Tratadooos Karen

Transcript of Tratadooos Karen

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

1/35

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

2/35

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

3/35

Hel

ece):

prab

rts tositualm of

laboicallyes of

n th een an

years,Law

con

g th ebeing

Code

soverxibility

indi

f New

inter

at faceoals ofterpre

ered todefine,t ia tiOll

Whereas

s are ofthose

. . . are

ling tos some \ (.te rela

he SJ mea trea tyeement

to th ederlying

nationalsociatedsequent

alteration, when there has b e ~ n a lapse of time or achange in State practice regarding the application of thatterm. Th e nineteenth-century legal writer, RobertPhillimore, thus cauti oned that "due construction of theinstrument may require a [kJnowledge of the antiquatedas well as the present use of the words . . . ." 10

States generally prefer less specific agreements than

do private international traders, in order to retain maximum flexibility in their respective dealings. Universityof Helsinki Professor Ja n Klabbers comments that many"formal and visible agreements make it politically difficult for states to change their policies. The necessity ofsending proposed agreements through cumbersomeprocedures of approval in their national legislaturesreduces states' freedom of action. Further, agreementsallowing for quick renegotiation or modification are bydefinition no t as inflexible as agreements which do no tmake [such an] allowance. Finally, agreement can bereached more swiftly . . . the more informal the proposed

instrument is considered to be."l1 One should acknowledge that the twentieth-century "public treaty as privatecontract" analogy is no t without its critics. A lawyer in atreaty-drafting process may prefer to "cross all the t's." Apolitical scientist might focus on th e relationshipbetween the four corners of the document. A diplomatmust view the process through both lenses.

"Unequal" Treaties International agreements aresupposedly the product of a mutually beneficial decisionto create rights and honor obligations. Unfortunately, anumber of treaties have been imposed by on e State onanother because of their inherently unequal bargainingpositions.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, writers first raised the question of whether treaties were validin the absence of any real bargaining or negotiations. In1646, the famous Dutch author Hugo Grotius distinguished between equal and Ul1equal treaties. He describedan unequal treaty as one that is forced on one nation byanother, rather than being the product of a negotiatedprocess. In 1758, Swiss author E. de Vatte! examined theproblem of unequal treaties-concluding that States, likeindividuals, should deal fairly wirh on e another. De Vattelhypothesized that because States "are no less bound thanindividuals to respect justice, they should make theirtreaties equal, as far as possible." Nei the r of rhese influential writers, however, questioned the legal validity of suchtreaties. A bargained-for exchange was not considered a

TREATY SYSTEM 3 5 7

necessary prerequisite for a valid treaty between sovereignStates. Bu t as later stated by American author H. Halleckin 1861, "the inequality in the . . . engagements of a treatydoes not, in general, render such engagements any the lessbinding upon the contracting parties."12

Examples of unequal treaties include Napoleon's 1807threat to place the king of Spain on trial for treason,

unless the king surrendered his throne. Having nochoice, King Ferdinand entered into an agreement withFrance that was devoid of any bargained-for advantagesfor Spain. In the 1856 Treaty of ~ a r i s , Russia was prohibited from maintaining a naval fleet on the Black Seaat its geographically sensitive southwestern border. In1903, a US condition for recognizing Cuba's independence from Spain was the Guantanamo Naval Base Treaty.Th e United States thereby "acquir ed" a permanent leasefor a military base that proved critical to US interests.Th e 1903 Panama Canal Treaty wi th Colombia validatedUS control over the Canal (until relinquished in 1977).

Th e Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, wassigned by German delegates wh o had unsuccessfullyobjected to draconian terms requiring that Germany paythe victors for damages incurred during World War 1. Justprior to World War II , Hitler threatened to bombCzechoslovakia to force the adoption of a treaty placingthe Czechs under German "protection.''!}

In th e twentieth century, legal commentators beganto question the historical presumption that unequaltreaties are valid. National Chengchi University (Taipei)Professor Hungdah Chiu summarized them as follows:

After th e 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia, theBolshevik government offered to abolish and laterdid abolish some former Tzarist treaties imposedupon China, Persia, and Turkey; and Soviet writersthen began to discuss the question of th e validity ofthose "coercive, predatory, and enslaving" treaties,although the term "unequal treaties" was no t wide!yused after World War II. This early development inthe Soviet Union, however, was generally ignored byWestern scholars.

In the 1920s, however, ~ e problem of unequaltreaties received world-wide attention when Chinademanded the abolition of some treaties that it termedunequal. Only then did some Western writers renewinterest in the problem. In 1927, at the annual meetingof the American Society of International Law, a sessionwas devoted to the discussion of China's unequal

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

4/35

3 5 8 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LA W

treaties. With the abolition of what were presmned tobe the last of China's unequal treaties in the early 1940s,Western scholars again lost interest in the subject.

With the emergence of many new states in Asiaand Africa in the 1960s, the question of unequaltreaties again began to attract worldwide attention.When the Draft Articles on the Law of Treaties pre

pared by the United Nations International Law Commission was sent to UN member states for comment,many states expressed concern about the question ofunequal treaties. 14

CONTEMPORARY CLASSIFICATION

Th e convenience of any treaty classification system isrivaled by the c!

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

5/35

elated1987

ArabiaSaudi

ument ~ t e r s forThese

whichsf those

t theirurt. l6

treaty

en twOothers.

es fromf treaty

ute to

aw. Fo radition

which

to th e

tates dopractice,

subject

r createss intent

ral treatybe evi

thin th enal La wn , is anr e States.orgal1lzaultilaterals of th eparticular

ultilateralhe impacthe Sea, for

ssor Louisd War n:

epted th eforce such

This flexibility is due_primarily to th e tremendous increase in th e last fifty years in the role beingplayed by international institutions and multipartitediplomacy. Originally, evidence of the existence of arule of international law could be found only inbooks written by eminent professors or in briefSprepared by practitioners in disputes involving inter

national law. . . . Th e Hague Peace Conferences of1899 an d 1907 inaugurated a new approach: th econtracting parties, acting on behalf of "the societyof civilized nations," agreed on a number of lawmaking conventions . . . [regarding] "the principlesof equity and right on which are based the securityof States and the welfare of peoples . . . an d the dictates of public conscience."

During the period of the League of Nations,while th e 1930 Codification Conference [on treatypractice] did no t prove successful, the number ofmultipartite treaties increased considerably. ProfessorManley 0 . Hudson collected in the first eight volumes of International Legislation, covering theperiod 1918 to 1941,610 international multipartitetreaties of that period. Since the Second World War,the United Nations, acting no t only through theInternational Law Commission, bu t also through itsspecialized agencies an d special conferences . . .together with the increasing number of regionalorganizations and various groups of states dealingwith specific topics of international law, has givenbirth to several thousands of multipartite agreementscovering practically every conceivable subject [morethan 33,000 when this article was written].18

Lawmaking versus Contrac:tual Treaties may alsobe classified as either "lawmaking" or "contractuaL" Alawmaking treaty creates a new rule of InternationalLaw designed to modify existing State practice. The1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Treaty contains anumber of ne w rules governing jurisdiction over theoceans. Although it codifies (restates) some p'reviouslyexisting rules that States applied in their mutual relations, this multilateral treaty also contains some novel

lawmaking provisions. Fo r example, th e new International Seabed Authority was created to control the waysin which the ocean's resources are globally (re)distributed. Free "transit passage" 'vvould replace the otherwiseapplicable regime of restricted "innocent passage"through the territorial waters of coastal States (6.3).

TREATY SYSTEM 35 9

Ratification of some of th e associated provisionswould change State practice, which ha d no t previouslyrequired either an equitable redistribution of globalresou rces or transit passage.

On the other hand, some treaties are merely "contractual." An import-export treaty sets forth the terms ofa contract, which the State parties agree to for a speci

fied period of time. For example, under the GATT /W TO regime (13.2), State X agrees to charge an 8percent tariff on incoming State Y wine . State Y mayexport up to 100,000 bottles of wine per year to StateX. This arrangement is a simple contract. It does no tpurport to create, alter, or abrogate any of th e norms,which govern international trade.

French Professor Paul Reuter, in his distinguishedtreatise on treaty law, succinctly recounted that "[t]hedevelopment of treaties dunng the second half of thenineteenth century prompted several new doctrinal distinctions . . . . [T]he expressions 'law-making treaties' and'contractual treaties' came into use, the former referringto the treaties [that] first laid down general conventionalrules governing [all of ] international society . . . . It isimportant to make clear, when speaking of treaties aseither [normative] 'legislation' or [mere] 'contracts,'whether they are being viewed fi'om [either] a legal orsociological standpoint." 19

An entire treaty, or parts of it, may break new legalground. The North American Free Trade Agreement(NAFTA) associated Canada, Mexico, an d the UnitedStates into a large free-trade area. That development was"lawmaking" because it created a ne w internationalorganization.Yet there was nothing novel or lawmakingabout their reduction of trade barriers to form acommon economic market. Many other countries, as inthe European Union, had already done so. In this sense,NAFTA merely created an international contract governing the respective goods and services exchangeamong the State parties, just like a private contractwould do, between three merchants engaged in a similar cross-border transaction. One could distinguish the1995 World Trade Organization (WTO), however. Itreplaced th e established 1947 General Agreement on

Tariffs and Trade (GATT) process. The physical bulk ofthe W TO process merely continued the GATT processof publishing national tariff schedules. But establishingan authoritative W TO process involved fresh lawmaking, because of the way in which nations therein

decided to resolve their international trade disputes.

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

6/35

3 6 0 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LAW

Self-Executing versus Decla ra t ion o f In ten t A

treaty may be further classified as "self-executing" whenit expressly imposes immediate obligations. A selfexecuting treaty requires no further action to imposebinding obligations on its signatories. It is instantly incorporated into both International Law and the internallaw of each treaty member by the express terms of the

treaty There is no need for additional executive or legisla_--... / - - . - - .tive a ~ t i o n .by the State parties to immediately createb I ~ d i n g kgal obligations. Alternatively, a treaty may be a'-----"" . ------=. ..declaration of intent:" It would thereby contain generalstatements of principle, which set forth a hortatory standard of achieveme nt for all parties. Such treaties requirefollow up, individual State action before any of the parties incur actual legal-as opposed to moral-obligationsunder the treaty.

Bilateral treaties concluded by two States are normally self-executing. Th e contracting States would haveno treaty, if they were unable to agree to all of its terms.

No t so with a multilateral treaty. Most multilateral treatiesareJl.ot s e l f - e ~ u t i n g . Th e State draTrerswllo sign themintend them to b?s"tatements of principle, which do no timpose immediate legal obligations to act in a particularway. Such treaties are intended to articulate mutuallyagreeable goals or standards of achievement. Each participant must undertake some subsequent act under itsinternal law, for the stated standard to then ripen into abinding legal obligation.

If all treaties were self-executing, few States wouldparticipate. There is a vast difference in economic, cultural, political, or military capabilities to immediatelyinstitute all features of certain multilateral treaties. Aninitial agreement on the aspirational goal accommodatesthese differences via the expression of conunonly understood objectives. As acknowledged by U N SecretaryGeneral Ko1 Annan, in his Millennium Summit invitation for nations of the world to ratifY the twenty-fivecore multilateral treaties:

Since the founding of the United Nations in1945, over 500 multilateral treaties have beendeposited with the Secretary General. . . . Withoutexception, all of these treaties have been the result ofmeticulous negotiations and reflect a careful balance ofnational, regional, economic and other interests . . . .Th e aspirations of nations and of individuals for abetter world governed by clear and predictable rulesagreed upon at th e internati onal level are reflected inthese instruments. They constitute a comprehensive

international legal framework covering the wholespectrum of human activity, including human rights,humanitarian affairs, the environment, disarmament,international criminal matters, narcotics, outer space,trade, commodities and transportation . . . .

Some of these multilateral treaties, though negotiated many years ago, are still to receive the minimum

number of ratifications and accessions required fortheir entry into force. Others are still far from achieving universal participation. It is my hope that Headsof State a.nd Government will . . . rededicate themselves to the multilateral treaty framework and therebycontribute to advancing the international rule of lawand the cause of peace . . . . 20

Th e following case arose in the no w familiar contextof the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. In the7.2 Torres case, you observed the sensitive fallout fromfailure to provide consular access to an arrested foreign

national. In a related case, the US Supreme Court analyzed whether that treaty is self-executing:

Medellin v, Dretke

SUPREME C O U RT OF TH E

U NITED STATES

_ U.S. _ , 125 S.Ct. 2088, 161 L E d . 2d982(2005)

Go to course Web page at.

Under Chapter Eight, click Medellin v. Dretke.

8.2 FORMATION, PERFORMANCE,C E SSATION

T his section of the book deals with the treaty process:how a treaty is formed, expectations regarding its performance, and when performance may be interrupted.Although this section focuses on the main internationaltreaty on treaties, local procedures for adopting it vary fromcountry to country. As noted by the Council of Europe:"Treaty-making constitutes the very basis of the international legal order and influences international relations.

It chanbound

Howeviexpressdependitions w

TREATY

Th e chrmentatictu re, ratian d regis

Negot ia

often beU N Genof globalproblemference.5t

with pre1conferencfor examItreaty. Th eo f the nexnegotiatedth e oceansdrafted, anproduced;

least in priConfere

to negotiajcdiplomatsauthorities,with "futi f

ment fromor conferen.ence. Thatwith variowperform anyof the treatytates assuraracceptable te

decide whetnegotiated b

Th e lacktional relatiosigned two lauthority to (minister imp

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

7/35

hole

ghts,1ent,pace,

goti-

mum

r e d fo rhiev-

eads

hem-

erebyf law

ntext

n th efrom

reignana-

nl> .

E,

rocess:

its per-upted.ationaly fromurope:

nterna-

ations.

It channels t he expression by _States. of consent to bebound and defines the commitments (hey enter into.However, the national procedures by which Statesexpress their consent to be bound vary considerably,depending on constitutional, legal an d political condi-tions which reflect the history of each country."21

TREATY FORMATION

The chronological phases in the formation and imple-mentation of a multilateral treaty are negotiation, signa-ture, ratification, reservations (i f any), entry into force,and registration.

N e g o t i a t i o n s Th e emergence of a multilateral treatyoften begins when an international organ such as theUN General Assembly decides to study some problemof global concern. Th e Assembly might resolve that theproblem should be the subject of an international con-ference. State representatives commence the treaty process

with preliminary negotiations during an internationalconference. Most nations of the world first me t in 1974,for example, to draft an International Law of the Seatreaty. These initial discussions ex panded, over the c ourseof the next eight years, during which many nations thusnegotiated their respective positions on proper use ofthe oceans an d its natural resources. These representativesdrafted, and redrafted, a "constitution" of the oceans. Theyproduced a f111al treaty text, which was satisfactory, atleast in principle, to the participants (6.3).

Conference representatives must possess the authorityto negotiaJe .onbehalf of their respective ~ ~ s . No t unlikediplomats wh o present their credentials to host Stateauthorities, conference participants are normally vestedwith "full powers" by the State they represent. A docu-ment from each State's government is presented to a chairor conference comm..ittee at the inception of the confer-ence. That document normally vests the representativewith various powers: to negotiate, provisionally accept, orperform any act necessary for completing tlus initial phaseof the treaty process. Th e "full power" instrument facili-tates assurances that conference developments will beacceptable to the governments that will one day have todecide whether to ratify the fmal draft of the treaty textnegotiated by their respective conference representatives.

Th e lack of such authority adversely affected interna-tional relations when a former US minister to Romaniasigned two bilateral treaties, but without the president'sauthority to do so. Regarding one of those treaties, the USm..inister improperly advised the president that he was

TREATY SYSTEM 36 1

signing a different treaty than the one he actually signedwith Romania. As to the other agreement, he had noauthority whatsoever to actually bind the United States.Th e US attempt to avoid its obligations under thosetreaties was resisted by Romania because the United Stateshad already officially entered into these two agreements. 22

To help clarif)l treaty expectations in such instances,

Article 8 of the VCLT provides that any "act relating to theconclusion of a treaty performed by a person wh o cannotbe considered . . . as authorized to represent a State forthat purpose is without legal effect unless afterwards con-firmed by the competent authority of the State." Thislanguage theoretically creates the potential for abuse,whereby a State representative can enter into a treaty, andthe home State can subsequently disavow the aut hority ofits representative. In practice, however, the representative'spresentation of documentary powers at the inception of aconference contains clear notification to all participantsabout the extent of a particular delegate's powers (which

may be limited by the dispatching government).In the 1960s, many of the neW nations an d former

colon..ies in Africa and Asia advocated the proposition that(the previously discussed) "unequal treaties" were nolonger acceptable under International Law. One promi-nent forum for advocating this perspective was the draft-ing negotiations for the 1969VCLT.Ar ticle 2.4 of the U NCharter requires all members to "refrain in their interna-tional relations from the threat or use of force . . . [whichis] inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations."If force was illegal in international relations, then coercionin the treaty process should invalidate the legality of anytreaty forced upon these former colonies whose bargain-ing power was no match for their former occupiers.

Th e result of the VCLT negotiations was the incorpo-ration of two articles applicable to treaties concluded afterthe effective date oftheVCLT (January 27, 1980). Article51 provides that the" expression of a State's consent to bebound by a treaty which has been procured by the coercion (ifits representative throug h acts or threats directed against hi mshall be without any legal effect" (italics added). Article 52provides that a "treaty is void if its conclusio n has been pro-wred by the threat or use ojJorce in violation of the principlesof international law embodie d in the Charter of the Un..itedNations" (italics added). Although coerced treaties thatconcluded prior to the VCLT were presumed valid bysome writers, Articles 51 and 52 expressly negated thatpresumpt ion for subsequent rreaties. As stated by the IC],there "can be little doubt, as is implied in the Charter of

the United Narions and recognized in Article 52 of the

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

8/35

3 6 2 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LA W

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, t h ~ t _ undercontemporary international law an agreement concludedunder the threat or use of force is void."23

During the VCLT negotiations, a number of Easterncommunist bloc and African states advocated the viewthat Article 52's prohibition against force should expresslyinclude "economic, military, and political" coercion. Their

attempts to ban treaties procured through these categoriesof force were rebuffed by Western representatives. Th eWestern position was that, given the difficulty of defming"force" in the treaty process, it would be too difficult todetermine whether a treaty was invalid because it wasallegedly signed as a result of such duress.

Article 52 of the VCLT therefore does no t contain aspecific definition of force. Instead, it generally prohibitsthe threat or use of force in violation of the principlesof International Law embodied in the U N Charter. Thatlanguage thus meant that "the precise scope of the acts

covered by this defl11ition should be left to be deter

mined in practice by interpretation of the relevant provisions of th e [UN] Charter." Yet Article 2. 4 of the

Charter also begs the question of what is the intendedmeaning of ' he term "force." It vaguely prohibits th e useof force "against th e territorial integrity or politicalindependence of any state . . . ."The Vienna ConventionArticle 52 definition of force in the treaty process waslikewise left purposefully vague, because it incorporatedthe Charter's inherently vague definition of force 24

Some ambiguity about the scope of the term "force"was oiliet at the conclusion of the VCLT. The delegatesadopted the separate Declaration on the Prohibition of

Military, Political, or Economic Coercion in the Conclu

sion of Treaties. They therein stated that the UnitedNations Conference on the Law of Treaties "solemnlycondeillils the threat or use of pressure in any form,whether military, political, or economic, by any State inorder to coerce another State to perform any act relatingto the conclusion of a treaty in violation of the principlesof the sovereign equality of States and freedom of consent. . . ."25 This Declaration was actually made independently of the VCLT rather than directly expressed withinthe text of the Article 52 prohibition of force in the conclusion of treaties. This exclusion-which more preciselydefined force, bu t in the supplemental text no t officiaUy apart of the VCLT i tself-was a compromise. It amelio

rated Western opposition to nonmilitary duress as a basisfor invalidating a treaty. Because the VCLT itself definescoercion only by the reference to the "principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United

Nations," it is difficult to determine when a [Ieaty wouldbe void on the basis of duress in its creation.

Signature Th e next significant step in the treaty processis "opening for signature." States, and any participatinginternational organizations, are invited to sign (which is

distinct from subsequent ratification). A State that signs a

treaty has agreed, in principle, to the general wording ofthe articles appearing in the text of its final draft. Drawingupon the example of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (7.2), negotiations were concluded in1969. Th e representatives had thereby finished drafting thisnew "constitution" governing diplomatic issues.

In on e sense, this was only the beginning. UnderArticle 81 of the VCLT, "[1']he present Convention shallbe open for signature by all States Members of theUnited Nations . . . and by any other State invited bythe General Assembly to become a party to the Convention . . ." States that did no t participate in the draft

ing conference may subsequently "accede" to a treaty.That State thereby consents to be b o ~ - : - a l b e i t in principle, like any States that signed th e treaty at or near theconclusion of the drafting conference. Alternatively,accession may express a State's willingness to accept thetreaty's obligations as being immediately binding, withou t the necessity of ratification (discussed below).

Unanimous and inm1ediate consent of aU States is possible, but quite atypical-for reasons addressed m the"reservations" portion of this section. Fully embracing thetreaty's commitments normally evolves through two

related stages. Th e first stage is proIJisional acceptance

of the treaty by the conference delegates. This stageexpresses consent to the general wording of the final conference draft. Unless otherwise specified, the signature ofa representative on a multilateral treaty merely indicatesthat his or he r State agrees in principle with the essenceof the treaty. Final acceptance would follow, >vhen a Stateexpresses its willingness to be legally bound by the treaty'sterms, expressed in that State's ratification of the treaty.

Ratification Postconference ratification is th e typicalmode for each State's full acceptance of a treaty. Theconference delegate has already submitted the provisionally accepted treaty text to the proper authority illhis or he r State for final approval. This ratification is

then determined in accordance with each State's internal laws on treaty acceptance. Oxford University's SirHumphrey Waldock provides a useful explanation forthe necessity of postcon.ference ratification by each potential

State par

ar e otten:

that an O

should be

opinion, ations, whi,

As cla

AppealsI nternatic

The raserves s

state tha compfor an ifor vari0J.;tug J i : - 5 p : r i T I ~ h e r m e n might be permitted to fish in Portugal's area of the high seas, because of the treaty'sm ~ g r e e d purpose of e ~ i t a b l e d i s t r i b u r ~ o n .Th esame fishing treaty would be terminated under theimpossibility doctrine, if all of the fIsh were permanentlydriven away by contamination 0 t ~ treat):' area. hetreaty wo u d o e meaningless because the object of thatagreement would no longer exist 51

Confl ict w i t h Peremptory Norm A treaty is void if

it conflicts with a peremptory n0l"l1l of InternationalLaw. The common descriptive term for such a norm is

pending or terminating its obligations. Article 61 of the J'UScogens, referring to a supposed universally acknowl-VCLT provides that impossibility "results from the permanent disappearance or e s r r u c ~ o n oran ..2. - ~ _ e _ c t j n d i s -

pensab e or t e execution 0'the treaty."The drafters ofthe VC L usea t 1e following examples: submergence ofan island that is the object of a treaty relationship, th edrying up of a river, and the destruction of a dam. orhyd!:,:oe e c t r ~ l i t i o n indispensable for the e x e c u ~ i o n

of a treaty. The permanent or temporary impact of suchClrcums ces would terminate (or suspend) righrs and

49obligations arising under a treaty governing their useA fundamental change that radically alters the nature

of treaty obligations has been characterized by somejurists as impossibility of performance-presenting a fine-line distinction from the above "changed circumstances"

edged law from which no State could deviate. Article 53of the Vienna Convention on th e Law of Treaties definesrhat term as a norm which is "accepted and recognizedby the international community of States as a whole as anorm from which no derogarion is permitted and whichca n be modified only by a subsequent norm of generalinternational law having the same character." However,the VCLT does nor provide examples of what constitutessuch a nOrm.

The International Law Commission's july, 2001 Articles on State Responsibility provide no substantive cluesregarding which norms fall within this category. Article26 states only that "Nothing in this Chapter precludesthe wrongfulness of any act of a State which is no t in

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

22/35

374 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LAVV

conformity with an obligation arising under a peremptory norm of general mternationallaw." Article 40 follows

with "the international responsibility which is entailed by

a serious breach by a State of an obligation arising undera peremptory norm of general international law.

[which] IS serious if it involves a gross or systematic fail-ure by the responsible State to fulfil the obligation."

Some jurists and cOlllmentators deny the functionalexistence of jlls cogens, because even the most generallyaccepted rules have no t achieved unIversality. Moscow

State University's Professor Grigori Tunkin explains that

the "arguments of opponents of .IllS cogens ca n bereduced to the fact that such principles are possible only

in a well-organized and effective legal system, and sincell1ternational law is no t such a system, the existence of

principles o f general international law having the character of jus cogens is impossible."5:!

On e can make a reasonable theoretical argument that

applying .IrIs cogens (assuming that it actually exists)

'vvould render c e r t ~ l i n tre:Jties void. When tw o Stateshave entered into a treaty' in which they agree to invade

another country, t h a ~ ~ ~ i ~ l ~ s-.:..he most fundamental UN Char t e l arti.cle: Article 2.4's prohibition

on e use o f force in international relations. Such a

treaty would violate an undisputable Charter norm.

Today, Stalin an d Hitler's then secret 1939 agreement to

divide Europe could no t legitintately circuntvent th e

Article 2.4 prohibition of force.

VCLT Appl ied In 1997, th e ICJ adjudicated the fol-lowing dispute between Hungary and Slovakia. Hungary

relied on the VCLT's provisions discussed 111 this sectionof the book-as its rationale for terminating its 1977Budapest Treaty with (what was then) Czechoslovakia.

Case Concerning th e

Gabdkovo-Nagymaros Project(Hungary v. Slovakia)

[ N T E R N AT I O N A L C O U RT OF JUSTICE (1997)

Gen. List No . 92

Go to course Web page at.

Under Chapter Eight, click Hungary/Slovakia Treaty

Breach Case.

Limi ta t ions Suspension or termination is subject to

other restrains. The severance o f diplomatic or consular

rebtions does not necessarily affect treaty rights an dobligations. Article 2. 3 of the Vienna Convention on

Consular R.eldtions (VCCR) provides that the "severance of diplomatic re!Jtions shall no t ipso factO rautomatically in an d o f Itself] ll1volve th e severance o f

collsular relations" (italics added). Article 45 of th eV C C R expressly provides that a break in diplomaticrelations does IIOt alter th e continuing obligation to

honor treaty obligations having nothing to do with

diplomatic or consular matters. Therefore, wa r an d

other hostile relationships do not terminate all treatyobligations o f parties to th e conflict. States are expected

to continue to perform their obligations under treatieslike the Geneva Conventions of 1949 dealing with R.ed

Cross assistance, th e laws of war, an d treatment of prisoners o f wa r (10.6).

Theory an d practice, however, often diverge when

nations are at war. The outbreak of war does no t automatically terminate treaty obligations. The US wa r withGermany did no t automatiG1Lly terminate th e 1923 UStreaty obligation to transmit property of deceased Il1di-

viduals to German citizens 53 A prolonged state o f wa r

often presents problems with the performance o f treatyrequirements, an d continuing these obligations may makeno sense.

8. 3 UNITED STATESTREATY PRACTICE

U nder International Law, there are tw o g e n e r ~ d principles for resolving conflicting Jaws. One is that theUN Charter prevails when it conflicts with anotherinternational instruI11ent. 54 The other is that a nation'sinternal law cannot be used as a defense to its breach of

an international obligation.Ho w various nations make treaties is beyond the intro

ductory scope of this book. Suffice it to say that the rangeof practice in cludes "legislative" and "executive" treaties. 55

TREATY VERSUS EXECUTIVE AGREEMENT

On e must begin with three essential components o f UStreaty practice. The first is the constitutional articulationo f the president's treaty power. Under Art. [I , Section 2,

clause 2:"He shaU have Power, by an d with rheAdfJicc alldCOIlSCi!t of the Smote, to make Treaties, provided that twothirds of the Senators present concur . . . [italics added]."

Sec

cOnstitsimultaagree

nationsunder

by the]

o f th eTh e

treaties

statutes

spli ts Iemakes aca n use

some ccertain

bel'S of

sued PrEo f the P;

Constit

shall hav

the Uni

the H o

Constitu

th e "A d

seeking

o f Cong

T h e "

was spaw

tional Co

was ultinrole, whi,

with the:

matte r, ththat diplc

possible cS L ~ _ S ~ l

of this de

what rerr

excludingdent as th

Almosthe conseagreemen

US Co n

"treaties."

ent ysaw

known ir

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

23/35

toular

an d

on

ver

uto

e ofth e

maticn towith

andreatycted

atiesRed

pris

when

autowith

3 USindi

f wa r

treatymake

prin

at th eother

tion's

ach of

11trorange

ties 5S

of US

lationon 2,

ice alliiat tw oded] ,"

Second, there is an oceanic distinction between theconstitutionally articulated "treaty" power and the nearlysimultaneous appearance of th e president's "executiveagreement" power. All presidential agreements with othernations or international organizations are treaties. Bu tunder US practice, executive agreements are undertakenby the president alone--without the advice and consentof the Senate,

Th e third major theme is the relative ranking oftreaties (either type), the US Constitution, and federalstatutes when any of them conflict. The debate sometimessplits legal hairs regarding whether the president-whomakes aU treaties, with or without the Senate's consen tcan use the executive's treaty-making power to trumpsome constitutionally required legislative involvement incertain foreign affairs. In 1977, for example, sixty members of the US House of Representatives unsuccessfullysued President Carter when he relinquished US controlof the Panama Canal. Article IV, Section 3, clause 2 of the

Constitution provides that the "Congress [both houses]shall have Power to dispose of . . . Property belonging tothe United States . . . . In the view of these members ofthe House, President Carter had improperly relied on theConstitution's Treaty Power when' he successfully soughtthe "Advice and Consent of the Senate"-rather thanseeking th e Canal's transfer to Panama via both housesof Congress.

Th e "treaty" versus "executive agreement" distinctionwas spawned by early US practice. During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the House of Representatives

was ultimately excluded from an express treaty-makingrole, which would have been exercised in conjunctionwith the Senate, as originally proposed. After debating thematter, the delegates acknowledged the widespread feelingthat diplomatic negotiations required a decrree o f secrecypossible onJy in the smaller senatorial body (then twentys i ~ ' S " f i : O J 1 2 . ~ t h eJ12ir:.te.fri-fciri11er colon ies). Th e fervorof this debate etfectively overshadowed the importance ofwhat remained in the final draft of the Const i tu t ionexcluding the House completely, and inc luding' the president as the constitutional maker of US treaties 56

Almost immediately, US presidents, without seekingthe consent of th e Senate, began to enter mt o "executiveagreements." This contrast evolved, in part, because theUS Constitution does no t actually define the term"treaties."When it was adopted in 1787, its drafters apparently sa w no need to define a concept that was then wellknown in international practice S7 The Treaty Clause has

TREATY SYSTEM 3 7 5

never beenjudiciaJJy interpreted by the judicial branch ofthe US government- to mean that the president musthave th e Senate's advice and consent for aU internationalagreements.

Two types of "executive agreements" evolved. On e isthe congressional-executive agreement. Th e president alsorequests approval of certain executive agreements by jointresolution of both houses of Congress. Columbia University Professor, Louis Henkin presents the following vindication for 'this implied presidential power: "NeitherCongresses, no r Presidents, no r courts, have been seriouslytroubled by these conceptual difficulties and differences.Whatever their theoretical merits, it is no w widelyaccepted that the Congressional-Executive agreement isavailable for wide use . . . and is a complete alternative to atreaty: Th e President can seek approval of any agreementby joinuesolution o f 1 3 . P f 1 1 l 1 0 u ~ s - o fCongress rather thanby QVo-thirds of the S e n ~ t e . Like a treaty, such an agreement is the law of the land, superseding inconsistent state

laws, as well as inconsistent provisions in earlier treaties, inother international agreements, or 111 acts of Congress."S8

The other category of'executive agreement is th e" s o l ~ I - I J i v e agreement." While congressional approvalfor executive agreements is often sought, it has beencompletely avoided in some instances. Th e presidenthas exercised the inherent power to incur an international obligation independently of the Senate (ArticleII treaty) or both houses of Congress (congressionalexecutive agreement). Columbia University ProfessorOliver Lissitzyn succinctly describes th e historical bu t

troubled development of th e president's executiveagreement power:

Th e making of executive agreement s is a constitutionalusage of long standing [that] apparently rests upon thePresident's vast bu t ill-defined powers in the fields offoreign relations and national defense. Neither theusage no r the decisions of courts, however, provideclear-cut guidance as to the scope of the treaty-makingpower and the scope of the executive agreementmaking power [which] are no t mutually exclusive.What may be properly accomplished by executiveagreement may also be accomplished by treaty. . . .

It is no t believed that any attempt to delimitrigidly the scope of th e executive agreemen t-ma kingpower is likely to be successful or to result in a correct portrayal or prediction of actual practice. Somewriters, while refusing to regard th e executive

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

24/35

3 7 6 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LA W

agreement-making power as co-extensive with thetreaty-making power, wisely refrain from attemptingto define the scope of the former. . . .

It may be proper, therefore, to regard the executiveagreement-making power as extending to all theoccasions on which an international agreement isbelieved by the Chief Executive to be necessary in

the national interest, bu t on which resort to thetreaty-making procedure is impracticable or likely torender ineffective an established national policy. Th etest here suggested is the only on e that adequatelyaccounts for the variety of situations in which thePresident, with or without the approval of Congress,has resorted to the executive-agreement procedure. Italso accounts for the increasing frequency of resort tothe executive-agreement method in recent years,with the growth of complexity in international affairsand of pressure of work in the Senate 59

No t all Commonwealth countries allow executiveagreements to have automatic effect as domestic law. Sucha treaty is binding under International Law standards.Under Australia's Constitution, however, an executiveagreement cannot have any internal effect until it isenabled into law via legislation.

Exhibit 8.1 illustrates the historical comparisonbetw een "treaties," in the constitutional sense of requiringthe Senate's advice and consent, and "executive agree

ments," undertaken as either the congressional or solevariations of that term. It is readily evident that the executive agreement has far surpassed the treaty in terms ofhow the president exercises the treaty-making power.

Th e Senate has occasionally expressed concern aboutthis spiraling use of executive agreements, which hasarguably emasculated its constitutional role in the treaty

making process. Th e most heated debate occurredbetween 1952 and 1957. Senator John Bricker generated an intense challenge by his proposed amendmentto the Constitution's Treaty Clause. He advocated thatall international agreements by the United States shouldbecome effective only when legislation passes in boththe House of Representatives and the Senate. If he hadbeen successful, the propos ed constitut ional amendmentwould have eliminated the president's ability to enterinto any international agreement vvithout express congressional approval. He or she would thus have beenmore of a negotiator than a 111aker of treaties.

Although the Bricker Amendment failed, Congressdid pass the Case Act in 1972. It requires the presidentto advise Congress (in writing) of all internationalagreements made without the consent of the Senateor without a joint resolution of Congress. Th e president may believe that public disclosure would prejudice national security, however. In this instance, he orshe may secretly enter into and later transmit a completed executive agreement to the Senate Committee

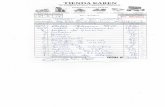

E X H I B I T 8. 1 ARTICLE II-TREATY EXECUTIVE AGREEMENT C OMPARISON

Treaties an d Executive Agreements Concluded by th e United States from 1789-2004

Period Treaties

1 7 8 9 - 1 8 3 9 60

1 839 -1 8 8 9 215

1 889 -1 9 3 9 524

1 939 -1 9 8 9 702

1 9 9 0 - 1 9 9 9 249

2 0 0 0 - 2 0 0 4 84

Total 1,834

Executive Agreements

27

238

917

11,698.

2,847

977

16,704

Treaty/Exec Agreements (Ofo)

69/31

47/53

36/64

6/94

8/92

8/92

10/90

Th e author's percentage calculations are expressed in l'Ounded numbers. Data on the period since 1945 has been furnished by the US Department ofState, Office of the Assistant Legal Adviser for Treary Affairs. Data prior to 1945 is from the Congressional Record, May 2,1945, at 4118 & E. Borchard,Treaties and Executive Agreements, 40 AMER. POL. SCIENCE R.EV. 735 (Aug. J947). This table was adapted from, and further detail is available at:< h t t p : / / f r w e b g a t e . a c c e s s . g p o . g o v / c g i - b i n / g e t d o c . c g i ' d b n a m e = 1 0 6 _ c o n ~ s e n a t e _ p r i n t & d o c i d = f : 6 6 9 2 2 . w a i s > . Th e more recent numerical comparisons were forwarded to rhe author by Jennifer Elsea, Legislative Atrorney, Congressiona.l R.esearch Service.

on Fo n

ForeignTh e

bu t notexeclltivPresidenwhich

basis f01Court c

AUTH

exeClI

pIlles.ipmopurpo:ees 011the 10

gWlIlginlowlthan

depencnation

Th r

anyel1

US Ovpermitl

nationaJowed,

citizen1971 1

these p

Senate'th e 197

In lnaval bjobs hac

to th etive agrthey W t

the USjobs at t

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

25/35

r soleexec-

ms of

er.about

h hasreaty

urredgener

ment

d thatshould

n bothhe ha d

dment

enter

s conbeen

ngress

sident

tional

Sena te

presi

preju

e, he orC0111-

mittee

nts (% )

ment of

orchard,

e at:om par-

on Foreign Relations and th e House Committee on

Foreign Affairs 6 0

The US Supreme Court has occasionally described,

bu t no t clearly defined, the scope of th e president's

executive agreement power. In a case growing ou t ofPresident Carter's 1979 executive agreement with [ r a n -

which ended the hostage crisis (7.4), an d provided a

basis for resolving business claims against I r an - theCourt characterized that general power as follows: "I n

TREATY SYSTEM 37 7

addition to congressional acquiescence in th e President'spower to settle [such] claims, prior CJses of this Courthave also recognized that th e President does have some

measure of power to enter into executive agreements

without obtaining th e advice an d consent of theSelldte."6l The following case illustrJtes th e difficulty in

drawing a precise legal demarcation between th e presi

dent's executive agreement po\ver and the Senate consent required under the US Constitution:

U1!inbel'gel' P. Rossi

SUPR-EME C )UR.T OF TH E U N I T E D STATES

45 6 U.S. 25,102 S.Ct. 1510,71 L. Ed. 2d 71 5 (1982)

AUTHOR'S NOTE: [n 1968, President Joh nson made anexecutive agreement with the Republic of the Philip

pines. It provided for the preferential employment of Filipino citizel15 at US military bases in the Philippines. Itspurpose was to ensure the availability of suitable employees on those bases, including individuals wh o could speakthe local language. Th e underlying rationale was thatgiving these jobs to local Filipino nationals would rcsultin lovvcr wage costs and less turnover in these positions,than if the same jobs were available to US militarydependents. Th e President thus decided to favor foreignnationals in the hiring process on these bases.

Three years later, Congress enacted a law prohibiti"ngany employment discrimination against US citizens on

US overseas military bases-unless a "treaty" expresslypermitted such discrimination as being necessary to USnational interests. Four more executive agreements followed, providing for preferelltial treatment of foreigncitizens ;I t overseas mjlitary bases-after passage of the1971 nondiscrill1i.!Iation legislation. However, none ofthese postlegislation agreem.ents were submitted to theSenate for its advice and consent, as argudbly required bythe 1971 law.

[n 1':178,several US citizens wo rkin g at Ol{e of the USnaval bases in the Philippines were notitled that theirjobs had been converted into "local" positions (pursuant

to the intentional discrimination authorized by executive agreement with the Philippines). This meant thatthey would be disch.arged f i ' o l 1 1 ~ their employment withthe US Navy--so that "local" citizcns could obtain thosejobs at the US military bases.Th e Kossis, and others wh o

Iu d lost their jobs, sought reinstatement in their employment. They sued the US govern ment (naming Secretary

of Defense Weinberger) for violating the 1971 antidiscrirnination statute.

Th e Supreme Court had to interpret the "treaty"exception in Section 106 of the 1971 anti-d iscrimination statute. It prohibited such discrimination, unless a"treaty" authorized this discrimination ag:linst US citizens, in favor of local nationals. Dut did this exceptionmean that discrimination against US citizens would bepermitted only under a constitutional "treaty"-whichrequires Senate consent to discriminate against US citizens 'lbroa.d? Alternatively, did Congress intend to leavethe President's power to enter into an executive agree

nlent permitting jo b discrimination intact, when itpassed the 1971 Act?

Tb e Supreme Court's task was to construe the federal statute, which provides as follows: "Unless prohibitedby treaty, no person shall be discriminated against . . . inthe employment of civilian personnel . . . in any foreigncountry because such person is a citizen of the UnitedStates or is a dependent of a member of the ArmedForces of the United States."Justice Rehnquist's opinionillustrates the difficulties with distinguishing between"Article II treaties" and "executive agreements." Th eCourt's analysis arose in a very sensitive context, with

significant foreign policy ramifications.

COURT'S OPINION: Ou r task is to determine theme:ming of the word "treaty" as Congress llsed it in thisstatute. Congress did no t separately define the word, as it

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

26/35

3 7 8 F U ND A M ENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LAW

has done in other enactments. We must therefore ascer-tain as best we can whether Congress intended the word"treat y" to refer solely to [the COllStitution's] Art. II, 2,cl. 2, "Treaties" those international agreernents concluded by the President with the advice and consent o fthe Senate-or whether Congress intended "treaty" toalso

include ex cutive agreements suchas

theEtA

[BaseLJbor Agreement, which permitted discrimination].Th e word "treaty" has more th,lll one meaning ..

Under principles of international law, the word ordinarily refers to all international agreement concludedbet'ween sovereigns, regardless of the manner in whichthe ,lgreement is brought into force. Under the UnitedStates Constitution, o f course, the word "tre'lty" has ,)far more restrictive meaning. Article II, cl. 2, of thatinstrument provides that the. President "shall havePo\over, by and \,.,ith the Advice and Consent of theSenate, to l1l'lkeTreaties, provided ~ v o thirds o f the Senators present concur."

Congress has no t been consistent in distinguishingbetween Art. II treaties and other forms of internationalagreements. For example, in the Case Act, 1 U. S. C.112b(a), Congress required the Secretary of State to"transmit to the Congress the text of any internationalagreement, other than a treaty, to which the United Statesis

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

27/35

eJ

ers

-nee-is

n

-o

atn-

datt

nty,o-s,-1n

alani-

dtothers

overseas. In early 1971 [just before Congress passed1061, Brig. Gen. Charles H. Phipps, CommandingGeneral of the European Exchange System, issued amemorandulll encouraging the recruitment and hiringoflocaln3tionals inste,ld of United States citizens at thesystem's stores ron us rnilitary basesJ. Th e hjring oflocal nationals, General Phipps reasoned, would result inlower wage costs and turnover rates. Senator Sch\.veiker,a sponsor of 106, complained of General Pmpps' policy

Notes & Questions

1. Th e Supreme Court effectively "lent its hand" to thepresident's intentional discrimination against US cit

izens wh o hoped to work on US military basesabroad. This meant that military dependents, typically

spouses of enlisted personnel, with a generally lowerwage structure than that of military officers, wouldbe unable to 'work, and in many cases thus unable toaccompany their military spouses during overseasassignments. What was the rationale for promotingUS interests via intentional discrimination in favor of

foreign nationals?2. The materials in this section suggest a two-part

process for deciding whether th e president'S exer ciseof the executive agreement power transgresses anylimits contained in the constitutional Treaty Clauseor limiting congressional legislation. First, the presi-dent (through the appropriate federal agency) mustdetermine whether his or he r proposed executiveagreement instead falls within the parameters o f theTreaty Clause, which would require Senate consent.Second, the president must examine existing con

gressional legislation an d attitudes to determinewhether congressional approval should be obtained.As stated l r l the principal treatise on US constitutionallaw in the US, L. Tribe, Treaties and ExecutiveAgreements, 4-4, in 1 AMERICAN CONSTITU-TIONAL LAW 648-649 (3d ed. Ne w York: Foundation

Press, 2000):

Th e precise scope of the President's power to conclude international agreements without the consentof the Senate is unresolved. At on e extreme, theproposition that the treaty is the exclusive medium

TREATY SYSTEM 3 7 9

[o f discriminating against US nationals on US militaryb,lses in EuropeJ . . . .

Wh.ile the question is no t fiee fron, doubt, we conclude that the "treaty" exception contained in 106extends to executive agreements as well as to Art. IItreaties [characterizing these executive agreements as"treaties" for the purpose of authorizing discrimina-tion against US nationals on foreign US militarybases] . . . .

for affecting foreign policy goals and, consequently,that executive agreements are ultra vires [unconsti

tutional] seems adequately refuted . . . .

At the other extreme the notion that executiveagreements know no constitutional bounds proves

equally bankrupt. Executive agreements, no lessthan treaties, must probably be limited to appropriate subject matter. The more difficult questionis whether there exist species of internationalaccord that may take the form of a treaty, but notthat of an executive agreement.

3. In September 2004, a federal appellate courtresolved a conflict akin to Ross i - in this instancebetween a president's military Status o f ForcesAgreement (SOFA) with the United Kingdom.andthe US Foreign Sovereign Immunities Ac t (FSIA)

(2.6). During a bar fight in Tacoma, Washington,several members of the British military started afight with and severely injured a US civilian. The1976 FSIA is ordinarily the "exclusive" source ofjurisdiction over suits involving foreign States andtheir lllstrumentalities. While foreign States are gen

erally presumed to be immune from suit, this conduct fell within the FSIA's "noncommercial tort"exception. The civilian plaintiff could thus sue theUnited Kingdom.

Th e 1951 SOFA executive agreement between theUnited States and the United Kingdom was created to

avoid just such disruptions lr l military service obliga-tions. Local plaintiffs in either country may proceedwith their suits, bu t against the host country- jus t as ifits ow n soldiers had committed the wrongful act. Th eUnited Kingdom was thus immune o'om suit under

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

28/35

3 8 0 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LA W

the SOFA, bu t liable under the FSIA. Th e U$.s;ourtapplied the familiar rule that US legislation shouldno t be applied in a way that violates internationalobligations, unless Congress expressly says otherwise.Thus, the United Kingdom was dismissed, and thelocal citizen's claim was instead deemed to be againstthe United States, under th e Federal Tort Claims

Act. Moore v. United Kingdom, 384 F.3d 1079 (9thCir. 2004).4. Some US labor unions brought an action challenging

constitutionality of North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). President Clinton entered into thattreaty, on behalf of the United States, with Canada andMexico without Senate consent. Th e issue waswhether NAFTA required an "Article [[ Treaty"requirin g Senate ratification. Th e federal appeals court"decided" that this was a nonjusticiable, political question (1.4).Thus:

Th e appellants [unions] concede, as they must,that the Constitution affords the political branchessubstantial authority over foreign affairs and com

merce. Th e appellants also concede that theSupreme Court has recognized the constitutionalvalidity of the longstanding practice of enactinginternational agreements which do not amount tofull-fledged treaties . . . .

Indeed,just as the [Art. II] Treaty Clause fails tooutline the Senate's role in the abrogation oftreaties, we fll1d that the Treaty Clause also fails tooutline the circumstances, if any, under which itsprocedures must be adhered to when approvinginternational commercial agreements.

Significantly, the appellants themselves fail tooffer, either in their briefs or at argument, a workable definition of what constitutes a "treaty."Indeed, the appellants decline to supply any analytical framework whatsoever by which courts candistinguish international agreements which

require Senate ratification from those that do not.- M a d e ill the US A Foulldation lJ. Us., 242

F.3d 1300,1314-1315 ( l I th Cir., 2001).

CONFLICT RESOLUTION

Th e other major problem in US treaty practice ariseswhen there is a contJict among the US Constitution, afederal statute, and/or an international treaty conurutment.

In parts of Europe, Mexico, and certain other regions,treaties must take precedence over internal law in the

event of a conflict. 62 Th e constitutions of Burkina Faso,Congo, Mauritania, and Senegal expressly provide that atreaty is superior to internal law-al though there isapparently no reported judicial decision that affirms thiselevated status.

Th e US Constitution does no t provide a directanswer to the resolution of such contJicts. Article VI pro

vides only that the "Constitution, and the Laws [federalstatutes] of the United States which shall be made inPursuance thereof and all Treaties nude . . . shall be thesupreme Law of the Land .... " This wording does no testablish any relative hierarchy in the event of a contJict.

An internal law of the United States may occasionallyclash with, and supersede, a prior international agreement. This portion of the treaty chapter addresses theresolution o f such conflicts under US law, as opposed toInternational Law, where a State may no t rely 011 its

internal law to avoid international obligations.

Trea ty versus Consti tut ion Th e US Supreme Court

has consistently held that the Constitution prevails whenit contJicts with statutes or treaties. Both a federal statuteand a treaty (executive agreement) were in conflict with

the Constitution in the 1957 case of Reid IJ. Covert. 63 Th eCourt held that civilian wives wh o had killed their rnilitary husbands on US bases, in England and japan, couldnot be tried by a military court-martial. Th e SupremeCourt examined several distinct sources of US law toarrive at this conclusion. Th e Uniform Code of Military

justice (UCMj) is federal legislation, which then providedfor a court-martial in this situ'ltion. Presidential executiveagreements governing crimes occurring on US bases

abroad, incorporated these provisions of the UCMj,which was thus expressly applicable to these civilianwives. Th e court found that neither the Military justiceCode no r the executive agreements could deny thespouses' constitutional rights to indictment by a civiliangrand jury, and to a jury trial by their peers. These rightsenshrined in the US Constitution could no t be vacatedby either the federal statute (UCMj), or by an executiveagreement, which purported to apply the UCi\l1j to military dependents abroad.

Trea ty versus Sta tu te Treaties and federal statutesare on equal footing under Article VI o f the Constitution. Each is therein referred to as the "supreme law of

the lanexpress

Th e

"The ladecisionthat an }

and that

inconsistlict renepositionand Effewas thus

ginia statand deteJVienna

Congresslaw. In iCongressagreemen

(prior towhen the

Th e Ua case inv

tary husbaConstitutiand a pricjurisdictiolthe "Cour

Act of COtion, is onstatute whtreaty, thetreaty null.

(1) Th e(2) A Sft reatycivilians(3) Th etrumps

PROBI

Problem 8

the ICJ 19Relations (of this boothe materia

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

29/35

s,e

o,ais

is

cto

al

inh e

ot

ct.llye

th e

to

its

ur t

hen

tutewith

The

niliould

me

w to

itaryided

utivebasesMj,

vilianstice

th e

vilian

rightscated

cutive

mil

atutesstitu

Jaw of

th e land." Neither is superior to the other, under th eexpress terms of th e Constitution.

Th e US Supreme Court applies the following rule:"The last in time prevails." As stated in the above Reid

decision, the Court has "repeatedly taken the positionthat an Act of Congress . . . is on full parity with a treaty,and that when a statute which is subsequent in time isinconsistent with a treaty, the statute to the extent of conflict renders th e treaty null."64 Th e Court affirmed this

position in 1998, when construing the 1996 Antiterrorismand Effective Death Penalty Act. A Paraguayan defendantwas thus foreclosed from appealing the failure of the Virginia state court system to notifY Paraguay of his arrest3nd detention. Such notification is required by the 1963Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (7.2)65

Congress may thus denounce it prior treaties under USlaw. In its comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986,Congress expressly repudiated a presidential executiveagreement providing for air service with South Africa

(prior to the improvement in international relations,when the white minority relinquished power in 1993).66

Th e US Supreme Court illustrated this progression ina case involving civilian wives wh o murdered their military husband's abroad. Th e case involved all three: the US

Constitution's Bill of Rights, a federal statute (UCMj),and a prior treaty regarding which country would havejurisdiction to try civilian spouses. When conflicts arise,the "Cour t has . . . repeatedly taken the position that anAct of Congress, which must comply with the Constitution, is on a full parity with a treaty, and that 'vvhen a

statute which is subsequent in time is inconsistent with atreaty, the statute to the extent of conflict renders th etreaty nuU."67 So in the event of a conflict:

(1) The Constitution prevails over International Law.(2) A statute (UCMj) and a bilateral Status of Forcestreaty-regarding which country would try these

civilians-were on the same legal footing.(3) The later in t ime-ei ther treaty or federal statute-trumps the prior of the two.

PROBLEMS

Problem 8.A (a f t e r 8.1 Medel l in case) Reconsider

th e ICJ 1980 Hostage Case, and th e 1961 DiplomaticRelations Convention provisions, both set forth in 7.4of this book. Answer the following questions based onth e materials in 8.1:

TREATY SYSTEM 38 1

1. Di d th e Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relationshave to be "self-executing" for th e United States toclaim that Iran breached it?

2. Are those provisions (text, p. 342) self-executing? Ca nthis be answered by reading th e given articles?

3. Based on the iVledelli1'l case analysis, ho w would youresolve the question of whether the Diplomatic Rela

tions treatyis

self-executing?

Problem 8. B (a f t e r 8.2 Reservations case) The

treaties you will study in Chapter 11 illustt"ate th e U Npromotional role in humdl1 rights. One of them is th eU N Convention on th e Elimination of All Forms ofDiscrimination Against Women (CEDAW), available at:. Read an d compare the following information

regarding th e reservations submitted to this conventionby Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, 3nd the United States:

Bangladesh:"On reading the Bangladeshi reservation tothe Women's Convention, indicating that it will implement this convention in accordance with Islamic ShariaLaw, the advocates of women's rights cannot bu t be

extremely skeptical about the possible contribution ofthe Convention (as amended by the [Sharia Law]reservation) to the improvement of the situation of

women in Bangladesh." (Insight about that law is available in 1.3 of this textbook.) L. Lijnzaad, RESER.VA-TIONS TO UN-HUMAN RIGHTS TlliATIES: RATIFY ANDRUIN? 3 (Dordrecht, Neth.: Martinus Nijhoff, 1995).

Saudi Arabia: "I n case of contradiction between anyterm of the Convention and the norms of islamiclaw, th e Kingdom is not under obligation to observethe contradictory terms of th e Convention."

United States: The United States has signed (1980)but not ratifted CEDAW The United States is therefore committed in principle, bu t has yet to mergeword an d deed via Senate confIrmation. Per materi

als in 8.2 of the textbook, a signatory cannot takeany action that is inconsistent with th e object an dpurpose of a signed treaty.

Determine th e following:

(1) Do the Bangladesh an d Saudi Sharia Law reserv3tionscomply with the ICJ Reservations Case"compatibihty"test?

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

30/35

38 2 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON INTERNATIONAL LAW

(2) Does the United States have a higher duty tQ ..avoiddiscrimination against women- than either of theabove two ratifYing nations-based on the UnitedStates signing the CEDAW? Does the post-Reparations Case note, on the Draft Guidelines on Reservations to Treaties, help to resolve these questions?

Problem 8. C (af ter 8.2 Reservations case) Article17(2) of the 1969 VCLT states that when "it appears fromthe . . . object and purpose of the treaty that the applica-tion of the treaty in its entirety between all the parties is anessential condition of the consent of each one to be boundby the treaty, a reservation requires acceptance by all theparties" (italics added).vCLT Article 19(1)(a) provides thatthe legal efrect of a reservation is that it "[m]odifies for thereserving state the provisions of the treaty to which thereservation relates to the extent of the reservation."

Assume the following facts: La Luce del Pueb lomeaning "Light of the People," or LLP- i s an ultra-

radical group of citizens within a hypothetical Cari bbeanState called Haven. Last September, Haven's militaryleader placed the LLP in charge of guarding some kid-naped US citizens. They were being held inconwlUni-cado during political hostilities with the United States.Without authority from the country's leader, some members of LLP decided to mistreat the US citizens. Severalwere beaten. On e was brutally murdered. His body wasthen dumped on the steps of the US embassy in Haven,where journalists had gathered to learn about the latestdevelopments in the escalating hostilities.

A number of foreign newspapers printed a picture ofthe body of the dead US citizen on the US embassy steps.Their news story about the beatings and executionassigned responsibility to "LLp, the zealous group ofHaven idealists wh o say that they resent the decades ofthe US dominance in hemispheric atIairs."This newspa-per account included LLP's statement to these journalists:"We plan, for the benefit of the People's RevolutionaryParty (led by Haven's military leader), to elim.inate all UScitizens in Haven who hinder ou r progress." Subse-quently, US citizens were randomly attacked and beatenin Haven's restaurants and bars. Nationals from othercountries were not harmed in these incidents. Haven'sleader denied any involvement with what he character-ized as "an idealistic, bu t irresponsible splinter group ofradicals to be dealt with if found." Worldwide mediaattention now focused on Haven and its growing confrontation with the United States.

Some US senators thus stated for the Congressional reprlnteRecord that "Haven had added genocide to the long list criticiSlTof international obligations breached by Haven in the to raiselast decade. Haven has failed to adhere to the bilateral processtreaties between the two nations, to the wishes of the MalawelOrganization of American States, and to the unmistak A veable minimum standards of international behavior." tration 0

Under the Genocide Convention, genocide is the killing Crisis."1of members of a particular ethnic group with the intent lies, orto destroy it (as analyzed in 9.5 Radio Machete case). United

Under the applicable US-Haven treaty, murder is an where eextraditable offense. Last October, the US Department of not wor]State demanded that Haven extradite those responsible for militarykilling the US citizen so that they could be tried either in failed rethe United States or in some international tribunal for the executivecrime of genocide. Haven refused this extradition request guarantetbecause "those wh o have killed the US citizen may have several hconunitted murder, but they could no t possibly be thereby of the presponsible for the bizarre claim of genocide." [ran that

Assume that Haven, attempting to show its solidarity Th e lwith the world community, chooses this point in time to (the Algibecome a party to the Genocide Convention. Haven ten 2003.Thders its consent to the appropriate international authority. the July:It also submits the following reservation: "Haven hereby Iran wasadopts the Genocide Convention as binding. Haven families'reserves the sovereign right, however, to use any means at terroristits disposal to eliminate external threats to Haven's terri ereign Intorial integrity." branch n

Ca n Haven legitimately tender this reservation to the this actieGenocide Co nvention, under the IC]'s Resen!ations Case? AlgIers AThe Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties? "terrorist

ASSUJ1Problem 8. 0 (8.2. after "Invalidity" Materials) [n ety of P1980, the VCLT became effective when the minimum above ex,number of national ratifications were deposited with the an d Iran.United Nations. During the negotiating process, US is no t wlhostages initially remained captive in the American necessaryembassy and, for most of the time, at other locations in The Sen.[ran. Th e United States and [ran had no direct diplo can avoidmatic relations. Algeria assisted US President Jimmy basis thatCarter in negotiating a treaty with Iran to secure the release treliberation of these hostages. They were released in Senatolexchange for the simultaneous expungement of Iranian

do not wiassets in the United States, which had been frozen by arrangemcCarter near the outset of the crisis. Th e United States hostilities'also agreed to return assets subject to its control that on its obbelonged to the family of the former Shah of Iran.Var- physical, nious documents about that treaty and related matters are povverful I

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

31/35

0 nallistth e

eralth e

takor."

Uingtent

).

is an

t of

e forer inr the

questhave

ereby

hrityme to

ten

ority.erebyaven

ans atterri

o th el 1 sCase?

In

mum

h the

, USrican

ons indiplo

immy

re th eed inranian

zen byStates

ol thatn. Varters are

reprinted in 20 INT'L LEGAL MAT'Ls 223-240 (1981). Acriticism of the US Department of State's decision no t

to raise the question of force in this particular treatyprocess is presented in Iranian Hostage A g r e e l 1 l e l 1 t J ~ inMalawer book, at 27 (cited in note 14 below).

A very sensitive provision of this treaty required arbitration of any subsequent disputes related to the "Hostage

Crisis."This provision precluded the hostages, their families, or any governmental entity from suing [ran in theUnited States, the International Court of Justice, or anywhere else. President Carter's economic sanctions werenot working, and he did no t want to undertake furthermilitary action to retrieve the hostages from Iran, after afailed rescue attempt in 1979. Instead, he entered into anexecutive agreernenl to resolve this crisis and obtain the

guaranteed safety of the hostages. Subsequent suits byseveral hostages were dismissed by US courts, on the basisof the president's agreement no t to pennit suits against[ran that were spawned by the Hostage Crisis.

The US Senate attempted to abrogate this agreement(the Algiers Accords) on several occasions, as recently as2003. This is a recurring legislative response to cases likethe July 2003 District of Columbia federal case, where[ran was potentially subject to a judgment in a hostagefamilies' class action lawsuit. [ran had been designated aterrorist State, under an amendment to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (textbook 2.6). The executivebranch nevertheless intervened to obtain a dismissal of

this action. Its lawyers successfully argued that theAlgiers Accords were no t affected by [ran's subsequent"terrorist" status under US law 6 8

Assume that the US Senate is debating the propriety of President Carter's negotiations leading to th eabove executive agreement between the United Statesand Iran. The topic of this hypothetical Senate debateis no t whether the Senate's advice and consent werenecessary for th e hostage-release agreement with Iran.Th e Senate has instead chosen to debate whether itCJn avoid the US obligations under th e treaty, on thebasis that the president had to enter into the hostagerelease treaty under duress.

Senator Dove represents a number of colleagues whodo no t wish to alter or negate the effect of the president'sarrangement with Iran.They do not want to risk renewedhostilities or create the impression tha t America goes backon its obligations. Dove contends that "there was nophysicJI, military, or economic coercion that forced thispowel-{u! nation into President Carter's treaty. It was the

TREATY SYSTEM 3 8 3

United States that employed forceful tactics, rather thanIran, when Carter's military rescue mission failed."

Senator Hawk represents an opposing group of senators. She and he r colleagues bope to refreeze Iranianmoney accounts and gold bullion still within the UnitedStates or controlled by private US businesses in foreigncountries. She wants to renew the 1980 Hostage Case liti

gation in a separate phase in tl1e [C]. (See 7.4 for IC] caseexcerpts on the Court's order that Iran free the UShostages.) Relying on Article 52 of the VCLT, Hawkbelieves that the ICJ should render an authoritative decision characterizing the hostage treaty as being invalid onthe basis of VCLT duress.

Senator Hawk thus contends that "the Iranian treatywould never have seen the light of day if we were no tforced into it by the hostage situation." Senator Dove'slitmus test for validating the treaty is an imaginarybright line that separates military and nonmilitary coercion in all circumstances. "The proper approach, in my

no t so humble opinion, is to invJlidate the sham, andshameful, Iranian deal by distinguishing between lawfulan d unlawful coerc ion-ra ther than Senator Dove's

approach, which isolates military duress to invalidate thetreaty from nonmilitary duress, whereby the treaty wouldbe unaffected."

Make the following assumptions:

(a) [ran is a party to the VCLT.(b) [t did no t make any reservations.(c) The hostages have been released, bu t the [ranian

assets are still frozenlavailable for seizure.

(d) Th e Carter hostage release agreement was madeafier the January 27, 1980 "start" date for theprospective applicability of the VCLT.

Two students will present the arguments that Senators Dove and Hawk might use in their Senate debateon the applicability of the VCLT. Can th e United Statesvoid its treaty obligations to IrJn under PresidentCarter's executive agreement?

Problem 8 E ( a f t e r 8.2 Fisher ies Jurisdiction

cases) Th e United States and the hypothetical LarinAmerican

Stateof

Estado entered into a 1953 Treaty ofFriendship, Commerce, and Navigation (FCN).This treatyinitiated their international relationship and covered anumber of detaiJs. In the relevant treaty clause, the UnitedStates agreed that Estado could nationJlize American business interests. In return, Estado was required to provide

-

8/8/2019 Tratadooos Karen

32/35

3 8 4 FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES ON I N T E R N A T I O r ~ A L LAW

reasonable compensation, which was defined in the treatyas "the fair market value of all nationalized assets."

Th e US-Estado relationship has turned sourThe Estadogovernment nationalizes a major US corporation's property in Estado, bu t does no t tender an)' compensation.Estado resisted the US claim of entitlement to compensation under the 1953 friendship treaty. Estado's Minister of

State issued the following statement:

A fundamental change in circumstances has precluded the continued viability of the 1953 FC NTreaty.The 1974 United Nations Declaration on th e

Establishment of a Ne w International EconomicOrder obviously necessitates termination of th edecades earlier compensation requirements of the outmoded US-Estado FCN Treaty [see 4.4 of this texton th e NIEO].The changed circumstance is that ou r

nation, which th e Creator has endowed with naturalresources, need no longer fall prey to another