60th Anniversary of the DNA Secondary Structure Discovery

Transcript of 60th Anniversary of the DNA Secondary Structure Discovery

YU ISSN 0042-8450

VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED^asopis lekara i farmaceuta Vojske Srbije

Military Medical and Pharmaceutical Journal of Serbia

Vojnosanitetski pregledVojnosanit Pregl 2013; December Vol. 70 (No. 12): p. 1075-1180.

YU ISSN 0042-8450 vol. 70, br. 12, 2013.

Štampa Vojna štamparija, Beograd, Resavska 40 b.

VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLEDPrvi broj Vojnosanitetskog pregleda izašao je septembra meseca 1944. godine

asopis nastavlja tradiciju Vojno-sanitetskog glasnika, koji je izlazio od 1930. do 1941. godine

IZDAVAUprava za vojno zdravstvo MO Srbije

IZDAVA KI SAVET

prof. dr sc. med. Boris Ajdinoviprof. dr sc. pharm. Mirjana Antunovi

prof. dr sc. med. Dragan Din i , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Zoran Hajdukovi , puk.

prof. dr sc. med. Nebojša Jovi , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Marijan Novakovi , brigadni general

prof. dr sc. med. Zoran Popovi , brigadni general (predsednik)prof. dr Sonja Radakovi

prof. dr sc. med. Predrag Romi , puk.prim. dr Stevan Sikimi , puk.

ME UNARODNI URE IVA KI ODBOR

Prof. Andrej Aleksandrov (Russia)Assoc. Prof. Kiyoshi Ameno (Japan)

Prof. Rocco Bellantone (Italy)Prof. Hanoch Hod (Israel)

Prof. Abu-Elmagd Kareem (USA)Prof. Hiroshi Kinoshita (Japan)

Prof. Celestino Pio Lombardi (Italy)Prof. Philippe Morel (Switzerland)

Prof. Kiyotaka Okuno (Japan)Prof. Stane Repše (Slovenia)

Prof. Mitchell B. Sheinkop (USA)Prof. Hitoshi Shiozaki (Japan)

Prof. H. Ralph Schumacher (USA)Prof. Miodrag Stojkovi (UK)

Assist. Prof. Tibor Tot (Sweden)

URE IVA KI ODBOR

Glavni i odgovorni urednikprof. dr sc. pharm. Silva Dobri

Urednici:

prof. dr sc. med. Bela Balintprof. dr sc. stom. Zlata Brkiprof. dr sc. med. Snežana Ceroviakademik Miodrag oli , brigadni generalakademik Radoje oloviprof. dr sc. med. Aleksandar urovi , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Branka uroviprof. dr sc. med. Borisav Jankoviprof. dr sc. med. Lidija Kandolf-Sekuloviakademik Vladimir Kanjuhakademik Vladimir Kostiprof. dr sc. med. Zvonko Magiprof. dr sc. med. oko Maksi , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Gordana Mandi -Gajiprof. dr sc. med. Dragan Miki , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Darko Mirkoviprof. dr sc. med. Slobodan Obradovi , potpukovnikakademik Miodrag Ostojiakademik Predrag Peško, FACSakademik or e Radakprof. dr sc. med. Ranko Rai evi , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Predrag Romi , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Vojkan Stani , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Dara Stefanoviprof. dr sc. med. Dušan Stefanovi , puk.prof. dr sc. med. Vesna Šuljagiprof. dr sc. stom. Ljubomir Todoroviprof. dr sc. med. Milan Višnjiprof. dr sc. med. Slavica Vu ini

Tehni ki sekretari ure iva kog odbora:dr sc. Aleksandra Gogi , dr Snežana JankoviREDAKCIJAGlavni menadžer asopisa:dr sc. Aleksandra Gogi

Stru ni redaktori:mr sc. med. dr Sonja Andri -Krivoku a, dr Maja Markovi ,dr Snežana Jankovi

Tehni ki urednik: Milan PerovanoviRedaktor za srpski i engleski jezik:Dragana Mu ibabi , prof.Korektori: Ljiljana Milenovi , Brana SaviKompjutersko-grafi ka obrada:Vesna Toti , Jelena Vasilj, Snežana uji

Adresa redakcije: Vojnomedicinska akademija, Institut za nau ne informacije, Crnotravska 17, poštanski fah 33–55, 11040 Beograd, Srbija. Telefoni:glavni i odgovorni urednik 3609 311, glavni menadžer asopisa 3609 479, pretplata 3608 997. Faks 2669 689. E-mail (redakcija): [email protected] objavljene u „Vojnosanitetskom pregledu“ indeksiraju: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Journal CitationReports/Science Edition, Index Medicus (Medline), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), EBSCO, Biomedicina Serbica. Sadržajeobjavljuju Giornale di Medicine Militare i Revista de Medicina Militara. Prikaze originalnih radova i izvoda iz sadržajaobjavljuje International Review of the Armed Forces Medical Services.

asopis izlazi dvanaest puta godišnje. Pretplate: Žiro ra un br. 840-314849-70 MO – Sredstva objedinjene naplate – VMA (za Vojnosanitetskipregled), poziv na broj 12274231295521415. Za pretplatu iz inostranstva obratiti se službi pretplate na tel. 3608 997. Godišnja pretplata: 5 000dinara za gra ane Srbije, 10 000 dinara za ustanove iz Srbije i 150 € (u dinarskoj protivvrednosti na dan uplate) za pretplatnike iz inostranstva.Kopiju uplatnice dostaviti na gornju adresu.

YU ISSN 0042-8450 vol. 70 No. 12, 2013

Printed by: Vojna štamparija, Beograd, Resavska 40 b.

VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLEDThe first issue of Vojnosanitetski pregled was published in September 1944

The Journal continues the tradition of Vojno-sanitetski glasnik which was published between 1930 and 1941

PUBLISHERMilitary Health Department, Ministry of Defence, Serbia

PUBLISHER’S ADVISORY BOARD

Prof. Boris Ajdinovi , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Mirjana Antunovi , BPharm, PhD

Col. Assoc. Prof. Dragan Din i , MD, PhDCol. Assoc. Prof. Zoran Hajdukovi , MD, PhD

Col. Prof. Nebojša Jovi , MD, PhDBrigadier General Prof. Marijan Novakovi , MD, PhD

Brigadier General Prof. Zoran Popovi , MD, PhD (Chairman)Prof. Sonja Radakovi , MD, PhD

Col. Prof. Predrag Romi , MD, PhDCol. Stevan Sikimi , MD

INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD

Prof. Andrej Aleksandrov (Russia)Assoc. Prof. Kiyoshi Ameno (Japan)

Prof. Rocco Bellantone (Italy)Prof. Hanoch Hod (Israel)

Prof. Abu-Elmagd Kareem (USA)Prof. Hiroshi Kinoshita (Japan)

Prof. Celestino Pio Lombardi (Italy)Prof. Philippe Morel (Switzerland)

Prof. Kiyotaka Okuno (Japan)Prof. Stane Repše (Slovenia)

Prof. Mitchell B. Sheinkop (USA)Prof. Hitoshi Shiozaki (Japan)

Prof. H. Ralph Schumacher (USA)Prof. Miodrag Stojkovi (UK)

Assist. Prof. Tibor Tot (Sweden)

EDITORIAL BOARDEditor-in-chiefProf. Silva Dobri , BPharm, PhD

Co-editors:Prof. Bela Balint, MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Zlata Brki , DDM, PhDAssoc. Prof. Snežana Cerovi , MD, PhDBrigadier General Prof. Miodrag oli , MD, PhD, MSAASProf. Radoje olovi , MD, PhD, MSAASCol. Assoc. Prof. Aleksandar urovi , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Branka urovi , MD, PhDProf. Borisav Jankovi , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Lidija Kandolf-Sekulovi , MD, PhDProf. Vladimir Kanjuh, MD, PhD, MSAASProf. Vladimir Kosti , MD, PhD, MSAASProf. Zvonko Magi , MD, PhDCol. Prof. oko Maksi , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Gordana Mandi -Gaji , MD, PhDCol. Assoc. Prof. Dragan Miki , MD, PhDProf. Darko Mirkovi , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Slobodan Obradovi , MD, PhDProf. Miodrag Ostoji , MD, PhD, MSAASProf. Predrag Peško, MD, PhD, MSAAS, FACSProf. or e Radak, MD, PhD, MSAASCol. Prof. Ranko Rai evi , MD, PhDCol. Prof. Predrag Romi , MD, PhDCol. Prof. Vojkan Stani , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Dara Stefanovi , MD, PhDCol. Prof. Dušan Stefanovi , MD, PhDProf. Milan Višnji , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Slavica Vu ini , MD, PhDAssoc. Prof. Vesna Šuljagi , MD, PhD.Prof. Ljubomir Todorovi , DDM, PhD

Technical secretaryAleksandra Gogi , PhD, Snežana Jankovi , MD

EDITORIAL OFFICEMain Journal ManagerAleksandra Gogi , PhDEditorial staffSonja Andri -Krivoku a, MD, MSc; Snežana Jankovi , MD;Maja Markovi , MD; Dragana Mu ibabi , BATechnical editorMilan PerovanoviProofreadingLjiljana Milenovi , Brana SaviTechnical editingVesna Toti , Jelena Vasilj, Snežana uji

Editorial Office: Military Medical Academy, INI; Crnotravska 17, PO Box 33–55, 11040 Belgrade, Serbia. Phone:Editor-in-chief +381 11 3609 311; Main Journal Manager +381 11 3609 479; Fax: +381 11 2669 689; E-mail: [email protected] published in the Vojnosanitetski pregled are indexed in: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Journal CitationReports/Science Edition, Index Medicus (Medline), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), EBSCO, Biomedicina Serbica. Contents arepublished in Giornale di Medicine Militare and Revista de Medicina Militara. Reviews of original papers and abstracts ofcontents are published in International Review of the Armed Forces Medical Services.The Journal is published monthly. Subscription: Giro Account No. 840-314849-70 Ministry of Defence – Total means ofpayment – VMA (for the Vojnosanitetski pregled), refer to number 12274231295521415. To subscribe from abroad phone to+381 11 3608 997. Subscription prices per year: individuals 5,000.00 RSD, institutions 10,000.00 RSD, and foreign subscribers150 €.

Poštovani autori, urednici, recenzenti i saradnici Vojnosanitetskog pregleda,

Opraštaju i se od stare godine, zahvaljujem vam na izuzetnoj saradnji i podršci uz želje danam nastupaju a 2014. godina donese još više uspeha i radosti!

SRE NA NOVA GODINA I BOŽI NI PRAZNICI!Srda no,prof. dr Silva Dobri ,glavni i odgovorni urednik

Dear Authors, Editors, Reviewers, and Collaborators of the Vojnosanitetski Pregled,

Saying farewell to 2013, I express my deep gratitute to your extraordinary cooperationand support along with my best whishes that the coming New Year 2014 bring us moresuccess and happiness!

MARRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR!

Cordially,Prof. Dr. Silva Dobri

Editor-in-Chief

VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED

VOJNOMEDICINSKA AKADEMIJA

Crnotravska 17, 11040 Beograd, SrbijaTel/faks: +381 11 [email protected]@hotmail.com

Poziv za reklamiranje u 2014. godini

U prilici smo da vam ponudimo mogu nost oglašavanja i reklamiranja proizvoda i usluga u asopisu

„Vojnosanitetski pregled“ (VSP). To je sigurno najbolji vid i najzastupljeniji na in upoznavanja

eventualnih korisnika sa vašim uslugama i proizvodima.

asopis „Vojnosanitetski pregled“, zvani ni organ lekara i farmaceuta Vojske Srbije, nau no-

stru nog je karaktera i objavljuje radove iz svih oblasti medicine, stomatologije i farmacije. Radove

ravnopravno objavljuju stru njaci iz vojnih i civilnih ustanova i iz inostranstva. Štampa se na srpskom i

engleskom jeziku. asopis izlazi neprekidno od 1944. godine do sada. Jedini je asopis u zemlji koji izlazi

mese no (12 brojeva), na oko 100 strana A4 formata, a povremeno se objavljuju i tematski dodaci

(suplementi). Putem razmene ili pretplate VSP se šalje u 23 zemlje sveta. Radove objavljene u VSP-u

indeksiraju: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Journal Citation Reports/Science Edition, Index Medicus

(Medline), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), EBSCO (preko ove baze VSP je dostupan on line od 2002. godine u

pdf formatu) i Biomedicina Serbica.

Cene reklama i oglasa u asopisu „Vojnosanitetski pregled“ u 2014. godini su:

1. Oglas u crno-beloj tehnici A4 formata za jedan broj 20 000,00 dinara2. Oglas u c/b tehnici A4 formata za celu godinu (11-12 brojeva) 200 000,00 dinara3. Oglas u boji A4 formata za jedan broj 35 000,00 dinara4. Oglas u boji A4 formata za celu godinu (11-12 brojeva) 330 000,00 dinara5. Oglas u boji na koricama K3 za jedan broj 50 000,00 dinara6. Oglas u boji na koricama K3 za celu godinu (11-12 brojeva) 455 000,00 dinara7. Oglas u boji na koricama K2 i K4 za jedan broj 55 000,00 dinara8. Oglas u boji na koricama K2 i K4 za celu godinu (11-12 brojeva) 530 000,00 dinara

Za sva obaveštenja, uputstva i ponude obratiti se redakciji asopisa „Vojnosanitetski pregled“.

Sredstva se upla uju na žiro ra un kod Uprave javnih pla anja u Beogradu broj: 840-941621-02 VMA (za

Vojnosanitetski pregled ili za VSP), PIB 102116082. Uplatnicu (dokaz o uplati) dostaviti li no ili poštom

(pismom, faksom, e-mail-om) na adresu: Vojnosanitetski pregled, Crnotravska 17, 11000 Beograd; tel/faks:

011 2669 689, e-mail: [email protected] ili [email protected]

Volumen 70, Broj 12 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana MLXXIX

CONTENTS / SADRŽAJ

ORIGINAL ARTICLES / ORIGINALNI LANCI

Sonja Pr i , Zorica Gajinov, Bogdan Zrni , Anica Radulovi , Milan Mati , Verica DjuranEpidemiological and clinical features of erythema infectiosum in children in Novi Sad from 2000to 2009Epidemiološke i klini ke karakteristike infektivnog eritema kod dece u Novom Saduu periodu 2000–2009................................................................................................................................... 1081Nikola Stankovi , Predrag Vlahovi , Vojin SaviHistomorphological and clinical study of primary and secondary glomerulopathies in SoutheastSerbia (20-year period of analysis)Histomorfološko i klini ko ispitivanje primarnih i sekundarnih glomerulopatija u jugoisto noj Srbiji(analiza u periodu od 20 godina) ................................................................................................................. 1085Aleksandar Argirovi , Djordje ArgiroviDoes the addition of Serenoa repens to tamsulosin improve its therapeutical efficacy in benignprostatic hyperplasia?Da li dodavanje Serenoa repens tamsulosinu poboljšava njegovu terapeutsku efikasnost kod benignehiperplazije prostate?................................................................................................................................... 1091Tatjana Gazibara, Aleksandra Filipovi , Vesna Kesi , Darija Kisi -Tepav evi , Tatjana PekmezoviRisk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer in the female population of Belgrade, Serbia: A case-control studyFaktori rizika od epitelijalnog karcinoma ovarijuma u ženskoj populaciji Beograda ................................. 1097Marko Banovi , Bosiljka Vujisi -Teši , Vuk Kuja i , Slobodan Obradovi ,Zdenko Crkvenac, Miodrag OstojiAssociation between aortic stenosis severity and contractile reserve measured by two-dimensional strain under low-dose dobutamine testingUticaj težine aortne stenoze na procenu kontraktilne rezerve procenjene pomo u dvodimenzionalnognaprezanja tokom niskodoznog dobutaminskog testa ................................................................................. 1103Vesna Mioljevi , Ljiljana Markovi -Deni , Ana Vidovi , Milica Jovanovi ,Tanja Toši , Dragica TominRisk factors for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization in hematologic patientsFaktori rizika od kolonizacije vankomicin-rezistentnog Enterococcus-a kod hematoloških bolesnika...... 1109Igor M. Nikoli , Goran M. Tasi , Vladimir T. Jovanovi , Nikola R. Repac, Aleksandar M. Jani ijevi ,Vuk D. Š epanovi , Branislav D. NestoroviAssessing the quality of angiographic display of brain blood vessels aneurysms compared tointraoperative stateProcena kvaliteta angiografskog prikaza aneurizmi krvnih sudova mozga u odnosu na intraoperativninalaz............................................................................................................................................................. 1117Boban Djordjevi , Marijan Novakovi , Milan Milisavljevi , Saša Mili evi , Aleksandar MalikoviSurgical anatomy and histology of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle for blepharoptosiscorrectionHirurška anatomija i histologija miši a podiza a gornjeg kapka u korekciji blefaroptoze ......................... 1124Vojislava Neškovi , Predrag Milojevi , Dragana Uni -Stojanovi , Ivan Ili , Zoran SlavkoviHigh thoracic epidural anesthesia in patients with synchronous carotid endarterectomy and off-pump coronary artery revascularizationVisoka torakalna epiduralna anestezija kod bolesnika sa istovremenom karotidnom endarterektomijomi off-pump revaskularizacijom koronarne arterije........................................................................................ 1132

Strana MLXXX VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

GENERAL REWIEV / OPŠTI PREGLEDŽana Stankovi , Miroslava Jašovi -Gaši , Dušica Le i -ToševskiPsychological problems in patients with type 2 diabetes – Clinical considerationsPsihološki problemi bolesnika sa dijabetesom tipa 2 – klini ka razmatranja.............................................. 1138

CURRENT TOPIC / AKTUELNA TEMALjiljana Gojkovi Bukarica, Dragana Proti , Vladimir Kanjuh, Helmut Heinle, Radmila Novakovi ,Radisav Š epanoviCardiovascular effects of resveratrolKardiovaskularni efekti rezveratrola ........................................................................................................... 1145

CASE REPORTS / KAZUISTIKASvetlana Jovanovi , Zorica Jovanovi , Jelena Paovi , Vesna Stankovi eperkovi , Snežana Peši ,Vujica MarkoviTwo cases of uveitis masquerade syndrome caused by bilateral intraocular large B-celllymphomaDva bolesnika sa maskiranim sindromom uveitisa nastalim kao posledica obostranog intraokularnoglimfoma velikih B- elija.............................................................................................................................. 1151Ljubinka Jankovi Veli kovi , Irena Dimov, Dragan Petrovi , Slavica Stojnev, Stefan Da i ,Stefan Veli kovi , Vladisav StefanoviStromal reaction and prognosis in acinic cell carcinoma of the salivary glandStromalna reakcija i prognoza acino elijskog karcinoma pljuva ne žlezde................................................ 1155Aleksandra Lovrenski, Mirna Djuri , Ištvan Klem, Živka Eri, Milana Panjkovi , Dragana Tegeltija,Djordje PovažanMultisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis coexisting with metastasizing adenocarcinoma of thelung: A case reportMultisistemska histiocitoza Langerhansovih elija udružena sa metastaziraju im adenokarcinomomplu a ............................................................................................................................................................ 1159Mihailo Vukmirovi , Lazar Angelkov, Filip Vukmirovi , Irena Tomaševi VukmiroviSuccessful implantation of a biventricular pacing and defibrillator device via a persistent leftsuperior vena cavaUspešna ugradnja resinhronizaciono-defibrilatorskog aparata preko perzistentne leve gornje šuplje vene ... 1162

HISTORY OF MEDICINE / ISTORIJA MEDICINEGoran Brajuškovi , Dušanka Savi Pavi evi , Stanka RomacThe 60th anniversary of the discovery of DNA secondary structureOtkri e sekundarne strukture molekula DNK – 60-godišnjica.................................................................... 1165

PISMO UREDNIKU / LETTER TO THE EDITOR .................................................................................. 1171

BOOK REVIEW / PRIKAZ KNJIGE......................................................................................................... 1175

UPUTSTVO AUTORIMA / INSTRUCTIONS TO THE AUTHORS....................................................... 1177

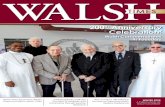

Watson & Crick`s deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) model in 1953The discovery in 1953 of the double helix, the twisted-ladder structure of DNA, byJames Watson and Francis Crick marked a milestone in the history of science andgave rise in modern molecular biology, wich is largely concerned withunderstanding how genes control biochemical processes within cells. This year 60thanniversary of this discovery has been marked around the world (see pages 1165–70).

Watson-ov i Crick-ov model dezoksiribonukleinske kiseline (DNK) iz 1953. godineOtkri e Watson-a i Crick-a iz 1953. godine da DNK ima strukturu dvostruke spi-rale u obliku uvijenih stepenica, ozna ilo je prekretnicu u istoriji nauke i dovelo dobrzog razvoja moderne molekularne biologije i razumevanja na ina na koji genikontrolišu biohemijske procese unutar elije. Ove godine, širom sveta obeležena je60. godišnjica tog otkri a (vidi str. 1165–70).

Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1081–1084. VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1081

Correspondence to: Sonja Pr i , Department Of Dermatovener ology, Institute for Child and Youth Health Care of Vojvodina, HajdukVeljkova 10, Novi Sad, Serbia. Phone: +381 21 488 0444. Fax: +381 21 520 436. E-mail: [email protected]

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E S UDC: 616.9-053.2-02:578.822]:616.511DOI: 10.2298/VSP110607026P

Epidemiological and clinical features of erythema infectiosum inchildren in Novi Sad from 2000 to 2009Epidemiološke i klini ke karakteristike infektivnog eritema kod dece u Novom

Sadu u periodu 2000–2009.

Sonja Pr i *, Zorica Gajinov†, Bogdan Zrni ‡, Anica Radulovi *, Milan Mati †,Verica Djuran†

*Department of Dermatovenerology, Institute for Child and Youth Health Care ofVojvodina, Novi Sad, Serbia; †Clinic of Dermatovenerology Diseases, Clinical Center of

Vojvodina, Novi Sad, Serbia; ‡Faculty of Medicine, University of Banja Luka, BanjaLuka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Abstract

Background/Aim. Erythema infectiosum (EI) is a com-mon childhood illness, caused by human parvovirus B19.It occurs sporadically or in epidemics and is characterizedby mild constitutional symptoms and a blotchy or maculo-papular lacy rash on the cheeks (slapped-cheek) spreadingprimarily to the extremities and trunk. The aim of ourstudy was to analyse the epidemiological and clinical char-acteristics of erythema infectiosum in children. Methods.This study included 88 children observed in the Depart-ment of Dermatology of the Institute for Child and YouthHealth Care of Vojvodina, in Novi Sad, during the periodJanuary 2000–December 2009. We compared the dataabout the clinical characteristics during and after the out-break of EI observed from December 2001 to September2002. The data were retrieved from the hospital database.Results. During the study period, EI was detected in 88children (44 females and 44 males), 0.213% of the totalnumber of 41,345 children observed in the Department ofDermatology. An outbreak of erythema infectiosum wasobserved from December 2001 to September 2002, with

the peak frequency in April and May 2002 and 39 diag-nosed cases, and stable number of cases from 2005 to2009 (a total of 49 diagnosed cases). The average age ofinfected children was 7.59 ± 3.339. Eleven (12.5%) chil-dren were referred from primary care pediatricians withthe diagnosis of urticaria or rash of allergic origin. Themost constant clinical sign was reticular exanthema on thelimbs, present in 100% of the cases, followed by 89.77%of cheek erythema. Pruritus was present in 9.09% of thechildren, mild constitutional symptoms in 5.68% and pal-pable lymph glands in 3.41% of the children. In all thecases the course of the disease was without complications.Conclusion. The results of this study confirm the pres-ence of EI (the fifth disease) in our area with a mildcourse in the majority of patients. Since the diagnosis ofEI is usually based on clinical findings, continuing medicaleducation of primary health care pediatricians is essentialfor reducing the number of misdiagnosed cases.

Key words:erythema infectiosum; child; serbia; disease outbreaks;epidemiology; drug therapy; prognosis.

Apstrakt

Uvod/Cilj. Infektivni eritem je de ja osipna bolest, koja sekarakteriše homogenim, veoma izraženim eritemom obrazai mrežastim osipom, lokalizovanim na ekstremitetima i tru-pu, bez zna ajnijeg poreme aja opšteg stanja. Izaziva jeparvovirus B19. Javlja se sporadi no ili periodi no, u vidumanjih epidemija. Cilj našeg rada bio je da se utvrde epide-miološke i klini ke karakteristike infektivnog eritema. Me-tode. Studijom je bilo obuhva eno 88 obolele dece 44 de-voj ice i 44 de aka koja su se javila na pregled u Odseku zadermatologiju, Instituta za zdravstvenu zaštitu dece i omla-dine u Novom Sadu, u periodu od januara 2000. do decem-

bra 2009. godine. Podaci o klini kim karakteristikama bole-snika dijagnostikovanih tokom epidemije 2001/2002. godi-ne (39 obolelih) pore eni su sa periodom od 2005 do 2009.godine kada je broj dijagnostikovanih slu ajeva bio ujedna-en (ukupno 49). Rezultati. Infektivni eritem dijagnostiko-

van je kod 0,213% dece od ukupno 41 345 pregledane deceu Odseku za dermatologiju. Od decembra 2001. do septem-bra 2002. godine došlo je do naglog porasta broja obolelihod infektivnog eritema, dok je najve i broj obolelih bio umaju i aprilu 2002. godine. Prose an uzrast obolele dece iz-nosio je 7,59 ± 3,339 godine. Ukupno 12,5% bolesnikaupu eno je pod sumnjom na urtikariju ili osip alergijskogporekla. Mrežast osip na ekstremitetima bio je prisutan kod

Strana 1082 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

Pr i S, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1081–1084.

svih obolelih, eritem obraza kod 89,77%, svrab je bio pri-sutan kod 9,09% dece, blagi opšti simptomi infekcije kod5,68%, a limfadenopatija kod 3,41% dece. Nisu zabeleženekomplikacije oboljenja. Zaklju ak. Sva obolela deca imalasu karakteristi nu klini ku sliku i dobro udan tok bolesti.Pošto se dijagnoza infektivnog eritema u de jem uzrastu po-stavlja pretežno na osnovu klini ke slike, naglašavamo važ-

nost kontinuiranog obrazovanja pedijatara koji pružaju pri-marnu zdravstvenu zaštitu sa klini kim tokom i diferencijal-nom dijagnozom ovog oboljenja.

Klju ne re i:eritem, infektivni; deca; srbija; epidemije;epidemiologija; le enje lekovima; prognoza.

Introduction

Erythema infectiosum (EI) is an acute childhood illness,characterized by blotchy or maculopapular rash starting oncheeks, spreading to extremities and the trunk, giving a typicalslapped cheek appearance and lacy configuration on limbs.Constitutional symptoms are mild 1, 2. The disease is caused byhuman parvovirus B19 (Pv B19), the route of natural transmis-sion is presumably the respiratory route, and parenteral andtransplacental transmission have been proved, as well. A re-ceptor molecule for B19 is glycolipid antigen on the erythro-cyte surface, and hosts with the decreased production or in-creased destruction of red blood cells (such as hemolytic ane-mia or pure red cell aplasia due to various causes) are prone toaplastic crises and protracted severe anemia upon infectionwith human Pv B19 2–4. In immunocompromised hosts thecourse of Pv B19 infection can be severe, even caused by he-mophagocytic syndrome 4. Acute infection during pregnancycan result in hydrops fetalis (risk estimated in 10% of cases) 5.The incubation period is 4–14 days, during which patients areinfectious, only prior to the onset of the rash 6, 7.

EI usually develops suddenly, prodromal symptoms aremild or may be absent. The course of the disease is three-phasic: facial “slapped-cheeks“ rash, followed by lacy or re-ticular rash of the upper extremities and an evanes-cence/recrudescence stage. Eruption is pruritic in about 15%of children. EI usually lasts for 2 weeks, but can recur withmechanical, physical or emotional triggers. The diagnosis ofEI is usually made on the basis of the characteristic clinicalfeatures. The differential diagnosis includes the other viralrashes (rubella, measles, enteroviral infection), scarlet fever,cheek erysipelas, hypersensitivity reaction (urticaria, drugreaction or allergic exanthemata) and collagen vascular dis-eases (systemic lupus erythematosus). Due to the mild courseonly symptomatic treatment is necessary (antipyretics, anti-histamines) 1, 7, 8.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the Depart-ment of Dermatology, Institute for Child and Youth HealthCare of Vojvodina in Novi Sad, as tertiary referral center forthe South Ba ka region in the Province Vojvodina. Age, sexdistribution, the presence of constitutional symptoms andclinical characteristics of the disease were retrieved from themedical records of all EI patients diagnosed between January2000 and December 2009. The data from the period 2005–2009, and those previously published for the period 2000–2004 were compared 9.

All the patients were diagnosed by one of the derma-tologists (authors), based on the clinical findings in the ma-jority of cases. A total of 12 patients (2 during the period of2005–2009) serum samples were additionally analyzed usingSERION ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)classic parvovirus B19 IgG/IgM quantitative and qualitativetests for identification of specific antibodies against humanparvovirus B19. Complement-fixing reactions (CFR) to vi-ruses (Rubella, Adenovirus, Coxsackie virus) were per-formed in 5 children, with constitutional symptoms and pal-pable lymph nodes.

Results

During the study period (from the beginning of 2000 tothe end of 2009), at the Department of Dermatology, the totalnumber of first visits was 41,345 and erythema infectiosumwas diagnosed in 88 children (0.213%). Figure 1 shows the

number of patients during a 10-year period. Patients with EIwere not observed within 2000, and sporadic cases emergedby the end of 2001. A sudden outbreak was noted from De-cember 2001 to September 2002 with the highest number ofcases recorded in April and May, 2002 9. In a subsequent 5year period (2005–2009) EI was diagnosed in 49 children, 22girls and 27 boys, average age being 7.98 ± 3.554 years.During a total period of 10 years, the average age of EI pa-tients was 7.59 ± 3.339 years, with the majority of patients inthe 5–10 years group, and equal sex ratio (44 girls and 44boys affected).

During the whole study period 11 children (12.5%)were referred from primary care pediatricians with the diag-nosis of urticaria or rash of allergic origin, 7 during the pe-

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009

the

No o

f pat

ient

s

Fig. 1 – The number of patients with erythema infectiosumin a 10-year research period.

Volumen 70, Broj 12 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1083

Pr i S, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1081–1084.

riod of outbreak and 4 patients (8.16%) during the secondperiod. These children were on diet and recevied oral anti-histamines, while 5 of them (5.68%) had been prescribedparenteral corticosteroid treatment, 2 (4.08%) in the secondperiod after the outbreak. Mild pruritus was present in 8(9.09%) of the children and mild constitutional symptomswere present in only 5 (5.68%) of the children. All the pa-tients had typical clinical picture, and atypical forms of thedisease were not recorded in the studied pediatric population(ie, papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome or acrope-techial syndrome) (Figure 2). The most constant clinical sign

was reticular exanthema on upper extremities, present in100% of the cases, followed by intensive erythema of thecheeks (slapped-cheek appearance) in 79 (89.77%). Exan-thema on trunk and extremities was present in 12 (13.63%)children. One (1.14%) patient had palmar and plantar ery-thema. Occipital lymphadenopathy was present in 3 (3.41%)children. Clinical findings of EI patients from the study pe-riod 2005–2009 are presented in Table 1. All the 12 tested

children were positive for IgM antibodies against humanparvovirus B19, confirmative of the acute Pv B19 infection.

CFR assays for Rubella, Adenovirus and Coxsackie werenegative in all the five children tested. On control examina-tion after 14 days rash was resolved in all the patients, whilephysical examination showed normal results.

Discussion

Infection with PvB19 is ubiquitous and occurs world-wide. EI is common, mildly contagious, and occurs sporadi-cally or in epidemics 1. The rise in the number of EI patientsnoted during the period December 2000 to May 2002, withthe peak in April and May 2001, was not repeated in the laterstudy period when an average number of patients was rela-tively stable 9. That is in concordance with data form the lit-erature on EI epidemics occurring in cyclical fashion, every4–7 years, with more frequent outbreaks in winter andspring 3, 6, 8, 9. Localized outbreaks among schoolchildren arecommon 6. The first outbreak of EI in Serbia was reportedfrom October 1987 to May 1988 that occurred among schoolchildren in part of Belgrade 10. The majority of our EI pa-tients were 5–10 years old, that is in concordance with lit-erature data 1. No gender difference in susceptibility to EIwas noted in the literature, similar to our case series 5. Lacyexanthema on proximal extremities was the most prominentsymptom noted in all our patients, that disagrees with thestudy by Revilla et al. 11 where erythema of the cheeks(slapped-cheek appearance) was the most frequent one. Lacyexanthema of the extremities was the most frequent in thestudy by Bukumirovi et al. 10, and in our previous report,also 9. Palmar and plantar erythema occurs only rarely in EI6. In our study it was present only in one boy during the2001–2002 outbreak, and in was not observed a later period9. None of the children had any further complications. In asimilar study by Rewilla et al. 11 the illness had a mildcourse. The only difference in clinical presentation of EI pa-tients between the two study periods is that exanthema af-fecting both trunk and limbs occurred more frequently duringthe study period 2005–2009 than in the previous 5 years(18.37% and 7.69% correspondingly) 9.

In our study lymph nodes enlargement was present in3.41% of the patients (occipital lymph nodes), and in thosechildren serological analyses for Rubella, Adenovirus andCoxsackie virus were performed, proved negative in all ofthem. In all 12 tested serum samples Pv B19 infection wasserologically detected. According to the literature, labora-tory proof of Pv B19 infection is not necessary in caseswith characteristic clinical picture and uncomplicatedcourse in previously healthy children 1, 7, 8. Therefore, EIshould not be a diagnostic problem because of its charac-teristic presentation and the course of the illness. EI de-scription as “geographical map with lakes” as the most pic-turesque of all the rashes, together with phasic course withslapped cheeks or sun-burnt facial aspect preceding rash, arepathognomonic, and seen only in this disease 1, 7, 8. However,the number of patients had been referred to the Institutebecause of suspected allergic rash, and a relatively largeproportion of children (12.15%) had been previously pre-scribed antihistamine and corticosteroid treatment and

Fig. 2 – Erythema infectiosum in a 6-year-old boy.

Table 1Clinical findings of erythema infectiosum (EI) from

2005 to 2009ChildrenClinical findings of EI n %

Pruritus 4 8.16Constitutional symptoms 3 6.12Exanthema on upper extremities 49 100.00Exanthema on extremities and trunk 9 18.37Erythema of the cheeks 45 91.84Palmar-plantar erythema 0 0Occipital lymphadenopathy 1 2.04Total 49 100.00

Strana 1084 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

Pr i S, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1081–1084.

elimination diet. Even though EI is not a rare disease, itappears periodically every 4–7 years in the form of spo-radic epidemics lasting for several months, that could bethe reason not to be easily recognized among primaryhealth care physicians. Albeit, during 2001/2002 outbreakwhen 18% of children were referred from primary care assuspect allergic reaction, in the period 2005–2009 propor-tion of unrecognized cases decreased to 8%. That is an en-couraging result pointing that previous epidemics in-creased awareness and enhanced recognition of EI amongnon-dermatologists 9.

Conclusion

The results of this study confirm the presence of EI (thefifth disease) in our area with a mild course in the majority ofpatients. Since the diagnosis of EI is usually based on clini-cal findings, the continuing medical education of primaryhealth care pediatricians is essential for reducing the numberof misdiagnosed cases. Further studies within longer obser-vation periods and larger groups of patients are necessary todetermine the epidemiological and clinical characteristics oferythema infectiosum in Serbia.

R E F E R E N C E S

1. Vafaie J, Schwartz RA. Erythema infectiosum. J Cutan MedSurg 2005; 9(4): 159 61.

2. Drew WL. Parvoviruses. In: Wilson WR, editor. Current diag-nosis and treatment in infectiosus diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill Co; 2001. p. 451 3.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Par-vovirus B19. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS,editorss. 2009 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infec-tious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Acad-emy of Pediatrics; 2009. p. 491 3.

4. Heegaard ED, Brown KE. Human parvovirus B19. Clin Micro-biol Rev 2002; 15(3): 485–505.

5. Anderson LJ, Hurwitz ES. Human parvovirus B19 and preg-nancy. Clin Perinatol 1988; 15(2): 273 86.

6. Mancinci A. Exanthems in childhood: an update. Pediatr Ann1998; 27(3):163 70.

7. Wiss K. Erythema infectiosum and Parvovirus B19 infection.In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Freedberg IM, Austen KF,

editors. Dermatology in general medicine. 5th ed. New York:Mc Graw-Hill; 2003. p. 2409 13.

8. Zellman G. Erythema Infectiosum (Fifth Disease). EmedicineDermatology (journal series online). 2002. Available at:http://author.emedicine.com/derm/topic 136.htm.

9. Prcic S, Jakovljevi A, Djuran V, Gajinov Z. Erythema infectio-sum in children: a clinical study. Med Pregl 2006; 59(1 2):5 10. (Serbian, English)

10. Bukumirovi K, Radosavljevi M, Milki V, Antonijevi B, Polak D, DodiM, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of human parvovirus B19.Report of an epidemic of erythema infectiosum in the area of Bel-grade. Srp Arh Celok Lek 1992; 120(5 6): 171 4. (Serbian)

11. Revilla G, Carro G, Sanchez DM, Galan C, Nebreda M. Outbreakof infectious erythema at a urban health center. Aten Primaria2000; 26(3): 172 5. (Spanish)

Received on Jun 7, 2011.Revised on Avgust 18, 2011.

Accepted on September 5, 2011.OnLine-First May, 2013.

Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1085–1090. VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1085

Correspondence to: Nikola Stankovi , Mother and Child Health Care Institute, Cetinjska 32/7, 11 000 Belgrade, Serbia.Phone: +381 60 013 57 13. E-mail: [email protected]

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E UDC: 616-036.22::616.61-076DOI: 10.2298/VSP110614027S

Histomorphological and clinical study of primary and secondaryglomerulopathies in Southeast Serbia (20-year period of analysis)Histomorfološko i klini ko ispitivanje primarnih i sekundarnih glomerulopatija

u jugoisto noj Srbiji (analiza u periodu od 20 godina)

Nikola Stankovi *, Predrag Vlahovi †, Vojin Savi ‡

*Mother and Child Health Care Institute, Belgrade, Serbia; †Center for MedicalBichemistry, ‡Institute of Nephrology and Hemodialysis, Clinical Center Niš, Niš, Serbia

Abstract

Background/Aim. Epidemiological studies of renal biop-sies have been performed to follow up the incidence ofglomerular diseases on a specified territory and to comparethe obtained results with results from other regions. Theaim of this study was to analyze the frequency of certainhistopathophysiological types of glomerular diseases on theterritory of Southeast Serbia. Methods. In a 20-year period(1986–2006), 316 kidney biopsies were performed in pa-tients with clinicall signs of impaired renal function, inSoutheast Serbia. On average 1.6 biopsies were made peryear per 100 000 inhabitants. Results. Biopsies of adult pa-tients represented 88% of all biopsies, biopsies in children(aged under 18 years) represented 8%, while biopsies of eld-erly patients (more than 60 years) represented 4% of all bi-opsies. The predominance of male patients was describedwith male/female ratio of 1.4. The most frequent clinicalmanifestation in patients at the time of biopsy were ne-phrotic syndrome (42.5%), and asymptomatic proteinuriaand/or hematuria (31.3%) and nephritic syndrome (14.9%).The most common glomerular disease was IgA nephropa-thy with an incidence of 21.5% of total biopsy diagnosedglomerulopathies, followed by: membranous glomerulone-phritis (12.6%), focal segmental proliferative and sclerosingglomerulonephritis (10.7%), lupus nephritis (8.4%), nephro-angiosclerosis (7.0%), mesangio-proliferative glomerulone-phritis (6.1%), minimal change disease (2.8%), mesangio-capillary glomerulonephritis (2.3%). Conclusion. The fre-quency of certain histopathologic findings significantly cor-related with data from studies that we used for comparison,with the exception of minimal change disease whose inci-dence in our study was smaller.

Key words:kidney diseases; glomerulonephritis; biopsy;histocytochemistry; epidemiology; serbia.

Apstrakt

Uvod/Cilj. Epidemiološke analize biopsija bubrega imajuza cilj pra enje u estalosti pojedinih glomerulskih bolesti naodre enom podru ju i upore ivanje dobijenih rezultata sarezultatima iz drugih regiona. Cilj ovog istraživanja bio je dase analizira u estalost pojedinih histopatofizioloških tipovaglomerulskih bolesti na teritoriji jugoisto ne Srbije. Meto-de. U periodu od 20 godina (1986–2006), na teritoriji jugoi-sto ne Srbije, ura ena je biopsija bubrega kod 316 bolesnikakod kojih su klini ki bili prisutni znaci poreme ene bubrež-ne funkcije. Prose no je ura eno 1,6 biopsija godišnje na100 000 stanovnika. Rezultati. Od ura enih biopsija 88%su bile biopsije kod odraslih osoba, 8% kod dece, dok subiopsije kod starijih osoba inile 4%. Predominacija boles-nika muškog pola, iskazana muško/ženskim odnosom biop-siranih bolesnika iznosila je 1,4. Najzastupljenije klini keprezentacije kod bolesnika u vreme biopsije bile su nefrotskisindrom (42,5%), zatim asimptomatska proteinurija i/ilihematurija (31,3%) i nefritski sindrom (14,9%). Naju estalijaglomerulska bolest bila je IgA nefropatija sa u estaloš u od21,5% od ukupnog broja biopsijom dijagnostifikovanihglomerulopatija, a sledili su: membranski glomerulonefritis(12,6%), fokalnosegmentalni proliferativni i skleroziraju iglomerulonefritis (10,7%), lupus nefritis (8,4%), nefroangio-skleroza (7,0%), mezangioproliferativni glomerulonefritis(6,1%), bolest minimalnih promena (2,8%), mezangio-kapilarni glomerulonefritis (2,3%). Zaklju ak. U estalostpojedinih patohistoloških nalaza u zna ajnoj meri koreliše sapodacima iz studija koje su nam služile za komparaciju, saizuzetkom bolesti minimalnih promena ija je incidencija ni-ža u našoj studiji.

Klju ne re i:bubreg, bolesti; glomerulonefritis; biopsija;histocitohemija; epidemiologija; srbija.

Strana 1086 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

Stankovi N, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1085–1090.

Introduction

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a bilateral, non-bacterial,non-suppurative inflammation of kidney which primarily af-fects glomerulus and then the other kidney structures.

Histological features are the most important criterionfor the nomenclature and classification of glomerular dis-ease. In addition to localization, the histological characteris-tics define the nature of glomerular lesion as well as cellproliferation, deposit of immune complexes or extracellularcomponents lesions.

Immune processes underlie most cases of primary GN,but they are also present in many secondary events in theglomerulus. Therefore, the division of etiopathologic mecha-nisms of glomerulopathy is reduced to immunological andnon-immunological 1.

Glomerular lesion is clinically expressed with a rela-tively small number of signs and symptoms. There are fivemain clinical syndromes which may be manifested in glo-merular disease: acute GN syndrome (acute nephritic syn-drome), syndrome of rapidly progressive GN, nephrotic syn-drome, asymptomatic urinary abnormalities (asymptomaticproteinuria and hematuria) and the syndrome of chronic GN.

The diagnosis of glomerular disease involves a com-plete understanding of the clinical condition of the patient,laboratory diagnostics, immunological and morphologicalstudies. Diagnosis based only on the clinical manifestationsmay be unsuccessful because different glomerular diseasesare characterized by similar or the same clinical presentation.On the other hand, the same glomerular disease may be pre-sented differently in different patients 2.

Therapeutic approach, response to therapy and progno-sis, depend on the type of GN. The frequency of certainforms of GN is different in different geographical areas andassociated with genetic and environmental factors.

This retrospective study was conducted with the aim todetermine the frequency of certain types of glomerular dis-ease in Southeast Serbia on the basis of which may be possi-ble to predict the response to therapy and prognosis.

Methods

During a 20-year period (1986–2006), 316 kidney biop-sies were performed in patients with clinically and laboratoryshown signs of some primary or secondary glomerulopathy(nephritic or nephrotic syndrome, syndrome of rapide pro-gressive GN and asymptomatic hematuria or proteinuria).All biopsies were done at the Institute of Nephrology andHemodialysis in Clinical Center Niš and the whole tissue bi-opsy material was processed in the histopathological labora-tory of this institute. The histopathologist has always takenbiopsy material from a patient and prepared it for light mi-croscopic analysis, immunofluorescence and if necessary forelectron microscopy.

The same method for taking biopsy material was al-ways used – blind percutaneous renal biopsy with previousintravenous pyelography or ultrasound examination. In par-allel to light microscopy, immunofluorescence with IgG,

IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, fibrinogen, albumin, kappa and lambdachains was always done. Electron microscopy was performedin 3–4% of cases when it was possible (during the difficulteconomic crisis) and when indications were present (othermorphological examination aroused suspicion of a change inthe GBM structure; existence of deposit which could notbeen precisely localize in immunofluorescence findings).

Of the total number of samples, 214 biopsies had posi-tive histopathological findings in the glomeruli, while 102findings were not included in this study. Only those caseswho clearly indicated the existence of glomerulopathy wereincluded. The patients whose clinical presentation and labo-ratory findings did not fit into diagnosis of glomerulopathyor tubulointerstitial changes were clinically and histopa-thologicaly confirmed, were not included in this study.Among samples which were not included in the study, 26had negative glomerular findings, 50 of them did not haveenough material for analysis, and in 26 of them findings intubulointerstitial system were dominant (chronic pyelone-phritis, acute tubular necrosis, balkan endemic nephropathy,etc).

Immunological tests included measurements of serumimmunoglobulins concentration, complement fractions in se-rum, immune complexes while the presence of certain auto-antibodies were detected by direct immunofluorescence.Immunoglobulins and complement fractions were measuredby the nephelometric method (II BEN nefelometar – Dade-Behring, Magdeburg, Germany). Immune complexes weremeasured by the deposition of immunoglobulins with poly-ethylene glycol (PEG-6000). The presence of autoantibodiesin biopsy specimens was performed by direct immunofluo-rescence with autoantibodies labeled with fluorescein(FITC).

Other analysis have included detailed medical history,routine biochemical tests as well as other relevant testing.The following findings have been specifically analyzed: du-ration of clinical manifestations of impaired kidney function,previous diseases, edema, the appearance of micro- ormacrohematuria, blood pressure, finding of proteinuria, hy-poproteinemia and hipoalbuminemia findings, and elevatedserum cholesterol and triglycerides.

The data were analyzed by descriptive statistics usingthe program Sigma Stat.

Results

Of 214 patients with biopsy confirmed diagnosis of aglomerulopathy, 125 (58.4%) were males and 89 (41.6%)females.

Age and gender distributions are shown in Table 1. Agedata were available for 204 patients. Most of the patientswere aged 31–50 years, a total of 98 patients (61 males and37 females), that was 45.8% of the total number of biopsieswith positive findings. Within this age group, most weremale patients with primary proliferative GN (33% or 33.7%).

Clinical presentation of the patients with GN is shownin Table 2. Of the 7 described syndromes, the most commonwas nephrotic syndrome in 91 (42.5%) patients.

Volumen 70, Broj 12 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1087

Stankovi N, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1085–1090.

Of a total number, 140 biopsied patients had pathologi-cal findings of the primary forms of GN, which was 65.4%,of which the proliferative forms were much more frequent(Table 2). Secondary forms of GN had 22 (10.3%) patients,non-immunological glomerular lesions (diabetes, amyloido-sis, and hypertensive changes) were recorded at 22 (10.3%)patients, while in the other group, terminally damaged renalparenchyma (end stage renal diseases-ESRD) occurred in 13(6.1%) of the cases.

Primary nonproliferative forms of GN were found in 41of 214 patients (29.3% of all the patients with primary GN).The most frequent nonproliferative GN was membranousGN, followed by focal segmental sclerosis and minimalchange disease (Table 3).

Membranous GN was present in 27 patients (7 femalesand 20 males) of which hypertension was registered in 13(severe stages in 4), edema in 23, hematuria in 22, while ne-phrotic proteinuria was present in 15 of the patients. The

Table 1Age and gender distribution of the biopsied patients in the groups of glomerular disease

18 years 19–30 years 31–50 years 51–60 years > 61 years All agesType of glomerulopathy m f m f m f m f m f m fPrimary nonproliferative GN 2 – 8 – 12 3 6 6 3 1 31 10Primary proliferative GN 6 2 13 14 33 12 8 – 3 – 68 31Secondary GN – 2 – 4 3 11 – 2 – – 3 19Non-immunological and otherglomerulopathies 2 1 5 8 13 10 2 6 1 3 23 29

10 5 26 26 61 35 16 14 7 4 125 89GN – glomerulonephritis; m – male; f – female

Table 2Clinical syndrome at the time of biopsy in the patients with biopsy findings of

glomerular lesionPatientsClinical syndrome n %

Nephrotic 91 42.5Nephritic 32 14.9Asymptomatic proteinuria and hematuria 67 31.3Asymptomatic proteinuria 7 3.3Asymptomatic hematuria 2 0.9Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis 2 0.9Chronic renal failure 13 6.2Type of glomerular lesionPrimary nonproliferative GN 41 19.1Primary proliferative GN 99 46.3Secondary GN 22 10.3Non-immunological glomerulopathy 22 10.3Other 30 14.0

GN – glomerulonephritis

Table 3Glomerular diseases in the biopsied patients

PatientsType of glomerulopathy Glomerular diseases n %Minimal-change disease 6 2.8Focal segmental sclerosis 8 3.7Primary nonproliferative GNMembranous GN 27 12.6Focal segmental proliferative and sclerosing GN 23 10.7Endoteliomesangial GN 10 4.7Mesangioproliferative GN 13 6.1IgA nephropathy 46 21.5Mesangiocapillary GN 5 2.3

Primary proliferative GN

Rapidly progressive GN 2 0.9Lupus GN 18 8.4

Secondary GN Henock-Schoenlein purpura 4 1.9Nephroangiosclerosis 15 7.0Diabetic nephropathy 4 1.9Non-immunological glomerulopathyAmyloidosis 3 1.4

Other

End-stage glomerulonephritisSy. AlportPostpartal thrombotic microangiopathyStatus after kidney transplantationUnknown entity

13211

13

6.10.90.50.56.1

GN – glomerulonephritis

Strana 1088 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

Stankovi N, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1085–1090.

findings of immunofluorescence of IgG were positive in 25of the patients.

Detection of primary proliferative GN was present in 99patients of 214 which is 70.7% of the biopsied patients withfindings of primary glomerulonephritis. The most commonform of primary proliferative GN was IgA nephropathy, thenfocal segmantal praliferative and sclerosing GN, mesangio-proliferative GN, endoteliomezangial GN, mesangiocapillaryGN and rapidly progressive GN (Table 3).

IgA nephropathy was diagnosed in 46 patients (14 fe-males and 32 males). The youngest patients belonged to theage group of 11–20 years while the oldest were between 51and 60 years. Hypertension was present in 21, edema in 10,the finding of hematuria was present in all the patients, whileproteinuria greater than 3.5 g/L was present in 8 patientswith this finding. The largest number of light microscopyfindings belonged to the group with focal segmental-proliferative and sclerosing GN. Second most frequent find-ings matched to focal segmental proliferative GN with mes-angial area lesions. Diffuse changes in the glomeruli, such asdiffuse proliferative and diffuse proliferative and sclerosingGN were registrated in a much lower number of cases. Ex-tracapillary proliferation with less than 50% of affected glo-meruli was observed in only one biopsy. Considering immu-nofluorescence findings all the patients of this group werepositive for IgA.

Secondary forms of GN were registered in 22 out of214 biopsied patients, which is 10.3%. The definitive diag-nosis in these cases was confirmed by other immunologicaltests (primarily by determining the presence of serum auto-antibodies). Out of 22 patients 18 had systemic lupus ery-thematosus, and 4 showed light microscopic signs of focalproliferative and sclerosing GN with changes in the skin andpositive immunofluorescence finding, which is definitelypointing on Henoch-Schonlein purpura (Table 3).

Lupus nephritis was present in 18 cases. All the patientswere females, aged 17 to 48 years. Hypertension was regis-trated in 7 of the patients, edema in 13, proteinuria andhematuria in all the patients. Serum levels of C3 and C4 werereduced in most patients, while immune complexes and anti-nuclear antibodies were present in 9 of the patients to whomthese measurements were made. Non-immunological andother glomerulopathies were diagnosed in 52 patients, whichis 24.3%. Nephroangiosclerosis was diagnosed in 15 of thepatients, glomerular lesion in diabetic nephropathy in 4 pa-tients and glomerular lesions in amyloidosis in 3 patients(Table 3). Other biopsy material presented 14% of the biop-sied patients with positive findings and spoke in support ofend-stage GN (13 patients), Alport syndrome (2 patients),postpartal thrombotic microangiopathy (1 patient), status af-ter kidney transplantation (1 patient) or it was not possible tocome out of any known entity.

Discussion

Epidemiology of glomerular disease often shows somepeculiarities related to the geographic area, requiring a re-gional monitoring and mutual comparison of morbidity in

different territories. This study presents the frequency ofsome glomerular diseases diagnosed by biopsy of renal tissuein the period of 20 years in Southeast Serbia (population over1 million).

A large number of biopsy samples with insufficientmaterial is probably due to technical reasons of biopsy pro-cedure (blind percutaneous renal biopsy) and in some degreedisparage the preciseness of results. According to our results,1.6 biopsies were performed per 100 000 inhabitants peryear. This number is several times lower than the rates pres-ent in Western European countries like Spain 3, Italy 4,France 5, and the Czech Republic 6, or Australia 7, but issimilar to the rate of biopsies in Romania 8, whose registry isone of the few renal biopsy registers of Eastern Europe, andto the rate of biopsies obtained in another single centre studyconducted in Serbia, for the same period in a much largersample 9.

Biopsies in adult patients represented 88% of all biop-sies, biopsies in children (aged under 18 years) represented8%, while the biopsies in elderly patients (more than 60years) represented 4% of all biopsies (Table 1). This rela-tionship between the number of biopsies of children and theelderly is quite different from the relationship presented inthe Spanish registry of renal biopsies, where renal biopsy inchildren represented 7% and 22% in the elderly 3. These re-sults show predominance of adults in the biopsied patientsand that a large number of elderly patients and children weretreated on the basis of clinical manifestations.

The predominance of male patients is reported withmale/female ratio of 1.4, which is consistent with data fromother international studies 3,7,10. From this, we can excludesecondary forms of glomerulonephritis, in which the pre-dominance of females was present, what can be explained bya much higher incidence of systemic lupus in women (Table1). However, male/female ratio is significantly different fromthe results obtained in another single centre study conductedin Serbia, for the same period in a much larger sample 9.

The most frequent clinical presentations in patients atthe time of biopsy were nephrotic syndrome (42.5%),asymptomatic proteinuria and/or hematuria (31.3%) andnephritic syndrome (14.9%). Other syndromes were signifi-cantly less frequent (Table 2). These data are consistent withthe results from the Spanish 3 and Czech register 6, as well aswith data from a Japanese study with 1850 biopsied patients.Also, data from another single centre study conducted inSerbia were similar, except that the incidence of nephroticsyndrome showed more pronounced dominance 9. However,the obtained data differ the results from the Italian registrywhere asymptomatic urinary abnormalities were more fre-quent than nephrotic syndrome 4 and the results from theRomanian registry where asymptomatic urinary abnormali-ties were less frequent than all other syndromes 8 (Table 4).

According to the literature and larger registers 4, 11–13, adifference between glomerular pathology in children, adultand elderly population is clearly visible. With the increase ofthe average number of years of biopsied patients reduces theincidence of primary GN and increases the incidence of sec-ondary forms of glomerular disease 3. The results of this

Volumen 70, Broj 12 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1089

Stankovi N, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1085–1090.

study confirm the distribution of certain glomerular patologicentities by the age of the group, although with less certainty,possibly due to the relatively small number of biopsied pa-tients (Table 2).

Similar to other registers, primary GN was proven inabout two thirds of biopsied patients 5, 6, while the secondaryform and non-immunological GN were equally presentedwith one tenth of biopsied patients.

The most common was IgA nephropathy with an inci-dence of 21.5% of total diagnosed glomerulopathies. Thisfrequency is most similar to the frequency of this entity inthe Netherlands 14 and Spain 3, and significantly lower thanreported in other European studies 4, 6, 8, 12. The most frequentclinical presentation among this patients was asymptomaticproteinuria and/or hematuria. All the patients with this histo-pathological diagnosis in our study were younger than 50years and only 4 of them were younger than 19 years.

Second most frequent glomerular disease, with an inci-dence of 12.6% was membranous glomerulopathy. The pa-tients in this group had a higher incidence of developed ne-phrotic syndrome than all other histopathological groups. Inthis group, histopathological finding of focal segmental pro-liferative and sclerosing GN with an incidence of 10.7%, wasthree times as frequent as isolated sclerosing form of thisfinding.

Despite the fact that a small number of biopsies wasperformed in children, the incidence of minimal change dis-ease was significantly lower (2.8%) than in other Europeanand world studies 3, 4, 7, 15. Conservative treatment untilsymptoms withdrawal and lack of technical conditions forelectron microscopy during the bombing of Serbia could bejust some of the reasons for these results.

In the group of secondary GN, lupus nephritis as adominant finding with the frequency of 8.4% is consistentwith all known registries. At the time of biopsy these patientspresented predominantlly nephrotic syndrome and asympto-

matic proteinuria and/or hematuria. The most frequent his-tological form of lupus nephritis was diffuse proliferative lu-pus nephritis (class IV) registered in 12 out of 18 patients,followed by focal segmental lupus nephritis (class III) in 4patients, mesangial lupus nephritis (Class II) in 1 patient, lu-pus nephritis without histological changes (Class I) in 1 pa-tient, while patients with membranousand (Class V) and end-stage lupus nephritis (Class VI) was not registrated. Al-though in a small sample and with lower frequency of mes-angial lupus nephritis, these those are similar to results ob-tained by Dimitrijevic et al. 16 on a sample of 311 patientswith lupus nephritis. In all the patients immunofluorescencefindings were positive primarily for IgG and C3 and in thelower percentage on IgA, IgM and C4. All of 18 biopsyspecimens with this findings belong to women aged between19 and 50 years, except in two cases of 17 and 14 years ofage (Table 3).

Conclusion

The obtained results lead to a conclusion that in the re-gion of Southeast Serbia the rate of biopsied patients in orderto obtain accurate histological diagnosis of clinically mani-fested glomerular disorders is significantly lower than inEuropean countries. Also, the age distribution of the biopsiedpatients is significantly different compared to western Euro-pean countries due to a small number of renal biopsies inchildren and in elderly. Primary proliferative forms of glo-merular disease is a dominant finding in the study group. Thefrequency of respective histopathologic findings significantlycorrelated with data from studies that we used for compari-son, with the exception of minimal change disease whose in-cidence in our study is lower. These data are a significantcontribution to the epidemiological analisys of glomerulardisease in Serbia and represent a database for comparisonand improvement of renal diseases treatment.

R E F E R E N C E S

1. Churg J, Bernstein J, Glassock JR. Renal disease, classi cation andatlas of glomerular disease. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1995.

2. Marcussen N, Olsen S, Larsen S, Starklint H, Thomsen OF. Repro-ducability of the WHO classi cation of glomerulonephritis.Clin Nephrol 1995; 44(4): 220 4.

3. Rivera F, Lopez-Gomez JM, Perez-Garc a R. Frequency of renalpathology in Spain 1994–1999. Nephrol Dial Transplant2002; 17(9): 1594–602.

4. Schena FP. Survey of the Italian Registry of Renal Biop-sies.Frequency of the enal diseases for 7 consecutive years.The Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology. Nephrol DialTransplant 1997; 12(3): 418–26.

5. Simon P, Ramée MP, Autuly V, Laruelle E, Charasse C, Cam G,Ang KS. Epidemiology of primary glomerular diseases in aFrench region. Variations according to period and age.Kidney Int 1994; 46(4): 1192 8.

6. Rychlík I, Jancová E, Tesar V, Kolsky A, Lácha J, Stejskal J, et al.The Czech registry of renal biopsies. Occurrence of renal dis-eases in the years 1994–2000. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19(12): 3040–9.

7. Briganti EM, Dowling J, Finlay M, Hill PA, Jones CL, Kincaid-Smith PS, et al. The incidence of biopsy-proven glomerulone-phritis in Australia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16(7):1364–7.

Table 4Most common clinical syndromes in the biopsied patients in 4 regions

Clinical syndrome Southeast Serbia (%) Romania (%)6 Italia (%)2 Another single centre in Serbia (%)9

Nephrotic syndrome 42.5 52.3 27.1 63.8Asymptomatic proteinuriaand/or hematuria 31.3 3.3 39.5 15.2

Nephritic syndrome 14.9 21.9 5.4 7.9Other syndroms 11.3 22.5 28.0 13.1

Strana 1090 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

Stankovi N, et al. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1085–1090.

8. Covic A, Schiller A, Volovat C, Gluhovschi G, Gusbeth-Tatomir P,Petrica L, et al. Epidemiology of renal disease in Romania: a10 year review of two regional renal biopsy databases. Neph-rol Dial Transplant 2006; 21(2): 419 24.

9. Naumovic R, Pavlovic S, Stojkovic D, Basta-Jovanovic G, Nesic V.Renal biopsy registry from a single centre in Serbia: 20 yearsof experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24(3): 877–85.

10. Malafronte P, Mastroianni-Kirsztajn G, Betônico GN, Romão JE Jr,Alves MA, Carvalho MF, et al. Paulista registry of glome-rulonephritis: 5-year data report. Nephrol Dial Transplant2006; 21(11): 3098–105.

11. Research Group on Progressive Chronic Renal Disease. Nationwide andlong-term survey of primary glomerulonephritis in Japan as ob-served in 1,850 biopsied cases. Nephron 1999; 82(3): 205–13.

12. Heaf J, Okkegaard H, Larsen S. The epidemiology and prognosisof glomerulonephritis in Denmark 1985–1997. Nephrol DialTransplant 1999; 14(8): 1889–97.

13. Werner T, Brodersen, HP, Janssen U. Analysis of the spectrum ofnephropathies over 24 years in a West German center based

on native kidney biopsies. Med Klin (Munich) 2009; 104(10):753 9.

14. van Paassen P, van Breda Vriesman PJ, van Rie H,Tervaert JW.Signs and symptoms of thin basement membrane nephropa-thy: A prospective regional study on primary glomerular dis-ease – The Limburg Renal Registry. Kidney Int 2004; 66(3):909–13.

15. Choi IJ, Jeong HJ, Han DS, Lee JS, Choi KH, Kang SW, et al. Ananalysis of 4,514 cases of renal biopsy in Korea. Yonsei Med J2001; 42(2): 247–54.

16. Dimitrijevi J, Dukanovi L, Kovacevi Z, Bogdanovi R, Maksi D,Hrvacevi R, et al. Lupus nephritis: histopathologic features,classification and histologic scoring in renal biopsy. Vojno-sanit Pregl 2002; 59(6 Suppl): 21 31.

Received on June 14, 2011.Revised on October 11, 2011.

Accepted on January 25, 2012.OnLine-First May, 2013.

Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1091–1096. VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1091

Correspondence to: Aleksandar Argirovi , Department of Urology, Clinical Hospital Center Zemun, Vukova 9, 11 080 Belgrade, Serbia.Phone: + 38162 23 66 59. E-mail: [email protected]

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E UDC: 616.65-08DOI: 10.2298/VSP110620029A

Does the addition of Serenoa repens to tamsulosin improve itstherapeutical efficacy in benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Da li dodavanje Serenoa repens tamsulosinu poboljšava njegovu terapeutskuefikasnost kod benigne hiperplazije prostate?

Aleksandar Argirovi *, Djordje Argirovi †

*Department of Urology, Clinical Hospital Center Zemun, Belgrade, Serbia;†Outpatient Urology Clinic “Argirovi ”, Belgrade, Serbia

Abstract

Background/Aim. It has been observed that a large num-ber of patients with low urinary tract symptoms due to be-nign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH)) has been treatedwith a combination of tamsulosin (TAM) + Serenoa repens(SR) (TAM + SR). The aim of this study was to compare acombination TAM + SR with TAM and SR alone, to see ifthere was any difference in efficacy and tolerance of each inpatients with LUTS/BPH. Methods. In this prospectivestudy patients had to have prostate volume (PV) < 50 mL,International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) of 7–18,Quality of Life score (QoLs) > 3, a maximal flow rate(Qmax) of 5–15 mL/s, with post voiding residual volume(PVR) < 150 mL and serum prostatic antigen (PSA) < 4ng/mL. TAM (0.4 mg) was administered once a day, SR(320 mg) daily or SR (320 mg) + TAM (0.4 mg) daily for amedian period of 6 months. Results. A total of 297 patientswere recruited, whereas 265 patients were fully available: 87into the group TAM, 97 into the group SR and 81 into thegroup TAM + SR. There was no statistically significant dif-ference between the treatment groups in the sense ofdemographic and other baseline parameters. No differencewas found among the 3 treatment groups, neither in themajor endpoint of the study in the sense of a change be-tween baseline and final evaluation in total IPSS, obstructiveand irritative subscores, improvement of QoLs, increase inQmax, nor for the second endpoint including diminution ofPV, PSA and PVR. During the treatment period 20 (23%)of the patients managed with TAM and 17 (21%) with TAM+ SR had drug- treated with related adverse reactions. Noadverse effect was detected in the group SR. Conclusion.Treatment of BPH by both SR and TAM seems to be effi-cacious alone. None of them had superiority over anotherand, additionally, a combined therapy (TAM + SR) does notprovide extra benefits. Furthermore, SR is a well-toleratedagent that can be used alternatively in the treatment ofLUTS/BPH.

Key words:prosthatic hyperplasia; adrenergic alpha-antagonists;phytotherapy; treatment outcome.

Apstrakt

Uvod/Cilj. Uo eno je da veliki broj bolesnika sa simpto-mima od strane donjih partija urotrakta izazvanih benignomhiperplazijom prostate (SDPU/BHP) ima terapiju sa kom-binacijom tamsulosina (TAM) + Serenoa repens (SR) (TAM +SR). Ova studija imala je za cilj da uporedi kombinacijuTAM + SR sa samo TAM i SR, da bi se videlo da li postojirazlika izme u njih u pogledu efikasnosti i podnošljivostikod bolesnika sa SDPU/BHP. Metode. U ovoj prospektiv-noj studiji bolesnici su imali volumen prostate (VP) < 50mL, internacionalni prostata simptom skor (IPSS) 7–18,ocenu kvaliteta života (KŽ) > 3, maksimalni protok urina(MPU) 5–15 mL/s, sa volumenom rezidualnog urina (RU)< 150 mL i prostata specifi nim antigenom (PSA) < 4ng/mL. TAM (0,4 mg) je bio primenjivan jedan put dnevno,SR u dozi od 320 mg dnevno, a kombinacija SR (320 mg) +TAM (0,4 mg) dnevno za prose ni period od 6 meseci. Re-zultati. Ukupno 297 bolesnika bilo je uklju eno u studiju, stim da je 265 bolesnika bilo dostupno potpunoj proceni: 87u TAM grupi, 97 u SR grupi i 81 u TAM + SR grupi. Nijebilo statisti ki zna ajne razlike izme u grupa u pogledu de-mografskih i drugih parametara pri po etnoj proceni. Tako-

e, nije bilo razlike izme u tri grupe, kako u pogledu pri-marnog cilja studije, promene izme u po etne i završneocene ukupnog IPSS, opstruktivnom i nadražuju em sup-skoru, poboljšanju KŽ, pove anju MPU, kao ni u pogledusekundarnog cilja studije uklju uju i smanjenje VP, PSA iRU. Tokom le enja, 20 (23%) bolesnika le enih TAM i 17(21%) bolesnika na kombinaicji TAM + SR imali su neže-ljene reakcije. Nije bilo neželjenih sporednih efekata u grupiSR. Zaklju ak. Le enje BPH sa SR i TAM je podjednakoefikasno. Ni jedan od tretmana nema superiornost u odnosuna drugi i dodatno, kombinovana terapija (TAM + SR) nedoprinosi dodatnom poboljšanju efikasnosti. Štaviše, izgledada je SR dobro podnošljiv fitopreparat koji se može alterna-tivno primeniti u le enju SDPU/BHP.

Klju ne re i:prostata, hipertrofija; alfa blokatori; fitoterapija;le enje, ishod.

Strana 1092 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Volumen 70, Broj 12

Argirovi A, Argirovi Dj. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1091–1096.

Introduction

Low urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are frequently as-sociated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) caused bycellular hyperplasia of both glandular and stromal elements.With an aging population the number of men affected byBPH is likely to increase 1, 2. Symptoms severity appears tobe dependent, at least in part, on smooth muscle tone in theprostate and bladder neck ³. Since medical inhibitors, in-cluding alpha-blockers (ABs) 4, alpha-reductase inhibitors(5-ARIs) and phytotherapeutic agents offer an attractive al-ternative to surgery, the number of transurethral resections ofthe prostate has declined in recent years 5, 6. However, thetolerability of these agents varies. Some ABs are associatedwith cardiovascular adverse events (AEs) (postural hypoten-sion, dizziness, and headache) and 5-ARIs can lead to sexualdysfunction 7. Conversely, a drug with high affinity for al-pha 1A-adrenoreceptors (tamsulosin) (TAM) may be moreprostate specific and may maintain the therapeutic responsein the treatment of symptomatic BPH with less effect onblood pressure and fewer cardiovascular AEs 8. In selectedpatients, a combination of AB and 5-ARI is the most effec-tive form of BPH medical therapy to reduce the risk of clini-cal progression, i.e. acute urinary retention (AUR) and BPH-related surgery 9. On the other hand, increasing attention hasbeen focused on the use of phytotherapeutic agents to allevi-ate the symptoms of BPH. The most described and studiedphytotherapeutic agent for the medical treatment of BPH isetahnolic extract of Serenoa repens (SR) (Sabal serrulata)derived from the berry of the American dwarf palm tree 10–12.The antiandrogenic, antiproliferative and anti-inflammatorycomplementary activities of SR extracts could constitute anadvantage over ABs to treated symptomatic BPH where both“obstruction” and “irritation” are involved.

The aim of this prospective pilot study was to test thehypothesis that the efficacy of combination TAM + SR is su-perior to TAM and SR alone for the relief of LUTS/BPH.The main endpoints of the study were changes in the totalInternational Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), Quality of alife score (QoLs), maximal flow rate (Qmax) and post void-ing residual volume (PVR) from baseline to the last observa-tion carried forward. This was applied only in naive patientssuffering from LUTS/BPH without previous treatment withABs, 5-ARIs or phytotherapy.

Methods

Between June 2008 and September 2010, 297 men aged50–87 years, with symptomatic BPH were included in thestudy containing 3 regimens: TAM (Tamsol®) 0.4 mg daily(n = 98), SR (Prostamol uno®) and TAM 0.4 mg + SR 320mg daily (n = 92), to compare the efficacy of each of thesetreatment regimens. All the patients signed informed consentform before any treatment. Pre-treatment procedures con-sisted of collection of the medical history (including urologichistory), check of concomitant medications, physical exami-nation [including digital rectal examination (DRE)], routinelaboratory tests [urine analysis, urine culture, creatinine,

prostate specific antigen (PSA)], total IPSS, irritative and ob-structive subscores, QoLs, prostate volumen (PV), Qmaxand PVR. The study was specially designed for medicaltreatment of patients suffering from low risk of AUR andBPH-related surgery. Inclusion criteria were men > 50 yearsof age, a total IPSS of 7–18, QoLs >3, Qmax of 5–15 mL/s,with PVR < 150 mL, PV < 50 mL, measured by transrectalultrasound (TRUS) and serum PSA 1.5–4 ng/mL. TRUS-guided biopsies of the prostate were performed in patientswith PSA > 4 ng/mL, abnormal DRE, and/or suspiciousechogenicity on TRUS. The subjects with a significant blad-der outlet obstruction (BOO) were excluded a priori fromthe study (PVR > 200 mL, Qmax < 5 mL/s). Patients wereexcluded from the study if they had the history of bladderdisease likely to affect micturition, urethral stenosis, prostateand/or bladder cancer, bladder stone, previous pelvic radio-therapy, recurrent urinary retention, neurogenic lower uri-nary tract dysfunction, repeated infection of the urinary tract,chronic bacterial prostatitis, or any other disease that cancause urinary problems. Assessment visits were performedhead to head and were scheduled at randomization (day 0),and latter at months 3 and 6. PV and PSA were measured atselection and at endpoint, whereas the total IPSS, obstructiveand irritative subscore, Qols, Qmax and PVR were evaluatedat baseline and later every 3 months. Responders were de-fined on the basis of IPSS and Qmax by decrease of > 25%and increase of > 30% from baseline, respectively. The pa-tients without subjective and objective improvement wererejected from the study within 3 months from the initiation ofthe treatment, after both patients and physicians had agreedabout that.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparison of thegroups and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for analysis of thebaseline and a 6-month treatment parameters. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data processingwas done by SPSS package for Windows version 11.0.

Results

A total of 87, 97 and 81 patients were fully availableregarding the treatment regimen, according to TAM, SRand TAM + SR, respectively. The main reason for studydiscontinuation was voluntary withdrawal (1.3%), protocolviolation (2.4%), lack of efficacy (3.03%) and other rea-sons (2.7%). Four (1.3%) patients were lost to follow-up(Table 1).

The treatment groups had comparable distribution interms of age, body mass index, a total IPSS, irritative andobstructive subscores, QoLs, Qmax, PVR, PV and PSA (Ta-ble 2). The mean age was 64.9 ± 7.6 years.

After 6 months of the treatment, the mean decrease inIPSS was -4.6, -6.1 and -4.9 in the TAM, SR and TAM + SRgroups respectively. The difference between IPSS values atbaseline and 6 months later were significant in each group (p< 0.05). The patients in the group SR had a greater reductionin symptoms than the other group. However, statisticalanalysis did not reveal this expected difference between thetreatment regimens (p = 0.1). This difference between the

Volumen 70, Broj 12 VOJNOSANITETSKI PREGLED Strana 1093

Argirovi A, Argirovi Dj. Vojnosanit Pregl 2013; 70(12): 1091–1096.

groups in the mean total IPSS decrease was not observed inthe irritative part -1.7, -1.8 and -1.9 (p = 0.6) and the obstruc-tive part -1.5, -1.4 and -1.3 (p = 0.5), for TAM, SR and TAM+ SR, respectively. For the QoLs, the group TAM had an ini-tial mean score of 3.5, which decreased for 2.1; the group SR4.2 which decreased to 2.6; the group TAM + SR had the ini-tial mean score of 3.5 which decreased for 2.2 after 6 months.The 3 groups had lower mean score after the treatment but thedifference was not significant (p = 0.1). Six months followingthe treatment, the mean increase in Qmax was similar in bothTAM and SR group (3.7 mL/s for TAM, 3.2 mL/s for SR), butwas slightly greater in the group TAM + SR (4.2 mL/s). The

patients in each group improved flow rates and the differencebetween the Qmax values at baseline and 6 months later wasstatistical significance in each group (p < 0.005), although thedifference was not statistically significant among groups withregard to increase in Qmax values (p = 0.3). The improvementof PVR volume was not statistically different among thegroups which decreased by 29.6, 28.1 and 25.4 mL, respec-tively (p = 0.4). Six months following the treatment the meanPV had decreased by 1.0, 0.7 and 0.8 mL, respectively. Thedifference was not significant (p = 0.6). The decrease in PSAwas more pronounced in the groups SR, but the difference wasnot statistically significant (p = 0.25) (Table 3).

Table 3Mean changes and ameliration rate in efficacy parameters from baseline to endpoint of the study

Parameters TAM (n = 87) SR (n = 97) TAM + SR (n = 81) pIPSS total score, ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

- 4.6 ± 3.3,(28.4)

- 6.1 ± 2.7,(33.9)

- 4.9 ± 2.3,(31.4) 0.1

IPSS obstructive subscore, ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

-1.5 ± 2.4,(16.7)

-1.4 ± 3.1,(13.8)

-1.3 ± 2.8,(15.1) 0.5

IPSS irritative subscore, ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

-1.7 ± 2.8,(26.6)

-1.8 ± 0.9,(26.9)

-1.9 ± 9.4,(28.8) 0.6

QoL score, ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

- 2.1 ± 0.8,(60)

-2.6 ± 0.9,(61.9)

- 2.2 ± 1.0,(62.9) 0.1

Qmax (mL/s), ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

+3.7 ± 2.6,(35.2)

+3.2 ± 2.2,(34.1)

+4.2 ± 2.5,(42.4) 0.3

PVR (mL), ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

- 23.6 ±20.2,(36.0)

-28.1 ± 22.6,(41.7)

-25.4 ± 14.8,(39.9) 0.4

PV (mL), ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

- 1.0 ± 0.6,(2.6)

-0.7 ± 0.1,(2.0)

- 0.8 ± 0.3,(2.6) 0.6

PSA (ng/mL), ± SD[amelioration rate (%)]

- 0.1 ± 0.2,(4.8)

-0.3 ± 1.4,(15)

- 0.25 ± 0.2,(14.7) 0.25

SD – standard deviation, TAM – tamsulosin; SR – Serenoa repens; IPPS – International Prostate Symptom Score; QoL – Quality of life; Qmax – maximal flowrate; PVR – post-voiding residual volume; PV – prostate volume; PSA – prostate specific antigen.

Table 1Reasons for premature discontinuation per the treatment group

Variable TAM (n = 98)n (%)

SR (n = 107)n (%)

TAM + SR (n = 92)n (%)

Completed study treatments 87 (88.8) 97 (80.7) 81 (88.0)Discontinued study treatment 11 (11.2) 10 (9.3) 11 (12)Lost to follow-up 1 (1.02) 1 (0.9) 2 (2.2)Discontinued due to: