001threewhowenthomeexhibition.pdf - H-Net

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of 001threewhowenthomeexhibition.pdf - H-Net

1

Exhibition relating to The Calabar Princes

and William Ansah Sessarakoo

The exhibition begins and ends with the story of the Robin Johns, but it incorporates an extended ‘aside’ on a separate but related story. The stories are told against the common back-‐cloth of the Trans-‐ Atlantic Slave Trade and the impact it had on Africa and Europe. The first story is that of Little Ephraim Robin John and Ancona Robin Robin John who hailed from Calabar and who arrived in Bristol in 1773 after having been slaves in Dominica and Virginia. The second story, enfolded in the Robin Johns’ narrative, is that of William Ansah Sessarakoo from Anamaboe in the Gold Coast. All three men were members of privileged (read ‘comprador’) West African families that had trading links with English merchants read (‘they were man stealers’, ‘caboceers’). All three men were treacherously (read ‘short-‐sightedly’!) sold into slavery by the English captains of English ships, and all were able to return to their homes.

2

All that is to say: Since they returned home, the three men represent an infinitesimal minority among West Africans sold into slavery. In other words, their stories, almost uniquely, have ‘happy endings’. While we have a substantial amount of information about these three people, there were millions and millions of captives who were snatched from their homes, transported by human traffickers, and died in bondage far from their homes about whom we know very little. The vast majority lived and died without being painted, without writing about their experiences and without being written about. The stories of the millions ended unhappily and, without a detailed ‘paper trail’ about their existence. It is unlikely that they will attract film directors or producers, authors of those concerned with putting up exhibitions.

3

The maps and engravings on display relate to both stories. The maps show where the privileged men came from and where they returned to— Calabar and (as it is spelled on the map) Amomaboe. The maps also reveal the priorities of the cartographers and their patrons: coast-‐lines are all important!

4

The engravings of Castles in the Gold Coast, such as this one of Christiansborg, carry a dedication to HRH Duke of Clarence. The Duke acceded to the throne of England in 1830 and ruled as William IV until 1837. He was a leading supporter of the Trans-‐Atlantic slave trade. The engravings, which are ‘after George Wallace’, were prepared as propaganda for the pro-‐slaving lobby. They were printed in 1806—just before a crucial vote in the British Parliament. They present an image of the European presence on the West African coast that is benign. Idyllic. False.

5

Several of the castles, including Cape Coast (shown above), contain cells in which captives were held before being shipped across the Atlantic. The lives of the three privileged individuals whose stories are told here provide human interest. However, the larger narrative of which they are a part is, despite the calm sea in the engraving, a tale of disruption, slaughter, and inhumanity on a massive scale. In summarising the stories of three who returned home, I hope to draw attention to the millions who did not, the vast majority about whom the world was and is too often silent.

6

Introduction: The Representation of the Calabar Princes in Bristol Museums The ‘Calabar Princes’ whose story is told here are mentioned in several permanent or semi-‐permanent exhibitions in Bristol, and are of significance on a number of levels. Their first-‐hand, sworn accounts provided legally attested documentation that was cited by those campaigning for the abolition of the slave-‐trade. The story of the Princes can be read in a chapter of Madge Dresser’s Slavery Obscured: The Social History of the Slave Trade in an English Provincial Port, and, at greater length, in The Calabar Princes by Randy J. Sparks. Those are major sources for this exhibition. There were two ‘princes’, Little Ephraim Robin John and Ancona Robin Robin John -‐ and their experiences in Bristol finds a focus in John Wesley’s New Room. But it is a story with repercussions and the wider significance of the issues it raises should always be kept in mind. Briefly -‐ as far as Bristol is concerned -‐ the Calabar Princes arrived in 1773 and were immediately the focus of interest because of a legal dispute. The case involved prominent locals and the ruling was given by the Lord Chief Justice – Lord Mansfield. The case was of lasting importance because it concerned an outrage committed by British man stealers. The ruling required that a Bristol merchant, Thomas Jones, return the Princes to their home in [Old] Calabar. While Thomas Jones was fitting out a ship to carry the men to West Africa (and collect a ‘cargo’ of human beings he was trafficking), the

7

two men spent some months in Bristol. During this time, they became part of the community centred on the New Room, that had been built by members of local Methodist Societies (1739), that is to say by members of a ginger group within the Anglican Church. The Princes spent many hours with one of the leaders of the local Methodist Societies, the Rev’d Charles Wesley. Charles Wesley instructed him in the Christian faith, and, shortly before they set sail for Calabar, he baptized them. The story that I have begun to summarise is told below – partly in Charles Wesley’s words, and, as will be seen, does not end with the baptism I have just mentioned. There is ‘Another Act’, one in which Charles Wesley’s brother, John, also a leader of the Methodist Movement, has a role, and in which other members of the Methodist society in Bristol are involved.

8

On 23 January 1774, Charles Wesley wrote from Bristol to his friend William Perronet. He composed his letter just after baptizing the Princes, and included the following post-‐script from which we can sense the excitement caused by the event: P.S.-‐ I have had with me this month or more, two very extraordinary scholars, and catechumens; two African Princes carried off from Old Calabar, by a Bristol Captain, after they had seen him and his crew

9

massacre their brother, and three hundred of their countrymen. They have been six years in slavery, made their escape hither, were thrown into irons, but rescued by Lord Mansfield, and are to be sent honourably back to their brother king of Calabar. This morning I baptized them. They received both the outward visible sign, and the inward spiritual grace in a wonderful manner and measure. The letter with this brisk, fascinating Post Script was sent and received, but it was only published in 1928. In that year, the editor of The Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society included it in Volume 17. His introduction included: ‘As far as we know this letter has not hitherto been published, and we welcome this copy, furnished by Mr. E. W. Dickinson, Upper Poppleton, near York.’ This exhibition draws extensively on letters and is built around the PS reproduced above. The PS is the ‘clue’, the thread, that we will follow through sometimes confusing historical labyrinth. See Contents for arrangement of material.

10

Contents of Exhibition. See PS just quoted. Charles Wesley wrote: 1. Two African Princes -‐ I have had with me this month or more, two very extraordinary scholars, and catechumens; two African princes -‐

2. The Calabar Massacre -‐ carried off from Old Calabar, by a Bristol Captain, after they had seen him and his crew massacre their brother, and three hundred of their countrymen.

3. Slavery in the Americas -‐They have been six years in slavery, made their escape hither

4. Bristol’s Slave Traders -‐ were thrown into irons,

5. British Law and ‘runaway slaves’ -‐ but rescued by Lord Mansfield, and are to be sent honourably back to their brother king of Calabar.

6. Trophies, Opportunists or Penitents? This morning I baptized them. They received both the outward visible sign, and the inward spiritual grace in a wonderful manner and measure.

7. Appendix: Telling a Bristol Story in Bristol; Sources for that story and others

11

1. I have had with me this month or more two very extraordinary scholars, and catechumens, two African Princes

I want to start with the last three words as a way into this presentation. The ‘two African Princes’ Charles Wesley had got to know at the end of 1773 and beginning of 1774 were originally from Calabar, in what is now South Eastern Nigeria. They had arrived in Bristol from Virginia and they had narrowly avoided being shipped straight back to the plantation from which they had escaped. They were vulnerable because it was claimed that they were ‘runaway slaves’ who had stowed away about The Greyhound. However, seen in another light, they were ‘free Africans’, victims of British perfidy who had been wrongfully carried from their homes, sold and enslaved. While held in The Greyhound in the Kings Roads and under threat of being taken back to Virginia, the Princes had secured the attention of a Bristol Captain and slave-‐trader, Captain Thomas Jones, a.k.a. ‘Jones of the Barton’. Jones knew the ‘Royal House’ from which they came in Calabar and may have seen long-‐term commercial advantage in helping them. Jones secured the release of the Princes and, after further ‘adventures’, put them in touch with Charles Wesley. In his letter, Charles Wesley described the two Africans as

12

‘Princes’. This term is convenient, but it has to be employed with caution. The men – age uncertain but probably quite young -‐ came from an influential family that held sway in Old Town, Old Calabar (after 1906 just ‘Calabar’). They exercised power in a way that would most easily be recognised as characteristic of ‘Merchant Princes’ or of members of a family that held a monopoly over certain commodity -‐ the commodity in this case being human beings.. The two men were known England as ‘Little Ephraim Robin John’ and ‘Ancona Robin Robin Johns’. They were members of the ‘Robin John’

family, and I will refer to them on some occasion as ‘the Robin Johns’ and on others as the ‘Princes’. Over the decades, members of their family had established themselves as ruthlessly effective suppliers of captured Africans for the European traders who sailed up the Creek and Calabar Rivers. They made several concessions to their English-‐speaking business contacts, for example, in addition to using names that British trading partners could recognise, the Robin Johns learnt to speak and write a variety of English – Coastal Trade English. They also assumed, with idiosyncrasies, trappings of British royalty: the senior family member sat on a throne and wore a crown, or two!

13

During the mid-‐Seventeenth Century, the most influential member of the family was Ephraim Robin John. He ‘styled himself’ ‘Grandy King George’, and was probably the older brother of ‘Little (or ’Junior’) Ephraim Robin John’, introduced above. He may have been the uncle of the other Prince featured in this exhibition, Ancona Robin Robin John. In the use of Grandy -‐ or ‘Grandee’ -‐ we can hear a reminder of the Europeans who opened up trade in West Africa in the years before the British arrived. And in ‘King George’ we can recognise the House of Hanover and the British connection. The doubling up of titles and the borrowing of a royal name makes for a sense of similarity and difference, proximity and distance, imitation, superfluity and parody. The (carefully staged) ‘family picture’ above is not of Grandee King George Ephraim Robin John, but of a later ruler in Old Calabar. I have included it because the poses and costumes shown catch something of the Robin Johns and of the’ face’ they presented to Europe. ‘Reading the pictures’ may help those trying to enter imaginatively into the world from

which the Robin Johns came. Charles Wesley and – as we shall see – the wider Methodist community were intrigued by the ‘royal’ connections of the two men. Describing them as ‘Princes’ and drawing attention to their regal connections came easily to those with whom they were in contact. In ‘title-‐obsessed’ England the status of the Robin Johns

sent shivers of excitement down Methodist spines

14

The story of how the Princes reached Bristol is told in some detail in the pages that follow, at this point I am going to look at the sequence by which they came to the attention of the Rev’d Charles Wesley, who at the beginning of the 1770s was living with his wife and children in central Bristol while exercising pastoral responsibility for the Methodist Society members who met at the New Room in the Horsefair. As we have seen the Robin Johns asked to be introduced to Charles Wesley shortly after their arrival in Bristol. The letter from Little Ephraim to Charles (reproduced below) is tangled, unpunctuated, headlong, but it provides an account of the linking up with Wesley. It has been transcribed by Randy J Sparks whose major study of the Calabar Princes I have already referred to and to whom I am indebted for this:

after this Mr Jones brought us in his own house and then treated us well

and send us to school to Learn to Reading and from there we Desire Mr

Jones we were wanting to Read the Lord word from thence them People

here with you and mention your name to Mr Jones if him had & enquire

for you be Better minister to teach us that we may soon come to have

some knowledge of God then we was brought to you by Mrs Forrest after

which you read to us that which we were so new and good to us that we

were glad to hear it every Day and we still we find Better and Better

15

From this it appears that the interest in meeting Wesley was because the Robin Johns wanted to further their (formal) education -‐ ‘... to learn to Reading...’. In trying to understand what this meant, we should recognise that the princes were already literate. They had demonstrated their ability to write letters in English by, for example, writing to Jones of the Barton from the bowels of The Greyhound. Literacy had been decisive in enabling them to control parts of their lives – even when in chains. As we shall see: Ephraim may have spent some time in Liverpool and learned to read and write there.

The letter continues by expressing a wish to read the Bible -‐ we Desire

Mr Jones we were wanting to Read the Lord word. Holy Scriptures were a world away from the shipping news and the lists of trade goods that those trading on the West Coast of Africa usually wrote about. As a result, this request must prompt questions. Randy J Sparks devotes several pages of his sharply-‐focused study to pondering what might have been behind the Princes’ request. Did it, for example, emerge from, for example, a desire to make a strategic alliance, or did it spring from a thirst for spiritual refreshment? Leaving the question of motive hanging, there is a simpler question to address, namely: How was the introduction to Charles Wesley effected? To which can be added: ‘What pattern of contact was established by the introduction?’ Little Ephraim indicates that Jones of the Barton had elected the help of an intermediary, Mrs Forrest, who had conducted him to Charles Wesley. The princes had, it seems, received daily tuition. This, he wrote, had allowed them to grow in

understanding: we was brought to you by Mrs Forrest after which you

16

read to us that which we were so new and good to us that we were glad

to hear it every Day and we still we find Better and Better One can appreciate that Charles would have been gratified by this account. Although he expressed himself in flawed, Little Ephraim was adept at striking the chords that resonated with Methodists. I do not know how fluent Little Ephraim’s was in speaking, reading and writing English at the time of his capture or at the time of his arrival in Bristol. A Liverpool slave-‐trader with links to Calabar, Ambrose Lace, wrote to Thomas Jones about a ‘Little Ephraim’ who had spent time in Liverpool with him and on whom he claimed to have spent some £60 worth of lessons. But it is not absolutely clear whether or not this was ‘our’ Little Ephraim, but it seems likely that it was. Charles describes the Princes as ‘extraordinary’. They were certainly impressive and unusual, and one can, I think, sense that Charles Wesley regarded them as something of ‘a catch’. The press coverage of their baptism includes an element of ‘parading’. However, they were not the only African Princes or princely Africans to set tongues wagging in Eighteenth Century England. We have no portraits of the Calabar princes, but we have pen portraits that suggest they were very presentable. In an anonymous article published in John Wesley’s Arminian Magazine some years after the Princes had left Bristol, -‐ an observer wrote of the Princes:

17

I never saw two such Negroes before. They were about five feet, nine inches, well shaped neither fat nor lean, and exactly proportioned.

They were perfectly well bred: all their motions were easy, proper, graceful. Notwithstanding their colour, there was something agreeable in their countenance. But it was manifest differences both in their look and carriage: Ancona was all sweetness; Ephraim all a Prince. No one could conceive that they knew what slavery meant.

Given that Captain Thomas Jones would want those he was responsible for to dress well, I suspect they cut fine figures in the streets of Bristol. They clearly impressed the author of the article just quoted from – even though his ‘Notwithstanding their colour’ places him among those for whom only the fair could ever be fair! Members of the Moravian Church in Bristol also took a particular interest in the visitors and Moravian church records reinforce the positive impressions left on those quoted above. In relevant papers dated 15 July 1774 the princes are described as ‘2 pretty young men.’ Reference can be made to other Africans who found themselves in somewhat similar positions to the Robin John in Eighteenth Century England, and pictures of those ‘other Africans’ help us to imagine the Robin Johns. The contemporaries and near contemporaries included William Ansah Sessarakoo, Olaudah

18

Equiano, Francis Barber, Ignatius Sancho and Phillis Wheatley. These examples will delay us for a moment. To fill in the local situation, I will add notes on Africans and men of colour in Bristol at around the time when the Calabar Princes were here.

William Ansah (or Unsah) Sessarakoo was the son of a slave-‐trader, kidnapped and treacherously sold off in Barbados. He was rescued, and feted in London. He inspired writers and he returned to Africa.

Olaudah Equiano. Sometime slave and sometime slave-‐trader, Equiano (a.k.a. Gustavus Vasa) was both an author and a Methodist. (See Ch. 10 of his Interesting Narrative for an account of his spiritual journey.) An activist, Equiano bore testimony to outrages by English slave traders and was involved in schemes to resttle ‘Poor

Blaks’ in Sierra Leone. Francis Barber. Jamaican-‐born Barber was a servant and companion to Dr Johnson’s who was a friend of John Wesley. Both men were part of the London world in which the Wesleys moved.

19

Ignatius Sancho. A letter writer, composer, and actor, Sancho had a wide acquaintance among creative Londoners. On 20 October 1769, Sancho wrote: I am for my sins turned Methodist.

20

The experiences of William Ansah (or Unsah) Sessarakoo (fl. 1736–1749) -‐ the third who went home -‐ overlapped in some startling respects with those of the Calabar Princes and I want to spend some time on

him. This is by nature of an ‘aside’ from the main topic: the Calabar Princes. Sessarakoo’s father, Eno Baisie Kurentsi aka "John Corrente" or Currantee, was an influential trader in gold and human beings based in Anomabo in what is now Ghana. See inset map of the Gold Coast in the 1787 map of Africa with ‘Annamaboe’ marked (There are various spellings of that place name).

21

Note on the Forts of the Gold Coast The Gold Coast includes an unusually high number of forts, ‘stations’ or castles since all those ‘nations’ trading along the coast that was rich in gold required bases. The relevant ‘nations’ included Portugal, Spain, France, Brandenburgh-‐Prussia, Sweden, the Netherlands, England, and Denmark. Kurentse Kurentsi entrusted his son, William Ansah Sessarakoo, (and a companion) to an English sea captain who agreed to take the boys England. However, the Captain reneged on his promise and sold Sessarako and his companion (who drops out of the narrative at this point) in Barbados. Learning of this, Kurentsi refused to trade with the English until his son was brought back to him. Hit in their pockets by this ultimatum, members of the Royal African Company redeemed Sessarakoo and took him, first, to London where, he was treated as a prince, the "Prince of Annamaboe”. While in London, Sessarakoo was presented to George II and, in 1749, was painted by Gabriel Mathias. In London, he attended a performance of a play based on Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko that was about an African prince who had

22

been treacherously sold into slavery in the Americas. Sessarakoo’s responses to the staging of a fictional life that resembled his were closely watched, and his deep emotional reaction was noted. It was seen as proof of his fine sensibility.

Sessarakoo’s experiences provided the inspiration for a pamphlet by William Dodd's entitled The African Prince (1749), and fed into another publication: The Royal African: or, Memoirs of the Young Prince of Annamaboe (1750). In that volume,

an unidentified author drew on existing publications, on Sesarakoo’s tribulations and on an acute appreciation of the way Anglo-‐French rivalry found expression in West Africa. The volume suggests that as a boy Sessarako had spent time with English soldiers in the fort at Annamaboe, and from this we may deduce that his English was good. There is no suggestion that Sessarakoo had a hand in composing The Royal African, but there are moments when his pulse can be felt behind the prose.

24

THE ROYAL AFRICAN:

OR, MEMOIRS OF THE

YOUNG Prince of Annamaboe. Comprehending A distinct Account of his Country and Family;; his elder Brother's Voyage to France, and Reception there;; the

Manner in which himself was confided by his Father to the Captain who sold him;; his Condition while a Slave in Barbadoes;; the true Cause of his being redeemed;; his Voyage from thence;; and Reception here in England.

Interspers'd throughout With several HISTORICAL REMARKS on the Commerce of the European Nations, whose Subjects frequent the Coast of

Guinea.

To which is prefixed A LETTER from the AUTHOR to a Person of Distinction, in Reference to some natural Curiosities in Africa;; as well as explaining the Motives which induced him to compose these

MEMOIRS.

25

An extract from the Memoires, Sessarakoo’s experiences of perfidy in Bridgetown, Barbados, that recalls the sort of betrayal suffered by the Robin-‐Johns.

When the Captain had sold him, and he was put into a Boat to be carried to his Master, he thought he was going on board the Ship that was to carry him to England. But what Language can express his Surprize, when from the rough Usage that he met with from two Slaves that were in the Boat, he had no Room left him to doubt that his Condition was the same with theirs? It must be left to the Reader's Imagination to frame a Notion of his Distress, which will be so much the harder, as the Freedom and Happiness of our Situation hinders us from ever beholding a Sight that any way resembles it. It must assuredly have struck him with a Horror, for white Men in general;; have filled his Mind at once with as black Thoughts of them, and with better Foundation than some of these, affect to have for those of his Country with very little Cause.

Sessarakoo (fl 1736-‐1749) never visited Bristol. However, it has been suggested ‘Gonglass’/ Gon Glass, the French-‐speaking son of a Gold Coaster who visited the Moravian chapel in Upper Maudlin Street on 4 April 1759, may have been his ‘brother.’ Kutentse was certainly aware of the need to play off rival European nations against one another and to this end ‘maximized his options.’

26

Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745 – 31 March 1797) Equiano’s Interesting Narrative, published 1789, is an account of a life that moved through many phases and at some points overlapped with the Robin Johns. For example, he was, like the Robin Johns, both slave-‐trader and slave. The Interesting Narrative constituted a major contribution to the Abolitionist Cause and Equiano travelled extensively speaking about the book and selling copies. Chapter 10 is a spiritual autobiography that charts his decision to join the Methodist movement -‐ a commitment similar to that made by the Robin Johns.

28

Francis Barber, 1735-‐1801. Barber was brought to England in 1750, and two years later entered the employment of Dr Samuel Johnson as a valet. The Great Lexicographer came to rely heavily on him and was generous to him in his will. Johnson was a critical admirer of John Wesley and he had quite extensive social intercourse with members of the Wesley family.

29

Ignatius Sancho, whose mother died giving birth to him on board ship in 1729, was named after Sancho Panza. Taken to England as a baby, he was encouraged in various literary, academic and creative directions by John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu. Sancho was a man of parts and had a wide acquaintance. After Dr Johnson’s death, he became a green grocer, Thomas Gainsborough painted his portrait, and Lawrence Stern published the letters he had written to him. Sancho wrote: In Africa, the poor wretched natives blessed with the most fertile and luxuriant soil -‐ are rendered so much the more miserable for what Providence meant as a blessing: the Christians' abominable traffic for slaves and the horrid cruelty and treachery of the petty Kings encouraged by their Christian customers who carry them strong liquors to enflame their national madness – and powder – and bad fire-‐arms – to furnish them with the hellish means of killing and kidnapping.

30

Phillis Wheatley (?1753 – 1784), was carried from Africa to America aboard The Phillis in 1761 and was given a first name to mark that fact. Against the odds, she made a reputation as a poet. Thomas Paine carried her work in the Pennsylvania Gazette (1776) and Wesley included it in The Arminian Magazine (1781; 1784). She impressed Selina Countess of Huntington with verses written to mark the ‘Exit from this transitory state to dwell in the celestial state of bliss’ of George Whitfield in 1770. (See below.)

AN ELEGIAC POEM, ON THE DEATH

OF THAT CELEBRATED DIVINE, AND EMINENT SERVANT

OF JESUS CHRIST, THE LATE REVEREND, AND PIOUS

GEORGE WHITEFIELD

Chaplain to the Right Honourable the Countess of Huntingdon, &c. &c. Who made his Exit from this transitory State, to dwell in the celestial Realms of Bliss, on LORD's Day 30th of September, 1770, when he was seiz'd with a Fit of the Asthma, at NEWBURYPORT, near BOSTON, in NEW ENGLAND. In which is a Condolatory Address to His truly noble Benefactress the worthy

31

and pious Lady HUNTINGDON, – and the Orphan-‐Children in GEORGIA; who, with many Thousands, are left, by the Death of this great Man, to Lament the Loss of a Father, Friend and Benefactor. By PHILLIS, a Servant Girl of 17 Years of Age, Belonging to Mr. J. WHEATLEY, of Boston: – And has been but 9 Years in this Country from Africa. It included:

Great COUNTESS! we Americans revere Thy name, and thus condole thy grief sincere: We mourn with thee, that TOMB obscurely plac'd, In which thy Chaplain undisturb'd doth rest. New-England sure, doth feel the ORPHAN's smart; Reveals the true sensations of his heart: Since this fair Sun, withdraws his golden rays, No more to brighten these distressful days! His lonely Tabernacle, sees no more A WHITEFIELD landing on the British shore: Then let us view him in yon azure skies: Let every mind with this lov'd object rise. No more can he exert his lab'ring breath, Seiz'd by the cruel messenger of death. What can his dear AMERICA return? But drop a tear upon his happy urn, Thou tomb, shalt safe retain thy sacred trust, Till life divine re-animate his dust.

32

Africans and people of African Descent in Bristol in the 18th and early C.19th.

There were a number of Africans living in Bristol during the Eighteenth Century. Despite the fact that some were employed in major household, their lives were restricted and they were vulnerable because they were easily dubbed ‘Runaway Slaves.’ ‘Runaways’ could be apprehended and those who sheltered them put themselves in danger.

• .’

This notice, dated 15 November 1746, includes the offer of a reward for the return of ‘Mingo’.

33

The final paragraph reads: ‘All persons are hereby forbid entertaining the said black at their peril.’

Some noted Black and mixed heritage residents of Bristol during the C. 18th

Among the Black and mixed heritage residents of Bristol during the Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century – some of whom would have been in the city when the Robin Johns were here -‐ were Richard Cornwall. He was described as ‘a Christian Negro’ and he worked for a Captain Day who lived on College Green.

During the 1750s, John Quaco, a freeman, lived in Princess Amelia Court, Pipe Lane, off Colston Street.

Unusually, Bristol plantation owner, Nathaniel Milward recognised the two sons, Edward and Benjamin, born to him by his mixed-‐ race mistress. In his will (1773), he instructed that, on reaching the age of 14, the boys should be bound apprentices at a metal workshop in Welshback.

In the 1760s, John Pinney of Great George Street, brought Pero Jones from St Nevis to be his personal servant. Pero

34

arrived in the 1760s and served his master until his death in 1798.

In addition to Pero Jones, the Pinney household also included Frances Coker who was maid to John Pinney’s wife. Frances was a freed slave but the extent to which she could live out her liberty was limited. She died in 1820 and was buried in the Baptist cemetery in Redcross Street.

When Thomas Clarkson visited Bristol in 1787 to carry out research into the slave trade and the conditions on ships flying the Union Jack off the West African coast, he interviewed John Dean, a free black man. Dean testified to having been tortured on board a slave ship.

Taken in hand by a Moravian minister, the Rev’d Henry Sulgar, Clarkson was shown proof of the affidavits sworn by the Robin Johns about the Calabar Massacre. Important sworn texts had appeared in John Wesley’s Arminian Magazine. From the information gathered together for this exhibition, it would appear than documents held at the Moravian Chapel, the New Room and by Elizabeth Johnson would have offered Clarkson opportunities for his research.

35

James Martin, a freed man, died in 1813 or 1814 leaving money to the African Institution, a London-‐based organization set up to spread the word of God in Africa.

36

The Story of the Robin Johns, continued

Towards the end of 1773, the Robin Johns must have told Charles Wesley they wanted to be baptized. He agreed to prepare them for baptism, and they thereby became ‘catechumens’ as well as ‘scholars’. While the three men were thinking about the rite, they must have been aware of the notion -‐ held by some on both sides of the Atlantic -‐ that those who had been baptised could not be enslaved. The two final sentences in Charles Wesley’s Post-‐Script quoted above address any suggestion that the Robin Johns regarded baptism as some kind of protection or ‘insurance’ against being enslaved once again. Charles Wesley wrote:

They received both the outward visible sign, and the inward spiritual grace in a wonderful manner and measure.

There was widespread coverage of the Baptism in newspapers across the country. (See below.)

37

two African Princes carried off from Old Calabar, by a Bristol Captain, after they had seen him and his crew massacre their brother, and three hundred of their countrymen.

With these words, we are taken to the heart of the Calabar Massacre, and it is necessary to establish some geographical and historical details. The Massacre took Place near Calabar. Old Calabar Old Calabar was, primarily, the Efik-‐dominated centres of Creek Town, Old Town, Henshaw Town, Cobham Town, and Duke Town in what is now S E Nigeria. These towns stood or stand on the banks of the Calabar and Great Kwa Rivers, and beside the creeks of the Cross River.

The ‘Old’ was officially dropped in 1904, and two years later the town ceased to be the seat of the British colonial government for the Niger coast and Southern Protectorate. Maps from the period are fairly accurate regarding the coast, but vague when it comes to the interior. For example, on Sayer’s map of 1787, the River Niger was shown flowing westwards! This was because the Niger Delta was not recognised as the ‘point’ at which the great river spilled into

38

the Bight of Benin. (Note: When on display at the New Room, this text was accompanied a copy of both parts of the Sayer 1787 map. (Below Cartouche of the Boulton map.)

‘Africa, with all its States, Kingdoms, Republics, Regions, Islands, & cca. Improved and Inlarged form D’Anville’s Map to which has been added A Particular Chart of the Gold Coast wherein are Distinguished all the European Forts, and Factories by S. Boulton and also A Summary Description relative to the Trade and Natural Produce, Manners and Customs of the African Continent and Islands. 1794 (dated) 41 x 49 in (104.14 x 124.46 cm)’

Probably the most important representation of Africa produced in the 18th century, the Boulton map is based in part upon the work of

39

D'Anville. It depicts the continent in full with insets of the Gold Coast (or Ivory Coast, or Guinea.) This map is unique in that it is a serious attempt to bring together all the accurate scientific knowledge about the African continent available at the time. In contrast to many other Africa maps of the period there is almost no attempt to fill the 'unknown' regions of the interior with fictitious beasts, kingdoms, and geological features. Boulton himself explains that 'The inland parts of Africa being but very little known and the names of the regions and countries which fill that vast tract of land being for the greatest part placed by conjecture it may be judged how absurd are the divisions traced in some maps and why they are not followed in this.' Despite this, this map provides a wealth of information both in the form of a gazetteer printed in framed text boxes here and there on the map, and as political and geographical features. The cartographer attempts to depict known and unknown parts of the continent with actual data reported by both contemporary and ancient travelers. In most cases it is extremely difficult to identify specific sources because much of the data is vague and tentative. Boulton, for example, notes a community of Jews near what would today be Mali. Though a very small community of Jewish traders did live in Mali in the 15th century, most had been killed or converted to Islam by the 16th. It may have been that Boulton's sources here were out of date. Boulton also relies heavily on the geography of Claudius Ptolemy, acknowledging this source in numerous notations which range from commentary on local peoples to the courses of important river systems. Clearly much of the map is focused on commerce but where

40

information is available, Boulton makes includes information on local commercial products and mineral wealth. There are also copious notations on caravan routes, especially those which were known to concern crossings of the Sahara. Following Ptolemy, Boulton includes a number of river systems which appear out of nowhere and run nowhere. With regard to the White Nile, which Boulton presumes correctly to be greater than the Blue Nile, he follows the ancient 'two lakes at the base of the Mountains of the Moon' theory. In the southern half of Africa there is considerably less information on the interior except for those lands mapped by the Portuguese along the Congo and Zambezi Rivers. The regions around the Zambezi, called ‘Monomotapa,’ are particularly interesting as many considered this area to be the Biblical Land of Ophir, where one could discover the mines of King Solomon. Just north of Monomotapa we find an embryonic representation of Lake Malawi, here called ‘Maravi.’ In South Africa the Dutch Company is strongly established and the region is well mapped deeply into the interior. See http://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/Africa2-‐boulton-‐1794 Some amendments

41

Old Calabar was, primarily, the Efik-‐dominated centres along the banks of the Calabar and Great Kwa rivers, and beside the creeks of the Cross River

42

Wesley writes of the ’Calabar Princes’ being ‘carried off,’ and in his use of this expression he introduces a distance between the princes’ experience and the experience of almost all other Africans, or ‘Negroes,’ who were being captured and sold. Little Ephraim and Ancona were men of substance and authority; they mattered to their influential family, and they were ‘freemen’ by the standards of those concerned in the events. In this context expressions such as ‘carrying off’ or ‘kidnapping’ were deemed appropriate. In a true sense, however, those transported unwillingly across the Atlantic were stolen, carried off, kidnapped. The Bristol Captain referred to was James Bevins, and the crew were serving on The Indian Queen, and his Chief Mate was William Floyd, who has other roles to play in this saga. The brother mentioned was Amboe Robin John, actually killed, it would seem, by men from Duke Town rather than the English crew – though the English men could be

43

said to bear moral responsibility because he was a guest on their ship and they handed him over to men determined to kill him. The scene Wesley briefly describes is one of brutal slaughter that caused the estuary to run red with blood. Whether any men from Old Town escaped does not seem to have been investigated. The figure of 300 may have been arrived at because that was the number of Old Town men in the initial delegation. The assumption may have been that all the men of Old Town were killed. Little Ephraim, Ancona and Amaboe were not the only members of the Robin John family among the delegates aboard English ships. Others were thrust into the slave ship’s hold.

Because incriminating information about piratical behaviour of British seamen during the Calabar Massacre was sworn to before British legal

44

representatives it became a stick that could be used to beat the drum of the Abolitionist cause. It could also be used to batter the Pro-‐Slave Trade Lobby. The episode left a significant ‘paper trail’ that included depositions sworn by the Robin Johns and William Floyd. John Wesley ensured these became widely available by publishing extensive extracts in The Arminian Magazine (1783). When Thomas Clarkson visited Bristol in the middle of 1878, he met an ‘amiable minister of the gospel belonging to the religious society of the Moravians …’ And subsequently wrote: ‘From him I first procured authentic documents relative to the treacherous massacre at Calabar.’ He added: ‘This cruel transaction had been frequently mentioned to me; but as it had taken place twenty years before, I could not find one person who had been engaged in.’

The ‘amiable minister’ was, Henry Sulgar, and the documents referred to could have been the depositions mentioned above. Clarkson moved on from Bristol to Liverpool, was introduced to Captain Ambrose Lace. (See below.)

45

they have been six years in slavery, made their escape hither ‘Six years’ refers to time spent in Dominica (1767), where the Calabar Princes were bought by a ‘French doctor’, and then in Virginia, where they were sold to a Captain Thompson.

A linen market in Dominica, c 1770. Dominica had a strong French flavour. Under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1763), the French had ceded the island to the British but it retained its French character and it is not surprising to hear that the doctor who bought the Robin Johns was French.

46

The Robin Johns were among, 2,672 captives who arrived on Dominica in 1767. There was considerable movement between Dominica, other islands and the mainland. Some of those brought from Calabar were probably were sold on to plantations elsewhere. In his letter to Charles of 17 August 1774, Little Ephraim wrote of their

time on Dominica: … we was treated acording to what they could make

of us upon the whole not badly but we were determined to get home. Prompted by this comment one wonders what could the Doctor ‘make’ of the princes? How much, if anything, did he learn of, for example, about their family business and their language skills? It is good to find the word ‘determined’ here because it is one that comes to mind when listing the qualities shown by the two men. They were driven by a powerful desire, ready to take risks in order to improve their chances of getting home. In this instance, the calculation did not pay off, at least not immediately. The princes trusted a Captain William Sharp who promised that if they stole aboard his sloop he would take them to Calabar. Sharp reneged on his promise, took the princes to Virginia and sold them to a Captain Thompson. Bondage in Virginia proved much more painful than in Dominica for the Robin Johns. Writing on 17 August 1774, Ancona described Thompson

as ‘exceeding badly man ever I saw. The abuse endured included restraint and floggings -‐ ‘ for nothing at all’ -‐ or because they could not perform assigned tasks. As an example, Ancona writes that he was

47

flogged -‐ ‘because I could not Dress his Dinner for him not understanding how to [do] it.’ Perhaps conscious the account he was writing was for Charles Wesley, Ancona introduced a religious dimension, recording that Thompson did not observe the Sabbath and that he uttered many profanities. Ancona struck other religious notes. For example, his monotheism and his faith in a responsive God come through in his reference to ‘Almighty Great God.’ This reflected the fact that he had learned to expect higher standards of Christians and may have prompted recollection of the distress Thompson’s behaviour caused a visiting Christian, identified as William Leber. It seems that one Sunday when Thompson was flogging Ancona, Leber interceded, -‐ without effect. Ancona ads that Leber ‘seemed to be a good Christian’ who was distressed by Thompson’s profanities. From another reference, it appears that Ancona and Leber had meaningful conversations. We read ‘-‐ when (Leber) were upon Deck then (he asked) me what make my Master always swear.’ This intriguing enquiry in which a white man asks a black man to explain the objectionable conduct of another white man is given what a modern sensibility would regard as a somewhat pat resolution -‐ in that the blasphemer was suddenly struck down. In Ancona’s words: ‘so nect Day (Thompson) was walk upon Deck and say his Belly ache and fall Down there he Dead upon Deck then we all were so fread [afraid].’ Ancona described the calm that followed Thompson’s death and saw the hand of God at work. Thompson had been ‘so bad man and wicked’ that – more theology -‐ ‘Great God above’ punished him with death!

48

Three weeks after this dramatic execution, the princes escaped with a Captain O’Neill on The Greyhound in 1773 and set sail across the Atlantic.

49

made their escape hither, were thrown into irons O’Neill sailed across the Atlantic and brought The Greyhound safe to the Kings Roads/ Kingsroads in the Severn Estuary. Once there, he reneged on his promise to take the Princes to Calabar. On the map below, find Portishead, Sabrina (Severn Estuary) and Kingsroads

Perhaps in search of a quick profit, O’Neill negotiated with a William Jones to return the ‘runaway slaves’ who had ‘stowed away’ on his ship to the planation they had left. To effect this, he had the princes transferred to The Brickdale where they were held in chains. It can well be imagined what a cruel blow this was to the princes. Once again, they found they had misplaced their trust and once again their hopes – that had been building up – were cruelly dashed. They experienced yet another betrayal. Little Ephraim described the harrowing experience they went through, a sequence of events that he interpreted in terms of divine intervention. He wrote:

50

But (O’Neill) altered his mind and never return to us but order the pilot to put us aboard [illegible] port vessel which did to our great surprise & horror when they come to put on the irons we then with tears and trembling began to prayer to God to helpe us in this Deplorable condition we lay for 13 days among the wretched transport But hear the Lord helpe us he putting to our heart to writing to Mr. Jones who throu providence of the Lord we enquire in some the people but had no answer this Made Ancona’s heart fail But I saying I will yet go write once more too this had no answer But the Lord was good stayed the wind which prevented our sail then I write again to Mr. Jones which moved him to pity, he then a send to inquire after us the prisons knew us well then come down Mr Jones and when we saw him I was great joy thankfullness told him our pity us [piteous] case.

“Surprise & horror” was followed by “tears and trembling,” and by Ancona’s heart falling. However, steps were also taken: enquiries were made and letters were written. All this was carried out while ‘the Lord was good stayed the wind’ and the eventual outcome was “great joy thankfulness.” Jones’s request to the captain of The Brickdale that the princes be freed was initially rejected. However, he secured a writ of habeas corpus and the Africans eventually set foot on English soil. They were immediately arrested at the suit of Sir Henry Lippincott, owner of The Greyhound, who claimed they owed him for bringing them across the Atlantic. No longer runaways or stowaways, the princes were now debtors.

51

At this point, it seems, Little Ephraim wrote again, this time to Lord Mansfield, just the right man! And secured a good result:

from thence I wrote to Lord Mansfield who send and fetch up to

London

While the effort and resourcefulness of Little Ephraim is easily apparent and does not come as a surprise, the actions of Captain Thomas Jones require some attention since he played several roles. As a captain, Jones sailed the Triangular Route, as a Merchant Venturer he invested in ships on the same course -‐ and as a member -‐ or, at least, a respected figure at the New Room, he stood with the Calabar Princes at their baptism. Captain Thomas Jones A lasting reminder of Captain Jones’s involvement with the Efik Connection is provided by the Calabar Bell that is held by the Society of Merchant Venturers in Bristol. The inscription reads ‘From Thomas Jones of Bristol to Grandy Robin John of Old Town.’ The bell dates from 1770 and appears to have been intended as a gift for the Grandee King George introduced above.

52

In her invaluable book on the slave trade in Bristol, Madge Dresser links the bell with the following request that the Grandy had sent to Jones: ‘Pls send me one larg bell to make chop for my war canow.’ The reasons why the Grandy wanted a bell can be guessed at since bells play important roles in British culture, particularly among seafarers -‐ the very Englishmen who turned up in Calabar. Bells also feature in various Ekpe, or Egbo, rituals. As a result, there are records of gifts of bells being made to Efik groups. In the absence of any other suggestion about how ‘chop’ should be construed, I tentatively suggest the Grandy wanted to ‘cut a dash’ with the bell. It can be appreciated that Jones might have responded positively to Grandy’s request because it provided an opportunity to ingratiate himself with trading partners. The presence of the bell in Bristol rather than Calabar is surprising since we might have expected it to be in Calabar. In Slavery Obscured, Madge Dresser thanks Stephen Behrendt for the suggestion that the bell was returned to sender on the death of the recipient. (Dresser: 94.) Copyright of the picture of the Calabar Bell is held by The Society of Merchant Venturers.

53

but rescued by Lord Mansfield, and are to be sent honourably back to their brother king of Calabar Wesley’s account omitted details, including the intervention of Thomas Jones and the arrest of the princes at the suit of Lippincott. He moved, at a single bound, to refer to the action of the Lord Justice to whom the Princes had addressed themselves.

In the course of a distinguished career, Chief Justice Mansfield made many positive contribution to the English legal system. He was, however, sometimes ‘cautious’ and, in King v Lippincott he found a solution to the various claims before him that saved him from making a ruling on whether or not slavery could exist on English soil. His settlement

included extracting an undertaking from Jones that he would convey the princes to Calabar. ‘Rescued’ is not the first word that comes to mind when describing Mansfield’s role, but it allows Wesley to sprinkle him with a gallantry, and to cast a near contemporary from his Westminster School days in a good light. His ruling obliged a capable man with a vested interest in completion to get the Princes a passage home. As we have seen, the princes had often been let down, but at this point they had a commitment in

54

writing from a man in the public eye who had several reasons for keeping his word. In the present context, Mansfield is well known for the ruling he gave in the Somerset(t) Case -‐ though the implications of that ruling continue to provide fertile ground for discussion. He is also well known as the considerate guardian of his cousin’s biracial daughter, Belle. The painting of Belle with Mansfield’s daughter was once attributed to Zoffany and tells part of the story of his ward’s upbringing. One enquiry prompted by King v Lippincott concerned an investigation into the Robin John family and raised the questions: Who, exactly, are Little Ephraim and Ancona? The search for answers prompted Thomas Jones to write to Ambrose Lace for information. Lace made some suggestions about family relationships and bout his contacts with the family. For example, he pointed out that he had had a Little Ephraim -‐ possibly one of the Calabar Princes, staying with him in Liverpool for a time. He added that he had spent money on Little Ephraim’s education and expressed the hope that ‘when his fathers gone I hope his son

55

will be a good man.’ (See Letter below and Dresser, p. 94, f/n 100.) This morning I baptized them. They received both the outward visible sign, and the inward spiritual grace in a wonderful manner and measure. Charles Wesley’s observation about the outward and inward dimensions indicates that in his opinion, the Robin Johns were sincere converts. This comment may have been prompted by the need to challenge those for whom the Princes’ baptism was a calculated move prompted by self-‐interest. The baptism was widely reported by the papers that were springing up in towns and cities. News about the African princes was carried by The Caledonian Mercury (23 Feb. 1774), The Stamford Mercury (24 Feb.), The Newcastle Courier (26 Feb.), and The Newcastle Chronicle (26 Feb.).:

The final sentence of the extract reads:

They are about to return to their own country, and are resolved, according to their power, to propagate the gospel among their brethren.

56

The Story of The Calabar Princes seems, at this point, to be set up so that the newly baptized Princes return to Calabar. However, it must be said that there were further twists before the Calabar Princes reached home and when they got home. Briefly -‐ and without Charles Wesley’s ‘PS’ to guide us, we have to absorb the information that the Thomas Jones was as good as his word. He fitted out a ship, The Maria, and the Princes embarked on it for West Africa. For no reason I can fathom, Jones engaged William Floyd as captain and this proved disastrous. Drunk and unwilling to take advice, Floyd seems to have been responsible for the Maria floundering on one of Cape Verde Islands. The crew and the passengers made it to the shore and were eventually rescued and taken back to Bristol. They arrived distressed and with, it seems, concern about what God’s plans for them were and whether Jones would secure them berths in another ship. In Bristol, they were supported once again by Jones, by Methodist and by Moravian friends. Once again, they began to worship at the New Room, and welcomed the opportunity to meet, take communion from and talk with John Wesley. In due course, a ship was ready and they were restored once again to their family in Old Town. From letters to Elizabeth Johnson and to Jones, it seems they continued their religious observance in Calabar, and two Moravian brothers travelled out to support the fledgling mission. Though welcomed by members of the Robin John Family,

57

this is only the midpoint in the tale. Support from Bristol for the princes in what was in effect a Calabar Mission resulted in two Moravians, the Syndmans brothers, devout Christians and skilful workers in wood and metal, sailing for Calabar. The fact that Moravians rather than Methodists took up the challenge reflected the well developed missionary tradition among the Moravians, who had, for example, supported a venture in South Africa for some fifty years. Apart from involvement with America where Coke and Asbury were tending a special flock, Methodism was not yet ready to ‘go out into all the world.’ It seems that the Syndmans were well received on arrival in Old Calabar and were, for example, introduced to senior members of the Robin John family. However, subsequent letters to Miss Johnson and to Thomas Jones, told of the death through sickness of both men within four weeks. Madge Dresser tells the story by quoting from reports to the Elders’ Committee of the Bristol Moravian Congregation. In the papers for June 1777, we read:

By letters from Old Calabar which Miss Johnson communicated to [the Moravians] Br[other] Steinhauser, we learned that Mr Syndmans and his Brother, who went from here to Guinea to see whether Missionaries might be settled here got safe to Calabar but died both of a sickness within 4 weeks

The same Moravian source also carries the information that …. the King of Calabar in his letter to Mr Jones the Merchant and owner of the ship mentions their Death and writes, that he is sorry for it. Miss Johnson wishes that a mission unto those parts might still [be tried].’ BULSC, Bristol Elders’ Committee minutes, 13 June, 1777, Moravian Collection. Quoted Dresser, 95.)

John Wesley established the Arminian Magazine and in 1783 it carried extracts from the sworn depositions regarding the Calabar Massacre

58

and some information about the Princes in Bristol and in Calabar. For example, the princes reported that their habit of reading the Bible had initially caused laughter, but that laughter had been silenced. In 1788, hopes of Methodist support for African missions were raised by the Rev’d Thomas Coke, but John Wesley diverted attention to an Inland Mission -‐ to the ‘Foulah’ north of Freetown. The motives for this are not clear. One might speculate about the influence on the preference of the short life expectancy of Europeans on the coast, of the tensions between Methodists and Moravians and of Wesley’s knowledge of people from different parts of Africa. The Moravians had noted Miss Johnson’s commitment, and their committee records record that ‘Miss Johnson wishes that a mission unto those parts might still [be tried].’ Johnson kept her word, and, when she died (in 1798), she left £500 to the Mission to Calabar (I do not know what happened to that money). There is correspondence between Lace and an Ephraim, who may be the Prince we have been following, and who may be proving, when head of the trading family, the useful contact Norris had hoped. The letter to Liverpool (reproduced below) indicates that Ephraim is trafficking in human beings, selling stolen human beings at two guns a head.

59

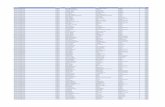

Letter sent by Ambrose Lace to Thomas Jones, November 11, 1773, replying to enquiries about Ephraim Robin John.

" wherein you desire I will send an Affidavit Concerning the two blackmen you mention, Little Epm (Ephraim Robin John) & Ancoy, in what manner the ware taken off the Coast &

that I know them to be Brothers to Grandy Epm. Robin John (aka Grandy George). … never found that little Epm. was one of Old Robin's Sons, and as to Rob. Rob. John he was not Old Rob. John's Son. Old Robin took Rob. Rob. Jno's mother for a wife when Robin Rob. Jno. was a boy of 6 or eight...You know the custom of that place what ever Man or Woman goes to live in any family the take the Name of the first man in the family...As to what Ship they came off the Coast in I know no more then you...As to Grandy Epm. you know very well has been Guilty of

60

so many bad Actions no man can say any thing in his favour, a History of his life would exceed any of our Pirates...I brought young Epm. home … He cost me above Sixty pounds and when his Fathers gone I hope the Son will be a good man."

Picture and transcript from http://stampauctionnetwork.com/f/f12145.cfm

61

Below is a transcription of one of the letters the Robin Johns wrote to Charles Wesley. It gives an account of the wreck of The Maria, the ship fitted out by Thomas Jones and captained by the troubled William Floyd. In the register The Maria is described as having been lost because of ‘natural hazards’ but the account below suggests human error might have been the cause. To Rev’d Mr. Chars Westley London for himself particularly 1774 Dear Sir The following being our opinion of Capt conduct must beg you’ll let nobody be acquainted with – We had a fair wind from the time we left Bristol, & were in hope of soon being at home, when thro the Wickedness and Drunkenness of the Capt., the Ship was lost, at the Island Bonavista, we made the land, about 4 oclock in the afternoon, & had time enough to avoid it, but the Capt who was very Drunk, would not take the advice of his officers to alter his course, but still kept on the same, running on shore, as if on purpose, he behave very bad to his officers, and People, all the time after leaving Bristol, he Beat his Chief Mate when we was out no more than one week for nothing at all, He was always Drunk, and never in his Senses. We again desire you to let nobody know it as it may hurt the Interest of our friend Thomas Jones. Ephraim Robin John Ancona Robin Robin John

63

"Captain Lace I take this opportunity to write you...That Letter you send me by Sharp you did not put your name...As for Captain Sharp I will do anything lys in my power to obliged you when Captain Cooper Comes let him guns enough I want 2 gun for every slave I sell and father we Don't want Iron only 2 for one slave. So no more at presant from your firend."

Sources for this exhibition or linked to pages in this document Page 8 et passim. Charles Wesley’s Letter to William Peronnet Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, 17 (1929-‐30). Page 11 Pictures , James Gibbs Collection.

Page 14 ff Transcription of Letters by Randy J Sparks. The Calabar Princes. Pictures https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/516928863452281146/ Website for Bristol: Portcities

http://discoveringbristol.org.uk/slavery/after-‐slavery/bristol-‐in-‐black-‐and-‐white/african-‐caribbean-‐bristol/18th-‐century-‐other-‐records/

http://discoveringbristol.org.uk/browse/slavery/moravian-‐chapel/

Books: Dresser, Madge. Slavery Obscured: The Social History of the SAlave Trade in and English provincial Port. London: Continuum, 2001. Mason, JCS The Moravian Church and the Missionary Awakening in England, 1760-‐1800. Oxford: Boydell and Brewer, 2001. Sparks, Randy J. The Calabar Princes: An Eighteenth Century Atlantic Odyssey, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard UP, 2004.

64

Williams, Gomer. History of the Liverpool Privateers And Letters Of Marque with An Account Of The Liverpool Slave Trade London: William Heinemann; and Liverpool: Edward Howell, 1897

Mason, JCS The Moravian Church and the Missionary Awakening in England, 1760-‐1800. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, RHS Publication, 2001.

On line and other sources http://www.bbc.co.uk/legacies/immig_emig/england/bristol/article_2.shtml Records of the Moravian Church at Bristol (Maudlin Street) University of Bristol special-‐[email protected] www.bris.ac.uk/is/services/specialcollections

Maps and engravings, Collection of James Gibbs

001 Three who went home exhibition on New Room/ Africa links/ West African Original prepared for John Wesley’s Chapel the New Room, Bristol, 2015.