents through the trial.

Excluded: N=29

Not meeting inclusion criteria N= 22

Refused to participate N=7

Analysed (n=150) Analysed (n=150)

Lost to follow-up (n=5) Lost to follow-up (n=5)

Lost to follow-up (n= 15) Lost to follow-up (n=15)

Lost to follow-up (n=25) Lost to follow-up (n=25)

Assessed for eligibility

(No. of preschools) N=59

Randomised

(No. of preschools) N=30

Allocated to intervention

(No. of preschools) N=15

(No. of parents) n=200

Allocated to control

(No. of preschools) N=15

(No. of parents) n=200

Allocation

6 month follow-up

12 month follow-up

18 month follow-up

Analysis

2 month follow-upLost to follow-up (n= 5) Lost to follow-up (n=5 )

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 4 of 12

child healthy eating research projects within six monthsof the commencement of recruitment. Informationregarding eligibility of preschool services will be con-firmed by preschool supervisors during phone contact aspart of the recruitment process.ParentsFour hundred parents will be recruited to the study. To beeligible, each participant must be a parent of a child aged3 to 5 years attending a participating preschool, mustreside with that child for at least four days a week (inorder for the child to be sufficiently exposed to the inter-vention strategies that the parent may implement), musthave some responsibility for providing meals and snacksto that child, and must be able to understand spoken andwritten English. Information regarding parent eligibilitywill be ascertained from completed study consent formsand verified during phone contact with parents immedi-ately prior to baseline data collection. Parents will beexcluded from the trial if their children have specialdietary requirements or allergies that would necessitatespecialised tailoring of the intervention or that may beadversely affected by the intervention. Such exclusionswill be determined by an Accredited Practising Dietitianwho is independent of the research team.

Recruitment and AllocationPreschoolsPrior to formal requests to participate, the research trialwill be promoted to preschools within the region throughexisting networks established by the Good for Kids. Goodfor Life program, a high-profile childhood obesity preven-tion program in the region [35]. Agreement has beenreached with the Good for Kids program for this researchproject to utilise the Good for Kids brand and the pro-gram's communication channels with preschools. Specifi-cally, newsletters and program emails will be used tomake preschool supervisors aware of the trial and of whatwill be required of them if they consent to participate.

Participating preschools and the order in which theyare to be approached to participate will be randomlyselected from the New South Wales Department of Com-munity Services database by an independent statisticianusing a random number function in Microsoft Excel.Recruitment will be staggered over a four- to five-monthperiod due to intervention delivery capacity constraints.Preschools will therefore be approached in batches, untilthe desired sample of parents is achieved. The supervi-sors of the selected preschools will be sent letters andconsent forms informing them of the study and request-ing permission to recruit parents through their services.Consent will be obtained when the supervisor faxes orposts the consent form back to the research team. Twoweeks after the initial information letters are sent tosupervisors, a study research assistant will telephone

supervisors who have not yet returned their consentforms to answer any questions they may have and toremind them to return their forms, confirming their con-sent or otherwise. Similar recruitment methodsemployed by the researchers as part of an Australianhealthy eating and physical activity study were successfulin achieving a childcare service participation rate of 84%[34].ParentsIn order to maximise parent participation in the study, arecruitment strategy based on a review of successfulrecruitment practices within the school setting [36] hasbeen devised. Recruitment will incorporate the followingfour strategies recommended to maximise research par-ticipation.1. Recruitment oversight One member of the researchteam will act as a dedicated recruitment coordinator. Allpreschool supervisors and parents will be provided withthe direct phone number of the coordinator for all enqui-ries regarding research participation. The coordinatorwill also manage the rate at which preschools arerecruited and monitor preschool and parent consentform return rates. The recruitment coordinator will notbe involved in the delivery of the telephone support orthe collection of data.2. Promotion of the research prior to requests for participation A promotional flyer explaining the studywill be sent to supervisors to disseminate to all parents atconsenting preschools. The flyer will inform parents ofthe trial and the opportunity to participate, and willinclude endorsement of the research by a clinical psy-chologist and parenting expert. Such contact prior to aformal request to participate has been shown to increaseresponse rates to postal questionnaires [37] and will beimportant in engaging parents where face-to-face contactis not possible. The project name, flyer and recruitmentdocumentation will include the Good for Kids logo andbrand name [35]. Following a recent media campaign,unpublished data indicated that 59% of parents within thearea reported that they were aware of the Good for Kidsprogram.3. Dissemination of recruitment materials via methods to maximise parent engagement The recruit-ment coordinator will arrange for recruitment packs tobe delivered to each participating preschool, enough forone per family of each enrolled child aged 3 to 5 years.Distribution of these packs to parents will occur viamethods considered by the preschool supervisor to bemost effective and appropriate in engaging parents.Where possible, research staff will attend the preschool,hand out recruitment packs to parents and be available toanswer parent questions. The recruitment pack consistsof an information sheet, a consent form and a returnenvelope. The pack is brightly coloured and specifies that

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 5 of 12

the study is being conducted in conjunction with a uni-versity; these strategies are suggested to increaseresponse rates among those parents who have onlyreceived written communication during recruitment [37].4. Parent reminders One to two weeks after delivery ofthe recruitment packs, reminder letters will be dissemi-nated to parents, reminding them of the study and theopportunity to participate.

Parents will be asked to return the consent forms in theenvelopes provided and place them in drop-boxes at theirchildren's preschools within three weeks. The consentform includes a brief set of questions to establish thechild's usual fruit and vegetable consumption. In order toidentify any bias due to selective non-participation, allparents of 3- to 5-year-old children will be encouraged tocomplete the items on the consent forms and returnthem, regardless of whether they choose to participate.Random allocation of preschoolsFollowing the recruitment of parents within a preschool,an independent statistician will randomly allocate thepreschool to an intervention or a control group using arandomisation function in Microsoft Excel. Randomisa-tion at the unit of the preschool, rather than the individ-ual parent, will reduce the potential for interventioncontamination between parents whose children attendthe same preschool [38]. Based on evidence suggestingthat children's eating environments differ by socio-eco-nomic status [39], the randomised allocation will be strat-ified by the socio-economic status of the area in whichthe preschool is located [40]. Preschools with a postcodein the top 50% of the state, based on Socio-EconomicIndexes for Areas (SEIFA) [41] will be defined as 'highsocio-economic area preschools' and those within thelower 50% will be defined as 'low socio-economic areapreschools'. Preschools will be randomised in a 1:1 (inter-vention:control) ratio in randomly sequenced blocks ofbetween two and six preschools. Block randomisationwill maximise the likelihood that the number of partici-pants allocated to each group remains approximatelyequal [42]. Due to the difficulty in concealing group allo-cation from participants, parents will not be blinded, andfollowing baseline data collection they will receive lettersinforming them that they will receive either print materi-als or telephone support.

Intervention GroupThe 200 parents randomised to the intervention groupwill receive a workbook and other resources and weeklyscripted telephone contacts of approximately 30 minutes'duration delivered over four weeks. Telephone-basedinterventions of a similar intensity have previously beenfound to be effective in adults [43,44]. Each telephonecontact aims to provide parents with appropriate knowl-edge and skills to modify three key domains within the

home food environment: availability and accessibility offruit and vegetables; supportive family eating routines,and parental role-modelling (See Table 1).Development and pre-testing of the interventionThe script has been developed by an expert advisorygroup of clinical and health psychologists, dietitians andhealth promotion practitioners. The script utilises CATIsoftware [45] to tailor support based on parental report ofthe home food environment. Intervention developmentwas guided by an existing framework for behaviouraltherapy development in clinical settings [46]. The pre-testing process involved three phases where the researchteam piloted preliminary versions of the telephone scriptand workbook, and refined the intervention based on thefeedback received. Each phase of pre-testing was con-ducted with eight to 12 volunteer health promotion prac-titioners, parenting experts and parents of youngchildren. Volunteers were asked to comment on content,structure, presentation and length of the intervention,and were encouraged to suggest how the telephone scriptor workbook could be improved. Feedback from themembers of the research team who administered the pre-test telephone calls to volunteers was also sought regard-ing the ease of administration of the script and the levelof volunteer engagement in the intervention.

Following each pre-testing phase, feedback was collatedand proposed intervention amendments were discussedby the research team and adopted where feasible. Theprimary amendments to the intervention telephonescript resulting from pre-testing included reducing thelength of the calls; changing the order of presentation ofintervention content; reducing repetition; providingmore examples to clarify key issues; simplifying language;removing jargon; making the script more conversational;and including more opportunities for interactionbetween parents and interviewers. The primary amend-ments to the workbook included the addition of morepractical information and tools for parents, improvingreadability through simplifying language, using subhead-ings and reducing the volume of text, and improvementsto the presentation of the workbook to make it moreappealing, such as use of bright colours, illustrations andphotographs.Intervention contentThe telephone intervention script is designed to help par-ents modify their home food environments throughaddressing three key domains listed in Table 1. The firstcolumn of the table lists each domain at the point atwhich it appears in the schedule of support calls, whilethe second column lists the specific topics that are usedto explore each of the given domains. Each domain hasbeen associated with increased fruit and vegetable con-sumption in children as described below.

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 6 of 12

Table 1: Overview of intervention call content: behaviour change techniques and their application

Key Theme Content Behaviour Change Technique

Application ofBehaviour Change

Technique

WEEK 1Availability and Accessibility

Dietary recommendations and serving sizes

Children's food diary Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour

Parents are asked to monitor their children's intake of fruit, and vegetables over 3 days.

Ways to provide fruit and vegetables throughout the day

Setting goals Prompt specific goal-setting Parents are encouraged to set a program goal.

WEEK 2Availability and Accessibility,

Supportive Family Eating Routines

Changing the family routine Prompt intention formation Parents decide which activities they will attempt in the coming week.

Availability and accessibility of foods in the home

Provide general encouragement

Interviewers provide positive feedback about any helpful practices occurring in the home.

Mealtime practices Teach to use prompts or cues Parents learn the HELPS acronym, i.e. try to eat when Hungry, not attempting anything else at the same time (focus on Eating), at an appropriate Location to eat, from a Plate, and while Sitting.

Meal planning

Review of goals Prompt review of behavioural goals

Parents review the goals they set during the previous calls and evaluate their progress.

WEEK 3Parental role-modelling, Supportive Family Eating

Routines

The Ps and Cs division of feeding responsibility

Teach to use prompts or cues Parents learn the Ps and Cs: Parents are encouraged to Plan, Prepare and Provide. Children are encouraged to Choose (whether, what and how much to eat) [49].

Mealtime strategies to encourage vegetable consumption

Prompt intention formation Parents decide which activities they will attempt in the coming week.

Provide general encouragement

Interviewers provide positive feedback about any helpful practices occurring in the home.

Role-modelling of fruit and vegetable consumption

Prompt identification as a role model

Parents are provided information about their importance in role-modelling fruit and vegetable consumption. Their consumption is compared with national nutrition recommendations. Tailored feedback is provided.

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 7 of 12

a) Availability and accessibility of fruit and vegetables [10,47] The telephone intervention encourages parentsto ensure that fruit and vegetables are available and acces-sible in the home and that they are prepared, presented ormaintained in a ready-to-eat form that encourages theirconsumption [48]. This could include offering cut-uppieces of fruit or vegetable at snack times, and ensuringfruit is visible by storing it in fruit bowls.b) Supportive family eating routines The interventionwill seek to improve parent knowledge and facilitate theacquisition of skills to support parents to eat meals as afamily [12] without the television on [13], establish andenforce family rules about eating [11] and developboundaries regarding when and how food is offered totheir children [49].c) Parental role-modelling of fruit and vegetable consumption [11] Parents will be encouraged to increasethe number of serves of fruit and vegetables that theyconsume in front of their children and to express sup-portive attitudes toward the consumption of fruit andvegetables to their children, for example, by making posi-tive and encouraging comments.

Participants will also be asked to undertake homeworkactivities to encourage them to apply, directly into theirhome environment, the strategies and information cov-ered in the telephone calls. Incorporating homeworkassignments into health behaviour interventions has beenfound to increase the size of the intervention effect [50].Homework activities will be optional and tailored to theneeds of the participant, based on recommended homefood environment practices not currently undertaken bythe participant.Intervention resourcesBased on evidence indicating telephone-based dietaryinterventions are more effective when used in conjunc-tion with print and other resources [21], all interventionparticipants will be mailed resource kits following com-pletion of the baseline survey. The kit comprises a partic-

ipant workbook containing information and activities, apad of meal planners, and a cookbook including recipeshigh in fruit and vegetables. The resources will be used tofacilitate participant engagement in the telephone sup-port calls and assist participants to complete interventionactivities between telephone contacts.Conceptual modelThe telephone-based intervention accords with themodel of family-based intervention proposed by Golanand colleagues [51] in the treatment and prevention ofchildhood obesity. Their model, which draws upon socio-ecological theory, focuses on introducing new familialnorms associated with healthy eating. This is achievedthrough making changes within the home food environ-ment, providing positive parental role-modelling andincreasing parenting- and nutrition-related knowledgeand skills. Interventions based on such a model have beenshown to be effective in bringing about environmentalchanges in participants' homes to support healthy eating[52] and in reducing poor eating habits of overweight andobese children of participants [53].

The intervention utilises a number of specific behav-iour change techniques to initiate the change process asdescribes in Table 1. The third column lists the behaviourchange techniques used and the fourth column links eachtechnique to its application in the context of the topiclisted in column 2. These behaviour change techniquesinclude prompting intention formation, barrier identifi-cation, specific goal-setting and the reviewing of suchgoals, self-monitoring of behaviour and identification as arole-model, teaching to use prompts or cues, and provid-ing general encouragement, as described in the taxonomyproposed by Abraham and Michie [54].Intervention personnel, recruitment and trainingConsistent with other telephone-based health behav-ioural interventions [20,21], intervention support will bedelivered by trained telephone interviewers. Interviewersdelivering the intervention will have experience in con-

WEEK 4Availability and Accessibility

Parental role-modelling, Supportive Family Eating

Routines

Review of weeks 1-3 Provide general encouragement

Interviewers provide positive feedback about any helpful practices occurring in the home

Planning for the future and dealing with difficult situations

Prompt barrier identification Parents are encouraged to identify barriers that will prevent them implementing what they have learnt and to generate solutions.

Review of goals Prompt review of behavioural goals

Parents review their program goal, evaluate their progress and identify how they can maintain the change

Table 1: Overview of intervention call content: behaviour change techniques and their application (Continued)

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 8 of 12

ducting health-related telephone surveys, but have noformal qualifications in psychology, dietetics, parenting,health promotion or other health professions. The use oftelephone interviewers without specialist skills may meanthat adoption of this intervention by government agen-cies is more feasible. Interviewers without specialist skillshave previously been found to be effective in improvingother health behaviours [20]. If effective in this context,their use may facilitate the adoption of this type of inter-vention where use of specialist staff may not be feasibledue to cost and the shortage of staff with such skills.

To recruit suitable staff and to equip them with the nec-essary knowledge and skills to deliver the intervention, apool of potential telephone interviewers was invited toattend a two-day training workshop. The training wasdeveloped and delivered by a registered dietitian, a clini-cal psychologist specialising in parenting, and health pro-motion practitioners (with post-graduate qualificationsand experience in public health). The research team andclinical psychologist judged interviewer competency,based on the completion of role-plays [55] and smallgroup exercises during training, and those consideredsufficiently competent were selected to deliver the inter-vention. The selected interviewers were then required tocomplete a further minimum 10 hours of self-paced prac-tice, including script and workbook familiarisation. Theywere also required to practise each script with a memberof the research team to ensure that required levels ofcompetency and adherence had been met [55] and thatthey were able to deliver the script in a confident, conver-sational style and respond appropriately to participantqueries.

During the first two months of intervention delivery, allinterviewers will participate in fortnightly group supervi-sion, facilitated by a psychologist. A self-regulatorymodel of peer supervision [56] will be utilised to facilitatelearning, improve interviewer performance and helpstandardise intervention delivery. Members of theresearch team will monitor the supervision sessions andprovide feedback as required.Intervention monitoringTo ensure integrity of intervention delivery during thetrial, members of the research team will have weekly con-tact with interviewers to keep abreast of common issuesand concerns so that they may be addressed in a consis-tent manner. During each four-week batch of telephonecalls, members of the research team will monitor at leasttwo completed calls made by each interviewer to assessadherence with the intervention protocol. Specifically,the research team member will record whether the inter-viewer covers the key themes and information for eachcall, the extent to which the interviewer deviates from thescript, the length of the call and whether the intervieweradequately answers any questions asked.

The records of the recruitment coordinator will beaudited following the recruitment of each batch of partic-ipants. A separate member of the research team willreview the dates on which allocation letters are mailed.They will also review the attempt dates, receipt dates andcompletion dates of intervention and data collection tele-phone calls for each trial participant. This periodicreview of documentation will assess whether the inter-vention is progressing in a timely manner and in accor-dance with the study protocol [57].

Control GroupParticipants allocated to the control group will receive a22-page booklet, 'The Australian Guide to Healthy Eat-ing: Background information for consumers' [28]. This isa national food guide published by the Australian Gov-ernment Department of Health and Ageing. This publica-tion will be posted to parents' residential addressesfollowing completion of the baseline survey.

Data Collection and MeasuresBaseline and follow-up data will be collected through aCATI survey administered to all participants. The surveywill take approximately 30 minutes to complete. Data col-lection interviewers will be provided with training toensure that they understand and adhere to data collectionprotocols, and to practise the survey script.

Baseline data will be collected one to two weeks prior tointervention delivery. Calls will be monitored for adher-ence to the training protocol. Members of the researchteam will monitor approximately ten percent of the firstbatch of baseline calls and compare the delivery of thesurvey to the script as written. Any deviations from theprotocol will be addressed with the interviewer immedi-ately following the completion of the call. Each inter-viewer will then be monitored at least once in eachsubsequent batch of surveys to ensure consistency overtime. The survey administered at baseline will berepeated at four time points: two, six, 12 and 18 monthsfollowing baseline data collection. To minimise attrition,prior to follow-up data collection calls at six, 12 and 18months, participants will receive letters thanking themfor their participation to date and reminding them thatthey will shortly be telephoned to participate in follow-upphone calls [58].

Data collection interviewers will not participate in trialrecruitment or intervention delivery and will be blind toparticipant group allocation. Furthermore, during eachfollow-up data collection interview, participants will beasked not to disclose their group allocation to the inter-viewers at the start of the telephone survey. To assess theeffectiveness of the blinding, following the collection oftrial outcome data, interviewers will be asked to nomi-

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 9 of 12

nate the groups to which they believe the participantswere allocated [59].

MeasuresDemographicsDemographic items regarding parents' gender, age,Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, educa-tion, income, postcode and household composition (e.g.the number of children in the household), as well as ques-tions regarding the child's gender and age, will beassessed at baseline. Items used to assess demographicswill be sourced from the NSW Health Survey Program, aregular government behavioural risk factor surveillancesurvey [60].Process measuresThe CATI system will record information regarding theoutcome of each attempted call (e.g. engaged, answeringmachine, call-back arranged, call partially complete, callcomplete or refusal), the interviewer who attempted thecall, the date and time of the attempt, the call durationand the responses provided by the participant throughoutthe call. During intervention delivery calls, participantswill be asked whether they received the interventionresources and what homework activities they attempted.This will allow for an assessment of the extent to whichthe intervention was delivered and received as planned.Primary outcome measure: fruit and vegetable consumptionThe primary outcome is the change in the fruit and vege-table intake of the preschool children. Fruit and vegetableintake will be assessed using the fruit and vegetable sub-scale of the Children's Dietary Questionnaire. This ques-tionnaire was developed to assess Australian children'sdietary patterns in relation to current national guidelinesand has been recommended for use in assessing the effi-cacy of interventions to improve children's eating habits[61].

This semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaireasks parents to report the frequency and variety of foodsconsumed by their children over the previous seven daysand the previous 24 hours. Scores on the fruit and vegeta-ble subscale range from 0 to 28, with a score of 14 recom-mended based on current national dietary guidelines[61]. A one-point increase on this subscale could equateto, for example, a child consuming on average an addi-tional type of fruit or vegetable each day (variety), or con-suming fruit or vegetables at an additional eatingoccasion each day (frequency). An increase of this magni-tude of fruit and vegetable variety or frequency of con-sumption is consistent with effect sizes of fruit andvegetable consumption reported in previous child fruitand vegetable interventions, and has the potential to havesignificant public health impact [62]. Reliability and valid-ity of this tool has been established using multiple sam-ples of Australian children, including preschoolers [61].

The fruit and vegetable subscale was found to be inter-nally consistent (� = 0.76), reliable (intra-class correlationcoefficient = 0.75) and valid as assessed against a seven-day food checklist (Spearman's correlation coefficient =0.58) [61].Sample sizeA sample size of approximately 300 participants (150 pergroup) at the 18-month follow-up will allow a detectabledifference between intervention and control groups of1.27 on the fruit and vegetable subscale of the Children'sDietary Questionnaire, with 80% power at the 0.05 signif-icance level. This sample size accounts for the effect ofclustering by assuming an interclass correlation coeffi-cient of 0.03 (unpublished data from the Good for Kidsprogram) and assumes 10 participants per preschoolremain at the 18-month follow-up (as explained below).

Four hundred participants will be required to berecruited at baseline to achieve the desired sample of 300at the 18 month follow-up. Based on preschools caringfor an average of 27 children each day [34], and assumingchildren attend preschool for an average of 2.8 days perweek (i.e. 17 hours over 6-hour long days), it is expectedthat up to 48 parents of children, on average, will be eligi-ble to participate in the trial from each consenting pre-school. A parent participation rate of 30% [19] will yieldapproximately 14 parents per preschool at baseline, ofwhom 10 will remain at 18 months, assuming a 25% attri-tion rate [63]. It is thus estimated that 30 preschools willbe required to generate a sample of 300 parents at theconclusion of the trial.Statistical analysis: primary outcomeAll statistical analyses will be performed with SAS (ver-sion 9.2 or later) statistical software.

To assess the initial impact of the intervention and theextent to which any intervention effect is maintained inthe longer term, the primary outcome analyses for thetrial will be conducted on participant scores on the fruitand vegetable subscale of the Children's Dietary Ques-tionnaire collected at the two-month and 18-month fol-low-up time periods. For the primary outcome analyses,an alpha value of 0.05 will be utilised to determine statis-tical significance.

Outcome data will be analysed using general estimatingequations based on the intention-to-treat principle,where participants are analysed based on the groups towhich they were allocated, regardless of the treatmenttype or exposure that they actually received [64]. Generalestimating equation models will account for any cluster-ing effect of preschools. To ensure the results of the pri-mary analysis are robust against the missing dataassumption of the general estimating equation, a sensitiv-ity analysis will be performed whereby participants'observations at baseline will be used as a substitute forsubsequent missing data. A per-protocol analysis will also

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 10 of 12

be conducted whereby outcome data will only beincluded in analyses if participants received and com-pleted all four telephone support calls. Conducting bothintention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses is recom-mended when assessing trial outcomes [64].

DiscussionTo the authors' knowledge, this is the first randomisedcontrolled trial to evaluate a telephone-based parentintervention to increase the fruit and vegetable intake ofpreschool-aged children. The intervention has beendeveloped to maximise the likelihood of having a positiveeffect on fruit and vegetable consumption through theuse of a relevant conceptual model during interventiondevelopment, and employing specific behaviour changestrategies to target characteristics of the home food envi-ronment known to be associated with increased fruit andvegetable intake.

The study demonstrates many strengths: the experi-mental randomised design; the implementation of proce-dures to reduce potential threats to internal validity, suchas the blinding of data collection interviewers and com-puter-based randomisation of groups undertaken by anindependent statistician; the use of an outcome measurewith established validity and reliability; and the recruit-ment of study participants from a setting which most 4-year-old children attend on multiple days of the week. Iffound to be effective, an intervention of this intensity,utilising trained staff rather than experienced health pro-fessionals, is considered to have the potential to be imple-mented on a community-wide basis, as currently existsfor adult risk behaviours [20].

ConclusionThis manuscript provides a comprehensive description ofthe study methods to be employed as part of a ran-domised controlled trial of a telephone-based parentintervention to increase the fruit and vegetable intake ofchildren aged 3 to 5 years. The successful implementationof this trial will provide strong evidence on which to basejudgements regarding the efficacy of this interventionapproach.

Competing interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributionsAuthor RW led the development of this manuscript. Author LW conceived theintervention concept and secured the funding source. Authors RW, AF, LW andLB contributed to the development of the intervention scripts and printedmaterial. Authors LW, KC, RW and JW determined the measures to be used andthe analyses to be conducted. All authors contributed to the research designand trial methodology and contributed to, read and approved the final versionof this manuscript.

AcknowledgementsThis trial is funded from a Cancer Institute New South Wales grant with in-kind support provided by Hunter New England Population Health. We wish to thank the Program Advisory Group, Dr Rebecca Golley and the Hunter Medical Research Institute.

Author Details1School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia, 2Hunter New England Population Health, Newcastle, Australia, 3School of Psychology and Psychiatry, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, 4Centre for Physical Activity & Nutrition Research, School of Exercise & Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia and 5School of Psychology, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia

References1. Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M: The global burden

of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2005, 83(2):100-108.

2. Ministry of Health: The Health of New Zealand: Total population. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2004.

3. Allender S, Peto V, Scarborough P, Boxer A, Rayner M: Diet, physical activity and obesity statistics. London: British Heart Foundation; 2006.

4. Yngve A, Wolf A, Poortvliet E, Elmadfa I, Brug J, Ehrenblad B, Franchini B, Haraldsdottir J, Krolner R, Maes L, et al.: Fruit and vegetable intake in a sample of 11-year-old children in 9 European countries: The Pro Children Cross-sectional Survey. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 2005, 49(4):236-245.

5. Magarey A, McKean S, Daniels L: Evaluation of fruit and vegetable intakes of Australian adults: the National Nutrition Survey 1995. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 2006, 30(1):32-37.

6. Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Preventative Health National Research Flagship, The University of South Australia: 2007 Australian National Children's Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey: Main Findings. 2008.

7. World Health Organisation: World Health Report 2002 - Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva: WHO; 2002.

8. Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J: Longitudinal changes in diet from childhood into adulthood with respect to risk of cardiovascular diseases: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. European journal of clinical nutrition 2004, 58:1038-1045.

9. Benton D: Role of parents in the determination of the food preferences of children and the development of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004, 28(7):858-869.

10. Blanchette L, Brug J: Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6-12-year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. J Hum Nutr Diet 2005, 18(6):431-443.

11. Pearson N, Biddle SJ, Gorely T: Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public health nutrition 2009, 12(2):267-283.

12. Cooke LJ, Wardle J, Gibson EL, Sapochnik M, Sheiham A, Lawson M: Demographic, familial and trait predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption by pre-school children. Public health nutrition 2004, 7(2):295-302.

13. Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL: Relationships between use of television during meals and children's food consumption patterns. Pediatrics 2001, 107(1):E7.

14. Omar MA, Coleman G, Hoerr S: Healthy eating for rural low-income toddlers: caregivers' perceptions. Journal of community health nursing 2001, 18(2):93-106.

15. Haire-Joshu D, Elliott MB, Caito NM, Hessler K, Nanney MS, Hale N, Boehmer TK, Kreuter M, Brownson RC: High 5 for Kids: the impact of a home visiting program on fruit and vegetable intake of parents and their preschool children. Preventive medicine 2008, 47(1):77-82.

16. Klohe-Lehman DM, Freeland-Graves J, Clarke KK, Cai G, Voruganti VS, Milani TJ, Nuss HJ, Proffitt JM, Bohman TM: Low-income, overweight and obese mothers as agents of change to improve food choices, fat

Received: 19 March 2010 Accepted: 28 April 2010 Published: 28 April 2010This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216© 2010 Wyse et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 11 of 12

habits, and physical activity in their 1-to-3-year-old children. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2007, 26(3):196-208.

17. Havas S, Anliker J, Damron D, Langenberg P, Ballesteros M, Feldman R: Final results of the Maryland WIC 5-A-Day Promotion Program. American journal of public health 1998, 88(8):1161-1167.

18. Wolman J, Skelly E, Kolotourou M, Lawson M, Sacher P: Tackling toddler obesity through a pilot community-based family intervention. Community Pract 2008, 81(1):28-31.

19. Wolfenden L, Bell AC, Wiggers J, Butler M, James E, Chipperfield K: Engaging parents in child obesity prevention: support preferences of parents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health in press.

20. Ossip-Klein DJ, McIntosh S: Quitlines in North America: evidence base and applications. The American journal of the medical sciences 2003, 326(4):201-205.

21. Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Vandelanotte C, Owen N: Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine 2007, 32(5):419-434.

22. Pierce JP, Newman VA, Flatt SW, Faerber S, Rock CL, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Gold EB, Hollenbach KA, Wasserman L, et al.: Telephone counseling intervention increases intakes of micronutrient- and phytochemical-rich vegetables, fruit and fiber in breast cancer survivors. The Journal of nutrition 2004, 134(2):452-458.

23. Newman VA, Flatt SW, Pierce JP: Telephone counseling promotes dietary change in healthy adults: results of a pilot trial. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2008, 108(8):1350-1354.

24. Djuric Z, Vanloon G, Radakovich K, Dilaura NM, Heilbrun LK, Sen A: Design of a Mediterranean exchange list diet implemented by telephone counseling. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2008, 108(12):2059-2065.

25. Australian Bureau of Statistics: Australian Social Trends 2001 (4102.0). Canberra: ABS; 2001.

26. Eakin EG, Reeves MM, Lawler SP, Oldenburg B, Del Mar C, Wilkie K, Spencer A, Battistutta D, Graves N: The Logan Healthy Living Program: A cluster randomized trial of a telephone-delivered physical activity and dietary behavior intervention for primary care patients with type 2 diabetes or hypertension from a socially disadvantaged community -- Rationale, design and recruitment. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2008, 29:439-454.

27. Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG: CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004, 328(7441):702-708.

28. Kellett E, Smith A, Schmerlaib Y: The Australian Guide to Healthy Eating: Background information for consumers Adelaide: Children's Health Development Foundation; 1998.

29. Population Health Division: The health of the people of New South Wales - Report of the Chief Health Officer. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2006.

30. Australian Bureau of Statistics: 2006 Census of Population and Housing. Canberra: ABS; 2007.

31. Australian Bureau of Statistics: Childhood education and care (4402.0). Canberra: ABS; 2009.

32. Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision: Report on Government Services 2009, Volume 1: Early Childhood, Education and Training; Justice; Emergency Management. Canberra: Productivity Commission; 2009.

33. Preschool Education in Australia [http://www.aph.gov.au/library/Pubs/BN/2007-08/PreschoolEdAustralia.htm#]

34. Wolfenden L, Neve M, Farrell L, Lecathelinais C, Bell AC, Milat A, Wiggers J: Physical activity policies and practices of childcare centres in Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health in press.

35. Good for Kids. Good for Life [http://www.goodforkids.nsw.gov.au]36. Wolfenden L, Kypri K, Freund M, Hodder R: Obtaining active parental

consent for school-based research: a guide for researchers. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 2009, 33(3):270-275.

37. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, Kwan I: Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ 2002, 324(7347):1183.

38. Campbell MK, Mollison J, Steen N, Grimshaw JM, Eccles M: Analysis of cluster randomized trials in primary care: a practical approach. Family Practice 2000, 17(2):192-196.

39. Campbell K, Crawford D, Jackson M, Cashel K, Worsley A, Gibbons K, Birch LL: Family food environments of 5-6-year-old-children: Does socioeconomic status make a difference? Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr 2002, 11(Suppl):S553-S561.

40. Australian Bureau of Statistics: Socio-economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) - 2033.0.55.001 - 2006. Canberra: ABS; 2008.

41. Australian Bureau of Statistics: An introduction to SocioEconomic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). CAT no 2039.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

42. McEntegart DJ: The pursuit of balance using stratified and dynamic randomization techniques: An overview. Drug Information Journal 2003, 37:16.

43. Green BB, McAfee T, Hindmarsh M, Madsen L, Caplow M, Buist D: Effectiveness of telephone support in increasing physical activity levels in primary care patients. American journal of preventive medicine 2002, 22(3):177-183.

44. Elley CR, Kerse N, Arroll B, Robinson E: Effectiveness of counselling patients on physical activity in general practice: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003, 326(7393):793.

45. Choi BC: Computer assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) for health surveys in public health surveillance: methodological issues and challenges ahead. Chronic Diseases in Canada 2004, 25(2):.

46. Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS: A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2001, 8(2):133-142.

47. Rasmussen M, Krolner R, Klepp KI, Lytle L, Brug J, Bere E, Due P: Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part I: Quantitative studies. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2006, 3:22.

48. Hearn MD, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Smith M, Lin LS, Resnicow K: Environmental influences on dietary behavior among children: Availability and Accessibility of fruits and vegetables enable consumption. Journal of Health Education 1998, 29:26-32.

49. Satter E: Feeding dynamics: Helping children to eat well. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 1995, 9:178-184.

50. Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P: A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: Factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2009, 77(3):486-503.

51. Golan M, Weizman A: Familial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity: conceptual mode. Journal of nutrition education 2001, 33(2):102-107.

52. Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR: Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. The British journal of nutrition 2006, 95(5):1008-1015.

53. Golan M, Fainaru M, Weizman A: Role of behaviour modifcation in the treatment of childhood obesity with the parents as the exclusive agents of change. International Journal of Obesity 1998, 22:1217-1224.

54. Abraham C, Michie S: A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol 2008, 27(3):379-387.

55. Santacroce SJ, Maccarelli LM, Grey M: Intervention fidelity. Nursing research 2004, 53(1):63-66.

56. Sanders MR, Cann W, Markie-Dadds C: The Triple P-Positive Parenting Programme: A universal population-level approach to the prevention of child abuse. Child abuse review 2003, 12(3):155-171.

57. Weijer C, Shapiro S, Fuks A, Glass KC, Skrutkowska M: Monitoring clinical research: an obligation unfulfilled. Cmaj 1995, 152(12):1973-1980.

58. Ribisl KM, Walton MA, Mowbray CT, Luke DA, Davidson WS II, Bootsmiller BJ: Minimizing participant attrition in panel studies through the use of effective retention and tracking strategies: Review and recommendations. Evaluation and Program Planning 1996, 19(1):1-25.

59. Prescott RJ, Counsell CE, Gillespie WJ, Grant AM, Russell IT, Kiauka S, Colthart IR, Ross S, Shepherd SM, Russell D: Factors that limit the quality, number and progress of randomised controlled trials. Health technology assessment 1999, 3(20):1-143.

60. Centre for Epidemiology and Research: 2008 Report on Adult Health from the New South Wales Population Health Survey. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2009.

61. Magarey A, Golley R, Spurrier N, Goodwin E, Ong F: Reliability and validity of the Children's Dietary Questionnaire; A new tool to measure children's dietary patterns. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009:1-9.

62. Knai C, Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M: Getting children to eat more fruit and vegetables: A systematic review. Preventive medicine 2006, 42:85-95.

63. Pignone MP, Ammerman A, Fernandez L, Orleans CT, Pender N, Woolf S, Lohr KN, Sutton S: Counseling to Promote a Healthy Diet in Adults: A

Wyse et al. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216

Page 12 of 12

Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force. American journal of preventive medicine 2003, 24(1):75-92.

64. Porta N, Bonet C, Cobo E: Discordance between reported intention-to-treat and per protocol analyses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2007, 60:663-669.

Pre-publication historyThe pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/216/prepub

doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-216Cite this article as: Wyse et al., A cluster randomised trial of a telephone-based intervention for parents to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in their 3- to 5-year-old children: study protocol BMC Public Health 2010, 10:216