A Business Modelling Framework for the Front End of Innovation

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of A Business Modelling Framework for the Front End of Innovation

IN DEGREE PROJECT DESIGN AND PRODUCT REALISATION,SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS

, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN 2019

A Business Modelling Framework for the Front End of InnovationCustomising a Guiding Material for an Early Phase of the Innovation Process for a Swedish Fintech Company

MARCUS ALMQVIST

CHARLOTTA LUNDBERG

KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGYSCHOOL OF INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT

Ett ramverk för affärsmodellering i ett tidigt skede av innovationsprocessen

Ett skräddarsytt material för en tidig innovationsfas i ett svenskt Fintech-bolag

Marcus Almqvist Charlotta Lundberg

Examensarbete TRITA-ITM-EX 2019:387 KTH Industriell teknik och management

Integrerad Produktutveckling SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM

A Business Modelling Framework for the Front End of Innovation

Customising a Guiding Material for an Early Phase of the Innovation Process for a Swedish Fintech Company

Marcus Almqvist Charlotta Lundberg

Master of Science Thesis TRITA-ITM-EX 2019:387 KTH Industrial Engineering and Management

Integrated Product Design SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM

Examensarbete TRITA-ITM-EX 2019:387

Ett ramverk för affärsmodellering i ett tidigt skede av innovationsprocessen

Charlotta Lundberg

Marcus Almqvist Godkänt

2019-juni-07

Examinator

Sofia Ritzén

Handledare

Sofia Ritzén

Sammanfattning Det svenska Fintech-bolaget som behandlas i denna masteruppsats har föreslagit en process genom vilken alla nya idéer ska gå igenom innan dess genomförbarhet testas i en ’Proof-of-Concept’. Denna process är på företaget kallad ‘Proof-of-Concept-processen’. Idag finns det inget material som hjälper och guidar idéägaren genom en av de mer omfattande faserna av processen. Syftet med denna masteruppsats är att utveckla ett material för denna fas. Materialet baseras på en litteraturstudie och kvalitativa intervjuer. De ämnen som ingår i litteraturstudien är: ‘Innovation’, ‘Uncertainty’, ‘Front End of Innovation’ och ‘Business Modelling’. Kvalitativa semi-strukturerade intervjuer utfördes separat med tre av ledningens fyra medlemmar. Kontinuerlig diskussion fördes med företagshandledaren för att facilitera ramverkets utveckling. Resultatet består av två delar, (1) resultaten från intervjuerna med ledningsgruppen som syftar till att ligga till grund för kravspecifikationen på vilka komponenter materialet ska innehålla och (2) ett ramverk för hur affärsmodellering kan ske i detta stadie av innovationsprocessen. Resultatet är ett material med företagets grafiska profil för att det ska kunna bli behandlat som ett internt dokument. En version av materialet som inte har företagets grafiska språk presenteras. Ramverket presenteras tillsammans med en djupare analys av de separata byggstenar som tillsammans utgör dess struktur, samt förslag på tekniker som syftar till att hjälpa användaren av materialet att utveckla sin idé inför nästa utvärderingsmöte och möjliggöra en demokratisering av innovationsprocessen. Ramverkets struktur är ett resultat av inspiration från existerande ramverk samt intervjuerna vilket bidrar till dess anpassning till företagets specifika innovationsprocess. Vi anser att resultatet är ett ramverk för affärsmodellering som beskriver rekommendationer för hur man hanterar de tidiga faserna av innovationsprocessen. Ramverket och dess teoretiska bakgrund är baserat på ett brett utbud av litteratur och författare. Avslutningsvis hävdar vi att ramverket kan betraktas som en bro mellan två relativt unga forskningsområden ’Front End of Innovation’ och ’Business Modelling’ med sitt primära tillämpningsområde på det behandlade företaget. Nyckelord: Innovation, Uncertainty, Front End of Innovation, Business Modelling

Master of Science Thesis TRITA-ITM-EX 2019:387

A Business Modelling Framework for the Front End of Innovation

Charlotta Lundberg

Marcus Almqvist Approved

2019-June-07 Examiner

Sofia Ritzén Supervisor

Sofia Ritzén

Abstract The Swedish Fintech company that is subject to this thesis has proposed a process through which all new ideas should go through before entering the development funnel, called the ‘Proof-of-Concept-process’. Today, there exists no material that helps and guides the idea owner through one of the more extensive phases of that process. The purpose of this thesis is to develop a material for this phase.

The material is developed through a literature review and qualitative interviews. The topics included in the literature review are: ‘Innovation’, ‘Uncertainty’, ‘Front End of Innovation’ and ‘Business Modelling’. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were performed separately with three out of four members of the top management team. Continuous discussions with the industrial supervisor facilitated the development of the framework. The result consists of two parts, (1) the results from the interviews with the management team which aims to lay the foundation for the requirement specification on which components the framework should contain, and (2) a framework for how business modelling can be done at this phase of the innovation process. The result is a material that uses the graphical branding of the company so that it can be treated as an internal document. An unbranded version of the result is presented in this thesis. The framework is presented together with a deeper analysis of the separate building blocks that form its structure, together with suggestions on techniques that aims to help the user of the material. We argue that the result is a business modelling framework that considers recommendations for how to handle the FEI, and that regards theory on business modelling as well as interviews with managers at the subject company to establish what techniques such a framework should include. Further, the result is based on a wide variety of literature and authors. Concluding, we argue that the result can be considered a bridge between two relatively young research areas ‘Front end of Innovation’ and ‘Business Modelling’ with its primary application at one specific company.

Keywords: Innovation, Uncertainty, Front End of Innovation, Business Modelling

PREFACE This section aims to provide the reader with an understanding of the setting in which the thesis is written and serves as a section in which the authors are able to express their thankfulness to those who have contributed to the result.

This thesis is the result of an MSc degree project in Integrated Product Design - Innovation Management & Product Development at the Royal Institute of Technology, performed during the spring of 2019. We would like to aim special thanks to our industrial supervisor at the subject company and to our academic supervisor at the Royal Institute of Technology, Sofia Ritzén, who both have dedicated significant parts of their time and effort to this thesis.

Lastly, we would like to thank the top management at the subject company for welcoming us to perform our master thesis at their company and surrendering their time for the sake of the result.

__________________________________ ___________________________________ Charlotta Lundberg Marcus Almqvist Stockholm, June 2019 Stockholm, June 2019

NOMENCLATURE

Fintech Financial Technology

B2B Business-to-Business

SaaS Software as a Service

CEO Chief Executive Officer

SMEs Small-to-Medium Enterprises

POC Proof-of-Concept

HoSI Head of Strategic Initiatives

BMC Business Model Canvas

Lean BMC Lean Business Model Canvas

NPD New Product Development

FEI Front End of Innovation

FFE Fuzzy Front End

NCD New Concept Development

NPPD New Product and Process Development

TPFEM Triple Phase Front End Model

RBV Resource-Based View

VPC Value Proposition Canvas

TLBMC Triple Layer Business Model Canvas

PPM Project Portfolio Management

RDM Risk Diagnosing Methodology

CTO Chief Technology Officer

MRR Monthly Recurring Revenue

CMO Chief Marketing Officer

R&D Research & Development

MVP Minimum Viable Product

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1

1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Problem Description ....................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Limitations ...................................................................................................................... 4

2 FRAME OF REFERENCE ................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Defining Innovation ........................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Uncertainty ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Front End of Innovation .................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Business Modelling Frameworks ................................................................................... 11 2.5 Concluding Remarks ...................................................................................................... 17

3 METHOD ................................................................................................................... 19 3.1 Action Research ............................................................................................................ 19 3.2 Problem Definition ........................................................................................................ 19 3.3 Frame-of-Reference ...................................................................................................... 19 3.4 Interviews ..................................................................................................................... 20 3.5 Developing a Business Modelling Framework ................................................................ 21 3.6 Supporting Techniques .................................................................................................. 21

4 INTERVIEW RESULTS ................................................................................................. 23 4.1 Head of Sales ................................................................................................................ 23 4.2 Chief Technology Officer (CTO) ...................................................................................... 23 4.3 Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) ...................................................................................... 24

5 THE FRAMEWORK ..................................................................................................... 27 5.1 Structure and Use ......................................................................................................... 27 5.2 Problem ........................................................................................................................ 28 5.3 Solution ........................................................................................................................ 29 5.4 Customer Segment ........................................................................................................ 30 5.5 Value Proposition ......................................................................................................... 32 5.6 Unfair Advantage .......................................................................................................... 33 5.7 Channels ....................................................................................................................... 35 5.8 Resource Analysis ......................................................................................................... 36 5.9 Financial Analysis .......................................................................................................... 37 5.10 Key Metrics ................................................................................................................... 39 5.11 Risk Analysis ................................................................................................................. 41

5.12 Implementation plan .................................................................................................... 42

6 DISCUSSION .............................................................................................................. 43 6.1 Methods Used ............................................................................................................... 43 6.2 Result ........................................................................................................................... 44

7 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................ 49

8 RECOMMENDATIONS & FUTURE WORK .................................................................... 51 8.1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................ 51 8.2 Future Work .................................................................................................................. 52

9 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................. 53

APPENDIX A: THE FEI CANVAS

APPENDIX B: THE FRAMEWORK

1

1 INTRODUCTION This chapter introduces the setting in which this thesis was written, the identified issue, the main purpose of the thesis and the limitations to the both the process for developing the result as well as to the result itself.

1.1 Background The company that is subject to this thesis is a global Swedish Fintech company. It is primarily based in Stockholm and was established in 2010. The financial service industry has, similarly to many other industries, seen the emergence of new technologies disrupting their existing businesses and processes. Businesses that have emerged from such technological disruption have together improved efficiency, enhanced customer experiences and established new ways of creating value for customers. This has formed what is by leading firms called the ‘FinTech Revolution’ (Gomber et al., 2018). Thus, what has been the primary concern of the traditional banking sector is not a lack of new technology, but instead internal resistance to change (Sandberg & Aarikka-Stenroos, 2014). The customers of the subject company are banks and lenders all over the world to whom the company offers a Business-to-Business (B2B) Software as a Service (SaaS). The maturity of the existing processes varies depending on the department. There are approximately 30 employees at the Stockholm office, where the marketing, sales, and data team are over-represented. The organisational structure is flat with a top management team with representatives from the marketing, sales, and data team, including the Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The Head of Strategic Initiatives (HoSI) represents the strategy team together with interns, and work closely with all the teams all over the organisation in order to collect necessary data for their development projects. The company is rapidly growing thanks to their service-based business and is reaching a level of maturity in which established processes for the activities related to innovation and to the early stages of new product and process development are becoming desirable. The company has no explicit or articulated innovation strategy. Based on observations, the company practises a technology-driven innovation strategy, as most projects and ideas that enter the company’s funnel for new projects share the characteristic of being new applications of existing technology.

It can be seen as detrimental for small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) to spend time on implementing a standardised process for innovation as most core activities at such stages involve finding and developing a market fit. However, regardless of the size, age and maturity of a company, studies show that some resources should be allocated towards adjacent and radical innovation to achieve long term competitive advantage (Nagji & Tuff, 2012). Burgelman (1983) explained that organisations can create processes for generating entrepreneurial activity on a continuous basis. Christensen & Overdorf (2000) highlighted that a company who establishes processes and strategies in their early years and before massive scaling will more likely be organisationally successful during growth as the established processes are seen as the natural way to work by the employees. During the subject company’s growth, a consensus about long term commitment to establishing organisational processes has formed. Consequently, efforts towards creating a process to standardise the early stages of innovation have been made. The result of those efforts has been a proposal for an innovation process for project planning and development which has not yet been fully implemented, called the ‘Proof-Of-Concept (POC)-process’.

2

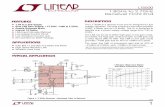

The intent of implementing such a process was to standardise and state the deliverables and requirements that the management team has on new innovation to facilitate the research work during new project developments. The process has been developed by the strategy team, the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) from the top management team and one of the product owners. The reason behind the half-hearted implementation of the process is most likely due to a lack of commitment and understanding of direct value for the other departments. The process has a linear structure with iterative elements during the ‘Formulating’-phase, with decision points where blessing/halt decisions are recurring events, see Figure 1. The process starts with an idea entering the ‘Idea’-phase. Ideas that regard activities in specific functions and that require little resources to perform are discussed with the respective manager. Finding new applications for existing technology is the main responsibility of the strategy team. The ideas spring from internal interaction and communication, as well as through interaction with external actors such as potential strategic partners who have recognised the potential that the company’s technology possesses for their business. The idea owner gets permission from the closest manager to structure and articulate thoughts around the hypothesis. The second phase is called ‘Exploration’ and is used to develop a Lean Business Model Canvas (Maurya, 2012), with mandated time from the closest supervisor during a period that is up to two weeks. The third phase is a decision point called management reviewal where the idea is pitched. The management gives their blessing or halt for the initiative based on the provided material and the current project portfolio. Their goal is to have all canvases internally stored to have an idea bank of halted initiatives if the future proves to be a better suiting period for realisation of certain ideas.

Figure 1. Unbranded version of the company’s POC-process.

If the idea receives a blessing from management, a more thorough review of the initiative with commercial, technical and stakeholder analysis is to be presented to management, which is called a ‘Strategic & Product Analysis’. This is a more extensive and holistic overview for management to make a decision on for further sanction/follow-up/homework. However, the deliverable is not yet supposed to be a fully developed business plan. Two weeks will be dedicated to this phase of the process. Thereafter, another decision point called the ‘Management Presentation’ takes place. Here, a decision will be made based on the generated material since the last decision point. A promising ‘Formulating’-phase will result in the need for a project plan, which should be developed during a period of two weeks. Prior to the start

3

of this collaboration, the management has expressed that the material related to this phase should outline a go-to approach, stakeholder involvement, required buy-in, possible design requirements and required company commitment. Further, it should include a brief analysis of next steps (i.e. explaining the capacity to commercialise the initiative in a timely manner after a successful POC.

The deliverable from the phase latter to the ‘Formulating’-phase is a project plan. The management reviews the project plan before the POC is performed, and it should contain clear descriptions on how to practically solve problems with budget and scope. The dedicated time for the ‘POC’-phase is estimated to be one to four months and the results should be presented to the management with analysis and an updated project plan, including budget and resources needed. If the project still suits the company’s portfolio, the project will get its final blessing and enter the development phase. To optimise the management meetings and the meetings for decisions points, the management should receive the material at least two working days prior to the review and are obliged to read it in advance.

1.2 Problem Description The effort of developing a standardised process for innovation was partly initiated to enable ideas from all employees, not only from the strategy team. The strategy team is overloaded with work as they are currently tasked with doing all innovative work related to the activities in the POC-process. This includes investigating potential new markets, new offers for existing customers, deciding on project scopes etc. The only exception is for activities that are presented to management as requiring additional resources in an ad hoc manner. Management would like to offer all employees the same chance to put forward their ideas. The POC-process intends to allow any employee of the firm to ideate and progress new ideas through the process with the help of their individual knowledge and capacity. However, implementing the POC-process would initially results in unfair prerequisites because the strategy team are more used to developing new ideas. Their presented material can thus contain more of the elements that the management team looks at when evaluating ideas, in comparison with other idea owners within the company. This is because the members of the strategy team are more familiar with what the management team require to be presented and asks for. These unfair prerequisites result in differences in the material presented for decision-makers at the company depending on who has been in charge of the research work. This is problematic for the individual’s motivation. Not being able to contribute with your ideas, skills and knowledge to the company can come at the cost of motivation for going through the hassle of presenting your ideas. For the company, there is consequently a risk of missing out on ideas that could have proved to be the best choice of ideas to pursuit for the company’s success. There is of course a chance that the ideas will surface eventually through alternative sources of expression, but not having a POC-process that democratises the way ideas are developed could mean losing out on opportunities that are favoured by timing or trends. Currently, there exists no material that helps any idea owner in progressing the project through the ‘Formulating’-phase and for presenting the results that should meet the idea evaluation criteria. There is a need for a material that can provide more information about the project than a Lean Canvas in the phase ‘Exploration’ but that is not as extensive as the deliverable Project Plan of the phase ‘Project Plan’.

The evaluation criteria that management uses to assess projects at the decision points are not formally articulated to the idea owner. This causes a gap between the information that is desired to base a decision upon and what the idea owner presents at decision points. The management

4

team struggle with what techniques to suggest to idea owners when progressing innovation projects through the POC-process.

1.3 Purpose The purpose is to create a material that is tailored to the ‘Formulating’-phase of the company’s proposed innovation process with regards to the wishes of top management and best practices. Further, the purpose is to articulate what factors affect top management’s decision making. This should be done in order to know what areas to investigate when developing a new product or service. The material should guide the organisation’s members in progressing any ideas through the ‘Formulating’-phase to prepare them for presenting to management and hopefully proceed to the next phase of developing a project plan. Helpful techniques for developing and presenting an idea should also be presented in this material so that as many employees as possible have the opportunity to meet the management’s requirements. It should also aid in communicating which are the most uncertain hypotheses related to a project. The result should use the graphical branding of the company and be treated as an internal document. However, an unbranded version of the result will be presented in the thesis.

1.4 Limitations The result of this thesis should only act during the ‘Formulating’-phase and not include developing a full project plan. Suggestions for improvement of the other phases (e.g. idea generation methods) or changes to the structure of the proposed process for innovation should neither be included in this work per request from the company. Further, the HoSI has dedicated significant resources in terms of time and knowledge for this initiative, but made it clear that there would be limitations to the amount of time that could be demanded from management and other employees.

5

2 FRAME OF REFERENCE The frame-of-reference describes literature on innovation as a result, innovation as a process and innovation in practice and their relevance to the problem at hand. These areas were chosen as they all are in the domain of the problem description and the purpose of the research initiative.

2.1 Defining Innovation Different types of innovations are generally tricky to define within a company since there might be many different perspectives on what innovation is. This holds true even within departments. This might be an effect of the wide variety of definitions on innovation in literature. Therefore, defining innovation serves an important part in determining a common language throughout the thesis and within the company. Nagji & Tuff (2012) presented an innovation ambition matrix, which acts as a framework to label and distinguish between different types of innovation, see Figure 2. The framework makes use of two dimensions to describe the innovation as a phenomenon. These two dimensions can both be found in definitions by other authors but has not been used to describe innovation together. The market dimension ‘Where to Play' indicates that innovation is allowed to not only occur through technology development or new products, but also through changes in position with regards to the external environment. The dimension of ‘Where to Play’ is an important indicator to the nature of an innovation within the subject company. Meanwhile, the dimension ‘How to Win’ still implies that the level of novelty to product- and technology development contributes as an important element in the labelling of innovation. The difference between core-, adjacent- and transformational innovation is thus always with regards to the firm and does not exclude innovations that are new to the firm, but not necessarily new to the market in the definition of adjacent- and transformational innovation.

To maintain consistency throughout the thesis, when discussing different types of innovation for the result, core-, adjacent- and transformational innovation will be used, following Nagji & Tuff (2012).

6

Figure 2. The Innovation Ambition Matrix (Nagji & Tuff, 2012).

Veryzer (1998) distinguished several characteristic definitions from different authors with different wording but similar meaning. In general, the largest difference between incremental and radical innovations seem to regard the degree of risk related to an innovation and the amount of uncertainty that needs to be dealt with, especially technological uncertainty (ibid.). O’Connor & Rice (2013) explained that to sustain a long-term competitive advantage mature firms must engage in the development of radical innovations in order to build and dominate fundamentally new markets. They defined radical innovations as “those that senior management believe exhibit the potential to produce one or more of the following: (1) an entirely new set of performance features, (2) improvements in known performance features of five times or greater, or (3) a significant (30% or greater) reduction in cost” (p. 2, 2013). This excludes innovations that are new to the firm but not new to the market, in contrast to the differences between innovations explained by Nagji & Tuff (2012).

2.2 Uncertainty As mentioned, many of the definitions on innovations consider different levels of uncertainty as the factor that separate core- from transformational innovation, like O’Connor & Rice (2013). In their study, nearly all companies who participated agreed that innovation projects are related to high levels of uncertainty. Kihlander & Ritzén (2012) supported this by explaining that the early parts of a development process, which are characterised by a high degree of uncertainty, is primarily about managing uncertainty. Veryzer (1998) argued that one can reduce uncertainties related to market acceptance and value creation by adoption of a formal process for new product development that favours radical innovation, and that a high degree of uncertainty requires iterative processes. O’Connor & Rice (2013) proposed a framework that organisations can use to manage uncertainty in transformational innovation projects that are distinguished by their degree of uncertainty, see Figure 3. The framework is based on a study of 12 radical innovation projects where the uncertainties that the studied projects encountered were categorised. Further, the framework involves the latency (whether the uncertainties were anticipated or unanticipated)

7

and the criticality (is this uncertainty routinely encountered or is it a ‘showstopper’?) of each project. The framework is described as highly dynamic as the uncertainties of a project are subject to rapid changes as a consequence of learning.

Figure 3. Framework for managing uncertainty (O’Connor & Rice, 2013).

It was further argued that the uncertainties surrounding radical innovation span over all four categories of uncertainty and that their criticality changes over time. The primary use of this framework is described as strategic in order to select project managers for major innovations that have demonstrated that they can manage the most critical categories of uncertainties. Together with the framework, O’Connor & Rice (2013) developed a set of questions related to each uncertainty category. Implementing risk management that aims to reduce risks related to uncertainty throughout the innovation processes has proved to reduce complexity of developing new business models in a case study performed on a Danish company by Taran et al. (2013). Cooper (2008) suggested in his ‘New Generation Stage-Gate process’ to divide risk into three paths dependent on the level of risk a project holds. The higher the risk, the more stages and gates are suggested to increase the control of the project and thereby a project can be killed at any time, before too much money has been wasted (ibid.). This could be perceived as contradicting to other literature, but Cooper (2008) argued that a more formal process for higher risk projects should not restrict the work in between the gates, only increase the overview for the gatekeepers. However, there is generally little research done on the incorporation of risk management within business model innovation (Taran et al., 2013).

2.3 Front End of Innovation Evidence of the importance of innovation to any company’s long-term success has frequently been presented in the past decades (Burgelman, 1983; Gutiérrez & Magnusson, 2014; Schilling, 2017; Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996; Amabile, 1997). Any firm that aims to compete on innovation needs to master all phases of the NPD process (Khurana & Rosenthal, 1998). Veryzer (1998) argued that having a formal NPD process that favours radical innovation reduces uncertainties related to market acceptance and value creation. In contrast, arguments have been made that the formalisation of NPD processes might be detrimental to the success of radical innovations and should typically be implemented after the Front End of Innovation (FEI) (Griffin et al., 2014). How companies should structure their NPD processes has been a

8

frequently discussed topic. Models such as ‘Stage-Gate’ (Cooper, 2008), have been developed and frequently adopted in practice. However, there is no solution that fits all organisations. This makes it difficult to establish a standardised process for uncertainty reduction in early stages of NPD that suits all types of organisations. The three phases of the innovation process are the Fuzzy Front End (FFE), the NPD process and Commercialization, see Figure 4 (Koen et al., 2002). The FFE is often known as the FEI and is the definition of the early stages of innovation that will be used throughout this thesis (Martinsuo & Poskela, 2011).

Figure 4. The three parts of the innovation process (Koen et al., 2002).

There are three models that are most frequently referred to in the FEI literature (Pereira, 2017). These are (1) the ‘Stage-Gate’ process (Cooper, 1988; 2008), (2) the ‘Triple Phase Front End Model’ (Khuran & Rosenthal, 1997), and (3) the ‘New Concept Development’ (NCD) (Koen et al., 2001). FEI is defined by Koen et al. (p. 46, 2001) as “those activities that come before the formal and well-structured New Product and Process Development (NPPD) or Stage-Gate process”. However, the FEI is part of the NPPD and the distinction between them can be seen as a continuum. The differences between the two lies in the level of structure as the front end tend to be more chaotic and unstructured compared to the more structured and formal NPPD (Koen et al., 2001; 2002). Further, Koen et al. (2001) explained that the activities that come before, or in the early stages of an NPD process, form the FEI. Eling & Herstatt (2017) explained that the FEI refers to the very first phase of NPD, starting with opportunity discovery and ending with a go-decision for developing a new product. The go-decision marks when significant resources are committed so that development can start. This is similar to the last blessing/halt decision of the POC-process. The importance of the FEI’s success to NPD was described 30 years ago by Cooper & Kleinschmidt (1987) and that it serves as the foundation for generating successful NPD has been recognised by others since (Cooper, 2008; Martinsuo & Poskela, 2011; Kock et al., 2015). The activities included in the FEI are opportunity identification, problem identification, opportunity/problem analysis, and matching; market and technology analysis; idea generation, evaluation, and screening; concept development, evaluation, and testing; requirement definition; and project planning and risk analysis (Khurana & Rosenthal, 1998; Reid & de Brentani, 2004). With regards to these perspectives, we argue that the existing process at the subject company form the FEI as it includes the very first steps and activities for any new innovation projects. Therefore, the following literature will primarily regard the FEI.

9

Stage-Gate The proposed innovation process at the subject company shares some characteristics of a Stage-Gate process. It has individual work that lead up to decision points where decisions on the future of the project is determined. The Stage-Gate process is a widely used process to achieve more formality in a company (Kahn et al., 2006) and has been applied in many industries over the years. Formal processes are defined by Christensen & Overdorf (p. 2, 2000) as “explicitly defined and documented”, whereas informal projects are defined as “routines or ways of working that evolve over time”. The project work takes place during the different stages of the process. At each gate, so called gatekeepers are decision-makers evaluating the current status of the project and should be a cross-functional team covering competences of marketing, technical operations, sales, and finance (Cooper, 2008). Cooper’s (2008) Stage-Gate process is frequently criticised for the risk of limiting the creativity related to innovation by formalising the processes too much (Amabile, 1997; Kahn et al., 2006). The level of formality is one of the most investigated and discussed areas when it comes to FEI and no real consensus has been reached regarding which activities to formalise and when to do so (Eling & Herstatt, 2017). Loch (2000) argued that more radical NPD projects are favoured by less structured and formalised processes than incremental projects. In the practical and internal setting of a company, there is usually no clear distinction between different types of innovations. This could prove to be a challenge when deciding what type of a process should be applied for different types of innovation and the suitable level of formality. Incremental NPD projects have shown to be favoured by more formal, linear, NPD processes such as the Stage-Gate. Radical projects have shown to be more successful when supported by an iterative, non-linear process (Griffin et al., 2014). Christensen et al. (2008) argued that the traditional Stage-Gate model focuses too much on the financial aspects of a project. The Stage-Gate process is also claimed to lack clarity in how the ideation process works and is therefore suggested to be implemented after the FEI (Koen et al., 2001).

Cooper (2008) made an effort to respond to the critique he has received through the years and created an updated version of the traditional Stage-Gate process, the so-called ‘Next Generation Stage-Gate’. The purpose of the new process was to enable management of projects of different types and sizes and include new principles, such as lean and more iterative mindsets (ibid.).

Triple Phase Front End Model Khuran & Rosenthal (1998) introduced a model for describing where different activities in the front end occurs. The model is called the Triple Phase Front End Model (TPFEM) and is visualised in Figure 5. The foundation elements involve product & portfolio strategy and product development organisation. The phases are named the pre-phase zero (PP0) including opportunity identification, market and technology analysis, the phase zero (P0) including product concept and definition and lastly phase one (P1) including feasibility analysis and project planning. This model is of linear nature, much like the first versions of the Stage-Gate model and the proposed process at the subject company, meaning the activities that are included have a specified order in which they ought to occur.

10

Figure 5. The TPFEM Model (Khuran & Rosenthal, 1998).

New Concept Development Model The New Concept Development (NCD) model by Koen et al. (2001) attempts to clarify the activities related to the FEI, and to create a common language among companies, see Figure 6. The NCD provides structure to an early stage of the NPD and consists of five elements with influencing factors, such as competitors and customers, and is driven by an engine, which represents the leadership, culture and business strategy of the organisation (Koen et al., 2002). The NCD differs remarkably from the TPFEM as it allows and advocates for front end activities to occur iteratively throughout the five elements (Koen et al., 2001). It was argued that too much structure of a workflow as a process could misguide the idea owner and thereby force poor results, instead of encouraging iterations of all steps of the FEI (ibid.). The subject company’s current proposed innovation process does structure the workflow as a linear process but encourages iterations in the step ‘Strategy & Product Analysis’. Koen et al. (2001) continued to explain that some of the elements in the FEI could require support from more formal methods. Further, no conclusions on which parts of the currently proposed process at the subject company that should be formalised can be made based on the suggestions by Koen et al., (2001) as the level of understanding at this point might be limiting the possibility to explore that (ibid.).

The NCD offers a deeply theoretical understanding of the iterative nature of the FEI. It does however offer very little in terms of practical advice in terms of how to create a specialised process for the FEI. Eling & Herstatt (2017) has especially formulated that the organisation for opportunity identification and analysis are areas that has to be further researched.

11

Figure 6. The New Concept development model for the FEI (Koen et al., 2001).

FEI Deliverables Koen et al., (2001) explained that a typical outcome of the FEI is a business plan, formal project proposal or similar which is similar to the desired outcome of the entire previously proposed innovation process at the company. Much like Koen et al., (2001) presented a negative aspect of formalisation of processes, Cooper (2008) alarmed that too detailed process templates can lead to overkill deliverables where irrelevant information is provided. This could, in turn, lead to management or gate-keepers not reading all material. Cooper (2008) suggested page restrictions and field limitations to decrease the risk of unnecessary information overload. Eling & Herstatt (2017) called for further research on which tasks should be completed, which knowledge should have been created and how well developed the deliverables should be at the end of FEI. This gap in the literature implies that there are no general guidelines or best practices on the area available for the subject company to directly apply to solve their problems. Instead processes for, and management of, the FEI need to differ depending on the product, market, organisation, and context. Their findings also include that the FEI needs to be managed through applying a holistic approach that effectively links business strategy, product strategy, and product-specific decisions.

2.4 Business Modelling Frameworks Innovation has historically been tightly coupled with technological advancements. In order for a technological innovation to create value it needs to be matched with business model innovation (Teece, 2010). For any firm aiming to create value, there needs to exist an ability to create new business models (ibid.). Business modelling is a relatively young phenomena which has largely been neglected by both social- and business sciences (ibid.) up until the 1990s and still today lacks an agreed upon definition (Gordijn et al., 2005; Fielt, 2013; Da Silva & Trkman, 2014). There is a very basic definition that is generally agreed upon: “A description of how a firm does business” (Richardson, p. 136, 2008). Most definitions involve the creation and capturing of value. Fielt (2013) explained that what is meant by ‘value’ differs between those

12

attempting to define business modelling and that this is the main issue regarding its ambiguity. Osterwalder & Pigneur (p. 14, 2010) defined business modelling as “describing the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value”. Further, Chesbrough (2006) explained that a business model performs two important functions: value creation and value capture. Similarly, in a study of literature reviews on business model definitions Fielt (p. 96, 2013) proposed the definition of a business model as “the value logic of an organization in terms of how it creates and captures customer value and can be concisely represented by an interrelated set of elements that address the customer, value proposition, organizational architecture and economics dimensions”. The definition of ‘value’ depends on who uses the word and changes dependent on the situation. It is further explained that most authors that attempts to define business modelling refers to ‘value’ as ‘customer value’, but that it mainly has its theoretical foundation in the field of strategic management where capturing value is based on a firm's positioning, transaction costs, and a resource-based view (RBV) (Fielt, 2013).

Fielt (2013) explained that business modelling can be used for many different purposes due to the differences in definitions on value and business modelling. It has been described as a superior way of analysing a company’s business in comparison to both the position theory in Porter’s (1979) framework of five forces and Wernerfeldt’s (1984) RBV of the firm (McGrath, 2010). DaSilva & Trkman (2014) argued that the RBV cannot explain business modelling fully as resources themselves do not deliver any value to customers, but that a unique combination of resources can together create value. They defined the core of the business model as “a combination of resources which through transactions generate value for the company and its customers” (p. 382, 2014). The multi-purpose of business modelling can be another reason as to the ambiguity in the definitions on business modelling, as it has been used for a wide range of applications where technology have had a varying importance, where the business objectives have been profit or non-profit or for developing start-ups or mapping established businesses (Fielt, 2013). DaSilva & Trkman (2014) were critical to the inflation in the use of the terminology business modelling and argued that it has become a buzzword that is widely used without a foundation in theory. This further strengthens the notion of the issue being that there is a lack of a clear and common definition of business modelling. Business modelling frameworks have been used to clarify a current business model of a company, to illustrate financial incentives for a new project or to describe a whole new business plan (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). It has been argued that specific business modelling frameworks can be used with the purpose of summarising a business plan as those are usually too extensive and less communicative (ibid.). The application of business modelling frameworks appears to be one possible practical approach to some of the activities explained in the NCD framework (McGrath, 2010; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Maurya, 2012). Techniques for practicing and enabling innovation as a process and to enable the emergence of innovation as a result are not as widely discussed as the theoretical aspects of the FEI (Eling & Herstatt, 2017). The techniques which are suggested as related to the FEI process are mainly techniques for customer research and involvement of customers, idea management techniques, process methods or techniques for executing parts of the FEI process. We argue that the major theoretical concept that includes practical activities and elements of the FEI can be found in existing business modelling frameworks, and thus relating them to the early stages of innovation. Existing theory on business modelling frameworks needs to be examined to discover whether any one of them can be directly applied to the domain of the FEI, in which we aim to provide guidance for the subject company. We argue that there are some frameworks on business modelling that are more aimed towards the activities related to the FEI and therefore could have a contribution to the results.

13

Discovery-Driven Approach McGrath & MacMillan (1995; 2000) suggested a discovery-driven approach to business modelling and creating a competitive advantage to ensure that the firm’s competitive advantage and profitability is sustainable. This approach emphasises as much learning as possible with as little resources as possible by articulation and testing of assumptions. The approach starts with an idea that a decision maker believes represents opportunity. That belief must then be validated in order to convince others that the result will be worth the efforts. The steps of the discovery-driven approach are formulated as questions that should be answered, starting with “What would make a particular strategic move worthwhile?” (p. 258, 2010). After doing so, the requirements for creating a reverse income statement should be articulated. Next, the question “How much revenue would be required to throw off enough profit to make and initiative worthwhile?” (p. 258, 2010) should be answered. The market potential should then be evaluated and key metrics that describes the potential success of the business model should be articulated, together with the most critical assumptions.

The Business Model Framework Richardson (2008) summarised the concept of business modelling in his own framework. His study of the components of business modelling resulted in a framework that is centred around the concept of value. He explained that there are three major components to business modelling in general, namely ‘the value proposition’, ‘the value creation and delivery system’ and ‘value capture’, each with their subcomponents, see Figure 7.

Figure 7. The Business Model Framework (Richardson, 2008).

14

Business Model Canvas Along the same approach to business modelling as McGrath (2010), Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010) created a Business Model Canvas (BMC) which formulated the components of a business model. It is the most well-known and widely used framework for business modelling (Fielt, 2013). It visualises many of the important aspects of business modelling that McGrath (2010) explained. The canvas is divided into nine building blocks, each with questions to be answered, see Figure 8, and is based upon earlier work by one of the authors (Osterwalder, 2004). Its primary function is to serve as a common language to describe, visualise, evaluate and change business models (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

Looking at business modelling through the lens of Khuran & Rosenthal’s (1997) TPFEM, it is apparent that the BMC can have a practical use during all stages of the TPFEM and covers the related activities opportunity identification, market and technology analysis, product concept, feasibility analysis etc. Further, the BMC allows for a more iterative approach to front-end activities than the TPFEM explained, resembling the more recent model of the two representations of the FEI explained by Koen et al. (2001). The BMC has been criticised for being more suitable for improving core innovations for the existing business and less for developing transformational innovations (Maurya, 2012).

Figure 8. BMC by Alexander Osterwalder & Yves Pigneur (2010).

Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010) did not propose a clear order of how to fill in the blocks or a step-by-step approach to using their business model canvas, but instead identifies typical origins of innovation drivers. They name these ‘Epicentres’ and are divided into resource-, offer-, customer-, and finance-driven innovations and originates from either the problem, value proposition, customer segment, or the financial part of the canvas. It is also highlighted that the innovation could be of multiple-epicentres character, originating from several parts of the canvas.

Another approach to the order in which business modelling should be done is that it is dependent on the firm’s innovation strategy. Yannou et al. (2015) explained that Boston Consulting Group identified that there are three types of innovation strategies: The ‘Technology Driver’, the ‘Need Seeker’ and the ‘Market Reader’. The ‘Technology Driver’-firm’s strategy should have the approach of being resource led, meaning that one should start from identifying which are the

15

firm’s key resources and partners, or offer led, meaning that the company’s value proposition should guide the approach. The ‘Need Seeker’-firm’s innovation strategy should have a customer insight led approach to business modelling, meaning that the value proposition, revenue model, customer relations and channels should be derived from the needs and characteristics of the specific customer segment. Lastly, the ‘Market Reader’ should have either a finance led approach to business modelling, meaning deriving the customers and value proposition from established revenue streams and costs structures, or a multiple-centred led start, meaning creating a value proposition from key partners and resources and a customer segmentation and finding a suitable cost structure and revenue model.

Lean Startup & Lean BMC Inspired by Blank’s customer development practices for start-ups that he developed for teaching, and on Toyota’s lean manufacturing (Ward et al., 1995; Morgan & Liker, 2006), Ries (2011) introduced the Lean Startup approach to business modelling which aims to reduce waste in the new business development process and includes the concepts ‘failing fast’ and ‘continuous learning’, which aligns well with the discovery-driven approach. The method builds upon three key principles: (1) Hypotheses should be sketched and identified in a BMC instead of wasting time on building elaborate business plans that will fail anyways; (2) develop your customer by getting out of the building, and (3) agile development through an iterative build-measure-learn principle. The approach is advocated to be successful in all types of industries, no matter the size of the company. Further, it is closely related to dealing with risk and reducing uncertainty (Loch et al., 2008).

The similarities between transformational products and services, and start-ups lie in the type of context they are created in, which is extreme uncertainty (Ries, 2011). Maurya (2012) presented a different version of the BMC by Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010), which is argued to be more suited for the Lean Startup, called the Lean BMC, see Figure 9.

Figure 9. Lean BMC and the order of filling out the blocks of it (Maurya, 2012).

Maurya (2012) advocated for a specific order in which the blocks of the canvas should be given focus respectively, see Figure 9 above. The reasoning behind is that all start-ups should use the lean principles which recommend customer centric business development (Ries, 2011).

16

The Lean BMC is thus argued to be suitable for both start-ups and established companies looking to reinvent their business models. Even though it is argued by both Maurya (2012) and Ries (2011) that the Lean BMC can be used by established companies, their books do not provide guidance to a large extent in terms of development of new business plans within established firms. The essentials of both approaches are still of value to this thesis and to the subject company but requires adjustment to suit the company needs.

FEI Canvas Koen (2017) presented a canvas that was specifically developed for the FEI with the purpose of acting as a brainstorming tool for new projects, see Appendix A. The FEI Canvas was developed to take consideration to all critical components of a large organisation. A division is made between the blocks with regards to what part of the environment it aims to describe, the external- or internal environment. This is something that is characterising of good business model design (Teece, 2010). The internal aspects of the FEI Canvas include the building blocks ‘Key Resources’ and ‘Key Processes’ (‘Key Activities’ in the BMC) from Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010), while the external aspects of it has similarities to the Lean BMC. Further, an aspect of risk and assumptions is added in order to emphasise which parts of the business model are the most crucial and least validated. The addition of risks and assumptions is what makes this canvas unique with regards to its predecessors. This could be an indication of the importance of highlighting including those building blocks in a business modelling framework for the FEI.

Value Proposition Canvas Osterwalder et al. (2014) presented an additional canvas, called the ‘Value Proposition Canvas’ (VPC), in order to describe the customer segment and value proposition in a more structured and detailed way, see Figure 10. It focuses on the jobs, pains, and gains for the customer and how these can be done, relieved, and created. The purpose of the two maps is to fit the value proposition to the customer segment, and when the customers feel excitement for the proposed value, the fit is successful. If there are different customer segments for the same project, one VPC should be created for each customer segment (Osterwalder et al., 2014). The same approach should be applied when several stakeholders are involved, both internal and external, which is a typical situation in a B2B company (ibid.). The VPC was originally developed as a complement to the BMC.

Figure 10. The VPC, connecting the customer segment and value proposition (Osterwalder et al., 2014).

17

Triple Layer Business Model Canvas For organisations to work consequently with sustainability and to take value other than economic perspectives in consideration in their business model, Joyce et al. (2016) have created an extended version of the BMC called the Triple Layer Business Model Canvas (TLBMC), see Figure 11. Their version adds an environmental canvas to the business model which highlights a lifecycle perspective and a social canvas which takes stakeholders’ perspectives in consideration. The tool creates an opportunity for an organisation to both work with vertical coherence, which regards the coherence between the three layers, and horizontal coherence, which regards the coherence of each individual canvas (ibid.). Even though the TLBMC is ideally applied on whole organisations, it can favourably be applied in individual projects as well. This puts the idea owner is a situation where social and environmental aspects are naturally considered in early phases of a project.

Figure 11. The economic-, environmental- and social canvas of the Triple Layer Business Model Canvas (Joyce et al., 2016).

2.5 Concluding Remarks We recognise that there are several knowledge gaps within the FEI literature, many already identified by Eling & Herstatt (2017). If one does not view business modelling as an important practical part of new project development and fail to connect literature on the FEI to business modelling, there are few practical techniques suggested for the activities included in the FEI. Therefore, the subject company cannot derive a complete process from strictly peer-reviewed articles that provides guidance throughout the ‘Formulating’-phase of the POC-process. Because, as mentioned, there is no one-solution-fits-all, a tailored solution to the problem facing the company is required, which is supported by Fielt (2013) who explained that tailoring (or specifying) the elements of a business model can make it more suitable for a specific purpose such as making it more suitable for innovation. There is a plethora of techniques on business analysis frameworks to find on the internet. These are mostly derived from practitioners such as consultancy firms (McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group etc.) and membership institutions (International Institute of Business Analysis, Project Management Institute etc.).

18

Generally, there are few empirical studies that have been performed on which techniques, elements and building blocks that should be included in a business model framework to yield different innovation results (Fielt, 2013).

19

3 METHOD This chapter presents the chosen research methodology for developing the result. It explains what sources of inspirations contributed to the chosen methodology, how the problem was defined, how the scientific literature that is related to the problem was chosen, how the interviews were conducted and how the framework was synthesised. Lastly, it explains the way the framework was developed to guide the less experienced idea owners.

3.1 Action Research In 1946, Kurt Lewin pioneered an approach to research, known today as ‘Action Research’ (AR), or in his own words “a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action and research leading to social action” (p. 45, 1946). Lewin’s explanation to the process of AR, which is named the ‘Lewinian Spiral’, is “a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action” (Susman & Evered, p. 587, 1978). In their assessment of the scientific merits of action research, Susman & Evered (1978) argued that positivist research versus action research is like prediction versus making things happen, and that “[AR] constitutes a kind of science with a different epistemology that produces a different kind of knowledge, a knowledge which is contingent on the particular situation, and which develops the capacity of members of the organization to solve their own problems”(p. 601, 1978). A more widely accepted definition of AR is the one by Rapoport (p. 499, 1970) who explained that AR “aims to contribute both to the practical concerns of people in an immediate problematic situation and to the goals of social science by joint collaboration with a mutually acceptable ethical framework”.

The purpose was to tailor a solution to the explained problem through collaboration with the subject company. Therefore, AR served as a source of inspiration to increase the applicability of the result. The result was developed and is presented in two parts: (1) through semi-structured qualitative interviews and (2) development of a tailored framework including a deeper analysis of the building blocks that are related to the frameworks on business modelling presented in the frame-of-reference.

3.2 Problem Definition Most of the interaction with the company was done through a company representative. This connection was the foundation for opportunity identification and describing the company’s problem. The research required to solve the identified problem was performed through qualitative interviews and literature research. Initially, the representative at the company introduced the issue through discussions with one of the researchers who had been employed under the forms of an internship. The problem was refined through discussions between both researchers and the company representatives during early 2019.

3.3 Frame-of-Reference A study of previous research was performed within the domain of the problem at hand. The study was performed through a computer-based literature search and through a study of physical books and e-books related to the topic. Greenhalg & Peacock’s (2005) findings show that the

20

greatest yields when performing literature reviews come from finding articles that are referenced from references, known as ‘Snowballing’. This approach to finding literature has been the primary method for finding related articles to those with significant findings to the topic. Literature research was done related to the problem domain to initiate a snowball-effect. The keywords, categories and domains ‘Innovation’, ‘NPD’, ‘Front End of Innovation’, ‘Uncertainty’ and ‘Business Modelling’ were identified and used in Google Scholar and at KTH Library’s website.

3.4 Interviews Communication with top management in the subject company was required to fully understand the problem, to articulate the requirements from the company, and to ensure that management supported the developed framework. The importance of top management support for product success has been demonstrated (Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1987; Koen et al., 2001). Cooper (2008) explained that the greatest change in behaviour at an organisation takes place at the top and that a lack of knowledge regarding what information is necessary for a project could result in too much bureaucracy by demanding too much information from the project leader. This is further, emphasised by Koen et al. (2002) who explained that one of the most effective means for success in the FEI is setting criteria that describe what an attractive project looks like for the evaluation of new ideas. Clear deliverables were defined to decrease the risk of creating a tedious and bureaucratic material related to the framework. Because of this, the top management team consisting of four members were subject to the interviews. As multiple interviewees reduces the risk of a biased perspective (O’Connor & Rice, 2013), three members of the management team, the CEO excluded, were interviewed separately with the split purpose of establishing and verifying their individual commitment to establishing a process for innovation, as well as examining what criteria they evaluate new ideas on. Each member of the management team is responsible for the individuals within a certain function, such as sales and marketing. The interviews were qualitative and followed a semi-structure approach. Important to think about when performing semi-structured interviews is to have the topic on which the discussion should regard clearly defined (Edwards & Holland, 2013). Prior to the meeting, the interviewees had been asked to prepare measurements that they evaluate new projects upon with regards to their functional responsibilities as well to the responsibilities of being part of the management team. They were asked to describe their evaluation measurements and to identify what their respective team generally finds important when being introduced to a new project entering the innovation process. To clarify the topic of discussion, the following open-ended questions were posed to the interviewees to spark a discussion:

• What are the critical areas that generally have to be investigated from a top management perspective early on in a project?

• What are the critical areas that generally have to be investigated from a [department] perspective early on in a project?

• What information does [department] generally need to create material for a new release/ product add on or similar?

• How would [department] like to receive this information?

21

3.5 Developing a Business Modelling Framework The results of the studies of the problem domain were an identification of a gap between theoretical conclusions and practical application. Literature could not provide a definitive solution to the problem of the subject company. Therefore, a new business modelling framework had to be developed to solve the problem at hand, one that considered the wishes and requirements of the top management team at the company. The frame-of-reference and the interviews laid the foundation for a deeper analysis of theory related to business modelling that is presented in the result. This theory was essential to the development of the framework. Previous research on business modelling frameworks has evolved from requirement specifications on components of the business model to become building blocks and frameworks (Gordijn et al., 2005). We chose to adopt a methodology that others previously have used to develop frameworks on business modelling (ibid.). It involves formulating a requirement specification on components to the business model. The choice of building blocks to the framework was subject to inspiration from existing frameworks on business modelling and the interview results. The framework is thus supported by both literature and management requirements on the content of the building blocks. The results from the management interviews were distilled into questions that would guide the progress towards the next presentation for evaluation by the management team. The contents of the building blocks will be referred to as ‘the questions’. The go-to source for this information was believed to be literature on the FEI, but the peer-reviewed body of literature on the FEI provides few suggestions on how to build an early business case to be subject to evaluation in the FEI. Further, the body of literature that discusses the importance of idea evaluation (Khuran & Rosenthal’s, 1997; Koen et al. 2001) proved to give little suggestions on practical questions to ask and answer to evaluate idea feasibility. Best practices in this area are more commonly discussed at a later stage of the innovation process, the NPD process, such as Kahn et al., (2006) and Barczak & Kahn (2012). Guidance on the topic from peer-reviewed literature included the four categories of uncertainty (Resources, Organisational, Market and Technical) (O’Connor & Rice, 2013) and from discovery-driven planning (McGrath, 2010). In addition to those questions, practitioners’ approach (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010; Maurya, 2012) provided multiple questions from both the BMC and the Lean BMC where questions were related to each block of the respective canvas. Lastly, Venture Cup (2017), a Swedish organisation for inspiration, guidance and education of new business ventures, provided useful questions for assessing feasibility. The compiled questions from both the scientific literature and the management team were reviewed whereas there were some duplicates in terms of purpose. The questions that were most relevant were chosen for the building blocks of the business modelling framework.

3.6 Supporting Techniques As the goal of the framework is to be used by anyone within the organisation, techniques for answering the questions would aid the user with less experience in business modelling. This was not an area in which peer-reviewed literature provided much guidance. In some cases, the questions were self-explanatory. In other cases, techniques with a more practical application were drawn from literature related to business modelling, based on the findings from Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010), McGrath (2010), Ries (2011), Maurya (2012) and Osterwalder et al., (2014) amongst other. The findings were then categorised with regards to the structure of the framework in which the findings could aid the idea owner in answering the questions. Other practical methods with the purpose of answering the questions were derived from experienced

22

practitioners within the field of business modelling such as Blank (2017). The scientifically reviewed literature on the topic business modelling provided guidelines and suggestions on what to achieve rather than how to achieve it. When an interesting technique was found, further research was performed on the specific area to fully understand the potential fit to the framework. Other sources for inspiration on techniques included, but were not limited to, ‘Project Portfolio Management’ (PPM) and ‘Risk Diagnosis Methodology’ (RDM). PPM was explored as it was argued by Killen et al. (2008) to be a successful way for management to improve the innovation outcome of the company but proved to relate to later stages of NPD. RDM was explored as it in a case study by Keizera et al. (2002) had proven to reduce both time-to-market and overall project cost but was ultimately neglected as the framework is extensive and requires a lot of resources to perform in practice. Looking at what the company expected as deliverables from the current phase, both approaches were neglected.

23

4 INTERVIEW RESULTS The results from the interviews mainly considered the importance of aligning new projects with business strategy and the impact of new projects, both internally and externally. Each interview result is presented in a table with three levels of information. All the interview results were considered in the development of the business modelling framework.

4.1 Head of Sales The main contributions to the idea evaluation criteria from the Head of Sales regarded financial estimations. The main takeaways from the interview are presented in Table 1. Counting from the left, the first column includes the what the requirements on the material for the ‘Formulating’-phase should include. The second column describes the information that the specific department that the interviewee manages wishes to have from the material. Lastly, the third column contains extracted information that could be valuable for the idea developer.

Table 1. Results from interview with the Head of Sales.

Business model requirements from a management perspective:

Information that the Sales team wishes to have:

Other valuable information for the idea developer:

• A hypothesis of costs related to the initiative.

• An estimation of the time until a break-even point is reached.

• An estimation of how much revenue will be generated by this initiative in 12 months.

• An estimation of the Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) generated through the initiative and when this will be achieved.

• A level of certainty to the financial calculations.

• An estimation of the resources that are required to reach a set level of certainty in financial projections.

• Minimum requirements for the sales team to make the initiative a success.

• Required time commitment (time to learn the new product and selling it).

• A Lean BMC for an overview of the initiative.

• The approximate cost of one hour of work from one of the sales team.

• One way of presenting the financial estimations could be through scenario-based cases where 3 different scenarios are presented: One best case scenario, one realistic scenario and one worst-case scenario.

• Important question: How will the initiative be managed internally if approved?

4.2 Chief Technology Officer (CTO) The most important aspects of any new project to the CTO are to show the reasoning behind estimations and to always make decisions with regards to the most important metric according to overarching company strategy. Currently, the focus for the organisation is on the ‘Monthly Recurring Revenue’ (MRR). The relevant takeaways are presented in Table 2.

24

Table 2. Results from interview with the CTO.

Business model requirements from a management perspective:

Information that the IT & Data team wishes to have:

Other valuable information for the idea developer:

• A hypothesis of costs related to the initiative already at first presentation.

• An estimation of the time until a break-even point is reached.

• An estimation of the Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) generated through the initiative and when this will be achieved.

• A level of certainty to the financial calculations.

• An estimation of the resources that are required to reach a set level of certainty in financial projections.

• An estimation of activities, resources and responsibilities after the POC.

• An estimation of the time for development.

• Background information and purpose of the project to encourage creativity in problem solving.

• Functionality flow charts, both for the new product and an overview.

• The approximate cost of one hour of work from one of the data team members.

• Important to have MRR in consideration for every decision along the project.

• The idea suggestion threshold needs to be low in order to increase the number of ideas that are presented to the management team.

• How and what should be documented from the decision gates?

• A strategic value could be as important as monetary and financially successful projects.

4.3 Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) The CMO articulated a focus on practical aspects of new ideas with regards to marketing, such as how to go about communicating the essence of a new project to marketing staff, and the importance of involving the marketing function early on in a new project. The compiled result from the interview with the CMO is presented in Table 3. Much like the previous interviews, it was articulated that it is important to approximate the time that is required from the functional team to perform the specified activities.

25

Table 3. Results from interview with the CMO.

Business model requirements from a management perspective:

Information that the Marketing team wishes to have:

Other valuable information for the idea developer:

• Demonstration of a clear business alignment, as time and MRR is not always the best measures for a project.

• An assessment of the impact on the organisation and involved departments.

• A calculation of Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) using only external costs.

• Payback time calculations.

• In cases where efforts are required from the marketing team: A filled in ‘Briefing Document’, which is developed by marketing to communicate the essence of the project.

• The briefing document should also be used to estimate the time required for marketing material related to the project.

• Unique Selling Points (USPs).

• Answers to Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) by customers.

• Involvement of the marketing function earlier in the process as they hold data regarding competitors, research, perspective, personas etc.

• Previously, a scale of ‘small’, ‘medium’, ‘large’ has been used to evaluate the trust in, or potential of different aspects of a project.

• In cases where insight in competitors is needed, one can contact the marketing team.

• The ability to give feedback on specific aspects of a new project even though it passes a decision point.

• The approximate cost of hiring a consultant when calculating costs for marketing work.

• Important to have a get-to-the- point-attitude when presenting, use straight communication.

27

5 THE FRAMEWORK This chapter explains the engineered results from the development of the framework. It includes a deeper analysis of the different business modelling frameworks presented in the frame-of-reference which contributed to the resulting framework. Chosen techniques for answering the questions of each block are presented in their related building block.