1973 Excavations at the Upper Nodena Site

-

Upload

georgiasouthern -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of 1973 Excavations at the Upper Nodena Site

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

Robert C. Mainfort, Jr., J. Matthew Compton,and Kathleen H. Cande

The only modern excavalions ai the Upper Nodena site wereconducted during the summer of 1973. Excavations in anarea designated Block B exposed the remains of tzuosuperimposed houses representing initial construction andrebuilding of an open-corner ivall-trench structure. In BlockC, a remarkable concentration of charred maize was found.The most notexoorthy aspect of the faunal assemblage is thestrong representation of birds, especially passenger pigeonand waterfoxol. Five radiometric dates place occupation in themid-fifteenth century A.D.

Introduction

The type site of the Late Mississippi period Nodenaphase construct. Upper Nodena (3MS4) is locatedabout 8 km northeast of Wilson in Mississippi County,Arkansas, along a relict levee or point bar of theMississippi River known as Congress Ridge (Figure 1).About 400 rn to the east is a slough representinga former channel of the river that was active throughmuch of the nineteenth century. To the west wasYoung's Lake, a fairly large but shallow body of waterthat was drained around 1900 (Mainfort [editor] 2003).

The smaller Middle Nodena site (3MS3), locatedapproximately 2 km to the south on the same ridge, isthought to postdate Upper Nodena (Morse 1990:77; cf.Williams 1980). Both sites are located on property stillknown as the Nodena plantation, which was owned formany years by the family of physician and avocationalarchaeologist Dr. James K. Hampson (Morse 1989;Williams 1957), and are included within a NationalHistoric Landmark.

Nodena plantation is located within the St. FrancisBasin in the northern portion of the lower MississippiAlluvial Valley, a region also commonly known as thecentral Mississippi Valley (Griffin 1952; Morse andMorse 1983). Frequent overbank flooding resulted inthe deposition of nutrient-rich soils, making ecosys-tems in this region some of the most productive inNorth America (Fisk 1947; Harper et al. 1995). Of thesoils present in Mississippi County, Arkansas, those atUpper Nodena are among those best for modernagriculture (Ferguson and Gray 1971).

Upper Nodena encompasses approximately 6.3 ha(15.5 acres), with a well-defined periphery, but al-though the site may have been enclosed within a ditchor palisade (Morse 1989:101; 1990:73), the existence ofsuch features has not been confirmed archaeologicallyand remains problemahc, as discussed below. In 1897Dr. Hampson (1989:9) observed two rectangvilar sub-structural mounds (designated Mounds A and B) and"12 to 15" smaller mounds. Only the two largestmounds appear on a site map drawn by Hampson(upon which Figure 2 is based), but some of the smallerelevations were represented on a scale model of the siteconstructed by Hampson for use in his museum(Mainfort 2003; Morse 1989:98-99).

The largest mound. Mound A, measured approxi-mately 36.5 m by 34 m at the base and was 4.7 m tall,with the long axis oriented northeast-southwest.Hampson (1989:9-10) described the earthwork ashaving two levels, the upper supporting one building,and the lower having two (see Mainfort 2005a). MoundB was a smaller platform mound, about 1.2 meters inheight. Limited excavation by Hampson exposed theremains of what he interpreted as a circular structure(Hampson 1989:9-12; Mainfort 2005a). According toHampson (1989:9), the other smaller mounds varied insize from 0.45 to 1.2 m high, and 20 to 30 m indiameter. "Mound C" represents a large concentrationof burials southeast of Mound A that was excavated bythe Alabama Museum of Natural History. Hampson(1989:9) describes this locality as being about a meter inheight and perhaps 30 m in diameter, but the excava-tion records provide no basis for confirming orrejecting interpretation of this area as a constructedearthwork (Fisher-Carroll 2001a; Fisher-Carroll andMainfort 2000). None of the smaller possible moundsat Upper Nodena have been investigated archaeolog-ically. After nearly a century of intensive moderncultivation, most of the features described by Hampsonare no longer visible on the landscape (Morse 1989).

Previous Research

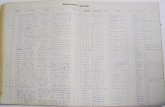

Dr. Hampson excavated at least 820 human burials,66 house sites, and 12 "kitchen middens" at UpperNodena (Hampson 1989:15; Mainfort 2005a). The bulkof his extensive collection was donated to the state ofArkansas and is curated at Hampson ArcheologicalMuseum State Park. Unfortunately, few of Hampson'snotes, maps, and burial cards have survived (Fisher-Carroll 2001a; Mainfort 2003, 2005a; Morse 1989).

IQ8

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

^y^.i^\

Upper NodenaMiddle Nodena

Richardson's LandingShawnee VillagePecan Point ^ *

Friend Mound* - /w /

Banks village

BradleyLoosahatchie

Chucalissakm

0 10Figure 1. Location of Upper Nodena and nearby late period sites.

20 30 40 50

109

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(1) SUMMER 2007

1932 gravel/dirt road

50J

possible site limits

limit ofHampson map

structures mappedby Dr. Hampson

1932 Arkansas excavations

1973 excavations

1932 Alabama excavations

paleoseismological trenchesa, B. N general areas shown on

Dr. Hampson's small maps

Figure 2. The Upper Nodena site, showing archaeoiogical features and areas excavated.

At Hampson's invitation, the University of ArkansasMuseum and the Alabama Museum of Natural Historyconducted excavations at Upper and Middle Nodena in1932. The Alabama crew excavated 616 human burialsat Upper Nodena and 183 at Middle Nodena, while theArkansas crew excavated 73 burials at Middle Nodena

and an additional 352 burials at Upper Nodena, thelatter all from areas south of the Alabama excavations(Figure 2). The focus of these excavations was theacquisition of mortuary ceramics for the two institu-tions. Neither institution produced reports on theirwork at Upper Nodena or other late period sites they

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

investigated in northeast Arkansas. The mortuary datafrom Upper Nodena have been analyzed by Fisher-Carroll (2001a; see also Fisher-Carroll and Mainfort2000), whose findings call into question traditionalinterpretations of Upper Nodena and roughly contem-porary sites in northeast Arkansas and southeastMissouri as representing the archaeological remainsof a hierarchically ranked society (Morse 1989, 1990).Mary Lucas Powell (1989,1990) reported on the curatedhuman remains from the 1932 excavations, as well asremains saved by Dr. Hampson. Tavaszi (2004)provides detailed descriptions and analysis of thewhole ceramic vessels that accompanied the burialsexcavated by the University of Arkansas Museum inthe early 1930s. Mainfort (2005a) discussed the struc-tures Hampson excavated at Upper Nodena.

The only modern professional excavations at UpperNodena are those conducted in 1973 by Dan Morse ofthe Arkansas Archeological Survey. That work formsthe subject matter of this paper.

Excavations

Based on the results of controlled surface collections,Morse selected three promising areas to test during the1973 field school (Figure 2). The excavation grid wasoriented to the approximate axis of the site rather thanmagnetic north. In discussing the locations of variousfeatures, direction refers to the excavators' grid, notcardinal directions.

In Block A, the northernmost area, participantsexcavated five 2-m squares, including three contiguousunits on the highest portion of a knoll. Artifactsassociated with a 193()s house were found to a depthof 33 cm below surface. In one unit, the remains ofa neonate were found beneath a large Mississippi Plainrim sherd. The only other unequivocal prehistoriccultural feature exposed in Block A was a post hole.

Block B was located about 50 m south of Block A(Figure 2) in an area with surface concentrations ofprehistoric artifacts and daub. Within an 86 m" block,over 155 features, including eight wall trenches withassociated post holes and four human burials wereexposed, as were two curvilinear soil discolorationslater identified as rodent burrows (Figure 3). Theaverage depth of the Block B excavations was about25 cm below surface.

The wall trenches represent the remains of twosuperimposed, roughly square houses with opencorners. The more northern (House 1) measured about5.7 meters square. House 2, just to the south, wassUghtly smaller at approximately 5.2 meters per side.The construction sequence is not clear, as wall trenchesfrom the two houses intersected only twice, and thesurviving intact deposits were very shallow. Post

function and association is evident only for thoseidentified within wall trenches. Function and associa-tion of the remaining posts is problematic, notwith-standing Morse's (1990:75) statement regarding thopresence of "roof support posts." The expected centralhearths were not located, probably due to disturbancesnear the approximate centers of both houses. The floorsof the houses were not preserved; hence, no artifactscan be associated confidently with the structures. Fewsamples of carbonized material were collected in BlockB, and none was unequivocally associated with one ofthe houses.

Several human burials were excavated in Block B.Burial 1 was located in the open northwest corner ofHouse 1. The remains are those of an adult lying ina supine, extended position, with the head to the north(grid) the torso and head rotated to the left; noassociated funerary objects were identified. Just insidethe southwest corner of House 2, the remains ofa neonate were found in a small circular pit andcovered by at least one-third of a Bell Plain bowl; aboutone-eighth of a small jar with arcaded handles waslocated under the bowl and with the neonate. Burial 3,a supine, extended, adult, with the head to the east(grid), was located in the northernmost extension ofBlock 3; no funerary objects were present. An extend-ed, supine adult with the head to the north (grid).Burial 4 was located in a pit just outside the south wallof House 2. Apparently this burial had been excavatedpreviously, perhaps by the Alabama Museum ofNatural History, which excavated a number of humanburials in the vicinity of Block B (Figure 2). Numerouslarge and small probe holes were observed, and "scoopmarks" were noted around the periphery of the burialpit; the latter accounts for the somewhat irregularoutline of the burial pit in Figure 3. A large gar bonewas located near the left femur, though it is unclear ifthe bone represents an intentional burial inclusion.

The superimposed open-corner wall-trench housesdocumented in Block B are of considerable importance,as there are very few published examples of lateprehistoric houses from the entire central MississippiValley. Perino (1966:20-26) reported several open-comer wall-trench houses at the Banks Village site.These may be of comparable age to the Block B housesat Upper Nodena, but neither the latter nor thestructures at Banks Village have been dated radiomet-rically. Several partial examples from Chucalissa(Figure 1) are illustrated and discussed by Lumb andMcNutt (1988:49-51).

Testing of Block C, located about 60 m southeast ofBlock B (Figure 2), consisted of a 50-cm-wide trenchthat extended from the edge of a county road to a point60 m northeast. The trench was excavated as a series ofcontiguous 1-m-long units designated, from southwestto northeast, unit C-1 through unit C-60, with a few

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(1) SUMMER 2007

351R338

342R338

Figure 3. Plan view of Block 8 excavation.

areas selected for more extensive testing. Since, withthe exception of the C-42 area, relatively little lateralexposure was accomplished, identified features lacka larger interpretive context, for example, demonstrableassociation with a structure.

Between C-3 and C-5, no prehistoric cultural featureswere recorded. Immediately to the north, in the areabetween C-5 and C-7, a few posts were found in theeastern portion of the block. Against the (grid) westwall, the remains of a young child (Burial 3C) weredisclosed beneath the end of a wall trench. This

? m

individual rested on the left side, with the head to thenorthwest and the legs slightly flexed; no funeraryobjects were present.

The area between C-7 and C-9 was widened to 3 m,with a small extension to the south, to completelyexpose two superimposed clay-lined hearths. Thesehearths probably are associated with a house orcorporate building that had been rebuilt, but neitherthe scattered post holes in the northern portion of theblock, nor those recorded in the adjacent 2-m block (C-9to C-11), are interpretable as structural rem.ains. The

122

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

C42N4

Grid Mag.

North

F-8A

C42N0 Disturbed C46N0Figure 4. Plan view of C-42 block excavation. See Figure 2 forgeneral location.

remains of an infant (Burial 2) were found withina small pit. This individual was buried on the left sideand may have been partially flexed; no funerary objectswere observed.

In the series of 2 m squares from C-11 to C-21, theonly identifiable prehistoric cultural features were postholes. No obvious alignments of posts suggestive ofstructure walls are discemable. In the northwest cornerof C-15, a small concentration of charred maize wasfound at a depth of 50 cm bs.

Between C-22 and C-42, the initial 50-cm trench wasnot widened, with the exception of the area between C-29 and C-31, which was expanded to a meter wide. Noprehistoric cultural features were recorded at the baseof the plow zone in the segment from C-22 to C-29. Tv 'opost holes and several concentrations of burned cornwere recorded at the top of subsoil between C-29 andC-31. A very dark "activity floor" (so designated in thefield records) encountered between 76 and 87 cm bs inthese units continued into C-32, 34, 36, and 37; animalbone and charred maize were common throughout.Other possible post holes were recorded at the top ofsubsoil between C-31 and C-42.

Based on the discovery of charred maize in the initialtrench, a 4-m-square block was excavated between C-42 and C-46, disclosing a number of features anda human burial (Figure 4). Of particular interest is theamount of maize (including 45 cobs) recovered fromthe C-42 block, much of it from Feature 8. Interpreta-tion of F-8 is compromised by a large animal burrow(F-8B) that was not recognized until much of thefeature had been excavated. Most of the maize,including many cobs with intact kernels, as well asa moderate amount of daub occurred within thisroughly circular area that encompassed the northernportion of the feature.

The presence of kernels on many maize cobs, the factthat the maize was burned, and the concentration ofdaub at this locality led Morse (1973:8; 1990:75) tosuggest the presence of an above-ground granary thathad burned. That the Soto chronicles, written perhapsno more than a century after the main occupation ofUpper Nodena, describe "houses raised up on fourposts, timbered like a loft and the floor of cane" (Elvas1993:75) makes this interpretation attractive. There are,however, several contravening factors to consider.First, other than daub fragments, no structural evi-dence attributable to such a storage facility was found.Second, the depositional contexts of the Feature 8maize and daub are unclear due to extensive distur-bance. Finally, it is uncertain that any of the maizeobserved by Soto and his men w as stored in raw form.As noted by Muller (1997:92), the Spaniards appro-priated parched maize from a granary on at least oneoccasion. Parched (shelled, dried, and cooked) maizereduces long-term storage problems such as fungalcontamination. Underground storage of maize asa long-term strategy probably would not have beensuccessful due to the growth of mold (Fisher-Carroll2001b:177-179).

Feature 4, located just to the east of F-8, was a largecircular, basin-shaped pit that contained considerableburned clay, as well as com cobs. It intruded intoa similar pit to the north that contained some maizeand was intruded into by a small pit to the south.Additional post holes were distributed throughout theexcavation block, but no wall trenches were identified(Figure 4). The remains of an extended, supine adult(Burial 1) were exposed within a pit in the eastern halfof the C-42 block. Over 100 closely spaced probe holeswere observed in the fill covering the interred in-dividual.

Beyond C-46, the initial 50-cm trench continued to C-60. Only a few possible post holes were recorded. Atthe presumed edge of the site (the final 4 m), noevidence of a ditch or palisade was found.

Radiometric Dating

Although Upper Nodena is one of the best-know^nsites in the lower Mississippi Valley, only a singleradiocarbon assay on a sample with uncertain pro-venience had been obtained for the site until quiterecently. A specimen of willow (SaJix sp.) collected byDr. Hampson returned a conventional radiocarbon ageof 630 ± 125 bp, which calibrates to A.D. 1161 (1304,1367, 1385) 1488 at 2 sigma.

Five samples of maize (four cob fragments and onekernel) from the 1973 excavations, all from Block C,were selected for AMS dating. The samples weregraciously provided by the Illinois State Museum,

113

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(1) SUMMER 2007

Table 1. AMS Determinations on Samples from the 1973 Excavations at Upper Nodena.

Lab Number

Bet.i-179108Beta-179109Beta-179110Beta-J79UlBeta--I79112

AveragesFeature 8 avt'rageC29-31.5 averageBlock C averageAll 1973 samples

Note: Calibrations performed

Sample ID

-73-432-12373-432-n 873-432-13973-432-139

Provenience

C29-31C31.5-31F-8A (kernel)F-8BF-8B

using CALIB 4.3 (Stuiver <ind Keimer

Radiocarbon Age

420490370460440

1W3).

± 4 0± 40± 4 0± 4 0± 4 0

Calibrated Date (1 sigma)

A.D. 1438 (1448) 1482A.D. 1411 (1430) 1441A.D. 1452(1486) 1627A.D. 1424 (1439) 1449A.D- 1433 (1443) 1471

A.D- 1440(1447) 1475A.D. 1431 (1440) 1448A-D. 1439 (1443) 1451

Calibrated Date (2 sigma)

A-D- 1423(1448) 1622A.D. 1333(1430) 1454A.D. 1439(1486) 1640A-D- 1407 (1439) 1484A.D. 1414 (1443) 1609

A.D. 1433 (1447) 1488• A-D. 1416 (1440) 1478

A.D. 1432 (1443) 1478A.D. 1432(1443) 1478

which curates the Blake-Cutler botanical collection.Summary data are provided in Table 1. The calibrateddates associated with AMS determinations are quiteuniform, and there are no significant statistical differ-ences between dates. Two assays were obtained on cobfragments from the "burned activity zone" in C29-C31.5. At 2 sigma, the calibrated average date of theseis A.D. 1416 (1440) 1478. Two cob fragments anda maize kernel from Feature 8 (C-42) produced anaverage calibrated date of A.D. 1433 (1447) 1488.

Combining all of the dated 1973 samples results ina calibrated date of A.D. 1432 (1443) 1478, with a 1.00probability that the actual date falls within that range.The range is comparable to that of calibrated datesfrom the Richardson's Landing and Graves Lake sites,located across the Mississippi River from UpperNodena in western Tennessee, and most of thepublished dates from Chucalissa (Mainfort 1996, 2001;Mainfort and Moore 1998).

Tuttle et al. (2000:24-29) report five AMS dates oncharcoal obtained during paleoseismological investiga-tions at Upper Nodena (Table 2). The study waslimited to several backhoe trenches situated roughly50 to 100 m east of the southwest end of the 1973 BlockC excavations (Figure 2).

Four samples were from contexts that predate a sandblow that was a focus of the investigation. The pre-sandblow assays (Beta 133012, -013, -015, and -016) do notdiffer significantly at the .05 level, allowing them to beaveraged to produce a radiocarbon age of 324 ± 20 bpor cal. A.D. 1438 (1524,1562,1629) 1641 at 2 sigma, with.809 of the relative area between A.D. 1490-1601.Pushing the limits of inference, the calibrated averageis consistent with an actual age in the mid 1500s.

Assuming that the material dated reflects culturalactivity, this may provide a terminus post quern for theUpper Nodena site. The burial urn excavated by Dr.Hampson, the catlinite disk pipe and fragment ofanother (Morse 1990:74; Morse and Morse 1983:287),and the end scrapers reported here all suggest post-A.D. 1500 activity (Mainfort 1996, 2001).

Thus the calibrated dates from Block C might beviewed as reflecting the traditional prehistoric "No-dena phase," while the four pre-sand blow datesreported by Tuttle et al. (2000) may represent evidenceof protohistoric Armorel horizon occupation. It must bestressed that at present only a very small portion of theUpper Nodena site has dated reliably. Neither of thesubstructural mounds at the site have been dated (andhave been virtually obliterated from the landscape),and while it is reasonable to infer that the vast majorityof human burials at the site date to the general timerange represented by the Block C assays, the relativeages of the burials and domestic occupation at the siteis by no means certain.

Faunal Material

The faunal material collected during the 1973excavations represents the first and only attempt tosystematically recover animal remains from UpperNodena (see Fisher-Carroll 2001a and Morse 1989), andhence provides the best opportunity for the interpre-tation of animal use practices by the inhabitants of thesite. I

Animal remains were recovered from all threeexcavation areas (Figure 2). A variety of screen sizes.

Table 2. AMS Determinations on Samples Collected During Paleoseismological Testing at Upper Nodena (Tuttle t>t al. 2000).

Calibrated Date (2 sigma)Lab Number

Beta-133012Beta-i330I3Beta-133014Beta-133015Beta-133016

TrenchTrenchTrenchTrenchTrench

Provenience

1, 1 cm below sand blow1, 45 cm below sand blow2, root cast into sand blow2, 9 cm below sand blow2, 3 cm below sand blow

Radiocarbon Age

290 ± 50280 ± 50230 ± 50350 ± 40340 ± 30

Calibrated Date (1

A.D. 1519(1640) 1656A.D- 1522(1642) 1659A.D. 1642 (1649) 1946A D . 1475 (t516, 1-599,A.D. 1484 (1519. 1594,

sigma)

1616) 16351622) 1635

A.D. 1473 (1640) 1945A.D. 1479 (1642) 1946A.D. 1522 (16.'i9) 1948A.D. 1444 (1516, 1599, 1616) 1645A.D. 1458 (ISl^J, 1594. 1622) 1642

Note: Calibrations performed using CALIB 4.3 (Stuiver and Reimer 1993).

lU

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

including 1/4 (6.35 mm), 1/8 (3.18 mm), and 1/16 inch(1.59 mm), was used to recover faunal specimens.Unfortunately, the screen size used for each pro-venience is not known, but the higher percentage ofsmall specimens recovered from Block C suggests 3.18-mm and/or 1.59-mm screens were used in this blockmore consistently than in Blocks A and B. This type ofrecovery strategy seems likely considering the highnumber of features and greater density of plant andanimal remains encountered in Block C. Moreover, theBlock C faunal collection is substantially larger thanthose from the other two excavation areas. Given theseconsiderations, only the faunal remains from Block Care presented here. A comprehensive report includingthe entire Upper Nodena faunal assemblage willappear in a forthcoming monograph (see Mainfort[editor] 2003), in which the Block C >2.00 mmcombined collection is equivalent to the Block Cmaterials presented here.

The relative abundance of different taxa is presentedin terms of number of identified specimens (NISP),minimum number of individuals (MM), specimenweight, and biomass. Biomass estimates are used topredict the dietary contribution of different taxa andare calculated using specimen weight and allometricformulae following Reitz et al. (1987) and Reitz andWing (1999:72, 224-231). Allometric formulae for bio-mass estimates are not currently available for theamphibians, so biomass was not estimated for mem-bers of this group. Invertebrates identified in the BlockC collection (freshwater mussels, Unionoida; cray-fishes, Cambaridae) are excluded from the data tablesbecause invertebrate remains were not systematicallyrecovered.

Because 3.18-mm and 1.59-mm screens were used tocollect the Block C faunal materials, many small,fragmentary specimens are present in the collection.In order to reduce the number of these largelyunidentifiable specimens, materials were passedthrough a 2.00-mm geologic screen in the laboratory.Previous experiments indicate that a 2.00-mm screenwill recover nearly all vertebrate remains identifiablebeyond taxonomic class (Colley 1990; Payne 1972).Examination of the Block C materials that passedthrough the 2.00-mm screen confirmed the assumptionthat very few specimens identifiable beyond class passthrough the 2.00-mm screen. Table 3 presents onlythose animal remains that did not pass through the2.00-mm screen.

The Block C collection includes 8,292 specimensweighing 3,209.33 g (Table 3). A minimum of 247individuals is represented among the 56 identifiedtaxa. The Block C collection is only a subset of theanalyzed Upper Nodena faunal assemblage, and theentire assemblage (Blocks A, B, and C) represents onlya small portion of the Upper Nodena site. Nonetheless,

this collection provides important insights into faunalexploitation by the inhabitants of Upper Nodena.

The inhabitants of Upper Nodena used a widevariety of aquatic and terrestrial taxa. Chief amongthese was the white-tailed deer, which supplied themajority of the meat consumed, as well as skins, bones,and other tissues used for raw materials.

Because white-tailed deer mandibles can be aged towithin a few months for individuals less than two yearsold, age data can be used to estimate the season ofdeath (Severinghaus 1949; Smith 1975:38). Mandiblesfrom the Block C collection indicate that deer werehunted from the late fall to spring. Behavioralcharacteristics of white-tailed deer make the fall andwinter particularly productive for deer hunting. Theperiod correlates with the white-tailed deer's breedingseason known as the rut. During the rut male white-tailed deer are vulnerable as they are less wary and canbe attracted using a variety of techniques including thehistorically documented use of decoys (Swanton1946:313-317). The white-tailed deer's preference foracorns during fall and winter also aids hunters byconcentrating deer in upland hardwood forest areas(Smith 1975:19). Bruce Smith (1975:39) identifies this"acorn-rutting" period of the late fall and winter as theprimary time of year for deer hunting by Mississippiangroups living in the central Mississippi Valley. Hesuggests this period may have extended into the latewinter or early spring in the Eastern Lowlands portionof the valley, as white-tailed deer were concentrated inthe uplands during the winter flood stage of theMississippi River. This hypothesis is largely based onmandibular age data from the Banks Village sitelocated in the Eastern Lowlands. Like Upper Nodena,data from Banks Village indicate deer hunting tookplace during the late fall and winter and continued intothe spring.

The cultivation cycle also likely played a role in thehunting of deer from late fall to spring. As croppingactivities drew to a close in the autumn, more timecould be spent pursuing deer and preparing theirhides. Hunting deer in the late winter or spring may berelated to a more concentrated effort to procure venisonas stored maize supplies dwindled and wild plantfoods were not yet available. Although venison is nota nutritional replacement for maize or other plantfoods, it was certainly a welcome supplement todiminishing food stores. An additional practical con-sideration for conducting deer hunting during the latefall, winter, and early spring is the lower temperature,which delays meat spoilage.

Although white-tailed deer supplied the greatestamount of meat, other mammals, birds, and fishes wereall important components of the diet. Aquatic taxa,particularly waterfowl and fish, were especially im-portant. These were available from the shallow lake

115

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(1) SUMMER 2007

Table 3. Upper Nodena, Block C, Species List.

Tax on

Amia calva (bowftn)Enmyzon sp. (chubsucker)kiiobus spp. (buffalo)Catostomldae (suckers)Ameiuruf, spp. {bullhead catfish)klalurus spp. (forktailed catfish)khihiTus ci. punctatus (probable channel catfish)Ictaluridae (freshwater calfishes)Moroiii' spp. (temperate bass)Centrarchidae (sunfishes)Ambloplites sp. (rock bass)Leponiis spp. (sunfish)Micropterus spp. (black bass)Pomoxis spp. (crappie)Aploiiiuahis ^p-iinniens (freshwater drum)LepisDsteidae (gars)Osteichthyes (indeterminate bony fish)Bufa spp. (toad)Rana ailesbeiaiia (bullfrog)Anura (frogs and toads)Cheli/dra scrpeiitim (comming snapping turtle)Chelydridae (snapping turtles)Kiiiostenion subrubrum (common mud turtle)Sternotberiii; otioratus (common musk turtle)Kinosternidae (mud and musk turtles)Tcrraperw Carolina (eastern box turtle)Trachcmys scripta (common slider)Apnione spp. (softshell turtle)Emydidae (box and water turtles)Testudines (indeterminate turtle)Cf. Nerodia sp. (probable water snake)Colubridae (nonpoisonous snakes)Crotalinae (pit \'ipers)Serpentes (indeterminate snake)Phnlacrocorax nurilii^ (dtiuble-crested cormorant)Arden /JITOI/JUS (great blue heron)Cygmis sp. (.swan)Anserinae (geese)Anas sp. (dabbling duck)Aythyinae (diving ducks)Anatidae (swans, geese, and ducks)Podicipedidae (grebes)Aqiiila chrysaelos/Haliaivfiis leiicacqjhalus (golden/bald eagle)Biileo spp. (hawk)Cf. Faico sp. (probable falcon)Cf. Fako pcrc^rinwi (probable peregrine falcnn)Colimis virghiianus (northern bobwhite)Meleagris gallopniK) (wild tvirkey)Grus canadmsis (sandhill crane)Scoiopacidae (sandpipers)Eclopistes migratorius (passenger pigeon)Colapfes auratiis (northern flicker)Corvus brachyrht/nclios (American crow)Cf. Quiscahis qiii^cuia (probable common gr.ickle)Picidae (woodpeckers)I'asseriformes (perching birds)Aves (indeterminate bird)Didelphis virginiarm (Virginia opossum)Syh-ilagus spp. (rabbit)Syh'tlagus cf. atjuaticus (probable swamp rabbit)Sylviltigii^ cL floridanus (probable eastern cottontail)Sciuruf spp. (tree squirrel)Sciurus cf. nigiT (probable eastern fox squirrel)Caslor caimdeiisis (beaver)Micro(H.-! spp. (vole)Ondatra zibethkiis (muskrat)On/zomys palustris (rice rat)Ochrotomys nut tall i/Peromyscus spp. (mouse)Sigmodontinae (New World nnice and rats)Rodentia (rodents)Catiis spp. (coyote, wolf, or dog)Canidae (dogs, wolves, coyotes, and foxes)Utsus ainerkanui (black bear)Pracyon iotor (raccoon)Mustek vison (mink)Cf. Puma concolor (probable mountain lion)Lynx rufiis (bobcat)Mustelidae (weasels, skunks, and others)

NISI'

2151

3568H81

212. i89i

ifu7* .

10nm

547

1132^« •

11043

169121712i

m-II

2?7.ai •

114

3-2

15^2

1131

12^ 0

224S

17?

161

314

17039

7391

U6S

40111

12

MNI No-

814-

(12)(2)(1)26115(1)<2)(2)(2)15-22-

0)211-

(1)(1)24-1-1-11

(1)(3)(1)(1)211112

(1)

t1191

m7-

- . i

mmmtI3

(55)(10)88-

m.•'3• 1

5(1)112

"'"

320.41.6----

1050.46.1----0.42.0---.

0.80.40.4---0.81.6-0.4-0.4-0.40.4----8.50.40.40.40.8-0.40.40.40.43.60.4---

.

• • » !

-

0 41.2--

35.6--1.20.42.0-0.40.40.8

Weight (grams)

28.340.083.68

•ft5SfM2.890.78

22.080,198.660.090.891.970.552.07

23.2160.200.8 -0.80.146.429.970.830332.286.431.218.65

43.2123,580,050.430.091.070231.572.87

38.800.160.44

119.780.722.850.280.320.80{I..10 •

16.8614,900.18

21.860,224.010.480.010.60

92.520.32

84.8626.51

1,512.850.274.280,10

10.6411.73

1.1550.81

0.0417.14

1.5121.9242.66

0.140.300,504,04

Biiim.iss (grams)

249,824.11

84.53182.07131.8754,6815.76

377,396.94

106,532.30

15.7630.7110.52 '66,66

510.68815.56

0.201.09-

109.92147,6227.9115.05

. 54.93110,0335.93

134.22394.32262,79

0.675.891.21

14.785.36

30,78 153.29

569.963.859.67

1589.78 '15.1452.96641

•7a«16.67 '

6.83266.96238.57

4.29338.14

5.1572.2610.470.31

12.831256.85

9,43i431,68502,44

38.1167.51

8.1097.34

3.31220.93241.20

29.83902.34

1.45339,33

38,11423.42770.96

4.488.90

14.10< 2.42

316

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

Table 3. Continued

Taxon

Camivora (carnivores)Oiiociiileus virginiantis {white-tailed deer)Cervidae (dwr)Mammalia (indeterminate mammal)Vertebrata (indeterminate vertebrate)

Total

NISP

1214

413652077

MNI No,

5--

.

2.0

-

Weight (grams)

0.081485.27

6.15711.10124.01

Biomass (grams)

2.7118820,85

134.909699.56

-

247

Note: In cases in which a higher MNI is estimated at a higher taxonomic level, the MNI estimates of lower taxonomic levels are in parentheses. The total MNI ot 247does not include MNI estimates in parentheses. Biomass is estimated based on allomefric relationships (Reitz et al. 1987; Reitz and Wing 1999:227-228). Allometricformulae are not currently available for the amphibians, so biomass is not estimated for members of this group.

immediately west of Upper Nodena. Indeed, thelocation of the site probably was chosen in part to takeadvantage of the aquatic animals available in andaround the lake. The abundance of quiet-water fishtaxa in the collection including gar, bowfin, chub-sucker, and bullhead catfish suggests that the inhabi-tants of Upper Nodena acquired fishes from theadjacent backwater areas rather than traveling to anactive stream charuiel (Robison and Buchanan 1988:89-94,99, 267-269, 292-296). Backwater areas support highfish biomass levels that are annually replenished byfloods. Limp and Reidhead (1979) argue that aboriginalfishing techniques were more productive in suchbackwater areas than in the major river channels. Theysuggest that as water levels in oxbow lakes, bayous,and other backwater areas dropped during the summerfish became more concentrated and thus easier toacquire using relatively simple techniques and minimaleffort. Turtles and aquatic amphibians also occur inbackwater areas, though the lower abundance of thesetwo groups suggests they were not as intensivelytargeted Qohnson 1987; Trauth et al. 2004).

Of the 18 bird taxa identified in the Block Ccollection, nine are aquatic species. The shallow lakesand bayous of the central Mississippi Valley are idealfor a variety of waterfowl and wading birds (Baldas-sarre and Bolen 1994:397; James and Neal 1986:35-37).The abundance of avian fauna in the central MississippiValley is also attributable to its location within theMississippi Flyway. The Flyway is a major avianmigratory route that funnels migratory waterfowl frommuch of the northern half of North America to thewintering grounds of the central and lower MississippiValleys (Baldassarre and Bolen 1994:282; Smith1975:64-65). The seasonal abundance of migratorywaterfowl occurs from mid-October to mid-April, withpeaks in abundance during the fall and springmigrations (Smith 1975:122).

In addition to the large numbers of aquatic birds thatuse the central Mississippi Valley for wintering andmigration, several terrestrial species are also attractedto the region due to its mild winter climate. The mostabundant of these in the Bkx~k C collection is the now-extinct passenger pigeon. Historic records of passenger

pigeons in Arkansas indicate the birds wintered in thestate from October to April, often congregating in largeroosts at night (James and Neal 1986:198). Theabundance of migratory waterfowl and other migrato-ry hird species in the Block C collection indicates theinhabitants of Upper Nodena took advantage of theseseasonally abunclant resources.

Rabbits and raccoon are the dominant terrestrialspecies other than white-tailed deer in the Block Ccollection. These species are often encountered incultivated fields and may represent "garden hunting"at Upper Nodena (Schwartz and Schwartz 2001:297-298; Sealander and Heidt 1990:110-113, 214). Gardenhunting can be carried out while conducting cultivationactivities and has the secondary effect of reducingdepredation on crops (Linares 1976; Neusius 1996).Some aquatic mammals (beaver and muskrat) werealso a regular part of the diet, though less often thanrabbits and raccoon.

The inhabitants of Upper Nodena used largemammals other than white-tailed deer infrequently.Though present, black bear and mountain lion wereprobably only occasional sources of food. Notablyabsent from the collection are elk {Cenms elaphus) andAmerican bison {Bison bison). Elk and bison remainshave been recovered from Mississippian sites in theregion, but their infrequent occurrence indicates rela-tively low numbers of the species in the region duringthe Mississippian period or hunting forays out of theMississippi Valley.

The abundance of commensal taxa that prefergrassy/brushy habitats indicates significant landscapemodification by the inhabitants of Upper Nodena. Themost prominent group of commensals in the Block Ccollection is the subfamily Sigmodontinae, specificallyrice rat, and mice identified as either golden mouse ora mouse belonging to the genus PtTond/sci/.s. Rice ratsand mice prefer grassy/brushy environments andlikely were attracted to the disturbed habitats of theUpper Nodena village and its surrounding fields(Schwartz and Schwartz 2001:194-195, 202-212, 214-216; Sealander and Heidt 1990:148-149,157-166). Cropsin the field as well as stored foods and garbage in thevillage would have provided an ample source of food

117

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(2) SUMMER 2007

Table 4. Corn Cobs from Upper Nodena.

Provenience

8-rowed10-rowed12-rowed14-rowed

TotalMean Row No.

"Crib" Other Total

4 (9%)19 (42%)19 (42%)3 (7%)

4510.9

7(13%)22 (42%)18 (34%)6 (11%)

S310.9

n (11%)41 (42%)37 (38%)9 (9%)

9810.9

Note: Adapted from Blake and Cutler (1979:Table 1).

for rodents. The large number of rats and mice (MNJ =88) reflect a significant pest problem at Upper Nodenathat may have caused substantial depredation to cropsand stored foods, such as the possible granary in BlockC. The presence of several burned and calcinedSigmodontinae specimens indicates these rodents werecontemporaneous with the human occupation of UpperNodena and are not more recent intrusions.

Notably lacking in the faunal collection are examplesof prairie species, which would be expected in post-A.D. 1540 faunal assemblages from the region assum-ing extensive drought-induced prairie expansion (Fish-er-Carroll 2001b; Stahle et al. 1985; Stahle et al. 2000; seealso Scarry and Reitz 2005:117). Although severalspecies in the Block C collection are often found inopen grassland habitats (e.g., peregrine falcon andsandhill crane [Deselm and Murdock 1993]), none areexclusively prairie-adapted species like the greaterprairie chicken {Tympamichus aipido) (Deselm andMurdock 1993) and thirteen-lined ground squirrel{Spmnophilus tridecemlineatiis) (Sealander and Heidt1990:250).

Comparison of the Upper Nodena faunal collectionto other assemblages from the region suggests a generalpattern of animal use common to Mississippian groupsliving in the central Mississippi Valley. This pattern ofanimal exploitation involved a heavy reliance on white-tailed deer and the abundant aquatic resources of theMississippi meander belt zone. The use of aquaticresources is particularly prevalent among sites of theEastern Lowlands. Among the sites analyzed by Smith(1975), the Banks Village and Lilbourn sites mostclosely resemble the animal-use pattern observed atUpper Nodena. At all three of these sites, migratorywaterfowl were a major component of the diet.Waterfowl and other lnigratory birds were welcomedietary additions from October to April. Fish, especial-ly catfishes, gars, suckers, and bowfin, were alsoimportant to the animal-use strategy of groups livingin the Eastern Lowlands. Upper Nodena also providesevidence that Mississippian groups living in theEastern Lowlands hunted white-tailed deer into thelate winter and spring. The similarity among these sitesillustrates an adaptation to the unique environmentalhabitats of the Eastern Lowlands portion of the central

Table 5. Corn Cupule Width at Upper Nodena.

Cupule Width (mm) "Crib" Other Total

8.6+7.6-8,5 I6.6-7,5 :5.6-6.54.6-5.5<4.6

Median Cupule Width (mm)

207o13%27%29%9%2%

7.2

6%21%26%32%8%7%

6.8

12%17%27%31%8%5%

6.9

Note: Adapted from Blake and Cutler (I979:Table 1).

Mississippi Valley that was shared by Mississippiangroups inhabiting the region.

Botanical Material

The botanical remains from the 1973 excavation wereanalyzed and reported on by Blake and Cutler (1979).The discussion that follows is drawn from their article,but some interpretations offered here differ from thoseof Blake and Cutler.

Most of the botanical remains, including virtually allof the maize, were collected from Block C. A tota! of 98corn cobs was collected. Of these, 45 were associatedwith the possible com crib (Area C, F-8 and vicinity).Blake and Cutler (1979) structured their interpretationsbased on the presumed existence of such a structuralfeature; as discussed earlier, the presence of a com cribcannot be confirmed. As shown in Table 4, Blake andCutler (1979) identified most (807o) of the corn cobs as10- and 12-rowed, the remainder being 8- and 14-rowed. Comparable diversity in row number is evidentin the samples from the "corn crib" area and thosefrom the remainder of the excavated area. Blake andCutler (1979:53) report that the cupule size of cobs fromthe "corn crib" area is larger than that of cobs collectedfrom other excavated areas (Table 5). Data compiled byLeonard Blake (2003) includes cupule widths for 47cobs from the "corn crib" area and 48 cobs from otherareas. Using these data, the mean cupule width of cobsfrom the crib area is 7.2 mm, with a standard deviationof 1.72 mm; the mean cupule width of cobs from otherareas is 6.5 mm, with a standard deviation of 1.38 mm.The mean values are nearly identical to those reportedby Blake and Cutler (1979). For the total sample, themean cupule width is 6.8 mm, with a standard de-viation of 1.6 mm. These values, coupled with sam-pling issues, suggest that the differences between the"com crib" area and the other excavated areas reportedby Blake and Cutler may be overstated.

Blake and Cutler (1979) identified 10 whole or halfspecimens of cultivated beans [PhaseoUts vulgaris), butneither rinds nor rinds of squash and gourds werepresent in the material they examined. Hickory nut{Carya sp.) shells were present in 40 of the 85 samples

118

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

T.ible 6. Distribution of Ceramic Types by Excavation Area.

Bell PlainMississippi PlainBrtrton IncisedFortune NodedKent IncisedNodenii Red and WhiteOld Town RedP.irkin PunctatedRanch IncisedRhixii's IncisedVcmon Paul Appliqu^Walls EngravedUnidentified incisedUnidentified slippedNonshell tempered paste

Total

Area A

2,27fi642

31 (w/red)01

10 .44 (2 w/red)0002 (1 w/red)006

2,98.

Area B

1,115341

4000410001009

1.475

Area C

3,2W5^144

2061

1425764

324

1751

139

8,756

Total

6,6906,127

2771

1539

1214

324

20511

5413,216

Table 8. Comparisons of Rim Attribute Frequencies in SherdCollections versus Whole Vessels from Upper andMiddle Nodena.

of botanical remains; black walnut (Juglans nigra),pecan {Carya illinoensis), and hazelnut {Corylus sp.)were present in very small amounts. Persimmon{Diospyros virginiana) seeds were identified in 23samples. No native cultigens {e.g., Chenopoiiium) werefound (Blake and Cutler 1979).

Material Culture

The 1973 excavations produced a 13,216 potterysherds from the type site of the Nodena phase construct(Table 6). It is perhaps fitting that, in a normative sense,this excavated sample is archetypical of a Nodenaphase ceramic assemblage {senmi Phillips 1970:933-936). The frequency of Bell Plain exceeds that ofMississippi Plain, and the percentages of Barton Incisedand Parkin Punctated are very low (n = 148; 1.1%).This comment by no means constitutes an endorsementof the traditional Nodena phase construct, which hasbeen criticized in recent years (e.g., Mainfort 1999,2003a, 2003b, 2005b; O'Brien 1994, 1995).

Attribute data were collected from the 1,430 ceramicrims obtained during the 1973 project (see Mainfort2003a; Mainfort and Moore 1998). As shown in Table 7,there is considerable spatial variation in rim attributefrequencies between the three 1973 excavation areas.Interior beveling is present on only 1.5 percent of the339 rims collected in Block A versus 13.0 percentand 14.2 percent in Blocks B and C, respectively.The frequency of beaded applique strips ranges from

Table 7, Spatial Distribution of Ceramic Rim Attributes.

Block ABlock BBlock C

Total

N

339192899

1,430

InteriorBevel

5 (1.5%)25 (13.0*K>)

128 (14.2%)

Beaded AppliqudStrip

24 (7.1%)8 (4.2%)

120 (13.47o)

152(10.6%)

Exterior

31 (9.2%)11 (5.7%)79 (8.8%)

121 {8.5'1'1,)

Provenience

Upper Nodena shvrdsfl973)Upper Nodena sherdsUpper Nodena vesselsMiddle Nodena sherdsMiddle Nudt-na vessels

N

1.430

103186117120

InteriorBevel

11,1

28.257.047.063.3

Beaded Appliqu^Strip

10.6

25.221,4 .12.010.8

tixteriorNotching

&5'

' 26ti,fS

35.017.5

Note: Most data taken from Mainfort (2(>03a).

7.1 percent in Block A to 4.2 percent in Block B to 13.4percent in Block C. Spatial variation in the percentageof exterior notching is less pronounced, rangingbetween 5.7 percent and 9.2 percent.

It is noteworthy that the frequencies of beveled rims,beaded applique strips, and exterior notching in the1973 assemblage are markedly lower than thosereported by Mainfort (2003a) for the much smallersurface-collected sample of rims available for hisanalysis (Table 8). There are several factors to considerregarding the differences between these assemblages.First is the ever-present issue of sample representative-ness. The collections analyzed by Mainfort (2nO3a) weresurface finds obtained by Dan Morse during multiplevisits to Upper and Middle Nodena, but far more rimsherds from Upper Nodena were collected in 1973,immediately before and during the field school. Theprecise spatial coverage of Mainfort's (2003a) sample isunknown, but it probably involved more than thecorner of the site tested in 1973. In the earlier rimattribute study, Mainfort (2003a) considered 45 rims tobe the smallest sample suitable for use in analysis. The1973 data suggest that this figure is far too low.

There are also major disparities in the frequencies ofinterior beveling and beaded applique strips betweenthe University of Arkansas Museum whole vesselassemblage from Upper Nodena (Tavaszi 2004) andthe 1973 sherd collection. Whole vessels and sherdsclearly cannot produce strictly comparable data sets. Inthe present instance, all the whole vessels in questionwere funerary objects, while the original context of thesurface-collected and most excavated rim sherds isunknowable. The data in Table 8 raise the possibilitythat the high frequencies of interior beveling in thewhole vessel collections reflect a more recent age forthe sample of mortuary vessels, that is, the wholevessels excavated by the University of ArkansasMuseum largely postdate the rim sherd assemblages.Such a scenario ties in nicely with the discussion ofradiometric dating presented earlier, but it must beremembered that the Upper Nodena whole vesselassemblage used here for comparison is not large andwas obtained from only a small portion of the site.

US

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(1) SUMMER 2007

A total of 11,950 stone artifacts was recovered fromthe Upper Nodena site during the 1973 excavations.The vast majority of the assemblage consists of flakes (n= 8,023) and shatter (n = 3,222). Among the 516 toolsare 58 projectile points and preforms, four adzes, 47bifaces, a chisel, several drills, 18 hammerstones, a hoe,many pebble cores, 11 scrapers, four thumbnail orsnub-nosed end scrapers, and a range of modified flaketools. The chipped lithic assemblage consists mainly ofexpedient chert flake tools, most made from pebblegravels. There are very few ground stone tools, whichis surprising for a habitation site. A total of 7.4 kg ofunmodified stone material also was collected.

There are 41 arrow points and arrov^'-point fragmentsin the collection, including 17 Nodena (Chapman andAnderson 1955:15) and Nodena-like points and 10Madison points. All of the latter are fairly small, withnone approaching the size (or fine workmanship)characteristic of some seventeenth-century triangularpoints (Mainfort 1996, 2001). Two arrow points weremodified into "pipe drills" (Brain 1988:262, 398; Morseand Morse 1983:272-273). The 1973 collection alsoincludes 15 chert arrow-point preforms, two of whichrepresent preform stages of Nodena points.

The most important lithic artifacts obtained duringthe 1973 field season are four snub-nosed endscrapers.These are characterized by a tear-shaped outline,extremely steep retouch, and conical cross-section.Snub-nosed endscrapers are associated with post-A.D. 1540 contexts in the region, and numerousexamples have been found at late period sites innortheast Arkansas, southeast Missouri, western Ten-nessee, and farther south in the lower MississippiValley (Brain 1988; Mainfort 1996, 2001; Williams 1980).Identification of snub-nosed end scrapers in thecollection was surprising, as the absence of theseartifacts has been a key factor supporting the inferencethat Upper Nodena predates Middle Nodena (Mainfort2001:187; Morse 1990:77; cf. Williams 1980:105).

Concluding Remarks

The 1973 excavations at Upper Nodena sampled onlya small portion of a fairly large (6.3 ha) late Mississip-pian town, but not only are these the only modern eraexcavations at the well-known site, they also representone of the only modern excavations at any of thenumerous late period sites in northeast Arkansas(Mainfort 2001; Morse 1989; Morse and Morse 1983).

Though limited in extent, the 1973 fieldwork and theanalyses summarized herein produced significant newdata about late period cultural adaptations in thecentral Mississippi Valley. Excavations in Block Bexposed the remains of two superimposed housesrepresenting initial construction and rebuilding of an

open-corner wall-trench structure; there are very fewpublished examples of late prehistoric houses from theregion. In Block C, a remarkable concentration ofcharred maize was found, much of it in the C-42 blockexcavation. Many cobs retained at least some of theirkernels. Morse's suggestion that some of this materialrepresents an above-ground granary that burned(1973:8; 1990:75) could not be confirmed and, thoughwe have raised questions about this interpretation, thepossibility cannot be rejected. The apparent lack ofa ditch or palisade around the exterior of the town isinteresting and seems to be confirmed by the laterpaleoseismological testing (Figure 2) (Tuttle et al. 2000).

Five samples of maize from Block C were selected forAMS dating and produced an average age range of cal.A.D. 1432-1467 at 2 sigma. These are the first reliableradiometric dates for the type site of the Nodena phaseconstruct. Four AMS determinations on materialobtained during paleoseismological testing at UpperNodena (Tuttle et al. 2000) raise the possibility ofa protohistoric Armorel horizon occupation at the site.Note that several sites with Armorel occupations (e.g.,Campbell, from which European artifacts have beenrecovered) have been assigned to the traditionalNodena phase (Morse 1990:81-82; Phillips 1970:934).

Identification of snub-nosed end scrapers in the lithicassemblage was surprising and has important chrono-logical implications. These tools are considered the keydiagnostic of protohistoric (post-A.D. 1541) occupa-tions in the region (Mainfort 1996, 2001). No exampleshave been reported previously from Upper Nodena,leadiiig researchers to propose that Middle Nodena(from which end scrapers have been reported pre-viously) postdates Upper Nodena (Morse 1990:77;Williams 1980). It is now apparent that the temporalrelationship of Upper and Middle Nodena is not sostraightforward. Moreover, the end scrapers, coupledwith the burial urn and catlinite, from Upper Nt)denalend further credence to the radiocarbon assaysobtained during paleoseisinological investigations.Notably absent in the 1973 collections are largetriangular points (see Mainfort 1996, 2001).

Attribute data were collected from over 1,000ceramic rims obtained during the 1973 project. Thereis considerable spatial variation in rim attributefrequencies—especially interior beveling and beadedapplique strips—between the three excavation areas.Further, the frequencies of beveled rims, beadedapplique strips, and exterior notching in the 1973assemblage are markedly lower than those reported byMainfort (2003a) for the much smaller sample of rimsused for his analysis. Both of these findings callattention to the ever-present issue of adequate samples.Major disparities in the frequencies of interior bevelingand beaded applique strips between the University ofArkansas Museum whole vessel assemblage from

120

1973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

Upper Nodena and the 1973 sherd collection also weredocumented.

Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the faunalassemblage is the strong representation of birds, whichare the third most abundant group in terms of biomass.Especially prominent are passenger pigeon and water-fowl. Not surprisingly, the most abundant species interms of biomass is the white-tailed deer, which werehunted into the late winter and spring. Birds, however,account for the largest MNI. The remains of numerousrats and mice reflect a significant pest problem in thetown. True prairie species, some examples of whichmight be expected in post A.D. 1540 faunal assem-blages from the region (Fisher-Carroll 2001b; Scarryand Reitz 2005), are not present in the 1973 faunalassemblage from Upper Nodena.

A total of 98 maize cobs was collected during the1973 project, but other plant species are poorlyrepresented. Especially noteworthy in this regard isthe lack of native cultigens, the absence of which maybe attributable to limited use of flotation. The differencein cupule width between maize from the possible criband other deposits reported by Blake and Cutler (1979)is not great enough to warrant strong inference.

Over three decades ago, Phillips (1970:934) notedthat "we haven't even begun to understand thenuances of variation, particularly in the chronologicaldimension, of our insufficiently specific cultural unitssuch as Nodena." The data presented here represent anadniittedly small, but important, step toward addres-sing this situation.

Notes

AcknoTvlcdgments. During the summer of 1973, Dan Morse(Arkansas Archeological Survey, Arkansas State Universitystation) directed nine and a half weeks of fieidwork at theUpper Nodena site. From June 4 to July 13, excavations wereconducted as part of a joint University of Arkansas-ArkansasState University archaeoiogical field school. A small paidcrew and n number of volunteers accomplished additionalficldwork between July 16 and August 8.

Analysis of the field records and artifacts from the 1973excavations at Upper Nodena was made possible by a grantfrom the Arkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council tothe Arkansas Archeological Survey. Maria Tavaszi organizedthe artifact collections and created a collection database.

Leonard Blake prtKessed and analyzed the paleoetlinobota-nical material; he is greatly missed as a friend and colleagueby all who knew him. Michael Wiant, Terry Martin, and DeeAnn Watt of the Illinois State Museum located andgenerously provided the samples used for radiomt'tric dating.Greg Lucas, Elizabeth May, and Kelly Orr assisted with theanalysis of the faunal materials; Elizabeth Reitz providedguidance throughout the analysis. Charles McNutt offeredsome insightful comments regarding radiometric dating. Ed

Jackson and Terry Martin contributed useful commentary onan earlier draft of the paper.

References Cited

Baldassarre, Guy A., and Eric G. Bolen1994 Waterfowl Ecology and MafiagemeiU. John Wiley and

Sons, New York.Blake, Leonard W.2003 Inventory of the Paleoethnobotanical Material from the

1973 Excavations at Upper Nodena. In ArchaeologicalUwes^tigations <U Upper Noiiena: 1973 Field Seaso)i, edi ted by

R. C. Mainfort, Jr., pp. 96-106. Report submitted to theArkansas Natural and Cultural Resources Council, LittleRock.

Blake, Leonard W., and Hugh C. Cutler1979 Plant Remains from the Upper Nodena Site. Arkansas

Archeologist 20:53-58.Brain, Jeffrey P.1988 Tunica Archaeohg}/. Papers of the Peabody Museum of

American Archaeology and Ethnology 71. HarvardUniversity, Cambridge, MA.

Chapman, Carl H., and Leo O. Anderson1955 The Campbell Site: A Late Mississippian Town Site

and Cemetery in Southeast Missouri. Missouri Archaeolo-gist 17(2-3):10-119.

Colley, Sarah M.1990 The Analysis and Interpretation of Archaeological Fish

Remains, ln Archaeological Method ami Theory, vol. 2,edited by Michael B. Schiffer, pp. 207-253. University ofArizona Press, Tucson.

Deslem, Hal R., and Nora Murdock1993 Grass-Dominated Communities, in Biodiversity of the

Southeastem United States: Upland Terrestrial Communities,edited by W. H. Martin, S. G. Boyce, and A. C.Echternacht, pp. 87-14L John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Elvas, Gentleman from1993 The Account by a Gentleman from Elvas. In The De

Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to NorthAmerica in 7539-7543, edited hy L. A. Clayton, V. J.Knight, Jr., and E. C. Moore, pp. 19-219, University ofAlabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Ferguson, D. V., and I. L. Gray1971 Soil Stiniey of Mississippi County, Arkansas. GPO,

Washington, DC.Fisher-Carroll, Rita L.2001 a Mortiiari/ Behavior at Upper Nodena. Research Series 59.

Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville.2001b Environmental Dynamics of Drought and Its Impact

on Sixteenth Century Indigenous Populations in theCentral Mississippi Valley. Unpublished Ph.D. disserta-tion. Environmental Dynamics Program, University ofArkansas, Fayetteville.

Eisher-Carroll, Rita, and Robert C. Mainfort, Jr,2000 Late Prehistoric Mortuary Behavior at Upper Nodena.

Southeastern Arcliaeology 19:105-119.Fisk, Harold N.1947 Fine-grained Alluvial Deposits and Their Effects on

121

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGY 26(1) SUMMER 2007

Mississippi River Activity. Mississippi River CommissionPublication. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Vicksburg.

Griffin, James B.1952 Prehistoric Cultures of the Central Mississippi Valley.

In Archeology of Eastern United States, edited hy J. B.Griffin, pp. 226-238. University of Chicago Press, Chi-cago.

Hampson, James K.1989 The Nodena Site. In Nodena, edited by D. F. Morse,

pp. 9-15. Research Series 30. Arkansas ArcheologicalSurvey, Eayetteville.

Harper, David M., C. R. Smith, P. Barham, and R. Howell1995 Ecological Basis for Managing the Natural Environ-

ment. In The Ecological Basis for River Managefnent, editedby D. M. Harper and A. J. D. Ferguson, pp. 219-238. JohnWiley & Sons, Chichester.

James, Douglas A., and Joseph C. Neal1986 Arkansas Birds. University of Arkansas Press, Fayette-

ville.Johnson, Tom R.1987 The Amphibians and Reptiles of Missouri. Conservation

Commission of the State of Missouri, Jefferson City.Limp, Frederick W., and Van A. Reidhead1979 An Economic Evaluation of the Potential of Fish

Utilization in Riverine Environments. American Antiquity44(l):70-78.

Linares, Olga F.1976 "Garden Hunting" in the American Tropics. Human

Ecology 4(4):331-349.Lumb, Lisa C, and Charles H. McNutt1988 Chucalissa: Excavations in Units 2 and 6, 1959-67.

Occasional Papers 15. Memphis State University, Anthro-pological Research Center. Memphis, TN.

Mainfort, Robert C, Jr.1996 Late Period Chronology in the Central Mississippi

Valley: A Western Tennessee Perspective. SoutheasternArchaeology 15(2):172-181.

1999 Late Period Phases in the Central Mississippi Valley: AMultivariate Approach. In Arkansas Archaeology: Papers inHonor of Dan and Phyllis Morse, edited by R. C. Mainfortand M. D. Jeter, pp. 143-167. University of ArkansasPress, Fayetteville.

2001 The Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Periods in theCentral Mississippi Valley. In Societies in Eclipse, edited byD. S. Brose, C. W. Cowan, and R. C Mainfort, Jr.,pp. 173-189. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington,DC.

2003a Late Period Ceramic Rim Attribute Variation in theCentral Mississippi Valley. Southeastern Archaeology 22(1):33-^6.

2003b An Ordination Approach to Assessing Late PeriodPhases in the Central Mississippi Valley. SoutheasternArchaeology 22(2):176-I84.

2005a Architecture at Upper Nodena: Structures Excavatedby Dr. James K. Hampson. Arkansas Archeologist 44:21-30.

2005b A K-Means Analysis of Late Period Ceramic Variationin the Central Mississippi Valley. Southeastern Archaeology24(l):59-69.

Mainfort, Robert C, Jr. (editor)2003 Archaeological Investigations at Upper Nodena: 1973 Field

Season. Report submitted to the Arkansas Natural andCultural Resources Council, Little Rock.

Mainfort, Robert C, Jr., and Michael C. Moore1998 Graves Lake: A Late Mississippian-Period Village in

Lauderdale County, Tennessee. In Changing Perspectii^eson the Archaeology of the Central Mississippi River Valley,edited by M. O'Brien and R. Dunnell, pp. 99-123.University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Morse, Dan F.1973 The 1973 Field School Excavations at Upper Nodena.

Field Notes 106:3-8.1990 The Nodena Phase. In Toions and Temples Along the

Mississippi, edited by D. H. Dye and C. A. Cox, pp. 69-97.University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Morse, Dan F. (editor)1989 Nodena: An Account of 90 Years of Archeological In-

vestigation in Southeast Mississippi County, Arkansas. Re-search Series 30. Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayette-ville.

Morse, Dan F., and Phyllis A. Morse1983 Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. Academic

Press, San Diego.MuUer, Jon1997 Mississippian Political Economy. Plenum Press, New

York.Neusius, Sarah W. ' >1996 Game Procurement Among Temperate Horticultural-

ists: The Case for Garden Hunting hy Dolores Anasazi. InCase Studies in Environmental Archaeology, edited byElizabeth J. Reitz, Lee A. Newsom, and Sylvia J. Scudder,pp. 273-288. Plenum Press, New York.

O'Brien, Michael J.1994 Cat Monsters and Head Pots. University of Missouri

Press, Columbia.1995 Archaeological Research in the Central Mississippi

Valley: Culture History Gone Awry. Review of ArchaeolQgy16:23-26. - ,j

Payne, Sebastian1972 Partial Recovery and Sample Bias: The Results of Some

Sieving Experiments, in Papers in Economic Prehistory,edited by E. S. Higgs, pp. 49-63. Cambridge UniversityPress, Cambridge.

Perino, Gregory1966 The Banks Village Site, Crittenden County, Arkansas.

Missouri Archaeological Society Memoir 4, Columbia.Phillips, Philip1970 Archaeological Survey in the Unoer Yazoo Basin, Mis-

sissippi. 1949-1955. Papers of the Peabody Museum ofAmerican Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. 60, Cam-bridge, MA.

Powell, Mary Lucas1989 The Nodena People. In Nodena, edited by D. F. Morse,

pp. 65-96. Research Series 30. Arkansas ArchaeologicalSurvey, Fayetteville.

1990 Health and Disease at Nodena: A Late MississippianCommunity in Northeast Arkansas, In Towns and TemplesAlong the Mississippi, edited by D. H. Dye and C. A. Cox,pp. 98-117. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa.

Reitz, Elizabeth J., Irvy R. Quitmyer, H. Stephen Hale, Sylviaj . Scudder, and Elizabeth S. Wing

122

2973 EXCAVATIONS AT THE UPPER NODENA SITE

1987 Application of Allometry to Zooarchaeology. AmericanAntiquity 52(2):304-317.

Reitz, Elizabeth J., and Elizabeth S. Wing1999 Zooarchaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cam-

bridge.Robison, Henry W., and Thomas M. Buchanan1988 Fishes of Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press,

Fayetteville.Scarry, C. Margaret, and Elizabeth J. Reitz2005 Changes in Eoodways at the Parkin Site, Arkansas.

Southeastern Archaeology 24(2):107-120.Schwartz, Charles W., and Elizabeth R. Schwartz2001 The Wild Mammals of Missouri. University of Missouri

Press, Columbia.Sealander, John A., and Gary A. Heidt1990 Arkan<ias Mammals: Their Natural History, Classification,

and Distribution. University of Arkansas Press, Fayette-ville.

Severinghaus, C. W.1949 Totith Development and Wear as Criteria of Age in

White-tailed Deer, journal of Wildlife Management 13(2):195-216.

Smith, Bruce D.1975 Middle Mississippi Exploitation of Animal Populations.

Anthropological Papers 57. University of MichiganMuseum of Anthropology. Ann Arbor.

Stahle, D. W., M. K. Cleaveland, and j . G. Hehr1985 A 450-Year Drought Reconstruction for Arkansas,

United States. Nature 316(6028):530-532.Stahle, D, W., E. R. Cook, M. K. Cleaveland, M. D. TherreU, D.

M. Meko, H. D. Grissino-Mayer, E. Watson, and B. H.

Luckman2000 Tree-ring Data Document 16th-Century Megadrought

over North America. Transactions, American Geophysi-cal Union, Eos 81(12):12I,125.

Stuiver, Minze, and Paula J. Reimer1993 Extended 14C Database and Revised CALIB Radiocar-

bon Calibration Program. Radiocarbon 35:215-230.Swanton, John R.1946 The Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bureau of

American Ethnology Bulletin 137. Smithsonian Institu-tion, Washington, DC.

Tavaszi, Maria M. ' - - '2004 Stylistic Variation in Mortuary Vessels from Upper

Nodena (3MS4) and Middle Nodena (3MS3). Master'sthesis. Department of Anthropology, University ofArkansas.

Trauth Stanley, E., Henry W. Robison, and Michael V.Plummer

2004 The Amphibians and Reptiles of Arkansas. University ofArkansas Press, Eayetteville.

Tuttle, M. P., J. D. Sims, K. Dyer-Williams, R. H. Lafferty III,and E. S. Schweig III.

2000 Dating of Liquefaction Features in the Nexv Madrid SeisnucZone. NUREG/GR-0018. United States Nuclear Regulato-ry Commission, Washington, DC.

Williams, Stephen1957 James Kelly Hampson Obituary. American Antiquity

22(4):398-i00.1980 Armorel: A Very Late Phase in the Lower Mississippi

Valley. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 22:105-110.

123